Abstract

Background

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is an evidence‐based treatment for anxiety disorders. Many people have difficulty accessing treatment, due to a variety of obstacles. Researchers have therefore explored the possibility of using the Internet to deliver CBT; it is important to ensure the decision to promote such treatment is grounded in high quality evidence.

Objectives

To assess the effects of therapist‐supported Internet CBT (ICBT) on remission of anxiety disorder diagnosis and reduction of anxiety symptoms in adults as compared to waiting list control, unguided CBT, or face‐to‐face CBT. Effects of treatment on quality of life and patient satisfaction with the intervention were also assessed.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Review Group Specialised Register (CCDANCTR) to 16 March 2015. The CCDANCTR includes relevant randomised controlled trials from MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO and CENTRAL. We also searched online clinical trial registries and reference lists of included studies. We contacted authors to locate additional trials.

Selection criteria

Each identified study was independently assessed for inclusion by two authors. To be included, studies had to be randomised controlled trials of therapist‐supported ICBT compared to a waiting list, attention, information, or online discussion group; unguided CBT (that is, self‐help); or face‐to‐face CBT. We included studies that treated adults with an anxiety disorder (panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, post‐traumatic stress disorder, acute stress disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, and specific phobia) defined according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders III, III‐R, IV, IV‐TR or the International Classification of Disesases 9 or 10.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed the risk of bias of included studies and judged overall study quality. We used data from intention‐to‐treat analyses wherever possible. We assessed treatment effect for the dichotomous outcome of clinically important improvement in anxiety using a risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). For disorder‐specific and general anxiety symptom measures and quality of life we assessed continuous scores using standardized mean differences (SMD). We examined statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic.

Main results

We screened 1736 citations and selected 38 studies (3214 participants) for inclusion. The studies examined social phobia (11 trials), panic disorder with or without agoraphobia (8 trials), generalized anxiety disorder (5 trials), post‐traumatic stress disorder (2 trials), obsessive compulsive disorder (2 trials), and specific phobia (2 trials). Eight remaining studies included a range of anxiety disorder diagnoses. Studies were conducted in Sweden (18 trials), Australia (14 trials), Switzerland (3 trials), the Netherlands (2 trials), and the USA (1 trial) and investigated a variety of ICBT protocols. Three primary comparisons were identified, therapist‐supported ICBT versus waiting list control, therapist‐supported versus unguided ICBT, and therapist‐supported ICBT versus face‐to‐face CBT.

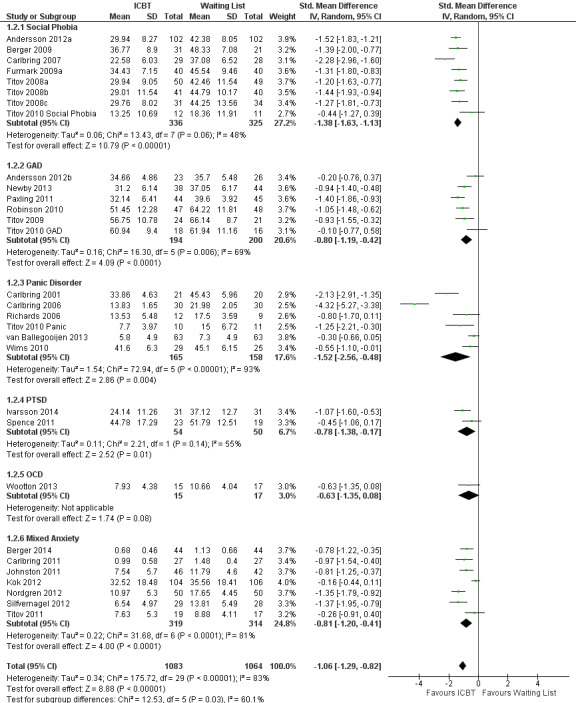

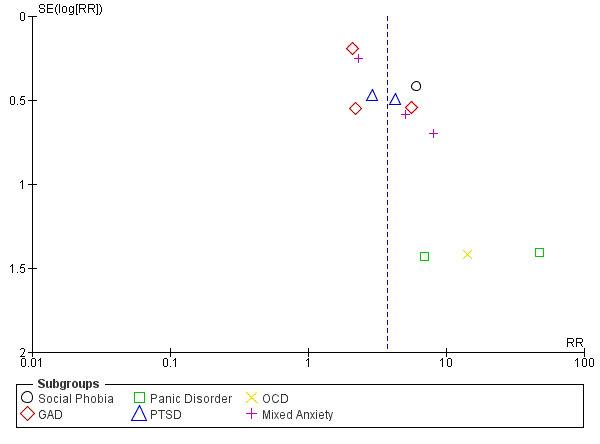

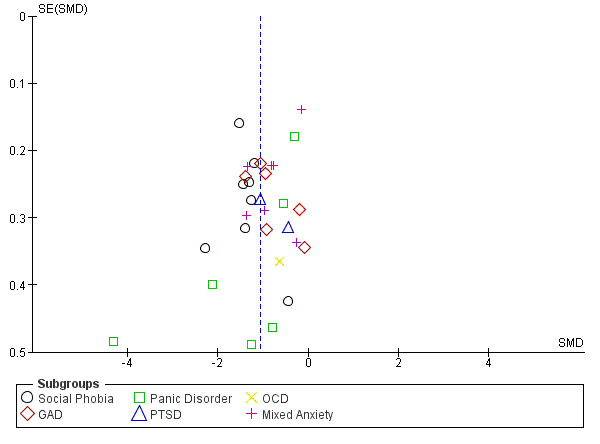

Low quality evidence from 11 studies (866 participants) contributed to a pooled risk ratio (RR) of 3.75 (95% CI 2.51 to 5.60; I2 = 50%) for clinically important improvement in anxiety at post‐treatment, favouring therapist‐supported ICBT over a waiting list, attention, information, or online discussion group only. The SMD for disorder‐specific symptoms at post‐treatment (28 studies, 2147 participants; SMD ‐1.06, 95% CI ‐1.29 to ‐0.82; I2 = 83%) and general anxiety symptoms at post‐treatment (19 studies, 1496 participants; SMD ‐0.75, 95% CI ‐0.98 to ‐0.52; I2 = 78%) favoured therapist‐supported ICBT; the quality of the evidence for both outcomes was low.

One study compared unguided CBT to therapist‐supported ICBT for clinically important improvement in anxiety at post‐treatment, showing no difference in outcome between treatments (54 participants; very low quality evidence). At post‐treatment there were no clear differences between unguided CBT and therapist‐supported ICBT for disorder‐specific anxiety symptoms (5 studies, 312 participants; SMD ‐0.22, 95% CI ‐0.56 to 0.13; I2 = 58%; very low quality evidence) or general anxiety symptoms (2 studies, 138 participants; SMD 0.28, 95% CI ‐2.21 to 2.78; I2 = 0%; very low quality evidence).

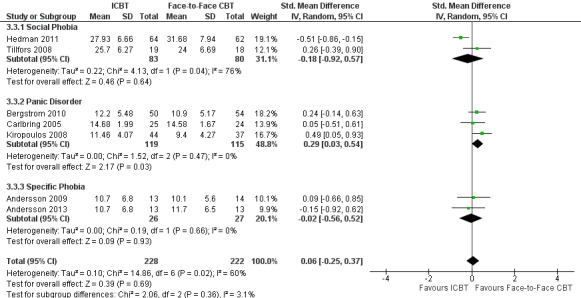

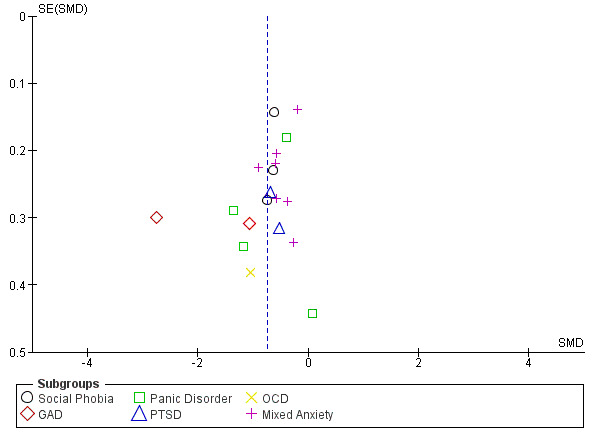

Compared to face‐to‐face CBT, therapist‐supported ICBT showed no significant differences in clinically important improvement in anxiety at post‐treatment (4 studies, 365 participants; RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.34; I2 = 0%; low quality evidence). There were also no clear differences between face‐to‐face and therapist supported ICBT for disorder‐specific anxiety symptoms at post‐treatment (7 studies, 450 participants; SMD 0.06, 95% CI ‐0.25 to 0.37; I2 = 60%; low quality evidence) or general anxiety symptoms at post‐treatment (5 studies, 317 participants; SMD 0.17, 95% CI ‐0.35 to 0.69; I2 = 78%; low quality evidence).

