Abstract

Context

This study was designed to understand causes and critical periods for postpartum weight retention by characterizing changes in body composition, energy intake, energy expenditure and physical activity in women with obesity during pregnancy and postpartum.

Design

In this prospective, observational cohort study, body composition (plethysmography), energy expenditure (doubly labeled water, whole-body room calorimetry), physical activity (accelerometry), metabolic biomarkers, and eating behaviors were measured. Energy intake was calculated by the intake-balance method for pregnancy, and for 2 postpartum periods (0 to 6 months and 6 to 12 months).

Results

During the 18-month observation period, weight loss occurred in 16 (43%) women (mean ± SEM, −4.9 ± 1.6 kg) and weight retention occurred in 21 (57%) women (+8.6 ± 1.4 kg). Comparing women with postpartum weight loss and weight retention, changes in body weight were not different during pregnancy (6.9 ± 1.0 vs 9.5 ± 0.9 kg, P = 0.06). After pregnancy, women with postpartum weight loss lost −3.6 ± 1.8 kg fat mass whereas women with weight retention gained 6.2 ± 1.7 kg fat mass (P < 0.001). Women with postpartum weight loss reduced energy intake during the postpartum period (compared with during pregnancy) by 300 kcal/d (1255 kJ/d), while women with weight retention increased energy intake by 250 kcal/d (1046 kJ/d, P < 0.005). There were no differences in the duration of breastfeeding, eating behavior, or metabolic biomarkers.

Conclusions

Postpartum weight gain was the result of increased energy intake after pregnancy rather than decreased energy expenditure. Dietary intake recommendations are needed for women with obesity during the postpartum period, and women should be educated on the risk of overeating after pregnancy.

Keywords: diet quality, energy intake, food photography, metabolic rate, physical activity, postpartum weight loss

Pregnancy is a strong determinant of long-term weight gain and obesity in midlife women (1). One in every 2 women with obesity fails to return to pre-pregnancy weight (2, 3) and experiences postpartum weight retention (PPWR). PPWR increases the risks for abdominal visceral adiposity (4, 5) and the development of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease in later life (6, 7).

In contrast to women of healthy body weight, gestational weight gain in women with obesity poorly predicts weight changes postpartum (1, 2, 5, 8, 9). This suggests that PPWR is determined by changes in body weight after pregnancy, but not during pregnancy. In line with these findings, prenatal interventions reducing gestational weight gain are not sufficient to prevent PPWR (10, 11). Defining the best period for intervention requires prospective studies of weight changes across the continuum of pregnancy and postpartum periods including assessments of the causes of weight gain.

Weight gain is a function of a prolonged energy imbalance where energy intake exceeds energy expenditure (or energy needs) (12, 13). Thus, an evaluation of the changes in energy requirements from pregnancy to postpartum—for example, the reduction in metabolic rate after delivery, the recovery from low physical activity during pregnancy, and the energy cost of lactation—will inform postpartum guidance on dietary energy intake for women with obesity. Evidence-based dietary and physical activity guidance specific to women with obesity promises to assist more women in returning to pre-pregnancy weight and improving health status. Furthermore, postpartum weight loss will induce health improvements prior to conception of subsequent pregnancies and thereby lower risks for future pregnancy complications.

The aim of this prospective, observational study in women with obesity was to understand the influence of energy intake and energy expenditure (including physical activity) during pregnancy and postpartum on the body weight trajectory during the first 12 months after delivery. Energy intake was calculated by the energy intake-balance method as sum of total daily energy expenditure and changes in body composition, using doubly labeled water and air displacement plethysmography, respectively. Secondary aims of this study were to identify potential metabolic and behavioral determinants of weight gain and food intake, including glucose homeostasis, diet quality, and eating behaviors. Plasma samples were collected, and diet quality was assessed by food photography, energy expenditure by room calorimetry, and physical activity using accelerometry. Consistent with epidemiological studies of PPWR in women with obesity (2, 3), we hypothesized that 50% of women would not return to early pregnancy weight (> 15 weeks) due to continued positive energy balance which is the result of an increased energy intake from pregnancy and failure of physical activity to fully rebound after pregnancy.

Subjects and Methods

Study design

This is a nested, prospective, observational cohort study, in which 37 pregnant women with obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) from 6 to 15 weeks gestation were followed until 12 months after delivery. The study was approved by the institutional ethical review board of Pennington Biomedical Research Center. The procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible institutional or regional committee on human experimentation and in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in 1983. Women with diabetes (HbA1c ≥ 6.5%) or hypertension (≥160/110 mmHg) or using recreational or prescribed medication that may affect body weight, energy intake, or expenditure were excluded. Women who developed preeclampsia, and hence weight gain by edema, were followed but excluded from the analyses.

Women were classified on the basis of postpartum weight retention (PPWR) and postpartum weight loss (PPWL), which were defined on the basis of the change in body weight from early pregnancy (13–16 weeks gestation) until 12 months postpartum (48–56 weeks). Outcomes were measured at 13–16 weeks (early), 24–27 weeks (mid) and 35–37 weeks (late) of pregnancy and postpartum at 24–28 weeks (6 months) and 48–56 weeks (12 months) after delivery. Body weight, body composition, and metabolic biomarkers were assessed at each time point in the morning after an overnight fast. Sedentary and total daily energy expenditure were assessed during an overnight stay in the inpatient clinic and over the next 7 days, respectively, at early and late pregnancy as well as at 12 months postpartum. During the entire 18-month study, women were reminded to weigh weekly using a provided electronic scale (BodyTrace Inc., New York, NY; accuracy: ±100 g), which automatically transmitted weights to the investigators.

Body composition was assessed using air displacement plethysmography (BodPod, COSMED USA, Inc., Concord, CA). In pregnancy, body volume was adjusted by pregnancy-associated changes in thoracic gas volume of −100 mL per trimester (14), and fat mass (FM) was the difference between weight and fat-free mass (FFM) after adjusting for changes in hydration (15). Estimates of FFM hydration were validated against measured FFM hydration at all assessments (difference ± SD between measured and predicted FFM hydration; early pregnancy: 0.1 ± 0.1 kg, late pregnancy: 0.1 ± 0.1 kg, postpartum: 0.1 ± 0.2 kg).

