Abstract

Background

Pre-operative treatment planning in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is mainly dictated by clinical staging, which has major shortcomings. Histologic grading is irrelevant due to its lack of prognostic impact. Recently, a novel grading termed Cellular Dissociation Grade (CDG) based on Tumour Budding and Cell Nest Size was shown to be highly prognostic for resected HNSCC. We aimed to probe the predictive and prognostic impact of CDG in the pre-operative biopsies of HNSCC.

Methods

We evaluated CDG in n = 160 pre-therapeutic biopsies from patients who received standardised treatment following German guidelines, and correlated the results with pre- and post-therapeutic staging data and clinical outcome.

Results

Pre-operative CDG was highly predictive of post-operative tumour stage, including the prediction of occult lymph node metastasis. Uni- and multivariate analysis revealed CDG to be an independent prognosticator of overall, disease-specific and disease-free survival (p < 0.001). Hazard ratio for disease-specific survival was 6.1 (11.1) for nG2 (nG3) compared with nG1 tumours.

Conclusions

CDG is a strong outcome predictor in the pre-treatment scenario of HNSCC and identifies patients with nodal-negative disease. CDG is a purely histology-based prognosticator in the pre-therapeutic setting that supplements clinical staging and may aide therapeutic stratification of HNSCC patients.

Subject terms: Head and neck cancer, Tumour biomarkers

Background

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is one of the most common cancers worldwide with ~500.000 new cases annually.1 HNSCC arise in different anatomical areas of the head and neck region. Human Papilloma Virus (HPV)— negative cases are particularly located within the oral cavity, hypopharynx and larynx.2,3 Overall, the prognosis of HNSCC, especially of HPV-negative cases, is unfavourable with a 5-year survival of patients on average below 50%.4,5 To date, tumour stage according to clinical and pathological TNM and UICC classification provides the most important prognostic information for patient outcome.3–5 However, pre-operative clinical assessment of tumour size (cT stage) and nodal involvement (cN stage) is discordant from pathological pT- and pN stage in nearly half of cases.6 Estimates assume that in early-stage oral squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) without clinically or radiologically apparent nodal metastasis 20–40% of patients contain occult metastasis at the time of diagnosis.7–9 As accurate routine biomarkers besides clinical staging for detection of such occult metastasis are still lacking, it is a matter of an ongoing debate which patients could be treated adequately and sufficiently without neck dissection in order to avoid overtreatment and in which patients to perform neck dissection in order to detect clinically non-apparent nodal metastasis and therewith improve prognosis.10–12

Currently, histopathologic grading does not play a major role in clinical decision making as current histopathological grading schemes according to the World Health Organization (WHO) possess major shortcomings regarding prognostic patient stratification and reproducibility.13–17 In an effort to resolve this issue, our group recently proposed a new histopathological grading scheme termed Cellular Dissociation Grade (CDG) for oral, hypopharyngeal and laryngeal SCC, which is based on the parameters Tumour Budding and Cell Nest Size. These parameters describe the extent of Cellular Dissociation of a given cancer, both from a quantitative (Tumour Budding) and qualitative (Cell Nest Size) angle. CDG has not only been shown to be highly prognostic in other squamous cell carcinomas entities like oesophageal or cervical SCC but was also recently demonstrated to work nicely on pre-therapeutic biopsies of oesophageal SCC.

Biopsies are the mainstay of pre-operative diagnostics in many cancer types, including HNSCC. Pre-therapeutic biopsies are not only necessary to establish a diagnosis but offer the possibility to determine histological subtypes, differentiation and potential further prognostic/predictive information to identify biologically aggressive tumours or to predict treatment response. Therewith, histopathological grading in biopsy specimen guides choice of therapies, including e.g., neoadjuvant systemic treatment versus primary resection or watchful waiting strategies in entities as endometrial cancer and prostate cancer.18,19 However, up to date, pre-operative grading in HNSCC is almost meaningless as conventional grading according to the WHO is neither correlated with post-operative tumour stage nor with patient outcome,13–17 and is also known to be highly discordant when biopsies and corresponding resection specimen are compared.20,21

Based on the above said, major questions remain. Can the high prognostic value of CDG be transferred to small biopsy specimens in HNSCC without losing its prognostic impact concerning patient survival? Can CDG potentially serve as a biomarker for prediction of occult metastasis in cN0 necks in clinically early-stage HNSCC? How is the concordance of CDG when biopsies and corresponding resection specimens are compared? Aiming to answer these questions, we investigated Tumour Budding and Cell Nest Size and CDG derived from these factors in pre-operative biopsies and resection specimen of n = 160 patients with HNSCC located in the oral cavity, larynx and hypopharynx. We analysed concordance of CDG between biopsy and resection specimens and correlated CDG with pre-operative clinical staging (cT, cN), post-operative pathological staging (pT, pN) and with patient outcome (overall (OS), disease-specific (DSS) and disease-free survival (DFS)).

Methods

Patient cohort

Included in our study were 160 patients with HNSCC of the larynx (supraglottic, glottic, infraglottic primaries), the hypopharynx and the oral cavity from whom pre-operative biopsies and resection specimen were prospectively collected. All patients were treated in curative intent between 2004 and 2015 at Klinikum Rechts der Isar of the Technical University of Munich, Germany. All patients received a complete surgical resection of their primary tumours followed by a neck dissection in combination with radiotherapy (65–70 Gy) or radio-chemotherapy if indicated (pT4 tumours and/or nodal stage pN1 and pN2a/b) according to German guidelines. Exclusion criteria were distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis (cM1 stage), neoadjuvant treatment with radio- and/or chemotherapy and pathological diagnosis upon fresh-frozen tissue sections. Male patients (129/160 (80.6%)) were in the majority compared with female counterparts (31/160 (19.4%)). Mean age at diagnosis was 60.6 years (range: 40.0–87.0 years). Mean follow-up time of patients alive at the endpoint of analysis was 53.5 months, mean survival time of deceased patients 26.9 months. During follow-up, 70/160 (43.8%) of patients died and 65/160 (40.6%) suffered from (local, nodal and/or distant) relapse. Pre-operative clinical staging was performed by clinical examination, ultrasound and/or CT-scan according to the German guidelines.22 Clinical and pathological T-stage, N-stage and UICC stage, which were available for 100/160 (62.5%), were documented according to the TNM classification of malignant tumours.23 Distribution of clinicopathological parameters is given in Tables 1 and 2. Approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee of the Technical University of Munich (296/17s).

Table 1.

Distribution and survival associations for clinicopathological data, histomorphological parameters and Cellular Dissociation Grade in biopsies and resection specimens.

| Overall | Events (OS) | Mean overall survival (SE) | p-value | Events (DSS) | Mean disease-specific survival (SE) | p-value | Events (DFS) | Mean disease-free survival (SE) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 160 | 70 | 77.3 (5.4) | 55 | 87.5 (5.7) | 65 | 78.7 (5.3) | |||

| Age | ||||||||||

| Median and below | 80 | 28 | 83.9 (7.1) | 0.039 | 22 | 91.0 (7.4) | 0.073 | 29 | 82.1 (6.8) | 0.211 |

| Above median | 80 | 42 | 66.6 (7.1) | 33 | 79.0 (7.8) | 36 | 73.5 (7.4) | |||

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 129 | 59 | 7e.9 (5.7) | 0.301 | 45 | 85.3 (6.1) | 0.663 | 52 | 78.2 (5.9) | 0.870 |

| Female | 31 | 11 | 86.1 (12.8) | 10 | 94.2 (12.1) | 13 | 79.5 (12.2) | |||

| Localisation | ||||||||||

| Infraglottic | 11 | 5 | 57.3 (10.5) | 0.554 | 3 | 68.8 (10.5) | 0.326 | 7 | 55.1 (10.7) | 0.334 |

| Glottic | 36 | 13 | 86.4 (9.2) | 9 | 98.3 (9.1) | 11 | 93.1 (9.1) | |||

| Supraglottic | 12 | 5 | 89.4 (17.3) | 4 | 96.6 (17.3) | 6 | 88.5 (17.1) | |||

| Hypopharyngeal | 41 | 21 | 61.6 (7.6) | 19 | 65.2 (7.8) | 18 | 68.1 (7.6) | |||

