Abstract

background

Veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA ECMO) can be vital to support patients in severe or rapidly progressing cardiogenic shock. In cases of left ventricular distension, left ventricular decompression during VA ECMO may be a crucial factor influencing the patient outcome. Application of a double lumen arterial cannula for a left ventricular unloading is an alternative, straightforward method for left ventricular decompression during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in a veno-arterial configuration.

objectives

The purpose of this paper is to use a mathematical model of the human adult cardiovascular system to analyse the left ventricular function of a patient in cardiogenic shock supported by veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation with and without the application of left-ventricular unloading using a novel double-lumen arterial cannula.

methods

A lumped model of cardiovascular system hydraulics has been coupled with models of non-pulsatile VA ECMO, a standard venous cannula and a drainage lumen of a double lumen arterial cannula. Cardiogenic shock has been induced by decreasing left ventricular contractility to 10% of baseline normal value.

results

The simulation results indicate that applying double lumen arterial cannula during VA ECMO is associated with reduction of left ventricular end-systolic volume, end-diastolic volume, end-systolic pressure and end-diastolic pressure.

conclusions

A double lumen arterial cannula is a viable alternative less invasive method for LV decompression during VA ECMO. However, to allow for satisfactory ECMO flow, the cannula design has to be revisited.

Keywords: ECMO, model, circulation, double lumen cannula, cannula, modelica

Introduction

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in a veno-arterial configuration (VA ECMO) is a method widely used to support circulation during the most severe conditions of heart failure or cardiac arrest refractory to standard resuscitation methods. The major indication for a VA ECMO is a severe or rapidly progressing cardiogenic shock 1,2

The introduction of VA ECMO to the clinic brought several unresolved issues. VA ECMO is associated with a significant increase of left ventricular (LV) afterload 1,3. In the presence of a severe dysfunction, the LV is unable to eject the blood against an increased afterload caused by the ECMO flow. In extreme situations, the aortic valve may fail to open even during a systole, which in turn can lead to LV overload with distension, increased wall stress and increased myocardial oxygen consumption 4 Truby et al. 5 report, that 36% of their patients developed a LV distension and that ventricular decompression was required in 16% of all their ECMO patients. In such cases, adequate LV decompression may be an important factor associated with patient outcome 2,6.

Various percutaneous and surgical techniques are used to accomplish LV decompression and reduce the elevated left atrial pressure during VA ECMO therapy 7,8. Unfortunately, all of the currently reported methods require further intervention, which increases the invasiveness of the ECMO therapy and can lead to additional complications such as infection, bleeding and prolonged recovery times 9–11.

As of the date of publication, there is no consensus about the appropriate method and timing of the decompression 8,12,13. Under these circumstances, further studies are required to establish the optimal LV unloading method. Donker et al. 13 present comparison of various methods for LV decompression in a simulation study. A double lumen arterial cannula (DLAC) can potentially be used as an alternative method 14 possessing the advantage of being less invasive than others currently in use. A novel DLAC consists of a single arterial cannula having two continuous lumens, a longer and a shorter one. The end of the shorter lumen is positioned in the aorta and serves as a blood infusion lumen. The end of the longer lumen is introduced in the LV through the aortic valve and serves as a blood intake lumen. With this arrangement, oxygenated blood is returned to the aorta and the LV is decompressed by one single cannula. Mathematical modeling and computer simulation can provide relevant mechanistic insights and enhance the pathophysiological understanding of complex interactions between ECMO and the circulatory system.

The aim of this study is to assess, using a mathematical model, the left ventricular function of a patient with cardiogenic shock during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in a veno-arterial configuration with and without LV unloading using the DLAC. The complex nature of the withdrawn flow division between a venous cannula (a thick cannula, low pressure) and a left ventricle drainage lumen of a double-lumen arterial cannula (high systolic pressure, a thin and long lumen) was simulated, together with its effects on LV performance. Moreover, to better understand the system, we developed a demonstrational web simulator 15, built from a simplified version of the presented model. Both employed models are implemented in an extendable object-oriented Modelica language and Physiolibrary and are freely available as an open-source toolbench 16 for further investigations.

Methods

For the purpose of the simulation, the whole system was modeled in Modelica (an object-oriented equation-based modeling language) using the modeling environment Dymola 2018 (Dassault Systemes) and components from Physiolibrary 2.3.2-beta 17 (www.phvsiolibrarv.org). Physiolibrary is a free open-source Modelica library for modeling physiological systems. The equations can be expressed declaratively and the Modelica tool derives computation causality based on the context upon a compilation 18.

