Abstract

The identification of broadly defined psychological traits which bestow vulnerability for the manifestation of addiction-like behaviors can guide the discovery of the neuronal mechanisms underlying the propensity for drug taking. Sign-tracking behavior in rats (STs) signifies the presence of a trait that predicts a relatively greater behavioral control of Pavlovian drug and reward cues than in rats that exhibit goal-tracking behavior (GTs). We previously demonstrated that relatively poor cholinergic-attentional control in STs is an essential component of the trait indexed by sign-tracking, and that this trait aspect contributes to the relatively greater power of drug cues to control the behavior of STs. Here we addressed the possibility that STs and GTs employ fundamentally different psychological mechanisms for the detection of cues in attention-demanding contexts. Rats were trained to perform an operant Sustained Attention Task (SAT). As task training advanced to the stage that taxed attentional control, the relative brightness of visual target signals significantly influenced detection performance in STs, but not GTs. This finding suggests that STs, but not GTs, rely on bottom-up, cue salience-driven mechanisms to detect cues. GTs may be able to resist behavioral control by Pavlovian drug cues by utilizing goal-directed decisional processes that minimize the influence of the salience of drug cues.

Keywords: addiction, sign trackers, goal trackers, attention, cue detection, perceptual sensitivity

Introduction

A long-standing question in addiction research concerns the psychobiological mechanisms which foster the manifestation of addiction-like behaviors in some individuals while others, despite repeated addictive drug use, do not succumb to addiction. The characterization of psychological vulnerability traits can serve as a guide toward identifying cognitive processes and underlying neuronal mechanisms associated with, or even causing, a propensity for drug taking and relapse (Egervari et al., 2018; George and Koob, 2010; Ersche et al., 2012; Ersche et al., 2011).

The majority of rodent models of psychological addiction vulnerability traits concern either a propensity for deficient inhibition and various forms of impulsivity, sensation- and novelty seeking (Cardinal et al., 2001; Dalley and Robbins, 2017; Hughson et al., 2019), or for the enhanced processing of, and behavioral control by, drug-associated or drug availability-predicting cues. Concerning the latter, sign-tracking rats (STs), which are selected from outbred populations using a Pavlovian Conditioned Approach (PCA) procedure, have been proposed to exhibit a tendency toward attributing incentive salience to Pavlovian reward or drug cues (Berridge and Robinson, 2016), rendering these cues to have relatively greater behavioral control than in goal-tracking rats (GTs). As a result, STs are more likely to approach and instrumentalize drug cues as well as to take drug and relapse in the presence of such cues (Yager and Robinson, 2013; Meyer et al., 2012; Saunders and Robinson, 2011, 2010; Flagel et al., 2009). Enhanced mesolimbic dopaminergic encoding of the incentive value of reward or drug cues has been demonstrated to mediate sign-tracking behavior and associated addiction vulnerability (Flagel and Robinson, 2017; Flagel et al., 2011; Saunders et al., 2013; Saunders and Robinson, 2012).

The selection of cues, documented by their incorporation into ongoing cognitive and behavioral activities and thus their capacity to control behavior, henceforth termed “cue detection” (Posner et al., 1980), can be the result of interactions between the properties of the cue, perceptual biases, and attentional styles. At the extremes, cue detection can be largely bottom-up, that is, controlled by the sensory qualities of the cue, or top-down and goal-directed, which could favor even relatively weak cues if the subject, based on past experiences and expectations, assigns predictive significance to these cues. The contributions of these two fundamental processes can be captured quantitatively by computing the signal detection theory-derived measures of perceptual sensitivity (d’) and bias (B”D), respectively (Kornbrot, 2006; Macmillan and Creelman, 1990; Green and Swets, 1974). The present experiment mainly investigated the contributions of the two processes to cue (or signal) detection by STs and GTs performing an operant Sustained Attention Task (SAT) which required the reporting of the presence of absence of a signal.

This experiment was motivated in part by prior results which suggested that GTs preferably deploy top-down, goal-directed processes toward the instrumental analysis of reward and drug cues, and even for the attentional control of complex movements. In contrast, STs appear to preferably employ bottom-up processes to respond to cues and exhibit little capacity for top-down control as indicated, for example, by their relatively poor capacity for maintaining high detection levels over prolonged periods of time (Paolone et al., 2013) and for monitoring complex stimulus conditions to optimize their movements (Pitchers et al., 2017b; Pitchers et al., 2017c; Kucinski et al., 2018). Relatively poor attentional control in STs (for a discussion of this construct see Sarter and Paolone, 2011) appears to be closely related to an attenuated capacity of their basal forebrain-cortical cholinergic projection system, due to attenuated mobilization of neuronal choline transporters (CHT) from intracellular domains to synaptosomal plasma membrane (Paolone et al., 2013; Koshy Cherian et al., 2017; Pitchers et al., 2017c). On the other hand, GTs require cholinergic signaling for deploying the top-down mechanisms that allows them, for example, to resist approaching Pavlovian drug cues, to effectively process high-order drug cues, or to plan complex movements (Pitchers et al., 2017b; Pitchers et al., 2017c; Kucinski et al., 2019). While the present results are limited to the demonstration that signal (or cue) detection in STs, but not GTs, is controlled, bottom-up, by the sensory quality of the cue, the available neurobiological evidence suggests the hypothesis that phenotype-specific cue detection processes are an essential component of the psychological trait indexed by sign- versus goal-tracking, and that they are mediated via the previously demonstrated variations in cholinergic signaling.

Methods

Animals.

A total of N=36 (15 females) Sprague Dawley rats (Envigo, Indianapolis, IN) were used. All animals underwent Pavlovian Conditioned Approach (PCA) screening and Sustained Attention Task (SAT) training. Rats weighed 230–260 g upon arrival and were individually housed in Plexiglas cages on a 12-hour light/dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 AM) in housing rooms with regulated temperature and humidity. Rats had ad libitum food (Laboratory Rodent Diet 5001, LabDiet) and water during a week-long acclimation period lasting until the start of SAT training. During daily SAT training and subsequent practice, access to water was controlled to water rewards earned during the task and an additional 15-minute period of free water access in the home cage following daily practice sessions. On days when animals were not tested, water access was increased to a minimum of 60 minutes. All procedures were approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were conducted in laboratories accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

PCA screening.

All animals underwent Pavlovian conditioned approach (PCA) screening to assess individual differences in cue-directed behavior to a reward-paired cue (lever) or to the location of the reward delivery (food cup). Based on this behavior, a PCA index was generated (below) and animals were classed as either goal-trackers (GTs), sign-trackers (STs), or intermediates (IMs). PCA procedures used were similar to those described previously (Paolone et al., 2013; Koshy Cherian et al., 2017; Pitchers et al., 2017b; Pitchers et al., 2017a; Kucinski et al., 2018).