| Oral | 60 | 26 | 59.2 (5.3) | 20 | 66.2 (5.3) | 23 | 58.8 (5.9) | |||

| Histotype | ||||||||||

| Keratinising | 126 | 52 | 80.4 (6.2) | 0.686 | 41 | 91.2 (6.3) | 0.821 | 46 | 82.6 (6.2) | 0.372 |

| Non-keratinising | 30 | 16 | 57.7 (7.8) | 12 | 65.5 (8.6) | 16 | 56.7 (7.6) | |||

| Basaloid | 4 | 2 | 83.0 (26.6) | 2 | 83.0 (26.6) | 3 | 76.5 (37.2) | |||

| cT | ||||||||||

| 1 | 16 | 3 | 72.4 (5.0) | 0.010 | 2 | 73.3 (5.0) | 0.008 | 6 | 61.2 (5.8) | 0.045 |

| 2 | 32 | 7 | 82.8 (7.7) | 4 | 91.2 (7.2) | 6 | 83.9 (7.8) | |||

| 3 | 23 | 10 | 58.4 (9.3) | 9 | 61.3 (9.4) | 12 | 52.7 (8.7) | |||

| 4a/b | 29 | 17 | 55.2 (8.3) | 13 | 63.9 (8.9) | 14 | 63.9 (9.2) | |||

| cN | ||||||||||

| 0 | 40 | 10 | 81.2 (7.1) | 0.066 | 7 | 89.4 (6.5) | 0.023 | 12 | 78.7 (7.0) | 0.029 |

| 1 | 15 | 6 | 65.9 (9.7) | 3 | 79.8 (8.7) | 5 | 68.8 (9.7) | |||

| 2 | 43 | 19 | 60.0 (6.6) | 16 | 65.0 (6.6) | 19 | 57.4 (6.9) | |||

| 3 | 2 | 2 | 26.0 (5.0) | 2 | 26.0 (5.0) | 2 | 26.0 (5.0) | |||

| Pre-operative UICC stage | ||||||||||

| 1 | 11 | 1 | 80.0 (0.7) | 0.031 | 0 | Cases censored | 0.021 | 4 | 64.1 (5.7) | 0.040 |

| 2 | 15 | 3 | 86.6 (9.8) | 2 | 91.4 (9.4) | 1 | 98.6 (7.5) | |||

| 3 | 21 | 7 | 62.5 (8.0) | 5 | 68.5 (7.8) | 8 | 62.6 (8.1) | |||

| 4 | 53 | 26 | 61.3 (6.6) | 21 | 68.5 (6.7) | 25 | 61.7 (7.1) | |||

| pT | ||||||||||

| 1 | 37 | 8 | 101.5 (11.9) | 0.002 | 4 | 124.2 (7.4) | 0.001 | 10 | 98.2 (10.5) | 0.051 |

| 2 | 52 | 23 | 78.8 (8.5) | 20 | 84.1 (8.8) | 22 | 80.6 (8.9) | |||

| 3 | 32 | 15 | 62.6 (8.2) | 11 | 73.2 (8.5) | 14 | 67.9 (8.7) | |||

| 4a/b | 39 | 24 | 49.4 (7.2) | 20 | 55.8 (7.7) | 19 | 54.9 (7.7) | |||

| pN | ||||||||||

| 0 | 73 | 19 | 5.8 (6.9) | <0.001 | 11 | 110.1 (6.2) | <0.001 | 23 | 86.7 (6.8) | 0.016 |

| 1 | 26 | 15 | 65.0 (11.1) | 12 | 73.9 (12.4) | 11 | 76.3 (13.2) | |||

| 2 | 60 | 36 | 57.6 (8.3) | 32 | 62.9 (8.9) | 31 | 68.2 (8.6) | |||

| 3 | 1 | 0 | Cases censored | 0 | Cases censored | 0 | Cases censored | |||

| Post-operative UICC stage | ||||||||||

| 1 | 28 | 5 | 90.3 (12.1) | <0.001 | 1 | 118.6 (4.3) | <0.001 | 6 | 91.4 (10.3) | 0.010 |

| 2 | 16 | 1 | 123.9 (7.7) | 0 | Cases censored | 5 | 94.8 (12.0) | |||

| 3 | 36 | 17 | 77.0 (10.2) | 13 | 87.3 (10.8) | 14 | 84.6 (10.8) | |||

| 4 | 80 | 47 | 58.5 (6.9) | 41 | 64.2 (7.4) | 40 | 66.1 (7.6) | |||

| Biopsy specimen | ||||||||||

| Budding/HPF | ||||||||||

| No budding | 34 | 7 | 99.6 (7.6) | <0.001 | 2 | 115.5 (5.1) | <0.001 | 4 | 108.9 (6.3) | <0.001 |

| Low budding activity | 88 | 38 | 73.5 (7.7) | 30 | 82.8 (8.4) | 40 | 69.6 (7.0) | |||

| High budding activity | 38 | 25 | 50.7 (7.7) | 23 | 53.3 (7.9) | 21 | 53.5 (7.9) | |||

| Cell nest size | ||||||||||

| Large cell nests | 16 | 4 | 89.7 (12.8) | 0.004 | 1 | 111.9 (10.3) | <0.001 | 2 | 102.4 (12.2) | 0.001 |

| Intermediate cell nests | 18 | 3 | 97.9 (8.4) | 1 | 108.3 (5.5) | 2 | 106.7 (5.6) | |||

| Small cell nests | 55 | 24 | 76.7 (9.6) | 19 | 86.8 (10.3) | 26 | 66.7 (8.4) | |||

| Single-cell invasion | 71 | 39 | 59.2 (7.2) | 34 | 64.8 (7.8) | 35 | 69.2 (8.0) | |||

| Sum score | ||||||||||

| 2 | 17 | 4 | 90.1 (12.8) | 0.001 | 1 | 111.9 (10.3) | <0.001 | 2 | 102.4 (12.2) | 0.001 |

| 3 | 17 | 3 | 97.6 (8.6) | 1 | 107.9 (5.9) | 2 | 106.4 (5.9) | |||

| 5 | 52 | 23 | 76.3 (9.8) | 19 | 84.7 (10.3) | 25 | 66.7 (8.6) | |||

| 6 | 37 | 15 | 70.7 (11.3) | 11 | 81.7 (12,8) | 16 | 73.6 (11.6) | |||

| 7 | 37 | 25 | 48.8 (7.7) | 23 | 51.4 (8.0) | 20 | 55.0 (8.1) | |||

| Cellular dissociation grade | ||||||||||

| nG1 | 34 | 7 | 99.6 (7.6) | <0.001 | 2 | 115.5 (5.4) | <0.001 | 4 | 108.9 (6.3) | <0.001 |

| nG2 | 89 | 38 | 74.0 (7.7) | 30 | 83.3 (8.4) | 41 | 69.0 (6.9) | |||

| nG3 | 37 | 25 | 48.8 (7.7) | 23 | 51.4 (.0) | 20 | 55.0 (8.1) | |||

| Resection specimen | ||||||||||

| Budding/10 HPF | ||||||||||

| No budding | 31 | 6 | 101.2 (7.8) | <0.001 | 1 | 119.5 (3.5) | <0.001 | 3 | 112.5 (5.4) | <0.001 |

| Low budding activity | 85 | 35 | 76.6 (8.2) | 27 | 87.0 (9.0) | 36 | 72.3 (7.6) | |||

| High budding activity | 44 | 29 | 49.1 (7.0) | 27 | 51.2 (7.2) | 26 | 51.3 (6.9) | |||

| Cell nest size | ||||||||||

| Large cell nests | 6 | 1 | 67.0 (7.8) | 0.001 | 0 | Cases censored | <0.001 | 1 | 72.0 (2.8) | <0.001 |

| Intermediate cell nests | 26 | 5 | 102.9 (8.0) | 1 | 118.9 (4.0) | 2 | 115.6 (4.8) | |||

