Abstract

Purpose

Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) mutations are associated with improved survival in gliomas. Depending on the IDH1 status, TERT promoter mutations affect prognosis. IDH1 mutations are associated with alpha-thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome X-linked (ATRX) mutations and alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT), suggesting an interaction between IDH1 and telomeres. However, little is known how IDH1 mutations affect telomere maintenance.

Methods

We analyzed cell-specific telomere length (CS-TL) on a single cell level in 46 astrocytoma samples (WHO II-IV) by modified immune-quantitative fluorescence in situ hybridization, using endothelial cells as internal reference. In the same samples, we determined IDH1/TERT promoter mutation status and ATRX expression. The interaction of IDH1R132H mutation and CS-TL was studied in vitro using an IDH1R132H doxycycline-inducible glioma cell line system.

Results

Virtually all ALTpositive astrocytomas had normal TERT promoter and lacked ATRX expression. Further, all ALTpositive samples had IDH1R132H mutations, resulting in a significantly longer CS-TL of IDH1R132H gliomas, when compared to their wildtype counterparts. Conversely, TERT promotor mutations were associated with IDHwildtype, ATRX expression, lack of ALT and short CS-TL. ALT, TERT promoter mutations, and CS-TL remained without prognostic significance, when correcting for IDH1 status. In vitro, overexpression of IDHR132H in the glioma cell line LN319 resulted in downregulation of ATRX and rapid TERT-independent telomere lengthening consistent with ALT.

Conclusion

ALT is the major telomere maintenance mechanism in IDHR132H mutated astrocytomas, while TERT promoter mutations were associated with IDHwildtype glioma. IDH1R132H downregulates ATRX expression in vitro resulting in ALT, which may contribute to the strong association of IDH1R132H mutations, ATRX loss, and ALT.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11060-020-03394-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Isocitrate dehydrogenase, D2HG, Telomerase, Telomere length, Q-FISH, TERT promoter, ALT, ATRX

Introduction

Gliomas are the most common primary brain tumors in adults and represent a histologically defined entity with a high molecular heterogeneity determining prognosis and response to therapy [1, 2]. Along this line, determination of isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) 1 mutation status became mandatory in the updated 2016 WHO classification [3]. IDH1 mutations are driver mutations of low-grade gliomas and found in 80% [4] but are not detectable in primary glioblastoma (GBM) [2, 5]. The most common IDH1 mutations in glioma (> 95%) result in an amino acid substitution at arginine 132 (R132), which resides in the enzyme’s active site [4]. Despite the abundance of evidence in support of a major pathophysiological and prognostic role of IDH1 mutations [6–8], the precise mechanism of how IDH1 mutations modulate malignancy is still not completely understood. While IDH1 has a major role in the citric acid cycle, R132H mutation (IDHR132H) results in a gain of function; IDH1R132H catalyzes conversion of alpha-ketoglutarate into the oncometabolite D-2-hydroxyglutarate (D2HG) [9]. D2HG inhibits dioxygenases that depend on alpha-ketoglutarate, like Ten-eleven translocation methylcytosine dioxygenase 1 (TET1) and histone-lysine demethylases [10]; this results in increased CpG island methylation [11] and a stable reshaping of the epigenome (CpG island methylation phenotype, CIMP) changing transcriptional programs and altering the differentiation state [12].

Telomeres determine the proliferative capacity of mammalian cells. Telomere length (TL) shortens with each cell division until cell proliferation is arrested once the maximal number of cell divisions is reached (“Hayflick limit”). In case of further replication, cells undergo chromosomal instability and induction of apoptosis. Expression of human telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) allows for the stabilization and elongation of telomeres. Telomere maintenance mechanisms (TMM) are necessary for immortality of cancer cells by overcoming genetic instability associated with critical telomere shortening [13].

TERT promoter mutations (TERTpmut) are common in glioma and found in 80% of all primary GBM [14–16], representing one possible TMM. TERTpmut disrupt the tight transcriptional suppression of TERT in somatic cells resulting in increased TERT expression and telomerase activity in vitro in glioma [17].

A mechanism of homologous recombination [18] to maintain TL, known as “alternative lengthening of telomeres” (ALT), was also identified in gliomas. About 20–63% of adult low-grade glioma and 11% of adult GBM use ALT as an additional mechanism for telomere maintenance [19, 20]. Dysfunction of the α-thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome X-linked (ATRX)/death-associated protein 6 (DAXX) complex is known to result in ALT along with more widespread genomic destabilization [21–23]. ATRX and DAXX are central components of a chromatin-remodeling complex required for the incorporation of H3.3 histone proteins into the telomeric regions of chromosomes [24, 25]. 75% of grade II–III astrocytomas and secondary GBM harbor ATRX abberations [26–28] linking IDH1 mutations with ATRX and ALT.

Despite the strong associations observed, few data is available how the different pathways interact on telomere maintenance. The aim of this study was to investigate the interplay among IDH1, TL, ATRX and TERT/ALT using a newly developed distinctive methodology that allowed determination of glioma cell-specific telomere length (CS-TL) on a single cell level.

Materials and methods

Patients

Tissue samples from 46 astrocytoma patients were included for the study. The Regional Committee on Health Research Ethics approved the study for Southern Denmark (S2DO90080) and Danish Data Protection Agency (file number: 2009-41-3070) and all patients provide informed consent. The use of tissue was not prohibited by any patient according to the Danish Tissue Application Register. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. All patients underwent primary surgery between 1991 and 2005 at the Department of Neurosurgery, Odense University Hospital, Denmark. All cases were independently reviewed and reclassified by M.D.S and B.W.K. (senior neuropathologist) according to the 2016 WHO guidelines [2] as described in [29]. Clinical data were extracted from the respective electronic patient journal. Clinical and neuropathological characteristics of the astrocytoma patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and pathology

| Diffuse astrocytoma | Anaplastic astrocytoma | Glioblastoma | All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 24 | 9 | 13 | 46 |

| Age | ||||

| Mean | 45.2 | 47.6 | 65.3 | 51.4 |

| Range | 2.6–78.5 | 29.5–71.0 | 49.4–77.5 | 2.6–78.5 |

| Sex (n) | ||||

| Male | 14 (58.3%) | 3 (33.3%) | 10 (76.9%) | 27 (58.7%) |

| Female | 10 (42.7%) | 6 (66.7%) | 3 (23.1%) | 19 (41.3%) |

| Status (n) | ||||

| Alive | 3 (12.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (6.5%) |

| Dead | 21 (87.5%) | 9 (100%) | 13 (100%) | 43 (93.5%) |

| Overall survival (months) | ||||

| Median | 76.9 | 24.0 | 7.5 | 32.6 |

| Range | 3.4–280.0 | 4.7–48.8 | 1.5–34.2 | 1.5–280.0 |

| IDH1 status (n) | ||||

| Mutated | 18 (75.0%) | 4 (44.4%) | 1 (7.7%) | 23 (50.0%) |

| Wildtype | 6 (25.0%) | 5 (55.6%) | 12 (92.3%) | 23 (50.0%) |

| ATRX status (n) | ||||

| Loss | 20 (83.3%) | 4 (44.4%) | 4 (30.8%) | 28 (60.9%) |

| Retained | 4 (16.7%) | 5 (55.6%) | 9 (69.2%) | 18 (39.1) |

| 1P/19Q status (n) | ||||

| CO-DEL | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1P-DEL | 0 | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (7.7%) | 2 (4.3%) |

| 19-DEL | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NON-DEL | 5 (20.8%) | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (15.3%) | 9 (19.6%) |

| Not determined | 19 (79.2%) | 6 (66.7%) | 10 (76.9%) | 35 (76.0%) |

| hTERT promoter mutation | ||||

| Mutated | 6 (25.0%) | 3 (33.3%) | 9 (69.2%) | 18 (39.1%) |

| C228T | 5 (83.3%) | 2 (66.7%) | 8 (88.9%) | 15 (83.3%) |

| C250T | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (11.1%) | 3 (16.7%) |

| None | 17 (75.0%) | 5 (55.6%) | 4 (30.8%) | 26 (56.5%) |

| Not determined | 1 (4.1%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | 2 (4.3%) |

| ALT status | ||||

| Negative | 12 (50%) | 5 (55.6%) | 12 (92.3%) | 29 (63.0%) |

| Positive | 12 (50%) | 4 (44.4%) | 1 (7.7%) | 17 (37.0%) |

| KI67 proliferation rate | ||||

| Mean (%) | 3.3 | 9.7 | 10.2 | 6.7 |

| Range (%) | 0–30 | 3–20 | 2–35 | 0–35 |

| CS-TL | ||||

| Median | 11.8 | 13.6 | 3.5 | 11.0 |

| Range | − 1.1 to 36.7 | − 3.9 to 31.5 | − 6.0 to 25.2 | − 6.0 to 36.7 |

Immunohistochemistry

Formaldehyde-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) sections of three µm from pre-surgery tissue biopsies were used for this study. FFPE sections were stained as described previously using primary antibodies against IDH1R132H (H09, 1:100, Dianova, Germany) [30] and ATRX [29] (HPA001906, 1:100, Atlas Antibodies, Sweden) epitopes.