Apparatus.

Animals were trained on PCA in operant chambers (Med Associates, Inc.) measuring 20.5 cm × 24.1 cm × 29.2 cm (length × width × height) that were contained within a sound-attenuating box. Each operant chamber was equipped with a food cup, a single retractable lever, and a red houselight. The red houselight was located on the opposite wall of the operant chamber from the other two box features. The food cup, attached to a pellet dispenser, was located 2.5 cm above the stainless-steel rod floor above a catch tray filled with corncob bedding. The pellet dispenser delivered one 45 mg banana-flavored sugar pellet (#F0059; Bio-Serv) when triggered. Records of each entrance into the food cup was recorded when a rat’s nose broke an infrared beam located about 1.5 cm from the base of the food cup. On one side of the food cup, counterbalanced between boxes, was an extendable lever approximately 6 cm from the floor, containing a white LED. The white LED illuminated the lever opening through which the lever extended. Most contacts with the lever were recorded as lever presses required an ~15 g force for detection. All program controls and data collection occurred with Med-PC software (version IV).

PCA procedures.

After a week of home cage acclimation, animals were handled and provided with ~15 banana-flavored sugar pellets in their home cage for two days prior to the start of training. On the first day of training, animals were familiarized with the delivery of the pellets to the food cup. During this program, after a five-minute habituation period in the chamber, the red houselight was illuminated, and 25 pellets were individually delivered to the food cup on a VI-30 schedule (0-60 s) over the course of an average of 12.5 minutes. If pellets remained in the food cup at the end of the session, animals were given additional days of food cup training until all pellets were consumed during a session. The next five consecutive days consisted of 25 lever-pellet reward pairings. In this program, after a one-minute habituation period, the red houselight was illuminated, and animals received 25 lever-pellet pairings (conditioned stimulus - unconditioned stimulus) on a VI-90 schedule (30-150 s). For each pairing, the lever was extended with the LED illuminated for 8 seconds. When the illuminated lever retracted and darkened, the pellet was delivered to the food cup. Each session lasted 37.5 minutes on average.

PCA measures and classification.

Animals were classified as GTs, STs, or intermediates using an index (PCA index) calculated as the average of three measures of approach: response bias, latency to approach, probability of approach. The response bias, the difference between the number of lever presses and the number of food cup entries, was calculated as a proportion of the total responses: (lever presses − food cup entries)/(lever presses + food cup entries). Latency scores, the amount of time before the animal either makes a contact with the lever or the food cup, were generated as the difference between the latency to approach the food cup and the latency to approach the lever upon CS presentation; the difference was normalized by dividing by the maximum latency of 8 seconds of lever extension: (magazine latency – lever latency)/8. The probability difference, the likelihood of pressing the lever or entering the food cup, was calculated as the difference between the probability of pressing the lever when the CS was present (the number of the trials with lever presses out of 25 total trials) minus the probability of food cup entry during the same time period. The average of these measures provides an index ranging from −1.0 to 1.0. A score of 0 indicates the food cup and lever were equally approached during the CS presentation throughout the trials. Scores of 1.0 indicate approaches and contacts with the lever on every trial while scores of −1.0 indicate approaches and contacts with the food cup on every trial. The PCA index values from days 4 and 5 of training were averaged to generate a score to classify rats into the three phenotypes. GTs were defined as animals with averaged PCA index scores of −0.5 to −1.0. STs have PCA index scores of 0.5 to 1.0, indicating that lever-directed behavior was about twice as frequent as food cup-directed behavior. Intermediates were classified as rats with PCA index scores of −0.5 to 0.5; intermediates were not used in these studies.

SAT training and practice.

Apparatus.

SAT training took place in 20 operant chambers (MED Associates) measuring 24 cm X 30 cm X 25 cm (length X width X height) each located within a sound-attenuating chamber. A grid floor (4 cm from the bottom of the chamber) of 0.5 cm stainless steel bars (1.5 cm between each bar) was positioned above a drop tray filled with corncob bedding. Located on the front panel of every operant chamber were two retractable levers, a water port and dispenser, and a central panel incandescent stimulus light (0.1 or 0.17 W). A houselight (0.1 or 0.17 W) was positioned on the opposite wall from the front panel 19 cm above the grid floor (Fig. 1a). The two retractable levers (7 cm above the grid floor) were situated on either side of the water port (3 cm above the grid floor) and the signal light (14 cm above the grid floor). The water dispenser provided 45 μL of water per water delivery. All inputs, outputs, and data collection were controlled by an Intel PC and Med-PC IV for Windows (version 4.1.3). Data was extracted for analysis with Med-PC2XL software.

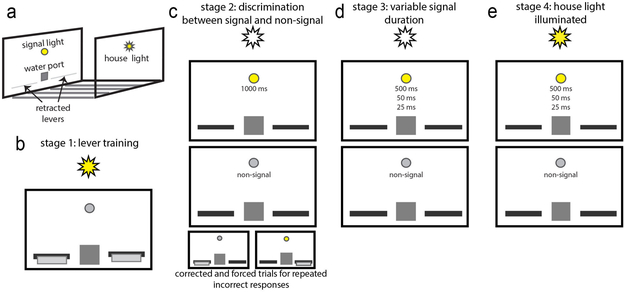

Figure 1.

The setup of the operant chamber can be seen in (a). In stage 1 (b), rats learn that lever presses to either lever, while the houselight on the opposite wall is illuminated, result in a water delivery to the water port. Once animals make a minimum of 80 presses to each lever within a given period of time, they are moved onto stage 2 (c) where the levers extend into the chamber following the presentation of a signal event (c, top) or a non-signal event (c, middle) and the houselight remains off. Presses to one lever now indicate reporting the presence of a signal and presses to the opposite lever report the absence of a signal. Trials are correct or forced (see Methods) for repeated incorrect responses (c, bottom). After reaching a criterion of 70% correct responses to signal and non-signal trials for three consecutive days, animals are trained on stage 3 (d). Signal events now consist of one of three shorter signal durations (d, top) and corrected and forced trials are removed. Once animals reach a consistent level of responding above 70% to the longest signal duration and to non-signal events, they are moved to stage 4 (e) where the houselight is illuminated throughout the entire session.