| Small cell nests | 45 | 16 | 82.2 (11.3) | 13 | 93.4 (10.9) | 19 | 73.9 (10.3) | |||

| Single-cell invasion | 83 | 48 | 54.2 (5.4) | 41 | 59.4 (5.9) | 43 | 56.2 (5.2) | |||

| Sum score | ||||||||||

| 2 | 6 | 1 | 67.0 (8.0) | 0.001 | 0 | Cases censored | <0.001 | 1 | 72.0 (2.8) | <0.001 |

| 3 | 25 | 5 | 101.3 (8.6) | 1 | 118.6 (4.3) | 2 | 115.2 (5.1) | |||

| 5 | 45 | 16 | 84.1 (11.0) | 13 | 94.5 (10.8) | 18 | 78.0 (10.4) | |||

| 6 | 41 | 19 | 52.0 (4.4) | 14 | 57.4 (4.5) | 19 | 51.7 (4.2) | |||

| 7 | 43 | 29 | 48.1 (7.0) | 27 | 50.3 (7.2) | 25 | 51.9 (7.1) | |||

| Cellular dissociation grade | ||||||||||

| nG1 | 31 | 6 | 101.2 (7.8) | <0.001 | 1 | 119.5 (3.5) | <0.001 | 3 | 112.5 (5.4) | <0.001 |

| nG2 | 86 | 35 | 77.0 (8.3) | 27 | 87.4 (9.0) | 37 | 71.8 (7.5) | |||

| nG3 | 43 | 29 | 48.1 (7.0) | 27 | 50.3 (7.2) | 25 | 51.9 (7.1) | |||

The values given in italics are the p-values obtained in statistical analysis for the respective correlation

Table 2.

Correlation of histomorphological parameters and cellular dissociation grade with clinicopathological data.

| Cell Nest Size | Budding activity | Grading | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large | Intermediate | Small | Single-cell invasion | p-value | Absent | Low | High | p-value | nG1 | nG2 | nG3 | p-value | |

| Age | |||||||||||||

| Median and below | 6 | 11 | 28 | 35 | 0.589 | 17 | 43 | 20 | 0.927 | 17 | 44 | 19 | 0.981 |

| Above median | 10 | 7 | 27 | 36 | 17 | 45 | 18 | 17 | 45 | 18 | |||

| Gender | |||||||||||||

| Male | 13 | 18 | 41 | 57 | 0.131 | 31 | 66 | 32 | 0.104 | 31 | 67 | 31 | 0.117 |

| Female | 3 | 0 | 14 | 14 | 3 | 22 | 6 | 3 | 22 | 6 | |||

| cT stage | |||||||||||||

| 1 | 3 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 0.017 | 4 | 11 | 1 | 0.059 | 4 | 11 | 1 | 0.100 |

| 2 | 3 | 5 | 12 | 12 | 8 | 21 | 3 | 8 | 21 | 3 | |||

| 3 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 12 | 5 | 9 | 9 | 5 | 10 | 8 | |||

| 4a/b | 1 | 3 | 6 | 19 | 4 | 15 | 10 | 4 | 15 | 10 | |||

| cN stage | |||||||||||||

| 0 | 4 | 6 | 18 | 12 | 0.010 | 10 | 23 | 7 | 0.447 | 10 | 23 | 7 | 0.404 |

| 1 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 2 | |||

| 2 | 5 | 1 | 9 | 28 | 6 | 24 | 13 | 6 | 24 | 13 | |||

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |||

| Pre-therapeutic UICC stage | |||||||||||||

| I | 2 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0.073 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 0.142 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 0.231 |

| II | 1 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 10 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 1 | |||

| II | 2 | 3 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 9 | 7 | |||

| Iva/b | 5 | 4 | 14 | 30 | 9 | 30 | 14 | 9 | 30 | 14 | |||

| pT stage | |||||||||||||

| 1 | 7 | 4 | 19 | 7 | 0.001 | 11 | 23 | 3 | 0.002 | 11 | 23 | 3 | 0.002 |

| 2 | 2 | 8 | 18 | 24 | 10 | 32 | 10 | 10 | 33 | 9 | |||

| 3 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 19 | 10 | 9 | 13 | 10 | 9 | 13 | |||

| 4a/b | 1 | 2 | 15 | 21 | 3 | 24 | 12 | 3 | 24 | 12 | |||

| pN stage | |||||||||||||

| 0 | 12 | 12 | 31 | 18 | <0.001 | 24 | 39 | 10 | 0.001 | 24 | 39 | 10 | 0.001 |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 13 | 4 | 16 | 6 | 4 | 17 | 5 | |||

| 2 | 2 | 4 | 14 | 40 | 6 | 32 | 22 | 6 | 32 | 22 | |||

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Post-therapeutic UICC stage | |||||||||||||

| I | 7 | 3 | 15 | 3 | 0.001 | 10 | 16 | 2 | 0.003 | 10 | 16 | 2 | 0.005 |

| II | 1 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 11 | 0 | 5 | 11 | 0 | |||

| II | 5 | 5 | 9 | 17 | 10 | 15 | 11 | 10 | 16 | 10 | |||

| Iva/b | 3 | 6 | 26 | 45 | 9 | 46 | 25 | 9 | 46 | 25 | |||

| Recurrence | |||||||||||||

| No recurrence | 14 | 16 | 28 | 36 | 0.248 | 30 | 47 | 17 | 0.321 | 30 | 47 | 17 | 0.394 |

| Local recurrence | 1 | 2 | 11 | 8 | 3 | 14 | 5 | 3 | 14 | 5 | |||

| Nodale recurrence | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | |||

| Distant recurrence | 1 | 0 | 4 | 15 | 1 | 11 | 8 | 1 | 11 | 8 | |||

| Combined recurrence | 0 | 0 | 6 | 9 | 0 | 8 | 7 | 0 | 9 | 6 | |||

| Recurrence; localisation unclear | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | |||

The values given in italics are the p-values obtained in statistical analysis for the respective correlations

Histopathological evaluation

Biopsy and resection specimen from all 160 patients were available. Full block haematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained slides of biopsy specimen were evaluated simultaneously by experienced pathologists (MB., MJ.) blinded to clinicopathological data and follow-up using an Olympus BX43 microscope with a field diameter of 0.55 mm (0.24 mm²). Resection specimen had previously been evaluated in the context of two recently published studies.17,24 In case of discordance between biopsy and resection specimen, both biopsy and resection specimen were comparatively re-evaluated. HNSCC were categorised according to the current WHO classification criteria of tumours of head and neck into non-keratinising, keratinising and basaloid.3

Tumour Budding and Cell Nest Size and subsequent CDG were evaluated as described before in detail.17,24,25 In short, Tumour Budding was defined as “branching” of small tumour nests harbouring <5 tumour cells into the stroma/parenchyma,17,26,27 and was assessed in one high-power-field (HPF) in biopsies and in ten (continuous) HPFs in resection specimen in areas showing maximal budding activity. The slight modification of the evaluated tumour area (one HPF in biopsies versus ten HPFs in resection specimen) was necessary due to the limited tissue availability in biopsy samples. Low budding activity was defined as 1–4 buds in one HPF (biopsies) and as 1–14 budding nests in ten HPFs (resections), high budding activity was defined as ≥5 in one HPF (biopsies) and as ≥15 budding nests in ten HPFs (resections). Overall Cell Nest Size, a parameter additionally measuring the dissociative growth capability of an individual tumour from a qualitative point of view, was evaluated in tumour area containing smallest tumour cell nests. Tumour cell nests, defined as clustered tumour cells surrounded by tumour stroma, were classified according the size of the smallest invasive cell nest as follows: > 15 tumour cells = large nests, 5–15 tumour cells = intermediate nests, 2–4 tumour cells = small nests, discohesive tumour cells without nested architecture = single-cell invasion. The criteria for budding activity and cell nest size evaluation applied were similar to already established algorithms for the evaluation of CDG in biopsies and resection specimen. According to our previously proposed grading system,17,24,25 scores for budding activity (1 = no budding activity; 2 = low budding activity; 3 = high budding activity) and cell nest size (1 = large cell nests; 2 = intermediate cell nests; 3 = small cell nests; 4 = single-cell invasion) were assigned in order to obtain the CDG. After summarising both scores into a sum score from 2 to 7, HNSCC were graded into well cohesive (CDG nG1; sum scores 2, 3), moderately cohesive (CDG nG2; sum scores 4–6) and poorly cohesive (CDG nG3; sum score 7) according to the CDG.

