Abstract

Background

About 10% of reproductive‐aged women suffer from endometriosis, a costly chronic disease causing pelvic pain and subfertility. Laparoscopy is the gold standard diagnostic test for endometriosis, but is expensive and carries surgical risks. Currently, there are no non‐invasive or minimally invasive tests available in clinical practice to accurately diagnose endometriosis. Although other reviews have assessed the ability of blood tests to diagnose endometriosis, this is the first review to use Cochrane methods, providing an update on the rapidly expanding literature in this field.

Objectives

To evaluate blood biomarkers as replacement tests for diagnostic surgery and as triage tests to inform decisions on surgery for endometriosis. Specific objectives include:

1. To provide summary estimates of the diagnostic accuracy of blood biomarkers for the diagnosis of peritoneal, ovarian and deep infiltrating pelvic endometriosis, compared to surgical diagnosis as a reference standard.

2. To assess the diagnostic utility of biomarkers that could differentiate ovarian endometrioma from other ovarian masses.

Search methods

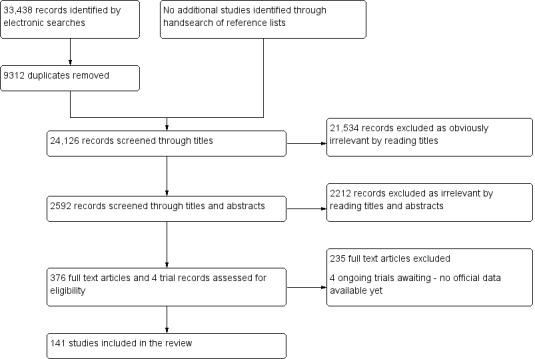

We did not restrict the searches to particular study designs, language or publication dates. We searched CENTRAL to July 2015, MEDLINE and EMBASE to May 2015, as well as these databases to 20 April 2015: CINAHL, PsycINFO, Web of Science, LILACS, OAIster, TRIP, ClinicalTrials.gov, DARE and PubMed.

Selection criteria

We considered published, peer‐reviewed, randomised controlled or cross‐sectional studies of any size, including prospectively collected samples from any population of reproductive‐aged women suspected of having one or more of the following target conditions: ovarian, peritoneal or deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE). We included studies comparing the diagnostic test accuracy of one or more blood biomarkers with the findings of surgical visualisation of endometriotic lesions.

Data collection and analysis

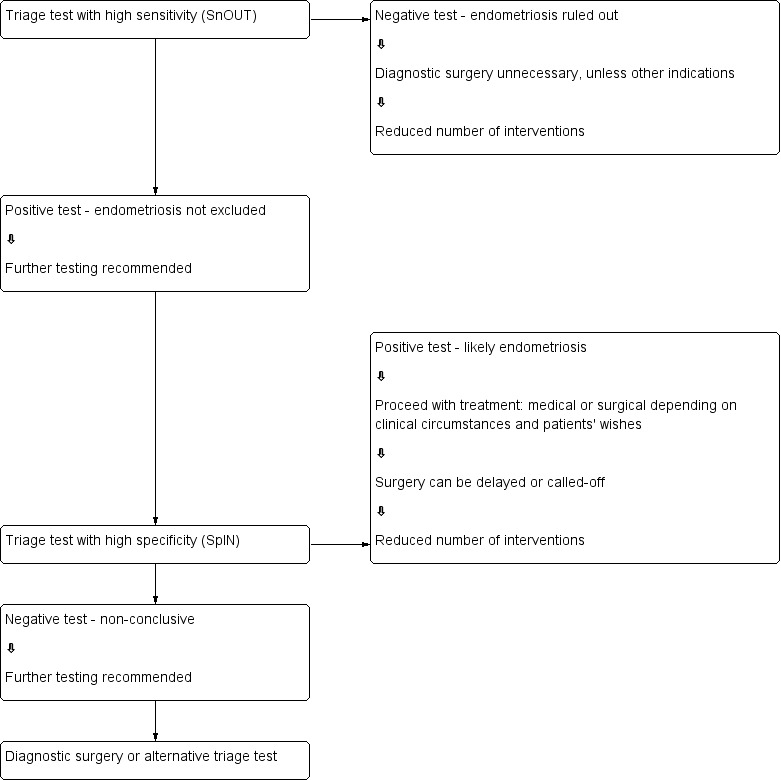

Two authors independently collected and performed a quality assessment of data from each study. For each diagnostic test, we classified the data as positive or negative for the surgical detection of endometriosis, and we calculated sensitivity and specificity estimates. We used the bivariate model to obtain pooled estimates of sensitivity and specificity whenever sufficient datasets were available. The predetermined criteria for a clinically useful blood test to replace diagnostic surgery were a sensitivity of 0.94 and a specificity of 0.79 to detect endometriosis. We set the criteria for triage tests at a sensitivity of ≥ 0.95 and a specificity of ≥ 0.50, which 'rules out' the diagnosis with high accuracy if there is a negative test result (SnOUT test), or a sensitivity of ≥ 0.50 and a specificity of ≥ 0.95, which 'rules in' the diagnosis with high accuracy if there is a positive result (SpIN test).

Main results

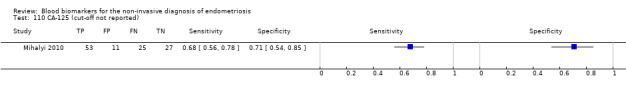

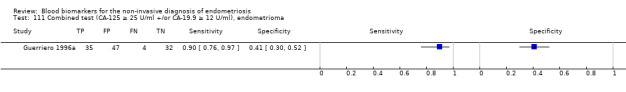

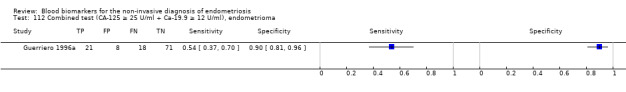

We included 141 studies that involved 15,141 participants and evaluated 122 blood biomarkers. All the studies were of poor methodological quality. Studies evaluated the blood biomarkers either in a specific phase of the menstrual cycle or irrespective of the cycle phase, and they tested for them in serum, plasma or whole blood. Included women were a selected population with a high frequency of endometriosis (10% to 85%), in which surgery was indicated for endometriosis, infertility work‐up or ovarian mass. Seventy studies evaluated the diagnostic performance of 47 blood biomarkers for endometriosis (44 single‐marker tests and 30 combined tests of two to six blood biomarkers). These were angiogenesis/growth factors, apoptosis markers, cell adhesion molecules, high‐throughput markers, hormonal markers, immune system/inflammatory markers, oxidative stress markers, microRNAs, tumour markers and other proteins. Most of these biomarkers were assessed in small individual studies, often using different cut‐off thresholds, and we could only perform meta‐analyses on the data sets for anti‐endometrial antibodies, interleukin‐6 (IL‐6), cancer antigen‐19.9 (CA‐19.9) and CA‐125. Diagnostic estimates varied significantly between studies for each of these biomarkers, and CA‐125 was the only marker with sufficient data to reliably assess sources of heterogeneity.

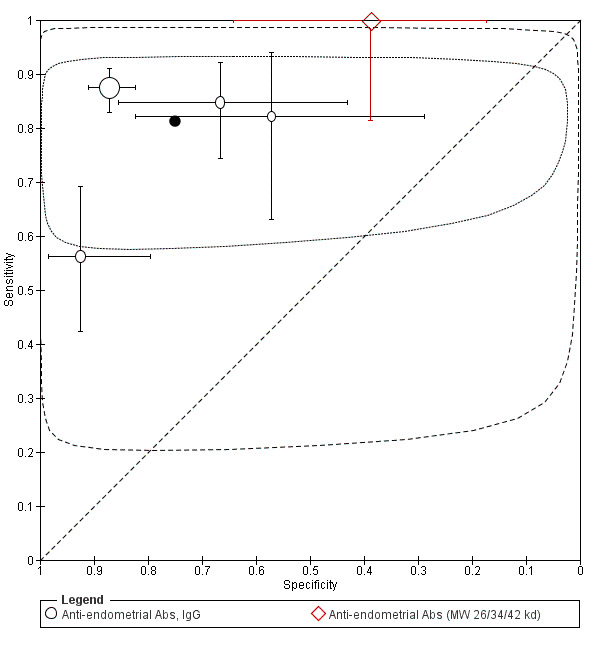

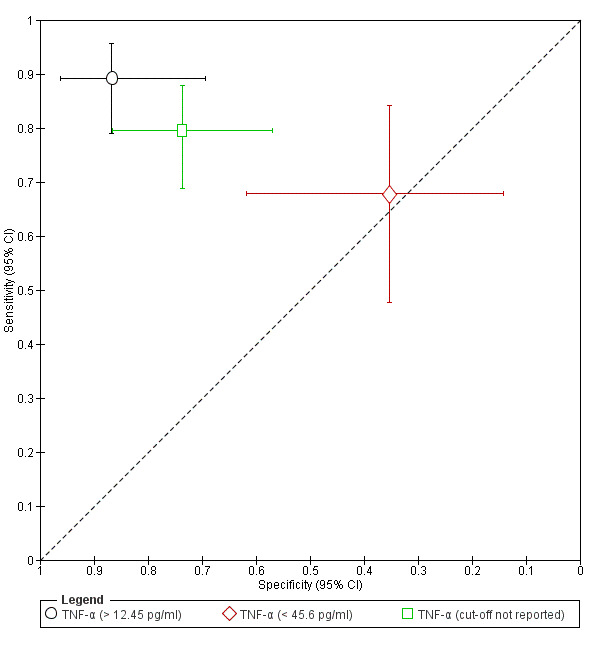

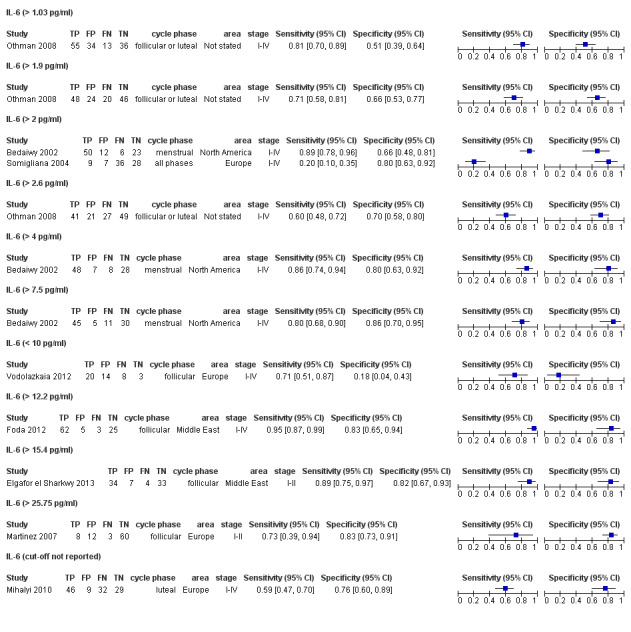

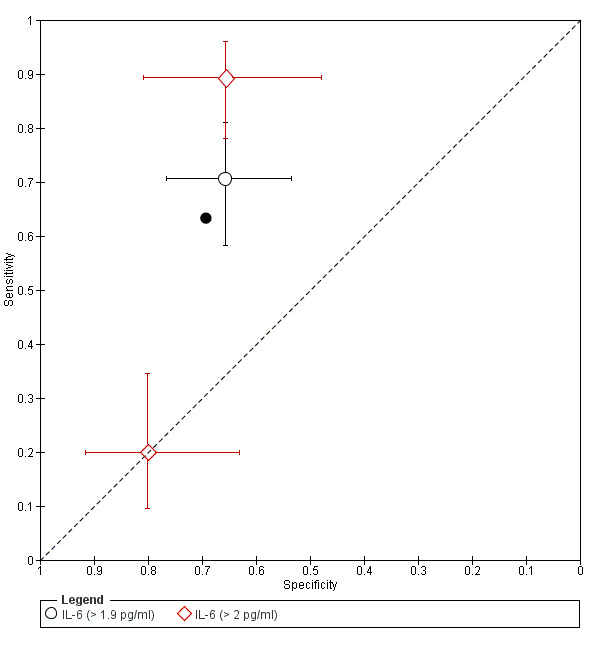

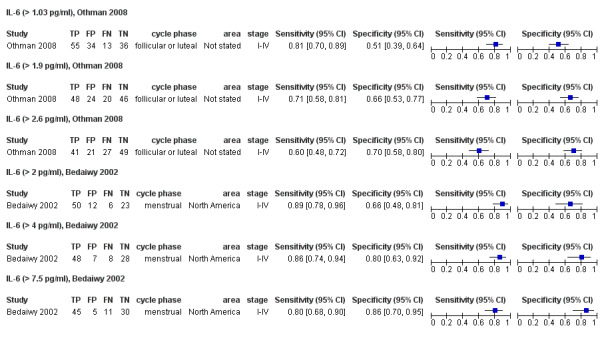

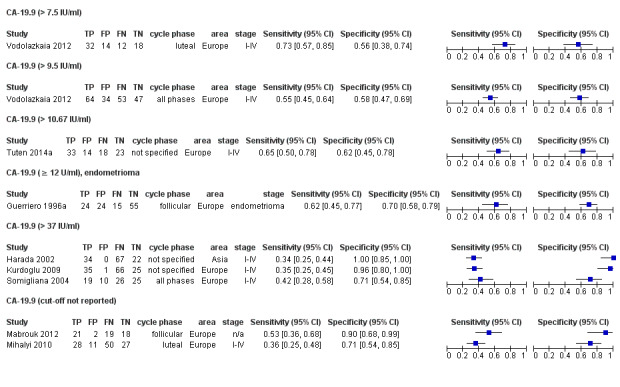

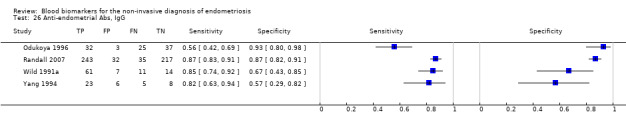

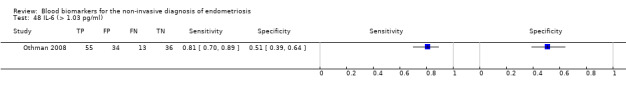

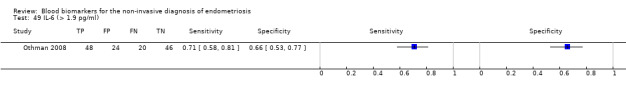

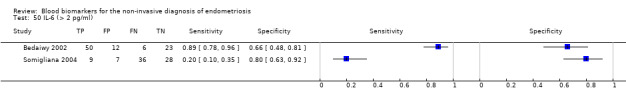

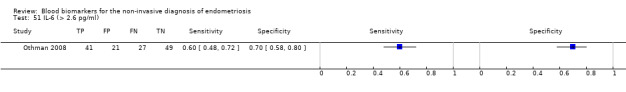

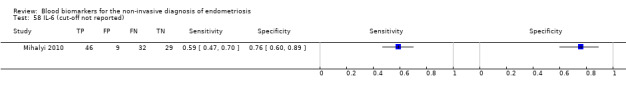

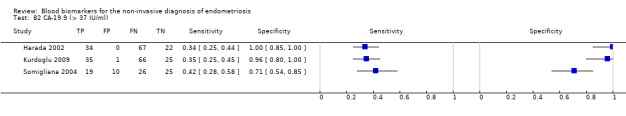

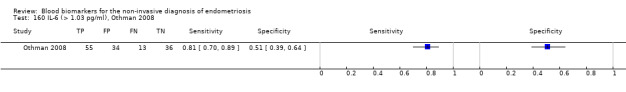

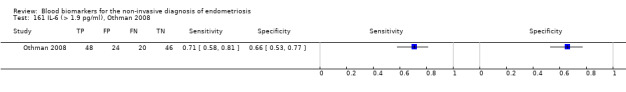

The mean sensitivities and specificities of anti‐endometrial antibodies (4 studies, 759 women) were 0.81 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.76 to 0.87) and 0.75 (95% CI 0.46 to 1.00). For IL‐6, with a cut‐off value of > 1.90 to 2.00 pg/ml (3 studies, 309 women), sensitivity was 0.63 (95% CI 0.52 to 0.75) and specificity was 0.69 (95% CI 0.57 to 0.82). For CA‐19.9, with a cut‐off value of > 37.0 IU/ml (3 studies, 330 women), sensitivity was 0.36 (95% CI 0.26 to 0.45) and specificity was 0.87 (95% CI 0.75 to 0.99).

