Abstract

Painful diabetic neuropathy (PDN) is a diabetes mellitus complication. Unfortunately, the mechanisms underlying PDN are still poorly understood. Adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-gated P2X7 receptor (P2X7R) plays a pivotal role in non-diabetic neuropathic pain, but little is known about its effects on streptozotocin (STZ)-induced peripheral neuropathy. Here, we explored whether spinal cord P2X7R was correlated with the generation of mechanical allodynia (MA) in STZ-induced type 1 diabetic neuropathy in mice. MA was assessed by measuring paw withdrawal thresholds and western blotting. Immunohistochemistry was applied to analyze the protein expression levels and localization of P2X7R. STZ-induced mice expressed increased P2X7R in the dorsal horn of the lumbar spinal cord during MA. Mice injected intrathecally with a selective antagonist of P2X7R and P2X7R knockout (KO) mice both presented attenuated progression of MA. Double-immunofluorescent labeling demonstrated that P2X7R-positive cells were mostly co-expressed with Iba1 (a microglia marker). Our results suggest that P2X7R plays an important role in the development of MA and could be used as a cellular target for treating PDN.

Keywords: P2X7 receptor (P2X7R), Mechanical allodynia, Streptozotocin, Diabetic mice

1. Introduction

Diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) is reported to occur in 35% of patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) (Pop-Busui et al., 2017; Pan et al., 2018). Painful diabetic neuropathy (PDN) is considered to be a devastating complication that leads to physical handicap and results in a huge economic burden related to diabetes care (Yao et al., 2018). Unfortunately, the underlying mechanisms and pathogenesis of PDN are poorly understood, and therapy for PDN is still based on symptomatic treatments (Berger et al., 2013; Vinik et al., 2013; Javed et al., 2015). Available drugs usually cause unacceptable side effects (Moore et al., 2011) and there are currently no treatments available to arrest or reverse its progression (Pop-Busui et al., 2017).

As a subtype of adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-gated ion channel receptor, P2X7 receptor (P2X7R) comprises an intracellular terminal N, a terminal C, two transmembrane structures (TM1, TM2), and an extracellular loop structure combined with ligands. Based on advances in techniques of homology modeling (Miras-Portugal et al., 2017), P2X7R was reported to be widely distributed in immunity systems, the central nervous system (including the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, brain stem, and spinal cord), and the peripheral nervous system (including dorsal root ganglia) (Illes et al., 2017; Miras-Portugal et al., 2017). It was subsequently detected also in microglia, glial cells, Schwann cells, and neurons. Sánchez-Nogueiro et al. (2014) indicated that it might function in a specific subcellular manner via its localized structure. Research also indicated that activation of microglia (Tsuda et al., 2008; Cheng et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014) in the spinal dorsal horn (SDH) may be involved in neuropathic pain via P2X7R by inducing the release of inflammatory cytokines (Jiang et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2017; Bernier et al., 2018).

Using P2X7-null mice induced by inflammatory adjuvant injection or partial nerve ligation, Chessell et al. (2005) showed that P2X7R was involved in thermal hypersensitivity through the release of interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-10. Kobayashi et al. (2011) found that P2X7Rs are up-regulated at both the messenger RNA (mRNA) and protein levels in spinal microglia after peripheral nerve injury, indicating that the receptors are critical for mechanical hypersensitivity. Ying et al. (2014) also showed that there was an increase of P2X7R in a postsurgical pain model, while mechanical allodynia (MA) was prevented with injection of its blocker before surgery. Spinal P2X7Rs, phosphorylated p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and IL-18 levels were all increased in a rodent model of bone cancer pain. Further, with spinal inhibition of the P2X7/p38/IL-18 pathway and with injection of A839977, a direct antagonism of P2X7R alleviated pain during advanced stages of bone cancer (Ying et al., 2014; Falk et al., 2015). In a diabetic neuropathic pain model, researchers found that following intravenous injection of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs; NONRATT021972 small interfering RNA (siRNA)), the mechanical withdrawal threshold and thermal withdrawal latency increased, while the expression levels of P2X7 mRNA and protein decreased in type 2 DM (T2DM) rats (Liu et al., 2016). However, the role of P2X7R in the generation of MA in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced type 1 diabetic neuropathy remains to be elucidated. Therefore, the objective of our study was to explore the role of P2X7R in the early stages of T1DM-associated MA.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Male C57BL wild-type (WT) mice and P2X7R knockout (KO) mice (weight 20–23 g, cat. 005576) were obtained from the Shanghai Experimental Animal Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Jackson Laboratory, China. All mice were housed in a temperature-and humidity-controlled room, under a 12-h light/dark cycle, with food and water available ad libitum. All experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Fudan University, Shanghai, China and followed the policies issued by the guidelines for pain research of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). The following behavioral testing, quantification of western blots, and immunohistochemical experiments were performed by experimenters who were blinded to the treatment. Each experimental group consisted of at least six mice.