Statistics

Associations of grouped morphological characteristics with clinicopathological parameters were calculated with Χ2 test as well as Χ2 test for trends and Fisher’s exact test. Cohen’s kappa was used to assess concordance between clinical and pathological staging parameters as well as to assess concordance between histopathological parameters in biopsies and resection specimen. Survival probabilities were plotted with the Kaplan–Meier method, a log-rank test was used to probe for the significance of differences in survival. Multivariate survival analysis was performed with the Cox proportional hazard model. P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant. All statistical tests were performed two-sided, and a significance level of 5% was used.

Results

Tumour Budding and Cell Nest Size in pre-therapeutic biopsy specimens

The majority of HNSCC were keratinising tumours (126/160, 78.8%), whereas non-keratinising cancers (30/160, 18.8%) and basaloid cancers (4/160; 2.4%) were less frequent. No tumour budding activity (per HPF) was detected in 34/160 (21.3%), while low budding activity was observed in 88/160 (55.0%) of cases and high budding activity in 38/160 (23.7%) of cases. Analysis of the Cell Nest Size revealed large cell nests in 16/160 cases (10.0%), intermediate nests in 18/160 cases (11.3%) and small cell nests in 55/160 cases (34.3%). In total, 71/160 cases (44.4%) showed infiltrative singular tumour cells, and were therefore classified as single-cell invasion. Addition of scores obtained for budding activity (scores 1–3) and cell nest size (scores 1–4) resulted in a sum scores 2–7 for each case, which was assigned to the final CDG (nG1, nG2, nG3) as described in the Methods section. While 34/160 (21.3%) HNSCC were well differentiated (nG1), 89/160 (55.6%) were moderately differentiated (nG2) and 37/160 (23.1%) poorly differentiated (nG3; Table 1; Fig. 1) according to the CDG.

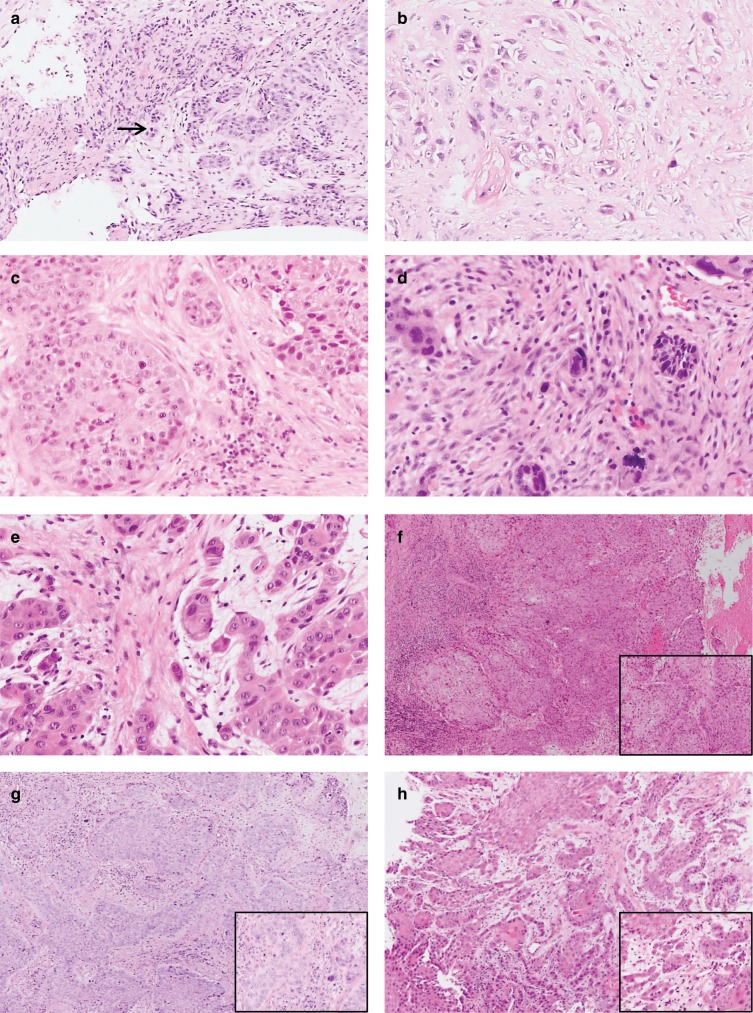

Fig. 1. Representative H&E stained biopsy specimen of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC).

a depicts a HNSCC with low Tumour Budding as indicated by presence of <5 cell nests containing <5 tumour cells within one HPF (→ highlighting the two tumour buds), b depicts a HNSCC with high Tumour Budding as indicated by presence of ≥5 cell nests containing <5 tumour cells within one HPF (→ highlighting some of the numerous tumour buds of this carcinoma). c–e depict different Cell Nest Sizes with C showing large (*) and intermediate (→) cell nest sizes, while d + e show carcinomas with small cell nests (*) and single-cell invasion (→). f–h Overview over representative HNSCC biopsies with f showing Cellular Dissociation Grade nG1 carcinoma (no Tumour Budding, large Cell Nest Size), g showing a Cellular Dissociation Grade nG2 carcinoma (low Tumour Budding, small Cell Nest Size) and h showing a Cellular Dissociation Grade nG3 carcinoma (high Tumour Budding, single-cell invasion). Inserts showing the HPF[×40] of the respective cases with the highest Tumour Budding activity and the smallest Cell Nest Size within the biopsy specimen.

Concordance of the Cellular Dissociation Grade between pre-therapeutic biopsies and resection specimens

The resection specimen of this cohort have previously been evaluated in two studies applying a similar grading algorithm.17,24 Comparison of Tumour Budding in the corresponding biopsies and resection specimen revealed a high concordance with similar scores obtained in 147/160 (91.9%) cases. The corresponding Kappa value was κ = 0.87. Concerning Cell Nest Size, concordance rate was considerably lower with 102/160 (63.8%) HNSCC showing the same cell nest size in biopsy and resection specimen (Kappa value κ = 0.44). Analysis of concordance rate between assigned grades resulted in 147/160 (93.1%) HNSCC with identical histopathological grade (Kappa value κ = 0.89). Of the 13 cases with discordant grading, which was confirmed upon re-evaluation of biopsy and resection specimen, 12 showed an upgrading whereas only one case was downgraded from nG2 to nG1 (Supplementary Table 1). Upgrading was observed in the setting of very small tumour-containing biopsy specimen (<0.3 cm). Downgrading was detected in a large biopsy specimen of a pT1 carcinoma, which contained a majority of the whole tumour leaving only small remnants of the invasive tumour within the resection specimen.

Correlation of Tumour Budding, Cell Nest Size and Cellular Dissociation Grade in biopsies with pre-operative staging

Cell nest size was significantly correlated with cT (p = 0.017) and cN (p = 0.010) stage with single-cell invasion being more frequently detected in HNSCC patients with higher clinical stages. No further significant correlation of either budding activity or overall grading with clinical staging parameters were observed (Table 2).

Correlation of Tumour Budding, Cell Nest Size and Cellular Dissociation Grade in biopsies with post-operative staging

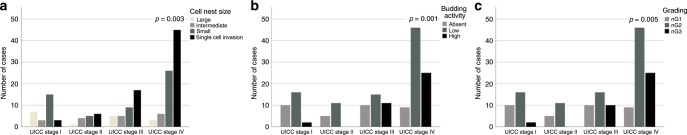

Cell Nest Size and Tumour Budding as well CDG were significantly correlated with post-operative pathological staging parameters pT stage, pN stage and UICC stage. Presence of small cell nest sizes and single-cell invasion as well as presence of budding activity were more frequently detected in cases with higher pT, pN and UICC stage (p < 0.005). This was mirrored by correlation of moderate (nG2) and poor (nG3) differentiation with higher post-operative stages (p < 0.01; Table 2, Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Associations of UICC stage with histomorphological parameters and Cellular Dissociation Grade.