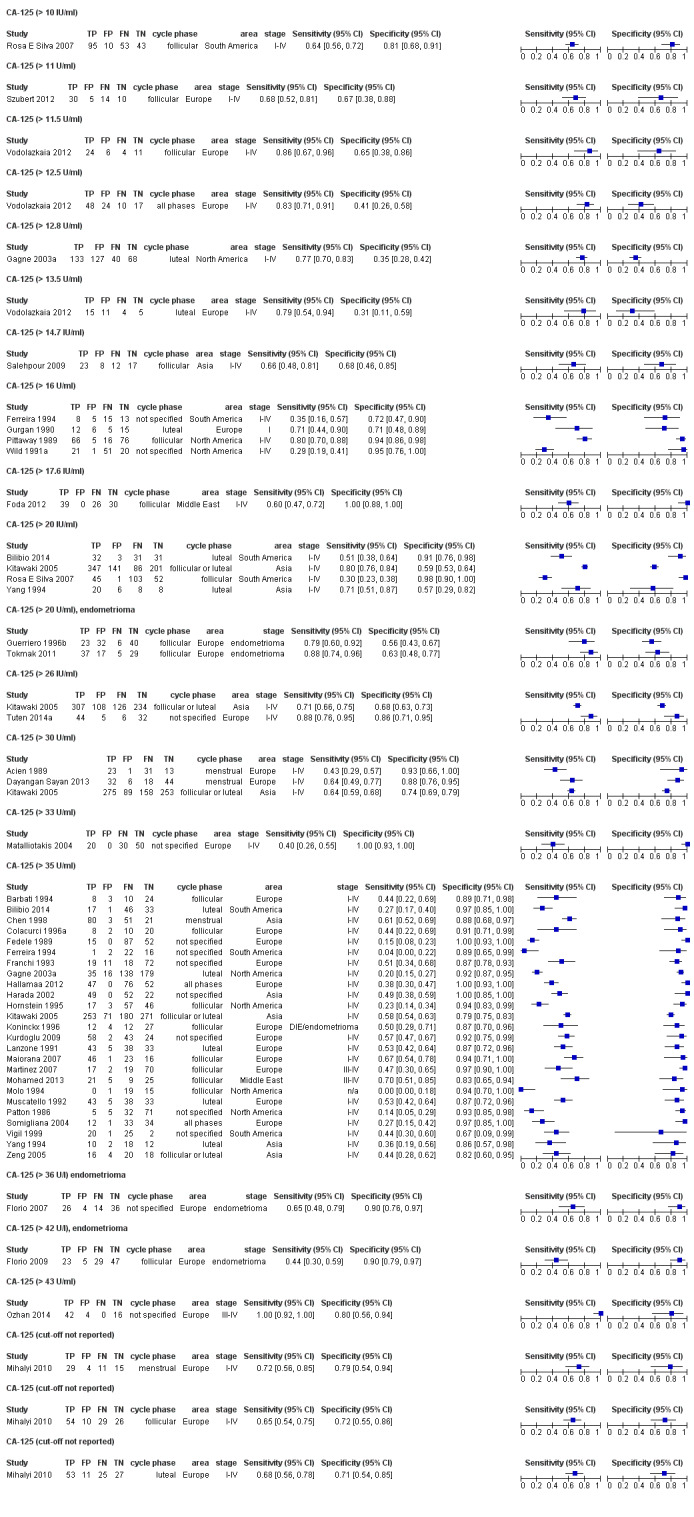

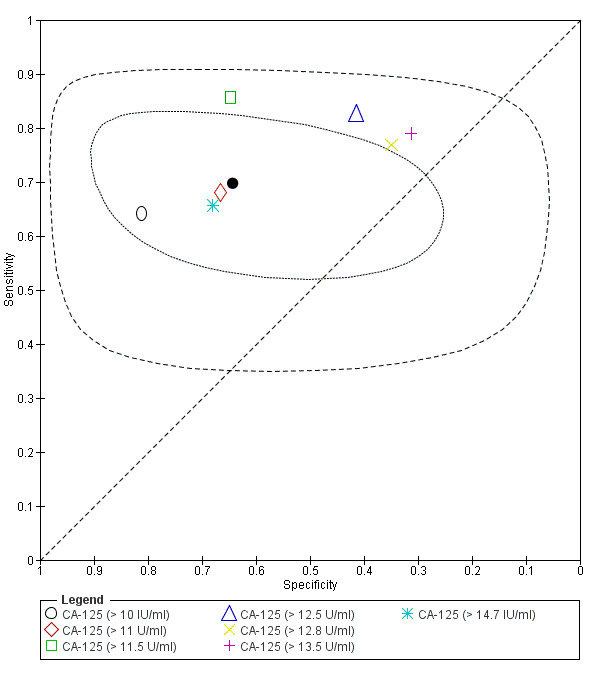

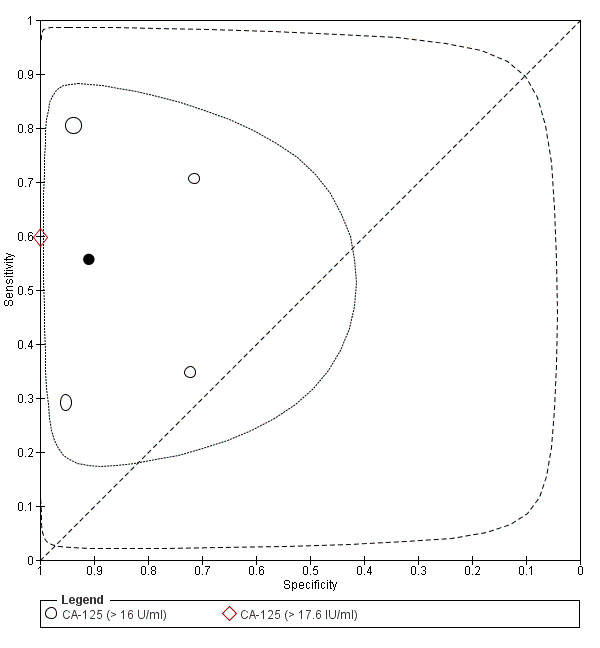

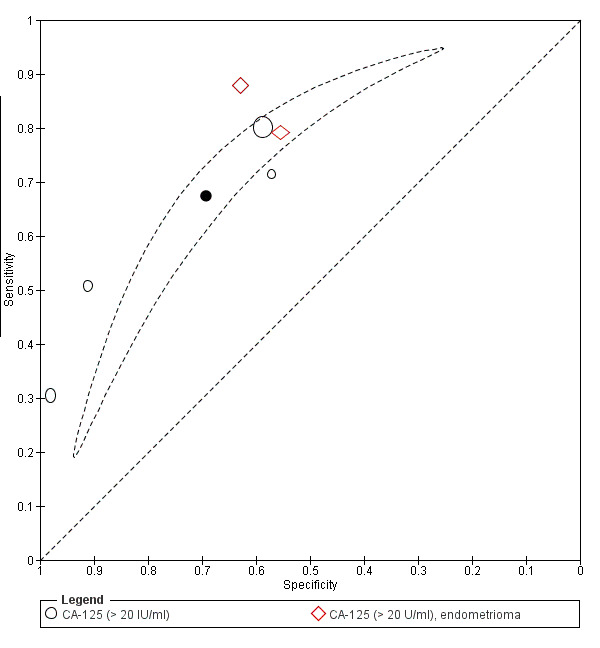

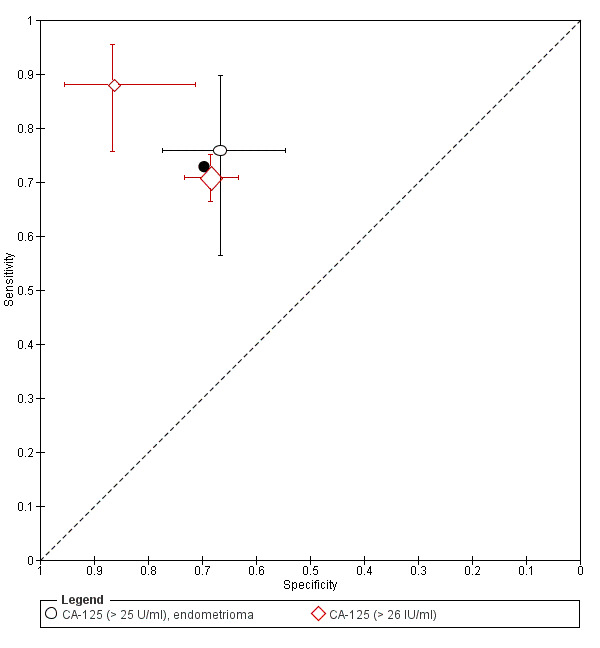

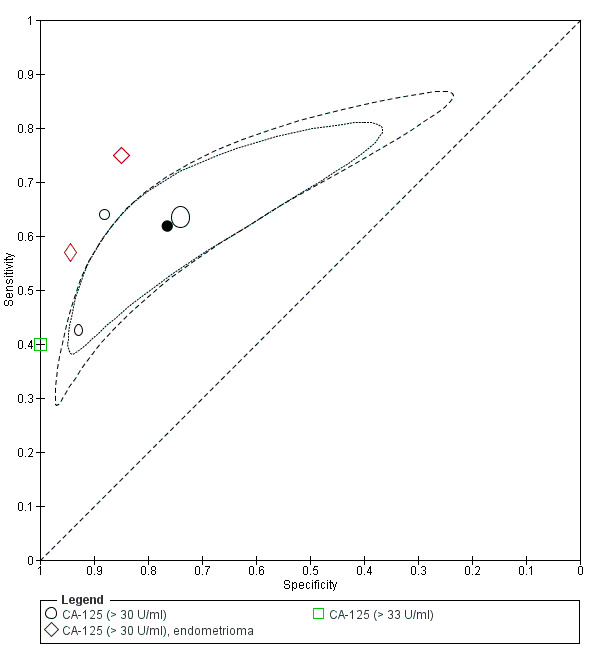

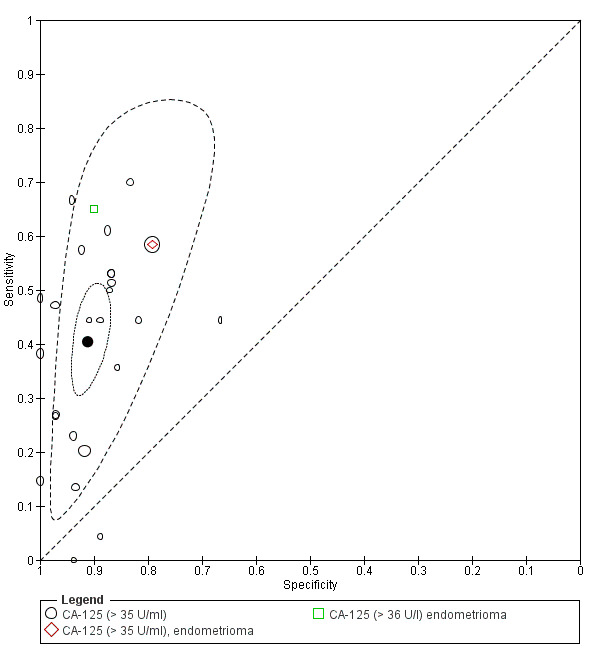

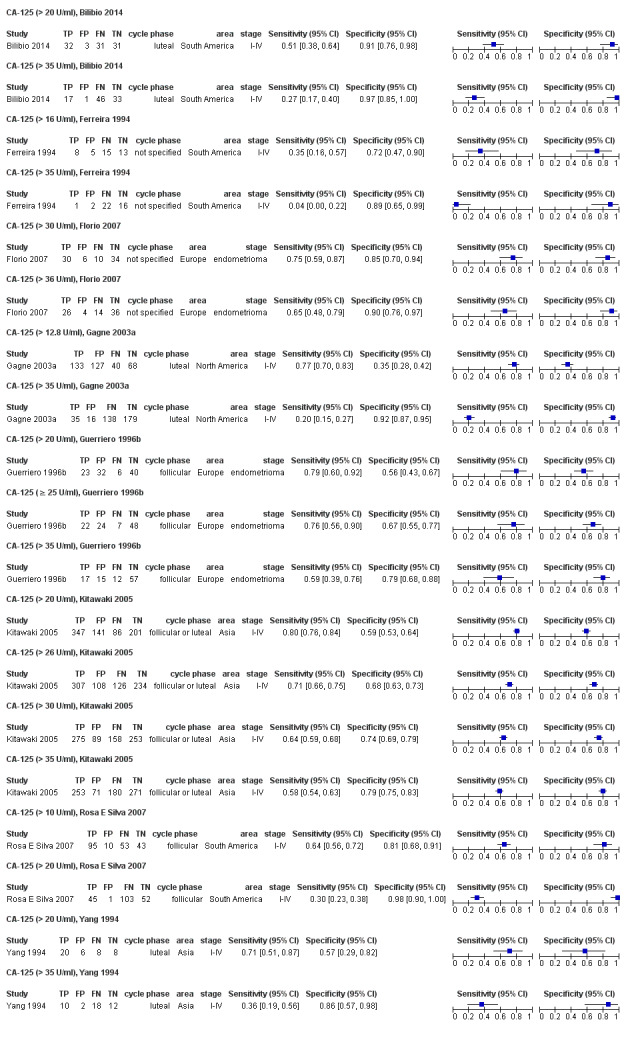

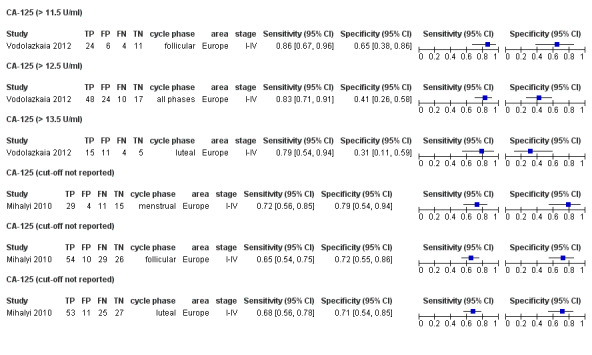

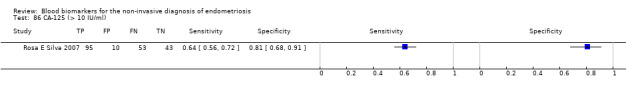

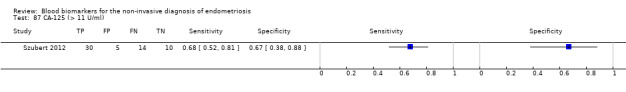

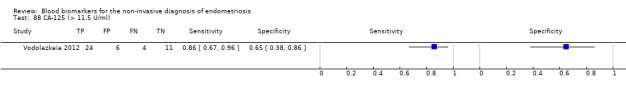

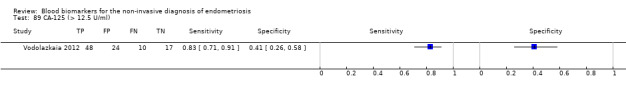

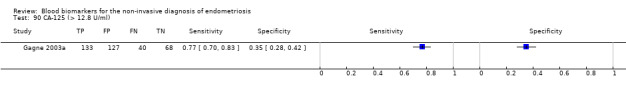

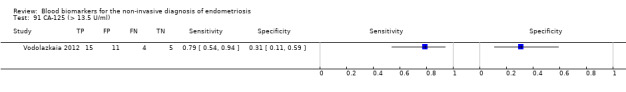

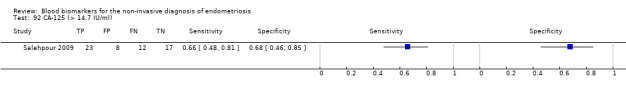

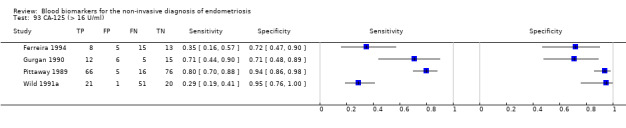

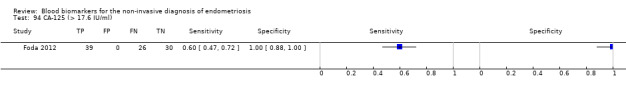

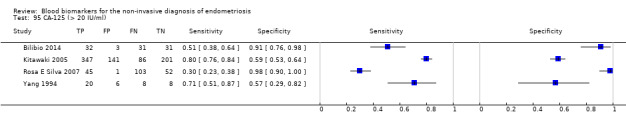

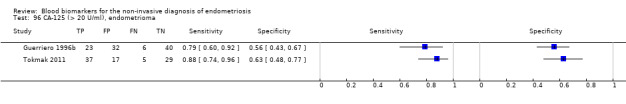

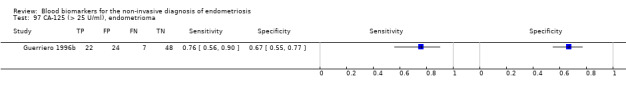

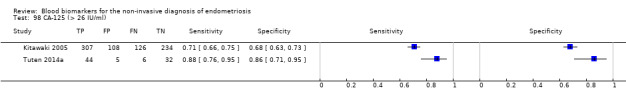

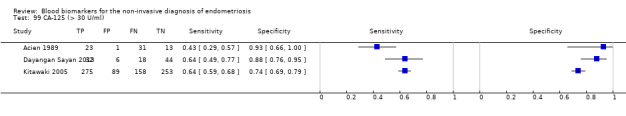

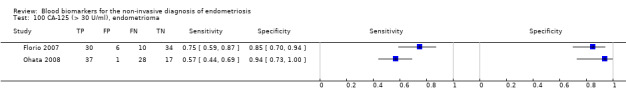

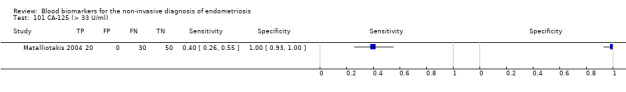

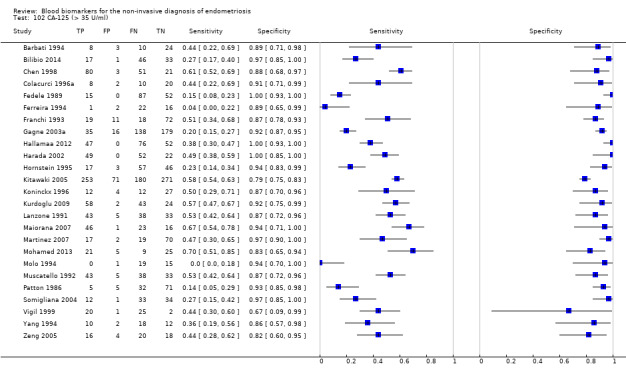

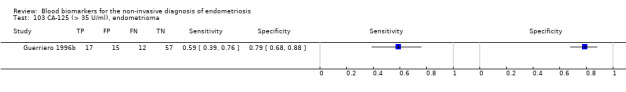

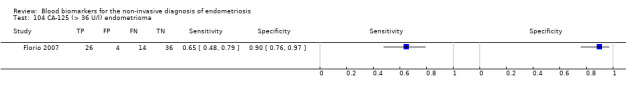

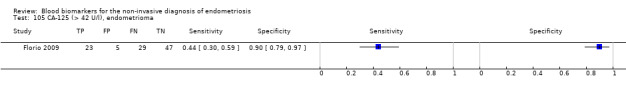

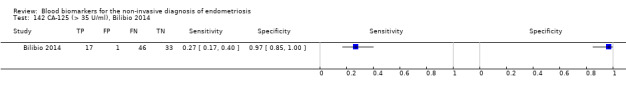

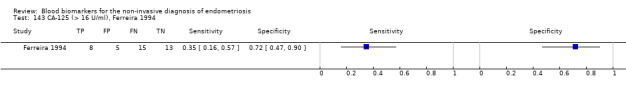

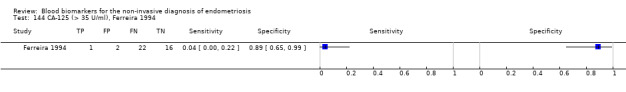

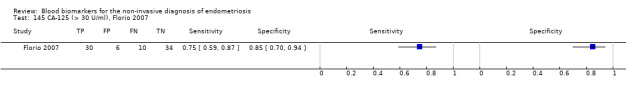

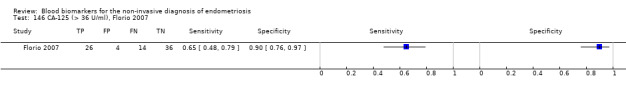

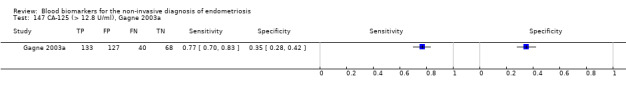

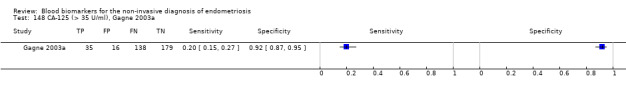

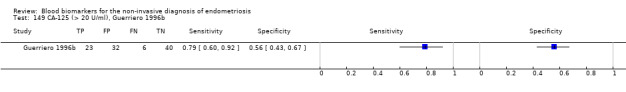

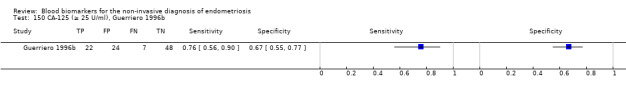

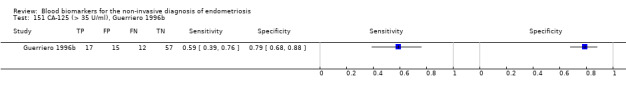

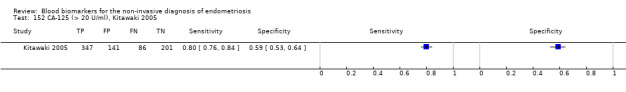

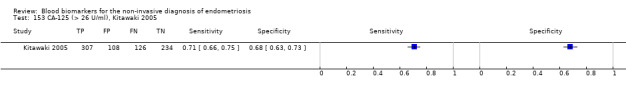

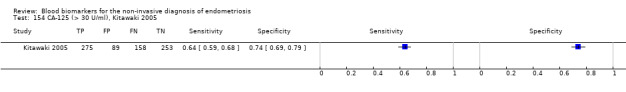

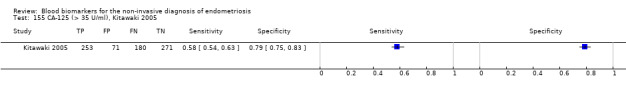

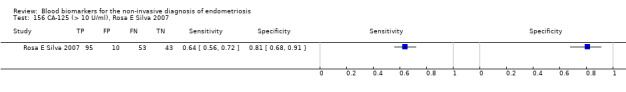

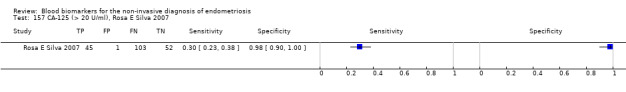

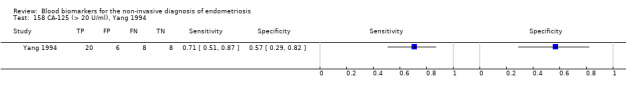

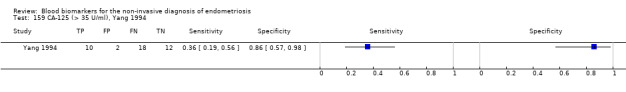

Studies assessed CA‐125 at different thresholds, demonstrating the following mean sensitivities and specificities: for cut‐off > 10.0 to 14.7 U/ml: 0.70 (95% CI 0.63 to 0.77) and 0.64 (95% CI 0.47 to 0.82); for cut‐off > 16.0 to 17.6 U/ml: 0.56 (95% CI 0.24, 0.88) and 0.91 (95% CI 0.75, 1.00); for cut‐off > 20.0 U/ml: 0.67 (95% CI 0.50 to 0.85) and 0.69 (95% CI 0.58 to 0.80); for cut‐off > 25.0 to 26.0 U/ml: 0.73 (95% CI 0.67 to 0.79) and 0.70 (95% CI 0.63 to 0.77); for cut‐off > 30.0 to 33.0 U/ml: 0.62 (95% CI 0.45 to 0.79) and 0.76 (95% CI 0.53 to 1.00); and for cut‐off > 35.0 to 36.0 U/ml: 0.40 (95% CI 0.32 to 0.49) and 0.91 (95% CI 0.88 to 0.94).

