Abstract

Background

Pubic or perineal shaving is a procedure performed before birth in order to lessen the risk of infection if there is a spontaneous perineal tear or if an episiotomy is performed.

Objectives

To assess the effects of routine perineal shaving before birth on maternal and neonatal outcomes, according to the best available evidence.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (12 June 2014).

Selection criteria

All controlled trials (including quasi‐randomised) that compare perineal shaving versus no perineal shaving.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed all potential studies for inclusion, assessed risk of bias and extracted the data using a predesigned form. Data were checked for accuracy.

Main results

Three randomised controlled trials (1039 women) published between 1922 and 2005 fulfilled the prespecified criteria. In the earliest trial, 389 women were alternately allocated to receive either skin preparation and perineal shaving or clipping of vulval hair only. In the second trial, which included 150 participants, perineal shaving was compared with the cutting of long hairs for procedures only. In the third and most recent trial, 500 women were randomly allocated to shaving of perineal area or cutting of perineal hair. The primary outcome for all three trials was maternal febrile morbidity; no differences were found (risk ratio (RR) 1.14, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.73 to 1.76). No differences were found in terms of perineal wound infection (RR 1.47, 95% CI 0.80 to 2.70) and perineal wound dehiscence (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.01 to 8.00) in the most recent trial involving 500 women, which was the only trial to assess these outcomes. In the smallest trial, fewer women who had not been shaved had Gram‐negative bacterial colonisation compared with women who had been shaved (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.98). There were no instances of neonatal infection in either group in the one trial that reported this outcome. There were no differences in maternal satisfaction between groups in the larger trial reporting this outcome (mean difference (MD) 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.13 to 0.13). No trial reported on perineal trauma. One trial reported on side‐effects and these included irritation, redness, burning and itching.

The overall quality of evidence ranged from very low (for the outcomes postpartum maternal febrile morbidity and neonatal infection) to low (for the outcome maternal satisfaction and wound infection).

Authors' conclusions

There is insufficient evidence to recommend perineal shaving for women on admission in labour.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Labor, Obstetric; Perineum; Confidence Intervals; Hair Removal; Hair Removal/methods; Odds Ratio; Patient Admission; Patient Satisfaction; Pregnancy Outcome; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Routinely shaving women in the area around the vagina on admission to hospital in labour

Women may have their pubic hairs shaved with a razor (perineal shaving) when they are admitted to hospital to give childbirth. This is done in the belief that shaving reduces the risk of infection if the perineum tears or a episiotomy is performed and that it makes suturing easier and helps with instrumental deliveries. Shaving is a routine procedure in some countries. Three controlled trials that involved a total of 1039 women were reported on between 1922 and 2005. They each used an antiseptic skin preparation and compared perineal shaving with cutting vulval hairs. The overall quality of evidence ranged from very low (for the outcomes postpartum maternal febrile morbidity and neonatal infection) to low (for the outcomes wound infection and maternal satisfaction). When the findings of the trials were combined, no differences were found, with and without shaving, on the number of mothers who experiencing high body temperatures after the birth. One trial also looked at perineal wound infection, the incidence of open wounds and maternal satisfaction immediately after a perineal repair had been completed and found no difference between groups. Most of the side‐effects attributable to shaving occurred later, as described by one of the trials. These included irritation, redness, multiple superficial scratches from the razor and burning and itching of the vulva. One trial assessed maternal satisfaction and found no difference between groups. Other outcomes such as pain, embarrassment or discomfort during hair regrowth, were not reported. The present review found no evidence of any clinical benefit with perineal shaving. Not routinely shaving women before labour appeared safe.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. routine perineal shaving before childbirth for women in labour.

| Routine perineal shaving before childbirth for women in labour | ||||||

| Population: Women in labour Settings: Hospitals in US (Baltimore, Dallas) and Thailand (Bangkok) Intervention: Routine perineal shaving before childbirth versus clipping of long pubic hairs or cutting of perineal hairs | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Routine perineal shaving before childbirth | |||||

| Postpartum maternal febrile morbidity | Study population | RR 1.16 (0.74 to 1.80) | 997 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | ||

| 67 per 1000 | 77 per 1000 (48 to 119) | |||||

| Low | ||||||

| 18 per 1000 | 20 per 1000 (12 to 33) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 124 per 1000 | 141 per 1000 (90 to 213) | |||||

| Neonatal infection | Study population | Not estimable | 458 (1 study) | see comment | The outcome was reported with no events. | |

| See comment | See comment | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| Wound infection | Study population | RR 1.47 (0.80 to 2.70) | 458 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3 | ||

| 70 per 1000 | 103 per 1000 (57 to 180) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 70 per 1000 | 103 per 1000 (56 to 179) | |||||

| Maternal satisfaction Scale from 1 to 5 | The mean maternal satisfaction in the control groups was 3.8 (five degrees)4 | The mean maternal satisfaction in the intervention groups was 0 higher (0.13 lower to 0.13 higher) |