Association between UICC tumour stage with Cell Nest Size (a), Tumour Budding (b) and Cellular Dissociation Grading (c).

Concordance of pre-therapeutic and post-therapeutic staging parameters

Clinical cT and post-operative pT stage was discordant in 36/100 (36.0%) HNSCC (Kappa value κ = 0.52). In total, 14 cases received an upstaging and 22 a downstaging after pathological evaluation of the resection specimen. Respective values for nodal stage and UICC stage were as follows: discordance rate cN vs. pN 32/100 (32.0%; κ = 0.49); pre-operative UICC vs. post-operative UICC 33/100 (33.0%; κ = 0.49). Upstaging: nodal stage 12 cases; UICC stage 14 cases. Downstaging: nodal stage 20 cases; UICC stage 19 cases (Supplementary Table 2).

Subgroup analysis of HNSCC with clinically nodal-negative (cN0) necks: correlation of Cellular Dissociation Grade in biopsies with post-operative staging parameters

HNSCC patients with nodal-negative cervical lymph nodes upon clinical staging procedures (cN0 necks; n = 40) showed occult metastases detected by pathological evaluation of neck dissection specimen in 8/40 (20.0%) cases. Histopathological grading of all of these cases was nG2/3, whereas in none of the nG1 cases presence of lymph node metastases was observed. This result indicated a positive predictive value PPV = 100% for nG1 grading to predict nodal negativity upon pathological work-up in cN0 necks. Association of grading with post-operative nodal stage is summarised in Supplementary Table 3.

Correlation of Tumour Budding, Cell Nest Size and Cellular Dissociation Grade in biopsies with patient survival

Tumour budding activity was strongly associated with decreased OS, DSS and DFS (p < 0.001, respectively) with HNSCC with high budding activity revealing the shortest mean OS. In analogy, Cell Nest Size was strongly correlated with OS, DSS and DFS (p < 0.01, respectively). Cases with single-cell invasion and small cell nests suffered from earlier deaths and tumour recurrences compared with their counterparts (Table 1; Supplementary Fig. 1). Not only both morphologic patterns but also the obtained sum score was significantly correlated with survival parameters of patients (p < 0.005; Table 1).

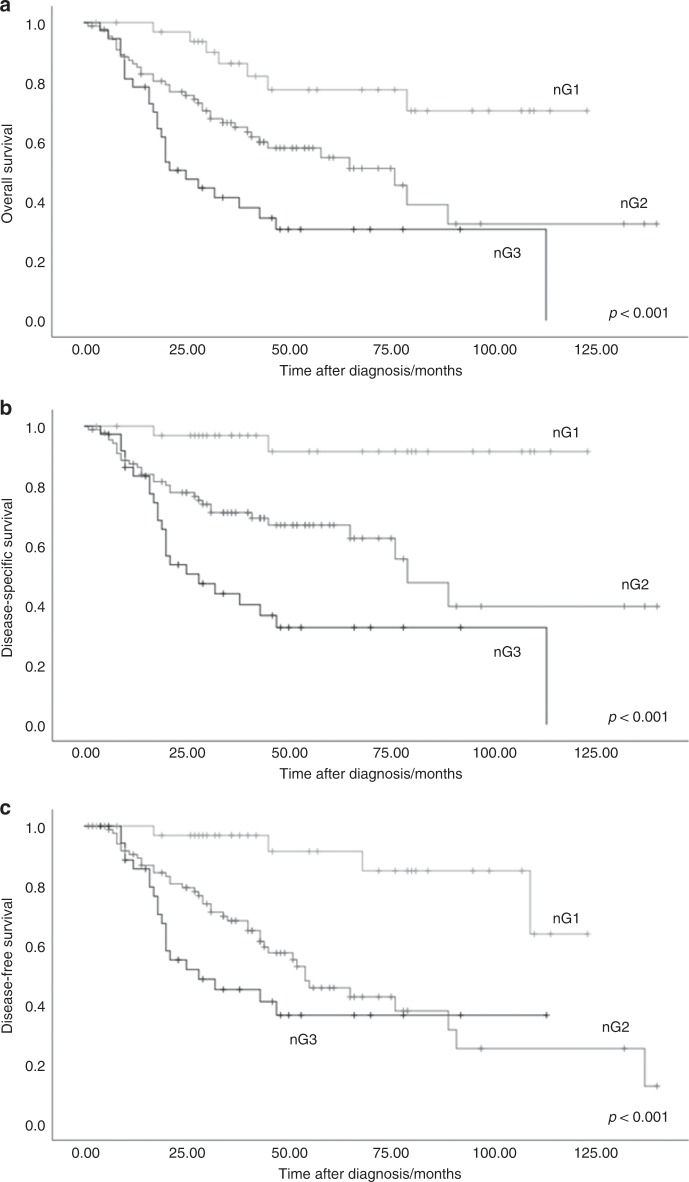

Consequently, the CDG on pre-therapeutic biopsies which is based on the sum scores also showed a highly significant impact on OS, DSS and DFS (p < 0.001, respectively) (Table 1, Fig. 3). While mean DSS of nG1 tumours was 119.5 months, it dropped to 87.4 months for nG2 HNSCC and to 50.3 months for nG3 HNSCC (Table 1).

Fig. 3. Association of Cellular Dissociation Grade with survival.

a Overall survival, b disease-specific survival, c disease-specific survival.

In order to prove that the prognostic impact of the novel grading system derived from biopsy specimens is independent from clinicopathological data and tumour staging, we performed a multivariate analysis by applying a cox regression model incorporating pre-operative, respectively, post-operative staging parameters (cUICC/pUICC), gender and age and the CDG. Multivariate analysis confirmed the independent prognostic value of the novel grading concerning patient survival (OS, DSS, DFS; Table 3 for cox regression with pUICC; Supplementary Table 4 for cox regression with cUICC). Hazard ratio for DSS was 6.1 (95% confidence interval 1.4–26.4) for nG2 and 11.1 (95% confidence interval 2.6–48.0) for nG3 HNSCC compared to nG1 cases (p = 0.002; multivariate analysis including pUICC).

Table 3.

Multivariate survival analysis including Cellular Dissociation Grade, age, gender and post-operative UICC stage.

| Hazard ratio | Confidence interval | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | Low | High | ||

| Overall survival | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1.000 | 0.160 | ||

| Female | 0.625 | 0.325 | 1.204 | |

| Age | ||||

| Median and below | 1.000 | 0.022 | ||

| Above median | 1.764 | 1.087 | 2.880 | |

| UICC stage | ||||

| I | 1.000 | 0.008 | ||

| II | 0.298 | 0.034 | 2.574 | |

| III | 2.043 | 0.740 | 5.644 | |

| Iva/b | 3.194 | 1.250 | 8.164 | |

| Cellular Dissociation Grade | ||||

| nG1 | 1.000 | 0.004 | ||

| nG2 | 2.500 | 1.078 | 5.797 | |

| nG3 | 4.222 | 1.771 | 10.065 | |

| Disease-specific survival | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1.000 | 0.417 | ||

| Female | 0.750 | 0.375 | 1.502 | |

| Age | ||||

| Median and below | 1.000 | 0.054 | ||

| Above median | 1.717 | 0.991 | 2.973 | |

| UICC stage | ||||

| I | 1.000 | 0.046 | ||

| II | <0.001 | <0.001 | >100.0 | |

| III | 7.462 | 0.962 | 57.875 | |

| Iva/b | 12.382 | 1.690 | 90.713 | |

| Cellular Dissociation Grade | ||||

| nG1 | 1.000 | 0.002 | ||

| nG2 | 6.131 | 1.426 | 26.361 | |

| nG3 | 11.095 | 2.565 | 47.999 | |

| Disease-free survival | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1.000 | 0.486 | ||

| Female | 0.802 | 0.431 | 1.492 | |

| Age | ||||

| Median and below | 1.000 | 0.130 | ||

| Above median | 1.478 | 0.892 | 2.451 | |

| UICC stage | ||||

| I | 1.000 | 0.136 | ||

| II | 1.123 | 0.336 | 3.751 | |

| III | 1.452 | 0.543 | 3.883 | |

| Iva/b | 2.245 | 0.939 | 5.364 | |

| Cellular Dissociation Grade | ||||

| nG1 | 1.000 | 0.002 | ||

| nG2 | 5.002 | 1.746 | 14.336 | |

| nG3 | 7.393 | 2.456 | 22.260 | |

The values in italics represent the p-values for the respective statistical analysis

