To the Editor,

Histamine and cysteinyl leukotrienes (CysLTs) are potent inflammatory mediators involved in both seasonal allergic rhinoconjunctivitis (SARC) and asthma.1, 2 A combination therapy against both these agents may provide additive benefit, as demonstrated both in vitro 3 and in vivo.4, 5, 6

We compared the efficacy and safety of concomitant therapy with bilastine, a second‐generation H1 anti‐histamine7 and montelukast vs each agent alone in patient with SARC and asthma. We hypothesized that bilastine plus montelukast is superior to bilastine monotherapy in reducing SARC symptoms after 4 weeks and in improving asthma quality of life over a longer time period.

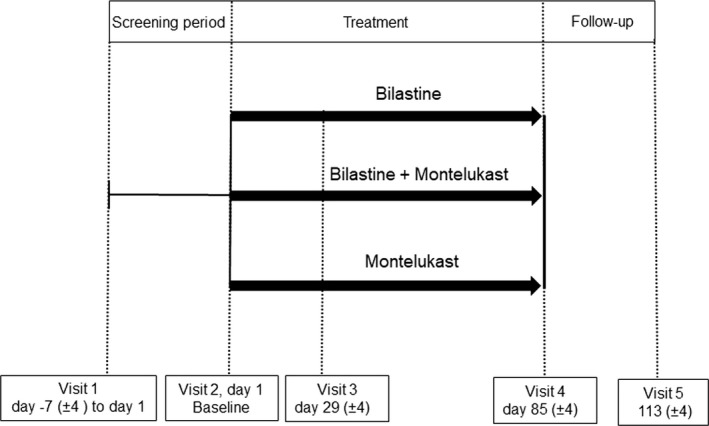

Adult patients with SARC and mild‐to‐moderate asthma partially controlled8 by beclomethasone dipropionate or equivalent ≤500 μg/d (alone or in combination with long‐term β2‐adrenergic bronchodilators) were enrolled. Patients had a postbronchodilator FEV1 > 70% of the predicted, a skin prick test positive to at least one seasonal allergen tested at enrolment or previously reported, and a nasal/ocular Total Symptom Score (TSS) ≥3.9 Exclusion criteria are reported in the online supplementary. The study (EUDRA‐CT number:2015‐004806‐40) was conducted in 50 centres across 6 European countries during the relevant regional pollen season for grasses, trees and weeds, with a double‐blind, double‐dummy, randomized, active‐controlled and parallel‐group design (Figure 1). It consisted in a 1‐week screening period followed by 12 weeks of treatment. During the study, patients quantified SARC symptoms by TSS, Daytime Nasal Symptom Score (DNSS) and Daytime non‐Nasal Symptom Score (DNNS); use of rescue medications and occurrence of adverse events were noted. During screening, patients’ medical history, vital signs, spirometry results and asthma quality of life questionnaire (AQLQ) scores were obtained. AQLQ was re‐assessed after 4 and 12 weeks of treatment; ECG variables, blood and urine samples were re‐obtained at the end of treatments for safety purposes. Enrolled patients were randomly treated once daily with bilastine 20 mg plus montelukast 10 mg, or bilastine 20 mg plus placebo or montelukast 10 mg plus placebo (Figure 1). Naphazoline nasal spray eye drops and salbutamol inhaler were rescue medications for SARC and acute asthma symptoms. Patients’ compliance with treatments was calculated. The primary endpoint was changes in baseline TSS values following 4 weeks of treatment.10 Secondary endpoints were changes in baseline TSS values obtained after 1, 2 and 3 weeks of treatment; changes in baseline DNSS and DNNSS values obtained after 1, 2, 3 and 4 weeks of treatments; changes in baseline AQLQ score obtained after 4 and 12 weeks of treatment. Analyses were performed on the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) population, ie randomized patients who had received at least one treatment tablet, had a baseline assessment and at least one assessment of primary efficacy variable after the baseline visit. A sensitivity analysis was also performed on the per‐protocol (PP) population, ie patients in the ITT population having completed the study without any major protocol violation. The effect of each treatment on primary and secondary endpoints, as well as on use of rescue medications for SARC and asthma was compared by analysis of covariance. A P value <.05 was considered as significant. Additional details on the methods are in the online supplementary.