MD 0.00 (‐0.13, 0.13) |

458 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low5 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; MD: mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Most studies contributing data had serious design limitations. 2 Wide confidence interval crossing the line of no effect. 3The total cumulative study population is not very small (sample size 458) and the total number of events is 40, but the 95% confidence interval is very wide. 4Likert scales on five degrees to measure a women's intensity of satisfaction (5, excellent; 4, good; 3, average; 2, fair; and 1, poor). 5Wide confidence interval crossing the line of no effect and small sample size.

Background

Description of the condition

Childbirth preparation has traditionally included the practice of routine pubic hair removal, in the belief that this will lessen the risk of infection that could be caused by spontaneous perineal tear or episiotomy. It has also been suggested that perineal shaving is likely to make suturing easier and safer (Kantor 1965; Kovavisarach 2005).

Description of the intervention

Pubic or external genitals hair removal with a razor is also known as perineal shaving. This procedure is performed before childbirth in an attempt to reduce maternal and/or neonatal morbidity.

How the intervention might work

A hairless site may increase the ease in which perineal trauma is sutured, as this may enable better access and clearer observation of the wound. However, using a razor to shave the perineum can create cutaneous microlacerations that may lead to colonisation with micro‐organisms (Briggs 1997). Furthermore, perineal shaving may be disliked by the woman (Oakley 1979), may cause discomfort during the period of hair regrowth (Kantor 1965) and may cause maternal embarrassment (Romney 1980). A study investigated the prevalence and correlates of complications related to pubic hair removal in a diverse clinical sample of women attending a public clinic (DeMaria 2014). In this sample, 60% experienced at least one health complication because of the removal, of which the most common were epidermal abrasion and ingrown hairs.

Why it is important to do this review

Six randomised controlled trials (972 participants) were systematically reviewed for preoperative hair removal to reduce surgical site infection in the general population (Tanner 2011). Two of the studies had three comparison arms that compared hair removal (shaving, clipping, or depilatory cream) with no hair removal. No statistically significant difference was found in surgical site infections between trial arms, within these studies. Furthermore, the studies were underpowered to compare infection rates. A further three trials (1343 participants) that compared shaving with clipping showed significance in surgical site infections associated with shaving (risk ratio (RR) 2.09, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.15 to 3.80).

Routine shaving is a procedure that has been discontinued in some countries, but still performed in many other high‐, middle‐ and lower‐income countries (Qian 2001; Colomar 2004; d'Orsi 2005; Chen 2006; Conde‐Agudelo 2008; Sweidan 2008; Charrier 2010; SEA‐ORCHID 2011; Altaweli 2014; Nagpal 2014).

The aim of this review is to identify whether perineal shaving reduces maternal and/or neonatal morbidity when performed on admission in labour.

Objectives

The objective of this review is to determine the effects of perineal shaving compared with no shaving prior to birth. The scientific evidence provided by this review will enable purchasers, providers and consumers of health care to decide the most appropriate form of care in terms of both health gain and cost.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All identified controlled trials (including quasi‐randomised) that compare routine perineal shaving with no perineal shaving prior to birth. Cross‐over trials and cluster‐randomised trials are not eligible for inclusion.

Types of participants

All primiparous and multiparous women, irrespective of mode of delivery, with or without perineal trauma.

Types of interventions

All controlled trial comparisons of perineal shaving versus no perineal shaving prior to birth.

Comparisons eligible for inclusion include:

perineal shaving versus no intervention;

perineal shaving verus control (e.g. a different method or area of hair removal such as clipping or cutting of pubic/vulval or perineal hair).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Postpartum maternal febrile morbidity: clinical signs or symptoms (persistent temperature of at least 37.5 degrees centigrade, tachycardia), and an elevated white blood cell count (at least 20,000/mm³).

Wound infection: persistent temperature of at least 37.5 degrees centigrade with clinical symptoms such as localised erythema and/or discharge and/or a positive wound swab culture with an organism likely to cause infection.

Neonatal infection: if the baby had one or more of the following: probable sepsis; probable meningitis; or probable pneumonia. This will be considered present if the baby has clinical signs/symptoms (respiratory distress, irritability, temperature instability, feeding difficulties, early onset jaundice, poor perfusion, hypotension, apnoea, seizures, tachycardia, lethargy), and either an abnormal sepsis screen or abnormal cerebrospinal fluid finding.