Discussion

Pre-operative biopsy is the gold standard for cancer diagnosis in many cancers, including HNSCC. Ideally, histomorphologic diagnosis and subsequent histopathologic grading upon biopsy enables a prognostic patient stratification by distinction of cancers with comparably benign clinical course from those with aggressive tumour biology. In many entities including prostate and endometrial cancer, pre-operative biopsies therewith enable guidance of therapeutic approaches and clinical decision making, including the choice for neoadjuvant treatments or the selection of watch and wait strategies.18,19 In contrast, studies in HNSCC revealed, that conventional histopathologic grading as defined by WHO criteria in incisional biopsies lacks impact on clinical outcome,20,21 which is in line with studies that reported WHO grading to be of only limited prognostic relevance in resection specimen.13–17 Another important pre-exquisite—if therapy decisions should be based on biopsy readouts—is to ensure the representativity of the data which can be obtained from biopsies. Thus, a high concordance of grading in biopsies and corresponding resection specimen is desirable, as discordances can potentially lead to erroneous decisions and treatment failure. Current WHO grading in HNSCC biopsies not only has limited prognostic impact but also fails to meet this criterion as Dik et al. recently found major discordance of grading between biopsy and corresponding resection specimen for this scheme.20,21

We recently proposed a novel grading algorithm in HNSCC with high prognostic impact17,24 and high inter- and intra-observer concordance25 termed Cellular Dissociation Grade, which has also been shown to work nicely in other SCC entities including in pre-therapeutic biopsies of oesophageal SCC. The CDG is based on the cellular dissociation parameters Tumour Budding and Cell Nest Size, which are both histomorphologic readouts measuring the capability of dissociative growth of an individual carcinoma from either a quantitative (Tumour Budding) or qualitative (Cell Nest Size) point of view. Considering the above discussed potential major prognostic and predictive implications of the data derived early in the diagnostic process from biopsy specimens, we aimed to probe if the prognostic value of the CDG is retained when assessed in pre-therapeutic biopsies of patients suffering from HNSCC. In addition, we analysed the value of the pre-operative CDG for the prediction of post-operative tumour stage, including the presence of occult lymph node metastasis in clinically and radiologically negative cN0 necks.

We found, that Tumour Budding and Cell Nest Size are of major prognostic relevance for patient outcome with presence of high budding activity and single-cell invasion indicating the most aggressive disease course with early relapses and poor survival. Summarising these two parameters and applying our CDG (nG1, nG1, nG3) discriminated three distinct prognostic groups. The prognostic value of the grading system was independent of potential additional influencing factors, such as age, gender and stage and revealed hazard ratios for OS (DSS; DFS) for nG2/nG3 HNSCC of 2.5 (6.1; 5.0)/4.2 (11.1; 7.4). Again, previous studies revealed that the current conventional WHO-based grading of HNSCC does not show prognostic impact when applied in biopsy specimens.20,21 In addition, the Kappa value κ = 0.89 for the corresponding biopsy and resection specimen grading with 94% concordantly graded HNSCC proves the representativity of the biopsy grading results for the overall tumour configuration. Of 160 HNSCC, an upgrading from biopsy to resection specimen was only observed in ten cases. In all of these cases, the biopsies only harboured very superficially captured carcinoma. In only one case, downgrading was evident. Review of both specimens revealed that this case was a T1 HNSCC, in which a large incisional biopsy comprised the major part of the carcinoma leaving only residual invasive cancer within the resection specimen. Regarding the concordance of the two parameters budding and cell nest size in biopsy and the corresponding resection specimen, concordance rate of the morphologic pattern tumour budding was strikingly higher (κ = 0.87) compared with the pattern cell nest size (κ = 0.44). While tumour budding provides an overview of the dissociative growth capability, cell nest size represents the highest dissociative capability within the area of highest aggressiveness. This might be the reason why tumour heterogeneity plays a more prominent role in the evaluation of the cell nest size: biopsies by nature only capture a smaller part of carcinomas compared to resection specimen, potentially leading to a bias induced by tumour heterogeneity when evaluating cell nest size as the area of highest dissociative capability might not be included in the biopsy specimen. However, this bias particularly comes to effect in cases with scores 2/3 for cell nest size, and therewith obviously does not lead to a major effect on the sum score and the final grade, which is demonstrated by the high kappa value for the overall grading. Dik et al. analysed concordance of WHO-based grading of HNSCC between biopsy and resection specimens and found >50% discordantly graded cases in their studies.20,21 Concordance rates of histopathological grading in other entities as prostate cancer were higher with 50–70% concordant cases.28,29 The concordance rate of our grading is surprisingly high, which might be due to large and representative incisional biopsies performed at our institution.

Besides our grading approach, several alternative HNSCC grading systems have been proposed, including the “malignancy grading of invasive margins” (MG),30 the “histological risk model” (HR)15 and the “tumour budding and depth of invasion” (BD)31 grading system. In contrast to our CDG, which has been successfully applied in oral SCC,17,25 in laryngeal and in hypopharyngeal SCC,24 and which has been transvalidated in oesophageal,26 cervical32 and pulmonary SCC,27 all of these approaches yielded varying results with respect to prognostic value and interobserver variability.15,16,30,31,33–37 Only the prognostic impact of the BD grading system, which evaluates BA together with tumour invasion depth, was confirmed in recent studies.16,31 However, per definition tumour invasion depth is a parameter that rather describes tumour stage than tumour grade as defined by the current TNM manual.23,38,39 Furthermore, this parameter is not applicable in biopsies, limiting its value for routine biopsy diagnostics.38,40

Incorporation of markers of cellular dissociative capability such as Tumour Budding and Cell Nest Size into a grading system seems reasonable as presence of Tumour Budding has been shown to be associated with an unfavourable disease course not only in HNSCC (reviewed in refs. 41,42) but also in other solid tumours, such as colorectal43,44 and pulmonary carcinomas.27 Confirming our results, Tumour Budding has been shown to be of prognostic value not only in resection but as well in biopsy specimen of these tumour entities (reviewed in ref. 45). Focusing on the biologic background of Tumour budding, recent research has shown, that this histologic pattern might be the morphologic representative of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (reviewed in ref. 46). It has been identified as a sign of invasion and metastasis and has therefore been proposed as a novel hallmark of cancer by Makitie et al. (reviewed in ref. 47).

