Abstract

Aims/Introduction

Amelioration of renal impairment is the key to diabetic nephropathy (DN) therapy. The progression of DN is closely related to podocyte dysfunction, but the detailed mechanism has not yet been clarified. The present study aimed to explore the renal impairment amelioration effect of berberine and related mechanisms targeting podocyte dysfunction under the diabetic state.

Materials and Methods

Streptozotocin (35 mg/kg) was used to develop a DN rat model together with a high‐glucose/high‐lipid diet. Renal functional parameters and glomerular ultrastructure changes were recorded. The alterations of phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase (PI3K), protein kinase B (Akt) and phosphorylated Akt in the kidney cortex were determined by western blot. Meanwhile, podocyte dysfunction was induced and treated with berberine and LY294002. After that, podocyte adhesion functional parameters, protein biomarker and the alterations of the PI3K–Akt pathway were detected.

Results

Berberine reduces the increased levels of biochemical indicators, and significantly improves the abnormal expression of PI3K, Akt and phosphorylated Akt in a rat kidney model. In vitro, a costimulating factor could obviously reduce the podocyte adhesion activity, including decreased expression of nephrin, podocin and adhesion molecule α3β1 levels, to induce podocyte dysfunction, and the trends were markedly reversed by berberine and LY294002 therapy. Furthermore, reduction of PI3K and phosphorylated Akt levels were observed in the berberine (30 and 60 μmol/L) and LY294002 (40 μmol/L) treatment group, but the Akt protein expression showed little change.

Conclusions

Berberine could be a promising antidiabetic nephropathy drug through ameliorating renal impairment and inhibiting podocyte dysfunction in diabetic rats, and the underlying molecular mechanisms might be involved in the regulation of the PI3K–Akt signaling pathway.

Keywords: Berberine, Phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase–protein kinase B signaling pathway, Podocyte dysfunction

The phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase–protein kinase B signaling pathway in podocytes might be an important therapeutic target in diabetic nephropathy treatment. Berberine will be a promising antidiabetic nephropathy drug.

![]()

Introduction

Diabetic nephropathy (DN), a capillary vessel syndrome of diabetes mellitus, is believed to be a prevalent cause for the ongoing advance of end‐stage renal disease1. The main pathological characteristics of DN, caused by metabolic disorders, include excessive mesangial proliferation, glomerular hypertrophy, thickening of basement membrane, podocyte dysfunction and so on2. Earlier studies have shown that the pathogenesis of DN is complex, and is the result of multiple pathogenic factors. Hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, oxidative stress, hemodynamic abnormalities, genetic factors and so on are reported to accelerate the progress of DN, but the precise mechanism has not been fully elucidated3.

Hyperglycemia is one of the most significant characteristics4, and transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF‐β1) is the foremost cytokine to promote renal fibrosis5. During DN progression, a study found that TGF‐β1 combined with hyperglycemia could significantly increase podocyte apoptosis and injury6. Meanwhile, the signal transmission of TGF‐β1 between different cells in the kidney is mainly achieved by signaling pathways. It has been confirmed that Smads protein signal transduction pathway is the most important pathway7. In addition, a study has shown that TGF‐β1 could also activate the phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase–protein kinase B (PI3K–Akt) signaling pathway8. The PI3K–Akt pathway is involved in many cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, tumor growth and cell cycle progression9, 10, 11. Therefore, it is important to know whether there is a relationship among costimulation of TGF‐β1 and high glucose, podocyte apoptosis and the PI3K–Akt pathway, and the details.

In recent years, considerable attention has been focused on traditional Chinese medicine during the treatment of DN. Berberine (BBR), a famous herb component generally isolated from rhizoma coptidis rhizomes and cortex phellodendri, has been playing an potential role in the prevention of diabetes and certain complications12. It has been shown that BBR not only lower high glucose levels, regulate the blood lipid metabolism disorder, diastole endothelial vessels and reduce kidney inflammation, but could also improve insulin resistance and enhance insulin activity under diabetic conditions13. Our prophase research noted that BBR could obviously alleviate kidney inflammation of DN in rats mainly by reducing the expression of inflammatory cytokines, such as TGF‐β1, which could delay the development of DN14.

Growing evidence suggests that podocyte injury could aggravate the development of DN by interfering with the formation of proteinuria15. In the meantime, investigations have found that BBR could decrease the blood glucose level of diabetic mice by modulating the protein level of phosphorylated Akt (p‐Akt)16. BBR might have desired application for the prevention of DN; nevertheless, the effect of BBR on podocytes in DN remains to be elucidated. Thus, it is necessary to explore the internal relationships among the protective effect of BBR, podocyte dysfunction and the PI3K–Akt signaling pathway.

