Abstract

Background/Aim: Differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN) and lichen sclerosus (LS) can give rise to vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (VSCC), but genetic evidence is currently still limited. We aimed to determine genetic abnormalities in VSCC and backtrack these abnormalities in the dVIN and LS lesions. Materials and Methods: DNA from VSCC and patient-matched dVIN and LS samples of twelve patients was collected. High-resolution genome-wide copy number analysis was performed and subsequently, we sequenced TP53. Results: Copy number alterations were identified in all VSCC samples. One dVIN lesion presented with three copy number alterations that were preserved in the paired VSCC sample. Targeted sequencing of TP53 identified mutations in five VSCCs. All five mutations were traced back in the dVIN (n=5) or the LS (n=1) with frequencies ranging from 3-19%. Conclusion: Our data provide genetic evidence for a clonal relationship between VSCC and dVIN or LS.

Keywords: Vulvar cancer, vulvar neoplasms, squamous cell carcinoma, lichen sclerosus, vulvar lichen sclerosus, differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, clonal evolution

Vulvar cancer is the fourth most common cancer affecting the female genital tract and has an increasing incidence of 2.5/100,000 women per year (1). Approximately 80% of all vulvar cancers are of squamous origin and can develop following two different pathways (2,3). The minority of vulvar squamous cell carcinomas (VSCC) is caused by a persistent infection with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV), inducing the precursor high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL); the oncogenesis of HPV-related VSCC resembles the development of cervical cancer. The second and most common type of VSCC is non HPV-related and accounts for over 80% of all VSCC (4,5). These carcinomas arise in a background of the chronic inflammatory vulvar skin disease Lichen Sclerosus (LS) and/or differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN). The exact role of LS and dVIN in the development of VSCC is not yet known, but patients with LS have a lifetime risk of 4-5% to develop VSCC (6).

There is clinical evidence that dVIN is the precursor lesion of the non HPV-related pathway (7). We showed that of all VIN lesions diagnosed in the Netherlands between 1992 and 2005, only a minority were dVIN in comparison to HSIL; apparently dVIN is rarely found as a solitary lesion (8). Remarkebly, dVIN is present on the majority of the non HPV-related VSCCs (4,5). This discrepancy, low incidence of solitary dVIN lesions, but high incidence of dVIN adjacent to VSCC, can be explained by the fact that diagnosis of dVIN is clinically and histopathologically difficult (9) with an assumed short intraepithelial phase, which suggests that dVIN is possibly suffering from underdiagnosis (10). On the other hand, it has been hypothesised that dVIN is a border phenomenon of VSCC (11). Though the oncogenesis has not been fully clarified, there are strong indications that dVIN is a precursor lesion; in recent years the incidence of solitary dVIN is increasing (8) and dVIN is more often found in revised biopsies previously diagnosed as LS in patients that later developed VSCC (10). Furthermore, first indications for a genetic correlation between VSCC, dVIN and LS were reported by Nooij et al. (12).

Few studies have investigated genetic abnormalities in non HPV-related VSCC, and showed a frequent occurrence of TP53 mutations (13-15). The upcoming techniques to search for genetic changes are promising to provide more information on the aetiology of (pre)malignant vulvar lesions. However, the literature on this topic is limited in vulvar (pre)malignancies. In theory, tumours arise from a multistep process of accumulated genetic alterations (16). The identification of chromosomal regions most frequently affected by copy number alterations or sequence mutations may be relevant for determining the relationship between LS, dVIN and VSCC.

We hypothesise that LS and dVIN are lesions already showing early neoplastic alterations that are also present in VSCC together with other accumulating events. In order to provide information on the mutations that can be found in VSCC and provide more evidence for a clonal relation between LS, dVIN and VSCC, we aimed to determine genetic abnormalities in VSCC of 12 patients and backtrack these abnormalities in the dVIN and LS precursor lesions.

Materials and Methods

Tissue samples. Twelve patients with a primary VSCC who were primarily surgically treated between 2008 and 2014 in the Radboud university medical center Nijmegen, the Netherlands, were included. Inclusion criteria were: a history of LS, presence of dVIN in the surgical excision specimen, non HPV-related tumour, and no previous radiotherapy or chemotherapy. Clinical data of included patients was retrieved.

To select for non HPV-related VSSCs, we used the p16INK4A expression of the tumour in combination with HPV status and morphologic criteria on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained slides. Tumours were considered as non HPV-related if p16 staining was negative, dVIN and LS were present, independent of HPV status, or if the HPV status was negative in combination with the presence of dVIN and LS.

For this study, coded residual tissue was used, which was retrieved during regular treatment. According to the Dutch law, no specific patient approval is necessary for the use of this material. This study was approved by the local ethical committee (CMO Regio Arnhem-Nijmegen; registration number 2015-1808) and performed according to the Code for Proper Secondary Use of Human Tissue (Dutch Federation of Biomedical Scientific Societies (htpp://federa.org).