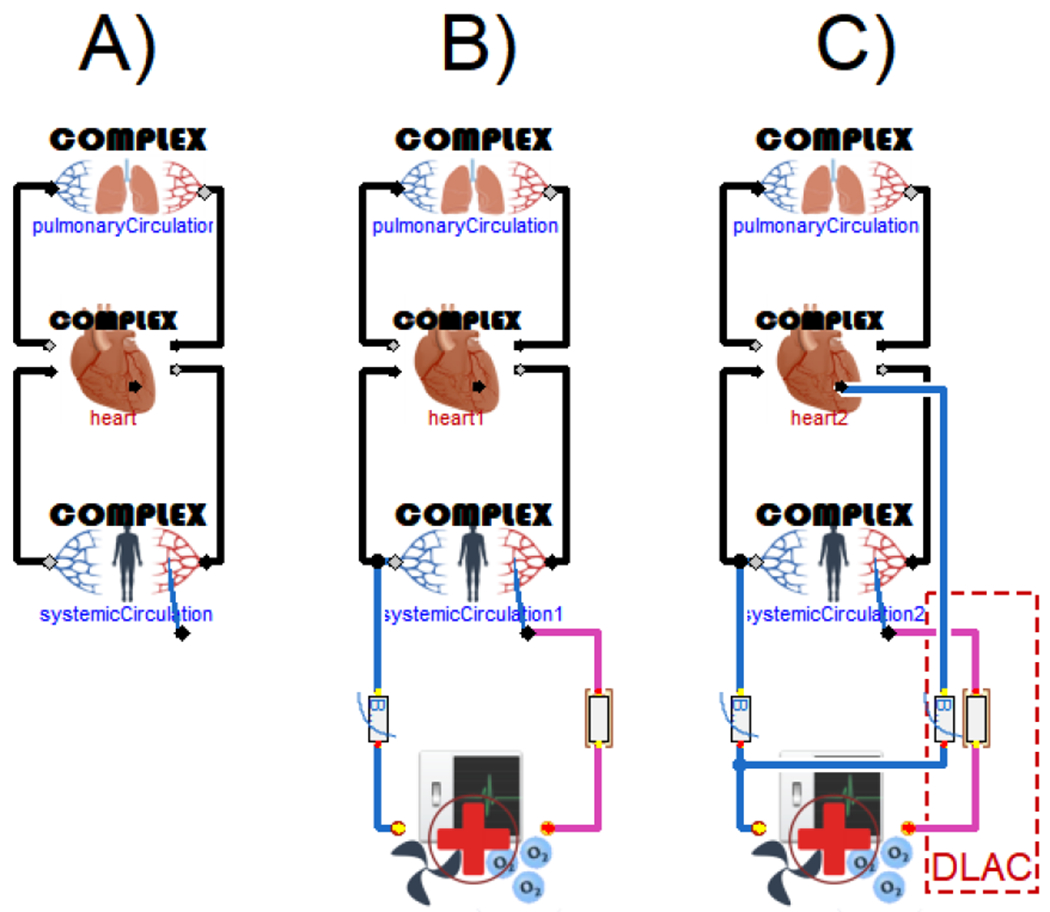

In this study we employed a mathematical beat-to-beat lumped model of cardiovascular flow dynamics. From a set of cardiovascular models presented by Jezek 19 we chose the “Complex” model (Figure 3 A), which already includes a modified version of a CircAdapt 20 model, with heart valves adapted from Mynard 21 and a coronary circuit from 22 The adaptation was set only for peripheral (both systemic and pulmonary) resistances, no other regulations were employed. The used model is described in more detail in Jezek et al19, including model source code. We connected the cardiovascular model to a model of non-pulsatile ECMO by a non-linear cannula model (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

The model of a cardiovascular system (A), the model of a cardiovascular system with VA ECMO and standard cannulas (B), and the model of a cardiovascular system with VA ECMO and a DLAC application (C), where the drainage lumens are modeled as an exponential resistances.

For the demonstrative application however, a simplified model of cardiovascular dynamics had to been used due to the computational complexity of the model described above. Instead of CircAdapt, the model has been based on much computationally simpler Smith model 23, as also discussed and implemented in Jezek et al19

Cannulas

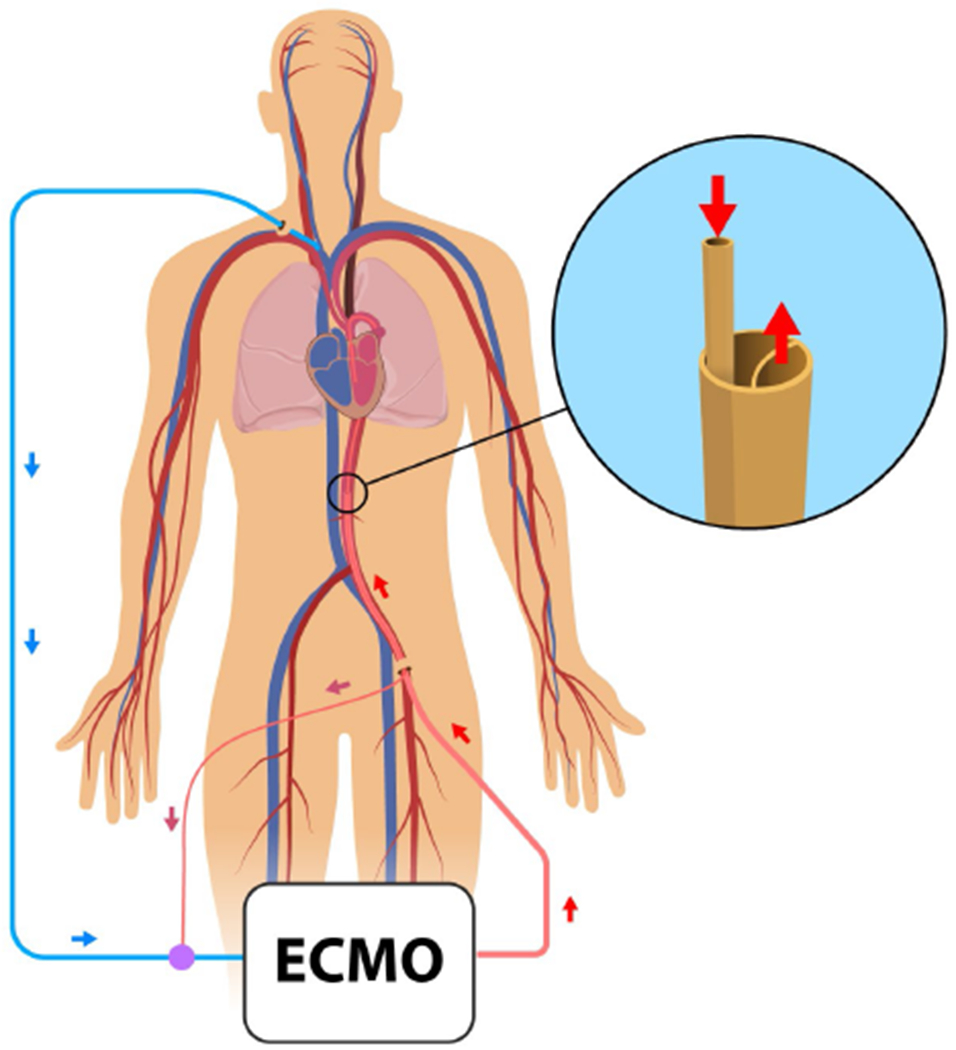

The specific cannulas used in the simulation study were chosen because they are likely candidates for use in future porcine experimental study. The venous blood is drained by a 19 Fr venous cannula (MAQUET Cardiopulmonary GmbH, Germany) and returned to the circulation by a DLAC prototype. The DLAC prototype is created by a 23 Fr Avalon Elite double-lumen venous cannula (DLVC) (MAQUET Cardiopulmonary GmbH, Germany) and a 120 cm 10 Fr pigtail catheter (Cook Ireland Ltd., Ireland). The reinfusion lumen of a double-lumen cannula serves to return the blood to the circulation, whereas the drainage lumen is used solely for a left ventricle unloading. The 120 cm 10 Fr catheter is inserted through the drainage lumen of a DLVC cannula to reach from the insertion point to the left ventricle (Figure 1) and thus form a DLAC prototype.