The initial SAT training consisted of 4 stages: 1) lever and water magazine training, 2) discrimination between signal and non-signal, 3) addition of variable signal durations, and 4) houselight illumination (see Fig. 1 b-e). Stage 1: Lever and water magazine training. For a week prior to task onset, animals were increasingly water restricted in their home cages, from 24 hrs to 1 hr of freely available water per day. Animals then began the initial stage of SAT training where presses to either of the two extended levers while the houselight was illuminated resulted in water delivery to the water port. More than six successive presses to either lever resulted in it becoming inactive until the other lever was pressed more than six times to prevent the development of a side bias. Rats moved onto the second stage of training when they earned 120 water rewards within 20 min or pressed each lever at least 80 times within the 40-min session. Stage 2: Discrimination between signal and non-signal. Stage 2 introduces the foundation of the task with the presentation of signal and non-signal events, extending and retracting levers for responding, and variable inter-trial intervals (ITIs). Following a five-minute adaptation period when all lights and levers remained off and retracted, animals complete approximately 160 trials with a variable ITI of 12±3 s and consisting of both signal and non-signal events. Successive presentation of events, variability of event types, and variable intervals have been thought to increase the demand on sustained attention (Davies and Parasuraman, 1982; Berardi et al., 2001; Helton et al., 2005; Parasuraman et al., 1987). Signal events consisted of a 1-s illumination of a signal light located above the water port. Two seconds after either event, the two levers extended into the chamber for six seconds or until a response was made. A failure to respond within the 6-s lever extended period was counted as an error of omission. Rats were trained to respond to one lever following signal events and to the opposite lever following non-signal events; lever contingencies were counterbalanced across rats. This yielded four response categories: hits and misses for signal events, and correct rejections and false alarms for non-signal events. If the rat made the correct response (hit or correct rejection) a water reward was delivered to the water port. Following an incorrect response (miss or false alarm), at this stage of SAT training the same trial type was repeated up to three times or until a correct response occurred. If the rat continued to make incorrect responses a forced trial was inserted during which only the correct lever extended into the chamber. The session lasted 40 min or 160 trials. Rats moved onto the third stage of training after a minimum of three consecutive days/sessions where hits and correct rejections were greater than 70%, omitted trials were less than 30%, and there were no more than two forced trials. Stage 3: Addition of variable signal durations. To limit the manifestation of a fixed signal discrimination threshold and to further tax signal detection performance, the maximum signal length was reduced to 500 ms and two shorter durations, 50 ms and 25 ms, were added (Parasuraman & Mouloua, 1987). Presentation of the three signal durations were pseudorandomized to occur at equal frequencies across the 81 signal trials per session. Lever extension time was shortened to 4 s. Additionally, correction and forced choice trials were terminated. Once animals maintained at least 70% hits to the 500 ms signal, 70% correct rejections, and less than 10% omissions for a minimum of three days, they moved on to the final version of SAT. Stage 4: Houselight illumination. The houselight on the wall opposite from the signal, levers, and water port (Fig. 1a) was illuminated throughout the final version of the SAT. Without the houselight, and as the signal light brightness is relatively salient in an otherwise dark operant chamber, rats were likely to detect signals even if oriented away from the intelligence panel. Turning on the houselight typically yields a robust yet transient decrease in response accuracy as rats now are required to constrain their behavior to monitor the intelligence panel in order to reliably detect signals. Therefore, houselight illumination is considered to be the critical step that significantly increases the demands on sustained attention. Generally, the recruitment of top-down attentional control mechanisms have been described to contribute to a subjects’ capacity to continue monitoring signal sources and execute cue state-dependent responses (Demeter and Woldorff, 2016; Thomson et al., 2015; Head and Helton, 2014; Esterman et al., 2013; MacLean et al., 2009). Furthering the demands on attentional processes, the event rate was increased by reducing the ITI to 9±3 s. Over the course of the 40-min task session, approximately 200 pseudorandomized signal and non-signal trials were presented. Non-signal and signal trials of all durations were presented such that there were roughly 18 non-signal trials and 18 signal trials (6 trials/duration) within an 8-min block (sessions were divided in 8-min blocks post hoc for the analysis of several aspects of performance).

Measures of SAT performance.

The following behavioral measures were recorded from each 40-minute SAT session: hits, misses, correct rejections, false alarms, and omissions. Hits and misses were recorded for every signal duration. The relative proportion of correct responses to either signal or non-signal trials were calculated as ratio of the total number correct of a trial type over 8 the sum of the number correct and number incorrect of the same trial type (hits/hits+misses; correct rejections/correct rejections+false alarms). Additionally, to assess overall sustained attentional capability, a combined measure of performance on signal and non-signal trials, the SAT score, was calculated using the relative number of hits (h) and false alarms (f) for each signal duration with the equation (h-f)/[2(h+f)-(h+f)2 (Frey and Colliver, 1973). Omissions, which do not influence this measure, were analyzed separately. The SAT score ranges from −1.0 to 1.0, with values closer to 1.0 indicating successful discrimination of signal and non-signal events, 0 reflecting an inability to distinguish between the two event types, and values close to −1.0 report a greater proportion of misses and false alarms. SAT performance is at chance levels when SAT scores are less than 0.17 (based on the assumed equal probability for the outcomes for both signal and non-signal trials, 59/100 successful responses yields a SAT score of 0.18 and a probability of just under p=0.05). To determine the impact of the transition from SAT Stage 3 to Stage 4 SAT practice, measures of performance were averaged across the 1) final three days of Stage 3 SAT training and 2) first three days of Stage 4 SAT training.

Measures derived from signal detection theory.

In addition to the SAT performance measures described above, analysis of perceptual sensitivity (d’) and bias (B”D) can provide further insight as to the specific challenges to bottom-up (d’) versus top-down (B”D) contribution to performance (Green and Swets, 1974; Kornbrot, 2006; Macmillan and Creelman, 1990; Demeter et al., 2008). Perceptual sensitivity measures the capability of an individual to detect a signal regardless of changes in motivation or reward structure and thus has been considered indicative of the extent of employed bottom-up attentional mechanisms. On the other hand, response bias measures the decision criteria (e.g., “risky” or “liberal” versus “conservative”) held by an individual towards the reporting of a signal and therefore has been viewed as reflecting the degree of top-down attentional regulation (Kornbrot, 2006; Donaldson, 1992; Dusoir, 1983). These measures were calculated using the proportion of hits (HP) and the proportion of false alarms (FAP). For each signal duration and combined across durations, d’ was calculated as d’=z(HP)–z(FAP) (Green and Swets, 1974). The effective maximum of d’, when proportion of hits is 0.99 and the proportion of false alarms is 0.01, is 4.65 indicating high perceptual sensitivity. d’ is 0 when the proportion of hits is equal to the proportion of false alarms. B”D was similarly calculated for and across signal durations using the formula: B”D = [(1- HP)(1- FAP)− HP* FAP]/[(1-HP)(1- FAP)+ HP* FAP] (Donaldson, 1992). Values of B”D range from −1.0 to 1.0 with values close to −1.0 indicating a liberal bias towards reporting the presentation of a signal, values near 0 indicating no bias, and values around 1.0 indicating a conservative bias (less likely to report a signal event).

