Abstract

Mucosal melanoma is a rare and aggressive subtype of melanoma that has a less favorable prognosis due to the lack of understanding and identification of oncogenic drivers. Recently, whole genome and whole exome sequencing have unveiled the molecular landscape and potential oncogenic drivers of mucosal melanoma, which remains distinct from cutaneous melanoma. In this review, we provide an overview of the genomic landscape of mucosal melanoma, with a focus on molecular studies identifying potential oncogenic drivers allowing for a better mechanistic understanding of the biology of mucosal melanoma. We summarized the published genomics and clinical data supporting the observations that mucosal melanoma harbors distinct genetic alterations and oncogenic drivers from cutaneous melanoma, and thus should be treated accordingly. The common drivers (BRAF and NRAS) found in cutaneous melanoma have lower mutation rate in mucosal melanoma. In contrast, SF3B1 and KIT have higher mutation rate in mucosal melanoma as compared to cutaneous melanoma. From the meta-analysis, we also observed that the mutational profiles are slightly different between the “upper” and “lower” regions of mucosal melanoma, providing new insights and therapeutic options for the mucosal melanoma patients. Mutations identified in mucosal melanoma should be incorporated into routine clinical testing, as there are targeted therapies already developed for treating patients with these mutations in the precision medicine era.

Keywords: Mucosal Melanoma, KIT, SF3B1, Mutational Landscape, Druggable Targets

1. Introduction

Mucosal melanoma is an aggressive rare sub-type of melanoma, arising from melanocytes in mucosal tissues lining the respiratory, gastrointestinal and urogenital tracts1. Mucosal melanoma is markedly different from cutaneous melanoma at both the molecular and clinical level. Unlike cutaneous melanoma, mucosal melanoma has a significantly lower somatic mutational burden, lower frequency of the common targetable BRAF-V600E mutation and poorer responses to immunotherapy. Clinical presentation of mucosal melanoma is aggressive, the 5-year survival of mucosal melanoma, considering all stages at time of diagnosis, is 14% as compared to 80% for cutaneous melanoma2,3. While major advancements have been made in the understanding and treatment of UV-exposed cutaneous melanoma, there remains a lack of understanding and identification of oncogenic drivers in mucosal melanoma, likely due to the rarity of samples and lack of available preclinical models. Recently, whole genome and whole exome sequencing have unveiled the molecular landscape and potential oncogenic drivers of mucosal melanoma, which remains distinct from cutaneous melanoma. Such studies have identified that somatic mutation rates are considerably lower in mucosal melanoma, and do not display the UV mutational signatures, as compared to UV-exposed cutaneous melanoma4. Interestingly, the somatic mutation rates in mucosal melanoma are comparable to the rates seen in cancers that are not associated with exposure to known mutagens4. It has also been demonstrated that mucosal melanoma display increased genomic instability which is characterized by structural variants, amplifications and deletions4–7. In this review, we provide an overview of the genomic landscape of mucosal melanoma, with a focus on molecular studies identifying potential oncogenic drivers allowing for a better mechanistic understanding of the biology of mucosal melanoma. We systematically reviewed published literatures and identified 65 key studies that define the mutational landscape of mucosal melanoma (Table 1). We classify the somatic mutations as “druggable” based on the published clinical trial results and discuss the recent advances in systemic treatment of this disease. We summarized the published genomics and clinical data supporting the observations that mucosal melanoma harbors distinct genetic alterations and oncogenic drivers from cutaneous melanoma, and thus should be treated accordingly.

Table 1:

Mucosal melanoma mutational studies covered in this review.

| Mucosal Melanoma Site | Number of Patients | Number of Mutations | Region | Detection Method | Reference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRAF | NRAS | NF1 | KIT | SF3B1 | Upper | Lower | ||||

| Whole Genome Sequencing/Whole Exome Sequencing Studies | ||||||||||

| Oral | 65 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 15 | --- | X | WGS | 5 | |

| Oral | 19 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | X | WES | 20 | |

| Various | 19 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 9 | 8 | X | X | WES | 21 |

| Various | 8 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | X | X | WGS | 6 |

| Various | 67 | 3 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 8 | X | X | WGS | 7 |

| Various | 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | WGS and WES | 4 | ||

| Various | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | WES/WGS | 22 | ||

| Various | 8 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | WES | 23 | ||

| Various | 46 | 0 | 8 | --- | 3 | 9 | WES | 24 | ||

| Targeted Sequencing Studies | ||||||||||

| Anorectal | 15 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 3 | X | Targeted NGS | 74 | |

| Vulvovaginal | 51 | 6 (5 NA) | 1 (26 NA) | --- | 10 (5 NA) | --- | X | Sanger / NGS | 75 | |

| Vulvovaginal | 20 | --- | --- | --- | 3 (7 NA) | --- | X | Targeted NGS | 76 | |

| Various | 27 | 3 | 6 | X | X | Targeted NGS | 47 | |||

| Various | 71 | 5 | 6 | 13 | 5 | 7 | X | X | Targeted NGS | 77 |

| Various | 43 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 5 | X | X | Targeted NGS | 32 |

| Various | 45 | 3 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 12 | X | X | Targeted NGS | 78 |

| Various | 41 | 0 | --- | 9 | 4 | --- | Targeted NGS | 79 | ||

| Various | 46 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 3 | --- | Targeted NGS | 49 | ||

| Various | 28 | 2 | 4 | --- | 2 | --- | Targeted NGS | 80 | ||

| Oral | 57 | 0 | 0 | --- | 4 | --- | X | Sanger | 81 | |

| Oral | 139 | --- | --- | --- | 22 | --- | X | Sanger | 60 | |

| Oral | 18 | --- | --- | --- | 4 (3 NA) | --- | X | Sanger | 82 | |

| Sinonasal | 72 | 4 | 8 | --- | 16 | 5 | X | Sanger | 83 | |

| Sinonasal | 32 | 0 | 5 | --- | 4 | --- | X | Sanger | 84 | |

| Sinonasal | 17 | 0 | 3 | --- | 1 | --- | X | Sanger | 85 | |

| Sinonasal | 56 | 2 | 8 | --- | 2 | --- | X | Sanger | 86 | |

| Head and neck | 42 | 2 | 2 | 4 | X | Sanger | 87 | |||

| Head and Neck | 28 | --- | --- | --- | 7 | --- | X | Sanger | 36 | |

| Esophageal | 16 | 1 | 6 | --- | 1 | --- | X | Sanger | 31 | |

| Anorectal | 20 | 0 (1NA) | 1 (1NA | --- | 3 | --- | X | Sanger | 88 | |

| Anorectal | 31 | --- | --- | --- | 11 | --- | X | Sanger | 89 | |

| Vulvar and Vaginal | 65 | 0 (11 NA) | (8 NA) | --- | 7 (11 NA) | --- | X | Sanger | 90 | |

| Vulvovaginal | 24 | 0 | 4 | --- | 1 | --- | X | Sanger | 91 | |

| Vulvovaginal | 24 | 0 | 4 | --- | 4 | --- | X | Sanger | 92 | |

| Vulvovaginal | 16 | 1 | 0 | --- | 0 | --- | X | Sanger | 93 | |

| Various | 86 | 0 (44 NA) | --- | --- | 5 (43 NA) | --- | Sanger | 35 | ||

| Various | 755 | 66 (35 NA) | 20 (200 NA) | --- | 66 | --- | Sanger | 37 | ||

| Various | 71 | 4 | 7 | --- | 7 | --- | Sanger | 30 | ||

| Various | 38 | 1 (2NA) | 2 (4 NA) | --- | 8 | --- | Sanger | 94 | ||

| Various | 55 | 1 | 1 | 3 | --- | Sanger | 95 | |||

| Various | 120 | 13 | 9 | --- | --- | --- | Sanger | 96 | ||

| Various | 167 | --- | --- | --- | 16 | --- | Sanger | 97 | ||

| Various | 39 | 3 (12 NA) | --- | --- | 6 (2 NA) | --- | Sanger | 98 | ||

| Various | 52 | --- | --- | --- | 9 | --- | Sanger | 99 | ||

| Various | 25 | --- | --- | --- | 7 | --- | Sanger | 100 | ||

| Various | 25 | 0 (8 NA) | 1 (8NA) | --- | 4 (8 NA) | --- | Sanger | 101 | ||

| Various | 35 | --- | --- | --- | 3 | --- | Sanger | 102 | ||

| Various | 36 | 1 | 5 | --- | --- | --- | Sanger | 103 | ||

| Various | 13 | 0 | --- | --- | --- | --- | Sanger | 104 | ||

| Various | 25 | 1 | --- | --- | --- | --- | Sanger | 105 | ||

| Various | 31 | --- | --- | --- | 4 | --- | Sanger | 106 | ||

| Various | 22 | 0 | 2 | --- | 4 | --- | Sanger | 107 | ||

| Various | 21 | --- | 1 | --- | --- | --- | Sanger | 108 | ||

| Oral | 14 | 3 | 4 | --- | --- | --- | X | Pyrosequencing | 109 | |

| Various | 62 | 2 (5 NA) | 7 | Pyrosequencing/Sanger | 110 | |||||

| Various | 23 | 0 | 1 | --- | 0 (7 NA) | --- | Pyrosequencing/Sanger | 111 | ||

| Various | 26 | 0 | --- | --- | --- | --- | Pyrosequencing | 112 | ||

| Various | 93 | 8 (1 NA) | 11 (1 NA) | --- | 17 | --- | PCR assay | 34 | ||

| Various | 30 | 1 | 1 | --- | 5 | --- | PCR assay | 113 | ||

| Various | 37 | --- | --- | --- | 16 | --- | PCR assay | 66 | ||

| Various | 5 | --- | --- | --- | 0 | --- | PCR assay | 114 | ||

| Various | 16 | --- | --- | --- | 6 | --- | HRM/sequencing | 115 | ||

| Various | 48 | --- | --- | --- | 8 | --- | HRM/sequencing | 116 | ||

| Various | 45 | 0 | 9 | --- | 7 | --- | DHPLC / Sequencing | 117 | ||

| Various | 706 | 70 | X | ND: from patient database | 2 | |||||

Note: NA = not available, --- = not reported, ND = not determined.