Figure 1:

Schematics showing LV unloading using the DLAC during VA ECMO and a detail of the DLAC prototype

The non-linear flow-pressure drop characteristics of the cannulas were fitted by an exponential function in the form:

where the dp [Pa] stands for the pressure drop on the cannula, Q [m3s−1] is a flow through the cannula and A [Pa.s/m3] and B [-] represent the fitted parameters listed in the Table 1.

Table 1:

Parameters of the cannulas.

| A [Pa.s/m3] | B [-] | |

|---|---|---|

| Venous cannula 19 Fr | 9.82e12 | 1.971287 |

| DLAC infusion lumen | 2.88e12 | 1.822029 |

| LV drain 10Fr lumen of the double lumen cannula | 1.11e13 | 1.919743 |

| LV drain 10Fr (inserted in DLAC) rescaled to 120 cm | 1.22e14 | 1.919743 |

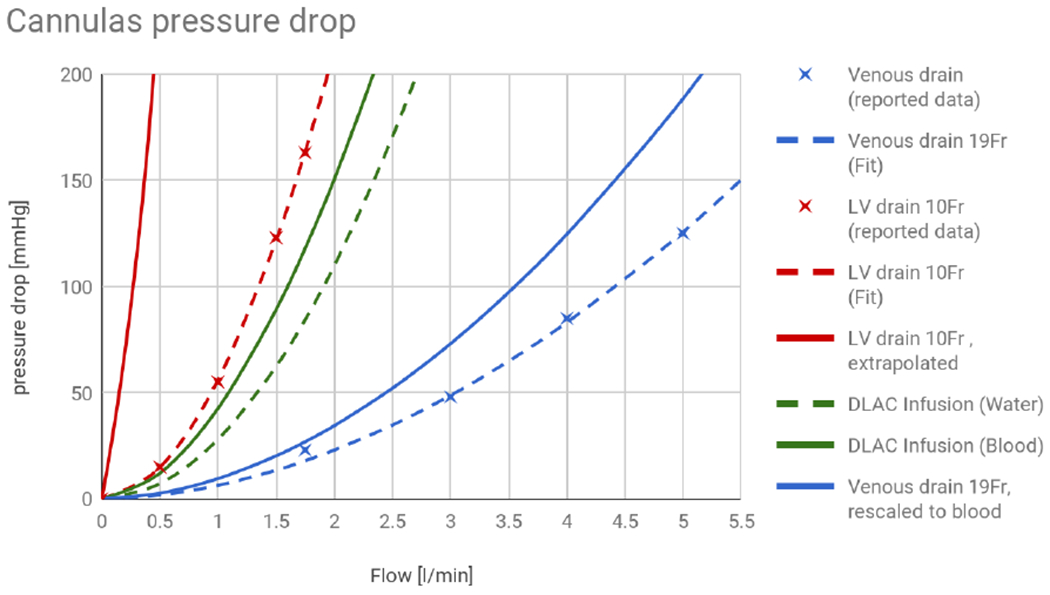

The venous cannula and a drainage lumen of the DLVC models were initially fitted to water flow characteristics reported by the manufacturer 24,25, as no relevant data for blood were available. However, the characteristic of the reinfusion lumen of the DLVC was fitted to values measured with blood (normal hematocrit of 40%) by Wang et al. 26 and subsequently compared to values for water provided by the manufacturer 24 (Figure 2). This comparison revealed only a slight increase in pressure drop infusing blood rather than water with a ratio of 1.5 - 1.3. The characteristics of drain cannulas were then rescaled to blood by the maximal ratio of 1.5. Since both cannulas were rescaled linearly and the ECMO model uses fixed blood flow as an input, scaling from water to blood affects only the observed pressure drop on the drain cannulas and nothing else.

Figure 2:

Pressure drop as a function of flow for a standard venous cannula (blue) and a left ventricle drain through the 10 Fr drainage lumen of a DLAC (red, striped), rescaled to the length required to reach into the ventricle. The fit is based on data measured on water reported by the manufacturer. Infusion lumen of the DLAC has been fitted to data measured with blood (green) and compared to the data provided by the manufacturer (green, striped).

The respective fit is shown in Figure 2. The drainage lumen of a DLAC for an LV drain was also linearly rescaled to the length 120 cm of the drain catheter to reach the left ventricle.

Experimental setting

To simulate severe cardiogenic shock, the contractility of the left ventricular wall was decreased by 90%. After induction of cardiogenic shock, the ECMO model with standard cannulas had been applied. VA ECMO provides right atrium-to-aortic circulatory support. The applied ECMO model simulates blood withdrawal from the right atrium by a venous cannula and returning to the aorta by an arterial cannula. (Figure 3 B).

A second simulation protocol was run where the arterial cannula was replaced by a DLAC. Accordingly, the blood was drawn from the right atrium by the venous cannula and from the LV by the drainage lumen of a DLAC, and returned to the aorta by the reinfusion lumen of a DLAC. The drainage lumen of a DLAC was connected to the venous part of a VA ECMO circuit (Figure 3 C). The model used in the study is publicly available 16.