Luminance measures.

Measures of luminance, in lux, were recorded using a 351 Power Meter (UDT Instruments). The overhead lights in the rooms containing the operant chambers were turned off to minimize background brightness when measures were taken. Luminance measures were taken for: background brightness of the chamber, houselight alone, cue light alone, and combined houselight and cue light. The variability in the brightness of the lights was a feature of the chambers and not experimentally manipulated. All four measures were taken when facing the front panel (towards the signal light) and again facing the back wall (towards the houselight). As measures of luminance toward the front panel were highly correlated with measures of luminance toward the back wall, only measures towards the back wall were used to analyze the impact of signal salience on performance. The photometer was placed 5.0 cm from the panel at the base of the wall to mimic the height of a rat when performing the SAT. The ratio between signal luminance and houselight luminance was calculated to estimate the relative salience of the signal. For example, a ratio of 5 indicate that a 5-fold higher luminance of the signal light relative to houselight luminance.

Statistical analyses.

Analysis of SAT performance relative to the strength of the houselight and signal light was carried out using mixed-model ANOVAs or one-way ANOVAs where appropriate (SPSS V24). The effect of sex was considered in all tests. Signal duration and task stage (with or without the houselight) were assessed as within-subject factors. In cases of violation of the sphericity assumption, Huyhn–Feldt-corrected F values, along with uncorrected degrees of freedom, are given. Alpha was set at 0.05. Analysis of the SAT score was the primary outcome measure. Secondary analyses concerned effects on hits and correct rejections to locate, post hoc, the main source(s) of effects on the SAT score. Therefore, the possibility of cumulative type I errors, arising from the analysis of multiple dependent measures (SAT score, hits, correct rejections), was not taken into account. In the event of significant main effects, post hoc multiple comparisons were used with Bonferroni corrections for repeated tests. Pearson’s r was calculated in the assessment of all relationships between signal and houselight luminance and measures of performance. As recommend previously (Greenwald et al., 1996; Sarter and Fritschy, 2008), exact P values were reported. Variances were reported and illustrated as the standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

PCA-based classification of STs and GTs

We previously reported that compared to GTs, SAT performance in STs is characterized by relatively unstable performance over time and that such vulnerable performance is associated with an attenuated capacity of the forebrain cholinergic system to support SAT performance (Paolone et al., 2013; Koshy Cherian et al., 2017; Pitchers et al., 2017c). Here, we employed the ST-GT phenotypes to further determine the psychological mechanisms mediating SAT performance, particularly SAT performance in response to task manipulations thought to tax attentional control (for a definition of this psychological construct see Sarter and Paolone, 2011). Using PCA index cutoffs of scores >0.5 for STs and scores <−0.5 for GTs, of the initial 48 rats (24 females) screened, 23 were STs (14 females), 17 were IMs (9 females), and 8 were GTs (1 female; Figure 2).

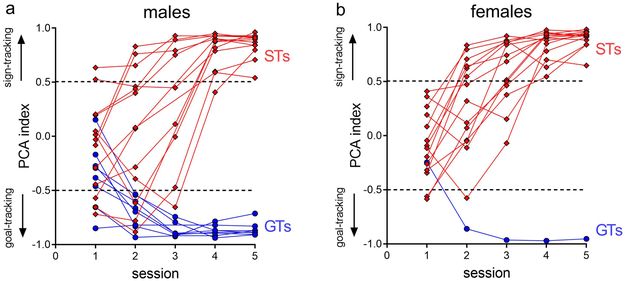

Figure 2.

Distribution of male (a) and female (b) STs and GTs based on PCA index from the 5 training sessions; data from intermediates is not shown. The final classification of STs and GTs was based on the average PCA index from session 4 and 5 using pre-determined cutoffs of −0.5 for GTs and 0.5 for STs (dashed lines). The distributions of STs and GTs were significantly different (P=0.018) with relatively more female STs and fewer female GTs relative to males.

There was a significant difference in the distribution of PCA indices between the sexes (X2(1, N=31)=5.56, P=0.018), with relatively more female STs (14/24 screened females versus 9/24 screened males) and fewer female GTs (1/24 screened females versus 7/24 screened males). An additional 4 male STs and 1 male GT, obtained from a prior screening, were included in the present experiments, resulting in a total of 27 STs (14 females) and 9 GTs (1 female).

Signal salience controls detection performance in STs but not GTs

Luminance measures.

Turning on the houselights (SAT training Stage 4; see Methods) constitutes a critical step in transforming the SAT from a conditional discrimination task to a sustained attention task (see Houselight illumination impaired performance below for references). As we observed that the relative brightness of signal and houselights varied considerably across our operant chambers, we employed this information to investigate the psychological processes which may contribute to the performance of STs and GTs, specifically to the transient decreases in performance when rats transitioned from SAT Stage 3 (no houselights) to Stage 4 (houselights on). Prior to turning on the houselights, rats were able to correctly respond to signals even if they were oriented towards the back wall during signal presentation. In contrast, following turning on of the houselights (Stage 4), the overall reduction of the relative salience of the signal light required that rats oriented toward the intelligence panel to accurately report the signal status. Thus, we measured the relative luminance of the signal light and houselight facing the back panel (see Methods) and investigated the impact of relative signal brightness on the performance following the transition to Stage 4 of the SAT.

The signal light luminance ranged from 1.02 lux to 2.23 lux (M, SEM: 1.65±0.08 lux). Houselights averaged lower luminance than signal lights but the range of houselight brightness varied considerably (range: 0.08-0.87 lux; 0.46±0.05 lux; Fig. 3a). The proportion of the total luminance (signal light plus houselight) contributed by the signal light ranged from nearly equal proportions to double the luminance of the houselight (range: 62.67-90.47%; M, SEM: 79.48±1.68 %). For subsequent analysis, the relative brightness of the signal light (signal light/houselight) was computed; values ranged from 1.63-7.26; M, SEM: 4.11±0.38; Fig. 3b).