2. Melanocyte biology and clinical characteristics of mucosal melanoma

Melanoma comprises all skin cancers that arise from melanocytes, which are specialized cells whose primary role is the production of melanin that serves as a shield to protect DNA from UV-radiation. The presence of melanocytes has been demonstrated in mucosal membranes, however, the definitive role and function of mucosal melanocytes in non-UV exposed mucosal tissues remains unclear. It is hypothesized that melanocytes localized to mucosal tissues potentially due to errors in migration from the neural crest during development3. Interestingly, melanin is involved in antimicrobial defense, supporting a role for melanin in innate immunity8. It is hypothesized that mucosal melanocytes have an immunogenic role, especially given their location in immunologically critical mucosal surfaces3. In order to understand the biology of mucosal melanoma tumorigenesis, examining the different functions of melanocytes situated in various mucosal tissues may be of importance.

It is estimated that mucosal melanoma accounts for 0.8–1.8% of all melanomas in the US9, while the incidence in Chinese populations has been reported to reach 23%, likely due to the lower prevalence of cutaneous melanoma in Asian populations10. While mucosal melanomas can arise from any mucosal epithelium, the most common areas are vulvovaginal (18–40% of cases), anorectal (17–24% of cases) and the head and neck region (31–55% of cases)11,12. In rare occasions, primary mucosal melanoma has been observed in the urinary tract, esophagus, stomach, small and large intestine and cervix13. So far, the definitive risk factors for the development of mucosal melanoma remain unknown.

The five year overall survival rate for all subtypes of mucosal melanoma is only 25%, however mucosal melanoma of the head and neck region has a significantly better five year overall survival rate of 31.7%, as compared to anorectal (19.8) and vulvovaginal (11.4%)14. The median age of diagnosis for mucosal melanoma is 7011,15. Overall, the incidence of mucosal melanoma is stable, except for anorectal melanomas which have an increasing incidence, although one cannot rule out this increase as being attributed to awareness of clinicians and better diagnostic resources for mucosal melanoma16.

Mucosal melanomas often present and are diagnosed at later stages, likely due to the fact that they occur in more concealed areas of the body. Locoregional nodal metastasis at diagnosis is highly common in mucosal melanoma, specifically 21% of head and neck, 23% of vulvovaginal and 61% of anorectal mucosal melanomas present with involved lymph nodes14. Even considering the stage at diagnosis, mucosal melanoma is associated with significantly worse survival outcomes compared to cutaneous and acral melanoma17. Currently, the best approved treatment modality for mucosal melanoma is complete surgical excision of the primary tumor. However, the anatomical surgical constraints and multifocal growth pattern significantly limit the ability for wide negative margins, and must be heavily weighed on the patient’s quality of life. Unfortunately, 50–90% of patients exhibit postoperative local recurrence, even in the context of achieving negative margins14. Adjuvant radiotherapy improves local control of the disease but does not change the overall survival18,19. Therefore, there is an urgent need to better molecularly characterize mucosal melanoma and to identify “druggable” targets to improve clinical outcomes in this rare cancer.

3. Mutated driver genes and molecular landscape of Mucosal Melanoma

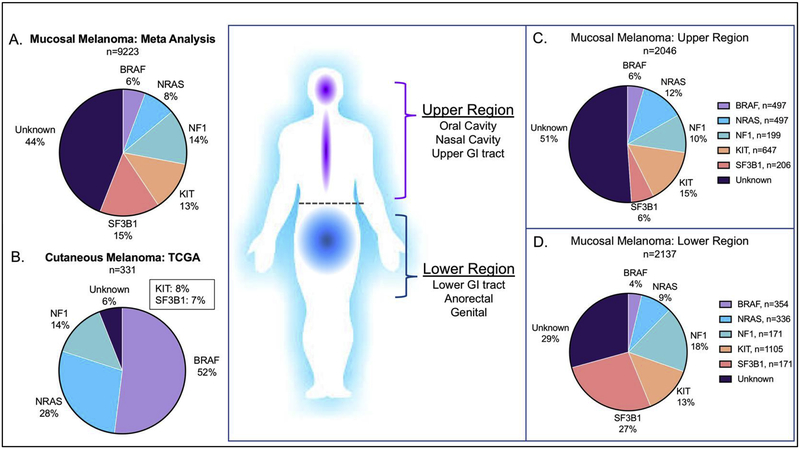

Recently, several studies have been conducted using targeted sequencing, whole-exome sequencing (WES) or whole-genome sequencing (WGS) approaches to characterize and identify somatic mutations in mucosal melanoma. However, due to the limited samples of this rare cancer, most of these global genome studies (WES/WGS) have small sample sizes (range from 2–67, average of 27)4–7,20–24. To systematically define the mutational landscape of mucosal melanoma, we performed a meta-analysis of 4009 patients reported in 65 published studies utilizing either targeted sequencing or WES/WGS technologies (Table 1). We found that mucosal melanoma has a different mutational landscape as compared to cutaneous melanoma (Figure 1A & 1B). The mutation burden is much lower in mucosal melanoma, as compared to cutaneous melanoma4,6,7,21. Moreover, we also observed that the mutational landscape is different between mucosal melanoma in “upper” and “lower” regions (Figure 1C & 1D). The results from the meta-analysis provide mechanistic insights to potential oncogenic drivers and some clinical and therapeutic implications for mucosal melanoma.

Figure 1:

Mutational landscape of Mucosal Melanoma. Molecular classification of melanoma with BRAF (V600), NRAS (G12, G13, Q61), NF1, KIT and SF3B1 mutations in (A) Mucosal melanoma meta-analysis from 64 studies (B) cutaneous melanoma from TCGA. (C-D) The difference in molecular classifications between mucosal melanomas arising in upper and lower anatomical sites (C) Upper sites include: Head and neck and upper GI. (D) Lower sites include: Lower GI, anorectal, and genital.

3.1. MAPK pathway

The mitogen-associated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway is an important intracellular signaling pathway and is commonly activated in melanoma, promoting tumorigenesis. The MAPK pathway responds to extracellular binding of growth factors to receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), that activates downstream signaling starting with activation of a GTPase (Ras) followed by tyrosine kinases that are activated by phosphorylation. The signal transduction typically includes activation of the following proteins: Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK. In cutaneous melanoma, the MAPK pathway is commonly activated by mutations in the key signaling components, BRAF, NRAS and NF1. Recently, the Cancer Genome Atlas Network (TCGA) proposed a genomic classification for cutaneous melanoma defined by four subgroups, each harboring mutations in BRAF, NRAS, NF1, or “triple wildtype”, corresponding to tumors lacking these mutations25. Figure 1B outlines the cutaneous melanoma TCGA cohort as defined by the four subgroups, however for the purposes of this study, we define the triple wildtype group as “unknown”. A vast majority of cutaneous melanomas (94%) contain MAPK pathway activating mutations (BRAF, NRAS, NF1), whereas only a 28% of mucosal melanomas harbor these mutations (Figure 1 A–B). Although found at a lower rate, MAPK activating pathway mutations can be therapeutically targeted, thus it remains important to understand the role that mutations in the MAPK pathway may be playing in mucosal melanoma tumorigenesis.