We could not statistically evaluate other biomarkers meaningfully, including biomarkers that were assessed for their ability to differentiate endometrioma from other benign ovarian cysts.

Eighty‐two studies evaluated 97 biomarkers that did not differentiate women with endometriosis from disease‐free controls. Of these, 22 biomarkers demonstrated conflicting results, with some studies showing differential expression and others no evidence of a difference between the endometriosis and control groups.

Authors' conclusions

Of the biomarkers that were subjected to meta‐analysis, none consistently met the criteria for a replacement or triage diagnostic test. A subset of blood biomarkers could prove useful either for detecting pelvic endometriosis or for differentiating ovarian endometrioma from other benign ovarian masses, but there was insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions. Overall, none of the biomarkers displayed enough accuracy to be used clinically outside a research setting. We also identified blood biomarkers that demonstrated no diagnostic value in endometriosis and recommend focusing research resources on evaluating other more clinically useful biomarkers.

Plain language summary

Blood biomarkers for the non‐invasive diagnosis of endometriosis

Review Question

How accurate are blood tests in detecting endometriosis? Can any blood test be accurate enough to replace or reduce the need for surgery in the diagnosis of endometriosis?

Background

Women with endometriosis have endometrial tissue (the tissue that lines the womb and is shed during menstruation) growing outside the womb within the pelvic cavity. This tissue responds to reproductive hormones, causing painful periods, chronic lower abdominal pain and difficulty conceiving. Currently, the only reliable way of diagnosing endometriosis is to perform keyhole surgery and visualise the endometrial deposits inside the abdomen. Because surgery is risky and expensive, we evaluated whether the results of blood tests (blood biomarkers) can help to detect endometriosis non‐invasively. An accurate blood test could lead to the diagnosis of endometriosis without the need for surgery, or it could reduce the need for diagnostic surgery to a group of women who were most likely to have endometriosis. Separate Cochrane reviews from this series evaluate other non‐invasive ways of diagnosing endometriosis using urine, imaging, endometrial and combination tests.

Study characteristics

The evidence included in this review is current to July 2015. We included 141 studies involving 15,141 participants. All studies evaluated reproductive‐aged women who were undertaking diagnostic surgery because they were suspected of having one or more of the following target conditions: ovarian, peritoneal or deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE). Cancer antigen‐125 (CA‐125) was the most common blood biomarker studied. Seventy studies evaluated 47 blood biomarkers that were expressed differently in women with and without endometriosis, and 82 studies identified 97 biomarkers that did not distinguish between the two groups. Twenty‐two biomarkers were in both categories.

Key results

Only four of the assessed biomarkers (anti‐endometrial Abs (anti‐endometrial autoantibodies), interleukin‐6 (IL‐6), CA‐19.9 and CA‐125) were evaluated by enough studies to provide a meaningful assessment of test accuracy. None of these tests was accurate enough to replace diagnostic surgery. Several studies identified biomarkers that might be of value in diagnosing endometriosis, but there are too few reports to be sure of their diagnostic benefit. Overall, there is not enough evidence to recommend testing for any blood biomarker in clinical practice to diagnose endometriosis.

Quality of the evidence

Generally, the reports were of low methodological quality, and most blood tests were only assessed by a single or a small number of studies. When the same biomarker was studied, there were significant differences in how studies were conducted, the group of women studied and the cut‐offs used to determine a positive result.

Future research

More high quality research trials are necessary to accurately assess the diagnostic potential of certain blood biomarkers, whose diagnostic value for endometriosis was suggested by a limited number of studies.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings'. 'Biomarkers evaluated as a diagnostic test for endometriosis.

| Review question | What is the diagnostic accuracy of the blood biomarkers in detecting pelvic endometriosis (peritoneal endometriosis, endometrioma, deep infiltrating endometriosis)? | ||||||

| Importance | A simple and reliable non‐invasive test for endometriosis with the potential to either replace laparoscopy or to triage patients in order to reduce surgery, would minimise surgical risk and reduce diagnostic delay | ||||||

| Patients | Reproductive aged women with suspected endometriosis or persistent ovarian mass, or women undergoing infertility work‐up or gynaecological laparoscopy | ||||||

| Settings | Hospitals (public or private of any level), outpatient clinics (general gynaecology, reproductive medicine, pelvic pain) or research laboratories | ||||||

| Reference standard | Visualisation of endometriosis at surgery (laparoscopy or laparotomy) with or without histological confirmation | ||||||

| Study design | Cross‐sectional of a single‐gate design (N = 25) or a two‐gate design (N = 44); unable to determine if single‐ or two‐gate design for 1 study; prospective enrolment; a single study could assess more than one test | ||||||

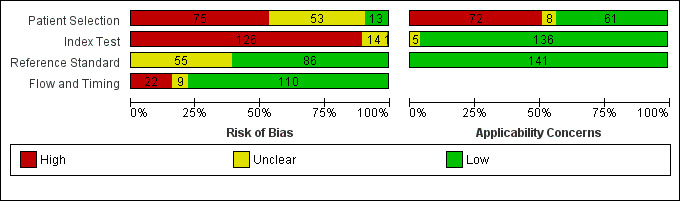

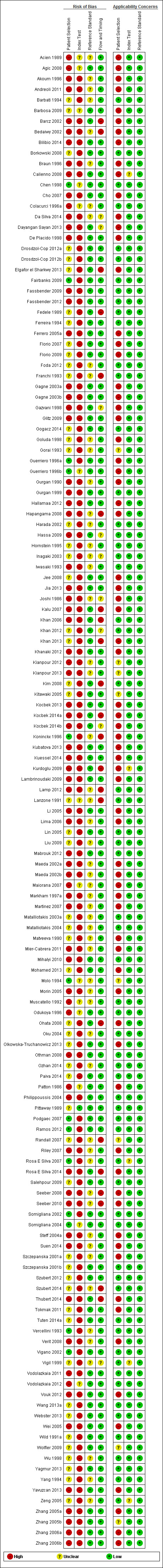

| Risk of bias | Overall judgement | Poor quality of most of the studies (no study had a 'low risk' assessment in all 4 domains) | |||||

| Patient selection bias | High risk: 31 studies; unclear risk: 32 studies; low risk: 7 studies | ||||||

| Index test interpretation bias | High risk: 56 studies; unclear risk: 12 studies; low risk: 2 studies | ||||||

| Reference standard interpretation bias | High risk: 0 studies; unclear risk: 30 studies; low risk: 40 studies | ||||||

| Flow and timing selection bias | High risk: 11 studies; unclear risk: 3 studies; low risk: 56 studies | ||||||

| Applicability concerns | Concerns regarding patient selection | High concern: 32 studies; unclear concern: 5 studies; low concern: 33 studies | |||||

| Concerns regarding index test | High concern: 0 studies; unclear concern: 4 studies; low concern: 66 studies | ||||||

| Concerns regarding reference standard | High concern: 0 studies; unclear concern: 0 studies; low concern: 70 studies | ||||||

| Diagnostic criteria | Replacement test: sensitivity ≥ 94 and specificity ≥ 79 SnOUT triage test: sensitivity ≥ 95 and specificity ≥ 50 SpIN triage test: sensitivity ≥ 50 and specificity ≥ 95 | ||||||

| Test | N participants (studies) | Outcomes | Diagnostic estimates (95% CI) | Implications | |||

|

True positives (endometriosis) |

False positives (incorrectly classified as endometriosis) | True negatives (disease‐free) |

False negatives (incorrectly classified as disease‐free) |

||||

| 1. Angiogenesis and growth factors and their receptors | |||||||

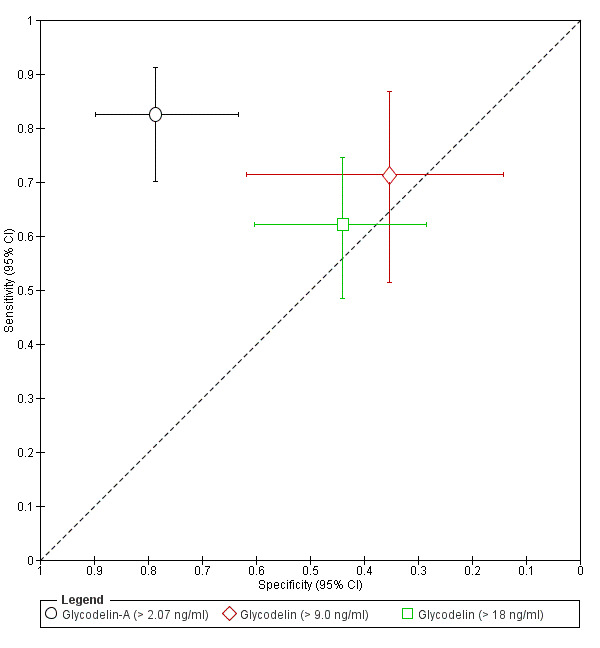

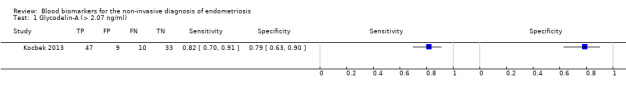

| Glycodelin‐A cut‐off threshold > 2.07 ng/ml follicular or luteal cycle phase rASRM stage I‐IVc |

99 (1) | 47 | 9 | 33 | 10 | Sens = 0.82 (0.70 to 0.91); spec = 0.79 (0.63 to 0.90) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

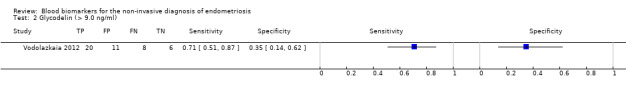

| Glycodelina# cut‐off threshold > 9.0 ng/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM stage I‐IVb |

45 (1) | 20 | 11 | 6 | 8 | Sens = 0.71 (0.51 to 0.87); spec = 0.35 (0.14 to 0.62) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

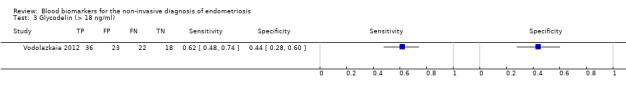

| Glycodelina# cut‐off threshold > 18 ng/ml any cycle phase rASRM stage I‐IVb |

99 (1) | 36 | 23 | 18 | 22 | Sens = 0.62 (0.48 to 0.74); spec = 0.44 (0.28 to 0.60) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

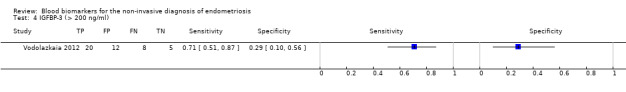

| IGFBP‐3 (insulin‐like growth factor‐binding protein‐3)a* cut‐off threshold > 200 ng/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM I‐IVb |

45 (1) | 20 | 12 | 5 | 8 | Sens = 0.71 (0.51 to 0.87); spec = 0.29 (0.10 to 0.56) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

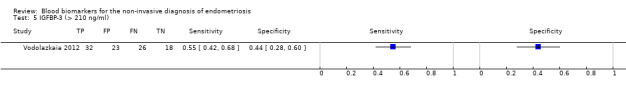

| IGFBP‐3 (insulin‐like growth factor‐binding protein‐3)a* cut‐off threshold > 210 ng/ml any cycle phase rASRM I‐IVb |

99 (1) | 32 | 23 | 18 | 26 | Sens = 0.55 (0.42 to 0.68); spec = 0.44 (0.28 to 0.60) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

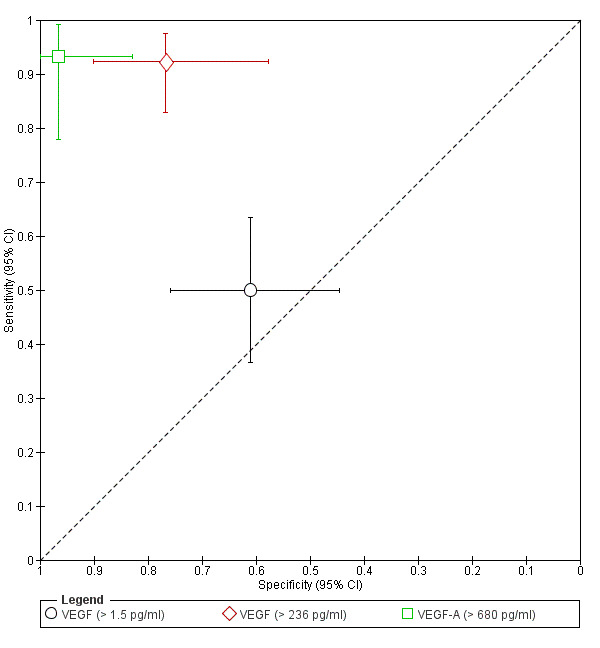

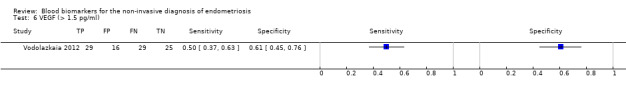

| VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) cut‐off threshold > 1.5 pg/ml any cycle phase rASRM I‐IVb |

99 (1) | 29 | 16 | 25 | 29 | Sens = 0.50 (0.37 to 0.63); spec = 0.61 (0.45 to 0.76) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

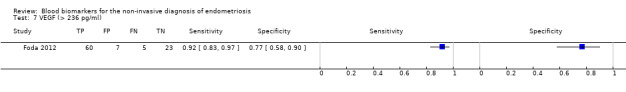

| VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) cut‐off threshold > 236 pg/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

95 (1) | 60 | 7 | 23 | 5 | Sens = 0.92 (0.83 to 0.97); spec = 0.77 (0.58 to 0.90) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; approaches the criteria for a replacement and SnOUT triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

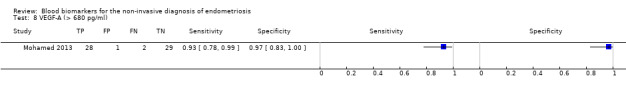

| VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) cut‐off threshold > 680 pg/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM III‐IV |

60 (1) | 28 | 1 | 29 | 2 | Sens = 0.93 (0.78 to 0.99); spec = 0.97 (0.83 to 1.00) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; meets criteria for a SpIN triage test and approaches criteria for a replacement test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

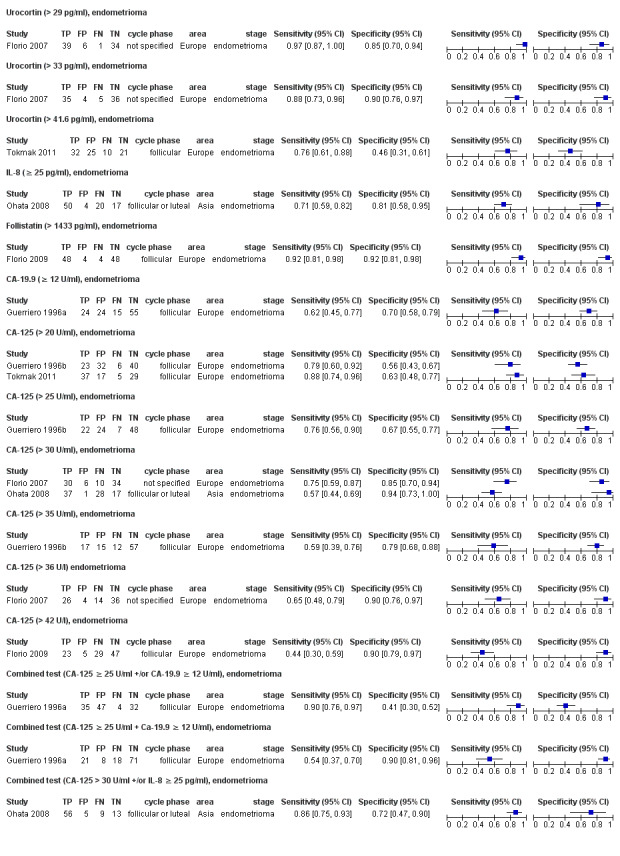

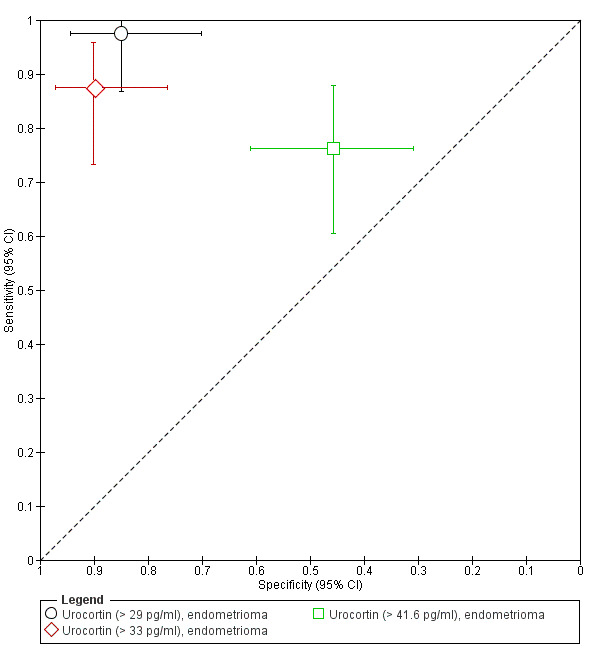

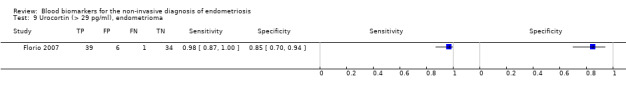

| Urocortina& cut‐off threshold > 29 pg/ml cycle phase not specified rASRM III‐IVd |

80 (1) | 39 | 6 | 34 | 1 | Sens = 0.97 (0.87 to 1.00); spec = 0.85 (0.70 to 0.94) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; meets criteria for a replacement and SnOUT triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

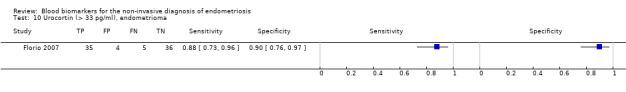

| Urocortina& cut‐off threshold > 33 pg/ml cycle phase not specified rASRM III‐IVd |

80 (1) | 35 | 4 | 36 | 5 | Sens = 0.88 (0.73 to 0.96); spec = 0.90 (0.76 to 0.97) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; approaches criteria for a SpIN triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

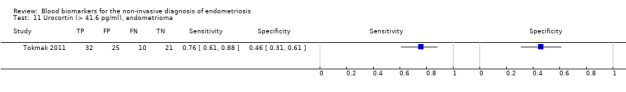

| Urocortin cut‐off threshold > 41.6 pg/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM III‐IVd |

88 (1) | 32 | 25 | 21 | 10 | Sens = 0.76 (0.61 to 0.88); spec = 0.46 (0.31 to 0.61) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

| 2. Apoptosis markers | |||||||

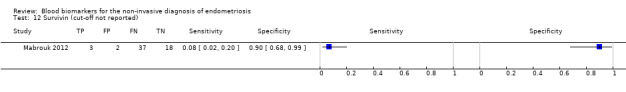

| Survivin cut‐off threshold not reported follicular cycle phase rASRM stage not reportede |