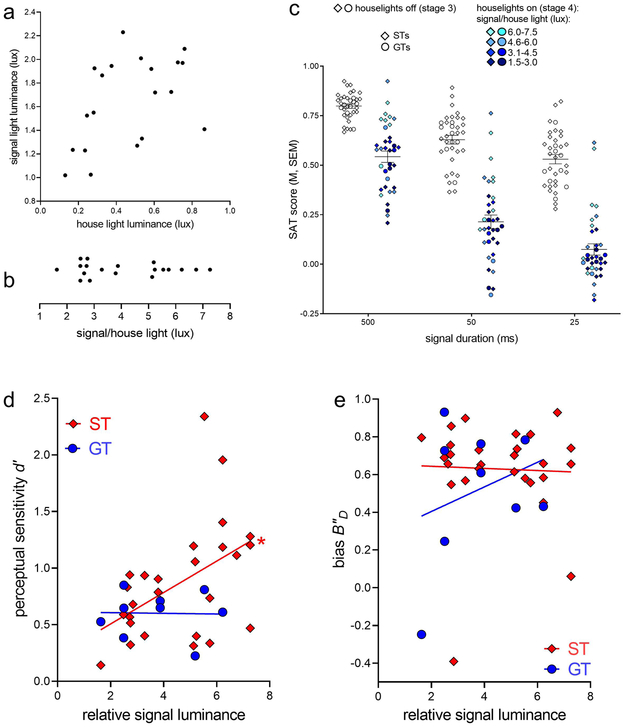

Figure 3.

Distribution of luminance (in lux) of signal lights and houselights (a). Each dot represents a unique operant chamber. The relative signal luminance (b) was calculated as the ratio of the signal light luminance over the houselight luminance of each SAT operant chamber. As expected, illumination of the houselight in stage 4 (colored shapes; c) significantly reduced overall SAT performance as compared to stage 3 (open shapes; c) across all signal durations in both STs (diamonds) and GTs (circles; all post hoc comparisons: P<0.0001). Darker circles represent operant chambers with relatively weaker cue lights while lighter colored circles represent cue lights that were relatively stronger than the houselight. The performance of STs and GTs did not differ significantly across the three durations. Employing signal detection analysis revealed that signal salience controls signal detection in STs but not GTs (d). Specifically, the perceptual sensitivity of STs was positively correlated with the relative signal luminance of their respective operant chamber (STs: r=0.48, P=0.01; GTs: r=−0.02, P=0.95). This relationship would be maintained if the data from the two most extreme STs, with the highest perceptual sensitivity measures, were removed (r=0.49, P=0.01). Measures of response bias (e), thought to reflect one potential top-down mechanism of signal detection, did not correlate with the relative brightness of the signal in either phenotype (both r<0.29, both P>0.44).

Performance prior to houselight illumination.

To determine the role of signal light salience on Stage 3 SAT performance, signal light luminance values were grouped into 4 brackets (1.00-1.31 lux, 1.31-1.62 lux, 1.62-1.93 lux, 1.93-2.25 lux). An omnibus ANOVA on the effects of signal luminance, signal duration (500, 50 25 ms), sex and phenotype (ST/GT) on the SAT score indicated a main effect of duration (F(2,52)=121.32, P<0.0001), reflecting significant differences between all three SAT scores calculated over hits to the 3 signal durations (all t>7,46, all P<0.0001), but no effects of sex or phenotype and no 2- or 3-way interactions (all F<2.13, all P>0.15; open circles in Fig. 3c). The secondary analysis of hit rates mirrored the analysis of SAT scores, reflecting that the rats’ correct rejection rate was not affected, as expected, by signal brightness, and neither by sex or phenotype (main effects and interactions: all F<3.05, all P>0.09). Thus, at this stage of SAT training, signal duration, but not relative signal brightness, influenced the animals’ hit rate, and STs and GTs performed comparably.

Houselight illumination impaired performance.

The illumination of houselights in Stage 4 of SAT training required that rats monitored the intelligence panel for successful signal detection because the signal luminance became relatively obscured by the houselight. Compared to Stage 3, which constitutes primarily a conditional visual discrimination task with limited demands on sustained attention, Stage 4 elevates this task to a sustained attention task. Consistent with this view, conditional discrimination performance does not elicit trial-based cholinergic neuronal activity in the basal forebrain (Hangya et al., 2015) and does not increase cortical ACh release (Himmelheber et al., 1997), while SAT performance increases cortical ACh release (St Peters et al., 2011), specifically in response to signals that yield hits (Howe et al., 2013; Howe et al., 2017; Gritton et al., 2016).

An ANOVA on the effects of task stage (Stage 3 versus Stage 4), signal duration, sex, and phenotype on SAT scores captured the large performance decline produced by houselight illumination (main effect of stage: F(1,32)=143.53, P<0.0001; Stage 3 (M, SEM): 0.65±0.02; Stage 4: 0.28±0.03; Cohens d: 2.47). The effects of Stage interacted with signal duration (main effect of duration and interaction: both F>19.00, both P<0.0001). Inspection of Fig. 3c suggested that the Stage 4-associated impairments were larger for SAT scores calculated over hits to 50 and 25-ms signals when compared with hits to longest signals; however, all multiple comparisons, within Stage and across signal durations, and within signal duration and across stages, were highly significant (all t(35)>7.45, all P<0.0001). There were no main effects of sex and phenotype (both F<3.08, both P>0.09).

This omnibus ANOVA also indicated interactions with phenotype (phenotype × signal duration: (F(2,64)=3.43, P=0.04; stage × signal duration × phenotype: F(2,64)=3.90, P=0.03). However, these interactions were either not located by post hoc multiple comparisons (2-way: all comparisons across durations and within phenotype: all P<0.002; pairwise comparisons for each duration: all P>0.20), or appeared to reflect a phenotype-based difference in the SAT scores to middle-duration signals only, and in Stage 4 but not Stage 3 (3-way; Stage 4: STs: 0.26±0.04; GTs: 0.09±0.04; t(34)=0.14, P=0.04). Together, these results did not indicate systematic, robust and interpretable differences in the impact of houselight illumination on the SAT scores of STs versus GTs.

Once again, the analysis of hit rates closely mirrored that of SAT scores, with the exception that the phenotype × duration interaction was not observed in the analysis of hits. Correct rejections were also reduced by the transition from Stage 3 to 4 (main effect: F(1,32)=12.89, P=0.001; Stage 3: 87.37±1.03%; Stage 4: 79.62±1.62%; Cohens d: 1.03), and they were mildly yet significantly lower in GTs (main effect of phenotype: F(1,32)=5.41, P=0.03; STs: 84.42±1.28%; GTs: 80.69±2.51%; no significant effect of sex and no significant interactions; all F<2.93, all P>0.10). Error of omissions remained generally below 5% of all trials and were unaffected by Stage, sex, or phenotype (all F<1.98, all P>0.17).