Methods

Materials

Streptozocin (STZ; S0130) was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). BBR and enalapril were kindly provided by Anhui Provincial Hospital, Hefei, Anhui, China. Rabbit anti‐nephrin (140629) and anti‐α3β1 (bs‐1057R) were obtained from Biosynthesis Biotechnology (Beijing, China). Rabbit anti‐podocin (L0913) antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Rabbit anti‐Akt (4691S) and anti‐phospho‐Akt (Ser473) antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Biotechnology (Boston, MA, USA). Rabbit anti‐nephrin (ab136894) antibody was purchased from Abcam Biotechnology (Cambridge, UK). The SuperSignal West Femto Trial kit (34094) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Hexokinase (N4006) and PI3K–Akt inhibitor LY294002 (L9908) were obtained from Sigma‐Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Murine interferon‐γ (315‐05‐100) was purchased from PeproTech Biological Technology (Miami, FL, USA). All other chemicals applied in these experiments were of analytical grade and were acquired from commercial sources.

Experimental protocol

A total of 85 mature Sprague–Dawley rats (male, 180 ± 20 g, grade II, certificate no. 028) were purchased from the Animal Department of Anhui Medical University. Rats were fed with a standard diet and water ad libitum, and adapted to the experimental conditions (20 ± 2°C, humidity of 60 ± 5%) for 7 days. Then, rats were fed a high‐glucose/high‐lipid diet, with a single intraperitoneal injection of STZ (35 mg/kg) dissolved in a 0.1 mmol/L chilled citrate‐phosphate buffer (pH 4.5) to develop a type 2 diabetes rat model. Rats were randomly assigned to seven groups: the normal control group (NC), the DN model group (DN), DN rats treated with different dosages of BBR (50, 100 and 200 mg/kg) groups (BBR[×mg/kg]), the DN with metformin (1 mg/kg) group (DN + metformin) and the DN with captopril (15 mg/kg) group (DN + captopril). Before the experiment, 10 rats were assigned to the NC group with only citrate‐phosphate buffer injected. The development of hyperglycemia (type 2 diabetes) in rats was confirmed by estimating the fasting blood glucose (FBG) level (≥11.1 mmol/L) 72 h after STZ injection16, and only uniformly diabetic rats were included in the DN control and drug treatment groups. Rats in the NC and DN groups were given an equal volume of vehicle (carboxymethyl cellulose), and the BBR treatment groups received BBR dissolved in 0.5% carboxymethyl cellulose at doses of 50, 100 and 200 mg/kg bodyweight per day for 8 weeks intragastrically. After 8 weeks, kidney samples were rapidly isolated and frozen in liquid nitrogen or fixed in 10% formaldehyde buffer. Rat femoral arterial blood serum and urine were collected, which were extracted after centrifugation and stored at −80°C until analysis.

Animal experiments were carried out ethically, and where relevant conformed to national guidelines for animal usage in research.

Measurement of renal functional and biochemical parameters

Fasting blood glucose levels were measured every 2 weeks using tail vein blood samples. Blood samples were obtained from the femoral artery and allowed to clot for 30 min at 4°C, then centrifuged at 1,268 g for 10 min. Blood supernatant was collected for measurement of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine (SCr) by using an automatic biochemistry analyzer (Hitachi Model 7600 Series; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). During the experiment, urine samples were obtained from rats housed in metabolic cages for subsequent measurement of urine podocalyxin (UPCX) by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay.

Western blot analysis

Kidney tissues and cultured cells were washed with precooled phosphate buffer, and lysed with lyolysis of radioimmunoprecipitation assay and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride mixture (radioimmunoprecipitation assay : phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride = 99:1). The lyolysis liquids were collected and centrifuged at 13,046 g at 4°C for 10 min, and the protein supernatant samples were denatured by boiling for 10 min at 100°C, resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, then electroblotted at 4°C and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) by electroblotting in transfer buffer (25 mmol/L Tris‐base, 192 mmol/L glycine and 20% methanol). Afterwards, the polyvinylidene difluoride were blocked in 5% (w/v) non‐fat milk for 2 h, and the membranes were incubated with rabbit anti‐nephrin (1:100), anti‐α3β1 (1:100), anti‐podocin (1:200), anti‐PI3K‐p85 (1:500), anti‐Akt (1:500), anti‐p‐Akt (1:500) and mouse anti‐β‐actin (1:1,000) antibody with gentle agitation overnight at 4°C. The membranes were washed three times with 0.05% Tween 20 with phosphate‐buffered saline, and were incubated with the secondary antibody for 2 h. All of the western blot experiments in the present study were carried out at least three times, and the results were reproducible.

Cell culture

A conditionally immortalized rat podocyte line was cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum at the suitable condition (33–37°C and 5% CO2).

