Abstract

We previously reported a ligand-independent and rhodopsin-dependent insulin receptor (IR) neuroprotective signaling pathway in both rod and cone photoreceptor cells, which is activated through protein-protein interaction. Our previous studies were performed with either retina or isolated rod or cone outer segment preparations and examined the expression of IR signaling proteins. The isolation of outer segments with large portions of the attached inner segments is a technical challenge. Optiprep™ density gradient medium has been used to isolate cell and subcellular organelles, Optiprep™ is a non-ionic iodixanol-based medium with a density of 1.320 g/mL. We employed this method to examine the expression of IR and its signaling proteins, and activation of one of the downstream effectors of the IR in isolated photoreceptor cells. Identification of the signaling complexes will be helpful for therapeutic targeting in disease conditions.

Keywords: Insulin receptor, Protein-protein interaction, Rhodopsin activation, Photoreceptor cells, Retina, light activation, neuron survival

1. Introduction

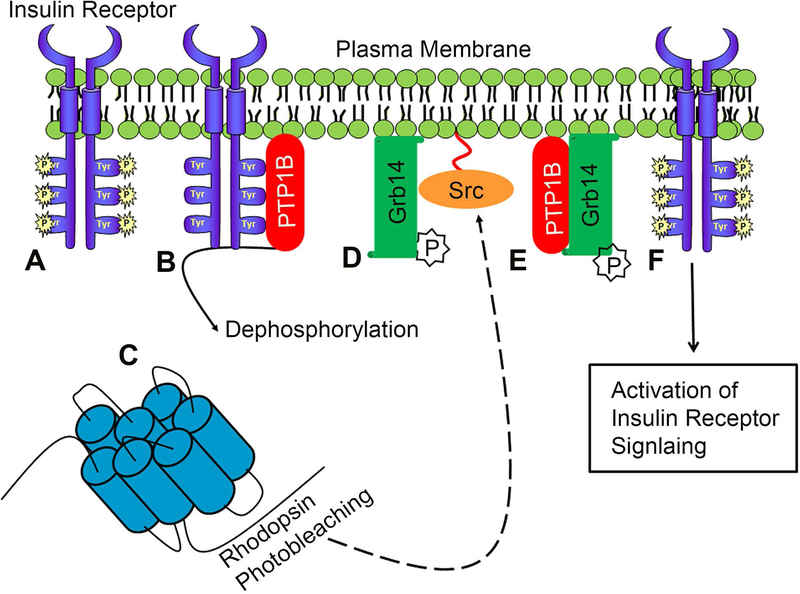

Photoreceptor cells are polarized neurons present in the retina. These cells play an important role in absorbing photons from light and translating it into signals that activate biological events. These cells are highly metabolic, and their energy demands are equivalent to those of a proliferating tumor cell (Rajala and Gardner, 2016, Warburg, 1956a, b). Activating tyrosine kinase signaling (Brown, 2011, Li et al. , 1996, Vlahovic and Crawford, 2003) and inhibiting protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B (PTP1B) promote tumor growth (Hardy and Tremblay, 2008), whereas blocking the oncogenic tyrosine kinase and activating PTP1B promote photoreceptor degeneration (Rajala et al. , 2016). We previously identified a novel light-activatable insulin receptor (IR) survival pathway in both rod and cone photoreceptor cells (Basavarajappa et al. , 2011, Rajala et al. , 2007, Rajala et al., 2016, Rajala and Anderson, 2010, Rajala et al. , 2002). IR activation is essential for both rod and cone photoreceptor survival, as conditional deletion of the IR in rods resulted in stress-induced photoreceptor degeneration (Rajala et al. , 2008), whereas ablation of the IR in cones resulted in cone degeneration without added stress (Rajala et al., 2016). The IR pathway that we described in rods and cones does not require insulin but is rod and cone-opsin dependent (Rajala et al., 2007, Rajala et al., 2016). However, the addition of insulin to ex vivo retinas (Rajala et al. , 2004, Reiter et al. , 2003) or sub-conjunctival administration of insulin activates IR and its downstream signaling in the retina (Fort et al. , 2011). We (Rajala et al., 2016) and others (Punzo et al. , 2009) have shown that systemic administration of insulin promotes cone survival in retinal degenerative mouse models. The retinal IR is encoded by a single gene, and is alternatively spliced in different tissues and produced as type A or type B receptor (Gosbell et al. , 2000, Seino and Bell, 1989, Ullrich et al. , 1985). Further, the retinal IR is a type-A receptor with a missing exon 11 in the extracellular domain, whereas this exon 11 is included in the liver IR, which is a type-B receptor (Rajala et al. , 2009c, Reiter et al., 2003). Due to splicing that skips exon 11, the retinal IR exhibits high basal tyrosine kinase activity (constitutive activation) in the absence of ligand, whereas activation of the liver IR is exclusively insulin-dependent (Rajala et al., 2009c, Reiter et al., 2003). Even though IR is constitutively active in the retina, our earlier studies suggest that IR activation is enhanced under light-adapted conditions (Rajala et al., 2002). Under dark-adapted conditions, protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) binds to the IR (Fig.1), dephosphorylates the tyrosine on the IR, and inactivates IR signaling (Rajala et al. , 2010). Upon light-activation, an adapter protein, growth factor receptor-bound protein 14 (Grb14), moves to outer segments from inner segments (Rajala et al. , 2009a) and undergoes tyrosine phosphorylation by a rhodopsin-dependent non-receptor tyrosine kinase, Src (Fig.1) (Basavarajappa et al., 2011, Rajala et al., 2016, Rajala et al. , 2013b). The phosphorylated-Grb14 binds to PTP1B and inactivates it, thereby promoting the IR signaling pathway in photoreceptor cells (Fig.1). Our previous studies were performed with either retina or isolated rod or cone outer segment preparations and examined the expression of IR signaling proteins (Rajala et al., 2007, Rajala et al. , 2013a). The isolation of outer segments with large portions of the attached inner segments is a technical challenge. A method to isolate outer segments with attached inner segments has recently been reported (Gilliam et al. , 2012). We employed this method to examine the expression of IR and its signaling proteins, and activation of one of the downstream effectors of the IR in isolated photoreceptor cells. This information is vital to understanding the location of signaling complexes, and may help to target the pathway(s) in disease conditions.