2.2. Diabetic mouse model

After overnight fasting for 12 h (from 20:00 to 8:00), mice were randomly selected and intraperitoneally injected with STZ (100 mg/kg; Sigma, MO, USA) daily for 3 d, while the control group was injected with saline as a vehicle. Fasting blood glucose (FBG) levels were used to confirm the onset of diabetes (Guo et al., 2018). A drop of tail blood was analyzed using a glucometer (Accu-Check Integra test strips, Roche, Switzerland) to document the FBG. On the 7th day after STZ injection, mice with >11.1 mmol/L FBG established the diabetic model. The successful establishment rate was 87.5%.

2.3. Measurement of mechanical allodynia

Mice were placed in Plexiglass chambers on an elevated wire-mesh floor. Paw withdrawal thresholds (PWTs) in response to MA were measured using von Frey hairs (Stoelting Company, Wood Dale, USA). A calibrated series of von Frey hairs were applied to the plantar surface of a hind paw in ascending order (0.4, 0.6, 1.0, 1.4, and 2.0 g) with a force sufficient to bend the hair either for 5 s or until the paw was withdrawn. The PWT was defined as the lowest force (g) that produced at least three withdrawal responses over five consecutive applications.

2.4. Drug administration

Three weeks after STZ injection, the behavioral responses to mechanical stimuli were observed after intrathecal injection of the P2X7R selective antagonist A740003 (5 nmol/L×5 μL and 50 nmol/L×5 μL; Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK) in mice with an FBG of >11.1 mmol/L. Drugs were freshly prepared before each experiment by dissolving them in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, D5879) and were then inserted into the L4–L5 segments of mice under sodium pentobarbital anesthesia. The mice were randomly divided into different drug administration groups. There were no differences in FBG levels among these groups. Any mice exhibiting surgery-related neurological deficits were excluded from the experiment.

2.5. Western blotting analysis

Mice were deeply anesthetized with intraplantar 25% (0.25 g/mL) urethane at different time points after STZ injection. Then the bilateral dorsal halves of the spinal cord (segments L4–L5) were rapidly removed and homogenized in lysis buffer containing a mixture of protease inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland) and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF; Sigma, MO, USA). Twenty micrograms of protein samples were loaded, separated on 10% (0.1 g/mL) sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels (Bio-Rad, CA, USA), and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, MO, USA). The membranes were incubated with primary antibodies (rabbit anti-P2X7R, 1:2000, Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel) at 4 °C overnight, followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated (goat anti-rabbit, Thermo Pierce, USA) secondary antibodies (1:1000; Pierce) for 2 h at 4 °C. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) antibody was probed as a loading control (primary antibody was HRP-conjugated monoclonal mouse anti-GAPDH (1:10000, Shanghai Kangchen Bio-technology Company, China), followed by donkey-anti-goat (1:2000, Jackson, PA, USA)). Signals were visualized via enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Pierce), and captured with a ChemiDoc XRS system (Bio-Rad). The western blotting analysis was performed at least three times. The Bio-Rad image analysis system was used to measure the integrated optical density of specific bands.

2.6. Immunohistochemistry

Mice were anesthetized with overdoses of urethane and transcardially perfused with saline, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 mol/L phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4). The L4–L6 segments of the spinal cord were rapidly removed and post-fixed for 2 or 4 h at 4 °C. Then the tissue was immersed in a 10%–30% sucrose gradient in PBS (pH 7.4, 0.1 mol/L). Transverse spinal cord sections (35 μm) were blocked with 10% (0.1 g/mL) donkey serum in TNB buffer (0.1 mol/L Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.15 mol/L NaCl, and 0.5% (5 g/L) blocking reagent) for 2 h at room temperature (24–26 °C), and then incubated with mixed primary antibodies (rabbit-anti-P2X7R (1:500, Alomone Labs, Israel) with goat-anti-Iba1 (1:2000, Wako Chemicals, USA) or mouse-anti-NeuN (1:2000, Chemicon, USA) or mouse-anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; 1:2000, Sigma, USA)) for 36 h at 4 °C. After three washes with TNT buffer (0.1 mol/L Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.15 mol/L NaCl, 0.05% (0.5 g/L) Tween 20), sections were incubated with the corresponding biotinylated secondary antibodies for 2 h at 4 °C. After washing, sections were incubated with streptavidin (SA)-HRP (Thermo Scientific Pierce Protein Research Products, USA) for 30 min at 24–26 °C, washed again, and incubated with fluorophore tyramide working solution. All sections were sealed with a mixture of 50% glycerol in PBS. The stained sections were observed and images captured using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus FV1000, Japan).

