Abstract

Background

Leptospirosis is a widespread zoonosis and has been recognized as a re-emerging infectious disease in humans and dogs, but prevalence of Leptospira shedding in dogs in Thailand is unknown. The aim of this study was to determine urinary shedding of Leptospira in dogs in Thailand, to evaluate antibody prevalence by microscopic agglutination test (MAT) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and to assess risk factors for Leptospira infection.

In Northern, Northeastern, and Central Thailand, 273 stray (n = 119) or client-owned (n = 154) dogs from rural (n = 139) or urban (n = 134) areas were randomly included. Dogs that had received antibiotics within 4 weeks prior to sampling were excluded. No dog had received vaccination against Leptospira. Urine was evaluated by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) specific for lipL32 gene of pathogenic Leptospira. Additionally, urine was cultured for 6 months in Ellinghausen-McCullough-Johnson-Harris (EMJH) medium. Antibodies were measured by ELISA and MAT against 24 serovars belonging to 15 serogroups and 1 undesignated serogroup. Risk factor analysis was performed with backwards stepwise selection based on Wald.

Results

Twelve of 273 (4.4%; 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.0–6.8%) urine samples were PCR-positive. In 1/273 dogs (0.4%; 95% CI: 0.01–1.1%) Leptospira could be cultured from urine. MAT detected antibodies in 33/273 dogs (12.1%; 95% CI: 8.2–16.0%) against 19 different serovars (Anhoa, Australis, Ballum, Bataviae, Bratislava, Broomi, Canicola, Copenhageni, Coxi, Grippotyphosa, Haemolytica, Icterohaemorrhagiae, Khorat, Paidjan, Patoc, Pyrogenes, Rachmati, Saxkoebing, Sejroe). In 111/252 dogs (44.0%; 95% CI: 37.9–50.2%) immunoglobulin M (IgM) and/or immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies were found by ELISA. Female dogs had a significantly higher risk for Leptospira infection (p = 0.023).

Conclusions

Leptospira shedding occurs in randomly sampled dogs in Thailand, with infection rates comparable to those of Europe and the USA. Therefore, the potential zoonotic risk should not be underestimated and use of Leptospira vaccines are recommended.

Keywords: Canine, Culture, Dogs, ELISA, Leptospira, MAT, PCR, Risk factors, Seroprevalence, Zoonosis

Background

Leptospirosis is categorized as a neglected zoonotic disease, affecting both humans and animals [1]. The disease is caused by spiral-shaped, gram-negative spirochetes of the genus Leptospira. To date, there are more than 260 different Leptospira serovars worldwide. Almost all mammalian species and marsupials can become renal carriers, and human infections originate from animal carriers [2]. The importance of the infection for public health and veterinary medicine is significant, and the impact of animal leptospirosis probably exceeds that in human [3]. In Thailand, human leptospirosis is classified as an emerging infectious disease with an outbreak peak of 14,285 cases in the year 2000 [4]. Recent data from Thailand even demonstrate a nationwide increase in 2017 compared to 2015–2016. In total, 3156 leptospirosis cases and 57 fatalities were registered in 2017, with a morbidity rate of 4.8 and a mortality rate of 0.09 per 100,000 population. Most cases were reported from Northeastern Thailand [5]. Moreover, an alarmingly high antibody prevalence of 89.1% (205/230) was documented in stray dogs from Bangkok [6] (Table 1), and the constantly increasing number of stray dogs has become a public health issue in Thailand [11]. Dogs, especially strays, are considered an important reservoir of Leptospira, and thus play a major role in human infections [12–16]. In addition, “dog ownership” was identified as a potential risk factor for humans [17–22]. Worldwide studies showed a prevalence of urinary shedding of Leptospira in dogs between 0.2 and 31.1% by PCR [23–37]. Shedding can also occur in healthy dogs [23, 25, 31–33, 35, 37]. Thus, dogs recently gained interest as potential source of human infection.

Table 1.

Prevalence of microscopic agglutination test (MAT) antibodies of dogs tested at various regions in Thailand

| Region of Thailand | Number of dogs sampled | MAT cut-off | Antibody prevalence | Most common seroreactivity | Study reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chaiyaphum province, Northeastern Thailand | 47 | ≥1:100 | 4.3% (2/47) | Autumnalis | [7] |

| Mahasarakham province, Northeastern Thailand | 55 | ≥1:100 | 10.9% (6/55) | Canicola | [8] |

| Chiang Mai, Northern Thailand | 210 | ≥1:20 | 11.0% (23/210) | Bataviae, Canicola, Bratislava, Icterohaemorrhagiae, Ballum, Djasiman, Javanica, Mini, Sejroe | [9] |

| Nakhon Pathom province, Central Thailand | 153 | ≥1:50 | 57.5% (88/153) | Tarassovi, Ranarum, Saigon, Bratislava, Copenhageni, Patoc, Bangkok, Sejroe, Autumnalis, Sarmin, Canicola | [10] |

| Bangkok, Central Thailand | 230 | ≥1:100 | 89.1% (205/230) | Bataviae, Patoc, Tarassovi, Sejroe, Shermani, Autumnalis, Ranarum, Sarmin, Grippotyphosa, Hebdomadis, Manhao, Pomona, Louisiana, Bratislava, Cynopteri | [6] |

There are no comprehensive studies on Leptospira urinary shedding in dogs in Thailand, although several studies demonstrated presence of antibodies against Leptospira in 4.3 to 89.1% of dogs [6–10] (Table 1). Moreover, a recently published small study from Thailand detected Leptospira in the urine of 10.3% (6/58) asymptomatic dogs by rrs nested PCR [32]. Therefore, the aims of the present study were to determine Leptospira urinary shedding prevalence by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), to culture Leptospira from urine, to evaluate Leptospira antibody prevalence by microscopic agglutination test (MAT) and by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) differentiating immunoglobulin M (IgM) and immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies, and to assess risk factors associated with Leptospira infection in dogs in Thailand.

Results

Prevalence of Leptospira urinary shedding

In 12/273 dogs, DNA from pathogenic Leptospira was amplified from urine; thus, prevalence of urinary Leptospira DNA shedding was 4.4% (95% CI: 2.0–6.8%). Five of 12 PCR-positive dogs (41.7%) were client-owned and 7/12 (58.3%) were stray. Eight shedders were of rural origin (66.7%); 4/12 (33.3%) came from urban areas (Table 2). MAT was positive in 4/12 (33.3%) PCR-positive dogs; 9/12 (75.0%) PCR-positive dogs had detectable antibodies in IgM/IgG ELISA.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the 12 dogs shedding Leptospira determined by real-time PCR in urine

| Signalment | Status | Origin | Reason for presentation | Physical examination | Urine PCR Ct value | Urine culture | MAT (cut-off: ≥1:20) | IgM/IgG ELISA (cut-off: ≥1:320) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 y, mix, f, i | client-owned | Amnat Charoen, rural | neutering | unremarkable | 28.3 | neg |

1:640 Sejroe 1:320 Saxkoebing 1:20 Haemolytica |

IgM 1:1280 IgG 1:640 |

| 1 y, mix, f, i | client-owned | Amnat Charoen, rural | neutering | unremarkable | 38.0 | neg | neg | neg |

| 2 y, mix, f, i | client-owned | Lamphun, rural | neutering | enlarged Lnn. mandibulares | 36.8 | neg |

1:80 Sejroe 1:40 Saxkoebing |

IgM neg IgG 1:640 |

| ~ 3 y, mix, m, i | stray |

Pathum Thani, rural |

neutering | unremarkable | 33.1 | neg | neg | neg |

| ~ 2 y, mix, f, i | stray |

Pathum Thani, rural |

neutering | mildly increased inspiratory lung sounds | 34.5 | neg | neg |

IgM 1:320 IgG neg |

| ~ 6 m, mix, f, i | stray |

Pathum Thani, rural |

neutering | unremarkable | 29.0 | pos | neg |

IgM 1:320 IgG neg |

| ~ 2 y, mix, f, i | stray | Samut Songkhram, rural | neutering | unremarkable | 32.9 | neg | neg |

