| Declaration of potential conflict of interest of authors/collaborators of Update of the Brazilian Guidelines on Nuclear Cardiology - 2020If the last three years the author/developer of the Update: | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Names Members of the Update | Participated in clinical studies and/or experimental trials supported by pharmaceutical or equipment related to the guideline in question | Has spoken at events or activities sponsored by industry related to the guideline in question | It was (is) advisory board member or director of a pharmaceutical or equipment | Committees participated in completion of research sponsored by industry | Personal or institutional aid received from industry | Produced scientific papers in journals sponsored by industry | It shares the industry |

| Barbara Juarez Amorim | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Claudio Tinoco Mesquita | NIH | Bayer | No | No | Pfizer | No | No |

| Gabriel Blacher Grossman | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| João Vicente Vitola | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| José Claudio Meneghetti | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| José Roberto Nolasco de Araújo | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Lara Cristiane Terra Ferreira Carreira | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Luiz Eduardo Mastrocola | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Rafael Willain Lopes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Ronaldo de Souza Leao Lima | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Simone Cristina Soares Brandão | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| William Azem Chalela | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

HED - 11C - meta-hydroxyephedrine labeled with Carbon-11

PIB-11C - PET - pittsburgh B compound labeled with carbon-11 by PET imaging

MIBG-123I - metaiodobenzylguanidine labeled with iodine 123

13NH3 - ammonia labeled with Nitrogen-13

H2O-15O - water labeled with Oxygen-15

FDG-18F - fluorodeoxyglucose labeled with Fluorine-18

FDG-18F - PET/TC - fluorodeoxyglucose labeled with fluorine-18 by hybrid imaging (positron emission tomography coupled with computerized tomography)

Sodium fluoride-18F - fluorine-18 labeled Sodium Fluoride for PET Amyloid Imaging

201Hg - mercury-201

201Tl - thallium-201

82Rb - rubidium-82

82Sr - strontium-82

99mTc - technetium-99m

MIBI-99mTc - technetium-99m-labeled SESTAMIBI or MIBI

Pyrophosphate-99mTc - technetium-99m-labeled pyrophosphate

ACEI - angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors

ACS - acute coronary syndrome

Aden - adenosine

ADMIRE-HF - AdreView Myocardial Imaging for Risk Evaluation in HF

AF - atrial fibrillation

AHA - American Heart Association

AL - light chain immunoglobulin

ALARA - as low as reasonably achievable

AMI - acute myocardial infarction

angio-CT - angiotomography of coronary arteries

ARB - angiotensin receptor blockers

ATP III - Adult Treatment Panel, from the Program for Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Cholesterol in Adults

AUC - area under the curve

AVB - atrioventricular blockage

BMI - body mass index

BNP - B-natriuretic peptide

CA - cardiac amyloidosis

CABG - coronary artery bypass graft

CC - coronary calcium

CAD - coronary artery disease

CCA - coronary cineangiography

CFR - coronary flow reserve

CHF - congestive heart failure

CIED - cardiac implantable electronic devices

CMR - cardiac magnetic resonance

CONFIRM - Coronary CT Angiography Evaluation for Clinical Outcomes: an International Multicenter Registry

COURAGE - Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive druG Evaluation Trial

CPU - chest pain unit

CRP - C reactive protein

CRT - cardiac resynchronization therapy

CS - calcium score

CTX - cardiotoxicity

CV - cardiovascular

Cx - circumflex coronary artery

CZT - cadmium zinc telluride semiconductors

DDD - artificial pacemaker stimulation mode

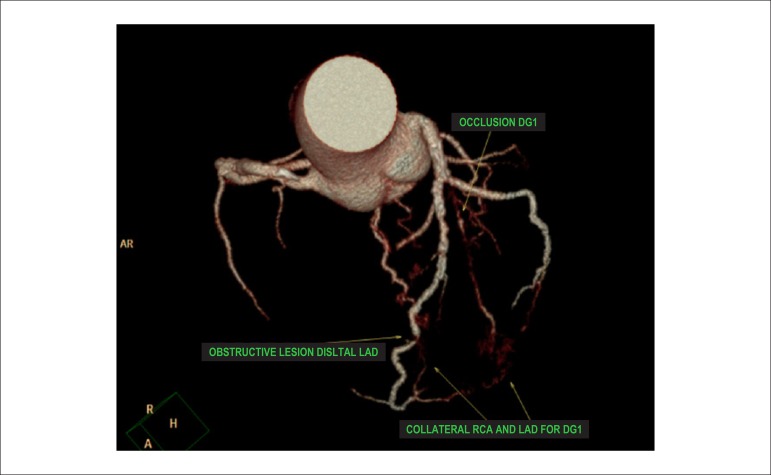

DG1 - diagonal 1 coronary artery

Dipy. - dipyridamole

DM - diabetes mellitus

Dobut. - dobutamine

DS - duke score

ECG - 12-lead electrocardiogram

ECHO - echocardiogram

EDV - end diastolic volume

ERASE Chest Pain -The Emergency Room Assessment of Sestamibi for Evaluation of Chest Pain Trial

ESV - end systolic volume

ET - exercise testing

FAME - Fractional Flow Reserve versus Angiography for Guidance of PCI in Patients with Multivessel Coronary Artery Disease

FBP - filtered back-projection

FDA - food and drug administration

FDG-6-P - fluorodeoxyglucose - 6 - phosphate

FFA - free fatty acids

FFR - fractional flow reserve

FRS - Framingham risk score

Gated-SPECT - myocardial perfusion imaging by single photon emission computed tomography technique synchronized with electrocardiogram

HBP - high blood pressure

HF - heart failure

HFpEF - heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

HFrEF - heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

HMR - heart to mediastinum ratio

HR - heart rate

IAEA - International Atomic Energy Agency

ICD - implantable cardioverter defibrillator

ICNC - International Conference of Nuclear Cardiology

IE - infectious endocarditis

IFR - instantaneous flow reserve/instantaneous wave-free ratio

INCAPS - IAEA Nuclear Cardiology Protocols Cross-Sectional Study

ISCHEMIA - International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness with Medical and Invasive Approaches

IV - intravenously/intravenous

keV - kilo-electron volts

LAD - left anterior descending coronary artery

LAFB - left anterior fascicular block

LBBB - left bundle branch block

LV - left ventricle

LVAD / VAD - left ventricular assist device / ventricular assist devices

LVEF - left ventricular ejection fraction

MBF - myocardial blood flow

MBFR - myocardial blood flow reserve

MBq - megabequerel

mCi - milicurie

MET - metabolic equivalent.

MFR - myocardial flow reserve

MIBI / SESTAMIBI - 2-methoxy-isobutyl-isonitrile

MPS - myocardial perfusion scintigraphy

MR - magnetic resonance

MRS - myocardial revascularization surgery

mSv - millisieverts

MVO2 - myocardial oxygen consumption

NaI - sodium iodine

NE - norepinephrine

NPV - negative predictive value

NSTEMI - non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction

NSVT - nonsustained ventricular tachycardia

NYHA HF - New York Heart Association Heart Failure Class

OMT - optimized medical therapy

OR - odds ratio

OSEM - ordered subset expectation maximization

PAREPET - prediction of arrhythmic events with positron emission tomography

PARR-2 - PET and Recovery after Revascularization study

PCI - percutaneous coronary intervention

PET - positron emission tomography

PET/CT - positron emission tomography coupled with computed tomography (hybrid imaging)

PET/MR - positron emission tomography coupled with magnetic resonance (hybrid imaging)

PM - pacemaker

PREMIER - Performance of Rest Myocardial Perfusion Imaging in the Management of Acute Chest Pain in the Emergency Room in Developing Nations

PROCAM - PROSpective CArdiovascular Munster Study

PROMISE - Prospective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain

RCA - right coronary artery

Regad. - regadenoson

RESCUE - Randomized Evaluation of patients with Stable angina Comparing diagnostic Examinations

ROC - receiver operating characteristics

ROI - regions of interest

ROMICAT II - rule out myocardial infarction by cardiac computed tomography

RV - right ventricle/ventricular

SBC - Brazilian Society of Cardiology

SBMN - Brazilian Society of Nuclear Medicine

SBP - systolic blood pressure

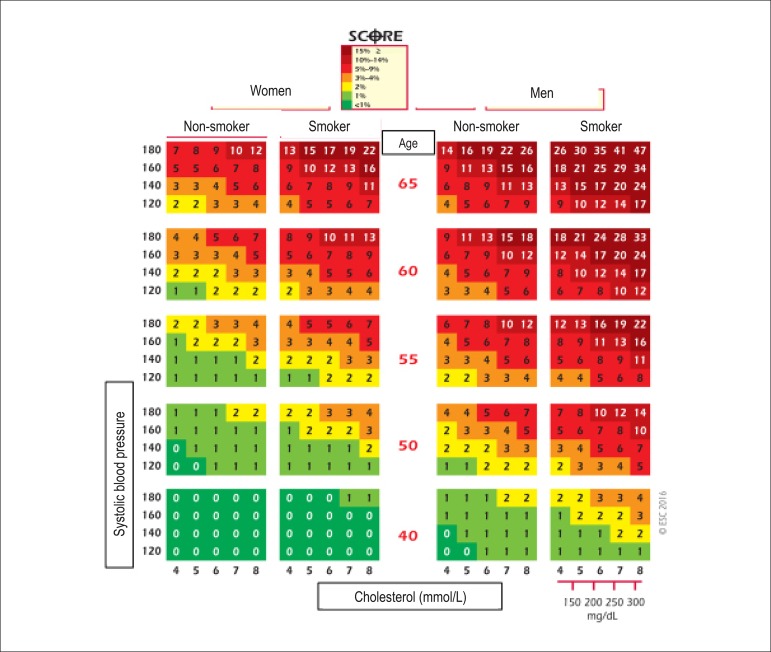

SCORE - Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation Study

SDS - summed difference score

Shining / Shine Through - residual activity effect

SPECT - myocardial perfusion imaging by single photon emission computed tomography

SRS - summed rest/redistribution score

SSS - summed stress score

STEMI - ST segment elevation myocardial infarction

STICH - Surgical Treatment for Ischemic Heart Failure study

SUS - Brazil’s public Single Health System (acronym in Portuguese)

SUV - standard uptake value

TIA - transient ischemic attack

TID - transient ischemic dilatation

TOF - time of flight

TTR - transthyretin

TTR CA - transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis

UA - unstable angina

USA - United States of America

VAD - ventricular assist devices

VF - ventricular fibrillation

VT - ventricular tachycardia

WR - myocardial washout rate

1. Introduction

Nuclear cardiology is a non-anatomical, physiological imaging method. The use of radioactive or radiopharmaceutical substances makes it possible to study several physiopathological mechanisms of cardiovascular disease in vivo. Via this imaging technique, it is also possible to visualize and accompany an instituted therapy’s physiological effects on cardiac function, on the cellular and biochemical level. Of all the applications of nuclear medicine in cardiology, scintigraphy or myocardial perfusion imaging with technetium-99m-labeled radiopharmaceuticals synchronized with electrocardiogram (Gated-SPECT), is the most common exam in clinical practice. For this reason, this technique will be the most discussed in these Guidelines.

Recent years have, however, seen a growing concern among the scientific community regarding rational and optimized use of ionizing radiation in medicine. Cardiovascular imaging, moreover, encompasses all functional and anatomical imaging techniques and should, in this context, be used rationally and cost-effectively. Other applications of nuclear medicine in cardiology have also emerged and gained prominence during the past decades, especially positron emission tomography (PET) for the study of coronary flow reserve, cardiac sympathetic activity, and inflammatory/infectious processes, and cardiac amyloidosis (CA). All of these aspects have been taken into consideration and will be covered in detail in the chapters developed herein.

Guidelines recommendations are highly valuable tools for medical activity of the highest quality. The objective is to support and aid doctors in making decisions regarding their patients, by elaborating orientations which may be useful as part of the decision-making process. No Guidelines, however, should be replaced by the abilities, experience, and clinical judgments of specialized professionals who are have the final say in their decisions concerning each individual patient.

In general, whenever possible and applicable, classifications of recommendation have been adopted for indicating cardiac scintigraphy, supported by levels of evidence, in accordance with the recommendations established by classical cardiology guidelines (Table 1).

Table 1.

Classes of recommendation and levels of evidence

| Classes of recommendation |

| Class I - Conditions for which there is conclusive evidence or, in the absence of conclusive evidence, general consensus that the procedure is safe and useful/effective |

| Class II - Conditions for which there are conflicting evidence and/or divergent opinions regarding the procedure's safety and usefulness/effectiveness |

| Class IIA - Weight or evidence/opinion in favor of the procedure. The majority of studies/experts approve. |

| Class IIB - Safety and usefulness/effectiveness less well established, with no prevailing opinions in favor |

| Class III - Conditions for which there is evidence and/or consensus that the procedure is not useful/effective and could, in some cases, be harmful |

| Levels of Evidence |

| Level A - Data obtained from multiple concordant large randomized trials and/or robust meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials |

| Level B - Data obtained from less robust meta-analysis, from a single randomized trial, or from non-randomized (observational) trials |

| Level C - Data obtained through consensus of expert opinion |

Based on current evidence, this document, which does not function as a substitute, practically and objectively adds important data to and updates the Brazilian Cardiology Society’s (SBC) First Guidelines and Update on Nuclear Cardiology, both of which were published by the Brazilian Archives of Cardiology (Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia), in 2002 and 2005, respectively.

As in the previously mentioned documents, those who participated in the elaboration of these Guidelines are considered specialists in their respective areas and were, for this reason, chosen to develop the chapters thereon. The committed involvement of all colleagues representing the SBC and the Brazilian Society of Nuclear Medicine (SBMN) have made the elaboration of these new update of Brazilian Guidelines on Nuclear Cardiology possible. It is our hope that they will be of great use, especially to Cardiologists and Nuclear Medicine and Clinical Physicians in Brazil. The Organizing Committee appreciates the collaboration of all those involved.

2. Addendum to the ISCHEMIA Study*

At the time of publication of this guideline, the International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness with Medical and Invasive Approaches (ISCHEMIA) had not been published yet, although the main findings were presented on November 16, 2019 at the American Heart Association (AHA) annual congress in Philadelphia, USA, available on the study’s website. Considering its importance for medical decision-making and the potential implications for nuclear cardiology, a few relevant concerns should be highlighted on the findings available so far:

The main objective of the ISCHEMIA study was to assess whether patients (P) with at least moderate ischemia on a functional examination would benefit from myocardial revascularization (coronary artery bypass grafting or percutaneous coronary intervention) added to optimal medical therapy). Were randomized 5,179 patients with stable CAD and myocardial ischemia documented by one of many different methods (myocardial perfusion scintigraphy, stress echocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, exercise testing not associated with cardiac imaging). These noninvasive methods were used to define the etiology of chest pain and for cardiovascular risk stratification, a management approach established in clinical practice that is not invalidated by the findings of the study. Prior knowledge indicates that patients with lower ischemic burden have a better prognosis than individuals with larger and more intense ischemia;

The ISCHEMIA trial demonstrated no benefit of myocardial revascularization (Invasive Group - IG) versus optimal medical therapy (OMT) to reduce the major outcomes of “death” and “acute myocardial infarction.” Despite the methodological differences, these results were somewhat similar to those of the COURAGE study. It is noteworthy that the mortality curves began to separate after two years of medical follow-up, apparently benefiting the IG and potential long-term implications, which justified the increased clinical follow-up of P, underway at the moment. Note that the IG had an improved quality of life assessment, reduced frequency of angina and lower use of specific medication compared to the OMT group;

The ISCHEMIA trial is one of the most relevant studies on stable CAD, with important messages for clinical practice. The validity of the results is emphasized for the population sample evaluated in the study and for the definitions of ischemia and its severity levels employed. However, for exclusion situations, such as P with left main disease, recent acute coronary syndrome, angioplasty in the previous 12 months, ejection fraction < 35% and progressive or unstable symptoms, prior knowledge remains unchanged. Both CAD and ischemic heart disease represent a broad spectrum of patients, with inherent heterogeneity and important prognostic implications (extensive evidence base in the literature and described in detail in the current guideline). Were excluded from the trial an impressive number of P that had at least moderate angina and ischemia in the absence of coronary obstructions, showing the diversity of the disease and the value of functional assessment;

The main question is whether the ISCHEMIA study has properly evaluated a significant number of P with moderate/severe ischemia, aiming to determine whether myocardial revascularization adds prognostic benefit to these patients, as documented by scintigraphy, which was not the exclusive method of documentation. There was the inclusion (randomization) of cases with nonexistent or mild ischemia (12% of the total randomized), which is surprising for a study that was initially intended to include only patients with moderate to severe ischemia. There was also a change in the criteria for inclusion of P with severe ischemia in the study, with a significant number based on the results of exercise testing, without imaging, a decision made after the study was in progress. From this change, the percentage of these P that would effectively have severe myocardial ischemia on scintigraphy is questioned;

Therefore, the Editorial Board of this guideline believes that the definitive analysis of the results will only be possible after the formal publication of the trial results.

