Abstract

Pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) proteins with C-terminal DYW domains are present in organisms that undergo C-to-U editing of organelle RNA transcripts. PPR domains act as specificity factors through electrostatic interactions between a pair of polar residues and the nitrogenous bases of an RNA target. DYW-deaminase domains act as the editing enzyme. Two moss (Physcomitrella patens) PPR proteins containing DYW-deaminase domains, PPR65 and PPR56, can convert Cs to Us in cognate, exogenous RNA targets co-expressed in Escherichia coli. We show here that purified, recombinant PPR65 exhibits robust editase activity on synthetic RNAs containing cognate, mitochondrial PpccmFC sequences in vitro, indicating that a PPR protein with a DYW domain is solely sufficient for catalyzing C-to-U RNA editing in vitro. Monomeric fractions possessed the highest conversion efficiency, and oligomeric fractions had reduced activity. Inductively coupled plasma (ICP)–MS analysis indicated a stoichiometry of two zinc ions per highly active PPR65 monomer. Editing activity was sensitive to addition of zinc acetate or the zinc chelators 1,10-o-phenanthroline and EDTA. Addition of ATP or nonhydrolyzable nucleotide analogs stimulated PPR65-catalyzed RNA-editing activity on PpccmFC substrates, indicating potential allosteric regulation of PPR65 by ATP. Unlike for bacterial cytidine deaminase, addition of two putative transition-state analogs, zebularine and tetrahydrouridine, failed to disrupt RNA-editing activity. RNA oligonucleotides with a single incorporated zebularine also did not disrupt editing in vitro, suggesting that PPR65 cannot bind modified bases due to differences in the structure of the active site compared with other zinc-dependent nucleotide deaminases.

Keywords: RNA editing, mitochondria, organelle, metalloenzyme, metal ion-protein interaction, C-to-U editing, deaminase, DYW domain, pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR), PPR65

Introduction

Base modification of nucleic acids occurs extensively in many eukaryotes and deaminase enzymes have diversified through evolution into several unique editing complexes (1). Sequence specific C-to-U and A-to-I editing enzymes are currently being developed into genetic manipulation tools that might be adapted into future gene therapies (2). Although the substrates vary, C-to-U and A-to-I editing utilize a zinc-dependent mechanism in common with bacterial cytidine deaminase (3). Also, similar transition state analogs have been shown to reduce activity for Escherichia coli cytidine deaminase (2), adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADAR)2 (26), and Apolipoprotein B mRNA Editing Enzyme Catalytic Subunit 3G (APOBEC3G) (27). The largely plant-specific organelle C-to-U RNA-editing mechanism might make an attractive tool for transcript editing, but development has been limited by the paucity of information about its mechanism and requirements.

In land plants, a series of nuclear factors are required for sequence-specific C-to-U RNA editing of organelle transcripts (4). Only a single nucleotide deaminase domain has been linked to C-to-U RNA editing in plants and has been named the DYW domain after the most common C-terminal residues (aspartate, tyrosine, and tryptophan) (5). The DYW-deaminase domain contains a conserved zinc-binding motif (HXE, CXXC) in common with other editing deaminases and has long been theorized to be the enzymatic component of the plant organelle editing complex called the editosome (5, 6). Further supporting the hypothesis that the DYW is an editing enzyme include its co-evolution with C-to-U RNA editing (7), bound zinc ligands (8, 9), and absence of function after mutation of catalytic residues (8, 10–12).

The DYW-deaminase is typically a C-terminal domain linked to an N-terminal pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) domain tract known to bind RNAs in a sequence-specific manner (13) and X-ray crystal structures have elucidated the particular electrostatic interactions between two polar amino acids and the ribobases (14). Studies have shown that changing the two base-interacting polar residues can change nucleotide specificity in a predictable way (13, 14). Plant PPR-DYW proteins are attractive research targets in terms of both base modification and engineering novel sequence-specific RNA-binding proteins.

In E. coli, expression of the two PPR proteins called PPR65 and PPR56 from the moss Physcomitrella patens leads to the editing of co-expressed respective targets from ccmFC and nad3/nad4 transcripts (12). Although strongly implicating the DYW domain as the editing deaminase, the ubiquity of cytidine deaminases, in part due to their role in the nucleotide salvage pathways, necessitated further investigation to eliminate all doubt about the function of the domain. Skepticism about the editing function of the domain relates to the fact that despite the discovery of several editing factors beginning in 2005 (15–18), recombinant proteins with DYW-deaminase domains previously purified from higher plants have only been linked to RNA cleavage and not RNA editing in vitro (19).

Complementation studies that expressed truncated PPR transgenes without the proposed catalytic region of the DYW domain in genetic knock-out plants have not simplified understanding of the catalytic mechanism. Paradoxically, some C-terminal PPR-truncated transgene variants lacking catalytic domains were fully capable of complementing genetic knock-out lines (9, 19, 20). C-terminal truncation of the DYW-deaminase domain could not proceed past a projected β-strand region of conserved sequence named the PG-box and complement mutants. This suggests the PG-box portion of the DYW-deaminase domain might be critical for recruitment of a functional DYW protein or enzyme (9). Many higher plant-editing factors lack the putative catalytic component of the DYW-deaminase while still encoding the PG box and were previously classified as the E and E+ PPR proteins based on the location of the truncation (5). One E-class PPR, CRR4, was the first PPR demonstrated to be necessary for RNA editing (18). Later a DYW protein lacking a lengthy PPR tract called DYW1 was found to bind to CRR4 and catalyze activity (21). Therefore many DYW-deaminases apparently function in native heterocomplexes with PPR proteins that specify the RNA target.

Structural studies of the DYW-deaminase have been complicated by the absence of a solved crystal structure and limited homology with other nucleotide deaminases with solved structures. However, studies have included the DYW-deaminase in a superfamily of hydrolytic deaminases based on metal-chelating residues and tertiary structure predications (22). One of the reasons for the difficulty in predicting the structure of the DYW-deaminase has to do with the unique C-terminal region. The C terminus lacks one of the nucleotide-interacting loops proposed for activation-induced cytidine deaminase (23), possesses a pair of unique conserved cysteines that likely coordinate an additional zinc residue (9), and ends in the C-terminal DYW trio of amino acids residues with unknown roles. Two zinc ions per recombinant DYW-deaminase domain containing protein were observed using electrospray ionization-MS (ESI-MS) and inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) for the editing factor lacking PPR domains called DYW1 and from the PPR editing factor ELI1 (9); although alternatively a separate group using ICP-MS found a quantum of zinc consistent with only a single zinc ion per DYW1 protein (8). Unfortunately, neither study reported editing activity from expressed proteins. Mutations at the canonical deaminase zinc-coordinating residues and active site glutamate impact editing efficiency in transgenic plants (8, 10, 11) as well as mutations in the second zinc site (10).

