Abstract

Ossifying fibroma is a slow-growing benign neoplasm that occurs most often in the jaws, especially the mandible. The tumor is composed of bone that develops within fibrous connective tissue. Some ossifying fibromas consist of cementum-like calcifications, while others contain only bony material; however, a mixture of these calcification types is commonly seen in a single lesion. Of the craniofacial bones, the mandible is the most commonly involved site, with the lesion typically inferior to the premolars and molars. Ossifying fibroma of the jaw shows a female predominance. Some reports of ossifying fibroma have been published in the literature; however, this report continues the research on this topic by detailing 3 types of ossifying fibroma findings on panoramic radiographs and cone-beam computed tomographic images of 4 patients. The radiographs of the presented cases could help clinicians understand the variations in the radiographic appearance of this lesion.

Keywords: Ossifying Fibroma, Benign Tumor, Cone-Beam Computed Tomography, Mandible

Introduction

Ossifying fibroma is defined as an encapsulated benign neoplasm composed of varying amounts of bone or cementum-like tissue in the fibrous tissue stroma.1 It is a slow-growing benign neoplasm that occurs most often in the jaws, especially the mandible. The tumor is composed of bone that develops within fibrous connective tissue.

In 1968, Hamner et al.2 analyzed and classified 249 cases of fibro-osseous jaw lesions originating in the periodontal membrane. In 1973, Waldron and Giansanti3 presented 65 cases (43 of which had adequate radiographs and clinical histories), and argued that these lesions should be considered to comprise a spectrum of processes arising from periodontal ligament cells. In 1985, Eversole et al.4 presented a description of the radiographic characteristics of central ossifying fibroma and noted 2 major patterns: expansile unilocular radiolucencies and a multilocular configuration.

Ossifying fibroma is slow-growing and well-demarcated from the adjacent bone. Some lesions may grow to become massive, causing considerable aesthetic and functional deformities. Due to the presence of both bone and cementum-like tissue in ossifying fibromas, these lesions are described using the terms ossifying fibroma, cemento-ossifying fibroma, and cementifying fibroma. Nonetheless, the consensus is that these 3 terms describe the same underlying type of lesion.5,6,7,8

Ossifying fibroma most commonly occurs in patients in the second to fourth decades of life, although it may arise in children and adolescents, as well as in older adults.1 The mandible (particularly the molar region) is affected more often than the maxilla, whereas among the other cranial and facial bones, the periorbital, frontal, ethmoid, sphenoid, and temporal bones are also relatively common sites of this tumor.8,9

Some reports of ossifying fibroma have been published; however, this report extends these findings by describing 4 cases of ossifying fibroma involving the mandible using panoramic radiography and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT). The radiographs of the presented cases provide further insights into the variable radiographic appearances of this lesion. Multiple lesion types, including cystic and mixed-density lesions, are presented herein.

Case Report

Case 1

A 26-year-old woman was referred to our hospital for further evaluation of a radiolucent lesion on the left mandibular second molar. Upon oral examination, no signs of inflammation were present, and no response to palpation around the area of the lesion was noted. A percussion test of the second molar was negative, and no changes in the mobility of the teeth were observed.

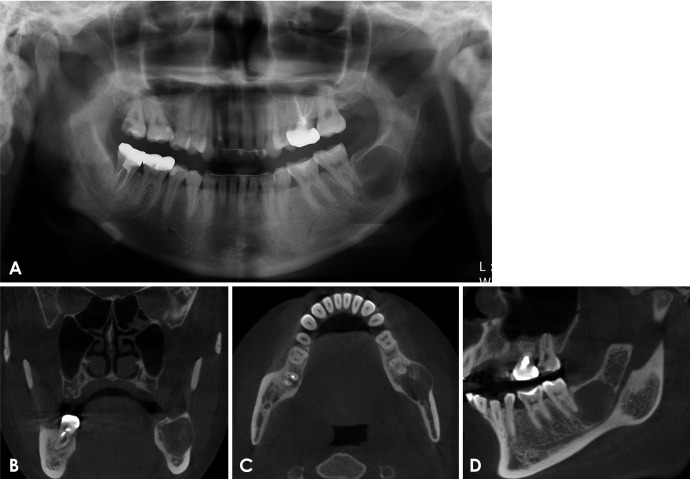

A panoramic radiograph showed an oval-shaped, well-defined radiolucent lesion overlapping with the distal root of the mandibular second molar and extending to the mandibular angle above the mandibular canal (Fig. 1A). A septum was identified in the middle part of the lesion, and the margin of the lesion was corticated. The lesion extended into the alveolar ridge and posteriorly extended to the front of the ascending part of the mandibular canal. The mandibular canal adjacent to the lesion was displaced inferiorly. No absorption or displacement of the root of the mandibular second molar was observed.

