Abstract

Objectives

Over the last 15 years, the prevalence of HIV in Haiti has stabilised to around 2.0%. However, key populations remain at higher risk of contracting HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). The prevalence of HIV is 12.9% among men having sex with men (MSM). There is limited information about the prevalence of other STI in the Haitian population in general and even less among key populations. We assessed the burden of Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG) and risk factors for infections among MSM in Haiti.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted. MSM were recruited from seven health facilities in Port-au-Prince. All samples were tested by nucleic acid amplification test, using GeneXpert. A survey was administered to the participants to collect socio-demographic, clinical and risk behaviour data.

Results

A total of 216 MSM were recruited in the study. The prevalence rates of CT and NG were 11.1% and 16.2%, respectively. CT NG co-infections were found in 10/216 (4.6%) of the participants. There were 39 MSM with rectal STI compared with 17 with genital infections. Participants between 18–24 and 30–34 years old were significantly more likely to be infected with NG than those aged 35 years or older (OR: 22.96, 95% CI: 2.79 to 188.5; OR: 15.1, 95% CI: 1.68 to 135.4, respectively). Participants who never attended school or had some primary education were significantly more likely to be infected with NG than those with secondary education or higher (OR: 3.38, 95% CI: 1.26 to 9.07). People tested negative for HIV were significantly more likely to be infected with CT than people living with HIV/AIDS (OR: 3.91, 95% CI: 1.37 to 11.2).

Conclusions

Periodic risk assessment and testing for STI should be offered in Haiti as part of a comprehensive strategy to improve the sexual health of key populations.

Keywords: HIV & AIDS, public health, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of the study.

This is the first study assessing the prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and Neisseria Gonorrhoeae in key populations in Haiti.

The lower prevalence of CT among people living with HIV underlined the importance to presumptively test and treat for sexually transmitted infection (STI), regardless of HIV status.

Periodic risk assessment and testing, with algorithms tailored for MSM should be part of the upcoming guidelines on STI management in Haiti.

Fear of discrimination and stigmatisation might be a limited factor to reliable answers to the questionnaire beside our best efforts to provide a judgement-free environment for our study.

Introduction

The prevalence of the HIV in Haiti has stabilised to around 2% during the past 15 years among the population aged between 15 and 49 years old.1 Despite this overall stability, in order to reach epidemic control, prevention and control measures must be directed to hot spots of HIV transmission. Heterosexual contact remained the predominant mode of HIV transmission in Haiti,2 but the initial introduction and spread of the virus were associated with homosexual intercourse3 and key populations are disproportionately impacted by the epidemic.4 In Haiti, homosexuality is highly stigmatised and openly gay men are a minority of the men having sex with men (MSM) populations, hence the difficulty to reliably estimate the population and the burden of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in these communities.5 6 In addition, HIV services for key populations in Haiti remain largely inadequate.

The Haitian Ministry of Health and Population (French acronym MSPP) reported a HIV prevalence of 12.9% among MSM in 2014.4 7 The recent results from the 2016 Priorities for Local AIDS Control Efforts study showed lower estimates of HIV prevalence of 2.2% (95% CI: 0.9% to 5.3%) among MSM.8 This discrepancy in estimates of HIV burden among MSM in Haiti in two different reports, 2 years apart, is a result of the difficulty to reach the MSM populations. While the national HIV/AIDS surveillance programme reports periodic HIV and syphilis prevalence survey in the general population and in high-risk groups such as MSM, other STIs with public health importance in Haiti such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG) and Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) are less documented, particularly in key populations.

Epidemiological evidences suggest that both CT and NG can potentiate sexual transmission of HIV infection.9–12 These STIs may cause genital ulcers or mucosal inflammation, increasing the risk of HIV transmission.13–15 Treating STI is believed to be a valid strategy for decreasing HIV transmission.10 16 Diagnostics and treatment of STI in Haiti are mainly based on syndromic management of the four main sets of symptoms, which might each be caused by multiple sexually transmitted pathogens: genital ulcers, urethral discharge, vaginal discharge and pelvic inflammatory disease.17 In 2011, the WHO recommended that asymptomatic MSM reporting unprotected receptive anal intercourse and either multiple sex partners or a sex partner with an STI in the past 6 months should be presumptively treated for rectal NG and CT infections.16 WHO also recommends offering periodic testing for asymptomatic urethral and rectal NG and CT infections using nucleic acid amplification techniques for MSM.16

The latest guidelines on STIs care and treatment published by MSPP dated from 2007; a revision of these guidelines is overdue in light of new WHO recommendations. Such revision would require current data on the prevalence of STIs on high-risk populations in Haiti such as MSM. Our study aimed to determine the prevalence of CT and NG infections among MSM in Port-au-Prince and the metropolitan area, to describe associations between these infections and behavioural risk factors and to provide data for an evidence-based update of the STI guidelines in Haiti.