3. The Application of Nuclear Medicine Techniques to Justify Financial Resources Available for Attending Cardiology Patients in Brazil

3.1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases are the main cause of death in Brazil, and they are responsible for 30% of deaths worldwide every year.1 They are responsible for approximately 8% of total healthcare costs in Brazil, a figure which has been increasingly annually, in parallel with population aging.1 Teich and Araújo estimated that in 2011, approximately 200,000 events associated with acute coronary syndromes occurred in Brazil, entailing a massive impact of 3.88 billion Brazilian reals, considering only hospital and indirect costs, associated with loss of productivity.2 Considering these findings, it has been demonstrated that (preventive) measures play a crucial role in reducing morbidity and mortality, and they should be a priority in national healthcare policy design, as they have profound additional impacts on reducing costs and maintaining productivity. Another significant point, however, which has contributed to reducing the outcome of “cardiovascular death” and to justifying expenses, involves the use of tools which make accurate diagnosis of a determined condition possible (?) and which aid and guide the conduct of physicians, based on these results. Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy (MPS) plays a significant role in justifying financial resources for attending patients with established or potential cardiovascular disease.

3.2. Cost-Effectiveness in Comparison with Cardiac Catheterization

One of the main fundaments of MPS is its good ability to identify low-risk patients, who do not require invasive intervention, in spite of established coronary disease, such as anatomical lesions on coronary angiography.3 Observational studies in the 1990’s have demonstrated that MPS was able to identify high- and low-risk groups, resulting in reduced costs for patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) and avoiding procedures that are not associated with improved patient health outcomes. A major prospective study carried out in the United States of America (USA) recruited 11,372 patients with stable angina, who were referred to either MPS or cardiac catheterization. Patients were adjusted by clinical risk, and the costs of direct cardiac catheterization (aggressive strategy) were compared to initial scintigraphy followed by selective catheterization in high-risk patients (conservative strategy). Although both strategies had similar adverse outcomes, such as cardiac death and non-fatal myocardial infarction, revascularization rates were higher (between 13% and 50%) in patients who underwent catheterization directly.4 This reflex of revascularizing anatomical lesions which do not determine ischemia led to unnecessary associated medical costs of around 5,000 dollars per patient in this study.4 Currently, the use of medical resources for conditions that do not have consequences for patients or that could be managed conservatively is known as “overtreatment.”5 The study of the impact of MPS on reducing costs has shown that its main function is to prevent patients who have low or moderate risks on single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) from being treated with unnecessary catheterizations and revascularizations. Similarly to this North American study, Underwood et al.6 have demonstrated that strategies which incorporate myocardial scintigraphy to evaluate patients with stable coronary diseases are both cheaper than and as effective as strategies involving invasive anatomical assessment.6 Cerci et al.7 evaluated the impact of diagnostic exams on patients with CAD in different scenarios within Brazil’s public Single Health System (SUS, acronym in Portuguese). The study’s most relevant finding is that, although non-invasive functional tests are the most frequently solicited exams for evaluating patients with suspected or known CAD, the majority of healthcare costs for these patients are related to procedures/invasive treatment. In other words, in the Brazilian context, the costs of diagnostic exams continue to be significantly lower than those of invasive and therapeutic procedures. In this manner, it seems logical to affirm that, if scintigraphy exams are made available to patients attended by the SUS, there will be a similar impact on the reduction of healthcare costs, which has been the case in the USA and some countries in Europe. Another relevant piece of data from this study refers to the fact that the majority of patients who were revascularized had not undergone tests to document ischemic burden; only anatomical diagnostic techniques had been applied.7

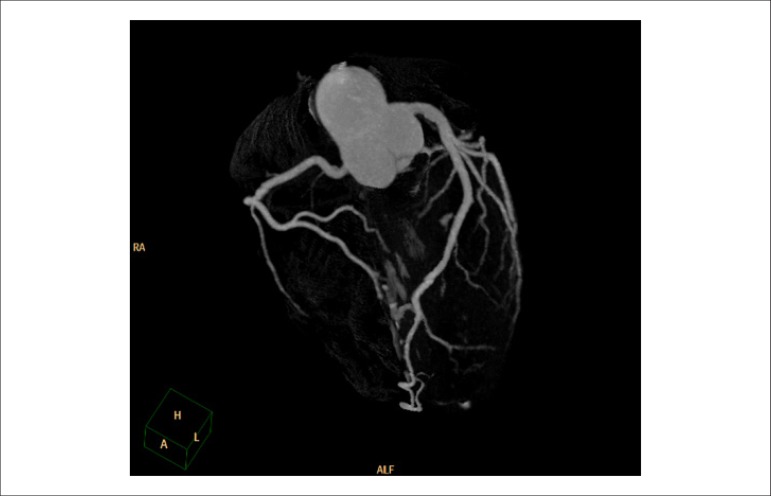

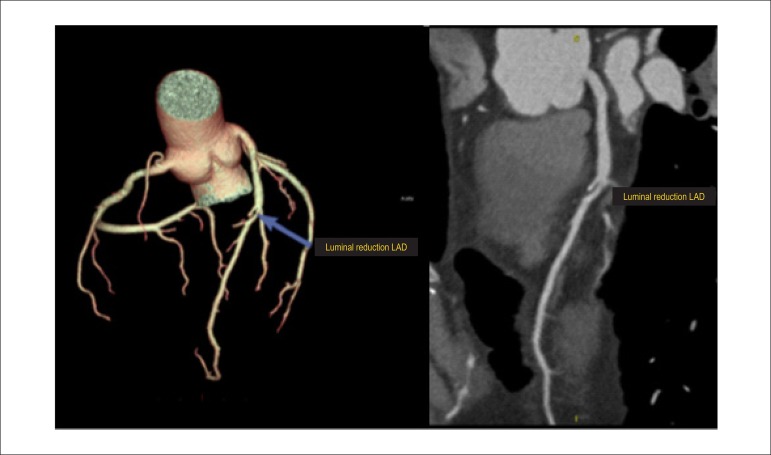

3.3. Cost-Effectiveness of Myocardial Perfusion Scintigraphy in Relation to Coronary Angiotomography

Angiotomography (angio-CT) of coronary arteries offers very accurate, non-invasive anatomical assessment, and it has proved to be an excellent technique for ruling out obstructive coronary disease in low- to intermediate-risk patients. Angio-CT, however, has presented results similar to those of cardiac catheterization in relation to triggering a higher number of myocardial revascularizations, which do not necessarily (means) reduced cardiovascular outcomes. In a recent meta-analysis comparing angio-CT to functional methods, no differences were observed regarding the outcomes of death or cardiac hospitalization, but there was a 29% reduction in the number of non-fatal infarctions. On the other hand, the use of this method was associated with 33% and 86% higher rates of invasive coronary angiography and myocardial revascularization, respectively. It is not known whether the reduction in non-fatal infarctions may be attributed to the higher number of revascularizations, which is (unlikely) considering in light of other studies on stable CAD, or to the higher use of statins and aspirin associated with the recognition of anatomical coronary lesions.8 With the objective of elucidating the role of angio-CT on cost-effectiveness of approaches to stable CAD in comparison with myocardial scintigraphy, the Randomized Evaluation of Patients With Stable Angina Comparing Diagnostic Examinations (RESCUE) study, which is being developed, is expected to compare these strategies in a prospective, randomized manner.9

The authors of a recent meta-analysis published by the American Heart Association (AHA)/Circulation, have reinforced 2 important aspects of cost-effectiveness:10

The importance of performing appropriate exams as a way of (ensuring) their cost-effectiveness, especially techniques like MPS.

The results of appropriate exams should effectively lead to appropriate decision making in clinical conduct and patient management.

4. Indications for Myocardial Perfusion Scintigraphy

Over the past years, different medical societies have published criteria for defining scenarios in which myocardial scintigraphy may be adequately utilized. In addition to traditional classification of recommendation and levels of evidence, more recent criteria on appropriate MPS exam referral have been suggested, dividing indications into appropriate, possibly appropriate, and rarely appropriate, resulting from the application of scores constructed based on clinical scenarios and specific methodologies.11 In this classification, indications with scores from 1 to 3 are considering rarely appropriate; 4 to 6, possibly appropriate; and 7 to 9, appropriate. Published documents are based on evidence from American and European Guidelines, as well as the recently published Brazilian Guidelines on stable coronary disease.12-15

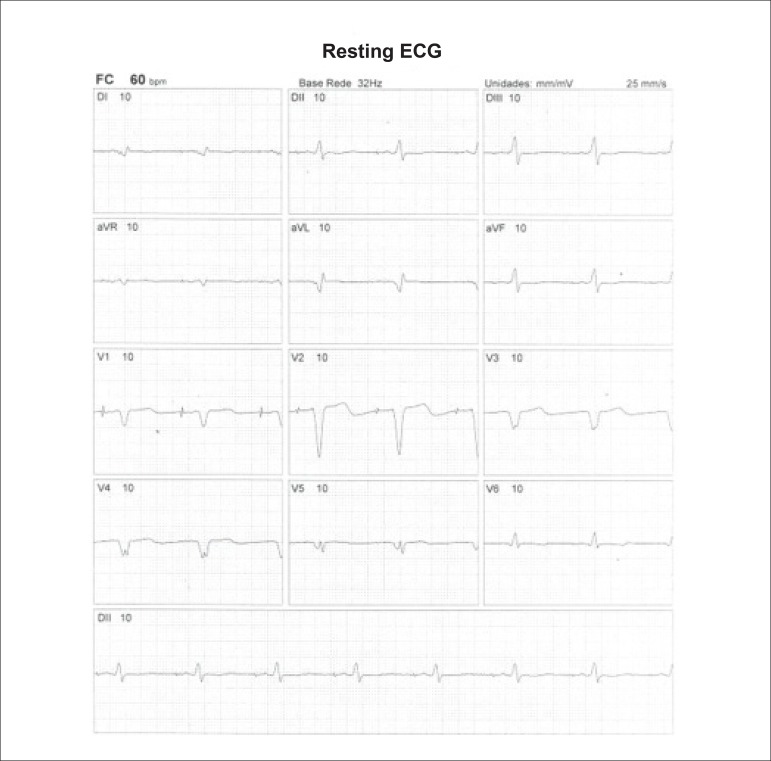

Regardless of classification type, there is consensus that symptomatic patients with intermediate risks of ischemic heart disease are the ones who most benefit from MPS in terms of diagnostic and prognostic evaluation. The exam should preferably be performed in association with physical exercise in patients with sufficient physical and clinical conditions (estimated ability for activities of daily living with metabolic expenditure greater than 5 METs), in order to measure their functional capacity, hemodynamic responses (heart rate and blood pressure behavior), stress-induced arrhythmias, and other responses. It is recommended that patients with complete left bundle branch block, regardless of functional ability, undergo MPS under pharmacological stress (dipyridamole or adenosine). In the same manner, regardless of pretest probability of ischemic heart disease, patients with low functional ability or uninterpretable electrocardiogram (ECG) are indicated to undergo MPS. On the other hand, patients with low probability of ischemic heart disease, higher functional ability, and interpretable ECG are not indicated for MPS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Indication criteria for myocardial perfusion scintigraphy in symptomatic patients

| Assessment of patients with non-acute chest pain or ischemic equivalent | Score |

|---|---|

| Low pretest probability of CAD, with interpretable resting ECG and ability to exercise | 3 |

| Low pretest probability of CAD, with uninterpretable resting ECG or inability to exercise | 7 |

| Intermediate pretest probability of CAD, with interpretable resting ECG and ability to exercise | 7 |

| Intermediate pretest probability of CAD, with uninterpretable resting ECG or inability to exercise | 9 |

| High pretest probability of CAD, regardless of interpretable resting ECG and ability to exercise | 8 |

ACS: acute coronary syndrome; CAD: coronary artery disease; ECG: 12-lead electrocardiogram.

In patients with heart failure (HF) and left ventricular systolic dysfunction or recent-onset atrial fibrillation (AF), ventricular tachycardia (VT) or syncope, the indication for MPS is appropriate or possibly appropriate, unless the patient in question is low risk or has low pretest probability. Asymptomatic patients with no history of ischemic heart disease and without abnormal exercise testing (ET) generally do not benefit from undergoing MPS. In specific situations, in patients with high calcium scores (greater than or equal to 400), diabetes, chronic renal insufficiency, or a prevalent family history of ischemic heart disease, performing MPS may aggregate value to the medical decision-making process, with satisfactory cost-effectiveness. Asymptomatic patients with abnormal stress ECG who are re-stratified with the use of prognostic scores, such as the Duke score, may also benefit from complementary investigation via MPS, especially if their risk scores are intermediate or high (Table 3). Diverse examples of clinical situations cited in Table 3 may also be found in the section on integration of diagnostic modalities.

Table 3.

Indication criteria for myocardial perfusion scintigraphy in asymptomatic patients and/or patients with prior exams

| Asymptomatic patients - detection of CAD/risk stratification | Score |

|---|---|

| Low risk (ATP III criteria) | 1 |

| Intermediate risk (ATP III criteria) - interpretable ECG | 3 |

| Intermediate risk (ATP III criteria) - uninterpretable ECG | 5 |

| High risk (ATP III criteria) | 7 |

| High risk and calcium score (Agatston) between 100 and 400 | 7 |

| Calcium score (Agatston) > 400 | 7 |

| Low-risk Duke score (> +5) | 2 |

| Intermediate-risk Duke score (between -11 and + 5) | 7 |

| High-risk Duke score (< -11) | 8 |

Agatston: score that defines the presence and quantity of calcium in coronary arteries, characterizing atherosclerosis; ATP III: Adult Treatment Panel, from the program for detection, evaluation, and treatment of high cholesterol in adults; CAD: coronary artery disease.

When patients have established ischemic heart disease and are asymptomatic, early myocardial perfusion studies with radiopharmaceuticals should be avoided following percutaneous coronary intervention and/or myocardial revascularization surgery procedures. In the event of percutaneous coronary intervention and myocardial revascularization surgery, the application of MPS has been observed to have a favorable cost-benefit ratio for follow up after more than 2 and 5 years, respectively, even in asymptomatic patients. Symptomatic patients with specific clinical conditions (or equivalent manifestations) may benefit from the exam before this period (Table 4).

Table 4.

Indication criteria for myocardial perfusion scintigraphy in patients who have undergone revascularization procedures (CABG or PCI)

| Previous percutaneous revascularization or surgical procedures | Score |

|---|---|

| Symptomatic | 8 |

| Asymptomatic, CABG less than 5 years prior | 5 |

| Asymptomatic, CABG 5 or more years prior | 7 |

| Asymptomatic, percutaneous revascularization less than 2 years prior | 3 |

| Asymptomatic, percutaneous revascularization 2 or more years prior | 6 |

CABG: myocardial revascularization surgery; PCI percutaneous coronary intervention.

For patients with previous exams who manifest new symptoms or who require assessment of the repercussion of diagnosed intermediate lesions and characterization of arteries with obstructive lesions “responsible” for a larger myocardial area at risk, as well as patients with multivascular diseases, the indication for MPS is classified as appropriate or possibly appropriate. In patients with established coronary disease and worsening symptoms, MPS may aid in quantifying ischemic burden (extent and intensity of defects) and in determining medical management. In clinically stable patients with previous exams performed more than 2 years prior, MPS may be appropriate (Table 5).