Fig. 1. A. A panoramic radiograph showing an oval-shaped radiolucency with a well-defined border in the left posterior mandible. The mandibular canal is displaced inferiorly. B. A coronal cone-beam computed tomographic (CBCT) image shows a concentrically corticated lesion in the left mandible. Radiopaque foci are observed within the lesion, and the lesion has slightly expanded to the buccal side. C. An axial CBCT image shows buccal expansion of the lesion. There are radiopaque foci within the lesion, and a thin, radiopaque rim is visible. D. A sagittal CBCT image shows a well-defined radiolucent lesion. The mandibular canal is displaced inferiorly.

A coronal CBCT image showed a concentrically corticated lesion in the left mandible. Radiopaque foci were visible within the lesion. The lesion was expanded slightly to the alveolar ridge and buccal side (Fig. 1B). An axial CBCT image also showed buccal expansion of the lesion, as well as radiopaque foci within the lesion and a thin, radiopaque rim (Fig. 1C). A sagittal CBCT image showed a well-defined radiolucent lesion. The lesion overlapped with the distal root of the mandibular second molar, and the mandibular canal was displaced inferiorly (Fig. 1D).

Based on the radiographic findings of a well-defined border with a corticated margin, clinicians anticipated that the lesion would be diagnosed as either an odontogenic cyst or a cemento-osseous lesion, and surgical enucleation was performed accordingly.

Case 2

A 40-year-old woman presenting chiefly with a radiolucent lesion in the mandibular left molar area was referred to our hospital. The patient did not report feeling the presence of the lesion or associated pain. On the oral examination, signs of inflammation, such as swelling, drainage, edema, or redness, were absent. The left mandibular first molar was not sensitive to percussion, and the results of palpation were normal. However, the left mandibular second molar was sensitive to percussion and air. The pulpal vitality of both teeth was normal.

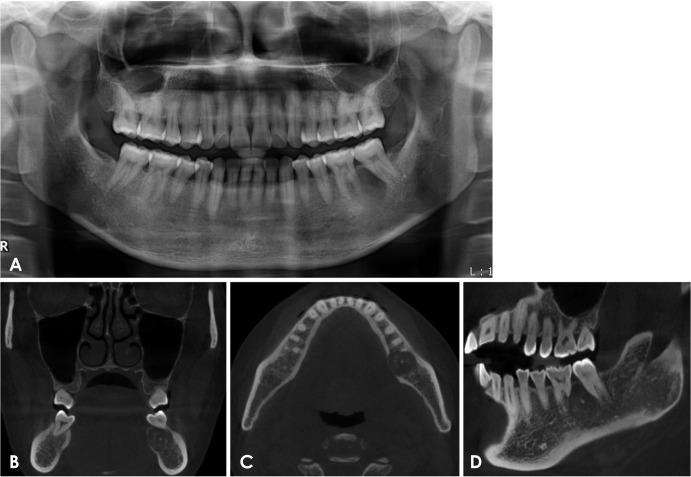

A panoramic radiograph showed a round, mixed radiolucent and radiopaque lesion extending from the left mandibular first molar to the mesial side of the root of the second molar (Fig. 2A). The root of the second molar was displaced distally. The lesion extended from the alveolar ridge to the upper wall of the mandibular canal.

Fig. 2. A. A panoramic radiograph shows a round radiolucency around the distal root of the left first mandibular molar. The root of the second molar is displaced distally. B. A coronal CBCT image shows a well-defined mixed radiopaque and radiolucent lesion in the left mandible. The lesion has slightly expanded to the lingual side. C. An axial CBCT image shows showing lingual expansion of the lesion. Radiopaque foci are observed within the lesion, and a thin, radiopaque rim is visible. D. A sagittal CBCT image shows a moderately defined lesion border.

A coronal CBCT image showed a well-defined mixed radiopaque and radiolucent lesion in the left mandible (Fig. 2B). The lesion showed slight lingual expansion. An axial CBCT image showed lingual expansion of the lesion and consequent thinning of the lingual cortical bone (Fig. 2C). Radiopaque foci were visible within the lesion, and a thin, radiopaque rim could be observed. A sagittal CBCT image showed a moderately defined lesion border (Fig. 2D). The root of the second molar was displaced distally.

