Abstract

Background

Otitis media is inflammation of the middle ear, comprising a spectrum of diseases. It is the commonest episode of infection in children, which often occurs after an acute upper respiratory tract infection. Otitis media is ranked as the second most important cause of hearing loss and the fifth global burden of disease with a higher incidence in developing worlds like Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Therefore, this systematic review is aimed to quantitatively estimate the current status of bacterial otitis media, bacterial etiology and their susceptibility profile in sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods

A literature search was conducted from major databases and indexing services including EMBASE (Ovid interface), PubMed/MEDLINE, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, Cochrane Library, WHO African Index-Medicus and others. All studies (published and unpublished) addressing the prevalence of otitis media and clinical isolates conducted in sub-Saharan Africa were included. Format prepared in Microsoft Excel was used to extract the data and data was exported to Stata version 15 software for the analyses. Der-Simonian-Laird random-effects model at a 95% confidence level was used for pooled estimation of outcomes. The degree of heterogeneity was presented with I2 statistics. Publication bias was presented with funnel plots of standard error supplemented by Begg’s and Egger’s tests. The study protocol is registered on PROSPERO with reference number ID: CRD42018102485 and the published methodology is available from http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/CRD42018102485.

Results

A total of 33 studies with 6034 patients were included in this study. All studies have collected ear swab/discharge samples for bacterial isolation. The pooled isolation rate of bacterial agents from the CSOM subgroup was 98%, patients with otitis media subgroup 87% and pediatric otitis media 86%. A univariate meta-regression analysis indicated the type of otitis media was a possible source of heterogeneity (p-value = 0.001). The commonest isolates were P. aeruginosa (23–25%), S. aureus (18–27%), Proteus species (11–19%) and Klebsiella species. High level of resistance was observed against Ampicillin, Amoxicillin-clavulanate, Cotrimoxazole, Amoxicillin, and Cefuroxime.

Conclusion

The analysis revealed that bacterial pathogens like P. aeruginosa and S. aureus are majorly responsible for otitis media in sub-Saharan Africa. The isolates have a high level of resistance to commonly used drugs for the management of otitis media.

Keywords: Otitis media, Bacterial isolates, Antimicrobial resistance, Sub-Saharan Africa, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Background

Otitis media is an inflammation of the tympanic membrane and middle ear with a spectrum including acute otitis media, otitis media with effusion and chronic suppurative otitis media [1, 2]. Otitis media often occur secondary to acute upper respiratory tract infections, can also be caused by allergy and changes of the middle ear or Eustachian tube anatomically or functionally [3]. Worldwide around 1.23 billion people are affected by otitis media, thus it is ranked as the fifth global burden of disease and the second cause of hearing loss [2, 4]. Children are the most affected groups and it is one of the commonest disease responsible for receiving antibiotics among children [4–6]. Otitis media is a major chronic disease in low and middle-income countries than in high-income countries. The highest incidence rate reported from Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia [4–8].

Otitis media, especially with a chronic and recurrent form, is associated with complications such as hearing loss, decreased learning capability, and low educational achievement [9]. Around 20,000 people, majorly children under 5 years of age, die every year with the associated complications [7].

Majorly pathogenic bacteria such as non-typable Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Proteus mirabilis, Escherichia coli, and Moraxella catarrhalis are the etiological agents of otitis media [10–15], although viruses and fungi also associated [14–16]. The occurrence of otitis media is directly related to the colonization rate of the nasopharynx by the bacteria [12]. Viral upper respiratory tract infections (URTI), disrupts the mucociliary system, impairs the host’s primary mechanical defense for bacterial invasion and predispose children to acute otitis media (AOM) [12–15]. This study is aimed to quantitatively estimate the isolation rate of bacteria from patients with otitis media (OM), major isolates and resistance of isolates to commonly used antibacterial agents.

Methods

Study protocol

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram [17] was followed for identification of records, screening of titles and abstracts, and evaluation of full texts for inclusion. We have followed the PRISMA checklist [18] throughout the review and the published methodology can be accessed from http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php? ID = CRD42018102485. The study protocol is also registered on PROSPERO with reference number ID: CRD42018102485.

Identification of records and search strategy

Legitimate databases and indexing services like PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE (Ovid interface), ScienceDirect and other supplementary sources, including Google Scholar, World Cat catalog, WHO African Index-Medicus and Cochrane library were visited to carry out the literature search. Relevant findings closely related to bacterial otitis media and isolation of agents were retrieved through advanced search strategies in major databases. HINARI: WHO for developing countries was used to access articles published in subscription-based journals under Science-Direct and Wiley online library. Indexing terms and carefully selected key-words were used to facilitate the search within the specified time (online records from 2009 to 2018). However, there is a deviation from the protocol published on PROSPERO, which stated from 2013 to 2018. The search was expanded back to 2009 to include more studies for subgroup analysis and to have a good pooled estimate. The time frame is set because antimicrobial resistance is a time-sensitive issue and is changing through time.

For systematic identification of records, keywords like Otitis Media [MeSH], Bacteria [MeSH], Africa South of the Sahara [MeSH], Otitis Media with Effusion [MeSH], Otitis Media, Suppurative [MeSH], “middle ear inflammation”, “middle ear effusion”, “secretory otitis media”, “purulent otitis media” and each sub-Saharan country entry term with Boolean operators (AND, OR), and truncation were used. All articles available online until February 25 – March 5, 2019, were considered. Google Scholar and World Cat were used to access gray literature from organizations and online university repositories. There was no language preference set in search strategy for all databases except for Google Scholar search, where the language preference was set to English and French. This deviation from the protocol (articles only English language) was made after observing some studies in the region that were published in the French language.

Screening and eligibility of studies

ENDNOTE version 8.0.1 (Thomson Reuters, Stamford, CT, USA) was used to manage the search results and to identify duplicate records. Records were also checked manually to avoid duplicates due to variation in reference styles across sources followed by a screening of titles and abstracts with predefined inclusion criteria. Two authors (TT and HM) independently evaluated the full texts of selected articles for eligibility and the discrepancies between the two authors’ evaluations were solved by the other authors to come up with a consensus.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients with clinically confirmed otitis media were the study participants. Otitis media was defined as middle ear inflammation with discharge and without a clear indication of the tympanic membrane, and participants with middle ear inflammation with discharge for more than 3 months with a perforated tympanic membrane were considered as chronic suppurative otitis media. Records, published from 2009 to 2018, on the isolation of bacterial pathogens from ear swab or discharge, and susceptibility testing were included regardless of the patient’s clinical characteristics.

Review and original articles conducted outside of sub-Saharan Africa were excluded during initial screening. Articles with data collection period before 2009, having unrelated, missing or insufficient outcomes, and irretrievable full texts (after requesting the corresponding authors) were excluded.

