Key Points

Question

Is the detention or deportation of a family member associated with later suicidal ideation, alcohol use, and clinically significant externalizing behaviors among Latino or Latina adolescents?

Findings

In this survey study of 547 Latino or Latina adolescents aged 11 to 16 years, family member detention or deportation occurring during the prior 12 months was associated with significantly higher odds of suicidal ideation in the past 6 months, alcohol use since the prior survey, and a clinical level of externalizing symptoms at the 6-month follow-up survey, controlling for adolescents’ initial mental health and risk behaviors.

Meaning

Current immigration policies may be associated with increased risks for outcomes threatening the health of Latino or Latina adolescents.

Abstract

Importance

Policy changes since early 2017 have resulted in a substantial expansion of Latino or Latina immigrants prioritized for deportation and detention. Professional organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Medical Association, and Society for Research in Child Development, have raised concerns about the potentially irreversible mental health effects of deportations and detentions on Latino or Latina youths.

Objective

To examine how family member detention or deportation is associated with Latino or Latina adolescents’ later mental health problems and risk behaviors.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Survey data were collected between February 14 and April 26, 2018, and between September 17, 2018, and January 13, 2019, and at a 6-month follow-up from 547 Latino or Latina adolescents who were randomly selected from grade and sex strata in middle schools in a suburban Atlanta, Georgia, school district. Prospective data were analyzed using multivariable, multivariate logistic models within a structural equation modeling framework. Models examined how family member detention or deportation within the prior 12 months was associated with later changes in suicidal ideation, alcohol use, and clinical externalizing symptoms, controlling for initial mental health and risk behaviors.

Exposure

Past-year family member detention or deportation.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Follow-up reports of suicidal ideation in the past 6 months, alcohol use since the prior survey, and clinical level of externalizing symptoms in the past 6 months.

Results

A total of 547 adolescents (303 girls; mean [SD] age, 12.8 [1.0] years) participated in this prospective survey. Response rates were 65.2% (547 of 839) among contacted parents and 95.3% (547 of 574) among contacted adolescents whose parents provided permission. The 6-month follow-up retention rate was 81.5% (446 of 547). A total of 136 adolescents (24.9%) had a family member detained or deported in the prior year. Family member detention or deportation was associated with higher odds of suicidal ideation (38 of 136 [27.9%] vs 66 of 411 [16.1%]; adjusted odds ratio, 2.37; 95% CI, 1.06-5.29), alcohol use (25 of 136 [18.4%] vs 30 of 411 [7.3%]; adjusted odds ratio, 2.98; 95% CI, 1.26-7.04), and clinical externalizing behaviors (31 of 136 [22.8%] vs 47 of 411 [11.4%]; adjusted odds ratio, 2.76; 95% CI, 1.11-6.84) at follow-up, controlling for baseline variables.

Conclusion and Relevance

This study suggests that recent immigration policy changes may be associated with critical outcomes jeopardizing the health of Latino or Latina adolescents. Since 95% of US Latino or Latina adolescents are citizens, compromised mental health and risk behavior tied to family member detention or deportation raises concerns regarding the association of current immigration policies with the mental health of Latino and Latina adolescents in the United States.

This survey study examines whether family member detention or deportation is associated with Latino or Latina adolescents’ later mental health problems and risk behaviors.

Introduction

Since early 2017, the US government has implemented or announced policy changes limiting the rights and benefits for Latino and Latina immigrants, including those authorized to live in the US. Some executive orders have reduced access to due process and substantially expanded the number of immigrants prioritized for deportation or held in detention.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 As stated by Morey,2 immigration policy is, de facto, public health policy, with deportations and detentions serving as critical mechanisms via which anti-immigrant policies and rhetoric exacerbate existing racial and ethnic health disparities and violate public health principles. Deportations and detentions resulting in family separations may be particularly damaging to the 5.9 million children who are US citizens living with a family member who is undocumented.9,10,11 Concern about the potentially irreversible mental health effects of deportations and detentions on youths has been noted by organizations including the American Academy of Pediatrics,12 the American Medical Association,13 and the Society for Research in Child Development.14 The present study examines prospective associations between a family member’s past-year detention or deportation and changes in US Latino or Latina adolescents’ later risk for suicidal ideation, alcohol use, and clinically significant externalizing symptoms (ie, outward-directed problem behaviors, including aggression and rule breaking).

Although separation from primary caregivers is costly to the health of young children, family member deportation or detention may be uniquely traumatic for older youths.15 Adolescents’ advanced sociocognitive skills,16,17,18 media exposure,19 and inclusion in family conversations about immigration enforcement facilitate comprehension of detentions and deportations in ways that are more complex and salient than what occurs for younger children.16 Adolescents can perceive detentions and deportations as a function of broader environmental threats, such as structural racism,20 and may experience family separation as a trauma associated not just with themselves, but also with the person detained or deported and other family members.4 These threats to perceived safety and security can serve as an important social determinant of adolescent mental health problems and risk-taking behaviors.1,2,9,11,16