IgM 1:320 IgG neg |

| ~ 3 y, mix, f, i | stray | Samut Songkhram, rural | neutering | mildly increased inspiratory lung sounds, enlarged Lnn. mandibulares | 31.4 | neg | neg | IgM 1:640 IgG neg |

| 1 y, mix, f, i | client-owned | Nakohn Ratchasima, urban | neutering | unremarkable | 30.0 | neg | neg | IgM 1:320 IgG neg |

| 3 y, poodle, m, i | client-owned | Nakhon Ratchasima, urban | neutering | enlarged Lnn. mandibulares | 36.7 | neg | 1:40 Icterohaemorrhagiae |

IgM neg IgG 1:2560 |

| ~ 3 y, mix, m, i | stray | Bangkok, urban | neutering | unremarkable | 28.3 | neg | 1:640 Bataviae 1:80 Paidjan | IgM 1:2560 IgG 1:640 |

| ~ 4 y, mix, f, i | stray | Bangkok, urban | neutering | unremarkable | >40.0 | neg | neg | neg |

y years, m months, mix mixed breed, f female, m male, i intact, Lnn. lymph nodes, PCR polymerase chain reaction, Ct value threshold cycle, neg negative, pos positive, MAT microscopic agglutination test, ELISA enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, IgM immunoglobulin M, IgG immunoglobulin G

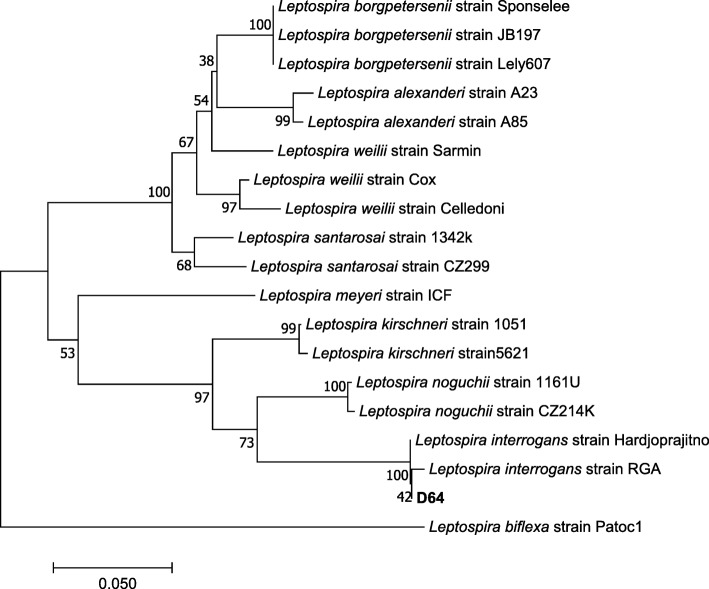

Urine of all 273 dogs was cultured for 6 months. In only 1 urine culture (0.4%; 95% CI: 0.01–1.1%), Leptospira were growing after an incubation period of 3 months. All other 272 cultures remained negative after 6 months. The dog with the positive culture was also positive in urine PCR (Table 2). In ELISA, this dog had IgM antibodies of 1:320, but no IgG antibodies. No antibodies were found by MAT. Phylogenetic analysis based on secY sequencing showed that this Leptospira strain belonged to the pathogenic genospecies Leptospira interrogans (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Evolutionary relationships of taxa. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method. The optimal tree with the sum of branch length = 0.76583659 is shown. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) are shown next to the branches. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. The analysis involved 19 nucleotide sequences. Codon positions included were 1st + 2nd + 3rd + noncoding. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 245 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA 7. The bar indicates 0.050 estimated substitution per sequence position. Dog D64 of the present study clusters within the genomospecies Leptospira interrogans

Antibody prevalence

Anti-leptospiral antibodies were detected in MAT in 33/273 dogs (12.1%; 95% CI: 8.2–16.0%). Antibodies to more than 1 serovar were found in 15/33 MAT-positive dogs (45.5%). Antibodies were detected against 19 serovars belonging to 12 serogroups. The most common serogroup was Sejroe (4.4%), followed by Icterohaemorrhagiae (3.7%), Bataviae (2.9%), and Canicola (2.6%). MAT titers ranged from 1:20 to 1:640 (Table 3). A very high MAT titer of 1:640 was only found in 2 dogs against serogroup Bataviae (serovar Bataviae) and Sejroe (serovar Sejroe). These dogs also had high IgM and IgG antibodies in ELISA. The dog with high antibodies against serogroup Sejroe had IgM titer of 1:1280 and IgG titer of 1:640. The dog with MAT titer of 1:640 against serogroup Bataviae had IgM titer of 1:2560 and IgG titer of 1:640. Both dogs were urine PCR-positive (Table 2) but not positive in urine culture.

Table 3.

Number and percentage of microscopic agglutination test- (MAT-) positive results among 273 dogsa

| Serogroup | Serovar | Number of dogs with respective MAT titers | Total number of dogs with MAT titers ≥1:20 | Percentage of dogs with MAT titers ≥1:20 (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1:20 | 1:40 | 1:80 | 1:160 | 1:320 | 1:640 | ||||

| Australis | Australis | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.7 (0.0–1.7) |

| Bratislava | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1.1 (0.0–2.3) | |

| Autumnalis | Autumnalis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Rachmati | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.7 (0.0–1.7) | |

| Ballum | Ballum | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1.5 (0.0–2.9) |

| Bataviae | Bataviae | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 1.8 (0.2–3.4) |

| Paidjan | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1.1 (0.0–2.3) | |

| Canicola | Broomi | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1.5 (0.0–2.9) |

| Canicola | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1.1 (0.0–2.3) | |

| Celledoni | Anhoa | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.4 (0.0–1.1) |

| Celledoni | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Cynopteri | Cynopteri | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Djasiman | Djasiman | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Grippotyphosa | Grippotyphosa | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1.1 (0.0–2.3) |

| Icterohaemorrhagiae | Copenhageni | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1.5 (0.0–2.9) |

| Icterohaemorrhagiae | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 2.2 (0.5–3.9) | |

| Javanica | Coxi | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.4 (0.0–1.1) |

| Pomona | Pomona | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Pyrogenes | Pyrogenes | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1.8 (0.2–3.4) |

| Sejroe | Haemolytica | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.7 (0.0–1.7) |

| Saxkoebing | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 2.6 (0.7–4.4) | |

| Sejroe | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1.1 (0.0–2.3) | |

| Semaranga | Patoc | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.7 (0.0–1.7) |

| Undesignated | Khorat | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.7 (0.0–1.7) |

| Total | 27 | 18 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 62 | 22.7 (17.7–27.7) | |

aAntibodies against more than one serovar were detected in 15/33 MAT-positive dogs

CI confidence interval

IgM and IgG ELISA was performed in 252/273 dogs. In 17/273 dogs, only IgM ELISA was performed and in 4/273 dogs, neither IgM nor IgG ELISA was performed due to limited amount of serum. In 111/252 dogs (44.0%; 95% CI: 37.9–50.2%), either IgM and/or IgG antibodies were detectable. Comparing results of ELISA to MAT, 100/252 dogs (39.7%; 95% CI: 33.6–45.7%) showed discrepant results. Of 141 ELISA-negative dogs, 9 dogs were positive in MAT. Presence of both IgM and IgG antibodies (≥1:320) was found in 41 dogs of which only 14/41 were also MAT-positive (≥1:20), resulting in a discrepancy of 65.9%. Of 111 ELISA-positive dogs, 86 dogs (77.5%) were completely negative in all other diagnostic assays (PCR, urine culture, MAT).

Risk factor analysis

Risk factors associated with Leptospira infection in dogs are illustrated in Table 4. In univariate analysis, female dogs (odds ratio [OR] 1.910; 95% confidence interval [95% CI] 1.138–3.204; p = 0.014) and dogs with no cattle contact (OR 4.697; 95% CI 1.382–15.969; p = 0.013) were significantly more commonly infected with Leptospira than male dogs and dogs with cattle contact. Only the category “female sex” (OR 1.890; 95% CI 1.092–3.270; p = 0.023) proved to be significantly associated with Leptospira-infected dogs after backwards stepwise selection based on Wald. None of the investigated parameters was significantly associated with presence of antibodies against Leptospira determined by MAT (see Additional file 1: Table S1), or with urinary shedding of Leptospira detected by PCR (see Additional file 2: Table S2).