Cell adhesion assay

Cultured cells were digested, suspended and then planted in six‐well plates at 1 × 104 cells/well. High glucose (30 mmol/L) combined with TGF‐β1 (5 ng/mL) was chosen as the costimulating factor to induce podocyte dysfunction for 48 h, and then BBR and LY294002 treatment processing lasted for 48 h, respectively. Cells were divided into the following groups: (i) the normal glucose group (NC) as controls incubated in RPMI 1640 containing 5 mmol/L glucose; (ii) the high‐glucose group (HG) incubated in RPMI 1640 containing 30 mmol/L glucose; (iii) the TGF‐β1 group incubated in RPMI 1640 containing 5 ng/mL TGF‐β1; (iv) the costimulated group incubated in RPMI 1640 containing 30 mmol/L glucose plus 5 ng/mL TGF‐β1; (v) the costimulated group treated with different concentrations of BBR (1.825, 3.75, 7.5, 15, 30, 60, 90 and 120 μmol/L); and (vi) the costimulated group treated with LY294002 (40 μmol/L). Cell adhesion assay was carried out as described previously17. Briefly, rat‐tail type I collagen was dissolved in a 0.1% solution in 0.1 N acetic acid, added to each well of a 96‐well enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay plate, and incubated overnight at 4°C. Differentiated podocytes were suspended in medium containing 1% fetal calf serum at 1 × 105 cells/well and incubated for 6 h. Phosphate‐buffered saline was used to remove any unattached cells and then incubated with 50 mmol/L citrated buffer (pH 5.0) containing 3.75 mmol/L p‐nitrophenyl‐N‐acetyl‐D‐glycosamide and 0.25% Triton X‐100 for 1 h at 37°C. A glycine buffer (50 mmol/L, pH 10.4) containing 5 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid was then added to deactivate enzyme activity. The plates were read at a wavelength of 405 nm in a Bio‐Rad microplate reader (Bio‐Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

All the values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. All the experiments were carried out in triplicate and ‘n’ denotes the sample size in each group. SPSS software (version 16.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Statistical analyses of data were carried out by one‐way anova: post‐hoc multiple comparisons. A difference was considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

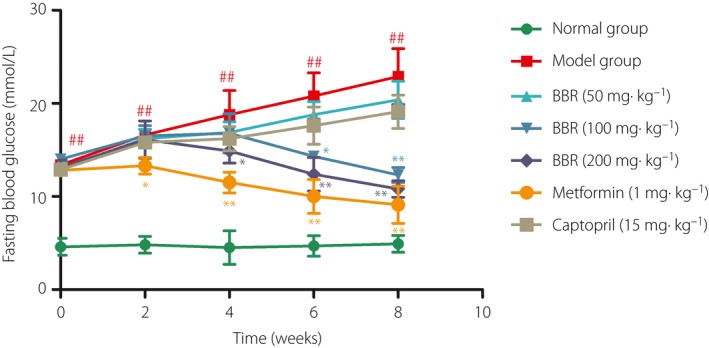

Effect of BBR on FBG levels

FBG levels were detected twice a week after diabetes was induced by STZ injection (Figure 1). There was a significant increase in FBG in diabetic model rats compared with normal rats (P < 0.01). At the fourth and sixth week after BBR administration, the BBR 100 and 200 mg/kg group showed significantly lower FBG levels compared with those in the DN group (P < 0.05), then the trends became more pronounced (P < 0.01). The metformin (1 mg/kg) positive treatment group showed a significant decline in FBG levels from the second week (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01). However, the BBR 50 mg/kg and the captopril 15 mg/kg treatment group had no obvious effect in comparison with the FBG levels of DN rats. The results were similar to that of our previous study, which has been published in the European Journal of Pharmacology 14.

Figure 1.

Effect of berberine (BBR) on fasting blood glucose of diabetic nephropathy rats during different periods. # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01 versus normal group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.05 versus model group (mean ± standard deviation).

Effect of BBR on renal functional parameters

After dosing with BBR for 8 weeks, we detected the levels of BUN, SCr and UPCX. Compared with NC rats, both these three indicators in the DN group increased significantly (P < 0.01). BBR 100 and 200 mg/kg and captopril 15 mg/kg could significantly reduce the levels of BUN, SCr and UPCX of the model group to some extent (P < 0.01), whereas the metformin (1 mg/kg) treatment group showed an indistinguishable change (Table 1). The results were similar to that of our previous study, which was published in the Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 2.

Table 1.