Data extraction

Two authors (TT and HM) independently extracted important data related to study characteristics (country, first author, year of publication, study design, patient characteristics, number of culture-positive results (bacterial), nature of bacterial isolates, and number of isolates) and outcome of interest (number of culture-positive results, number of isolates with prevalence data for each bacterium, and susceptibility test results) using data abstraction format prepared in Microsoft Excel (Data Extraction and Summary sheet).

Critical appraisal of studies

Critical appraisal to assess the internal (systematic error) and external (generalizability) validity of studies and to reduce the risk of biases was conducted according to the Joanna Briggs Institute’s critical appraisal tool adapted for prevalence studies [19] and graded out of 9 points. The mean score of the two authors was taken for final decision and studies with a score greater than or equal to five were included.

Outcome measurements

The primary outcome measure is the prevalence of bacterial otitis media, major isolates and the antimicrobial resistance in sub-Saharan Africa. The measurement regarding antimicrobial resistance was conducted for selected drugs (Ampicillin, Sulfamethoxazole-Trimethoprim (cotrimoxazole), Chloramphenicol, Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, Gentamycin, Ceftriaxone, Cefuroxime, Erythromycin, Tetracycline, and Ciprofloxacin) obtained from patients with presumed or confirmed otitis media.

Data processing and statistical analysis

Stata version 15 was used for analyses of outcome measures after importing data extracted in Microsoft excel format. We have applied the DerSimonian and Laird’s random-effects model for the analyses at a 95% confidence level considering the variation in true effect sizes across the population (clinical heterogeneity). The heterogeneity of studies was determined using I2 statistics. A univariate meta-regression model was performed, with a cutoff value p-value< 0.05, on study characteristics to assess the possible source of heterogeneity. Begg’s and Egger’s tests were used to evaluate the presence of publication bias, and presented with funnel plots of the standard error of proportions [20, 21].

Results

Search results

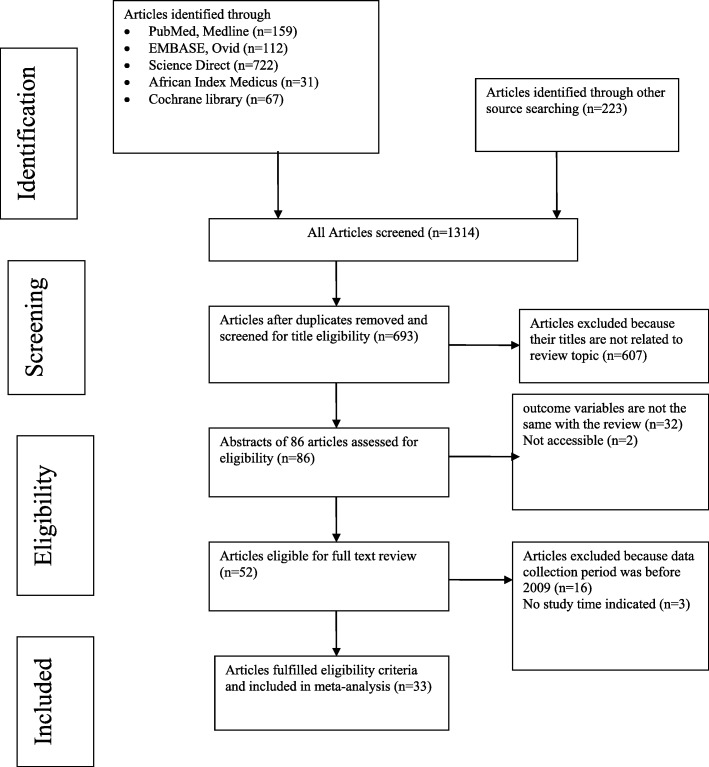

We conducted a systematic review and Meta-analysis per under the PRISMA statement [17]. In our literature search, a total of 1314 records were identified from several sources. From these, 621 duplicate articles were removed with the help of ENDNOTE and manual tracing. The remaining 693 records were screened using their titles and abstracts, and 607 of them were excluded. Eligibility evaluation of full texts was done for 86 records. From these, 32 articles were also excluded as the outcome of interest was missing, insufficient and/or ambiguous, and 2 articles were not accessible in full text [22, 23]. Fifty-two studies were evaluated by a full-text review and 16 studies had data collection period before 2009 and three studies [24–26] have no record of the data collection period. Finally, 33 articles passed the eligibility criteria and quality assessment and hence included in the study (Fig. 1). Thirty-two studies were utilized for the analysis of prevalence, one study has reported only the isolates without the prevalence of otitis media, and only 22 studies were utilized for the assessment of susceptibility testing since the other 11 studies have an incomplete report regarding study outcome and in some studies, the test was done with a variable number of isolates for different drugs.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for Bacterial Otitis Media in sub-Saharan Africa

Study characteristics

As shown in Table 1, a total of 33 studies with 6034 participants were included for systematic review and meta-analysis. Seven of the included studies were retrospective analyses of secondary data (record review) from regional laboratories and hospitals [28, 29, 35, 37, 42, 43, 48]. Fourteen studies were conducted on chronic suppurative otitis media [27, 31, 33, 36, 40–42, 45, 48, 50, 53, 54, 56, 58] and the rest included studies do not indicate the type of otitis media. Seven studies [30, 32, 35, 39, 44, 52, 57] were conducted in children whereas the rest of the studies included patients of all age groups. The average quality scores of studies ranged from 5 to 8 as per the Joanna Briggs Institute scoring scale for prevalence studies (Table 1). All studies have collected ear swab/discharge samples and applied standard microbiological culturing techniques for isolation of bacterial agents and followed the international standard for performing susceptibility testing and interpretation of results (CLSI standards). Concerning the country of study, 14 studies were from Nigeria, 8 studies from Ethiopia, 2 studies from Zambia, and a single study from Angola, South Africa, Sudan, Burkina Faso, Tanzania, Uganda, Ghana, and Malawi.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies describing the prevalence of bacterial otitis media

| Sr.No. | Author | Positive | Sample size | Country | Study design | Population characteristics | Year | Quality score | Number of isolates | Type of sample | Age of participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Afolabi OA et al. (2012) [27] | 134.5 | 135 | Nigeria | CS | patients with CSOM | 2012 | 6 | 138 | Ear discharge | 5-10 yrs. = 46; 11-20 yrs. = 26; 21-30 yrs. = 18; 31-40 yrs. = 20; 41-50 yrs. = 6; 51-60 yrs. = 10; 61-70 yrs. = 14 |

| 2 | Appiah-Korang L., et al. (2014) [28] | 277 | 315 | Ghana | CS® | patients with OM | 2013 | 5 | 322 | Ear swab | <=1 yrs. = 64; 2-4 yrs. = 63; 5-13 yrs. = 55; 14-19 yrs. = 11; 20-44 yrs. = 53; 45-64 yrs. = 19; > = 65 yrs. = 7 |

| 3 | Argaw-Denboba A et.al. (2014) [29] | 1024 | 1225 | Ethiopia | CS® | patients with OM | 2014 | 8 | 1124 | Ear discharge | < 5 yrs. = 153; 5-15 yrs. = 253; 16-35 yrs. = 434; 36-50 yrs. = 105; > = 51 = 47 |