BRAF is a serine/threonine kinase involved in signal transduction in the MAPK pathway promoting cellular proliferation and survival. The BRAF oncogene is found to be highly mutated at codon V600 in multiple cancers and known to occur in approximately 35–50% of cutaneous melanomas (Figure 1B). BRAF-V600 mutations result in constitutive activation of the BRAF protein, and hyperactive MAPK pathway activity promoting tumorigenesis. The MAPK pathway can be therapeutically targeted with FDA approved small molecule inhibitors directly targeting BRAF-V600 and MEK. Clinically, combined inhibition of BRAF and MEK has been approved for BRAF-mutated cutaneous melanoma26–28. For the current meta-analysis of mucosal melanoma, we focused on BRAF-V600 mutations, since those are known to strongly activate MAPK pathway and is a relevant clinical target. We observed that only approximately 6% of mucosal melanomas harbor BRAF-V600 mutations (Figure 1A), which was seen at similar mutational rates in both the upper and lower mucosal melanoma regions (Figure 1C–D). Interestingly, in mucosal melanoma, there is an increased number of non-canonical BRAF mutations (L505H, G469A, L597R, and T599I), which are known to lead to weaker MAPK activation as compared to BRAF-V60029. However, it remains unclear if these non-canonical BRAF mutations will be clinically responsive to MAPK pathway inhibition, indicating the importance of understanding the effects of non-canonical BRAF mutations.

NRAS is an oncogene that is part of the Ras family of oncogenes that encode small GTP-binding proteins that respond to RTK activation and facilitate downstream activation of Raf. Activating point mutations in NRAS are commonly found at the G12, G13 and Q61 sites, which are the somatic mutations that we report for NRAS in our meta-analysis. Mucosal melanomas harbor NRAS mutations at a rate of 8%, which is lower than the rate seen in cutaneous melanoma (28%) (Figure 1A–B). Previous studies have reported conflicting observations regarding the enrichment of NRAS mutations in mucosal melanomas arising from upper or lower regions. In a pan-mucosal melanoma study, 10% (7/71) of tumors were NRAS mutated, at the G12, G13 or Q61 sites. Interestingly, they noticed that vaginal melanomas have a significantly higher proportion of NRAS mutations (43%) as compared to other mucosal melanoma subtypes, and were associated with a significantly worse overall survival30. However, a study of 16 esophageal melanomas identified NRAS (Q61, G12/13) mutations in 37.5% of cases (6/16)31, which the authors conclude that this data suggests that esophageal mucosal melanomas may display an enrichment of NRAS mutations. In the present study, we observed that there is not a significant difference in NRAS mutations in upper (13%) or lower (9%) region of mucosal melanomas (Figure 1C–D), suggesting that NRAS mutations may not be specific to a particular mucosal melanoma sub type.

NF1, Neurofibromin 1, is a negative regulator of Ras, and is commonly lost or harbors loss of function mutations in cancers, and thus is considered to be a tumor suppressor. Loss of NF1 is associated with increased MAPK pathway activity, and has been shown to be significantly enriched in cutaneous melanoma tumors lacking either BRAF or NRAS mutations22. In our current meta-analysis, we observed that NF1 is mutated at a rate of 14% in mucosal melanoma, which is also found at the same rate observed in the TCGA cohort of cutaneous melanoma (14%) (Figure 1 A–B). Of interest, one study found that NF1 was significantly co-mutated with KIT in 32% of mucosal melanomas, which is a significantly higher rate than in cutaneous melanoma (4%)21.

SPRED1 (sprout-related, EVH1 domain containing protein 1), a negative regulator of the MAPK pathway, recruits NF1 to the plasma membrane to convert active Ras-GTP into the inactive form bound to GDP. It has recently been reported that SPRED1 may function as a tumor suppressor in mucosal melanoma. SPRED1 loss was found in 26% (11/43) of mucosal melanomas, which included bi-allelic inactivation through either deep deletion or by truncating mutation combined with loss of the wild type SPRED1 allele32. Consistent with this, more recently Newell et. al. identified SPRED1 aberrations in 5 of 67 mucosal melanomas through whole genome sequencing7. Ablain et. al. observed a trend towards a pattern of mutual exclusivity with SPRED1 loss and NF1 loss of function mutations, suggesting that SPRED1 loss and NF1 loss may play similar roles in tumor progression in mucosal melanoma32. SPRED1 loss co-occurred significantly with KIT alterations (30%, 7/23 cases). In vitro and in vivo models demonstrated that in the context of KIT mutations, SPRED1 loss resulted in increased MAPK pathway activity and conferred resistance to the KIT tyrosine kinase inhibitor dasatinib. These results lay the groundwork to establish SPRED1 as a tumor suppressor gene that cooperates with activating KIT mutations to sustain MAPK signaling and may confer resistance to KIT inhibition. However, the clinical impact of SPRED1 loss remains to be defined in mucosal melanoma.

3.2. Receptor Tyrosine Kinase: KIT

KIT is a transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) that is commonly expressed in a variety of normal cell types, and its activation plays an important role in normal melanocyte development regulating growth, differentiation and migration33. Once it is activated through dimerization, it regulates the activation of several oncogenic downstream signaling pathways such as MAPK and AKT pathways33. The common KIT alterations observed in melanomas are amplifications and missense mutations, which occur throughout the coding region at a high frequency in the juxta-membrane autoinhibitory domain (encoded by exon 11) and the tyrosine kinase domains (encoded by exons 12–21)34. In the current meta-analysis, we reported all non-synonymous KIT mutations in mucosal melanoma. We found KIT mutations at a rate of 13% in all mucosal melanomas, and we observed a similar frequency in both upper (15%) and lower (13%) regions (Figure 1C–D). While KIT mutations are found at a lower rate in cutaneous melanoma, previous reports identify that cutaneous melanomas lacking recurrent mutations in BRAF or NRAS have a significant enrichment of alterations in KIT22. Given that KIT mutations are enriched in mucosal melanomas, it is important to understand the clinical implications of KIT mutations as a prognostic factor, as there are conflicting reports on the prognostic impact.

In a cohort of 86 French patients, of various mucosal melanomas, 11.6% (5/96) harbored KIT mutations, however there was no prognostic impact of KIT mutant patients compared to KIT wild type patients35. Further, in a pan mucosal melanoma study, KIT mutations were most frequently found in 35% (8/23) mucosal melanomas of the vulva as compared to all other sites30. Additionally, when KIT protein levels were analyzed by immunohistochemistry, there was a significant increase in KIT protein expression in KIT mutant tumors as compared to KIT wildtype tumors. There was no significant association with KIT mutational status or KIT protein expression on overall survival. In a 28 patient cohort, mixed with nasal and oral mucosal melanomas, 25% (7/28) of patients harbored KIT mutations. Again, there was no prognostic impact of KIT mutations as compared to KIT wildtype patients in this cohort36. In contrast to the previously mentioned studies, KIT mutational analysis from a large cohort of 755 mucosal melanoma Asian patients found that KIT mutant positive patients (8.7%, 66/755) had worse overall survival in mucosal melanomas, as compared to NRAS and BRAF mutations, which did not have any effect on prognosis37.

However, it is important to note that none of these previously mentioned studies of the prognostic factor of KIT mutations was done in the context of KIT targeted therapy, which is discussed in section 4.2. Further, these studies did not address the differential effect on prognosis based off of the location of the KIT mutation, which is suggested to play a role in the sensitivity of response to KIT inhibition.

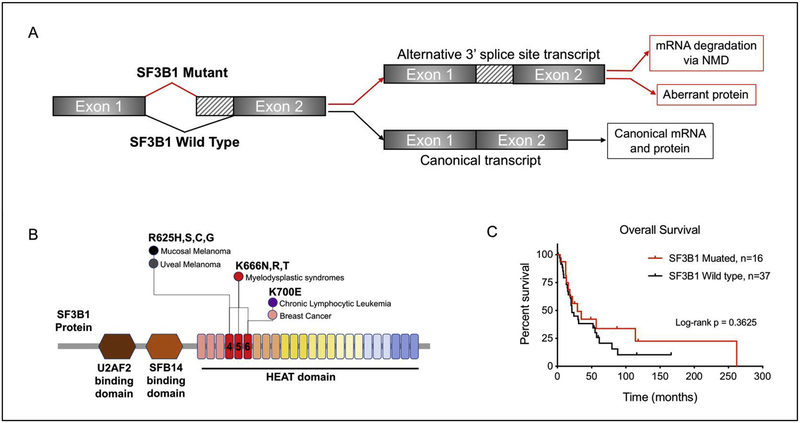

3.3. mRNA splicing factor: SF3B1

The spliceosomal protein SF3B1 is a core component of the U2 snRNP which recognizes the branch point sequence at the 3’ splice site at intron-exon junctions. One of the major roles of SF3B1 is RNA splicing, which involves the removal of nucleotide sequences from precursor RNAs into mature RNA transcripts. Mutations in SF3B1 are considered to be neomorphic resulting in alternative splicing that promotes global transcriptomic dysregulation38,39. The fate of alternatively spliced transcripts can either be (1) translation into aberrant proteins, or (2) undergo nonsense mediated decay (NMD) resulting in downregulation at the mRNA and protein levels (Figure 2A)40.

