Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to evaluate what types and forms of support nursing staff need in providing palliative care for persons with dementia. Another aim was to compare the needs of nursing staff with different educational levels and working in home care or in nursing homes.

Design

A cross‐sectional, descriptive survey design was used.

Methods

A questionnaire was administered to a convenience sample of Dutch nursing staff working in the home care or nursing home setting. Data were collected from July through October 2018. Quantitative survey data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Data from two open‐ended survey questions were investigated using content analysis.

Findings

The sample comprised 416 respondents. Nursing staff with different educational levels and working in different settings indicated largely similar needs. The highest‐ranking needs for support were in dealing with family disagreement in end‐of‐life decision making (58%), dealing with challenging behaviors (41%), and recognizing and managing pain (38%). The highest‐ranking form of support was peer‐to‐peer learning (51%). If respondents would have more time to do their work, devoting personal attention would be a priority.

Conclusions

Nursing staff with different educational levels and working in home care or in nursing homes endorsed similar needs in providing palliative care for persons with dementia and their loved ones.

Clinical Relevance

It is critical to understand the specific needs of nursing staff in order to develop tailored strategies. Interventions aimed at increasing the competence of nursing staff in providing palliative care for persons with dementia may target similar areas to support a heterogeneous group of nurses and nurse assistants, working in home care or in a nursing home.

Keywords: Dementia, home care, nursing home, nursing practice, older people, palliative care

Home care and nursing home staff have an important role in providing palliative care for persons with dementia and their loved ones (Smythe, Jenkins, Galant‐Miecznikowska, Bentham, & Oyebode, 2017). Palliative care is aimed at optimizing the quality of life of persons facing a life‐threatening illness and their families (World Health Organization, n.d.). Dementia is an incurable, neurodegenerative disease and a palliative approach to care is recommended for persons with dementia (van der Steen et al., 2014). In the Netherlands, direct nursing staff includes registered nurses, certified nurse assistants (i.e., licenced nurses), and nurse assistants (Backhaus, 2017). Nursing staff have a prominent role in daily caregiving, and they are generally more accessible than physicians (Albers, Francke, de Veer, Bilsen, & Onwuteaka‐Philipsen, 2014; Toles, Song, Lin, & Hanson, 2018). Thereby, they are conveniently positioned to discuss care wishes, to identify burdensome symptoms, and to increase quality of life (van der Steen et al., 2014). However, nursing staff may not feel competent to provide adequate palliative care for persons with dementia; they report difficulties in recognizing and addressing physical, psychosocial, and spiritual care needs, dealing with challenging behaviors, and communicating with persons with dementia (Bolt, van der Steen, Schols, Zwakhalen, Pieters, & Meijers, 2019).

Palliative care for persons with dementia is often complex, and heterogeneous care needs may arise (Perrar, Schmidt, Eisenmann, Cremer, & Voltz, 2015), especially in the advanced stages (Hendriks, Smalbrugge, Galindo‐Garre, Hertogh, & van der Steen, 2015; Mitchell et al., 2009). Lacking skills and knowledge among nursing staff may adversely affect the quality of palliative care (Erel, Marcus, & Dekeyser‐Ganz, 2017; Mitchell et al., 2009; Robinson et al., 2014). In the Netherlands, only persons needing 24‐hr care qualify for nursing home care, which implies that persons with dementia in nursing homes are highly reliant on nursing staff (Maarse & Jeurissen, 2016). The majority of persons with dementia live in the community, and they require appropriate services to support living at home (Saks et al., 2015). Nursing staff working in home care or in nursing homes should be competent to safeguard the quality of (palliative) care. Today, there is limited knowledge about the specific competency needs that may help to close the knowledge and skills gap in the dementia workforce (Surr et al., 2017).

Interventions aimed at increasing the competence of nursing staff should be tailored to their needs and preferences (Smythe et al., 2017; Whittaker, George Kernohan, Hasson, Howard, & McLaughlin, 2006). The needs of nursing staff in providing palliative care for persons with dementia, particularly in the home care setting, have not been assessed in depth (D'Astous, Abrams, Vandrevala, Samsi, & Manthorpe, 2019). Moreover, research investigating and comparing the needs of nursing staff with different educational backgrounds and from different settings in providing palliative care for persons with dementia is scarce. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the needs of nursing staff in providing palliative care for persons with dementia. The study aimed to compare nursing staff with different educational levels and nursing staff working in home care or in nursing homes. Moreover, the study aimed to investigate what forms of support (e.g., digital, educational, emotional) nursing staff prefer.

Methods

This cross‐sectional, descriptive study is part of the Desired Dementia Care Towards End of Life (DEDICATED) project carried out in The Living Lab in Ageing & Long‐Term Care in South Limburg (Verbeek, Zwakhalen, Schols, & Hamers, 2013). DEDICATED aims to develop a tailored intervention to empower nursing staff in providing palliative care for persons with dementia. A web‐based questionnaire was administered to explore the needs of nursing staff in several aspects of palliative care in dementia. Data were collected in the Netherlands from July through October 2018, using Qualtrics (Provo, Utah, USA) online survey software. The Medical Ethics Committee approved the study (Zuyderland, METCZ20180079).