Table 4.

Risk factor analysis for dogs being Leptospira-infected (PCR- and/or ELISA- and/or MAT-positive)

| Variable | Total dogs | Categories | Number of dogs tested | Leptospira-positive | Leptospira-negative | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis (n = 242) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (%) | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p | ||||

| Age | 242 | <1 year | 36 | 18 (50.0) | 18 (50.0) | 1.000 | 0.428–2.339 | 1.000 | a | a | a |

| 1.0–1.9 years | 64 | 35 (54.7) | 29 (45.3) | 1.207 | 0.580–2.513 | 0.709 | |||||

| 2.0–2.9 years | 45 | 22 (48.9) | 23 (51.1) | 0.957 | 0.431–2.125 | 1.000 | |||||

| 3.0–3.9 years | 52 | 26 (50.0) | 26 (50.0) | Reference | |||||||

| 4.0–5.9 years | 28 | 13 (46.4) | 15 (53.6) | 0.867 | 0.345–2.176 | 0.817 | |||||

| ≥6 years | 17 | 8 (47.1) | 9 (52.9) | 0.889 | 0.297–2.661 | 1.000 | |||||

| Breed | 273 | mix | 266 | 132 (49.6) | 134 (50.4) | 1.313 | 0.288–5.982 | 0.725 | a | a | a |

| pure breed | 7 | 3 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) | ||||||||

| Sex | 273 | female | 185 | 101 (54.6) | 84 (45.4) | 1.910 | 1.138–3.204 | 0.014 | 1.890 | 1.092–3.270 | 0.023 |

| male | 88 | 34 (38.6) | 54 (61.4) | ||||||||

| Neutering status | 273 | intact | 270 | 134 (49.6) | 136 (50.4) | 1.971 | 0.177–21.992 | 1.000 | a | a | a |

| neutered | 3 | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | ||||||||

| Weight | 175 | 5–11 kg | 48 | 23 (47.9) | 25 (52.1) | 0.595 | 0.291–1.218 | 0.202 | |||

| 12–17 kg | 84 | 51 (60.7) | 33 (39.3) | Reference | |||||||

| ≥18 kg | 43 | 28 (65.1) | 15 (34.9) | 1.208 | 0.562–2.595 | 0.701 | |||||

| Origin | 273 | client-owned | 154 | 74 (48.1) | 80 (51.9) | ||||||

| stray | 119 | 61 (51.2) | 58 (48.8) | 1.137 | 0.705–1.835 | 0.627 | a | a | a | ||

| Environment | 273 | urban | 134 | 73 (54.5) | 61 (45.5) | 1.486 | 0.923–2.395 | 0.103 | a | a | a |

| rural | 139 | 62 (45.6) | 77 (54.4) | ||||||||

| Free-running/roaming allowed | 180 | yes | 174 | 90 (51.7) | 84 (48.3) | ||||||

| no | 6 | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) | 4.667 | 0.534–40.773 | 0.164 | |||||

| Staying outdoors >50% | 168 | yes | 148 | 79 (53.3) | 69 (46.7) | ||||||

| no | 20 | 11 (55.0) | 9 (45.0) | 1.068 | 0.418–2.728 | 1.000 | |||||

| Bathing in water | 32 | yes | 13 | 8 (61.5) | 5 (38.5) | ||||||

| no | 19 | 12 (63.3) | 7 (36.7) | 1.0714 | 0.250–4.591 | 1.000 | |||||

| Drinking out of puddles | 34 | yes | 13 | 8 (61.5) | 5 (38.5) | ||||||

| no | 21 | 13 (61.9) | 8 (38.1) | 1.016 | 0.245–4.213 | 1.000 | |||||

| Contact with rodents | 33 | yes | 22 | 14 (63.6) | 8 (36.4) | 1.000 | 0.222–4.502 | 1.000 | |||

| no | 11 | 7 (63.6) | 4 (36.4) | ||||||||

| Eating rodents | 33 | yes | 6 | 6 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 10.484 | 0.537–204.643 | 0.065 | |||

| no | 27 | 15 (55.5) | 12 (44.5) | ||||||||

| Consumption of raw meat | 40 | yes | 12 | 7 (58.3) | 5 (41.7) | ||||||

| no | 28 | 17 (60.7) | 11 (39.3) | 1.104 | 0.279–4.369 | 1.000 | |||||

| Hunting dog | 273 | yes | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||||||

| no | 273 | 135 (49.5) | 138 (50.5) | 1.0221 | 0.020–51.886 | 1.000 | |||||

| Contact with cats | 50 | yes | 24 | 15 (62.5) | 9 (37.5) | 1.667 | 0.539–5.153 | 0.375 | |||

| no | 26 | 13 (50.0) | 13 (50.0) | ||||||||

| Contact with other dogs | 176 | yes | 175 | 90 (51.4) | 85 (48.6) | ||||||

| no | 1 | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2.834 | 0.114–70.532 | 1.000 | |||||

| Contact with cattle | 58 | yes | 16 | 6 (37.5) | 10 (62.5) | ||||||

| no | 42 | 31 (73.8) | 11 (26.2) | 4.697 | 1.382–15.969 | 0.013 | |||||

| Contact with pigs | 58 | yes | 1 | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.767 | 0.069–45.335 | 1.000 | |||

| no | 57 | 36 (63.2) | 21 (36.8) | ||||||||

Univariate and multivariate analysis for risk factors associated with positivity in at least one diagnostic Leptospira test (n = 135/273): urine PCR, MAT (cut-off: ≥1:20), IgM ELISA, and IgG ELISA (cut-off: ≥1:320). For multivariate analysis, backward stepwise selection based on Wald was performed for the following parameters: age, breed, sex, neutering status, origin, and environment

aVariable was eliminated in backward stepwise selection

Significant p-values are shown in bold

PCR polymerase chain reaction, ELISA enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, MAT microscopic agglutination test, CI confidence interval, p p-value

Discussion

This is the first comprehensive study investigating urinary shedding of Leptospira in dogs in Thailand, revealing a shedding prevalence of 4.4% in dogs in Northern, Northeastern, and Central Thailand. The results of this study are of high importance, because Leptospira shedding is a potential infection risk for people in contact with infected dogs. Moreover, shedding dogs contribute to Leptospira spread in the environment [15]. Shedding of Leptospira in dogs starts at day 7–10 after infection and lasts for 4 to 6 weeks [38–40], sometimes even over several years [38]. Time period and quantity differ individually and vary between infecting serogroups [15, 41]. The shedding prevalence in the present study of 4.4% appears rather low, but the true shedding prevalence might be underestimated because only 12/273 dogs were shedding, while anti-leptospiral antibodies were found in 33/273 (12.1%) dogs in MAT, and in 111/252 (44.0%) dogs in ELISA. Thus, almost half of the dogs had been infected at least once in their life, as none of them had ever received a Leptospira vaccine.

The shedding prevalence is comparable to other investigations. In Ireland, 7.1% (37/525) of dogs were shedding [29], 8.2% (41/500) in the USA [31], 31.1% in Iran [37], and 19.8% of the dogs in Brazil [35]. In a German study, 1.5% (3/200) of healthy dogs were shedding Leptospira [25], and in Switzerland, the shedding prevalence was 0.2% (1/408) [23]. These low European prevalences are probably due to a broader vaccine-induced immunity in the dog population. Considering the fact that human leptospirosis is endemic in Thailand with its hot humid climate, a much higher shedding prevalence would have been expected in the present survey. Possible explanations are that leptospirosis is more a seasonal disease and no natural disaster, e.g. flooding, which is well documented to enable leptospirosis outbreaks particularly during the rainy season in Thailand, occurred at the time of sampling for the present study [42, 43]. A recently published study from Thailand detected a higher shedding prevalence of 10.3% in dogs, as Leptospira were detected in the urine of 6/58 asymptomatic dogs. All these dogs came from Nan province, a rural area in Northern Thailand where leptospirosis is known to be endemic. These urine PCR-positive dogs lived in close contact with livestock and were also used for hunting armadillo and bamboo rats [32]. These facts could explain the higher shedding prevalence found in Nan province compared to the shedding prevalence in the present study.