DNA extraction, polymerase chain reaction and mutational analysis by sequencing

Mutations in the TERT promoter region were identified by PCR and Sanger sequencing as described previously [31]. The detailed protocol can be found in the Supplementary Materials and methods.

Cell culture, proliferation and clonogenicity

For the cell culture experiments the doxycycline-inducible GBM cell line LN319 expressing IDH1 wildtype (IDH1WT) and IDH1R132H was used. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Gibco, Germany) supplemented with 10% tetracycline-free fetal calf serum (FCS) (Clontech, USA) and standard antibiotics (Gibco, Germany). 1 µM doxycycline was used (Sigma Aldrich, Germany) to induce expression. Cell proliferation was assessed using the CellTiter-Blue Assay (Promega, Germany) as described previously [32] using the FLUOstarOPTIMA (BMG Labtech, Germany) fluorometer.

For colony-forming unit assays, 2500 cells/well were seeded in a 6-well format for 10 days before colonies were fixed and stained with Cristal Violet (Sigma, Germany). For agar assays, 8000 cells/well were seeded in a 6-well format and incubated for 3 weeks before cells were stained with Cristal Violet. Images were acquired with a Cool Snap™ HQ2 digital camera (Photometrics, USA) on an Axiophot 2 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany). Quantification was done using ImageJ software (open source). Results are means of three repeated experiments.

(D)-2-hydroxyglutarate (DGH2) assay

The DGH2 assay used was based on an enzymatic assay as previously described [9]. The detailed protocol can be found in the Supplementary Materials and methods.

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis and mRNA expression

Determination of TERT and ATRX mRNA expression was carried out as described presviously[32]. Gene expression is expressed in fold change according to the method. Additional information can be found in the Supplementary Materials and methods.

Quantitative fluorescence in situ hybridization (Q-FISH)

TL analysis was done by a modified protocol of immuno-quantitative fluorescence in situ hybridization (Q-FISH) as previously described [31–35]. FFPE sections of the cohort were deparaffinized and rehydrated before antigen retrieval in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Slides were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 and blocked for 30 min in serum-free buffer (Rotiblock 1:10, Roth, Germany). Actin fibers were first stained with primary antibody mouse anti-human alfa-SMA (1:200, DAKO, Germany) and a goat anti-mouse Alexa Fuor 633 (1:100, Thermo Fisher, Germany) as secondary antibody. Next, cells were post-fixed in formalin for 30 s and dehydrated with increasing ethanol series before telomere staining. For cells in culture, cells were recovered from culture, fixed in methanol:acetic acid (3:1), cytospin, air dried and dehydrated with ethanol before telomeres were stained. Telomere staining consisted in providing a hybridization mixture containing the Cy3-(C3TA2) peptide nucleic acid (PNA) probe (Panagene, South Korea) to the slides for 3 min at 85 °C for DNA denaturation. Slides were then hybridized for 2 h at room temperature in a humidified chamber. Next, slides were washed with a formamide-based buffer, DAPI stained, and mounted with Vectashield antifade mounting medium (Vector Labs, USA). Fluorescence was acquired with the high-resolution laser-scanning microscope LSM710 (Zeiss, Germany). H&E stained sections were analyzed in parallel for all cases to identify tumor areas. Fluorescent image capture was done with ×63 optical magnification and ×1.2 zoom. A multi-tracking mode of 0.5 μm-steps was used to acquire images of DAPI, Cy3 and Alexa Fluor 633 stainings. Maximum projection of five single consecutive steps of 1.2 µm each was done for TL quantification using Definiens software (Definiens, Germany). Nuclei and telomeres were detected based on the respective DAPI and Cy3 intensity. Alfa-SMA was used to identify endothelial cells that were used as an internal control to correct for TL inter-individual variability [32–38]. A mean number of 150 tumor cells and 100 endothelial cells were assessed per case. To determine the tumor cell-specific telomere length (CS-TL), the difference (Δ telomere length) between the TL of astrocytoma cells and the TL of endothelial cells was calculated and designated in arbitrary units (a.u.) of fluorescence.

ALT assessment

All astrocytoma cases were assessed for the presence of ALT phenotype using telomere Q-FISH staining. ALT positivity was identified by large, ultrabright, clumpy, intranuclear foci of telomere FISH signals, as previously described [20, 21]. A tumor was defined as ALT-positive, when the following two criteria were fullfilled: (1) the presence of ultra-bright intranuclear foci of telomere FISH signals (ALT-associated telomeric foci), with integrated total signal intensities for individual foci being > 10-fold the mean signal intensities per cell of all telomeric signals from endothelial cells within the same case and (2) the number of cells with ALT-associated telomeric foci being 1% or more of the total number of tumor cells assessed per case [20, 21].

ATRX and TERT Immunofluorescence and western blotting

Immunofluorescence for ATRX and TERT followed previously published protocols [32, 35, 37]. Western blot was carried out according to previous published standard protocols. The detailed protocol can be found in the Supplementary Materials and methods.

Statistical analysis

The data was collected via Microsoft Excel 2007 and analyzed using Stata version 15 (StataCorp LP, USA) or GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc, USA). ANOVA with Bonferroni correction was used for comparison of more than two groups. Student’s unpaired t test was used to compare differences between two groups. Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze categorical data. Overall survival was defined from the day of initial surgery until death or date of censoring (July 1st, 2018). Survival data were analysed and we using Kaplan–Meier and the multivariate Cox regression model to adjust for age, WHO grade, and IDH1 status. Survival curves were compared using the log-rank test.