Table 5.

Indication criteria for myocardial perfusion scintigraphy for risk stratification and prognostic assessment of patients with proven stable coronary artery disease and/or prior exams

| Asymptomatic patients or patients with stable symptoms - previously "normal" stress imaging exams | Score |

|---|---|

| Intermediate/high risk (ATP III) - stress imaging exam ≥ 2 years prior | 6 |

| Asymptomatic patients or patients with stable symptoms - CCA or abnormal imaging exams, without prior CABG | |

| Previously "unclear," "contradictory," or "borderline" non-invasive assessment - obstructive CAD as initial concern | 8 |

| New, recent, or progressive symptoms | |

| Normal CCA or normal stress imaging exam | 6 |

| Coronary cineangiography (invasive or non-invasive) | |

| Coronary stenosis or anatomical abnormality whose significance is unclear | 9 |

ACS: acute coronary syndrome; ATP III: Adult Treatment Panel, from the program for detection, evaluation, and treatment of high cholesterol in adults; CAD: coronary artery disease; CCA: coronary cineangiography; CABG: myocardial revascularization surgery.

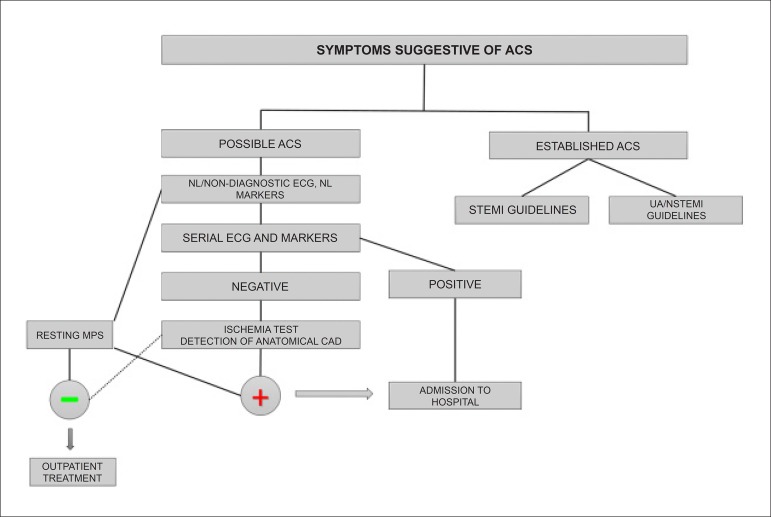

In patients who present acute chest pain, with clinical suspicion of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), normal or uninterpretable ECG (old left bundle branch block or pacemaker) and normal biomarkers, resting myocardial scintigraphy may exclude acute cardiovascular events with a high degree of safety (high negative predictive value [NPV]), allowing patients to be discharged from the emergency room. If the exam is normal, investigation may continue with outpatient tests involving physical or pharmacological stress, whether associated or non-associated with non-invasive imaging, and even anatomical assessment via coronary angio-CT, in specific conditions. For patients with ACS who are clinically stable, with neither recurring chest pain nor HF, and who have not undergone any invasive exam, MPS is useful for detecting presence and extent of myocardial ischemia (Table 6).

Table 6.

Indication criteria for myocardial perfusion scintigraphy in patients with acute chest pain or post-acute coronary syndrome

| Assessment of patients with acute chest pain | Score |

|---|---|

| Resting image only | |

| Possible ACS - ECG without ischemic alterations or LBBB or pacemaker; low-risk TIMI score; borderline, minimally elevated, or negative troponin | 8 |

| Possible ACS - ECG without ischemic alterations or LBBB or pacemaker; high-risk TIMI score; borderline, minimally elevated, or negative troponin | 7 / 8 |

| Possible ACS - ECG without ischemic alterations or LBBB or pacemaker; negative initial troponin. Recent (up to 2 hours) or evolving chest pain | 7 |

| Assessment of post-ACS patients (infarction with or without elevated ST segment) | |

| Stable, post-AMI patients, with ST segment elevation, for assessment of ischemia; cardiac catheterization not performed | 8 |

| Stable, post-AMI patients, without ST segment elevation, for assessment of ischemia; cardiac catheterization not performed | 9 |

ACS: acute coronary syndrome; AMI: acute myocardial infarction; CAD: coronary artery disease; ECG: 12-lead electrocardiogram; LBBB: left bundle branch block.

Indications for MPS to assess pre-operative risk of non-cardiac surgeries and vascular surgeries have also been recently revised.16 Patients who will undergo low-risk surgeries do not need to undergo MPS. If the surgery is not low-risk, functional capacity is the factor that determines whether MPS will be necessary. In patients with functional capacity estimated at greater than or equal to 4 METs, without cardiac symptoms, regardless of clinical or surgical risk, non-invasive assessment of myocardial ischemia is generally not recommended. However, for patients with low functional capacity and elevated clinical/surgical risks, there is an indication to perform MPS under pharmacological stress. The following are considered clinical risks: history of ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure (CHF), cerebrovascular disease, diabetes mellitus (DM), and renal insufficiency (creatinine > 2.0 mg/dl). In the absence of these risk factors, regardless of functional capacity, surgery may be performed without complementary functional exams (Table 7).

Table 7.

Indication criteria for myocardial perfusion scintigraphy for pre-operative assessment of non-cardiac surgeries

| Pre-operative assessment of non-cardiac surgeries | Score |

|---|---|

| Low-risk surgery | 1 |

| Intermediate-risk surgery or vascular surgery Functional capacity greater than or equal to 4 METs |

1 |

| Intermediate-risk surgery or vascular surgery Functional capacity unknown or less than 4 METs No clinical risk factors |

1 |

| Intermediate-risk surgery Functional capacity unknown or less than 4 METs One or more clinical risk factors |

7 |

| Vascular surgery Functional capacity unknown or less than 4 METs One or more clinical risk factors |

8 |

MET: metabolic equivalent.

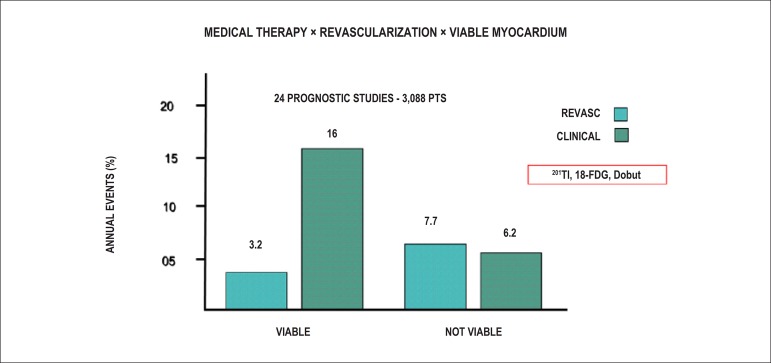

In patients with accentuated left ventricular dysfunction who are eligible for myocardial revascularization, assessment of myocardial viability may aid selection of patients who will benefit from this treatment (Table 8).

Table 8.

Indication criteria for myocardial perfusion scintigraphy for assessment of myocardial viability

| Assessment of myocardial viability | Score |

|---|---|

| Accentuated left ventricular dysfunction | 9 |

| Eligible for myocardial revascularization | 9 |

MPS is, therefore, an appropriate indication in diverse clinical manifestations of ischemic heart disease, from acute manifestations in the emergency room to diagnostic investigation of stable patients, aiding in therapeutic decision making through various tools which make it possible to define disease severity, as well as in pre-operative assessment in specific situations and in defining the benefits of revascularization for patients with significant myocardial viability. It is worth noting that, for diagnostic investigation, patients with intermediate probability of ischemic heart disease are those who most benefit from MPS and that it is rarely appropriate in patients with low probability.

5. Myocardial Perfusion Scintigraphy Methods - types of Cardiovascular Stress

5.1. Radiopharmaceuticals Used to Perform Myocardial Perfusion Scintigraphy

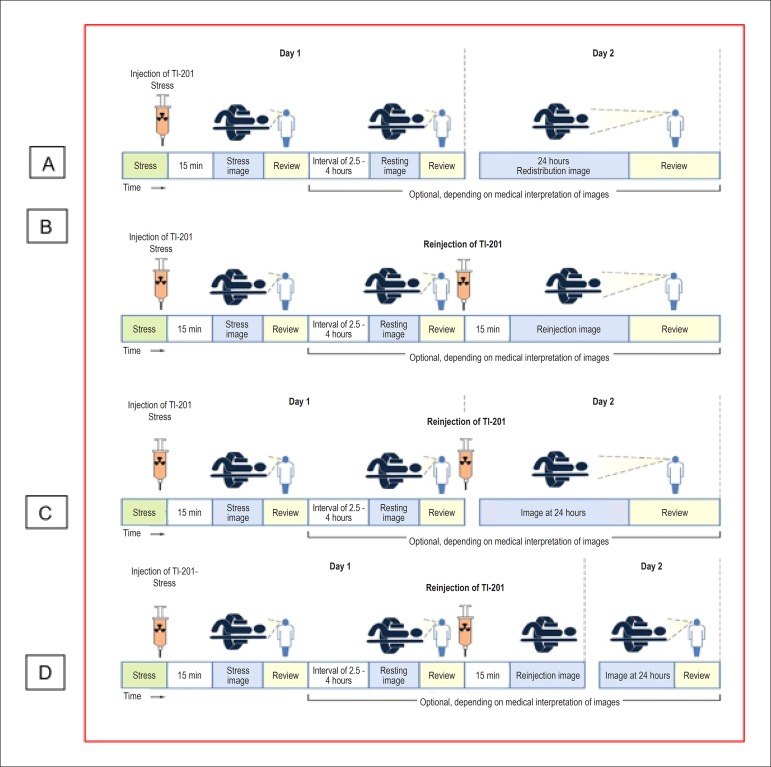

In Brazil, the main radiopharmaceuticals available for obtaining images of the myocardium are thallium-201 (201Tl) and those labeled with technetium-99m (99mTc), which mainly include 2-methoxy-isobutyl-isonitrile, known as Sestamibi (or MIBI), and tetrofosmin. Given that these are the most widely used, the specific methods used for acquiring images with them will be presented.

Thallium-201 or 201Tl 17 is a monovalent cation with biological properties analogous to those of potassium. It is both intracellular and absent in scar tissue, and it is thus designated for differentiating ischemic myocardium from fibrosis. It has a physical half-life of 73 hours, and it decays by electron capture to mercury-201 (201Hg), and the photons emitted for imaging are primarily x-rays (of 201Hg itself) between 68 and 80 kilo-electron volts (keV), in addition to lower quantities of gamma radiation in the energy range of 135 keV and 166 KeV. Upon intravenous injection, initial myocardial uptake is proportional to regional blood flow, depending on the integrity of the cellular membrane. It penetrates the cellular membrane via active transport, involving energy expenditure (Na+/K+ATPase system), with a high first-pass extraction fraction in the myocardium (the proportion of 201Tl which is extracted from blood and absorbed by myocytes), of around 70% to 85%.

Maximum concentration of thallium-201 in the myocardium occurs approximately 5 minutes after injection, which is generally administered during peak exercise or clinical and/or electrocardiographic alterations triggered during an ET or a pharmacological test. It presents rapid disappearance or clearance from the intravascular compartment. Following initial distribution of the radioisotope throughout the myocardium, related to blood flow, the phenomenon of redistribution begins 10 to 15 minutes after injection. This is dependent on clearance or washout of thallium-201 from the myocardium, which no longer depends on blood flow but rather on the concentration gradient between myocytes and blood levels. Redistribution of thallium-201 is quicker in normal myocardium than in ischemic myocardium, resulting in different activities in these tissues (differential “washout”).

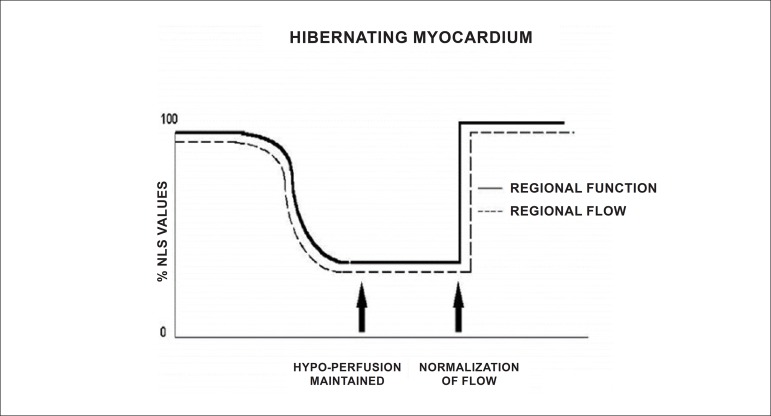

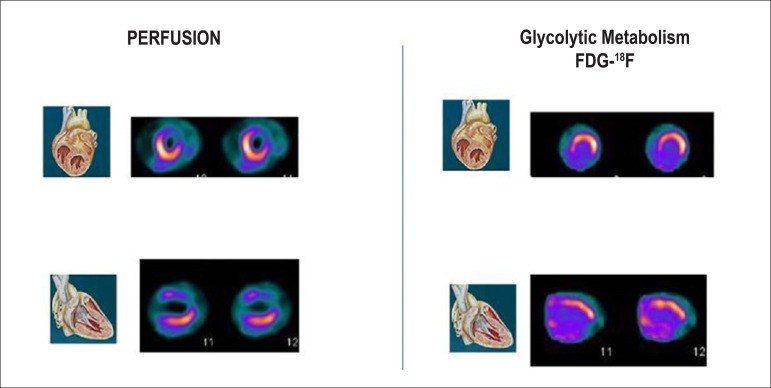

Due to the characteristics described and the ability to evaluate the integrity of the cellular membrane, thallium-201 has the additional property of studying myocardial viability, predominantly related to hibernating myocardium (Figure 1).18-20 This represents the condition of resting left ventricular dysfunction, resulting from chronic hypoperfusion in myocardial regions where, although the myocytes have remained viable (alive), they have chronically depressed contractile function. Hibernation may also be seen as a “flow-contraction” agreement process, where metabolism remains dependent on residual myocardial flow in a manner sufficient for minimum substrate supply and inhibitory substance removal. Therefore, the condition of hibernation, notwithstanding reduced resting coronary flow, is not necessarily associated with the presence of chronic ischemia, given that oxygen supply and consumption ratio may be preserved.21,22

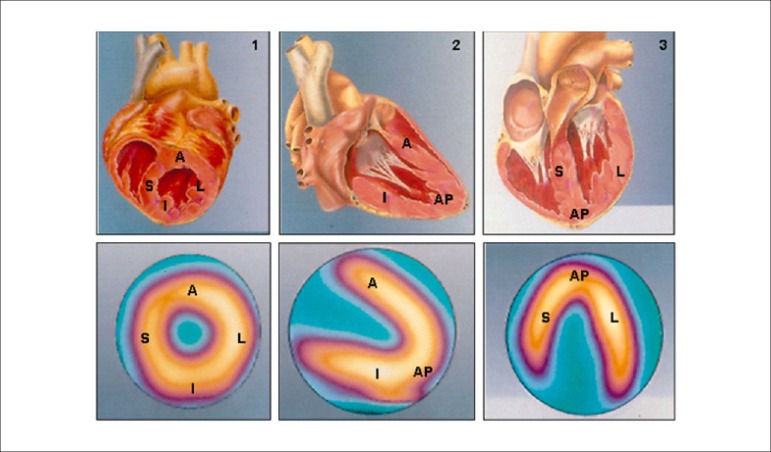

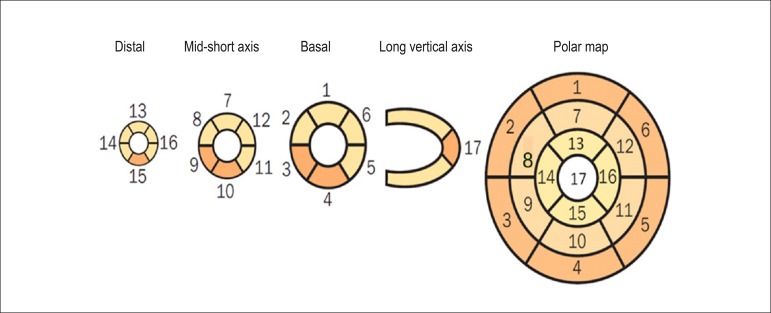

Figure 1.