Existing research, although not specifically associated with adolescents, informs the present investigation. A small number of cross-sectional study findings of Latino or Latina populations have shown that a parent’s detention or deportation is associated with 8- to 15-year-old children reporting higher depressive symptoms,15,16 parents reporting more trauma and internalizing and externalizing symptoms among their preadolescent children,21,22 and clinicians reporting greater dysfunction among 6- to 12-year old children.22 These difficulties may be more acute in the contemporary immigration climate owing to law enforcement efforts increasingly targeting immigrants with families.3 The present study addresses the need for longitudinal study designs focusing on adolescents and the current immigration climate and expanding the focus beyond parents to include the larger family system. The latter shift is especially important owing to familism, a Latino cultural value emphasizing the primacy of family solidarity.23,24

Identifying correlates of risk behaviors and mental health problems during early and middle adolescence is essential to prevention efforts aimed at improving health across the life course.25,26 Young people with a diagnosis of an externalizing disorder (eg, conduct disorder) at 15 years of age face heightened risks for a substance abuse disorder at 20 years of age.27 Those experiencing suicidal ideation by 16 years of age are at increased risk for anxiety disorders, suicidal thoughts and behaviors, and poor social, health, and financial functioning during adulthood.28 Youths who use alcohol during early and middle adolescence are more likely than others to experience later alcohol use and other drug use in adolescence and beyond and to develop alcohol use disorders in adulthood.29,30,31 Adolescent risk behaviors more generally also are associated with myriad health risks and psychosocial difficulties into adulthood.32,33

This study examines how family member detention or deportation is associated with Latino or Latina adolescents’ later risk behaviors and mental health problems. Participants reported on past-year detentions and deportations, which occurred as early as February 2017, a time period that matches precisely to major immigration policy shifts and transitions. We hypothesized that a family member’s detention or deportation would be associated with higher odds of adolescents’ suicidal ideation, alcohol use, and clinically significant level of externalizing behavior.

Methods

Procedures and Sampling

Data are derived from Pathways to Health/Caminos al Bienestar, a longitudinal study of Latino and Latina adolescents and their mothers in suburban Atlanta, Georgia. The ethnic label Latino or Latina is used owing to community stakeholders’ preference for this label and their perception that Latinx was not well recognized in the target population. We recognize that some participants may have preferred other label choices, including Latinx, a specific heritage (eg, Columbian), or combined labels (eg, Mexican American). Details on sampling, recruitment, and retention are provided in eMethods 1 and eFigures 1 and 2 in the Supplement. To ensure family, school, and community heterogeneity, adolescents were selected from school clusters defined by a low (<13%), moderate (18%-25%), or high (>40%) concentration of Latino and Latina students. Among all middle schools in 1 school district, the Pathways to Health/Caminos al Bienestar study omitted 8.6% of schools in the low cluster owing to an insufficient number of Latino and Latina students for sampling; 13.0% of schools in the low cluster owing to school disinterest; and 17.4% of schools in the moderate cluster, in which the percentage of Latino and Latina students was near the low to moderate or moderate to high cutpoints, preventing clear distinction between clusters. The Pathways to Health/Caminos al Bienestar initially selected all students listed as Hispanic on 2017-2018 middle school enrollment lists to screen for eligibility. A total of 1105 students were then selected at random, stratifying by grade (sixth, seventh, and eighth) and sex from schools and evenly distributed across low (<13%), moderate (18%-25%), or high (>40%) concentration clusters of Latino and Latina students. Exclusion criteria included having a severe emotional or learning disability indicated by an Individualized Education Plan, being unable to read either English or Spanish, self-reporting not being Latino or Latina (or a related term), being a sibling of a previously selected participant, or having an age outside the typical range for the school grade. Investigators obtained a certificate of confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health and institutional review board approval from The George Washington University. Parents provided oral or written consent; adolescents provided written assent.

Of the 845 parents who were contacted and indicated that the adolescent was eligible, 658 provided permission for the adolescent to be contacted. Among these 658 parents, 574 adolescents could be reached and confirmed eligibility, and 547 adolescents provided assent and were enrolled. Response rates are based on the reachable parents and adolescents because eligibility could not be determined without this contact. After an additional 6 adolescents were determined to be ineligible, the response rate among eligible adolescents whose parents were contacted and provided permission was 65.2% (547 of 839 parents), and the response rate among eligible adolescents contacted was 95.3% (547 of 574 parents). The 6-month follow-up retention rate was 81.5% (446 of 547 adolescents).

Because the school district unexpectedly requested an end to in-school data collection by May 1, 2018, 422 of 547 baseline surveys (77.1%) were completed from February 14 to April 26, 2018 (the main sample), and 125 of 547 (22.9%) were completed from September 17, 2018, through January 13, 2019 (the lagged sample). All adolescents completed surveys on a computer, tablet, or mobile phone using the Qualtrics XM Research Core Survey Software program. Any survey completed prior to May 1, 2018, was self-administered at school. A small proportion of main sample surveys (completed May and June 2018), all lagged sample surveys, and all follow-up surveys were completed online during the adolescents’ own time, rather than at school, which was accomplished by the research team mailing youths a packet of information, including an electronic link to the survey.

All study materials were provided in Spanish and English. For materials not already translated into Spanish, we translated using the double-translation and double back-translation method combined with a review team approach.34

Measures

Control Variables

The baseline control variables assessing demographic characteristics included adolescent age in years, sex (female or male), place of birth (born in a Latin American or non–Latin American country or born in the US), maternal educational level (less than a high school degree or at least a high school degree), and Latino and Latina student concentration in the school (low, moderate, or high). The parenting control variables included parental support35 and parent-child conflict36 (eMethods 3 in the Supplement).