Results

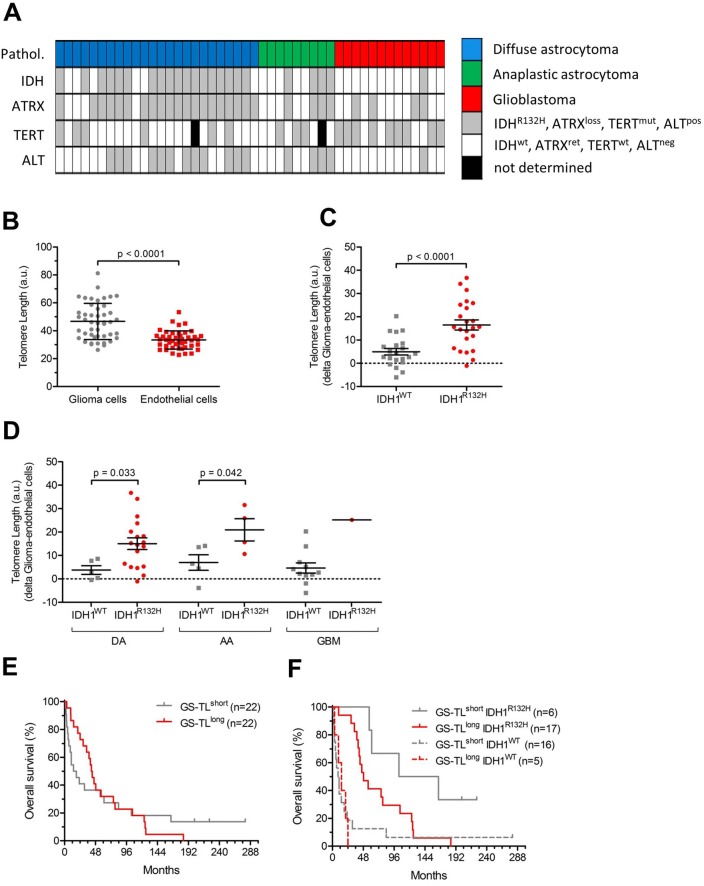

Association of IDH1R132H mutations and telomere length

The incidence of IDH1R132H mutations in our cohort was 50% (Fig. 1a, Table 1). Single cell-based telomere analysis using modified immuno-Q-FISH (Supplementary Figure S1A, B) revealed significantly longer TL in astrocytoma as compared to endothelial cells (p < 0.0001) and a substantial inter-individual variability (Fig. 1b). To overcome this issue, we used the endothelial cells as internal control, which allowed correction of the TL of astrocytoma cells for age and for inter-individual variability (i.e. CS-TL). The CS-TL was significantly longer in IDH1R132H-mutated tumors as compared to IDH1WT tumors (Fig. 1c) irrespective of tumor grade (Fig. 1d), while there were no significant differences among the different tumor types (p = 0.19, Supplementary Figure S1C). IDH1R132H mutation was significantly associated with improved patient survival (HR 0.28; 95% CI 0.14–0.50; p < 0.001, Supplementary Figure S1C) with similar tendency (HR 0.47; 95% CI 0.21–1.08; p = 0.076) when adjusting for age and WHO grade. CS-TL did not significantly correlate with prognosis (HR 0.98; p = 0.95) (Fig. 1e). However, when dichotomizing patients based on IDH1 status and CS-TL, patients with IDH1R132-mutated tumors and long CS-TL had significantly poorer survival than patients with IDH1R132-mutated tumors and short CS-TL (HR 1.80; 95% CI 1.03–3.16; p = 0.030, Fig. 1F). No significant prognostic value was found for patients with IDHWT tumors (HR 0.98; 95% CI 0.59–1.65; p = 0.95, Fig. 1f).

Fig. 1.

Glioma cell-specific telomere length in IDH1WT and IDH1R132H glioma. a Overview of biomarkers status in glioma patients (n = 46). b Telomere length in glioma vs endothelial cells. c Telomere length (in arbitrary units, a.u.) in IDH1WT and IDH1R132H glioma samples; d Telomere length (in a.u.) in IDH1WT and IDH1R132H glioma stratified by WHO tumor grade (DA diffuse astrocytoma, AA anaplastic astrocytoma, GBM gliobastoma multiform); e Kaplan–Meier survival curves (in months) of patients with CS-TL below (CS-TLshort) or above median; f Kaplan–Meier survival curves (in months) of patients with CS-TL below (CS-TLshort) or above median stratified based on IDH1 mutational status

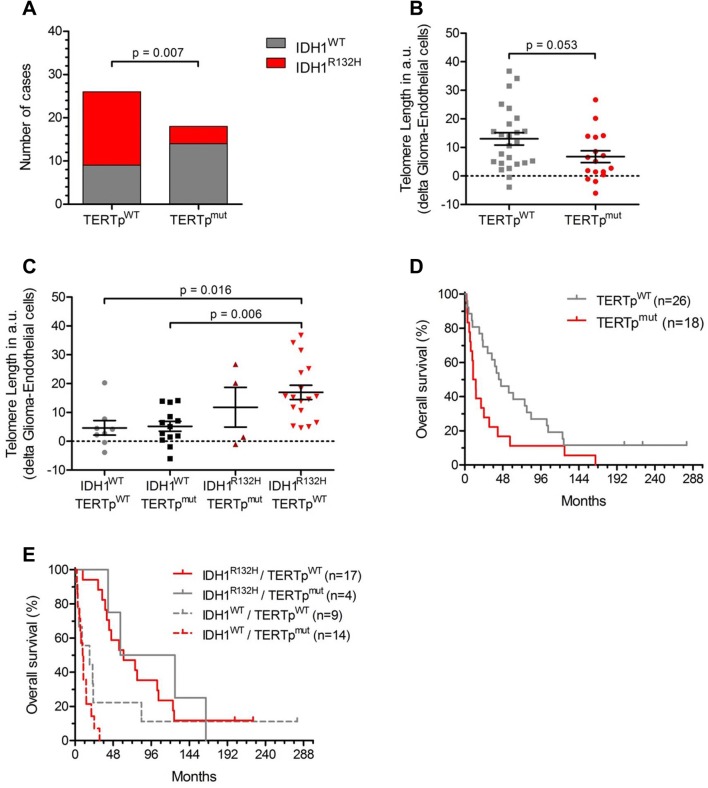

hTERT promoter mutations, IDH1 mutations, and telomere length

The incidence of TERTpmut was 43% of which 84% harbored a C228T point mutation and 16% had a C250T point mutation (Supplementary Figure S2A) (Table 1). The presence of TERTpmut was associated with IDH1WT (p = 0.007) (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

TERT promotor, glioma cell-specific telomere length and IDH status. a Distribution of IDH1WT and IDH1R132H among the TERTpmut and TERTpWT patients (p = 0.001, X2-test). b Glioma-specific telomere length (CS-TL, in arbitrary units, a.u.) in TERTpWT and TERTpmut tumors. c CS-TL (in a.u.) of glioma patients according to IDH1 and TERTpmut status. d Kaplan–Meier survival curves of TERTpWT and TERTpmut patients. e Kaplan–Meier survival curves of TERTpWT and TERTpmut patients stratified after IDH1 status

TERTpmut tumors had slightly shorter CS-TL than TERTpWT tumors (p = 0.05) (Fig. 2b). When analyzing CS-TL according to IDH1 and TERTpmut status, we confirmed the increased CS-TL of IDH1R132 tumors but did not found significant differences of CS-TL beween IDH1WT/TERTpWT and IDH1WT/TERTpmut or IDH1R132H/TERTpWT and IDH1R132H/TERTpmut tumors (Fig. 2c).

TERTp status was significantly associated with reduced survival (HR 2.05; 95% CI 1.10–3.86; p = 0.022) in the entire cohort (Fig. 2d). However, in patients with an IDH1R132H tumor, TERTp status did not significantly associate with survival (Fig. 2e), and multivariate analysis unveiled that TERTp status was not an independent prognostic factor when adjusting for age, WHO grade, and IDH1 status (HR 1.06; 95% CI 0.50–2.24; p = 0.87).

