Abstract

Background

The acupoint specificity has been considered important issue in acupuncture research. In clinical aspects, it is essential to identify which acupoints are associated specifically with a particular disease. The present study aimed to identify the specificity of acupoint selection (forward inference) and the specificity of acupoint indication (reverse inference) from the online virtual diagnosis experiment.

Methods

Eighty Korean Medicine doctors conducted the virtual medical diagnoses provided for 10 different case reports. For forward inference, the acupoints prescribed for each disease were quantified and the data were normalised among 30 frequently used acupoints using Z-scores. For reverse inference, diseases for each acupoint were quantified and the data were normalized among 10 disease using Z-scores.

Results

Using forward inference we demonstrated the specificity of acupoint selection in each disease. Using reverse inference we identified the specificity of acupoint indication in each acupoint. In general, a certain acupoint can be selected specifically for a particular disease, and it has a specific indication for the disease. However, the specificity of acupoint indication and the specificity of acupoint selection are not always identical.

Conclusions

The selection of an acupoint for a particular disease does not imply that the acupoint has specific indications for that disease. Inferring the specificity of acupoint indication from clinical observations should be considered.

Keywords: Acupuncture, Bayesian inference, Indication, Specificity

1. Introduction

Although some acupoints show increased densities of nerve endings or connective tissue distributions, the relationship between therapeutic effects and the physiological characteristics of acupoints is yet to be revealed.1, 2, 3 The clinical significance of acupoints, rather than anatomical or physiological features, is potentially the component related to acupoint specificity.4 As acupoint selection is specific to target diseases and symptoms, each acupoint is generally assumed to have a specific indication.3 However, the questions of which acupoints are associated specifically with a particular disease, and conversely, which indications are specific for certain acupoints, may not always yield the same answers, despite their similarity.

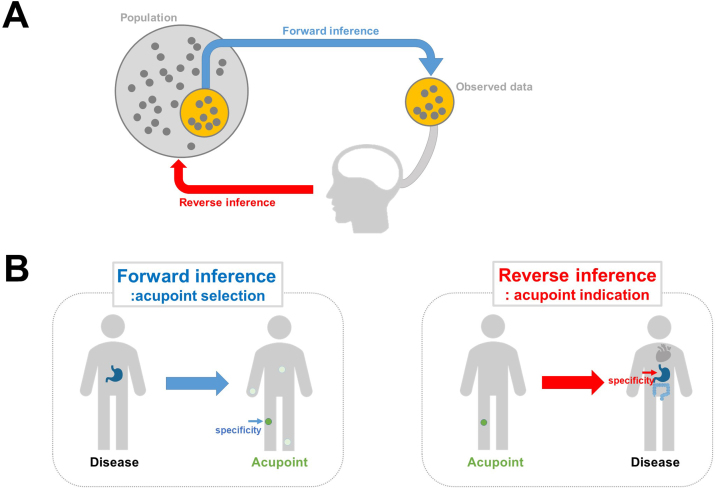

According to Bayes’ theorem, we can infer posterior probability from a statistical model of observed data.5 In acupuncture practice, forward inference data can be generated from clinical observations.6, 7 Certain acupoints can be selected specifically for a particular disease, with the probability of acupoint selection for that disease represented as: P (Acupoint | Disease). Conversely, a clinician can infer the specificity of an acupoint indication from the observed data, with the probability of disease targeted by a certain acupoint represented as: P (Disease | Acupoint) (Fig. 1). Forward inference is typically used for acupoint selection for a particular disease; its use to determine the specificity of an acupoint indication may lead to logical error (see discussion for more detail). Instead, reverse inference can be applied to identify the specificity of an acupoint indication.

Fig. 1.