Energy intake was calculated as the sum of total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) and changes in energy stores by the energy intake-balance method (16). To determine energy intake during pregnancy, energy expenditure was calculated as the mean of TDEE measured early and late pregnancy, and changes in energy stores as changes in FM and FFM from early to late pregnancy, assuming densities of 9500 kcal (39.7 MJ) per kg FM and 771 kcal (3.2 MJ) per kg FFM (16, 17). To determine energy intake postpartum, TDEE at 12 months postpartum was used and the changes in energy stores were calculated as change in FM and FFM from late pregnancy to 6 months postpartum and from 6 to 12 months. At birth, FFM was determined to be reduced by 8 kg (3.5 kg baby, 0.6 kg placenta, 4.2 L water (13), 0.3 kg FFM retained). This was based on the cohort mean values for birth weight (obtained by chart abstraction) and placenta weight and total body water measured in the study. The change in FFM postpartum was the difference between the FFM at birth and FFM measured at 6 and 12 months postpartum.

TDEE was measured over 7 days using doubly labeled water (13, 18). Sedentary energy expenditure was measured in a room calorimeter overnight and metabolic rate calculated during sleep (sleep energy expenditure [SleepEE], 0200-0500h) and upon waking (resting metabolic rate [RMR], 0615-0645h) (18). Energy expenditure (EE) is reported relative to body composition (19) using linear regression of postpartum data (adjusted EE = [a + (b × FFM) + (c × FM)]). Metabolic (RMR) and behavioral adaptations (TDEE) were calculated (Residual EE = Measured EE − Adjusted EE).

Physical activity level (PAL) was calculated as TDEE divided by RMR. Physical activity was also measured by a wrist-worn accelerometer (ActiGraph GT3X+, Pensacola, FL) over 6 days during the doubly labeled water assessment. Accelerometry data were analyzed using the ActiLife software (ActiLife v6.12.0, ActiGraph, Pensacola, FL). Physical activity was expressed as ENMO (Euclidean norm − 1) which is the main summary measure of acceleration. The value presented is the average ENMO over all the available data normalized per 24-hour cycles (diurnal balanced).

Diet quality was assessed using the SmartIntake food photography application (20). Food and food waste images were captured during the 7-day doubly labeled water assessment, which was guided by personalized prompts. Quality control measures ensured that only days during which energy intake was > 60% TDEE (to objectively indicate underreporting) were included in analyses (20). Diet quality was determined from macronutrient composition and the Healthy Eating Index 2015 (21). Validated, self-report questionnaires were used to evaluate eating behavior, food cravings, and mindful eating behavior (22). Breastfeeding duration was self-reported.

Blood was drawn in the morning following an overnight fast to measure glucose (Beckman DXC600, Beckman Coulter Inc, Brea, CA), insulin (Immulite 2000, Siemens, Broussard, LA), cholecystokinine (Cusabio Technology LLC, Houston, TX), leptin, ghrelin, and polypetide-YY (Millipore, Temecula, CA). Insulin sensitivity was calculated as homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR). At 12 months postpartum, a 2-hour oral glucose tolerance-test (75 g glucose) was performed and Matsuda-index and Stumvoll-index calculated.

Statistical analyses

Data are reported as mean ± SEM. For group-comparisons, we used linear mixed models with group (PPWR, PPWL) as between-subject factor and age as covariate. Differences between groups were considered statistically significant, if the interaction-term group × time was P < 0.05. All analyses were carried out by biostatistician (R.A.B.) using SAS/STAT software, Version 9.4 of the SAS System for Windows (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC).

Results

Patients

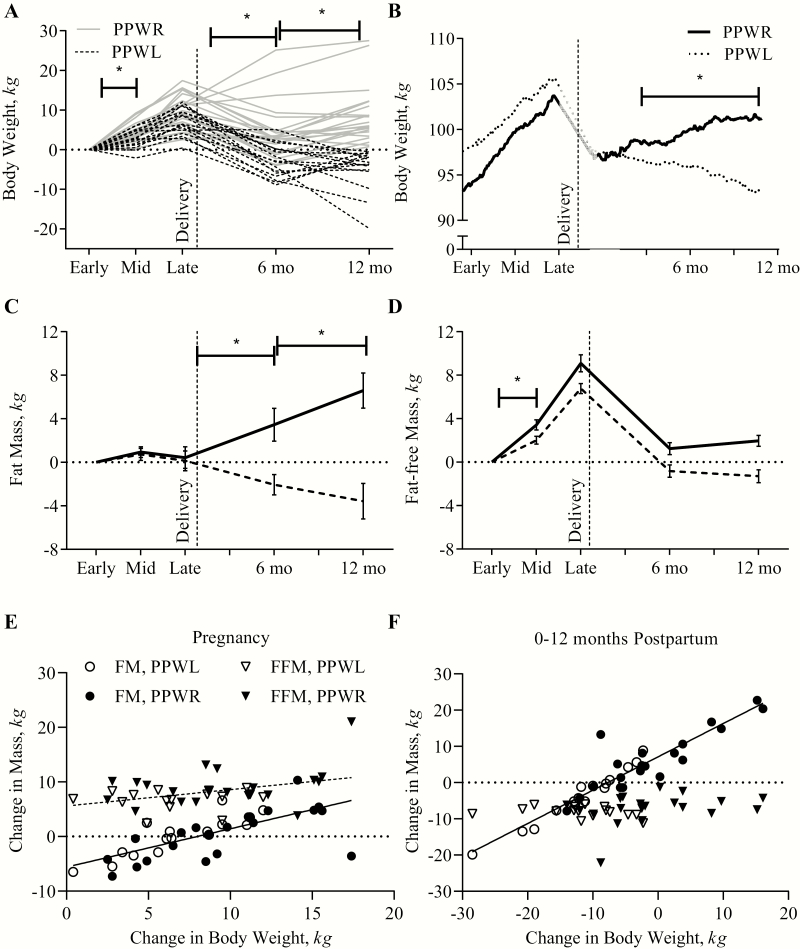

Thirty-seven women with obesity were studied from early pregnancy until 12 months postpartum (Table 1). As shown (Fig. 1A), changes in body weight ranged from +0.4 to +17.4 kg from early pregnancy (14.8 ± 0.1 weeks) until late pregnancy (35.9 ± 0.1 weeks) and from −28.5 kg to +16.5 kg from early pregnancy until 12 months postpartum (11.6 ± 0.2 months). On average, 8.2 ± 0.7 kg body weight was gained from early to late pregnancy, 6.4 ± 1.3 kg was lost postpartum, resulting in a 1.8 ± 1.1 kg gain from early pregnancy until 12 months postpartum.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| PPWL n = 16 | PPWR n = 21 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race, n (White, AA, Other, Asian) | 10, 4, 1, 1 | 10, 9, 2, 0 | 0.45 |