Methods

Study design and setting

The cross-sectional study was conducted from September 2018 to July 2019 at seven key populations friendly health facilities in the metropolitan area of Port-au-Prince. All MSM attending the selected health facilities were screened for enrolment irrespective of their reason for attendance. The selection of participants was a non-random convenience sampling approach with deliberate oversampling of HIV-infected participants since the study was part of a larger attempt to characterise the HIV transmission network in key populations in Haiti.

Study participants

Eligibility criteria included being aged 18 years or older, self-identified as MSM, living in the metropolitan area of Port-au-Prince, antiretroviral naïve or under treatment for less than 12 months if living with HIV/AIDS and ability to understand the study and provide informed consent to participate in the study.

Data collection

Pre-test and post-test counselling for HIV and STI testing was performed. Paper-based behavioural surveys were conducted following informed consent by a nurse counsellor to eligible participants and took approximately 20–30 min to complete. Survey questions included demographics, alcohol use, sexual risk and prevention behaviours and HIV testing. HIV testing was offered to people with unknown HIV status.

Laboratory methods

MSM participants provided a first-void urine specimen and the nurse or the doctor collected anal swabs for NG and CT for molecular diagnostics. All samples were transported to the Haitian National Public Health Laboratory (French acronym LNSP) for testing by nucleic acid amplification test, using Xpert CT/NG assay (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, California).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated for demographic and behavioural parameters. The prevalence of gonorrhoea and chlamydia was estimated. Unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression were used to describe the association between behavioural and demographic factors with the odds of having gonorrhoea and chlamydia. Only variables tested in the univariate analysis with p<0.1 were included in the multivariate model. Values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant. SPSS V. 26.0 was used for analyses.

Data were fully anonymised before they were extracted for analysis. All participants with positive results were treated and their partners invited to the health facilities for free treatment. All participants signed an informed consent.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the design and the conduct of the study. Patients infected with CT and/or NG were encouraged to invite their sexual partners for treatment and enrolment to the study.

Results

Demographic, clinical and behavioral characteristics

A total of 216 participants were recruited in the study. The baseline characteristics of the participants by population group and risk behaviours are summarised in table 1. MSM had a median age of 27 years old, IQR 22–35. The majority of the participants were single (74.5%) and more than 80% of MSM reported having a secondary education or higher. The consistent use of condom and lubricant during intercourse was very low (28.5% and 19.1%, respectively) and 70.8% of MSM participating in the study were HIV positive.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics, sexual behaviour and STI risks in men having sex with men (MSM)

| MSM | |||

| N | N % | ||

| Age group | 18–24 | 86 | 39.8% |

| 25–29 | 45 | 20.8% | |

| 30–34 | 30 | 13.9% | |

| 35 and older | 55 | 25.5% | |

| Marital status | Single | 158 | 74.5% |

| Other (married, living with partner) | 54 | 25.5% | |

| Education | Some primary education | 43 | 19.9% |

| Secondary education or higher | 173 | 80.1% | |

| Number of sex partners in the past 6 months | ≤5 | 175 | 81.0% |

| >5 | 41 | 19.0% | |

| Alcohol | No | 105 | 49.8% |

| Yes | 106 | 50.2% | |

| Consistent lubricant use in the past 6 months | No | 165 | 80.9% |

| Yes | 39 | 19.1% | |

| Consistent condom use in the past 6 months | No | 153 | 71.5% |

| Yes | 61 | 28.5% | |

| HIV status | Positive | 153 | 70.8% |

| Negative | 63 | 29.2% | |

| CT | Negative | 192 | 88.9% |

| Positive | 24 | 11.1% | |

| NG | Negative | 181 | 83.8% |

| Positive | 35 | 16.2% | |

| CT and NG | Negative | 206 | 95.4% |

| Positive | 10 | 4.6% | |

CT, Chlamydia trachomatis; NG, Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