Both, Tumour Budding and Cell Nest Size as well as the composite parameter CDG when assessed in pre-operative biopsies were strongly correlated with post-operative pT and pN stage. Therefore, post-operative positive nodes were significantly more frequent in cases with a moderate or poor tumour differentiation (nG2/nG3) according to the CDG compared with well-differentiated carcinomas. In contrast, only Cell Nest Size but not Tumour Budding or CDG was correlated with pre-operative staging parameters (cT/cN). This might be due to the high discordance rate of pre-operative clinical cT and cN stage compared with post-operative pT and pN in 36%, respectively, 32% cases—a finding which confirms previous studies in HNSCC studies showing comparably low concordance rates between clinical and pathological staging.6,48,49 Furthermore, in our study, the subgroup of clinically early HNSCC in UICC stages I and II 20% of cN0 necks revealed occult nodal metastasis only detected by pathological examination. Considering the ongoing discussion if clinically nodal-negative necks should be treated by elective neck dissection or by watchful waiting strategies, these results support the notion and confirm previous studies that clinical staging in its current form is not a valuable predictive tool for treatment planning in these patients,10,11,50,51 as it lacks the necessary sensitivity for detection of metastatic disease. Searching for a better biomarker for the presence of occult nodal metastasis in these patients, Sakata et al. proposed Tumour Budding as a novel predictor of occult lymph node metastasis in oral SCC12 in a recent study. In our study—confirming this result—none of clinically cN0-staged patients with nG1 tumour differentiation according to the CDG revealed an occult nodal metastasis upon pathological work-up, whereas occult metastasis was detected in 36% of nG2/nG3 early-stage patients. Our study therewith underlines the potential major importance of Tumour Budding as a predictive biomarker for lymph node metastasis in cN0 necks. The predictive value could potentially be further increased by combining CDG assessment on biopsies with modern imaging modalities such as PET CT.52

Our study clearly has some limitations as the included patient cohort contained a majority of advanced HNSCC. Furthermore, the study cohort included cases from different areas of the head and neck region (oral cavity, larynx, hypopharynx). The study design was based on a prospective-retrospective concept with prospective sample collection from the day of the biopsy/resection followed by retrospective histopathological evaluation. Therefore, additional especially prospective study concepts and multi-centre studies are necessary to validate the prognostic impact of CDG in the pre-operative setting of HNSCC.

Taken together, our study revealed that CDG based on Tumour Budding and Cell Nest Size can successfully be applied in pre-therapeutic biopsies of HNSCC. The high prognostic impact of CDG assessed in biopsy specimen, separating three distinct prognostic groups, was independent of other prognostic parameters. Pre-operative grading was furthermore predictive for the presence of occult nodal metastasis, which had not been detected by routine clinical staging procedures in clinically nodal-negative necks. Considering the prognostic impact in the post-therapeutic setting and the high inter- and intra-observer reliability of the CDG which we demonstrated in previous studies,17,25 we believe, that grading of HNSCC by CDG shows a promising potential for applicability in daily routine pathological and clinical practice. Taking together our previous studies,17,24,25 the major prognostic impact of the CDG was shown in the pre- and post-operative setting in the same homogeneous patient cohort as was the high inter- and intra-observer reproducibility of the grading system. Using the same patient cohort may prove the validity and significance of the results, as it allows to exclude a coincidental effect which might be observed when using different study cohorts.

In conclusion, we believe that our findings provide a rationale for the integration of CDG assessment in routine diagnostics of HNSCC biopsies, since CDG has the potential to play a substantial role in treatment planning and prognostic patient stratification in HNSCC in the pre-therapeutic setting.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the members of the Munich Biobank for their technical assistance.

Author contributions

M.J.: data acquisition, data analysis, methodology, study design, project administration and writing—original draft; K.S.: data acquisition and writing—original draft; F.S.: data acquisition and writing—original draft, B.H.: statistical analysis and writing—original draft; A.K.: clinical data acquisition and writing—original draft; U.S.: clinical data acquisition and writing—original draft; A.P.: clinical data acquisition and writing—original draft; M.W.: clinical data acquisition and writing—original draft; M.S.: data acquisition and writing—original draft; J.B.: data acquisition, statistical analysis and writing—original draft; A.B.R.: data acquisition and writing—original draft; B.K.: data acquisition and writing—original draft; P.K.: data acquisition and writing—original draft; K.K.: data acquisition and writing—original draft; H.D.: data acquisition and writing—original draft; S.M.: data acquisition and writing—original draft; S.E.C.: data acquisition and writing—original draft; W.W.: methodology, study design, supervision and writing—original draft; M.B.: data acquisition, data analysis, methodology, study design, supervision, project administration and writing—original draft.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee of the Technical University of Munich (296/17 s) and all patients agreed at the beginning of their treatment that their tissue may be used for research purposes. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Data availability

All data relevant for this study are given with the main paper, including figures, tables and the supplementary files. The tissue investigated for this study is archived in the Institute of Pathology of the Technical University of Munich.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding information

The work was in part funded by the Else Kröner Fresenius Stiftung to Melanie Boxberg.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Wilko Weichert, Melanie Boxberg

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41416-019-0719-8.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marur S, Forastiere AA. Head and neck cancer: changing epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2008;83:489–501. doi: 10.4065/83.4.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Naggar, A. K. (Hg.). WHO classification of head and neck tumours: International Agency for Research on Cancer. (2017).

- 4.Marur S, Forastiere AA. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: update on epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2016;91:386–396. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pezzuto F, Buonaguro L, Caponigro F, Ionna F, Starita N, Annunziata C, et al. Update on head and neck cancer: current knowledge on epidemiology, risk factors, molecular features and novel therapies. Oncology. 2015;89:125–136. doi: 10.1159/000381717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koch WM, Ridge JA, Forastiere A, Manola J. Comparison of clinical and pathological staging in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: results from Intergroup Study ECOG 4393/RTOG 9614. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2009;135:851–858. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2009.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leusink FK, van Es RJ, de Bree R, Baatenburg de Jong RJ, van Hooff SR, Holstege FC, et al. Novel diagnostic modalities for assessment of the clinically node-negative neck in oral squamous-cell carcinoma. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e554–e561. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70395-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wensing BM, Merkx MA, De Wilde PC, Marres HA, Van den Hoogen FJ. Assessment of preoperative ultrasonography of the neck and elective neck dissection in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuen AP, Ho CM, Chow TL, Tang LC, Cheung WY, Ng RW, et al. Prospective randomized study of selective neck dissection versus observation for N0 neck of early tongue carcinoma. Head Neck. 2009;31:765–772. doi: 10.1002/hed.21033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D'Cruz AK, Vaish R, Kapre N, Dandekar M, Gupta S, Hawaldar R, et al. Elective versus therapeutic neck dissection in node-negative oral cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373:521–529. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haddadin KJ, Soutar DS, Oliver RJ, Webster MH, Robertson AG, MacDonald DG. Improved survival for patients with clinically T1/T2, N0 tongue tumours undergoing a prophylactic neck dissection. Head Neck. 1999;21:517–525. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199909)21:6<517::AID-HED4>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakata J, Yamana K, Yoshida R, Matsuoka Y, Kawahara K, Arita H, et al. Tumour budding as a novel predictor of occult metastasis in cT2N0 tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Hum. Pathol. 2018;76:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2017.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sethi S, Lu M, Kapke A, Benninger MS, Worsham MJ. Patient and tumour factors at diagnosis in a multi-ethnic primary head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cohort. J. Surg. Oncol. 2009;99:104–108. doi: 10.1002/jso.21190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bello IO, Soini Y, Salo T. Prognostic evaluation of oral tongue cancer: means, markers and perspectives (II) Oral Oncol. 2010;46:636–643. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brandwein-Gensler M, Teixeira MS, Lewis CM, Lee B, Rolnitzky L, Hille JJ, et al. Oral squamous cell carcinoma: histologic risk assessment, but not margin status, is strongly predictive of local disease-free and overall survival. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2005;29:167–178. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000149687.90710.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawazaki-Calone I, Rangel A, Bueno AG, Morais CF, Nagai HM, Kunz RP, et al. The prognostic value of histopathological grading systems in oral squamous cell carcinomas. Oral Dis. 2015;21:755–761. doi: 10.1111/odi.12343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boxberg M, Jesinghaus M, Dorfner C, Mogler C, Drecoll E, Warth A, et al. Tumour budding activity and cell nest size determine patient outcome in oral squamous cell carcinoma: proposal for an adjusted grading system. Histopathology. 2017;70:1125–1137. doi: 10.1111/his.13173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Praet C, Libbrecht L, D'Hondt F, Decaestecker K, Fonteyne V, Verschuere S, et al. Agreement of Gleason score on prostate biopsy and radical prostatectomy specimen: is there improvement with increased number of biopsy cylinders and the 2005 revised Gleason scoring? Clin. Genitourin. Cancer. 2014;12:160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fischerova D, Fruhauf F, Zikan M, Pinkavova I, Kocian R, Dundr P, et al. Factors affecting sonographic preoperative local staging of endometrial cancer. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2014;43:575–585. doi: 10.1002/uog.13248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dik EA, Ipenburg NA, Kessler PA, van Es RJJ, Willems SM. The value of histological grading of biopsy and resection specimens in early stage oral squamous cell carcinomas. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2018;46:1001–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dik EA, Ipenburg NA, Adriaansens SO, Kessler PA, van Es RJ, Willems SM. Poor correlation of histologic parameters between biopsy and resection specimen in early stage oral squamous cell carcinoma. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2015;144:659–666. doi: 10.1309/AJCPFIVHHH7Q3BLX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolff, K-D., Bikowski, K., Böhme, P., et al. Diagnostik und therapie des mundhöhlenkarzinoms. AWMF Leitlinie (German treatment guidelines, 2012).