2.7. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as group mean±standard error of the mean (SEM). All data analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.01 software. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to determine overall differences in blood glucose or PWT at each time point. Data comparisons between different groups with one intervention were analyzed with Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA, followed by Newman Keuls multiple comparison tests. P values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Upregulation of P2X7R in the spinal cord of diabetic mice during mechanical allodynia

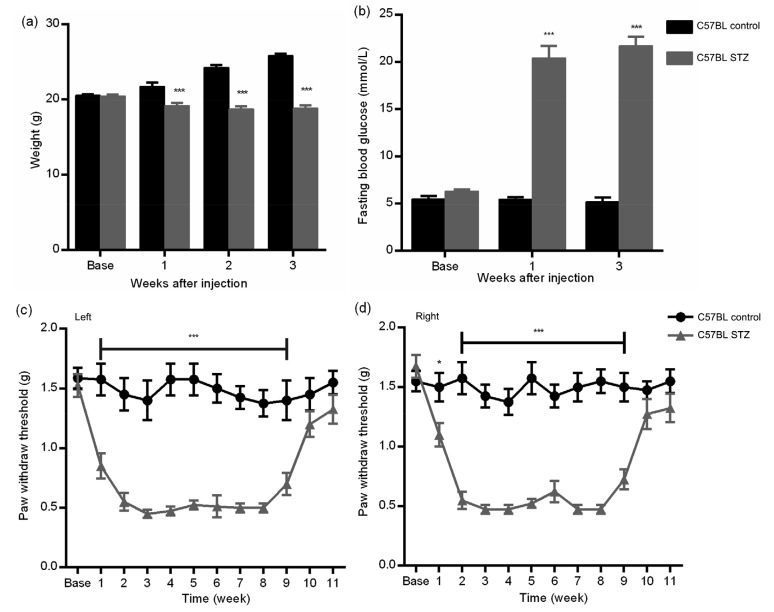

Compared with mice in the control group, the diabetic mice had a significantly lower body weight and higher FBG, indicating that a diabetic model had been established after STZ injection (P<0.001, two-way ANOVA; Figs. 1a and 1b). To avoid bias, the baselines of FBG in the two groups were checked: there was no significant difference between them (diabetic group (6.33±0.51) mmol/L; control group (5.49±0.85) mmol/L). Compared with the control group, the PWTs in the diabetic mice decreased significantly from Weeks 1 to 9 after STZ injection, suggesting increased sensitivity to mechanical stimulation. Furthermore, MA peaked at Week 3 and persisted to Week 8 (Figs. 1c and 1d).

Fig. 1.

Changes in body weight (a), fasting blood glucose (b), and mechanical paw withdrawal threshold (c, d) in diabetic and control mice

C57BL diabetic mice exhibited significant weight loss, much higher fasting blood glucose, hyperglycemia, and mechanical allodynia (Weeks 1–9) compared to control mice. * P<0.05 and *** P<0.001, vs. the control group, at the same time points after streptozotocin (STZ) injection (two-way ANOVA). Data are expressed as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM), n=3