60 (1) | 3 | 2 | 18 | 37 | Sens = 0.07 (0.02 to 0.20); spec = 0.90 (0.68 to 0.99) | Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

| 3. Cell adhesion molecules and other matrix‐related proteins | |||||||

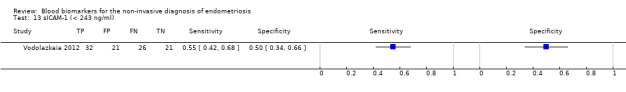

| sICAM‐1 (soluble form of intercellular‐adhesion molecule‐1)a# cut‐off threshold < 243 ng/ml any cycle phase rASRM I‐IVb |

99 (1) | 32 | 21 | 21 | 26 | Sens = 0.55 (0.42 to 0.68); spec = 0.50 (0.34 to 0.66) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

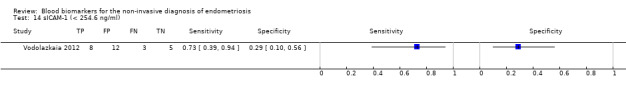

| sICAM‐1 (soluble form of intercellular‐adhesion molecule‐1)a# cut‐off threshold < 254.6 ng/ml menstrual cycle phase rASRM I‐IVb |

28 (1) | 8 | 12 | 5 | 3 | Sens = 0.73 (0.39 to 0.94); spec = 0.29 (0.10 to 0.56) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

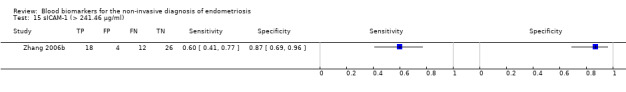

| sICAM‐1 (soluble form of intercellular‐adhesion molecule‐1) cut‐off threshold > 241.46 µg/ml cycle phase not specified rASRM I‐IV |

60 (1) | 18 | 4 | 26 | 12 | Sens = 0.60 (0.41 to 0.77); spec = 0.87 (0.69 to 0.96) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

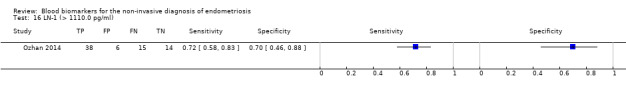

| LN‐1 (laminin‐1) cut‐off threshold > 1110.0 pg/ml cycle phase not specified rASRM II‐IV |

73 (1) | 38 | 6 | 14 | 15 | Sens = 0.72 (0.58 to 0.83); spec = 0.70 (0.46 to 0.88) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

| 4. High‐throughput molecular markers | |||||||

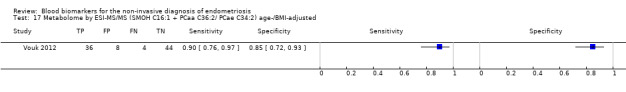

| Metabolome by ESI‐MS/MS (SMOH C16:1 + PCaa C36:2/ PCae C34:2) any cycle phase rASRM III‐IVe age/body mass index‐adjusted |

92 (1) | 36 | 8 | 44 | 4 | Sens = 0.90 (0.76 to 0.97); spec = 0.85 (0.72 to 0.93) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; approaches criteria of a replacement and SnOUT triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

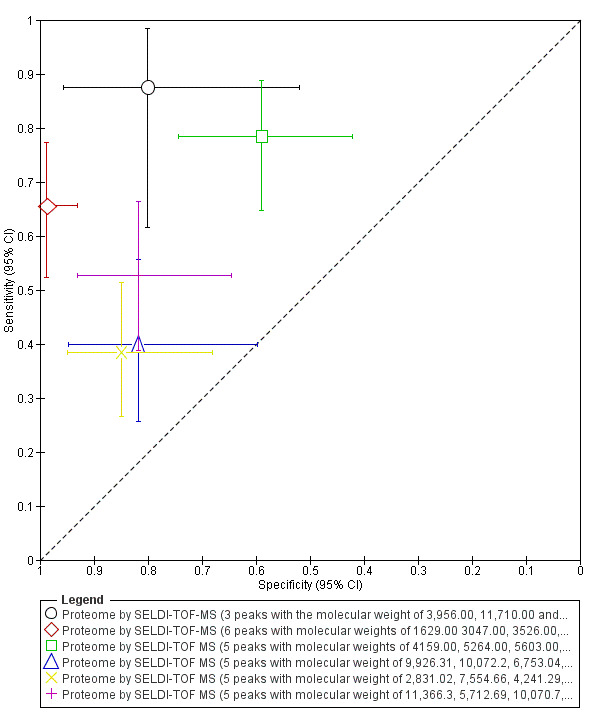

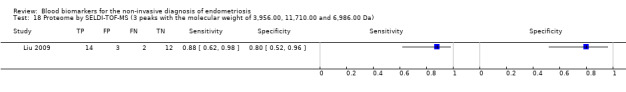

| Proteome by SELDI‐TOF‐MS (3 peaks with the MW 3956.00, 11,710.00 and 6986.00 Da) cycle phase not specified rASRM I‐IV |

31 (1) | 14 | 3 | 12 | 2 | Sens = 0.88 (0.62 to 0.98); spec = 0.80 (0.52 to 0.96) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; further diagnostic test accuracy studies using standardised methodology is recommended |

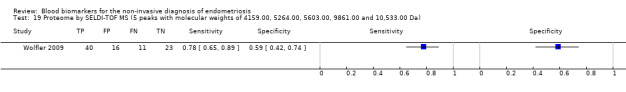

| Proteome by SELDI‐TOF MS (5 peaks with MW 4159.00, 5264.00, 5603.00, 9861.00 and 10,533.00 Da) follicular/ luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

90 (1) | 40 | 16 | 23 | 11 | Sens = 0.78 (0.65 to 0.89); spec = 0.59 (0.42 to 0.74) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; further diagnostic test accuracy studies using standardised methodology is recommended |

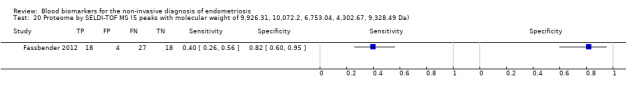

| Proteome by SELDI‐TOF MS (5 peaks with MW 9926.31, 10,072.2, 6753.04, 4302.67, 9328.49 Da) menstrual cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

67 (1) | 18 | 4 | 18 | 27 | Sens = 0.40 (0.26 to 0.56); spec = 0.82 (0.60 to 0.95) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; further diagnostic test accuracy studies using standardised methodology is recommended |

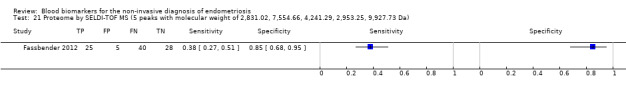

| Proteome by SELDI‐TOF MS (5 peaks with MW 2831.02, 7554.66, 4241.29, 2953.25, 9927.73 Da) follicular cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

98 (1) | 25 | 5 | 28 | 40 | Sens = 0.38 (0.27 to 0.51); spec = 0.85 (0.68 to 0.95) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; further diagnostic test accuracy studies using standardised methodology is recommended |

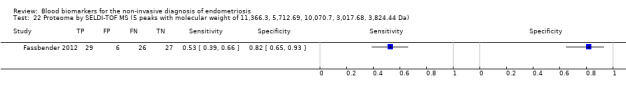

| Proteome by SELDI‐TOF MS (5 peaks with MW 11,366.3, 5712.69, 10,070.7, 3017.68, 3824.44 Da) luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

88 (1) | 29 | 6 | 27 | 26 | Sens = 0.53 (0.39to 0.66); spec = 0.82 (0.65 to 0.93) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; further diagnostic test accuracy studies using standardised methodology is recommended |

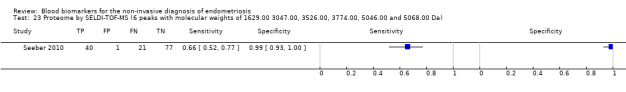

| Proteome by SELDI‐TOF‐MS (6 peaks with MW 1629, 3047, 3526, 3774, 5046 and 5068 Da) any cycle phase rASRM II‐IV |

139 (1) | 40 | 1 | 77 | 21 | Sens = 0.66 (0.52 to 0.77); spec = 0.99 (0.93 to 1.00) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; meets criteria for a SpIN triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies using standardised methodology is recommended |

| 5. Hormonal markers | |||||||

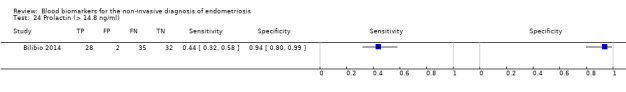

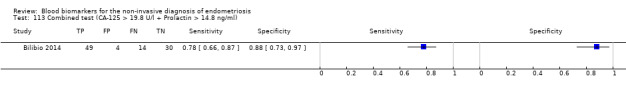

| Prolactin1a^ cut‐off threshold > 14.8 ng/ml luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IVc |

97 (1) | 28 | 2 | 32 | 35 | Sens = 0.44 (0.32 to 0.58); spec = 0.94 (0.80 to 0.99) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

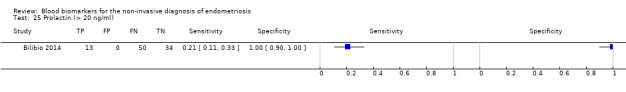

| Prolactin1a^ cut‐off threshold > 20 ng/ml luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IVc |

97 (1) | 13 | 0 | 34 | 50 | Sens = 0.21 (0.11 to 0.33); spec = 1.00 (0.90 to 1.00) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

| 6. Immune system and inflammatory markers | |||||||

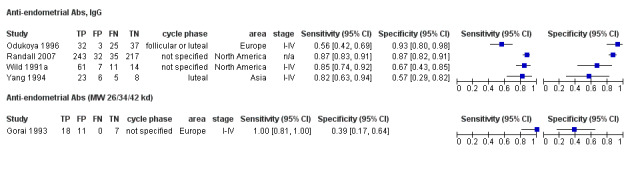

| Anti‐endometrial Abs cut‐off threshold ‐ definitions for positive result varied cycle phase varied (not specified in 2 studies) rASRM I‐IV in 3 studies; not reported in 1 study |

759 (4) | 359 | 48 | 276 | 76 | Sens = 0.81 (0.76 to 0.87); spec = 0.75 (0.46 to 1.00) |

Summary estimates did not meet the predetermined criteria for triage or replacement test; varying methodologies and populations across the studies |

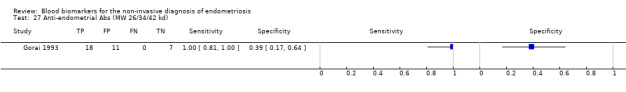

| Anti‐endometrial Abs (MW of 26/34/42 kd) cut‐off threshold: dark band in the blot for at least 1 Ab cycle phase not specified rASRM I‐IV |

36 (1) | 18 | 11 | 7 | 0 | Sens = 1.00 (0.81 to 1.00); spec = 0.39 (0.17 to 0.64) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

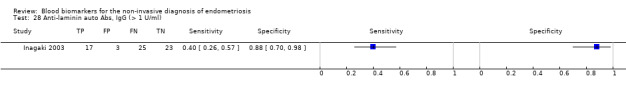

| Anti‐laminin auto Abs cut‐off threshold > 1 U/ml cycle phase not specified rASRM I‐IV |

68 (1) | 17 | 3 | 23 | 25 | Sens = 0.40 (0.26 to 0.57); spec = 0.88 (0.70 to 0.98) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

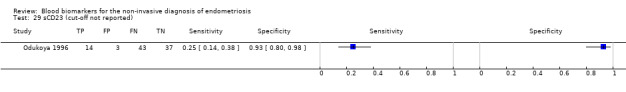

| sCD23 (soluble CD23) cut‐off threshold: absorbance value of ELISA > control mean ± 2SD (standard deviations) follicular or luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

97 (1) | 14 | 3 | 37 | 43 | Sens = 0.25 (0.14 to 0.38); spec = 0.93 (0.80 to 0.98) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

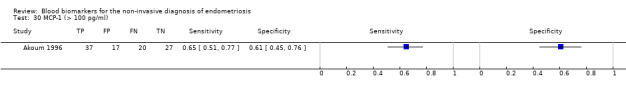

| MCP‐1 (monocyte chemotactic protein‐1) cut‐off threshold > 100 pg/ml menstrual cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

101 (1) | 37 | 17 | 27 | 20 | Sens = 0.65 (0.51 to 0.77); spec = 0.61 (0.45 to 0.76) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

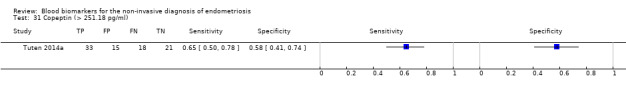

| Copeptin cut‐off threshold > 251.2 pg/ml cycle phase not specified rASRM I‐IV |

87 (1) | 33 | 15 | 21 | 18 | Sens = 0.65 (0.50 to 0.78); spec = 0.58 (0.41 to 0.74) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

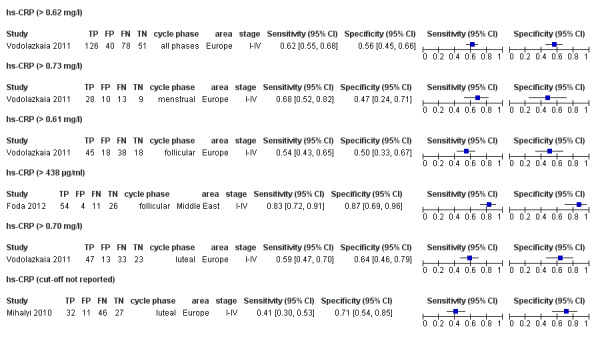

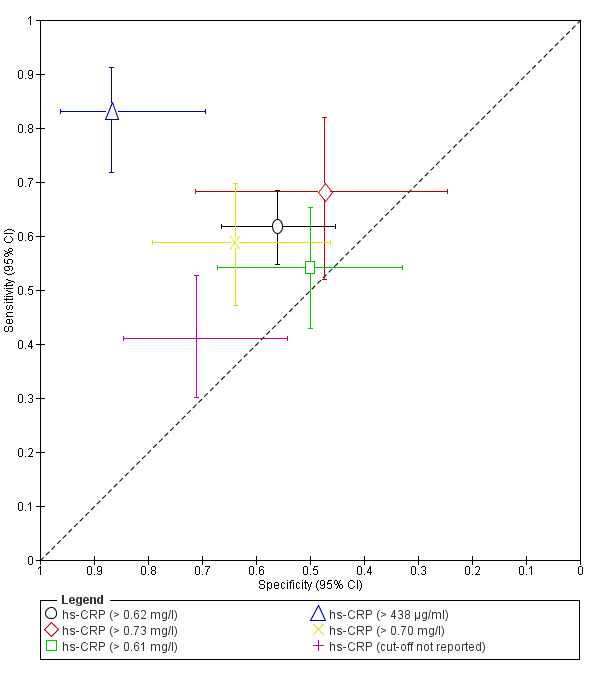

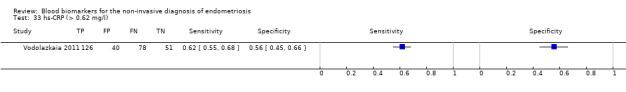

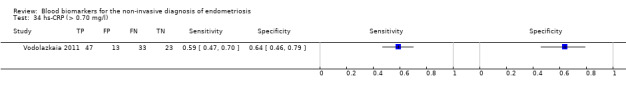

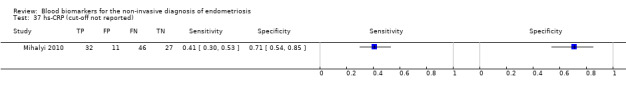

| hs‐CRP (high sensitive C‐reactive protein)a$ cut‐off threshold > 0.62 mg/l any cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

295 (1) | 126 | 40 | 51 | 78 | Sens = 0.62 (0.55 to 0.68); spec = 0.56 (0.45 to 0.66) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

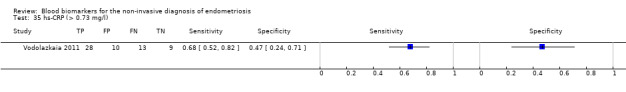

| hs‐CRP (high sensitive C‐reactive protein)a$ cut‐off threshold > 0.73 mg/l menstrual cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

60 (1) | 28 | 10 | 9 | 13 | Sens = 0.68 (0.52 to 0.82); spec = 0.47 (0.24 to 0.71) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

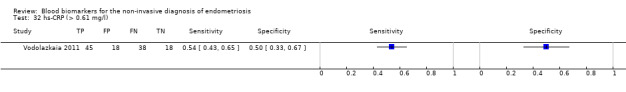

| hs‐CRP (high sensitive C‐reactive protein)a$ cut‐off threshold > 0.61 mg/l follicular cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

119 (1) | 45 | 18 | 18 | 38 | Sens = 0.54 (0.43 to 0.65); spec = 0.50 (0.33 to 0.67) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

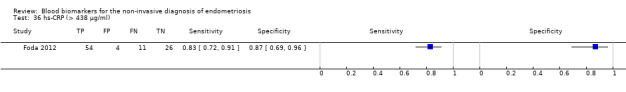

| hs‐CRP (high sensitive C‐reactive protein) cut‐off threshold >438 μg/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

95 (1) | 54 | 4 | 26 | 11 | Sens = 0.83 (0.72 to 0.91); spec = 0.87 (0.69 to 0.96) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

| hs‐CRP (high sensitive C‐reactive protein)a$ cut‐off threshold > 0.70 mg/l luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

116 (1) | 47 | 13 | 23 | 33 | Sens = 0.59 (0.47 to 0.70); spec = 0.64 (0.46 to 0.79) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

| hs‐CRP (high sensitive C‐reactive protein)a$ cut‐off threshold not specified luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

116 (1) | 32 | 11 | 27 | 46 | Sens = 0.41 (0.30 to 0.53); spec = 0.71 (0.54 to 0.85) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

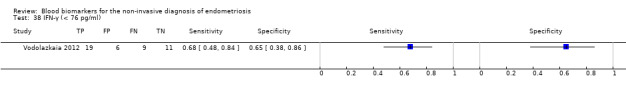

| IFN‐γ (interferon‐gamma) cut‐off threshold < 76 pg/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM I‐IVb |

45 (1) | 19 | 6 | 11 | 9 | Sens = 0.68 (0.48 to 0.84); spec = 0.65 (0.38 to 0.86) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

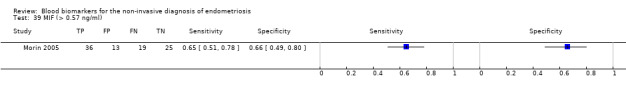

| MIF (macrophage migration inhibitory factor) cut‐off threshold > 0.57 ng/ml follicular or luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

93 (1) | 36 | 13 | 25 | 19 | Sens = 0.65 (0.51 to 0.78); spec = 0.66 (0.49 to 0.80) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

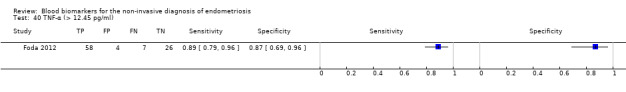

| TNF‐α (tumour necrosis factor alpha) cut‐off threshold >12.45 pg/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

95 (1) | 58 | 4 | 26 | 7 | Sens = 0.89 (0.79 to 0.96); spec = 0.87 (0.69 to 0.96) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

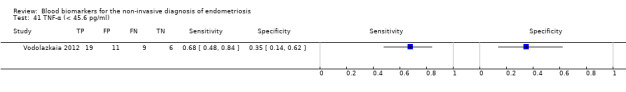

| TNF‐α (tumour necrosis factor alpha) cut‐off threshold < 45.6 pg/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM I‐IVb |

45 (1) | 19 | 11 | 6 | 9 | Sens = 0.68 (0.48 to 0.84); spec = 0.35 (0.14 to 0.62) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