Microdissection and DNA extraction. The H&E stained slides of the surgical excision specimen were reviewed by an expert gynaecopathologist; areas with LS, dVIN and VSCC were identified. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) blocks were retrieved and re-cut at 5 μm. The last re-cut slide was H&E stained and compared with the original slide in order to confirm that the lesion was still present. Tumour cells were collected through removal of VSCC and dVIN tissue by scraping with a clean scalpel from several unstained slide sections. DNA was isolated with TET-lysis buffer (10 mmol/l Tris-HCl, pH 8.5; 1 mmol/l EDTA, pH 8; 0.1% Tween-20) containing 5% Chelex-100 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Protein digestion was performed by adding 20 μl of proteinase K to each sample following incubation at 56˚C for 48 h. Fresh proteinase K of 10 μl was added after 24 h. Next, DNA was denatured by heat inactivation at 95˚C for ten minutes. The samples were centrifuged for ten minutes at 14.000 rpm (RT) and measured by Picogreen measurements (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Copy number profiling. Genome-wide copy number profiling was performed on DNA from six paired dVIN and VSCC lesions using FFPE-compatible Affymetrix Oncoscan arrays (OncoScan FFPE Express v.2; Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA), according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer (17-19). The data that passed quality control (MAPD value ≤0.6) were then analyzed using Nexus Copy Number Software Edition 7 (Biodiscovery, El Segundo, CA, USA) with NCBI build 37 of the human genome. The SNP-FASST2 Segmentation Algorithm was used. The significance threshold was set at 5.0E-7 with a minimum of 250 probes and a maximum contiguous spacing of 1,000 kb to define a segment. Thresholds for copy number gains and losses were set to 0.3 and –0.3, respectively. Thresholds for high-level amplifications and homozygous losses, indicating greater than a single copy number change were set at 1.2 and –1.2 respectively. The homozygous frequency threshold was set at 0.85 and the homozygous value threshold was set at 0.8 with a minimum loss of heterozygosity (LOH) requirement of 500 kb. The heterozygous imbalance threshold was set at 0.4. Allelic imbalance and LOH was only scored when larger than 15 Mb, and adjacent sequential calls of allelic imbalance and LOH were merged as one region upon visual inspection of the copy number and B-allele frequency plots. To allow comparison of VSCC copy number profiles with those of the dVIN samples, which were of poorer quality, we performed smoothening of the dVIN probe intensity values using a 15× running smoothing of the median (R package). Copy number plots of VSCC and smoothened dVIN data per chromosome were made using GenomeGraphs library 1.28.0 (20).

Targeted sequencing of TP53 using molecular inversion probes. For the targeted enrichment of genomic TP53 sequences we used single molecule Molecular Inversion Probes (smMIPs), which are 80-nt oligonucleotides with two targeting arms at the extreme ends that bind the genomic template in a strand specific manner, allowing strand specific amplification and double tiling. Each probe contains an 8-nt random molecular tag that enable the identification of unique captures from the generated sequencing reads, which is essential in the context of gDNA with low quality/quantity, and can correct for amplification bias (21). In addition, the molecular tag guided assembly into consensus reads diminishes the number of false positive variants due to PCR and sequencing artefacts and thus allows accurate detection of low-frequency variants. In total, 50 probes were designed that target >95% of coding and splice-sequences (–/+5 nt flanking exon-intron boundaries) in TP53. An equimolar pool of these 50 probes was tested and optimized on gDNA controls prior to sequencing of the samples. To prevent allelic drop-out at sites containing SNPs, identical smMIPs were designed for the major and minor alleles (referred to as ‘a’ and ‘b’). Targeted capture with smMIPs was performed as previously described (21,22). Shortly, 100 ng of genomic DNA in a pool containing 5'-phosphorylated smMIPs were annealed overnight to capture the targeted sequences of interest. After annealing, the gaps were closed in a 5’->3’ extension reaction, followed by a ligation step to create circular DNA. Uncircularised probes and remaining linear genomic DNA were removed by exonuclease treatment. Barcoded Illumina primers were incorporated in the PCR reaction, following amplification of all pooled samples. Subsequently, the barcoded library was sequenced using the Illumina NextSeq500 system, with 2×150-bp paired-end reads. We used SeqNext software (JSI Medical Systems; version 4.2.0) to map and align the reads, create unique consensus reads from PCR duplicates to minimise sequencing errors, and perform variant calling [relevant settings are described in (23)]. Identified mutations were validated by Sanger sequencing in LS, dVIN and VSCC samples from the same patient (primers available upon request).