| 4 | Chidozie AH et al. (2015) [30] | 137 | 156 | Nigeria | CS | pediatric patients with OM | 2014 | 7 | 152 | Ear discharge | <=5 yrs. = 137 |

| 5 | Chirwa M., et al. (2015) [31] | 116 | 118 | Malawi | CS | patients with CSOM | 2013 | 8 | 214 | Ear discharge | < 18 yrs. = 64; > = 18 yrs. = 40 |

| 6 | Ejiofor S. O., et al. (2016) [32] | 30 | 40 | Nigeria | CS | pediatric patients with OM | 2015 | 7 | 43 | Ear swab | <=1 yrs. = 22; 2-4 yrs. = 8; 5-7 yrs. = 5; 8-9 yrs. = 5 |

| 7 | Elmustafa M., et al. (2016) [33] | 204 | 217 | Sudan | CS | patients with CSOM | 2013 | 5 | 305 | Ear discharge | < 16 yrs. = 90; 16-30 yrs. = 50; 31-45 yrs. = 37; 46-60 yrs. = 31; > 60 yrs. = 8 |

| 8 | Fayemiwo SA et.al. (2017) [34] | 91 | 98 | Nigeria | CS | patients with OM | 2017 | 6 | 115 | Ear discharge | < 10 yrs. = 54; 11-20 yrs. = 8; 21-30 yrs. = 20; 31-40 yrs. = 4; 41-50 yrs. = 3; > 50 yrs. = 9 |

| 9 | Garba B. I., et al. (2017) [35] | 43 | 53 | Nigeria | CS® | pediatric patients with OM | 2017 | 5 | 45 | Ear swab | 0–5 yrs. = 38; 5–10 yrs. = 10; 10-15 yrs. = 5 |

| 10 | Habibu A. (2015) [36] | 68.5 | 69 | Nigeria | CS | patients with CSOM | 2013 | 5 | 68 | Ear discharge | 0 – 5 yrs. = 14; 6-11 yrs. = 12; 12-17 yrs. = 8; 18-23 yrs. = 1; 24-29 yrs. = 3; 30-35 yrs. = 0; 36-41 yrs. = 0; > 41 yrs. = 1 |

| 11 | Hailu D., et al. (2016) [37] | 296 | 368 | Ethiopia | CS® | patients with OM | 2015 | 5 | 296 | Ear discharge | 0-10 yrs. = 91; 11-20 yrs. = 102; 21-30 yrs. = 51; 31-40 yrs. = 31; 41-50 yrs. = 17; 51-60 yrs. = 3; > 61 yrs. = 1 |

| 12 | Jido BA et al. (2014) [38] | 95 | 110 | Nigeria | CS | Patients with OM | 2011 | 6 | 95 | Ear swab | 0-5 yrs. = 61; 6-10 yrs. = 14; 11-15 yrs. = 5;> = 16 yrs. = 6 |

| 13 | Jik A et al. (2015) [39] | 154 | 182 | Nigeria | CS | pediatric patients with OM | 2015 | 7 | 154 | Ear swab | 1-3 yrs. = 59; 4-6 yrs. = 47; 7-9 yrs. = 30; 10-12 yrs. = 18 |

| 14 | Justin R et al. (2018) [40] | 89.5 | 90 | Uganda | CS | patients with CSOM | 2016 | 5 | 127 | Ear discharge | < 18 yrs. = 47; > 18 yrs. = 42 |

| 15 | Kazeem M. J. and R. Aiyeleso (2016) [41] | 360 | 380 | Nigeria | CS | patients with CSOM | 2015 | 5 | 371 | Ear discharge | < 10 yrs. = 256; 11-20 yrs. = 72; 21-30 yrs. = 26; 31-40 yrs. = 15; 41-50 yrs. = 3; 51-60 yrs. = 7; > 60 yrs. = 1 |

| 16 | Matundwelo N. and C. Mwansasu (2016) [42] | 60.5 | 61 | Zambia | CS® | patients with CSOM | 2016 | 6 | 154 | Ear discharge | 0-7 yrs. = 34; 8-15 yrs. = 26 |

| 17 | Muluye D et al. (2013) [43] | 204 | 228 | Ethiopia | CS® | patients with OM | 2013 | 7 | 204 | Ear discharge | 0-5 yrs. = 51; 6-10 yrs. = 31; 11-15 yrs. = 17; 16-20 yrs. = 21; 21-30 yrs. = 45; 31-40 yrs. = 21; > = 41 yrs. = 18 |

| 18 | Nwogwugwu, NU et al. (2014) [44] | 128 | 152 | Nigeria | CS | pediatric patients with OM | 2014 | 6 | 128 | Ear discharge | no age specific data |

| 19 | Ogah S. and J. Ogah (2016) [45] | 88 | 96 | Nigeria | CS | patients with CSOM | 2013 | 5 | 149 | Ear discharge | 0-10 yrs. = 34; 11-20 yrs. = 28; 21 = 30 yrs. = 16; 31-40 yrs. = 12; 41-50 yrs. = 8; 51-60 yrs. = 6; 61-70 yrs. = 2; 71-80 yrs. = 4 |

| 20 | Ohieku, J. and F. Fakuade (2013) [46] | 107 | 125 | Nigeria | CS | Patients with OM | 2010 | 5 | 117 | Ear swab | 0-2 yrs. = 49; 2-5 yrs. = 20; 6-12 yrs. = 9; 13-18 yrs. = 4; 19-64 yrs. = 24; > = 65 yrs. = 1 |

| 21 | Onifade AK et al. (2018) [47] | Nigeria | CS | Patients with OM | 2015 | 5 | 537 | Ear discharge | |||

| 22 | Orji F. T. and B. O. Dike (2015) [48] | 202 | 206 | Nigeria | CS® | patients with CSOM | 2013 | 5 | 250 | Ear discharge | < 1 yrs. = 12; 1-5 yrs. = 37; 5-15 yrs. = 58; > 15 yrs. = 99 |

| 23 | Ouedraogo RW et al. (2012) [49] | 34 | 41 | Burkina Faso | CS | patients with OM | 2012 | 5 | 36 | Ear swab | no age specific data |

| 24 | Phiri H., et al. (2016) [50] | 98 | 100 | Zambia | CS | patients with CSOM | 2016 | 5 | 169 | Ear discharge | <=5 yrs. = 19; 6-10 yrs. = 7; 11-15 yrs. = 7; 16-20 yrs. = 15; 21-25 yrs. = 7; 26-30 yrs. = 13; 31-35 yrs. = 6; 36-40 yrs. = 8; 41-45 yrs. = 5; 46-50 yrs. = 5; 51-55 yrs. = 2; 61-65 yrs. = 1; 66-70 yrs. = 5 |