Effects of berberine on renal functional parameters in diabetic nephropathy rats

| Group | Drug dosage (mg/kg) | n | BUN (mmol/L) | SCr (μmol/L) | PCX (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC | – | 10 | 5.06 ± 0.56 | 23.70 ± 3.05 | 0.28 ± 0.06 |

| DN | – | 7 | 13.67 ± 0.79## | 75.71 ± 5.55## | 1.19 ± 0.27## |

| BBR | 50 | 6 | 12.78 ± 0.58 | 71.50 ± 6.18 | 1.10 ± 0.18 |

| 100 | 7 | 9.56 ± 1.03** | 55.14 ± 3.84* | 0.88 ± 0.10* | |

| 200 | 7 | 8.94 ± 0.65** | 36.85 ± 3.76** | 0.63 ± 0.13** | |

| Captopril | 15 | 7 | 6.97 ± 0.95** | 29.51 ± 3.59** | 0.60 ± 0.20** |

| Metformin | 1 | 8 | 11.94 ± 1.13 | 68.50 ± 4.89 | 0.98 ± 0.24 |

Data presented as the mean ± standard deviation. ## P < 0.01 versus normal group, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 versus the diabetic nephropathy model group.

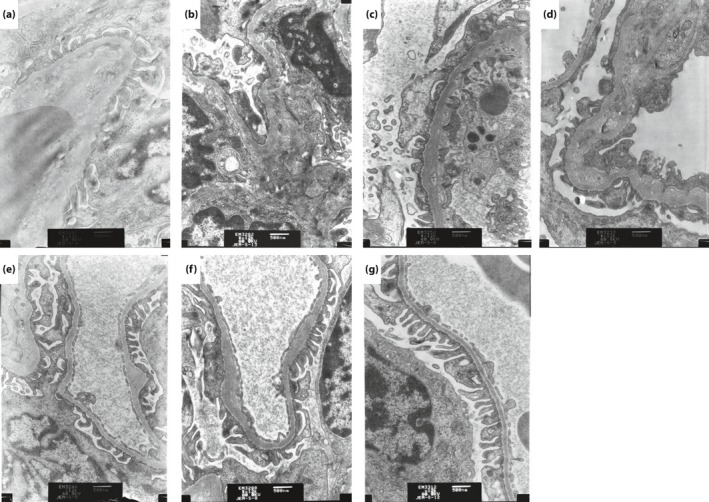

Effect of BBR on glomerular ultrastructure

The ultrastructure of the glomeruli was observed to be normal in the kidney tissue of the NC group; that is, the renal glomerular structure integrity was complete and the basement membrane thickness showed no obvious hyperplasia. Podocytes showed no obvious abnormity, and the morphological structure was well balanced (Figure 2a). Compared with the NC group, the glomerular basement membrane was obviously thickened, and fusion of podocyte foot processes, disordered arrangement and even podocyte loss were observed in the DN model group (Figure 2b). Administration of BBR 100 and 200 mg/kg and captopril 15 mg/kg could normalize the above‐mentioned abnormal alterations of the model group to a certain degree (Figure 2c–f), but there was little change in the metformin (1 mg/kg) treatment group (Figure 2g).

Figure 2.

Effect of berberine (BBR) on the glomerular ultrastructure of diabetic nephropathy rats by electron microscopy (magnification: ×12 000). (a) Normal control group; (b) model group; (c) BBR 50 mg/kg group; (d) BBR 100 mg/kg group; (e) BBR 200 mg/kg group; (f) captopril 15 mg/kg group; and (g) metformin 1 mg/kg group.

BBR ameliorated the podocyte functional proteins expression in the DN rat kidney

A previous study18 showed that the positive staining of nephrin, podocin and α3β1 integrin was mostly distributed in the surface of podocytes. The administration of BBR 50 mg/kg did not influence the protein expression of nephrin, podocin and α3β1 integrin (P < 0.05), and treatment with BBR 100 and 200 mg/kg was proven to dramatically increase those protein expressions compared with the model group (P < 0.01). Results of this section were published in Chinese Pharmacological Bulletin 18.

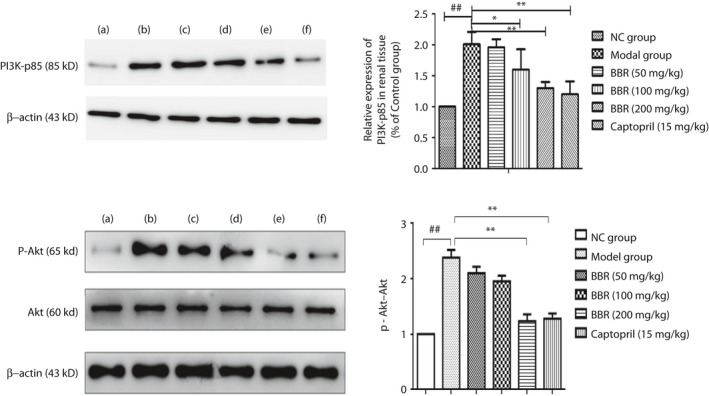

BBR affected the PI3K–Akt signaling pathway in the DN rat kidney

The data statistically suggest that after treating rate with different dosages of BBR, the total Akt protein level showed barely any change, whereas the expression of PI3K‐p85 and p‐Akt showed that there was a tendency for levels to decrease in the renal cortex (Figure 3). In the DN group, the protein expression of PI3K‐p85 increased nearly twofold higher than the NC group. The administration of BBR 100 and 200 mg/kg and captopril 15 mg/kg could decrease approximately 20, 35 and 40% of the expression of PI3K‐p85 compared with the untreated DN group (P < 0.01), as shown by western blot analysis. In addition to the expression of PI3K‐p85 in the DN rats, we examined the expression ratio of p‐Akt/Akt, and found that the expression ratio in the DN group was elevated by >60% compared with that of the NC group. Compared with the DN group, BBR 200 mg/kg and captopril positive drug treatment could reduce the protein expression ratio of p‐Akt/Akt to a different degree (P < 0.01 and P < 0.01, respectively).