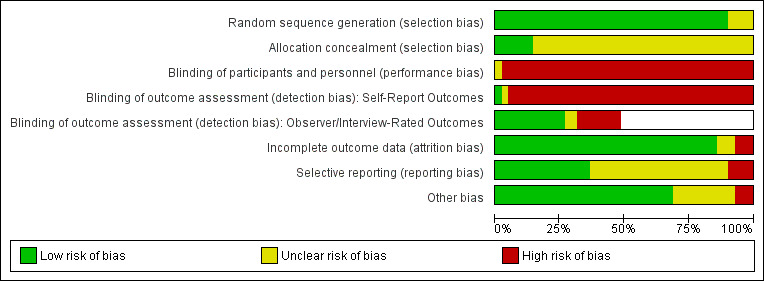

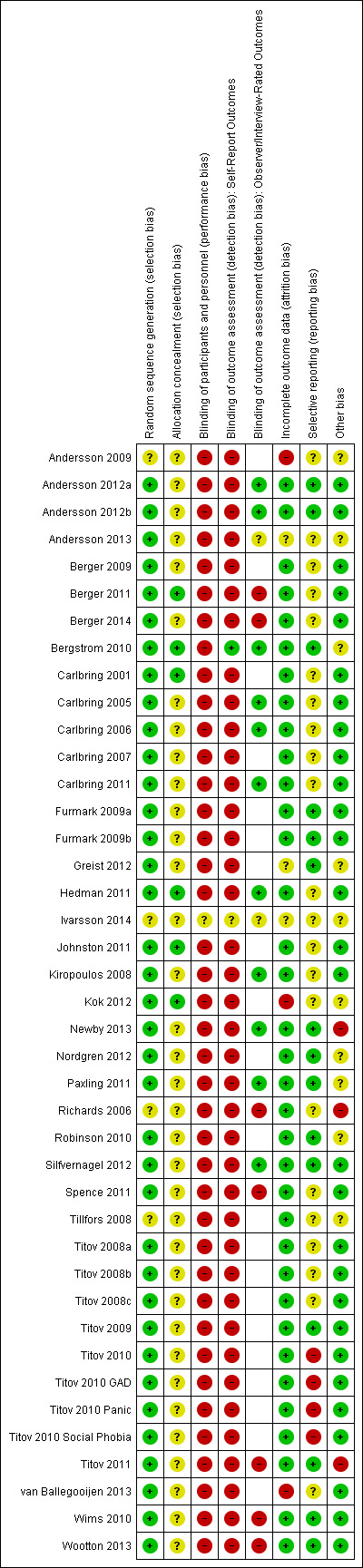

Overall, risk of bias in included studies was low or unclear for most domains. However, due to the nature of psychosocial intervention trials, blinding of participants and personnel, and outcome assessment tended to have a high risk of bias. Heterogeneity across a number of the meta‐analyses was substantial, some was explained by type of anxiety disorder or may be meta‐analytic measurement artefact due to combining many assessment measures. Adverse events were rarely reported.

Authors' conclusions

Therapist‐supported ICBT appears to be an efficacious treatment for anxiety in adults. The evidence comparing therapist‐supported ICBT to waiting list, attention, information, or online discussion group only control was low to moderate quality, the evidence comparing therapist‐supported ICBT to unguided ICBT was very low quality, and comparisons of therapist‐supported ICBT to face‐to‐face CBT were low quality. Further research is needed to better define and measure any potential harms resulting from treatment. These findings suggest that therapist‐supported ICBT is more efficacious than a waiting list, attention, information, or online discussion group only control, and that there may not be a significant difference in outcome between unguided CBT and therapist‐supported ICBT; however, this latter finding must be interpreted with caution due to imprecision. The evidence suggests that therapist‐supported ICBT may not be significantly different from face‐to‐face CBT in reducing anxiety. Future research should explore heterogeneity among studies which is reducing the quality of the evidence body, involve equivalence trials comparing ICBT and face‐to‐face CBT, examine the importance of the role of the therapist in ICBT, and include effectiveness trials of ICBT in real‐world settings. A timely update to this review is needed given the fast pace of this area of research.

Plain language summary

Internet‐based cognitive behavioural therapy with therapist support for anxiety in adults: a review of the evidence

Who may be interested in this review?

People who suffer from anxiety and their families.

General Practitioners.

Professionals working in psychological therapy services.

Developers of Internet‐based therapies for mental health problems.

Why is this review important?

Many adults suffer from anxiety disorders, which have a significant impact on their everyday lives. Anxiety disorders often result in high healthcare costs and high costs to society due to absence from work and reduced quality of life. Research has shown that cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is an effective treatment which helps to reduce anxiety. However, many people are not able to access face‐to‐face CBT due to long waiting lists, lack of available time for appointments, transportation problems, and limited numbers of qualified therapists.

Internet‐based CBT (ICBT) provides a possible solution to overcome many of the barriers to accessing face‐to‐face therapy. Therapists can provide support to patients who are accessing Internet‐based therapy by telephone or e‐mail. It is hoped that this will provide a way of increasing access to CBT, particularly for people who live in rural areas. It is not yet known whether ICBT with therapist support is effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety.

What questions does this review aim to answer?

This review aims to summarise current research to find out whether ICBT with therapist support is an effective treatment for anxiety.

The review aims to answer the following questions:

‐ is ICBT with therapist support more effective than no treatment (waiting list)?

‐ how effective is ICBT with therapist support compared with face‐to‐face CBT?

‐ how effective is ICBT with therapist support compared with unguided CBT (self‐help with no therapist input)?

‐ what is the quality of current research on ICBT with therapist support for anxiety?

Which studies were included in the review?

Databases were searched to find all high quality studies of ICBT with therapist support for anxiety published until March 2015. To be included in the review, studies had to be randomised controlled trials involving adults over 18 years with a main diagnosis of an anxiety disorder; 38 studies with a total of 3214 participants were included in the review.

What does the evidence from the review tell us?

ICBT with therapist support was significantly more effective than no treatment (waiting list) at improving anxiety and reducing symptoms. The quality of the evidence was low to moderate.

There was no significant difference in the effectiveness of ICBT with therapist support and unguided CBT, though the quality of the evidence was very low. Patient satisfaction was generally reported to be higher with therapist‐supported ICBT, however patient satisfaction was not formally assessed.

ICBT with therapist support may not differ in effectiveness as compared to face‐to‐face CBT. The quality of the evidence was low.

There was a low risk of bias in the included studies, except for blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessment. Adverse events were rarely reported in the studies.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Individuals with anxiety disorders experience excessive anxiety (fear or worry) which is disproportionate to actual threat or danger and significantly interferes with normal daily functioning. Anxiety disorders can include a range of physical (for example, trembling, tense muscles, rapid breathing), cognitive (for example, worries, difficulty concentrating), emotional (for example, distress, negative affect, irritability), and behavioural (for example, difficulty sleeping, hyperarousal) symptoms. Often those with anxiety disorders develop maladaptive strategies to lessen anxiety, such as avoidance (Health Canada 2002; Wilson 2006) or substance use (Stewart 2008). Studies from Canada (Statistics Canada 2004), the USA (Kessler 2005a), Australia (Slade 2007), Nigeria (Gureje 2006), and Europe (ESEMeD/MHEDEA 2000 Investigators 2004) suggest that 6% to 18% of adults experience an anxiety disorder every year. Moreover, rates of remission within one year are low, that is, from 33% to 42% across specific anxiety disorders (Robins 1991).

There are many types of anxiety disorders, including panic disorder (PD), agoraphobia, social phobia, post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), acute stress disorder, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and specific phobia. These are diagnosed according to criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV‐R) (APA 2000) or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD 10) (WHO 1999). Anxiety disorders often co‐occur with each other (Kessler 2005a) as well as with mood disorders (Fava 2000) and substance abuse or dependence (Stewart 2008). They tend to have an early onset (Kessler 2005b) and chronic course (Bruce 2005). Anxiety disorders also have a major economic impact; for instance, costs of direct treatment, unnecessary medical treatment, and work absences or lost productivity amount to more than USD 40 billion per year in the United States (DuPont 1996; Greenberg 1999). Studies have shown significantly higher annual per capita medical costs for primary care patients with social phobia than for those with no mental health diagnosis (GBP 11,952 and EUR 2957 respectively) (Acarturk 2009); primary care patients with PD versus those with a chronic somatic condition (EUR 10,269 versus EUR 3019) (Batelaan 2007); and primary care patients with GAD as compared to those without GAD (USD 2375 versus USD 1448) (Revicki 2012).

Description of the intervention

Accumulating research supports the efficacy of CBT in the treatment of anxiety disorders (Bisson 2007; Hunot 2007; Norton 2007; Stewart 2009) and anxiety symptoms (Deacon 2004). As its name suggests, CBT includes both cognitive as well as behavioural interventions or techniques. It has no one 'founder' and now exists in many different forms. Its roots, however, lie largely in the work of Aaron Beck (Beck 1979). While pharmacotherapy (most commonly, benzodiazepines or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) has been shown to be effective in the treatment of anxiety disorders, meta‐analyses and review articles suggest that CBT is as effective in the acute phase of anxiety and may be more effective than pharmacotherapy or a combination of both treatments in the long term (Westra 1998; Otto 2000; Otto 2005; Pull 2007). Moreover, some anxiety medications pose significant risk for addiction (McNaughton 2008) or serious side effects, or both (Buffett‐Jerrot 2002; Choy 2007).

Unfortunately, certain barriers (for example, time constraints, transportation problems, stigma, long waiting lists, a lack of sufficiently qualified clinicians) continue to limit access to CBT (Alvidrez 1999; Young 2001; Mohr 2006). Many of these barriers are particularly relevant for those living in rural communities (Yuen 1996; Rost 2002; Hauenstein 2006). National surveys in Canada (Statistics Canada 2004) and the US (Kessler 2004) suggested that less than one third (only 32% and 20%, respectively) of those with a current psychiatric disorder received some form of treatment in the past year. In a Canadian sample, only 11% of individuals with an anxiety disorder had received treatment (Ohayon 2000). Increasingly, efforts are being made to improve access to CBT on a large scale, particularly for those groups who are most at risk due to lack of services (for example, the UK‐based National Health Service 'Improving Access to Psychological Therapies' (IAPT) programme launched in 2006) (Department of Health 2008). A distance delivery approach wherein CBT is delivered over the Internet with a therapist providing support by telephone or e‐mail is one way to minimize treatment barriers and increase access to care while still delivering empirically‐supported treatment. Such an approach could increase access to mental health professionals for those in rural areas, facilitate treatment for those of limited mobility, and increase patient confidentiality (that is, by engaging in treatment from home clients do not 'risk' being seen at mental health clinics) and privacy (for example, a degree of visual anonymity). The widespread availability of the Internet makes this type of intervention feasible and worth consideration. Recent systematic reviews of computer‐ and Internet‐based treatment for mental health problems suggest largely that these types of treatment are more effective than a waiting list control and equally effective as face‐to‐face psychotherapy in treating anxiety and depression symptoms (Spek 2007; Bee 2008; Cuijpers 2009; Reger 2009; Cuijpers 2010).