| Parity, n (0, 1, ≥2) | 4, 9, 3 | 12, 6, 3 | 0.12 |

| Age, years | 30.7 ± 1.1 | 26.6 ± 0.9 | 0.007 |

| Body Mass Index, kg/m2 | 35.7 ± 1.2 | 36.4 ± 0.9 | 0.60 |

| HbA1c, % | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 5.2 + 0.1 | 0.07 |

| Body Fat, % | 45.0 ± 1.3 | 45.5 ± 0.8 | 0.74 |

| Gestational Weight Gain, kg | 6.9 ± 0.8 | 9.5 ± 1.0 | 0.06 |

| Gestational Weight Gain, n (INA, REC, EXS) | 3, 2, 11 | 2, 3, 16 | 0.72 |

| Gestational Age at Delivery, weeks | 39.9 + 0.2 | 39.5 + 0.2 | 0.34 |

| Breastfeeding Duration, weeks | 29 ± 6 | 30 ± 5 | 0.92 |

| Education, n (High School, College, Postgraduate) | 2, 10, 4 | 2, 13, 6 | 0.71 |

| Employment, n (fulltime, part-time, none, medically disabled) | 8, 5, 3, 0 | 12, 3, 5, 1 | 0.70 |

| Poverty-Income-Ratio | 4.2 ± 0.7 | 3.7 ± 0.6 | 0.55 |

Data are reported as mean ± SEM or as frequency. Poverty-Income-Ratio was calculated as household income divided by the poverty thresholds as defined by the United States Census Bureau in 2018. Gestational weight gain is classified as inadequate (INA, <170 g/week), recommended (REC, 170–270 g/week) or excess (EXS, >270 g/week).

Abbreviations: AA, Black or African American; PPWL, postpartum weight loss; PPWR, postpartum weight retention.

Figure 1.

Changes in body weight and composition during and after pregnancy in women with obesity and postpartum weight retention (PPWR) or weight loss (PPWL). Data are presented per individual (Panel 1A, n = 37), as weekly mean (Panel 1B, n = 30), and as mean ± SEM (Panel 1C and 1D, n = 37). Panels 1E and 1F show individual data points for the association between changes in body weight and change in mass of body component (in kg: fat mass [FM]; fat-free mass [FFM]). Regression lines are shown for significant associations (Pregnancy; FM: R2 = 0.51, P < 0.001; FFM: R2 = 0.16, P = 0.02; Postpartum; FM: R2 = 0.88, P < 0.001). *Reflects a statistical significance (P < 0.05) of the time × group interaction, indicating that the change in weight between 2 consequent measures was different between the PPWL and PPWR groups.

Postpartum weight loss (PPWL) and weight retention

On average, body weight changes were linear during pregnancy and during the first 12 months postpartum, respectively (Fig. 1B). PPWL, defined as negative weight change from early pregnancy until 12 months postpartum, was observed in 16/37 women (43%) whereas postpartum weight retention (PPWR) was observed in 21/37 women (57%). From early pregnancy until 12 months after pregnancy, the changes in body weight were -4.9 ± 1.6 kg in the PPWL group compared with +8.6 ± 1.4 kg in the PPWG group. Between the groups, no difference in participant demographic characteristics, gestational weight gain, or breastfeeding duration was observed (Table 1), except for age; women with PPWL were significantly older (P = 0.007).

Body composition

During pregnancy, changes in FM were not significantly different between women with PPWL and PPWR (0.1 ± 1.1 vs 0.4 ± 0.9 kg; P = 0.83). Postpartum, women with PPWL lost −3.7 ± 1.9 kg of FM, whereas women with PPWR accumulated 6.2 ± 1.7 kg FM (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1C). Women with PPWL lost −1.3 ± 0.6 kg FFM at 12 months postpartum as compared with early pregnancy, and women with PPWR gained 2.0 ± 0.5 kg during the same period (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1D). During pregnancy, changes in body weight were significantly associated with changes in FM (R2 = 0.51; P < 0.001) and weakly with changes in FFM (R2 = 0.16; P = 0.02) (Fig. 1E). Postpartum, changes in body mass were only determined by changes in FM (R2 = 0.88; P < 0.001) (Fig. 1F).