Culturing Leptospira is not a very sensitive method. The low pH of dog urine kills Leptospira rapidly [15]. Thus, a fast transfer into culture medium is mandatory and was performed in the present study. Nevertheless, only 1/273 (D64) culture samples was positive. Phylogenetic secY analysis revealed that this dog was infected with pathogenic Leptospira interrogans. This dog was also urine PCR-positive with a PCR threshold cycle (Ct) value of 29.0, and had IgM antibodies of 1:320 without IgG antibodies in ELISA or MAT antibodies implying that the infection had been acquired very recently. As culturing Leptospira from urine is not a sensitive method, it is not surprising that no other PCR-positive dog was culture-positive. Another important aspect which could explain the failure to grow Leptospira might be related to a relatively high Ct value of ≥30 in 9/12 PCR-positive dogs, indicating a rather low quantity of excreted Leptospira DNA.

Two different antibody tests were performed. MAT is regarded as the gold standard, but its sensitivity is low. MAT is only at best serogroup-specific and cannot exactly discriminate on serovar level [15]. As no dog in this study had been vaccinated against Leptospira, vaccine-induced interference can be excluded, and the anti-leptospiral antibodies found in 33 dogs (12.1%) were related to exposure. A similar MAT antibody reactivity was found in an older survey in Thailand, revealing an antibody prevalence of 11.0% [9], and a study recently conducted in Northeastern Thailand showed similar results with 10.9% [8]. However, a study on stray dogs in Bangkok in 2009 detected a much higher MAT antibody prevalence of 89.1% (Table 1). All stray dogs of that study were sampled in the center of Bangkok in Buddhist monasteries with close contact to rats which are reservoir hosts of several Leptospira species [6]. There might be a difference in exposure rates of stray dogs and client-owned dogs of which a high number was included in the present study. Client-owned dogs are normally fed by their owners, whereas stray dogs are more likely to hunt rats and mice and thus, to become Leptospira-infected.

In the present study, almost half of the MAT-positive dogs (15/33) had antibodies to at least more than one serovar (Table 3) which is presumably due to cross-reactivity which can occur on serovar or even serogroup level [44]. Cross-reactions with other infections, the onset of an acute infection accompanied by a rise in antibodies, or persisting antibodies in a chronic course of infection might be reasons for low antibody titers in MAT [3]. In the present study, the most common reactivity was against serogroup Sejroe, which is present in Rattus rattus, Bandicota indica, and Bandicota savilei in Thailand [45]. This highlights the importance of transmission from rodents. The second frequently reactive serogroup in the present study was Icterohaemorrhagiae which is most commonly involved in human infections worldwide [46], indicating that dogs play an important role in human infection, but rats are also known reservoirs [15]. A high MAT titer could be detected in only 2/273 dogs with a titer of 1:640 against Serogroup Sejroe and Bataviae, respectively, that were also positive in urine PCR and had high IgM and IgG titers in ELISA. These results are consistent with an acute but subclinical infection in both dogs, as their physical examination was unremarkable (Table 2).

Only 12.1% dogs had antibodies in MAT in the present study, but it is possible that serovars might have been missed due to an incomplete MAT panel. MAT is also commonly still negative in early infections, while IgM ELISA already reveals positive results [47–51]. This is in line with the finding that only 2/50 dogs that were IgM ELISA-positive and IgG ELISA-negative also had detectable MAT antibodies. MAT and ELISA showed a poor agreement indicating a higher sensitivity of ELISA in early infection [47, 49–52]. Another reason might be a lower specificity of ELISA compared to MAT. In humans living in endemic countries, persistence of IgM antibodies for many months or even years after infection and repeated exposure to nonpathogenic Leptospira was suggested as an explanation for positive IgM results in healthy humans [53–56].

When comparing antibody findings to PCR results, 9/12 shedders were also ELISA-positive, whereas only 4/12 shedders had antibodies in MAT. The discrepancy between urine PCR and antibody detection is in accordance with a study on 500 dogs in which 41 dogs were shedding Leptospira, while MAT was only positive in 9 dogs [31]. Shedding can occur before MAT antibodies are present [31, 57–59]. Another explanation could be immunosuppression or ongoing shedding in chronically infected dogs in which the level of IgM and IgG antibodies had already decreased below detection threshold [15, 60].

In the present study, female sex proved to be significantly associated with Leptospira infection in multivariate analysis (Table 4). This finding is in contrast to results of other surveys in which male dogs were at higher risk [61–65] and is also in contrast to a published meta-analysis in which the variable “male dogs” was a significant factor [66]. Interestingly, no further parameters in the present study were significantly associated with Leptospira infection in multivariate analysis. Other studies found a significant predisposition of urban dogs compared to rural living dogs attributed to a higher exposure to wildlife reservoir hosts [66–70]. One could also expect a significantly higher risk of infection for stray dogs. However, client-owned outdoor and stray dogs reside in very similar living environments in both (sub)urban and rural settings in Thailand, and contact to wild-living reservoir hosts occurs in urban and rural areas of Thailand. Sanitation and hygienic standards, including rodent control, might be comparable in both environments. Thus, both stray dogs and client-owned dogs might equally contribute to environmental contamination and potential transmission of Leptospira. Moreover, access to Leptospira-contaminated water sources exists in both environments.

Conclusions

In conclusion, shedding prevalence of Leptospira in dogs taken at random in Thailand was low and not as high as expected for a tropical country. Still, in order to reduce the risk of infection and shedding, vaccines against Leptospira for dogs that are available in Thailand should be recommended as core vaccination, at least for client-owned outdoor dogs. Molecular genetic assays would be of particular importance in order to determine Leptospira strains in dogs in Thailand and globally.

Methods

Dogs

In total, 273 randomly selected dogs from rural (n = 139) and urban (n = 134) areas with outdoor access from Northern, Northeastern, and Central Thailand were included. Dogs were presented for either spaying/neutering or for rabies vaccination at public and private castration and vaccination programs. Dogs living indoors only and dogs treated with antimicrobials within the last 4 weeks prior to sampling were excluded. The study population consisted of 266 mixed-breed and 7 pure breed dogs; 154 dogs were client-owned and 119 stray; 185 dogs were female (2 spayed) and 88 male (1 neutered). No dog had received vaccination against Leptospira. After spaying/neutering and/or rabies vaccination, all client-owned dogs returned to their owners. Of the stray dogs, 77 (64.7%) were brought back and released to the territories where they had been trapped by private and public services for spaying/neutering and rabies vaccination. Forty-two of 119 stray dogs (35.3%) were admitted to governmental dog shelters (no-kill shelters) after spaying/neutering and rabies vaccination. None of the dogs were euthanized.

Sample collection

Blood samples were obtained via puncture of the cephalic or femoral vein. Serum samples were stored at −20 °C until further processing. Urine samples were collected by ultrasound-guided cystocentesis (sample volumes of 1.5 ml to 16.0 ml) and stored at 4 °C for a maximum of 24 h, and then transferred into 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany). Tubes were centrifuged (14,000 x g, room temperature) for 15 min; supernatants were discarded. Pellets were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and transferred into Eppendorf tubes. A second centrifugation (14,000 x g, room temperature) was performed for 15 min, supernatants were discarded, and pellets were resuspended in 180 μl animal tissue lysis (ATL) buffer (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and stored at −20 °C until deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) extraction.

DNA extraction and real-time PCR

For further analysis, urine samples were submitted to IDEXX Laboratories (Ludwigsburg, Germany). Total nucleic acid was extracted from urine as previously described [25]. Leptospira real-time PCR was performed using LightCycler 480 (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) with proprietary forward, reverse primers, and hydrolysis probes. The target gene was lipL32/hap1 (accession number AF245281.1), detecting only pathogenic Leptospira. This PCR had been shown to have a reproducible average analytical sensitivity of 10 DNA molecules per reaction.