How the intervention might work

Therapist‐supported ICBT should work to treat anxiety in the same manner as conventional face‐to‐face CBT. The underlying principles of CBT posit that psychopathology, or emotional disturbances, are the result of cognitive distortions and maladaptive behaviour. Whereas there are hypotheses about the relative importance of cognitive and behavioural techniques, as well as suggestions that the strong collaborative working relationship between the therapist and client are key to the success of CBT, the exact mechanisms of action in CBT are not yet well understood (Olatunji 2010). It is thought that disorder‐specific symptoms develop as a result of a particular pattern of dysfunctional cognitions in combination with a specific set of behaviours that serve to exacerbate these dysfunctional cognitions further (Beck 2005). As such, CBT works to improve symptoms by treating these maladaptive cognitions and behaviours.

In essence, cognitive techniques and behaviour modification strategies are used to identify, evaluate, and challenge underlying maladaptive thoughts and beliefs. As an example, it is thought that catastrophic thoughts about the outcomes of experiencing arousal‐related physiological sensations, as well as inaccurate predictions about the probability of these dangerous outcomes, and avoidance of situations that may induce these sensations contribute to the development and maintenance of PD (Clark 1986; Barlow 1988). Accordingly, CBT for panic uses cognitive restructuring techniques to teach individuals to identify and challenge their maladaptive cognitions and beliefs. This is combined with the use of gradual, repeated exposure to feared sensations to help individuals revise their perceptions of threat and reduce their fear of these arousal‐related physiological sensations (Landon 2004). A similar description of the CBT model could be provided for the other anxiety disorders (for example, social phobia) (Heimberg 2002). Whereas the underlying cognitive and behavioural principles are evident in the CBT interventions for each of the anxiety disorders, current forms of CBT also target core components of a particular disorder and, as such, specific models of CBT now exist for each disorder, which modify and adapt CBT principles to fit disorder‐specific symptoms (for example, specific phobia (Ost 1997); OCD (Salkovskis 1985; Foa 2010); PD (Clark 1986; Casey 2004); social phobia (Heimberg 2002); GAD (Dugas 2007); PTSD (Ehlers 2000).

ICBT therapists would be expected to draw on these models in the same manner as face‐to‐face CBT therapists. Typically, ICBT involves the client following a written treatment program available on the Internet in conjunction with receiving therapist support, either via telephone calls, texts, or e‐mail (Andersson 2006). The intervention involves content that mimics that of face‐to‐face CBT, therapist‐client contact (albeit through non‐traditional means), and the client engaging in further 'homework' outside of the session. As such, we anticipated that ICBT will work in the same way and as well as traditional face‐to‐face CBT.

Why it is important to do this review

Recently, research into ICBT has elicited considerable interest from within the scientific and clinical communities. With advances in modern communication technologies and their widespread availability, this type of treatment is quickly becoming a more realistic option. These advances have come at a time when long waiting lists and a lack of treatment availability stand in stark contrast to the growing emphasis on the importance of mental health and provision of evidence‐based treatments. A desire to pursue Internet treatment as a viable option to increase access to treatment is growing. The importance of ensuring that the decision to promote such treatment is grounded firmly in high quality evidence is therefore paramount.

The present review asked whether therapist‐supported ICBT is efficacious in treating anxiety, and if it is as efficacious as face‐to‐face CBT. Past meta‐analyses have reviewed the efficacy of ICBT for anxiety symptoms (Spek 2007). A number of reviews that have included ICBT have looked more broadly, however, at health problems in general (Barak 2008; Bee 2008) or all computer‐based interventions (Cuijpers 2009; Reger 2009; Andrews 2010). Moreover, many of these reviews have not focused on the role of therapist involvement (for example, Cuijpers 2009; Reger 2009; Andrews 2010). Ultimately, as the field of ICBT is growing quickly, an updated review on therapist‐supported ICBT is needed. The findings of this review will be helpful in guiding the path of future research in this field away from continued replication of established findings and toward addressing gaps in the literature and considering the next steps in ICBT implementation.

There is a Cochrane Review on media‐delivered CBT and behavioural therapy (BT) (self‐help) for anxiety disorders (Mayo‐Wilson 2013). Mayo‐Wilson's review answers questions about the efficacy of delivering CBT to clients in non‐traditional formats, including via the Internet. In the protocol of their review, Mayo‐Wilson specified that they would not include studies with therapist contact. With a post‐protocol change, they revised their review to include studies that involved therapist contact with the qualifier that the interventions must be able to be delivered stand‐alone without therapist contact. With this in mind, the focus of their review remains largely on self‐help therapies in which therapist involvement is not necessary and treatment is largely client‐driven. Mayo‐Wilson did not conduct analyses separating out those interventions with and without therapist contact. As such, a meta‐analysis with a particular emphasis on the efficacy of therapist‐supported ICBT is needed, particularly as at this point there remains conflicting evidence of the comparable efficacy of self‐help and therapist‐supported interventions (for example, Spek 2007; Titov 2008c; Berger 2011). The present review considered the specific efficacy of therapist‐supported ICBT in comparison to each of a waiting list control (that is, no treatment), traditional face‐to‐face CBT, and self‐help interventions and as such will fill a gap in the literature and answer current calls for research in this area (Reger 2009). The protocol for the present review can be found in the Cochrane Library (Olthuis 2011).

Objectives

To assess the effects of therapist‐supported ICBT on remission of anxiety disorder diagnosis and reduction of anxiety symptoms in adults as compared to waiting list control, unguided CBT, or face‐to‐face CBT. Effects of treatment on quality of life and patient satisfaction with the intervention were also assessed.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included parallel group randomised controlled trials (RCTs), cross‐over, and cluster randomised trials.

Types of participants

Participant characteristics

We included studies of adults (over 18 years of age; no upper limit).

Diagnosis

Participants with a primary diagnosis of an anxiety disorder according to the DSM‐III (APA 1980), DSM‐III‐R (APA 1987), DSM‐IV (APA 1994), DSM‐IV‐TR (APA 2000), ICD‐9 (WHO 1979) or ICD‐10 (WHO 1999) diagnostic criteria.

We included studies that focused on or adequately reported subgroup information for any of the following anxiety disorders: panic disorder (PD) with or without agoraphobia, agoraphobia without a history of panic, social phobia (social anxiety disorder), post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), acute stress disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), specific phobia, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and anxiety disorder not otherwise specified. Included studies used diagnoses determined using a validated diagnostic instrument, for example, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV‐TR Axis I Disorders (SCID‐I) (First 2002).

Setting

We included studies in which treatment entailed participants engaging in the treatment from their homes and therapists located at primary care settings, university laboratories, community mental health clinics, or private practice clinics. Participants could be treatment‐seeking community members responding to media advertisements for study participation or they could be referred to the study by a health professional.

Co‐morbidities

We included studies of participants with co‐morbid diagnoses (for example, major depressive disorder, substance abuse) only if they had been diagnosed with a primary anxiety disorder. We did not include studies of participants reporting anxiety symptoms that did not meet criteria for an anxiety disorder (for example, participants with a clinical presentation of major depressive disorder who reported subthreshold anxiety symptoms or participants scoring high on measures of anxiety symptoms but who were not assessed for a DSM diagnosis).

Types of interventions

Experimental interventions

Cognitive behavioural therapies

We included studies that investigated the efficacy of a therapist‐supported Internet cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), behavioural therapy (BT), or cognitive therapy (CT) intervention for anxiety, defined as the following.

BT interventions must have been designed to change the behaviours that result from maladaptive anxiety‐related cognitions (we included interventions including, but not limited to, exposure, desensitization, and behavioural experiments).

CT must have been focused on elements of cognitive restructuring of irrational or maladaptive anxiety‐related cognitions.

CBT interventions consisted of some combination of the elements of CT and BT.

Whereas psychoeducation often is an important part of CBT, we did not consider psychoeducation alone to be a sufficient CBT intervention unless it included some of the other treatment components described here.

Internet interventions

To be considered an Internet intervention, CBT must have been delivered over the Internet through the use of web pages or e‐mail, or both. Crucially, Internet interventions must have included therapist support but this interaction could not be face‐to‐face. However, we included interventions that involved an initial face‐to‐face intake or interview session or an initial session to orient clients to the Internet delivery method or to engage in treatment planning, or a combination of these. Thus, therapist support must have occurred via e‐mail or the telephone, or both. Including only interventions that could be delivered entirely by distance methods reflected a primary motive for conducting this review, to find ways to increase access to treatment for those who may not be able to visit provider centres. While it was possible that Internet‐based interventions that provided some support in a face‐to‐face setting could be just as effectively restructured to be delivered completely by distance, it was more rigorous to include only studies that provided evidence specifically on the efficacy of Internet CBT delivered completely via distance methods. We did not select interventions based on their length, or the number or duration of sessions.