Results

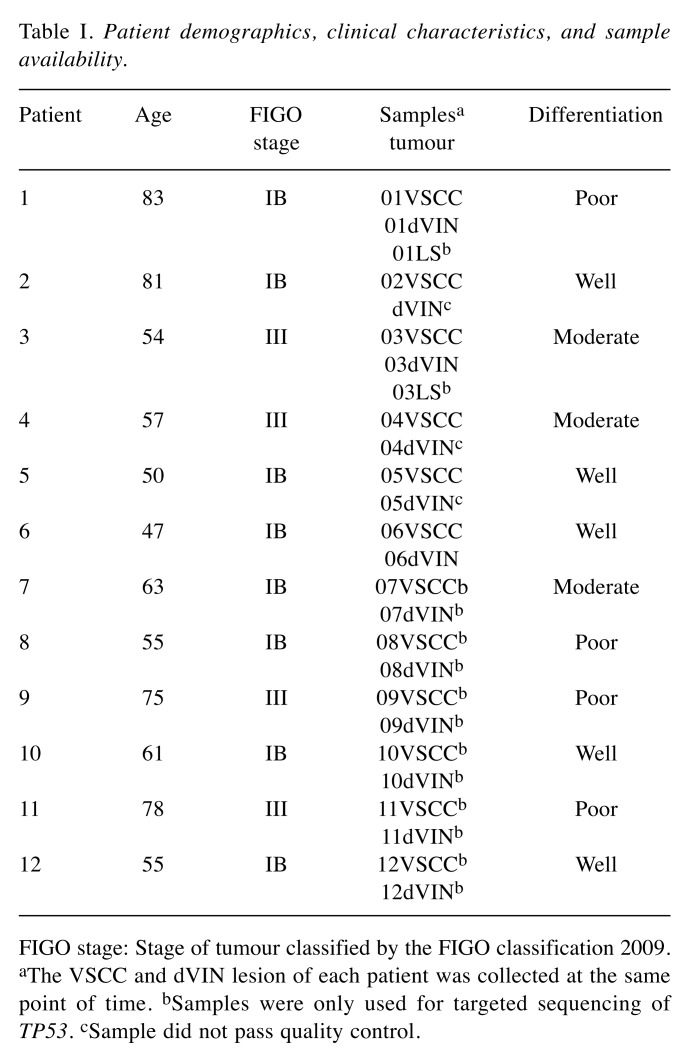

We included twelve patients with a non HPV-related VSCC, of which tissues of six patients were included for whole-genome copy number profiling. For each of the twelve included patients, a paired dVIN and VSCC sample was available, for two of them also an LS sample was available for analyses (Table I). The median age of our patients was 59 years (range 47-83 years). Eight patients (67%) had FIGO stage IB and four (33%) stage III disease. Five VSCCs were well differentiated (42%), three moderately differentiated (25%) and four poorly differentiated (33%).

Table I. Patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and sample availability.

FIGO stage: Stage of tumour classified by the FIGO classification 2009. aThe VSCC and dVIN lesion of each patient was collected at the same point of time. bSamples were only used for targeted sequencing of TP53. cSample did not pass quality control.

A preliminary version of this work has been published in a doctorate thesis which is available online at https://repository.ubn.ru.nl/bitstream/handle/2066/150172/150172.pdf?sequence=1, Chapter 2.

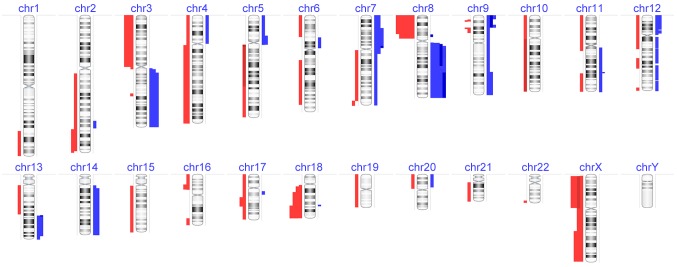

Chromosomal alterations in VSCC. The dVIN and VSCC samples of six patients were hybridised to Oncoscan arrays. All six VSCC samples generated copy number profiles that passed quality control and could be further analyzed. An overview of the distribution and number of gains and losses per patient per sample are displayed in Figure 1. In VSCCs, we identified a total of 94 copy number alterations. These alterations consisted of 55 losses and 39 gains, including 7 high-level amplifications. Overall, eleven genomic regions were affected by copy number alterations in three or more VSCCs. An overview of gains, losses and acquired uniparental disomy events per sample is available upon request.

Figure 1. Copy number alteration (CNA) profiles of six vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (VSCC) patients. Gains are indicated by the blue bars, and losses are shown by the red bars. Dark colors represent multi-copy gains and losses.

The most frequently found alteration was loss of chromosome 8p, present in all VSCC, followed by gain of chromosome 8q in five of six VSCCs, gain of chromosome 7p and loss of chromosome 18q, both present in four of six VSCCs. A complete overview of recurrently affected copy number regions is available upon request.

Seven high-level amplifications were seen in three of six VSCCs. Five of these encompassed large genomic regions (37-45 Mb), affecting many genes. The others were smaller (1-8 Mb) in size and contained known oncogenes including EGFR (7p21.1), FGFR1 (8p11.23), IL11-RA (9p13), and YAP1 (11q22.1).

Furthermore, 12 regions of allelic imbalance were identified, representing copy neutral homozygosity. These regions are known as acquired uniparental disomy, and frequently contain mutations in tumour suppressor genes that have become homozygous as a result of mitotic recombination. The regions were not completely homozygous, suggesting them to be present in a subset of the sample because of the presence of normal cells and/or tumour heterogeneity.

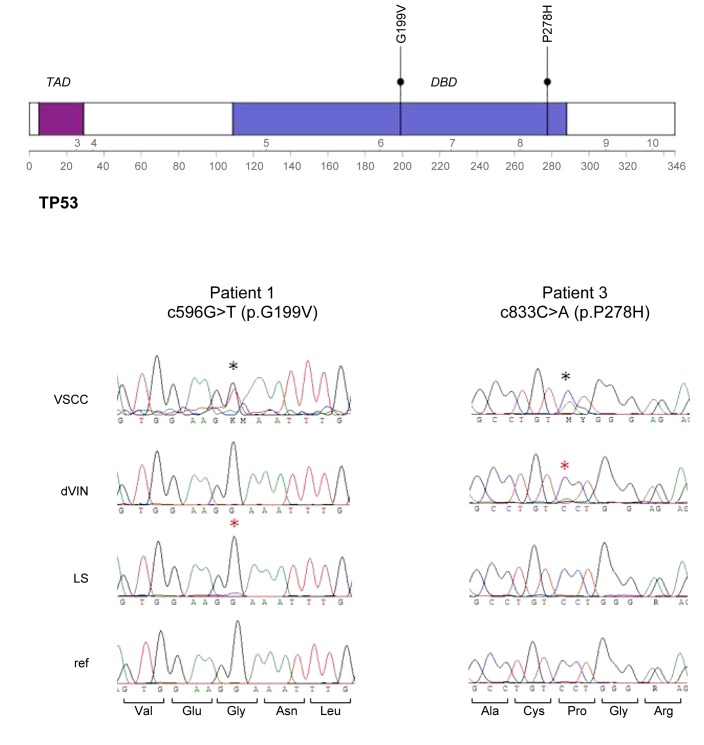

Interestingly, chromosome 17p encompassing, among other genes, the tumour suppressor gene TP53, was affected by acquired uniparental disomy in three VSCCs. Targeted sequencing of the TP53 gene using molecular inversion probes in two VSCC samples for which sufficient material remained indeed identified mutations in patient 1 (c.596G>T, p.Gly199Val) and patient 3 (c.833C>A, p.Pro278His). Both mutations were confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