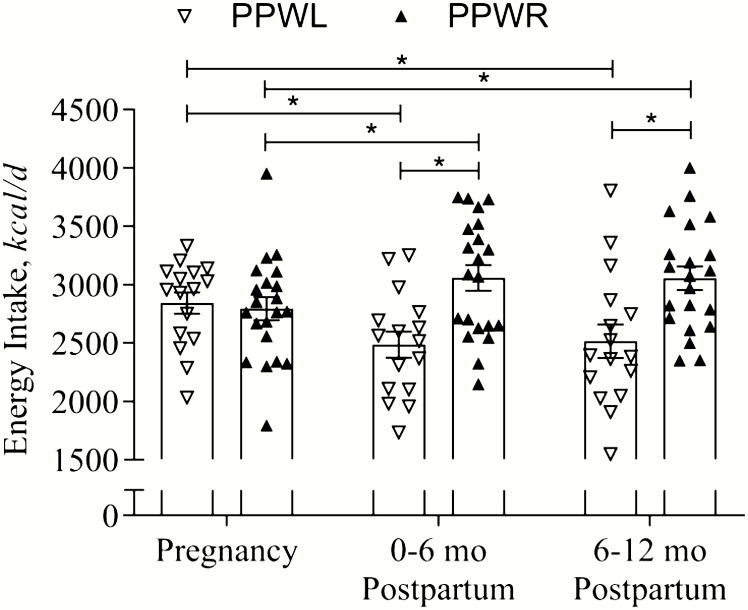

Energy intake

During pregnancy, energy intake was similar in women with PPWL and women with PPWR (2846 ± 110 kcal/d vs 2793 ± 95 kcal/d; 11.9 ± 0.46 MJ/d vs 11.7 ± 0.40 MJ/d; P = 0.72) (Fig. 2). As compared with pregnancy, women with PPWL decreased their energy intake by −356 ± 115 kcal/d (1490 ± 481 kJ/d; P = 0.004) and −327 ± 142 kcal/d (−1368 ± 594 kJ/d; P = 0.03) during 0 to 6 months and 6 to 12 months postpartum, respectively. In contrast, women with PPWR increased their energy intake by 262 ± 101 kcal/d (1096 ± 423 kJ/d; P = 0.01) and 259 ± 124 kcal/d (1084 ± 519 kJ/d; P = 0.04) during the same periods.

Figure 2.

Energy intake during and after pregnancy in women with obesity and postpartum weight retention (PPWR) or postpartum weight loss (PPWL). Data are reported as individual data (triangles) and mean ± SEM (bars). Pregnancy refers to the period from early to late pregnancy. *Indicates statistical significance (P < 0.05) between the PPWL and PPWR groups.

Relative to their energy requirements (TDEE), women with PPWL consumed −150 ± 101 kcal/d (−628 ± 423 kJ/d, −4%) less during the first 6 months after birth and −121 ± 107 kcal/d (−506 ± 448 kJ/d, −3%) less during 6 to 12 months postpartum. In contrast, women with PPWR consumed 78 ± 88 kcal/d (326 ± 368 kJ/d, +5%; P = 0.007) and 75 ± 93 kcal/d (314 ± 389 kJ/d, +5%; P = 0.01) more from 0 to 6 months and 6 to 12 months, respectively.

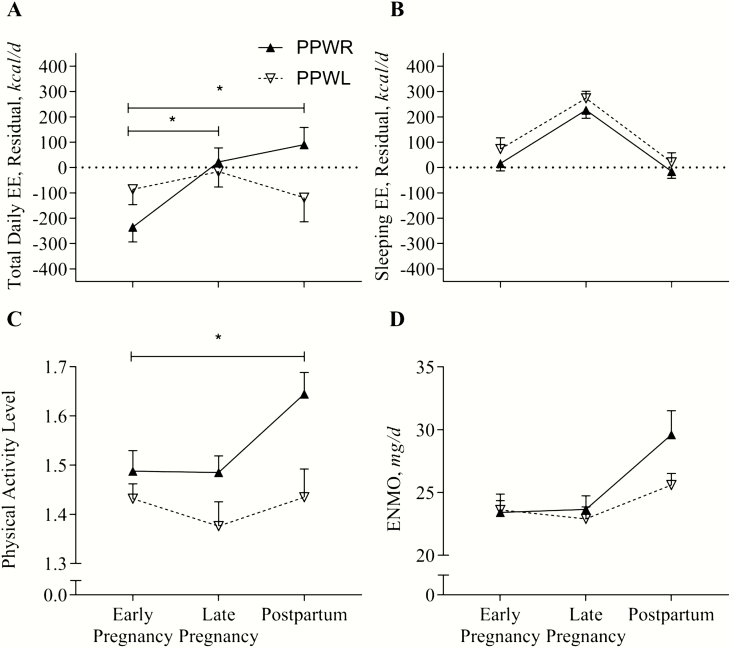

Energy expenditure and physical activity

TDEE, adjusted for differences in body composition, did not change from early to late pregnancy or to 12 months postpartum in women with PPWL (+70 ± 68 kcal/d, 293 ± 285 kJ/d; P = 0.31, and –33 ± 74 kcal/d, −138 ± 310 kJ/d; P = 0.66) (Fig. 3A). In women with PPWR, TDEE increased from early to late pregnancy (+257 ± 59 kcal/d, 1075 ± 247 kJ/d; P < 0.001) and remained increased at 12 months postpartum as compared with early pregnancy (+325 ± 65 kcal/d, 1360 ± 272 kJ/d; P < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Energy expenditure and physical activity during and after pregnancy in women with obesity and postpartum weight retention (PPWR) or weight loss (PPWL). Data are reported as mean ± SEM. Panel A: Total daily EE was measured over 7 days using doubly labeled water; differences between groups after adjustment for body mass (fat-free mass and fat mass). TDEEadj[kcal/d] = 918 + 33.45 × FFM[kg] − 1.75 × FM[kg]; R2 = 0.29; P = 0.003. Panel B, SleepEEadj[kcal/d] = 296 + 22.34 × FFM[kg] +5.07 FM[kg]; R2 = 0.67; P < 0.001). Abbreviations: EE, energy expenditure; ENMO, Euclidian norm minus 1; FFM, fat-free mass; FM, fat mass; TDEE, total daily energy expenditure.

For all women, sleeping EE increased significantly during pregnancy (+206 ± 23 kcal/d, 862 ± 96 kJ/d; P < 0.001), but decreased by the same magnitude postpartum (−248 ± 28 kcal/d, −1038 ± 117 kJ/d; P < 0.001). Sleeping EE was not different between women with PPWL compared with PPWR (group-difference: +46 ± 37 kcal/d, 192 ± 155 kJ/d; P = 0.22) (Fig. 3B).

Physical activity level (PAL) was not significantly different early in pregnancy (PPWL: 1.44 ± 0.04; PPWR: 1.48 ± 0.04; P = 0.55) and did not change during pregnancy (Fig. 3C). While women with PPWL maintained low PAL at 12 months postpartum, those with PPWR significantly increased PAL (P = 0.02). Using accelerometry, we observed the same pattern, but the change was not statistically significant (P = 0.10) (Fig. 3D).

Diet quality and metabolic biomarkers

Overall, the Healthy-Eating-Index was poor (48.7 ± 1.9). We did not observe any significant differences in diet quality between the groups (P = 0.94) or over time (P = 0.44; group × time P = 0.71). Similarly, no effects of group and time were observed for macronutrient composition (46.8 ± 1.3% carbohydrates, 37.8 ± 0.7% fat, and 16.4 ± 1.0% protein), and eating behavior, including cognitive restraint, hunger, disinhibition, mindful eating, or food cravings (Table 2).