Comparator interventions

Waiting list, attention, information, or online discussion group only control condition (no intervention for participants beyond weekly status monitoring by research personnel or accessing online non‐treatment related disease information or discussion groups)

Unguided CBT (i.e., self‐help CBT with no therapist support)

Conventional face‐to‐face CBT interventions (including individual or group CBT delivered in a traditional face‐to‐face format)

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Efficacy of therapist‐supported ICBT in leading to clinically important improvement in anxiety as determined by a diagnostic interview, for example, the SCID‐I (First 2002) or the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule (ADIS‐IV) (DiNardo 1994) or a defined cut‐off on a validated scale, for example, the Yale Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (YBOCS) (Goodman 1989). In case the Clinical Global Impression scale change or improvement items (CGI) (Guy 1976) were used, we employed a score of 1 = 'very much' or 2 = 'much improved' to indicate clinically important improvement.

Efficacy of therapist‐supported ICBT in leading to reduction in anxiety symptom severity measured by scores on a validated, observer‐rated instrument, for example, the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (Hamilton 1959), or a validated self‐report measure of: (a) disorder‐specific symptoms, for example, the Social Phobia Scale (SPS) (Mattick 1998), and (b) anxiety symptoms in general, for example, the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Beck 1991).

Secondary outcomes

Quality of life as assessed by either measures of quality of life, for example, the Quality of Life Inventory (QOLI) (Frisch 1992), or measures of disability, for example the Sheehan Disability Scales (SDS) (Leon 1997) as increasing disability entails decreased quality of life. While research suggests that quality of life and disability are distinct but somewhat overlapping constructs (Hambrick 2003), quality of life measures have not often been conceptually or operationally distinguished from measures of disability, resulting in considerable overlap amongst indices of quality of life and disability (Mogotsi 2000). With this in mind, we anticipated an overlapping conceptualization of these two constructs in the included studies and included both types of measures within the meta‐analysis in order to capture all possible information about treatment outcome related to quality of life.

Participant satisfaction with the intervention. Participant satisfaction tends to be measured uniquely across different studies using a mix of qualitative and quantitative indices. In anticipation of this, we evaluated participants' satisfaction with the intervention of interest as compared to the comparator interventions in a qualitative manner.

Adverse events, in whatever manner reported by study authors.

Timing of outcome assessment

We performed separate analyses based on different periods of assessment: immediately post‐treatment and at one follow‐up period at least six months post‐treatment but not more than one year. When studies reported more than one follow‐up assessment point, we used the longest follow‐up period so as to provide the best estimate of the long‐term outcomes of the intervention.

Hierarchy of outcome measures

For primary outcomes, separate meta‐analyses were conducted for the two outcomes. The clinically important improvement in anxiety outcome measures were selected according to the following hierarchy, based on availability in a particular study: (1) diagnostic interview, (2) cut‐off on a validated scale, (3) CGI scores. For reduction in anxiety symptom severity, the outcomes of available observer‐rated and self‐report measures were statistically combined and a mean score was created across the measures within a particular study. Measures of variance for this mean score were created by combining standard deviations across studies according to the method described by Borenstein 2009. This method requires that the correlation between two measures be known; as such, in the case that this correlation was not known, the measures with better psychometric properties were included in the analysis.

For secondary outcomes, quality of life outcome measures were treated in the same way as anxiety symptom severity measures. Due to the qualitative nature of the other secondary outcome, participant satisfaction with the intervention, a hierarchy of outcome measures was not required.

Search methods for identification of studies

We used several methods to identify both published and unpublished studies for possible inclusion in this review (see below). We did not restrict studies to those reported in any particular language; however, we conducted searches in English and initiated contact with authors in English.

Electronic searches

The Cochrane, Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Review Group's Specialised Register (CCDANCTR)

The Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group (CCDAN) maintains two clinical trials registers at their editorial base in Bristol, UK, a references register and a studies‐based register. The CCDANCTR‐References Register contains over 39,500 reports of RCTs in depression, anxiety, and neurosis. Approximately 60% of these references have been tagged to individual, coded trials. The coded trials are held in the CCDANCTR‐Studies Register and records are linked between the two registers through the use of unique Study ID tags. Coding of trials is based on the EU‐Psi coding manual. Please contact the CCDAN Trials Search Co‐ordinator for further details. Reports of trials for inclusion in the Group's registers are collated from routine (weekly), generic searches of MEDLINE (1950 to date), EMBASE (1974 to date) and PsycINFO (1967 to date); quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and review‐specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials are also sourced from international trial registers via the World Health Organisation (WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), ClinicalTrials.gov, drug companies, and the handsearching of key journals, conference proceedings, and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses.

Details of CCDAN's generic search strategies can be found on the Group‘s website (http://cmd.cochrane.org/), or available on request from the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (email: tsc@ccdan.org).

To date, three searches have been run for this review. Two for the first published version (with searches to 12 April 2013 and 25 September 2014, Appendix 1) and the latest search to 16 March 2015 (listed below). All findings have now been fully incorporated into the meta‐analyses.

1. CCDANCTR‐Studies and CCDANCTR References:

The CCDANCTR was searched all years to 16 March 2015 using the following (amended) search strategy and results de‐duplicated against those retrieved previously (using the Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS) software).

#1 (anxiety or *phobi* or PTSD or post‐trauma* or “post trauma*” or posttrauma* or (stress and disorder*) or panic or OCD or obsess* or compulsi* or GAD):ti,ab,kw #2 (therap* or train*):ti,ab #3 (acceptance* or assertive* or brief* or commitment* or exposure or group or implosive or “problem solving” or problem‐solving or "solution focused" or solution‐focused or schema):ti,ab,kw #4 (psychotherap* or *CBT* or cognitive or behavio* or “contingency management” or “functional analys*” or mindfulness* or “mind training” or psychoeducat* or relaxation or “role play*”):ti,ab,kw,ky,mh,mc,emt #5 ((#2 and #3) or #4) #6 (computer* or distance* or remote or tele* or Internet* or web* or WWW or phone or mobile or e‐mail* or email* or online* or on‐line or videoconferenc* or video‐conferenc* or "chat room*" or "instant messaging" or iCBT):ti,ab,kw #7 (#1 and #5 and #6) #8 (internet* or online or web*):ti #9 (anxi* or *phobi* or panic or GAD or "general* anxiety" or OCD or obsess* or PTSD or *trauma* or "stress disorder*"):ti #10 (assisted or administer* or administr* or coach* or guided or guidance or *therapist* or ((telephone or email) next (support or assist*))):ti,ab #11 (#8 and #9 and #10) #12 (#7 or #11)

2. International Trial Registries

Trial registries were searched (to 16 March 2015) to identify unpublished and/or ongoing studies. These included ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Portal (ICTRP).

Searching other resources

Reference lists

We examined the reference lists of previous related meta‐analyses (Spek 2007; Bee 2008; Cuijpers 2009; Reger 2009; Andrews 2010; Cuijpers 2010) and of articles selected for inclusion in the present review.

Personal contacts and correspondence

We contacted experts in the field, including principal authors of RCTs in the field of ICBT for anxiety, via e‐mail and asked them if they were aware of any further studies which meet the present review’s inclusion criteria.

Unpublished studies

In order to search for unpublished studies, we searched international trial registries including via the WHO ICTRP (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/) and ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) to March 2015.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

In collaboration with the CCDAN Trials Search Co‐ordinator, one review author (JVO) conducted searches of electronic databases and reference lists and contacted authors in order to locate potential trials to be included in the review. Two review authors (JVO and KMB) independently assessed the titles and abstracts of the resulting lists of studies for relevance. We then obtained full articles for potentially relevant abstracts. Both review authors independently assessed the identified trials to determine eligibility as outlined in Criteria for considering studies for this review. We collated and compared assessments. In the case of disagreement with respect to trial eligibility, we made the final decision by discussion and consensus, if necessary with the involvement of another member of the review group (MCW or SHS, or both).

Data extraction and management

We independently extracted data from the included studies regarding methodology and treatment outcomes, and recorded the data using a data extraction spreadsheet designed by one of the review authors (JVO). If the included trials did not provide complete information (for example, details of dropout, group means and standard deviations), we contacted the primary investigator by e‐mail to attempt to obtain unreported data to permit an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis. We contacted other investigators as needed.

Two review authors (JVO and KMB) independently extracted the following data from each trial report:

description of trial, including primary researcher and year of publication;

characteristics of trial methodology, including the diagnostic criteria employed, participant inclusion and exclusion criteria, the screening instrument(s) used, the inclusion or exclusion of co‐morbidity, the receipt of other interventions simultaneously, and the number of centres involved;

characteristics of participants, including age, gender, primary diagnosis, any co‐morbid diagnoses, and duration of primary symptoms;

characteristics of the intervention (for both the experimental and comparator interventions), including intervention classification (i.e., CBT, BT, CT), content and components (e.g., psychoeducation, relaxation training, exposure, cognitive restructuring), method of delivery of therapist support (e.g., telephone, e‐mail), duration, amount of therapist and experimenter contact, and number of participants randomised to each intervention; and

outcome measures employed, as listed in Types of outcome measures, as well as the dropout rates for participants in each treatment condition and whether the data reflected intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analyses with last observation carried forward (LOCF) or another method.

We subsequently recorded data in RevMan 5.3 data tables (RevMan 2014).

Main planned comparisons

We planned to compare each of the outcomes of interest, at post‐treatment and 6 to 12 month follow‐up, for each of the following comparisons:

therapist‐supported ICBT versus waiting list, attention, information, or online discussion group only control,

therapist‐supported ICBT versus unguided CBT, and

therapist‐supported ICBT versus face‐to‐face CBT.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risk of bias in each included study using the Cochrane Collaboration’s 'risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011a). We assessed the following six areas for risk of bias.

Sequence generation: was the allocation sequence of participants adequately randomised?

Allocation concealment: was the allocation sequence adequately concealed from participants as well as those involved in the enrolment and assignment of participants?

Blinding: were participants, study personnel, and those assessing outcomes kept unaware of participants’ allocation to a study condition throughout the course of the investigation?