A separate analysis addressed the potential impact of relative signal brightness (signal luminance/houselight luminance) on the initial Stage 4 performance. For this analysis, luminance ratios were bracketed as indicated in Fig. 3c. Neither SAT scores nor hits and correct rejections were affected by the relative brightness of the signal, and there were no significant interactions with phenotype or sex (all F<0.89, all P>0.42).

Perceptual sensitivity and bias.

Overall, the results described above indicate that houselight illumination impaired the rats’ performance largely regardless of phenotype and to the relative brightness of the signal light. The analysis of signal detection theory-derived parameters, perceptual sensitivity and bias, was designed to determine whether the performance in response to houselight illumination was supported by similar psychological processes.

During Stage 3 - with the houselights still off - perceptual sensitivity (d’) scores were relatively high in both phenotypes (STs: 1.92±0.09; GTs: 1.83±0.1) and did not correlate with cue light brightness (both r<0.25, both P>0.51). This was an expected finding because of the relatively high salience of the cue light fostered – bottom up – detection performance. However, following the transition to Stage 4, with houselights now illuminated, perceptual sensitivity scores decreased in all rats (main effect of stage: F(1,34)=260.33, P<0.001; d’; Stage 3: 1.90±0.07; Stage 4: 0.80±0.08). At the same time, this challenge rendered the animals’ bias to become significantly more conservative; that is, they exhibited a relative greater propensity to report the absence of the signal (F(1,34)=17.15, P<0.0001; B’D; Stage 3: 0.35±0.04; Stage 4: 0.60±0.05).

Most importantly, in STs, but not GTs, Stage 4 perceptual sensitivity was significantly correlated with relative signal luminance (STs: r=0.48, P=0.01; GTs: r=−0.02, P=0.95; Fig. 3d; note that the significant correlation in STs would be preserved if the two highest d’ values were considered outliers and removed: r=0.49, P=0.01). In other words, greater relative signal salience predicted higher detection rates in STs but not GTs. Inspection of the linear regression observed in STs indicated that a doubling of the relative brightness of the signal light nearly doubled perceptual sensitivity. The relative brightness of signals was not correlated with bias in either phenotype (both r<0.29, both P>0.44; Fig. 3e). Thus, even though both phenotypes’ levels of performance following houselight illumination did not robustly differ, in Stage 4, the psychological mechanisms via which performance was maintained differed significantly between STs and GTs.

As the transition to Stage 4 – the final version of the SAT – is thought to tax attentional control, we determined whether perpetual sensitivity in STs continued to be influenced by relative signal brightness, as rats extensively practiced the SAT, or whether this finding was restricted to the initial 3 days following the transition to Stage 4. We therefore determined correlations with relative signal luminance for the last 3 sessions in the SAT, after rats practiced the SAT for 27.00±1.63 sessions. The impact of relative signal brightness on perceptual sensitivity remained stable in STs, and indeed became stronger (r=0.58, P=0.001; GTs: r=0.31, P=0.41; bias: both r<0.04, both P>0.91).

Discussion

Acquiring a Sustained Attention Task (SAT), performance levels of STs and GTs did not differ during the various training stages, including the transition of the task from a mere visual conditional discrimination task (Stage 3) to a task requiring attentional control (Stage 4). Moreover, in Stage 4, signal duration similarly influenced detection rates in STs and GTs, and relative signal luminance did not significantly impact levels of performance. However, addressing the psychological mechanisms mediating the rats’ performance in Stage 4, we found that perceptual sensitivity (d’), a measure derived from signal detection theory and typically considered a function of the sensory quality of the signal, was influenced by relative signal brightness in STs but not GTs. In STs, perceptual sensitivity continued to depend on relative signal luminance as animals extensively practiced the task and reached asymptotic performance. The discussion below focuses on the decisional mechanisms that allowed GTs to minimize the role of relative signal brightness for detection performance, and on the impact of the current results for specifying the role of cortical cholinergic signaling in STs and GTs.

In STs, perceptual sensitivity varied with relative signal luminance. However, GTs did not rely on this type of bottom-up or signal-driven information to report the presence or absence of a cue. The data from the present experiment do not provide direct insight into the decisional processes which allowed GTs to report the presence or absence of the signal but results from prior studies begin to provide a theoretical framework for describing the cognitive style that is inherent to the trait indexed by goal-tracking. Specifically, we previously demonstrated that GTs are superior to STs in incorporating higher-order contextual information, as indicated by the greater power of a discriminative cue, or “occasion setter”, to reinstate cocaine seeking behavior (Pitchers et al., 2017b). Moreover, in situations requiring the attentional supervision of complex movements, assessed by traversal of complex, rotating rods, GTs were found to time, that is, to plan, their entry to difficult components of these rods so that they avoided more “difficult” traversal conditions (Kucinski et al., 2018). Together, these findings are consistent with the hypothesis that top-down, or goal-directed decisions predominate the behavior of GTs, while STs preferably respond bottom-up or cue-driven to salient cues.

Indeed, the phenotype-defining sign- versus goal-tracking behaviors can be conceptualized using this perspective. The approach behavior demonstrated by STs is largely controlled by the salience of the cue, including its incentive salience, while the goal-directed analysis of the Pavlovian cue allows GTs to resist approaching the cue and instead focus on the reward delivery site (Pitchers et al., 2018; Pitchers et al., 2017c). Thus, in the present experiment, GTs may be speculated to have been able to render a decision about the presence or absence of a cue without integrating information about a secondary sensory quality of the signal, i.e., relative luminance. Attempts to experimentally determine, in rodents, the potentially higher order decisional processes used by GTs to disregard relative signal luminance, including manipulations that may reveal differential shifts in bias in the two phenotypes, will be difficult and, in future, may preferably be conducted in humans classified as STs and GTs (Joyner et al., 2018; Versace et al., 2016).

The present data indicate that relative signal luminance influenced perceptual sensitivity levels in STs but not GTs. One might also have expected that, in task Stage 4, signal duration was correlated with d’ in STs. However, because perceptual sensitivity scores calculated over hits to 50 and 25 ms signals were generally relatively low and compressed toward zero, and scores calculated over 500 ms signals were generally high and compressed toward one, differential relationships between perceptual sensitivity scores of STs and GTs and signal duration were not apparent. In contrast to the relatively extreme effects of signal duration on signal salience, the more moderate range of signal salience variations based on relative signal luminance afforded the demonstration of a phenotype-specific role of perceptual sensitivity.