Family Member Detention or Deportation

At baseline, adolescents indicated whether, during the prior 12 months, a mother, father, stepmother, stepfather, grandparent, uncle, aunt, brother, sister, or other family member had been deported outside the US and/or held in a detention center. Responses were used to create a variable indicating that a family member had been detained or deported in the past year (eMethods 3 in the Supplement).

Adolescent Mental Health and Risk Behavior

The baseline assessments included a 30-item measure of the past 6 months of externalizing symptoms (α = .88), composed of rule breaking and aggressive behavior subscales from the Youth Self-Report 11-1837; a 29-item measure of the past 6 months of internalizing symptoms (α = .93), composed of anxious and depressive, withdrawn and depressed, and somatic syndromes from the Youth Self-Report37; and 1 item assessing lifetime alcohol use38 (eMethods 3 in the Supplement).

The outcome variables assessed at the follow-up survey included the occurrence in the past 6 months of a clinical level of externalizing symptoms in adolescents, determined by a t score of at least 64 (vs <64); the occurrence of suicidal ideation in the past 6 months, indicated by a response of “sometimes true” or “often or always” (vs “not true”) to the Youth Self-Report item: “I think about killing myself”37; and alcohol use since the prior survey, indicated by a response of at least “1 to 2 times” (vs “never”) to the question: “how many times have you had more than just a few sips of alcohol?”38 (eMethods 3 in the Supplement).

Statistical Analysis

Missing data due to survey nonresponse at follow-up was 18.5% (101 of 547). Missing data due to item nonresponse ranged from 1.5% (8 of 547) to 4.6% (25 of 547), with the exception of maternal educational level, which was missing for 16.1% of participants (88 of 547). Data missing due to item nonresponse were presumed to be missing completely at random based on no correlation with other study variables. Data missing due to attrition were considered to be missing at random based on results from attrition analyses. These results indicated no significant differences in attrition by place of birth, age, or maternal educational level and no attrition differences in the levels of internalizing symptoms or parental support. However, a higher proportion of boys (vs girls) and of youths reporting baseline alcohol use (vs not) were lost to attrition; adolescents lost to attrition reported significantly higher levels of parent-child conflict and externalizing behaviors than those who were retained.

To address the missing data, univariate and bivariate analyses were conducted using a grand mean data set of averaged estimates for missing data calculated across 200 multiply imputed data sets. In analyses conducted using structural equation models (SEMs), missing data were handled using a full information maximum likelihood estimation. By the inclusion of an auxiliary variable for “follow-up survey nonresponse” in the full information maximum likelihood estimation, SEM analyses accounted for any differential patterns due to attrition (eMethods 2 and eTable 2 in the Supplement).39

Statistical tests were 2-sided; the χ2 and t tests of significance were used to examine differences in family member detention or deportation by covariates and adolescent outcomes. P < .01 was used to determine statistical significance for χ2 tests owing to the sensitivity of this test for large sample sizes. Confirmatory factor analysis was used to determine the construct validity for latent measures of baseline internalizing and externalizing symptoms, parental support, and parent-child conflict (eMethods 4 and eTable 3 in the Supplement). Simple and multivariable, multivariate logistic regression models within a SEM framework were used to examine how detention and deportation were associated with the odds of suicidal ideation, clinical externalizing symptoms, and alcohol use at the 6-month follow-up. Longitudinal pathways from detention or deportation to clinical externalizing, alcohol use, and suicidal ideation were estimated simultaneously and adjusted for baseline externalizing symptoms, lifetime alcohol use, and internalizing symptoms. This approach models the change in outcomes over time. Owing to sex differences in adolescent responses to family processes and environmental threats,40,41,42,43 we examined differences in the pathways associating detention or deportation with outcomes between boys and girls. Analytic models adjusted for potential confounders (parental support, parent-child conflict, age, place of birth, and maternal educational level), which may covary with immigration enforcement.44,45 Fit statistics for binary outcomes include the log likelihood, the Akaike information criterion, and the bayesian information criterion (eMethods 5 in the Supplement).46,47

Results

Participants were mostly born in the US (482 [88.1%]) and included a higher proportion of girls (303 [55.4%]) than boys (244 [44.6%]) (Table 1). The mean (SD) age of participants at baseline was 12.8 (1.0) years. Among non–US-born adolescents, the mean (SD) length of time living in the US was 6.0 (4.4) years. More than half of adolescents (331 [60.5%]) reported that their mother had completed high school. Approximately half of mothers (280 of 547 [51.2%]) were born in Mexico, 82 of 547 (15.0%) were born in the US, and the remaining were born in countries in Central America (66 of 547 [12.1%]), South America (67 of 547 [12.2%]), other Latin American countries (37 of 547 [6.8%]), or non–Latin American countries (15 of 547 [2.7%]). For a descriptive comparison of the Latino or Latina adolescents in the study sample with Latino or Latina adolescents younger than 18 years of age in metropolitan Atlanta, Georgia, and in the US, see eTable 1 in the Supplement.