Poorly defined outcomes were included for information purposes only.

Secondary outcomes

Psychological outcomes: level of discomfort, degree of pain, degree of embarrassment and level of maternal satisfaction.

Perineal trauma.

Wound dehiscence and need for wound resuturing.

Side‐effects (not pre‐specified).

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Electronic searches

We contacted the Trials Search Co‐ordinator to search the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (12 June 2014).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of Embase;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and Embase, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For methods used in the previous update, please see Basevi 2000.

For this update, no new studies were identified from the updated search. However, full risk of bias was performed and the quality of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach for all of the currently included studies as described below. In future updates, we will use the full methods outlined in Appendix 1.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies we identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion. We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2014) and checked for accuracy.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) and resolved any disagreements by discussion.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We investigated for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We investigated for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding would be unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes.

We assessed the methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We investigated for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), whether reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We investigated for each included study the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We investigated for each included study any important concerns we have about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias;

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies are at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we consider it is likely to impact on the findings.

For this update the quality of the evidence has been assessed using the GRADE approach (Schunemann 2009) in order to assess the quality of the body of evidence relating to the following key outcomes for the main comparison.

Postpartum maternal febrile morbidity.

Neonatal infection.

Wound infection.

Maternal satisfaction (continuous data).

GRADEprofiler (GRADE 2008) has been used to import data from Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 2014) in order to create ’Summary of findings’ tables. A summary of the intervention effect and a measure of quality for each of the above outcomes has been produced using the GRADE approach. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence can be downgraded from 'high quality' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference as the outcome taken into account was measured in a single trial.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials and cross‐over trials are not eligible for inclusion.

Dealing with missing data

For two of the included studies, it was not possible to determine levels of attrition. In the next update of this review, if additional trials are included, we will conduct a sensitivity analysis, with poor quality studies with high levels of missing data excluded from the analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if the I² was greater than 60% and either the Tau² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

In the future updates, If there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2014). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it is reasonable to assume that studies are estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials are examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods are judged sufficiently similar. If there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we planned to use random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary if an average treatment effect across trials is considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary will be treated as the average of the range of possible treatment effects and we will discuss the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. We did not use random‐effects analysis in this update. If we use random‐effects analyses in future updates, the results will be presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Three randomised controlled trials involving 1039 women were identified where perineal shaving was compared with no shaving.

Included studies

In the earliest trial (Johnston 1922), 389 women were alternately allocated to receive either skin preparation and perineal shaving (control) or clipping of vulval hair only (experimental). This was carried out as part of a larger trial which assessed the potential benefits of the study hospital's admission procedure. The routine skin preparation included scrubbing of external genitalia and inner thighs with soap and water and, if labour was imminent, vulval douching with sterile water, alcohol and a weak solution of bichloride of mercury. The second trial (Kantor 1965), which included 150 women, compared perineal shaving versus the cutting of long hairs for procedures only. Fifty women in each arm received pHisoHex wash as skin preparation and 25 in each arm received povidone‐iodine spray.

The third trial (Kovavisarach 2005) included 500 women. In this trial, 42 women were excluded after randomisation due to caesarean section. The trial compared perineal shaving versus cutting of perineal hair, down to 0.5 cm above the skin. In all women the perineal region was scrubbed with 4% chlorhexidine scrub and rinsed with savlon solution (1:100).

Excluded studies

No studies were excluded.

Risk of bias in included studies

For some domains the trials lacked adequate descriptions of methods to allow judgements on risk of bias, and so have been classified as unclear.

See Figure 1 and Figure 2 for a summary of 'Risk of bias' assessments.

1.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

(1) Random sequence generation

The Johnston trial (Johnston 1922) assessed perineal shaving in 389 women as part of a larger study (N = 1059), which explored general preparation for childbirth. Women were alternately allocated to experimental or control group. There is no information on the timing of allocation, the personnel involved, or the number of exclusions during this process. We judged this study to be at high risk of selection bias. In the Kantor trial (Kantor 1965), which includes 150 participants, the method for determining the randomisation sequence was not mentioned; we judged there was insufficient information about the sequence generation process (unclear risk of bias). One study (Kovavisarach 2005) reported having used a published table of random sequence generation (low risk of bias).

(2) Allocation concealment

Neither Johnston 1922 nor Kantor 1965 provided sufficient detail about allocation sequence concealment and therefore the quality was difficult to assess. In particular, the method of allocation was unclear and, as such, we considered both these studies to be at high risk of selection bias. In the third trial (Kovavisarach 2005), 500 women admitted to the labour room were randomly allocated to receive either perineal shaving or perineal hair cutting using a series of sealed sequentially numbered envelopes, therefore we considered this to be at low risk of bias.