Figure 3.

Berberine (BBR) affected the phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase–protein kinase B (PI3K–Akt) signaling pathway in a diabetic nephropathy rat kidney. (a) Normal group (NC); (b) model group; (c) BBR 50 mg/kg group; (d) BBR 100 mg/kg group; (e) BBR 200 mg/kg group; and (f) captopril 15 mg/kg group. ## P < 0.01 versus normal group; **P < 0.01 versus model group (mean ± standard deviation, n = 4).

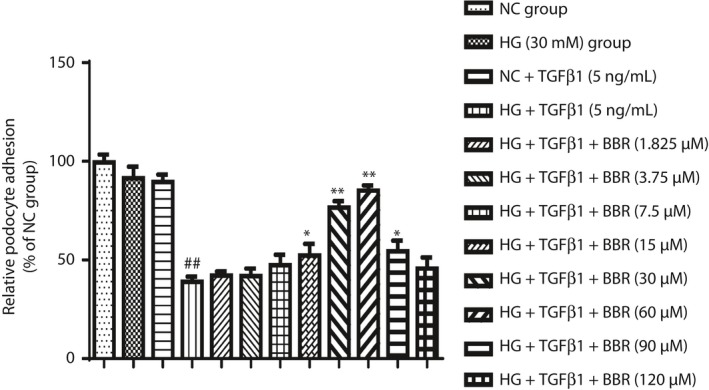

Effect of BBR on the podocyte adhesion function

Adhesion function measurement results showed that compared with the NC group, the costimulating factor could obviously reduce the podocyte adhesion activity (P < 0.01). Compared with the costimulating factor group, BBR 15, 30 and 60 μmol/L treatment showed a significant increase of the podocyte adhesion ability to varying degrees (P < 0.05, P < 0.01 and P < 0.01, respectively; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of berberine (BBR) on the podocyte adhesion function. Bar graphs show the mean of values in different groups (n = 4), the mean of values are presented as mean ± standard deviation; ## P < 0.01 versus normal control (NC) group, *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 versus high‐glucose group (HG) + transforming growth factor‐β1 (TGF‐β1) 5 ng/mL group.

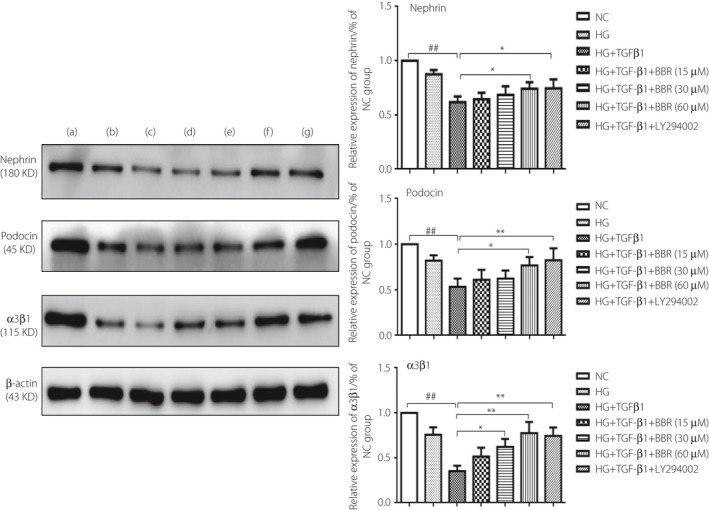

BBR ameliorated the podocyte functional proteins in podocytes stimulated by costimulation factor

The results showed that different concentrations of BBR could downregulate the protein levels of nephrin, podocin and adhesion molecule α3β1. Compared with the NC group, the HG and TGF‐β1 stimulation group could significantly reduce the protein levels of nephrin, podocin and adhesion molecule α3β1 (P < 0.01). The high concentration of BBR 60 μmol/L and LY294002 treatment groups could obviously increase the protein levels of nephrin, podocin and adhesion molecule α3β1 (P < 0.01), whereas the medium concentration of the BBR 30 μmol/L treatment group could raise the expression of adhesion molecule α3β1 sufficiently (P < 0.05). In addition, the low concentration of the BBR 15 μmol/L treatment group showed little effect on regulating the protein expression of nephrin, podocin and adhesion molecule α3β1 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Berberine (BBR) ameliorated the podocyte functional proteins in podocytes stimulated by costimulating factor. (a) Normal control (NC) group; (b) High‐glucose (HG) group; (c) HG + transforming growth factor‐β1 (TGF‐β1) group; (d) HG + TGF‐β1 + BBR 15 μmol/L; (e) HG + TGF‐β1 + BBR 30 μmol/L group; (f) HG + TGF‐β1 + BBR 60 μmol/L group; and (g) HG + TGF‐β1 + LY294002 40 μmol/L group. ## P < 0.01 versus NC group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus HG + TGF‐β1 group (mean ± standard deviation, n = 3).