A. A schematic view of forward and reverse inference based on the Bayesian theorem. B. A certain acupoint can be selected specifically for a particular disease. The probability of acupoint selection, given a particular disease, is represented as P (Acupoint | Disease). (Left) A clinician can infer the specificity of an acupoint’s indication from observed data. The probability of a particular disease, given a certain acupoint, is represented as P (Disease | Acupoint). (Right)

The present study conducted an online virtual diagnosis experiment to identify the specificities of acupoint selection and acupoint indication. Here, we provide an example of the issues related to the specificity of acupoint selection (forward inference) and the specificity of acupoint indication (reverse inference).

2. Methods

2.1. Data collection

An online experiment was conducted with 80 practising Korean Medicine doctors. The participating doctors prescribed acupoint combinations for 10 diseases, Dk [Dk = disease k, (k = 1,2,…10)]. The case presentations for the experiment included medical information, major symptoms, medical histories and laboratory test results. The 10 medical cases included disease 1 (Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: H81.1), disease 2 (gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: K21.0), disease 3 (menopausal climacteric states: N95.1), disease 4 (derangement of meniscus: M23.2), disease 5 (diabetic neuropathy: E10.4), disease 6 (chronic prostatitis: N41.1), disease 7 (panic disorder: F41.0), disease 8 (intervertebral disc disorders: M51.0), disease 9 (fibromyalgia: M79.7), and disease 10 (puerperal disorder: U32.7).

All procedures were conducted with the approval of the Institute Review Board of Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Republic of Korea (KHSIRB-17-046). The experimental method has been described in detail previously and further analysis was conducted to identify the specificity of acupoint indication presented in the current study.8

2.2. Forward inference: specificity of acupoint selection

The 30 most frequently selected acupoints, Al [ Al(l = 1,2,…30)], were included in the analysis. The definition of acupoint selection specificity was based on forward inference. The probability that an acupoint would be selected for a given disease was calculated by dividing the frequency of selection of that acupoint by the total number of acupoint selections. Probability values were Z-transformed for the assessment of statistical significance (Z > 1.96). Thus, forward inference was performed as below:

2.3. Reverse inference: specificity of acupoint indication

The definition of acupoint indication specificity was based on reverse (i.e. Bayesian) inference. The probability of a given disease based on acupoint selection was calculated by dividing the frequency of selection of that disease by the total number of disease selections. Probability values were Z-transformed for the assessment of statistical significance (Z > 1.96). Thus, reverse inference was performed as below:

3. Results

3.1. Forward inference: specificity of acupoint selection

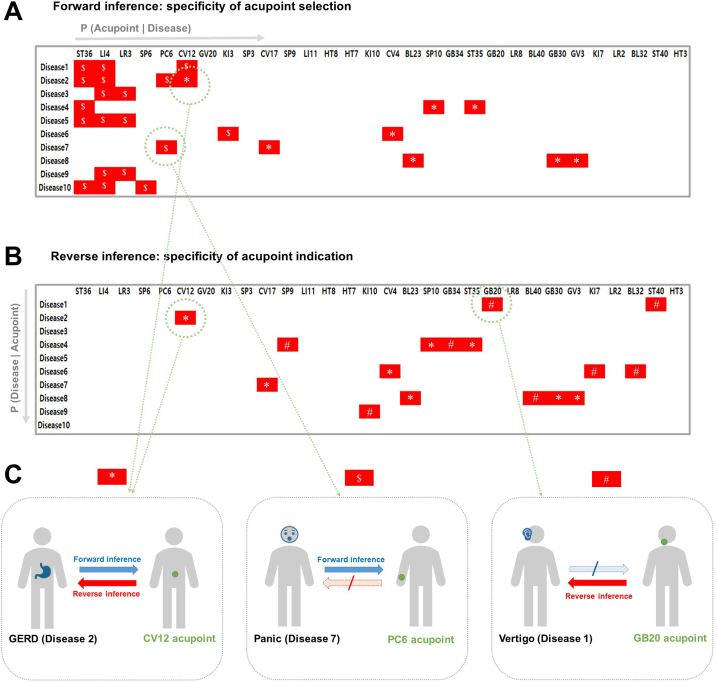

The z-scores illustrate how frequently each acupoint was used for each disease compared to the overall mean prescription frequency for that disease. We demonstrated the specificity of acupoint selection in each disease. For instance, ST36, LI4, and CV12 were specifically chosen for the treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (Disease 1) while BL23, GB30, and GV3 were specifically chosen for the treatment of lumbar herniated intervertebral disc (Disease 8) (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Specificity of acupoint selection and acupoint indication.