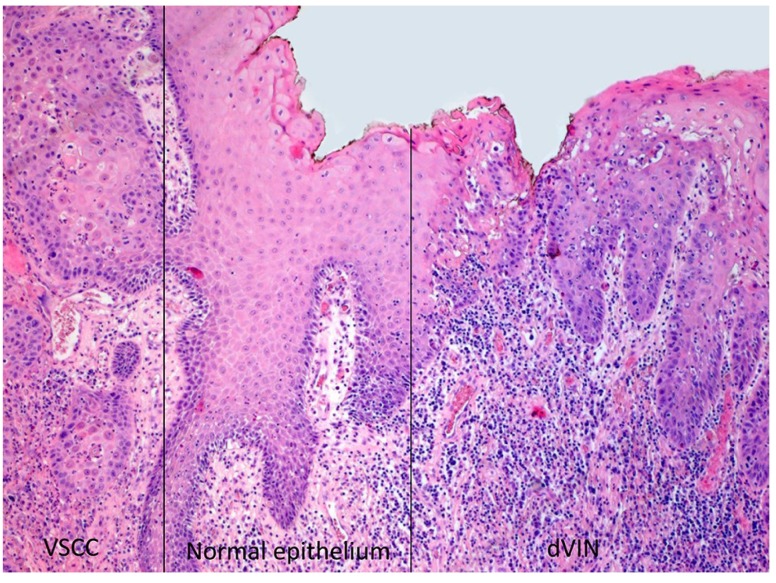

Clonal relationship between VSCC and dVIN. Next, we analysed whether the chromosomal abnormalities detected in the VSCC could already be detected in the paired dVIN samples. Three dVIN samples (patients 1, 3, and 6) passed quality control and could be further analysed. No copy number alterations were found the dVIN samples of patients 1 and 6. In contrast, three copy number alterations were detected in the dVIN sample of patient 3; a 54-year old female with a unifocal lesion of 2.5 cm on the left labium minus localized 1.5 cm left from the clitoris. Histopathological examination showed that the dVIN was located in the immediate surroundings of a moderately differentiated VSCC with presence of lymphovascular invasion, an invasion depth of 9.5 mm and a sentinel node with isolated tumour cells (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Histological overview of the epithelium of patient three; the area on the left side shows vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (VSCC), the area on the right side differentiated vulvar intra-epithelial neoplasia (dVIN). Micro-dissection was performed in these areas, there is a distance of 2 mm (normal epithelium) between both areas (original magnification ×50).

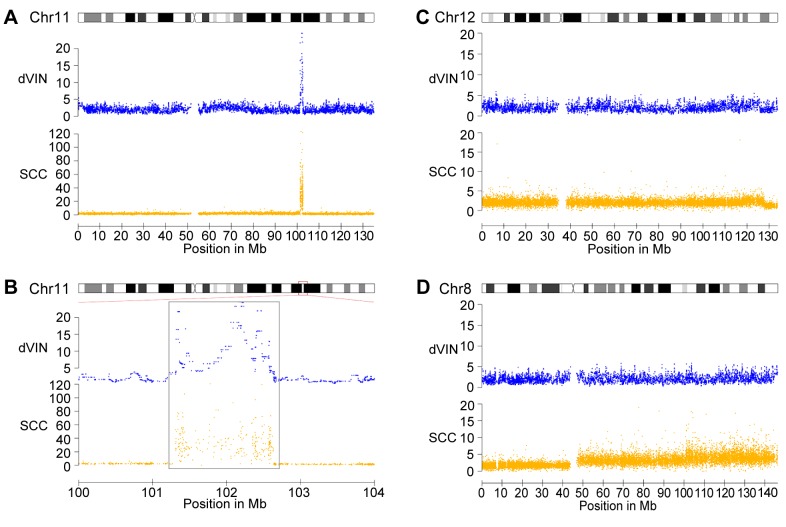

The copy number abnormalities in this dVIN included an amplification of 11q22 and a deletion at the telomeric region of 12q. Furthermore, chromosome 14 showed a higher median probe level, suggesting a gain of this entire chromosome. All these three copy number alterations were also detected in the paired VSCC sample. Detailed comparison between the dVIN and VSCC showed that the boundaries of the 11q22 amplification appeared identical, suggesting that this lesion is indeed preserved from dVIN (Figure 3A and B). The 12qter deletion was found to be larger (~1.9 Mb; 197 probes) in the dVIN sample compared to VSCC (Figure 3C), but the quality and amount of available DNA did not allow us to reveal whether this difference was due to a technical artefact or it indicates that the 12qter deletions have arisen independently in dVIN and VSCC. Importantly, the other copy number alterations detected in VSCC (five gains and 25 deletions), including an 8q22-q24.3 amplification (Figure 3D) could not be detected in the paired dVIN sample. In conclusion, the shared copy number alterations between the dVIN and VSCC in patient 3 provide genetic evidence for a clonal relationship between dVIN and VSCC.