Urine culture and sequencing of culture-positive sample

Of each urine sample, 0.5 ml were cultured in Ellinghausen-McCullough-Johnson-Harris (EMJH) medium as described previously [71–73]. Within 2 h after collection, 0.5 ml of each urine sample were added to a tube with 5 ml of liquid EMJH medium plus 0.2 mg/ml 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) [74] to a final dilution of 1:10. After mixing and transferring 0.5 ml of the mixture to a second tube with EMJH medium plus 0.2 mg/ml 5-FU, a dilution of 1:100 was prepared. Cultures were stored at 24–28 °C and controlled for growth of Leptospira under dark field microscope for a total of 6 months [73] approximately every 7 days. In culture with growth of Leptospira, number of grown Leptospira was estimated by microscope, using a ×20 objective. A 1:10 dilution containing Leptospira was filtered with a 0.2 μm pore size filter (Corning® Sterile Syringe Filter; Corning Incorporated, Wiesbaden, Germany) and then transferred into 9 ml fresh EMJH medium. At a density of >200 Leptospira/field, a passage of the culture into 30 ml EMJH medium was performed. At late exponential phase of leptospiral growth, aliquots of purified Leptospira were frozen with 5% dimethylsulfoxid (DMSO) (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) at −80 °C in Eppendorf tubes (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) until DNA extraction. QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was used to extract leptospiral DNA, following the manufacturer’s instructions (QIAamp® DNA Mini and Blood Mini Handbook, Appendix B: Protocol for Cultured Cells; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The DNA extract was stored at −20 °C until further analysis. For phylogenetic analysis, secY sequencing was performed as described previously [75]. A Neighbor Joining Tree (Fig. 1) was constructed using the software MEGA 7.

Microscopic agglutination test

MAT was performed as previously described [3]. Serum samples were tested for antibodies against 23 locally common pathogenic Leptospira serovars (Anhoa, Australis, Autumnalis, Ballum, Bataviae, Bratislava, Broomi, Canicola, Celledoni, Copenhageni, Coxi, Cynopteri, Djasiman, Grippotyphosa, Haemolytica, Icterohaemorrhagiae, Khorat, Paidjan, Pomona, Pyrogenes, Rachmati, Saxkoebing, Sejroe) and 1 saprophytic serovar Patoc, belonging to 15 serogroups (Australis, Autumnalis, Ballum, Bataviae, Canicola, Celledoni, Cynopteri, Djasiman, Grippotyphosa, Icterohaemorrhagiae, Javanica, Pomona, Pyrogenes, Sejroe, Semaranga) and 1 undesignated serogroup (Table 5). The cross-reacting strain Patoc I is of saprophytic origin and agglutination gives hints of an unidentified serovar not represented in the MAT panel. Two-fold dilutions of serum from 1:20 to 1:640 were tested. Threshold for reactivity was defined as ≥1:20. The titer was recorded as the last dilution in which ≥50% of the Leptospira agglutinated.

Table 5.

List of Leptospira strains tested in microscopic agglutination test (MAT)

| Genomospecies | Serogroup | Serovar | Strain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leptospira biflexa | Semaranga | Patoc | Patoc I |

| Leptospira borgpetersenii | Ballum | Ballum | Mus 127 |

| Leptospira borgpetersenii | Celledoni | Anhoa | LT 90–68 |

| Leptospira borgpetersenii | Sejroe | Saxkoebing | Mus 24 |

| Leptospira borgpetersenii | Sejroe | Sejroe | M 84 |

| Leptospira interrogans | Australis | Australis | Ballico |

| Leptospira interrogans | Australis | Bratislava | Jez Bratislava |

| Leptospira interrogans | Autumnalis | Autumnalis | Akiyami A |

| Leptospira interrogans | Autumnalis | Rachmati | Rachmat |

| Leptospira interrogans | Bataviae | Bataviae | Swart |

| Leptospira interrogans | Bataviae | Paidjan | Paidjan |

| Leptospira interrogans | Canicola | Broomi | Patane |

| Leptospira interrogans | Canicola | Canicola | Hond Utrecht IV |

| Leptospira interrogans | Djasiman | Djasiman | Djasiman |

| Leptospira interrogans | Icterohaemorrhagiae | Copenhageni | M 20 |

| Leptospira interrogans | Icterohaemorrhagiae | Icterohaemorrhagiae | RGA |

| Leptospira interrogans | Pomona | Pomona | Pomona |

| Leptospira interrogans | Pyrogenes | Pyrogenes | Salinem |

| Leptospira interrogans | Sejroe | Haemolytica | Marsh |

| Leptospira kirschneri | Cynopteri | Cynopteri | 3522 C |

| Leptospira kirschneri | Grippotyphosa | Grippotyphosa | Moskva V |

| Leptospira weilii | Celledoni | Celledoni | Celledoni |

| Leptospira weilii | Javanica | Coxi | Cox |

| Leptospira wolffii | Undesignated | Khorat | Khorat H2 |

IgM and IgG ELISA

For coating of the ELISA plates, a suspension of outer envelope antigen from 3 different strains (Leptospira interrogans serovar Canicola strain Hond Utrecht IV, serovar Icterohaemorrhagiae strain Kantorowicz, and serovar Copenhageni strain Wijnberg; produced by Leptospirosis Reference Centre, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) were used. The stock of antigen was diluted with PBS to a concentration of 2 μg/ml. Of this diluted antigen, 100 μl were added to every well. Incubation was performed overnight at room temperature. Coated plates were frozen at −20 °C until use. Dilution of all sera (controls and samples) from 1:20 to 1:2560 with dilution buffer (PBS + 1% protifar® (Nutricia Advanced Medical Nutrition, Zoetermeer, the Netherlands) + 0.05% Tween 80) was conducted twice; 1 dilution series for IgG and 1 for IgM antibodies was performed. The plates were covered with tape and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in water bath. The incubated plates were rinsed 4 times with wash buffer (distilled water + 0.05% Tween 80), conjugate was added (Goat anti-Dog IgG and Goat anti-Dog IgM (Tebu-bio.com, Heerhugowaard, the Netherlands)) and mixed. Covered plates were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in water bath. Afterwards, plates were rinsed 4 times with wash buffer (distilled water + 0.05% Tween 80), and 100 μl substrate (5.2 ml Na2HPO4 (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), 4.8 ml citric acid (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), 10 ml PBS, a 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt tablet (10 mg; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), and 10 μl H2O2 30% (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany)) was added to every well. After 30 min, reading of plates was performed at room temperature. Positive and negative controls were included on each ELISA plate. The cut-off for reactivity was ≥1:320 in IgM and IgG ELISA.

Risk factor analysis

Dog owners were requested to answer a standardized questionnaire in order to evaluate risk factors associated with Leptospira infection in dogs (Table 4). Lifestyle and activity parameters of the questionnaire were not recorded in case of stray dogs (n = 119). The approximate age of stray dogs was estimated based on dental examination. Health status of each dog was determined using a standardized physical examination protocol.

Statistical analysis

For sample size calculation, an a priori power analysis using EpiTools epidemiological calculators (Ausvet, Australia) was performed to determine an appropriate sample size to achieve adequate power. Assuming an expected prevalence of urinary shedding of Leptospira (4.0%) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of the estimation with a 5% precision, at least 236 dogs were necessary to achieve adequate power (>90.0%).

Statistical analysis to determine risk factors was performed with SPSS version 24 for Windows (IBM Cooperation, Armonk, USA). For univariate analysis, Fisher’s exact test was used to assess risk factors associated with Leptospira infection including all dogs with urinary shedding and/or presence of antibodies in MAT and/or in ELISA, (defined as “Leptospira-infected”) (Table 4). In addition, 2 risk factor analyses were performed for the following 2 subgroups: presence of antibodies against Leptospira determined by MAT (see Additional file 1: Table S1), and urinary shedding of Leptospira detected by PCR (see Additional file 2: Table S2). Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed using parameters with at least 205 observations as independent variables, as available data of ≥75.0% of the dogs was chosen as mandatory criteria for entering. Backwards stepwise selection based on Wald was performed to detect the most important variables for being Leptospira-infected. Following parameters met the inclusion criteria: age; breed; sex; neutering status; origin; environment. A value of p <0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1 : Table S1. Risk factor analysis for dogs with MAT antibody titers (≥1:20) against Leptospira. Univariate and multivariate analysis for risk factors associated with MAT titers (cut-off: ≥1:20) in 33/273 dogs. For multivariate analysis, backward stepwise selection based on Wald was performed for the following categories: age, breed, sex, neutering status, origin, and environment.