A. Forward inference of the specificity of acupoint selection. The 10 medical cases included disease 1 (Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: H81.1), disease 2 (gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: K21.0), disease 3 (menopausal climacteric states: N95.1), disease 4 (derangement of meniscus: M23.2), disease 5 (diabetic neuropathy: E10.4), disease 6 (chronic prostatitis: N41.1), disease 7 (panic disorder: F41.0), disease 8 (intervertebral disc disorders: M51.0), disease 9 (fibromyalgia: M79.7), and disease 10 (puerperal disorder: U32.7).

B. Reverse inference of the specificity of acupoint indication. * Pattern 1: a certain acupoint can be selected specifically for a particular disease, and that acupoint has a specific indication for the disease. $ Pattern 2: a certain acupoint can be selected specifically for a particular disease, but it has no specific indication for that disease. # Pattern 3: a certain acupoint is not selected specifically for a particular disease, but the acupoint can have a specific indication for the disease. Probability values were Z-transformed for the assessment of statistical significance (Z > 1.96, marked in red).

C. Examples of forward and reverse inference of the data. The CV12 acupoint can be selected specifically for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and it has a specific indication for the treatment of GERD (left). The PC6 acupoint can be selected specifically for panic disorder, but PC6 has no specific indication for the treatment of this disorder (middle). The GB20 acupoint is not selected specifically for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, but GB20 has a specific indication for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (right).

3.2. Reverse inference: specificity of acupoint indication

The z-scores illustrate how frequently each disease was associated with each acupoint compared to the overall mean disease for that acupoint. We identified the specificity of acupoint indication in each acupoint. For instance, fibromyalgia (Disease 9) is the specific indication of acupoint KI10 while lumbar herniated intervertebral disc (Disease 8) is the specific indication of acupoint BL23 (Fig. 2B).

3.3. Comparison of forward inference and reverse inference

Three patterns of the specificity of acupoint selection and acupoint indication were identified. In the first pattern, a certain acupoint can be selected specifically for a particular disease, and it has a specific indication for the disease. For instance, acupoint CV12 can be selected specifically for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and this acupoint has specific indications for the treatment of GERD. In the second pattern, a certain acupoint can be selected specifically for a particular disease, but it has no specific indication for the disease. For example, the PC6 acupoint can be selected specifically for panic disorder, but PC6 has no specific indication for the treatment of this disorder. In the third pattern, a certain acupoint is not selected specifically for a particular disease, but it has a specific indication for the disease. For instance, the GB20 acupoint is not selected specifically for the treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, but the specific indication for GB20 can be benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (Fig. 2C).

4. Discussion

This study identified the specificities of acupoint selection and acupoint indication from the online virtual diagnosis experiment, based on forward inference and reverse inference based on Bayes’ Theorem. Forward inference, in this context, refers to the probability in which a certain acupoint is selected specifically for a particular disease. Forward inference data can be generated in experimental virtual diagnosis study, clinical trials, as well as systematic review and meta-analysis. In the current study, we found that BL23, GB30, and GV3 were specifically chosen for the treatment of the lumbar herniated intervertebral disc. These findings were in line with the previous study in which these acupoints were frequently used for the treatment of low back pain from the database of clinical trials.7, 9 In order to choose acupoints to treat a certain disease properly in clinical practice, it is important to know which acupoints were selectively chosen for the treatment of certain disease using forward inference.