Hibernation represented as persistent decrease of blood flow and contractile function. Recovery of function is immediate following restoration of coronary flow. %: percent values; NLS: normals.

Source: Adapted from Dilszian.277

Technetium-99m-labeled SESTAMIBI or MIBI (MIBI- 99mTc):23,24 The most frequently used marker for myocardial perfusion studies, is 2-methoxy-isobutyl-isonitrile, a stable, lipophilic, cationic compound belonging to the isonitrile family, which has the property of crossing cellular (sarcolemmal) membranes and binding to myocyte mitochondria through the mechanism of passive diffusion, depending on the electrochemical transmembrane gradient. It therefore involves no energy expenditure. It has a lower first-pass extraction fraction in the myocardium than thallium-201, of approximately 60%.25

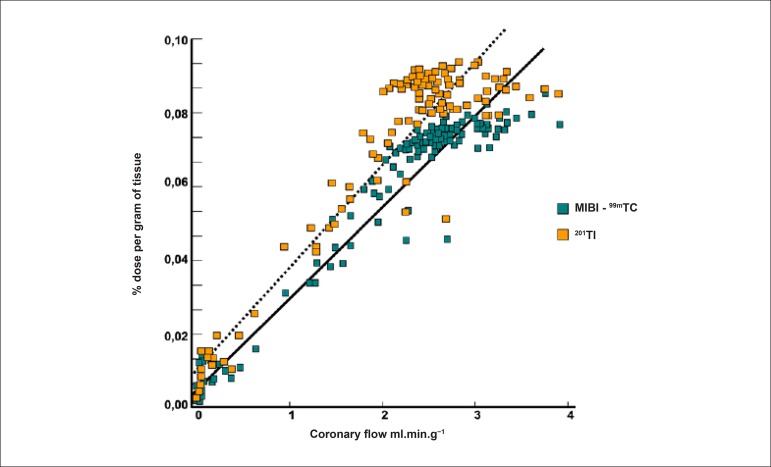

It does not expressively present the phenomenon of redistribution, largely remaining retained within mitochondria. This property makes it necessary to deliver 2 separate injections of the radiopharmaceutical, 1 during the resting and 1 during the stress phase. This may be done either on the same day or on different days. As MIBI is not radioactive, it must be labeled with technetium-99m (99mTc), which has a physical half-life of 6 hours and emits gamma photons in the energy range of 140 keV (photopeak). Similarly to thallium-201, initial myocardial uptake is proportional to regional blood flow, depending on the integrity of the cellular membrane. In this manner, a linear relationship is observed between the intravenous dose per gram of myocardium and blood flow per minute (Figure 2), starting at minimal flow ranges of approximately 2.0 to 2.5 milliliters per gram.minute-1, values normally found in maximum exercise testings. When very high coronary flow are reached, generally over 3.0 mililiters per gram.minute -1, the linear relationship between this variable and myocardial uptake is lost, with decreased blood extraction of the radiopharmaceutical, in a phenomenon known as “roll off”.26-28 Nonetheless, owing to higher energy emission (higher photopeak), measured in keV, it presents higher quality images, in comparison with thallium-201. Finally, the elimination of MIBI-99mTc takes place through the hepatobiliary system, whereas elimination of thallium-201 is mainly achieved through the renal system. Regarding other isonitriles approved by the FDA for assessment of obstructive CAD, only tetrofosmin, whose properties are similar to those of MIBI-99mTc, has been made available for clinical use.

Figure 2.

Linear association between intravenous dose per gram of myocardium and blood flow per minute, using the radiopharmaceuticals 201Tl and MIBI-99mTc. Once coronary flow exceeds 2.5 ml.min.g-1, a loss of linear relationship is observed (phenomenon of “roll off”).

Source: Adapted from Berman DS.116

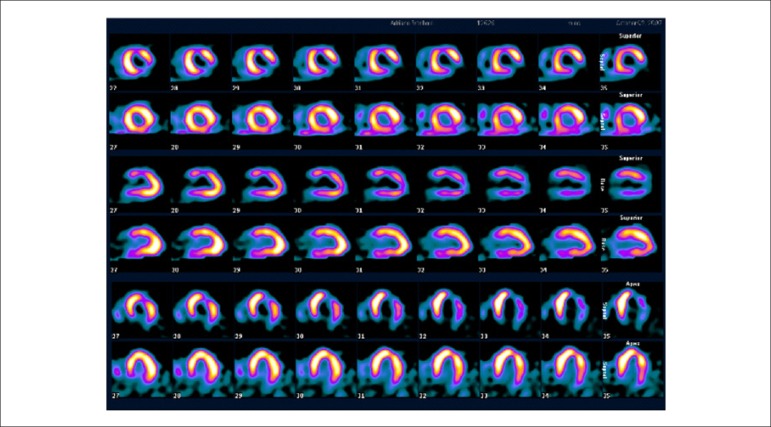

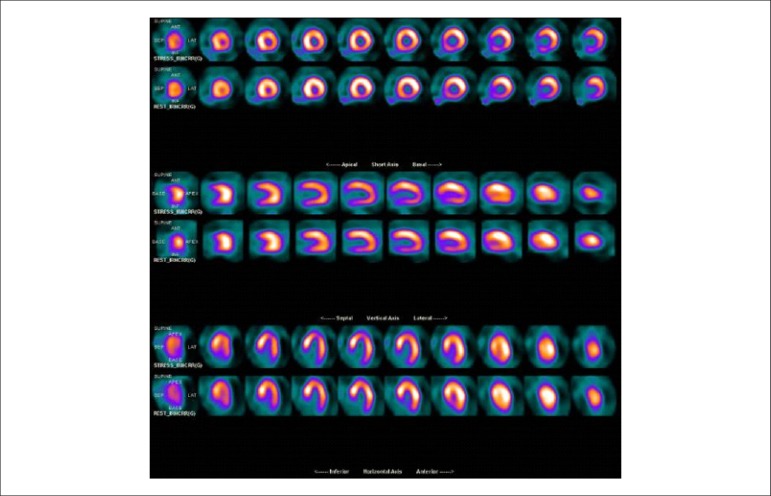

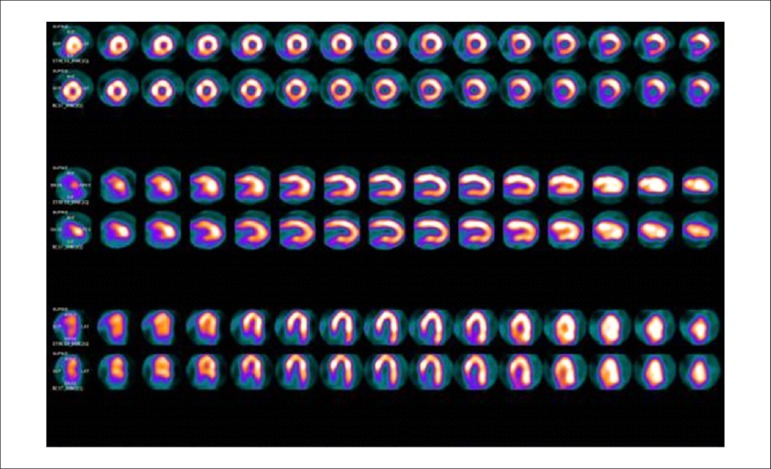

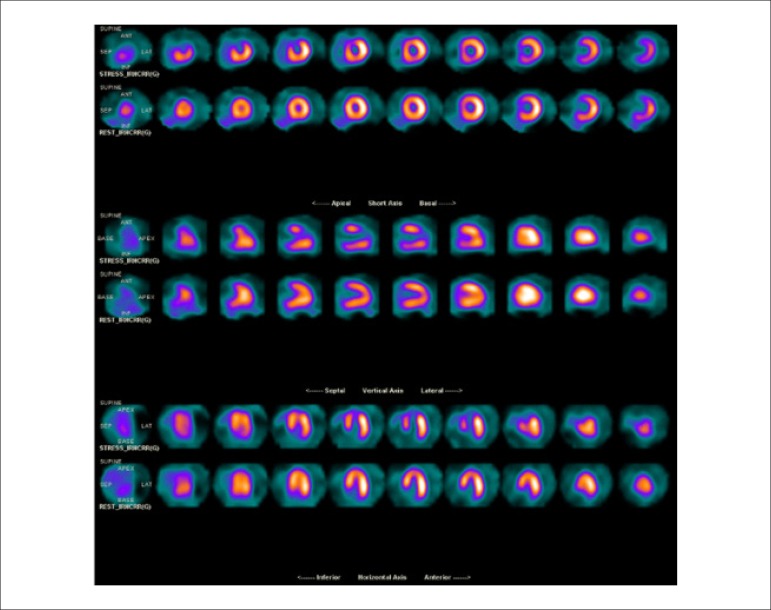

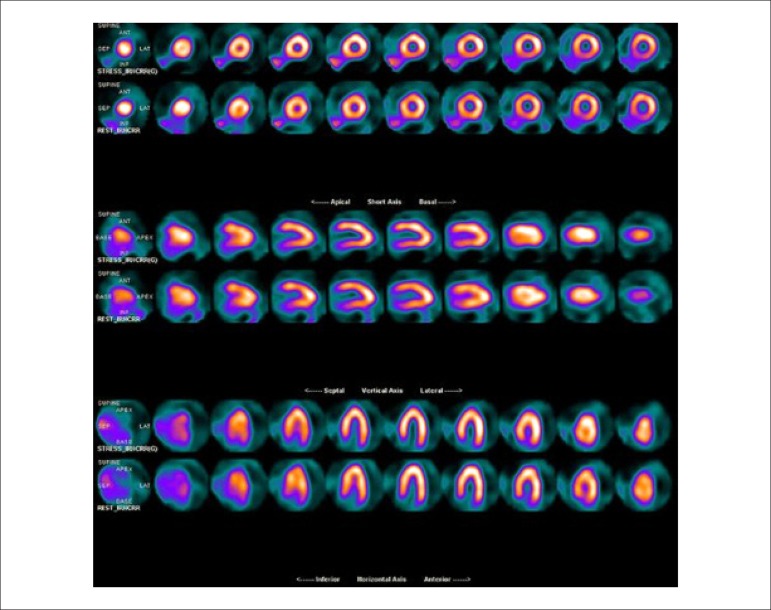

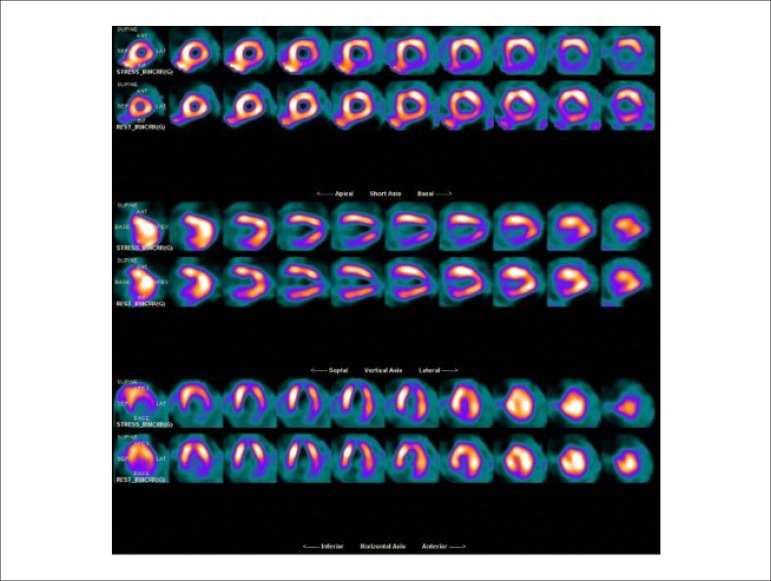

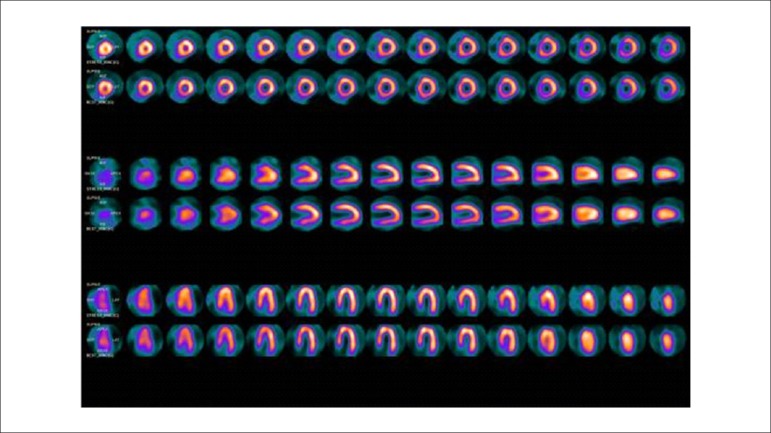

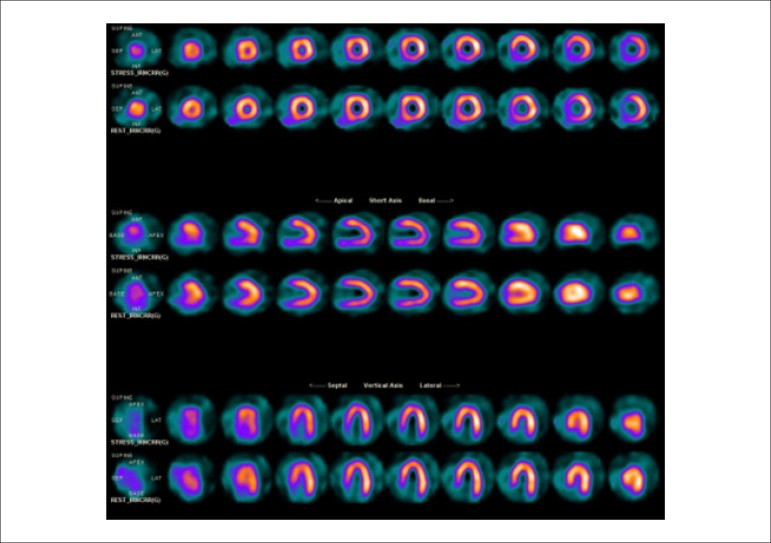

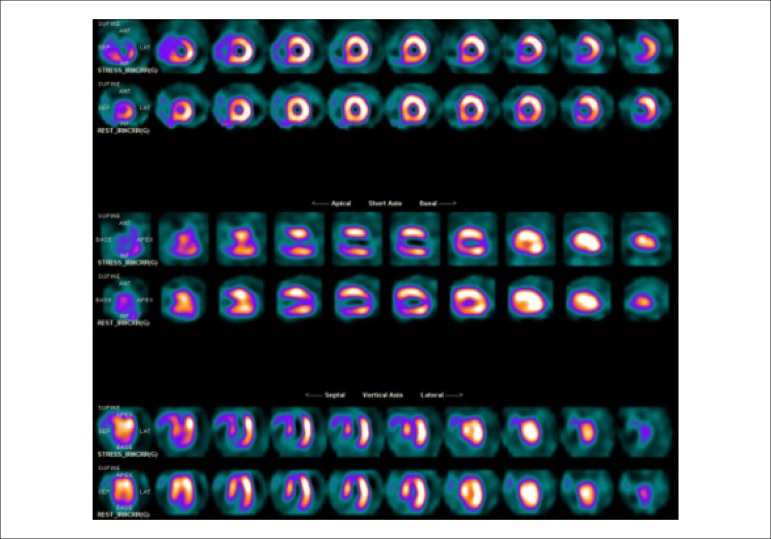

5.2. Myocardial Perfusion Scintigraphy with Tomography Imaging (SPECT)

Technological evolution of computerized systems has made it possible to divide the myocardium of the left ventricle (LV) into tomographic slices measuring only a few millimeters. In conventional gamma cameras (with iodide sodium crystals) the size of a pixel (the smallest component of a digital image) is 6.4 mm, and in CZT (cadmium zinc telluride semiconductors) technology it is 4 mm, representing related cross sections and, consequently, the method’s spatial resolution.29-31 The resulting images facilitate the separation of nearby regions, improving contrast resolution and allowing for better detection of differences in concentrations of radioactivity in the myocardium. The SPECT technique also allows for detection of ischemic regions, even those that are small in size, i.e., approximately 2% of LV mass, in tissue with relatively normal tracer concentration.