| 25 | Seid A et al. (2014) [51] | 171 | 191 | Ethiopia | CS | patients with OM | 2010 | 7 | 207 | Ear discharge | < 5ys = 33; 5-9 yrs. = 18; 10-14 yrs. = 35; 15-19 yrs. = 32; 20-24 yrs. = 20; 25-29 yrs. = 17; 30-34 yrs. = 7; 35-39 yrs. = 10; 40-44 yrs. = 6; 45-49 yrs. = 4; > = 50 yrs. = 9 |

| 26 | Tiedt NJ et al. (2013) [52] | 80 | 86 | South Africa | CS | pediatric patients with OM | 2013 | 6 | 153 | Ear discharge | < 13 yrs. = 86 |

| 27 | Udden F., et al. (2018) [53] | 150 | 152 | Angola | CS | patients with CSOM | 2016 | 5 | 443 | Ear discharge | < 5 yrs. = 34; 5-9 yrs. = 23; 10-14 yrs. = 24; > = 15 yrs. = 55; no age data = 16 |

| 28 | Wasihun A. G. and Y. Zemene (2015) [54] | 157 | 162 | Ethiopia | CS | patients with CSOM | 2015 | 8 | 216 | Ear discharge | 0-5 yrs. = 30; 6-10 yrs. = 41; 11-15 yrs. = 22; 16-20 yrs. = 11; 21-25 yrs. = 23; 26-30 yrs. = 9; > 30 yrs. = 26 |

| 29 | Worku S., et al. (2017) [55] | 154 | 167 | Ethiopia | CS | patients with OM | 2014 | 7 | 171 | Ear discharge | < 15 yrs. = 60; 15-40 yrs. = 81; > 40 yrs. = 26 |

| 30 | Adoga AA et al. (2011) [56]a | 75 | 97 | Nigeria | CS | patients with CSOM | 2009 | 5 | 75 | Ear discharge | 1-10 yrs. = 40; 11-20 yrs. = 23; 21-30 yrs. = 16; 31-50 yrs. = 11; > 50 yrs. = 7 |

| 31 | Hailegiyorgis TT et al. (2018) [57]a | 95 | 196 | Ethiopia | CS | pediatric patients with OM | 2014 | 7 | 95 | Ear swab | < 2 yrs. = 41; 2-4 yrs. = 36; > 4-5 yrs. = 18 |

| 32 | Mushi M. F., et al. (2016) [58]a | 126 | 301 | Tanzania | CS | patients with CSOM | 2014 | 6 | 60 | Ear discharge | 1-10 yrs. = 31; 11-20 yrs. = 52; 21-30 yrs. = 51; 31-40 yrs. = 59; 41-50 yrs. = 55; > 50 yrs. = 33 |

| 33 | Worku M. and M. Bekele (2014) [59]a | 61 | 117 | Ethiopia | CS | patients with OM | 2013 | 6 | 69 | Ear swab | Children = 53; Adult = 64 |

CS cross-sectional, CS® Retrospective cross-sectional, OM Otitis Media, CSOM Chronic Suppurative Otitis Media

aStudies removed from analysis of pooled prevalence by sensitivity analysis

Study outcome measures

Prevalence of bacterial otitis media

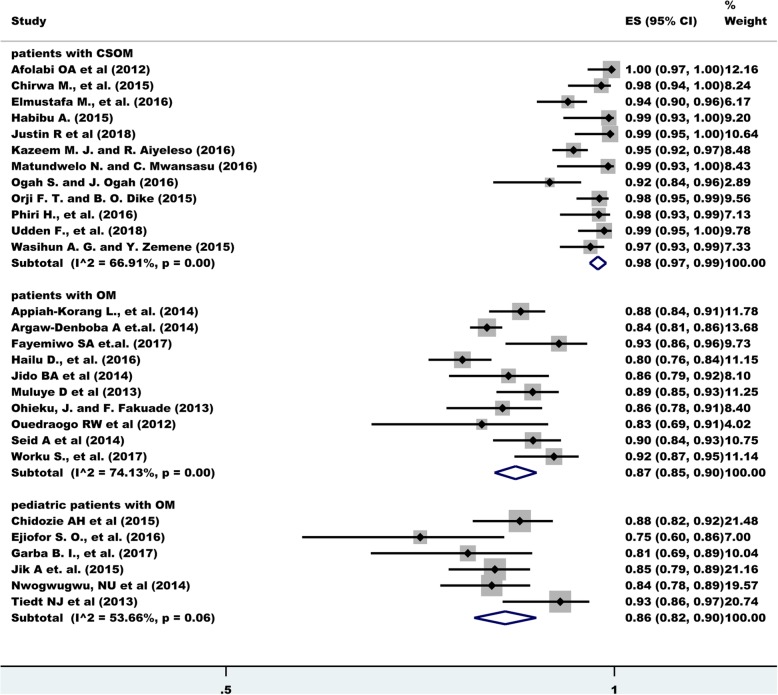

The overall estimate of bacterial isolation was 92% (95% CI: 90.0, 94.0) with a degree of heterogeneity (I2), 93.77%. A change was observed on the degree heterogeneity after excluding the known outliers and, performing subgroup analysis and sensitivity testing based on the type of otitis media and age group. The highest bacterial isolation rate was obtained among patients with chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM) (98%) with a 66.91% degree of heterogeneity. Among patients with otitis media with inclusion of all age groups the prevalence was 87% (I2 = 74.13%) and among pediatric patients with otitis media 86% (I2 = 53.66%) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Frost plot depicting bacterial Otitis Media in sub-Saharan Africa

After a univariate meta-regression analysis, the year of study, country of study, study design, and sample size were not found to be statistically significant, however, the type of otitis media was found to be significant (p-value = 0.001).

Bacterial isolates

From all bacterial isolates, the commonest isolate was Pseudomonas species (majorly P. aeruginosa) (ranging from 23 to 25% across subgroups) followed by S. aureus (18–27%), Proteus species (mainly P. mirabilis), Klebsiella species, Coagulase Negative Staphylococci (CoNS) and Streptococcus species like S. pyogenes, and Enterococcus species. Other gram-negative rods under the Enterobacteriaceae (Citrobacter species, Providencia species, Serratia species, Enterobacter species, and Morganella species) account for 7–11%, but separately they account for less than 5% (Table 2, and Data Extraction and Summary sheet: isolates). On the subgroup analysis, S. aureus was found to be the major isolate except for chronic suppurative otitis media and Streptococcus species were observed to have a relatively higher prevalence in pediatric patients with otitis media (Table 2).