Figure 1. Rhodopsin-dependent IR signaling pathway in photoreceptor cells.

The insulin receptor (IR) in the retina is constitutively phosphorylated (A). Under dark-adapted conditions, PTP1B binds to the IR, dephosphorylates the tyrosine on the IR, and inactivates IR signaling (B). Upon light-activation, an adapter protein, Grb14 undergoes tyrosine phosphorylation by a rhodopsin-dependent (D) non-receptor tyrosine kinase, Src. The phosphorylated-Grb14 binds to PTP1B and inactivates it (E), thereby promoting the IR signaling pathway in photoreceptor cells (F).

2. Materials and methods

Animals

2.1. Ethical statement for animal experimentation

All animals were treated in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The protocols were approved by the IACUC at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. All efforts were made to reduce the pain and number of animals.

2.2. Animals

Animals were born and raised in our vivarium and kept under dim cyclic light (40–60 lux, 12 h light/dark cycle). The Nrl−/− mice were kindly provided by Dr. Anand Swaroop (NIH, Bethesda, MD). The Nrl−/− mice were originally established on the C57Bl/6 background (Mears et al. , 2001) and we bred them onto a Balb/c background. The Rpe65−/− mice were a kind gift from Dr. Jing-Xing Ma (University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City). For light/dark experiments, mice were dark-adapted overnight. The next morning, half of the mice were exposed to normal room light (300 lux equivalent to 3000 R*/rods/sec) for 30 min (Rajala et al., 2002). The retinas were harvested after CO2 asphyxiation and were subjected to biochemistry.

2.3. Antibodies

Polyclonal pAkt (S473), polyclonal IGF-1R, Shp2, Akt, Src, and monoclonal IR antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). Polyclonal PTP1B antibody was purchased from Epitomics (Burlingame, CA). Polyclonal cSrc antibody was purchased from proteintech, Inc (Rosemont, IL). Polyclonal Grb14 antibody was generated by us, and the details are provided in our previous publication.23 Rabbit polyclonal anti-red/green cone opsin (M-opsin) antibody was obtained from Millipore (Billerica, MA). Monoclonal anti-rhodopsin-1D4 epitope antibody was kindly provided by Dr. Robert Molday (University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada).

2.4. Chemicals

The OptiPrep™ density gradient was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). All other reagents were of analytical grade and purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

2.5. Isolation of photoreceptor cells by OptiPrep™ density gradient centrifugation

We prepared the isolated photoreceptor cells by the method described earlier (Gilliam et al., 2012). Briefly, 14 rod-dominant retinas and 28 cone-dominant Nrl−/− retinas were placed in Ringer’s solution [10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 130 mM NaCl, 3.6 mM KCl, 12 mM MgCl2, 1.2 mM CaCl2, and 0.02 mM EDTA] containing 8% OptiPrep™ and were gently vortexed for 1 min. We repeated this process five times. The pooled crude lysate was placed on top of the 10–40% OptiPrep™ step gradient. We spun the gradients at 19,210 × g for 60 min at 4°C. After centrifugation, we collected 22 fractions with each 200 μl from top to bottom of each tube (4.5 ml gradient/tube). Protein localization was examined using immunoblot analysis. We repeated these experiments more than three times. Each time, we observed consistent results, in terms of fractionation and phosphorylation.