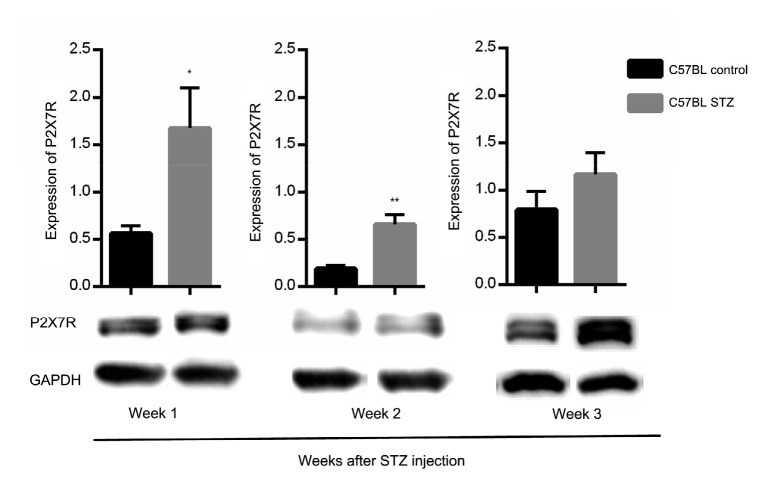

During this period, the expression level of P2X7R protein in the bilateral spinal cord was determined in both groups, and showed upregulation in the diabetic group. In addition, we performed western blotting analysis of P2X7R from Weeks 1 to 3 after STZ injection to determine whether P2X7R was involved in the occurrence of MA and any relationship between them. The results showed that in the dorsal horn the expression level of P2X7R protein increased in the mice in the diabetic group compared with that in the control group in the early stages (Weeks 1–2) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Changes in murine P2X7R expression in different groups

P2X7R protein levels were significantly higher in the dorsal horn of diabetic mice by one and two weeks after streptozotocin (STZ) injection, but no statistically significant difference was detected in Week 3. * P<0.05 and ** P<0.01, vs. control mice, at the same time points after injection (Student’s t-test). Data are expressed as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM), n=3

3.2. Effect of intrathecal injection of selective P2X7R antagonist A740003 on mechanical allodynia in C57BL diabetic mice

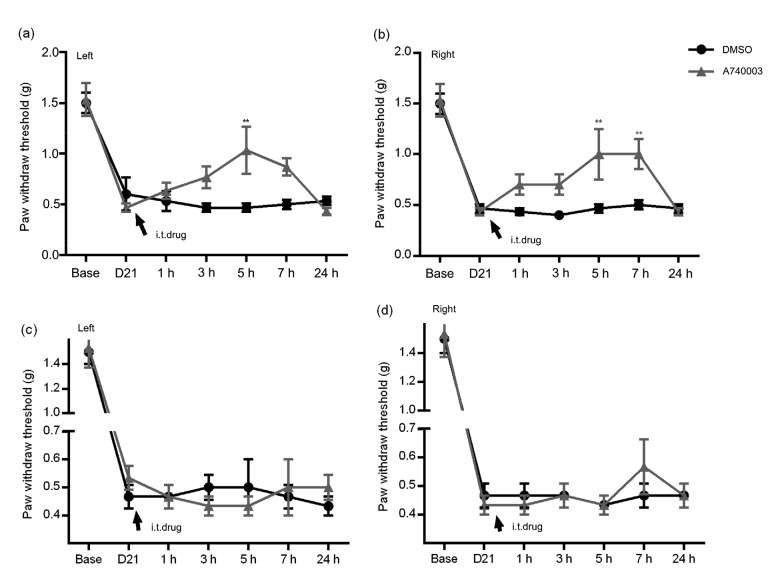

Mice in the diabetic group were randomly divided into two subgroups (diabetic mice treated with A740003; diabetic mice treated with DMSO), each consisting of six mice. The selective P2X7R antagonist A740003 (50 nmol/L×5 μL) was intrathecally injected into mice three weeks after administration of STZ. Then, responses to mechanical stimuli were assessed continuously for 7 h. Results showed that the PWTs of the antagonist group were increased at 3 h and peaked at 5 h, compared with those of the vehicle subgroups. However, after reducing the dose of A740003 (5 nmol/L×5 μL) via acute intrathecal injection, there was no difference in the PWTs between the two subgroups (Fig. 3, two-way ANOVA).

Fig. 3.

Time course and effects of intrathecal injection of A740003 on the paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) of diabetic mice

(a, b) A sufficient intrathecal (i.t.) dose of A740003 significantly increased the PWTs of diabetic mice (i.t. injection of A740003, 50 nmol/L×5 μL). (c, d) A low dose of A740003 produced no difference between the two subgroups (i.t. injection of A740003 (DMSO) 5 nmol/L×5 μL). ** P<0.01, vs. DMSO-treated diabetic mice, two-way ANOVA. Data are expressed as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM), n=3