Figure 1.

Study design and treatment

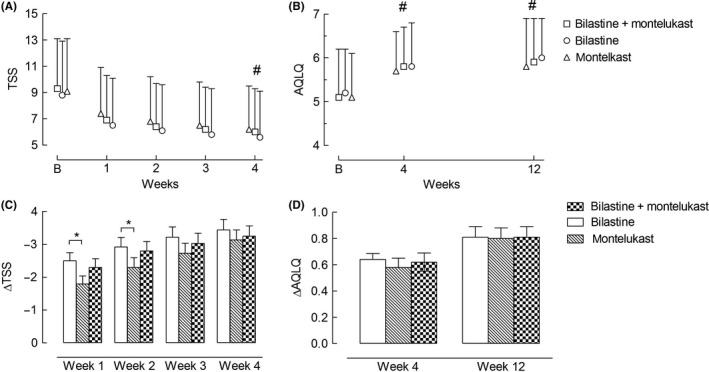

From April to October 2016, we enrolled 454 patients, 419 of whom (299 females, mean age 35.2 ± 0.2) were randomized to treatment (ITT population). Of these 419 patients, 387 completed the study without protocol violations (PP population, Figure S1). Reasons of patients exclusion are reported in the Figure S1 (data supplement). Most patients had polisensitization to pollens of grasses, trees and weeds. At inclusion, patients’ demographics, FEV1, TSS, AQLQ, DNSS and DNNSS were similar in each treatment arm (Table S1). All treatments significantly (P < .001) reduced baseline TSS values over 4 weeks (Figure 2). Overall, the mean ± SD TSS reduction was −3.2 ± 3.7, with no significant differences among treatments. Mean TSS value observed 1 and 2 weeks after bilastine was significantly (P < .05) lower than after montelukast. (Figure 2). Mean TSS values decreased similarly with all treatments after 3 weeks (Figure 2). However, bilastine reduced baseline TSS more than montelukast after 1 and 2 weeks of treatment (P always <.05). Similar findings were observed for DNSS and DNNSS (data not shown). Mean AQLQ increased similarly with all treatments after 4 and 12 weeks. The use of rescue medications for SARC and/or asthma did not differ among treatments, as was patients’ compliance with treatments (98.3% overall). Drug‐related incidence of adverse events was similar among the treatment groups (4.3% overall). No clinically significant changes in any laboratory tests, ECGs or vital signs were noted.

Figure 2.

Mean (SD) total symptom score (TSS, panel A) and asthma quality of life questionnaire (AQLQ, panel B) values in patients treated with bilastine plus montelukast and in those treated with bilastine or montelukast alone. Estimated (SEM) changes in TSS and AQLQ from the corresponding baseline values observed after each week of treatment with bilastine, montelukast or bilastine plus montelukast are depicted in panel (C) and (D), respectively. B, baseline; *, P < .05 comparing TSS values in bilastine vs montelukast after 1 wk of treatment; #, P < .001 comparing TSS values observed 4 wk after treatment with bilastine plus montelukast, bilastine or montelukast alone vs corresponding baseline values

We compared for the first time the efficacy and safety of concomitant administration of bilastine with montelukast vs respective monotherapies in a large population of patients with SARC and asthma. Contrary to our original hypothesis, concomitant administration of bilastine with montelukast was effective as either agent alone in the treatment of SARC symptoms. The reason(s) for not showing any additive effects of bilastine plus montelukast compared with each agent alone could be likely related to the overall mild intensity of SARC symptoms at baseline that might have reduced the room for improvement thus limiting the probability to detect differences between treatments. The absolute extent of the effect of treatments on symptoms or on the use of rescue medications is impossible to gauge as a placebo arm was not included. Noteworthy, the improvement in TSS values observed in our study is similar to that obtained after 2 weeks of placebo treatment by Bachert et al.9 Although the underlying cause is unclear, the large placebo effect observed by Bachert et al9 is not uncommon as observed in other studies with SARC patients.11