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis of bacterial isolates by type of otitis media

| Bacterial isolate | Type of otitis media, prevalence % (95% CI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with CSOM | Patients with OM | Pediatric patients OM | |||||||

| Pooled prevalence (%) | No of study | I2 (%) | Pooled prevalence (%) | No of study | I2 (%) | Pooled prevalence (%) | No of study | I2 (%) | |

| S. aureus | 18(11–25) | 14 | 96.2 | 23(19–27) | 12 | 88.29 | 27(15–39) | 7 | 94.9 |

| CoNS | 7(2–12) | 4 | 82.5 | 9(4–14) | 6 | 96.98 | 1(0–5) | 1 | |

| Streptococcus spp | 5(3–7) | 10 | 79.18 | 2(1–4) | 8 | 70.79 | 10(4–15) | 5 | 82.7 |

| Pseudomonas spp | 23(18–29) | 14 | 92.47 | 24(18–29) | 12 | 93.95 | 25(16–33) | 7 | 88.33 |

| Proteus spp | 19(15–22) | 12 | 81.00 | 19(14–23) | 12 | 89.68 | 11(5–18) | 6 | 90.29 |

| E. coli | 9(6–11) | 13 | 88.04 | 7(3–10) | 11 | 94.06 | 8(5–11) | 7 | 57.47 |

| Klebsiella spp | 12(9–16) | 12 | 91.15 | 7(5–10) | 11 | 91.01 | 5(1–9) | 4 | 82.95 |

| Other Enterobacteriaceae | 10(2–17) | 5 | 95.73 | 11(6–17) | 6 | 92.31 | 7(1–14) | 3 | |

| S. pneumoniae | 3 (1–6) | 4 | 88.29 | 2 (1–4) | 5 | 92.87 | 6 (3–9) | 4 | 39.46 |

| H. influenzae | 2 (0–3) | 2 | 1 (0–3) | 1 | 8(5–11) | 2 | |||

Four studies have demonstrated the isolation of Acinetobacter species, and Corynebacterium species were isolated by two studies. Anaerobic bacteria were not commonly isolated from the studies, but a study by Chirwa M et al [31] has reported the isolation of Bacteroides species and Peptostreptococcus species.

Though the main objective of this review is bacterial etiologies we found out that fungal pathogens like Candida species and Aspergillus species account for 6% (3–8%) of the etiology for otitis media; only one study has indicated Aspergillus species.

The resistance of isolates to antibacterial agents

Studies have included various drugs for susceptibility testing. We have selected drugs that have been tested in more than 5 studies and accordingly, the analysis was done for Ampicillin, Cotrimoxazole, Cefuroxime, Amoxicillin-clavulanate, Ciprofloxacin, Gentamycin, Chloramphenicol, Amoxicillin, Ceftriaxone, Tetracycline, and Erythromycin.

A higher degree of pooled resistance was observed in Ampicillin (72%, ranging from 69 to 94% across subgroups), Amoxicillin (68, 62–85%), Cotrimoxazole (60, 41–90%), Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (54, 47–61%), and Cefuroxime (51, 17–64%) and. The lowest degree of resistance was found among Ciprofloxacin, Gentamycin, and Chloramphenicol (Table 3, and Data Extraction and Summary sheet: susceptibility). Generally, a higher degree of resistance was observed in pediatric patients with otitis media than the other subgroups.

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis of drug resistance by type of otitis media

| Bacterial isolate | Type of otitis media, prevalence % (95% CI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with CSOM | Patients with OM | Pediatric patients OM | |||||||

| Pooled prevalence (%) | No of study | I2 (%) | Pooled prevalence (%) | No of study | I2 (%) | Pooled prevalence (%) | No of study | I2 (%) | |

| Ampicillin | 70(54–86) | 8 | 98.56 | 69(48–90) | 7 | 99.09 | 94(91–98) | 2 | |

| Cotrimoxazole | 63(47–80) | 7 | 98.03 | 41(11–72) | 6 | 99.58 | 90(78–100) | 3 | |

| Amoxicillin | – | – | – | 62(37–87) | 5 | 98.78 | 85(81–89) | 2 | |

| Ceftazidime | 52(28–76) | 4 | 97.09 | 7(1–16) | 3 | 57(47–66) | 1 | ||

| Chloramphenicol | 32(21–48) | 8 | 95.98 | 25(13–38) | 6 | 97.87 | 55(45–64) | 1 | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 19(12–25) | 10 | 94.36 | 16(9–24) | 6 | 94.23 | 34(12–56) | 3 | |

| Gentamycin | 23(15–31) | 11 | 96.54 | 26(13–40) | 6 | 98.25 | 55(34–75) | 4 | 92.92 |

| Amoxicillin- Clavulanic acid | 53(32–74) | 7 | 98.76 | 47(8–86) | 4 | 99.48 | 61(13–100) | 4 | 99.59 |

| Erythromycin | 41(16–66) | 6 | 98.91 | 38(6–71) | 5 | 99.43 | 81(68–93) | 3 | |

| Cefuroxime | 64(60–69) | 2 | 17(14–20) | 2 | 60(27–93) | 4 | 98.08 | ||

| Ceftriaxone | 32(18–46) | 8 | 97.73 | 18(10–26) | 5 | 91.71 | 75(58–92) | 4 | 92.19 |

| Tetracycline | 37(10–63) | 4 | 98.85 | 20(6–35) | 3 | 98(88–100) | 1 | ||

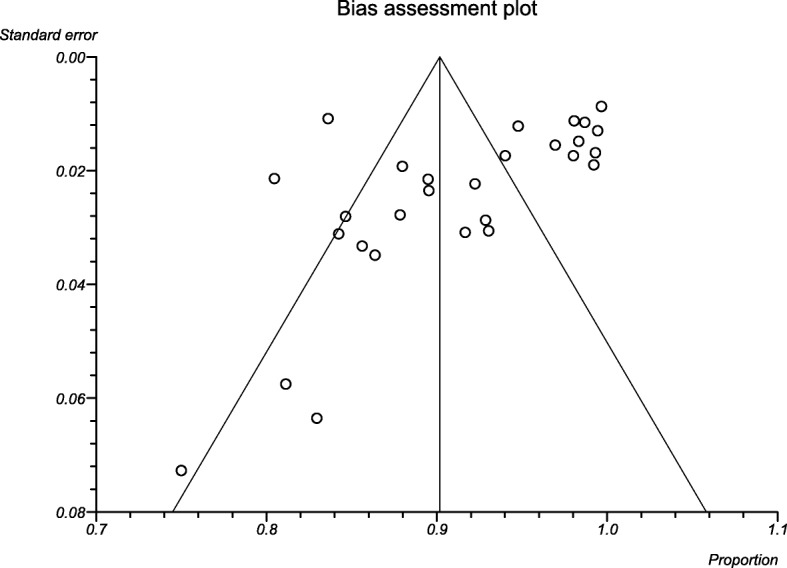

Publication bias

There is some evidence of publication bias in studies reporting the prevalence of bacterial isolates as confirmed by funnel plots of the standard error with proportion supplemented by statistical tests (Begg’s test, p = 0.0016; Egger’s test, p = 0.0211) (Fig. 3). However, there was no significant publication bias in the subgroup analysis.

Fig. 3.

