Abstract

On 5 February 2020, in Yokohama, Japan, a cruise ship hosting 3,711 people underwent a 2-week quarantine after a former passenger was found with COVID-19 post-disembarking. As at 20 February, 634 persons on board tested positive for the causative virus. We conducted statistical modelling to derive the delay-adjusted asymptomatic proportion of infections, along with the infections’ timeline. The estimated asymptomatic proportion was 17.9% (95% credible interval (CrI): 15.5–20.2%). Most infections occurred before the quarantine start.

Keywords: corona, COVID-19, outbreak, Japan, asymptomatic, quarantine

An outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) unfolded on board a Princess Cruises’ ship called the Diamond Princess. Shortly after arriving in Yokohama, Japan, this ship had been placed under quarantine orders from 5 February 2020, after a former passenger had tested positive for the virus responsible for the disease (i.e. severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SARS-CoV-2), subsequent to disembarking in Hong Kong. In this study, we conducted a statistical modelling analysis to estimate the proportion of asymptomatic individuals among those who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 on board the ship until 20 February 2020 included, along with their times of infections. The model accounted for the delay in symptom onset and also for right censoring, which can occur due to the time lag between a patient’s examination and sample collection and the development of illness.

Epidemiological description and data

By 21 February 2020, 2 days after the scheduled 2-week quarantine came to an end, a total of 634 people including one quarantine officer, one nurse and one administrative officer tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. These individuals were among a total of 3,711 passengers and crew members on board the vessel.

Laboratory testing by PCR had been conducted, prioritising symptomatic or high-risk groups.

Daily time series of laboratory test results for SARS-CoV-2 (both positive and negative), including information on presence or absence of symptoms from 5 February 2020 to 20 February 2020 were extracted from secondary sources [1]. The reporting date, number of tests, number of persons testing positive by PCR (i.e. cases) and number of symptomatic and asymptomatic cases at the time of sample collection are provided, while the time of infection and true asymptomatic proportion are not available.

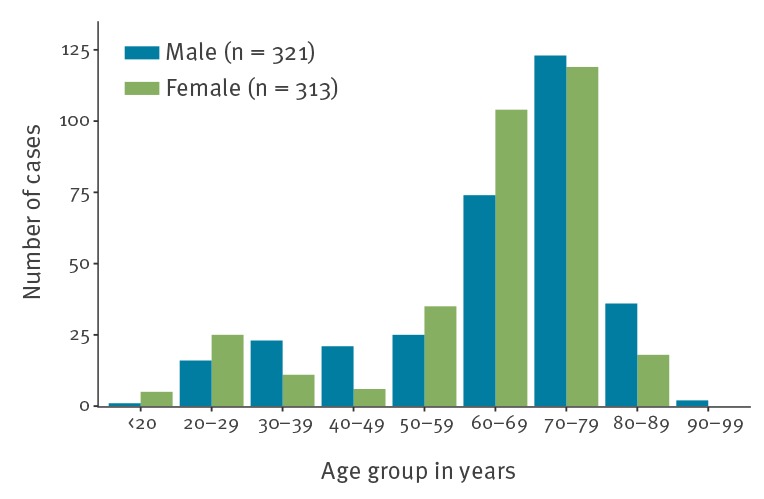

A total of 634 people tested positive among 3,063 tests as at 20 February 2020. Of 634 cases, a total of 313 cases were female and six were aged 0–19 years, 152 were aged 20–59 years and 476 were 60 years and older (Figure). Cases were from a total of 28 countries, with most being nationals of six countries, namely Japan (n = 270 cases), the United States (n = 88 cases), China (n = 58 cases; including 30 from Hong Kong), the Philippines (n = 54 cases), Canada (n = 51 cases) and Australia (n = 49 cases).

Figure.

Age distribution of reported coronavirus disease 2019 cases on board the Diamond Princess cruise ship stratified by sex, Yokohama, Japan, 20 February 2020 (n = 634 cases)

Of the 634 confirmed cases, a total of 306 and 328 were reported to be symptomatic and asymptomatic, respectively. The proportion of asymptomatic individuals appears to be 16.1% (35/218) before 13 February, 25.6% (73/285) on 15 February, 31.2% (111/355) on 16 February, 39.9% (181/454) on 17 February, 45.4% (246/542) on 18 February, 50.6% (314/621) on 19 February and 50.5% (320/634) on 20 February (Table). Soon after identification of the first infections, both symptomatic and asymptomatic cases were transported to designated medical facilities specialised in infectious diseases in Japan. However, these patients were treated as external (imported) cases, and a detailed description of their clinical progression is not publicly available.