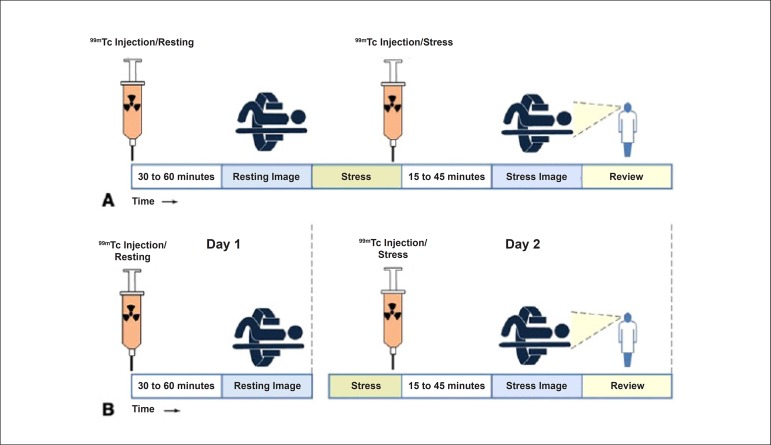

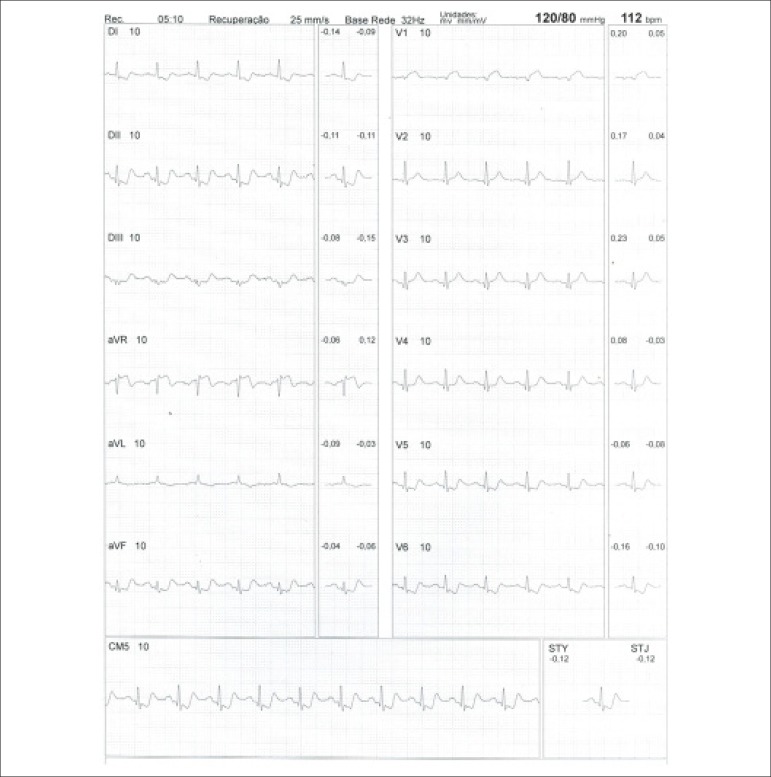

Protocols: The preferred means of obtaining perfusion images of the myocardium and LV function with tracers labeled with technetium-99m (99mTc) is known as the “1-day protocol” (Figure 3A), made up of 2 stages, (resting-stress or stress-resting). During the first step, the injected dose of MIBI-99mTc, measured in millicuries (mCi) or megabecquerels (mBq), is three times lower than the dose administered during the second phase, thus avoiding the residual activity effect or “shining through” phenomenon. Another option is the “2-day protocol” (Figure 3B), where in each phase is performed on a separate day. In this case, similar doses and acquisition parameters are used. It is important to emphasize that, in situations where stress images are taken before resting ones, even if the perfusion images are normal, it is nevertheless important to obtain resting images, except in specific cases, given that analysis of LV function in both situations may provide relevant information, including the possibility of detecting patients with homogenous tracer distribution due to balanced severe coronary diseases. Furthermore, the detection of transient LV dilatation may also be useful in this case, and this requires that both phases be performed. However, in asymptomatic patients who have intermediate/low risks and no clinical evidence of CAD, who have undergone the stress phase as the initial MPS stage and whose perfusion images are normal, it is possible to dispense with the resting phase, in what is known as the “stress only protocol.” In this situation, recent studies have provided evidence that the test’s prognostic value is maintained and that diagnostic ability is similar to the costs of high sensitivity. Furthermore, the patient receives a lower dose of radioactive activity, and total exam time is reduced.32,33

Figure 3.

Perfusion image acquisition and myocardial function with the radiopharmaceuticals sestamibi (MIBI) or tetrofosmin labeled with technetium-99m or 99mTc: “one-day” protocol (A) and “two-day” protocol (B). The legends “99mTc Injection/Resting” and “99mTc Injection/Stress” represent administration of the radiopharmaceutical MIBI-99mTc during both stages, with dosage measured in millicuries (mCi), established in accordance with equipment and acquisition model used, as well as patient weight. In Protocol A, the stress dose is 3 times higher than the resting dose; in Protocol B, the resting and stress doses are similar, considering an interval of 24 hours between image acquisition.

5.3. Myocardial Perfusion Scintigraphy with Tomographic Images Synchronized with Electrocardiogram (Gated-SPECT)34-41

Cardiac images should be acquired synchronized with patient ECG, allowing for additional analysis of ventricular function, simultaneous with myocardial perfusion evaluation. This information adds data to the medical decision-making process within known incremental prognostic values, and it improves test accuracy, especially regarding specificity values. Considering this aspect, in situations where there are doubts between persistent perfusion defects and/or artifacts (due to breast or diaphragmatic attenuation), analysis of ventricular wall motility and thickness may contribute to differentiating these two causes. When apparent reduced relative uptake of a radiopharmaceutical is due to an artifact, the motility and systolic thickness of this wall are normal.

The estimated results of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) that are conventionally considered normal vary according to technique and methodology employed. With the Gated-SPECT technique, this value is ≥ 50% for both sexes; there are few references with differentiated values for men and women, in addition to different established limits of normality. Due to specific aspects related to methodologies used to calculate LVEF, values found in individuals who are shorter and individuals with smaller ventricular cavities and/or hypertrophic ventricles, especially in women, may be overestimated, at times exceeding values of 75% to 80%.

Calculations of LVEF and ventricular volumes obtained by Gated-SPECT may be utilized for prognostic stratification. LVEF < 45% and end systolic volume (ESV) > 70 ml are associated with increased risks of cardiac death.42,43 This analysis may be carried out either while resting or under stress; it should preferably be done during both steps, however, considering the possibility of detecting transient LV dysfunctions induced by physical exercise or pharmacological stress.

Cardiac arrhythmias pose difficulties to the acquisition of ECG-synchronized images and may significantly influence the results obtained for ejection fraction and produce artifacts in myocardial perfusion images. There is a technically defined time window for RR interval variation, generally around 20%, after which point heartbeats are rejected. This situation means that if there is an arrhythmia which produces variations between RR intervals above these established limits, such as persistent AF, the corresponding data from that specific cardiac cycle will be rejected, and there will consequently be lower counting statistics. In these cases, images should be acquired without ECG synchronization in order to avoid the occurrence of artifacts.

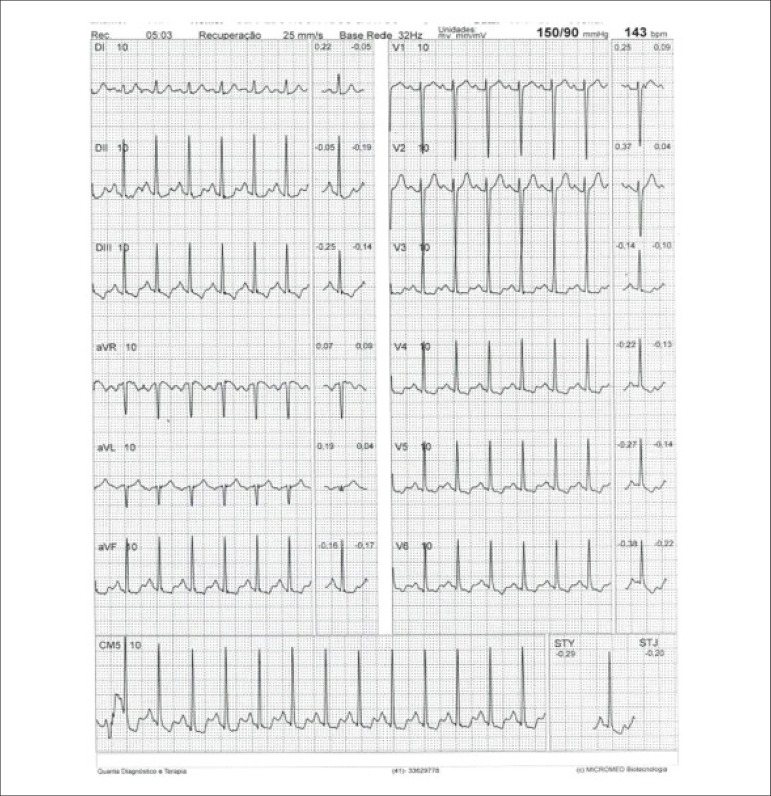

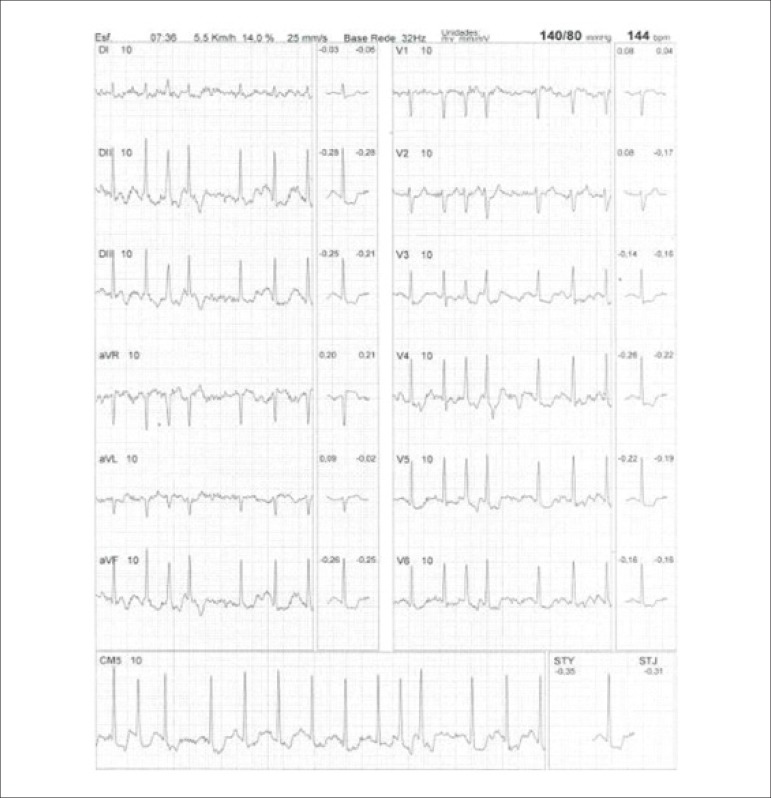

5.4. Cardiovascular Stress

The basic principle of using cardiovascular stress associated with myocardial perfusion images consists of creating heterogeneity in blood flow between vascular territories irrigated by normal coronary arteries with significant obstructive stenoses.44,45 The use of myocardial perfusion agents makes it possible to visualize this heterogeneity in regional blood flow. In practice, of all existing cardiovascular stressors, only ET and pharmacological tests have been used.

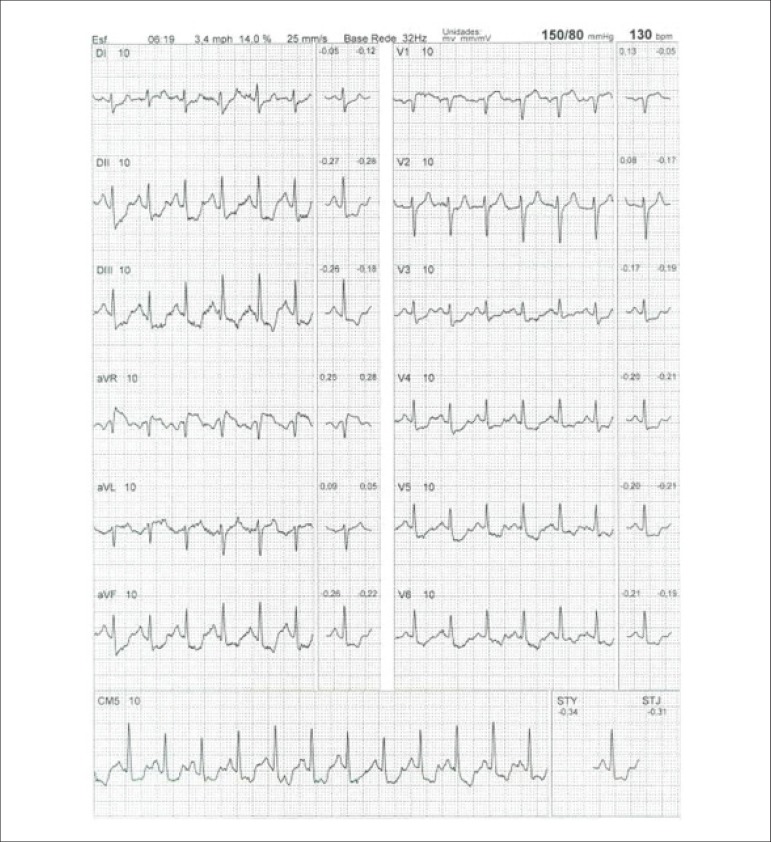

Both stress modalities, physical exercise and pharmacological vasodilation, have similar sensitivity and specificity for the detection of CAD via analysis of perfusion images.46-48

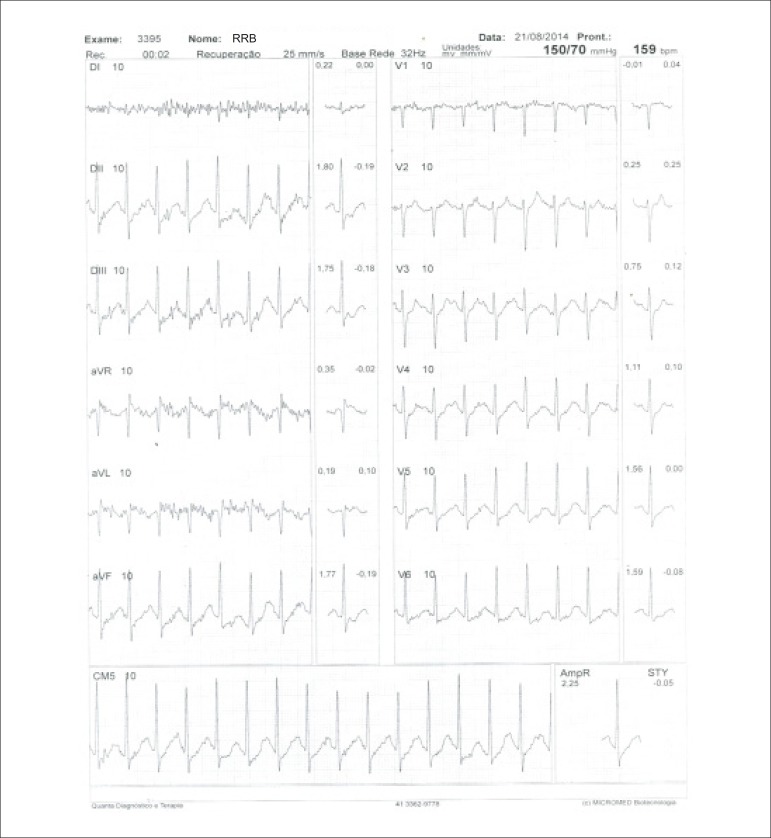

Physical stress: ET is the associated method of choice for diagnostic and prognostic values, which have already been established in conformity with clinical, hemodynamic, and electrocardiographic variables obtained during exercise, which add incremental data to myocardial perfusion study. Stress tests have a higher chance of revealing abnormalities in patients with more severe and extensive obstructive arterial disease. Chest pain and/or decreased systolic blood pressure (SBP) during low levels of exercise are highly important findings that are associated with adverse prognoses and multivessel coronary disease. Other markers of unfavorable prognosis include high-magnitude ST segment depression, with a horizontal or downsloping aspect, which may appear early during low workloads or be characterized by late recovery after stress has ceased, present in multiple leads, among others (Table 9).