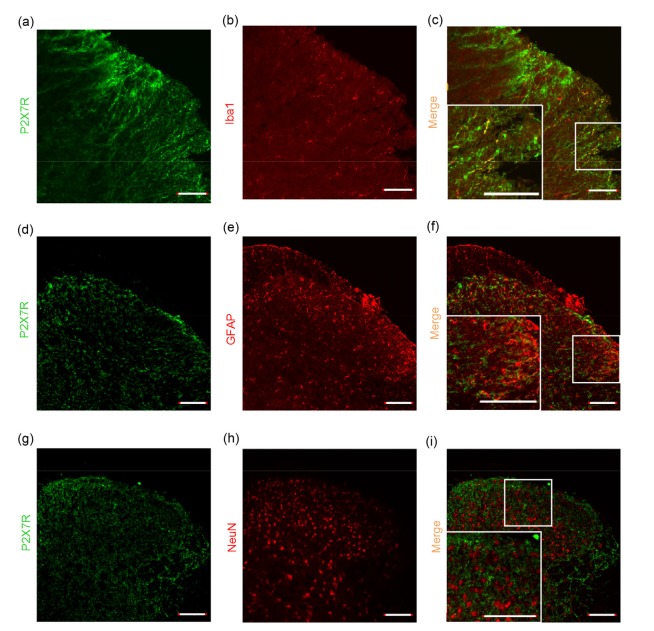

3.3. Cellular localization of P2X7R in the spinal cord of STZ-induced mice

Recent research showed that P2X7R is widely distributed throughout the nervous system in non-diabetic neuropathic pain models and is expressed in the microglia, astrocytes, and neurons in the spinal cord. Double immunofluorescence labeling analysis also demonstrated that most P2X7R-positive cells co-expressed Iba1 (a microglia marker), indicating that it might be expressed mainly in microglial cells of the SDH (Figs. 4a–4c). However, we did not identify any P2X7R-positive cells that were also positive for the astrocytic marker GFAP or neuronal marker NeuN in the SDH (Figs. 4d–4i).

Fig. 4.

Photomicrographs showing localization of P2X7R in the spinal cord of C57BL diabetic mice

Double immunofluorescence labeling shows that P2X7R (green) was predominantly co-localized with Iba1 (a microglial marker, red) (a–c), but not with GFAP (astrocytic marker, red) (d–f) or NeuN (neuronal marker, red) (g–i) in the spinal dorsal horn. Scale bar=100 μm

3.4. Stable performance of allodynia of STZ-induced P2X7R KO mice

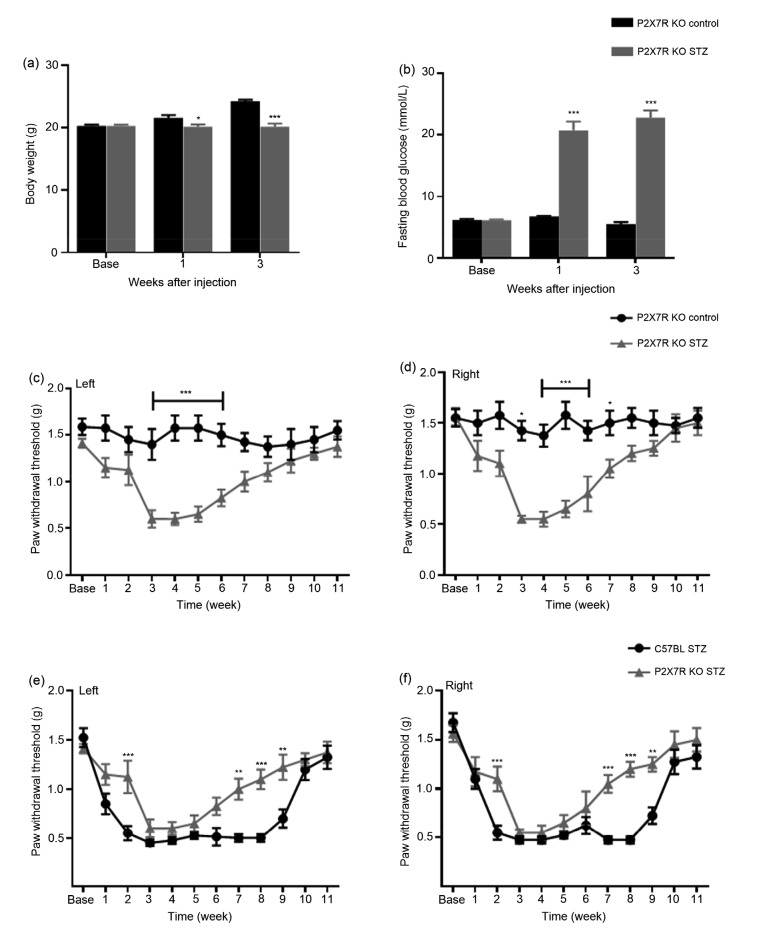

Compared with the control P2X7R KO group, body weight was significantly lower and blood glucose significantly higher in diabetic P2X7R KO mice (Figs. 5a and 5b). The PWTs were significantly lower in diabetic P2X7R KO mice than in control P2X7R KO animals at Week 3 after STZ injection, and were relieved by Week 7 (Figs. 5c and 5d). Also, compared with the C57BL diabetic group, the development of MA in diabetic P2X7R KO mice was delayed and lasted a shorter time (Figs. 5e and 5f). In summary, our results suggest that P2X7R might play an important role in the occurrence of PDN at an early stage.