In this study, editing activity of purified recombinant PPR65 was assayed on substrates with sequences from the only known mitochondrial editing site target in ccmFC transcripts. The recombinant protein PPR65 was solely sufficient for C-to-U activity in vitro. Activity was highest in monomeric fractions with a molar ratio of two zinc ions per peptide. Purified PPR65 fractions with mutations in the active site co-fractionated with large molecular weight standards and did not catalyze RNA editing on PpccmFC substrates under equivalent conditions as WT PPR65. Our results definitively indicate that the DYW-deaminase domain is a zinc-dependent enzyme and the sole catalytic component of the editosome. Because PPR65 is itself necessary and sufficient our work supports its applicability to modification to design a new biotechnology tool that can make desired nucleotide changes. Last, we provide evidence that RNA editing might be regulated by the adenylate energy charge of the organelle through allostery and is not inhibited by the addition of putative transition state analogs zebularine hydrate and tetrahydrouridine.

Results

Identification of PPR65 editing activity and optimization

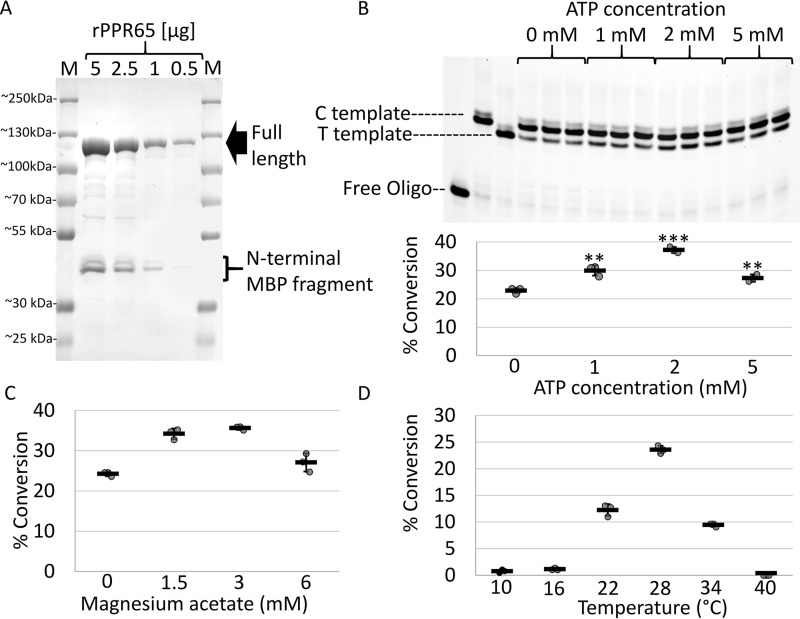

Recombinant PPR65 was initially purified using a two-step affinity chromatography approach exploiting the N-terminal His6 tag and maltose-binding protein (MBP) domains. During purification an N-terminal MBP fragment, most likely a product of nascent proteolytic activity, was observed to co-purify with the full-length PPR65 (Fig. 1A). Eleven μg of the protein fraction was added to 1 fmol of RNA with sequences around PpccmFC, the only native target of PPR65, in 12.5-μl reactions similar to those used for RNA-editing assays with maize extracts (24). Addition of this initial PPR65 preparation yielded 33% conversion over 2.5 h at 28 °C. To optimize the assay, experiments established the optimal ATP concentration at 2 mm, magnesium acetate concentration at 3 mm, and temperature at 28 °C (Fig. 1). The modified conditions were able to support conversion of around 38% of 80 pm to 4 nm of input substrate (Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

Recombinant PPR65 edits a PpccmFC RNA substrate and is sensitive to ATP and Mg2+ concentrations as well as temperature. A, an image from Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE indicates the purity of the PPR65 fraction after two rounds of affinity chromatography and the N-terminal degradation product. Protein marker lanes are labeled M. B, top, an image of the 20% acrylamide, 6 m urea gel containing size-separated fluorescent PPE products used to quantify editing conversion from triplicate reactions in vitro. Below, a XY-scatter plot indicates percent conversion of RNA substrates from editing reactions assayed with varying ATP concentrations. Two-tailed Student's test p values represent divergence from 0 mm ATP control reactions. **, p < 0.01, and ***, p < 0.005. XY-scatter plots display the percent conversion calculated for reactions containing various Mg2+ concentrations (C) and temperature conditions (D). Black bars represent the mean ± S.D. based on three independent experiments.

Purification and activity of monomeric PPR65 versus heterogeneous oligomers

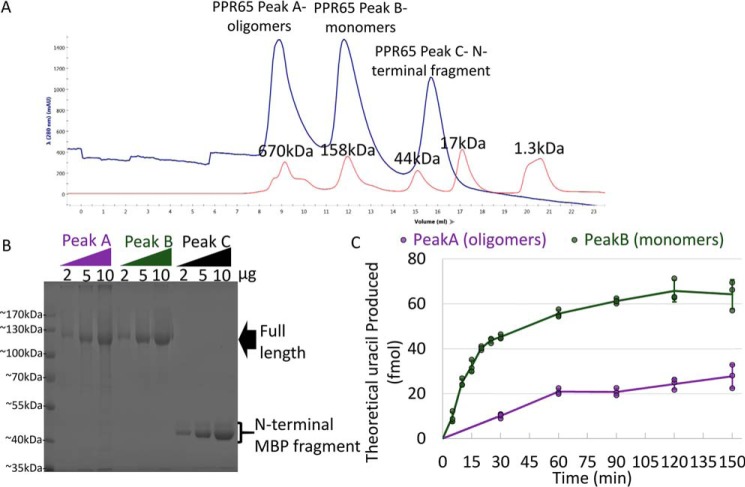

Initial purifications suffered from co-purification of the common N-terminal MBP fragment, and the oligomerization state of the initial protein was unresolved. An additional gel filtration chromatography step resolved these issues and indicated that approximately one-half of the purified recombinant PPR65 was monomeric (peak B), whereas the other half was in high molecular weight complexes that exceeded the linear resolving size of the column (peak A). Both peaks under denaturing conditions resolved to the same size band (Fig. 2, Fig. S2). Editing activity for each peak was measured during a time course experiment in vitro. Activity was significantly higher for monomeric PPR65 (peak B) versus high molecular weight complexed forms (peak A) (Fig. 2). For early time points, each fraction deaminated RNA substrates in a linear fashion reminiscent of Michaelis-Menten kinetics, allowing estimates for specific activity. The specific activity of peak A was measured at 58 fmol min−1 mg−1 compared with a value of 335 fmol min−1 mg− 1 for peak B. Thus monomers demonstrate roughly about 6 times more activity than the high molecular weight complexes. On a percent conversion basis, purified monomeric PPR65 converted around 60–70% of the initial substrate. Dilution of the enzyme reduced editing conversion and editing could not be measured in substrate-saturated conditions (Fig. S2).

Figure 2.

Purified rPPR65 was discovered to be present in active fractions correlating with a native monomeric mass and larger fractions. A, absorption at 280 nm is shown for various size exclusion chromatography fractions during rPPR65 purification (blue) and a separate run using the same column and molecular weight standards (red). Protein peaks from rPPR65 purification are labeled peak A, peak B, and peak C. B, below, an image of a Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE used to investigate purity of pooled fractions from peaks A, B, and C. C, a XY-scatter plot shows production of uracil over time in triplicated editing assays in vitro using peak A and peak B and PpccmFC substrates. Lines represent the mean ± S.D. values at each time point based on three independent experiments.