Case 3

A 39-year-old woman was referred to our hospital for further evaluation of a mixed radiolucent and radiopaque lesion on the left mandibular first molar. Upon oral examination, no sign of inflammation was present, and no response to palpation in the area of the lesion was noted. A percussion test of the first molar was mildly positive, and changes in the mobility of the tooth were observed.

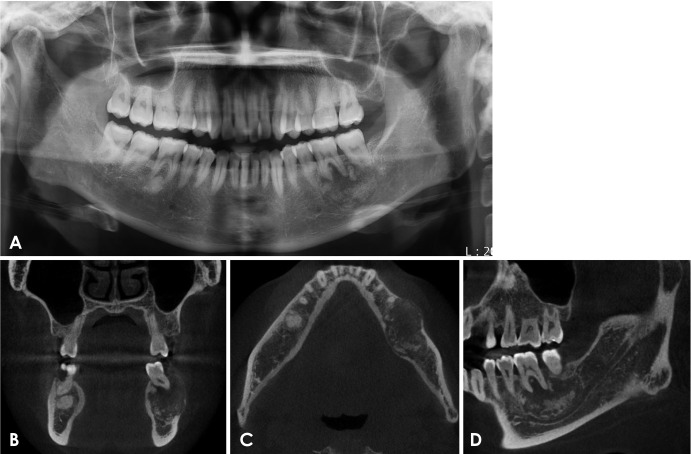

A panoramic radiograph showed a round, mixed radiopaque and radiolucent lesion around the root of the left mandibular first molar (Fig. 3A). The mesial root of the first molar had been resorbed. The lesion showed slight inferior expansion, thereby displacing the mandibular canal inferiorly.

Fig. 3. A. A panoramic radiograph shows a round mixed radiopaque and radiolucent lesion around the root of the left first mandibular molar. B. A coronal CBCT image shows a mixed radiopaque and radiolucent lesion. The lesion is expanded to the buccal side. C. An axial CBCT image shows asymmetrical buccal-lingual expansion and a thin, radiolucent rim. D. A sagittal CBCT image shows a mixed radiopaque-radiolucent lesion. The mandibular canal is displaced inferiorly.

A coronal CBCT image showed a mixed radiopaque and radiolucent lesion (Fig. 3B). The lesion had expanded to the buccal side, resulting in thinning of the buccal cortical bone. An axial CBCT image showed an asymmetrical buccal-lingual expansion and a thin, radiolucent rim (Fig. 3C). A sagittal CBCT image showed a mixed radiopaque and radiolucent lesion (Fig. 3D). Irregular-shaped radiopaque masses were visible on the lower parts of the lesion. The mandibular canal was displaced inferiorly.

Case 4

A 35-year-old woman presenting chiefly with a radiopaque lesion in the left mandibular molar area was referred to our hospital.

The patient reported pain when chewing with the left mandibular molar. Upon oral examination, signs of inflammation, such as swelling, drainage, edema, or redness, were absent. The left mandibular first molar was not sensitive to percussion, and the results of palpation were normal. However, the left mandibular second molar was percussion-sensitive. The pulpal vitality of both teeth was normal.

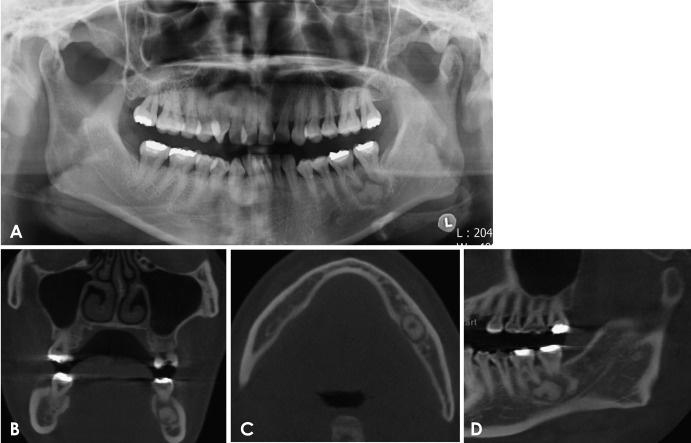

A panoramic radiograph showed a round radiopaque lesion surrounded by a radiolucent rim around the roots of the left mandibular first and second molars (Fig. 4A). The radiopaque mass occupied most of the lesion and surrounded the roots of the mandibular first and second molars. Coronal CBCT showed a radiopaque lesion surrounded by a radiolucent rim with no expansion of the lesion (Fig. 4B), while axial CBCT showed slight lingual expansion of the lesion (Fig. 4C). The lesion had expanded to the lingual side, and the lingual cortical bone was thinned. A sagittal CBCT image showed a radiopaque lesion surrounded by a radiolucent rim (Fig. 4D). The mandibular canal was displaced inferiorly.