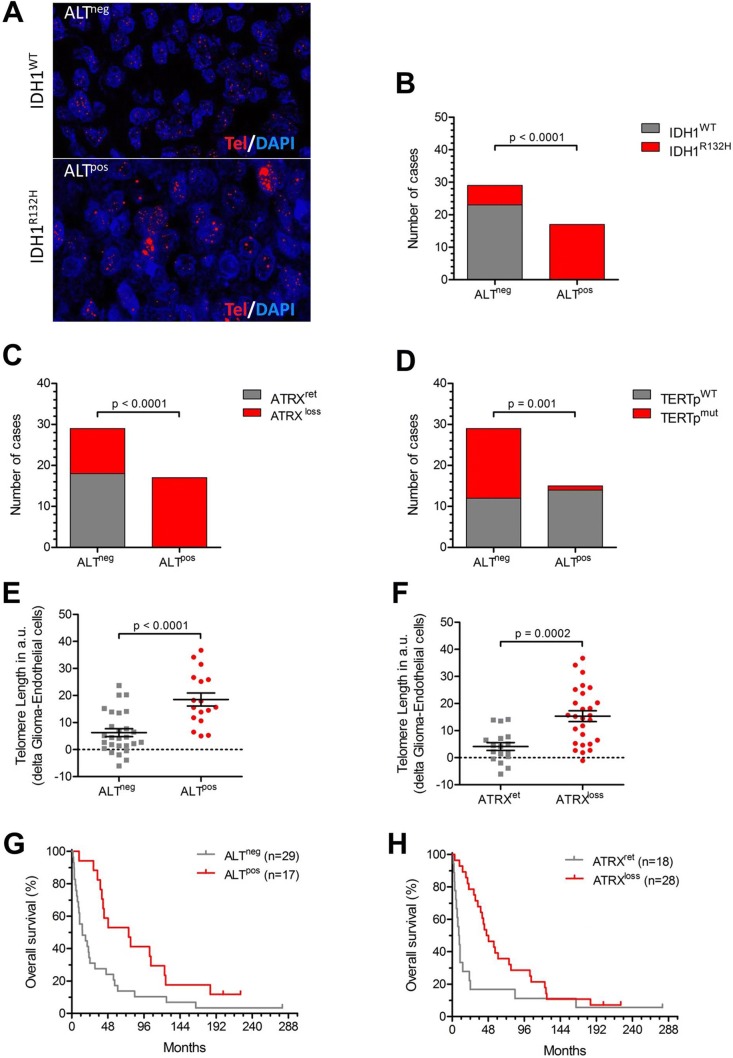

ALT, ATRX mutations and telomere length

Using telomere FISH, we studied the presence of ALT (ALTpos) on a single cell level in our cohort (Fig. 3a). 37% of the patients had ALTpos tumors (Table 1) of which 100% also had an IDH1R132H mutation (Fig. 3b). Further, loss of ATRX expression (Fig. 3c) and TERTpWT (Fig. 3d) were associated with the presence of ALT. Both, presence of ALT and loss of ATRX expression were significantly associated with longer telomeres (p < 0.001, Fig. 3e, f) and improved survival (HR 0.42; 95% CI 0.22–0.81; p = 0.007 and HR 0.46; 95% CI 0.4–0.85; p = 0.012, respectively; Fig. 3g, h). However, this association disappeared when adjusting for age, WHO grade and IDH1 status i a multi-variate analysis (ALT status: HR 0.62; 95% CI 0.23–1.72; p = 0.36; ATRX status: HR 1.12; 95% CI 0.43–2.93; p = 0.82).

Fig. 3.

ATRX, alternative lengthening and survival. a Representative images showing Q-FISH stained gliomas with (ALTpos) and without ALT (ALTneg, magnification: 756x). b Number of IDH1WT and IDH1R132 patients stratified according to ALT status. c Number of ATRXWT and ATRXmut patients stratified according to ALT status. d Number of TERTpWT and TERTpmut patients stratified according to ALT status. e Glioma-specific telomere length (CS-TL in arbitrary units, a.u.) in ALTneg and ALTpos tumors. f Glioma-specific telomere length (CS-TL in arbitrary units, a.u.) in tumors with retained (ATRXret) ATRX and in tumors with ATRX loss (ALTloss). g Kaplan–Meier survival curves (in months) of glioma patients according to ALT status. h Kaplan–Meier survival curves (in months) of glioma patients according to ATRX mutational status

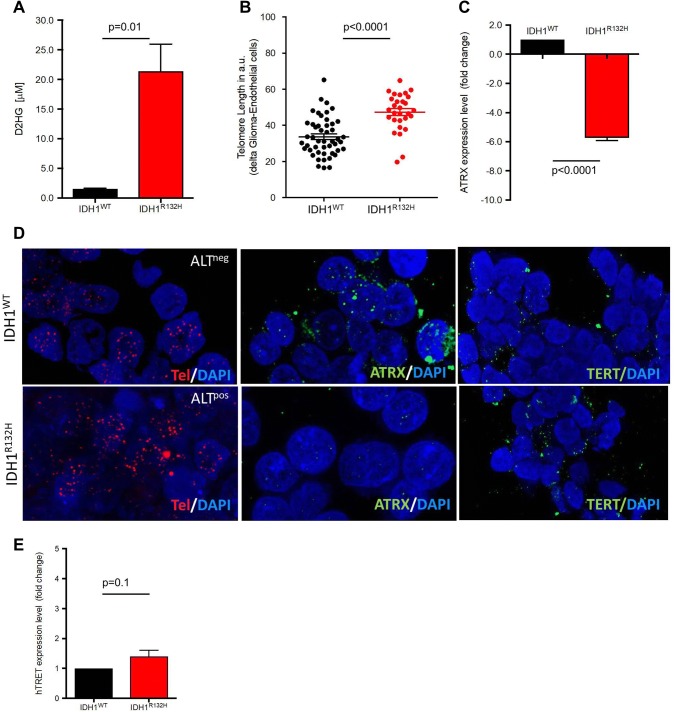

In vitro overexpression of mutant IDHR132H in a GBM cell line

To understand the role of IDH1R132H mutations in regulating CS-TL in glioma, we used a doxycycline-inducible GBM cell line (LN319) expressing IDH1WT and IDH1R132H. The cell line was previously described and the presence of the IDH1R132H mutation was confirmed by sequencing [39]. IDHR132H expression induced by doxycycline significantly stimulated D2HG synthesis (p = 0.01; Fig. 4a), and compromised proliferation and clonogenicity (Supplementary Figure S3A-B). In this in vitro model, induced IDH1R132H overexpression also resulted in a significant increase in TL after nine population doublings (Fig. 4b; Supplementary Figure S3C) and a significant downregulation of ATRX at transcriptional level (Fig. 4c). Telomere FISH detected a significant increase in ALTpos cells in IDH1R132H cells (Fig. 4d, left panels) and loss of ATRX protein expression (Fig. 4d) middle panels). Induced IDHR132H overexpression neither altered the TERTpmut status after short or long-term culture (Supplementary Figure S3D) nor significantly increased TERT mRNA expression level (Fig. 4e). Immunofluorescence for TERT protein expression with DAPI counterstaining (Fig. 4d, right panels) illustrated the TERT-independent increase of TL in IDHR132H cells.

Fig. 4.

Telomerelength after induction of IDH1R132H expression. a Production of the metabolite (inM) in the glioma cell line LN319 after the doxycycline-induced overexpression of IDH1R132H and control conditions. D2HG was measured in the medium supernatant after three population doublings in culture. b Telomere length in the doxycycline induced IDH1WT and IDH1R132H cell lines, after nine population doublings in culture (IDH1WT = 33.76 ± 1.54 a.u, n = 48 vs. IDH1R132H = 47.3 ± 1.93 a.u, n = 29). c Fold change of ATRX mRNA expression after doxycycline treatment and nine population doublings as compared to untreated controls. d Representative images of Q-FISH stained doxycycline induced IDH1WT (upper row) and IDH1R132H cell lines (lower row). All images correspond to cell culture after 14 population doublings. The presence of ALT (left panel: telomere FISH (red), DAPI counterstaining), ATRX protein expression (middle panel: ATRX immunofluorescence (green), DAPI counterstaining), and TERT expression (right panel: TERT immunofluorescence (green), DAPI counterstaining) is given (magnification 756x). e TERT expression levels (fold change) at the mRNA level of doxycycline-induced IDH1WT and IDH1R132H cell lines after nine population doublings in culture

Discussion

Maintenance mechanisms of telomeres are promising therapeutic targets and small molecule telomerase inhibitors are currently tested in clinical trials and filed for approval for the treatment of myeloproliferative syndromes [40, 41]. Exact understanding of telomere biology in glioma is therefore of high translational importance, given the completely diverse prognostic impact of TERTp mutations according to the IDH1 mutation status. Here we provide evidence suggesting that glioma subgroups with and without IDH1 mutations use different TMM and describe a new pathway linking the IDH1R132H mutations to ALT.

One major limitation of published studies on telomere biology in solid cancer was missing availability of techniques that allow the determination of TL on a single cell level. In most studies performed so far [42–44], TL in tumor samples was actually derived from a mixture of vessels, immune cells and normal brain or tumor cells. This impaired significantly the validity and robustness of such studies. Furthermore, these studies rarely controlled for inter-individual (mostly genetic) variability of TL or the presence of ALT. In our study, we developed a modified immuno-Q-FISH technique for the determination of the TL in glioma cells at a single cell level, thus allowing to overcome some of these limitations not only by measuring tumor cells individually but also by using endogenous endothelial cells as non-malignant controls. Using this technique, we could show an increased CS-TL in IDH1R132H mutated as compared to IDH1WT tumors.