Funnel plot depicting publication bias for Bacterial Otitis Media in sub-Saharan Africa

Discussion

This analysis included 32 original studies addressing bacterial isolation rate from otitis media within the specified time-frame. Since all the included studies have a cross-sectional study design the pooled analysis could be used to assess the relative importance of various pathogens in Africa as well as worldwide. All the included studies in this review have collected an ear swab/discharge sample for microbiological analysis. The bacterial isolation rate using culture-based techniques ranged from 86% (pediatric patients) to 98% (patients with CSOM). Data coverage was featuring predominantly within some countries like Nigeria while most other countries don’t have any study to represent the population.

Bacteria can reach the middle ear in otitis media from nasopharynx through the Eustachian tube or from the external ear canal through the non-intact eardrum. Aerobic bacteria like S. aureus, P. aeruginosa and Proteus species (majorly P. mirabilis) were the main bacterial pathogens for otitis media in this analysis. The finding of those pathogens as a major isolate provides a more definitive confirmation of what has been reported by other published single-country studies as the result consistent [37, 41, 45]. Other bacteria are also indicated from studies like Klebsiella species (6–11%), CoNS (6–12%), and E. coli (5–9%).

The prevalence of other pathogens like H. influenzae, S. pneumoniae and, M. catarrhalis is very minimal, even though those isolates were indicated from another review [60, 61], and commonly reported from AOM and OME episodes, especially during childhood [4, 12, 14]. Since most of the studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa are on CSOM and the collected samples are ear swab/discharge these pathogens are less likely to be reported from the studies. This minimal finding could also be due to regional differences or the absence of studies conducted using molecular techniques that had higher sensitivity compared to culture techniques.

On a recent international consensus on the management of otitis media with effusion panelists generally agreed not to consider antibiotics as a non-surgical management option for OME [62]. Several other reviews have indicated that the management of OM is far better with antibiotics and oto-topical agents than without any treatment, especially if it is CSOM [63, 64]. Considering this review setting and population, treatment with antibiotics is a primary option as most of the studies are conducted on patients with CSOM. On the contrary, isolates from otitis media were having a high level of resistance to commonly used antibacterial agents in this analysis. The highest resistance is against ampicillin (ranging from 69 to 94%) followed by Amoxicillin (62–85%), cotrimoxazole (41–90%), Augmentin (47–61%) and Cefuroxime (17–64%). Generally, the resistance to erythromycin, ceftriaxone, Tetracycline, and ceftazidime was less than 50% for most of the studies. Those drugs are commonly used drugs for the management of otitis media, especially in low-income country settings without appropriate microbiological diagnostic service. This review also found that relatively higher susceptibility of isolates to ciprofloxacin, gentamycin, and chloramphenicol, less than 35% resistance. The studies included in this review revealed that non-susceptibility to fluoroquinolones ranged between 16 and 34%.

All studies in this review span on the analysis of ear swab/ discharge, which is a late-onset scenario. Early diagnosis and management of otitis media have a paramount effect on the health of the patients, especially children, as it has complications ranging from tympanic membrane perforation to neurological impairments. Early-onset infections will require the collection of middle ear fluid by tympanocentesis, which will be hard to practice in sub-Saharan Africa, without advanced medical facilities. A clear contribution of pathogens, like fastidious and anaerobic bacteria, can be understood by using highly sensitive laboratory techniques.

It is unlikely that this review has missed a relevant study as we have conducted a highly sensitive systematic search, including grey literature. The dearth of appropriate population-based elegant studies, risk of bias in prevalence studies, mainly due to under-reporting; and heterogeneity of data were the main limitations of this review. Etiological data were more consistent with some discrepancies in isolation rates, which can be explained by the quality of the microbiological procedures used, such as sample collection and transportation and bacterial isolation in some studies. One of the recognized limitations in such pooled studies [65] is differences in middle ear fluid collection guidelines in different localities even with efforts to standardize the design across studies. There are likely differences in care-seeking practices for OM among countries, affecting the severity of cases, and one country may collect middle ear fluid only in cases considered to be recurrent OM. The true contribution of these bacteria to OM is likely higher than the reported as bacterial etiology was not determined by molecular techniques in the included studies [66]. Different clinical severity or age tropisms may have been observed from culture-negative samples with molecular testing.

Following accepted methods, all-inclusive searching with date range, put together with a quality appraisal of the included studies are the main strength of this review. Stakeholders who focus on such matters will get a great benefit from compiling all available evidence to make informed decisions on prevention measures.

Conclusions

The analysis revealed that P. aeruginosa, S. aureus and P. mirabilis are the commonest bacterial pathogens responsible for otitis media in sub-Saharan Africa. A high level of resistance was observed to commonly used antibacterial agents such as Ampicillin, cotrimoxazole, Amoxicillin, and Amoxicillin-clavulanate however, isolates were less resistant to Ciprofloxacin, Gentamycin, and Chloramphenicol.

Thus, drugs like Ampicillin, amoxicillin, Amoxicillin-clavulanate, and cotrimoxazole should not be used as a first-line treatment in sub-Saharan countries since countries in this geographical location are commonly dependent on clinical data for treatment with the absence of microbiology laboratory. Without proper treatment, otitis media could lead to intracranial and intratemporal complications with higher and complex management.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1:Data extraction and summary sheet. Sheet 1 (character): participant information and culture positive rate of Otitis media. Sheet 2 (isolates): Bacterial isolates from Otitis media. Sheet 3 (susceptibility): Drug susceptibility test of isolates.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express the heartfelt gratitude to staff members of Medical Laboratory Sciences as well as college of Health and Medical Sciences for providing genuine technical support.

Abbreviations

- AOM

Acute Otitis Media

- CoNS

Coagulase Negative Staphylococci

- CSOM

Chronic Suppurative Otitis Media

- OM

Otitis Media

- OME

Otitis Media with Effusion

- URTI

Upper Respiratory Tract Infections

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

TT and HM conceived and designed the study. MS, FW, ZA, BM, DM & ZT had participated in collecting scientific literature, critical appraisal of articles for inclusion, analysis, and interpretation of the findings. TT and HM drafted the manuscript. TT also prepared the manuscript for publication. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article as supplementary information files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Tewodros Tesfa, Email: tewodrost1@gmail.com.

Habtamu Mitiku, Email: habtemit@gmail.com.

Mekonnen Sisay, Email: mekonnensisay27@yahoo.com.

Fitsum Weldegebreal, Email: fwmlab2000@gmail.com.

Zerihun Ataro, Email: zerihunataro@yahoo.com.

Birhanu Motbaynor, Email: dovehod@gmail.com.

Dadi Marami, Email: dmarami4@gmail.com.

Zelalem Teklemariam, Email: zel1999@gmail.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12879-020-4950-y.