Incomplete outcome data: were there incomplete data for the main or secondary outcomes (e.g., due to attrition)? Were incomplete data adequately addressed?

Selective reporting: was the study free of suggestions of selective reporting of outcomes (e.g., reporting of a subset of outcomes on the basis of the results)?

Other potential threats to bias: was the study free of any other problems (e.g., early stopping, baseline imbalance, cross‐over trials) that could have introduced bias?

We did not assess risk of bias related to therapist experience and qualifications. Evidence in the field as to the impact of therapist experience on treatment outcomes remains mixed (for example, Hahlweg 2001; Andersson 2012; Norton 2014), as such, it would be inappropriate to impose bias on a study based on a characteristic we are unsure would actually introduce bias. In addition, we did not assess risk of bias related to therapist allegiance. This was because: (a) all studies investigated CBT, and (b) it would have been impossible to know if researchers were allied with a particular type of delivery method.

Two review authors (JVO and KMB) independently assessed risk of bias for each included study. We resolved disagreements by consensus and discussion with a third review author (MCW or SHS) where necessary. If further information about a particular trial was required to assess its risk of bias, we contacted the primary investigator of the relevant study. We created 'risk of bias' tables describing the information outlined above, as reported in each study. These tables also include a judgement on the risk of bias, made by the review authors for each of the six areas, based on the following three categories: (1) low risk of bias, (2) high risk of bias, and (3) unclear or unknown risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous outcomes

We analysed our only dichotomous outcome, clinically important improvement in anxiety (yes or no) (as measured by no longer meeting diagnostic criteria on a diagnostic interview, no longer meeting a designated cut‐off on a validated scale, or meeting the criteria for very much or much improved on the CGI) using risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) within studies.

Continuous outcomes

As most studies that were selected for inclusion used different measures to assess sufficiently similar constructs, we compared continuous outcomes (that is, general and disorder‐specific anxiety symptoms, quality of life) by calculating the standardized mean difference (SMD) and its 95% CI. However, when all of the studies within a meta‐analysis used the same measure to assess an outcome (for example, if all studies within a meta‐analysis used the BAI to assess general anxiety symptoms), we compared continuous outcomes by calculating the mean difference (MD) to facilitate the interpretation of the clinical relevance of the findings.

Most included studies used more than one measure to assess each of the continuous outcomes. Thus, a mean score was created across the measures included within each study. Measures of variance for this mean score were created by combining standard deviations across studies according to the method described by Borenstein 2009. This method requires that the correlation between two measures be known; as such, on the rare occasion when this correlation was not known and could not be identified in prior literature the measure in question was excluded from analyses. This occurred in five instances (Klein 2006, Richards 2006, and Kiropoulos 2008 for the Body Vigilance Scale; Andersson 2009 and Andersson 2013 for the Fear Survey Schedule III). A sixth study simply included too many measures to be meaningfully combined (Berger 2014) and so the Brief Symptom Index was used as a proxy to index disorder‐specific symptoms.

To combine measures of quality of life and disability into one outcome, we reversed the scores of the disability measures (that is, by subtracting mean scores from the measure total scores) to align them with the quality of life measures.

Endpoint versus change data

We anticipated that we might encounter some studies that reported analyses based on changes from baseline and other studies that reported analyses based on final values. We planned to present the two types of analysis results in separate subgroups to avoid confusion for readers and, where appropriate, to combine both types of scores in the final results. Despite these plans, none of the included studies reported change data so we used endpoint data in all meta‐analyses.

Skewed data

We dealt with skewed data according to the guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a) and Higgins 2008. In order to conduct the final analysis, transformed or untransformed data had to be obtained for all studies because log‐transformed and untransformed data cannot be combined in meta‐analyses (Higgins 2011a). In the case that a limited number of studies included in one meta‐analysis presented log‐transformed data, we back‐transformed these data and included untransformed data in the meta‐analysis. We then conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding any studies that presented transformed data.

Unit of analysis issues

Parallel group randomised controlled trials (RCTs)

In some parallel group RCTs, participants randomly assigned to a waiting list, attention, information, or online discussion group only control were permitted to pursue the active treatment after their period on the waiting list was complete. To analyse dichotomous and continuous data for these trials, we only included data from participants before they crossed over to their second treatment condition; in other words, only data from the original comparison (waiting list, attention, information, or online discussion group only control versus therapist‐supported ICBT) was used in the meta‐analyses.

Cross‐over trials

When included studies were cross‐over trials, we planned to include only data from the first phase of the trial.

Cluster randomised trials

When cluster randomised trials had accounted for clustering within their analyses (through the use of multilevel modelling or general estimating equations, for example) we planned to include data directly in the meta‐analyses. For studies that failed to appropriately account for clustering, we planned to impute the data based on the number of clusters reported in each intervention group, the size of each cluster, summary statistics, and an estimate of intracluster correlation. We also planned to exclude cluster trials with a high risk of bias (that is, where clustering was not accounted for in analyses) from sensitivity analyses.

Multiple intervention arms

When multiple intervention arms met our inclusion criteria, we planned to combine eligible groups to create a pair‐wise comparison following the procedure outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). We planned to conduct sensitivity analyses excluding any studies with multiple intervention arms that did not report all intervention comparisons.

Dealing with missing data

We used data from ITT analyses whenever they were reported by study authors. In 21 studies, authors employed a LOCF method to address missing data with the assumption that participants who were missing data following randomisation (that is, dropouts) did not respond to treatment. Of the remaining studies, two studies used multiple imputation methods to create ITT data (Kok 2012; van Ballegooijen 2013). Seven studies used a mixed effects models approach in an ITT approach to deal with missing data (Bergstrom 2010; Berger 2011; Hedman 2011; Paxling 2011; Andersson 2012a; Andersson 2012b; Silfvernagel 2012). Two studies did not include ITT data (Andersson 2009; Andersson 2013). One study did not report whether they used ITT data (Greist 2012).

Because included studies did not report individual participant data, if authors did not provide ITT analyses in their manuscript we contacted the primary investigator by e‐mail to attempt to obtain unreported data to permit an ITT analysis. When we did not receive responses from study authors we simply included their reported, non‐ITT, continuous outcome data in the analysis. This was the case for two studies (Andersson 2009; Andersson 2013). For dichotomous outcomes, we were able to impute ITT data by assuming that participants who had dropped out did not meet the target event (that is, clinically important improvement in anxiety). We conducted sensitivity analyses excluding studies for which ITT data were not available (either from the published manuscript or from study authors) to determine the extent to which missing data influenced effect sizes.

If included trials did not provide complete information (that is, group means, standard deviations, and sample size), we contacted the primary investigator by e‐mail to attempt to obtain unreported data. We contacted other study investigators as needed. The only sources for outcome data were the original published report or author correspondence. If standard deviations were not available from the authors, we planned to calculate these using other data reported in the article, including t‐values, CIs, and standard errors. If that was not possible, we planned to impute standard deviations from other investigations using similar measures and populations.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We tested the extent of statistical heterogeneity in meta‐analyses using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2002), which calculates the percentage of variability due to heterogeneity rather than chance. According to the guidelines outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, I2 values may be interpreted as follows:

0% to 40% might not be important;

30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity; and

75% to 100% represents considerable heterogeneity (Higgins 2011a).

We interpreted the importance of these I2 values in consideration of the magnitude and direction of effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (as indexed by the P value from the Chi2 test). If there was evidence of heterogeneity, we first re‐checked the data for accuracy. We considered sources of heterogeneity according to the pre‐specified subgroup and sensitivity analyses listed in Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity.

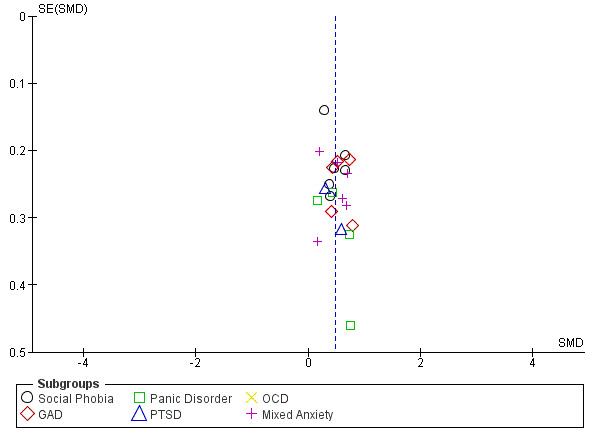

Assessment of reporting biases

Where there were sufficient numbers of trials to make such a plot meaningful (that is, at least 10 included studies (Higgins 2011a)) we constructed funnel plots to determine the possible influence of publication bias. We planned to enhance funnel plots with contour lines delineating areas of statistical significance (as suggested by Peters 2008) to assist in the differentiation of asymmetry due to publication bias or other causes.

Data synthesis

We combined data using an inverse‐variance random‐effects model due to expected variation in the characteristics of the interventions investigated and participant populations. We combined dichotomous outcome measures by computing a pooled risk ratio (RR) and 95% CI. We combined continuous outcomes when means and standard deviations were available. When sufficiently similar continuous outcomes were measured differently across studies we calculated an overall standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI. However, as indicated previously, when outcomes were measured similarly across studies we used a mean difference method. We used the RevMan 5.3 software for data synthesis.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted subgroup analyses but interpreted these with caution due to the risk of false positive conclusions. We planned to perform the following subgroup analyses:

gender of participants;

type of anxiety disorder (i.e., PD with or without agoraphobia, agoraphobia without a history of panic, social phobia (social anxiety disorder), PTSD, acute stress disorder, OCD, specific phobia, GAD, and anxiety disorder not otherwise specified);

amount of therapist contact, designated as low (90 min or less), medium (91 to 299 min), or high (300 min or more);

type of CBT (i.e., BT, CT, or CBT); and

research group (i.e., the laboratory from which the study was generated).