LV end systolic volume (ESV), LV end-diastolic volume (EDV), LV end-systolic pressure (ESP) and LV end-diastolic pressure (EDP) were investigated. The mean arterial pressure (MAP) was used as an indicator of the circulation effectiveness. The heart rate was constant (70 bpm) for all simulations. To observe the effects of DLAC in wide range of ECMO flows, we use mathematical modeling to quantify the flows not currently used or even obtainable in clinical practice. The simulations were conducted at ECMO flow rates from 0.1 to 7 l/min with more detail on flow of 3 l/min, where the pressure on the simulated ECMO circuit outlet (380 mmHg) is kept below the maximal pressure of 400 mmHg, recommended by the ELSO guidelines 27

Results

In this study, the simulation results of left ventricular functional parameter are presented for healthy person, a patient with cardiogenic shock, a patient with the cardiogenic shock under the ECMO and a patient with the cardiogenic shock under ECMO with DLAC application. Simulation results of LV functional parameters of a healthy person and the patient with cardiogenic shock are presented in the Table 2.

Table 2:

Simulation results of LV functional parameters of a healthy person and a patient with cardiogenic shock.

| Parameter | ESV [ml] | EDV [ml] | SP [mmHg] | DP [mmHg] | MAP [mmHg] | CO [l/min] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy person (LV contractility 100 %) | 63 | 141 | 125 | 3 | 96 | 5.2 |

| Cardiogenic shock (LV contractility 10%) | 105 | 139 | 53 | 12 | 41 | 2.2 |

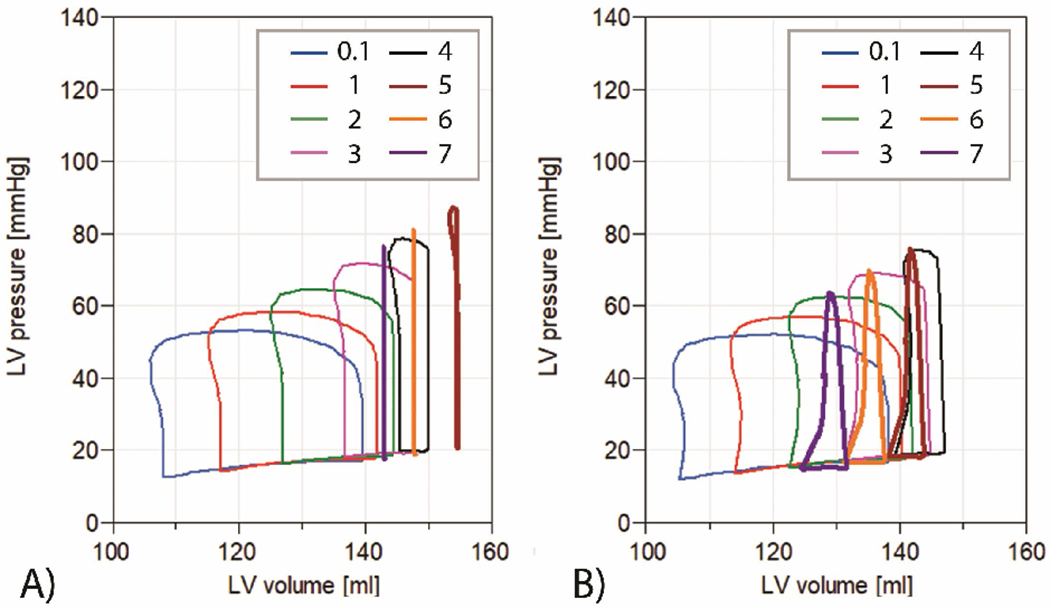

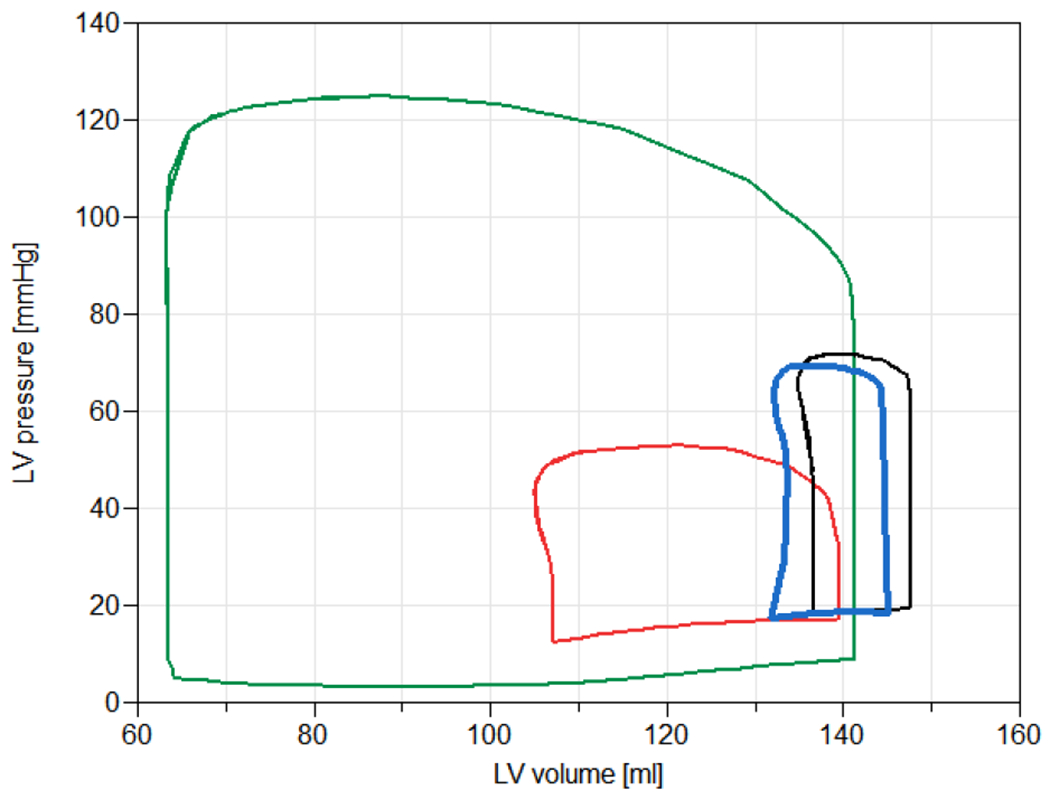

The model simulation with the cardiogenic shock under ECMO indicated that the increasing ECMO pump flow leads to a improvement of the circulation status (represented by the MAP) At the same time, we can observe the effect of ECMO pump flow on the LV parameters by the increase of ESV, EDV, SP, and DP (Table 3). The pressure-volume (PV) loops shrink in size and become narrower with higher ECMO flows (Figure 4 A), which results in a reduced pressure-volume area. Such results have already been observed, e.g. by Donker et al.8. The shift of the PV loops to the left is caused by the ECMO venous drainage and thus lower LV filling.