Table. Data on characteristics, test results for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, and disembarking of passengers and crew of the Diamond Princess cruise ship, Yokohama, Japan, February 2020 (n = 3,711).

| Date (2020)a | Number of passengers and crew members on board | Number of disembarked passengers and crew members (cumulative) | Number of tests | Number of tests (cumulative) | Number of individuals testing positive | Number of individuals testing positive (cumulative) | Number of symptomatic cases | Number of asymptomatic cases | Number of asymptomatic cases (cumulative) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 Feb | 3,711 | NA | 31 | 31 | 10 | 10 | NA | NA | NA |

| 6 Feb | NA | NA | 71 | 102 | 10 | 20 | NA | NA | NA |

| 7 Feb | NA | NA | 171 | 273 | 41 | 61 | NA | NA | NA |

| 8 Feb | NA | NA | 6 | 279 | 3 | 64 | NA | NA | NA |

| 9 Feb | NA | NA | 57 | 336 | 6 | 70 | NA | NA | NA |

| 10 Feb | NA | NA | 103 | 439 | 65 | 135 | NA | NA | NA |

| 11 Feb | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 12 Feb | NA | NA | 53 | 492 | 39 | 174 | NA | NA | NA |

| 13 Feb | NA | NA | 221 | 713 | 44 | 218 | NA | NA | NA |

| 14 Feb | 3,451 | 260b | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 15 Feb | NA | NA | 217 | 930 | 67 | 285 | 29 | 38 | 73c |

| 16 Feb | NA | NA | 289 | 1,219 | 70 | 355 | 32 | 38 | 111 |

| 17 Feb | 3,183 | 528b | 504 | 1,723 | 99 | 454 | 29 | 70 | 181 |

| 18 Feb | NA | NA | 681 | 2,404 | 88 | 542 | 23 | 65 | 246 |

| 19 Feb | NA | NA | 607 | 3,011 | 79 | 621 | 11 | 68 | 314 |

| 20 Feb | NA | NA | 52 | 3,063 | 13 | 634 | 7 | 6 | 320 |

NA: data not available.

a Reported date.

b As this is a cumulative number, the exact date of disembarking is unavailable.

c As this is a cumulative number, the reported date for 35 asymptomatic cases are unavailable.

The asymptomatic proportion was defined as the proportion of asymptomatically infected individuals among the total number of infected individuals.

Statistical modelling

Here, we describe the statistical model that was employed to estimate the asymptomatic proportion using the time-series dataset described above.

The reported asymptomatic cases consists of both true asymptomatic infections and cases who had not yet developed symptoms at the time of data collection but became symptomatic later, i.e. the data are right censored. Each datum consists of an interval of time during which the individual may have been infected and a binary variable indicating whether they were symptomatic as at 18 February.

For individual i let [ai , bi] denote the interval during which they may have been infected and c represents the censor date of observation of being symptomatic. The (unknown) time at which individual i was infected is denoted Xi and, if they develop symptoms, let Di denote the delay from the time of infection until the time they are symptomatic, with cumulative density function (CDF), F D. The asymptomatic proportion, p, is the probability an individual will never develop symptoms.

Given an individual was exposed during the interval [ai , bi] the probability for them being asymptomatic at time c is

Given they were infected at time x for some a ≤ x ≤ b. Since the natural history of each individual’s infection is independent, the likelihood function is just the product of the g(X i, p) for each individual. Previous work on COVID-19 suggests that the distribution of the delay, D, between infection and onset of symptomatic infection (i.e. the incubation period) follows a Weibull distribution, with a mean and standard deviation at 6.4 and 2.3 days [2].

The observations were treated as survival data with right censoring. The probability of being asymptomatic given infection along with the infection time of each individual were estimated in a Bayesian framework using Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) algorithm. A detailed description of the model used and the computation is provided in the Supplementary material.