Additional file 2 : Table S2. Risk factor analysis for dogs with urinary shedding of Leptospira determined by PCR. Univariate and multivariate analysis for risk factors associated with positive urine PCR results in 12/273 dogs. For multivariate analysis, backward stepwise selection based on Wald was performed for the following categories: age, breed, sex, neutering status, origin, and environment.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Department of Livestock Development (DLD) in Bangkok; the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA); SNIP clinic Bangkok; and Soi Dogs Bangkok for making the sample collection possible within the frame of their neutering and vaccination programs. The authors would also like to acknowledge the assistance during the field trips of the students of the Veterinary Faculty of Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, and thank all dog owners, veterinarians, and veterinary stuff involved in this study. The authors also thank Dr. Anna Rieger for her input in the statistics and Boehringer Ingelheim for funding and supporting the study, and especially Dr. Jean-Christophe Thibault for his contribution.

Abbreviations

- 5-FU

5-Fluorouracil

- ATL

Animal tissue lysis

- CI

Confidence interval

- Ct

Threshold cycle

- DMSO

Dimethylsulfoxid

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- EMJH

Ellinghausen-McCullough-Johnson-Harris

- IgG

Immunoglobulin G

- IgM

Immunoglobulin M

- OR

Odds ratio

- p

P-value

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

Authors’ contributions

Conception and design of the work: KH. Acquisition of data: KA, KH, SL, RP. Analysis of data: KA, MGAG, AK, NPr, RP, PJ, NPa, AAA, EMB, JAW. Interpretation of data: KA, KH, SR, MGAG. Drafted the paper: KA. Substantively revised the paper: KH, EMB, NPa, MGAG. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim, Lyon, France. Boehringer Ingelheim did not play any role elsewhere in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, nor in the content of the manuscript or submission for publication.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the results of the secY sequencing is deposited in GenBank at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/ under accession numbers MN862540-MN862558.

Raw data (Excel file) is available from the corresponding author on request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This prospective study was ethically reviewed and approved by the Chulalongkorn University Animal Care and Use Committee of Bangkok, Thailand (CU-ACUC; Animal Use Protocol No.: 1731043). All dog owners agreed in a written owner consent. For stray dogs, authorized veterinarians and supervisors gave their written consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

NPa is employed at IDEXX Laboratories, Ludwigsburg. This laboratory offers the IDEXX Leptospira RealPCR Test on a commercial basis and performed the testing in this study.

MGAG and AAA work at the OIE and National Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Leptospirosis and commercially performed MAT and phylogenetic analysis in the present study.

EMB and JAW work at the Department of Infectious Diseases and Immunology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University and commercially performed IgM and IgG ELISA in this study.

None of these companies played a role in the study design, in the collection and interpretation of data, or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

KH has given talks for MSD, Merial, Boehringer Ingelheim, and IDEXX. She participated in research funded by or using products from MSD, Merial, Boehringer, Zoetis, Megacor, Biogal, and Scil.

There is no commercial conflict of interest as the information generated here is solely for scientific dissemination. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Kerstin Altheimer, Email: altheimerkerstin@gmail.com.

Prapaporn Jongwattanapisan, Email: Prapaporn.J@chula.ac.th.

Supol Luengyosluechakul, Email: lsupol@chula.ac.th.

Rosama Pusoonthornthum, Email: drrosama@gmail.com.

Nuvee Prapasarakul, Email: Nuvee.P@chula.ac.th.

Alongkorn Kurilung, Email: theng_ja@hotmail.com.

Els M. Broens, Email: E.M.Broens@uu.nl

Jaap A. Wagenaar, Email: j.wagenaar@uu.nl

Marga G. A. Goris, Email: m.goris@amc.uva.nl

Ahmed A. Ahmed, Email: a.ahmed@amc.uva.nl

Nikola Pantchev, Email: nikola-pantchev@idexx.com.

Sven Reese, Email: sven.reese@lmu.de.

Katrin Hartmann, Email: hartmann@medizinische-kleintierklinik.de.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12917-020-2230-0.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). Neglected tropical diseases, hidden successes, emerging opportunities. Geneva; 2009. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241598705_eng.pdf. Accessed 4 Feb 2019.

- 2.Adler Ben, de la Peña Moctezuma Alejandro. Leptospira and leptospirosis. Veterinary Microbiology. 2010;140(3-4):287–296. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goris MGA, Hartskeerl RA. Leptospirosis serodiagnosis by the microscopic agglutination test. Curr Protoc Microbiol. 2014;32:12E.5.1–12E.518. doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc12e05s32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tangkanakul W, Smits HL, Jatanasen S, Ashford DA. Leptospirosis: an emerging health problem in Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2005;36(2):281–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ProMED-mail . Leptospirosis - Thailand (03): Nakhon Si Thammarat: ProMED-mail. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jittapalapong S, Sittisan P, Sakpuaram T, Kabeya H, Maruyama S, Inpankaew T. Coinfection of Leptospira spp and Toxoplasma gondii among stray dogs in Bangkok, Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2009;40(2):247–52. [PubMed]

- 7.Chotivanich S, Pinprasong B, Suwancharoen D. Serologic survey of leptospirosis in pigs, dogs, beef cattle, buffaloes and dairy cattle in Chaiyaphum Province. DLD Tech Paps. 2000;5:33–54 [in Thai]. http://pvlo-cpm.dld.go.th/knowledge/research/r004-srissmai.pdf. Accessed 8 Feb 2019.

- 8.Pumipuntu N, Suwannarong K. Seroprevalence of Leptospira spp. in cattle and dogs in Mahasarakham Province, Thailand. J Health Res. 2016;30(3):223–6. 10.14456/jhr.2016.30.