We were not able to conduct a subgroup analysis based on gender of participants as none of the included studies distinguished outcomes based on this participant variable. We also were not able to conduct a subgroup analysis based on type of CBT. Only three studies (Andersson 2009; Kok 2012; Andersson 2013) had a stronger focus on BT, as compared to CT or CBT; and no studies examined a CT‐only intervention. For the final subgroup analysis by research group, seven research groups were identified: a group each in Sweden, Switzerland, and the USA; and two distinct groups in Australia and the Netherlands.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses to determine the extent to which observed pooled effect sizes depend on the quality of the design characteristics of studies. We planned to conduct the following sensitivity analyses:

exclusion of studies with a designation of high risk of bias for one or more of the categories as outlined in Assessment of risk of bias in included studies;

exclusion of cluster randomised trials where clustering was not appropriately accounted for in analysis;

exclusion of studies with multiple intervention arms with selective reporting of intervention comparisons;

exclusion of studies with a somewhat more active waiting list control condition (i.e., attention, information, or online discussion group only control)

exclusion of studies with imputed standard deviations for continuous outcomes;

exclusion of studies with back transformed data for continuous outcomes;

exclusion of studies not reporting: (a) dichotomous, and (b) continuous outcomes according to the ITT principle;

exclusion of studies with continuous outcomes analysed using LOCF; and

assuming treatment dropouts were responders for dichotomous outcomes.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings tables were created to present the main findings of the review. We imported meta‐analytic data from RevMan into GRADEprofiler version 3.6 to create summary of findings tables for each of the three most clinically relevant comparisons: ICBT with therapist support versus waiting list control, ICBT with therapist support versus unguided ICBT, and ICBT with therapist support versus face‐to‐face CBT. The summary of findings tables present meta‐analytic outcomes for each of the continuous and dichotomous outcomes at post‐treatment and summarize the number of studies and participants included in each analysis. In addition, GRADEprofiler allowed us to rate the quality of the evidence for each outcome for each comparison considering: (a) risk of bias, (b) inconsistency, (c) indirectness, (d) imprecision, and (e) publication bias.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies

Results of the search

We screened a total of 1736 citations and selected 38 studies with 3214 participants for inclusion.

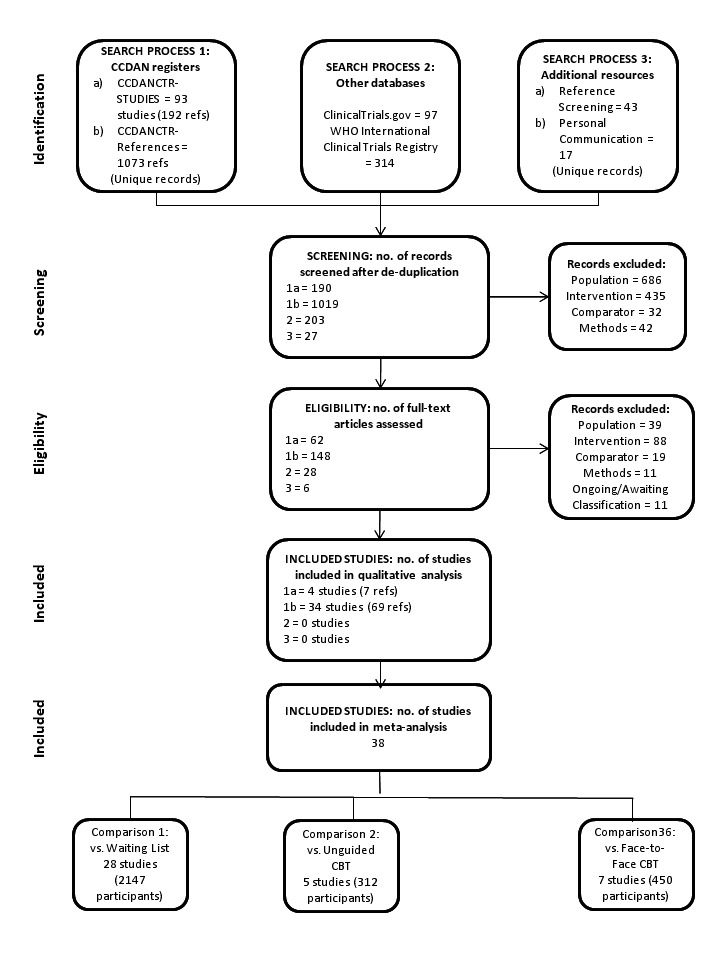

In detail, searches of the CCDANCTR (all years to 16 March 2015) retrieved a total of 1265 records, including manuscripts in peer‐reviewed journals, conference abstracts, and clinical trial registrations. Secondary search methodologies ‐ including searching the reference lists of eligible studies, contacting experts in the field and conducting additional searches of trial registries ‐ identified a further 471 records. After de‐duplication and following a brief screening of the titles and abstracts, 244 full‐text articles were retrieved for a more detailed evaluation of eligibility.

The PRISMA flow diagram shown in Figure 1 outlines the study selection process and broad reasons for exclusion. Studies were excluded if: (a) participants did not meet diagnostic criteria for an anxiety disorder, as assessed by study authors (population), (b) the intervention of interest was not ICBT, did not involve a therapist, or included too much face‐to‐face therapist contact (intervention), (c) the comparator was not appropriate given our selection criteria (comparator), (d) the trial was not randomised or did not use adequate diagnostic measures (methods), or (e) the trial was ongoing (ongoing). After consolidating references into studies, 38 were eligible for inclusion in the meta‐analyses.

1.

PRISMA diagram of the search process.

E‐mail correspondence for supplemental data was exchanged with Dr Tomas Furmark (Furmark 2009a; Furmark 2009b), Dr Per Carlbring (Carlbring 2001; Carlbring 2006; Carlbring 2007; Carlbring 2011), Dr Nickolai Titov (Titov 2008a; Titov 2008b; Titov 2008c; Titov 2009; Titov 2010; Titov 2011), Dr Britt Klein (Klein 2006; Richards 2006; Kiropoulos 2008), Dr Wouter van Ballegooijen (van Ballegooijen 2013), Dr. Thomas Berger (Berger 2014), and Dr. Jill Newby (Newby 2013).

Included studies

See Characteristics of included studies for details of individual studies and Table 4 for a summary table of the characteristics of the included studies.

1. Summary of included studies table.

| Study | Diagnosis and Co‐morbidity |

Participant Characteristics (M age, age range, sex, country of residence) |

Co‐Use of Medication | N |

Intervention Type & Therapist Duration Contact |

Comparison | Assessment Points | Outcomes | |

| Andersson et al (2009) |

Specific Phobia, Spider Type co‐morbidity not reported |

M age=25.6 (4.1) 18‐65 years 84.8% women Sweden |

Not reported | 27 | IBT with email: 4 wks; 5 online modules | M total time spent per participant = 25 min | Orientation and 1 3‐hour live exposure session | post‐treatment 12‐month follow‐up |

specific phobia sx; general anxiety sx |

| Andersson et al (2012a) |

Social Phobia co‐morbidity included but not reported |

ICBT M age=38.1 (11.3) WLC M age=38.4 (10.9) 19‐71 years 61% women Sweden |

13.7% using medication | 204 | ICBT with email: 9 wks; 9 online modules | M time spent per participant per week = 15 min | Online Discussion Group | post‐treatment | diagnostic status; social phobia sx; QOL; general anxiety sx; |

| Andersson et al (2012b) |

GAD 22.2% Social Phobia, 19.8% PD, 3.7% OCD, 23.5% MDD |

ICBT M age=44.4 (12.8) IPDTM age=36.4 (9.7) WLC M age=39.6 (13.7) 19‐66 years 76.5% women Sweden |

32.1% using medication | 81 | ICBT with email: 8 wks; 8 online modules | M total time spent per participant = 92 min (SD=61) | (1) Waiting List Control (2) IPDT: 8 wks; 8 online modules |

post‐treatment | diagnostic status, GAD sx; general anxiety sx; QOL |

| Andersson et al. (2013) |

Specific Phobia, Snake Type comorbidity not reported |

M age=27.2 (8.1) 19‐54 years 84.6% women Sweden |

Not reported | 30 | IBT with email: 4 wks; 4 online modules | M total time spent per participant = 25 min | Orientation and 1 3‐hour live exposure session | post‐treatment 12‐month follow‐up |

specific phobia sx; general anxiety sx |

| Berger et al (2009) |

Social Phobia 26.9% co‐morbid Axis I disorder |

M age=28.9 (5.3) 19‐43 years 44.2% women Switzerland, France, Belgium |

Excluded | 52 | ICBT with email: 10 wks; 5 online modules |

M=5.5 emails from participant weekly emails from therapist |

Waiting List Control | post‐treatment | social phobia sx; treatment satisfaction |

| Berger et al (2011) |

Social Phobia 38% co‐morbid Axis I disorder; 12% PD, 10% Specific Phobia, 2% GAD, 22% MDD/Dysthymia, 2% ED |

M age=37.2 (11.2) 19‐62 years 53.1% women Switzerland |

7.4% using medication | 81 | ICBT with email: 10 wks; 5 online modules |

M=6.16 (SD=4.56; range=1‐17) emails from participant M=12.44 (SD=2.85; range=6‐17) emails from therapist |

(1) Unguided ICBT 10 weeks; 5 online modules (2) Step‐up on demand ICBT |

post‐treatment 6‐month follow‐up |

diagnostic status; social phobia sx; treatment satisfaction |

| Berger et al. (2014) |

33.3% PD with or without Agoraphobia 85.6% Social Phobia 25% GAD 37.1% PD with or without Agoraphobia, Social Phobia, or GAD, 13.6% MDD, 15.9% Specific Phobia, 5.3% OCD, 12.1% other Axis I disorder |