Forward inference is informative in the identification of acupoints that are plausible candidate to treat a particular disease. However, it can lead to a logical error in making conclusions about acupoint indication specificity. In order to identify acupoint indication specificity, we need to implement reverse inference analyses, i.e. the probability of a given disease based on acupoint selection, rather than forward inference analyses, i.e. probability that an acupoint would be selected for a given disease. In our analysis, the specificity of acupoint indication and the specificity of acupoint selection were not always identical. For instance, the PC6 acupoint was specifically selected for panic disorder, but the indication of PC6 did not include panic disorder. The GB20 acupoint was not specifically selected for the treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, but the indication of GB20 included benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. This result shows the discrepancy between the acupoint indication and acupoint selection, and the meaning of forward inference and reverse inference in the interpretation of acupoint prescription data. Selection of acupoints by doctors for a particular disease does not always imply that the particular disease is the specific indication of the acupoint.

In this study, we identified the specificities of acupoint selection and acupoint indication using an example of online virtual diagnosis experiment. The specificity of acupuncture selection can be generated from clinical observations through forward inference. Instead, acupuncture practitioners infer the specificity of an acupoint indication from the observed data through reverse inference. The present study proposed that reverse inference should be considered to identify the specificity of acupoint indication. In order to determine the specificity of acupoint indication, however, further studies are necessary to investigate the associations between a disease and selected acupoints of real world data with a large sample size.

Our findings suggest that while the specificity of acupoint indication is generally inferred from the specificity of acupoint selection, they are not always identical. The selection of an acupoint for a particular disease does not imply that the acupoint has specific indications for that disease. Therefore, we should take the specificity of acupoint indication from clinical observations into account as it will increase our understanding of the relationship between acupoints and diseases.

Author contributions

YCH, YSL, YHR, ISL and YC conceived the ideas and drafted the manuscript. YCH and YC analyzed the data. All authors reviewed the final paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (No. 2018R1D1A1B07042313), and the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine (no. KSN1812181).

Ethical statement

All procedures were conducted with the approval of the Institute Review Board of Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Republic of Korea (KHSIRB-17-046).

Data availability

The data will be made available upon request.

References

- 1.Chae Y., Chang D.S., Lee S.H., Jung WM, Lee IS, Jackson S. Inserting needles into the body: a meta-analysis of brain activity associated with acupuncture needle stimulation. J Pain. 2013;14:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langevin H.M., Churchill D.L., Wu J., Badger GJ, Yandow JA, Fox JR. Evidence of connective tissue involvement in acupuncture. FASEB J. 2002;16:872–874. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0925fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Napadow V. When a white horse is a horse: embracing the (obvious?) overlap between acupuncture and neuromodulation. J Altern Complement Med. 2018;24:621–623. doi: 10.1089/acm.2018.29047.vtn. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jung W.M., Lee S.H., Lee Y.S., Chae Y. Exploring spatial patterns of acupoint indications from clinical data: a STROBE-compliant article. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e6768. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poldrack R.A. Can cognitive processes be inferred from neuroimaging data? Trends Cogn Sci. 2006;10:59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jung W.M., Park I.S., Lee Y.S., Kim CE, Lee H, Hahm DH. Characterization of hidden rules linking symptoms and selection of acupoint using an artificial neural network model. Front Med. 2019;13:112–120. doi: 10.1007/s11684-017-0582-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee I.S., Lee S.H., Kim S.Y., Lee H., Park H.J., Chae Y. Visualization of the meridian system based on biomedical information about acupuncture treatment. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/872142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim C.H., Yoon D.E., Lee Y.S., Jung W.M., Kim J.H., Chae Y. Revealing associations between diagnosis patterns and acupoint prescriptions using medical data extracted from case reports. J Clin Med. 2019;8:1–10. doi: 10.3390/jcm8101663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee S.H., Kim C.E., Lee I.S., Jung WM, Kim HG, Jang H. Network analysis of acupuncture points used in the treatment of low back pain. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/402180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available upon request.