Sample, Recruitment, and Procedure

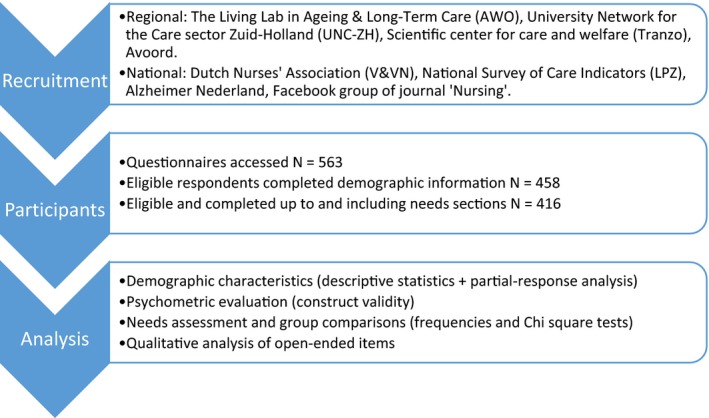

A convenience sample was recruited, and respondents from different sociodemographic areas and organizations were approached to increase representativeness. Eligible participants were: (a) nursing staff members; (b) who had been employed for at least 6 months; (c) currently working in home care or in a nursing home; (d) providing care for older persons (≥65 years of age) with dementia. The investigators shared a hyperlink granting access to the Qualtrics questionnaire with the main contact persons within the collaborating organizations. The contact persons then distributed the invitation with an information letter and a hyperlink to the consent form. Figure 1 provides an overview of the regional and national organizations that distributed the questionnaire. Participation was voluntary. Participants provided written informed consent for anonymous processing of data before they could access the questionnaire by checking a box stating “agreed” and submitting the answer. At the beginning of the questionnaire, participants confirmed they met the inclusion criteria and they were asked to indicate via which route the questionnaire had reached them.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study process. [Colour figure can be viewed at http://www.wileyonlinelibrary.com/]

Questionnaire Design

Because no instrument that matched this study’s specific aims existed, a questionnaire was designed to explore the needs of nursing staff in providing palliative care for persons with dementia. The questionnaire included items covering the main focus areas of the DEDICATED project: palliative caregiving and end‐of‐life communication, and interprofessional collaboration and transitions of care. The full questionnaire is provided as supplementary material (Table S1). This article focuses on the sections regarding palliative caregiving and end‐of‐life communication.

Initial item development was informed by results of earlier work to investigate needs in palliative caregiving for persons with dementia (Bolt, van der Steen, Schols, Zwakhalen, Pieters, & Meijers, 2019; Bolt, van der Steen, Schols, Zwakhalen, & Meijers, 2019; Bolt, Verbeek, Meijers, & van der Steen, 2019). Moreover, the main literature sources used throughout the DEDICATED project involve a white paper established by the European Association for Palliative Care, with recommendations for palliative care for persons with dementia (van der Steen et al., 2014) and a systematic review of the palliative care needs of persons with dementia (Perrar et al., 2015). Lastly, the End‐of‐life Professional Caregiver Survey (Lazenby, Ercolano, Schulman‐Green, & McCorkle, 2012) informed item development. Three investigators (J.M., S.P., and S.B.) developed items and discussed them with all members of the research team to reach consensus. To establish further face and content validity, the investigators invited a group of key informants (i.e., healthcare professionals, nurse education specialists, and patient representatives) to carefully review the questionnaire and to provide recommendations for improvement. From three local collaborating care organizations, separate test panels of nursing staff (two registered nurses, two certified nurse assistants, and two uncertified nurse assistants per organization) piloted the questionnaire for feasibility and provided feedback for final improvement. Improvements were mainly in language usage.

The questionnaire asked about the demographic and work‐related characteristics: age, sex, location of work (province), current work setting, current job title, years of experience in dementia care, additional training in dementia or palliative care, and self‐perceived competence (on a scale from 0 to 10) in providing palliative care for persons with dementia. Thereafter, needs in palliative caregiving and in end‐of‐life communication were examined, presenting item lists of potential needs (Table S1). The last section showed items on preferred forms of support (Table S1). Respondents could select multiple items. The questionnaire finished with two optional open‐ended items: “Are there any other aspects of palliative care for persons with dementia in which you need support?” and “If you had more time to do your work, what would you use it for?”