Table 1. Study Variables at Baseline.

| Baseline Study Variable | Family Member Detained or Deported, No. (%) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 411) | Yes (n = 136) | Total (N = 547) | ||

| Adolescent male sex | 190 (46.2) | 54 (39.7) | 244 (44.6) | .19 |

| Adolescent age, mean (SD), ya | 12.8 (1.0) | 12.9 (1.1) | 12.8 (1.0) | .24 |

| Adolescent born in the US | 358 (87.1) | 124 (91.2) | 482 (88.1) | .20 |

| Mother with ≥ high school education | 265 (64.5) | 66 (48.5) | 331 (60.5) | .001 |

| School concentration of Latino and Latina students | ||||

| Low (<13%) | 134 (32.6) | 19 (14.0) | 153 (28.0) | <.001 |

| Moderate (18%-25%) | 144 (35.0) | 42 (30.9) | 186 (34.0) | .38 |

| High (>40%) | 133 (32.4) | 75 (55.1) | 208 (38.0) | <.001 |

| Parental support, mean (SD)b | 4.09 (0.84) | 3.91 (0.93) | 4.05 (0.86) | .04 |

| Parent-child conflict, mean (SD)b | 2.53 (0.87) | 2.78 (0.86) | 2.59 (0.87) | .004 |

| Internalizing symptoms in past 6 mo, mean (SD)c | 12.64 (9.88) | 16.93 (11.53) | 13.71 (10.47) | <.001 |

| Lifetime alcohol use | 61 (14.8) | 36 (26.5) | 97 (17.7) | .002 |

| Externalizing symptoms in past 6 mo, mean (SD)d | 8.41 (6.83) | 11.63 (8.16) | 9.21 (7.31) | <.001 |

Age range, 11 to 16 years.

Range of scores, 1 to 5.

Range of scores, 0 to 54.

Range of scores, 0 to 42.

A total of 136 adolescents (24.9%) reported at baseline that a family member had been detained or deported in the past 12 months, a period beginning as early as February 2017 (Table 1). Compared with adolescents not reporting a detention or deportation, a significantly lower proportion of those reporting detention or deportation had a mother with at least a high school education (66 of 547 [48.5%] vs 265 of 547 [64.5%]), and a significantly higher proportion attended a school with a high (vs low or moderate) Latino and Latina student concentration (75 of 136 [55.1%] vs 133 of 411 [32.4%]) and had used alcohol by the time of the baseline survey (36 of 136 [26.5%] vs 61 of 411 [14.8%]). Adolescents reporting family member detention or detainment also reported less parental support (mean [SD] score, 3.91 [0.93] vs 4.09 [0.84]; range, 1-5) and higher levels of parent-child conflict (mean [SD] score, 2.78 [0.86] vs 2.53 [0.87]; range, 1-5), internalizing symptoms (mean [SD] score, 16.93 [11.53] vs 12.64 [9.88]; range, 0-54), and externalizing symptoms (mean [SD] score, 11.63 [8.16] vs 8.41 [6.83]; range, 0-42) than did other adolescents.

Family member detention or deportation was associated with worse adolescent outcomes at the time of the follow-up survey (Table 2). Compared with adolescents who did not report a detention or deportation in the past 6 months, those who did were more likely to report suicidal ideation in the past 6 months (38 of 136 [27.9%] vs 66 of 411 [16.1%]; odds ratio, 2.63; 95% CI, 1.43-4.82), a clinical level of externalizing symptoms in the past 6 months (31 of 136 [22.8%] vs 47 of 411 [11.4%]; odds ratio, 2.79; 95% CI, 1.40-5.56), and alcohol use since the prior survey (25 of 136 [18.4%] vs 30 of 411 [7.3%]; odds ratio, 3.12; 95% CI, 1.54-6.30). These results did not account for change over time.

Table 2. Prevalence of Adolescent Outcomes at Follow-up by Baseline Report of Family Member Detained or Deported.

| Outcome | Baseline Report of Family Member Detained or Deported, No. (%) | OR (95% CI)a | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 411) | Yes (n = 136) | |||

| Suicidal ideation in past 6 mo | 66 (16.1) | 38 (27.9) | 2.63 (1.43-4.82) | .002 |

| Alcohol use since baseline | 30 (7.3) | 25 (18.4) | 3.12 (1.54-6.30) | <.001 |

| Clinical externalizing symptoms in past 6 mo | 47 (11.4) | 31 (22.8) | 2.79 (1.40-5.56) | .001 |

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

Odds ratio for outcome by exposure to family member detention or deportation.