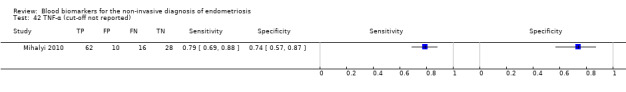

| TNF‐α (tumour necrosis factor alpha) cut‐off threshold not reported luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

116 (1) | 62 | 10 | 28 | 16 | Sens = 0.79 (0.69 to 0.88); spec = 0.74 (0.57 to 0.87) | Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

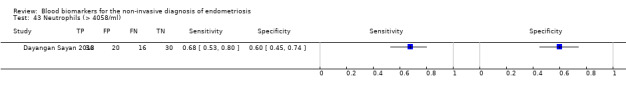

| Neutrophils cut‐off threshold > 4058 cells/ml menstrual cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

100 (1) | 34 | 20 | 30 | 16 | Sens = 0.68 (0.53 to 0.80); spec = 0.60 (0.45 to 0.74) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

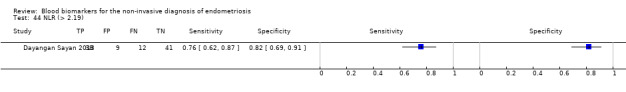

| NLR (neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio) cut‐off threshold > 2.19 menstrual cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

100 (1) | 38 | 9 | 41 | 12 | Sens = 0.76 (0.62 to 0.87); spec = 0.82 (0.69 to 0.91) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

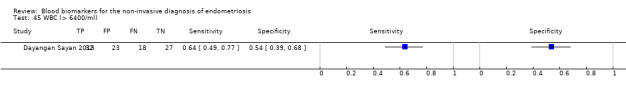

| WBC (white blood cells) cut‐off threshold > 6400 cells/ml menstrual cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

100 (1) | 32 | 23 | 27 | 18 | Sens = 0.64 (0.49 to 0.77); spec = 0.54 (0.39 to 0.68) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

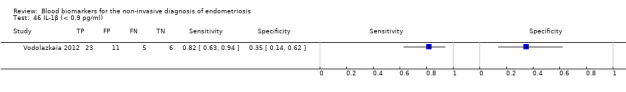

| IL‐1β (interleukin ‐ 1beta) cut‐off threshold < 0.9 pg/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM I‐IVb |

45 (1) | 23 | 11 | 6 | 5 | Sens = 0.82 (0.63 to 0.94); spec = 0.35 (0.14 to 0.62) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

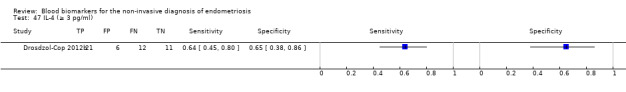

| IL‐4 (interleukin ‐ 4) cut‐off threshold ≥ 3 pg/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

50 (1) | 21 | 6 | 11 | 12 | Sens = 0.64 (0.45 to 0.80); spec = 0.65 (0.38 to 0.86) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

| IL‐6 (interleukin ‐ 6)a$ cut‐off threshold > 1.03 pg/ml follicular or luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

138 (1) | 55 | 34 | 36 | 13 | Sens = 0.81 (0.70 to 0.89); spec = 0.51 (0.39 to 0.64) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

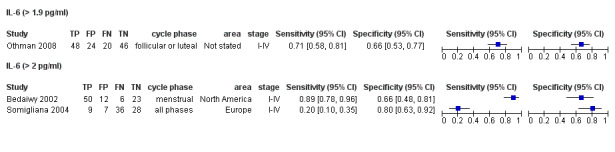

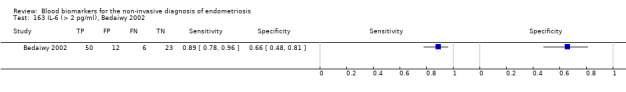

| IL‐6 (interleukin ‐ 6)a$, a^ cut‐off threshold > 1.9‐2.0 pg/ml cycle phase varied rASRM I‐IV |

309 (3) | 107 | 43 | 97 | 62 | Sens = 0.63 (0.52 to 0.75); spec = 0.69 (0.57 to 0.82) |

Summary estimates did not meet the predetermined criteria for a triage or replacement test; varying cycle phase across the studies |

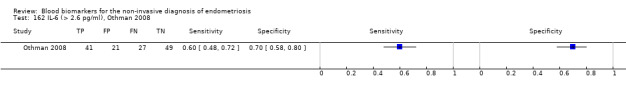

| IL‐6 (interleukin ‐ 6)a$ cut‐off threshold > 2.6 pg/ml follicular or luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

138 (1) | 41 | 21 | 49 | 27 | Sens = 0.60 (0.48 to 0.72); spec = 0.70 (0.58 to 0.80) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

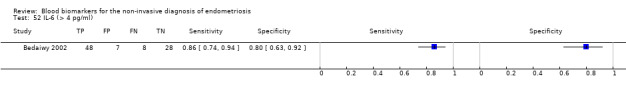

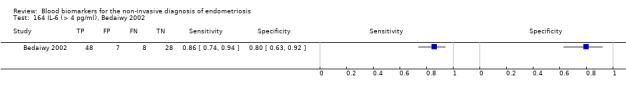

| IL‐6 (interleukin ‐ 6)a^ cut‐off threshold > 4 pg/ml menstrual cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

91 (1) | 48 | 7 | 28 | 8 | Sens = 0.86 (0.74 to 0.94); spec = 0.80 (0.63 to 0.92) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

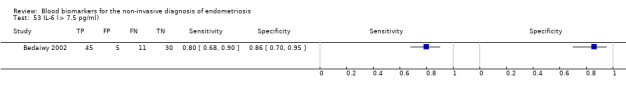

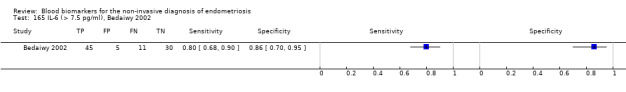

| IL‐6 (interleukin ‐ 6)a^ cut‐off threshold > 7.5 pg/ml menstrual cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

91 (1) | 45 | 5 | 30 | 11 | Sens = 0.80 (0.68 to 0.90); spec = 0.86 (0.70 to 0.95) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

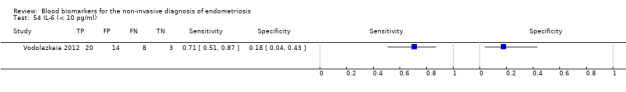

| IL‐6 (interleukin ‐ 6) cut‐off threshold < 10 pg/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM I‐IVb |

45 (1) | 20 | 14 | 3 | 8 | Sens = 0.71 (0.51 to 0.87); spec = 0.18 (0.04 to 0.43) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

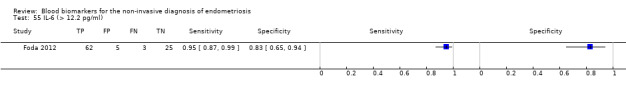

| IL‐6 (interleukin ‐ 6) cut‐off threshold > 12.2 pg/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

95 (1) | 62 | 5 | 25 | 3 | Sens = 0.95 (0.87 to 0.99); spec = 0.83 (0.65 to 0.94) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; meets criteria for a replacement and SnOUT triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

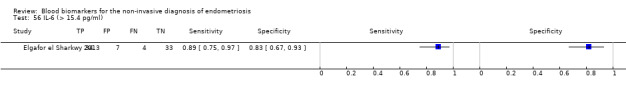

| IL‐6 (interleukin ‐ 6) cut‐off threshold > 15.4 pg/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM I‐II |

78 (1) | 34 | 7 | 33 | 4 | Sens = 0.89 (0.75 to 0.97); spec = 0.82 (0.67 to 0.93) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

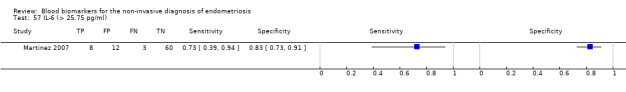

| IL‐6 (interleukin ‐ 6) cut‐off threshold > 25.75 pg/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM I‐II |

84 (1) | 8 | 12 | 60 | 3 | Sens = 0.73 (0.39 to 0.94); spec = 0.83 (0.73 to 0.91) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

| IL‐6 (interleukin ‐ 6) cut‐off threshold not specified luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

116 (1) | 46 | 9 | 29 | 32 | Sens = 0.59 (0.47 to 0.70); spec = 0.76 (0.60 to 0.89) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

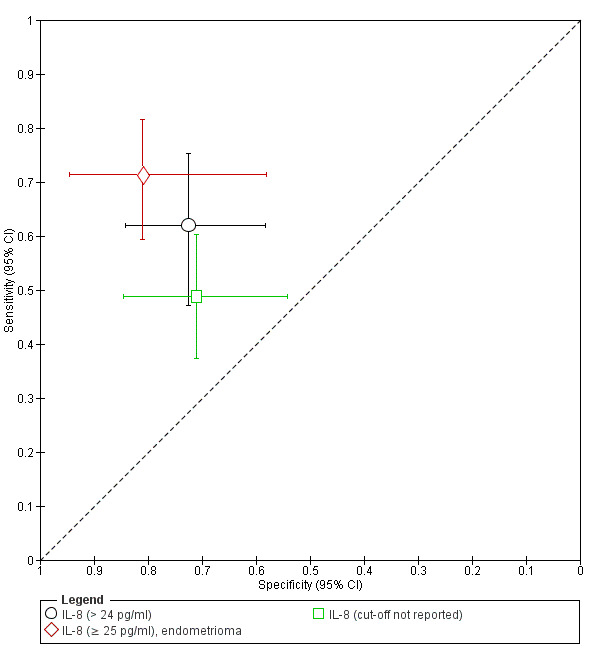

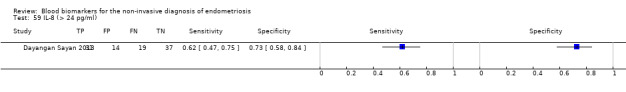

| IL‐8 (interleukin ‐ 8) cut‐off threshold > 24 pg/ml menstrual cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

101 (1) | 31 | 14 | 37 | 19 | Sens = 0.76 (0.60 to 0.89); spec = 0.73 (0.58 to 0.84) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

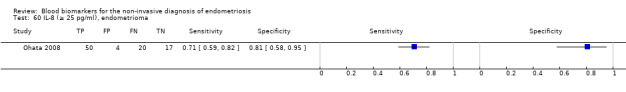

| IL‐8 (interleukin ‐ 8) cut‐off threshold > 25 pg/ml follicular or luteal cycle phase rASRM III‐IVd |

91 (1) | 50 | 4 | 17 | 20 | Sens = 0.71 (0.59 to 0.82); spec = 0.81 (0.58 to 0.95) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

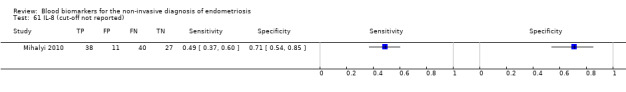

| IL‐8 (interleukin ‐ 8) cut‐off threshold not specified luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

116 (1) | 38 | 11 | 27 | 40 | Sens = 0.49 (0.37 to 0.60); spec = 0.71 (0.54 to 0.85) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

| 7. Other peptides and proteins shown to influence key events implicated in endometriosis | |||||||

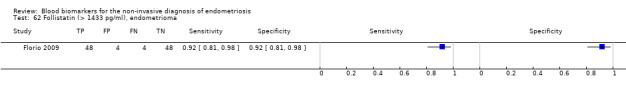

| Follistatin cut‐off threshold > 1433 pg/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM III‐IVd |

104 (1) | 48 | 4 | 48 | 4 | Sens = 0.92 (0.81 to 0.98); spec = 0.92 (0.81 to 0.98) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; approaches criteria for a replacement and SnOUT or SpIN triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

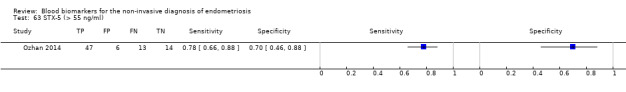

| STX‐5 (syntaxin ‐ 5) cut‐off threshold > 55 ng/ml cycle phase not specified rASRM I‐IV |

80 (1) | 47 | 6 | 14 | 13 | Sens = 0.78 (0.66 to 0.88); spec = 0.70 (0.46 to 0.88) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

| 8. Oxidative stress markers | |||||||

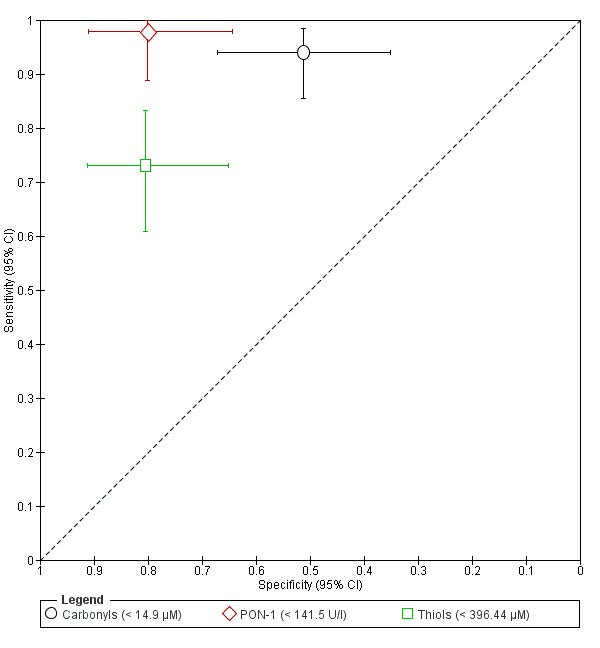

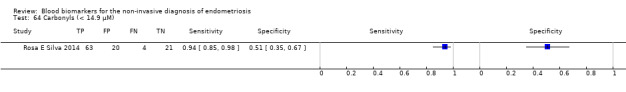

| Carbonyls cut‐off threshold < 14.9 μM cycle phase not specified rASRM stage not reported |

108 (1) | 63 | 20 | 21 | 4 | Sens = 0.94 (0.85 to 0.98); spec = 0.51 (0.35 to 0.67) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; approaches criteria for a SnOUT triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

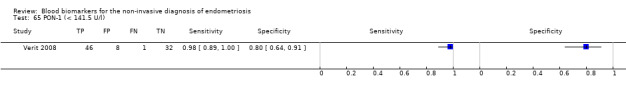

| PON‐1 (paraoxonase‐1) cut‐off threshold < 141.5 U/l follicular cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

87 (1) | 46 | 8 | 32 | 1 | Sens = 0.98 (0.89 to 1.00); spec = 0.80 (0.64 to 0.91) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; meets criteria for a replacement or SnOUT triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

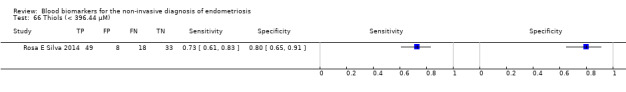

| Thiols cut‐off threshold < 396.44 μM cycle phase not specified rASRM stage not reported |

108 (1) | 49 | 8 | 33 | 18 | Sens = 0.73 (0.61 to 0.83); spec = 0.80 (0.65 to 0.91) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

| 9. Post‐transcriptional regulators of gene expression (microRNAs) | |||||||

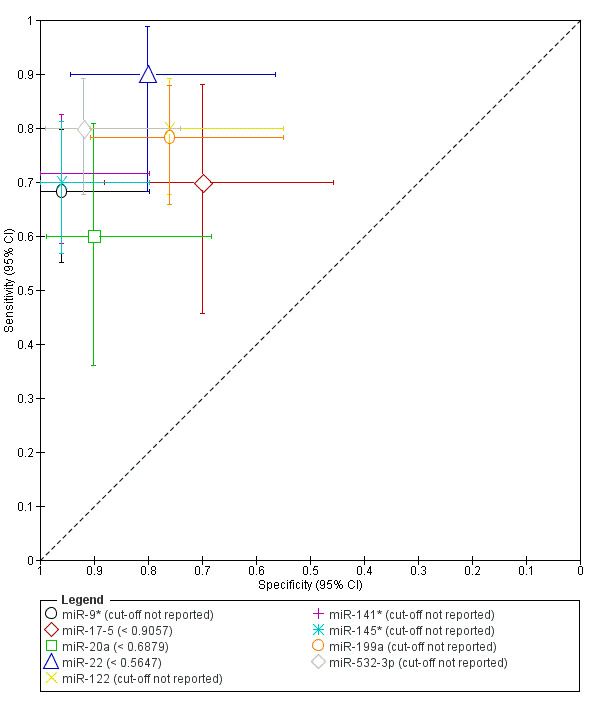

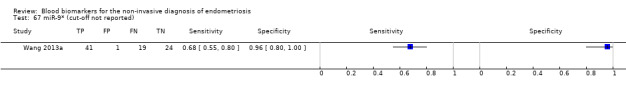

| miR‐9* cut‐off threshold not specified follicular or luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

85 (1) | 41 | 1 | 24 | 19 | Sens = 0.68 (0.55 to 0.80); spec = 0.96 (0.80 to 1.00) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; meets criteria for a SpIN triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

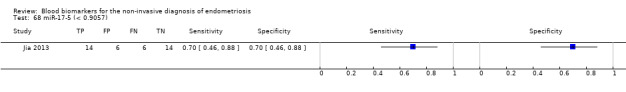

| miR‐17‐5 cut‐off threshold < 0.9057 follicular or luteal cycle phase rASRM III‐IV |

40 (1) | 14 | 6 | 14 | 6 | Sens = 0.70 (0.46 to 0.88); spec = 0.70 (0.46 to 0.88) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

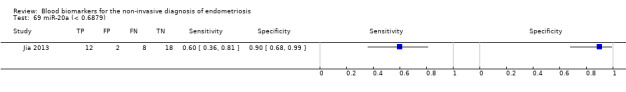

| miR‐20a cut‐off threshold < 0.6879 follicular or luteal cycle phase rASRM III‐IV |

40 (1) | 12 | 2 | 18 | 8 | Sens = 0.60 (0.36 to 0.81); spec = 0.90 (0.68 to 0.99) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; approaches criteria for a SpIN triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

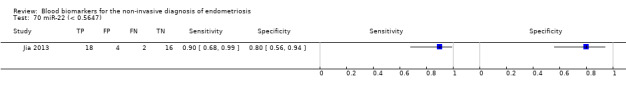

| miR‐22 cut‐off threshold < 0.5647 follicular or luteal cycle phase rASRM III‐IV |

40 (1) | 18 | 4 | 16 | 2 | Sens = 0.90 (0.68 to 0.99); spec = 0.80 (0.56 to 0.94) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; approaches criteria for a replacement or SnOUT triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

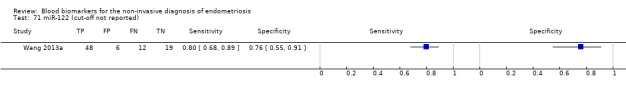

| miR‐122 cut‐off threshold not specified follicular or luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

85 (1) | 48 | 6 | 19 | 12 | Sens = 0.80 (0.68 to 0.89); spec = 0.76 (0.55 to 0.91) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

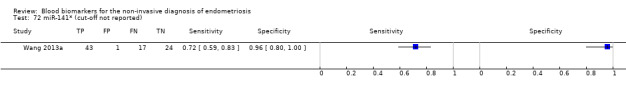

| miR‐141* cut‐off threshold not specified follicular or luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

85 (1) | 43 | 1 | 24 | 17 | Sens = 0.72 (0.59 to 0.83); spec = 0.96 (0.80 to 1.00) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; meets criteria for a SpIN triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

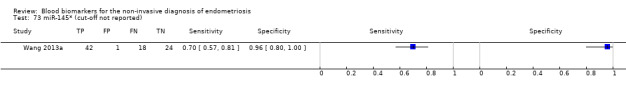

| miR‐145* cut‐off threshold not specified follicular or luteal cycle phase rASRM stage not reported |

85 (1) | 42 | 1 | 24 | 18 | Sens = 0.70 (0.57 to 0.81); spec = 0.96 (0.80 to 1.00) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; meets criteria for a SpIN triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