Prevalence of CT and NG

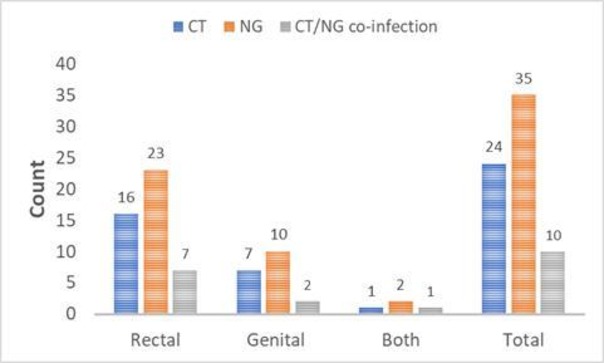

Overall, 22.7% (49/216) participants screened positive for either NG or CT. The prevalence of CT among MSM was 11.1% (24/216) and 7 of these men had genital CT infections, 16 had rectal infections and 1 at the two anatomical sites. A total of 35 MSM (16.2%) were infected with NG and 10 of these men had genital NG infections, 23 had rectal infections and 2 at the two anatomical sites (table 1). CT/NG co-infections were present in 10 MSM (4.6%) and 70% of these infections were rectal (figure 1). There was no statistical difference in CT and NG infections when comparing the two anatomical sites, but it is worth noting that anorectal STIs were two times higher than genital infections (39 rectal vs 17 genitals; figure 1).

Figure 1.

Gonorrhoea and chlamydia by site of infection. CT, Chlamydia trachomatis; NG, Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

Risk factors for CT and NG infections

Among MSM, CT and NG infections were not associated with marital status, alcohol consumption, number of sex partners in the past 6 months and prevention measures such as consistent use of condom and lubricant (table 2). In the multivariable analyses, participants between 18–24 and 30–34 years old were significantly more likely to be infected with NG than those aged 35 years or older (OR: 22.96, 95% CI: 2.79 to 188.5; OR:15.1, 95% CI: 1.68 to 135.4, respectively). Participants who never attended school or had some primary education were significantly more likely to be infected with NG than those with secondary or higher education (OR: 3.38, 95% CI: 1.26 to 9.07). People tested negative for HIV were significantly more likely to be infected with CT than people living with HIV/AIDS (OR: 3.91, 95% CI: 1.37 to 11.2). Participants infected with NG or CT have significantly higher risk of co-infections [OR: 5.63, 95% CI: 1.93 to 16.38 (risk of co-infection with CT); OR: 3.73, 95% CI: 1.38 to 10.11 (risk of co-infection with NG)].

Table 2.

Factors associated with CT and NG infections using univariable and multivariable logistic regression models

| Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||||||||

| Chlamydia | Gonorrhoea | Chlamydia | Gonorrhoea | ||||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | aOR | 95% CI | aOR | 95% CI | ||

| Age | 18–24 | 12.34 | 1.59 to 96.0 | 19.71 | 2.58 to 150.8 | 22.96 | 2.79 to 188.5 | ||

| 25–29 | 8.31 | 0.96 to 71.8 | 6.75 | 0.76 to 60.05 | 8.1 | 0.86 to 76.5 | |||

| 30–34 | 1.86 | 0.1 to 30.88 | 13.5 | 1.5 to 118.3 | 15.1 | 1.68 to 135.4 | |||

| >35 | – | – | – | ||||||

| Education | Never attended/some primary school | 0.54 | 0.15 to 1.91 | 1.79 | 0.79 to 4.09 | 3.38 | 1.26 to 9.07 | ||

| Secondary school or higher | – | – | – | ||||||

| Marital status | Single | 0.76 | 0.29 to 1.95 | 0.89 | 0.39 to 2.07 | ||||

| Other (married, living with partner) | – | – | |||||||

| Number of sex partners in the past 6 months | ≤5 | 1.73 | 0.49 to 6.09 | 0.75 | 0.31 to 1.80 | ||||

| >5 | – | – | |||||||

| Alcohol consumption | No | 1.11 | 0.47 to 2.65 | 1.79 | 0.84 to 3.79 | ||||

| Yes | – | – | |||||||

| Consistent lubricant use in the past 6 months | No | 1.75 | 0.49 to 6.19 | 1.39 | 0.5 to 3.87 | ||||