Figure 2:

SF3B1 mutations in cancer. (A) Mutations in SF3B1 are associated with alternative branch point usage and result in increases in alternative 3’ splice sites. (B) Hotspot SF3B1 mutations represented in SF3B1 protein, highlighting the locations that predominate in specific cancer types. (C) Kaplan-Meier curve of overall survival comparing SF3B1 Mutant (n=16) and SF3B1-WT (n=37) from 3 studies (Hintzsche et. al. 2017, Yang et. al. 2017, Quek et. al. 2019), p-value is calculated by log-rank test.

SF3B1 mutations have been identified in myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)41, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)42, prostate cancer43, breast cancer44, and uveal melanomas4,45 (Figure 2B). The C-terminal domain of SF3B1 contains 22 HEAT domains (Huntington, elongation factor 3, protein phosphatase 2A, and the yeast PI3-Kinase TOR1), where hotspot mutations are typically localized in domains 4–6 (Figure 2B)46. Across cancer types, SF3B1 mutations are heterozygous and enriched for the R625, K666 and K700 residues, here defined as “canonical hotspot mutations”. Interestingly, SF3B1 mutations in mucosal and uveal melanoma are almost exclusively enriched for the R625 residue, which is found at a lower frequency in hematologic malignancies and breast cancer, where the K666 and K700 residues predominate (Figure 2B). While SF3B1-R625 is found at a high frequency in mucosal melanoma and we consider it to be a canonical hotspot mutation, it remains unclear how additional non-canonical HEAT domain mutations may affect SF3B1 function. Thus, for our current meta-analysis we reported all non-synonymous SF3B1 mutations in mucosal melanoma. Interestingly, we observed that SF3B1 mutations may be enriched in lower regions of mucosal melanomas (27%) as compared to the mucosal melanomas in the upper regions (7%) (Figure 1 C–D). In support of our observation, recent studies using WES or WGS on oral mucosal melanomas (n=84) failed to identify any mutations in SF3B15,20.

Hintzsche et. al. observed that SF3B1 mutations were present in 7/19 (35%) of mucosal melanomas, the most common sites being anorectal (3/5,60%) and vulvovaginal (4/9, 44.4%), as compared to nasopharyngeal (1/5, 20%). It is important to note that only the lower regions of mucosal melanomas (anorectal and vulvovaginal) harbored SF3B1-R635 hotspot mutations, whereas the upper regions (nasal) harbored a non-canonical SF3B1-E1105G mutation located in the HEAT domain of SF3B121. In agreement, Quek et. al. observed that SF3B1 mutations were the most common mutation (6/27, 22%), where SF3B1-R625 hotspot mutations were enriched (5/6, 83%) and were exclusively found in vulvovaginal (5/19, 26%) and anorectal (3/5, 60%) sites, as compared to oral and nasal locations. Furthermore, SF3B1 mutations were associated with shorter overall and progression free survival (34.9 and 16.9 months, respectively) compared to SF3B1 wild type mucosal melanomas (79.9 and 35.7 months, respectively)47. We performed meta-analysis of SF3B1 mutations on overall survival from three mucosal melanoma studies (total patients, n=53) and found that SF3B1 mutations trend towards an increase in overall survival (Figure 2C). The differential effect of clinical outcomes associated with SF3B1 mutations indicates that the prognostic value of SF3B1 mutations still needs to be explored in a larger patient cohort.

3.4. Structural variants and fusion genes in mucosal melanoma

Whole genome sequencing provides the platform for the analysis of structural variants at the genome-scale4,6. WGS has been performed in an oral mucosal melanoma cohort, and the authors identified specific structural variants were associated with worse prognosis5. Specifically, patients with clustered inter-chromosomal translocations between chromosome 5 and chromosome 12 have significantly worse overall survival (9.0 vs 28.0 months, respectively)5. Additionally, break fusion bridges, characterized by the loss of telomeric regions and a high number of inversions, were tightly associated with a worse prognosis (median overall survival 9.0 vs 34.0 months)5.

BRAF fusion genes represent an alternate mechanism of MAPK pathway activation and are commonly identified in identified in a small percentage of “Triple-Wild Type” tumors, lacking BRAF, NRAS or NF1 mutations, in cutaneous melanoma48. The frequency of BRAF fusions in mucosal melanoma is comparable to the frequency of BRAF fusions found in triple wild type cutaneous melanomas49. Kim et. al. discovered and biologically characterized a novel BRAF fusion (ZNF767-BRAF) in a vemurafenib resistant respiratory tract mucosal melanoma patient. This BRAF fusion was the result of two successive microhomolgy mediated end joining of exon 1 of ZNF767 with exon 11 of BRAF, retaining the kinase domain of BRAF. ZNF767 is a pseudogene, and its biological role remains unclear. Melanoma cells harboring the ZNF767-BRAF fusion displayed resistance to the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib in vitro, which recapitulated the clinical response seen in the mucosal melanoma patient harboring the BRAF fusion, but demonstrated sensitivity to the MEK inhibitor trametinib in vitro49. Mechanistically, the ZNF767-BRAF fusion activates the MAPK pathway through the formation of RAF homo- and hetero-dimers. Lastly, the ZNF767-BRAF fusion cells were sensitive to MEK inhibition with either the combination of PI3K or CDK4/6 inhibitors in vitro and in vivo49.

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) fusions are oncogenic and occur in 3–7% of NSCLC, and clinically are sensitive to small molecule inhibitors targeting ALK. ALK fusions have been identified in ~11% of cutaneous melanomas, however the clinical impact of ALK fusions in melanoma has been understudied. Recently, Couts et. al. identified a mucosal melanoma that contained several novel EML4-ALK fusion variants, and was sensitive to ALK inhibition in vitro and in vivo. Interestingly, a novel ALK isoform, ALK-ATI, was also identified. ALK-ATI results from an alternative transcript initiation site located in intro 19 that includes a portion of intron 19 and exons 20–2950. In other cancers it was previously shown that ALK-ATI induces tumorigenesis and sensitized cells to ALK inhibitors. Couts et. al. also identified a subset of mucosal melanomas that expressed ALK-ATI, however, these cells were not sensitive to ALK inhibition in vitro and in vivo.

3.5. Copy number alterations in mucosal melanoma

One of the benefits of WGS is the ability to assess genome-wide copy number variations (CNV) in mucosal melanoma. Whole genome sequencing of 65 oral mucosal melanomas identified significant amplifications in KIT, TERT, CDK4, CCND1 and NOTCH2; along with significant losses in CDKN2A/B and TP535. Amplifications in the 12q13–15, containing CDK4 and TERT, in >50% of oral mucosal melanomas (33/65 samples), representing the most commonly altered genomic region. In addition, chromosome 5p15, containing TERT, was also significantly co-associated with CDK4 amplifications, suggesting a potential functional relevance of TERT and CDK4 as co-amplified genes. A small whole exome sequencing study of 19 oral mucosal melanomas identified that 11/19 (57.9%) harbored amplifications of chromosome 12q14, which contains CDK420. However, whole exome and whole genome studies of other subtypes of mucosal melanoma, such as head and heck, vulvovaginal and anorectal, did not describe the presence of chromosome 12q14 or CDK4 amplifications4,21,24,32,47,51. This warrants further interrogation of CDK4 amplification status in other subtypes of mucosal melanoma.

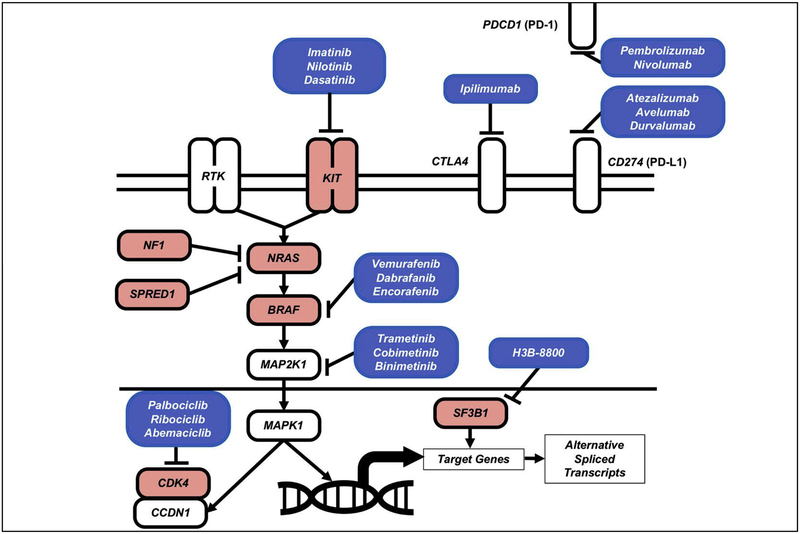

4. Precision medicine: Druggable targets and immunotherapy in mucosal melanoma

One of the immediate clinical implications from the mutational analysis is the identification of actionable driver mutations for mucosal melanoma. Leveraging the success from the development of targeted therapies, many of the identified mutations in mucosal melanoma have drugs or clinical investigated compounds available to treat these patients (Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Oncogenic signaling and therapeutic targets in Mucosal Melanoma.