Table 2.

Changes in Plasma Metabolic Biomarkers From Early Pregnancy Until 12 Months Postpartum

| PPWL n = 16 | PPWR n = 21 | P (time) | P (time × group) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose, mg/dL | Early Pregnancy | 89 ± 2 | 87 ± 1 | <0.001 | 0.15 |

| Late Pregnancy | 86 ± 2 | 84 ± 2 | |||

| Postpartum | 89 ± 1 | 92 ± 2 | |||

| Insulin, uIU/mL | Early Pregnancy | 15.7 ± 2.0 | 12.4 ± 1.8 | <0.001 | 0.09 |

| Late Pregnancy | 18.6 ± 2.0 | 17.0 ± 1.6 | |||

| Postpartum | 13.1 ± 1.9 | 14.2 ± 1.6 | |||

| HOMA-IR | Early Pregnancy | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | <0.001 | 0.13 |

| Late Pregnancy | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | |||

| Postpartum | 2.9 ± 0.5 | 3.1 ± 0.5 | |||

| HOMA-b | Early Pregnancy | 214 ± 22 | 189 ± 27 | <0.001 | 0.55 |

| Late Pregnancy | 322 ± 37 | 311 ± 31 | |||

| Postpartum | 176 ± 24 | 179 ± 17 | |||

| Matsuda-Index | Postpartum | 4.37 ± 0.61 | 3.38 ± 0.36 | 0.16 | |

| Stumvoll-Index | Postpartum | 1903 ± 160 | 2024 ± 147 | 0.59 | |

| Leptin, ng/mL | Early Pregnancy | 110 ± 8 | 131 ± 10 | <0.001 | 0.21 |

| Late Pregnancy | 113 ± 9 | 144 ± 11 | |||

| Postpartum | 76 ± 8 | 127 ± 13 | |||

| Leptin, ng/(mL*kg fat mass) | Early Pregnancy | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | <0.001 | 0.71 |

| Late Pregnancy | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | |||

| Postpartum | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | |||

| Cholecystokinine, pmol/L | Early Pregnancy | 224 ± 24 | 194 ± 18 | <0.001 | 0.03 |

| Late Pregnancy | 315 ± 24 | 326 ± 25 | |||

| Postpartum | 260 ± 15 | 281 ± 21 | |||

| Ghrelin, pg/mL | Early Pregnancy | 475 ± 49 | 443 ± 29 | <0.001 | 0.26 |

| Late Pregnancy | 384 ± 29 | 389 ± 22 | |||

| Postpartum | 455 ± 40 | 486 ± 30 | |||

| Peptide YY, pg/mL | Early Pregnancy | 81 ± 6 | 83 ± 6 | 0.24 | 0.27 |

| Late Pregnancy | 75 ± 4 | 88 ± 7 | |||

| Postpartum | 82 ± 7 | 86 ± 9 |

Data are reported as mean ± SEM. Measurements were taken at 13–16 weeks gestation (Early Pregnancy), at 35–37 weeks gestation (Late Pregnancy), and at 48–56 weeks postpartum (Postpartum).

P values refer to the interaction-term group × time for biomarkers with repeated measures, and to the unpaired comparison for Matsuda and Stumvoll-Indices. Group-differences were considered statistically significant, if P < 0.05. For statistically significant interactions, shared letters indicate no significant within-group differences, and * indicate a significant difference early in pregnancy, and for the changes from early to late pregnancy, and from early or late to postpartum.

HOMA-IR was calculated as fasting plasma glucose (mg/dL) × fasting plasma insulin (μIU/mL) / 405; HOMA-b was calculated as 20 × plasma insulin (μIU/mL) / (plasma glucose (mmol/L) − 3.5);

Matsuda index (glucose in mg/dL, insulin in μIU/mL) = [10 000/square root ([T0Glucose × T0Insulin] × ([T0Glucose + T60Glucose + T60Glucose + T120Glucose]/4) × ([T0Insulin + T60Insulin + T60Insulin + T120Insulin]/4)];

Stumvoll-Index (glucose in mmol/l, insulin in pmol/l) = [1194 + 4.724 × T0Insulin − 117 × T60Glucose + 1.414 × T60Insulin].

Abbreviations: PPWL, postpartum weight loss; PPWR, postpartum weight retention.

Biomarkers of glucose homeostasis were not different between women with PPWL compared with those with PPWR (Table 3). For appetite-regulating hormones, leptin concentrations were lower in women with PPWL as compared with PPWR (P = 0.02), specifically at 12 months postpartum (P = 0.005). Change in leptin concentration during the observation period was proportional to changes in FM (R2 = 0.60; P < 0.001). The change in plasma cholecystokinine postpartum was lower for women with PPWL compared with women with PPWR (P = 0.05). No differences were observed for changes in concentrations of Peptide-YY and ghrelin.

Table 3.

Changes in Eating Behaviors From Early Pregnancy Until 12 Months Postpartum

| PPWL n = 16 | PPWR n = 21 | P (Time) | P (Time* group) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eating Inventory | |||||

| Restraint | Early Pregnancy | 7.9 ± 1.0 | 9.1 ± 1.2 | 0.68 | 0.85 |

| Late Pregnancy | 8.1 ± 1.1 | 9.2 ± 1.1 | |||

| Postpartum | 8.8 ± 1.0 | 9.3 ± 0.8 | |||

| Disinhibition | Early Pregnancy | 5.8 ± 0.8 | 5.6 ± 0.7 | 0.006 | 0.48 |

| Late Pregnancy | 5.8 ± 0.9 | 5.3 ± 0.8 | |||

| Postpartum | 6.8 ± 1.1 | 7.3 ± 0.9 | |||

| Hunger | Early Pregnancy | 4.2 ± 0.5 | 4.0 ± 0.4 | 0.18 | 0.57 |

| Late Pregnancy | 4.9 ± 0.6 | 4.3 ± 0.6 | |||

| Postpartum | 4.7 ± 0.8 | 5.2 ± 0.7 | |||

| Mindful Eating | |||||

| Awareness | Early Pregnancy | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 0.81 | 0.32 |