High molecular weight complexes might be a result of RNA contamination, protein aggregation, or native higher order complexes. The ratio of absorbance at 260/280 was obtained to estimate the quantity of nucleic acids purified with PPR65. The 260/280 ratios of 0.61 for Peak A and 0.53 for Peak B indicated an absence of large quantities of RNA in PPR65 fractions. A multiangle light scattering (MALS) device linked to a gel filtration column with a significantly higher resolution for higher molecular weight species was used to get a better estimate of the composition of the protein oligomers in peak A. Light scattering at three peaks defined by changes in the UV spectra indicated that the majority of PPR65 was in polydispersed heterogenous oligomers (Fig. S3). A small shoulder of the UV spectra represented a protein species with a molecular mass estimated to be around 2.580 × 106 Da consistent with a low confidence 20-mer (Fig. S3). Therefore, roughly half of recombinant PPR65 purified was in heterogenous aggregates of reduced activity, devoid of significant nucleic acid.

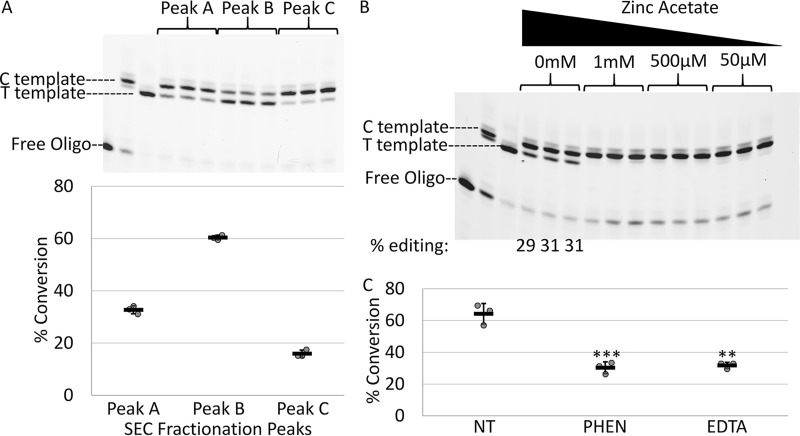

PPR65 activity is sensitive to the addition or depletion of zinc ions

Editing was measured in a fixed end point assay of 2.5 h to compare RNA-editing activity following a series of treatments. Peak B again demonstrated a greater capacity to edit input RNA (Fig. 3A). Additional zinc ions were added to 2.5-h reactions catalyzed by monomeric PPR65 and editing was assayed on PpccmFC substrates in vitro. Editing activity was abolished by addition of 50 μm, 500 μm, and 1 mm zinc acetate (Fig. 3B). Zinc chelators 1,10-o-phenanthroline (PHEN) and EDTA were added to monomeric PPR65 reactions with PpccmFC in vitro. Each inhibitor was able to reduce editing conversion from 75 to ∼30% at a concentration of 8 mm (Fig. 3C). Editing activity by PPR65 is sensitive to both addition of zinc ions and depletion of zinc ions consistent with other zinc-dependent nucleotide deaminases.

Figure 3.

Recombinant PPR65 is sensitive to exogenous zinc and zinc chelators. A, an image is shown of PPE products produced from amplified cDNA product templates reverse transcribed from edited/unedited RNAs after a 2.5-h fixed end point editing assay using PPR65 peaks A, B, and C. Below, a XY-scatter plot displays the % conversion calculated for triplicated editing reactions from the gel image shown above. B, an image is displayed of PPE products resulting from editing assays with various zinc acetate concentrations using doubly affinity purified rPPR65. RNA editing was only observed for the 0 mm negative control with percentages shown below the gel image. C, percent conversion for reactions with the addition of 8 mm PHEN and 8 mm EDTA and no treatment (NT) are displayed on a XY-scatter plot. Two-tailed Student's test p values represent divergence from NT control reactions. **, p < 0.01, and ***, p < 0.005. Black bars represent the mean ± S.D. value based on three independent experiments.

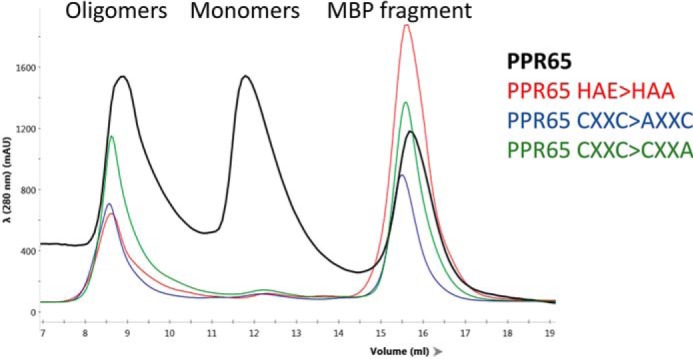

Mutations in catalytic residues leads to oligomerization/aggregation and reduced zinc binding

Recombinant PPR65 with a change in a zinc-binding residue (PPR65 CXXC>AXXC and PPR65 CXXC>CXXA) as well as in the catalytic glutamate (PPR65 HAE>HAA) were expressed and purified. Unfortunately, very low quantities of protein were observed in peaks that correlate with the estimated molar mass of monomers (Fig. 4). Direct comparisons with monomeric WT PPR65 were not possible. Editing activity was not observed for PPR HAE>HAA oligomeric fractions. The observation of inactive soluble aggregates indicate that mutations destabilize the native quaternary structure of PPR65.

Figure 4.

Recombinant PPR65 with mutations in the proposed active site result in oligomeric PPR65 fractions. Absorbance in arbitrary units at 280 nm versus fraction volume are displayed for 4 representative size exclusion fractionations of doubly purified affinity purified rPPR65, rPPR65 HAE>HAA, rPPR65 CXXC>AXXC, and rPPR65 CXXC>CXXA.

Zinc ions were quantified for each unmodified PPR65 fraction and an oligomeric fraction of PPR65 CXXC>AXXC using ICP-MS and related to the quantity of protein as determined using the estimated extinction coefficient and Beer's Law. For SEC fractions from unmodified PPR65, molar ratios for peak A exceeded 3 zinc ions per PPR65 molecule, peak B contained ∼2 zinc ions per PPR65 monomer, and peak C had very small quantities of zinc compared with protein (Table 1). Thus PPR65 fractions that were most active were monomeric with 2 zinc ion ligands. Oligomeric PPR65 with an amino acid change in single zinc-binding site CXXC>AXXC reduced zinc binding to a single zinc ion per polypeptide (Table 1).

Table 1.

ICP-MS analysis of rPPR65 and rPPR65 CXXC>AXXC size exclusion purification peaks and calculated molar ratios

The denaturation procedure was performed separately for experimental replicates.

| Fraction | Zinc |

Zinc from protein | Absorbance, 280 nm |

Protein | Molar ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Averagea | S.D. | Averageb | S.D. | zinc/protein | |||

| ng/ppb | m | m | |||||

| PPR65 peak A | 1659.658 | 12.006 | 2.336E-05 | 1.042 | 0.047 | 7.058E-06 | 3.311 |

| PPR65 peak B | 933.395 | 6.034 | 1.225E-05 | 0.939 | 0.034 | 6.364E-06 | 1.926 |

| PPR65 peak B | 994.669 | 11.028 | 1.319E-05 | 0.939 | 0.034 | 6.364E-06 | 2.074 |

| PPR65C>AXXC | 423.841 | 5.768 | 6.482E-06 | 0.979 | 0.179 | 6.633E-06 | 0.977 |

| PPR65C>AXXC | 426.209 | 6.937 | 6.518E-06 | 0.979 | 0.179 | 6.633E-06 | 0.983 |

| PPR65 peak C | 192.910 | 3.505 | 9.328E-07 | 0.678 | 0.032 | 1.022E-05 | 0.091 |

| Buffer control | 131.923 | 4.077 | |||||

a Zinc measurements were obtained from 3 experimental replicates after background correction.

b Each sample was measured nine times with background correction.