2.6. Immunoblot analysis

Ten micrograms of retinal proteins or 1–10 μl of OptiPrep™ density gradient fractions were run on 10% SDS-PAGE, followed by protein blotting onto nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking the membranes with 5% non-fat dry milk powder (Bio-Rad) or 5% bovine serum albumin (Sigma) for 45– 60 min at room temperature, blots were incubated with anti-rhodopsin (1:10,000), anti-IR (1:1000), anti-IGF-1R (1:1000), anti-PTP1B (1:1000), anti-pAkt (1:1000), anti-Akt (1:1000), anti-Grb14 (1:1000), anti-Shp2 (1:1000), and anti-Src (1:1000) antibodies overnight at 4°C. Then, the blots were washed and incubated with HRP-coupled anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies for 60 min at room temperature. After washing, blots were developed with enhanced SuperSignal™ West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and were visualized using a Kodak Imager with chemiluminescence capability.

3. Results

3.1. Localization of IR signaling proteins in rod outer and inner segments

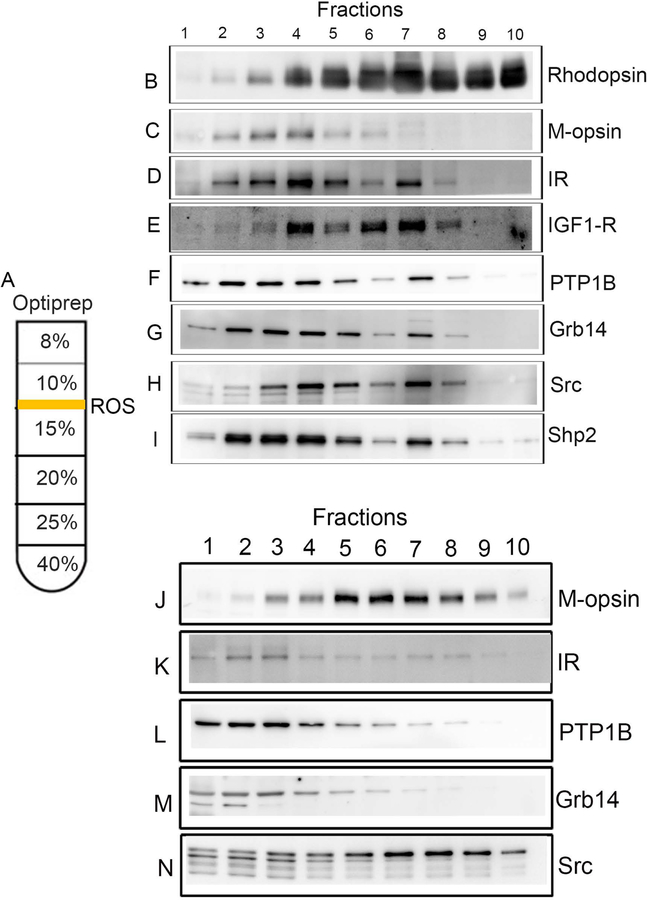

One of the technical challenges in the photoreceptor field is the isolation of photoreceptor cells to study the protein expression in outer and inner segments. A low-speed, briefly vortexed retina preparation on OptiPrep™ density centrifugation has been shown to yield outer segments with attached inner segments of photoreceptor cells (Gilliam et al., 2012, He et al. , 2016). We have employed this technique and isolated photoreceptors from rod-dominant (Balb/c mice) and cone-dominant (Nrl−/− mice) retina (Fig. 2A). We used rhodopsin as a rod photoreceptor maker and M-opsin as a cone photoreceptor marker on the OptiPrep™ fractions (Fig.2B and 2C). It is interesting to note that the separation of rod rhodopsin (Fig.2A) and cone M-rhodopsin (Figure 2B) patterns are different on OptiPrep™, suggesting that cone and rod photoreceptors could be separated on OptiPrep™ by altering the percentages of OptiPrep™. The IR signaling pathway is mediated through PTP1B, Grb14, and Src. We examined their expression on OptiPrep™ samples, employing antibodies against IR, IGF-1R, PTP1B, Grb14, Shp2, and Src. We found that IR, PTP1B, Grb14, and Src show two peaks on OptiPrep™. One of the peaks co-eluted with rhodopsin (Fig. 2D–I); this peak represents the photoreceptor outer segments. The other peak may represent photoreceptor inner segments. These experiments suggest that the IR and its signaling molecules are present in rod outer and inner segments.

Figure 2. Biochemical characterization of IR signaling protein on isolated photoreceptor cells from Balb/c mice and Nrl−/− mice.