STs were previously reported to perform the SAT at a significantly lower level than GTs (Paolone et al., 2013). Inspection of the present and prior data indicated that the absence of such a difference in the present data set reflected a relatively lower performance of GTs in the present experiment. Compared with the current SAT scores from GTs, prior scores from STs do not differ significantly (main effect of phenotype and interaction between the effects of phenotype and signal duration: both F<1.15, both P>0.33). The conclusion that STs and GTs perform the SAT by utilizing opponent psychological mechanisms is assisted by the absence of a significant difference in hit rates.

The opponent cognitive styles of STs and GTs are mediated via the differential responsivity of their forebrain-cortical cholinergic systems (Sarter and Phillips, 2018). Cholinergic activity in STs exhibit attenuated increases during SAT performance relative to GTs (Paolone et al., 2013). Similarly, the ability of GTs to resist approaching a Pavlovian drug cue is associated with elevated levels of prefrontal cholinergic activity, while STs do not show such increases in cholinergic activity and approach the cue (Pitchers et al., 2017c). Furthermore, the ability of GTs to processes higher-order cues and to plan complex traversals requires cholinergic signaling (Pitchers et al., 2017b; Kucinski et al., 2019). Attenuated cholinergic signaling in STs was found to be due to a failure of the neuronal choline transporter (CHT) to populate the synaptosomal plasma membrane to support elevations in cholinergic neurotransmission (Koshy Cherian et al., 2017). The present results further suggest that the relative lack of cholinergic activation in STs mediates a greater reliance on bottom-up, or signal-driven detection processes, while cholinergic activation in GTs supports detection performance regardless of secondary sensory qualities of the signal. It is of interest to note that this finding parallels results from humans expressing a low-capacity version of the CHT (“I89V subjects”). Like STs, basic detection performance of I89V humans does not significantly differ from humans expressing the wild type CHT. However, when taxed with content-rich distractors, I89V humans exhibit a relative deficient deployment of top-down attentional control mechanisms and thus robustly greater decreases in performance (Berry et al., 2015; Berry et al., 2014; Sarter et al., 2016). It would be of considerable interest to explore the relative impact of signal salience on perceptual sensitivity in I89V and wild type humans, and to determine whether sign-tracking behavior is over-represented in I89V humans.

Taken together, the present findings indicate that STs detect cues preferably by using bottom-up, or cue-driven mechanisms. In contrast, detection performance by GTs was less dependent on the sensory quality of cues, consistent with prior evidence suggesting that GTs tend to preferably deploy higher-order, or goal-driven mechanisms to decide upon the presence versus absence of signals. These cognitive styles of STs and GTs contribute to their differential, cue type-dependent vulnerability for addiction-like behavior (Pitchers et al., 2017b) and thus need to be further investigated.

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported by PHS grant R01DA045063.

Footnotes

Competing Financial Interests: The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Berardi A, Parasuraman R, Haxby JV (2001) Overall vigilance and sustained attention decrements in healthy aging. Experimental Aging Research 27:19–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC, Robinson TE (2016) Liking, wanting, and the incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Am Psychol 71:670–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry AS, Blakely RD, Sarter M, Lustig C (2015) Cholinergic capacity mediates prefrontal engagement during challenges to attention: evidence from imaging genetics. Neuroimage 108:386–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry AS, Demeter E, Sabhapathy S, English BA, Blakely RD, Sarter M, Lustig C (2014) Disposed to distraction: genetic variation in the cholinergic system influences distractibility but not time-on-task effects. J Cogn Neurosci 26:1981–1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinal RN, Pennicott DR, Sugathapala CL, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ (2001) Impulsive choice induced in rats by lesions of the nucleus accumbens core. Science 292:2499–2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, Robbins TW (2017) Fractionating impulsivity: neuropsychiatric implications. Nat Rev Neurosci 18:158–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies DR, Parasuraman R (1982) The psychology of vigilance. London; New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Demeter E, Woldorff MG (2016) Transient distraction and attentional control during a sustained selective attention task. J Cogn Neurosci 28:935–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demeter E, Sarter M, Lustig C (2008) Rats and humans paying attention: cross-species task development for translational research. Neuropsychology 22:787–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson W (1992) Measuring recognition memory. J Exp Psychol Gen 121:275–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusoir T (1983) Isobias Curves in Some Detection Tasks. Perception & Psychophysics 33:403–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egervari G, Ciccocioppo R, Jentsch JD, Hurd YL (2018) Shaping vulnerability to addiction - the contribution of behavior, neural circuits and molecular mechanisms. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 85:117–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ersche KD, Barnes A, Jones PS, Morein-Zamir S, Robbins TW, Bullmore ET (2011) Abnormal structure of frontostriatal brain systems is associated with aspects of impulsivity and compulsivity in cocaine dependence. Brain 134:2013–2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ersche KD, Jones PS, Williams GB, Turton AJ, Robbins TW, Bullmore ET (2012) Abnormal brain structure implicated in stimulant drug addiction. Science 335:601–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esterman M, Noonan SK, Rosenberg M, Degutis J (2013) In the zone or zoning out? Tracking behavioral and neural fluctuations during sustained attention. Cereb Cortex 23:2712–2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagel SB, Robinson TE (2017) Neurobiological basis of individual variation in stimulus-reward learning. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 13:178–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagel SB, Akil H, Robinson TE (2009) Individual differences in the attribution of incentive salience to reward-related cues: Implications for addiction. Neuropharmacology 56 Suppl 1:139–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagel SB, Clark JJ, Robinson TE, Mayo L, Czuj A, Willuhn I, Akers CA, Clinton SM, Phillips PE, Akil H (2011) A selective role for dopamine in stimulus-reward learning. Nature 469:53–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey PW, Colliver JA (1973) Sensitivity and responsivity measures for discrimination learning. Learning and Motivation 4:327–342. [Google Scholar]