Fig. 4. A. A panoramic radiograph shows a round radiopaque lesion surrounded by a radiolucent rim around the roots of the left first and second mandibular molars. B. A coronal CBCT image shows a radiopaque lesion surrounded by a radiolucent rim. No expansion of the lesion is visible. C. An axial CBCT image shows slight lingual expansion of the lesion. D. A sagittal CBCT image shows a radiopaque lesion surrounded by a radiolucent rim. The mandibular canal is displaced inferiorly.

Discussion

The term “ossifying fibroma” has been used since 1927, and since 1968, cementum-containing tumors have been jointly categorized.2 In 1971, the World Health Organization (WHO) indicated that cementum-containing lesions could be classified as 4 types: fibrous dysplasia, ossifying fibroma, cementifying fibroma, and cemento-ossifying fibroma.10 In a subsequent WHO classification, benign fibro-osseous lesions of the oral and maxillofacial regions were divided into osteogenic neoplasms or non-neoplastic bone lesions, with the former category including cementifying ossifying fibroma.11 However, the term “cementifying ossifying fibroma” was simplified to “ossifying fibroma” in the 2005 WHO classification system.12

Clinically, ossifying fibroma is usually asymptomatic and is often found accidentally on routine dental examinations. It shows a female predominance and can occur in individuals of any age, although it is most common in the second to fourth decade of life.1,3 In most cases, it is slow-growing, but it is occasionally aggressive, particularly its juvenile subtypes. Additionally, its growth is usually concentric. Ossifying fibroma predominantly affects the facial bone, most commonly in the mandible, where it arises apical to the premolars and molars and superior to the mandibular canal. All cases in this report occurred in women and were in the mandibular molar area. The patients were referred to our hospital because the lesions were found inadvertently during an intraoral examination at other clinics.

Although MacDonald-Jankowski7 proposed that radiological diagnoses of large fibro-osseous lesions were not difficult for specialist radiologists to make, not all radiological diagnoses in their report aligned with the final histological diagnoses. However, for the relatively early cases in that study, computed tomography was unavailable, and the similarities in radiological appearance between jawbone tumors may have confused the radiological diagnoses.13 In a study by Liu et al., the radiographic characteristics of the tumor showed 2 patterns: cystic lesions (either unicystic or multicystic) and mixed-density lesions.

The predominant radiographic features of ossifying fibroma are a round or oval well-defined, expansile mass with a corticated border and a variable degree of internal radiopacity. The internal aspect of these lesions can be granular, resembling fibrous dysplasia, and they may have a thin, radiolucent periphery representing a fibrous capsule. This can result in the expansion of the outer cortical plate of bone. The density of these lesions is mixed, and the internal structure may be a mixture of radiolucent and radiopaque tissue. In this report, the 4 cases displayed 3 different types of internal structures (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4).

Previous research has shown that the radiographic borders of ossifying fibroma appear relatively smooth, well-defined, and mostly corticated. The contour is regular. The lesion tends to be concentric within the medullary part of the bone, with an approximately equal outward expansion in all directions.13 The mandibular canal adjacent to the lesion is displaced inferiorly, and resorption or displacement of the root of the associated tooth is often observed. The lamina dura of the involved teeth is typically missing. Based on radiographic findings, these lesions may occur at similar locations on the mandible and present with varying shapes and boundaries. However, the internal structures may have different appearances, as in the cases presented in this report. All 4 cases showed well-defined borders and slight expansion. In 2 cases, buccal expansion was seen, while 1 case displayed lingual expansion with thinning of the cortical bone. In the final case, no swelling was observed. In 3 cases, the mandibular canal was displaced inferiorly, while only 1 case showed tooth displacement.

The differential diagnosis of ossifying fibroma includes lesions with a mixed radiolucent and radiopaque internal structure.1,14,15 Differentiating these lesions from fibrous dysplasia can be very difficult. Ossifying fibromas usually have better-defined boundaries, and they occasionally have a cortex with an adjacent internal radiolucent rim, whereas the periphery of fibrous dysplasia typically blends into the surrounding bone. The internal structure of fibrous dysplasia may be more homogeneous and show less variation in terms of pattern than ossifying fibroma. Both types of lesions can displace teeth, but ossifying fibroma causes displacement from a specific point or epicenter.1 The expansion of the jaws associated with ossifying fibroma is more concentric, with a clearer epicenter, than occurs in cases of fibrous dysplasia, which enlarges the bone while distorting the overall shape less. Crucially, this differentiation influences the treatment of choice, which is resection for an ossifying fibroma and observation for fibrous dysplasia.