Retinal homogenates from Balb/c mice and Nrl−/− mice were subjected to OptiPrep™ (8–40%) density gradient centrifugation (A). Fractions of inner segments and intact photoreceptors were collected from the top to the bottom of the gradients. A ten-microliter sample (one-microliter for rhodopsin) was subjected to immunoblot analysis with rhodopsin (B), M-opsin (C), IR (D), IGF1-R (E), PTP1B (F), Grb14 (G), Src (H) and Shp2 (I) antibodies. Retinal homogenates from Nrl−/− mice were subjected to OptiPrep™ (8–40%) density gradient centrifugation, and fractions of inner segments and intact photoreceptors were collected from the top to the bottom of the gradients. A ten-microliter sample (three-microliter for M-opsin) was subjected to immunoblot analysis with M-opsin (J), IR (K), PTP1B (L), Grb14 (M), and Src (N) antibodies. The image shown is representative of 3 individual preparations (n=3).

3.2. Localization of IR signaling proteins in cone outer and inner segments

We previously reported the expression of IR signaling proteins in the cone-dominant retina (Rajala et al., 2013a). In general, rodent retina is 95% rods and 1–2% cones. Mice lacking the transcriptional factor neural retina leucine (Nrl) zipper gene cannot make rods, due to a block in rod differentiation that gives rise to an all-cone retina (Mears et al., 2001). Biochemically, Nrl−/− mouse cones are indistinguishable from normal cones (Daniele et al. , 2005, Mears et al., 2001, Nikonov et al. , 2005, Zhu et al. , 2003).

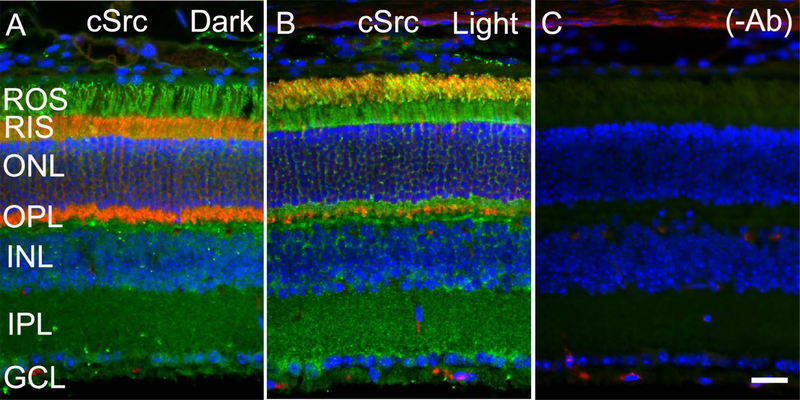

In the present study, we examined their presence in cone photoreceptor cells from Nrl−/− mouse retina, isolated on OptiPrep™. We used M-opsin as a cone photoreceptor marker on the OptiPrep™ fractions (Fig. 2J). We tested for the expression of IR, PTP1B, Grb14, and Src. Similar to rod photoreceptor cells; we found the expression of IR signaling proteins, PTP1B, Grb14, and Src in cone photoreceptors (Fig.2K–N). Our data suggest that the IR and its signaling proteins co-migrate, with or without peak M-rhodopsin. The fractions that do not co-elute with M-opsin may represent inner segments, while the M-opsin-eluted fractions may represent cone outer segments. These results suggest that IR signaling proteins are expressed in both outer and inner segments in cones. Our previous immunohistochemical studies show the expression of insulin receptor signaling proteins in both outer and inner segments of photoreceptors. To confirm our OptiPrep™ data, we stained dark- and light-adapted mouse retina sections with cSrc antibody. Arrestin immunohistochemistry was used to confirm the dark- and light-adaptation conditions. In the dark-adapted retina, arrestin is predominantly localized to rod inner segments and the outer plexiform layer of the retina and upon light-adaptation (300 lux for 30 min), arrestin translocates to rod outer segments. Consistent with the Opti-Prep fractionation, we found the expression of cSrc (Fig. 3A–C) in both the outer segment and inner segments of the photoreceptors.

Figure 3. Immunofluorescence analysis of cSrc in outer and inner segments of photoreceptor cells.

Prefer-fixed sections of the dark- (A) and light-adapted (B) mouse retina were stained for cSrc (A, B, green), and arrestin (A-B, red) antibody. Panel C represents the omission of the primary antibody. ROS, rod outer segments; RIS, rod inner segments; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer. Scale bar = 50 μm.