Table 9.

Exercise testing parameters associated with unfavorable prognosis and multivessel coronary disease.

| • ECG: |

| - ST-segment depression ≥ 2 mm, with descending morphology and early appearance (metabolic load < 5 - 6 METs), involving multiple leads, usually lasting for ≥ 5 minutes of recovery |

| - Exercise-induced ST-segment elevations |

| - Reproducible, symptomatic, or sustained ventricular tachycardia (> 30 s) |

| • Metabolic load < 5 - 6 METs* |

| • Chronotropic incompetence |

| • Systolic blood pressure: inability to reach values ≥ 120 mmHg, or sustained decrease ≥ 10 mmHg, or fall below resting values during progressive exercise |

| • Symptoms: angina pectoris when performing a lower workload , generally during the beginning of exercise, when conventional protocols are applied |

ECG: electrocardiogram; MET: metabolic equivalent. (*1 MET = oxygen consumption in supine resting conditions, equivalent to 3.5 mL.kg-1.min-1)

Some studies have incorporated stress test variables into diagnostic and prognostic scores.49 The most widely used in our context is the Duke prognostic score. Using Cox’s regression analysis, Mark DB et al. proposed50 and validated51 this score for use with the exercise treadmill test and the Bruce protocol. It is calculated by the following formula:

or

The angina index has a value of 0 (zero) if there are no symptoms during exercise, 1 (one) if non-limiting chest pain occurs, and 2 (two) if the pain is impeditive (growing intensity) as exercise proceeds. In accordance with the results of the regression equation, patients are classified as follows:

High-risk group: patients with scores ≤ -11, with an annual cardiovascular mortality rate ≥ 5%.

-

Low-risk group: patients with scores ≥ 5, with an annual cardiovascular mortality rate < 1%. In clinical practice, when patients are considered high-risk, this reinforces a priori the indication for invasive study with the aim of managing and directing medical treatment, be it interventional or not, while always taking the possibility of improving morbimortality and quality of life into account. In patients with intermediates results, i.e., scores between > -11 and < +5, in order to reclassify risk, complementary exams associated with imaging, such as the following, may be required:

- Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy (MPS) with ET or vasodilators.

- Vasodilator stress cardiac magnetic resonance (technique associated with inability to exercise).

- Doppler echocardiogram under stress or specific conditions.

- Computerized angiotomography of coronary arteries.

Finally, in patients considered low-risk, medical management is related to prevention measures. On the other hand, based on a growing base of evidence, these methods,52 especially MPS, have become of paramount importance for quantifying ischemic area, even in patients who are considered high-risk, with the aim of assisting and directing the medical approach to be adopted,53-58 notwithstanding the unavailability of information from randomized clinical trials such as the “Ischemia Study,” which will be able to assist in better management of patients with extensive areas of the myocardium at risk.59

Furthermore, emphasis given to exercise as the primary stress-producing agent of choice within the cardiovascular system has become clear, given that it is the most physiological method for triggering myocardial ischemia, based on sympathetic stimulation and the increase in the main determinants of myocardial oxygen consumption (MVO2), such as HR, blood pressure, and myocardial contractility. Likewise, exercise leads to coronary vasodilation through biochemical mechanisms, resulting in increased blood flow to the myocardium and greater oxygen supply, thus meeting the necessary demands imposed during the application of extreme effort. This ability to increase coronary blood flow, which reaches three to four times baseline values during peak exercise, in the absence of significant obstructive coronary lesions, conceptually represents the phenomenon known as “coronary reserve,” considered the main characteristic of MPS with radiopharmaceuticals. Moreover, with respect to the limitations and contraindications of this methodology,60 joint analysis of both stress test and cardiac imaging exams will play a fundamental role in the medical decision-making process, albeit in view of previous clinical information or pretest probability of obstructive CAD.

With relation to the main methodological aspects, the following stand out:

Prior venous access in an arm, in a “Y” shape (separate routes), for radiopharmaceutical injection during peak exercise and subsequent flush with saline solution, respectively.

Safety criteria for administering and interrupting stress should be in accordance with established guidelines, reinforcing the need for a maximum test.61

Following intravenous administration of the radiopharmaceutical, stimulate continuation of stress for 1 more minute.

When using MIBI-99mTc (absolute preference in Brazil), image acquisition follows conventional protocols (30 to 60 minutes after stopping stress). Variations in initial acquisition time depend on patient type (obesity, prior abdominal surgery, prominent extracardiac activity in the resting images phase.

When using thallium-201, considering the phenomenon of redistribution, images should be taken 10 to 15 minutes after stopping stress.

Pharmacological tests: Represent excellent alternatives for evaluating patients with physical limitations or clinical impediments to undergoing efficacious exercise testing . The most frequent conditions are found in Table 10. They represent around 20% to 30% of all cases of scintigraphy referral and approximately 50% of elderly patients.62 The drugs used in these circumstances are dipyridamole, adenosine or regadenoson, and dobutamine. These drugs induce maximum vasodilation and increase coronary flow, allowing for assessment of coronary reserve, with diagnostic and prognostic power similar to that of exercise,63,64 which has recently been extended to elderly patients and women.65,66

Table 10.

Main indications for use of pharmacological stress in patients with contraindications or limitations to undergoing exercise stress24,46

| • Motor sequelae from cerebral vascular insufficiency and degenerative or inflammatory musculoskeletal pathologies |

| • Compensated congestive heart failure |

| • Chronic pulmonary obstructive disease with important functional restriction, but without recent hyperresponsiveness |

| • Low functional capacity |

| • Other non-cardiac conditions that result in an inability to exercise efficiently |

| • Severe arterial hypertension |

| • Complex ventricular arrhythmias triggered by effort |

| • Pre-operative cardiological assessment for major abdominal vascular surgery |

| • Presence of left bundle branch intraventricular conduction disorders |

| • Risk stratification for recent evolution of myocardial infarction |

| • Use of drugs that interfere with oxygen consumption elevation |

| • Presence of artificial electric stimulation |

In cases of left His bundle branch block or artificial pacemaker with ventricular stimulation, the first option is a pharmacological test with dipyridamole or adenosine, with the aim of avoiding what are known as false-positive results (alterations in relative radiopharmaceutical uptake, in the absence of obstructive lesions). These are caused by atypical movement of the interventricular septum, which occurs in these situations and is accentuated when myocardial scintigraphy is performed with ET. Reduced radiopharmaceutical uptake is often observed in these patients and is most frequently related to the septal region, which may be exacerbated by the stress test, as increased HR increases paradoxical septal motion and, consequently, reduces perfusion in this wall.67,68

Primary vasodilators: Dipyridamole, adenosine, and regadenoson (not available for routine clinical practice in Brazil) provoke a significant increase in coronary flow in normal arteries and a small or nonexistent increase in arteries with functionally significant stenosis, thus resulting in relative heterogeneity of flow between LV walls. During maximum vasodilatation, when the radioisotope is injected, the difference in relative radiopharmaceutical uptake in LV walls will also be observed, making it possible to diagnose coronary disease:

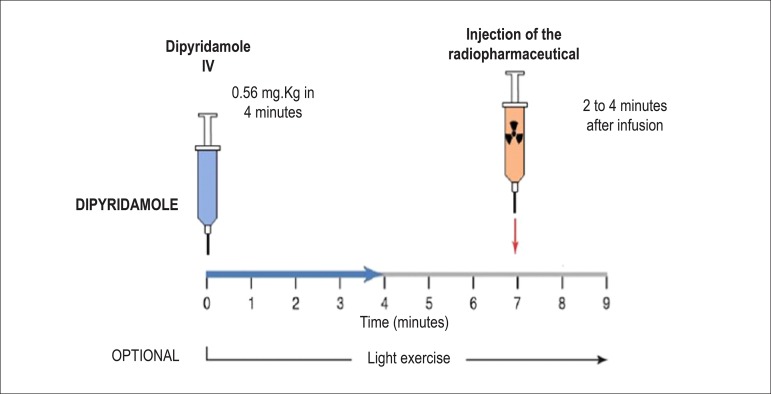

Dipyridamole: the total dose of dipyridamole is 0.56 mg.kg-1 up to a maximum dose of 60 mg or 6 vials (a 2-ml vial = 10 mg), administered intravenously (IV), preferably with a 4-minute infusion pump, diluted in 50 ml of saline solution (SS). It may, alternatively, be injected manually (with a 20-ml syringe), using the same dilution. Alternatively, a more elevated dose of 0.84 mg.kg-1 may be used in select cases. The radiopharmaceutical is administered IV during hyperemia or maximum vasodilation, 2 to 4 minutes after the end of dipyridamole infusion (Figure 4). Dipyridamole inhibits the action of the enzyme adenosine deaminase, wich degrades endogenous adenosine, in addition to blocking reuptake of adenosine into the cellular membrane, with a consequent increase in extracellular concentration and resulting coronary vasodilation. Its biological half-life is approximately 45 minutes.

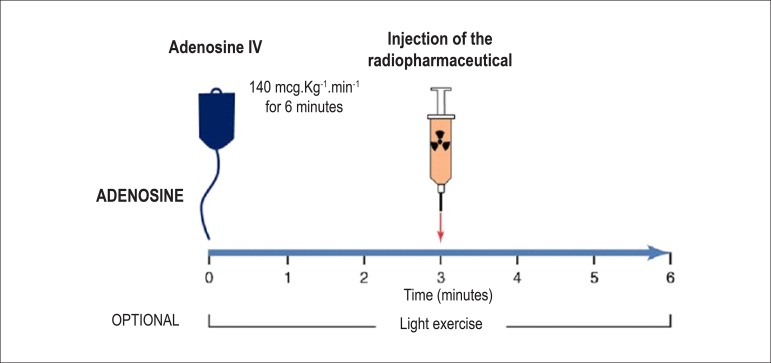

Adenosine: The usual dose is 140 µg.kg-1.min-1, and it must mandatorily be administered via a 6-minute continuous infusion pump, diluted in 50 ml of SS, with the injection of the radiopharmaceutical administered during the third minute via a different intravenous access (Figure 5). It is, also, possible to inject the solution for 4 minutes, in which case the radiopharmaceutical is administered during the second minute.69 Because xanthines block the vasodilation effect, patients should be instructed to suspend them for 24 hours before a scheduled exam with dipyridamole or 12 hours before a scheduled exam with adenosine, in addition to any other drug or product, food, or drink that contains methylxanthines or theophyllines, including coffee, tea, soft drinks, chocolate, energy drinks, compound analgesics containing caffeine, especially for treatment of muscular pain or migraines, et al. Reference lists are available for consultation.70 Adenosine induces coronary vasodilation via specific activation of A2A receptors in the cellular membrane, resulting in increased coronary flow up to 4- or 5-fold resting values.

Figure 4.

Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy associated with injection of dipyridamole. The moment of maximum vasodilation or coronary hyperemia occurs between 2 and 4 minutes after completing intravenous dipyridamole administration (blue arrow, 4 minutes), at which point the radiopharmaceutical (99mTc-tetrofosmin or MIBI-99mTc, orange arrow) is injected. Clinical observation should be continuous throughout the exam, registering blood pressure, heart rate, and electrocardiogram every 2 minutes or in accordance with medical decision, with a typical total exam time of 9 to 10 minutes.24,46

Figure 5.

Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy associated with injection of adenosine. The need for continuous intravenous administration is due to the drug’s ultrashort plasma half-life (2 to 10 seconds), with the aim of maintaining coronary hyperemia, which reaches its peak close to the third minute. At this moment, the radiopharmaceutical (MIBI-99mTc) is injected. After completing the solution at 6 minutes, frequent monitoring of blood pressure, heart rate, and electrocardiographic registers is maintained for a variable time of 4 to 6 minutes

Accuracy for detecting CAD with the use of MPS is comparable between both drugs. It is worth reiterating that, in exams using dipyridamole and adenosine, modifications in the ST segment occur relatively infrequently, even in patients with obstructive CAD (lower sensibility). In some instances, only the relative difference in flow observed in patients with different degrees of luminal obstruction and coronary reserve will determine perfusion defects, and ischemia will not necessarily be present. For this condition, collateral circulation is necessary, which causes coronary steal, with consequent alterations in contractility. Nevertheless, the sensitivity of scintigraphy images associated with the use of pharmacological agents or stress tests is similar. Adverse effects or “paraeffects” of using these drugs23,71 occur in approximately 50% of patients with dipyridamole and in up to 80% of patients with adenosine. Common side effects include headache, dizziness, flushed face, feeling hot, chest pain, ST alterations and others (Tables 11 and 12).72 These manifestations generally do not last long, and in most cases they may be reversed by administering intravenous aminophylline at 1 to 2 mg.kg-1 or 72 mg (3 ml) to 240 mg (10 ml or 1 vial) 2 minutes after injecting the radiotracer, when MPS is associated with dipyridamole. When adenosine is used, there is no need to inject an antagonist, given its ultrashort half-life, from 2 - 10 seconds, the recommendation being simply to interrupt the infusion. When it is not medically possible to perform either the physical stress or the pharmacological dilation modality with dipyridamole or adenosine, intravenous administration of dobutamine solution may be the best option for assessing coronary reserve flow, with regards to increased MVO2. Contraindications to dipyridamole and adenosine use are listed in Table 13.

Table 11.

Adverse effects or "paraeffects" related to intravenous administration of dipyridamole for performance of myocardial perfusion scintigraphy24,46

| Adverse effects or paraeffects | % |

|---|---|

| Chest pain | 20 |

| Headache | 12 |

| Dizziness | 12 |

| Alterations in ST | 8 |

| Ventricular extrasystoles | 5 |

| Nausea | 5 |

| Arterial hypotension | 5 |

| Facial flushing | 3 |

| Atrioventricular blockage | 2 |

| Fatal or non-fatal myocardial infarction | Extremely rare |

| Any minor event | 50 |

Table 12.

Adverse effects or "paraeffects" related to intravenous adenosine administration via infusion pump for performance of myocardial perfusion scintigraphy24,46

| Adverse effects or paraeffects | % |

|---|---|

| Facial flushing | 35 to 40 |

| Chest pain | 25 to 30 |

| Shortness of breath | 20 |

| Dizziness | 7 |

| Nausea | 5 |

| Symptoms of hypotension | 5 |

| Atrioventricular blockage | 8 |

| Alterations in ST | 5 - 7 |

| Atrial fibrillation | Case reports |

| Convulsions | Case reports |

| Hemorrhagic/ischemic stroke | Case reports |

| Any minor event | 80 |

Table 13.

| Absolute |

| • Bronchospastic disease during activity, recent hyperreactivity (< 3 months), status asthmaticus |

| • Second- or third-degree atrioventricular blockage, in the absence of a pacemaker |

| • Arterial hypotension (systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg) |

| • Recent transient ischemic attack or cerebrovascular accident (< 2 months) |

| • Recent use (less than 24 hours) of dipyridamole in patients who are to receive adenosine |

| Relative |

| • History of reactive pulmonary disease, with no recent crises (> 3 months) |

| • Sinus node disease |

| • Severe sinus bradycardia |

| • Severe bilateral carotid disease |

It is, finally, important to stress that, with both dipyridamole and adenosine, no significant increases are observed in MVO2, which, in clinical practice, is translated as the product of heart rate (HR) × systolic blood pressure (SBP), or the double product. During pharmacological stimulation, SBP values generally drop by around 10% while HR increases by approximately the same proportion, with no consequent increase in MVO2.