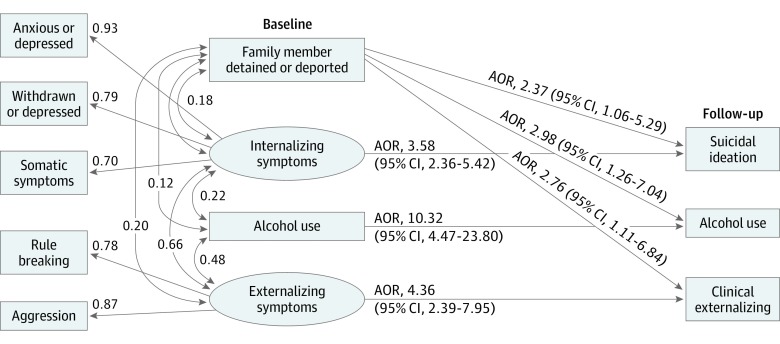

Multivariable, multivariate SEM results modeling rank-order change in outcomes over time are illustrated in the Figure. Family member detention or deportation at baseline was associated with a 2-fold to 3-fold higher odds of suicidal ideation (adjusted odds ratio, 2.37; 95% CI, 1.06-5.29), alcohol use (adjusted odds ratio, 2.98; 95% CI, 1.26-7.04), and clinical externalizing behaviors (adjusted odds ratio, 2.76; 95% CI, 1.11-6.84) at the 6-month follow-up, above and beyond the effects of earlier syndromes and all other study variables (Figure). Additional details on SEM results are provided in the Figure and eTable 4 in the Supplement. The validity of these findings was strengthened by the results from sensitivity analyses indicating that estimates for the pathways associating detention or deportation with outcomes were similar in models excluding the 18.5% of adolescents lost to follow-up, excluding the 22.8% of adolescents born outside the US, and adjusting for reports that a family member was detained or deported after the baseline survey (eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Figure. Family Member Detention or Deportation at Baseline and Latino or Latina Adolescent Mental Health and Risk Behavior at the 6-Month Follow-up.

Standardized coefficients reported for factor loadings to latent constructs, which are indicated by ovals (observed variables indicated by rectangles), and for associations among baseline study variables. Adjusted odds ratio (AOR) controls for baseline adolescent age, sex, place of birth; maternal educational level; parental support; parent-child conflict; Latino and Latina student concentration in the school; and follow-up survey nonresponse. All factor loadings and correlations at baseline were statistically significant at P < .001, with the exception of the baseline alcohol use and detention or deportation correlation, which was significant at P = .006. Model fit: log likelihood = −6842.576; Akaike information criterion = 13981.152; and bayesian information criterion = 14618.211.

Discussion

Presidential executive orders leading to increases in the number of Latino and Latina immigrants detained or deported3,4 signal a critical need to understand how the immigration enforcement that has occurred since early 2017 has been associated with the mental health of US Latino and Latina youths.9 One in every 4 adolescents in this sample reported that a parent, grandparent, uncle, aunt, sibling, or other relative had been held in a detention center or deported from the US during the prior year. From a policy perspective, the time frame of reported detentions and deportations is critical; in 2017 alone, President Trump announced plans to construct a border wall between the US and Mexico, end the Temporary Protected Status and Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals programs, and increase deportation enforcement in the interior of the country.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 Our results suggest that the familial consequences of these immigration policies are associated with increased adolescent risks for suicidal ideation, alcohol use at a young age, and a clinical level of externalizing symptoms. Because suicide, drug overdose, and alcohol abuse are key factors associated with the 2014 to 2017 decreases in US life expectancy, this study’s findings raise concerns that current immigration policies may be associated with midlife mortality.48

Several unique study features underscore the importance of immigration policy to the health of the Latino and Latina population. Consistent with extant research,49,50 anti-immigrant policies targeting some immigrant groups appear to have a negative spillover for Latino and Latina adolescents who are US citizens. Even when limiting analyses to the 88.1% of adolescents born in the US, family member detention or deportation was associated with increases in serious mental health problems and risk behaviors. Furthermore, the significant increases shown for later odds of suicidal ideation, alcohol use, and a clinical level of externalizing symptoms were evident even after adjusting for mental health and behavioral risks associated with detention or deportation at baseline. As shown by the trauma literature, disruptions to family resources and routines conferred by a family member’s detention or deportation may be associated with a continued decline in well-being with the passage of time.51 Finally, evidence for serious risks during the early and middle adolescent years has implications for dropping out of school, criminal activity, and suicidality occurring later in life.28,29,30,31,32,33 In summary, our findings suggest that current immigration policies may be associated with immediate and severe health risks for Latino and Latina individuals who are US citizens during an especially sensitive period of development, raising concerns about the potentially irreversible mental health effects of deportations and detentions on Latino and Latina youths enduring into adulthood.51,52,53

Processes unique to early adolescence and Latino and Latina culture likely exacerbate any trauma associated with a family member’s detention or deportation.51,54 Early adolescence is a highly sensitive developmental period during which environmental stress has been reported to have profound consequences for physiological changes, elevating later health risks.51 Exposure to trauma, for example, has been shown to be especially harmful when occurring at 10 years of age, as indicated by changes in brain structure and activity and the development of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms.51 Normative gains in behavioral autonomy also may increase Latino and Latina adolescents’ level of exposure to media coverage depicting anti-immigrant events, level of inclusion in family conversations regarding threats to safety, and experiences of discrimination.17,18,19 These exposures, coupled with adolescents’ advanced cognitive skills, facilitate awareness of xenophobia and Latino and Latina marginalization, potentially enhancing harmful effects of a family member’s detention or deportation.15,18,20 Immigration-related adversity for Latino and Latina adolescents may be further aggravated by threats to familism, a cultural value rendering family needs as a priority over those of the needs of the individual.23,24 Adolescents who experience a family member’s detention or deportation likely experience adversities extending far beyond the outcomes assessed in the present study. The potential consequences of detention or deportation include income loss, housing instability, food hardship, interrupted schooling, worry about family members, perceptions of an uncertain future, societal marginalization, and social isolation or withdrawal, all of which compromise adolescent identity formation, peer relationships, and educational aspirations.45,49,55,56,57