| Yes | – | – | |||||||

| Consistent condom use in the past 6 months | No | 1.59 | 0.56 to 4.46 | 1.18 | 0.52 to 2.70 | ||||

| Yes | – | – | |||||||

| HIV status | Positive | – | – | ||||||

| Negative | 2.08 | 1.34 to 3.22 | 1.22 | 0.73 to 2.03 | 3.91 | 1.37 to 11.2 | |||

| Gonorrhoea | Positive | 4.77 | 1.91 to 11.9 | 5.63 | 1.93 to 16.38 | ||||

| Negative | |||||||||

| Chlamydia | Positive | 4.77 | 1.91 to 11.9 | 3.73 | 1.38 to 10.11 | ||||

| Negative | – | – | |||||||

Those in bold type indicate significance of <0.05.

aOr, adjusted OR; CT, Chlamydia trachomatis; NG, Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

Discussion

Here we reported the first study looking at the prevalence of CT and NG in MSM in Haiti. This study documented a high prevalence of NG and CT infections among MSM in the metropolitan area of Port-au-Prince. Prior studies looking at the prevalence of STI in the general populations have focused mainly on women attending antenatal services in Haiti: a relatively high prevalence of CT and NG was reported in rural Artibonite in 1996 (2.3% had gonorrhoea (11/475) and 10% had chlamydia (51/475))18 and in Cite Soleil, an urban slum in 1994 (12% (110/897) had gonococcal or chlamydial cervical infection (or both)).18 19 A lower prevalence was reported among women accessing antenatal services in rural Central Plateau in 2003 (4.8% had chlamydia (84/1742), 1.3% had gonorrhoea (23/1727)) and in rural Grand’Anse in 2012 (1.9% had chlamydia (2/104), and 1% had gonorrhoea in 1% (1/104))20 21 which might suggest a geographic variation in the distribution of CT and NG in Haiti.

MSM in this study presented with higher rectal CT and NG infections than genital as also reported by other studies22–25; based on these findings, screening for both rectal and genital chlamydial and gonococcal infections would likely be a more effective strategy to identify and treat infected individuals, thus further contribute to HIV prevention.24 As many of these STI are asymptomatic, detecting and treating CT and NG infections might help reduce complications (eg, disseminated gonococcal infection) and ongoing transmission in these populations.26 27

While co-infections with STIs are consistently more frequent among people living with HIV, a significantly lower prevalence of CT was observed in the HIV infected subgroup in this study. HIV negative MSM might not have been exposed to risk reduction counselling for STI as much as people living with HIV/AIDS.28 HIV-uninfected men with urethral infections are at greater risk for HIV acquisition and in HIV-uninfected persons, diagnosis and treatment of rectal STI may decrease susceptibility to HIV.24 29–31 These findings also underline the importance to presumptively test and treat for CT and NG regardless of HIV status to reduce the risk for acquisition of STI (including HIV) in high-risk populations. STI screening could also act as an entry point to HIV prevention services like preexposure prophylaxis for HIV uninfected subgroups and could provide an opportunity to engage key populations living with HIV into care.26 27 32

We did not find any association between alcohol consumption, marital status, the number of sex partners in the past 6 months and the odds of having CT or NG infection as also reported by other studies.33 34 Although STIs were more prevalent in participants who reported inconsistent use of condom and lubricant, the differences were not statistically significant as also reported by others.35 Access to lubricant and other STI prevention services are lacking among MSM in Haiti which might explain the inconsistent use of lubricant.8

Finally, in Haiti, high level of the stigmatisation persists against MSM.1 4 Consequently, members of these communities usually have a double life: while engaging in heterosexual relationships they secretly have sex with other partners.6 MSM not only can transmit HIV and other STIs to men, but also to women and thus serve as a bridge for STI transmission into the general population.6 Additional studies, notably sexual transmission network analysis, are needed to characterise the dynamics of transmission within these populations and better define prevention strategies.

There are several limitations to our findings. Fear of discrimination and stigmatisation, discomfort to talk about sex (which is still a taboo) and disclose personal information might be a limited factor to reliable answers to the questionnaire beside our best efforts to provide a judgement-free environment for our study. The populations we tested at the seven key populations friendly health facilities in the metropolitan area of Port-au-Prince may not be representative of all MSM, thus, our findings may not be generalisable. The recruitment of self-identified MSM might not represent the population of MSM since the majority of them do not disclose their sexual behaviour. In addition to recall bias, fear of judgement might have affected the reliability of the participants’ answers and the quality of the data.