- 23.Gospodarowicz, M. K., Brierley, J. D. & Wittekind, C. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours (John Wiley & Sons, 2017).

- 24.Boxberg M, Kuhn PH, Reiser M, Erb A, Steiger K, Pickhard A, et al. Tumour budding and cell nest size are highly prognostic in laryngeal and hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: further evidence for a unified histopathologic grading system for squamous cell carcinomas of the upper aerodigestive tract. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2019;43:303–313. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boxberg M, Bollwein C, Johrens K, Kuhn PH, Haller B, Steiger K, et al. Novel prognostic histopathological grading system in oral squamous cell carcinoma based on tumour budding and cell nest size shows high interobserver and intraobserver concordance. J. Clin. Pathol. 2019;72:285–294. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2018-205454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jesinghaus M, Boxberg M, Konukiewitz B, Slotta-Huspenina J, Schlitter AM, Steiger K, et al. A novel grading system based on tumour budding and cell nest size is a strong predictor of patient outcome in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2017;41:1112–1120. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weichert W, Kossakowski C, Harms A, Schirmacher P, Muley T, Dienemann H, et al. Proposal of a prognostically relevant grading scheme for pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma. Eur. Respir. J. 2016;47:938–946. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00937-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chun FK, Briganti A, Shariat SF, Graefen M, Montorsi F, Erbersdobler A, et al. Significant upgrading affects a third of men diagnosed with prostate cancer: predictive nomogram and internal validation. BJU Int. 2006;98:329–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuroiwa K, Shiraishi T, Ogawa O, Usami M, Hirao Y, Naito S, et al. Discrepancy between local and central pathological review of radical prostatectomy specimens. J. Urol. 2010;183:952–957. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bryne M, Koppang HS, Lilleng R, Stene T, Bang G, Dabelsteen E. New malignancy grading is a better prognostic indicator than Broders' grading in oral squamous cell carcinomas. J. Oral. Pathol. Med. 1989;18:432–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1989.tb01339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Almangush A, Bello IO, Keski-Santti H, Makinen LK, Kauppila JH, Pukkila M, et al. Depth of invasion, tumour budding, and worst pattern of invasion: prognostic indicators in early-stage oral tongue cancer. Head Neck. 2014;36:811–818. doi: 10.1002/hed.23380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jesinghaus M, Strehl J, Boxberg M, Bruhl F, Wenzel A, Konukiewitz B, et al. Introducing a novel highly prognostic grading scheme based on tumour budding and cell nest size for squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. J. Pathol. Clin. Res. 2018;4:93–102. doi: 10.1002/cjp2.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurokawa H, Zhang M, Matsumoto S, Yamashita Y, Tomoyose T, Tanaka T, et al. The high prognostic value of the histologic grade at the deep invasive front of tongue squamous cell carcinoma. J. Oral. Pathol. Med. 2005;34:329–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2005.00244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindenblatt Rde C, Martinez GL, Silva LE, Faria PS, Camisasca DR, Lourenco Sde Q. Oral squamous cell carcinoma grading systems-analysis of the best survival predictor. J. Oral. Pathol. Med. 2012;41:34–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2011.01068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brandwein-Gensler M, Smith RV, Wang B, Penner C, Theilken A, Broughel D, et al. Validation of the histologic risk model in a new cohort of patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2010;34:676–688. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181d95c37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Y, Bai S, Carroll W, Dayan D, Dort JC, Heller K, et al. Validation of the risk model: high-risk classification and tumour pattern of invasion predict outcome for patients with low-stage oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7:211–223. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0412-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodrigues PC, Miguel MC, Bagordakis E, Fonseca FP, de Aquino SN, Santos-Silva AR, et al. Clinicopathological prognostic factors of oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective study of 202 cases. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2014;43:795–801. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takes RP, Rinaldo A, Silver CE, Piccirillo JF, Haigentz M, Jr., Suarez C, et al. Future of the TNM classification and staging system in head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2010;32:1693–1711. doi: 10.1002/hed.21361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aydil U, Duvvuri U, Kizil Y, Koybasioglu A. Tumour-node-metastasis staging of human papillomavirus negative upper aerodigestive tract cancers: a critical appraisal. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2015;129:1148–1155. doi: 10.1017/S0022215115002686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hubert Low TH, Gao K, Elliott M, Clark JR. Tumour classification for early oral cancer: re-evaluate the current TNM classification. Head Neck. 2015;37:223–228. doi: 10.1002/hed.23581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Almangush A, Pirinen M, Heikkinen I, Makitie AA, Salo T, Leivo I. Tumour budding in oral squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Br. J. Cancer. 2018;118:577–586. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu, Y., Liu, H., Xie, N., Liu, X., Huang, H., Wang, C. et al. Impact of tumour budding in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Head Neck41, 542–550 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Ueno H, Murphy J, Jass JR, Mochizuki H, Talbot IC. Tumour ‘budding' as an index to estimate the potential of aggressiveness in rectal cancer. Histopathology. 2002;40:127–132. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karamitopoulou E, Zlobec I, Kolzer V, Kondi-Pafiti A, Patsouris ES, Gennatas K, et al. Proposal for a 10-high-power-fields scoring method for the assessment of tumour budding in colorectal cancer. Mod. Pathol. 2013;26:295–301. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Almangush A, Youssef O, Pirinen M, Sundstrom J, Leivo I, Makitie AA. Does evaluation of tumour budding in diagnostic biopsies have a clinical relevance? A systematic review. Histopathology. 2019;74:536–544. doi: 10.1111/his.13793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grigore AD, Jolly MK, Jia D, Farach-Carson MC, Levine H. Tumour budding: the name is EMT. Partial EMT. J. Clin. Med. 2016;5:5. doi: 10.3390/jcm5050051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Makitie AA, Almangush A, Rodrigo JP, Ferlito A, Leivo I. Hallmarks of cancer: tumour budding as a sign of invasion and metastasis in head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2019;41:3712–3718. doi: 10.1002/hed.25872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qiao Y, Wang Y, Kang P, Li R, Liu Y, He W. The assessment of the accuracy of clinical preoperative lymph node. Medicine. 2019;98:e13778. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Waal PJ, Fagan JJ, Isaacs S. Pre- and intra-operative staging of the neck in a developing world practice. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2003;117:976–978. doi: 10.1258/002221503322683876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keski-Santti H, Atula T, Tornwall J, Koivunen P, Makitie A. Elective neck treatment versus observation in patients with T1/T2 N0 squamous cell carcinoma of oral tongue. Oral Oncol. 2006;42:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.D'Cruz AK, Dandekar MR. Elective versus therapeutic neck dissection in the clinically node negative neck in early oral cavity cancers: do we have the answer yet? Oral Oncol. 2011;47:780–782. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lowe VJ, Duan F, Subramaniam RM, Sicks JD, Romanoff J, Bartel T, et al. Multicenter trial of [18 f]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography staging of head and neck cancer and negative predictive value and surgical impact in the N0 neck: results from ACRIN 6685. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019;37:1704–1712. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.01182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant for this study are given with the main paper, including figures, tables and the supplementary files. The tissue investigated for this study is archived in the Institute of Pathology of the Technical University of Munich.