Figure 3. Shared and different copy number abnormalities in differentiated VIN (dVIN) and vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (VSCC) of patient three. Shown are the high-level amplification on chromosome 11 (A and B) and the deletion of 12q-ter (C), which is shared between the two samples, and the copy number gains on chromosome 8, which is absent in dVIN (D). Detail of the amplification on chromosome 11 (B) shows that its boundaries are identical between the two samples.

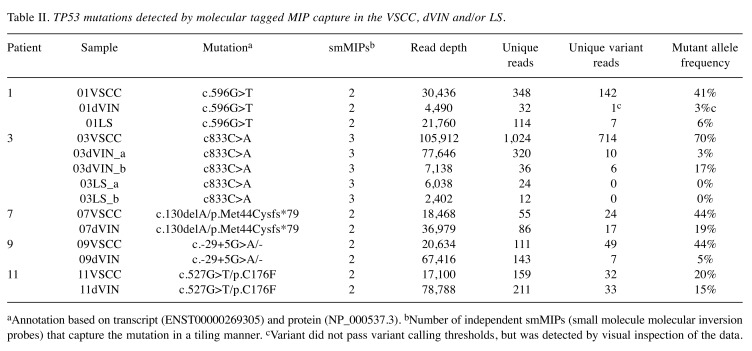

Subclonal TP53 mutations in dVIN and LS. A clonal relationship between VSCC and dVIN or LS can easily be missed if the alteration is present in only a subset of the cells. Since subclonal copy number alterations are difficult to detect, we next focused on point mutations using smMIP-based targeted deep-sequencing. This technology allows clustering of sequence reads derived from the same template to create so-called single molecule consensus reads (smc reads) (21,24) which have much lower error rates, hence creating higher specificity for detecting low-level mosaic mutations. We performed smMIP-based sequencing of VSCC samples from six additional patients for the TP53 gene as this gene is known as a recurrently mutated driver of VSCC.

Next to the mutations already found in patients 1 and 3, we identified three additional TP53 mutations in the VSCCs of patients 7, 9 and 11 (Table II). Next, we established whether these five TP53 mutations could be traced back in paired dVIN and LS samples. In all five patients, the TP53 mutations detected in the VSCC sample were also present in dVIN with variant allele frequencies ranging from 3 to 19% (Table II). In patient 1, the mutation was detected by only a single smc-read, likely due to the limited availability of material, which makes an estimate of the mutant allele frequency rather inaccurate. Interestingly, however, this mutation was also detected in the LS sample (6% of the reads), a finding that could be confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Figure 4). In conclusion, we demonstrated that in all five TP53-mutated VSCCs, the mutation could be detected at subclonal levels in dVIN or LS, thereby confirming a clonal relationship between these lesions in the respective patients.

Table II. TP53 mutations detected by molecular tagged MIP capture in the VSCC, dVIN and/or LS.

aAnnotation based on transcript (ENST00000269305) and protein (NP_000537.3). bNumber of independent smMIPs (small molecule molecular inversion probes) that capture the mutation in a tiling manner. cVariant did not pass variant calling thresholds, but was detected by visual inspection of the data.

Figure 4. Detection TP53 mutations in two vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (VSCC) samples and backtracking in differentiated vulvar intra-epithelial neoplasia (dVIN) and lichen sclerosus (LS). Top panel shows the TP53 protein with the transactivating domain (TAD) and the DNA-dinding domain (DBD) and the location of the two mutations. Below that are sequence chromatograms of each mutation in the respective samples. Mutations are indicated by a black (clonal) or red (subclonal) asteriks.

Discussion

We investigated genomic alterations of non HPV-related VSCC lesions and patient-matched dVIN lesions using genome-wide copy number profiling and targeted sequencing of TP53. We found that gains of 7p and 8q and losses of 8p and 18q were found in most VSCC lesions, and acquired uniparental disomy was common, including for chromosome 17p. In one patient, three of the 33 copy number alterations found in the VSCC sample were also detected in the paired dVIN sample including a high-level amplification on 11q22 and a deletion of 12qter. Furthermore, in five of the 12 patients (42%) we identified a TP53 mutation in a cellular subset of LS or dVIN, which was shared with the paired VSCC. We therefore conclude that, at least in five patients, the VSCC originate from single precursor cells in which a subset of the genetic alterations, possibly driving premalignant events, were already present in the dVIN and/or LS stage, after which additional alterations have resulted in the progression towards VSCC.

In patient 3, a clonal relationship between VSCC and dVIN was confirmed by several genomic aberrations, including shared copy number alterations and a TP53 mutation. The most pronounced aberration was a high gain on chromosome 11q23, which encompassed the BIRC and MMP gene clusters as well as the YES-associated protein 1 (YAP1) as a possible candidate gene. This latter gene is known to play a role in the development and progression of multiple cancers and may function as a potential target for cancer treatment (25). YAP1 expression seems to indicate a poor outcome in several cancer types (26,27). Future studies should reveal whether these aberrations are more common in dVIN lesions and are involved in the progression from dVIN towards VSCC. Importantly, the majority of copy number alterations, among which one high-level amplification, were found only in VSCC, and thus may have contributed to the progression towards VSCC. Another alteration preserved from dVIN was a mutation in TP53, which was found in low levels in this lesion and became homozygous in a major fraction of tumour cells in the VSCC.