| Late Pregnancy | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | |||

| Postpartum | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | |||

| Distraction | Early Pregnancy | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 0.03 | 0.34 |

| Late Pregnancy | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | |||

| Postpartum | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | |||

| Disinhibition | Early Pregnancy | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 0.09 | 0.70 |

| Late Pregnancy | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 3.2 ± 0.1 | |||

| Postpartum | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | |||

| Emotional | Early Pregnancy | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 3.3 ± 0.1 | <0.001 | 0.07 |

| Late Pregnancy | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | |||

| Postpartum | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | |||

| External Cues | Early Pregnancy | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 0.38 | 0.96 |

| Late Pregnancy | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | |||

| Postpartum | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | |||

| Summary | Early Pregnancy | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | <0.001 | 0.95 |

| Late Pregnancy | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | |||

| Postpartum | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | |||

| Cravings | |||||

| Fat | Early Pregnancy | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.63 |

| Late Pregnancy | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | |||

| Postpartum | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | |||

| Sweets | Early Pregnancy | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | <0.001 | 0.98 |

| Late Pregnancy | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | |||

| Postpartum | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | |||

| Carbohydrates | Early Pregnancy | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 0.67 | 0.53 |

| Late Pregnancy | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | |||

| Postpartum | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | |||

| Fast Food Fats | Early Pregnancy | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 0.10 | 0.67 |

| Late Pregnancy | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | |||

| Postpartum | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | |||

| Fruits & Vegetables | Early Pregnancy | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 0.54 | 0.65 |

| Late Pregnancy | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | |||

| Postpartum | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | |||

| Summary | Early Pregnancy | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.99 |

| Late Pregnancy | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | |||

| Postpartum | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.1 |

Data are reported as mean ± SEM. Measurements were taken at 13–16 weeks gestation (Early Pregnancy), at 35–37 weeks gestation (Late Pregnancy), and at 48–56 weeks postpartum (Postpartum).

P values refer to the main effect of time and the interaction-term group × time for eating behaviors with repeated measures.

Abbreviations: PPWL, postpartum weight loss; PPWR, postpartum weight retention.

Discussion

In the present study of women with obesity, we observed that weight gain from early pregnancy to 12 months postpartum was the result of weight change after pregnancy as opposed to weight gain during pregnancy. Weight change postpartum was characterized by marked changes in FM and was due to an increase in energy intake after pregnancy. This increase was disproportionate to EE, which returned to the rate observed in early pregnancy. Physical activity, diet quality, insulin sensitivity, and appetite-regulating hormones did not contribute to PPWR. In contrast to other studies (23, 24), breastfeeding duration was not associated with changes in body weight or FM.

The average weight gain was 1.8 kg during the observation period (1.2 kg per year), and comparable to the long-term changes in body weight of nonpregnant women with obesity (25). The change in weight however ranged almost 50 kg, indicating high vulnerability for some women with obesity to experience sizable changes in body weight related to pregnancy. Using robust body composition assessments, we showed that the variability in postpartum weight changes is largely due to fat accumulation (R2 = 0.88), which explains the increased risks for metabolic diseases associated with weight retention in postpartum women (4, 6, 7).

PPWR was observed in 57% of women and severe weight retention (greater than 4.5 kg, 10 lbs) in more than 40% of women, which is in line with epidemiological studies (1, 3). Interestingly, between women who lost weight and women who gained weight postpartum, only nominal differences in gestational weight gain were observed. It is therefore not surprising that, in women with obesity, attenuation of gestational weight gain has little or no effect on weight retention postpartum (26, 27). For the majority of women with obesity, PPWR is new FM gained postpartum rather than weight retained from pregnancy. The divergence in weight change after birth highlights the increased necessity for clinicians to discuss with their patients the continued risk for weight gain following pregnancy. This is true even for women with gestational weight gain less than the current recommendations (5 kg).

The primary factor that explained weight trajectories postpartum was the change in energy intake from pregnancy to postpartum. Women who returned to their pre-pregnancy weight or lost weight (−3.5 kg FM) by 12 months postpartum, reduced energy intake by ~350 kcals (1500 kJ/d) per day which was approximately 12% lower compared with the energy intake during pregnancy and 3% lower than the postpartum EE. On the other hand, women who gained weight postpartum increased their energy intake by ~250 kcal (~1000 kJ/d) per day or 9% more compared with the energy intake during pregnancy.

Physical activity is characteristically low in women with obesity (18) and declines during pregnancy (13). In women who lost weight postpartum, physical activity level was steady throughout pregnancy and postpartum and therefore did not likely contribute to weight loss postpartum. However, in women who gained weight, physical activity surprisingly increased postpartum. Physical activity, although resulting in an increased exercise-induced EE, often does not induce a negative energy balance and promote weight loss (28, 29). Exercising individuals tend to either conserve energy in nonexercise activities or overcompensate with increased energy intake (30, 31). Thus, it is not surprising that physical activity did not contribute with postpartum weight change.

In the present study, we observed no differences in metabolic biomarkers between women with PPWR and PPWL, including glucose homeostasis and resting energy metabolism. This finding is surprising given the marked changes in adiposity. For glucose homeostasis, the increased physical activity in women with PPWR may have attenuated adverse effects. For metabolic adaptations, that is, changes in metabolic rate, our data suggests no effects based on changes in body weight. In contrast, study of nonpregnant subjects demonstrated metabolic adaptations of +50 kcal/d to −100 kcal/ (+200 kJ/d to −400 kJ/d) during weight gain and weight loss, respectively (32). Such metabolic adaptions are dynamic, specifically during early phases of over- or under- eating. The absence of metabolic adaptation at 12 months postpartum does not capture the dynamics of metabolic adaptations over the entire year since giving birth and therefore does not exclude the possibility of its association with body weight changes if we had measured it at other earlier time points. Measurements of body composition and energy metabolism early after delivery would allow for a prospective analysis of the involvement of metabolic adaptations in PPWR.