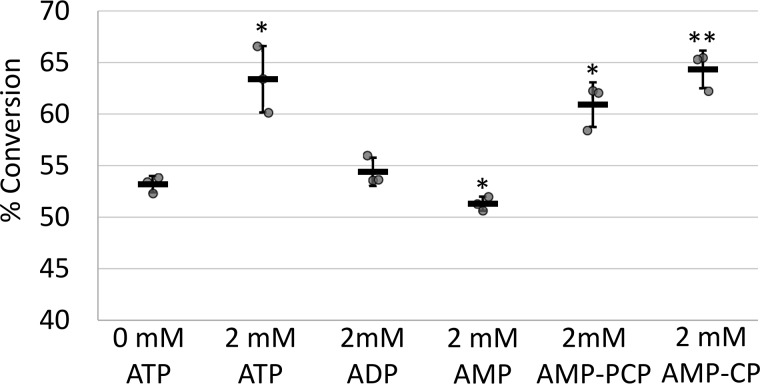

Editing activity is stimulated rather than being diminished by nonhydrolyzable ATP analogs in reactions catalyzed by PPR65 and maize extracts

Optimization of PPR65-editing activity revealed that RNA editing is not dependent on ATP but activity was stimulated by addition of ATP (Fig. 1). The identification of ATP stimulation was not anticipated because ATP coupling is absent from the deaminase molecular mechanism and the purified PPR65 lacks the larger editing complex in higher plants projected to hydrolyze ATP to relax RNA secondary structure. ATP stimulation is in line with observations made using chloroplast and mitochondrial extracts at equivalent ATP concentrations (25–27). RNA-editing activity was assayed with the addition of ATP, ADP, and AMP as well as nonhydrolyzable analogs AMP-PCP and AMP-CP to reactions containing PPR65 and cognate substrate PpccmFC. No significant change in editing activity was observed for the addition of ADP; AMP addition resulted in a minor reduction of activity; whereas ATP as well as nonhydrolysable analogs AMP-PCP and AMP-CP enhanced RNA editing (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Addition of ATP and nonhydrolyzable analogs increase RNA-editing activity. Editing reactions were set up in triplicate with either no nucleotide added or with the addition of 2 mm ATP, ADP, AMP, AMP-PCP, and AMP-CP. A XY-scatter plot shows percent conversion for each reaction. Black bars represent the mean ± S.D. value. Two-tailed Student's test p values represent divergence from 0 mm ATP control reactions. *, p < 0.05, and **, p < 0.01.

Modified nucleotides were used to determine whether the effects on RNA editing extend to maize chloroplast extracts using the maize-editing substrate ZmrpoC2 C2774. Reactions exhibited increased editing when 1 mm of slowly hydrolyzable ATPγS or ATP were added to reactions, although high levels of ATP led to diminished activity (Fig. S4). Addition of 2 mm nonhydrolysable analogs AMP-CP and AMP-PCP did not inhibit highly active chloroplast extract-catalyzed RNA-editing reactions in vitro (Fig. S4).

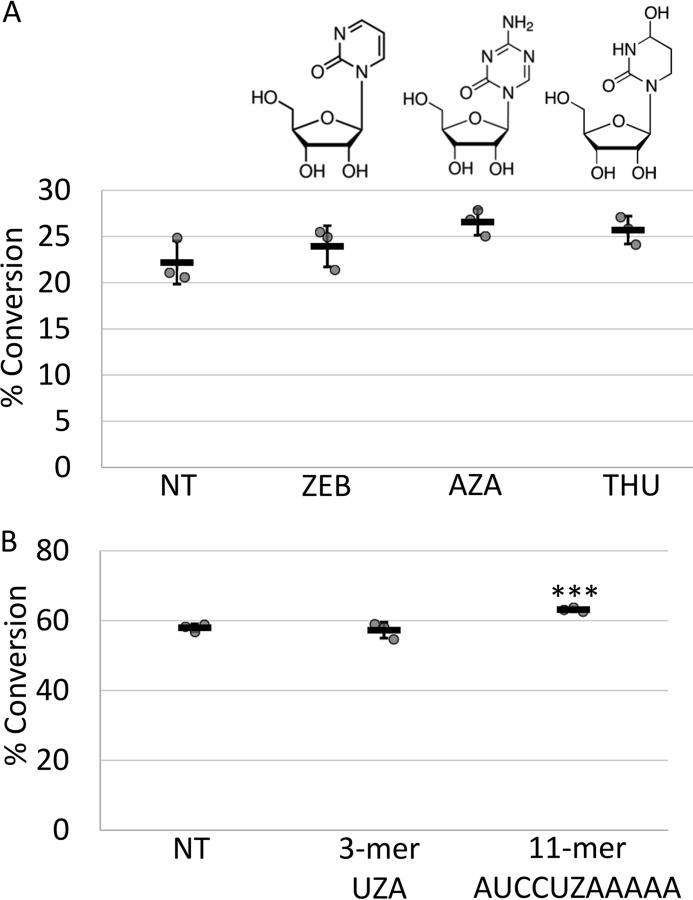

DYW-dependent C-to-U RNA editing is not inhibited by putative TSAs tetrahydrouridine or zebularine

The fundamental RNA-editing mechanism used by DYW-deaminase domains is projected to be shared with other zinc-dependent nucleotide deaminases. Cytidine deaminase from E. coli is very sensitive to the addition of transition state analogs zebularine hydrate and tetrahydrouridine (3). Due to interest into the RNA-editing mechanism predating the simplified PPR65 in vitro system, editing was assayed for ZmrpoC2 C2774 substrates using maize chloroplast extract-catalyzed reactions with added zebularine, 5-azacytdine, cytidine, CMP, and tetrahydrouridine. Reduction of editing was only observed after addition of CMP but not putative transition state analogs in concentrations that varied from 100 nm to 10 mm depending on experiment (Fig. S5).

It is possible the nucleosides might have been subject to side reactions given the complex composition of the chloroplast reactions. Therefore, we added nucleosides zebularine, 5-deazacytidine, and tetrahydrouridine at a final concentration of 8 mm to editing reactions containing PPR65 and assayed conversion efficiency. We found addition of putative inhibitors did not appreciably reduce RNA editing of PpccmFC in a 2.5-h fixed end point assay (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Addition of putative transition state inhibitors failed to inhibit DYW-dependent C-to-U RNA editing catalyzed by PPR65 on PpccmFC. A, XY-scatter plots represent percent conversion of PpccmFC substrates calculated from triplicate PPR65-catalyzed reactions with either no treatment (NT), zebularine (ZEB), deazacytidine (AZA), or tetrahydrouridine (THU). B, RNA oligonucleotides (3-mer and 11-mer) with incorporated zebularine (Z) with the sequence shown were added to PPR65 reactions at 1000:1 molar ratio to substrates. Percent conversion was calculated after 2.5 h and represented by the XY-scatter plot. Black bars represent the mean ± S.D. value. Two-tailed Student's test p values represent divergence from NT control reactions. ***, p < 0.005.