- 9.Meeyam T, Tablerk P, Petchanok B, Pichpol D, Padungtod P. Seroprevalence and risk factors associated with leptospirosis in dogs. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2006;37(1):148–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niwetpathomwat A, Assarasakorn S. Preliminary investigation of canine leptospirosis in a rural area of Thailand. Med Weter. 2007;63(1):59–61. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jittapalapong S, Pinyopanuwat N, Boonchob S, Chimnoi W, Jansawan W. Impact on animal rearing or yielding in the public land in Thailand. A manual of regulation of animal rearing or yielding in the public land of Thailand. Bangkok: Kasetsart University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aslantaş Özkan, Özdemir Vildan, Kiliç Selçuk, Babür Cahit. Seroepidemiology of leptospirosis, toxoplasmosis, and leishmaniosis among dogs in Ankara, Turkey. Veterinary Parasitology. 2005;129(3-4):187–191. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brod Claudiomar Soares, Aleixo José Antonio Guimarães, Jouglard Sandra Denise Dorneles, Fernandes Cláudia Pinho Hartleben, Teixeira José Luís Rodrigues, Dellagostin Odir Antônio. Evidência do cão como reservatório da leptospirose humana: isolamento de um sorovar, caracterização molecular e utilização em inquérito sorológico. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2005;38(4):294–300. doi: 10.1590/S0037-86822005000400003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Paula Dreer Márcia, Gonçalves Daniela, da Silva Caetano Isabel, Gerônimo Edson, Menegas Paulo, Bergo Danilo, Ruiz Lopes-Mori Fabiana, Benitez Aline, de Freitas Julio, Evers Fernanda, Navarro Italmar, Martins Lisiane de. Toxoplasmosis, leptospirosis and brucellosis in stray dogs housed at the shelter in Umuarama municipality, Paraná, Brazil. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases. 2013;19(1):23. doi: 10.1186/1678-9199-19-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levett PN. Leptospirosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14(2):296–326. doi: 10.1128/cmr.14.2.296-326.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weekes C.C., Everard C.O.R., Levett P.N. Seroepidemiology of canine leptospirosis on the island of Barbados. Veterinary Microbiology. 1997;57(2-3):215–222. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(97)00127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Douglin C. P. Risk Factors for Severe Leptospirosis in the Parish of St. Andrew, Barbados. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 1997;3(1):78–80. doi: 10.3201/eid0301.970114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jansen Andreas, Schöneberg Irene, Frank Christina, Alpers Katharina, Schneider Thomas, Stark Klaus. Leptospirosis in Germany, 1962–2003. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005;11(7):1048–1054. doi: 10.3201/eid1107.041172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LEAL-CASTELLANOS C. B., GARCÍA-SUÁREZ R., GONZÁLEZ-FIGUEROA E., FUENTES-ALLEN J. L., ESCOBEDO-DE LA PEÑA J. Risk factors and the prevalence of leptospirosis infection in a rural community of Chiapas, Mexico. Epidemiology and Infection. 2003;131(3):1149–1156. doi: 10.1017/S0950268803001201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meites Elissa, Jay Michele T., Deresinski Stanley, Shieh Wun-Ju, Zaki Sherif R., Tompkins Lucy, Smith D. Scott. Reemerging Leptospirosis, California. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004;10(3):406–412. doi: 10.3201/eid1003.030431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simon M. C., Ortega C., Alonso J. L., Girones O., Muzquiz J. L., Garcia J. Risk factors associated with the seroprevalence of leptospirosis among students at the veterinary school of Zaragoza University. Veterinary Record. 1999;144(11):287–291. doi: 10.1136/vr.144.11.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trevejo Rosalie T., Rigau‐Pérez José G., Ashford David A., McClure Emily M., Jarquín‐González Carlos, Amador Juan J., de los Reyes José O., Gonzalez Alcides, Zaki Sherif R., Shieh Wun‐Ju, McLean Robert G., Nasci Roger S., Weyant Robbin S., Bolin Carole A., Bragg Sandra L., Perkins Bradley A., Spiegel Richard A. Epidemic Leptospirosis Associated with Pulmonary Hemorrhage—Nicaragua, 1995. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1998;178(5):1457–1463. doi: 10.1086/314424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delaude Alessandro, Rodriguez-Campos Sabrina, Dreyfus Anou, Counotte Michel Jacques, Francey Thierry, Schweighauser Ariane, Lettry Sophie, Schuller Simone. Canine leptospirosis in Switzerland—A prospective cross-sectional study examining seroprevalence, risk factors and urinary shedding of pathogenic leptospires. Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 2017;141:48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Latosinski Giulia Soares, Fornazari Felipe, Babboni Selene Daniela, Caffaro Karen, Paes Antonio Carlos, Langoni Helio. Serological and molecular detection of Leptospira spp in dogs. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2018;51(3):364–367. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0276-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Llewellyn JR, Krupka-Dyachenko I, Rettinger AL, Dyachenko V, Stamm I, Kopp PA, et al. Urinary shedding of leptospires and presence of Leptospira antibodies in healthy dogs from upper Bavaria. Berl Münch Tierärztl Wochenschr. 2016;129(5–6):251–7. [PubMed]

- 26.Romero-Vivas Claudia M. E., Agudelo-Flórez Piedad, Thiry Dorothy, Levett Paul N., Falconar Andrew K. I., Cuello-Pérez Margarett. Cross-Sectional Study of Leptospira Seroprevalence in Humans, Rats, Mice, and Dogs in a Main Tropical Sea-Port City. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2013;88(1):178–183. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaidi Sara, Bouam Amar, Bessas Amina, Hezil Djamila, Ghaoui Hicham, Ait-Oudhia Khatima, Drancourt Michel, Bitam Idir. Urinary shedding of pathogenic Leptospira in stray dogs and cats, Algiers: A prospective study. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(5):e0197068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Troìa R., Balboni A., Zamagni S., Frigo S., Magna L., Perissinotto L., Battilani M., Dondi F. Prospective evaluation of rapid point-of-care tests for the diagnosis of acute leptospirosis in dogs. The Veterinary Journal. 2018;237:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2018.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rojas P, Monahan AM, Schuller S, Miller IS, Markey BK, Nally JE. Detection and quantification of leptospires in urine of dogs: a maintenance host for the zoonotic disease leptospirosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;29(10):1305–1309. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-0991-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benacer D, Thong KL, Ooi PT, Souris M, Lewis JW, Ahmed AA, et al. Serological and molecular identification of Leptospira spp. in swine and stray dogs from Malaysia. Trop Biomed. 2017;34(1):89–97. [PubMed]

- 31.Harkin KR, Roshto YM, Sullivan JT, Purvis TJ, Chengappa MM. Comparison of polymerase chain reaction assay, bacteriologic culture, and serologic testing in assessment of prevalence of urinary shedding of leptospires in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2003;222(9):1230–1233. doi: 10.2460/javma.2003.222.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurilung Alongkorn, Chanchaithong Pattrarat, Lugsomya Kittitat, Niyomtham Waree, Wuthiekanun Vanaporn, Prapasarakul Nuvee. Molecular detection and isolation of pathogenic Leptospira from asymptomatic humans, domestic animals and water sources in Nan province, a rural area of Thailand. Research in Veterinary Science. 2017;115:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2017.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miotto Bruno Alonso, Guilloux Aline Gil Alves, Tozzi Barbara Furlan, Moreno Luisa Zanolli, da Hora Aline Santana, Dias Ricardo Augusto, Heinemann Marcos Bryan, Moreno Andrea Micke, Filho Antônio Francisco de Souza, Lilenbaum Walter, Hagiwara Mitika Kuribayashi. Prospective study of canine leptospirosis in shelter and stray dog populations: Identification of chronic carriers and different Leptospira species infecting dogs. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(7):e0200384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oliveira ST, Messick JB, Biondo AW, dos Santos AP, Stedile R, Dalmolin ML, et al. Exposure to Leptospira spp. in sick dogs, shelter dogs and dogs from an endemic area: points to consider. Acta Sci Vet. 2012;40(3):1–7.

- 35.Sant'anna R, Vieira AS, Grapiglia J, Lilenbaum W. High number of asymptomatic dogs as leptospiral carriers in an endemic area indicates a serious public health concern. Epidemiol Infect. 2017;145(9):1852–1854. doi: 10.1017/s0950268817000632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zakeri Sedigheh, Khorami Nargess, Ganji Zahra F., Sepahian Neda, Malmasi Abdol-Ali, Gouya Mohammad Mehdi, Djadid Navid D. Leptospira wolffii, a potential new pathogenic Leptospira species detected in human, sheep and dog. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2010;10(2):273–277. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khorami N, Malmasi A, Zakeri S, Zahraei Salehi T, Abdollahpour G, Nassiri SM, et al. Screening urinalysis in dogs with urinary shedding of leptospires. Comp Clin Path. 2010;19(3):271–274. doi: 10.1007/s00580-009-0856-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bal AE, Gravekamp C, Hartskeerl RA, De Meza-Brewster J, Korver H, Terpstra WJ. Detection of leptospires in urine by PCR for early diagnosis of leptospirosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32(8):1894–1898. doi: 10.1128/JCM.32.8.1894-1898.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greenlee Justin J., Alt David P., Bolin Carole A., Zuerner Richard L., Andreasen Claire B. Experimental canine leptospirosis caused byLeptospira interrogansserovars pomona and bratislava. American Journal of Veterinary Research. 2005;66(10):1816–1822. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2005.66.1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gsell O. Leptospirosen. In: Gsell O, Mohr W, editors. [Infektionskrankheiten Band II Krankheiten durch Bakterien Teil 2]. 2. 1. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer; 1968. pp. 826–879. [Google Scholar]

- 41.van de Maele I, Claus A, Haesebrouck F, Daminet S. Leptospirosis in dogs: a review with emphasis on clinical aspects. Vet Rec. 2008;163(14):409–413. doi: 10.1136/vr.163.14.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chadsuthi Sudarat, Bicout Dominique J., Wiratsudakul Anuwat, Suwancharoen Duangjai, Petkanchanapong Wimol, Modchang Charin, Triampo Wannapong, Ratanakorn Parntep, Chalvet-Monfray Karine. Investigation on predominant Leptospira serovars and its distribution in humans and livestock in Thailand, 2010-2015. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2017;11(2):e0005228. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ward MP. Seasonality of canine leptospirosis in the United States and Canada and its association with rainfall. Prev Vet Med. 2002;56(3):203–213. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5877(02)00183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller MD, Annis KM, Lappin MR, Lunn KF. Variability in results of the microscopic agglutination test in dogs with clinical leptospirosis and dogs vaccinated against leptospirosis. J Vet Intern Med. 2011;25(3):426–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.0704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wangroongsarb P, Petkanchanapong W, Yasaeng S, Imvithaya A, Naigowit P. Survey of leptospirosis among rodents in epidemic areas of Thailand. J Trop Med Parasitol. 2002;25(2):55–58. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Picardeau M. Diagnosis and epidemiology of leptospirosis. Med Mal Infect. 2013;43(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adler B, Murphy AM, Locarnini SA, Faine S. Detection of specific anti-leptospiral immunoglobulins M and G in human serum by solid-phase enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1980;11(5):452–457. doi: 10.1128/JCM.11.5.452-457.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cumberland P, Everard C O, Levett P N. Assessment of the efficacy of an IgM-elisa and microscopic agglutination test (MAT) in the diagnosis of acute leptospirosis. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1999;61(5):731–734. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goris MGA, Leeflang MMG, Boer KR, Goeijenbier M, van Gorp ECM, Wagenaar JFP, et al. Establishment of valid laboratory case definition for human leptospirosis. J Bacteriol Parasitol. 2012;3(2). 10.4172/2155-9597.1000132.