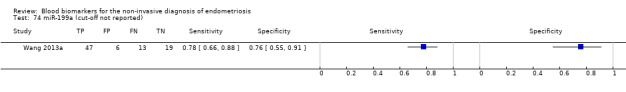

| miR‐199a cut‐off threshold not specified follicular or luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

85 (1) | 47 | 6 | 19 | 13 | Sens = 0.78 (0.66 to 0.88); spec = 0.76 (0.55 to 0.91) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

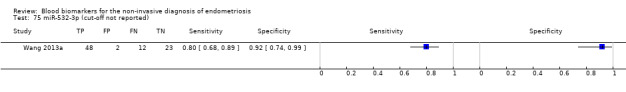

| miR‐532‐3p cut‐off threshold not specified follicular or luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

85 (1) | 48 | 2 | 23 | 12 | Sens = 0.80 (0.68 to 0.89); spec = 0.92 (0.74 to 0.99) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; approaches criteria for a SpIN triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

| 10. Tumour markers | |||||||

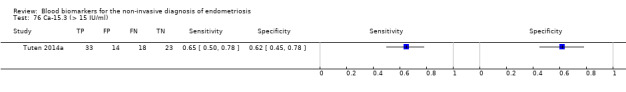

| CA‐15.3 (cancer antigen‐15.3) cut‐off threshold > 15.04 U/ml cycle phase not specified rASRM I‐IV |

88 (1) | 33 | 14 | 23 | 18 | Sens = 0.65 (0.50 to 0.78); spec = 0.62 (0.45 to 0.78) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

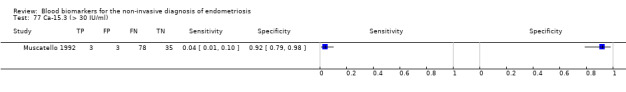

| CA‐15.3 (cancer antigen‐15.3) cut‐off threshold > 30 U/ml luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

119 (1) | 3 | 3 | 35 | 78 | Sens = 0.04 (0.01 to 0.10); spec = 0.92 (0.79 to 0.98) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

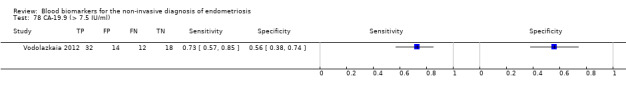

| CA‐19.9 (cancer antigen‐19.9)a# cut‐off threshold > 7.5 IU/ml luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IVb |

76 (1) | 32 | 14 | 18 | 12 | Sens = 0.73 (0.57 to 0.85); spec = 0.56 (0.38 to 0.74) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

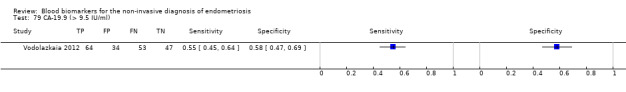

| CA‐19.9 (cancer antigen‐19.9)a# cut‐off threshold >9.5 IU/ml any cycle phase rASRM I‐IVb |

198 (1) | 64 | 34 | 47 | 53 | Sens = 0.55 (0.45 to 0.64); spec = 0.58 (0.47 to 0.69) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

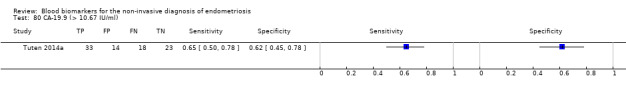

| CA‐19.9 (cancer antigen‐19.9) cut‐off threshold > 10.67 IU/ml cycle phase not specified rASRM I‐IV |

88 (1) | 33 | 14 | 23 | 18 | Sens = 0.65 (0.50 to 0.78); spec = 0.62 (0.45 to 0.78) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

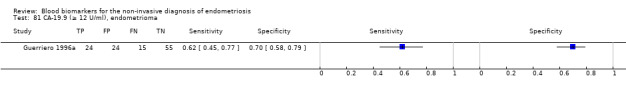

| CA‐19.9 (cancer antigen‐19.9) cut‐off threshold ≥ 12 IU/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM III‐IVd |

119 (1) | 24 | 24 | 55 | 15 | Sens = 0.62 (0.45 to 0.77); spec = 0.70 (0.58 to 0.79) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

| 42.5. CA‐19.9 (cancer antigen‐19.9) cut‐off threshold > 37 IU/ml cycle phase varied (not specified in 2 studies) rASRM I‐IV |

330 (3) | 88 | 11 | 72 | 159 | Summary estimates: Sens = 0.36 (0.26 to 0.45); spec = 0.87 (0.75 to 0.99) |

Summary estimates did not meet the predetermined criteria for a triage or replacement test; varying cycle phase across the studies |

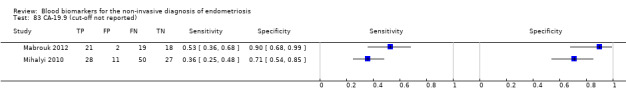

| CA‐19.9 (cancer antigen‐19.9)a# cut‐off threshold not specified follicular cycle phase rASRM stage not reportedd,e ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

60 (1) ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 116 (1) |

21 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 28 |

2 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 11 |

18 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 27 |

19 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 50 |

Sens = 0.53 (0.36 to 0.68); spec = 0.90 (0.68 to 0.99) ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ Sens = 0.36 (0.25 to 0.48); spec = 0.71 (0.54 to 0.85) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; varying populations across the studies; unclear thresholds |

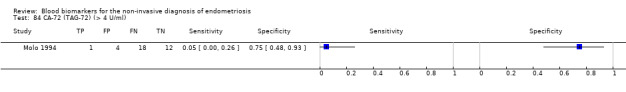

| CA‐72 (TAG‐72) (cancer antigen‐72 or tumour associated glycoprotein‐72) cut‐off threshold > 4 U/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM stage not reported |

35 (1) | 1 | 4 | 12 | 18 | Sens = 0.05 (0.00 to 0.26); spec = 0.75 (0.48 to 0.93) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

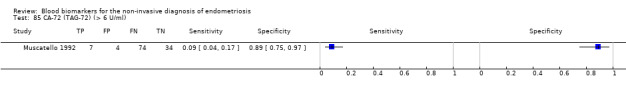

| CA‐72 (TAG‐72) (cancer antigen‐72 or tumour associated glycoprotein‐72) cut‐off threshold > 6 U/ml luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV |

119 (1) | 7 | 4 | 34 | 74 | Sens = 0.09 (0.04 to 0.17); spec = 0.89 (0.75 to 0.97) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

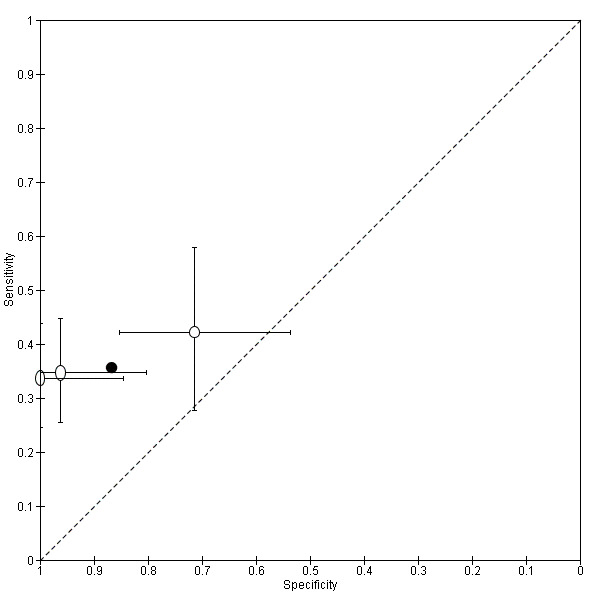

| CA‐125 (cancer antigen‐125)a!, a%, a* cut‐off threshold > 10‐14.7 U/ml cycle phase varied rASRM stage varied 2 evaluations excluded as overlapping populations (CA‐125 cut‐off > 11.5 U/ml and cut‐off > 13.5 U/ml, Vodolazkaia 2012) |

733 (5) | 329 | 174 | 155 | 129 | Summary estimates: Sens = 0.70 (0.63 to 0.77); spec = 0.64 (0.47 to 0.82) |

Summary estimates do not meet the predetermined criteria for a triage or replacement test |

| CA‐125 (cancer antigen‐125)a! cut‐off threshold > 11.5 U/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM I‐IVb (excluded from the above group as overlapping evaluation) |

45 (1) | 24 | 6 | 11 | 4 | Sens = 0.86 (0.67 to 0.96); spec = 0.65 (0.38 to 0.86) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

| CA‐125 (cancer antigen‐125) a! cut‐off threshold > 13.5 U/ml luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IVb (excluded from the above group as overlapping evaluation) |

35 (1) | 15 | 11 | 5 | 4 | Sens = 0.79 (0.54 to 0.94); spec = 0.31 (0.11 to 0.59) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

| CA‐125 (cancer antigen‐125)a# cut‐off value > 16‐17.6 U/ml cycle phase varied (not specified in 2 studies) rASRM stage varied (I in 1 study, I‐IV in 4 studies) |

430 (5) | 146 | 17 | 154 | 113 | Summary estimates: Sens = 0.56 (0.24 to 0.88); spec = 0.91 (0.75 to 1.00) |

Summary estimates approach the criteria for a SpIN triage test; varying populations across the studies |

| CA‐125 (cancer antigen‐125)a@, a^, a&, a*, a!! cut‐off value > 20 IU/ml cycle phase varied rASRM stage varied (1 studyc, 2 studiesd) |

1304 (6) | 504 | 200 | 361 | 239 | Summary estimates: Sens = 0.67 (0.50 to 0.85); spec = 0.69 (0.58 to 0.80) |

Summary estimates do not meet the predetermined criteria for a triage or replacement test; varying populations across the studies |

| CA‐125 (cancer antigen‐125)a^, a& cut‐off value > 25‐26 U/ml cycle phase varied; not specified in 1 study rASRM stage varied (1 studyd) |

963 (3) | 373 | 137 | 314 | 139 | Summary estimates: Sens = 0.73 (0.67 to 0.79); spec = 0.70 (0.63 to 0.77) |

Summary estimates do not meet the predetermined criteria for a triage or replacement test; varying populations across the studies |

| CA‐125 (cancer antigen‐125)a$, a& cut‐off value > 30‐33 U/ml (1 study > 33 U/ml) cycle phase varied (not specified in 2 studies) rASRM stage varied (2 studiesd) |

1206 (6) | 417 | 103 | 411 | 275 | Summary estimates: Sens = 0.62 (0.45 to 0.79); spec = 0.76 (0.53 to 1.00) |

Summary estimates do not meet the predetermined criteria for a triage or replacement test; varying populations across the studies |

| CA‐125 (cancer antigen‐125)a@, a#, a$, a%, a&, a!! cut‐off value > 35‐36 U/ml (1 study > 36 U/ml) cycle phase varied; not specified in 7 studies rASRM stage varied; not reported in 2 studies (1 studyc, 2 studiesd, 1 studye) |

3447 (27) | 895 | 169 | 1281 | 1102 | Summary estimates: Sens = 0.40 (0.32 to 0.49); spec = 0.91 (0.88 to 0.94) |

Summary estimates do not meet the predetermined criteria for a triage or replacement test; varying populations across the studies |

| CA‐125 (cancer antigen‐125);a$ cut‐off value > 42 U/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM III‐IVd |

104 (1) | 23 | 5 | 47 | 29 | Sens = 0.44 (0.30 to 0.59); spec = 0.90 (0.79 to 0.97) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

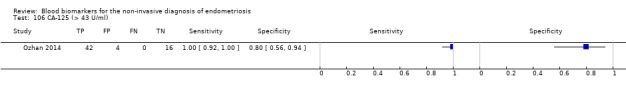

| CA‐125 (cancer antigen‐125) cut‐off value > 43 U/ml cycle phase not reported rASRM III‐IV |

63 (1) | 42 | 4 | 16 | 0 | Sens = 1.00 (0.92 to 1.00); spec = 0.80 (0.56 to 0.94) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; meets criteria for a replacement and SnOUT triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

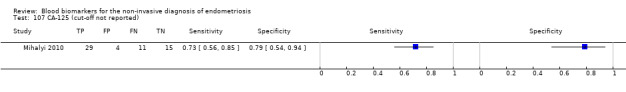

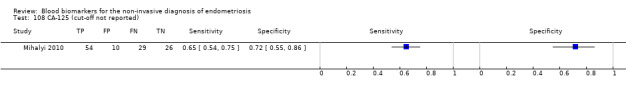

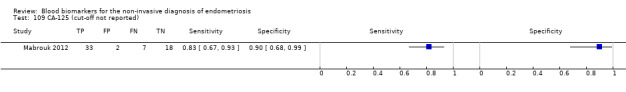

| CA‐125 (cancer antigen‐125) cut‐off value not specified menstrual cycle phasea## rASRM I‐IV ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ follicular cycle phasea## rASRM I‐IV ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ follicular cycle phase rASRM stage not reportedd,e ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ luteal cycle phasea## rASRM I‐IV |

59 (1) ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 119 (1) ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 60 (1) ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 116 (1) |

29 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 54 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 33 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 53 |

4 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 10 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 2 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 11 |

15 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 26 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 18 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 27 |

11 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 29 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 7 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 25 |

Sens = 0.72 (0.56 to 0.85); spec = 0.79 (0.54 to 0.94) ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ Sens = 0.65 (0.54 to 0.75); spec = 0.72 (0.55 to 0.86) ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ Sens = 0.82 (0.67 to 0.93); spec = 0.90 (0.68 to 0.99) ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ Sens = 0.68 (0.56 to 0.78); spec = 0.71 (0.54 to 0.85) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; 1 study approaches criteria for a SpIN triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended with defined cut‐off value; varying populations and undefined cut‐off values; not combined in meta‐analysis |

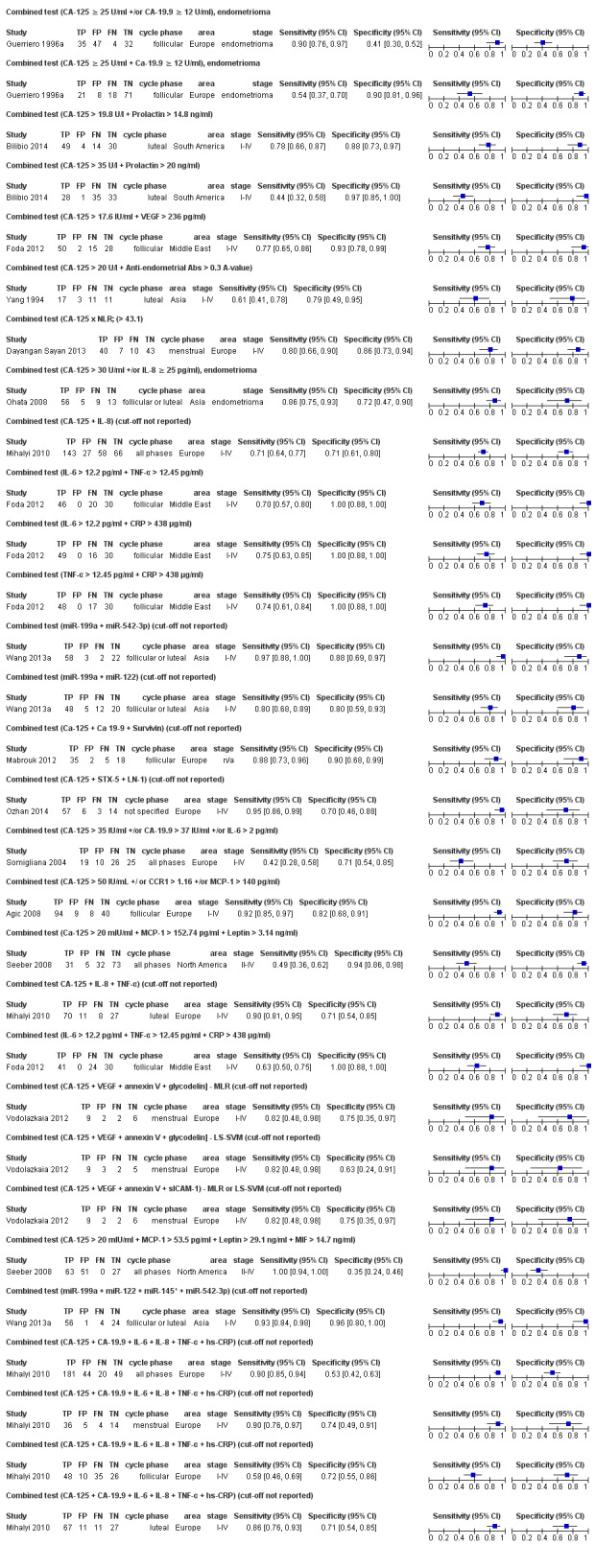

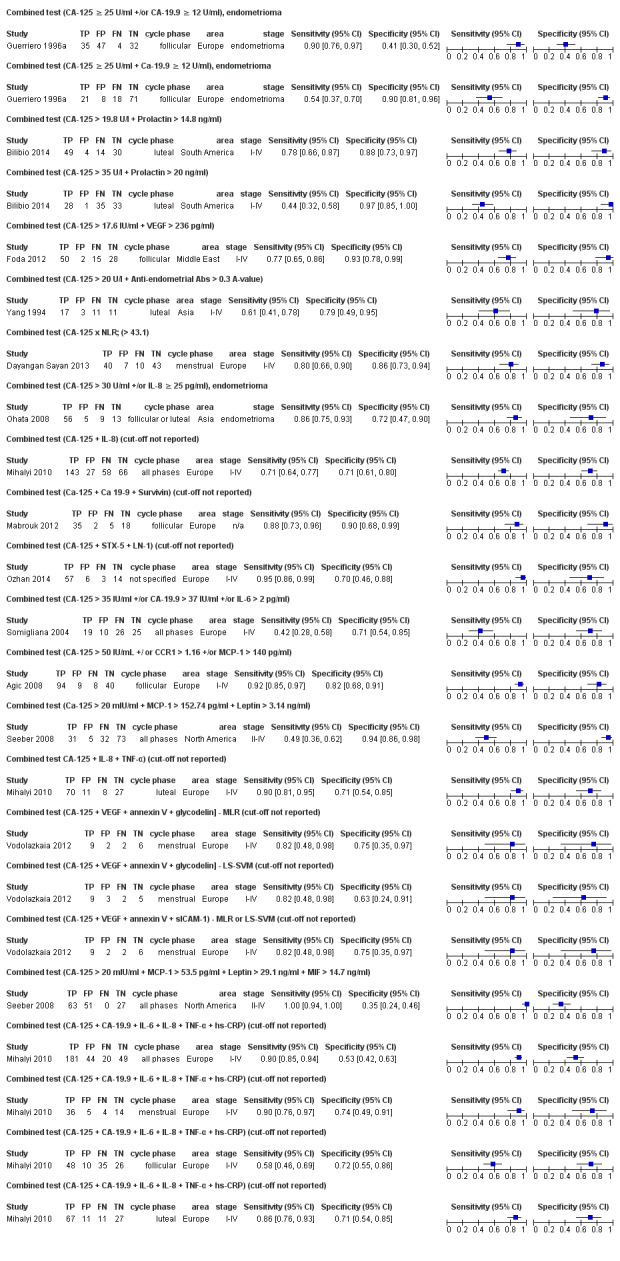

| 11. Combined test ‐ 2 blood biomarkers | |||||||

| CA‐125 +/or CA‐19.9 U/mla# cut‐of threshold CA‐125 ≥ 25 U/ml; CA‐19.9 ≥ 12 U/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM III‐IVd combined test by ROC analysis |

118 (1) | 35 | 47 | 32 | 4 | Sens = 0.90 (0.76 to 0.97); spec = 0.41 (0.30 to 0.52) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

| CA‐125 + CA‐19.9 U/mla# cut‐of threshold CA‐125 ≥ 25 U/ml; CA‐19.9 ≥ 12 U/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM III‐IVd combined test by ROC analysis |