Blinding

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias)

Because blinding of participants and personnel was not possible due to the nature of the intervention, all the trials present a high risk of bias.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias)

None of the three included studies described blinding of outcome assessors. Because it is likely that staff evaluating outcomes would be aware of treatment allocation, these studies have been assessed as high risk of bias due to lack of blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

For the Johnston trial (Johnston 1922) and the Kantor trial (Kantor 1965), it is not possible to determine the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We judged these studies to be at unclear risk of bias. The Kovavisarach trial (Kovavisarach 2005) has no missing outcome data and is therefore at low risk of attrition bias.

Selective reporting

In two trials (Johnston 1922; Kantor 1965), selective reporting was at unclear risk of bias. In the Kovavisarach trial (Kovavisarach 2005), we have insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘low risk’ or ‘high risk’ of reporting bias, but it seems unlikely that not all of the study’s pre‐specified primary outcomes have been reported.

Other potential sources of bias

In the Kovavisarach trial (Kovavisarach 2005), there was a statistically significant difference in the mean gestational age between the groups (0.30 week) but, like the authors, we could not determine any clinical relevance of this finding and, therefore, it is not identified as a source of bias.

No study provides information on sources of funding but, given the characteristics of intervention and the direction of results, it seems unlikely that this problem could introduce bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Perineal shaving versus no perineal shaving

Three trials (Johnston 1922; Kantor 1965; Kovavisarach 2005) were identified by the search (1039 women).

Primary outcomes

Postpartum maternal febrile morbidity

In the Johnston 1922 trial, the primary outcome was maternal febrile morbidity, defined as temperature 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit or above on two successive days (excluding the day of delivery), and taken every four hours. No significant differences were found between the trial arms (risk ratio (RR) 1.31, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.74 to 1.80). There was no microbiological evidence to suggest differences in maternal infection between groups.

In the Kantor 1965 trial, no significant differences were found between those women who had or had not received a perineal shave with regard to maternal pyrexia during the four days after delivery (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.22 to 2.86).

In the Kovavisarach 2005 trial, no significant differences were found between those women who had or had not received a perineal shave with regard to puerperal morbidity, defined as temperature 38.0 degrees centigrade (100.4 degrees Fahrenheit) or higher, arising on any two of the first 10 days postpartum, exclusive of the first 24 hours; the oral temperature was taken at least four times daily (RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.09 to 2.66).

When the findings of all the trials were combined, no differences were found in those who had or had not been shaved with regard to maternal febrile morbidity (three trials, N = 997; RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.76), Analysis 1.1.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Perineal shaving versus no perineal shaving, Outcome 1 Postpartum maternal febrile morbidity.

In the Kantor trial (Kantor 1965), there were no differences in Gram‐positive bacteria colonization. A significant difference was found in the number of women who were colonized by Gram‐negative bacteria (one trial, N = 150; RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.98) in favour of those who had been shaved, Analysis 1.2.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Perineal shaving versus no perineal shaving, Outcome 2 Colonisation.

Wound infection, wound dehiscence and need for wound resuturing

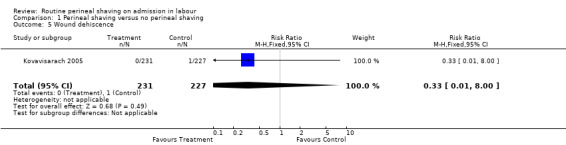

Only the Kovavisarach 2005 trial assessed this outcome. No statistically significant differences were found between the trial arms with regard to perineal wound infection, defined as pain and erythema of the surgical margins of perineal or episiotomy wound with or without serous or purulent discharge (one trial, N = 458; RR 1.47, 95% CI 0.80 to 2.70), Analysis 1.4, and perineal wound dehiscence (one trial, N = 458; RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.01 to 8.00), Analysis 1.5.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Perineal shaving versus no perineal shaving, Outcome 4 Wound infection.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Perineal shaving versus no perineal shaving, Outcome 5 Wound dehiscence.

Neonatal infection

Only the Kovavisarach 2005 trial assessed this outcome and reported no instances of neonatal infection in either group.

Secondary outcomes

Maternal satisfaction

Only the Kovavisarach 2005 trial assessed this outcome. A five‐point Likert scale was used to measure a women's intensity of satisfaction (5, excellent; 4, good; 3, average; 2; fair and 1; poor). No significant difference was found between the trial arms (one trial, N = 458; mean difference (MD) 0.00; 95% CI ‐0.13 to 0.13), Analysis 1.11.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Perineal shaving versus no perineal shaving, Outcome 11 Maternal satisfaction continuous data.