One interpretation of the lack of inhibition was that possibly the putative TSA nucleosides were not properly entering the active site. Inhibition of APOBEC3G and ADAR required the incorporation of TSAs into appropriate nucleic acid substrates (28, 29). Therefore we purchased synthesized RNA oligonucleotides with zebularine incorporated at the middle position of a 3-mer (Cy5-UZA) due to the strong bias for a 5′U and 3′A for organelle-editing sites. We also obtained longer chains of nucleotides that consisted of 20 nucleotides of upstream sequence from maize-editing sites rps14 C80 and rpl20 C308, a zebularine ribobase in place of the cytidine of the editing site, and 5 nucleotides of downstream sequence. The 3-mer was incapable of acting as an inhibitor for maize-catalyzed reactions on ZmrpoC2 C2774 substrates (Fig. S5). Addition of the longer, 26-mer, zebularine-incorporated oligonucleotides whether cognate (rps14 C80) or noncognate (rpl20 C308) did not inhibit activity on Zmrps14 C80 substrates (Fig. S5).

Editing was then assayed using the simplified PPR65 assay on PpccmFC substrates in the presence of 1000:1 molar excess of fluorescently labeled, 3-mer (Cy5-UZA-3′) and an 11-mer (Cy5-AUCCUZAAAAA-3′) oligonucleotide with rps14 C80 sequences. Although the native ccmFC (AUGUUCCCACA)-editing site has nucleotide differences compared with rps14 C80, none interfere with predicted PPR interactions. Although a small increase in editing was observed in the presence of the 11-mer, no large effect on editing was observed after addition of any of the zebularine incorporating oligonucleotides (Fig. 6).

Discussion

A single, recombinant DYW-containing PPR protein sufficiently catalyzes C-to-U editing conversion. Mutations in the active site abrogate activity and lead to aggregation. It is likely that nearly all organelle C-to-U editing in organisms that contain the DYW-deaminase domain require an active DYW domain as the sole enzymatic component.

In this study, no strong evidence for stable dimers of PPR65 was discovered. Several studies based on yeast two-hybrid analysis and a X-ray crystal structure have suggested that PPR proteins have weak interactions with other PPR proteins (4). Observations from genetic complementation studies are also best explained by the formation of active homo/heterodimers by PPR proteins (9, 19, 20, 30). There are examples where DYW proteins are necessary for RNA editing, but do not act as primary specificity factors such as DYW1 in chloroplast ndhD editing (21) and MEF8/MEF8S proteins that are critical for several mitochondrial editing sites (30). Although the formation of transient dimers or other oligomers cannot be excluded after the addition of RNA substrate, PPR65 protein fractions that were distinctly monomeric demonstrated greater activity than oligomeric fractions.

The DYW-deaminase domain has been projected to bind either a single zinc ion (8) or two zinc ions (9). Unfortunately, both prior studies had focused on recombinant proteins without demonstration of activity. Active PPR65 fractions bind the quantum of zinc expected for a two-zinc ion per protein stoichiometry. In this study, a single amino acid change at a single zinc coordinating residue reduced zinc ion binding to a single zinc ion per polypeptide. Cysteine residues often coordinate zinc, and in addition to the canonical residues that form the projected catalytic site, there are an additional two cysteines at the C terminus that are highly conserved (9). These residues have also been shown to be necessary for RNA editing (10). Future research will be required to determine the actual role of the second zinc ion as part of the reaction mechanism.

Addition of zinc acetate and zinc chelators reduced the activity of PPR65 on PpccmFC substrates. PPR65 was sensitive to the relatively low concentration of 50 μm zinc acetate (Fig. 3). Similarly, 100 μm zinc chloride was strongly inhibitory to Trypanosoma brucei tRNA editing deaminase (ADAT) (31). PPR65 aggregates demonstrated more zinc than expected suggesting protein aggregation might be linked to excess zinc binding and may be promoted by high zinc concentrations. Editing was also reduced by EDTA addition to ADAT reactions (31), and inhibition by EDTA and the more specific zinc chelator 1,10-o-phenanthroline is consistent with observations for organelle C-to-U RNA editing on psbE C214 substrates using chloroplast extracts in vitro (26). Our observations are consistent with PPR65 being a zinc metaloenzyme.

Shortly after editing assays had been developed using chloroplast and mitochondrial extracts, it was discovered that RNA-editing activity could be enhanced by the addition of nucleotide triphosphates (25–27, 32). Because hydrolytic deamination of cytidine is favorable without ATP coupling and several nucleotide triphosphates could stimulate editing activity, the nucleotide triphosphate requirement was hypothesized to be due to RNA helicase activity (25). The discovery that reduced expression of the DEAD box helicase ISE2 led to RNA-editing defects lends support for its inclusion in the editosome (33). ISE2 was also discovered to be present in chloroplast fractions enriched for RIP9 and other RNA-editing factors (24). Because PPR65 was solely sufficient for RNA editing, it was not anticipated that ATP would stimulate editing assays although stimulation was observed. Stimulation of editing was also observed using nonhydrolyzable ATP and ADP analogs AMP-PCP and AMP-CP. Therefore, it is unlikely that hydrolysis between either the γ-β or α-β anhydride bonds or magnesium sequestration promotes RNA editing, suggesting the mode of action might be through allosteric binding. A functional model where RNA editing can be allosterically regulated by the energy charge of organelles would be consistent with these observations.

The DYW-deaminase appears to be part of a family of amino hydrolases and was projected to use the same mechanism that has been well-established for E. coli cytidine deaminase (3), ADAR (29), and APOBEC3G (28). It is unclear why modified nucleosides tetrahydrouridine and zebularine were shown not to directly affect RNA-editing activity using PPR65 on PpccmFC substrates or chloroplast extract-catalyzed reactions using appropriate substrates. Sequestration of editing factors on Zmrps14 C80 zebularine oligonucleotides was expected to reduce editing of the Zmrps14 C80 substrate because similar competitive effects were observed for similar molar ratios of psbE substrates and competitors in vitro (34). Failure to compete suggests an issue with PPR/DYW recognition of the zebularine-incorporated RNA oligonucleotides.

A bioinformatics investigation has recently linked variants of the DYW-deaminase domain with both deamination of cytosine as well as amination of uracil in mRNA (35). Zinc-dependent nucleotide deaminases catalyze an irreversible reaction unlikely to be simply reversed without extensive modification. If a DYW variant can seemingly catalyze an amination reaction with so few changes from a deaminase variant then it is possible the mechanism differs from canonical zinc-dependent nucleotide deaminases. Given the unique zinc stoichiometry of the DYW-deaminase, proximity of the likely second zinc-chelating residues to the active site, and the failure of putative inhibitors to inhibit editing, it is likely that the catalytic pocket of DYW-deaminases differs from known nucleotide deaminases.

