This diagnostic study develops and validates a penicillin allergy clinical decision rule that enables point-of-care risk assessment of patient-reported penicillin allergies.

Key Points

Question

Can a clinical decision rule risk stratify penicillin allergies and identify low-risk phenotypes amenable to point-of-care delabeling?

Findings

In this diagnostic study of 622 patients, a penicillin allergy decision rule (PEN-FAST) was derived from a prospective cohort of penicillin allergy–tested patients in 2 primary Australian sites and was subjected to internal and external validation in 3 local and international cohorts. PEN-FAST was found to be a practical tool with a high negative predictive value of 96.3% that uses penicillin allergy history to identify low-risk allergies.

Meaning

PEN-FAST may aid the risk stratification of patients with penicillin allergy to facilitate implementation of delabeling strategies and safe β-lactam prescribing.

Abstract

Importance

Penicillin allergy is a significant public health issue for patients, antimicrobial stewardship programs, and health services. Validated clinical decision rules are urgently needed to identify low-risk penicillin allergies that potentially do not require penicillin skin testing by a specialist.

Objective

To develop and validate a penicillin allergy clinical decision rule that enables point-of-care risk assessment of patient-reported penicillin allergies.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this diagnostic study, a multicenter prospective antibiotic allergy–tested cohort of 622 patients from 2 tertiary care sites in Melbourne, Australia (Austin Health and Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre) was used for derivation and internal validation of a penicillin allergy decision rule. Backward stepwise logistic regression was used to derive the model, including clinical variables predictive of a positive penicillin allergy test result. Internal validation of the final model used bootstrapped samples and the model scoring derived from the coefficients. External validation was performed in retrospective penicillin allergy–tested cohorts consisting of 945 patients from Sydney and Perth, Australia, and Nashville, Tennessee. Patients who reported a penicillin allergy underwent penicillin allergy testing using skin prick, intradermal, or patch testing and/or oral challenge (direct or after skin testing). Data were collected from June 26, 2008, to June 3, 2019, and analyzed from January 9 to 12, 2019.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome for the model was any positive result of penicillin allergy testing performed during outpatient or inpatient assessment.

Results

From an internal derivation and validation cohort of 622 patients (367 female [59.0%]; median age, 60 [interquartile range{IQR}, 48-71] years) and an external validation cohort of 945 patients (662 female [70.1%]; median age, 55 [IQR, 38-68] years), the 4 features associated with a positive penicillin allergy test result on multivariable analysis were summarized in the mnemonic PEN-FAST: penicillin allergy, five or fewer years ago, anaphylaxis/angioedema, severe cutaneous adverse reaction (SCAR), and treatment required for allergy episode. The major criteria included an allergy event occurring 5 or fewer years ago (2 points) and anaphylaxis/angioedema or SCAR (2 points); the minor criterion (1 point), treatment required for an allergy episode. Internal validation showed minimal mean optimism of 0.003 with internally validated area under the curve of 0.805. A cutoff of less than 3 points for PEN-FAST was chosen to classify a low risk of penicillin allergy, for which only 17 of 460 patients (3.7%) had positive results of allergy testing, with a negative predictive value of 96.3% (95% CI, 94.1%-97.8%). External validation resulted in similar findings.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, PEN-FAST was found to be a simple rule that accurately identified low-risk penicillin allergies that do not require formal allergy testing. The results suggest that a PEN-FAST score of less than 3, associated with a high negative predictive value, could be used by clinicians and antimicrobial stewardship programs to identify low-risk penicillin allergies at the point of care.

Introduction

Patient-reported penicillin allergies are frequently encountered in patients and significantly affect the judicious and appropriate use of antimicrobials.1,2 Penicillin allergies are also associated with antimicrobial resistance and poor patient outcomes.3,4,5 The success of antibiotic allergy testing (AAT) programs incorporated into antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) has been increasingly reported,2,6,7 frequently resulting in posttesting use of narrow-spectrum β-lactams.6,8,9 Formal AAT requires specialist interpretation, is labor intensive, and is potentially unwarranted, considering that less than 10% of penicillin allergies may be confirmed by formal testing results.2 A validated point-of-care clinical decision rule is needed that can be used by allergists and nonallergists to address the high burden of penicillin allergies, risk stratify across a range of phenotypes, and subsequently direct the appropriate delabeling and prescribing strategies. This need is particularly relevant when we consider the apparent deficit of drug allergy specialists available internationally.10

An AMS-led AAT program was assessed in a prospective, multicenter observational study that examined the testing outcomes of a large population of patients with penicillin allergy who underwent AAT via predefined criteria.6 We used these data and an extended prospective Australian cohort to derive and internally validate a penicillin allergy clinical decision rule (PEN-FAST) and subsequently performed external validation in local and international data sets.

Methods

The derivation and validation of PEN-FAST was obtained from a prospective penicillin allergy–tested cohort across 2 sites in Melbourne, Australia; external validation, from 3 retrospective cohorts from Sydney and Perth, Australia, and Nashville, Tennessee. Adults 16 years or older were included from all sites. A summary of the derivation and validation cohorts is shown in Table 1. All data were obtained after approval of the ethics committee or institutional review board at each institution. Data collected retrospectively did not require informed consent. This study followed the Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) reporting guideline.11

Table 1. Patient and Testing Characteristics of the Penicillin Allergy–Tested Derivation and Validation Cohorts.

| Characteristic | Cohort | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melbourne, Australia6 | Sydney, Australia | Perth, Australia8 | Nashville, Tennessee | |

| Cohort type | Prospective | Retrospective | Retrospective | Retrospective |

| No. of patients | 622 | 80 | 334 | 531 |

| Dates | May 1, 2015, to June 3, 2019 | July 1, 2015, to December 31, 2017 | June 26, 2008, to June 20, 2013 | January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2018 |

| Hospitals | Austin Health and Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre | Royal North Shore Hospital | Sir Charles Gardiner Hospital and Royal Perth Hospital | Vanderbilt University Medical Center |

| Inclusion criteria | Adults aged ≥18 y with ≥1 penicillin allergy | Adolescents and adults aged ≥16 y with ≥1 penicillin allergy | Adolescents and adults aged ≥16 y with ≥1 penicillin allergy | Adults aged ≥18 y with ≥1 penicillin allergy |

| Excluded phenotypes | AIN, DILI, serum sickness, drug fever (isolated) | AIN, DILI, serum sickness, drug fever (isolated) | SCAR, AIN, DILI, serum sickness, drug fever (isolated) | AIN, DILI, serum sickness, drug fever (isolated) |

| Testing sites | Inpatient/outpatient | Outpatient | Outpatient | Outpatient |

| Testing characteristics | SPT, IDT, PT, oral challenge (direct and after testing) | SPT, IDT, oral challenge (direct and after testing) | SPT, IDT, oral challenge (after testing) | SPT, IDT, PT, oral challenge (after testing) |

Abbreviations: AIN, acute interstitial nephritis; DILI, drug-induced liver injury; IDT, intradermal testing; PT, patch testing; SPT, skin prick testing; SCAR, severe cutaneous adverse reaction.

Derivation and Internal Validation Cohort

A prospective cohort of patients undergoing AAT-AMS and recruited from May 1, 2015, to June 3, 2019, were included. In brief, AAT-AMS was simultaneously introduced at Austin Health and the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne; the results of the first 118 patients have been previously published.6 Baseline demographic information, age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index,12 antibiotic allergy history, immunosuppression history, and allergy testing results were collected via a standardized case report form from a previous prospective study.6 The case report form and approach to phenotypic assessment are included in eMethods 1 and 2 in the Supplement.

Patients who reported any penicillin allergy and underwent skin prick testing (SPT), intradermal testing (IDT), patch testing, and/or oral challenge (directly or after skin testing) were extracted from a prospective database. Patients with a negative SPT or IDT result who did not undergo subsequent oral penicillin challenge were excluded. Antibiotic allergy testing was performed for outpatients and inpatients as previously described for immediate and delayed hypersensitivities (eMethods 2 in the Supplement).6,13

External Validation Cohorts

Two Australian retrospective outpatient penicillin allergy–tested cohorts from Royal North Shore Hospital, Sydney, from July 1, 2015, to December 31, 2017, and Royal Perth Hospital and Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, Perth, from June 26, 2008, to June 20, 2013, and an additional cohort from Vanderbilt Asthma, Sinus and Allergy Program, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2018, were used for external validation of the clinical decision rule. Available baseline demographic data and clinical information required to satisfy PEN-FAST criteria were extracted; if data were unavailable, they were listed as unknown. The summary of these cohorts is provided in Table 1. All cohorts included patients reporting a penicillin allergy who underwent testing using standard AAT protocols (eMethods 2 in the Supplement).6,8 Patients included had a positive SPT or IDT finding to any penicillin, a negative SPT or IDT finding followed by a penicillin oral challenge, or direct oral challenge with penicillin.

Definitions

A penicillin allergy was considered to include at least 1 of penicillin unspecified, penicillin VK, penicillin G, amoxicillin, ampicillin, dicloxacillin sodium, flucloxacillin, nafcillin sodium, or combined amoxicillin and clavulanate potassium. A patient-reported penicillin allergy was defined as a non–immune-mediated adverse drug reaction, immune-mediated reaction, or unknown, according to accepted criteria.14,15 An immunocompromised host was defined as a solid organ or hematological stem-cell transplant recipient, asplenic, having an autoimmune or connective tissue disorder, having cancer, or recipient of prednisone of more than 10 mg/d for more than 1 month.

In all cohorts (internal derivation and validation and external validation), a standard definition for AAT positivity was used (eMethods 2 in the Supplement). In all cohorts, penicillin VK or amoxicillin were used as the oral agent for post–skin testing challenges. A positive penicillin allergy test result was considered any 1 of a positive immediate SPT result, positive IDT result (immediate or delayed), positive patch test result, or positive oral challenge (single-dose or prolonged resulting in an immune-mediated reaction) to a penicillin reagent. No oral challenges were conducted to the specific drug with positive findings on skin testing (SPT or IDT); however, if drugs in the same class had negative test results (eg, positive skin test result for ampicillin and negative result for penicillin G), selective oral challenge was performed (eg, oral challenge to penicillin VK).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed from January 9 to 12, 2019. Categorical variables are presented as frequency (percentage) and continuous variables as median (interquartile range [IQR]). All continuous variables were recoded into categorical variables using different cutoff points, and final classification was based on the strength and size of their association with the outcome (positive penicillin allergy test result). Similarly, categorical variables with large numbers of categories were recoded into smaller numbers of categories based on clinical experience and their associations with the outcome.

The primary outcome for the model was any positive result of a penicillin allergy test performed during outpatient or inpatient assessment (SPT, IDT, patch testing, and/or oral challenge [direct or after skin testing]). All predictors considered for the inclusion in the model were obtained from the prospective testing database. Patient predictors included age, sex, ethnicity, history of psychiatric illness, age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index, and immunocompromised status. Collinearity between age and Charlson comorbidity index was minimal because both variables were recoded in 2 categories. Antibiotic allergy characteristics included number of patient-reported antibiotic allergy labels, time since the last reported antibiotic allergy (in years), allergy phenotype, and treatment of the index antibiotic allergy episode. Missing values in all variables were coded as a separate category (category unknown).

Univariate analysis was performed using logistic regression to examine the associations between patient/phenotype characteristics outlined above with any penicillin-positive allergy test result. Variables with a prevalence of at least 5% and those with 2-sided P < .20 on univariate analysis were included in the multivariable logistic regression model. A backward stepwise procedure was used, eliminating variables with 2-sided P > .10 and reincluding variables with 2-sided P < .05. This procedure was replicated in 1000 bootstrap samples, and only variables present in at least 60% of replication were included in the final model.16 Model performance in the original sample was evaluated by calculating the C statistic, Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic, calibration slope, and Brier score.

Internal validation was performed using a regular bootstrap procedure with 500 bootstrapped samples.17 Bootstrap performance of the final model was evaluated in each bootstrapped sample by calculating the C statistic, and test performance of the same model was evaluated in original sample. The optimism was calculated by subtracting test performance from bootstrap performance. Internally validated performance was calculated by subtracting mean optimism from apparent performance of the final model in the original sample.

A score for the final model was developed by rounding the coefficients of the logit model. Predicted and observed risk were calculated for each score. Sensitivity, specificity, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), positive predictive values (PPVs), and negative predictive values (NPVs) were calculated for each cutoff, and the final risk groups were chosen based on NPV and the false-negative rate.

External validation of the model was performed in 3 separate retrospective data sets. Risk score was calculated for each patient, and the model performance was evaluated by comparing AUC, sensitivity, specificity, NPV, and PPV. An additional predictive model was developed using least absolute shrinkage and selection operator logistic regression with cross validation (eMethods 3 in the Supplement). All analyses were performed using Stata, version 15.1 (StataCorp LLC).

Results

Study Population and Setting

The internal derivation and validation cohort included 622 patients (367 female [59.0%] and 255 male [41.0%]; median age, 60 [IQR, 48-71] years); the external validation cohort consisted of 945 patients (662 female [70.1%] and 283 male [29.9%]; median age, 55 [IQR, 38-68] years) (eTable 1 in the Supplement). During the study period in the internal derivation and validation cohorts, 1219 antibiotic allergies were reported by 773 adult patients who underwent AAT; specifically, 732 penicillin allergies were reported by 679 patients (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Fifty-one patients (7.5%) reported multiple penicillin allergies; only 1 entry was used based on a predetermined antibiotic hierarchy (penicillin VK, G, or unspecified, followed by amoxicillin, followed by ampicillin, followed by other). Thirty patients (4.4%) reported an allergy only to an intravenous penicillin without an oral formulation, such as a combination of piperacillin sodium and tazobactam sodium or a combination of ticarcillin disodium and clavulanate; these patients were excluded from the final cohort because intravenous or intramuscular challenges were not performed in the setting of negative test results. In addition, 1 patient was excluded because of missing results of allergy testing. From the remaining 648 patients, 58 had a positive test result (9.0%). Of the 590 with a negative test result, 564 subsequently underwent oral penicillin challenge (95.6%). Only those patients with a negative skin test result followed by an oral challenge (n = 564) and those with a positive skin test result were included (n = 58); a total of 622 adult patients were used for PEN-FAST derivation and internal validation. The baseline characteristics of the study cohort are outlined in Table 2.

Table 2. Baseline Demographics of Penicillin Allergy Cohort From AAT-AMS Database Used in Development and Internal Validation of Clinical Decision Rule.

| Characteristic (N = 622) | Dataa |

|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 60 (48-71) |

| Female | 367 (59.0) |

| Age-adjusted CCI, median (IQR)b | 3 (1-5) |

| Penicillin allergy labels | |

| Penicillin VK, G, or unspecified | 443 (71.2) |

| Amoxicillin or ampicillin | 117 (18.8) |

| Flucloxacillin or dicloxacillin | 29 (4.7) |

| Combined amoxicillin and clavulanate potassium | 33 (5.3) |

| Allergy phenotypesc | |

| Non–immune mediated (type A) | 15 (2.4) |

| Immediate immune-mediated (type B1) | 268 (43.1) |

| Delayed immune-mediated (type B4) | 206 (33.1) |

| SCARd | 5 (0.8) |

| Rash unspecified | 46 (7.4) |

| Concurrent cephalosporin allergy label | 116 (18.6) |

| Immunocompromised | 347 (55.8) |

| History of mental illnesse | 88 (14.1) |

| No. of allergy labels, median (IQR) | 1 (1-2) |

| Intradermal test performed | 468 (75.2) |

| Skin prick test performed | 498 (80.1) |

| Patch test performed | 8 (1.3) |

| Oral challenge | |

| Overall oral challenge performed after skin testing | 459 (73.8) |

| Oral challenge performed after skin testing in the outpatient setting (% of overall) | 456 (99.3) |

| Overall direct oral challenge (no skin testing performed) | 167 (26.8) |

| Direct oral challenge performed in the outpatient setting (% of overall) | 26 (15.6) |

| Any positive allergy test findingf | 60 (9.6) |

| Positive penicillin allergy test finding | 58 (9.3) |

Abbreviations: AAT-AMS, antibiotic allergy testing-antimicrobial stewardship; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; IQR, interquartile range; SCAR, severe cutaneous adverse reaction.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as number (percentage) of patients.

Scores range from 0 to 13, with higher scores indicating a greater number of comorbidities.

A indicates non–immune-mediated adverse drug reaction; B1, immediate hypersensitivity; B4, delayed hypersensitivity; unspecified, diffuse pruritic or nonpruritic or localized skin reaction or without any other reported symptoms or signs.

Including potential SCAR phenotypes, as per published definitions.18

Includes anxiety, psychosis, or depression.

Includes finding positive to alternative β-lactam on testing.

Penicillin Allergy Test Positivity

The prevalence of a positive penicillin allergy test was 9.3% (95% CI, 7.2%-11.9%) in the Melbourne cohort. Of those with a positive test result, patients with a positive reaction to SPT, IDT, or oral challenge are outlined in Table 2.

Patient and Phenotypic Factors Associated With a Positive Penicillin Allergy Test

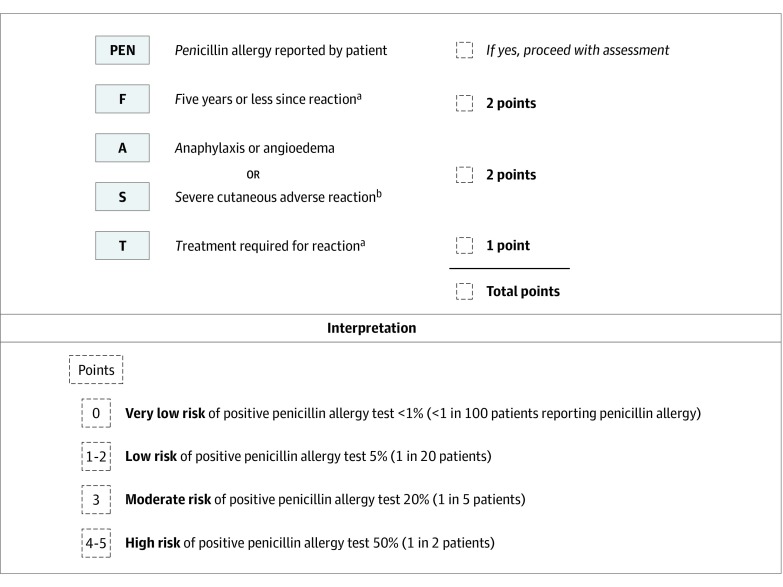

The characteristics associated with a positive penicillin allergy test result in univariate and multivariable analysis are shown in Table 3. The 4 features associated with a positive penicillin allergy test result on multivariable analysis were summarized in the mnemonic PEN-FAST (penicillin allergy, five or fewer years ago, anaphylaxis/angioedema or severe cutaneous adverse reaction [SCAR], and treatment required for allergy episode) (Figure). The major criteria included 5 or fewer years ago (2 points) and anaphylaxis/angioedema or potential SCAR (2 points); the minor criteria (1 point), treatment required for allergy episode. The model showed good discrimination (AUC = 0.808; Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2 = 1.84; P = .61) and calibration (calibration slope, 1; Brier score, 0.07; product-moment correlation between observed and predicted probability, 0.39). Internal validation showed minimal mean optimism of 0.003 with internally validated AUC of 0.805 (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Table 3. Univariate and Multivariable Analysis of Features Associated With a Positive Penicillin Allergy Test Result in Derivation and Validation Cohort.

| Clinical characteristic | No. (%) of participants | Univariate analysis | Multivariable analysisa | Point score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 622) | Any penicillin test positive (n = 58) | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | β Coefficient (95% CI) | P value | Presence in 1000 bootstrap replications, %a | ||

| Age, ≥80 y | 50 (8.0) | 1 (1.7) | 0.18 (0.02-1.36) | .10 | NA | NA | NA | 0 | NA |

| Age-adjusted CCI ≥1 | 522 (83.9) | 45 (77.6) | 0.63 (0.33-1.22) | .17 | NA | NA | NA | 18.2 | NA |

| Male | 255 (41.0) | 25 (43.1) | 1.10 (0.64-1.90) | .73 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Nonwhite race | 29 (4.7) | 3 (5.2) | 1.13 (0.33-3.85) | .85 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Any history of psychiatric disease | 88 (14.1) | 7 (12.1) | 0.82 (0.36-1.87) | .63 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Immunocompromised | 347 (55.8) | 38 (65.5) | 1.57 (0.89-2.76) | .12 | NA | NA | NA | 21.9 | NA |

| ≥2 Allergy labels | 182 (29.3) | 24 (41.4) | 1.81 (1.04-3.16) | .04 | NA | NA | NA | 27.3 | NA |

| Anaphylaxisb,c | 25 (4.0) | 8 (13.8) | 5.15 (2.12-12.52) | <.001 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Angioedemab | 30 (4.8) | 8 (13.8) | 3.94 (1.67-9.31) | .002 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Urticaria | 137 (22.0) | 15 (25.9) | 1.26 (0.68-2.35) | .46 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Collapse unspecified (ie, syncope) | 18 (2.9) | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Diffuse itchy rash | 180 (28.9) | 19 (32.8) | 1.22 (0.68-2.17) | .50 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Diffuse nonitchy rash | 86 (13.8) | 5 (8.6) | 0.55 (0.22-1.43) | .22 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Itch unspecified | 8 (1.3) | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Localized rash nil otherd | 25 (4.0) | 1 (1.7) | 0.41 (0.05-3.11) | .39 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Rash with skin ulceration | 4 (0.6) | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Respiratory distress | 28 (4.5) | 4 (6.9) | 1.67 (0.56-4.98) | .36 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Unspecified swellinge | 52 (8.4) | 3 (5.2) | 0.57 (0.17-1.90) | .36 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Unknown | 54 (8.7) | 3 (5.2) | 0.55 (0.17-1.82) | .33 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Rash with no other symptoms | 241 (38.7) | 14 (24.1) | 0.47 (0.25-0.88) | .02 | NA | NA | NA | 0.6 | NA |

| Severe reactionf | 377 (60.6) | 44 (75.9) | 2.20 (1.18-4.10) | .01 | NA | NA | NA | 16.1 | NA |

| Rash more than 10 y agoe | 169 (27.2) | 3 (5.2) | 0.13 (0.04-0.42) | .001 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Unknown reaction more than 10 y agoe | 42 (6.8) | 1 (1.7) | 0.22 (0.03-1.66) | .14 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Anaphylaxis, angioedema, SJS, TENS, DRESS, or AGEPg | 60 (9.6) | 20 (34.5) | 6.89 (3.67-12.94) | <.001 | 4.74 (2.41-9.33) | 1.56 (0.88-2.23) | <.001 | 95.8 | 2 |

| Nonsevere reaction in childhood | 190 (30.5) | 8 (13.8) | 0.34 (0.16-0.73) | .006 | NA | NA | NA | 24.8 | NA |

| Treatment required | 411 (66.1) | 50 (86.2) | 3.57 (1.66-7.68) | .001 | 2.78 (1.24-6.22) | 1.02 (0.22-1.83) | .01 | 74.3 | 1 |

| Hospitalization required | 214 (34.4) | 35 (60.3) | 3.25 (1.86-5.66) | <.001 | NA | NA | NA | 28.8 | NA |

| ICU admission requirede | 57 (9.2) | 9 (15.5) | 2.02 (0.93-4.37) | .07 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Previous allergy to the same drug | 610 (98.1) | 56 (96.6) | 0.51 (0.11-2.36) | .39 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Allergy in childhoode | 193 (31.0) | 8 (13.8) | 0.33 (0.15-0.71) | .005 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| <5 y since last allergy or unknown | 175 (28.1) | 40 (69.0) | 7.06 (3.92-12.73) | <.001 | 5.96 (3.24-10.96) | 1.79 (1.18-2.39) | <.001 | 100 | 2 |

Abbreviations: AGEP, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; DRESS, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; ICU, intensive care unit; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio; SJS, Stevens-Johnson syndrome; TENS, toxic epidermal necrolysis.

NA indicates variables not considered for multivariable model owing to P > .20 on univariate analysis or prevalence of less than 5%.

Not considered in multivariable model owing to prevalence of less than 5% and collinearity with other variables.

Adjudged by the clinician if the history was consistent with a cutaneous manifestation plus respiratory, cardiovascular, or gastrointestinal symptoms or acute-onset hypotension or bronchospasm/airway obstruction alone. If the patient was unable to recall the history but was told the phenotype was anaphylaxis, this was used as the default phenotype.

Indicates a rash localized to a single region of the body without other symptoms or signs of hypersensitivity.

Indicates generalized or local body swelling, not including angioedema.

Included any 1 of acute interstitial nephritis, AGEP, DRESS, TENS, SJS, fixed drug eruption, blistering or ulcerating skin reaction, hematological disorder, severe liver or renal impairment, neurological sequalae, anaphylaxis, angioedema, generalized swelling, urticaria, or respiratory compromise.

SJS and TEN also included potentially compatible syndromes of skin reaction with mucosal ulceration.

Figure. PEN-FAST Penicillin Allergy Clinical Decision Rule.

The PEN-FAST clinical decision rule for patients reporting a penicillin allergy uses 3 clinical criteria of time from penicillin allergy episode, phenotype, and treatment required. A total score is calculated using PEN-FAST score in the upper panel, and interpretation for risk strategy is provided in the lower panel.

aIncludes unknown.

bForms of severe delayed reactions include potential Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Patients with a severe delayed rash with mucosal involvement should be considered to have a severe cutaneous adverse reaction. Acute interstitial nephritis, drug induced liver injury, serum sickness and isolated drug fever were excluded phenotypes from the derivation and validation cohorts.

The following 4 risk groups were developed: very low risk (0 points), with a risk of allergy of 0.6%; low risk (1 or 2 points), with a risk of 5%; moderate risk (3 points), with a risk of 20%; and high risk (4 or 5 points), with 50% probability of having a positive penicillin test result (eTable 2 in the Supplement). A cutoff of less than 3 points for PEN-FAST was chosen that classified 460 of 622 patients (74.0% of the cohort) as at low risk of allergy, of whom only 17 (3.7%) had positive test results for 1 or more penicillin allergy test (2 of 17 for SPT; 13 of 17 for IDT; and 6 of 17 for oral challenge). Of the remaining 162 patients who were classified as at higher risk, 41 (25.3%) had a positive allergy test result. The sensitivity to identify penicillin allergy using this cutoff was 70.7% (95% CI, 57.3%-81.9%); specificity, 78.5% (95% CI, 74.9%-81.9%); PPV, 25.3% (95% CI, 18.8%-32.7%); and NPV, 96.3% (95% CI, 94.1%-97.8%) (Table 4 and eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Table 4. Validation of PEN-FAST in Predicting a Positive Penicillin Allergy Test Result in All Derivation and Validation Cohorts.

| Cohort | No. of patients |

No. (%) with positive findinga | Validationb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI), % | Specificity (95% CI), % | PPV (95% CI),% | NPV (95% CI), % | |||

| Melbourne, Australia | 622 | 58 (9.3) | 0.75 (0.68-0.81) | 70.7 (57.3-81.9) | 78.5 (74.9-81.9) | 25.3 (18.8-32.7) | 96.3 (94.1-97.8) |

| Perth, Australia | 334 | 48 (14.4) | 0.73 (0.66-0.81) | 87.5 (74.8-95.3) | 39.9 (34.1-45.8) | 19.6 (14.5-25.6) | 95.0 (89.4-98.1) |

| Sydney, Australia | 80 | 27 (33.8) | 0.78 (0.68-0.88) | 70.4 (49.8-86.2) | 84.9 (72.4-93.3) | 70.4 (49.8-86.2) | 84.9 (72.4-93.3) |

| Nashville, Tennessee | 531 | 19 (3.6) | 0.74 (0.62-0.86) | 73.7 (4.8-90.9) | 59.8 (55.4-64.0) | 6.4 (3.5-10.4) | 98.4 (96.3-99.5) |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristics curve; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Indicates any penicillin allergy test with a positive finding.

Based on a PEN-FAST score of at least 3.

Validation of PEN-FAST

Results for validation in the 945 adult patients from 3 centers (Sydney, Perth, and Nashville) are demonstrated in Table 4. Overall, the AUC analysis indicated good discrimination for the PEN-FAST scores in all external databases, including 0.81 (95% CI, 0.75-0.86) for Melbourne, 0.81 (95% CI, 0.71-0.91) for Sydney, 0.73 (95% CI, 0.66-0.80) for Perth, and 0.85 (95% CI, 0.74-0.96) for Nashville (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). There was no clear evidence for a lack of fit, indicating good prediction by PEN-FAST of positive penicillin allergy test results (eFigure 3 in the Supplement).

Discussion

PEN-FAST is a clinical decision rule that, in this study, demonstrated the high NPV required for a rule-out test, similar to that elicited from formal penicillin allergy skin-testing studies.19,20 A PEN-FAST score of less than 3 was able to exclude severe penicillin allergy. This finding is important because penicillin allergy is increasingly recognized as a public health issue for communities and hospitals,2 with well-described deleterious effects on patients and health economics.1,21 With more than 20 million persons in North America likely to be harboring a penicillin allergy label and a global deficit in the number of allergists with drug allergy training,10,22 addressing penicillin allergy is becoming the domain of nonallergists.7 A barrier to widespread implementation of penicillin allergy assessment is the absence of externally validated point-of-care tools to risk stratify penicillin allergies, in particular the identification of low-risk (nonsevere) penicillin allergies amenable to oral challenge rather than penicillin skin testing.23,24 PEN-FAST uses information obtained from patient history to accurately risk stratify patients. This risk stratification can be performed across a spectrum of NPVs appropriate for the care setting and clinician experience, with a PEN-FAST score of 0 equating to an NPV of 99.4% (95% CI, 96.6%-100%) or a PEN-FAST score of less than 3 equating to an NPV of 96.3% (95% CI, 94.1%-97.8%).

Clinical decision rules have been explored to predict true penicillin hypersensitivity. Stevenson et al25 studied 447 Australian patients to identify a low-risk criterion consisting of a benign rash more than 1 year previous (sensitivity, 80.6%; specificity, 60.8%). Their study is a large step forward in further characterizing a low-risk criterion but, as suggested by the authors, is limited by a lack of international validation and heterogeneity of testing in the retrospective cohort. Chiriac et al26 explored a β-lactam clinical decision rule, with derivation performed in a large retrospective data set from France and external validation in smaller prospective data sets (AUC, 0.67; NPV, 83%). The authors found that anaphylaxis and time from event (eg, childhood) were strong predictors, similar to our cohort, but findings were limited by the collective use of all β-lactam allergies, retrospective data collection, and small validation cohorts. Siew et al27 used a retrospective cohort from the United Kingdom (n = 1092) to identify predictors of true allergy and generated a low-risk criteria (NPV of 98.4%) consisting of (1) no anaphylaxis, (2) reaction more than 1 year ago, and (3) no recall of index drug. The editorial praised the simplicity but noted the absence of a wider array of allergy histories (eg, angioedema/swelling), absence of external validation, and applicability to only IgE-mediated allergies.27 Interestingly, Ramsey et al28 recently demonstrated in a randomized clinical trial a low-risk penicillin allergy clinical criterion, with only a 3.8% false-negative rate (cutaneous only or unknown reaction >1 year ago for ages 15-17 years or >10 years ago for age ≥18 years); all adults in this cohort would have demonstrated a PEN-FAST score of less than 3.29

Limitations

There are limitations to the PEN-FAST rule, such as the exclusion of nonpenicillin β-lactam allergies and some intravenous penicillins (which could not be confirmed with oral challenge), a limited number of patients with SCAR-like phenotypes, predominance of inpatient testing, and applicability to adult patients only. Although external validation was performed in a large cohort (n = 945), missing data included lack of documentation regarding treatment of the acute allergy episode (Nashville and Perth cohorts). The validation in ethnically diverse populations (eg, European, Asian, and African) where the prevalence of penicillin allergy and phenotypes is likely to vary is an important next step. The NPV and AUC of PEN-FAST remained clinically relevant in all tested patient cohorts in this study, despite variations in the prevalence of positive test results at the different study sites. Despite variations in skin testing reagents, similar testing protocols were used in Melbourne, Perth, and Nashville, and oral challenge was the definitive outcome in all cohorts. Patients with SCAR were included, despite no robust criterion standard for testing being available,30 because we believe this reinforces among clinicians the need to identify and be alert to these life-threatening phenotypes that may require avoidance of all penicillins and cephalosporins. The terms used in PEN-FAST (eg, anaphylaxis, angioedema, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) should be recognizable by the target users of this decision rule: allergists, immunologists, infectious disease physicians, internal medicine clinicians, and pharmacists.2,20 Further, assessment tools are now available to aid clinicians in appropriate allergy assessments,20,31 and such tools could be paired with PEN-FAST. Due to the inherent error rate in the electronic health record, we would advise that PEN-FAST be applied only on a detailed clinical history obtained directly from the patient rather than electronic health record data only.

Conclusions

The current status quo of outpatient penicillin allergy assessments performed by allergists is inadequate to meet current and future demand for AAT,10,32 and point-of-care tools are urgently needed to effectively reduce the high burden of patients falsely labeled as penicillin allergic. PEN-FAST potentially allows clinicians to evaluate penicillin allergy risk and severity, thereby encouraging the safe use of β-lactams and oral challenge programs in those patients considered to be at low risk of penicillin allergy.

eMethods 1. Data Collection and Case Report Form (CRF)

eMethods 2. Antibiotic Allergy Testing (AAT) Procedures From Derivation and Validation Cohorts

eMethods 3. LASSO Logistic Regression With Cross-Validation

eFigure 1. Patient-Reported Antibiotic Allergy Labels in Antibiotic Allergy–Tested Cohort

eFigure 2. Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC) Analysis

eFigure 3. Calibration of the PEN-FAST Rule in Derivation/Validation Cohort (Melbourne, Australia)

eTable 1. Baseline Demographics of External Validation Cohorts of Patients Reporting Any Oral Penicillin Allergy Who Underwent Testing as per Specified Methods

eTable 2. Percentage of PEN-FAST Risk Scores for All Datasets Utilized

eTable 3. Derivation of Cutoff Scores for Clinical Decision Rule, PEN-FAST

eReferences.

References

- 1.Trubiano JA, Chen C, Cheng AC, Grayson ML, Slavin MA, Thursky KA; National Antimicrobial Prescribing Survey (NAPS) . Antimicrobial allergy “labels” drive inappropriate antimicrobial prescribing: lessons for stewardship. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(6):1715-1722. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blumenthal KG, Peter JG, Trubiano JA, Phillips EJ. Antibiotic allergy. Lancet. 2019;393(10167):183-198. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32218-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacFadden DR, LaDelfa A, Leen J, et al. Impact of reported beta-lactam allergy on inpatient outcomes: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(7):904-910. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trubiano JA, Leung VK, Chu MY, Worth LJ, Slavin MA, Thursky KA. The impact of antimicrobial allergy labels on antimicrobial usage in cancer patients. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2015;4:23. doi: 10.1186/s13756-015-0063-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macy E, Contreras R. Health care use and serious infection prevalence associated with penicillin “allergy” in hospitalized patients: a cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(3):790-796. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trubiano JA, Thursky KA, Stewardson AJ, et al. Impact of an integrated antibiotic allergy testing program on antimicrobial stewardship: a multicenter evaluation. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(1):166-174. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trubiano J, Phillips E. Antimicrobial stewardship’s new weapon? a review of antibiotic allergy and pathways to “de-labeling”. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2013;26(6):526-537. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourke J, Pavlos R, James I, Phillips E. Improving the effectiveness of penicillin allergy de-labeling. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3(3):365-34.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marwood J, Aguirrebarrena G, Kerr S, Welch SA, Rimmer J. De-labelling self-reported penicillin allergy within the emergency department through the use of skin tests and oral drug provocation testing. Emerg Med Australas. 2017;29(5):509-515. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trubiano JA, Beekmann SE, Worth LJ, et al. Improving antimicrobial stewardship by antibiotic allergy delabeling: evaluation of knowledge, attitude, and practices throughout the emerging infections network. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3(3):ofw153. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofw153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, Moons KGM. Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD). Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(10):735-736. doi: 10.7326/L15-5093-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trubiano JA, Douglas AP, Goh M, Slavin MA, Phillips EJ. The safety of antibiotic skin testing in severe T-cell-mediated hypersensitivity of immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(4):1341-1343.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rawlins MDTJ. Textbook of Adverse Drug Reactions. Oxford University Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pichler WJ. Drug sensitivity reactions: classification and relationship to T-cell activation In: Pichler WJ, ed. Drug Hypersensitivity. S Karger Pub; 2007:168-189. doi: 10.1159/000104199 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Austin PC, Tu JV. Bootstrap methods for developing predictive models. Am Stat. 2004;58(2):7. doi: 10.1198/0003130043277 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steyerberg EW, Harrell FE Jr, Borsboom GJ, Eijkemans MJ, Vergouwe Y, Habbema JD. Internal validation of predictive models: efficiency of some procedures for logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(8):774-781. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00341-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duong TA, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Wolkenstein P, Chosidow O. Severe cutaneous adverse reactions to drugs. Lancet. 2017;390(10106):1996-2011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30378-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Solensky R, Jacobs J, Lester M, et al. Penicillin allergy evaluation: a prospective, multicenter, open-label evaluation of a comprehensive penicillin skin test kit. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(6):1876-1885.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.02.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shenoy ES, Macy E, Rowe T, Blumenthal KG. Evaluation and management of penicillin allergy: a review. JAMA. 2019;321(2):188-199. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.19283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blumenthal KG, Lu N, Zhang Y, Li Y, Walensky RP, Choi HK. Risk of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Clostridium difficile in patients with a documented penicillin allergy: population based matched cohort study. BMJ. 2018;361:k2400. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k2400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Derrick MI, Williams KB, Shade LMP, Phillips EJ. A survey of drug allergy training opportunities in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(1):302-304. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Banks TA, Tucker M, Macy E. Evaluating penicillin allergies without skin testing. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2019;19(5):27. doi: 10.1007/s11882-019-0854-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trubiano JA, Smibert O, Douglas A, et al. The safety and efficacy of an oral penicillin challenge program in cancer patients: a multicenter pilot study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5(12):ofy306. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofy306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stevenson B, Trevenen M, Klinken E, et al. Multicenter Australian study to determine criteria for low- and high-risk penicillin testing in outpatients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(2):681-689.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiriac AM, Wang Y, Schrijvers R, et al. Designing predictive models for beta-lactam allergy using the drug allergy and hypersensitivity database. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(1):139-148.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.04.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siew LQC, Li PH, Watts TJ, et al. Identifying low-risk beta-lactam allergy patients in a UK tertiary centre. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(7):2173-2181.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramsey A, Caubet JC, Blumenthal K. Risk stratification and prediction in beta-lactam allergic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(7):2182-2184. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.05.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mustafa SS, Conn K, Ramsey A. Comparing direct challenge to penicillin skin testing for the outpatient evaluation of penicillin allergy: a randomized, controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(7):2163-2170. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.05.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phillips EJ, Bigliardi P, Bircher AJ, et al. Controversies in drug allergy: testing for delayed reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(1):66-73. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.10.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Devchand M, Urbancic KF, Khumra S, et al. Pathways to improved antibiotic allergy and antimicrobial stewardship practice: The validation of a beta-lactam antibiotic allergy assessment tool. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(3):1063-1065.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.07.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trubiano JA, Worth LJ, Urbancic K, et al. ; Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases Clinical Research Network; Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy . Return to sender: the need to re-address patient antibiotic allergy labels in Australia and New Zealand. Intern Med J. 2016;46(11):1311-1317. doi: 10.1111/imj.13221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods 1. Data Collection and Case Report Form (CRF)

eMethods 2. Antibiotic Allergy Testing (AAT) Procedures From Derivation and Validation Cohorts

eMethods 3. LASSO Logistic Regression With Cross-Validation

eFigure 1. Patient-Reported Antibiotic Allergy Labels in Antibiotic Allergy–Tested Cohort

eFigure 2. Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC) Analysis

eFigure 3. Calibration of the PEN-FAST Rule in Derivation/Validation Cohort (Melbourne, Australia)

eTable 1. Baseline Demographics of External Validation Cohorts of Patients Reporting Any Oral Penicillin Allergy Who Underwent Testing as per Specified Methods

eTable 2. Percentage of PEN-FAST Risk Scores for All Datasets Utilized

eTable 3. Derivation of Cutoff Scores for Clinical Decision Rule, PEN-FAST

eReferences.