Perineal trauma

No trial reported this outcome.

Side‐effects (not pre‐specified)

Only the Kantor 1965 trial described the side‐effects experienced by the women who had been shaved. This included irritation, redness, multiple superficial scratches and burning and itching of the vulva. As the number of side‐effects was not reported for women in the unshaved group, this information could not be included in the analysis. The Johnston 1922 and Kovavisarach 2005 trials made no reference to any side‐effects attributable to shaving.

Discussion

Summary of main results

All the trials provided a limited assessment of the effects of perineal shaving. In particular, only one trial (Kovavisarach 2005) assessed neonatal outcomes and maternal satisfaction. No trial assessed the outcomes associated with maternal views such as pain, embarrassment or discomfort. Although a significant difference was found in the number of women who had colonised Gram‐negative bacteria in favour of those who had been shaved (Kantor 1965), when combined with Gram‐positive bacteria no differences were found. Moreover, all cases of maternal pyrexia were attributed to other causes, i.e. urinary tract infection and endometritis (Kantor 1965). The most recent and larger trial found no differences between the trial arms on perineal wound infection and dehiscence and puerperal morbidity and infection (Kovavisarach 2005). No significant differences were found between those women who had or had not received a perineal shave with regard to maternal satisfaction, evaluated immediately after perineal repair had finished (Kovavisarach 2005). However, the timing of assessment could be unsuitable, because most of the side‐effects attributable to shaving are late complications.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

A comprehensive and extensive literature review was performed to identify studies that assessed the benefits and harms of routine perineal shaving before childbirth. The findings can be equally applied to different birth environments, to high‐, middle‐ and lower‐income countries, to out‐of‐hospital settings, or to setting where skilled birth attendants are available and setting where skilled birth attendants are not present.

Quality of the evidence

Two of the three trials (Johnston 1922; Kantor 1965) identified by the initial search were more than 40 years old which may have accounted for the poor reporting of information. This also meant that personal communication to seek additional information about the trials was not possible. The Johnston trial (Johnston 1922) was, in fact, the first trial registered in the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's register. The quality of two of the three included studies (Johnston 1922; Kantor 1965) was very low. The main limitations in the quality of these studies were adequate sequence generation and concealment of allocation. The lack of adequate sequence generation and allocation concealment can lead to biased estimates of treatment effects. Due to the features and the modes of intervention, blinding of participants and personnel was impossible. For blinding of outcome assessors, blinding also was absent in all studies. This was considered a high risk of bias because clinicians’ assessment and management could be influenced by knowledge of the treatment group. The quality of the evidence was assessed according to the GRADE approach and is displayed in Table 1. The overall quality of evidence ranged from very low (for the outcomes postpartum maternal febrile morbidity, neonatal infection) to low (for the outcomes maternal satisfaction, wound infection).

Potential biases in the review process

The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (12 June 2014) and we searched reference lists of included trials. In two of the three trials, clarification of information with authors was not possible as the trials were very old. Given that all included studies presented results not favourable to the intervention investigated, it seems unlikely, although not impossible, that we missed unpublished data presented at smaller conferences or studies published in non‐English language or in non‐indexed journals.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This review agrees with a systematic review published in 2011 (Tanner 2011) that evaluated if routine pre‐operative hair removal (compared with no removal) and the method of hair removal (shaving, clipping, or depilatory cream) influence rates of surgical site infections. The systematic review included three trials (1343 participants) that compared shaving with clipping and found significantly more surgical site infections associated with shaving (RR 2.09, 95% CI 1.15 to 3.80). In the same systematic review, six trials (972 participants) compared hair removal (shaving, clipping, or depilatory cream) with no hair removal and showed no statistically significant difference in surgical site infections rates; however, the comparison is underpowered.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is insufficient evidence to suggest that perineal shaving confers any benefit to women on admission in labour. The clinical significance of the difference in women having Gram‐negative bacteria is uncertain. Furthermore, the potential for side‐effects suggests that shaving should not be part of routine clinical practice.

All three trials identified included the clipping of long hairs in their control groups to aid in operative procedures. This process is carried out for practical reasons, i.e. when performing instrumental deliveries or carrying out perineal repairs.

Implications for research.