Now that this study has provided the initial evidence that active PPR editing factors can be purified and editing can be assayed under defined conditions in vitro, future investigations can continue in confidence to engineer new biotechnology tools from PPR65 or other PPR proteins. In contrast to the E. coli system previously described (12), the in vitro assay will allow more rapid identification of sequence specificity of the native and modified PPR65 proteins. Because the assay environment can be controlled, the applicability of PPR editing to other cellular environments can be examined quickly. Complications to applying the PPR65 enzymes to new sites might be rapidly addressed using rational design and/or in vitro selection techniques.

Experimental procedures

Expression of PPR proteins

Vectors containing WT PPR65 (pETG41K::PPR65) and mutant PPR65 constructs (pETG41K::PPR65E657A and pETG41K::PPR65C683A) were obtained from the laboratory of Volker Knoop and Mareike Schallenberg-Rüdinger, the University of Bonn (12). Plasmids were then transferred to E. coli strain Rosetta2 DE3 pLYS from Novagen. Overnight cultures where used to inoculate 6 liters of LB distributed in 1-liter portions in 2-liter baffled flasks at 37 °C to the OD600 of 0.05. Six 1-liter cultures were grown at 37 °C to an OD600 of 0.3 and allowed to air cool in a 16 °C shaker for 30 min. Zinc acetate was added to each culture to a final concentration of 0.4 mm. Isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside was then added to a final concentration of 1 mm to induce protein expression. Induction was allowed to continue for 6 h and cultures were centrifuged at 5000 × g for 15 min and LB media poured off. Bottles containing cell pellets were inverted and frozen at −80 °C.

Purification of active PPR65

All steps were carried out at 4 °C and completed within 48 h. Cell pellets were suspended in ice-cold lysis buffer (25 mm Tris, pH 7.2, at 22 °C, 250 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 10 mm imidazole) and sonicated 6× 20-s pulses with 1-min breaks in an ice-water bath. Lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min and cleared lysates were decanted into an ice-cold beaker. Cleared lysates were passed over a 10-ml His Pure IMAC resin column (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA) equilibrated with lysis buffer. The IMAC resin was washed using 200 ml of IMAC wash buffer (25 mm Tris, pH 7.2, 22 °C, 250 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 20 mm imidazole). The protein was eluted using a single 30-ml elution step using 25 mm Tris, pH 7.2, 22 °C, 250 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 250 mm imidazole. The elution fraction was passed over 10 ml of amylose resin (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) equilibrated in editing buffer (30 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.7, 3 mm magnesium acetate, 45 mm potassium acetate, 30 mm ammonium acetate, 10% glycerol). The amylose resin was then washed using 200 ml of editing buffer and (∼11 mg) of protein eluted using 30 ml of editing buffer with 10 mm maltose added. The 30-ml fraction was concentrated using an Amicon® Ultra-15 Centrifugal Filter Unit 50,000 NMWL (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) until the final volume reached ∼300 μl. The concentrated protein fraction was centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 10 min and the supernatant injected into a 250-μl load loop leading into a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare BioSciences) using a single isocratic step with editing buffer and a NGC Chromatography System (Bio-Rad). Fractions of 0.5 ml were collected, screened for protein using SDS-PAGE, fractions were pooled, and 54-μl aliquots were flash frozen with liquid nitrogen. Aliquots were stored at −80 °C, with activity retained after 4 months of storage.

Synthesis of RNA-editing substrates

PCR amplicons were first synthesized using the pETG41K::PPR65 plasmid as template from the laboratory of Volker Knoop and Mareike Schallenberg-Rüdinger, the University of Bonn, and primers ccmFC_SK_For: CGCTCTAGAACTAGTGGATCCTTGTGGGGATTTTTGGTGA, ccmFC_KS_RevC: TCGAGGTCGACGGTATCTGTGGGAACATCTCTACTTA, and ccmFC_KS_RevT: TCGAGGTCGACGGTATCTGTGGAAACATCTCTACTTA. Primers ccmFC_SK_For and ccmFC_KS_RevC were used to create an editable template called PpccmFC, whereas ccmFC_SK_For and ccmFC_KS_RevT enabled the creation of the “edited” template used as a poisoned primer extension control. A second PCR using primers: T7SK, TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGCGCTCTAGAACTAGTGGATC and KS, TCGAGGTCGACGGTATC produced amplicons with a 5′ T7 sequence. Transcription reactions in vitro using the T7 Transcript Aid High Yield Kit (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA) synthesized the RNAs used in this study. RNA was diluted to 100 fmol/μl for PPR65 reactions. Substrates for maize chloroplast extract reactions include ZmrpoC2 C2774 and Zmrps14 C80 and were constructed as previously published (24). RNA substrates included a SK sequence on the 5′-end, followed by 100 nucleotides upstream and 5 nucleotides downstream of the sequence around the editing site, and a KS primer sequence on the 3′-end. Editing substrates for ccmFC only had 33 nucleotides of upstream native sequence.

RNA-editing activity assay

Optimized reaction mixtures for PPR65 (12.5 μl) contained 30 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.7, 3 mm magnesium acetate, 45 mm potassium acetate, 30 mm ammonium acetate, 2 mm ATP, 5 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), 1% polyethylene glycol 6000, 5% glycerol, 5 units of RNase inhibitor (Fermentas, Hanover, MD), 1× proteinase inhibitor mixture (Complete EDTA-free; Roche Applied Science), 100 fmol of mRNA substrate, and 6.25 μg of purified PPR65 protein. Reactions involving maize chloroplast extracts were setup identical to published reports (24). Differences in chloroplast extract reactions compared with the PPR65 assay include 30 units of RNase inhibitor, 1 fmol of RNA substrate, 1 mm ATP, and 62.5 μg of chloroplast protein. Chloroplast extraction and preparation of maize chloroplast protein extracts were performed as previously described (24). Reverse transcription reactions used Maxima Reverse Transcriptase (ThermoFisher) and a KS reverse primer. A PCR step used Dream Taq (ThermoFisher) and primers T7-SK and KS amplified for 22 cycles for PPR65 and 25 cycles for maize chloroplast extract reactions. PCR products were purified using the Zymoclean Gel DNA Recovery Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA). Antarctic phosphatase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) was used to remove any remaining nucleotide triphosphates.

Quantitative poisoned primer extension (PPE) analysis

PPE reactions used Vent Taq (New England Biolabs), acyclonucleotide triphosphates (New England Biolabs), and 1 pmol of 5′-tetrachlorofluorescein–labeled KS primer (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc., Coralville, IA). Extension products were separated using a 6 m urea, 20% polyacrylamide gel of 16.5 × 28 cm at constant power of 25 watts. Images were produced using an Azure c400 imager (Azure Biosystems, Inc., Dublin, CA) and the Cy3 settings at 1- and 5-min exposure times. The intensity of each band was measured using ImageJ (37). Percent conversion was calculated using the intensity of the band resulting from the edited band/sum of extended bands ×100. Multiplication of the total mol of RNA by % conversion yields the theoretical moles of uracil produced.