Fig. 5.

Changes in body weight (a), fasting blood glucose (b), and mechanical paw withdrawal threshold (c–f) in different groups of C57BL and P2X7R KO mice

P2X7R KO diabetic mice exhibited significant weight loss, higher fasting blood glucose levels, hyperglycemia, and mechanical allodynia (3–7 weeks shown at left, and 3–9 weeks at right) compared to control mice. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001, vs. the control group, at the same time (two-way ANOVA). Data are expressed as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM), n=3

4. Discussion

In this work, we demonstrated that P2X7Rs in the spinal cord are involved in the early stages of MA caused by STZ-induced T1DM.

The activation of P2X7R, a non-selective cation channel, could cause an inflow of Na+ and Ca2+ and an outflow of K+ through cell membranes, release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, activation of glial cells, induction of inflammatory reactions, regulation of the release of neurotransmitters, and cell survival, among other effects (Jiang et al., 2016; Lu et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2017; Bernier et al., 2018). Previous studies have implied that P2X7R is involved in different neuropathic models. Liu et al. (2017) demonstrated that P2X7R was upregulated in PDN rats compared with those in a control group. They also showed that with the suppression of CALHM1 expression in the spinal cord, P2X7R was increasingly expressed and that CALHM1 could activate miR-9 to mediate ATP-P2X7R signaling between neurons and glial cells in PDN rat models. In addition, pharmaceutical research showed that expression of P2X7R could be directly inhibited by salidroside, with attenuation of pain-induced behaviors in Zucker diabetic fatty (ZDF) rats (Ni et al., 2017). Liu et al. (2016) also observed that P2X7 mRNA and protein were decreased by lncRNAs NONRATT021972 siRNA through satellite glial cells (SGCs) with reduced MA in T2DM.

After a single high-dose intrathecal injection of selective P2X7R antagonist A740003, we observed a reversal of effects of its induction of MA. Our results are very similar to those found in other models. Ochi-ishi et al. (2014) found that continuous administration of A438079 (another selective P2X7R antagonist) raised the PWTs in paclitaxel-treated rats. Falk et al. (2015) also found that the P2X7R antagonist A839977 dose-dependently attenuated mechanical hypersensitivity in cancer-bearing rats, whereas it had no effect on naive and sham-operated rats. However, they did not observe any significant changes in P2X7R expression among the naive, sham, and cancer-bearing groups at any time point (Days 3, 7, 10, and 14) after surgery, which is different from our results. This indicates that the function of P2X7R might be condition- or time-dependent, and that the underlying mechanism might not be as simple in cancer-bearing animals. In contrast, parallel results in our STZ-induced P2X7R KO mice showed that the development of MA was delayed and was less persistent, suggesting that P2X7 and P2X7R may play roles in the maintenance of DPN. The underlying mechanism of P2X7R’s modulation in the SDH remains to be explored in the future.

Recently, several comprehensive experiments have shown that P2X7R is expressed in astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia in neuronal systems. Using a rat bone cancer model, Huang et al. (2014) reported that P2X7R is expressed mostly in microglia, but not in astrocytes and neurons in the rostral ventromedial medulla (RVM). Zhang et al. (2017) found that P2X7 is co-expressed largely in neurons and presynaptic sites in the neonatal maternal deprivation (NMD) rat model. Furthermore, studies have reported that in a non-diabetic neuropathic pain model, microglial cells in the SDH were activated and released a large number of cytokines such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), nitric oxide (NO), and prostaglandins to activate astrocytes in the dorsal horn (Deuchars et al., 2001; Bele and Fabbretti, 2015; Jiang et al., 2015). Microglia are considered to be involved mainly in the initiation of pain signaling, whereas astrocytes are involved in the maintenance of pain (Deuchars et al., 2001; Bele and Fabbretti, 2015; Jiang et al., 2015). It was also observed that P2X7R expressed mainly in SGCs of the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) is essential for the generation and transmission of neuropathic pain, not only in animal models (Liu et al., 2016), but also in DM patients (Burnstock, 2014; Mehta et al., 2014). However, which types of cell would be mainly responsible for regulating P2X7R in the spinal cord of STZ-induced type 1 diabetic neuropathic mice remained poorly understood. To address this, we used double immunofluorescence labeling analysis and found P2X7R to be expressed primarily in microglial cells of the SDH, indicating that microglial cells could be a candidate therapeutic target in PDN of T1DM.