It is unlikely that further randomised controlled trials on routine perineal shaving on admission in labour may provide additional information on maternal morbidity and perineal wound infections. In settings where midwives and doctors continue to perform routine perineal shaving, surveys on knowledge, attitude and behaviour of professionals could be useful to identify barriers and facilitators to change this practice.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 12 June 2014 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Search and methods updated. No new trials identified. 'Summary of findings' table incorporated. |

| 12 June 2014 | New search has been performed | Review updated. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 1998 Review first published: Issue 1, 2001

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 13 February 2009 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 2 January 2008 | New search has been performed | Search updated and one new trial identified. The conclusions have not changed. |

| 2 January 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 17 November 2003 | New search has been performed | Updated search. No new trials identified. |

Acknowledgements

This Cochrane review updates the pre‐Cochrane review undertaken by Prof Mary Renfrew in 1995 (Renfrew 1995).

We acknowledge Prof Zarko Alfirevic for his support and guidance and Dr Simona Di Mario for her support on the previous update of this review (Basevi 2000).

We would like to thank Erika Ota for her support in the creation of the 'Summary of findings' table for this update. Erika Ota's work was financially supported by the UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), Department of Reproductive Health and Research (RHR), World Health Organization. The named authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Methods to be used in future updates

Selection of studies

Two review authors will independently assess for inclusion all the potential studies we identify as a result of the search strategy. We will resolve any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we will consult a third person.

Data extraction and management

We will design a form to extract data. For eligible studies, at least two review authors will extract the data using the agreed form. We will resolve discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we will consult a third person. We will enter data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2014) and check for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above is unclear, we will attempt to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors will independently assess risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We will resolve any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We will describe for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We will assess the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We will describe for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and will assess whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We will assess the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We will describe for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We will consider that studies are at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judge that the lack of blinding would be unlikely to affect results. We will assess blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We will assess the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We will describe for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We will assess blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We will assess methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We will describe for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We will state whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information is reported, or can be supplied by the trial authors, we will re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertake.

We will assess methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We will describe for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We will assess the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We will describe for each included study any important concerns we have about other possible sources of bias.

We will assess whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias;

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We will make explicit judgements about whether studies are at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we will assess the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we consider it is likely to impact on the findings. We will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ see Sensitivity analysis.

We will assess the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach in order to assess the quality of evidence related to the following key outcomes (maximum of seven) (Schunemann 2009).

Postpartum maternal febrile morbidity.

Neonatal infection.

Wound infection.

Maternal satisfaction (continuous data).

GRADE profiler (GRADE 2008) will be used to import data from Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 2014) in order to create ’Summary of findings’ tables. A summary of the intervention effect and a measure of quality for each of the above outcomes will be produced using the GRADE approach to provide a measure of quality. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. For assessments of the overall quality of evidence for each outcome the evidence can be downgraded from 'high quality' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we will present results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we will use the mean difference if outcomes are measured in the same way between trials. We will use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but use different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials and cross‐over trials will not be eligible for inclusion in this review.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we will note levels of attrition. We will explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, we will carry out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we will attempt to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and all participants will be analysed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial will be the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes are known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We will assess statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² and Chi² statistics. We will regard heterogeneity as substantial if the I² is greater than 30% and either the Tau² is greater than zero, or there is a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We will carry out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2014). We will use fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it is reasonable to assume that studies are estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials are examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods are judged sufficiently similar. If there is clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differ between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity is detected, we will use random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary if an average treatment effect across trials is considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary will be treated as the average of the range of possible treatment effects and we will discuss the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect is not clinically meaningful, we will not combine trials.

If we use random‐effects analyses, the results will be presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If we identify substantial heterogeneity, we will investigate it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We will consider whether an overall summary is meaningful, and if it is, use random‐effects analysis to produce it.

We plan to carry out the following subgroup analyses for subsets of studies by:

random sequence generation and allocation concealment;

year of publication.

The following outcomes will be used in subgroup analysis:

postpartum maternal febrile morbidity, neonatal infection, maternal satisfaction.

We will assess subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2014). We will report the results of subgroup analyses quoting the Chi² statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

We will conduct a sensitivity analysis to explore the impact of attrition in trials, with poor quality studies with high levels of missing data being excluded from the analysis.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Perineal shaving versus no perineal shaving.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Postpartum maternal febrile morbidity | 3 | 997 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.73, 1.76] |

| 2 Colonisation | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Gram‐positive | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.16 [0.82, 1.64] |

| 2.2 Gram‐negative | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.70, 0.98] |

| 3 Neonatal infection | 1 | 458 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Wound infection | 1 | 458 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.47 [0.80, 2.70] |

| 5 Wound dehiscence | 1 | 458 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 8.00] |

| 6 Need for wound resuturing | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7 Discomfort | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8 Pain | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9 Maternal embarrassment | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10 Maternal satisfaction | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11 Maternal satisfaction continuous data | 1 | 458 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [‐0.13, 0.13] |

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Perineal shaving versus no perineal shaving, Outcome 3 Neonatal infection.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Johnston 1922.

| Methods | Alternate allocation. | |

| Participants | 389 women in labour.