Nucleotides, nucleosides, and modified ribonucleotide oligos

ATPγS, AMP-PCP, AMP-CP, ATP, ADP, CMP, cytidine, zebularine, tetrahydrouridine were all obtained from Sigma Aldrich. Ribonucleotides containing incorporated zebularine were obtained from Bioneer (Daedeok-gu, Daejeon Republic of Korea). Trimers had the sequence 5′-U-(zeb)-A-3′. Zebularine ribonucleotides for rpl20 C308 and rps14 C80 had a 5′-Cy5 fluorophore followed by the sequences 5′-GCUUGCACAAGUAGCUGUAU(Zeb)AAAUU-3′, and 5′-UCAUUUGAUUCGUCGAUCCU(Zeb)AAAAA-3′, respectively.

MALS analysis

MALS analysis was carried out at the NanoBiophysics Core Facility at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA. High molecular weight fractions initially purified as described above from the SuperDex S200 column were thawed and introduced to a Shodex PROTEIN KW-804 column (Showa Denko America, Inc., New York) with a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min on an Agilent 1200 HPLC connected to a Wyatt DAWN HELEOS MALS unit. Peaks were analyzed using ASTRA6.1 chromatography software.

Zinc metal analysis

Fractions purified as described above were thawed and subjected to ICP-MS at the ICP-MS Analysis Core Facility, University at California Los Angeles. The total amount of Zn content in the proteins was determined by ICP-MS (NexION 2000, PerkinElmer Life Sciences) analysis. The 100 μl of suspension of each sample was transferred to clean tubes (SC475, Environmental Express) for acid digestion. Digestion was carried out with 3 ml of a concentrated HNO3 (65–70%, Trace Metal Grade, Fisher Scientific) with a supplement of H2O2 (30%, Certified ACS, Fisher Scientific) overnight at 95 °C in a HotBlock (SC100, Environmental Express). Once the sample was cooled to room temperature, it was subsequently diluted to make a final volume of 1 ml by adding 2% HNO3. A calibration curve was established using a standard Zn solution (AccuStandard, 10 μg/ml in 2–5% HNO3). Each sample and standard was analyzed in triplicate with background correction. Absorbance at 280 nm was measured 9 times for each protein fraction using a nanodrop lite spectrometer (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA). The extinction coefficient of 147,600 m−1 cm−1 for PPR65 was determined by ProtParam using the reduced cysteine model (36). Zinc chelators 1,10-o-phenanthroline and EDTA were obtained from Arcos Organics (Waltham, MA) and ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA), respectively.

Author contributions

M. L. H. conceptualization; M. L. H. resources; M. L. H. and P. I. S. data curation; M. L. H. and P. I. S. formal analysis; M. L. H. supervision; M. L. H. funding acquisition; M. L. H. validation; M. L. H. investigation; M. L. H. visualization; M. L. H. methodology; M. L. H. writing-original draft; M. L. H. project administration; M. L. H. writing-review and editing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Volker Knoop, Dr. Mareike Schallenberg-Rüdinger, and Bastian Oldenkott for the PPR65 constructs, helpful discussions, and E-mail correspondences. We acknowledge the use of ICP-MS Core Facility within the University of California Center for Environmental Implications of Nanotechnology in CNSI at UCLA. We thank Alena N. Kiszter for technical help collecting data on tetrahydrouridine addition to maize chloroplast-editing assays in vitro. We also thank Dr. Maureen Hanson for critical reading of the manuscript. Last, we thank Alfredo Jimenez-Salinas for technical help expressing recombinant PPR65 CXXC>CXXA proteins.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health SCORE SC2 Grant SC2 GM122718 (to M. L. H.) and National Institutes of Health NIGMS Grant R25 GM61331 to the RISE MS-to-Ph.D. program (to P. I. S.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains Figs. S1–S5.

- ADAR

- adenosine deaminase acting on RNA

- PPR

- pentatricopeptide repeat

- PHEN

- 1–10-o-phenanthroline

- ATPγS

- adenosine 5′-O-(3-thiotriphosphate)

- AMP-PCP

- β,γ-methyleneadenosine 5′-triphosphate

- AMP-CP

- α,β-methyleneadenosine 5′-diphosphate

- THU

- tetrahydrouridine

- Cy5

- indodicarbocyanine

- ZEB

- zebuarine

- AZA

- 5-azacytdine

- PPE

- poisoned primer extension

- ESI

- electrospray ionization

- ICP-OES

- inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry

- APOBEC3G

- apolipoprotein B mRNA-editing enzyme catalytic subunit 3G

- MBP

- maltose-binding protein

- MALS

- multiangle light scattering.