Interestingly, TP53 mutations were detected in five patients (42%) and, in all cases, were shared between VSCC and dVIN. The mutant allele frequency of these mutations was always lower in the dVIN samples compared to VSCC, indicating that they were present in only a subset of the cells. Whether this low mosaicism was due to heterogeneity of the dVIN lesion or caused by a relatively high load of normal epithelial cells could not be established. In patients 1 and 3, the B-allele frequency plots showed homozygosity of the TP53 locus in the majority of cells due to acquired uniparental disomy. Our findings illustrate how the detection of acquired uniparental disomy facilitated the identification of TP53 mutations, but also provide insight into the role of these mutations during tumour progression: TP53 mutations can find their origin in precursor lesions, as was recently also demonstrated by others (12), and frequently become homozygous in VSCC.

One could question whether the copy number alterations found in the dVIN lesion in patient 3 were actually copy number alterations present in a subset of VSCC cells that were present in the dVIN biopsy. However, although the samples were taken from the same surgical excision specimen, cells for DNA were collected from a different site of the specimen. Furthermore, histological examination of the H&E stained slides (Figure 2) showed a distance of 2 mm with normal epithelium between the dVIN lesion and VSCC lesion. It is important to note that, due to the low copy number intensities in the dVIN sample of patient 3, and the relatively low signal-to-noise ratio, it might be possible that other aberrations detected in the VSCC sample were simply missed in the dVIN sample. Nevertheless, it is unlikely that the high-level amplification at 8q has been missed in dVIN (Figure 3), which indicates that the dVIN and VSCC samples share genomic alterations, but are not identical, thereby making it less likely that VSCC-derived cells were present in the dVIN sample.

Liegl and Regauer (11) suggested that the rare identification of dVIN without VSCC in their patient group raised the question whether dVIN should be considered a true precursor lesion of VSCC or whether it represents an in situ carcinoma component adjacent to an invasive VSCC. They suggested that the interpretation of dVIN as a precursor lesion needs to be carefully reconsidered. In general, epithelial disorders are found adjacent to VSCC in 70-80% of patients. However, evidence that some of these disorders are precursors of VSCC is circumstantial (7). Reason to question dVIN as being the precursor lesion is the low incidence of solitary dVIN compared to HSIL (8), while the majority of VSCCs are not HPV associated. However, this low incidence can also be explained by the difficulty of diagnosing dVIN which might result in an underdiagnosis (9), as well as by the existence of a shorter intra-epithelial phase compared to HSIL (8,28). Though there are no recent studies concerning the incidence of dVIN, we experience a higher incidence of solitary dVIN in daily practice because clinicians and pathologists are more aware of the diagnosis.

The number of studies that tried to find genetic similarities between dVIN and VSCC are small and mainly involve a low number of loci investigated (7,13,29). Furthermore, most studies do not differentiate between HSIL and dVIN-related VSCCs. Lin et al. (30) compared patterns of loss of heterozygosity between different locations of the tumour of one patient with a non HPV-related VSCC; the tumour itself scored positive for loss of heterozygosity in four of seven loci. Furthermore, one site of dVIN shared its locus with the invasive tumour whereas the other dVIN shared one of two loci with the VSCC. Normal epithelium and stroma showed no abnormalities. These results are suggestive for dVIN being a precursor lesion, though this conclusion is based on a single case and only seven genomic loci. Pinto et al. (31) compared 11 identified loci which scored positive for allelic imbalance in greater than 50% of cases from a prior study of VSCC (n=16) (32) to pre-invasive lesions (LS, HSIL, dVIN and hyperplasia). This comparison showed a lower percentage of allelic imbalance in pre-invasive lesions, though in this comparison no distinction was made between HPV-positive and -negative lesions. The advantage of our study is the high number of loci investigated in dVIN associated VSCC, which allows us to compare the whole genome of dVIN and VSCC which provides more detailed information.

A noticeable result is the median age of 59 years of the included patients. VSCC, especially non HPV-related VSCC, is a disease occurring in elderly patients.

In our study, two out of three dVIN samples analyzed by copy number profiling, did not show any copy number aberrations. This observation might be explained by a higher level of contamination with normal cells in these lesions compared to VSCC, or low yield and quality of the isolated DNA, which may have resulted in a decreased sensitivity to detect these aberrations. In addition, however, it is not unlikely that copy number alterations are simply less frequent in these lesions.

In order to provide more evidence for the hypothesis of clonal relationship between LS/dVIN and VSCC, the availability of sufficient material is essential. We experienced that retrieving enough DNA from FFPE-blocks for genome-wide profiling was challenging, and collection of fresh-frozen tissue for future studies is highly recommended. Fortunately, we were able to reveal additional support for our hypothesis by using smMIP-based targeted sequencing of TP53, which is frequently mutated in VSCC. This technology is highly suitable for fragmented (FFPE-derived) DNA, and highly sensitive for detecting mutations, even when present in a low percentage of cells. However, in order to obtain more information on the correlation between LS, dVIN and VSCC, whole exome or genome sequencing in a larger number of lesions might be essential, particularly because backtracking of small mutations is less challenging.

The findings of this study are relevant for anti-cancer research and therapy. We demonstrated a clonal relationship between dVIN and non HPV-related VSCC. This implies that dVIN should be considered as a precursor lesion. With this knowledge, clinicians and pathologists would be more aware of diagnosing dVIN. Early diagnosis and treatment of dVIN will lead to less invasive VSCC. Furthermore, our study identified chromosome aberrations in VSCC. As a result, candidate genes can be identified in the future which play a role in the development and progression of cancer and may function as a potential target for anti-cancer treatment.