Concerning the role of ARTX mutations in gliomas [21, 23, 26–28], we confirmed the association with survival[45] and with ALT[21] as well as the association among ALT, ATRX expression loss, and IDH1R132H. However, the samples size of our cohort does not allow sound conclusions the prognostic relevance of the different TMM and the lacking association of ALT and TERTp mutations in the multivariate analysis have to be interpreted with caution. In line with Heidenreich et al. [42], our data supports the evidence that TERTpmut are associated with shorter TL in gliomas.

Here we showed that the IDH1R132H mutation is directly associated with a lack of ATRX expression and consequently, ALT as described previously [46]. In our sample, all tumors with ALT bear IDH1R132H mutations and lost ATRX expression. Together with the inverse association of ALT with TERTpmut, our data suggests that ALT is the major TMM in IDH1R132H astrocytoma. Conversely, TERTp mutations appear to be the crucial TMM in IDHWT astrocytoma.

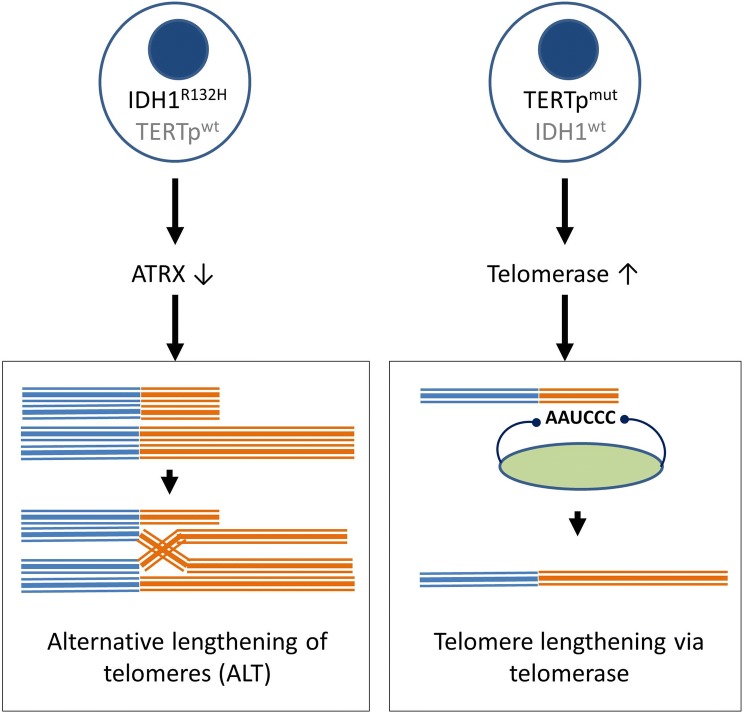

Our data suggests a dichotomy of mechanisms in astrocytoma depending on the presence of IDH1 mutations (Fig. 5). In one tumor with TERTp mutations and ALT, the co-existance of two distinct TMM in IDH1R132H cells of the same tumor (ALT and telomerase-dependent mechanisms) may exist, similar to the mosaic hypothesis previously suggested for other tumor types, e.g. sarcomas [47]. The proposed dichotomy indicates that treatment strategies targeting telomere maintenance, e.g. treatment with telomerase-inhibitors or ALT targeted treatment such e.g. PARP inhibitors or ATRX directed drugs [48, 49], must be personalized to the patient according to TMM. It is likely that the use of telomerase inhibitors can be ineffective or even detrimental in treating patients with IDHR132H gliomas. Thus, the determination of ALT could be usefull as predictive marker to identify patients not responding to telomerase inhibitors.

Fig. 5.

Overview of the two mechanisms of telomere maintenance. a Acquisition of IDH1R132H mutation leads to reduced ATRX expression and ALT. b Acquisition of TERTpmut mutation results in increased telomerase expression and telomere elongation via telomerase

We also showed that overexpression of IDH1R132H in glioma cells in vitro result in a phenotype that fully mimicked all phenomena observed in the patient samples. Overexpression of IDH1R132H in the glioma cells resulted in D2HG production, decreased proliferation in vitro, loss of ATRX expression in vitro and ALT. Reduced ATRX expression due to IDH1R132H overexpression suggests that IDH1R132H alone is sufficient to diminish ATRX expression and thereby induce ALT. However, the importance and functional relevance of this mechanism needs to be further confirmed in vivo. Further, it remains to be clarified, why IDHR132H mutated glioma cells favor ATRX mutations, although there is a second, alternative pathway to suppress ATRX.

An obvious mechanism linking IDH1R132H phenotype to the loss of ATRX in human glioma may be the existence of a typical hypermethylation/CpG island methylation of the ATRX gene. Our data partially supports the results found by Ohba et al. [50], who showed that IDH1 mutations do not select for or induce ATRX mutations or TERTpmut. However, we found no significant reactivation of TERT.

In conclusion, we found that ALT is the major TMM in IDH1R132H astrocytomas and that IDH1R132H mutations can directly suppress ATRX expression resulting in ALT.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 1 (JPEG 291 kb) Supplementary Figure S1. (A) Representative images of the immunofluorescence-based strategy used for CS-TL quantification in single tumor cells; tumor areas were identified by H&E staining, then sections were Q-FISH stained in combination with alfa-SMA immunofluorescence for identification of vessel cells (non-tumor cells that served as internal control). DAPI was used for nuclear counterstain of all cells (magnification 756x). (B) Telomere length in glioma patients according to WHO tumor grade. (C) Kaplan Meier survival curve of astrocytoma patients stratified based on IDH1 mutational status.

Supplementary material 2 (JPEG 166 kb) Supplementary Figure S2. (A) Representative chromatograms showing TERT promoter status (wildtype vs. C228T or C250T mutation) in the glioma tumors after Sanger sequencing.

Supplementary material 3 (JPEG 406 kb) Supplementary Figure S3. (A) Representative images of the colony-forming unit assay of non-induced (-) and doxycycline-induced (+) IDH1WT and IDH1R132H cell lines (scale: 1.7 cm). (B) Representative images of the agar assay of non-induced (-) and doxycycline induced (+) IDH1WT and IDH1R132H cell lines (magnification 50x). (C) Representative images of Q-FISH stained doxycycline induced IDH1WT and IDH1R132H cell lines after one (PD1) and five (PD5) population doublings in culture (magnification 756x); (D) Representative chromatograms showing absence of TERTpmut by Sanger sequencing in doxycycline induced IDH1WT and IDH1R132H cell lines after three (PD3) and 27 (PD27) population doublings in culture.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL. We would like to thank Andreas von Deimling for his excellent comments on the manuscript. Further, we are thankful to Anne Abels for the excellent technical assistance.