Exclusions criteria: caesarean section; previously identified infection; eclampsia; postpartum admissions. USA. |

|

| Interventions | Pubic shaving plus the usual skin preparation (scrubbing of the external genitalia and inner thighs with green soap and water and the pouring of sterile water, alcohol and a weak solution of bichloride of mercury over the vulva and adjoining area) (N = 196) versus clipping of long pubic hairs only (no skin preparation) (N = 193). | |

| Outcomes | Febrile puerperia. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Women alternately allocated to experimental or control group. No information on the timing of allocation, the personnel involved, or the number of exclusions during this process. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | No sufficient detail about allocation sequence concealment. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Blinding not possible due to the nature of the intervention. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No mention of blinding of outcome assessors. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not possible to determine the completeness of data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias identified. |

Kantor 1965.

| Methods | Method of allocation not specified. | |

| Participants | 150 labouring women pre delivery. USA. |

|

| Interventions | First comparison: shaving of the pudendal and perineal areas (N = 50) versus clipping of long pubic hairs (N = 50). In all women the pudendal and perineal region was washed with a diluted pHisoHex solution. Second comparison: shaving of the pudendal and perineal areas (N = 25) versus clipping of long pubic hairs (N = 25). All women received povidone‐iodine spray as skin preparation, after washing to remove pHisoHex. | |

| Outcomes | Positive bacteriology cultures (gram positive and negative). Maternal pyrexia. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method for determining the randomisation sequence not mentioned; insufficient information about the sequence generation process. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Insufficient detail about allocation sequence concealment. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Blinding not possible due to the nature of the intervention. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No mention of blinding of outcome assessors. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not possible to determine the completeness of data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias identified. |

Kovavisarach 2005.

| Methods | Random allocation from a table of random numbers with sequentially numbered, sealed envelopes. | |

| Participants | 500 pregnant women recruited from 1 hospital. 42 women excluded after randomisation due to caesarean section.

Study period: November 2001‐February 2002.

Inclusion criteria: term pregnancy (gestational age 37‐42 weeks) true labour pain, singleton, cephalic presentation, living fetus. Exclusion criteria: women with medical or obstetric complications (e.g. premature rupture of membranes, HIV positive, treatment with antibiotics within 7 days of admission, birth canal or anal infection). Thailand. |

|

| Interventions | Perineal shaving (N = 231) versus cutting of perineal hair, down to 0.5 cm above the skin (N = 227). In all women the perineal region was scrubbed with 4% chlorhexidine scrub and rinsed with savlon solution (1:100). | |

| Outcomes | Perineal wound infection; puerperal morbidity; puerperal infection; neonatal infection; satisfaction of the patients, accoucheurs and perineorrhaphy operators. | |

| Notes | All women were attended by nurses, externs and obstetrics‐gynaecology residents. The episiotomy wounds were repaired either by externs or residents under the supervision of the senior residents. The satisfaction of parturients was evaluated immediately after perineal repair had finished. The definition of puerperal infection was based on histopathological and not clinical criteria. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Use of a published table of random sequence generation. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Use of sealed sequentially numbered envelopes. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Blinding not possible due to the nature of the intervention. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No mention of blinding of outcome assessors. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No missing outcome data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias identified. |

Differences between protocol and review

The methods have been updated for the 2014 update and the quality of the evidence assessed using GRADE in order to assess the quality of the body of evidence relating to key outcomes. We added 'side‐effects' as a non‐prespecified outcome.

Contributions of authors

Vittorio Basevi wrote the protocol and Tina Lavender commented. Tina Lavender and Vittorio Basevi wrote the review. Vittorio Basevi extracted the data and Tina Lavender checked the data.

Vittorio Basevi drafted the 2014 updated and Tina Lavender commented on drafts.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Direzione generale sanità e politiche sociali,Regione Emilia‐Romagna,Bologna, Italy.

External sources

UNDP‐UNFPA‐UNICEF‐WHO‐World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), Department of Reproductive Health and Research (RHR), World Health Organization, Switzerland.