Conclusion

Given the high rates of CT and NG infections among MSM in the metropolitan area of Port-au-Prince, performing routine risk assessments and appropriate screening are critical to the sexual health of these populations and to prevent HIV in HIV-negative subgroups. Periodic risk assessment and testing for asymptomatic NG and CT infections should be offered in Haiti as part of the upcoming guideline on STI management. A comprehensive strategy with tailored services and STI algorithms for MSM should be included in the new guidelines to improve the sexual health of key populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the doctors, nurses and laboratory technicians from the seven health facilities, as well as the project managers from their umbrella organisations (FOSREF and Serovie) who made this research possible.

Footnotes

Contributors: FJL: Research design, protocol development, data analysis and writing of the manuscript. GG, ML, EP: Implementation of the research, data collection and review of the manuscript. IJ, JoB, JaB: laboratory testing and review of the manuscript. JWD, RJF: protocol development, review of the manuscript. All coauthors revised the manuscript before submission.

Funding: This work was supported by the United States Agency for International Development grant number (AID-OAA-A1 S0070).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The Haiti National Bioethics Committee (Ref: 1718-46) and Institutional Review Board of the University of California San Diego (Project# 180456) approved the protocol for this project.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Ministère de la Santé Publique et de la Population (MSPP) Enquête Mortalité, Morbidité et utilisation des services (EMMUS-VI) 2016-2017, 2018. https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR326/FR326.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deschamps MM, Pape JW, Hafner A, et al. Heterosexual transmission of HIV in Haiti. Ann Intern Med 1996;125:324–30. 10.7326/0003-4819-125-4-199608150-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koenig S, Ivers L, Pace S, et al. Successes and challenges of HIV treatment programs in Haiti: aftermath of the earthquake. HIV Ther 2010;4:145–60. 10.2217/hiv.10.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministère de la Sante Publique et de la Population Programme National de Lutte Contre le VIH/Sida Rapport REDES 2014 et 2015 estimation Du flux des ressources et dépenses liées Au VIH/sida, 2016. Available: https://mspp.gouv.ht/site/downloads/Rapport%20Final%20REDES%202016.pdf [Accessed Jul 2019].

- 5.FHI 360 LINKAGES Programmatic mapping and size estimation of key populations in Haiti, 2017. Available: https://www.fhi360.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/resource-linkages-haiti-size-key-populations-april-2017.pdf [Accessed Jul 2019].

- 6.Pan American Health Organization Improving access of key populations to comprehensive HIV health services towards a Caribbean consensus, 2011. Available: https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2012/Access-of-Key-Populations-to-HIV-Health-Care-Consensus-document.pdf [Accessed Jul 2019].

- 7.Programme National de Lutte contre les IST/VIH/SIDA Bulletin de surveillance Epidemiologique VIHSida numero 13, 2017. Available: http://mspp.gouv.ht/site/downloads/Bulletin%20de%20Surveillance%20Epidemiologique%20VIH%20Sida%20numero14.pdf [Accessed Nov 2017].

- 8.Zalla LC, Herce ME, Edwards JK, et al. The burden of HIV among female sex workers, men who have sex with men and transgender women in Haiti: results from the 2016 priorities for local AIDS control efforts (place) study. J Int AIDS Soc 2019;22:e25281 10.1002/jia2.25281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV prevention through early detection and treatment of other sexually transmitted diseases--United States. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee for HIV and STD prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep 1998;47:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayes R, Wawer M, Gray R, et al. Randomised trials of STD treatment for HIV prevention: report of an international workshop. HIV/STD trials workshop group. Genitourin Med 1997;73:432–43. 10.1136/sti.73.6.432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laga M, Diallo M, Buve A. Interrelationship of sexually transmitted diseases and HIV: where are we now? 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wasserheit JN. Epidemiological synergy. Interrelationships between human immunodeficiency virus infection and other sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis 1992;19:61–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galvin SR, Cohen MS. The role of sexually transmitted diseases in HIV transmission. Nat Rev Microbiol 2004;2:33–42. 10.1038/nrmicro794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunt PW. Hiv and inflammation: mechanisms and consequences. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2012;9:139–47. 10.1007/s11904-012-0118-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rebbapragada A, Kaul R. More than their sum in your parts: the mechanisms that underpin the mutually advantageous relationship between HIV and sexually transmitted infections. Drug Discov Today 2007;4:237–46. 10.1016/j.ddmec.2007.12.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization Guidelines: prevention and treatment of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men and transgender populations: recommendations for a public health approach 2011, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization Guidelines for the management of sexually transmitted infections, 2004. Available: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/p/printable.html#TopOfPage [Accessed Jul 2019].