3.3. Light-dependent activation of Akt in outer and inner segments of photoreceptors

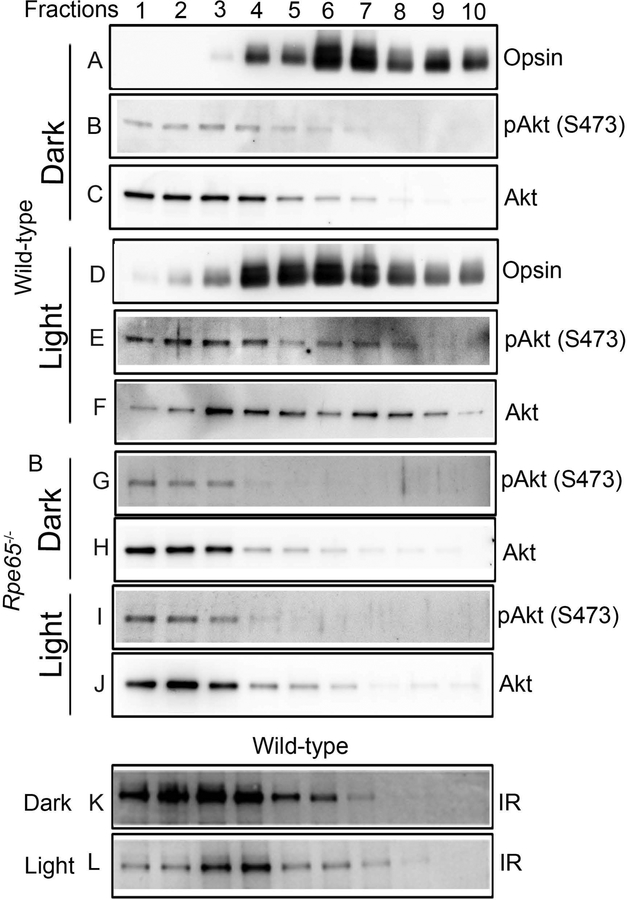

We previously reported that light-dependent IR activation in outer segments results in the activation of Akt in inner segments (Li et al. , 2008). We examined this phenomenon in isolated rod photoreceptors prepared on OptiPrep™ with an anti-phospho-Akt (S473) antibody. We used rhodopsin as a rod photoreceptor maker on the OptiPrep™ fractions (Fig.4A and 4D). The total Akt levels in dark-adapted conditions are higher in the inner segment region than in the outer segment area (Fig. 4C, Fractions 1–4 vs. Fractions 5–7). Immunoblot analysis indicated weak phosphorylation of Akt in dark-adapted conditions (Fig. 4B). This weak phosphorylation is more pronounced in the inner segment region than in the outer segment area (Fig. 4B, Fractions 1–4). Under light-adapted conditions, the total Akt levels were redistributed across the entire photoreceptor (Fig. 4F). The phosphorylation of Akt was also enhanced and could be observed in both inner and outer segment regions (Fig. 4E). These results, however, do not indicate whether light activation causes Akt phosphorylation in the inner segments and then moves to the outer segments, or whether the Akt activation occurs simultaneously in outer and inner segments.

Figure 4. Biochemical characterization of Akt phosphorylation on isolated photoreceptor cells from dark- and light-adapted wild-type and Rpe65−/− mice.

Retinal homogenates from dark- and light-adapted wild-type and Rpe65−/− mice were subjected to OptiPrep (8–40%) density gradient centrifugation, and fractions were collected from the top to the bottom of the gradients. A ten-microliter sample (one-microliter for rhodopsin) was subjected to immunoblot analysis with rhodopsin (A, D), pAkt (S473) (B, E, G, I), and Akt (C, F, H, J) antibodies. Retina samples from dark- and light-adapted mice were subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-IR antibody (K, L). The image shown is representative of 3 individual preparations (n=3).

3.4. Absence of light-dependent activation of Akt in outer and inner segments of photoreceptors isolated from Rpe65−/− mice.

We previously reported that the IR and its signaling proteins are activated through photobleaching of rhodopsin (Basavarajappa et al., 2011, Rajala et al., 2007, Rajala et al., 2016). In this experiment, we prepared photoreceptor cells on OptiPrep™ from dark and light-adapted retinal pigment epithelium 65 (Rpe65) knockout mice. Mice lacking Rpe65 protein in the RPE cell do not photobleach since the chromophore 11cis-retinal does not regenerate in the visual cycle (Redmond et al. , 1998). OptiPrep™ fractions were probed with anti-pAkt (S473) and anti-Akt antibodies. Our results indicate that total Akt levels in Rpe65−/− mice under dark- and light-adapted conditions are identical to the fractionation pattern of dark-adapted wild-type mice (Fig. 4H and 4J). The Akt phosphorylation is localized to the inner segment area under both dark- and light-adapted conditions in Rpe65−/− mouse retinas (Fig. 4G and I). Our results show that Akt activation in outer segments and enhancement of Akt activation in the inner segment area is lost in light-adapted Rpe65−/− mouse retinas (Fig. 4G and I) compared with light-adapted wild-type mouse retinas (Fig. 4E). These findings support the idea that rhodopsin activation regulates the Akt activation in photoreceptor cells. We made an interesting observation in this study that in dark-adapted conditions, the IR expression is higher in both the inner segment and outer segment area compared to light-adapted conditions (Fig. 4K and L).

4. Discussion

In general, physiological processes are governed by dynamic protein-protein interactions. These protein-protein interacting complexes are formed at transmembrane receptors, scaffold proteins, adapter proteins, and effector molecules. The unregulated association of signaling complexes or failure to associate with specific signaling modules has significant clinical consequences. Exploration of these complexes and their signaling pathways is an active area of research. These investigations aim to identify the composition and function of signaling complexes and their mechanisms of association.