Taken together, these findings indicate that P2X7R is probably involved in both early stages of STZ-induced type 1 DPN and suggest that antagonism of P2X7R might be useful for analgesic treatment in diabetic patients with neuropathic complications, even in patients suffering from DPN.

Several limitations of this study should be mentioned. First, we chose the time course of observation as Weeks 1–3 to correspond to the early stage of occurrence of MA. A longer time course ought to be examined in future to further explore the role of P2X7Rs in the progression, and especially the maintenance, of STZ-induced MA. Second, deletion of the P2X7R gene might have caused upregulation of other genes to produce a compensatory effect, which may have unavoidably affected our results to some extent. Finally, there are millions of T2DM patients suffering from DPN (He et al., 2017), and the investigation of the mechanisms of P2X7R action in T2DM mice (such as high fat diet-induced mice, ob/ob mice, db/db mice) is urgently required.

Footnotes

Contributors: Cheng-ming NI was responsible for drafting the manuscript, analysis and interpretation of data. He-ping SUN collected and analyzed the data. Xiang XU, Bing-yu LING, and Hui JIN contributed analysis of data and manuscript preparation. Yu-qiu ZHANG and Zhi-qi ZHAO helped perform the analysis with constructive discussions. Hong CAO and Lan XU contributed the conception and design of the current study. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Therefore, all authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity and security of the data.

Project supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81771208 and 81971043), the Health and Family Planning Commission of Wuxi (No. YGZXM1406), the Wuxi Municipal Bureau on Science and Technology (No. CSE31N1614), the Fundamental Research Fund of Wuxi People’s Hospital (No. RKA201720), and the Technology for Social Development Project of Kunshan (No. KS1539), China

Compliance with ethics guidelines: Cheng-ming NI, He-ping SUN, Xiang XU, Bing-yu LING, Hui JIN, Yu-qiu ZHANG, Zhi-qi ZHAO, Hong CAO, and Lan XU declare that they have no conflict of interest.

All institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals were followed.

