Highlights

-

•

Granulomatous disease is not commonly associated with Chlamydia Trachomatis.

-

•

Rare presentation of ascites and elevated CA125 demonstrating Chlamydia Trachomatis.

-

•

Add Chlamydia to the differential diagnosis when encountering granulomatous disease.

-

•

Obtain cervical cultures in sexually active patients with unknown pelvic etiology.

Keywords: Chlamydia trachomatis, Chlamydia infection, Sexually transmitted infections, Pelvic inflammatory disease, Granulomatous inflammation

Abstract

Background

This case provides a rare case of Chlamydia Trachomatis presenting with ascites and granulomatous peritonitis.

Case

A 23-year old gravida 0 presented as a new patient to her gynecologist with complaints of irregular menses. A pelvic ultrasound showed ascites and the ovaries appeared heterogenous with irregular borders. A CA125 was 432. The patient was taken to the operating room by gynecologic oncology for a diagnostic laparoscopy. Biopsies were taken and final pathology resulted as “diffuse granulomatous inflammation.” Post-operatively, the etiology remained unknown. The patient was brought back to the office for more testing. She tested positive for Chlamydia and was diagnosed with pelvic inflammatory disease.

Conclusion

When encountering granulomatous pathology, Chlamydia Trachomatis is a rare etiology however it should be included on the differential diagnosis.

1. Introduction

Granulomatous inflammation is form of chronic inflammation produced as a response to various conditions. It is defined by the presence of mononuclear leukocytes which respond to chemical mediators of cell injury (Shah et al., 2017). Typically, granulomatous inflammation histology includes activated histiocytes which may form multinucleated giant cells. There are multiple forms of granulomatous inflammation including foreign body, necrotizing, non-necrotizing suppurative, and histiocytic. Culture is the gold standard for the diagnosis of the etiology (Shah et al., 2017). This case provides an interesting diagnosis of Chlamydia Trachomatis presenting with ascites and granulomatous peritonitis.

2. Case

A 23 year-old G0 presented as a new patient to her gynecologist with complaints of irregular menses for 3–4 months. Patient was concerned as her periods were getting heavier and lasting longer. She also complained of metrorrhagia for two months. She denied cramping or pain. The patient was not on birth control at this time. She was sexually active and denied history of sexually transmitted infections. She did not have any pertinent past medical or surgical history. Family history included cervical cancer and skin cancer in her mother and maternal grandfather. Her maternal great grandmother and grandmother had BRCA positive breast cancer. Her mother was never tested. She had not been out of the country in the past 2 years but had travelled to Mexico and the Dominican Republic prior to this. Her physical exam revealed abdominal distention but was otherwise normal.

Her initial work-up included a pregnancy test, complete blood count, thyroid studies, estradiol, and transvaginal ultrasound. Her pregnancy test was negative in the office. An office transvaginal ultrasound showed an anteverted uterus with 1.9 mm endometrial stripe and a large amount of ascites was noted in the pelvis and abdomen. The ovaries appeared heterogenous with irregular borders. A CA125 was elevated at 432. CT scan revealed a large amount of ascites present throughout the abdomen and pelvis. There was an extensive omental cake formation present extending as far cephalad as the left upper quadrant near the anterior margin of the spleen. Normal appearing right ovarian tissue was present, symmetric with the left. However, there was an additional paraovarian process at the right adnexa with a different enhancement pattern measuring up to 5.3 cm which was concerning for a paraovarian mass. The uterus and adnexa otherwise appeared unremarkable. There was no lymphadenopathy identified. The patient was sent for a paracentesis, which removed 3900 mL of serous fluid. Cytology resulted with T-cells and polytypic B-cells; negative for acute inflammatory cells. Aerobic and anaerobic cultures had no growth after 5 days.

Due to the abnormal imaging and elevated CA125, she was then referred to Gynecology Oncology. At initial visit with Gynecology Oncology, germ cell tumor markers including AFP, LDH, Inhibin A and Inhibin B were obtained as well as CEA. These resulted within normal limits. Given negative cytology and concern for malignancy, the patient was taken to the operating room for a diagnostic laparoscopy.

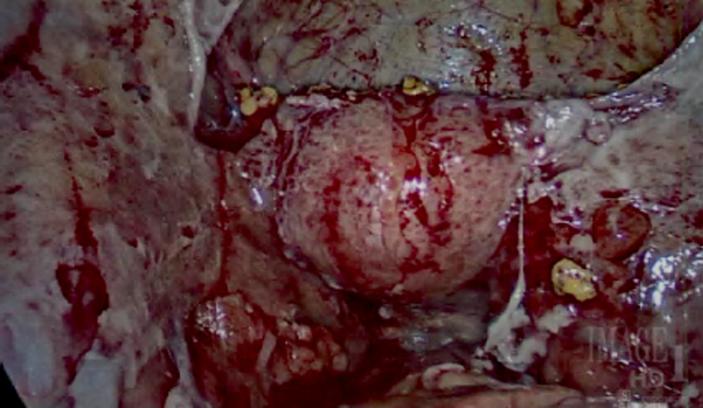

A diagnostic laparoscopy was performed and the patient was noted to have dense adhesions between the uterus and the bladder. The fimbriated ends of her fallopian tubes were densely adherent to the peritoneal cavity. Over the abdomen and pelvis, there were thick inflammatory exudates (Fig. 1). The liver and gallbladder were adherent to the anterior abdominal wall. No masses were visualized. The ovaries were unable to be visualized. Intraoperative biopsies of these lesions were taken and sent to pathology for intraoperative consult. Frozen section diagnosis was reported as “granulomatous inflammation”.

Fig. 1.

Pelvis with thick inflammatory exudates.