Author contributions

MSVF: Performed the experiments analyzed, interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. MDS: Performed the IHC experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data, and revised the manuscript. SP: Provided and helped performing the 2HG and the LN319 IDHR132H assays and revised the manuscript. DB: Provided clinical data and interpreted the data. ASB: performed experiments and analyzed the data. BWK: Provided patient samples, clinical data and interpreted the data. THB provided fincancial support, analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript; FB, CPB conceived and planned the study design, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a Grant START grant (RWTH Aachen University) to M.S.V.F. and Region of Southern Denmark Grant to C.P.B. (17/18517).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Stefan Pusch is patent holder of a patient on the 2HG assay used in this manuscript. All terms concerning this patent are handled by the DKFZ Technology Transfer department. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Christoph Patrick Beier and Fabian Beier have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Huse JT, Phillips HS, Brennan CW. Molecular subclassification of diffuse gliomas: seeing order in the chaos. Glia. 2011;59:1190–1199. doi: 10.1002/glia.21165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Kleihues P, Ellison DW. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:803–820. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eckel-Passow JE, Lachance DH, Molinaro AM, Walsh KM, Decker PA, Sicotte H, Pekmezci M, Rice T, Kosel ML, Smirnov IV, Sarkar G, Caron AA, Kollmeyer TM, Praska CE, Chada AR, Halder C, Hansen HM, McCoy LS, Bracci PM, Marshall R, Zheng S, Reis GF, Pico AR, O’Neill BP, Buckner JC, Giannini C, Huse JT, Perry A, Tihan T, Berger MS, Chang SM, Prados MD, Wiemels J, Wiencke JK, Wrensch MR, Jenkins RB. Glioma groups based on 1p/19q, IDH, and TERT promoter mutations in tumors. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2499–2508. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Brat DJ, Verhaak RG, Aldape KD, Yung WK, Salama SR, Cooper LA, Rheinbay E, Miller CR, Vitucci M, Morozova O, Robertson AG, Noushmehr H, Laird PW, Cherniack AD, Akbani R, Huse JT, Ciriello G, Poisson LM, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Berger MS, Brennan C, Colen RR, Colman H, Flanders AE, Giannini C, Grifford M, Iavarone A, Jain R, Joseph I, Kim J, Kasaian K, Mikkelsen T, Murray BA, O’Neill BP, Pachter L, Parsons DW, Sougnez C, Sulman EP, Vandenberg SR, Van Meir EG, von Deimling A, Zhang H, Crain D, Lau K, Mallery D, Morris S, Paulauskis J, Penny R, Shelton T, Sherman M, Yena P, Black A, Bowen J, Dicostanzo K, Gastier-Foster J, Leraas KM, Lichtenberg TM, Pierson CR, Ramirez NC, Taylor C, Weaver S, Wise L, Zmuda E, Davidsen T, Demchok JA, Eley G, Ferguson ML, Hutter CM, Mills Shaw KR, Ozenberger BA, Sheth M, Sofia HJ, Tarnuzzer R, Wang Z, Yang L, Zenklusen JC, Ayala B, Baboud J, Chudamani S, Jensen MA, Liu J, Pihl T, Raman R, Wan Y, Wu Y, Ally A, Auman JT, Balasundaram M, Balu S, Baylin SB, Beroukhim R, Bootwalla MS, Bowlby R, Bristow CA, Brooks D, Butterfield Y, Carlsen R, Carter S, Chin L, Chu A, Chuah E, Cibulskis K, Clarke A, Coetzee SG, Dhalla N, Fennell T, Fisher S, Gabriel S, Getz G, Gibbs R, Guin R, Hadjipanayis A, Hayes DN, Hinoue T, Hoadley K, Holt RA, Hoyle AP, Jefferys SR, Jones S, Jones CD, Kucherlapati R, Lai PH, Lander E, Lee S, Lichtenstein L, Ma Y, Maglinte DT, Mahadeshwar HS, Marra MA, Mayo M, Meng S, Meyerson ML, Mieczkowski PA, Moore RA, Mose LE, Mungall AJ, Pantazi A, Parfenov M, Park PJ, Parker JS, Perou CM, Protopopov A, Ren X, Roach J, Sabedot TS, Schein J, Schumacher SE, Seidman JG, Seth S, Shen H, Simons JV, Sipahimalani P, Soloway MG, Song X, Sun H, Tabak B, Tam A, Tan D, Tang J, Thiessen N, Triche T, Jr, Van Den Berg DJ, Veluvolu U, Waring S, Weisenberger DJ, Wilkerson MD, Wong T, Wu J, Xi L, Xu AW, Yang L, Zack TI, Zhang J, Aksoy BA, Arachchi H, Benz C, Bernard B, Carlin D, Cho J, DiCara D, Frazer S, Fuller GN, Gao J, Gehlenborg N, Haussler D, Heiman DI, Iype L, Jacobsen A, Ju Z, Katzman S, Kim H, Knijnenburg T, Kreisberg RB, Lawrence MS, Lee W, Leinonen K, Lin P, Ling S, Liu W, Liu Y, Liu Y, Lu Y, Mills G, Ng S, Noble MS, Paull E, Rao A, Reynolds S, Saksena G, Sanborn Z, Sander C, Schultz N, Senbabaoglu Y, Shen R, Shmulevich I, Sinha R, Stuart J, Sumer SO, Sun Y, Tasman N, Taylor BS, Voet D, Weinhold N, Weinstein JN, Yang D, Yoshihara K, Zheng S, Zhang W, Zou L, Abel T, Sadeghi S, Cohen ML, Eschbacher J, Hattab EM, Raghunathan A, Schniederjan MJ, Aziz D, Barnett G, Barrett W, Bigner DD, Boice L, Brewer C, Calatozzolo C, Campos B, Carlotti CG, Jr, Chan TA, Cuppini L, Curley E, Cuzzubbo S, Devine K, DiMeco F, Duell R, Elder JB, Fehrenbach A, Finocchiaro G, Friedman W, Fulop J, Gardner J, Hermes B, Herold-Mende C, Jungk C, Kendler A, Lehman NL, Lipp E, Liu O, Mandt R, McGraw M, McLendon R, McPherson C, Neder L, Nguyen P, Noss A, Nunziata R, Ostrom QT, Palmer C, Perin A, Pollo B, Potapov A, Potapova O, Rathmell WK, Rotin D, Scarpace L, Schilero C, Senecal K, Shimmel K, Shurkhay V, Sifri S, Singh R, Sloan AE, Smolenski K, Staugaitis SM, Steele R, Thorne L, Tirapelli DP, Unterberg A, Vallurupalli M, Wang Y, Warnick R, Williams F, Wolinsky Y, Bell S, Rosenberg M, Stewart C, Huang F, Grimsby JL, Radenbaugh AJ, Zhang J. Comprehensive, integrative genomic analysis of diffuse lower-grade gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2481–2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yan H, Parsons DW, Jin G, McLendon R, Rasheed BA, Yuan W, Kos I, Batinic-Haberle I, Jones S, Riggins GJ, Friedman H, Friedman A, Reardon D, Herndon J, Kinzler KW, Velculescu VE, Vogelstein B, Bigner DD. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:765–773. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunn GP, Andronesi OC, Cahill DP. From genomics to the clinic: biological and translational insights of mutant IDH1/2 in glioma. Neurosurg Focus. 2013;34:E2. doi: 10.3171/2012.12.FOCUS12355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metallo CM, Gameiro PA, Bell EL, Mattaini KR, Yang J, Hiller K, Jewell CM, Johnson ZR, Irvine DJ, Guarente L, Kelleher JK, Vander Heiden MG, Iliopoulos O, Stephanopoulos G. Reductive glutamine metabolism by IDH1 mediates lipogenesis under hypoxia. Nature. 2011;481:380–384. doi: 10.1038/nature10602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nobusawa S, Watanabe T, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H. IDH1 mutations as molecular signature and predictive factor of secondary glioblastomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6002–6007. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pusch S, Schweizer L, Beck AC, Lehmler JM, Weissert S, Balss J, Miller AK, von Deimling A. D-2-hydroxyglutarate producing neo-enzymatic activity inversely correlates with frequency of the type of isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 mutations found in glioma. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014;2:19. doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-2-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu W, Yang H, Liu Y, Yang Y, Wang P, Kim SH, Ito S, Yang C, Wang P, Xiao MT, Liu LX, Jiang WQ, Liu J, Zhang JY, Wang B, Frye S, Zhang Y, Xu YH, Lei QY, Guan KL, Zhao SM, Xiong Y. Oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate is a competitive inhibitor of alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:17–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noushmehr H, Weisenberger DJ, Diefes K, Phillips HS, Pujara K, Berman BP, Pan F, Pelloski CE, Sulman EP, Bhat KP, Verhaak RG, Hoadley KA, Hayes DN, Perou CM, Schmidt HK, Ding L, Wilson RK, Van Den Berg D, Shen H, Bengtsson H, Neuvial P, Cope LM, Buckley J, Herman JG, Baylin SB, Laird PW, Aldape K. Identification of a CpG island methylator phenotype that defines a distinct subgroup of glioma. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:510–522. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turcan S, Rohle D, Goenka A, Walsh LA, Fang F, Yilmaz E, Campos C, Fabius AW, Lu C, Ward PS, Thompson CB, Kaufman A, Guryanova O, Levine R, Heguy A, Viale A, Morris LG, Huse JT, Mellinghoff IK, Chan TA. IDH1 mutation is sufficient to establish the glioma hypermethylator phenotype. Nature. 2012;483:479–483. doi: 10.1038/nature10866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blackburn EH. Telomeres and telomerase: their mechanisms of action and the effects of altering their functions. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:859–862. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan P, Cao JL, Abuduwufuer A, Wang LM, Yuan XS, Lv W, Hu J. Clinical characteristics and prognostic significance of TERT promoter mutations in cancer: a cohort study and a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0146803. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ceccarelli M, Barthel FP, Malta TM, Sabedot TS, Salama SR, Murray BA, Morozova O, Newton Y, Radenbaugh A, Pagnotta SM, Anjum S, Wang J, Manyam G, Zoppoli P, Ling S, Rao AA, Grifford M, Cherniack AD, Zhang H, Poisson L, Carlotti CG, Jr, Tirapelli DP, Rao A, Mikkelsen T, Lau CC, Yung WK, Rabadan R, Huse J, Brat DJ, Lehman NL, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Zheng S, Hess K, Rao G, Meyerson M, Beroukhim R, Cooper L, Akbani R, Wrensch M, Haussler D, Aldape KD, Laird PW, Gutmann DH, Network TR, Noushmehr H, Iavarone A, Verhaak RG. Molecular profiling reveals biologically discrete subsets and pathways of progression in diffuse glioma. Cell. 2016;164:550–563. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arita H, Narita Y, Fukushima S, Tateishi K, Matsushita Y, Yoshida A, Miyakita Y, Ohno M, Collins VP, Kawahara N, Shibui S, Ichimura K. Upregulating mutations in the TERT promoter commonly occur in adult malignant gliomas and are strongly associated with total 1p19q loss. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126:267–276. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hiraga S, Ohnishi T, Izumoto S, Miyahara E, Kanemura Y, Matsumura H, Arita N. Telomerase activity and alterations in telomere length in human brain tumors. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2117–2125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cesare AJ, Reddel RR. Alternative lengthening of telomeres: models, mechanisms and implications. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:319–330. doi: 10.1038/nrg2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langford LA, Piatyszek MA, Xu R, Schold SC, Jr, Shay JW. Telomerase activity in human brain tumours. Lancet. 1995;346:1267–1268. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)91865-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heaphy CM, Subhawong AP, Hong SM, Goggins MG, Montgomery EA, Gabrielson E, Netto GJ, Epstein JI, Lotan TL, Westra WH, Shih Ie M, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Maitra A, Li QK, Eberhart CG, Taube JM, Rakheja D, Kurman RJ, Wu TC, Roden RB, Argani P, De Marzo AM, Terracciano L, Torbenson M, Meeker AK. Prevalence of the alternative lengthening of telomeres telomere maintenance mechanism in human cancer subtypes. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:1608–1615. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heaphy CM, de Wilde RF, Jiao Y, Klein AP, Edil BH, Shi C, Bettegowda C, Rodriguez FJ, Eberhart CG, Hebbar S, Offerhaus GJ, McLendon R, Rasheed BA, He Y, Yan H, Bigner DD, Oba-Shinjo SM, Marie SK, Riggins GJ, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Hruban RH, Maitra A, Papadopoulos N, Meeker AK. Altered telomeres in tumors with ATRX and DAXX mutations. Science. 2011;333:425. doi: 10.1126/science.1207313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lovejoy CA, Li W, Reisenweber S, Thongthip S, Bruno J, de Lange T, De S, Petrini JH, Sung PA, Jasin M, Rosenbluh J, Zwang Y, Weir BA, Hatton C, Ivanova E, Macconaill L, Hanna M, Hahn WC, Lue NF, Reddel RR, Jiao Y, Kinzler K, Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Meeker AK, Consortium ALTSC Loss of ATRX, genome instability, and an altered DNA damage response are hallmarks of the alternative lengthening of telomeres pathway. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002772. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartzentruber J, Korshunov A, Liu XY, Jones DT, Pfaff E, Jacob K, Sturm D, Fontebasso AM, Quang DA, Tonjes M, Hovestadt V, Albrecht S, Kool M, Nantel A, Konermann C, Lindroth A, Jager N, Rausch T, Ryzhova M, Korbel JO, Hielscher T, Hauser P, Garami M, Klekner A, Bognar L, Ebinger M, Schuhmann MU, Scheurlen W, Pekrun A, Fruhwald MC, Roggendorf W, Kramm C, Durken M, Atkinson J, Lepage P, Montpetit A, Zakrzewska M, Zakrzewski K, Liberski PP, Dong Z, Siegel P, Kulozik AE, Zapatka M, Guha A, Malkin D, Felsberg J, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Ichimura K, Collins VP, Witt H, Milde T, Witt O, Zhang C, Castelo-Branco P, Lichter P, Faury D, Tabori U, Plass C, Majewski J, Pfister SM, Jabado N. Driver mutations in histone H3.3 and chromatin remodelling genes in paediatric glioblastoma. Nature. 2012;482:226–231. doi: 10.1038/nature10833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldberg AD, Banaszynski LA, Noh KM, Lewis PW, Elsaesser SJ, Stadler S, Dewell S, Law M, Guo X, Li X, Wen D, Chapgier A, DeKelver RC, Miller JC, Lee YL, Boydston EA, Holmes MC, Gregory PD, Greally JM, Rafii S, Yang C, Scambler PJ, Garrick D, Gibbons RJ, Higgs DR, Cristea IM, Urnov FD, Zheng D, Allis CD. Distinct factors control histone variant H3.3 localization at specific genomic regions. Cell. 2010;140:678–691. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis PW, Elsaesser SJ, Noh KM, Stadler SC, Allis CD. Daxx is an H3.3-specific histone chaperone and cooperates with ATRX in replication-independent chromatin assembly at telomeres. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14075–14080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008850107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiao Y, Killela PJ, Reitman ZJ, Rasheed AB, Heaphy CM, de Wilde RF, Rodriguez FJ, Rosemberg S, Oba-Shinjo SM, Nagahashi Marie SK, Bettegowda C, Agrawal N, Lipp E, Pirozzi C, Lopez G, He Y, Friedman H, Friedman AH, Riggins GJ, Holdhoff M, Burger P, McLendon R, Bigner DD, Vogelstein B, Meeker AK, Kinzler KW, Papadopoulos N, Diaz LA, Yan H. Frequent ATRX, CIC, FUBP1 and IDH1 mutations refine the classification of malignant gliomas. Oncotarget. 2012;3:709–722. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kannan K, Inagaki A, Silber J, Gorovets D, Zhang J, Kastenhuber ER, Heguy A, Petrini JH, Chan TA, Huse JT. Whole-exome sequencing identifies ATRX mutation as a key molecular determinant in lower-grade glioma. Oncotarget. 2012;3:1194–1203. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu XY, Gerges N, Korshunov A, Sabha N, Khuong-Quang DA, Fontebasso AM, Fleming A, Hadjadj D, Schwartzentruber J, Majewski J, Dong Z, Siegel P, Albrecht S, Croul S, Jones DT, Kool M, Tonjes M, Reifenberger G, Faury D, Zadeh G, Pfister S, Jabado N. Frequent ATRX mutations and loss of expression in adult diffuse astrocytic tumors carrying IDH1/IDH2 and TP53 mutations. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124:615–625. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sorensen MD, Dahlrot RH, Boldt HB, Hansen S, Kristensen BW. Tumour-associated microglia/macrophages predict poor prognosis in high-grade gliomas and correlate with an aggressive tumour subtype. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2018;44:185–206. doi: 10.1111/nan.12428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dahlrot RH, Kristensen BW, Hjelmborg J, Herrstedt J, Hansen S. A population-based study of high-grade gliomas and mutated isocitrate dehydrogenase 1. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:31–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferreira MSV, Crysandt M, Braunschweig T, Jost E, Voss B, Bouillon AS, Knuechel R, Brummendorf TH, Beier F. Presence of TERT promoter mutations is a secondary event and associates with elongated telomere length in myxoid liposarcomas. Int J Mol Sci. 2018 doi: 10.3390/ijms19020608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ventura Ferreira MS, Bienert M, Muller K, Rath B, Goecke T, Oplander C, Braunschweig T, Mela P, Brummendorf TH, Beier F, Neuss S. Comprehensive characterization of chorionic villi-derived mesenchymal stromal cells from human placenta. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9:28. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0757-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hummel S, Ventura Ferreira MS, Heudobler D, Huber E, Fahrenkamp D, Gremse F, Schmid K, Muller-Newen G, Ziegler P, Jost E, Blasco MA, Brummendorf TH, Holler E, Beier F. Telomere shortening in enterocytes of patients with uncontrolled acute intestinal graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2015;126:2518–2521. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-633289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ziegler S, Schettgen T, Beier F, Wilop S, Quinete N, Esser A, Masouleh BK, Ferreira MS, Vankann L, Uciechowski P, Rink L, Kraus T, Brummendorf TH, Ziegler P. Accelerated telomere shortening in peripheral blood lymphocytes after occupational polychlorinated biphenyls exposure. Arch Toxicol. 2017;91:289–300. doi: 10.1007/s00204-016-1725-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beier F, Foronda M, Martinez P, Blasco MA. Conditional TRF1 knockout in the hematopoietic compartment leads to bone marrow failure and recapitulates clinical features of dyskeratosis congenita. Blood. 2012;120:2990–3000. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-418038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beier F, Balabanov S, Buckley T, Dietz K, Hartmann U, Rojewski M, Kanz L, Schrezenmeier H, Brummendorf TH. Accelerated telomere shortening in glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-negative compared with GPI-positive granulocytes from patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) detected by proaerolysin flow-FISH. Blood. 2005;106:531–533. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beier F, Martinez P, Blasco MA. Chronic replicative stress induced by CCl4 in TRF1 knockout mice recapitulates the origin of large liver cell changes. J Hepatol. 2015;63:446–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beier F, Masouleh BK, Buesche G, Ventura Ferreira MS, Schneider RK, Ziegler P, Wilop S, Vankann L, Gattermann N, Platzbecker U, Giagounidis A, Gotze KS, Nolte F, Hofmann WK, Haase D, Kreipe H, Panse J, Blasco MA, Germing U, Brummendorf TH. Telomere dynamics in patients with del (5q) MDS before and under treatment with lenalidomide. Leuk Res. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Birner P, Pusch S, Christov C, Mihaylova S, Toumangelova-Uzeir K, Natchev S, Schoppmann SF, Tchorbanov A, Streubel B, Tuettenberg J, Guentchev M. Mutant IDH1 inhibits PI3K/Akt signaling in human glioma. Cancer. 2014;120:2440–2447. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Begna KH, Patnaik MM, Zblewski DL, Finke CM, Laborde RR, Wassie E, Schimek L, Hanson CA, Gangat N, Wang X, Pardanani A. A pilot study of the telomerase inhibitor imetelstat for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:908–919. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baerlocher GM, Oppliger Leibundgut E, Ottmann OG, Spitzer G, Odenike O, McDevitt MA, Roth A, Daskalakis M, Burington B, Stuart M, Snyder DS. Telomerase inhibitor imetelstat in patients with essential thrombocythemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:920–928. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heidenreich B, Rachakonda PS, Hosen I, Volz F, Hemminki K, Weyerbrock A, Kumar R. TERT promoter mutations and telomere length in adult malignant gliomas and recurrences. Oncotarget. 2015;6:10617–10633. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao K, Li G, Qu Y, Wang M, Cui B, Ji M, Shi B, Hou P. TERT promoter mutations and long telomere length predict poor survival and radiotherapy resistance in gliomas. Oncotarget. 2016;7:8712–8725. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang S, Chen Y, Qu F, He S, Huang X, Jiang H, Jin T, Wan S, Xing J. Association between leukocyte telomere length and glioma risk: a case-control study. Neuro-Oncol. 2014;16:505–512. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pekmezci M, Rice T, Molinaro AM, Walsh KM, Decker PA, Hansen H, Sicotte H, Kollmeyer TM, McCoy LS, Sarkar G, Perry A, Giannini C, Tihan T, Berger MS, Wiemels JL, Bracci PM, Eckel-Passow JE, Lachance DH, Clarke J, Taylor JW, Luks T, Wiencke JK, Jenkins RB, Wrensch MR. Adult infiltrating gliomas with WHO 2016 integrated diagnosis: additional prognostic roles of ATRX and TERT. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;133:1001–1016. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1690-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mukherjee J, Johannessen T-CA, Ohba S, Chow TT, Jones LE, Pandita A, Pieper RO. Mutant IDH1 cooperates with ATRX loss to drive the alternative lengthening of telomere (ALT) phenotype in glioma. Cancer Res. 2018 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-17-2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gocha AR, Nuovo G, Iwenofu OH, Groden J. Human sarcomas are mosaic for telomerase-dependent and telomerase-independent telomere maintenance mechanisms: implications for telomere-based therapies. Am J Pathol. 2013;182:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kovatcheva M, Liao W, Klein ME, Robine N, Geiger H, Crago AM, Dickson MA, Tap WD, Singer S, Koff A. ATRX is a regulator of therapy induced senescence in human cells. Nat Commun. 2017;8:386. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00540-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koschmann C, Calinescu AA, Nunez FJ, Mackay A, Fazal-Salom J, Thomas D, Mendez F, Kamran N, Dzaman M, Mulpuri L, Krasinkiewicz J, Doherty R, Lemons R, Brosnan-Cashman JA, Li Y, Roh S, Zhao L, Appelman H, Ferguson D, Gorbunova V, Meeker A, Jones C, Lowenstein PR, Castro MG. ATRX loss promotes tumor growth and impairs nonhomologous end joining DNA repair in glioma. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:328ra328. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac8228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ohba S, Mukherjee J, Johannessen TC, Mancini A, Chow TT, Wood M, Jones L, Mazor T, Marshall RE, Viswanath P, Walsh KM, Perry A, Bell RJ, Phillips JJ, Costello JF, Ronen SM, Pieper RO. Mutant IDH1 expression drives TERT promoter reactivation as part of the cellular transformation process. Cancer Res. 2016;76:6680–6689. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 1 (JPEG 291 kb) Supplementary Figure S1. (A) Representative images of the immunofluorescence-based strategy used for CS-TL quantification in single tumor cells; tumor areas were identified by H&E staining, then sections were Q-FISH stained in combination with alfa-SMA immunofluorescence for identification of vessel cells (non-tumor cells that served as internal control). DAPI was used for nuclear counterstain of all cells (magnification 756x). (B) Telomere length in glioma patients according to WHO tumor grade. (C) Kaplan Meier survival curve of astrocytoma patients stratified based on IDH1 mutational status.

Supplementary material 2 (JPEG 166 kb) Supplementary Figure S2. (A) Representative chromatograms showing TERT promoter status (wildtype vs. C228T or C250T mutation) in the glioma tumors after Sanger sequencing.

Supplementary material 3 (JPEG 406 kb) Supplementary Figure S3. (A) Representative images of the colony-forming unit assay of non-induced (-) and doxycycline-induced (+) IDH1WT and IDH1R132H cell lines (scale: 1.7 cm). (B) Representative images of the agar assay of non-induced (-) and doxycycline induced (+) IDH1WT and IDH1R132H cell lines (magnification 50x). (C) Representative images of Q-FISH stained doxycycline induced IDH1WT and IDH1R132H cell lines after one (PD1) and five (PD5) population doublings in culture (magnification 756x); (D) Representative chromatograms showing absence of TERTpmut by Sanger sequencing in doxycycline induced IDH1WT and IDH1R132H cell lines after three (PD3) and 27 (PD27) population doublings in culture.