Table 3.

Simulation results of LV functional parameters of a patient with cardiogenic shock under the ECMO.

| ECMO flow [l/min] | ESV [ml] | EDV [ml] | SP [mmHg] | DP [mmHg] | MAP [mmHg] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 106 | 139 | 53 | 13 | 42 |

| 1 | 115 | 141 | 58 | 14 | 48 |

| 2 | 125 | 144 | 64 | 16 | 56 |

| 3 | 135 | 148 | 72 | 18 | 65 |

| 4 | 144 | 150 | 78 | 20 | 74 |

| 5 | 153 | 155 | 87 | 21 | 85 |

| 6 | 148 | 148 | 81 | 19 | 102 |

| 7 | 143 | 143 | 76 | 17 | 119 |

Figure 4.

A) Simulation results of LV PV loops of a patient with cardiogenic shock under VA ECMO. ECMO flow is from 0.1 to 7 l/min. The aortic valve remain closed, even during systole, when ECMO flow reaches 6 l/min and 7 l/min.

B) Simulation results of LV PV loop of a patient with cardiogenic shock under the ECMO with DLAC application. ECMO flow is from 0.1 l/min to 7 l/min. The aortic valve remain closed, even during systole, when ECMO flow reaches 5 l/min, 6 and 7 l/min and the LV is sufficiently unloaded by DLAC.

During simulations with the LV unloading using DLAC, a decrease in ESV, EDV, SP, EDP along with an increase in MAP, is observed when compared to a standard arterial cannula (Table 4). With an increasing ECMO pump flow, the drainage lumen flow is proportionally increased. As a result of the LV unloading, PV loops have a much larger low-volume base (Figure 5). During the flow of 7 l/min the aortic valve remains closed during the whole cardiac cycle.

Table 4.

Simulation results of LV functional parameters of a the patient with the cardiogenic shock under the ECMO with DLAC application.

| ECMO flow [l/min] | ESV [ml] | EDV [ml] | SP [mmHg] | DP [mmHg] | MAP [mmHg] | LVUF [ml/min] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *0.1 | 104 | 137 | 52 | 12 | 41 | 182 |

| 1 | 113 | 140 | 57 | 13 | 47 | 211 |

| 2 | 122 | 141 | 62 | 15 | 55 | 266 |

| 3 | 131 | 144 | 69 | 17 | 63 | 331 |

| 4 | 139 | 146 | 75 | 19 | 72 | 401 |

| 5 | 138 | 143 | 76 | 18 | 85 | 467 |

| **6 | 131 | 136 | 70 | 16 | 102 | 532 |

| **7 | 124 | 130 | 64 | 15 | 119 | 600 |

During a low ECMO flow a reverse flow through a venous cannula is observed.

The aortic valve does not fully open at all.

Figure 5.

Simulation results of PV loop of a healthy person (green), a patient with cardiogenic shock (red), a patient with the cardiogenic shock during VA ECMO therapy (black), and a patient with the cardiogenic shock under the ECMO with DLAC application (blue). The ECMO flow was set to 3 l/min for all cases.

LV PV loops area of a healthy person is substantially larger in comparison with LV PV loops area of a person suffering from cardiogenic shock (Figure 5). The results indicate that ECMO does substantially alter the PV loop. LV unloading, during ECMO, shifts the PV loop in physiological direction. These results indicates the improvement of several LV functional parameters during VA ECMO with DLAC application.

Discussion

Study report

The presented study reports the simulation results of a cardiovascular system with cardiogenic shock during VA ECMO with LV unloading by a DLAC prototype. The usage of the ECMO may cause mechanical cardiac overload 13 by increasing the afterload, eventually leading to blood stasis in the LV. In such cases, the patient may benefit from LV unloading. Using the DLAC instead of a standard cannulation results in a decrease in ECMO adverse effects on ESV, EDV, SP and EDP. The proposed configuration offers a less invasive LV unloading than using separate cannulation. Each arterial catheterization is a risky intervention, which may lead to additional complications such as vascular damage, infection, bleeding and prolonged recovery times and therefore shall be minimized.

In the conducted study a minimal ECMO flow was 0.1 for a comparison with the non-ECMO case and a maximal ECMO flow was 7 l/min, which corresponds to maximal flow range of contemporary ECMO pumps. During selected ECMO flow of 3 l/min, currently limited by the size of the outflow lumen, the DLAC does not provide impressive improvements (increase in ESV by 28% vs 24% with DLAC unloading) and does not even help maintain satisfactory MAP. However, during ECMO flows of 5 l/min and above, when the flow through aortic valve is near zero, the DLAC application leads to a significant reduction of the negative effects of ECMO (increase of ESV 46% (from 105 to 153 ml) without and 31% increase (from 105 to 131 138 ml) with DLAC unloading). More tailored DLAC design, which uses the dead space for the infusion lumen, would allow for such higher flows.

Result validation

Models of cardiovascular systems by Jezek et al.19, which were used in the study, were developed to be fully consistent with physiological values. Cardiogenic shock is commonly defined as a physiologic state in which a cardiac pump function is insufficient to perfuse the tissues 28,29 The parameters of cardiogenic shock, induced by decreasing heart contractility, correspond with published parameters (LV filling pressure of >15 mm Hg, cardiac index <2.3 l/min, systolic blood pressure of < 90 mm Hg) 30 and simulation studies 13,31.

During the simulations with ECMO, an increase in MAP and adverse increases in ESV, EDV, SP and EDP were observed. With the help of DLAC, the adverse LV overloading caused by the ECMO was suppressed. These simulation results correspond with animal32 and a human case study 33, which both report improvement of LV functional parameters after LV unloading during VA ECMO.