4.1. BRAF and MEK kinase inhibitors

BRAF mutations result in hyperactivation of MAPK pathway signaling and represent a promising therapeutic target in mucosal melanoma. The ATP-competitive small molecule inhibitors (vemurafenib, dabrafenib and encorafinib) specifically targeting mutant BRAF have resulted in remarkable responses in cutaneous melanoma patients harboring BRAF-V600 mutations, increasing progression free survival and overall survival when compared to chemotherapy52,53. More strikingly the combination of BRAF and MEK inhibitors have demonstrated superior clinical benefits over BRAF inhibitor monotherapy. There are currently three FDA approved non-ATP competitive allosteric inhibitors of MEK which target MEK1 (cobimetinib) or both MEK1 and MEK2 (trametinib and binimetinib). Dual inhibition of BRAF and MEK with the combination of the following BRAF/MEK inhibitors vemurafenib/cobimetinib, dabrafenib/trametinib and encorafinib/bimimetinib are FDA approved for the treatment of BRAF mutant metastatic melanoma26–28. Based on promising results of the combination of BRAF and MEK inhibition in cutaneous melanoma, these BRAF/MEK inhibitors represent an attractive treatment option for BRAFV600 mutant mucosal melanoma patients.

Although mucosal melanomas do not harbor a high rate of BRAF mutations, they do have a high rate of NF1 alterations. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that tumors with alterations in NF1, either loss of function mutations or deletions, are more resistant to BRAF inhibitors54. Thus, it remains important to understand how NF1 mutations, RAS mutations and other mutations that activated the MAPK pathway may be targeted by MEK inhibition. Recent reports in cutaneous melanoma suggest that BRAF fusions may function as a novel resistance mechanism to vemurafenib through promoting reactivation of the MAPK pathway55. Further preclinical and clinical research needs to be conducted to identify the best targeted therapy for such BRAF fusions, and mucosal melanomas should be screened for such fusions as they may represent sensitivity to MEK inhibition.

4.2. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Clinical trials in KIT mutant tumors, such as gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) and cutaneous melanoma, have observed that patients with KIT exon 11 or exon 13 mutations are shown to have a better response to KIT targeted therapy, suggesting that certain KIT alterations may be more sensitive to KIT inhibition30,56. There are a number of small molecule tyrosine kinase KIT inhibitors, such as imatinib, nilotinib and dasatinib, that have shown variable clinical activity in the treatment of KIT mutated mucosal melanoma.

Imatinib:

Imatinib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) that targets KIT, BCR-ABL and platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA)57. A seminal study demonstrated that certain KIT alterations may render the tumor more or less sensitive to KIT targeted therapy with imatinib in metastatic melanoma. This open arm phase II trial with imatinib in 25 patients with KIT mutant metastatic melanoma, consisting of mucosal (n=13), acral (n=10) and chronically sun-damaged (CSD) (n=5) subtypes, displaying a range of mutations in exons 9, 11, 13, 17 and 18 of KIT (21/25). KIT amplifications were present in 15/25 patients and co-occurred with mutations in 11/25 patients. In this study, the overall durable response rate of 16%, with a median time to progression of 12 weeks, and a median overall survival of 10.7 months. There was no significant association with clinical melanoma subtype and response to imatinib. Two patients achieved durable complete responses, and harbored a KIT-L576P mutation in exon 11 and amplification. Patients harboring recurrent KIT mutations previously identified in GIST and melanoma (V559C, L576P, V642E and N822J), had a higher proportion of response (46%) compared to other KIT mutations. Furthermore, all patients with a partial, durable or complete response (n=6) harbored either L576P or K642E KIT mutations. In addition, tumors with a mutant KIT allele in greater abundance that the wild type KIT allele demonstrated a better response rate, time to progression and overall survival as compared to other cases. This study suggests that some KIT mutations, such as L576P and K642E, may possess a greater oncogenic driver capacity, and thus increased sensitivity to KIT inhibition34.

Consistent with this clinical observation, several phase II clinical trials were conducted to evaluate the clinical benefit of imatinib in KIT mutated melanoma patients, including mucosal melanoma58–60. Taken together, these clinical studies of treating KIT-mutated mucosal patients observed response rates that ranged from 20%−30%. Overall, KIT-mutated patients, as compared to patients with KIT amplifications, have better clinical responses to imatinib and the mutations in exons 11 and 13 were more predictive of imatinib response as compared to other KIT mutations. These clinical studies warrant further investigation of treating imatinib for KIT-mutated mucosal melanoma.

Nilotinib:

Nilotinib is a second-generation TKI structurally derived from imatinib, and has a similar target profile to imatinib but exhibits greater potency does not require an active transport mechanism to enter cells. Nilotinib binds to and inhibits KIT, DDR, ABL/BCR-ABL, PDGF and several EPH RTKs, and maintains activity against a variety of KIT mutations in exons 9, 11 and 1361. One of the first clinical trials with nilotinib in KIT altered metastatic melanoma, including mucosal melanoma, tested the clinical efficacy in two cohorts, one that was refractory to previous KIT targeted therapy (cohort A), with the other testing nilotinib in KIT-mutant patients with CNS metastasis (cohort B)62. The primary endpoint of this study was to determine the proportion of patients who were alive and without progression of disease 4 months post nilotinib treatment. The cohort included 19 patients, with 90% (17/19) patients harbored KIT mutations, consisted of acral, CSD and mucosal melanoma, with mucosal consisting of 63% (12/19) patients, 5 of which harbored CNS brain metastases. Of note, 17/19 patients previously received prior treatment with imatinib. Patients in cohort A, previously treated with imatinib, displayed a time to progression (TTP) of 3.4 months and an OS of 14.2 months. In cohort A, 3/11 patients achieved disease control at 4 months, with a range of progression free survival times of 5.5, 11.5 and 37.5+ months. Of interest, two patients achieved durable partial responses to nilotinib, both of which had previously demonstrated either a partial or complete response to imatinib, 12.4 and 20 months, respectively, demonstrating that nilotinib has a clinical effect in overcoming acquired resistance to imatinib. Both of the responding patients had mucosal melanoma harboring either L576P or K642E KIT mutations. Patients in cohort B, with CNS involvement, had a TTP of 2.6 months, and a short OS of 4.3 months. One partial response was observed in an anorectal mucosal melanoma with CNS involvement, harboring a V560D KIT mutation, however this patient did not receive prior imatinib therapy.

Additional phase II clinical trials with nilotinib in KIT-mutated melanoma patients (including mucosal melanoma) exhibited similar responses as seen with imatinib, and observed an average overall response rate of 20.9% (range 16.7%−26.2%)63–65. For example, the French Skin Cancer network conducted a phase II study using nilotinib in 25 patients with metastatic melanoma having KIT mutations or amplifications, where mucosal melanoma accounted for 40% of the patients (n=10)65. At 6 months, there was a 16% overall response rate, which included three patients with a partial response and one patient with a complete response to nilotinib. In this cohort, KIT mutations in exon 11 and 13 were the most common and found in 44% and 32% of patients, respectively. Furthermore, all patients with partial or complete response had either exon 11 or 13 mutations. This study collected serial tumor biopsies at baseline and post nilotinib treatment from 8 patients and monitored oncogenic signaling pathways downstream of KIT, such as the MAPK, PI3K/AKT and JAK/STAT pathways. At baseline, all tumors were positive for phosphorylation of STAT3 at the Serine-727 site, which is implicated in tumorigenesis and survival in melanoma. Following nilotinib treatment, phospho-STAT3 levels significantly decreased in good responders, and remained unchanged in poor responders. This data suggests a phospho-STAT3 levels as potential biomarker of response to nilotinib and warrants future investigation into the mechanism of KIT inhibition, potentially through downregulation of STAT3, in melanoma.

Dasatinib:

Dasatinib is another multi-kinase “second-generation” small molecule inhibitor that targets KIT, BCR-ABL, PDGFR-β and the SRC family kinases. Previous preclinical studies demonstrated that dasatinib has superior activity compared to other KIT inhibitors such as imatinib. However, this did not prove to be true in a two stage phase II clinical trial for 73 patients with locally advanced or stage IV melanoma, where 52% (n=38) of patients had mucosal or vulvovaginal melanoma treated with dasatinib66. Stage one consisted of 51 total patients, where 3 patients harbored KIT mutations, and 6 patients were not tested (n=51 total patients). However, the patients that achieved a partial response (n=3) did not harbor KIT mutations. In stage two of the study, only KIT mutant positive melanomas were tested (n=22), and 7/22 patients had a partial response, all containing either exon 11 or exon 13 mutations, but did not include L576P mutations. Patients harboring KIT mutations in exon 11 or 13 demonstrated a median progression free survival of 4.7 months and a median overall survival of 12.3 months. In this study, KIT mutational status had no significant effect in progression free and overall survival with dasatinib. There were no complete responses observed in either stage one or stage two. It is important to note that KIT amplifications were not tested in this cohort.