Findings from the real-time outbreak analysis

The posterior median estimate of the true proportion of asymptomatic individuals among the reported asymptomatic cases is 0.35 (95% credible interval (CrI): 0.30–0.39), with the estimated total number of the true asymptomatic cases at 113.3 (95%CrI: 98.2–128.3) and the estimated asymptomatic proportion (among all infected cases) at 17.9% (95%CrI: 15.5–20.2%).

We conducted sensitivity analyses to examine how varying the mean incubation period between 5.5 and 9.5 days affects our estimates of the true asymptomatic proportion. Estimates of the true proportion of asymptomatic individuals among the reported asymptomatic cases are somewhat sensitive to changes in the mean incubation period, ranging from 0.28 (95%CrI: 0.23–0.33) to 0.40 (95%CrI: 0.36–0.44), while the estimated total number of true asymptomatic cases range from 91.9 (95%CrI: 75.2–108.7) to 130.8 (95%CrI: 117.1–144.5) and the estimated asymptomatic proportion ranges from 20.6% (95%CrI: 18.5–22.8%) to 39.9% (95%CrI: 35.7–44.1%).

Heat maps were used to display the density distribution of infection timing by individuals (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2) where the vertical line corresponds to the date of 5 February 2020. Among the symptomatic cases, the infection timing appears to have occurred just before or around the start of the quarantine period (Supplementary Figure S1), while the infection timing for asymptomatic cases appears to have occurred well before the start of the quarantine period (Supplementary Figure S2).

Discussion

Since COVID-19 emerged in the city of Wuhan, China, in December 2019, thousands of people have died from SARS-CoV-2, especially in the Province of Hubei. Meanwhile hundreds of imported and resulting secondary cases have been reported in multiple countries as at 29 February 2020 [3].

The clinical and epidemiological characteristics of COVID-19 continue to be investigated as the virus further transmits through the human population [2,4]. While reliable estimates of the reproduction number and the death risk associated with COVID-19 are crucially needed to guide public health policy, another key epidemiological parameter that could inform the intensity and range of social distancing strategies to combat COVID-19 is the asymptomatic proportion, which is broadly defined as the proportion of asymptomatic infections among all the infections of the disease. Indeed, the asymptomatic proportion is a useful quantity to gauge the true burden of the disease and better interpret estimates of the transmission potential. This proportion varies widely across infectious diseases, ranging from 8% for measles and 32% for norovirus infections up to 90–95% for polio [5-7]. Most importantly, for measles and norovirus infections, it is well established that asymptomatic individuals are frequently able to transmit the virus to others [8,9]. Currently, there is no clear evidence that COVID-19 asymptomatic persons can transmit SARS-CoV-2, but there is accumulating evidence indicating that a substantial fraction of SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals are asymptomatic [10-12].

As an epidemic progresses over time, suspected cases are examined and tested for the infection using laboratory diagnostic methods. Then, time-stamped counts of the test results stratified according to the presence or absence of symptoms at the time of testing are often reported in near real-time. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the estimation of the asymptomatic proportion needs to be handled carefully since real-time outbreak data are influenced by the phenomenon of right censoring.

In this study, we conducted statistical modelling analyses on publicly available data to elucidate the asymptomatic proportion, along with the time of infection among the COVID-19 cases on board the Diamond Princess cruise ship.

Our estimated asymptomatic proportion is at 17.9% (95%CrI: 15.5–20.2%), which overlaps with a recently derived estimate of 33.3% (95% confidence interval: 8.3–58.3%) from data of Japanese citizens evacuated from Wuhan [13]. Considering the reported similarity in viral loads between asymptomatic and symptomatic patients [14] and that transmission of SARS-CoV-2 by asymptomatic or paucisymptomatic cases may be possible, even though there is no clear evidence as yet of asymptomatic transmission, the relatively high proportion of asymptomatic infections could have public health implications. For instance, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that contacts of asymptomatic cases self isolate for 14 days [15].

Most of the infections on board the Diamond Princess cruise ship appear to have occurred before or around the start of the 2-week quarantine that started on 5 February 2020, which further highlights the potent transmissibility of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, especially in confined settings. To further mitigate transmission of COVID-19 and bring the epidemic under control in areas with active transmission, it may be necessary to minimise the number of gatherings in confined settings.