Bilastine alone improved SARC symptoms more than montelukast in the first 2 weeks of treatment. This finding is consisted with a more rapid effect of bilastine than montelukast, which may be of relevance for patients who need intermittent treatment to alleviate SARC symptoms. The absolute extent of the effect of these treatments on symptomatology or the use of rescue medication when treating SARC and concomitant asthma are impossible to gauge from this study because a group of patients treated entirely with placebo was not included. Moreover, since changes in lung function were not monitored, it is difficult to gauge how far this improvement reflected possible effects of study treatments on bronchoconstriction and/or lower airways inflammation or how far they reflected a true placebo effect. Previous reports suggest that an improvement in SARC can also improve asthma control.12 Thus, due to its beneficial effects on SARC symptoms, our results suggest that bilastine, when added to inhaled corticosteroids alone or in combination with long‐term β2‐adrenergic bronchodilators, could improve disease control in mild‐to‐moderate asthma patients.

In conclusion, treatment with bilastine plus montelukast over 4 weeks does not consistently produce further improvements in SARC symptoms and AQLQ beyond those provided by either agent alone. Thus, there is no benefit of using bilastine plus montelukast to provide relief of SARC symptoms in partially controlled, mild‐to‐moderate asthma patients.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The SKY study was sponsored by Menarini International Operations Luxemburg SA (MIOL).

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Prof. Chris Corrigan for his helpful advice.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wenzel SE, Larsen GL, Johnston K, et al. Elevated levels of leukotriene C4 in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from atopic asthmatics after endobronchial allergen challenge. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:112‐119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pavord I, Ward R, Woltmann G, Wardlaw A, Sheller J, Dworski R. Induced sputum eicosanoid concentrations in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:1905‐1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bjorck T, Dahlen S‐E. Leukotrienes and histamine mediate IgE‐dependent contractions of human bronchi: pharmacological evidence obtained with tissues from asthmatic and non‐asthmatic subjects. Pulm Pharmacol. 1993;6:87‐96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Davis BE, Illamperuma C, Gauvreau GM, et al. Single‐dose desloratadine and montelukast and allergen‐induced late airway responses. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:1302‐1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Davis BE, Todd DC, Cockcroft DW. Effect of combined montelukast and desloratadine on the early asthmatic response to inhaled allergen. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(4):768‐772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reicin A, White R, Weinstein SF, et al. Montelukast, a leukotriene receptor antagonist, in combination with loratadine, a histamine receptor antagonist, in the treatment of chronic asthma. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(16):2481‐2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ridolo E, Montagni M, Bonzano L, Incorvaia C, Canonica GW. Bilastine: new insight into antihistamine treatment. Clin Mol Allergy. 2015; 13(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Global Initiative for Asthma . Global strategy for asthma management and prevention Vancouver (WA): Global Initiative for Asthma; 2012. http://www.ginasthma.org

- 9. Bachert C, Kuna P, Sanquer F, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of bilastine 20 mg vs desloratadine 5 mg in seasonal allergic rhinitis patients. Allergy. 2009, 64, 158‐165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2000/06/21/00-15632/draft-guidance-for-industry-on-allergic-rhinitis-clinical-development-programs-for-drug-products.

- 11. Van Cauwenberge P, Juniper EF. Comparison of the efficacy, safety and quality of life provided by fexofenadine hydrochloride 120 mg, loratadine 10 mg and placebo administered once daily for the treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30:891‐899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Corren J. Allergic rhinitis and asthma: how important is the link? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99(2):S781‐S786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials