Abstract

Background: Forearm peak pronation and supination torque measurements are reduced up to 30% in patients with triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) 1B injuries with concomitant distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) instability. The aim of our study was to evaluate whether patients with TFCC 1B injuries, with concomitant DRUJ instability, improve in forearm peak pronation and supination torque following TFCC reinsertion surgery where postoperative DRUJ stability was achieved. Methods: We report a retrospective case series with short-term follow-up (20 months) of the postoperative forearm peak torque in pronation and supination in 11 patients (9 women/2 men, average age at surgery 32 years) operated on by TFCC reinsertion. Two of the initial 13 patients were later on reoperated due to recurring DRUJ instability and were therefore excluded in this follow-up study. Nine were treated by arthroscopic TFCC reinsertion and 2 by open technique. The forearm peak pronation and supination torque were measured pre- and postoperatively and compared with the uninjured side. Results: On average, a 16% improvement of the forearm peak torque was achieved in the injured wrist, as well as clinically assessed DRUJ stability. Functional postoperative improvement was noted in all patients, with reduced pain, good satisfaction, and acceptance of the surgery and the final result. Conclusion: We conclude that patients with TFCC injuries and DRUJ instability gain improved forearm peak pronation and supination torque after reinsertion. We also conclude that forearm peak pronation and supination torque is a valuable tool in the preoperative diagnostics of TFCC injuries with DRUJ instability as well as in the postoperative follow-up.

Keywords: wrist, triangular fibrocartilage complex, distal radioulnar joint, forearm peak pronation and supination torque, arthroscopic reinsertion

Introduction

Detecting injuries to the triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC), with or without concomitant distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) instability, can be clinically challenging. The ulnar fovea sign16 has a good sensibility and specificity in detecting foveal and/or ulnotriquetral ligament injuries, whereas stress and laxity tests for DRUJ instability11,14 are often subjective and have low accuracy. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has a low negative predictive value (NPV)3 and is not capable to rule out possible wrist ligament injuries. In addition, MRI is not sufficiently specific to grade instability or potential ligament healing capacity. Arthroscopy still remains the gold standard in the diagnostics of wrist ligament injuries3 and also in evaluating the degree of instability and structural quality of ligaments. The need for a reliable, readily accessible, noninvasive and inexpensive diagnostic tool for detecting TFCC injury with DRUJ instability—and also for evaluating outcomes of surgery—is thus evident.

Standardized measurement of forearm peak pronation and supination torque has recently been shown to be a valid method with high intraclass correlation (ICC) and good responsiveness,5,6 and is suggested to be a beneficial clinical tool in the diagnostics of TFCC 1B injuries.4 The aim of our study was to evaluate whether patients with TFCC 1B injuries,13 with concomitant DRUJ instability, improve in forearm peak pronation and supination torque following TFCC reinsertion surgery where postoperative DRUJ stability was achieved.

Materials and Methods

Material

Eleven patients (9 female/2 male) with arthroscopically diagnosed TFCC 1B injuries and clinical DRUJ instability, operated on by reinsertion of the TFCC, were recruited to the study. Mean age of the patients at the time of surgery was 32 years. Eight (73%) of the patients were operated on the nondominant side. All the patients in the study were referred to our academic tertiary care center, and all had injuries occurring more than 6 months before the preoperative examination and torque measurement.

Torque Measurements

Pre- and postoperative forearm peak pronation and supination torque measurements were performed using a wrist dynamometer supplied with a digital pressure gauge (Model BL-2000, Baseline, White Plains, New York) (Figure 1).4-6 The device was calibrated at the Research Institute of Sweden (RISE), division SP (Statens Provningsanstalt). The precision of measurement of the dynamometer was 0.01 Nm.

Figure 1.

Measurement of forearm peak supination torque of the right wrist, standing with the elbow fixed to the body and in 90° of flexion. Measurement technique developed by Peter Axelsson. Photo: Tommy Holl.

The protocol for measurement followed that of a recently published validity study6 and the preoperative measurement of suspected TFCC 1B injuries by Andersson et al4 The patient was in a standing position, fully adducted arm and elbow flexed to 90°. Peak supination followed by peak pronation torque were measured once starting from a neutral position, with the examiner carefully ensuring that the patient did not bring the elbow into abduction or lean the body in any direction. The noninjured side was measured first, followed by the injured side. Measurements were recorded preoperatively and at a mean 20 months postoperatively (range, 12-39 months). An independent observer (a physical therapist) measured the pre- and postoperative peak pronation and supination torque.

The validity and ICC of the torque dynamometer, modified and adapted to the clinical setting, was earlier shown to be high in 15 healthy volonteers.4 Peak pronation and supination torque was measured prior to surgery in 21 patients with suspected TFCC injuries with clinical DRUJ instability and arthroscopically confirmed TFCC 1B injury in 18 of them in a prior previously published study.4 Thirteen of these patients in the initial cohort were operated on with TFCC reinsertion. Two of these 13 patients (1 operated by open technique, 1 by arthroscopic technique) were later on reoperated due to recurring DRUJ instability and were therefore excluded in this follow-up study. Laxity of the DRUJ was tested using the DRUJ ballottement test, whereby the forearm is held in neutral rotation by the examiner, stabilizing the hand and the distal radius with a firm grip, followed by forcing the ulna in a dorsal/palmar direction, relative to the stabilized unit of the hand and radius by the examiner using the other hand.11 The laxity of the DRUJ was compared with that of the nonoperated wrist.

Eleven patients were thus included and available for a postoperative follow-up measurement of forearm peak pronation and supination torque.

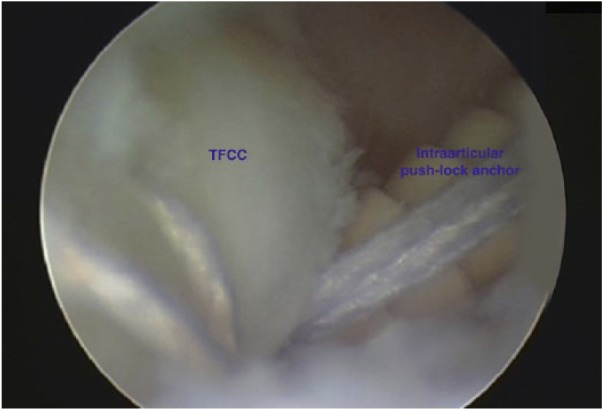

All of the patients were operated on with reinsertion of the TFCC by one of the surgeons (J.K.A.) with surgical skills level 4 according to Tang and Giddins,15 either by an all-arthroscopic technique with Arthrex push-lock anchors (n = 9) (Figure 2) or by open surgery (n = 2).

Figure 2.

All-arthroscopic TFCC reinsertion with push-lock suture anchor (Arthrex). TFCC = triangular fibrocartilage complex.

Statistical Methods

Forearm peak torque in both pronation and supination were compared with the preoperative values and the nonoperated healthy side (Table 1). For obvious reasons, no preinjury measurements of torque were available. Therefore, we compared the injured wrist with the contralateral noninjured/nonoperated side to assess and evaluate the postoperative change of peak torque. Patient demographics and peak pronation and supination torque differences—in percentage on operated side postoperative compared with preoperative values and the nonoperated healthy side—are shown in Table 2. Descriptive data were reported by means with standard deviation (SD), median, and range values.

Table 1.

The Forearm Peak Pronation and Supination Torque in Nm Measured Pre- and Postoperatively, and Compared With the Noninjured Side.

|

Patient no. |

Torque strength preop pronation | Torque strength preop supination | Torque strength postop pronation | Torque strength postop supination |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8.1/10.2 (79.4%) | 10.2/11.6 (87.9%) | 8.1/7.9 (102.5%) | 9.8/10.5 (93.3%) |

| 2 | 5.1/5.5 (92.7%) | 9.2/11.1 (82.9%) | 4.9/5.5 (89.1%) | 7.2/7.5 (96.0%) |

| 3 | 5.0/6.7 (74.6%) | 5.1/9.3 (54.8%) | 7.5/7.7 (97.4%) | 8.1/11.4 (71.1%) |

| 4 | 6.0/6.0 (100%) | 8.3/11.0 (75.5%) | 6.5/6.2 (104.8%) | 7.5/8.8 (85.2%) |

| 5 | 3.4/9.2 (37.0%) | 4.2/12.8 (32.8%) | 4.9/7.4 (66.2%) | 7.0/10.0 (70.0%) |

| 6 | 5.1/6.8 (75.0%) | 9.5/11.8 (80.5%) | 5.7/6.2 (91.9%) | 9.6/12.5 (76.8%) |

| 7 | 5.1/6.3 (81.0%) | 4.7/10.1 (46.5%) | 7.5/6.9 (108.7%) | 9.6/11.7 (82.1%) |

| 8 | 9.2/13.9 (66.2%) | 11.9/13.3 (89.5%) | 10.4/10.4(100.0%) | 12.4/15.8 (78.5%) |

| 9 | 8.0/8.1 (98.8%) | 11.1/13.8 (80.4%) | 8.0/8.1 (98.8%) | 11.1/13.8 (80.4%) |

| 10 | 7.9/8.4 (94.0%) | 9.1/14.3 (63.6%) | 10.8/11.5 (93.9%) | 12.7/13.8 (92.0%) |

| 11 | 3.8/7.9 (48.1%) | 4.5/8.1 (55.6%) | 7.1/8.4 (84.5%) | 8.1/9.3 (87.1%) |

| Mean (%) of nonoperated side | 77.0% | 68.2% | 94.4% | 83.0% |

Note. Injured side/noninjured side (percentage of noninjured side).

Table 2.

Patient Demographics and Peak Torque Differences in Percentage on Operated Side Compared With Nonoperated Healthy Side.

| Patient no. | Sex | Age at operation | Side | Operation | DRUJ stable post-op | Follow-up time (months) | Torque difference pronation (%) | Torque difference supination (%) | Mean difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 26.6 | Sin | A | Yes | 12 | 23.1% | 5.4% | 14.3% |

| 2 | F | 52.3 | Sin | A | Yes | 12 | −3.6% | 13.1% | 4.8% |

| 3 | F | 29.3 | Sin | A | Yes | 13 | 22.8% | 16.3% | 19.6% |

| 4 | F | 15.8 | Sin | A | Yes | 15 | 4.8% | 9.7% | 7.3% |

| 5 | F | 38.7 | Dx | A | Yes | 39 | 29.2% | 37.2% | 33.2% |

| 6 | F | 15.8 | Sin | A | Yes | 16 | 16.9% | −3.7% | 6.6% |

| 7 | F | 47.3 | Sin | A | Semistable | 26 | 27.7% | 35.6% | 31.7% |

| 8 | M | 25.6 | Sin | O | Yes | 12 | 33.8% | −11.0% | 11.4% |

| 9 | F | 46.7 | Dx | A | Yes | 26 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 10 | M | 18.0 | Sin | A | Yes | 16 | −0.1% | 28.4% | 14.2% |

| 11 | F | 32.2 | Dx | O | Yes | 36 | 36.4% | 31.5% | 34.0% |

| Total mean | 82% female | 32 years | 73% nondominant side | 9 arthroscopic 2 open |

20 mo. | 17.4% | 14.8% | 16.1% |

Note. DRUJ = distal radioulnar joint; Sin = left; Dx = right.

Due to the limited number of cases, collected strength data did not consistently follow a Gaussian distribution. Therefore, the postoperative forearm peak pronation and supination torque measurements were compared with normalized preoperative values of the contralateral, nonaffected side and expressed as percentage change. Wilcoxon rank paired tests were used after normalization. We chose the contralateral side as comparison due the confounding factors involved in preoperative measurements of the injured side (pain, instability, fear of loading). Data are presented as median, maximum, and minimum values. Level of significance was set at P < .05.

The study was approved by the ethical review board, Etiska Prövningsnämnden, Gothenburg, Sweden (Dnr: 977-12). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants in the study.

Results

The postoperative measurements, at an average of 20 months (range, 12-39) after surgery, of the forearm peak pronation and supination torque in the 11 patients all together showed an overall mean improvement of 16.1% (SD = 11.5) and median of 14.2% (range, 0.0-34.0) after reinsertion of the TFCC with clinically and subjectively postoperative stable DRUJ (Table 1 and Table 2).

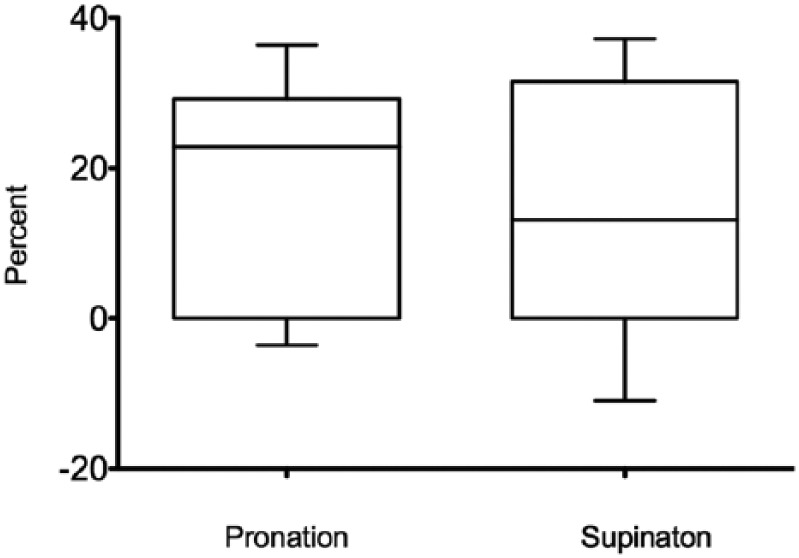

The mean improvement in pronation was 17.4% (SD = 14.0), median 22.8% (range, –3.6 to 36.4), which was a significant improvement compared with preoperative values (P = .0098). The mean improvement in supination was 14.8% (SD = 15.8), median 13.1 (range, –11.0 - 31.5), which was also a statistically significant improvement (P = .0195) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Box-plot of the postoperative change in forearm peak torque (pronation and supination) in percentage, in the operated wrist, compared with the preoperative values. The improvements were statistically significant, P = .0098 and .0195 for pronation and supination, respectively.

The mean achieved forearm peak pronation and supination torque postoperative was 6.7 Nm in pronation and 8.7 in supination in female (n = 9) and 11.6 Nm in pronation and 12.6 Nm in supination in males (n = 2).

Several medical conditions can influence the torque, including epicondylitis12 and ulnar impaction syndrome.7 None of the patients in the present study reported symptoms or demonstrated any clinical signs of the medical conditions above, thus excluding other illnesses as possible confounding factors.

All patients (n = 11) demonstrated a good result of the surgery with clinically and subjectively improved DRUJ stability, reduced pain levels, and satisfaction with the postoperative result. Functional postoperative improvement was noted in all patients, as assessed through patient interviews, with reduced pain, good satisfaction, and acceptance of the surgery and the final result. No adverse complications (ie, extensor carpi ulnaris tendonitis, neuroma, postoperative infection) were noted. All of the 11 evaluated patients returned to their original occupation and leisure activities.

Discussion

This study reports a significant and a clinically relevant postoperative improvement of the forearm peak torque in both pronation and supination in patients operated on with successful reinsertion of TFCC 1B injuries with concomitant DRUJ instability.

Eight (73%) of the patients in this study were operated on the nondominant side. It is known from previous and current studies that the nondominant upper extremity has forearm peak pronation and supination torque values between approximately 85% and 95% of the values of the dominant right upper extremity.5,10

Standing and sitting positions and several medical conditions can influence the torque, including epicondylitis12 and ulnar impaction syndrome.7 All of the patients in this study were measured in a standardized position; standing with fully adducted arm and elbow flexed to 90°. None of the patients in the present study reported symptoms or demonstrated any clinical signs of the medical conditions above, thus excluding other illnesses as possible confounding factors.

To date, there have been no commercially available techniques to evaluate peak torque. The importance of torque as a measurement of DRUJ function has been recognized at an early stage with custom-made instruments.10 A prior study using custom-made devices for forearm rotation has been unable to establish a clear correlation between loss of torque strength and instability of the DRUJ in patients with distal radius fractures.8 The present cohort is selected and consists of a homogeneous group with clear TFCC 1B injuries, which may have contributed to the consistent findings in this study. Four patients out of 11 in our cohort had had a previous distal radius fracture, healed in good anatomical positions, without malunion. Their DRUJ instability were thus determined to be caused by the TFCC1B injury and not by a joint malalignment due to the previous fracture.

Our measuring method can be easily adapted to the standard clinical setting and can now be used as a diagnostic adjunct to clinical tests and imaging studies. This forearm peak pronation and supination torque measuring method has been shown to be a valid method with high ICC and good responsiveness.6 Normative values for peak torque have also been established.5 The mean achieved postoperative forearm peak pronation and supination torque in our study was similar to the normative values found among healthy individuals in the study by Axelsson et al5 This peak torque measurement technique appears to have sufficient diagnostic power to reliably detect TFCC 1B injuries.

In a previous publication,4 a verified association between the preoperative decrease in peak torque in the injured side of approximately 30% in both pronation and supination was seen in patients with arthroscopically diagnosed TFCC 1B injuries.4 Accordingly, forearm peak torque seems to be a valuable tool in the preoperative diagnostics of TFCC injuries with DRUJ instability as well as in the postoperative follow-up. This measurement technique should also probably be valuable in terms of detecting surgical failures with postoperative recurrence of TFCC injury and/or DRUJ instability.

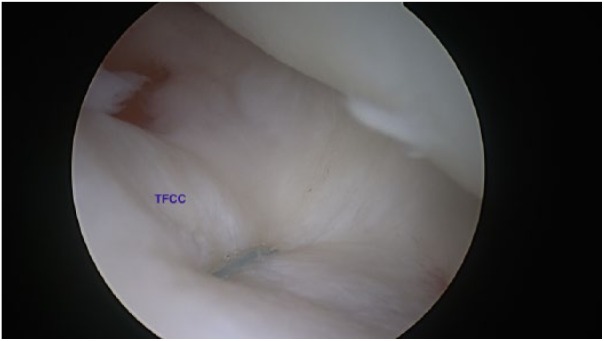

All-arthroscopic TFCC reinsertions with Arthrex push-lock anchor technique proved to be safe in the short-term for reinsertion of TFCC type 1B injuries, with regard to postoperative DRUJ stability, peak torque, and complications rate. However, it is a challenging and time-consuming procedure that may be replaced by the less demanding TFCC ulnar tunnel repair technique (Arthrex) with extra-articular ulnar push-lock anchor fixation (Figure 4). It remains to be investigated, however, how the clinical result and return of peak torque is in patients treated by this ulnar tunnel technique.

Figure 4.

Arthroscopic TFCC ulnar tunnel reinsertion with extra-articular push-lock suture anchor (Arthrex) fixation. TFCC = triangular fibrocartilage complex.

Two patients were excluded from our study due to recurrent DRUJ instability. If taking them into account, the rate of recurrent DRUJ instability and need for reoperation in our study would be 15.4%. It is similar to the findings in other studies.1,2,9 Comparable results are seen between open and arthroscopic repair of the TFCC, in terms of DRUJ reinstability and functional outcome scores in a newly published systematic review.2 There is insufficient evidence to recommend one technique over the other in clinical practice. However, there is an immense lack of comparison studies with high level of evidence in the area of wrist ligament repair and reconstruction, including TFCC injuries and DRUJ instability.

As for obvious reasons no preinjury measurements of forearm peak pronation and supination torque were available, comparison with the contralateral noninjured/nonoperated side seemed the most clinically proper way of assessment and evaluation of postoperative improvement of peak torque. Test-retest has high accuracy if measurements are performed with weekly intervals. However, measurements 12 to 39 months after the initial assessment—as in our study—do have a clear risk of influencing the nominal values also on the nonoperated side. Rehabilitation focused on the operated side may also affect the values on the nonrehabilitated, noninjured side. Most of our patients were operated on the nondominated hand, where it is known that the peak torque is lower than on the dominant side.5,10 These presumptive confounding factors led us to use the improvement in percentage of forearm peak pronation and supination torque—comparing the operated side to the nonoperated side—as our primary outcome measurement in this study.

There are several limitations to this study. The study consists of a small case series. Twenty months is a relatively short-term follow-up. There are other presumptive confounding factors, which may affect the peak torque (ie, pain, fear of pain, other associated injuries, impaired DRUJ rotation movement, disuse-induced atrophy of forearm rotator muscles), not analyzed in this study. No functional scores (Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand, Patient-Rated Wrist Evaluation, etc) were used.

However, to our knowledge, this is the first published study that has been able to objectively show significant improved peak torque after TFCC reinsertion surgery with achieved DRUJ stability.

Conclusion

In conclusion, postoperative improvement of the forearm peak torque in both pronation and supination was found in patients operated on with a successful reinsertion of TFCC 1B injuries with concomitant DRUJ instability.

Based on previous successful reliability and validity tests, it is reasonable to include this peak torque measuring device in clinical practice both before and after wrist ligament injury surgery as a more objective complement to measurements of range of motion, pain, and functional scores.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: This investigation conforms to the University of Gothenburg Human Research Protection Programme guidelines.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Statement of Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants for being included in the study.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding for this project was provided by Sahlgrenska University Hospital and the University of Gothenburg, Sweden.

ORCID iD: J Fridén  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4270-129X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4270-129X

References

- 1. Anderson ML, Larson AN, Moran SL, et al. Clinical comparison of arthroscopic versus open repair of triangular fibrocartilage complex tears. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33:675-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Andersson JK, Åhlén M, Andernord D. Open versus arthroscopic repair of the triangular fibrocartilage complex: a systematic review. J Exp Orthop. 2018;5(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s40634-018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Andersson JK, Andernord D, Karlsson J, et al. Efficacy of magnetic resonance imaging and clinical tests in diagnostics of wrist ligament injuries: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2015;31:2014-2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Andersson JK, Axelsson P, Strömberg J, et al. Patients with triangular fibrocartilage complex injuries and distal radioulnar joint instability have reduced rotational torque in the forearm. J Hand Surg Eur. 2016;41:732-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Axelsson P, Fredrikson P, Nilsson A, et al. Forearm torque and lifting strength: normative data. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43(7):677.e1-677.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2017.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Axelsson P, Kärrholm J. New methods to assess forearm torque and lifting strength: reliability and validity [published online ahead of print February 14, 2018]. J Hand Surg Am. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. LaStayo P, Weiss S. The GRIT: a quantitative measure of ulnar impaction syndrome. J Hand Ther. 2001;14:173-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lindau T, Runnquist K, Aspenberg P. Patients with laxity of the distal radioulnar joint after distal radial fractures have impaired function, but no loss of strength. Acta Orthop Scand. 2002;73:151-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Luchetti R, Atzei A, Cozzolino R, et al. Comparison between open and arthroscopic-assisted foveal triangular fibrocartilage complex repair for post-traumatic distal radio-ulnar joint instability. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2014;39:845-855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Matsuoka J, Berger RA, Berglund LJ, et al. An analysis of symmetry of torque strength of the forearm under resisted forearm rotation in normal subjects. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:801-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mrkonjic A, Geijer M, Lindau T, et al. The natural course of traumatic triangular fibrocartilage complex tears in distal radial fractures: a 13-15 year follow-up of arthroscopically diagnosed but untreated injuries. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:1555-1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. O’Sullivan LW, Gallwey TJ. Forearm torque strengths and discomfort profiles in pronation and supination. Ergonomics. 2005;6:703-721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Palmer AK. Triangular fibrocartilage complex lesions: a classification. J Hand Surg Am. 1989;14:594-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schmauss D, Pöhlmann S, Lohmeyer JA, et al. Clinical tests and magnetic resonance imaging have limited diagnostic value for triangular fibrocartilaginous complex lesions. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2016;136:873-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tang JB, Giddins G. Why and how to report surgeons’ levels of expertise. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2016;41:365-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tay SC, Tomita K, Berger RA. The “ulnar fovea sign” for defining ulnar wrist pain: an analysis of sensitivity and specificity. J Hand Surg Am. 2007;32:438-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]