118 (1) | 21 | 8 | 71 | 18 | Sens = 0.54 (0.37 to 0.70); spec = 0.90 (0.81 to 0.96) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; approaches criteria for a SpIN triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

| CA‐125 + Prolactina$ cut‐off threshold CA‐125 > 19.8 U/l; Prolactin > 14.8 ng/ml luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IVc combined test by ROC analysis |

97 (1) | 49 | 4 | 30 | 14 | Sens = 0.78 (0.66 to 0.87); spec = 0.88 (0.73 to 0.97) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

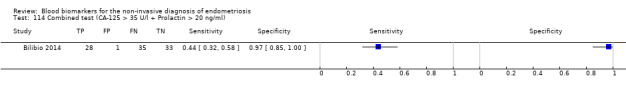

| CA‐125 + Prolactina$ cut‐off threshold CA‐125 > 35 U/l; Prolactin > 20 ng/ml luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IVc combined test by ROC analysis |

97 (1) | 28 | 1 | 33 | 35 | Sens = 0.44 (0.32 to 0.58); spec = 0.44 (0.32 to 0.58) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

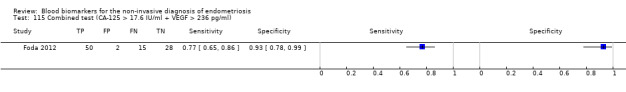

| CA‐125 + VEGF cut‐off threshold CA‐125 > 17.6 U/ml; VEGF > 236 pg/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM I‐IV combined test by ROC analysis |

95 (1) | 50 | 2 | 28 | 15 | Sens = 0.77 (0.65 to 0.86); spec = 0.93 (0.78 to 0.99) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; approaches criteria for a SpIN triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

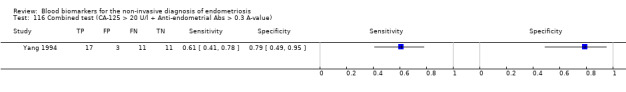

| CA‐125 + anti‐endometrial Abs cut‐off threshold CA‐125 > 20 U/l; anti‐endometrial Abs > 0.3 A‐value luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV selection or classification method not reported |

42 (1) | 17 | 3 | 11 | 11 | Sens= 0.61 (0.41 to 0.78); spec = 0.79 (0.49 to 0.95) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

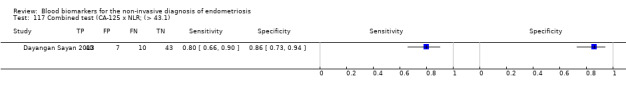

| CA‐125 x NLR cut‐off threshold > 43.1 menstrual cycle phase rASRM I‐IV combined test ROC analysis |

100 (1) | 40 | 7 | 43 | 10 | Sens = 0.80 (0.66 to 0.90); spec = 0.86 (0.73 to 0.94) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

| CA‐125 +/or IL‐8 cut‐off threshold CA‐125 > 30 U/ml; IL‐8 ≥ 25 pg/ml follicular or luteal cycle phase rASRM III‐IVd combined test ROC analysis |

83 (1) | 56 | 5 | 13 | 9 | Sens = 0.86 (0.75 to 0.93); spec = 0.72 (0.47 to 0.90) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

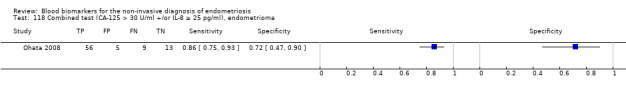

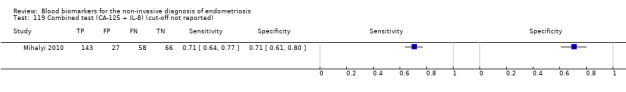

| CA‐125 + IL‐8 cut‐off threshold not specified any cycle phase rASRM I‐IV combined test by multivariate analysis using stepwise logistic regression and by ROC analysis |

294 (1) | 143 | 27 | 58 | 66 | Sens = 0.71 (0.64 to 0.77); spec= 0.71 (0.61 to 0.80) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

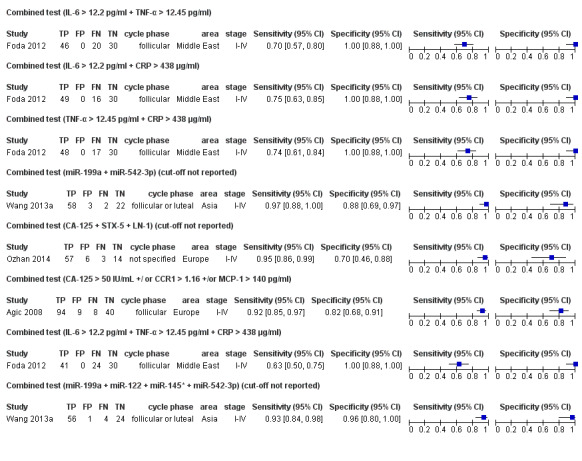

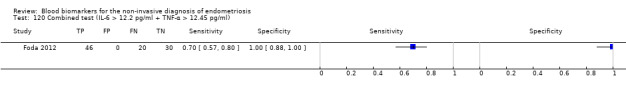

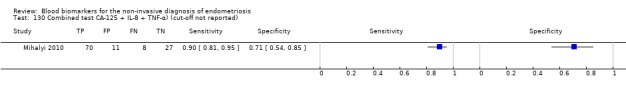

| IL‐6 + TNF‐α cut‐off threshold IL‐6 > 12.2 pg/ml; TNF‐α > 12.45 pg/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM I‐IV combined test ROC analysis |

96 (1) | 46 | 0 | 30 | 20 | Sens = 0.70 (0.57 to 0.80); spec = 1.00 (0.88 to 1.00) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; meets criteria for a SpIN triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

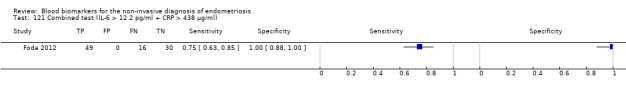

| IL‐6 + CRP cut‐off threshold IL‐6 >12.2 pg/ml; CRP > 438 μg/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM I‐IV combined test by ROC analysis |

95 (1) | 49 | 0 | 30 | 16 | Sens = 0.75 (0.63 to 0.85); spec = 1.00 (0.88 to 1.00) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; meets criteria for a SpIN triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

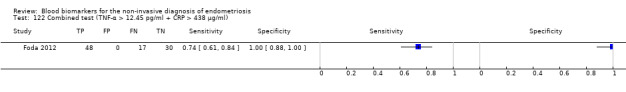

| TNF‐α + CRP cut‐off threshold NF‐α > 12.45 pg/ml; CRP > 438 μg/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM I‐IV combined test by ROC analysis |

95 (1) | 48 | 0 | 30 | 17 | Sens = 0.74 (0.61 to 0.84); spec = 1.00 (0.88 to 1.00) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; meets criteria for a SpIN triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

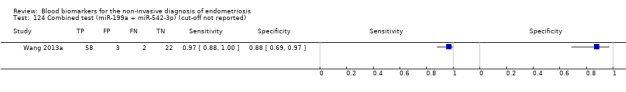

| miR‐199a + miR‐542‐3p cut‐off threshold not specified follicular or luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV combined test by discriminant and ROC analysis |

85 (1) | 58 | 3 | 22 | 2 | Sens = 0.97 (0.88 to 1.00); spec = 0.88 (0.69 to 0.97) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; meets criteria for a replacement and SnOUT triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

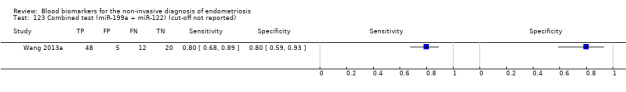

| miR‐199a + miR‐122 cut‐off threshold not specified follicular or luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV combined test by discriminant and ROC analysis |

85 (1) | 48 | 5 | 20 | 12 | Sens = 0.80 (0.68 to 0.89); spec = 0.80 (0.59 to 0.93) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

| 12. Combined test ‐ 3 blood biomarkers | |||||||

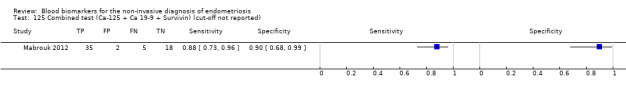

| CA‐125 + CA‐19‐9 + survivin cut‐off threshold not specified follicular cycle phase rASRM stage not reportede combined test by logistic regression and ROC analysis |

60 (1) | 35 | 2 | 18 | 5 | Sens = 0.88 (0.73 to 0.96); spec = 0.90 (0.68 to 0.99) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; approaches criteria for a SpIN triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

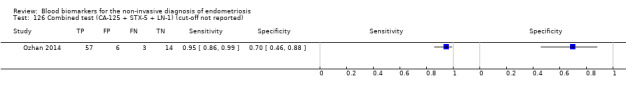

| CA‐125 + STX‐5 + LN‐1 cut‐off threshold not specified cycle phase not specified rASRM I‐IV combined test by multivariate logistic regression and ROC analysis |

80 (1) | 57 | 6 | 14 | 3 | Sens = 0.95 (0.86 to 0.99); spec = 0.70 (0.46 to 0.88) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; meets criteria for a SnOUT triage test and approaches criteria for a replacement test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

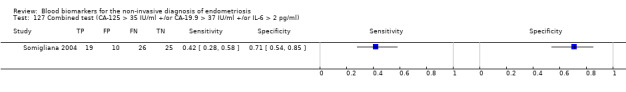

| CA‐125 +/or CA‐19.9 +/or IL‐6 cut‐off threshold CA‐125 > 35 U/ml; CA‐19.9 > 37 U/ml; IL‐6 > 2 pg/ml any cycle phase rASRM I‐IV combined test by ROC analysis |

80 (1) | 19 | 10 | 25 | 26 | Sens = 0.42 (0.28 to 0.58); spec = 0.71 (0.54 to 0.85) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

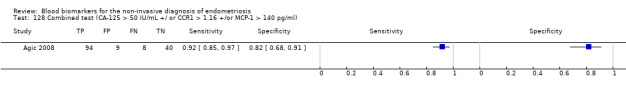

| CA‐125 +/ or CCR1 +/or MCP‐1 CA‐125 > 50 U/ml; CCR1 > 1.16; MCP‐1 > 140 pg/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM I‐IV selection or classification method not reported |

151 (1) | 94 | 9 | 40 | 8 | Sens = 0.92 (0.85 to 0.97); spec = 0.82 (0.68 to 0.91) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; approaches criteria for a replacement and SnOUT triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

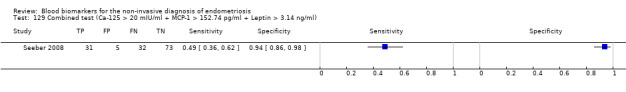

| CA‐125 + MCP‐1 + Leptin cut‐off threshold CA‐125 > 20 U/ml; MCP‐1 > 152.7 pg/ml; Leptin > 3.14 ng/ml any cycle phase rASRM II‐IV combined test by a two‐tiered algorithm using classification and regression tree (CART) |

141 (1) | 31 | 5 | 73 | 32 | Sens = 0.49 (0.36 to 0.62); spec = 0.94 (0.86 to 0.98) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; approaches criteria for a SpIN triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

| CA‐125 + IL‐8 + TNF‐α cut‐off threshold not specified luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV combined test by multivariate analysis using stepwise logistic regression and ROC analysis |

116 (1) | 70 | 11 | 27 | 8 | Sens = 0.90 (0.81 to 0.95); spec = 0.71 (0.54 to 0.85) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; approaches criteria for a SnOUT triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

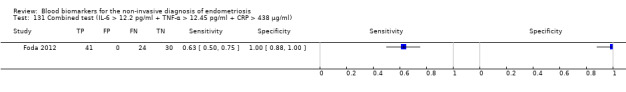

| IL‐6 + TNF‐α + CRP cut‐off threshold IL‐6 > 12.2 pg/ml; TNF‐α > 12.45 pg/ml; CRP > 438 μg/ml follicular cycle phase rASRM I‐IV combined test by ROC analysis |

95 (1) | 41 | 0 | 30 | 24 | Sens = 0.63 (0.50 to 0.75); spec = 1.00 (0.88 to 1.00) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; meets criteria for a SpIN triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

| 13. Combined test ‐ 4 blood biomarkers | |||||||

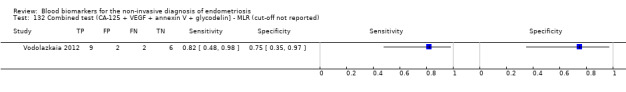

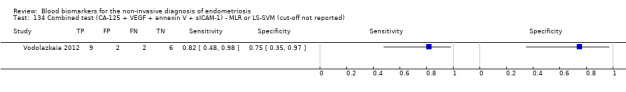

| CA‐125 + VEGF + annexin V + glycodelina# cut‐off threshold not specified menstrual cycle phase rASRM I‐IVb combined test by multivariate logistic regression and ROC analysis |

19 (1) | 9 | 2 | 6 | 2 | Sens = 0.82 (0.48 to 0.98); spec = 0.75 (0.35 to 0.97) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

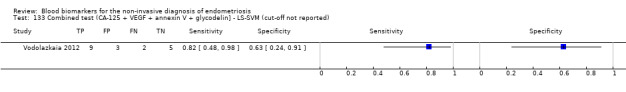

| CA‐125 + VEGF + annexin V + glycodelina# cut‐off threshold not specified menstrual cycle phase rASRM I‐IVb combined test by a least squares support vector machines model (LS‐SVM) and ROC analysis |

19 (1) | 9 | 3 | 5 | 2 | Sens = 0.82 (0.48 to 0.98); spec = 0.63 (0.24 to 0.91) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

| CA‐125 + VEGF + annexin V + sICAM‐1 cut‐off threshold not specified menstrual cycle phase rASRM I‐IVb combined test by either multivariate logistic regression or a least squares support vector machines model (LS‐SVM) and ROC analysis |

19 (1) | 9 | 2 | 6 | 2 | Sens = 0.82 (0.48 to 0.98); spec = 0.75 (0.35 to 0.97) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

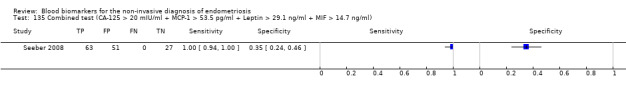

| CA‐125 + MCP‐1 + Leptin + MIF cut‐off threshold CA‐125 > 20 U/ml; MCP‐1 > 53.5 pg/ml; Leptin > 29.1 ng/ml; MIF > 14.7 ng/ml any cycle phase rASRM II‐IV combined test by a two‐tiered algorithm using classification and regression tree (CART) |

141 (1) | 63 | 51 | 27 | 0 | Sens = 1.00 (0.94 to 1.00); spec = 0.35 (0.24 to 0.46) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

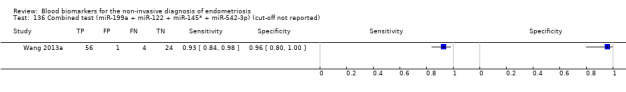

| miR‐199a + miR‐122 + miR‐145* + miR‐542‐3p cut‐off threshold not specified follicular or luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV combined test by discriminant and ROC analysis |

85 (1) | 56 | 1 | 24 | 4 | Sens = 0.93 (0.84 to 0.98); spec = 0.96 (0.80 to 1.00) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; meets criteria for a SpIN triage test and approaches criteria for a replacement test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

| 14. Combined test ‐ 6 blood biomarkers | |||||||

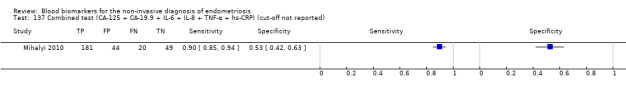

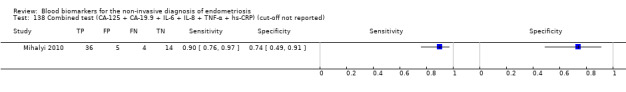

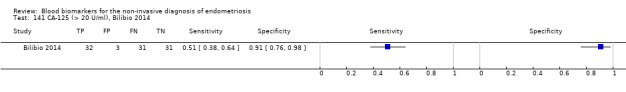

| CA‐125 + CA‐19.9 + IL‐6 + IL‐8 + TNF‐α + hs‐CRPa$ cut‐off threshold not specified any cycle phase rASRM I‐IV combined test by multivariate analysis using stepwise logistic regression and ROC analysis |

295 (1) | 181 | 44 | 49 | 20 | Sens = 0.90 (0.85 to 0.94); spec = 0.53 (0.42 to 0.63) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; approaches criteria for a SnOUT triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

| CA‐125 + CA‐19.9 + IL‐6 + IL‐8 + TNF‐α + hs‐CRP a$ cut‐off threshold not specified menstrual cycle phase rASRM I‐IV combined test by multivariate analysis using stepwise logistic regression and ROC analysis |

59 (1) | 36 | 5 | 14 | 4 | Sens = 0.90 (0.76 to 0.97); spec = 0.74 (0.49 to 0.91) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions; approaches criteria for a replacement and SnOUT triage test; further diagnostic test accuracy studies recommended |

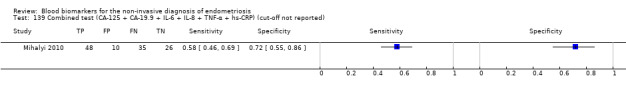

| CA‐125 + CA‐19.9 + IL‐6 + IL‐8 + TNF‐α + hs‐CRPa$ cut‐off threshold not specified follicular cycle phase rASRM I‐IV combined test by multivariate analysis using stepwise logistic regression and ROC analysis |

119 (1) | 48 | 10 | 26 | 35 | Sens = 0.58 (0.46 to 0.69); spec = 0.72 (0.55 to 0.86) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

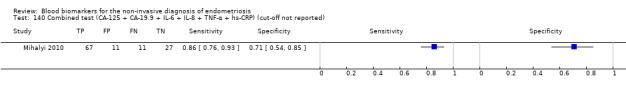

| CA‐125 + CA‐19.9 + IL‐6 + IL‐8 + TNF‐α + hs‐CRPa$ cut‐off threshold not specified luteal cycle phase rASRM I‐IV combined test by multivariate analysis using stepwise logistic regression and ROC analysis |

116 (1) | 67 | 11 | 27 | 11 | Sens = 0.86 (0.76 to 0.93); spec = 0.71 (0.54 to 0.85) |

Insufficient evidence to draw meaningful conclusions |

|

a Same biomarker was tested in the same/overlapping cohort; similar symbol designates studies/groups of studies with overlapping cohorts, hence can not be combined in meta‐analysis b Only for US‐negative endometriosis c Only peritoneal endometriosis d Only ovarian endometriosis versus other benign ovarian cysts e Only deep infiltrating endometriosis or endometrioma + deep infiltrating endometriosis | |||||||

MW: molecular weight; rASRM: revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine; ROC: receiver operating characteristic

For a comprehensive list of all biomarkers with their biological annotation, please see Appendix 1.

Background

Target condition being diagnosed

Endometriosis

Endometriosis is defined as an inflammatory condition characterised by endometrial‐like tissue at sites outside the uterus (Johnson 2013). Endometriotic lesions can occur at different locations, including the pelvic peritoneum and the ovary, or they can penetrate pelvic structures below the surface of the peritoneum (defined as deeply infiltrating endometriosis, or DIE). Current knowledge suggests that each of these types of endometriosis is a separate clinical entity, but they can coexist in the same woman. Rarely, endometriotic implants can be found at more distant sites, including the lung, liver, pancreas and operative scars, with consequent variations in presenting symptoms.

Endometriosis afflicts 10% of reproductive‐aged women, causing dysmenorrhoea (painful periods), dyspareunia (painful intercourse), chronic pelvic pain and infertility (Vigano 2004). The clinical presentation can vary from asymptomatic and unexplained infertility to severe dysmenorrhoea and chronic pain. These symptoms can occur with bowel or urinary symptoms, an abnormal pelvic examination or the presence of a pelvic mass; however, no symptom is specific to endometriosis. The estimated prevalence of endometriosis in the symptomatic population is 35% to 50% (Giudice 2004).