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths. In addition to sensitivity analyses supporting the stability of key findings, analytic models helped counter possible selection bias by statistically controlling for demographic characteristics, parenting processes, and baseline internalizing and externalizing symptoms and lifetime alcohol use. The random sample of adolescents in a large and socioeconomically diverse, suburban school district reduces sampling bias and increases generalizability. Finally, our results may represent conservative estimates for the consequences of deportation or detention because baseline measures assessed detention or deportation within the prior 12 months but assessed externalizing and internalizing symptoms within the prior 6 months. Some consequences of detention or deportation may have occurred prior to the baseline survey—a possibility supported by positive correlations between detention or deportation and baseline indicators of adolescent risk and mental health problems. In addition, adolescent fears of immigration enforcement prior to the initial survey may have compromised mental health prior to an actual detainment or deportation.1,2,57 Thus, the association of a deportation or detention in the past year with adolescent outcomes was shown above and beyond events occurring prior to the assessment of the past 6 months of baseline externalizing and internalizing symptoms.

This study’s contributions to knowledge about the association of family member detention or deportation with Latino or Latina adolescents’ later risks of suicidal ideation, alcohol use, and externalizing problems are tempered by some limitations. First, despite the prospective design that substantially advances beyond extant cross-sectional studies on this topic,15,16,21,22 this research conveys nothing about longer-term consequences of detention or deportation. Prior research suggests, however, that this trauma has enduring adverse effects on nervous, endocrine, and immune systems.51,53,58,59,60 Second, this study is limited by self-reporting bias in associations among variables and the correlation design, limiting causal interpretations despite the longitudinal data. The lack of a specific date for the detention or deportation further limits our knowledge regarding associations between these events and adolescent outcomes. A third limitation concerns the sample size, which did not permit comparing outcomes for youths experiencing a family member’s detention vs deportation, the detention or deportation of a parent vs other relative, or the detention or deportation of 1 family member vs multiple family members. Finally, the difficulty in contacting families to obtain parental permission resulted in a 65.2% overall response rate, limiting the generalizability of findings to families who are more difficult to reach.

Conclusions

In response to calls made by professional organizations,12,13,14 this research documents potential violations of public health principles and indicates how immigration policies may be exacerbating existing health disparities.2 The prospective study findings for a random sample of adolescents in a large metropolitan area elucidate health-compromising experiences occurring during a historic period marked by numerous anti-immigrant executive orders and actions. As stated by Morey,2 public health has a moral responsibility to combat xenophobia through practice, policy, and research activities. Our findings indicate a critical need for mental health and social support services that can mitigate the stress and trauma facing Latino and Latina teenagers in the US, most of whom are citizens. Health care professionals and school personnel must therefore identify and support Latino and Latina youths whose parents, uncles, aunts, grandparents, siblings, or other relatives are at risk of being held in a detention center or deported from the US. As shown in this research, contemporary immigration enforcement may be jeopardizing the health and well-being of future generations of US citizens.

eMethods 1. Sampling Procedures & Response Rates

eMethods 2. Missing Data

eMethods 3. Survey Items

eMethods 4. Measurement Models: Analytic Plan

eMethods 5. Structural Equation Models: Analytic Plan

eTable 1. Demographic Characteristics of Latino/as: US, Metro Atlanta, and the Study Sample

eTable 2. Baseline Study Variables by Participants Lost to Follow-up

eTable 3. Measurement Model: Parameter Estimates

eTable 4. Multivariate Logistic Structural Model Parameter Estimates

eTable 5. Sensitivity Analyses

eFigure 1. Flow Chart Describing Sampling Design and Characteristics

eFigure 2. Flow Chart Describing Response Rate

References

- 1.Barajas-Gonzalez RG, Ayón C, Torres F. Applying a community violence framework to understand the impact of immigration enforcement threat on Latino children. Soc Policy Rep. 2018;31(3):1-24. doi: 10.1002/sop2.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morey BN. Mechanisms by which anti-immigrant stigma exacerbates racial/ethnic health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(4):460-463. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Immigration Council. Cantor G, Ryo E, Humphrey R Changing patterns of interior immigration enforcement in the United States, 2016-2018. Updated July 1, 2019. Accessed August 7, 2019. http://americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/interior-immigration-enforcement-united-states-2016-2018

- 4.Gostin LO, Ó Cathaoir KE. Presidential immigration policies: endangering health and well-being? JAMA. 2017;317(16):1617-1618. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.3794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Citizenship and Immigration Services. Temporary protected status. Updated November 11, 2017. Accessed December 14, 2017. https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/temporary-protected-status

- 6.US Department of Homeland Security. Acting Secretary Elaine Duke announcement on Temporary Protected Status for Nicaragua and Honduras. Updated November 20, 2017. Accessed September 5, 2019. https://www.dhs.gov/news/2017/11/06/acting-secretary-elaine-duke-announcement-temporary-protected-status-nicaragua-and

- 7.US Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Fiscal year 2017 ICE enforcement and removal operations report. Accessed December 21, 2017. https://www.ice.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Report/2017/iceEndOfYearFY2017.pdf

- 8.US Citizenship and Immigration Services Consideration of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). Accessed December 21, 2017. https://www.uscis.gov/archive/consideration-deferred-action-childhood-arrivals-daca