In summary, we investigated the genome-wide aberrations in VSCC and its possible genetic relationship with dVIN and LS, and provided genetic evidence for a clonal relationship between LS, dVIN and VSCC in 42% of the patients, including all patients with TP53 mutated VSCC. These results will provide a basis for more comprehensive sequencing studies to identify genetic aberrations in precursor lesions that create a risk to the development of VSCC.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

Authors’ Contributions

AP, LvdE, JdH, AvT and RK performed the analyses, interpreted the data and wrote the paper. JB revised the pathological slides and selected areas of LS, dVIN and VSCC. EJK, JY and AE performed the experiments. KH and JH provided expert input on analysis and interpretation of data. JB and LM provided additional expert comments and edits. All authors contributed to revision of the manuscript and the final published paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by “Stichting Ruby and Rose” and “Radboud Oncology Funding”.

References

- 1.Schuurman MS, van den Einden LC, Massuger LF, Kiemeney LA, van der Aa MA, de Hullu JA. Trends in incidence and survival of dutch women with vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(18):3872–3880. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.08.003. PMID: 24011936. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Avoort IA, Shirango H, Hoevenaars BM, Grefte JM, de Hullu JA, de Wilde PC, Bulten J, Melchers WJ, Massuger LF. Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma is a multifactorial disease following two separate and independent pathways. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2006;25(1):22–29. doi: 10.1097/01.pgp.0000177646.38266.6a. PMID: 16306780. DOI: 10.1097/01.pgp.0000177646.38266.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoevenaars BM, van der Avoort IA, de Wilde PC, Massuger LF, Melchers WJ, de Hullu JA, Bulten J. A panel of p16(ink4a), mib1 and p53 proteins can distinguish between the 2 pathways leading to vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2008;123(12):2767–2773. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23857. PMID: 18798277. DOI: 10.1002/ijc.23857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van de Nieuwenhof HP, van Kempen LC, de Hullu JA, Bekkers RL, Bulten J, Melchers WJ, Massuger LF. The etiologic role of hpv in vulvar squamous cell carcinoma fine tuned. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(7):2061–2067. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0209. PMID: 19567503. DOI: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-09-0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Sanjose S, Alemany L, Ordi J, Tous S, Alejo M, Bigby SM, Joura EA, Maldonado P, Laco J, Bravo IG, Vidal A, Guimera N, Cross P, Wain GV, Petry KU, Mariani L, Bergeron C, Mandys V, Sica AR, Felix A, Usubutun A, Seoud M, Hernandez-Suarez G, Nowakowski AM, Wilson G, Dalstein V, Hampl M, Kasamatsu ES, Lombardi LE, Tinoco L, Alvarado-Cabrero I, Perrotta M, Bhatla N, Agorastos T, Lynch CF, Goodman MT, Shin HR, Viarheichyk H, Jach R, Cruz MO, Velasco J, Molina C, Bornstein J, Ferrera A, Domingo EJ, Chou CY, Banjo AF, Castellsague X, Pawlita M, Lloveras B, Quint WG, Munoz N, Bosch FX, group HVs. Worldwide human papillomavirus genotype attribution in over 2000 cases of intraepithelial and invasive lesions of the vulva. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(16):3450–3461. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.06.033. PMID: 23886586. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlson JA, Ambros R, Malfetano J, Ross J, Grabowski R, Lamb P, Figge H, Mihm MC Jr. Vulvar lichen sclerosus and squamous cell carcinoma: A cohort, case control, and investigational study with historical perspective; implications for chronic inflammation and sclerosis in the development of neoplasia. Hum Pathol. 1998;29(9):932–948. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90198-8. PMID: 9744309. DOI: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kokka F, Singh N, Faruqi A, Gibbon K, Rosenthal AN. Is differentiated vulval intraepithelial neoplasia the precursor lesion of human papillomavirus-negative vulval squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21(7):1297–1305. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31822dbe26. PMID: 21946295. DOI: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31822dbe26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van de Nieuwenhof HP, Massuger LF, van der Avoort IA, Bekkers RL, Casparie M, Abma W, van Kempen LC, de Hullu JA. Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma development after diagnosis of vin increases with age. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(5):851–856. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.037. PMID: 19117749. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van den Einden LC, de Hullu JA, Massuger LF, Grefte JM, Bult P, Wiersma A, van Engen-van Grunsven AC, Sturm B, Bosch SL, Hollema H, Bulten J. Interobserver variability and the effect of education in the histopathological diagnosis of differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Mod Pathol. 2013;26(6):874–880. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.235. PMID: 23370772. DOI: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van de Nieuwenhof HP, Bulten J, Hollema H, Dommerholt RG, Massuger LF, van der Zee AG, de Hullu JA, van Kempen LC. Differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia is often found in lesions, previously diagnosed as lichen sclerosus, which have progressed to vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2011;24(2):297–305. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.192. PMID: 21057461. DOI: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liegl B, Regauer S. P53 immunostaining in lichen sclerosus is related to ischaemic stress and is not a marker of differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (d-vin) Histopathology. 2006;48(3):268–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02321.x. PMID: 16430473. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nooij LS, Ter Haar NT, Ruano D, Rakislova N, van Wezel T, Smit V, Trimbos B, Ordi J, van Poelgeest MIE, Bosse T. Genomic characterization of vulvar (pre)cancers identifies distinct molecular subtypes with prognostic significance. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(22):6781–6789. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1302. PMID: 28899974. DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-17-1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rolfe KJ, MacLean AB, Crow JC, Benjamin E, Reid WM, Perrett CW. Tp53 mutations in vulval lichen sclerosus adjacent to squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Br J Cancer. 2003;89(12):2249–2253. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601444. PMID: 14676802. DOI: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choschzick M, Hantaredja W, Tennstedt P, Gieseking F, Wolber L, Simon R. Role of tp53 mutations in vulvar carcinomas. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2011;30(5):497–504. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e3182184c7a. PMID: 21804386. DOI: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e3182184c7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zieba S, Kowalik A, Zalewski K, Rusetska N, Goryca K, Piascik A, Misiek M, Bakula-Zalewska E, Kopczynski J, Kowalski K, Radziszewski J, Bidzinski M, Gozdz S, Kowalewska M. Somatic mutation profiling of vulvar cancer: Exploring therapeutic targets. Gynecol Oncol. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.06.026. PMID: 29980281.DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61(5):759–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. PMID: 2188735. DOI: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, Moorhead M, Karlin-Neumann G, Wang NJ, Ireland J, Lin S, Chen C, Heiser LM, Chin K, Esserman L, Gray JW, Spellman PT, Faham M. Analysis of molecular inversion probe performance for allele copy number determination. Genome Biol. 2007;8(11):R246. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-11-r246. PMID: 18028543. DOI: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-11-r246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schiffman JD, Wang Y, McPherson LA, Welch K, Zhang N, Davis R, Lacayo NJ, Dahl GV, Faham M, Ford JM, Ji HP. Molecular inversion probes reveal patterns of 9p21 deletion and copy number aberrations in childhood leukemia. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2009;193(1):9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2009.03.005. PMID: 19602459. DOI: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Moorhead M, Karlin-Neumann G, Falkowski M, Chen C, Siddiqui F, Davis RW, Willis TD, Faham M. Allele quantification using molecular inversion probes (mip) Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(21):e183. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni177. PMID: 16314297. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gni177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durinck S, Bullard J, Spellman PT, Dudoit S. Genomegraphs: Integrated genomic data visualization with r. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10 (2) doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-2. PMID: 19123956. DOI:10.1186/1471-2105-10-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hiatt JB, Pritchard CC, Salipante SJ, O’Roak BJ, Shendure J. Single molecule molecular inversion probes for targeted, high-accuracy detection of low-frequency variation. Genome Res. 2013;23(5):843–854. doi: 10.1101/gr.147686.112. PMID: 23382536. DOI: 10.1101/gr.147686.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weren RD, Ligtenberg MJ, Kets CM, de Voer RM, Verwiel ET, Spruijt L, van Zelst-Stams WA, Jongmans MC, Gilissen C, Hehir-Kwa JY, Hoischen A, Shendure J, Boyle EA, Kamping EJ, Nagtegaal ID, Tops BB, Nagengast FM, Geurts van Kessel A, van Krieken JH, Kuiper RP, Hoogerbrugge N. A germline homozygous mutation in the base-excision repair gene nthl1 causes adenomatous polyposis and colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2015;47(6):668–671. doi: 10.1038/ng.3287. PMID: 25938944. DOI: 10.1038/ng.3287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eijkelenboom A, Kamping EJ, Kastner-van Raaij AW, Hendriks-Cornelissen SJ, Neveling K, Kuiper RP, Hoischen A, Nelen MR, Ligtenberg MJ, Tops BB. Reliable next-generation sequencing of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue using single molecule tags. J Mol Diagn. 2016;18(6):851–863. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2016.06.010. PMID: 27637301. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu J, Antic Z, van Reijmersdal SV, Hoischen A, Sonneveld E, Waanders E, Kuiper RP. Accurate detection of low-level mosaic mutations in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia using single molecule tagging and deep-sequencing. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018;59(7):1690–1699. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2017.1390232. PMID: 29058513. DOI: 10.1080/10428194.2017.1390232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li SY, Hu JA, Wang HM. Expression of yes-associated protein 1 gene and protein in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Chin Med J (Engl) 2013;126(4):655–658. PMID: 23422184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu JY, Li YH, Lin HX, Liao YJ, Mai SJ, Liu ZW, Zhang ZL, Jiang LJ, Zhang JX, Kung HF, Zeng YX, Zhou FJ, Xie D. Overexpression of yap 1 contributes to progressive features and poor prognosis of human urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:349. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-349. PMID: 23870412. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y, Xie C, Li Q, Xu K, Wang E. Clinical and prognostic significance of yes-associated protein in colorectal cancer. Tumour Biol. 2013;34(4):2169–2174. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0751-x. PMID: 23558963. DOI: 10.1007/s13277-013-0751-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eva LJ, Ganesan R, Chan KK, Honest H, Luesley DM. Differentiated-type vulval intraepithelial neoplasia has a high-risk association with vulval squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19(4):741–744. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a12fa2. PMID: 19509581. DOI: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a12fa2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinto AP, Miron A, Yassin Y, Monte N, Woo TY, Mehra KK, Medeiros F, Crum CP. Differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia contains tp53 mutations and is genetically linked to vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2010;23(3):404–412. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.179. PMID: 20062014. DOI: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin MC, Mutter GL, Trivijisilp P, Boynton KA, Sun D, Crum CP. Patterns of allelic loss (loh) in vulvar squamous carcinomas and adjacent noninvasive epithelia. Am J Pathol. 1998;152(5):1313–1318. PMID: 9588899. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pinto AP, Lin MC, Sheets EE, Muto MG, Sun D, Crum CP. Allelic imbalance in lichen sclerosus, hyperplasia, and intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;77(1):171–176. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5739. PMID: 10739707. DOI: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinto AP, Lin MC, Mutter GL, Sun D, Villa LL, Crum CP. Allelic loss in human papillomavirus-positive and -negative vulvar squamous cell carcinomas. Am J Pathol. 1999;154(4):1009–1015. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65353-9. PMID: 10233839. DOI: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65353-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]