A recent study by Donker 13 used a similar mathematical approach to compare several types of LV unloading during VA ECMO and obtained similar effects on LV loading as the presented results, however, in those studies a DLAC configuration is not considered. Although DLAC is less effective than methods compared in Donker (compare to Fig 9. in 13), DLAC could offer more straightforward approach while being less invasive than other LV unloading techniques currently used. It is important to note, that in cases where the lungs are damaged the methods based on the reducing afterload by e.g. impella or IABP would result in lower coronary oxygen saturation, because they would be primarily perfused by the lower-oxygenated flow from the native heart, instead of oxygenated ECMO. IABP is therefore not recommended 34

Another method of LV unloading, similar to the proposed DLAC, uses a separate catheterization of the left ventricle, either femoral or subclavian, using catheter of comparable size to the DLAC LV drain lumen (7 – 10 Fr) with results comparable to this study 33,35,36.

The model predicts a decrease in pulmonary circuit flow at higher ECMO flows (from 2.3 l/min without ECMO support to 0.95 l/min with LV unloading and 0.77 l/min without unloading, both at ECMO flow of 3 l/min and even 0.6 l/min with and 0.016 l/min without the unloading at ECMO flow of 5 l/min) due to high venous drainage and subsequent reduction in LV filling during closure of aortic valve. This might suggest the importance of LV unloading also for appropriate pulmonary perfusion. Although this mechanism makes mechanistic sense, to our knowledge it has not been reproduced in a clinical setting, probably because it is difficult to achieve such high venous drain to observe this effect. A case study demonstrated successful LV unloading by draining the pulmonary artery 37, which eventually led to a near suspension of flow through aortic valve. Although the LV functional parameters were not reported, their conclusions support our theory.

Possible adverse effects

The insertion through aortic valve is not without the risk of complications, namely blood clotting and damage to valve or ventricles; nevertheless, the pigtail tip of DLAC drainage lumen is designed to prevent these complications.

High pressure drop per the long drainage lumen does not pose threat, as the shear stress per unit length is kept relatively low due to the total length of the cannula (maximal LV drain shear stress estimated at 30 Pa for 3 l/min and 90 Pa for 5 l/min). As of the nature of flow divider, LV drain parallel to the venous drain will only reduce the overall pressure drop.

The limited reinfusion lumen of the selected DLAC prototype (by sharing its maximal insertion size with the drain lumen) develops an excessive pressure drop at high ECMO flows (Figure 2), which means also high pressure at the ECMO outlet (890 mmHg at 5 l/min). This is well over the maximal recommended pressure in ECMO circuit (400 mmHg)27 and thus it poses a limitation on a maximal ECMO flow, with risks of clotting, cell damage and mechanical failure of the circuitry. In current setting, the specified maximum outlet pressure is already achieved at ECMO flow of 3.1 l/min. Therefore, more investigation is to be performed on cannula sizing and ideal space distribution for drain versus infusion lumen.

Thus, the most important concern is to select cannula large enough to allow adequate arterial outflow, yet fit the patient. In addition, the perfusion of the cannulated limb has to be carefully monitored, as the a. femoralis could be completely obstructed with too large of a cannula.

Study limitations

The present study has several limitations. Typically, cardiovascular regulation such as autonomic regulation of heart rate and contractility act in a complex manner and their effects may vary both inter-individually and intra-individually, therefore it is difficult to take them into account rigorously for the purpose of this study. In particular regulation of the heart rate is not considered here and is currently fixed at 70 beats per minute, the baseline normal of employed models. Typically, the heart rate of the failing heart increases to counteract the lower contractility and maintain the total blood flow, however introducing bodily regulation mechanisms are far from scope of the current study. The model is also sensitive to the initial vascular volume, nevertheless in reality, the volume is carefully regulated. Vasodilators, often administered to counter the LV distension34, diuretics and higher heart rate are possible means to reduce the high afterload, but they were kept static for our simulations to keep the problem tractable in this study. In fact, the argument can be made that the need for a LV decompression comes only if those conservative mechanisms are not sufficient. These simplifications could stand behind different results, however would not impact the total outcome.

Demonstration application

To provide a test bench for further experimentation, we prepared a web-based demonstration application, built on the Bodylight.js platform 38, where one could observe effects of the heart rate, vascular volume, heart contractility and ECMO flow on arterial pressures and PV loops. The cardiovascular model had to be simplified (as stated in Methods section) in order to run on consumer computers in near real-time, which can stand behind different values, but with analogous conclusions. The application is accessible at the Virtual Rat project pages 15.

Cannula recommendations

This simulation study mathematically tests the DLAC prototype, which can be prepared from the material available at the market. To prevent collapsing, the drain cannula had to be thick-coated and armed, which takes additional space. Also, the DLAC profile is not fully used (see the detail on Figure 1). By comparison of the pressure drops, the full profile would allow for about twice as more flow at the same pressure drop (data not shown).

The drain lumen of the DLAC occupies substantial space (about a half), which limits the flow through the infusion lumen. The infusion lumen limits the total ECMO flow and the size of femoral artery limits the DLAC size.

The results would be significantly better, if the DLAC catheter is tailored by the manufacturers to minimize unused space and use it especially for infusion lumen to safely allow for larger ECMO flow.

The important factor for LV drainage is the size of the venous cannula, as there is a passive flow divider. All cannula sizes thus have to be carefully chosen to fit the patient needs 4