Other Kinase inhibitors:

From the published studies, a small subset of mucosal melanoma patients may harbor gene fusions and could be exploited as therapeutic targets. In a recent study, a cell line derived from mucosal melanoma was detected to harbor EML4-ALK fusion and responded to ALK inhibitors such as crizotinib and ceritinib in vitro and in vivo50. This preclinical data indicates that targeting ALK fusions may represent a therapeutic option. This highlights the importance of screening patients for ALK rearrangements and alternative isoforms in mucosal melanoma as patients may benefit for the targeted treatment for these gene fusions.

4.3. Spliceosomal inhibitors

From the recent WES/WGS studies, SF3B1 was found to be commonly mutated in ~15% in mucosal melanoma. In vitro analysis of a subset of alternatively spliced genes identified in SF3B1 mutant breast cancer and uveal melanoma was validated in a cohort of SF3B1-R625 mutant mucosal melanomas21. This demonstrates that SF3B1-R625 mutations are functionally involved in alternative splicing in mucosal melanoma. Currently, no drugs have been approved by FDA for targeting SF3B1-mutant patients, however, several compounds have been recently developed targeting the spliceosome, that has shown preferential lethality for SF3B1-mutant cells in preclinical studies67. The leading clinical investigated compound is H3B-8800, which is an orally available spliceosomal inhibitor entering phase I clinical trials patients with advanced myeloid malignancies, including patients with SF3B1-mutations68. In the future, this compound could be investigated in mucosal melanoma patients harboring mutations in SF3B1.

4.4. Cell cycle inhibitors

Cell cycle progression from G1 (pre-DNA synthesis) to S phase (DNA synthesis) commonly results from activation of CDK4/6 and forms a complex with Cyclin D1 (CCND1) and hyper-phosphorylates retinoblastoma (RB), leading to dissociation of RB from and activation of transcription factor E2F, and cell cycle progression. Inhibition of CDK4/6 with small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors result in ablation of CDK4/6 kinase activity and result in RB remaining dephosphorylated and bound to E2F, preventing cell cycle progression. Currently there are three FDA approved drugs, palbociclib, ribociclib and abemaciclib, that target CDK4/6, which are used for the treatment of hormone receptor positive, HER2 negative advanced breast cancer69. The anti-tumor effect of palbociclib, was used in an in vivo study with oral mucosal melanoma patient derived xenograft (PDX) harboring CDK4 amplification and resulted in sustained tumor suppression for 8 weeks, which was not observed in a CDK4 wildtype PDX model5. Suggesting that oral mucosal melanomas harboring CDK4 amplifications may be more likely to benefit from palbociclib treatment. Given that there is a subset of mucosal melanomas that harbor CDK4 amplifications, and CDKN2A gene deletions, these patients may be candidates for CDK4/6 inhibition.

4.5. Immunotherapy in Mucosal Melanoma.

Immunomodulatory antibodies directly effecting and enhancing the function of T cells have shown promising results in many cancers, especially cutaneous melanoma. Such agents are referred to as “check point inhibitors”, and function to block negative regulators of T cell immunity such as cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1). Three immune check point monoclonal antibody inhibitors are currently approved for patients with metastatic cutaneous melanoma that either target CTLA-4 (ipilimumab) or PD-1 (nivolumab and pembrolizumab). One of the biggest hurdles in understanding the mechanism of response to immunotherapies is the lack of large studies analyzing the efficacy of anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 in mucosal melanoma.

Recently, pooled retrospective analysis of immunotherapy responses from clinical trials have been published and have shown that single agent anti-PD-1 may be more effective that anti-CTLA-4 in mucosal melanoma. One single center cohort analysis of 44 mucosal melanoma patients analyzed the response to either anti-PD-1 (n=20) or anti-CTLA-4 (n=24), and found that the overall response rate (ORR) for both therapies was 20%70. However, when stratifying by treatment, patients treated with anti-PD-1 demonstrated an increased ORR compared to anti-CTLA-4, 35% vs 8%, respectively. In line with this, anti-PD-1 therapy demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in progression free survival (PFS), but not in overall survival, compared to anti-CTLA-4, which was independent of primary tumor site.

Mignard et. al. analyzed the response to immunotherapy (n=151) compared to chemotherapy (n=78) in mucosal melanoma, and observed that the median overall survival of patients treated with immunotherapy (OS: 15.97 months) was significantly longer than treatment with chemotherapy (OS: 8.82 months). Consistent with previous studies, this group observed higher response rates in patients receiving anti-PD1 (20%) as compared to patients receiving anti-CTLA-4 (3.9%), suggesting that anti-PD1 as a single agent may be more effective than anti-CTLA-471.

A retrospective multicenter analysis evaluated the efficacy of anti-PD-1, either nivolumab or pembrolizumab, in 35 patients with MM, and found that the objective response rate was 23%, consisting of all partial responses72. The median progression free survival was 3.9 months, and the responses were not dependent on the primary site of disease. Of the 80% of patients received prior systemic therapy, 93% received anti-CTLA4 (ipilimumab), and a majority of patients (92%) did not respond, again highlighting the limited efficacy of anti-CTLA-4. Mutational analysis identified that 64% of patients lacked driver mutations in BRAF, NRAS and KIT. Interestingly, this study found that the responses to anti-PD-1 therapy were not associated with primary tumor location, mutational burden or primary therapy, and may overcome therapeutic resistance to anti-CTLA-4, supporting the routine use of PD-1 blockade for patients with unresectable mucosal melanoma.

A pooled analysis from phase III clinical trials comparing immunotherapy responses in mucosal and cutaneous melanoma found that the combination of anti-PD1 and anti-CTLA-4 demonstrated a superior objective response rate of 37.1% as compared to single agent treatment with anti-PD-1 (23.3%) or anti-CTLA-4 (8.3%) in mucosal melanoma73. While mucosal melanomas showed a favorable response to combination immunotherapy, the rates were still lower when compared to cutaneous melanoma (60.4%), which is consistent with previous clinical observations in cutaneous melanoma. This study analyzed the role of PD-L1 expression (measured by immunohistochemistry) as a clinical biomarker of response to immunotherapy, however it remains unclear in both mucosal and cutaneous melanoma.

More recently, the FDA has approved several PD-L1 inhibitors (atezalizumab, avelumab, durvalumab) as another class of immunotherapy in cancer. These PD-L1 inhibitors should be evaluated in the mucosal melanoma, either alone or in combination with other drugs as another therapy option to this rare disease. More pre-clinical and clinical studies are needed to better understand predictive biomarkers and identify mucosal melanoma patients responsive to immunotherapy.

5. Concluding Remarks

In summary, the mutational landscape of mucosal melanoma is significantly different from cutaneous melanoma. The common drivers (BRAF and NRAS) found in cutaneous melanoma have lower mutation rate in mucosal melanoma. However, SF3B1 and KIT have higher mutation rate in mucosal melanoma as compared to cutaneous melanoma. From the meta-analysis, we also observed that the mutational profiles are slightly different between the “upper” and “lower” regions of mucosal melanoma, providing new insights and therapeutic options for the mucosal melanoma patients. This review highlights the need to perform meta-analysis to further define the mutational landscape of mucosal melanoma, and further established and developed new preclinical models to study rare cancers. Mutations identified in mucosal melanoma should be incorporated into routine clinical testing, as there are targeted therapies already developed for treating patients with these mutations in the precision medicine era.

Acknowledgements:

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health P50CA058187, P30CA046934, T32CA190216 (KWN), the RNA Bioscience Initiative RNA Scholars Program (KWN) at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, and the David F. and Margaret T. Grohne Family Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Postow MA, Hamid O & Carvajal RD Mucosal Melanoma: Pathogenesis, Clinical Behavior, and Management. Curr. Oncol. Rep 14, 441–448 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lian B et al. The Natural History And Patterns Of Metastases From Mucosal Melanoma: An Analysis Of 706 Prospectively-Followed Patients. Ann. Oncol 28, mdw694 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mihajlovic M, Vlajkovic S, Jovanovic P & Stefanovic V Primary mucosal melanomas: a comprehensive review. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol 5, 739–53 (2012). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furney SJ et al. Genome sequencing of mucosal melanomas reveals that they are driven by distinct mechanisms from cutaneous melanoma. J. Pathol 230, 261–269 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou R et al. Analysis of mucosal melanoma whole-genome landscapes reveals clinically relevant genomic aberrations. Clin. Cancer Res. clincanres.3442.2018 (2019). doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-3442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayward NK et al. Whole-genome landscapes of major melanoma subtypes. Nature 545, 175–180 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newell F et al. Whole-genome landscape of mucosal melanoma reveals diverse drivers and therapeutic targets. Nat. Commun 10, 3163 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackintosh JA The Antimicrobial Properties of Melanocytes, Melanosomes and Melanin and the Evolution of Black Skin. J. Theor. Biol 211, 101–113 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tjoa T & Emerick K Mucosal Melanoma in Melanoma 1–14 (Springer; New York, 2018). doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-7322-0_4-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang X, Si L & Guo J Treatment algorithm of metastatic mucosal melanoma. Chinese Clin. Oncol 3, 38 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tyrrell H & Payne M Combatting mucosal melanoma: recent advances and future perspectives. Melanoma Manag. 5, MMT11 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lerner BA, Stewart LA, Horowitz DP & Carvajal RD Mucosal Melanoma: New Insights and Therapeutic Options for a Unique and Aggressive Disease. Oncology (Williston Park). 31, e23–e32 (2017). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spencer KR & Mehnert JM Mucosal Melanoma: Epidemiology, Biology and Treatment. in Cancer treatment and research 167, 295–320 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carvajal RD, Spencer SA & Lydiatt W Mucosal melanoma: a clinically and biologically unique disease entity. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw 10, 345–56 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yde SS, Sjoegren P, Heje M & Stolle LB Mucosal Melanoma: a Literature Review. Curr. Oncol. Rep 20, 28 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coté TR & Sobin LH Primary melanomas of the esophagus and anorectum: epidemiologic comparison with melanoma of the skin. Melanoma Res. 19, 58–60 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuk D et al. Prognosis of Mucosal, Uveal, Acral, Nonacral Cutaneous, and Unknown Primary Melanoma From the Time of First Metastasis. Oncologist 21, 848–54 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelly P, Zagars GK, Cormier JN, Ross MI & Guadagnolo BA Sphincter-sparing local excision and hypofractionated radiation therapy for anorectal melanoma. Cancer 117, 4747–4755 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benlyazid A et al. Postoperative Radiotherapy in Head and Neck Mucosal Melanoma. Arch. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 136, 1219 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lyu J et al. Whole-exome sequencing of oral mucosal melanoma reveals mutational profile and therapeutic targets. J. Pathol 244, 358–366 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hintzsche JD et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies recurrent SF3B1 R625 mutation and comutation of NF1 and KIT in mucosal melanoma. Melanoma Res. 27, 189–199 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodis E et al. A Landscape of Driver Mutations in Melanoma. Cell 150, 251–263 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krauthammer M et al. Exome sequencing identifies recurrent somatic RAC1 mutations in melanoma. Nat. Genet 44, 1006–1014 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong K et al. Cross-species genomic landscape comparison of human mucosal melanoma with canine oral and equine melanoma. Nat. Commun 10, 353 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akbani R et al. Genomic Classification of Cutaneous Melanoma. Cell 161, 1681–1696 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larkin J et al. Combined Vemurafenib and Cobimetinib in BRAF-Mutated Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med 371, 1867–1876 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Long GV et al. Adjuvant Dabrafenib plus Trametinib in Stage III BRAF-Mutated Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med 377, 1813–1823 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dummer R et al. Encorafenib plus binimetinib versus vemurafenib or encorafenib in patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma (COLUMBUS): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 19, 603–615 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wan PT et al. Mechanism of Activation of the RAF-ERK Signaling Pathway by Oncogenic Mutations of B-RAF. Cell 116, 855–867 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Omholt K, Grafström E, Kanter-Lewensohn L, Hansson J & Ragnarsson-Olding BK KIT pathway alterations in mucosal melanomas of the vulva and other sites. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 3933–42 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sekine S, Nakanishi Y, Ogawa R, Kouda S & Kanai Y Esophageal melanomas harbor frequent NRAS mutations unlike melanomas of other mucosal sites. Virchows Arch. 454, 513–517 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ablain J et al. Human tumor genomics and zebrafish modeling identify SPRED1 loss as a driver of mucosal melanoma. Science (80-.). 362, 1055–1060 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ronnstrand L Signal transduction via the stem cell factor receptor/c-Kit. Cell. Mol. Life Sci 61, 2535–2548 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carvajal RD et al. KIT as a Therapeutic Target in Metastatic Melanoma. JAMA 305, 2327 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cinotti E et al. Mucosal melanoma: clinical, histological and c-kit gene mutational profile of 86 French cases. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatology Venereol 31, 1834–1840 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Mendonça UBT et al. Analysis of KIT gene mutations in patients with melanoma of the head and neck mucosa: a retrospective clinical report. Oncotarget 9, 22886–22894 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bai X et al. MAPK Pathway and TERT Promoter Gene Mutation Pattern and Its Prognostic Value in Melanoma Patients: A Retrospective Study of 2,793 Ca. Clin. Cancer Res 23, 6120–6127 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Darman RB et al. Cancer-Associated SF3B1 Hotspot Mutations Induce Cryptic 3’ Splice Site Selection through Use of a Different Branch Point. Cell Rep. 13, 1033–45 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang L et al. Transcriptomic Characterization of SF3B1 Mutation Reveals Its Pleiotropic Effects in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Cancer Cell (2016). doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Darman RB et al. Cancer-Associated SF3B1 Hotspot Mutations Induce Cryptic 3′ Splice Site Selection through Use of a Different Branch Point. Cell Rep. 13, 1033–1045 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Papaemmanuil E et al. Somatic SF3B1 mutation in myelodysplasia with ring sideroblasts. N. Engl. J. Med 365, 1384–95 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang L et al. SF3B1 and other novel cancer genes in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med 365, 2497–506 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Je EM, Yoo NJ, Kim YJ, Kim MS & Lee SH Mutational analysis of splicing machinery genes SF3B1, U2AF1 and SRSF2 in myelodysplasia and other common tumors. Int. J. cancer 133, 260–5 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maguire SL et al. SF3B1 mutations constitute a novel therapeutic target in breast cancer. J. Pathol 235, 571–80 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harbour JW et al. Recurrent mutations at codon 625 of the splicing factor SF3B1 in uveal melanoma. Nat. Genet 45, 133–5 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cretu C et al. Molecular Architecture of SF3b and Structural Consequences of Its Cancer-Related Mutations. Mol. Cell 64, 307–319 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quek C et al. Recurrent hotspot SF3B1 mutations at codon 625 in vulvovaginal mucosal melanoma identified in a study of 27 Australian mucosal melanomas. Oncotarget 10, 930–941 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turner J et al. Kinase gene fusions in defined subsets of melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 30, 53–62 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim HS et al. Oncogenic BRAF fusions in mucosal melanomas activate the MAPK pathway and are sensitive to MEK/PI3K inhibition or MEK/CDK4/6 inhibition. Oncogene 36, 3334–3345 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Couts KL et al. ALK Inhibitor Response in Melanomas Expressing EML4-ALK Fusions and Alternate ALK Isoforms. Mol. Cancer Ther. 17, 222–231 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hayward NK et al. Whole-genome landscapes of major melanoma subtypes. Nature 545, 175–180 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chapman PB et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N. Engl. J. Med 364, 2507–16 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hauschild A et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 380, 358–365 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cirenajwis H et al. NF1-mutated melanoma tumors harbor distinct clinical and biological characteristics. Mol. Oncol 11, 438–451 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kulkarni A et al. Biology of Human Tumors BRAF Fusion as a Novel Mechanism of Acquired Resistance to Vemurafenib in BRAF V600E Mutant Melanoma. (2017). doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meng D & Carvajal RD KIT as an Oncogenic Driver in Melanoma: An Update on Clinical Development. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol 20, 315–323 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Iqbal N & Iqbal N Imatinib: a breakthrough of targeted therapy in cancer. Chemother. Res. Pract 2014, 357027 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guo J et al. Phase II, open-label, single-arm trial of imatinib mesylate in patients with metastatic melanoma harboring c-Kit mutation or amplification. J. Clin. Oncol 29, 2904–9 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hodi FS et al. Imatinib for Melanomas Harboring Mutationally Activated or Amplified KIT Arising on Mucosal, Acral, and Chronically Sun-Damaged Skin. J. Clin. Oncol 31, 3182–3190 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ma X et al. The clinical significance of c-Kit mutations in metastatic oral mucosal melanoma in China. Oncotarget 8, 82661–82673 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cullinane C et al. Preclinical Evaluation of Nilotinib Efficacy in an Imatinib-Resistant KIT-Driven Tumor Model. Mol. Cancer Ther 9, 1461–1468 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carvajal RD et al. Phase II Study of Nilotinib in Melanoma Harboring KIT Alterations Following Progression to Prior KIT Inhibition. Clin. Cancer Res 21, 2289–2296 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee SJ et al. Phase II Trial of Nilotinib in Patients With Metastatic Malignant Melanoma Harboring KIT Gene Aberration: A Multicenter Trial of Korean Cancer Study Group (UN10–06). Oncologist 20, 1312–9 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Guo J et al. Efficacy and safety of nilotinib in patients with KIT-mutated metastatic or inoperable melanoma: final results from the global, single-arm, phase II TEAM trial. Ann. Oncol 28, 1380–1387 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Delyon J et al. STAT3 Mediates Nilotinib Response in KIT-Altered Melanoma: A Phase II Multicenter Trial of the French Skin Cancer Network. J. Invest. Dermatol 138, 58–67 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kalinsky K et al. A phase 2 trial of dasatinib in patients with locally advanced or stage IV mucosal, acral, or vulvovaginal melanoma: A trial of the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (E2607). Cancer 123, 2688–2697 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Seiler M et al. H3B-8800, an orally available small-molecule splicing modulator, induces lethality in spliceosome-mutant cancers. Nat. Med 24, 497–504 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Steensma DP et al. H3B-8800-G0001–101: A first in human phase I study of a splicing modulator in patients with advanced myeloid malignancies. J. Clin. Oncol 35, TPS7075–TPS7075 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 69.McCartney A et al. The role of abemaciclib in treatment of advanced breast cancer. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol 10, 1758835918776925 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moya-Plana A et al. Evaluation of the efficacy of immunotherapy for non-resectable mucosal melanoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother (2019). doi: 10.1007/s00262-019-02351-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mignard C et al. Efficacy of Immunotherapy in Patients with Metastatic Mucosal or Uveal Melanoma. J. Oncol 2018, 1–9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shoushtari AN et al. The efficacy of anti-PD-1 agents in acral and mucosal melanoma. Cancer 122, 3354–3362 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.D’Angelo SP et al. Efficacy and Safety of Nivolumab Alone or in Combination With Ipilimumab in Patients With Mucosal Melanoma: A Pooled Analysis. J. Clin. Oncol 35, 226–235 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang HM et al. Identification of recurrent mutational events in anorectal melanoma. Mod. Pathol (2016). doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hou JY et al. Vulvar and vaginal melanoma: A unique subclass of mucosal melanoma based on a comprehensive molecular analysis of 51 cases compared with 2253 cases of nongynecologic melanoma. Cancer 123, 1333–1344 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rouzbahman M et al. Malignant Melanoma of Vulva and Vagina. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis 19, 350–353 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cosgarea I et al. Targeted next generation sequencing of mucosal melanomas identifies frequent NF1 and RAS mutations. Oncotarget 8, 40683–40692 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zehir A et al. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat. Med 23, 703–713 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Iida Y et al. Predominance of triple wild-type and IGF2R mutations in mucosal melanomas. BMC Cancer 18, 1054 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Niu H-T et al. Identification of anaplastic lymphoma kinase break points and oncogenic mutation profiles in acral/mucosal melanomas. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 26, 646–653 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lyu J et al. Mutation scanning of BRAF, NRAS, KIT, and GNAQ/GNA11 in oral mucosal melanoma: a study of 57 cases. J. Oral Pathol. Med 45, 295–301 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rivera RS et al. C-kit protein expression correlated with activating mutations in KIT gene in oral mucosal melanoma. Virchows Arch. 452, 27–32 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wroblewska JP et al. SF3B1, NRAS, KIT, and BRAF Mutation; CD117 and cMYC Expression; and Tumoral Pigmentation in Sinonasal Melanomas: An Analysis With Newly Found Molecular Alterations and Some Population-Based Molecular Differences. Am. J. Surg. Pathol 43, 168–177 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Turri-Zanoni M et al. Sinonasal mucosal melanoma: Molecular profile and therapeutic implications from a series of 32 cases. Head Neck 35, 1066–1077 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chraybi M et al. Oncogene abnormalities in a series of primary melanomas of the sinonasal tract: NRAS mutations and cyclin D1 amplification are more frequent than KIT or BRAF mutations. Hum. Pathol 44, 1902–1911 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zebary A, Jangard M, Omholt K, Ragnarsson-Olding B & Hansson J KIT, NRAS and BRAF mutations in sinonasal mucosal melanoma: a study of 56 cases. Br. J. Cancer 109, 559–564 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Öztürk Sari Ş et al. BRAF, NRAS, KIT, TERT, GNAQ/GNA11 mutation profile analysis of head and neck mucosal melanomas: a study of 42 cases. Pathology 49, 55–61 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Antonescu CR et al. L576P KIT mutation in anal melanomas correlates with KIT protein expression and is sensitive to specific kinase inhibition. Int. J. Cancer 121, 257–264 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Santi R et al. KIT genetic alterations in anorectal melanomas. J. Clin. Pathol 68, 130–4 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Aulmann S et al. Comparison of molecular abnormalities in vulvar and vaginal melanomas. Mod. Pathol 27, 1386–1393 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.van Engen-van Grunsven ACH et al. NRAS mutations are more prevalent than KIT mutations in melanoma of the female urogenital tract—A study of 24 cases from the Netherlands. Gynecol. Oncol 134, 10–14 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tseng D et al. Oncogenic mutations in melanomas and benign melanocytic nevi of the female genital tract. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol 71, 229–236 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pappa KI et al. Low Mutational Burden of Eight Genes Involved in the MAPK/ERK, PI3K/AKT, and GNAQ/11 Pathways in Female Genital Tract Primary Melanomas. Biomed Res. Int 2015, 1–10 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Curtin JA et al. Distinct Sets of Genetic Alterations in Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med 353, 2135–2147 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.YUN J et al. KIT amplification and gene mutations in acral/mucosal melanoma in Korea. APMIS 119, 330–335 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Si L et al. Prevalence of BRAF V600E mutation in Chinese melanoma patients: Large scale analysis of BRAF and NRAS mutations in a 432-case cohort. Eur. J. Cancer 48, 94–100 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kong Y et al. Large-Scale Analysis of KIT Aberrations in Chinese Patients with Melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res 17, 1684–1691 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Satzger I et al. Analysis of c-KIT expression and KIT gene mutation in human mucosal melanomas. Br. J. Cancer 99, 2065–2069 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Torres-Cabala CA et al. Correlation between KIT expression and KIT mutation in melanoma: a study of 173 cases with emphasis on the acral-lentiginous/mucosal type. Mod. Pathol 22, 1446–1456 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schoenewolf NL et al. Sinonasal, genital and acrolentiginous melanomas show distinct characteristics of KIT expression and mutations. Eur. J. Cancer 48, 1842–1852 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Del Prete V et al. Noncutaneous Melanomas: A Single-Center Analysis. Dermatology 232, 22–29 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Abu-Abed S et al. KIT Gene Mutations and Patterns of Protein Expression in Mucosal and Acral Melanoma. J. Cutan. Med. Surg 16, 135–142 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wong CW et al. BRAF and NRAS mutations are uncommon in melanomas arising in diverse internal organs. J. Clin. Pathol 58, 640–4 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Edwards RH et al. Absence of BRAF mutations in UV-protected mucosal melanomas. J. Med. Genet 41, 270–2 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cohen Y et al. Exon 15 BRAF Mutations Are Uncommon in Melanomas Arising in Nonsun-Exposed Sites. Clin. Cancer Res 7, 1214–1220 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kang X-J et al. Analysis of KIT mutations and c-KIT expression in Chinese Uyghur and Han patients with melanoma. Clin. Exp. Dermatol 41, 81–87 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sakaizawa K et al. Clinical characteristics associated with BRAF, NRAS and KIT mutations in Japanese melanoma patients. J. Dermatol. Sci 80, 33–37 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Uhara H et al. NRAS mutations in primary and metastatic melanomas of Japanese patients. Int. J. Clin. Oncol 19, 544–548 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hsieh R et al. Mutational Status of NRAS and BRAF Genes and Protein Expression Analysis in a Series of Primary Oral Mucosal Melanoma. Am. J. Dermatopathol 39, 104–110 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Schaefer T, Satzger I & Gutzmer R Clinics, prognosis and new therapeutic options in patients with mucosal melanoma: A retrospective analysis of 75 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 96, e5753 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Pracht M et al. Prognostic and predictive values of oncogenic BRAF, NRAS, c-KIT and MITF in cutaneous and mucous melanoma. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatology Venereol 29, 1530–1538 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Greaves WO et al. Frequency and Spectrum of BRAF Mutations in a Retrospective, Single-Institution Study of 1112 Cases of Melanoma. J. Mol. Diagnostics 15, 220–226 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Minor DR et al. Sunitinib Therapy for Melanoma Patients with KIT Mutations. Clin. Cancer Res 18, 1457–1463 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kluger HM et al. A phase 2 trial of dasatinib in advanced melanoma. Cancer 117, 2202–2208 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Handolias D et al. Clinical responses observed with imatinib or sorafenib in melanoma patients expressing mutations in KIT. Br. J. Cancer 102, 1219–1223 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Abysheva SN et al. KIT mutations in Russian patients with mucosal melanoma. Melanoma Res. 21, 555–559 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Beadling C et al. KIT Gene Mutations and Copy Number in Melanoma Subtypes. Clin. Cancer Res 14, 6821–6828 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]