Our study is not free from limitations. First, laboratory tests by PCR were conducted focusing on symptomatic cases especially at the early phase of the quarantine. If asymptomatic cases were missed as a result of this, it would mean we have underestimated the asymptomatic proportion. Second, it is worth noting that the passengers and crew whose data were employed in our analysis do not constitute a random sample from the general population. Considering that most of the passengers were 60 years and older, the nature of the age distribution may lead to underestimation if older individuals tend to experience more symptoms. An age standardised asymptomatic proportion would be more appropriate in that case. Third, the presence of symptoms in cases with COVID-19 may correlate with other factors unrelated to age including prior health conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and/or immunosuppression. Therefore, more detailed data documenting the baseline health of the individuals including the presence of underlying diseases or comorbidities would be useful to remove the bias in estimates of the asymptomatic proportion.

In summary, we have estimated the proportion of asymptomatic cases among individuals who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 along with the times of infection of confirmed cases on board the Diamond Princess cruise ship after adjusting for the delay in symptom onset and right censoring of the observations.

Acknowledgements

Funding statement

KM acknowledges support from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Number 18K17368 and from the Leading Initiative for Excellent Young Researchers from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sport, Science & Technology of Japan. KK acknowledges support from the JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 18K19336 and 19H05330. AZ acknowledges supports from the Oxford Martin School Programme on Pandemic Genomics. GC acknowledges support from NSF grant 1414374 as part of the joint NSF-NIH-USDA Ecology and Evolution of Infectious Diseases program.

Supplementary Data

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Authors’ contributions: KM conceived and designed the early study idea, collected data and implemented statistical analysis. KM and KK built the model. KM wrote the first full draft. KM, KK, AZ and GC contributed to the interpretation of the results. KK, AZ and GC edited and commented on several earlier versions of the manuscript. GC provided supervision.

References

- 1.Ministry of Health. Labour and Welfare, Japan. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Situation Report in Japan. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. Japanese. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/0000164708_00001.html

- 2. Backer JA, Klinkenberg D, Wallinga J. Incubation period of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infections among travellers from Wuhan, China, 20-28 January 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(5). 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.5.2000062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports. Geneva: WHO. [Accessed Mar 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports

- 4.Linton NM, Kobayashi T, Yang Y, Hayashi K, Akhmetzhanov AR, Jung SM, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of novel coronavirus infection: A statistical analysis of publicly available case data. medRxiv. 2020.01.26.20018754; (Preprint). 10.1101/2020.01.26.20018754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5. Kroon FP, Weiland HT, van Loon AM, van Furth R. Abortive and subclinical poliomyelitis in a family during the 1992 epidemic in The Netherlands. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20(2):454-6. 10.1093/clinids/20.2.454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mbabazi WB, Nanyunja M, Makumbi I, Braka F, Baliraine FN, Kisakye A, et al. Achieving measles control: lessons from the 2002-06 measles control strategy for Uganda. Health Policy Plan. 2009;24(4):261-9. 10.1093/heapol/czp008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smallman-Raynor MR, Cliff AD, editors. Poliomyelitis: Emergence to Eradication. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006;32. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Miura F, Matsuyama R, Nishiura H. Estimating the Asymptomatic Ratio of Norovirus Infection During Foodborne Outbreaks With Laboratory Testing in Japan. J Epidemiol. 2018;28(9):382-7. 10.2188/jea.JE20170040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mizumoto K, Kobayashi T, Chowell G. Transmission potential of modified measles during an outbreak, Japan, March‒May 2018. Euro Surveill. 2018;23(24). 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.24.1800239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team [The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41(2):145-51. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hoehl S, Rabenau H, Berger A, Kortenbusch M, Cinatl J, Bojkova D, et al. Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Returning Travelers from Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 2020;41(2):NEJMc2001899. 10.1056/NEJMc2001899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497-506. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishiura H, Kobayashi T, Miyama T, Suzuki A, Jung S, Hayashi K, et al. Estimation of the asymptomatic ratio of novel coronavirus infections (COVID-19). medRxiv. 17 Feb 2020. 10.1101/2020.02.03.20020248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14. Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, Liang L, Huang H, Hong Z, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Viral Load in Upper Respiratory Specimens of Infected Patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;41(2):NEJMc2001737. 10.1056/NEJMc2001737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Interim US Guidance for Risk Assessment and Public Health Management of Persons with Potential Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Exposure in Travel-associated or Community Settings. Atlanta: CDC. [Accessed 2 Mar 2020]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/php/risk-assessment.html

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.