Using the objective measures of body composition and energy balance (intake, expenditure, physical activity) our findings can help to inform clinical recommendations and interventions for weight management. We demonstrate that an energy deficit of 3% over 12 months induces a loss of FM of ~3.5 kg (0.3 kg per month). In previous intervention studies for PPWL, the type of intervention, that is, either dietary restriction (33–38), use of meal replacements (10), or increased physical activity (39, 40), had only small effects on postpartum weight change (< 3 kg) (26, 41), and thus induced energy deficits smaller than 3%.

Tailoring intervention programs to individual patient energy needs using anthropometry-based equations (42, 43) may promote larger benefits for postpartum weight management. Further toward the design, the most effective method of delivery has yet to be determined, but technology-based interventions may offer more frequent contact (44, 45), while the personal interaction offered by face-to-face interventions may foster better adherence. Patient-centered formative research should guide future intervention development since the initiation of such intervention programs will need to begin when normal life drastically shifts to recover from pregnancy and to care for a newborn.

This study excels for its prospective, observational design and application of rigorous assessments of energy balance and its determinants. However, some limitations should be considered. First, we acknowledge that a more optimal study design would include a pregravid weight and body composition assessment; however, there are numerous challenges in completing those types of studies and in a timely manner. The first measure of body weight occurred at ~15 weeks of gestation and therefore PPWR may indeed be underestimated by weight gain that occurred earlier in pregnancy. Second, the cost of using comprehensive, gold-standard methodologies for energy balance phenotyping limits the sample size. However, we conducted post hoc power calculations, which indicated that the observed statistical power (β) of the difference in postpartum energy intake, and the change in energy intake from pregnancy to postpartum in the available sample size (n = 37) was 89%. Third, our study did not include a group of women with obesity who were not pregnant which would allow the effect of pregnancy on long term body weight changes to be better interpreted. To minimize subject burden, body composition or energy expenditure was not measured immediately after delivery. As a result, the body composition changes attributed to the fetal-placental unit was assumed to be 8 kg FFM for all subjects. For the calculation of energy intake, we assumed that TDEE measured 12 months postpartum reflects the entire postpartum period. This assumption is supported by the absence of changes in maternal FFM, the most important determinant of TDEE, after pregnancy and the small effect of FM on TDEE (−1.75 kcal/kg FM). Lastly, breastfeeding duration was assessed by self-report and did not include information on intensity (ie, frequency, exclusivity).

Weight changes (mostly FM) from birth to 12 months postpartum in women with obesity were highly variable and independent of gestational weight gain. Weight change postpartum was due to an increase in energy intake rather than a maladaptation to the physiology of pregnancy. Therefore, for women with obesity to return to pre-pregnancy weight, the focus should be eating to satisfy energy needs and restoring physical activity to pre-pregnancy levels. There is a clear need to address postpartum weight management in women with obesity early after birth to ensure they do not experience unnecessary weight gain and associated comorbidities.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge administrative support from Porsha Vallo, Dr. Elizabeth Sutton, Kelsey Olson, Alexandra Beyer, Alexis O’Connell, and Natalie Comardelle; technical assistance of Dr. Jennifer Rood, Loren Cain, and Brian Gilmore; and the recruitment and retention support from Drs. Ralph Dauterive, Evelyn Griffin, and Evelyn Hayes. Above all, we thank the participants for allowing us to follow their pregnancies.

Financial Support: This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01DK099175; Redman) and in part by support of clinical cores (P30DK072476 and U54GM104940).

Clinical Trial Information: Trial registered at Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01954342.

Author Contributions: J.M., E.R., and L.M.R. designed research; J.M., A.D.A., and M.S.A. conducted research; J.M., R.A.B., E.R., and L.M.R. analyzed data or performed statistical analysis; J.M., E.R., and L.M.R. wrote paper; L.M.R. had primary responsibility for final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- EE

energy expenditure

- ENMO

Euclidean norm minus 1

- FFM

fat-free mass

- FM

fat mass

- HOMA-IR

homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance

- PAL

physical activity level

- PPWL

postpartum weight loss

- PPWR

postpartum weight retention

- RMR

resting metabolic rate

- SD

standard deviation

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- TDEE

total daily energy expenditure

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: J.M., A.D.A., M.S.A., R.A.B., E.R., and L.M.R. have nothing to declare.