References

- 1.Bluestone CD, Klein JO. Otitis media in infants and children: PMPH-USA. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morris PS, Leach AJ. Acute and chronic otitis media. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2009;56(6):1383–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jawetz E, Melnick JL, Adelberg EA. Jawetz, Melnick & Adelberg's medical microbiology: Appleton & Lange. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rovers MM, Schilder AG, Zielhuis GA, Rosenfeld RM. Otitis media. Lancet. 2004;363(9407):465–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15495-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Acuin J, Organization WH . Chronic suppurative otitis media: burden of illness and management options. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vos T, Barber RM, Bell B, Bertozzi-Villa A, Biryukov S, Bolliger I, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386(9995):743–800. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monasta L, Ronfani L, Marchetti F, Montico M, Vecchi Brumatti L, Bavcar A, et al. Burden of disease caused by otitis media: systematic review and global estimates. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e36226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mulwafu W., Kuper H., Ensink R. J. H. Prevalence and causes of hearing impairment in Africa. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2015;21(2):158–165. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor S, Marchisio P, Vergison A, Harriague J, Hausdorff WP, Haggard M. Impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination on otitis media: a systematic review. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(12):1765–1773. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abera B, Kibret M. Bacteriology and antimicrobial susceptibility of otitis media at dessie regional health research laboratory, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2011;25(2):161–7.

- 11.Arguedas A, Sher L, Lopez E, Saez-Llorens X, Hamed K, Skuba K, et al. Open label, multicenter study of gatifloxacin treatment of recurrent otitis media and acute otitis media treatment failure. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22(11):949–956. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000095193.42502.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gisselsson-Solén M, Henriksson G, Hermansson A, Melhus Å. Risk factors for carriage of AOM pathogens during the first 3 years of life in children with early onset of acute otitis media. Acta Otolaryngol. 2014;134(7):684–690. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2014.890291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leibovitz E, Jacobs MR, Dagan R. Haemophilus influenzae: a significant pathogen in acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23(12):1142–1152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Massa HM, Cripps AW, Lehmann D. Otitis media: viruses, bacteria, biofilms and vaccines. Med J Aust. 2009;191(9 Suppl):S44–S49. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02926.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Revai K, Mamidi D, Chonmaitree T. Association of nasopharyngeal bacterial colonization during upper respiratory tract infection and the development of acute otitis media. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(4):e34–e37. doi: 10.1086/525856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruohola A, Meurman O, Nikkari S, Skottman T, Salmi A, Waris M, et al. Microbiology of acute otitis media in children with tympanostomy tubes: prevalences of bacteria and viruses. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(11):1417–1422. doi: 10.1086/509332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D. Prisma 2009 checklist. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munn Zachary, Moola Sandeep, Lisy Karolina, Riitano Dagmara, Tufanaru Catalin. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare. 2015;13(3):147–153. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101. doi: 10.2307/2533446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ofogbu CV, Orji FT, Ezeanolue BC, Emodi I. Microbiological profile of chronic suppurative otits media among HIV infected children in south eastern Nigeria. Nigerian J Med. 2016;25(1):5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tandon A, Singh B, Sharma P, Shukla D, Saraswat N. Juvenile central serous retinopathy an atypical presentation of ASOM (acute Suppurative otitis media)-a case report. Int J Contemp Med. 2014;2(2):202–204. doi: 10.5958/2321-1032.2014.01060.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akingbade O, Awoderu O, Okerentugba P, Nwanze J, Onoh C, Okonko I. Bacterial spectrum and their antibiotic sensitivity pattern in children with otitis media in Abeokuta, Ogun state, Nigeria. World Rural Obs. 2013;5:1. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nwokoye N, Egwari L, Olubi OO. Occurrence of otitis media in children and assessment of treatment options. J Laryngol Otol. 2015;129(8):779–783. doi: 10.1017/S0022215115001127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogbogu PI, Eghafona NO, Ogbogu MI. Microbiology of otitis media among children attending a tertiary hospital in Benin City, Nigeria. J Public Health Epidemiol. 2013;5(7):280–284. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Afolabi OA, Salaudeen AG, Ologe FE, Nwabuisi C, Nwawolo CC. Pattern of bacterial isolates in the middle ear discharge of patients with chronic suppurative otitis media in a tertiary hospital in north Central Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2012;12(3):362–367. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v12i3.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Appiah-Korang L, Asare-Gyasi S, Yawson AE, Searyoh K. Aetiological agents of ear discharge: a two year review in a teaching hospital in Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2014;48(2):91–95. doi: 10.4314/gmj.v48i2.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Argaw-Denboba A, Abejew AA, Mekonnen AG. Antibiotic-resistant Bacteria are major threats of otitis Media in Wollo Area, Northeastern Ethiopia: A Ten-Year Retrospective Analysis. Int J Microbiol. 2016;2016:8724671. doi: 10.1155/2016/8724671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chidozie AH, Uchegbu U, Johnkennedy N, GC U, Catherine A. Effects of gender and seasonal variation on the prevalence of otitis media among young children in Owerri, Imo State Nigeria. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chirwa M, Mulwafu W, Aswani JM, Masinde PW, Mkakosya R, Soko D. Microbiology of chronic suppurative otitis media at queen Elizabeth central hospital, Blantyre, Malawi: a cross-sectional descriptive study. Malawi Med J. 2015;27(4):120–124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ejiofor SO, Edeh AD, Ezeudu CE, Gugu TH, Oli AN. Multi-drug resistant acute otitis media amongst children attending out-patient Clinic in Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University Teaching Hospital, Awka, South-East Nigeria. Adv Microbiol. 2016;6(07):495. doi: 10.4236/aim.2016.67049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elmustafa M, Yousif M, Osman W, Elmustafa O. Aerobic bacteria in safe type chronic suppurative otitis media in Gezira state, Sudan. J Sci Technol (Ghana) 2016;36(1):1–6. doi: 10.4314/just.v36i1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fayemiwo S, Ayoade R, Adesiji Y, Taiwo S. Pattern of bacterial pathogens of acute otitis media in a tertiary hospital, South Western Nigeria. Afr J Clin Exp Microbiol. 2017;18(1):29–34. doi: 10.4314/ajcem.v18i1.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garba BI, Mohammed BA, Mohammed F, Rabiu M, Sani UM, Isezuo KO, et al. Antibiotic susceptibility pattern of bacterial isolates in children with otitis media in Zamfara, North-Western Nigeria. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2017;11(43):1558–1563. doi: 10.5897/AJMR2017.8712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Habibu A. Bacteriology of otitis media among patients attending general hospital Bichi, Nigeria. Int J Eng Sci. 2015;4(8):33–37. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hailu D, Mekonnen D, Derbie A, Mulu W, Abera B. Pathogenic bacteria profile and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of ear infection at Bahir Dar regional Health Research Laboratory center, Ethiopia. SpringerPlus. 2016;5(1):466. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2123-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jido B, et al. Isolation and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cases of otitis media among patients attending Ahmadu Bello University teaching hospital, Zaria. Niger Eur J Biotechnol Biosci. 2014;2(2):18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jik A, Ogundeji E, Maxwell I, Ogundeji A, Samaila J, Sunday C, et al. Identification of microorganism associated with otitis media among children in Ganawuri area of plateau state, Nigeria. IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2015;14(12):61–67. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Justin R, Tumweheire G, Kajumbula H, Ndoleriire C. Chronic suppurative otitis media: bacteriology, susceptibility and clinical presentation among ENT patients at Mulago hospital, Uganda. South Sudan Med J. 2018;11(2):31–35. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kazeem MJ, Aiyeleso R. Current bacteriological profile of chronic suppurative otitis media in a tertiary facility of northern Nigeria. Indian J Otol. 2016;22(3):157. doi: 10.4103/0971-7749.187979. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matundwelo N, Mwansasu C. Bacteriology of chronic Suppurative otitis media among children at the Arthur Davidson Children's hospital, Ndola, Zambia. Med J Zambia. 2016;43(1):36–40. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muluye D, Wondimeneh Y, Ferede G, Moges F, Nega T. Bacterial isolates and drug susceptibility patterns of ear discharge from patients with ear infection at Gondar University Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Ear, Nose Throat Disord. 2013;13(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6815-13-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nwogwugwu N, Dozie I, Chinakwe E, Nwachukwu I, Onyemekara N. The bacteriology of discharging ear (otitis media) amongst children in Owerri, Imo state, south East Nigeria. British Microbiol Res J. 2014;4(7):813–820. doi: 10.9734/BMRJ/2014/5304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ogah S, Ogah J. Aerobic bacteriology of chronic Suppurative otitis media (CSOM) in Federal Medical Centre Lokoja, Nigeria. Nig J Pure Appl Sci. 2016;29:2695–99.