Studies from our laboratory clearly suggest that photoexcitation of rhodopsin, but not transducin activation, signals IR activation (Rajala et al., 2007), inhibition of PTP1B activity (Rajala et al., 2010), Grb14 translocation to outer segments from inner segments (Gupta et al. , 2010, Rajala et al., 2009a), Src activation, and Grb14 phosphorylation (Basavarajappa et al., 2011). In other cell types, G-protein-coupled receptors are known to regulate tyrosine kinase signal transduction pathways (Luttrell et al. , 1999, Luttrell et al. , 1997). The idea that rhodopsin can initiate a non-canonical signaling pathway is supported by our studies showing that the IR signaling pathway is activated through photobleaching of rhodopsin (Rajala et al., 2007, Rajala et al., 2009a). The perturbation of the IR signaling pathway leads to retinal degeneration (Punzo et al., 2009, Rajala et al., 2016). Our earlier findings clearly suggest that IR signaling is important for photoreceptor functions, that activation of this pathway in hostile environments protects photoreceptor neurons from degeneration, and that these molecular processes are amenable to pharmacological modulation. We propose that light activation of IR signaling in rods and cones is one of the endogenous neuroprotective pathways used by photoreceptors to survive in a hostile environment that includes high oxygen consumption, light, and high levels of easily oxidizable polyunsaturated fatty acids, the effects of any or all of which may be exacerbated by retina-specific mutations that kill photoreceptors.

We previously reported the activation of the IR signaling pathway in rod outer segments (Rajala et al., 2007), however, the expression of IR and its signaling proteins in the inner segments is not known. Isolation of inner segment preparations is technically challenging. It has been shown previously that OptiPrep™ density centrifugation has been shown to yield outer segments with attached inner segments of photoreceptor cells (Gilliam et al., 2012, He et al., 2016). OptiPrep™ is a non-ionic iodixanol-based medium with a density of 1.320 g/ml has been extensively used to isolate cell organelles such as nuclei, mitochondria, peroxisomes, lysosomes, endosomal subfractions (Graham, 2001, Van Veldhoven et al. , 1996). OptiPrep™ density gradient has also been used to isolate membrane fractions, such as Golgi membranes, endoplasmic reticulum, specific plasma membrane domains (Graham, 2002, Schaub et al. , 2006, Shah and Sehgal, 2007). Using OptiPrep™, we were able to isolate both rod and cone photoreceptor outer and inner segments area and demonstrated the expression of IR and its signaling proteins. We previously reported the light-dependent activation of Akt, a downstream effector of IR (Li et al., 2008) and IGF-1R (Dilly and Rajala, 2008) in vivo. On isolated photoreceptor cells on OptiPrep™ show Akt activation in a light-dependent manner in both inner and outer segment regions of rods. Consistent with our earlier studies that mice lacking Rpe65 protein failed to activate the IR signaling pathway (Rajala et al., 2007), we also observed the absence of Akt activation in the outer segments of Rpe65−/− mouse rod photoreceptor cells. Our studies clearly suggest that OptiPrep™ is an ideal gradient to separate inner and outer segments regions of rods and cones to study the expression and localization of proteins.

We and others have demonstrated a light-dependent activation of insulin receptor signaling in the outer segments (Rajala et al., 2007) and insulin receptor signaling pathway elicited by light in photoreceptor nuclei (Natalini et al. , 2016). In our earlier publications, we showed the expression insulin receptors (Rajala et al., 2002, Rajala et al. , 2009b, Yu et al. , 2004), Grb14 (Rajala et al., 2009a), PTP1B (Rajala and Rajala, 2013, Rajala et al., 2009c), Akt (Li et al. , 2007, Li et al., 2008) in the outer and inner segment of photoreceptors. Photoreceptor nuclei and pure outer segment membranes are easy to isolate from the retina, but not inner segments. One of technical limitation in this study that we were unable to conduct immunohistochemistry on the isolated photoreceptors due to their small size as opposed to photoreceptors isolated from bovine retina (Ivanovic et al. , 2011, Rajala et al., 2002). However, the purpose of this manuscript is to develop a method to isolate the inner segment from the outer segments of the photoreceptor cells. This would enable scientists to understand inner segment proteomic perturbations arising from disease pathology in a more sensitive manner than immunostaining.

5. Conclusions

In the present study, we found that IR and IR signaling proteins are expressed in both the outer and inner segments of the photoreceptors. The purpose of this manuscript is to develop a method to isolate the inner segment from the outer segments of the photoreceptor cells. Identification of the signaling complexes will be helpful for therapeutic targeting in disease conditions.