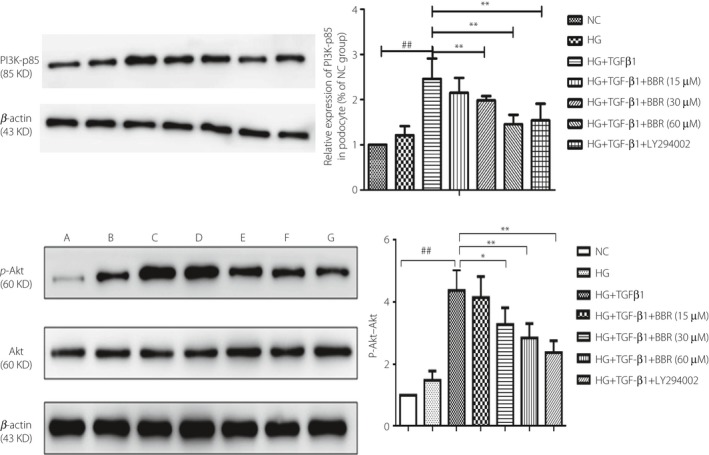

Effect of BBR on the related protein of PI3K–Akt in podocytes stimulated by costimulating factor

Western blot showed that after treating with different dosages of BBR, the total Akt protein level showed barely any change, while the PI3K and p‐Akt protein levels represented a process of ascending first and then descending (Figure 6a). We found that the tipping point time is 24 h after costimulation and treatment with drugs. Then, our focus was on the changes of the PI3K–Akt pathway at 12 h after costimulation and treatment with drugs. The specific conditions are as follows: compared with the NC group, the levels of PI3K‐p85 and p‐Akt increased significantly in podocytes in the HG and TGF‐β1 costimulation group (P < 0.01), whereas the BBR high concentration treatment group (60 μmol/L) and LY294002 treatment group could significantly reduce the expression of PI3K and p‐Akt in podocytes (P < 0.01), and the BBR medium concentration treatment group (30 μmol/L) could also reduce the expression of p‐Akt in podocytes (P < 0.05; Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

Effect of berberine (BBR) on the related protein of phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase–protein kinase B (PI3K–Akt) in podocytes stimulated by costimulating factor. (a) Normal control (NC) group; (b) high‐glucose group (HG); (c) HG + transforming growth factor‐β1 (TGF‐β1) group; (d) HG + TGF‐β1 + BBR 15 μmol/L; (e) HG + TGF‐β1 + BBR 30 μmol/L group; (f) HG + TGF‐β1 + BBR 60 μmol/L group; and (g) HG + TGF‐β1 + LY294002 40 μmol/L group. ## P < 0.01 versus NC group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus HG + TGF‐β1 group (mean ± standard deviation, n = 3).

Discussion

Diabetic nephropathy is one of the severe complications of diabetes mellitus. It causes kidney damage, mainly including high glomerular filtration, oxidative stress and proteinuria, leading to progressive renal failure19. Previous studies have found that mesangial matrix proliferation and glomerular basement membrane thickening were closely associated with proteinuria and renal function deterioration, but could not explain the occurrence of proteinuria in a real sense20. Podocytes, attached to the glomerular basement membrane, constitute the glomerular filtration barrier together with the slit diaphragm, which could prevent protein extravasating from the final glomerular filtration barrier21. Several studies have implied that the anomalous expression of nephrin, podocin and integrin α3β1 in podocytes would destroy the cells’ normal structure and adhesive function, causing podocyte loss and apoptosis, which are closely related to the incidence of DN. Once podocyte damage occurs, the normal structure of foot processes is destroyed and the function is disordered, causing further podocyte injury and apoptosis, which are likely to lead to proteinuria, thus further promoting the development of renal functional injury and finally accelerating the DN progression22. In the present study, we found that the injection of STZ combined with a high‐glucose/high‐fat diet could significantly increase the FBG, promoting diabetic progression and further affecting renal function. Different dosages of BBR reduce the FBG level from different stages and have a similar effect to metformin, confirming that BBR might be a promising antidiabetic treatment. BBR could markedly reverse abnormalities of renal function and biochemical parameters, including BUN, SCr and UPCX, as well as improve diabetic status according to hemodynamic indexes and ultrastructural changes in kidneys. A similar role as captopril showed that BBR could be a promising anti‐DN drug as research continues. Meanwhile, compared with model rats, BBR could significantly upregulate the protein expressions of nephrin, podocin and integrin α3β1, the functional markers of podocytes in the kidney, suggesting that the above‐mentioned anti‐DN effects of BBR might be related to its attenuated effect of podocyte dysfunction.