- 18.Fitzgerald DW, Behets F, Caliendo A, et al. Economic hardship and sexually transmitted diseases in Haiti's rural Artibonite Valley. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2000;62:496–501. 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Behets FM, Desormeaux J, Joseph D, et al. Control of sexually transmitted diseases in Haiti: results and implications of a baseline study among pregnant women living in Cité SOLEIL Shantytowns. J Infect Dis 1995;172:764–71. 10.1093/infdis/172.3.764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jobe KA, Downey RF, Hammar D, et al. Epidemiology of sexually transmitted infections in rural southwestern Haiti: the Grand'Anse women's health study. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2014;91:881–6. 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith Fawzi MC, Lambert W, Singler JM, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of STDs in rural Haiti: implications for policy and programming in resource-poor settings. Int J STD AIDS 2003;14:848–53. 10.1258/095646203322556200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook RL, St George K, Silvestre AJ, et al. Prevalence of Chlamydia and gonorrhoea among a population of men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect 2002;78:190–3. 10.1136/sti.78.3.190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geisler WM, Whittington WLH, Suchland RJ, et al. Epidemiology of anorectal chlamydial and gonococcal infections among men having sex with men in Seattle: utilizing serovar and auxotype strain typing. Sex Transm Dis 2002;29:189–95. 10.1097/00007435-200204000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kent CK, Chaw JK, Wong W, et al. Prevalence of rectal, urethral, and pharyngeal Chlamydia and gonorrhea detected in 2 clinical settings among men who have sex with men: San Francisco, California, 2003. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41:67–74. 10.1086/430704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rompalo AM, Price CB, Roberts PL, et al. Potential value of rectal-screening cultures for Chlamydia trachomatis in homosexual men. J Infect Dis 1986;153:888–92. 10.1093/infdis/153.5.888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ridpath AD, Chesson H, Marcus JL, et al. Screening Peter to save Paul. Sex Transm Dis 2018;45:623–5. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernstein KT, Marcus JL, Nieri G, et al. Rectal gonorrhea and Chlamydia reinfection is associated with increased risk of HIV seroconversion. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;53:537–43. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c3ef29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rietmeijer CA. Risk reduction counselling for prevention of sexually transmitted infections: how it works and how to make it work. Sex Transm Infect 2007;83:2–9. 10.1136/sti.2005.017319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Craib KJ, Meddings DR, Strathdee SA, et al. Rectal gonorrhoea as an independent risk factor for HIV infection in a cohort of homosexual men. Sex Transm Infect 1995;71:150–4. 10.1136/sti.71.3.150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect 1999;75:3–17. 10.1136/sti.75.1.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recent early syphilis, gonorrhea and Chlamydia among men who have sex with men increases risk for HIV seroconversion—San Francisco 2002–2003 [abstract T2-L203]. Atlanta: Program and abstracts of the 2003 National HIV Prevention Conference (Atlanta), 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tymejczyk OJK, Pathela P, Braunstein S, et al. Evidence of HIV care following STD clinic visits by out-of-care HIV-positive persons. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections Boston MA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garofalo R, Hotton AL, Kuhns LM, et al. Incidence of HIV infection and sexually transmitted infections and related risk factors among very young men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016;72:79–86. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muraguri N, Tun W, Okal J, et al. Hiv and STI prevalence and risk factors among male sex workers and other men who have sex with men in Nairobi, Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015;68:91–6. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang L-G, Zhang X-H, Zhao P-Z, et al. Gonorrhea and Chlamydia prevalence in different anatomical sites among men who have sex with men: a cross-sectional study in Guangzhou, China. BMC Infect Dis 2018;18:675 10.1186/s12879-018-3579-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.