M age=35.1 (11.4) 18‐65 years 56.1% women Switzerland, Germany, Austria |

14.4% using medication | 132 | ICBT with email: 8 wks; 8 online modules |

M=6.53 (SD=7.2; range=0‐36) emails from participant M=12.6 (SD=4.6; range=8‐35) emails from therapist |

(1) Waiting List Control (2) Tailored ICBT: 8 wks; 8 online modules |

post‐treatment 6‐month follow‐up |

diagnostic status; anxiety sx; general anxiety sx; treatment satisfaction |

| Bergstrom et al (2010) |

15.4% PD 84.6% PD with Agoraphobia co‐morbidity not reported |

ICBT M age=33.8 (9.7) GCBT M age=34.6 (9.2) 18 years or older 61.5% women Sweden |

45% using medication; 34% SSRI/SNRIs, 13% BZ, 24% BZ derivatives or neuroleptics; 5% TCAs | 104 | ICBT with email: 10 wks; 10 online modules |

M=11.3 (SD=4.3) emails from therapist M total time spent per participant = 35.4 min (SD=19) |

10 weekly 2‐hour sessions of GCBT | post‐treatment 6 month follow‐up |

diagnostic status; PD sx; QOL |

| Carlbring et al (2001) |

PD co‐morbidity included but not reported |

M age=34 (7.5) 21‐51 years 71% women Sweden |

64% using medication; 44% SSRIs, 10% BZ, 5% TCAs, 5% beta‐blockers | 41 | ICBT with email: 7‐12 wks; 6 online modules |

M reciprocal emails = 7.5 (SD=1.2; range=6‐15) M total time spent per participant = 90 min |

Waiting List Control | post‐treatment | diagnostic status; PD sx; QOL; general anxiety sx; treatment satisfaction |

| Carlbring et al (2005) |

49% PD 51% PD with Agoraphobia 49% Anxiety Disorder; 6% MDD |

M age=35.0 (7.7) 18‐60 years old 71% women Sweden |

30.6% SSRIs, 8.2% BZ, 6.1% TCAs, 6.1% beta blockers | 49 | ICBT with email: 10 wks; 10 online modules |

M reciprocal emails =15.4 (SD=5.5; range=4‐31) M total time spent per participant =150 min |

10 weekly 45‐60 min sessions of individual CBT | post‐treatment 12‐month follow‐up |

diagnostic status; PD and agoraphobia sx; general anxiety sx; QOL |

| Carlbring et al (2006) |

PD co‐morbidity included but not reported |

M age=36.7 (10) 18‐60 years 60% women Sweden |

54% using medication | 60 | ICBT with email & phone: 10 wks; 10 online modules |

M reciprocal contacts = 13.5 (SD =4.4; range=7‐29) M time spent per participant per week = 12 min M length phone call = 11.8 min (range= 9.6‐15.6) |

Waiting List Control | post‐treatment | diagnostic status; PD and agoraphobia sx; general anxiety sx; QOL; treatment satisfaction |

| Carlbring et al (2007) |

Social Phobia co‐morbidity included but not reported |

ICBT M age=32.4 (9.1) WLC M age=32.9 (9.2) 18‐60 years 64.9% women Sweden |

Included but not reported | 60 | ICBT with email & phone: 9 wks; 9 online modules |

M time spent per participant per week = 22 min M length phone call = 10.5 min (SD= 3.6) |

Waiting List Control | post‐treatment | social phobia sx; general anxiety sx; QOL |

| Carlbring et al (2011) |

9% PD 22% PD with Agoraphobia 39% Social Phobia 20% GAD 13% ADNOS 2% OCD, 2% PTSD, 20% MDD, 7% mild depression; 15% Dysthymia |

M age=38.8 (10.7) 22‐63 years 76% women Sweden |

26% using an antidepressant or anxiolytic | 54 | ICBT with email: 10 wks; 6‐10 online modules | M time spent per participant per week = 15 min | Attention Control 10 wks of posts in an online support forum |

post‐treatment | diagnostic status; anxiety sx (broadly); QOL; general anxiety sx |

| Furmark et al (2009a) |

Social Phobia co‐morbidity not reported |

ICBT M age=35 (10.2) WLC M age=35.7 (10.9) Bib M age=37.7 (10.3) 18 years or older 67.5% women Sweden |

13.9% using medication | 120 | ICBT with email: 9 wks; 9 online modules | M time spent per participant per week = 15 min | (1) Biblio‐therapy: 9 wks; 9 lessons (2) Waiting List Control |

post‐treatment | social phobia sx; general anxiety sx; QOL |

| Furmark et al (2009b) |

Social Phobia co‐morbidity not reported |

ICBT M age=34.9 (8.4) Bib M age=32.5 (8.5) Applied Relaxation M age=36.4 (9.8) 18 years or older 67.8% women Sweden |

6.7% using medication | 115 | ICBT with email: 9 wks; 9 online modules | M time spent per participant per week = 15 min | (1) Biblio‐therapy: 9 wks; 9 lessons (2) Biblio‐therapy and discussion group: 9 wks; 9 lessons (2) Internet‐based applied relaxation: 9 wks; 9 online modules |

post‐treatment | social phobia sx; general anxiety sx; QOL |

| Greist et al. (2012) |

OCD 32% Anxiety Disorder, 31% Mood Disorder, 7% Substance Disorder, 7% ADHD, 2% ED |

M age=38.34 (13.93) 18 years or older 63% women USA |

19.5% using medication | 87 | ICBT with phone: 12 wks; 9 online modules | Weekly phone calls | (1) Unguided ICBT: 12 wks; 9 online modules (2) Lay Coaching ICBT: 12 wks; 9 online modules |

post‐treatment | OCD sx; QOL; treatment satisfaction |

| Hedman et al (2011) |

Social Phobia 47.5% Anxiety Disorder, 15.1% MDD |

ICBT M age=35.2 (11.1) GCBT M age=35.5 (11.6) 18‐64 years 35.7% women Sweden |

19.8% SSRIs, 4.8% SNRIs | 126 | ICBT with email: 15 wks; 15 online modules |

M=17.4 emails per participant M time spent per participant per week = 5.5 min (SD=3.6) |

15 weekly 2.5‐hour sessions of GCBT | post‐treatment 6 month follow‐up |

diagnostic status; social phobia sx; QOL; general anxiety sx |

| Ivarsson et al. (2014) |

PTSD comorbidity not reported |

M age=46 (11.7) 21‐67 years 82.3% women Sweden |

Included but not reported | 62 | ICBT with email: 8 wks; 8 online modules | M time spent per participant per week = 28 min (SD=19.8) | Attention Control: sent weekly question on wellbeing, stress, sleep | post‐treatment | diagnostic status; PTSD sx; general anxiety sx; QOL |

| Johnston et al (2011) |

20.6% PD with or without Agoraphobia 34.4% Social Phobia 45% GAD 29% Anxiety Disorder, 9.2% Affective Disorder, 32.1% both disorders |

M age=41.62 (12.83) 19‐79 years 58.8% women Australia |

29% using medication | 139 | ICBT with email & phone: 10 wks; 8 online modules |

M=8.83 (SD=3.29) emails per participant M=7.54 (SD=2.43) phone calls per participant M total time spent per participant = 69.09 min (SD=32.29) |

Waiting List Control | post‐treatment | disorder‐specific sx; general anxiety sx; QOL; treatment satisfaction |

| Kiropoulos et al (2008) |

41.9% PD 58.1% PD with Agoraphobia 72.1% co‐morbid Mood, Anxiety, Somatoform, or Substance Disorder |

M age=38.96 (11.13) 20‐64 years 72.1% women Australia |

47.7% using medication | 86 | ICBT with email: 6 wks, 6 required & 2 optional online modules |

M=18.24 (SD=9.82) emails from therapist M=10.64 (SD=8.21) emails from participant M total time spent per participant = 352 min (SD=240) |

12 weekly 1‐hour sessions of individual CBT | post‐treatment | diagnostic status; PD and agoraphobia sx; general anxiety sx; QOL; treatment satisfaction |

| Kok et al. (2012) |

41% PD with Agoraphobia 17% Agoraphobia 53.3% Social Phobia 83.5% Specific Phobia Comorbidity included but not reported |

M age=34.6 (11.7) 18 years or older 61% women Netherlands |

43% using medication | 212 | IBT with email: 5wks, 8 online modules | weekly contact by therapist | Waiting List Control: also sent self‐help book without instructions | post‐treatment | phobia sx; general anxiety sx; treatment satisfaction |

| Newby et al. (2013) |

84% GAD Comorbidity included but not fully reported; 56% MDD |

M age=44.3 (12.2) 21‐80 years 77.8% women Australia |

40.4% using medication | 100 | ICBT with email and phone: 10 wks; 6 online modules | M total time spent per participant = 23.37 min (SD=12.15) | Waiting List Control | post‐treatment | GAD sx; QOL; treatment satisfaction |

| Nordgren et al. (2012) |

31% PD with or without Agoraphobia 8% Agoraphobia 32% Social Phobia 10% GAD 19% ADNOS 21% Anxiety Disorder, 43% Mood Disorder, 1% Hypochon‐driasis |

ICBT M age=35 (13) WLC M age=36 (12) 19‐68 years 63% women Sweden |

26% using medication | 100 | ICBT with email: 10 wks; 7‐10 online modules | M time spent per participant = 15 min/week | Attention Control: sent weekly questions on wellbeing | post‐treatment | anxiety sx; general anxiety sx; QOL |

| Paxling et al (2012) |

GAD co‐morbidity included but not fully reported; 22.5% MDD |

M age=39.3 (10.8) 18‐66 years 79.8% women Sweden |

37.1% using medication | 89 | ICBT with email: 8 wks; 8 online modules | M total time spent per participant = 97 min (SD=52) | Waiting List Control | post‐treatment | GAD sx; general anxiety sx; QOL |

| Richards et al (2006) |

21.9% PD 78.1% PD with Agoraphobia 22% Social Phobia, 13% GAD, 9% Specific Phobia, 6% PTSD, 9% MDD, 6% Hypochondriasis, 3% Somatization |