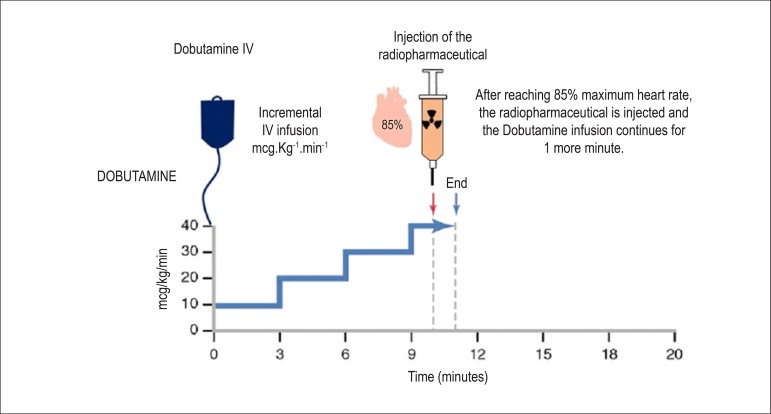

Drugs that promote elevated myocardial oxygen consumption: These drugs represent an alternative for patients who cannot undergo ET or pharmacological stress with dipyridamole or adenosine. Examples include patients who have contraindications or limitations for stress test, as well as pulmonary obstructive disease with recent crises of bronchial hyperreactivity, arterial hypotension (SBP < 90 mmHg), and significant obstructive carotid artery lesions on both sides. This is also an alternative modality in patients indicated for dipyridamole or adenosine who have ingested substances derived from caffeine or methylxanthines (competitive antagonists) over the past 24 and 12 hours, respectively. The most commonly used is dobutamine, which acts on beta-1 (β-1) adrenergic receptors, with chronotropic and inotropic stimulation, depending on the infused dose, in addition to direct effects on beta-2 (β-2) receptors, with peripheral vasodilation response. This results in an increase in cardiac output, HR, and SBP, leading to an increase in MVO2 and, consequently, in coronary vasodilation. Protocol: The protocol begins with venous administration of the solution (250 mg of dobutamine diluted in 250 ml of saline solution - 1 mg per 1 ml) via infusion pump at a dose of 10 ug.kg-1.min-1 for 3 minutes (first step), followed by 20 µg.kg-1.min-1 for 3 minutes (second step), adding 10 µg.kg-1.min-1 every 3 minutes (third and fourth steps) until the maximum dose of 40 µg.kg-1.min-1 has been reached (Figure 6).73,74 In patients who have not reached submaximal HR and who do not have evidence of ischemia, it is possible to associate intravenous atropine (0.25 to 2 mg) and perform isometric stress with hand grip maneuvers (e.g., compressing a tennis ball). A Brazilian study has demonstrated that early use of atropine (following the first phase of dobutamine infusion) is safe and that it reduces infusion time and complaints during stress, without affecting diagnostic precision.75 Furthermore, the presence of perfusion defects induced by pharmacological vasodilatation and motility abnormalities triggered by stress aggregate incremental prognostic value to the test, which has recently been validated with the use of ultrarapid cameras (CZT technology).76 Contraindications to dobutamine use may be found in Table 14. Patients on betablockers should stop taking these medications for 48 to 72 hours before the test. Special attention should be given to patients with bronchospasm undergoing MPS with dobutamine, whose plasma half-life is around 2 to 3 minutes, considering that its antagonist is metoprolol at an intravenous dose of 5 mg and that it is contraindicated in the presence of pulmonary obstructive disease. The most frequent adverse events or paraeffects associated with administration of dobutamine solution are listed in Table 15. To reverse them, in addition to metoprolol, other intravenous short-acting betablockers, such as esmolol (0.5 mg.kg), which is available, should be injected after the first minute of radiotracer injection.

Figure 6.

Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy associated with intravenous administration of dobutamine solution (250 mg or 1 vial diluted in 250 ml of saline solution). It may begin with an alternative initial dose of 5 mcg.kg-1.min-1, for 3 minutes, with sequentially increasing doses every 3 minutes, up to 40 mcg.kg-1.min-1 or until 85% of maximum heart rate has been reached (explained in the figure and the text), at which point the radiopharmaceutical (MIBI-99mTc or 99mTc-tetrofosmin) is injected. In the event of inadequate increase in heart rate and in the absence of contraindications (glaucoma, prostatic hypertrophy), atropine is additionally recommended, either early on or starting at the third step.

Table 14.

| Absolute |

| • Cardiac arrhythmias including atrial fibrillation and ventricular tachycardia (sustained or non-sustained) |

| • Severe aortic stenosis and hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy |

| • Systolic arterial hypotension (< 90 mmHg), uncontrolled systolic arterial hypertension (systolic > 200 mmHg), severe or stage III hypertension |

| • Unstable angina or recent myocardial infarction |

| • Aneurysms or aortic dissection |

| • Symptomatic vascular cerebral insufficiency |

| • Presence of implanted cardiac defibrillator |

| • Alterations in metabolism of potassium |

| Relative |

| • Abdominal aortic aneurysm (> 5 cm in diameter) |

| • Presence of thrombi in left ventricle |

| • Left ventricular ejection fraction < 25% (due to increased risk of ventricular arrhythmias) |

Table 15.

| Adverse effects | % |

|---|---|

| ST alterations | 33 |

| Precordial pain | 31 |

| Palpitation | 29 |

| Headache | 14 |

| Facial flushing | 14 |

| Dyspnea | 14 |

| Significant arrhythmias (supraventricular and ventricular) | 8 to 10 |

Combined stress: The association of dynamic stress with low workloads (e.g., until the second stage of the Bruce protocol or until feeling light fatigue, equivalent to the number 13 on the subjective Borg stress scale) and vasodilators has been shown to reduce subdiaphragmatic (hepatic) activity and improve the ratio of radiation activity emitted between the target organ and the viscera (background), with consequent improvements in image quality.77 It has similarly shown a decrease in the occurrence of adverse effects resulting from the infusion of dipyridamole or adenosine, as well as the incidence of atrioventricular blockage. This protocol is ideal for patients who are able to exercise but who are using medications that limit increases in HR (betablockers, antiarrhythmic drugs, et al.).

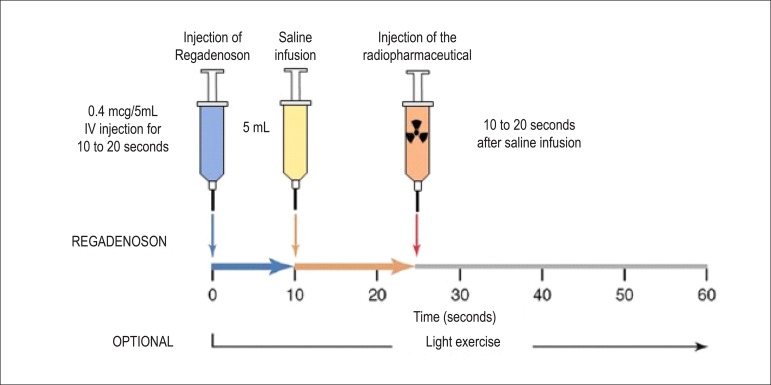

New drugs: There are 3 types of adenosine receptors (Table 16). The use of specific selective antagonists to A2 receptors has shown evidence of adequate coronary hyperemia and lower intensity of systemic effects, especially chest pain and atrioventricular blockage. A double-blind, randomized (regadenoson or adenosine), multicenter study78 involving 784 patients has shown that diagnostic information is similar and that there were no serious adverse effects; regadenoson, however, was tolerated better than adenosine. Second-degree atrioventricular blockage occurred in 3 patients with adenosine and in no patients with regadenoson. Regadenoson’s short biological half-life minimizes and limits the duration of adverse effects, diminishing monitoring time. It is administered via bolus, and it is not necessary to adjust dose to body weight (Figure 7). Its use is promising in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The incidence of serious complications79 with the performance of cardiovascular stress is related in Table 17.

Table 16.

Types of existing receptors in the cellular membrane and responses to stimuli

| Type | Resulting effects |

|---|---|

| A1 | Atrioventricular blockage |

| A2a | Coronary artery vasodilation |

| A2b | Peripheral vasodilation, bronchospasm |

| A3 | Bronchospasm |

Figure 7.

Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy associated with intravenous administration of regadenoson, a specific agonist of adenosine A2A receptors in the cellular membrane. Activation of the receptor produces coronary vasodilation with a consequent increase in flow, similar to dipyridamole and adenosine. Maximum plasma concentration is reached 1 to 4 minutes after injection, with a biological half-life of 2 to 4 minutes during the first phase. The intermediate and the late phases follow, with approximate duration of 30 minutes (loss of pharmocodynamic effect) and 2 hours (decline in plasma concentration). The radiopharmaceutical, MIBI-99mTc or Tetrofosmin- 99mTc, is injected at the moment of maximum hyperemia, close to 30 seconds after injection of regadenoson.

Table 17.

Serious adverse events related to cardiovascular stress methods (rate of events observed per 1,000 individuals)79

| Serious events | ET | Dobut | Dipy | Aden | Regad |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any event | 0.1 - 3.46 | 2.988 | 0.714 - 2.6 | 0.97 | CR |

| Death | 0 to 0.25 | CR | 0.5 | CR | CR |

| VF/VT | 0 to 25.7 | 0.6 - 1.35 | NR | NR | NR |

| AMI | 0.038 | 0.3 - 3 | 1 | 0.108 | CR |

| Cardiac rupture | Unk | CR | NR | NR | NR |

| High-grade AVB / ASY | Unk | NR | CR | CR | CR |

| Bronchospasm | Unk | NR | 1.5 | 0.76 | CR |

| Stroke/TIA | Unk | CR | NR | NR | CR |

| AF | Unk | 5 - 40 | NR | NR | CR |

| Seizure | Unk | CR | NR | 1.5 | CR |

Aden: adenosine; AVB: atrioventricular blockage; AF: atrial fibrillation; AMI: acute myocardial infarction; ASY: asystole; CR: case report; Dipy: dipyridamole; Dobut: dobutamine; ET: exercise testing; NR: not reported; Regad: regadenoson; TIA: transient ischemic attack; Unk: Unknown; VF/VT: ventricular fibrillation/ventricular tachycardia.

5.5. Image Generation and Perfusion Defects in Myocardial Scintigraphy with Radioisotopes

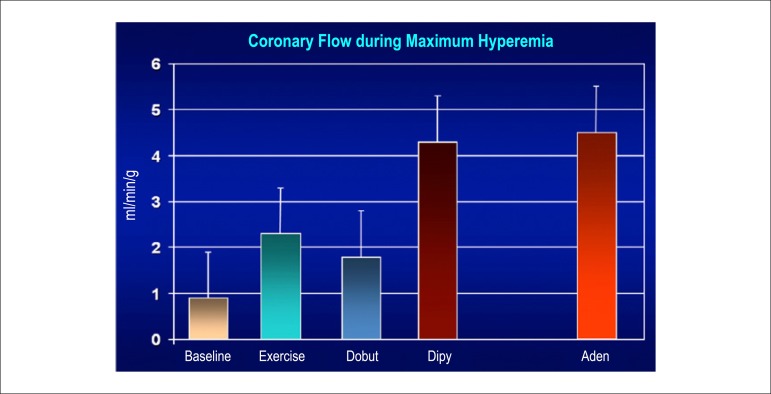

Resting coronary flow is 1 ml.g.min-1, increased 3- to 5-fold during maximal vasodilation or hyperemia, under physical or pharmacological stress (Figure 8).28 In the presence of obstructive coronary lesions, resting coronary flow decreases when luminal narrowing is greater than 80%, due to exhaustion of the coronary reserve. When physical or pharmacological stress are applied, early exhaustion of the coronary reserve is observed, and it then exhibits a drop, generally beginning with lesions with luminal narrowing of 50%.80 This information has currently been validated based on invasive measures of coronary flow reserve (CFR), fractional flow reserve (FFR), and instantaneous flow reserve (IFR), considered “standard” for characterizing myocardial ischemia; some have also been reproduced by non-invasive PET methods.81-86 Tests with pharmacological stimulation using dipyridamole or adenosine associated with MPS are considered frequently to result in coronary flows in the range of 4 ml per gram of myocardium per minute,87-89 generating homogenous relative uptake patterns of the radioisotopes in the myocardium, and scintigraphy images are considered normal when the coronary arteries are free of atherosclerotic processes. There are, however, specific situations in which patients with balanced multivessel disease (lesions in 3 arteries with similar coronary reserve) in which perfusion images appear with apparently homogeneous radiopharmaceutical distribution.90

Figure 8.

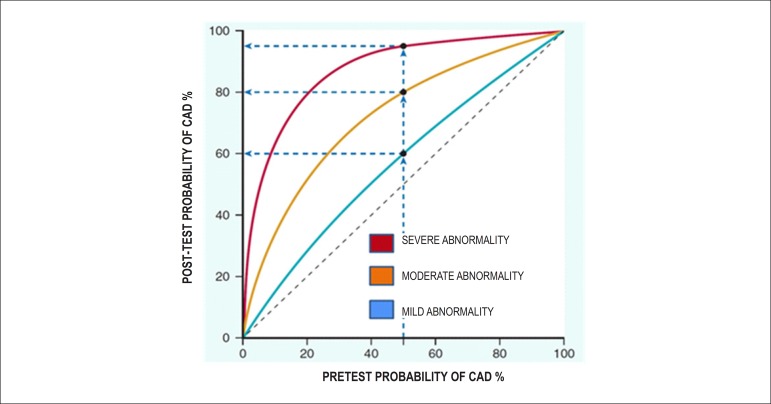

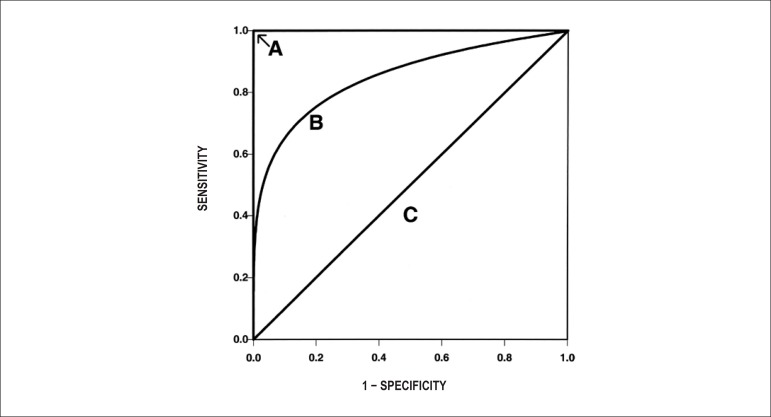

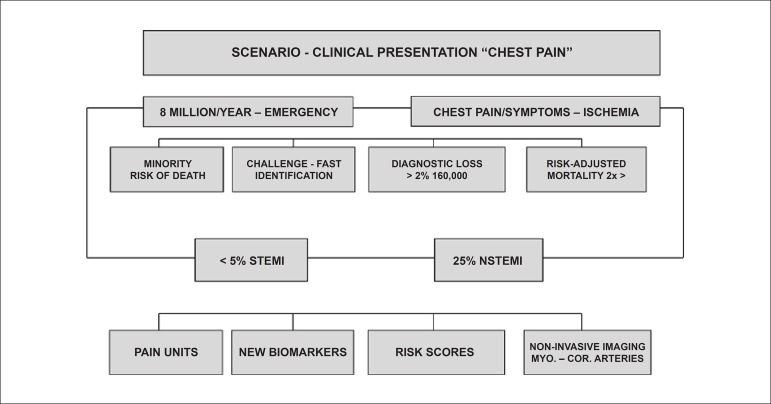

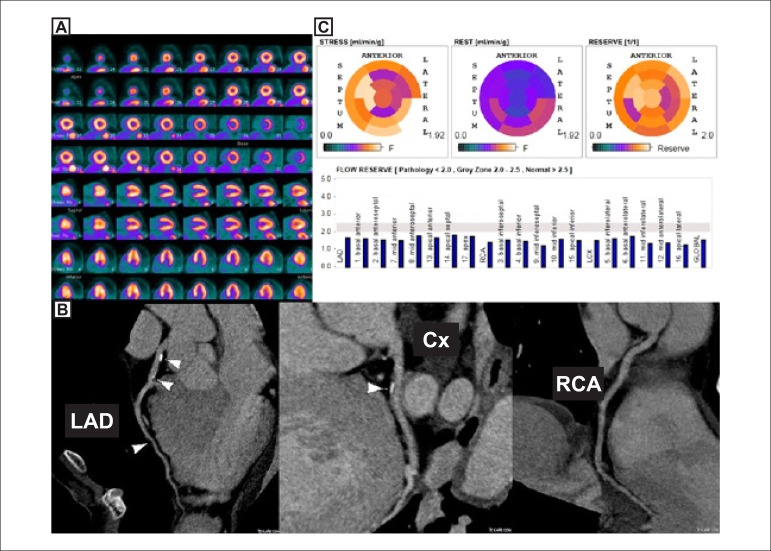

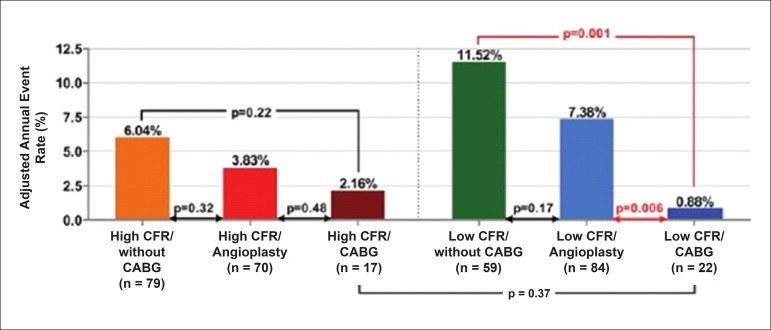

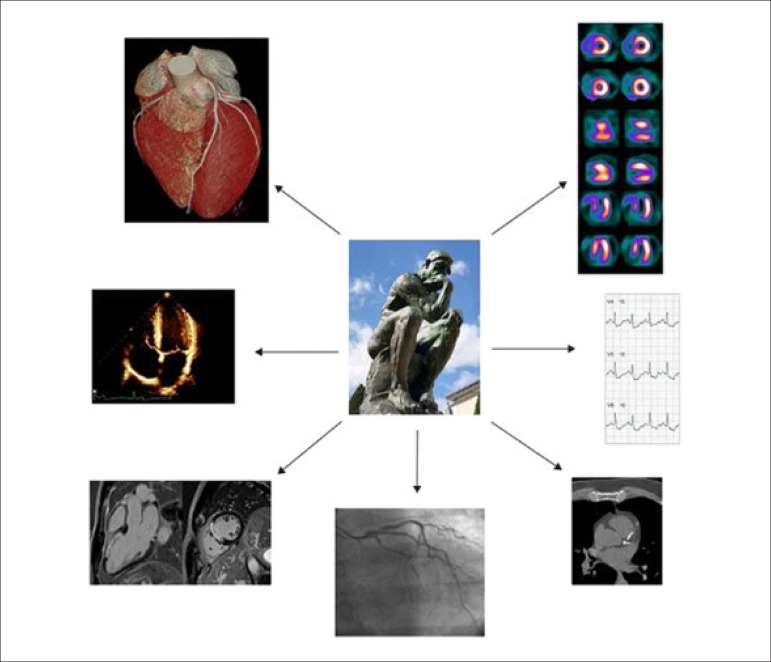

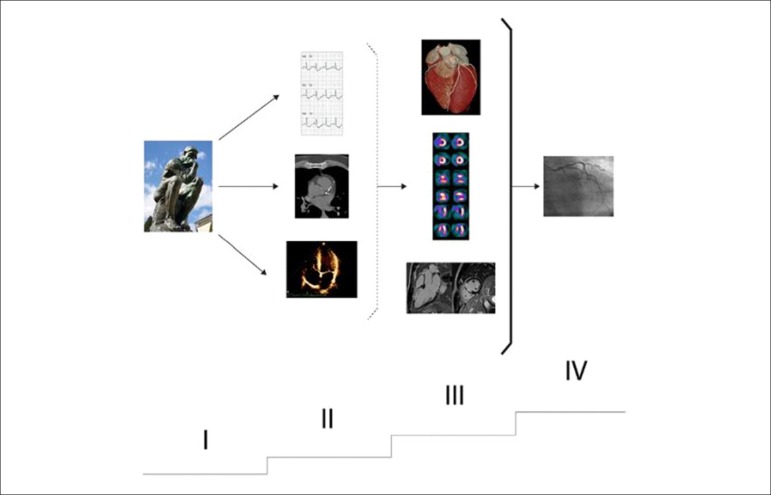

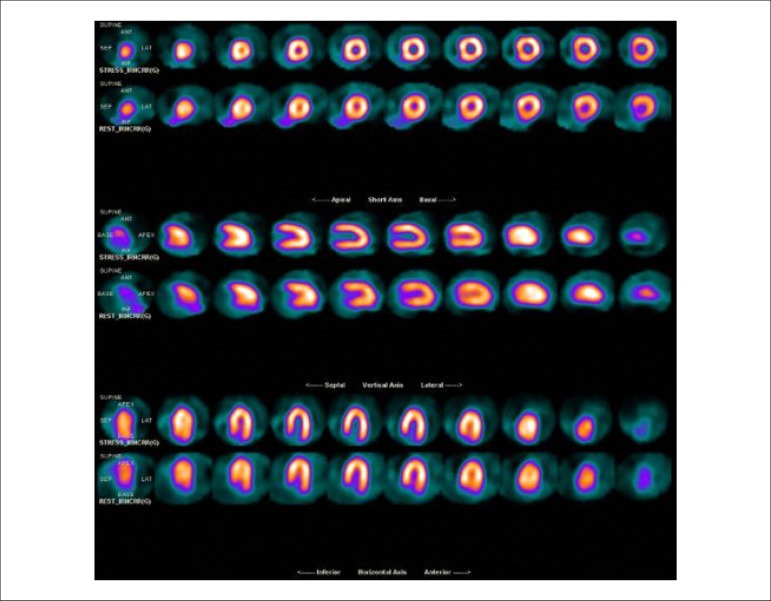

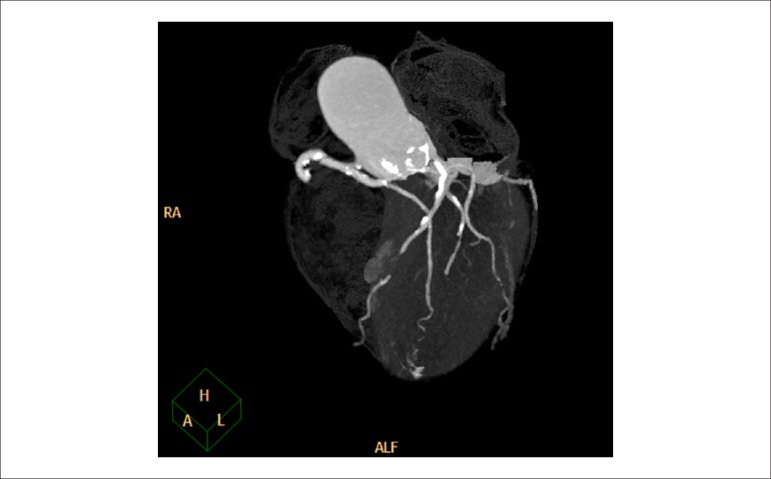

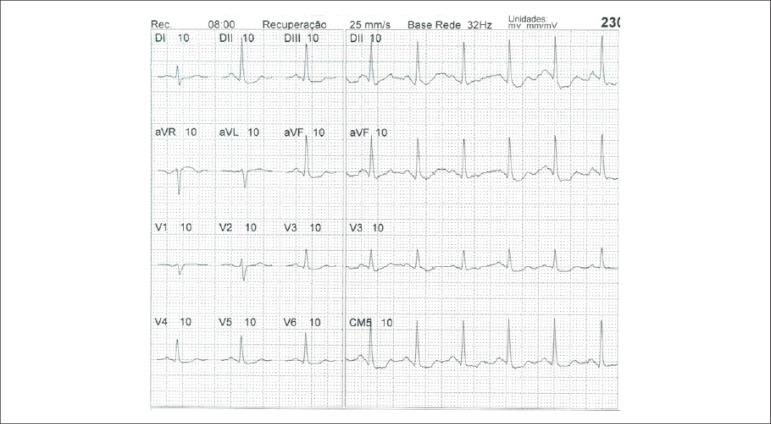

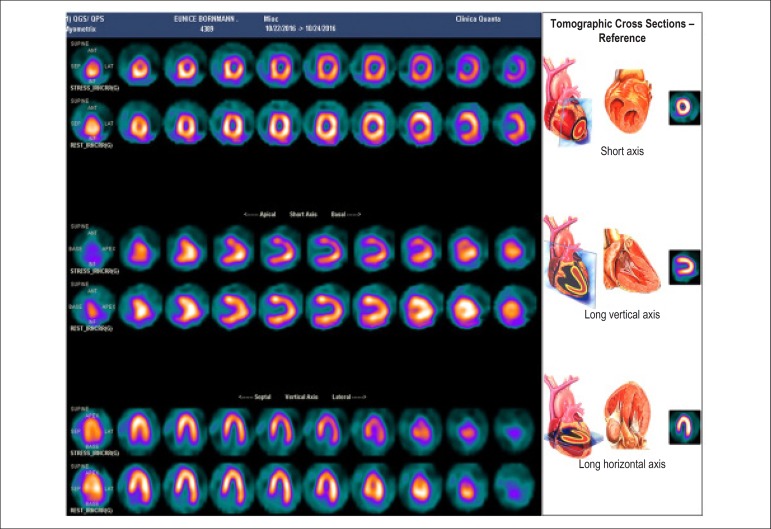

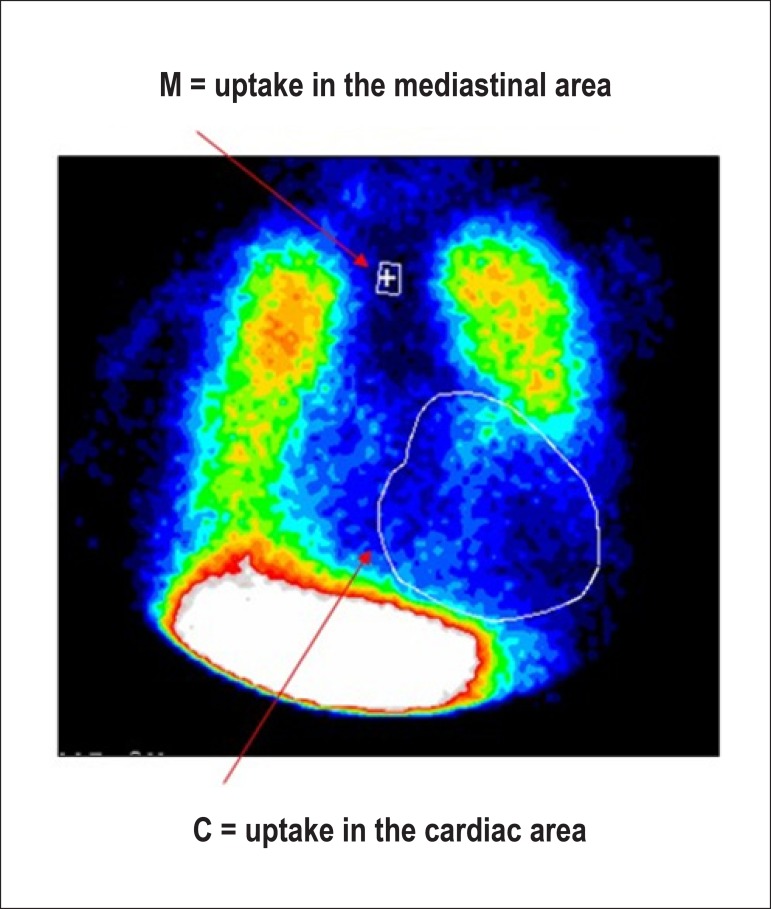

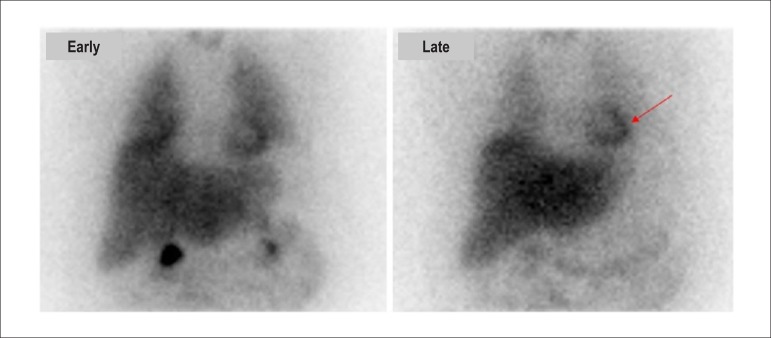

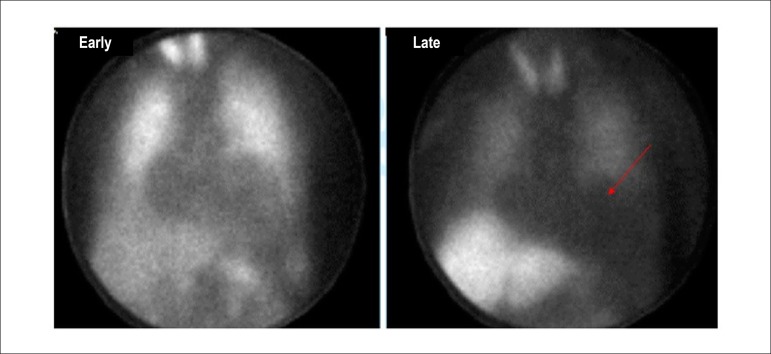

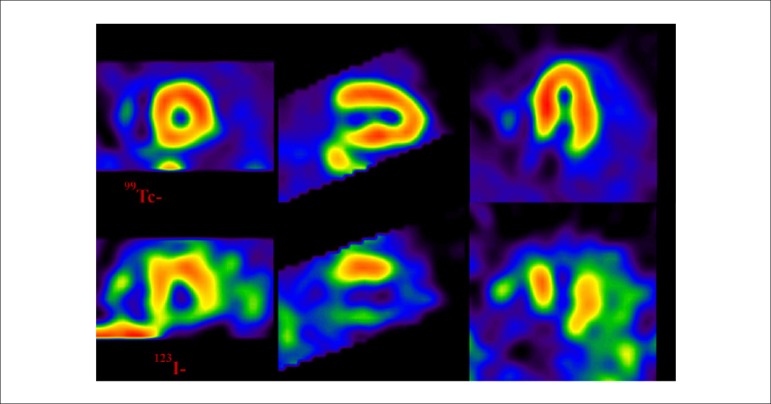

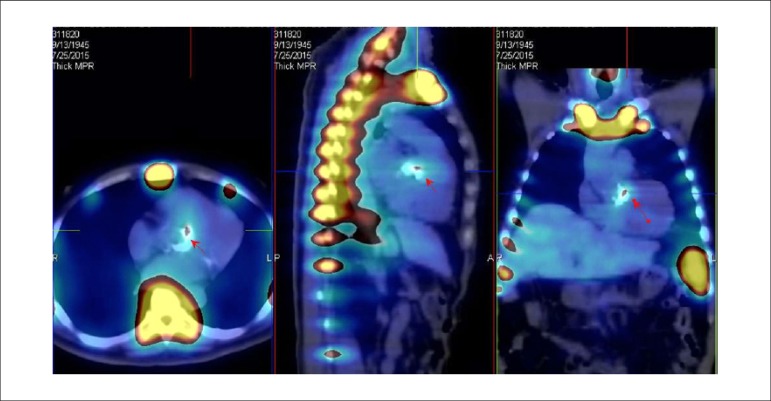

Effects of different types of stress methods on coronary flow elevation and values reached during maximum hyperemia. Baseline: resting coronary flow, 1 ml.min.g-1; Exercise: reaching values 2.5 to 3.5 times baseline coronary flow value; Dobut (dobutamine): reaching values around 2.0 to 2.5 times baseline coronary flow value; Dipy (dipyridamole) and Aden (adenosine): reaching values as high as 5.0 times baseline coronary flow value.28