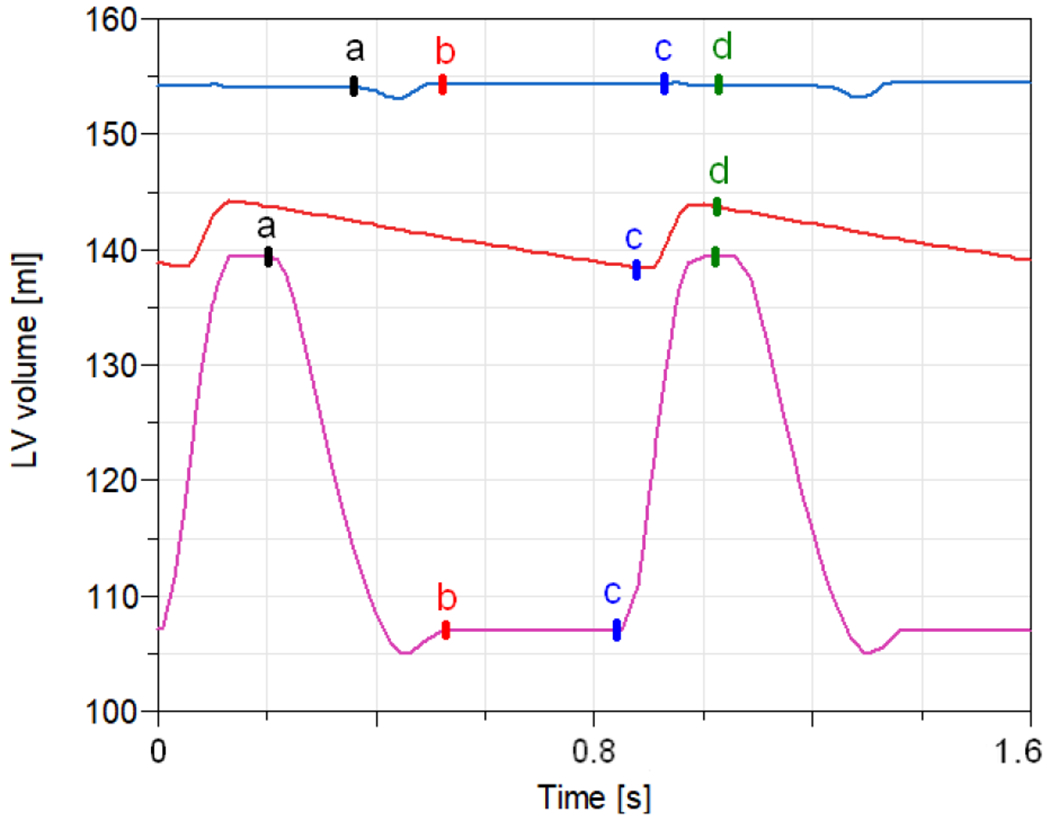

Ventricle volume drainage

In general physiology, end-systole is defined by the aortic valve closing in each cardiac cycle (Figure 6 b). End-diastole is defined by the closing of the mitral valve (Figure 6 d) 29. In a healthy patient, the blood volume does not change between closing the aortic valve and opening the mitral valve. During our simulation, the LV blood volume decreases continuously through the whole cardiac cycle as a consequence of DLAC application. Therefore, we define the ESV parameter as the minimal volume after a cardiac systole (Figure 6 c) instead of rigidly after the aortic valve is closed. In some cases, during simulation, the aortic valve did not open throughout the whole cardiac cycle.

Figure 6.

Simulation results of LV volume during the cardiac cycle. A patient with cardiogenic shock without ECMO application (magenta); a patient with cardiogenic shock with 5 l/min ECMO (blue); a patient with cardiogenic shock with 5 l/min ECMO with DLAC application (red), a - aortic valve opens, b - aortic valve closes, c - mitral valve opens, d - mitral valve closes. Note, that the aortic valve might not open at all in some cases.

Reverse flow

A centrifugal pump have a non-occlusive character. Thereby, in the cases where a zero pump flow is required, clamping the circuit tubing is an essential action to prevent possible backflow39

During DLAC application, both the pre-pump tubing and the drainage lumen of the DLAC should be clamped, otherwise blood from the drainage lumen of the DLAC may flow through the venous cannula to the right atrium, which was observed in this study during low ECMO pump flows (up to approx. 0.65 l/min). The reverse flow occurs due to a high pressure gradient between the drained left ventricle and the right atrium, during a systole. Therefore, we do not recommend a low pump flow during VA ECMO with DLAC applied. This phenomena should be also considered during ECMO weaning.

Conclusion

Insufficient unloading of the left ventricle is one of important pitfalls of the VA ECMO support. Double lumen arterial cannula provides a straightforward and practical method for blood return infusion, alongside with LV unloading capabilities with one single cannula. The conducted simulation study indicates that using a DLAC during VA ECMO as a method of LV unloading improves LV functional parameters when the flow through the aortic valve is near zero (indication for ventricular decompression). Nevertheless, the ECMO flow may be limited by the size of the DLAC reinfusion lumen and thus a careful selection of the DLAC size is necessary. Moreover, production of a specialized DLAC is encouraged.

The suitability of the DLAC have to be yet verified by in vivo experiments and further validation of the DLAC ability to unload the LV during VA ECMO is required, as well as its potential adverse effects.

The model used in the present work enables to investigate the influence of an ECMO system in different configurations on a cardiovascular system. An accessible demonstration web application is made available to public15, alongside with the model sources16.

Acknowledgements

We thank to Martin Brož for graphical work on the figures. The work has been supported by the grant number NIH HL139813.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declare no conflicting interests.