- 9.Eskenazi B, Fahey CA, Kogut K, et al. . Association of perceived immigration policy vulnerability with mental and physical health among US-born Latino adolescents in California [published online June 24, 2019]. JAMA Pediatr. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Center for American Progress. Mathema S. Keeping families together: why all Americans should care about what happens to unauthorized immigrants. Updated March 16, 2017. Accessed July 18, 2019. https://cdn.americanprogress.org/content/uploads/2017/03/15112450/KeepFamiliesTogether-brief.pdf

- 11.Wood LCN. Impact of punitive immigration policies, parent-child separation and child detention on the mental health and development of children. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2018;2(1):e000338. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2018-000338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Academy of Pediatrics. Stein F. AAP statement on protecting immigrant children. Updated January 25, 2017. Accessed August 8, 2019. https://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-press-room/Pages/AAPStatementonProtectingImmigrantChildren.aspx

- 13.American Medical Association AMA adopts new policies to improve health of immigrants and refugees. Updated June 12, 2017. Accessed August 8, 2019. https://www.ama-assn.org/press-center/press-releases/ama-adopts-new-policies-improve-health-immigrants-and-refugees

- 14.Society for Research in Child Development. Bouza J, Camacho-Thompson DE, Carlo G, et al. The science is clear: separating families has long-term damaging psychological and health consequences for children, families, and communities. Updated June 20, 2018. Accessed August 8, 2019. https://www.srcd.org/policy-media/statements-evidence/separating-families

- 15.Zayas LH, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Yoon H, Rey GN. The distress of citizen-children with detained and deported parents. J Child Fam Stud. 2015;24(11):3213-3223. doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0124-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giano Z, Anderson M, Shreffler KM, Cox RB, Merten MJ, Gallus KL. Immigration-related arrest, parental documentation status, and depressive symptoms among early adolescent Latinos. [published online August 1, 2019]. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2019. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroger J. Identity Development: Adolescence Through Adulthood. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smetana JG, Villalobos M. Social cognitive development in adolescence In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, eds. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. 3rd ed Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2009:187-228. doi: 10.1002/9780470479193.adlpsy001008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tynes BM, Willis HA, Stewart AM, Hamilton MW. Race-related traumatic events online and mental health among adolescents of color. J Adolesc Health. 2019;65(3):371-377. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gee GC, Walsemann KM, Brondolo E. A life course perspective on how racism may be related to health inequities. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):967-974. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen BA, Cisneros EM, Tellez A. The children left behind: the impact of parental deportation on mental health. J Child Fam Stud. 2015;24(2):386-392. doi: 10.1007/s10826-013-9848-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rojas-Flores L, Clements ML, Hwang Koo J, London J. Trauma and psychological distress in Latino citizen children following parental detention and deportation. Psychol Trauma. 2017;9(3):352-361. doi: 10.1037/tra0000177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calzada EJ, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Yoshikawa H. Familismo in Mexican and Dominican families from low-income, urban communities. J Fam Issues. 2013;34(12):1696-1724. doi: 10.1177/0192513X12460218 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stein GL, Cupito AM, Mendez JL, Prandoni J, Huq N, Westerberg D. Familism through a developmental lens. J Lat Psychol. 2014;2(4):224-250. doi: 10.1037/lat0000025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graber JA, Sontag LM. Internalizing problems during adolescence In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, eds. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology 3rd ed Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2009:642-682. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farrington DP. Conduct disorder, aggression, and delinquency In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, eds. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. 3rd ed Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2009:683-722. doi: 10.1002/9780470479193.adlpsy001021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tartter M, Hammen C, Brennan P. Externalizing disorders in adolescence mediate the effects of maternal depression on substance use disorders. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2014;42(2):185-194. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9786-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Copeland WE, Goldston DB, Costello EJ. Adult associations of childhood suicidal thoughts and behaviors: a prospective, longitudinal analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(11):958-965. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sartor CE, Jackson KM, McCutcheon VV, et al. . Progression from first drink, first intoxication, and regular drinking to alcohol use disorder: a comparison of African American and European American youth. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40(7):1515-1523. doi: 10.1111/acer.13113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackson KM, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Rogers ML. The prospective association between sipping alcohol by the sixth grade and later substance use. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2015;76(2):212-221. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schulenberg JE, Maslowsky J, Maggs JL, Zucker R. Development matters: taking the long view on substance use during adolescence and the transition to adulthood In: Colby SM, Tevyaw T, Monti PM, eds. Adolescents, Alcohol, and Substance Abuse: Reaching Teens Through Brief Intervention. 2nd ed New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2018:13-49. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dodge KA, Malone PS, Lansford JE, Miller S, Pettit GS, Bates JE. A dynamic cascade model of the development of substance-use onset. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2009;74(3):vii-119. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2009.00528.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masten AS, Roisman GI, Long JD, et al. . Developmental cascades: linking academic achievement and externalizing and internalizing symptoms over 20 years. Dev Psychol. 2005;41(5):733-746. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knight GP, Roosa MW, Umaña-Taylor AJ. Sampling, recruiting, and retaining diverse samples In: Knight B, Roosa MW, Umaña-Taylor AJ, eds. Studying Ethnic Minority and Economically Disadvantaged Populations: Methodological Challenges and Best Practices. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009:29-78. doi: 10.1037/11887-002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schaefer ES. Children’s reports of parental behavior: an inventory. Child Dev. 1965;36:413-424. doi: 10.2307/1126465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robin AL, Foster SL. Negotiating Parent-Adolescent Conflict: A Behavioral-Family Systems Approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Achenbach TM. Manual for the Youth Self-Report Form and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME Monitoring the future: national survey results on drug use, 1975–2018, volume 1: secondary school students. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. Accessed August 8, 2019. http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol1_2018.pdf