Declarations of interest

None known.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Johnston 1922 {published data only}

- Johnston RA, Sidall RS. Is the usual method of preparing patients for delivery beneficial or necessary?. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1922;4:645‐50. [Google Scholar]

Kantor 1965 {published data only}

- Kantor HI, Rember R, Tabio P, Buchanon R. Value of shaving the pudendal‐perineal area in delivery preparation. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1965;25:509‐12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kovavisarach 2005 {published data only}

- Kovavisarach E, Jirasettasiri P. Randomised controlled trial of perineal shaving versus hair cutting in parturients on admission in labor. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand 2005;88:1167‐71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Altaweli 2014

- Altaweli RF, McCourt C, Baron M. Childbirth care practices in public sector facilities in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Midwifery 2014;30(7):899‐909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Briggs 1997

- Briggs M. Principles of closed surgical wound care. Journal of Wound Care 1997;6(6):288‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Charrier 2010

- Charrier L, Serafini P, Chiono V, Rebora M, Rabacchi G, Zotti CM. Clean and sterile delivery: two different approaches to infection control. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 2010;16(4):771‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chen 2006

- Chen CY, Wang KG. Are routine interventions necessary in normal birth?. Taiwan Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2006;45(4):302‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Colomar 2004

- Colomar M, Belizán M, Cafferata ML, Labandera A, Tomasso G, Althabe F, et al. Practices of maternal and perinatal care performed in public hospitals of Uruguay [Prácticas en la atención maternal y perinatal realizadas en los hospitals públicos de Uruguay]. Ginecologia y Obstetricia de Mexico 2004;72:455‐65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Conde‐Agudelo 2008

- Conde‐Agudelo A, Rosas‐Bermudez A, Gülmezoglu AM. Evidence‐based intrapartum care in Cali, Colombia: a quantitative and qualitative study. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 2008;115(12):1547‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

d'Orsi 2005

- d'Orsi E, Chor D, Giffin K, Angulo‐Tuesta A, Barbosa GP, Gama Ade S, et al. Quality of birth care in maternity hospitals of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil [Qualidade da atenção ao parto em maternidades do Rio de Janeiro]. Revista de Saúde Pública 2005;39(4):645‐54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

DeMaria 2014

- DeMaria AL, Flores M, Hirth JM, Berenson AB. Complications related to pubic hair removal. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2014;210(6):528.e1‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

GRADE 2008 [Computer program]

- Brozek J, Oxman A, Schünemann H. GRADEpro. Version 3.6. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008.

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Nagpal 2014

- Nagpal J, Sachdeva A, Sengupta Dhar R, Bhargava VL, Bhartia A. Widespread non‐adherence to evidence‐based maternity care guidelines: a population‐based cluster randomised household survey. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 2014 Aug 22 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI: 10.1111/1471-0528.13054] [DOI] [PubMed]

Oakley 1979

- Oakley A. Becoming A Mother. Oxford: Martin Robertson, 1979. [Google Scholar]

Qian 2001

- Qian X, Smith H, Zhou L, Liang J, Garner P. Evidence‐based obstetrics in four hospitals in China: An observational study to explore clinical practice, women's preferences and provider's views. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2001;1(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2014 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014.

Romney 1980

- Romney ML. Pre‐delivery shaving: an unjustified assault?. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1980;1:33‐5. [Google Scholar]

Schunemann 2009

- Schunemann HJ. GRADE: from grading the evidence to developing recommendations. A description of the system and a proposal regarding the transferability of the results of clinical research to clinical practice [GRADE: Von der Evidenz zur Empfehlung. Beschreibung des Systems und Losungsbeitrag zur Ubertragbarkeit von Studienergebnissen]. Zeitschrift fur Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualitat im Gesundheitswesen 2009;103(6):391‐400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

SEA‐ORCHID 2011

- SEA‐ORCHID Study Group, Lumbiganon P, McDonald SJ, Laopaiboon M, Turner T, Green S, Crowther CA. Impact of increasing capacity for generating and using research on maternal and perinatal health practices in South East Asia (SEA‐ORCHID Project). PLoS One 2011;6(9):e23994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sweidan 2008

- Sweidan M, Mahfoud Z, DeJong J. Hospital policies and practices concerning normal childbirth in Jordan. Studies in Family Planning 2008;39(1):59‐68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tanner 2011

- Tanner J, Norrie P, Melen K. Preoperative hair removal to reduce surgical site infection. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 11. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004122.pub4] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

Basevi 2000

- Basevi V, Lavender T. Routine perineal shaving on admission in labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2000, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001236] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Renfrew 1995

- Renfrew MJ. Routine perineal shaving on admission in labour. [revised 02 April 1992]. In: Enkin MW, Keirse MJNC, Renfrew MJ, Neilson JP, Crowther C (eds.) Pregnancy and Childbirth Module. In: The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Database [database on disk and CDROM]. The Cochrane Collaboration: Issue 2, Oxford: Update Software; 1995.