Hyperglycemia is one of the main causes of DN occurrence. Research has found that hyperglycemia could induce oxidative stress, and promote extracellular matrix deposition and advanced glycation end‐products accumulation under the diabetic condition, which could be mutual induction between these risk factors to form a vicious circle, further accelerating the formation process of DN23. TGF‐β1 is one of the key pro‐fibrosis growth factors in renal fibrosis, which plays an important role in the process of DN7. Several studies have shown that TGF‐β1 could significantly induce podocyte injury and apoptosis, but the underlying mechanisms of the relationship among podocytes, TGF‐β1 and proteinuria in the pathogenesis of DN are undefined24. In the meantime, we find that TGF‐β1 could promote the process of liver fibrosis and sclerosis through regulating the PI3K–Akt signaling pathway in hepatic stellate cells of multiple liver diseases by searching for and analyzing the relevant articles. In the area of DN, we are seeing a similar phenomenon that BBR could reduce the renal inflammatory response under the DN state by regulating inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin, TGF‐β and tumor necrosis factor, and the G protein‐coupled receptor‐mediated pathway‐like prostaglandin E receptors–G protein–cyclic adenosine monophosphate signaling pathway from a previous study25. Therefore, the above‐mentioned findings lead us to choose high glucose (30 mmol/L) combined with TGF‐β1 (5 ng/mL) as a costimulating factor to induce podocyte dysfunction. Meanwhile, several concentrations of BBR and the specific PI3K antagonist, LY294002 (40 μmol/L), were added to the cultured cells to explore whether the protective effect of BBR in podocyte dysfunction and injury is related to the PI3K–Akt signaling pathway in DN podocytes after stimulation.

Cell adhesion assay analysis showed that the adhesion ability decreased significantly under the costimulation of high glucose combined with TGF‐β1, which suggested that podocyte dysfunction and injury occurred26. At this moment, different concentrations of BBR (15, 30, 60 and 90 μmol/L) were added to the cultured cells, and the results showing that BBR could enhance the cell adhesion ability obviously seem to indicate that BBR could reverse podocyte dysfunction and injury after 48‐h stimulation. In the meantime, BBR 30 and 60 μmol/L show better resilience than that of BBR 15 and 90 μmol/L (P < 0.05), whereas BBR 15 μmol/L has a similar effect compared with BBR 90 μmol/L (P > 0.05); therefore, BBR 15, 30 and 60 μmol/L were selected to continue the following experiments. When exploring the effect of BBR on the expression of podocyte surface functional proteins, the similar phenomenon appeared once again. Under the costimulation of high glucose and TGF‐β1, the expression levels of these proteins, including nephrin, podocin and adhesion molecule α3β1, decreased markedly compared with the NC group, which reminded us the podocyte dysfunction and injury occurred again. BBR (15, 30 and 60 μmol/L) could increase the expression levels of these surface functional proteins markedly, which proved the mitigative effect of podocyte dysfunction and injury. Part of the experiment result showed that BBR had a similar effect to that of LY294002, the specific PI3K antagonist, providing the first evidence that BBR might exert its mitigative effect through the PI3K–Akt signaling pathway. Western blot analysis showed that in the model group induced by HG and TGF‐β1, the protein level of PI3K‐p85 and p‐Akt decreased, but there were no changes of the total Akt protein compared with the NC group. The levels of PI3K‐p85 and p‐Akt had increased, and the total Akt protein change was indistinguishable with the treatment of BBR (30 and 60 μmol/L). This phenomenon showed that abnormal changes of the PI3K–Akt signaling pathway occurred, and BBR could inhibit the signaling pathway to ameliorate the podocyte injury under such a model environment. Meanwhile, western blot analysis showed that LY294002 had a similar effect with BBR, proving that BBR could ameliorate the podocyte injury through affecting the PI3K–Akt signaling pathway once again.

Based on the present results, it would be reasonable to conclude that the possible mechanism of BBR relieving podocyte damage might be associated with the PI3K–Akt pathway, and the PI3K–Akt signaling pathway in podocyte dysfunction might be an important therapeutic target for DN treatment. BBR will be a promising and meaningful anti‐DN drug with further research.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81803602, 81773955), the Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. 1708085QH207) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. WK9110000018).