- 50.Ribotta MJ, Higgins R, Gottschalk M, Lallier R. Development of an indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of leptospiral antibodies in dogs. Can J Vet Res. 2000;64(1):32–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lizer J., Velineni S., Weber A., Krecic M., Meeus P. Evaluation of 3 Serological Tests for Early Detection Of Leptospira -specific Antibodies in Experimentally Infected Dogs. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 2017;32(1):201–207. doi: 10.1111/jvim.14865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hartman EG, van Houten M, van der Donk JA, Frik JF. Determination of specific anti-leptospiral immunoglobulins M and G in sera of experimentally infected dogs by solid-phase enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1984;7(1):43–51. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(84)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Blacksell S. D., Smythe L., Phetsouvanh R., Dohnt M., Hartskeerl R., Symonds M., Slack A., Vongsouvath M., Davong V., Lattana O., Phongmany S., Keolouangkot V., White N. J., Day N. P. J., Newton P. N. Limited Diagnostic Capacities of Two Commercial Assays for the Detection of Leptospira Immunoglobulin M Antibodies in Laos. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology. 2006;13(10):1166–1169. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00219-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cumberland P., Everard C.O.R., Wheeler J.G., Levett P.N. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;17(7):601–608. doi: 10.1023/A:1015509105668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hartskeerl RA, Smits HL, Korver H, Goris MGA, Terpstra WJ. International course on laboratory methods for the diagnosis of leptospirosis. 5. Amsterdam: Royal Tropical Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wagenaar J.F.P., Falke T.H.F., Nam N.V., Binh T.Q., Smits H.L., Cobelens F.G.J., de Vries P. J. Rapid serological assays for leptospirosis are of limited value in southern Vietnam. Annals of Tropical Medicine & Parasitology. 2004;98(8):843–850. doi: 10.1179/000349804X3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Clegg F., Heath P. Subclinical L icterohaemorrhagiae infection in dogs associated with a case of human leptospirosis. Veterinary Record. 1975;96(17):385–385. doi: 10.1136/vr.96.17.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Feigin RD, Lobes LA, Jr, Anderson D, Pickering L. Human leptospirosis from immunized dogs. Ann Intern Med. 1973;79(6):777–785. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-79-6-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Broek A. H. M., Thrusfield M. V., Dobbiet G. R., Ellisi W. A. A serological and bacteriological survey of leptospiral infection in dogs in Edinburgh and Glasgow. Journal of Small Animal Practice. 1991;32(3):118–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.1991.tb00526.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Turner LH. Leptospirosis. Br Med J. 1969;1(5638):231–235. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5638.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Adin CA, Cowgill LD. Treatment and outcome of dogs with leptospirosis: 36 cases (1990-1998) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2000;216(3):371–375. doi: 10.2460/javma.2000.216.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee HS, Guptill L, Johnson AJ, Moore GE. Signalment changes in canine leptospirosis between 1970 and 2009. J Vet Intern Med. 2014;28(2):294–299. doi: 10.1111/jvim.12273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Major A, Schweighauser A, Francey T. Increasing incidence of canine leptospirosis in Switzerland. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(7):7242–7260. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110707242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ward Michael P., Glickman Lawrence T., Guptill Lynn F. Prevalence of and risk factors for leptospirosis among dogs in the United States and Canada: 677 cases (1970-1998) Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2002;220(1):53–58. doi: 10.2460/javma.2002.220.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ward MP, Guptill LF, Prahl A, Wu CC. Serovar-specific prevalence and risk factors for leptospirosis among dogs: 90 cases (1997-2002) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2004;224(12):1958–1963. doi: 10.2460/javma.2004.224.1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Azócar-Aedo L., Monti G. Meta-Analyses of Factors Associated with Leptospirosis in Domestic Dogs. Zoonoses and Public Health. 2015;63(4):328–336. doi: 10.1111/zph.12236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.ADLER H., VONSTEIN S., DEPLAZES P., STIEGER C., FREI R. Prevalence of Leptospira spp. in various species of small mammals caught in an inner-city area in Switzerland. Epidemiology and Infection. 2002;128(1):107–109. doi: 10.1017/S0950268801006380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Koizumi N., Muto M., Tanikawa T., Mizutani H., Sohmura Y., Hayashi E., Akao N., Hoshino M., Kawabata H., Watanabe H. Human leptospirosis cases and the prevalence of rats harbouring Leptospira interrogans in urban areas of Tokyo, Japan. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2009;58(9):1227–1230. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.011528-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ward MP, Guptill LF, Wu CC. Evaluation of environmental risk factors for leptospirosis in dogs: 36 cases (1997-2002) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2004;225(1):72–77. doi: 10.2460/javma.2004.225.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alton GD, Berke O, Reid-Smith R, Ojkic D, Prescott JF. Increase in seroprevalence of canine leptospirosis and its risk factors, Ontario 1998-2006. Can J Vet Res. 2009;73(3):167–175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ellinghausen HC Jr, McCullough WG. Nutrition of Leptospirapomona and growth of 13 other serotypes: Fractionation of oleic albumin complex and a medium of bovine albumin and polysorbate 80. Am J Vet Res. 1965;26:45–51. [PubMed]

- 72.Johnson RC, Harris VG. Differentiation of pathogenic and saprophytic letospires. I. Growth at low temperatures. J Bacteriol. 1967;94(1):27–31. doi: 10.1128/JB.94.1.27-31.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zuerner RL. Laboratory maintenance of pathogenic Leptospira. Curr Protoc Microbiol. 2005;1:12E.1.1–13. 10.1002/9780471729259.mc12e01s00. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Johnson Russell C., Rogers Palmer. 5-FLUOROURACIL AS A SELECTIVE AGENT FOR GROWTH OF LEPTOSPIRAE. Journal of Bacteriology. 1964;87(2):422–426. doi: 10.1128/JB.87.2.422-426.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Victoria Berta, Ahmed Ahmed, Zuerner Richard L., Ahmed Niyaz, Bulach Dieter M., Quinteiro Javier, Hartskeerl Rudy A. Conservation of the S10-spc-α Locus within Otherwise Highly Plastic Genomes Provides Phylogenetic Insight into the Genus Leptospira. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(7):e2752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1 : Table S1. Risk factor analysis for dogs with MAT antibody titers (≥1:20) against Leptospira. Univariate and multivariate analysis for risk factors associated with MAT titers (cut-off: ≥1:20) in 33/273 dogs. For multivariate analysis, backward stepwise selection based on Wald was performed for the following categories: age, breed, sex, neutering status, origin, and environment.

Additional file 2 : Table S2. Risk factor analysis for dogs with urinary shedding of Leptospira determined by PCR. Univariate and multivariate analysis for risk factors associated with positive urine PCR results in 12/273 dogs. For multivariate analysis, backward stepwise selection based on Wald was performed for the following categories: age, breed, sex, neutering status, origin, and environment.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the results of the secY sequencing is deposited in GenBank at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/ under accession numbers MN862540-MN862558.

Raw data (Excel file) is available from the corresponding author on request.