- George O, Koob GF (2010) Individual differences in prefrontal cortex function and the transition from drug use to drug dependence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 35:232–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DM, Swets JA (1974) Signal detection theory and psychophysics. Huntington, N.Y.,: R. E. Krieger Pub. Co. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, Gonzalez R, Harris RJ, Guthrie D (1996) Effect sizes and p values: What should be reported and what should be replicated? Psychophysiology 33:175–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritton HJ, Howe WM, Mallory CS, Hetrick VL, Berke JD, Sarter M (2016) Cortical cholinergic signaling controls the detection of cues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:E1089–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hangya B, Ranade SP, Lorenc M, Kepecs A (2015) Central cholinergic neurons are rapidly recruited by reinforcement feedback. Cell 162:1155–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head J, Helton WS (2014) Sustained attention failures are primarily due to sustained cognitive load not task monotony. Acta Psychol (Amst) 153:87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helton WS, Hollander TD, Warm JS, Matthews G, Dember WN, Wallaart M, Beauchamp G, Parasuraman R, Hancock PA (2005) Signal regularity and the mindlessness model of vigilance. Br J Psychol 96:249–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmelheber AM, Sarter M, Bruno JP (1997) Operant performance and cortical acetylcholine release: role of response rate, reward density, and non-contingent stimuli. Cogn Brain Res 6:23–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe WM, Gritton HJ, Lusk NA, Roberts EA, Hetrick VL, Berke JD, Sarter M (2017) Acetylcholine release in prefrontal cortex promotes gamma oscillations and theta-gamma coupling during cue detection. J Neurosci 37:3215–3230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe WM, Berry AS, Francois J, Gilmour G, Carp JM, Tricklebank M, Lustig C, Sarter M (2013) Prefrontal cholinergic mechanisms instigating shifts from monitoring for cues to cue-guided performance: converging electrochemical and fMRI evidence from rats and humans. J Neurosci 33:8742–8752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughson AR, Horvath AP, Holl K, Palmer AA, Solberg Woods LC, Robinson TE, Flagel SB (2019) Incentive salience attribution, "sensation-seeking" and "novelty-seeking" are independent traits in a large sample of male and female heterogeneous stock rats. Sci Rep 9:2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyner MA, Gearhardt AN, Flagel SB (2018) A Translational Model to Assess Sign-Tracking and Goal-Tracking Behavior in Children. Neuropsychopharmacology 43:228–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornbrot DE (2006) Signal detection theory, the approach of choice: model-based and distribution-free measures and evaluation. Percept Psychophys 68:393–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshy Cherian A, Kucinski A, Pitchers KK, Yegla B, Parikh V, Kim Y, Valuskova P, Gurnarni S, Lindsley CW, Blakely RD, Sarter M (2017) Unresponsive choline transporter as a trait neuromarker and a causal mediator of bottom-up attentional biases. J Neurosci 37:2947–2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucinski A, Lustig C, Sarter M (2018) Addiction vulnerability trait impacts complex movement control: Evidence from sign-trackers. Behav Brain Res 350:139–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucinski A, Kim Y, Sarter M (2019) Basal forebrain chemogenetic inhibition disrupts the superior complex movement control of goal-tracking rats. Behav Neurosci 133:121–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean KA, Aichele SR, Bridwell DA, Mangun GR, Wojciulik E, Saron CD (2009) Interactions between endogenous and exogenous attention during vigilance. Atten Percept Psychophys 71:1042–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan NA, Creelman CD (1990) Response Bias - Characteristics of Detection Theory, Threshold Theory, and Nonparametric Indexes. Psychological Bulletin 107:401–413. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer PJ, Lovic V, Saunders BT, Yager LM, Flagel SB, Morrow JD, Robinson TE (2012) Quantifying individual variation in the propensity to attribute incentive salience to reward cues. PLoS One 7:e38987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolone G, Angelakos CC, Meyer PJ, Robinson TE, Sarter M (2013) Cholinergic control over attention in rats prone to attribute incentive salience to reward cues. J Neurosci 33:8321–8335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman R, Warm JS, Dember WN (1987) Vigilance: taxonomy and utility In: Ergonomics and human factors. Recent research in psychology (Mark JS, Warm JS, Huston JL, eds), pp 11–32. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Pitchers KK, Sarter M, Robinson TE (2018) The hot 'n' cold of cue-induced drug relapse. Learn Mem 25:474–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitchers KK, Wood TR, Skrzynski CJ, Robinson TE, Sarter M (2017a) The ability for cocaine and cocaine-associated cues to compete for attention. Behav Brain Res 320:302–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitchers KK, Phillips KB, Jones JL, Robinson TE, Sarter M (2017b) Diverse Roads to Relapse: A Discriminative Cue Signaling Cocaine Availability Is More Effective in Renewing Cocaine Seeking in Goal Trackers Than Sign Trackers and Depends on Basal Forebrain Cholinergic Activity. Journal of Neuroscience 37:7198–7208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitchers KK, Kane LF, Kim Y, Robinson TE, Sarter M (2017c) 'Hot' vs. 'cold' behavioural-cognitive styles: motivational-dopaminergic vs. cognitive-cholinergic processing of a Pavlovian cocaine cue in sign- and goal-tracking rats. Eur J Neurosci 46:2768–2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI, Snyder CR, Davidson BJ (1980) Attention and the detection of signals. J Exp Psychol 109:160–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarter M, Fritschy JM (2008) Reporting statistical methods and statistical results in EJN. Eur J Neurosci 28:2363–2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarter M, Paolone G (2011) Deficits in attentional control: cholinergic mechanisms and circuitry-based treatment approaches. Behav Neurosci 125:825–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarter M, Phillips KB (2018) The neuroscience of cognitive-motivational styles: Sign- and goal-trackers as animal models. Behav Neurosci 132:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarter M, Lustig C, Blakely RD, Koshy Cherian A (2016) Cholinergic genetics of visual attention: Human and mouse choline transporter capacity variants influence distractibility. J Physiol Paris 110:10–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders BT, Robinson TE (2010) A cocaine cue acts as an incentive stimulus in some but not others: implications for addiction. Biol Psychiatry 67:730–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders BT, Robinson TE (2011) Individual variation in the motivational properties of cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology 36:1668–1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders BT, Robinson TE (2012) The role of dopamine in the accumbens core in the expression of Pavlovian-conditioned responses. Eur J Neurosci 36:2521–2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders BT, Yager LM, Robinson TE (2013) Cue-evoked cocaine "craving": role of dopamine in the accumbens core. J Neurosci 33:13989–14000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Peters M, Demeter E, Lustig C, Bruno JP, Sarter M (2011) Enhanced control of attention by stimulating mesolimbic-corticopetal cholinergic circuitry. J Neurosci 31:9760–9771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson DR, Besner D, Smilek D (2015) A resource-control account of sustained attention: evidence from mind-wandering and vigilance paradigms. Perspect Psychol Sci 10:82–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versace F, Kypriotakis G, Basen-Engquist K, Schembre SM (2016) Heterogeneity in brain reactivity to pleasant and food cues: evidence of sign-tracking in humans. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 11:604–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yager LM, Robinson TE (2013) A classically conditioned cocaine cue acquires greater control over motivated behavior in rats prone to attribute incentive salience to a food cue. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 226:217–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]