- 46.Ohieku J, Fakuade F. Otitis media: clinical assessment of etiological pathogens, susceptibility status and available therapeutic options among 19 antibacterial agents in Maiduguri-City, Nigeria. World J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2013;2(4):1548–1156. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Onifade AK, Afolayan CO, Afolami OI. Antimicrobial sensitivity, extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) production and plasmid profile by microorganisms from otitis media patients in Owo and Akure, Ondo state, Nigeria. Karbala Int J Modern Sci. 2018;4(3):332–340. doi: 10.1016/j.kijoms.2018.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Orji FT, Dike BO. Observations on the current bacteriological profile of chronic suppurative otitis media in south eastern Nigeria. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2015;5(2):124–128. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.153622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ouedraogo RW, Gyebre YM, Sereme M, Ouedraogo BP, Elola A, Bambara C, et al. Bacteriological profile of chronic otitis media in the ENT and neck surgery department at the Ouagadougou University Hospital Center (Burkina Faso) Med Sante Trop. 2012;22(1):109–110. doi: 10.1684/mst.2012.0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Phiri H, John A, Mary O, Uta F, John M. Microbiological isolates of chronic Suppurative otitis Media at the University Teaching Hospital and Beit Cure Hospital in Lusaka, Zambia. Int J Clin Exp Med Sci. 2016;2(5):94. doi: 10.11648/j.ijcems.20160205.14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seid A, Deribe F, Ali K, Kibru G. Bacterial otitis media in all age group of patients seen at Dessie referral hospital, north East Ethiopia. Egypt J Ear, Nose, Throat Allied Sci. 2013;14(2):73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ejenta.2013.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tiedt NJ, Butler IR, Hallbauer UM, Atkins MD, Elliott E, Pieters M, et al. Paediatric chronic suppurative otitis media in the Free State Province: clinical and audiological features. S Afr Med J. 2013;103(7):467–470. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.6636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Udden F, Filipe M, Reimer A, Paul M, Matuschek E, Thegerstrom J, et al. Aerobic bacteria associated with chronic suppurative otitis media in Angola. Infect Dis Poverty. 2018;7(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s40249-018-0422-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wasihun AG, Zemene Y. Bacterial profile and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of otitis media in Ayder teaching and referral hospital, Mekelle University, Northern Ethiopia. Springerplus. 2015;4(1):701. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1471-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Worku S, Gelaw A, Aberra Y, Muluye D, Derbie A, Biadglegne F. Bacterial etiologies, antibiotic susceptibility patterns and risk factors among patients with ear discharge at the University of Gondar Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2017;7(1):36–42. doi: 10.12980/apjtd.7.2017D6-242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Adoga AA, Bakari A, Afolabi OA, Kodiya AM, Ahmad BM. Bacterial isolates in chronic suppurative otitis media: a changing pattern? Nig J Med. 2011;20(1):96–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hailegiyorgis TT, Sarhie WD, Workie HM. Isolation and antimicrobial drug susceptibility pattern of bacterial pathogens from pediatric patients with otitis media in selected health institutions, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a prospective cross-sectional study. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 2018;18(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s12901-018-0056-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mushi MF, Mwalutende AE, Gilyoma JM, Chalya PL, Seni J, Mirambo MM, et al. Predictors of disease complications and treatment outcome among patients with chronic suppurative otitis media attending a tertiary hospital, Mwanza Tanzania. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 2016;16:1. doi: 10.1186/s12901-015-0021-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Worku M, Bekele M. Bacterial isolate and antibacterial resistance pattern of ear infection among patients attending at Hawassa university referral hospital, Hawassa, Ethiopia. Indian J Otol. 2014;20(4):155. doi: 10.4103/0971-7749.146929. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mahadevan M, Navarro-Locsin G, Tan HKK, Yamanaka N, Sonsuwan N, Wang P-C, et al. A review of the burden of disease due to otitis media in the Asia-Pacific. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;76(5):623–635. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2012.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ngo CC, et al. Predominant bacteria detected from the middle ear fluid of children experiencing otitis media: a systematic review. 2016;11(3):1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Simon F, Haggard M, Rosenfeld RM, Jia H, Peer S, Calmels MN, et al. International consensus (ICON) on management of otitis media with effusion in children. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2018;135(1S):S33–SS9. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2017.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Abes G, Espallardo N, Tong M, Subramaniam KN, Hermani B, Lasiminigrum L, et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness of ofloxaxin otic solution for the treatment of suppurative otitis media. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2003;65(2):106–116. doi: 10.1159/000070775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Acuin J, Smith A, Mackenzie I. Interventions for chronic suppurative otitis media. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;2(2):CD000473. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Blettner M. Traditional reviews, meta-analyses and pooled analyses in epidemiology. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1999;28(1):1–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pumarola F, Mares J, Losada I, Minguella I, Moraga F, Tarrago D, et al. Microbiology of bacteria causing recurrent acute otitis media (AOM) and AOM treatment failure in young children in Spain: shifting pathogens in the post-pneumococcal conjugate vaccination era. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;77(8):1231–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1:Data extraction and summary sheet. Sheet 1 (character): participant information and culture positive rate of Otitis media. Sheet 2 (isolates): Bacterial isolates from Otitis media. Sheet 3 (susceptibility): Drug susceptibility test of isolates.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article as supplementary information files.