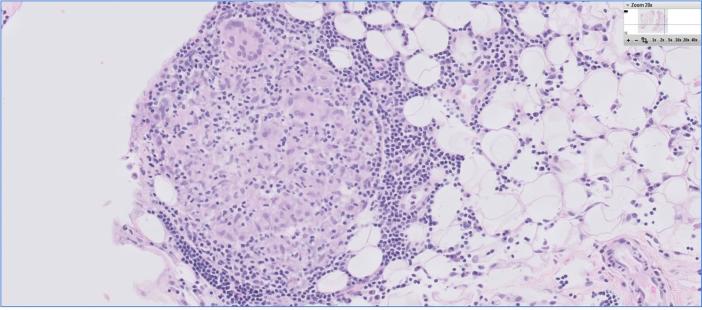

The etiology after the procedure was unknown. Based on the patient’s intraoperative pathology results, Mycobacterium tuberculosis was first in the differential diagnosis. The patient’s final pathology resulted as “diffuse granulomatous inflammation with reactive mesothelial cell hyperplasia, lymphocytosis, histiocytosis, and multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 2).” Grocott's methenamine silver stain and acid fast stains were performed and were negative for fungal and acid fast organisms. A gram stain was not performed. Aerobic and anaerobic cultures resulted as negative.

Fig. 2.

Pathology slides demonstrating diffuse granulomatous inflammation with reactive mesothelial cell hyperplasia, lymphocytosis, histiocytosis, and multinucleated giant cells.

The case was discussed with pathology as possibly an infectious etiology versus autoimmune etiology. The definitive diagnosis was unknown. The patient was brought back to the office to discuss OR findings as well as to perform additional testing. Cervical swabs for gonorrhea, chlamydia, and trichomonas were collected for molecular testing and possible identification. Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Trichomonas vaginalis Amplified RNA were performed. Human immunodeficiency virus, tuberculosis skin test, anti-neutrophilic antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, extractable nuclear antigen panel, angiotensin converting enzyme level and chest CT were also ordered. Fungal immunodiffusion as well as complement fixation were performed to test for other fungal antibodies.

Of the collected molecular assays, a positive result returned with confirmation of Chlamydia trachomatis. The patient was diagnosed with extensive pelvic inflammatory disease. The patient was treated with oral Doxycycline 200 mg delayed release daily for 14 days and one dose of Rocephin 250 mg intramuscularly. Expedited partner therapy was also prescribed. Post-treatment, the patient did well. She did require another paracentesis for reaccumulated ascites during her treatment. Seven hundred milliliters of serosanguinous fluid was removed which resulted as “reactive mesothelial cells, lymphocytes, and a few atypical cells.” She had a negative test of cure 31 days after treatment. She is now having regular periods and has fully recovered at this time.

3. Comment

This case provides a rare presentation of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) as granulomatous peritonitis and ascites. Pelvic ascites with Chlamydia trachomatis has been previously described in the literature. With Chlamydia, exudative ascites with high protein content is a common finding with major cell components are lymphocytes (Suzuki et al., 2004).

As noted earlier, granulomatous inflammation histology includes activated histiocytes which may form multinucleated giant cells (Shah et al., 2017). There is very limited literature on granulomatous disease correlated with Chlamydia. Granulomas have been described for Chlamydia proctitis in homosexual men (Quinn et al., 1981). Biopsies with L2 strains revealed diffuse inflammation with ‘crypt abscesses, granulomas, and giant cells’. These clinically resembled Crohns disease. One case of necrotizing granulomas of the cervix was published in 1980 which was due to Chlamydia (Christie and Kreiger, 1980). This was found on colposcopy and showed “collagenous necrosis surrounded by radially arranged palisaded histiocytes and fibroblasts”. One similar case demonstrated a 38 year-old with ascites and adnexal mass suspicious for malignancy. Peritoneal biopsies showed with a “chronic-active inflammation with numerous plasma cells and eosinophilic granulocytes” (Brun et al., 2017). The patient was positive for cervical Chlamydia cultures. Ascitic fluid was sent to pathology and showed many lymphocytes and histiocytes as well as few neutrophil granulocytes which is similar pathology to this case.

This case prompts us to add Chlamydia to the differential diagnosis when encountering granulomatous disease in the future. Few case reports are published demonstrating Chlamydia in the differential diagnosis when patient’s present with ascites and elevated CA125. Cervical cultures are easy and can aid in an important diagnosis.

Author contribution

Katelyn Tondo-Steele did the literature review and wrote the original article. Dr. Kellie Rath was the primary surgeon who also contributed, edited, and addended the article. Dr. Leo Niemeier was the primary pathologist who also edited and addended the article.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Brun R., Hutmacher J., Fink D., Imesch P. Erroneously suspected ovarian cancer in a 38-year-old woman with pelvic inflammatory disease and chlamydia. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/2514613. 2514613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie A., Kreiger H. Indolent necrotizing granulomas of the uterine cervix, possibly related to chlamydial infection. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecology. 1980;136(v7):958–960. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(80)91060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn T., Corey L., Chaffee R., Schuffler M., Brancato F., Holmes K. The etiology of anorectal infrections in homosexual men. Am. J. Med. 1981;71:395–406. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(81)90167-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah K., Pritt B., Alexander M. Histopathologic review of granulomatous inflammation. J. Clin. Tubercul. Other Mycobacterial Dis. 2017;7:112. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T., Shibahara H., Kikuchi K., Hirano Y., Takamizawa S., Suzuki M. Successful pregnancy following conservative treatment of massive ascites associated with acute Chlamydia trachomatis peritonitis. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2004;3(4):217–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0578.2004.00070.x. Published 2004 Dec 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]