J Diabetes Investig 2020; 11: 297–306

References

- 1. Perco P, Mayer G. Molecular, histological, and clinical phenotyping of diabetic nephropathy: valuable complementary information? Kidney Int 2018; 93: 308–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ni WJ, Tang LQ, Zhou H, et al Renoprotective effect of berberine via regulating the PGE2 ‐EP1‐Galphaq‐Ca(2 + ) signalling pathway in glomerular mesangial cells of diabetic rats. J Cell Mol Med 2016; 20: 1491–1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kato M, Natarajan R. Diabetic nephropathy–emerging epigenetic mechanisms. Nat Rev Nephrol 2014; 10: 517–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vallon V, Thomson SC. Targeting renal glucose reabsorption to treat hyperglycaemia: the pleiotropic effects of SGLT2 inhibition. Diabetologia 2017; 60: 215–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ni WJ, Tang LQ, Wei W. Research progress in signalling pathway in diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2015; 31: 221–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carney EF. Diabetic nephropathy: restoring podocyte proteostasis in DN. Nat Rev Nephrol 2017; 13: 514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Voelker J, Berg PH, Sheetz M, et al Anti‐TGF‐beta1 antibody therapy in patients with diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 28: 953–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhang L, Zhou F, Ten DP. Signaling interplay between transforming growth factor‐beta receptor and PI3K/AKT pathways in cancer. Trends Biochem Sci 2013; 38: 612–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kato M, Yuan H, Xu ZG, et al Role of the Akt/FoxO3a pathway in TGF‐beta1‐mediated mesangial cell dysfunction: a novel mechanism related to diabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 17: 3325–3335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hung YP, Teragawa C, Kosaisawe N, et al Akt regulation of glycolysis mediates bioenergetic stability in epithelial cells. Elife 2017; 6: e27293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mendez‐Pertuz M, Martinez P, Blanco‐Aparicio C, et al Modulation of telomere protection by the PI3K/AKT pathway. Nat Commun 2017; 8: 1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ni WJ, Ding HH, Tang LQ. Berberine as a promising anti‐diabetic nephropathy drug: an analysis of its effects and mechanisms. Eur J Pharmacol 2015; 760: 103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chueh WH, Lin JY. Berberine, an isoquinoline alkaloid in herbal plants, protects pancreatic islets and serum lipids in nonobese diabetic mice. J Agric Food Chem 2011; 59: 8021–8027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ni WJ, Ding HH, Zhou H, et al Renoprotective effects of berberine through regulation of the MMPs/TIMPs system in streptozocin‐induced diabetic nephropathy in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2015; 764: 448–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang L, Zhang Q, Liu S, et al DNA methyltransferase 1 may be a therapy target for attenuating diabetic nephropathy and podocyte injury. Kidney Int 2017; 92: 140–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tang LQ, Ni WJ, Cai M, et al Renoprotective effects of berberine and its potential effect on the expression of beta‐arrestins and intercellular adhesion molecule‐1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule‐1 in streptozocin‐diabetic nephropathy rats. J Diabetes 2016; 8: 693–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sanyour H, Childs J, Meininger GA, et al Spontaneous oscillation in cell adhesion and stiffness measured using atomic force microscopy. Sci Rep 2018; 8: 2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ding HH, Qiu YY, Wang YY, et al. Effect of berberine on the expression of nephrin, podocin and intergrin α3β1 in diabetic nephropathy rats. Chin Pharmacol Bull 2015; 31: 1414–1420. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Reddy MA, Zhang E, Natarajan R. Epigenetic mechanisms in diabetic complications and metabolic memory. Diabetologia 2015; 58: 443–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ding HH, Ni WJ, Tang LQ, et al G protein‐coupled receptors: potential therapeutic targets for diabetic nephropathy. J Recept Signal Transduct Res 2015; 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Miner JH. Podocyte biology in 2015: new insights into the mechanisms of podocyte health. Nat Rev Nephrol 2016; 12: 63–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu M, Liang K, Zhen J, et al Sirt6 deficiency exacerbates podocyte injury and proteinuria through targeting Notch signaling. Nat Commun 2017; 8: 413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Coughlan MT, Sharma K. Challenging the dogma of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species overproduction in diabetic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2016; 90: 272–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yu L, Lin Q, Liao H, et al TGF‐beta1 induces podocyte injury through Smad3‐ERK‐NF‐kappaB pathway and Fyn‐dependent TRPC6 phosphorylation. Cell Physiol Biochem 2010; 26: 869–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yang Y, Ni W, Cai M, et al. The renoprotective effects of berberine via the EP4‐Galphas‐cAMP signaling pathway in different stages of diabetes in rats. J Recept Signal Transduct Res 2014; 34: 445–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Muller‐Deile J, Dannenberg J, Schroder P, et al Podocytes regulate the glomerular basement membrane protein nephronectin by means of miR‐378a‐3p in glomerular diseases. Kidney Int 2017; 92: 836–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]