Acknowledgments and funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (EY030024, EY00871, and NEI Core grant EY021725) and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc. to the Department of Ophthalmology. The authors acknowledge Ms. Kathy J. Kyler, Staff Editor, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, for editing this manuscript.

Abbreviation list

- IR

insulin receptor

- PTP1B

protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B

- Grb14

growth factor receptor-bound protein 14

- Rpe65

retinal pigment epithelium protein 65

- Nrl

neural retina leucine zipper

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Basavarajappa DK, Gupta VK, Dighe R, Rajala A, Rajala RV. Phosphorylated Grb14 Is an Endogenous Inhibitor of Retinal Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 1B, and Light-Dependent Activation of Src Phosphorylates Grb14. MolCell Biol. 2011;31:3975–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JR. Insulin receptor activation in deletion 11q chronic lymphocytic leukemia. ClinCancer Res. 2011;17:2605–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniele LL, Lillo C, Lyubarsky AL, Nikonov SS, Philp N, Mears AJ, et al. Cone-like morphological, molecular, and electrophysiological features of the photoreceptors of the Nrl knockout mouse. Invest OphthalmolVisSci. 2005;46:2156–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilly AK, Rajala RV. Insulin growth factor 1 receptor/PI3K/AKT survival pathway in outer segment membranes of rod photoreceptors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:4765–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fort PE, Losiewicz MK, Reiter CE, Singh RS, Nakamura M, Abcouwer SF, et al. Differential roles of hyperglycemia and hypoinsulinemia in diabetes induced retinal cell death: evidence for retinal insulin resistance. PLoSOne. 2011;6:e26498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam JC, Chang JT, Sandoval IM, Zhang Y, Li T, Pittler SJ, et al. Three-dimensional architecture of the rod sensory cilium and its disruption in retinal neurodegeneration. Cell. 2012;151:1029–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosbell AD, Favilla I, Baxter KM, Jablonski P. Insulin receptor and insulin receptor substrate-I in rat retinae. ClinExperimentOphthalmol. 2000;28:212–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JM. Isolation of nuclei and nuclear membranes from animal tissues. Current protocols in cell biology. 2001;Chapter 3:3.10.1–3..9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JM. OptiPrep density gradient solutions for mammalian organelles. TheScientificWorldJournal. 2002;2:1440–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta VK, Rajala A, Daly RJ, Rajala RV. Growth factor receptor-bound protein 14: a new modulator of photoreceptor-specific cyclic-nucleotide-gated channel. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:861–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy S, Tremblay ML. Protein tyrosine phosphatases: new markers and targets in oncology? CurrOncol. 2008;15:5–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He F, Agosto MA, Anastassov IA, Tse DY, Wu SM, Wensel TG. Phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate is light-regulated and essential for survival in retinal rods. SciRep. 2016;6:26978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanovic I, Allen DT, Dighe R, Le YZ, Anderson RE, Rajala RV. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling in retinal rod photoreceptors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:6355–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Anderson RE, Tomita H, Adler R, Liu X, Zack DJ, et al. Nonredundant role of Akt2 for neuroprotection of rod photoreceptor cells from light-induced cell death. JNeurosci. 2007;27:203–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Rajala A, Wiechmann AF, Anderson RE, Rajala RV. Activation and membrane binding of retinal protein kinase Balpha/Akt1 is regulated through light-dependent generation of phosphoinositides. JNeurochem. 2008;107:1382–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li PM, Zhang WR, Goldstein BJ. Suppression of insulin receptor activation by overexpression of the protein-tyrosine phosphatase LAR in hepatoma cells. Cell Signal. 1996;8:467–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttrell LM, Ferguson SS, Daaka Y, Miller WE, Maudsley S, Della Rocca GJ, et al. Beta-arrestin-dependent formation of beta2 adrenergic receptor-Src protein kinase complexes. Science. 1999;283:655–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttrell LM, van Biesen T, Hawes BE, Koch WJ, Krueger KM, Touhara K, et al. G-protein-coupled receptors and their regulation: activation of the MAP kinase signaling pathway by G-protein-coupled receptors. AdvSecond Messenger Phosphoprotein Res. 1997;31:263–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mears AJ, Kondo M, Swain PK, Takada Y, Bush RA, Saunders TL, et al. Nrl is required for rod photoreceptor development. NatGenet. 2001;29:447–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natalini PM, Mateos MV, Ilincheta de Boschero MG, Giusto NM. Insulin-related signaling pathways elicited by light in photoreceptor nuclei from bovine retina. Exp Eye Res. 2016;145:36–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikonov SS, Daniele LL, Zhu X, Craft CM, Swaroop A, Pugh EN Jr. Photoreceptors of Nrl −/− mice coexpress functional S- and M-cone opsins having distinct inactivation mechanisms. JGenPhysiol. 2005;125:287–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punzo C, Kornacker K, Cepko CL. Stimulation of the insulin/mTOR pathway delays cone death in a mouse model of retinitis pigmentosa. NatNeurosci. 