References

- 1. Krishnan A., Iyer L. M., Holland S. J., Boehm T., and Aravind L. (2018) Diversification of AID/APOBEC-like deaminases in metazoa: multiplicity of clades and widespread roles in immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E3201–E3210 10.1073/pnas.1720897115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rees H. A., and Liu D. R. (2018) Base editing: precision chemistry on the genome and transcriptome of living cells. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19, 770–788 10.1038/s41576-018-0059-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carlow D., and Wolfenden R. (1998) Substrate connectivity effects in the transition state for cytidine deaminase. Biochemistry 37, 11873–11878 10.1021/bi980959n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sun T., Bentolila S., and Hanson M. R. (2016) The unexpected diversity of plant organelle RNA editosomes. Trends Plant Sci. 21, 962–973 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lurin C., Andrés C., Aubourg S., Bellaoui M., Bitton F., Bruyère C., Caboche M., Debast C., Gualberto J., Hoffmann B., Lecharny A., Le Ret M., Martin-Magniette M. L., Mireau H., Peeters N., et al. (2004) Genome-wide analysis of Arabidopsis pentatricopeptide repeat proteins reveals their essential role in organelle biogenesis. Plant Cell 16, 2089–2103 10.1105/tpc.104.022236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Salone V., Rüdinger M., Polsakiewicz M., Hoffmann B., Groth-Malonek M., Szurek B., Small I., Knoop V., and Lurin C. (2007) A hypothesis on the identification of the editing enzyme in plant organelles. FEBS Lett. 581, 4132–4138 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.07.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schallenberg-Rüdinger M., Lenz H., Polsakiewicz M., Gott J. M., and Knoop V. (2013) A survey of PPR proteins identifies DYW domains like those of land plant RNA editing factors in diverse eukaryotes. Rna Biol. 10, 1549–1556 10.4161/rna.25755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boussardon C., Avon A., Kindgren P., Bond C. S., Challenor M., Lurin C., and Small I. (2014) The cytidine deaminase signature HxE(x)n CxxC of DYW1 binds zinc and is necessary for RNA editing of ndhD-1. New Phytol. 203, 1090–1095 10.1111/nph.12928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hayes M. L., Giang K., Berhane B., and Mulligan R. M. (2013) Identification of two pentatricopeptide repeat genes required for RNA editing and zinc binding by C-terminal cytidine deaminase-like domains. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 36519–36529 10.1074/jbc.M113.485755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wagoner J. A., Sun T., Lin L., and Hanson M. R. (2015) Cytidine deaminase motifs within the DYW domain of two pentatricopeptide repeat-containing proteins are required for site-specific chloroplast RNA editing. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 2957–2968 10.1074/jbc.M114.622084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hayes M. L., Dang K. N., Diaz M. F., and Mulligan R. M. (2015) A conserved glutamate residue in the C-terminal deaminase domain of pentatricopeptide repeat proteins is required for RNA editing activity. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 10136–10142 10.1074/jbc.M114.631630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oldenkott B., Yang Y., Lesch E., Knoop V., and Schallenberg-Rüdinger M. (2019) Plant-type pentatricopeptide repeat proteins with a DYW domain drive C-to-U RNA editing in Escherichia coli. Commun. Biol. 2, 85 10.1038/s42003-019-0328-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barkan A., Rojas M., Fujii S., Yap A., Chong Y. S., Bond C. S., and Small I. (2012) A combinatorial amino acid code for RNA recognition by pentatricopeptide repeat proteins. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002910 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shen C., Zhang D., Guan Z., Liu Y., Yang Z., Yang Y., Wang X., Wang Q., Zhang Q., Fan S., Zou T., and Yin P. (2016) Structural basis for specific single-stranded RNA recognition by designer pentatricopeptide repeat proteins. Nat. Commun. 7, 11285 10.1038/ncomms11285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Robbins J. C., Heller W. P., and Hanson M. R. (2009) A comparative genomics approach identifies a PPR-DYW protein that is essential for C-to-U editing of the Arabidopsis chloroplast accD transcript. RNA 15, 1142–1153 10.1261/rna.1533909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hammani K., Okuda K., Tanz S. K., Chateigner-Boutin A. L., Shikanai T., and Small I. (2009) A study of new Arabidopsis chloroplast RNA editing mutants reveals general features of editing factors and their target sites. Plant Cell 21, 3686–3699 10.1105/tpc.109.071472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Okuda K., Myouga F., Motohashi R., Shinozaki K., and Shikanai T. (2007) Conserved domain structure of pentatricopeptide repeat proteins involved in chloroplast RNA editing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 8178–8183 10.1073/pnas.0700865104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kotera E., Tasaka M., and Shikanai T. (2005) A pentatricopeptide repeat protein is essential for RNA editing in chloroplasts. Nature 433, 326–330 10.1038/nature03229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Okuda K., Chateigner-Boutin A. L., Nakamura T., Delannoy E., Sugita M., Myouga F., Motohashi R., Shinozaki K., Small I., and Shikana T. (2009) Pentatricopeptide repeat proteins with the DYW motif have distinct molecular functions in RNA editing and RNA cleavage in Arabidopsis chloroplasts. Plant Cell 21, 146–156 10.1105/tpc.108.064667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Okuda K., Hammani K., Tanz S. K., Peng L., Fukao Y., Myouga F., Motohashi R., Shinozaki K., Small I., and Shikanai T. (2010) The pentatricopeptide repeat protein OTP82 is required for RNA editing of plastid ndhB and ndhG transcripts. Plant J. 61, 339–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boussardon C., Salone V., Avon A., Berthomé R., Hammani K., Okuda K., Shikanai T., Small I., and Lurin C. (2012) Two interacting proteins are necessary for the editing of the NdhD-1 site in Arabidopsis plastids. Plant Cell 24, 3684–3694 10.1105/tpc.112.099507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Iyer L. M., Zhang D., Rogozin I. B., and Aravind L. (2011) Evolution of the deaminase fold and multiple origins of eukaryotic editing and mutagenic nucleic acid deaminases from bacterial toxin systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 9473–9497 10.1093/nar/gkr691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pham P., Afif S. A., Shimoda M., Maeda K., Sakaguchi N., Pedersen L. C., and Goodman M. F. (2016) Structural analysis of the activation-induced deoxycytidine deaminase required in immunoglobulin diversification. DNA Repair (Amst) 43, 48–56 10.1016/j.dnarep.2016.05.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sandoval R., Boyd R. D., Kiszter A. N., Mirzakhanyan Y., Santibańez P., Gershon P. D., and Hayes M. L. (2019) Stable native RIP9 complexes associate with C-to-U RNA editing activity, PPRs, RIPs, OZ1, ORRM1 and ISE2. Plant J. 99, 1116–1126 10.1111/tpj.14384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Takenaka M., and Brennicke A. (2003) In vitro RNA editing in pea mitochondria requires NTP or dNTP, suggesting involvement of an RNA helicase. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 47526–47533 10.1074/jbc.M305341200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hegeman C. E., Hayes M. L., and Hanson M. R. (2005) Substrate and cofactor requirements for RNA editing of chloroplast transcripts in Arabidopsis in vitro. Plant J. 42, 124–132 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02360.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nakajima Y., and Mulligan R. M. (2005) Nucleotide specificity of the RNA editing reaction in pea chloroplasts. J. Plant Physiol. 162, 1347–1354 10.1016/j.jplph.2005.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kvach M. V., Barzak F. M., Harjes S., Schares H. A. M., Jameson G. B., Ayoub A. M., Moorthy R., Aihara H., Harris R. S., Filichev V. V., Harki D. A., and Harjes E. (2019) Inhibiting APOBEC3 activity with single-stranded DNA containing 2′-deoxyzebularine analogues. Biochemistry 58, 391–400 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Haudenschild B. L., Maydanovych O., Véliz E. A., Macbeth M. R., Bass B. L., and Beal P. A. (2004) A transition state analogue for an RNA-editing reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 11213–11219 10.1021/ja0472073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Diaz M. F., Bentolila S., Hayes M. L., Hanson M. R., and Mulligan R. M. (2017) A protein with an unusually short PPR domain, MEF8, affects editing at over 60 Arabidopsis mitochondrial C targets of RNA editing. Plant J. 92, 638–649 10.1111/tpj.13709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Spears J. L., Rubio M. A. T., Gaston K. W., Wywial E., Strikoudis A., Bujnicki J. M., Papavasiliou F. N., and Alfonzo J. D. (2011) A single zinc ion is sufficient for an active Trypanosoma brucei tRNA editing deaminase. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 20366–20374 10.1074/jbc.M111.243568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hirose T., and Sugiura M. (2001) Involvement of a site-specific trans-acting factor and a common RNA-binding protein in the editing of chloroplast mRNAs: development of a chloroplast in vitro RNA editing system. EMBO J. 20, 1144–1152 10.1093/emboj/20.5.1144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bobik K., McCray T. N., Ernest B., Fernandez J. C., Howell K. A., Lane T., Staton M., and Burch-Smith T. M. (2017) The chloroplast RNA helicase ISE2 is required for multiple chloroplast RNA processing steps in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 91, 114–131 10.1111/tpj.13550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hayes M. L., and Hanson M. R. (2007) Identification of a sequence motif critical for editing of a tobacco chloroplast transcript. RNA 13, 281–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gerke P., Szovenyi P., Neubauer A., Lenz H., Gutmann B., McDowell R., Small I., Schallenberg-Rüdinger M., and Knoop V. (2019) Towards a plant model for enigmatic U-to-C RNA editing: the organelle genomes, transcriptomes, editomes and candidate RNA editing factors in the hornwort Anthoceros agrestis. New Phytol. 225, 1974–1992 10.1111/nph.16297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wilkins M. R., Gasteiger E., Bairoch A., Sanchez J. C., Williams K. L., Appel R. D., and Hochstrasser D. F. (1999) Protein identification and analysis tools in the ExPASy server. Methods Mol. Biol. 112, 531–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schneider C. A., Rasband W. S., and Eliceiri K. W. (2012) NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675 10.1038/nmeth.2089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.