Women with endometriosis are also at increased risk of developing several cancers and autoimmune disorders (Sinaii 2002; Somigliana 2006). The presence of disease is associated with changes in the immune response, vascularisation, neural function, the peritoneal environment and the eutopic endometrium (tissue lining the uterine cavity), suggesting that endometriosis is a systemic rather than localised condition (Giudice 2004). Endometriosis has a profound effect on psychological and social well‐being and imposes a substantial economic burden on society. Women with endometriosis may incur significant direct medical expenses from diagnostic and therapeutic surgeries, hospital admissions and fertility treatments, while indirect costs, including absenteeism and loss of productivity, compound the economic impact (Gao 2006;Simoens 2012). In the United States, the financial burden of endometriosis is about USD 12,419 per woman (Simoens 2012).

Although research has not been able to fully elucidate the pathogenesis of endometriosis, specialists commonly believe that it occurs when endometrial tissue contained within the menstrual fluid implants at an ectopic site within the pelvic cavity through retrograde flow (Sampson 1927). However, this theory does not explain the fact that only 10% of women develop endometriosis, while retrograde menstruation occurs in up to 90% of women (Halme 1984). There is evidence that a variety of environmental, immunological and hormonal factors are associated with endometriosis and genetic loci that confer a risk of endometriosis, but the relative contribution of these and other causal factors is still unclear (Nyholt 2012; Vigano 2004).

Although it is impossible to time the onset of disease, on average, women have a 6‐ to 12‐year history of symptoms before obtaining a surgical diagnosis, indicative of considerable diagnostic delay (Matsuzaki 2006). Untreated endometriosis is associated with reduced quality of life and contributes to outcomes such as depression, inability to work, sexual dysfunction and missed opportunity for motherhood (Gao 2006). Since endometriosis is a progressive disease in up to 50% of women, early diagnosis has the potential to offer early treatment and prevent progression (D'Hooghe 2002).

Treatment of endometriosis

There is no cure for endometriosis. Treatment options include expectant management, pharmacological (hormonal) therapy and surgery (Johnson 2013). Treatment is individualised, taking into consideration a therapeutic goal (pain relief or conception) and the location of the disease. Current pharmacological therapies such as the combined oral contraceptive pill, progestogens, weak androgens and GnRH agonists and antagonists act to reduce the effect of oestrogen on endometrial tissues and suppress menstruation. These drugs can ameliorate the symptoms of dysmenorrhoea and chronic pelvic pain but are associated with side effects such as breast discomfort, irritability, androgenic symptoms and bone loss. Surgical excision of endometriotic lesions can reduce pain symptoms, but it is associated with high recurrence rates of 40% to 50% at five years postsurgery (Guo 2009). Early treatment of endometriosis improves pain levels as well as physical and psychological functioning. Furthermore, improvements in menstrual management (the use of the intrauterine system (hormonal coil) and the continuous use of the combined contraceptive pill) and fertility preservation (oocyte vitrification) raise the possibility of suppressing the progression of endometriosis and prospectively managing subfertility in endometriosis sufferers. The potential success of these preventive strategies depends on an accurate and early diagnosis. A major impediment to earlier and more efficacious treatment of this disease is diagnostic delay, due to the invasive nature of standard diagnostic tests (Dmowski 1997).

Diagnosis of endometriosis

Clinical history and pelvic examination can raise the possibility of a diagnosis of endometriosis, but the heterogeneity in clinical presentation, the high prevalence of asymptomatic endometriosis (2% to 50%) and the poor association between presenting symptoms and severity of the disease contribute to the difficulty in obtaining a reliable diagnosis based solely on presenting symptoms (Ballard 2008; Fauconnier 2005; Spaczynski 2003). Although an abnormal pelvic examination correlates with the presence of endometriosis on laparoscopy in 70% to 90% of cases (Ling 1999), there is a wide differential diagnosis for most positive physical findings. Furthermore, a normal clinical examination does not exclude endometriosis, as laparoscopically proven disease has been diagnosed in more than 50% of women with a clinically normal pelvic examination (Eskenazi 2001). A variety of tests utilising pelvic imaging, blood markers, eutopic endometrium characteristics, urinary markers or peritoneal fluid components have been suggested as diagnostic measures for endometriosis. Although large numbers of the reported markers distinguish women with and without endometriosis in small pilot studies, many do not show convincing potential as a diagnostic test when they are evaluated in larger studies by different research groups. The diagnostic value of these tests has not previously been fully systematically evaluated and summarised using Cochrane methods. Currently, there is no simple non‐invasive test for the diagnosis of endometriosis that is routinely implemented in clinical practice.

Surgical diagnostic procedures for endometriosis include laparoscopy (minimal access, or keyhole surgery) or laparotomy (open surgery via an abdominal incision). In the last several decades, laparoscopy has become an increasingly common procedure and has largely replaced traditional open surgery in patients suspected of having endometriosis (Yeung 2009). Laparoscopy has significant advantages over laparotomy, including fewer complications and shorter recovery times. Furthermore, a magnified view at laparoscopy allows better visualisation of the peritoneal cavity. Despite continuing controversy in the literature with regard to the superiority of one surgical modality over another in treating pelvic pathology, laparoscopy is the preferred technique to evaluate the pelvis and abdomen and to treat benign conditions such as ovarian endometriomas (Medeiros 2009). Surgery is currently also the only acceptable method of determining the extent and severity of endometriosis. There are several different classification systems for endometriosis (Adamson 2008; Batt 2003; Chapron 2003a; Martin 2006), but most researchers and clinicians use the revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine (rASRM) classification, which is internationally accepted as a respected tool for the objective assessment of the disease (ASRM 1997). The rASRM classification system considers the appearance, size and depth of peritoneal or ovarian implants and adhesions that are visualised during laparoscopy and allows uniform documentation of the extent of disease (Table 2). Unfortunately, this classification system has little value in clinical practice due to the lack of correlation between laparoscopic staging, the severity of symptoms and response to treatment (Chapron 2003b; Guzick 1997; Vercellini 1996). The World Endometriosis Society has recently undertaken an endeavour to attain consensus around the optimal classification for endometriosis (Johnson 2015).

1. Staging of endometriosis, rASRM classification.

| Location of endometriosis | Extent | Depth | ||

| < 1 cm | 1‐3 cm | > 3 cm | ||

| Peritoneum | Superficial | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Deep | 2 | 4 | 6 | |

| Ovary | R Superficial | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Deep | 4 | 16 | 20 | |

| L Superficial | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

| Deep | 4 | 16 | 20 | |

| Posterior cul‐de‐sac obliteration | Partial | Complete | ||

| 4 | 40 | |||

| Adhesions | < 1/3 Enclosure | 1/3‐2/3 Enclosure | > 2/3 Enclosure | |

| Ovary | R Filmy | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Dense | 4 | 8 | 16 | |

| L Filmy | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

| Dense | 4 | 8 | 16 | |

| Tube | R Filmy | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Dense | 4a | 8a | 16 | |

| L Filmy | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

| Dense | 4a | 8a | 16 | |

Stage ·1 (Minimal) ‐ score 1‐5; Stage II (Mild) ‐ score 6‐15; Stage III (Moderate) ‐ score 16‐40; Stage IV (Severe) ‐ score >40

aIf the fimbriated end of the fallopian tube is completely enclosed, change the point assignment to 16 (ASRM 1997)

The European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) Special Interest Group for Endometriosis stated in their diagnostic and treatment guidelines that for most forms of endometriosis, women presenting with symptoms cannot obtain a definitive diagnosis without visual inspection of the pelvis at laparoscopy as the gold standard investigation (Kennedy 2005). Currently the visual or histological identification of endometriotic tissue in the pelvic cavity during surgery is not just the best available but the only diagnostic test for endometriosis in clinical practice.

The disadvantages of laparoscopic surgery include (but are not limited to) the high cost, the need for general anaesthesia and the potential for adhesion formation postprocedure. Laparoscopy has been associated with a 2% risk of injury to pelvic organs, a 0.001% risk of damaging a major blood vessel and a mortality rate of 0.0001% (Chapron 2003c). Even though the major complications of laparoscopy are rare, it is difficult to determine the exact incidence of complications, and delayed recognition adds to surgical morbidity and mortality. Only a third of women who undertake a laparoscopic procedure will receive a diagnosis of endometriosis; therefore many disease‐free women are unnecessarily exposed to surgical risk (Frishman 2006).

The validity of laparoscopy as a reference test for endometriosis has is highly dependent on the skills of the surgeon. The diagnostic accuracy of laparoscopic visualisation has been compared with histological confirmation in a sole systematic review, and it was estimated as having a sensitivity of 0.94 and specificity of 0.79 (Wykes 2004). Subsequent studies suggested that incorporating histological verification in the diagnosis of endometriosis may improve diagnostic accuracy (Almeida Filho 2008; Marchino 2005; Stegmann 2008), but these papers have not been systematically reviewed. The clinical significance of histological verification remains debatable, and a diagnosis based on visual findings is generally reliable as long as properly trained and experienced surgeons perform an appropriate inspection of the abdominal cavity (Redwine 2003). Furthermore, excised potential endometriotic tissues are rarely serially sectioned in clinical practice, and pathologists can miss small lesions in mild disease. Thus, sampling inconsistencies are also likely to influence the accuracy of histological reporting.

Summary

A diagnostic test without the need for surgery would reduce the associated surgical risks, increase accessibility to a diagnostic test and improve treatment outcomes. The need for an accurate non‐invasive diagnostic test for endometriosis continues to encourage extensive research in the field and was endorsed at the international consensus workshop at the 10th World Congress of Endometriosis in 2008 (Rogers 2009). Although multiple markers and imaging techniques have been explored as diagnostic tests for endometriosis, none of them have been implemented routinely in clinical practice, and many have not been subject to a systematic review.

Index test(s)

This review assesses blood‐based biomarkers that have been proposed as non‐invasive tests for the diagnosis of endometriosis as part of the review series on non‐invasive diagnostic tests for endometriosis (Table 3). The other reviews from this series include 'Imaging modalities for the non‐invasive diagnosis of endometriosis', 'Endometrial biomarkers for the non‐invasive diagnosis of endometriosis', 'Urinary biomarkers for the non‐invasive diagnosis of endometriosis', and 'Combination of the non‐invasive tests for the diagnosis of endometriosis', which also summarises all the reviews from the series.

2. Blood biomarkers evaluated in this review.

| Biomarker | |

| Angiogenesis and growth factors and their receptors | |

| Glycodelin‐A (PP14 or PAEP) (or placental protein 14 or progestogen‐associated endometrial protein)a | VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor)a |

| IGFBP‐3 (insulin‐like growth factor‐binding protein‐3)a | Urocortin |

| Leptina | |

| Apoptosis markers | |

| Annexin Va | Survivin |

| Cell adhesion molecules and other matrix‐related proteins | |

| sICAM‐1 (soluble form of intercellular‐adhesion molecule‐1)a | LN‐1 (laminin‐1) |

| High‐throughput molecular markers | |

| Metabolome | Proteome |

| Hormonal markers | |

| Prolactin | |

| Immune system and inflammatory markers | |

Autoantibodies

|

Immune cells

|

Chemokines

|

Interleukins

|

Other cytokines

|

Other immune/inflammatory markers

|

| Other peptides and proteins shown to influence key events implicated in endometriosis | |

| Follistatin, activin‐binding protein; involved in diverse activities from embryonic development to cell secretion | |

| STX‐5 (syntaxin‐5), protein belonging to syntaxin‐family, a vesicular membrane fusion protein receptor in endoplasmic reticulum membrane | |

| Oxidative stress markers | |

| Carbonyls | Thiols |

| PON‐1 (paraoxonase‐1) | |

| Post‐transcriptional regulators of gene expression (microRNAs) | |

| miR‐9* | miR‐141* |

| miR‐17‐5 | miR‐145* |

| miR‐20a | miR‐199a |

| miR‐22 | miR‐532‐3p |

| miR‐122 | |

| Tumour markers | |

| CA‐15.3 (cancer antigen‐15.3) | CA‐72 (TAG‐72) (cancer antigen‐72 or (tumour associated glycoprotein‐72]) |

| CA‐19.9 (cancer antigen‐19.9)a | CA‐125 (cancer antigen‐125)a |

| Blood biomarkers that did not exhibit differential expression in endometriosis and for which diagnostic performance was not assessed | |

| Angiogenesis and growth factors and their receptors | |

| Angiogenic activity of serum | IGF‐1 (insulin‐like growth factor‐1) |

| CAC (circulating angiogenic cells) | IGF‐2 (insulin‐like growth factor‐2) |

| EGF (epidermal growth factor) | IGFBP‐3 (insulin‐like growth factor binding protein‐3)a |

| sEGF‐R (soluble epidermal growth factor‐receptor) | Leptina |

| sFlt‐1 (sVEGFR‐1] (soluble fms‐like tyrosine kinase or variant of VEGF receptor 1) | PDGF (platelet derived growth factor) |

| Glycodelin‐A (PP14 or PAEP] (or placental protein 14 or progestogen‐associated endometrial protein)a | VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor)a |

| HGF (hepatocyte growth factor) | |

| Apoptosis markers | |

| Annexin Va | sFas (soluble Fas) |

| Apoptotic cells | anti‐survivin Abs (anti‐survivin antibodies) |

| Cell adhesion molecules and other matrix‐related proteins | |

| Biglycan | sE‐selectin (soluble E selectin) |

| sICAM‐1 (soluble form of intercellular‐adhesion molecule‐1)a | MMP‐9 (matrix metalloproteinase‐9) |

| Cytoskeleton molecules | |

| CK 19 (Cytokeratin‐19) | |

| DNA‐repair and telomere maintenance molecules | |

| TL (telomere length) | |

| Hormonal markers | |

| E2 (oestradiol) | LH (luteinizing hormone) |

| FSH (follicle stimulating hormone) | Progesterone |

| Immune system and inflammatory markers | |

Autoantibodies

|

Interleukins

|

Chemokines

other Cytokines

| |

Immune cells

|

Other immune/inflammatory markers

|

| Nerve growth markers | |

| CNTF (ciliary Neurotrophic Factor) | NGF (nerve growth factor) |

| GDNF (glial cell‐derived neurotrophic factor) | NT4 (neurotrophin 4) |

| Other peptides and proteins shown to influence key events implicated in endometriosis | |

| DBP (vitamin D binding protein), component of Gc‐globulin and is the major plasma carrier protein of vitamin D metabolites, responsible for the transport of fat and endotoxins, important factor in the actin scavenging system, plays an important role in the immune system | |

| Enolase (phosphopyruvate hydratase], a glycolytic enzyme, frequently associated with autoimmune diseases | |

| PDPK1 (phosphoinositide dependent protein kinase 1), a master kinase involved in the signalling pathways activated by several growth factors and hormones (glucose metabolism, cellular proliferation, cellular survival, and angiogenesis) | |

| Oxidative stress markers | |

| Ascorbic acid | Nitrotyrosine |

| GSH (glutathione) | SOD3 (superoxide dismutase‐3) |

| HSP70 (heat shock protein 70) | TRX (Thioredoxin) |

| IMA (Ischemia‐modified albumin) | Vitamin E |

| Malondialdehyde | |

| Tumour markers | |

| AFP (alpha‐fetoprotein) | c‐erbB‐2 (HER‐2/neu] (erythroblastosis oncogene B or human epidermal growth factor receptor‐2 derived from glioblastoma) |

| CA‐19.9 (cancer antigen‐19.9)a | HE4 (human epididymal secretory protein E4) |

| CA‐125 (cancer antigen‐125)a | |

|

a Biomarkers that belong to both groups (evaluated as a diagnostic test for endometriosis in some studies and did not exhibit differential expression in endometriosis in the other studies). For a comprehensive list of all biomarkers with their biological annotation, please see Appendix 1. | |

The definition of 'non‐invasive' varies between medical dictionaries but refers to a procedure that does not involve penetration of skin or physical entrance to the body (McGraw‐Hill Dictionary of Medicine 2006; The Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine 2011). Although venipuncture for blood collection is invasive by this definition, blood tests are generally considered to be non‐invasive or minimally invasive when compared to diagnostic surgery. For the purpose of these reviews, we will define all tests that do not involve anaesthesia and surgery as non‐invasive.

The advantages of using a blood test for the diagnosis of endometriosis are that it is minimally invasive, readily available, acceptable to women, provides a rapid result and is more cost‐effective when compared to surgery. However, blood testing is dependent on the reliability of laboratory techniques and quality control protocols. Blood biomarker levels may also be susceptible to variation during the menstrual cycle.

Research has identified cellular and molecular processes that characterise ectopic endometrium and peritoneal fluid in human and animal models (D'Hooghe 2001; Hull 2008; Kao 2003). Different studies have evaluated markers of these pathophysiological processes in blood samples as a single test or a combination of several biomarkers. Categories of blood markers include: angiogenic and growth factors; markers of apoptosis; cell adhesion molecules and other matrix‐related proteins; cytoskeleton molecules; DNA‐repair/telomere maintenance molecules; hormonal markers; high‐throughput molecular markers; hormonal markers; immune system and inflammatory markers; nerve growth markers; oxidative stress markers; post‐transcriptional regulators of gene expression (circulating nuclear DNAs, microRNAs); tumour markers; and other peptides/proteins shown to influence key events implicated in endometriosis. Most blood‐based tests have only been evaluated in a limited number of small studies with varying methods, laboratory techniques and types of assay.The most extensively studied biomarker for endometriosis is cancer antigen‐125 (CA‐125), a glycoprotein expressed on coelomic epithelial tissues such as the peritoneum. An older meta‐analysis concluded that CA‐125 had a limited ability to diagnose endometriosis (Mol 1998). However, the review did not describe the selection process to include studies. Since then, further studies evaluating CA‐125 have been published, and the methodologies of diagnostic test reviews have improved, so an updated review of CA‐125 is warranted (Brosens 2003; Bedaiwy 2004; Matalliotakis 2008; Yang 2004).

A large systematic review of all proposed biomarkers for endometriosis in serum, plasma and urine identified over 100 putative biomarkers, but the authors were unable to identify any biomarker (single or in a panel) that they could recommend for use in clinical practice (May 2010). A more recent narrative review concurred with this conclusion (Fassbender 2015). There is a current need to re‐evaluate the diagnotic test accuracy of blood tests for endometriosis using Cochrane methods.

Clinical pathway

Women presenting with symptoms of endometriosis (dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain or difficulty conceiving) are generally investigated with a pelvic ultrasound scan to exclude other pathologies, which is in line with international guidelines (ACOG 2010; Dunselman 2014; SOGC 2010). There are no other standard investigative tests, and although evidence suggests that MRI is superior to ultrasound, it is used conservatively because of its cost. If patients seek pain management rather than conception, physicians generally initiate empirical treatment with progestogens or the combined oral contraceptive pill. Diagnostic laparoscopy is considered if empirical treatment fails or if women decline or do not tolerate empirical treatment. In women who have difficulty conceiving, laparoscopy can be undertaken before fertility treatment (particularly if severe pelvic pain or endometrioma are present) or after failed assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatments. Physicians may also diagnosis endometriosis during fertility investigations in women who have minimal or no pain symptomatology.

On average there is a delay of 6 to 12 years from onset of symptoms to definitive diagnosis at surgery. Early referral to a gynaecologist with the capability to perform diagnostic surgery is associated with a shorter time to diagnosis. Collectively, young women, women in remote and rural locations and women of lower socioeconomic status have reduced access to surgery and are less likely to obtain a prompt diagnosis of endometriosis.

Prior test(s)

Most women presenting with symptoms suggestive of endometriosis have a full history and examination and a routine gynaecological ultrasound before physicians recommend they undergo diagnostic surgery. However, there is no consensus on whether any other test should be routinely used as part of a standardised approach.

Role of index test(s)

A new diagnostic test can fulfil one of three roles.