2009;12:44–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajala A, Anderson RE, Ma JX, Lem J, Al Ubaidi MR, Rajala RV. G-protein-coupled Receptor Rhodopsin Regulates the Phosphorylation of Retinal Insulin Receptor. JBiolChem. 2007;282:9865–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajala A, Daly RJ, Tanito M, Allen DT, Holt LJ, Lobanova ES, et al. Growth factor receptor-bound protein 14 undergoes light-dependent intracellular translocation in rod photoreceptors: functional role in retinal insulin receptor activation. Biochemistry. 2009a;48:5563–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajala A, Dighe R, Agbaga MP, Anderson RE, Rajala RV. Insulin Receptor Signaling in Cones. JBiol Chem. 2013a;288:19503–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajala A, Tanito M, Le YZ, Kahn CR, Rajala RV. Loss of neuroprotective survival signal in mice lacking insulin receptor gene in rod photoreceptor cells. JBiolChem. 2008;283:19781–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajala A, Wang Y, Rajala RV. Activation of oncogenic tyrosine kinase signaling promotes insulin receptor-mediated cone photoreceptor survival. Oncotarget. 2016;7:46924–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajala RV, Anderson RE. Rhodopsin-regulated insulin receptor signaling pathway in rod photoreceptor neurons. MolNeurobiol. 2010;42:39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajala RV, Basavarajappa DK, Dighe R, Rajala A. Spatial and temporal aspects and the interplay of Grb14 and protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B on the insulin receptor phosphorylation. Cell CommunSignal. 2013b;11:96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajala RV, Gardner TW. Burning fat fuels photoreceptors. NatMed. 2016;22:342–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajala RV, McClellan ME, Ash JD, Anderson RE. In vivo regulation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase in retina through light-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of the insulin receptor beta-subunit. JBiolChem. 2002;277:43319–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajala RV, McClellan ME, Chan MD, Tsiokas L, Anderson RE. Interaction of the Retinal Insulin Receptor beta-Subunit with the P85 Subunit of Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5637–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajala RV, Rajala A. Neuroprotective role of protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B in rod photoreceptor neurons. Protein Cell. 2013;4:890–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajala RV, Rajala A, Brush RS, Rotstein NP, Politi LE. Insulin receptor signaling regulates actin cytoskeletal organization in developing photoreceptors. JNeurochem. 2009b;110:1648–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajala RV, Tanito M, Neel BG, Rajala A. Enhanced retinal insulin receptor-activated neuroprotective survival signal in mice lacking the protein-tyrosine phosphatase-1B gene. JBiolChem. 2010;285:8894–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajala RV, Wiskur B, Tanito M, Callegan M, Rajala A. Diabetes reduces autophosphorylation of retinal insulin receptor and increases protein-tyrosine phosphatase-1B activity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009c;50:1033–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond TM, Yu S, Lee E, Bok D, Hamasaki D, Chen N, et al. Rpe65 is necessary for production of 11-cis-vitamin A in the retinal visual cycle. NatGenet. 1998;20:344–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter CE, Sandirasegarane L, Wolpert EB, Klinger M, Simpson IA, Barber AJ, et al. Characterization of insulin signaling in rat retina in vivo and ex vivo. AmJPhysiol EndocrinolMetab. 2003;285:E763–E74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaub BE, Berger B, Berger EG, Rohrer J. Transition of galactosyltransferase 1 from trans-Golgi cisterna to the trans-Golgi network is signal mediated. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:5153–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seino S, Bell GI. Alternative splicing of human insulin receptor messenger RNA. BiochemBiophysResCommun. 1989;159:312–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah MB, Sehgal PB. Nondetergent isolation of rafts. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;398:21–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich A, Bell JR, Chen EY, Herrera R, Petruzzelli LM, Dull TJ, et al. Human insulin receptor and its relationship to the tyrosine kinase family of oncogenes. Nature. 1985;313:756–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Veldhoven PP, Baumgart E, Mannaerts GP. Iodixanol (Optiprep), an improved density gradient medium for the iso-osmotic isolation of rat liver peroxisomes. Anal Biochem. 1996;237:17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlahovic G, Crawford J. Activation of tyrosine kinases in cancer. Oncologist. 2003;8:531–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburg O. On respiratory impairment in cancer cells. Science. 1956a;124:269–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956b;123:309–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Rajala RV, McGinnis JF, Li F, Anderson RE, Yan X, et al. Involvement of insulin/phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt signal pathway in 17 beta-estradiol-mediated neuroprotection. JBiolChem. 2004;279:13086–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Brown B, Li A, Mears AJ, Swaroop A, Craft CM. GRK1-dependent phosphorylation of S and M opsins and their binding to cone arrestin during cone phototransduction in the mouse retina. JNeurosci. 2003;23:6152–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]