References

- 1.Napp LC, Kuhn C, Bauersachs J. ECMO in cardiac arrest and cardiogenic shock. Herz 2017; 42: 27–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meani P, Gelsomino S, Natour E, et al. Modalities and Effects of Left Ventricle Unloading on Extracorporeal Life support: a Review of the Current Literature. Eur J Heart Fail 2017; 19 Suppl 2: 84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ostadal P, Mlcek M, Kruger A, et al. Increasing venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation flow negatively affects left ventricular performance in a porcine model of cardiogenic shock. J Transl Med 2015; 13: 266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strunina S, Hozman J, Ostadal P. Relation Between Left Ventricular Unloading During Ecmo And Drainage Catheter Size Assessed By Mathematical Modeling. Acta Polytech Scand Chem Technol Ser 2017; 57: 367. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Truby LK, Takeda K, Mauro C, et al. Incidence and Implications of Left Ventricular Distention During Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Support. ASAIO J 2017; 63: 257–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alhussein M, Osten M, Horlick E, et al. Percutaneous left atrial decompression in adults with refractory cardiogenic shock supported with veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Card Surg 2017; 32: 396–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strunina S, Ostadal P . Left ventricle unloading during veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Current Research: Cardiology; 3, https://www.pulsus.com/scholarly-articles/left-ventricle-unloading-during-venoarterial-extracorporeal-membrane-oxygenation.html (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donker DW, Brodie D, Henriques JPS, et al. Left ventricular unloading during veno-arterial ECMO: a review of percutaneous and surgical unloading interventions. Perfusion 2018; 267659118794112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kussmaul WG 3rd, Buchbinder M, Whitlow PL, et al. Rapid arterial hemostasis and decreased access site complications after cardiac catheterization and angioplasty: results of a randomized trial of a novel hemostatic device. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995; 25: 1685–1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merrer J, De Jonghe B, Golliot F, et al. Complications of femoral and subclavian venous catheterization in critically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001; 286: 700–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strunina S, Hozman J, Ostadal P. The peripheral cannulas in extracorporeal life support. Biomed Tech. Epub ahead of print 12 April 2018 DOI: 10.1515/bmt-2017-0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brunner M-E, Banfi C, Giraud R. Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in Refractory Cardiogenic Shock and Cardiac Arrest In: Firstenberg MS (ed) Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: Advances in Therapy. InTech, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donker DW, Brodie D, Henriques JPS, et al. Left Ventricular Unloading During Veno-Arterial ECMO: A Simulation Study. ASAIO J 2019; 65: 11–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strunina S, Hozman J, Ošt’ádal P. A cannula containing a base tube with two adjacent longitudinally leading lumens. Excerpt from the database ofpatents and utility models, https://isdv.upv.cz/webapp/webapp.pts.det?xprim=10225884&lan=en (2018, accessed 20 July 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeẑek F ECMO DLAC model demonstration. The Virtual Physiological Rat Project, http://virtualrat.org/models/ecmo-dlac-model-demonstration-0 (2019, accessed 25 April 2019).

- 16.Jeẑek F. Physiolibrarymodels. GitHub, https://github.com/filip-jezek/Physiolibrary.models (accessed 20 July 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mateják M, Kulhánek T, Šilar J, et al. Physiolibrary - Modelica library for Physiology. In: 10th International Modelica Conference Lund, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mateják M Physiology in Modelica. MEFANET Journal 2014; 2: 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ježek F, Kulhánek T, Kalecký K, et al. Lumped models of the cardiovascular system of various complexity. Biocybernetics and Biomedical Engineering 2017; 37: 666–678. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arts T, Lumens J, Kroon W, et al. Control of Whole Heart Geometry by Intramyocardial Mechano-Feedback: A Model Study. PLoS Comput Biol; 8 Epub ahead of print 2 September 2012 DOI: 10.1371/joumal.pcbi.l002369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mynard JP, Davidson MR, Penny DJ, et al. A simple, versatile valve model for use in lumped parameter and one-dimensional cardiovascular models. Int J Numer Meth Biomed Engng 2012; 28: 626–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bovendeerd PHM, Borsje P, Arts T, et al. Dependence of Intramyocardial Pressure and Coronary Flow on Ventricular Loading and Contractility: A Model Study. Ann Biomed Eng 2006; 34: 1833–1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith BW, Chase JG, Nokes RI, et al. Minimal haemodynamic system model including ventricular interaction and valve dynamics. Med Eng Phys 2004; 26: 131–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maquet, Getinge Group. Avalon Elite Bi-Caval Dual Lumen Catheter (Datasheet). {Maquet, Getinge Group; }, https://www.getinge.com/siteassets/products-a-z/avalon-elite-bi-caval-dual-lumen-catheter/avalonelite_mcp_br_10012_en_l_screen.pdf?disclaimerAccepted=yes (Date unknown). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maquet Getinge Group. Canules HLS Des solutions du drainage a la reinjection, https://www.maquet.com/globalassets/products/canules-hls/brochure-fr---canules-hls.pdf (2017).

- 26.Wang S, Force M, Kunselman AR, et al. Hemodynamic Evaluation of Avalon Elite Bi-Caval Dual Lumen Cannulas and Femoral Arterial Cannulas. Artif Organs 2019; 43: 41–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Extracorporeal Life Support Organization. ELSO Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Extracorporeal Life Support. Version 1.4 August 2017, Extracorporeal Life Support Organization, https://www.elso.org/Portals/0/ELSO%20Guidelines%20General%20All%20ECLS%20Version%201_4.pdf (August 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tewelde SZ, Liu SS, Winters ME. Cardiogenic Shock. Cardiol Clin 2018; 36: 53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silverthom DU. Human Physiology: An Integrated Approach. Pearson Education, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hochman JS, Magnus Ohman E. Cardiogenic Shock. John Wiley & Sons, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Broome M, Donker DW. Individualized real-time clinical decision support to monitor cardiac loading during venoarterial ECMO. J Transl Med 2016; 14: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guirgis M, Kumar K, Menkis AH, et al. Minimally invasive left-heart decompression during venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: an alternative to a percutaneous approach. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2010; 10: 672–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barbone A, Malvindi PG, Ferrara P, et al. Left ventricle unloading by percutaneous pigtail during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2011; 13: 293–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rupprecht L, Florchinger B, Schopka S, et al. Cardiac decompression on extracorporeal life support: a review and discussion of the literature. ASAIO J 2013; 59: 547–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong TH, Byun JH, Yoo BH, et al. Successful Left-Heart Decompression during Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in an Adult Patient by Percutaneous Transaortic Catheter Venting. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2015; 48: 210–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fumagalli R, Bombino M, Borelli M, et al. Percutaneous bridge to heart transplantation by venoarterial ECMO and transaortic left ventricular venting. Int J Artif Organs 2004; 27: 410–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Avalli L, Maggioni E, Sangalli F, et al. Percutaneous left-heart decompression during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: an alternative to surgical and transeptal venting in adult patients. ASAIO J 2011; 57: 38–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silar J, Polak D, Mladek A, et al. Bodylight.js - toolchain for authoring in-browser simulators. JMIR Preprints, https://preprints.jmir.org/preprint/14160 (2019, accessed 23 April 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang S, Chin BJ, Gentile F, et al. Potential Danger of Pre-Pump Clamping on Negative Pressure-Associated Gaseous Microemboli Generation During Extracorporeal Life Support--An In Vitro Study. Artif Organs 2016; 40: 89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]