The differential diagnosis depends on the degree and pattern of internal radiopacity. The differential diagnosis includes benign mixed radiolucent and radiopaque neoplasms, with the diagnosis determined by clinical and radiographic behavior. Fibrous dysplasia refers to the replacement of normal bone with fibrous tissue containing foci of immature woven bone. Although fibrous dysplasia shows poorly defined expansion, the general shape of the involved bone is maintained. In contrast, ossifying fibroma displays tumor-like, concentric expansion. In the cases in this report, concentric expansion was observed, and all 4 subjects were female. All lesions were found in the mandibular molar area.

The differential diagnosis of ossifying fibroma that produces a largely homogeneous amorphous bone from periapical osseous dysplasia may be difficult, especially for large single lesions of periapical osseous dysplasia. However, periapical osseous dysplasia is often multifocal, whereas ossifying fibroma is not. A wide sclerotic border, as well as a more undulating expansion, is more characteristic of the slow-growing periapical osseous dysplasia. The epicenter of periapical osseous dysplasia is located at the apex of the tooth, within the alveolar process of the jaws.

Occasionally, a diagnosis of cementoblastoma is considered. Cementoblastoma is a true benign neoplasm of the cementum with the capacity for limitless proliferation. The tumor manifests as a bulbous, often expansile growth of the cementum on the tooth root. Cementoblastoma similarly displays a radiolucent periphery. In most cases, the root is resorbed or disappears into the lesion.

In conclusion, ossifying fibroma is most commonly found in the mandible. Most cases are asymptomatic, but in some cases, swelling or expansion is observed. Radiographically, ossifying fibroma most frequently appears as a well-defined mixed radiolucent and radiopaque lesion. In many cases, CBCT images are helpful for diagnosing these lesions.

Footnotes

This study was supported by research fund from Chosun University Dental Hospital in 2018.

References

- 1.Koenig LJ, Tamimi DF, Petrikowski CG, Perschbacher SE. Diagnostic imaging: oral and maxillofacial. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamner JE, 3rd, Scofield HH, Cornyn J. Benign fibro-osseous jaw lesions of periodontal membrane origin. An analysis of 249 cases. Cancer. 1968;26:861–878. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196810)22:4<861::aid-cncr2820220425>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waldron CA, Giansanti JS. Benign fibro-osseous lesions of the jaws: a clinical-radiologic-histologic review of sixty-five cases. II. Benign fibro-osseous lesions of periodontal ligament origin. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1973;35:340–350. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(73)90072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eversole LR, Merrell PW, Strub D. Radiographic characteristics of central ossifying fibroma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985;59:522–527. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(85)90096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waldron CA. Fibro-osseous lesions of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51:828–835. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(10)80097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang CC, Hung HY, Chang JY, Yu CH, Wang YP, Liu BY, et al. Central ossifying fibroma: a clinicopathologic study of 28 cases. J Formos Med Assoc. 2008;107:288–294. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(08)60089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacDonald-Jankowski DS. Fibro-osseous lesions of the face and jaws. Clin Radiol. 2004;59:11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vegas Bustamante E, Gargallo Albiol J, Berini Aytés L, Gay Escoda C. Benign fibro-osseous lesions of the maxillas: analysis of 11 cases. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:E653–E656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng C, Takahashi H, Yao K, Nakayama M, Makoshi T, Nagai H, et al. Cemento-ossifying fibroma of maxillary and sphenoid sinuses: case report and literature review. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2002;(547):118–122. doi: 10.1080/000164802760057734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pindborg JJ, Kramer IR. World Health Organization, editors. International histological classification of tumours. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1971. Histological typing of odontogenic tumours, jaw cysts, and allied lesions; pp. 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kramer IR, Pindborg JJ, Shear M. Histologic typing of odontogenic tumors. 2nd ed. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 1992. Neoplasm and other lesions related to bone; pp. 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reichart PA, Philipsen HP, Sciubba JJ. The new classification of head and neck tumours (WHO) - any changes? Oral Oncol. 2006;42:757–758. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y, Wang H, You M, Yang Z, Miao J, Shimizutani K, et al. Ossifying fibromas of the jaw bone: 20 cases. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2010;39:57–63. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/96330046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mallya SM, Lam EW. White and Pharoah's oral radiology; principles and interpretation. 8th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2019. pp. 445–446. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Triantafillidou K, Venetis G, Karakinaris G, Iordanidis F. Ossifying fibroma of the jaws: a clinical study of 14 cases and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;114:193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]