M age=36.59 (9.9) 18‐70 years 68.8% women Australia |

15.6% anti‐depressants, 12.5% BZ, 9.4% antidepressants and BZ | 23 | ICBT with email: 8 wks, 6 online modules |

M=18 (SD=6.5) emails from therapist M=15.3 (SD=12.8) emails from participant M total time spent per participant =376.3 min (SD=156.8) |

Information Only Control Weekly status updates to clinician and access to online non‐CBT info |

post‐treatment | diagnostic status; PD and agoraphobia sx; general anxiety sx; QOL |

| Robinson et al (2010) |

GAD co‐morbidity included but not reported |

M age=46.96 (12.7) 18‐80 years 68.3% women Australia |

Included but not reported | 101 | ICBT with email and phone: 10 wks; 6 online modules |

M =33.2 (SD=4) emails/calls per participant M total time spent per participant = 80.8 min (SD=22.6) |

Waiting List Control | post‐treatment | diagnostic status; GAD sx; QOL; treatment satisfaction |

| Silfvernagel et al (2012) |

7% PD 83% PD with Agoraphobia 16% Social Phobia 19% GAD 2% ADNOS 32% co‐morbid disorder |

M age=32.4 (6.9) 20‐45 years 65% women Sweden |

47% using medication | 57 | ICBT with email: 8 wks; 6‐8 online modules | M time spent per participant = 15 min/week | Waiting List Control | post‐treatment | diagnostic status; PD sx; general anxiety sx; QOL |

| Spence et al (2011) |

PTSD 62% MDD, 33% Social Phobia, 31% PD with or without Agoraphobia, 26% GAD; 17% OCD |

M age=42.6 (13.1) 21‐68 years 81% women Australia |

60% using medication | 44 | ICBT with email & phone: 8 wks; 7 online modules |

M=5.39 (SD=3.54) emails per participant M=7.87 (SD=2.56) phone calls per participant M total time spent per participant = 103.91 min (SD=96.53) |

Waiting List Control | post‐treatment | diagnostic remission; PTSD sx; QOL; general anxiety sx; treatment satisfaction |

| Tillfors et al (2008) |

Social Phobia co‐morbidity included but not reported |

ICBT M age=32.3 (9.7) ICBT+exposure M age= 30.4 (6.3) 19‐53 years 78.9% women Sweden |

Included but not reported | 38 | ICBT with email: 9 wks; 9 online modules | M=35 min per participant per week | ICBT with email (9 online modules) + 5 live 2.25‐hour exposure sessions; 9 wks | post‐treatment 12‐month follow‐up |

social phobia sx; general anxiety sx; QOL; treatment satisfaction |

| Titov et al (2008a) |

Social Phobia co‐morbidity included but not reported |

M age=38.13 (12.24) 18‐72 years 59% women Australia |

29% using medication | 105 | ICBT with email: 10 wks; 6 online modules | M total time spent per participant = 125 min (SD=25) | Waiting List Control | post‐treatment | social phobia sx; QOL; treatment satisfaction |

| Titov et al (2008b) |

Social Phobia co‐morbidity included but not reported |

M age=36.79 (10.93) 20‐61 years 62.96% women Australia |

25.9% using medication | 88 | ICBT with email: 10 wks; 6 online modules | M total time spent per participant = 126.76 min (SD=30.89) | Waiting List Control | post‐treatment | social phobia sx; QOL; treatment satisfaction |

| Titov et al (2008c) |

Social Phobia co‐morbidity included but not reported |

M age=37.97 (11.29) 18‐64 years 61.05% women Australia |

25.9% using medication | 98 | ICBT with email: 10 wks; 6 online modules | M total time spent per participant = 168 min (SD=40) | (1) Unguided ICBT 10 wks; 6 online modules (2) Waiting List Control |

post‐treatment | social phobia sx; QOL; treatment satisfaction |

| Titov et al (2009) |

GAD co‐morbidity included but not reported |

M age=44 (12.98) 18 years or older 76% women Australia |

29% using medication | 48 | ICBT with email & phone: 9 wks, 6 online modules |

M =23.7 emails, 5.5 instant messages, and 4.1 calls per participant M total time spent per participant = 130 min |

Waiting List Control | post‐treatment | diagnostic status; GAD sx; QOL; treatment satisfaction |

| Titov et al (2010) |

26.9% PD with Agoraphobia 29.5% Social Phobia 43.6% GAD 28.2% Anxiety Disorder, 20.5% Affective Disorder, 26.9% both disorders |

M age=39.5 (13) 18 years or older 67.9% women Australia |

47.4% using medication | 86 | ICBT with email & phone: 8 wks; 6 online modules |

M =23.6emails from therapist M total time spent per participant = 46 min (SD=16) |

Waiting List Control | post‐treatment | diagnostic status; disorder‐specific anxiety sx; QOL; treatment satisfaction |

| Titov et al (2011) |

10% PD with or without Agoraphobia 11% Social Phobia 28% GAD 51% MDD 81% had a co‐morbidity |

M age=43.9 (14.6) 18‐79 years 73% women Australia |

54% using medication | 74 | ICBT with email & phone: 10 wks; 8 online modules |

M=5.45 (SD=3.57) emails per participant M=9.35 (SD=2.96) phone calls per participant M total time spent per participant = 84.76 min (SD=50.37) |

Waiting List Control | post‐treatment | disorder‐specific sx; general anxiety sx; QOL; treatment satisfaction |

| Van Ballegooijen et al (2013) |

78% PD with or without Agoraphobia 14% Agoraphobia co‐morbidity included but not reported |

M age=36.6 (11.4) 18‐67 years 67.5% women Netherlands |

Included but not reported | 126 | ICBT with email: 12 wks; 6 online modules | M total time spent per participant = 1 to 2 hours | Waiting List Control | post‐treatment | PD sx; general anxiety sx |

| Wims et al (2010) |

PD with or without Agoraphobia 21% Social Phobia, 31% GAD, 10% OCD, 7% PTSD, 21% MDD |

M age=42.08 (12.29) 18 years or older 76% women Australia |

31% using medication | 59 | ICBT with email: 8 wks; 6 online modules |

M =7.5 emails from therapist M total time spent per participant = 75 min |

Waiting List Control | post‐treatment | diagnostic status; PD & agoraphobia sx; QOL |

| Wootton et al. (2013) |

OCD 26.9% Social Phobia, 40.4% GAD, 15.4% PD, 11.5% PTSD, 38.5% MDD |

ICBT M age=39.93 (12.57) Bib M age=35.55 (9.68) WLC M age=38.58 (10.51) 18‐64 years 75% women Australia |

61.5% using SSRIs | 56 | ICBT with phone: 8 wks, 5 online modules |

M=15.05 (SD=3.93) phone calls per participant M total time spent per participant = 88.63 min (SD=46.41) |

1) Guided bibliotherapy: 8 wks, 5 lessons 2) Waiting List Control |

post‐treatment | diagnostic status; OCD sx; general anxiety sx; treatment satisfaction |

Notes: All data in the above table represent only that included in/relevant to the present review.

ADNOS = anxiety disorder, not otherwise specified; Bib = Bibliotherapy; BZ = benzodiazepine; ED = eating disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; GCBT = group cognitive behavioural therapy; IBT = internet‐based behavioural therapy; ICBT = internet‐based cognitive behavioural therapy; IPDT = internet‐based psychodynamic therapy; MDD = major depressive disorder; PD = panic disorder; QOL = quality of life; SNRI = serotonin‐norepinephrine re‐uptake inhibitor; SSRI = selective serotonin re‐uptake inhibitor; sx = symptoms; TCA = tricyclic antidepressant; VCBT = videoconferencing cognitive‐behavioural therapy; WLC = waiting list control.

Design

All of the 38 included studies were parallel group RCTs. For studies in which participants in the waiting list, attention, information, or online discussion group only control were given the opportunity to complete the treatment after their time on the waiting list, only data from the original comparison were used in the meta‐analyses. There were no cross‐over or cluster randomised trials.

Ten studies included multiple intervention arms: two (Titov 2008c; Furmark 2009a) compared the intervention of interest to two eligible comparators (a waiting list, and unguided CBT) so were included in multiple meta‐analyses (ICBT versus waiting list control, and ICBT versus unguided CBT), and eight (Richards 2006; Furmark 2009b; Robinson 2010; Berger 2011; Johnston 2011; Berger 2014; Greist 2012; Kok 2012) included a third treatment arm not relevant to the present review.

Sample sizes

Sample sizes of included studies ranged from 21 (12 in the intervention arm, 9 in the comparator arm (Richards 2006)) to 212 participants (105 in the intervention arm, 107 in the comparator arm (Kok 2012)). The average study sample size was 85 participants. In most studies there was an equal distribution of participants between the treatment and control arms. Only 2 studies had < 30 participants, 16 studies had 30 to 60 participants, 9 studies had 60 to 90 participants, and 9 studies had 90 to 140 participants, with 2 outliers at 204 participants (Andersson 2012a) and 212 participants (Kok 2012).

Setting

Included studies came from one research group in Sweden (18 trials), two groups in Australia (Klein et al.: 2 trials; Titov et al.: 12 trials), two groups in the Netherlands (Kok et al.: 1 trial; van Ballegooijen et al.: 1 trial), a research group in Switzerland (3 trials), and one in the USA (1 trial).