- 39.Enders CK. Applied Missing Data Analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelly AB, O’Flaherty M, Toumbourou JW, Connor JP, Hemphill SA, Catalano RF. Gender differences in the impact of families on alcohol use: a lagged longitudinal study of early adolescents. Addiction. 2011;106(8):1427-1436. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03435.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lavoie L, Dupéré V, Dion E, Crosnoe R, Lacourse É, Archambault I. Gender differences in adolescents’ exposure to stressful life events and differential links to impaired school functioning. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2019;47(6):1053-1064. https://doi-org.ezproxy.gsu.edu/10.1007/s10802-018-00511-4 doi: 10.1007/s10802-018-00511-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leadbeater BJ, Kuperminc GP, Blatt SJ, Hertzog C. A multivariate model of gender differences in adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems. Dev Psychol. 1999;35(5):1268-1282. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.35.5.1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nelson KM, Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LAJ, et al. . Gender differences in relations among perceived family characteristics and risky health behaviors in urban adolescents. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(3):416-422. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9865-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salazar CR, Strizich G, Seeman TE, et al. . Nativity differences in allostatic load by age, sex, and Hispanic background from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. SSM Popul Health. 2016;2:416-424. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gulbas LE, Zayas LH, Yoon H, Szlyk H, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Natera G. Deportation experiences and depression among US citizen-children with undocumented Mexican parents. Child Care Health Dev. 2016;42(2):220-230. doi: 10.1111/cch.12307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Little TD. Longitudinal Structural Equation Modeling. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit In: Bollen KA, Long JS, eds. Testing Structural Equation Models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woolf SH, Schoomaker H. Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States, 1959-2017. JAMA. 2019;322(20):1996-2016. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.16932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dreby J. The burden of deportation on children in Mexican immigrant families. J Marriage Fam. 2012;74:829-845. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00989.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Enriquez LM. Multigenerational punishment: shared experiences of undocumented immigration status within mixed-status families. J Marriage Fam. 2015;77:939-953. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12196 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stevens JS, van Rooij SJH, Jovanovic T. Developmental contributors to trauma response: the importance of sensitive periods, early environment, and sex differences. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2018;38:1-22. doi: 10.1007/7854_2016_38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maslowsky J, Schulenberg JE, Zucker RA. Influence of conduct problems and depressive symptomatology on adolescent substance use: developmentally proximal versus distal effects. Dev Psychol. 2014;50(4):1179-1189. doi: 10.1037/a0035085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fuhrmann D, Knoll LJ, Blakemore SJ. Adolescence as a sensitive period of brain development. Trends Cogn Sci. 2015;19(10):558-566. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2015.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stein GL, Gonzales RG, García Coll C, Prandoni JI. Latinos in rural, new immigrant destinations: a modification of the integrative model of child development In: Crockett L, Carlo G, eds. Rural Ethnic Minority Youth and Families in the United States: Advancing Responsible Adolescent Development. Springer; 2016:37-56. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-20976-0_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Urban Institute. Chaudry A, Capps R, Pedroza J, Castañeda RM, Santos R, Scott MM Facing our future: children in the aftermath of immigration enforcement. Published February 2, 2010. Accessed August 8, 2019. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/facing-our-future

- 56.Lovato K. Forced separations: a qualitative examination of how Latino/a adolescents cope with parental deportation. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2019;98:42-50. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.12.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suárez-Orozco C, Yoshikawa H, Teranishi R, Suárez-Orozco M. Growing up in the shadows: the developmental implications of unauthorized status. Harv Educ Rev. 2011;81(3):438-473. doi: 10.17763/haer.81.3.g23x203763783m75 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bucci M, Marques SS, Oh D, Harris NB. Toxic stress in children and adolescents. Adv Pediatr. 2016;63(1):403-428. doi: 10.1016/j.yapd.2016.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Garner AS, Shonkoff JP; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care; Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics . Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: translating developmental science into lifelong health. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e224-e231. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Linton JM, Nagda J, Falusi OO. Advocating for immigration policies that promote children’s health. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2019;66(3):619-640. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2019.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods 1. Sampling Procedures & Response Rates

eMethods 2. Missing Data

eMethods 3. Survey Items

eMethods 4. Measurement Models: Analytic Plan

eMethods 5. Structural Equation Models: Analytic Plan

eTable 1. Demographic Characteristics of Latino/as: US, Metro Atlanta, and the Study Sample

eTable 2. Baseline Study Variables by Participants Lost to Follow-up

eTable 3. Measurement Model: Parameter Estimates

eTable 4. Multivariate Logistic Structural Model Parameter Estimates

eTable 5. Sensitivity Analyses

eFigure 1. Flow Chart Describing Sampling Design and Characteristics

eFigure 2. Flow Chart Describing Response Rate