References

- 1.Bele T, Fabbretti E. P2X receptors, sensory neurons and pain. Curr Med Chem. 2015;22(7):845–850. doi: 10.2174/0929867321666141011195351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger JR, Choi D, Kaminski HJ, et al. Importance and hurdles to drug discovery for neurological disease. Ann Neurol. 2013;74(3):441–446. doi: 10.1002/ana.23997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernier LP, Ase AR, Séguéla P. P2X receptor channels in chronic pain pathways. Br J Pharmacol. 2018;175(12):2219–2230. doi: 10.1111/bph.13957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burnstock G. Purinergic signalling: from discovery to current developments. Exp Physiol. 2014;99(1):16–34. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2013.071951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng KI, Wang HC, Chuang YT, et al. Persistent mechanical allodynia positively correlates with an increase in activated microglia and increased P-p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Eur J Pain. 2014;18(2):162–173. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2013.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chessell IP, Hatcher JP, Bountra C, et al. Disruption of the P2X7 purinoceptor gene abolishes chronic inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Pain. 2005;114(3):386–396. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deuchars SA, Atkinson L, Brooke RE, et al. Neuronal P2X7 receptors are targeted to presynaptic terminals in the central and peripheral nervous systems. J Neurosci. 2001;21(18):7143–7152. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07143.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falk S, Schwab SD, Frøsig-Jorgensen M, et al. P2X7 receptor-mediated analgesia in cancer-induced bone pain. Neuroscience. 2015;291:93–105. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo XX, Wang Y, Wang K, et al. Stability of a type 2 diabetes rat model induced by high-fat diet feeding with low-dose streptozotocin injection. J Zhejiang Univ-Sci B (Biomed & Biotechnol) 2018;19(7):559–569. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1700254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He XF, Wei JJ, Shou SY, et al. Effects of electroacupuncture at 2 and 100 Hz on rat type 2 diabetic neuropathic pain and hyperalgesia-related protein expression in the dorsal root ganglion. J Zhejiang Univ-Sci B (Biomed & Biotechnol) 2017;18(3):239–248. doi: 10.1631/jzus.b1600247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang ZX, Lu ZJ, Ma WQ, et al. Involvement of RVM-expressed P2X7 receptor in bone cancer pain: mechanism of descending facilitation. Pain. 2014;155(4):783–791. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Illes P, Khan TM, Rubini P. Neuronal P2X7 receptors revisited: do they really exist? J Neurosci. 2017;37(30):7049–7062. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3103-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Javed S, Alam U, Malik RA. Burning through the pain: treatments for diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17(12):1115–1125. doi: 10.1111/dom.12535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang K, Zhuang Y, Yan M, et al. Effects of riluzole on P2X7R expression in the spinal cord in rat model of neuropathic pain. Neurosci Lett. 2016;618:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang TF, Hoekstra J, Heng X, et al. P2X7 receptor is critical in α-synuclein-mediated microglial NADPH oxidase activation. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36(7):2304–2318. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobayashi K, Takahashi E, Miyagawa Y, et al. Induction of the P2X7 receptor in spinal microglia in a neuropathic pain model. Neurosci Lett. 2011;504(1):57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu SM, Zou LF, Xie JY, et al. LncRNA NONRATT021972 siRNA regulates neuropathic pain behaviors in type 2 diabetic rats through the P2X7 receptor in dorsal root ganglia. Mol Brain, 9:44. 2016 doi: 10.1186/s13041-016-0226-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu WJ, Ao QY, Guo QL, et al. miR-9 mediates CALHM1-activated ATP-P2X7R signal in painful diabetic neuropathy rats. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54(2):922–929. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-9700-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu WN, Albalawi F, Beckel JM, et al. The P2X7 receptor links mechanical strain to cytokine IL-6 up-regulation and release in neurons and astrocytes. J Neurochem. 2017;141(3):436–448. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehta N, Kaur M, Singh M, et al. Purinergic receptor P2X7: a novel target for anti-inflammatory therapy. Bioorg Med Chem. 2014;22(1):54–88. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miras-Portugal MT, Sebastián-Serrano Á, de Diego García L, et al. Neuronal P2X7 receptor: involvement in neuronal physiology and pathology. J Neurosci. 2017;37(30):7063–7072. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3104-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore RA, Wiffen PJ, Derry S, et al. Gabapentin for chronic neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 3:CD007938. 2011 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007938.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ni GL, Cui R, Shao AM, et al. Salidroside ameliorates diabetic neuropathic pain in rats by inhibiting neuroinflammation. J Mol Neurosci. 2017;63(1):9–16. doi: 10.1007/s12031-017-0951-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ochi-Ishi R, Nagata K, Inoue T, et al. Involvement of the chemokine CCL3 and the purinoceptor P2X7 in the spinal cord in paclitaxel-induced mechanical allodynia. Mol Pain, 10:53. 2014 doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-10-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan Q, Li QM, Deng W, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for peripheral neuropathy in Chinese patients with diabetes: a multicenter cross-sectional study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 9:617. 2018 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pop-Busui R, Boulton AJM, Feldman EL, et al. Diabetic neuropathy: a position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(1):136–154. doi: 10.2337/dc16-2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sánchez-Nogueiro J, Marín-Garcia P, Bustillo D, et al. Subcellular distribution and early signalling events of P2X7 receptors from mouse cerebellar granule neurons. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;744:190–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsuda M, Ueno H, Kataoka A, et al. Activation of dorsal horn microglia contributes to diabetes-induced tactile allodynia via extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase signaling. GLIA. 2008;56(4):378–386. doi: 10.1002/glia.20623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vinik A, Emir B, Cheung R, et al. Relationship between pain relief and improvements in patient function/quality of life in patients with painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy or postherpetic neuralgia treated with pregabalin. Clin Ther. 2013;35(5):612–623. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang DM, Couture R, Hong YG. Activated microglia in the spinal cord underlies diabetic neuropathic pain. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;728:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu B, Peng LC, Xie JY, et al. The P2X7 receptor in dorsal root ganglia is involved in HIV gp120-associated neuropathic pain. Brain Res Bull. 2017;135:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2017.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yao ZY, Chen WB, Shao SS, et al. Role of exosome-associated microRNA in diagnostic and therapeutic applications to metabolic disorders. J Zhejiang Univ-Sci B (Biomed & Biotechnol) 2018;19(3):183–198. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1600490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ying YL, Wei XH, Xu XB, et al. Over-expression of P2X7 receptors in spinal glial cells contributes to the development of chronic postsurgical pain induced by skin/muscle incision and retraction (SMIR) in rats. Exp Neurol. 2014;261:836–843. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang PA, Xu QY, Xue L, et al. Neonatal maternal deprivation enhances presynaptic P2X7 receptor transmission in insular cortex in an adult rat model of visceral hypersensitivity. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2017;23(2):145–154. doi: 10.1111/cns.12663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]