Data Availability: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Endres LK, Straub H, McKinney C, et al. ; Community Child Health Network of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Postpartum weight retention risk factors and relationship to obesity at 1 year. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):144–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kirkegaard H, Stovring H, Rasmussen KM, Abrams B, Sørensen TI, Nohr EA. How do pregnancy-related weight changes and breastfeeding relate to maternal weight and BMI-adjusted waist circumference 7 y after delivery? Results from a path analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(2):312–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nohr EA, Vaeth M, Baker JL, Sørensen TIa, Olsen J, Rasmussen KM. Combined associations of prepregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain with the outcome of pregnancy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(6):1750–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gunderson EP, Sternfeld B, Wellons MF, et al. Childbearing may increase visceral adipose tissue independent of overall increase in body fat. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16(5):1078–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McClure CK, Catov JM, Ness R, Bodnar LM. Associations between gestational weight gain and BMI, abdominal adiposity, and traditional measures of cardiometabolic risk in mothers 8 y postpartum. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(5):1218–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van Rossem L, Wijga AH, Gehring U, Koppelman GH, Smit HA. Maternal gestational and postdelivery weight gain and child weight. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):e1294–e1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leonard SA, Rasmussen KM, King JC, Abrams B. Trajectories of maternal weight from before pregnancy through postpartum and associations with childhood obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106(5):1295–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mamun AA, Kinarivala M, O’Callaghan MJ, Williams GM, Najman JM, Callaway LK. Associations of excess weight gain during pregnancy with long-term maternal overweight and obesity: evidence from 21 y postpartum follow-up. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(5):1336–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gore SA, Brown DM, West DS. The role of postpartum weight retention in obesity among women: a review of the evidence. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(2):149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Phelan S, Wing RR, Brannen A, et al. Does partial meal replacement during pregnancy reduce 12-month postpartum weight retention? Obesity (Silver Spring). 2019;27(2):226–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ruchat SM, Mottola MF, Skow RJ, et al. Effectiveness of exercise interventions in the prevention of excessive gestational weight gain and postpartum weight retention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(21):1347–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Institute of Medicine (US) and National Research Council (US) Committee to Reexamine IOM Pregnancy Weight Guidelines. Determining optimal weight gain. In: Rasmussen KM, Yaktine AL, eds. Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Most J, St Amant M, Hsia D, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for energy intake in pregnant women with obesity. J Clin Invest. 2019;130:4682-4690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pellonperä O, Koivuniemi E, Vahlberg T, et al. Body composition measurement by air displacement plethysmography in pregnancy: Comparison of predicted versus measured thoracic gas volume. Nutrition. 2019;60:227–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Most J, Marlatt KL, Altazan AD, Redman LM. Advances in assessing body composition during pregnancy. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018;72(5):645–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thomas DM, Navarro-Barrientos JE, Rivera DE, et al. Dynamic energy-balance model predicting gestational weight gain. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(1):115–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gilmore LA, Butte NF, Ravussin E, Han H, Burton JH, Redman LM. Energy intake and energy expenditure for determining excess weight gain in pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(5):884–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Most J, Vallo PM, Gilmore LA, et al. Energy expenditure in pregnant women with obesity does not support energy intake recommendations. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2018;26(6):992–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Most J, Redman LM. Does energy expenditure influence body fat accumulation in pregnancy? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(1):119–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Most J, Vallo PM, Altazan AD, et al. Food photography is not an accurate measure of energy intake in obese, pregnant women. J Nutr. 2018;148(4):658–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. The Epidemiology and Genomics Research Program. Overview & Background of The Healthy Eating Index.National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences. Healthy Eating Index Web site; Published 2018. https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/hei/. Accessed May 28, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Most J, Rebello CJ, Altazan AD, Martin CK, Amant MS, Redman LM. Behavioral determinants of objectively assessed diet quality in obese pregnancy. Nutrients. 2019;11(7):E1446. doi:10.3390/nu11071446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gunderson EP, Quesenberry CP Jr, Ning X, et al. Lactation duration and midlife atherosclerosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(2):381–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. López-Olmedo N, Hernández-Cordero S, Neufeld LM, García-Guerra A, Mejía-Rodríguez F, Méndez Gómez-Humarán I. The associations of maternal weight change with breastfeeding, diet and physical activity during the postpartum period. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(2):270–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brown WJ, Williams L, Ford JH, Ball K, Dobson AJ. Identifying the energy gap: magnitude and determinants of 5-year weight gain in midage women. Obes Res. 2005;13(8):1431–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dalrymple KV, Flynn AC, Relph SA, O’Keeffe M, Poston L. Lifestyle interventions in overweight and obese pregnant or postpartum women for postpartum weight management: a systematic review of the literature. Nutrients. 2018;10(11):E1704. doi:10.3390/nu10111704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Michel S, Raab R, Drabsch T, Günther J, Stecher L, Hauner H. Do lifestyle interventions during pregnancy have the potential to reduce long-term postpartum weight retention? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2019;20(4):527–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Donnelly JE, Blair SN, Jakicic JM, Manore MM, Rankin JW, Smith BK; American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(2):459–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Swift DL, Johannsen NM, Lavie CJ, Earnest CP, Church TS. The role of exercise and physical activity in weight loss and maintenance. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;56(4):441–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Martin CK, Johnson WD, Myers CA, et al. Effect of different doses of supervised exercise on food intake, metabolism, and non-exercise physical activity: The E-MECHANIC randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;110(3):583–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Thomas DM, Bouchard C, Church T, et al. Why do individuals not lose more weight from an exercise intervention at a defined dose? An energy balance analysis. Obes Rev. 2012;13(10):835–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Müller MJ, Enderle J, Bosy-Westphal A. Changes in energy expenditure with weight gain and weight loss in humans. Curr Obes Rep. 2016;5(4):413–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Herring SJ, Cruice JF, Bennett GG, Davey A, Foster GD. Using technology to promote postpartum weight loss in urban, low-income mothers: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2014;46(6):610–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huseinovic E, Bertz F, Leu Agelii M, Hellebö Johansson E, Winkvist A, Brekke HK. Effectiveness of a weight loss intervention in postpartum women: results from a randomized controlled trial in primary health care. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104(2):362–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bertz F, Brekke HK, Ellegård L, Rasmussen KM, Wennergren M, Winkvist A. Diet and exercise weight-loss trial in lactating overweight and obese women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(4):698–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Colleran HL, Lovelady CA. Use of MyPyramid menu planner for moms in a weight-loss intervention during lactation. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(4):553–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Craigie AM, Macleod M, Barton KL, Treweek S, Anderson AS; WeighWell team Supporting postpartum weight loss in women living in deprived communities: design implications for a randomised control trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65(8):952–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lovelady CA, Garner KE, Moreno KL, Williams JP. The effect of weight loss in overweight, lactating women on the growth of their infants. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(7):449–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ferrara A, Hedderson MM, Brown SD, et al. The comparative effectiveness of diabetes prevention strategies to reduce postpartum weight retention in women with gestational diabetes mellitus: The Gestational Diabetes’ Effects on Moms (GEM) cluster randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(1):65–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Harrison CL, Brown WJ, Hayman M, Moran LJ, Redman LM. The role of physical activity in preconception, pregnancy and postpartum health. Semin Reprod Med. 2016;34(2):e28–e37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dodd JM, Deussen AR, O’Brien CM, et al. Targeting the postpartum period to promote weight loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev. 2018;76(8):639–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pereira LCR, Purcell SA, Elliott SA, et al. ; ENRICH Study Team The use of whole body calorimetry to compare measured versus predicted energy expenditure in postpartum women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;109(3):554–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Most J, Redman LM. Energy expenditure predictions in postpartum women require adjustment for race. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;110(2):522–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sherifali D, Nerenberg KA, Wilson S, et al. The effectiveness of ehealth technologies on weight management in pregnant and postpartum women: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(10):e337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mertens L, Braeken MAKA, Bogaerts A. Effect of lifestyle coaching including telemonitoring and telecoaching on gestational weight gain and postnatal weight loss: a systematic review. Telemed J E Health. 2019;25(10):889–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]