Analysis

Quantitative analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Responses were included if completed at least up to and including the section asking about needs for support in palliative caregiving and end‐of‐life communication. A partial‐response analysis was performed, comparing available characteristics of eligible participants that did and did not complete the questionnaire to this point. Chi‐square tests and independent t‐tests were used. Descriptive statistics were used to present demographic and work‐related characteristics, which were compared using chi‐square tests. Respondents’ self‐perceived competence in providing palliative dementia care was compared between the different educational levels and the different settings using analysis of variance and an independent t test, respectively; p values of less than .05 were considered to be statistically significant. Pearson’s correlations between the respondents’ self‐perceived competence and summed needs in palliative caregiving (16 items) and end‐of‐life communication (8 items) were calculated to explore the questionnaire’s construct validity. Cronbach’s alpha for internal consistency was not calculated, as the items were designed to explore a variety of needs rather than a single construct.

For each item concerning support needs and preferred forms of support, frequencies of the item being endorsed were counted. Chi‐square tests were used to explore differences in item endorsement by educational level and work setting. Holm’s sequential Bonferroni procedure was applied to adjust for multiple testing (Abdi, 2010). Therein, the smallest p value of a series of tests is significant at p < .05 per number of test items. The second smallest p value is significant at p < .05 per number of test items ‐ 1, the third at p < .05 per number of test items ‐ 2, and so forth. Assumptions underlying the statistical analyses were tested using Levene’s test and Q‐Q plots.

Content analysis was used to explore answers to both open‐ended questions (Bengtsson, 2016) using NVivo 11 software (QSR International Pty Ltd, headquarters in Doncaster, Victoria, Australia). Initial coding and clustering codes into categories was performed by one researcher (S.B.). Recurring categories were discussed with the research team to allow cross‐validation. After fine tuning with the team, a final list of main categories was used to analyze the data a second time to ensure these covered all answers. Frequencies of answers reflecting the established main categories were counted.

Results

The sample included in the analyses comprised 416 respondents, of whom 192 (46%) worked in a home setting and 224 (54%) in a nursing home setting (Table 1). Their mean age was 45.5 (SD 12.1, range 18.0–65.0) years, and they had a mean of 15.6 (SD 10.9, range 0.8–43.0) years of experience in dementia care. Respondents rated their own competence in providing palliative care for persons with dementia with an average score of 7.5 (SD 1.3, range 0–10), indicating an overall good score (Nuffic, 2019). Nursing home staff scored higher (mean 7.9, SD 1.2) than home care staff did (mean 7.2, SD 1.4); t (414) = ‐4.8, p < .001. No differences were found between educational levels (registered nurses, certified nurse assistants, and uncertified nurse assistants).

Table 1.

Summary of Respondents’ Characteristics

| Respondent characteristics (N = 416) | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 401 | 96 |

| Male | 15 | 4 |

| Nursing degree/educational level | ||

| Registered nursea | 164 | 40 |

| Certified nurse assistant | 218 | 52 |

| Uncertified nurse assistant | 34 | 8 |

| Primary work settingb | ||

| Nursing home | 224 | 54 |

| Home care | 192 | 46 |

| Additional trainingc in dementia cared | ||

| Yes | 201 | 48 |

| No | 215 | 52 |

| Additional trainingc in palliative caree | ||

| Yes | 186 | 44 |

| No | 230 | 56 |

| Providing palliative care is…f | ||

| …a standard task for all nursing and care staff with a basic education | 308 | 74 |

| …a task for nursing and care staff specialized in palliative care | 108 | 26 |

Registered nurses included vocationally trained and baccalaureate‐educated nurses, and nurse practitioners.

Significant differences between educational levels (chi‐square = 32.35, p < .001)

Additional training was defined as an educational effort of at least 2 hr outside of one’s basic nursing curriculum.

Significant differences between work settings (more often in nursing homes; chi‐square = 17.60, p < .001) but not educational levels.

Significant differences between educational levels(chi‐square = 7.39, p < .05) but not work setting.

No differences found between educational levels or work setting.

Considering construct validity, there was a negative correlation between respondents’ self‐perceived competence and summed needs in caregiving (r = ‐.30, p < .001) and end‐of‐life communication (r = ‐.14, p = .003). Thus, respondents who feel less competent report more support needs. Respondents’ needs were rank ordered by frequencies (Table 2). Most needs did not differ between educational levels and settings (Table S2).

Table 2.

Frequencies for Each Item Regarding Needs in Palliative Caregiving and End‐of‐Life Communication, in Descending Order (N = 416)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Needs in palliative caregiving | |

| Recognizing and dealing with certain behavior, such as agitation or aggression | 169 (41) |

| Recognizing discomfort and dealing with pain | 156 (38) |

| Guiding persons with dementia and their loved ones in the dying phase | 143 (34) |

| Recognizing and dealing with emotions, such as sadness, anxiety, or anger | 141 (34) |

| Communicating with persons with severe dementia | 139 (33)a |

| Recognizing (the start of) the dying phase | 129 (31) |

| Using (validated) instruments, e.g., for measuring symptoms | 113 (27) |

| Opportunities to get to know the person with dementia and their loves ones well | 109 (26) |

| My personal contribution to meaningful activities for persons with dementia | 107 (26) |

| Involving loved ones in the entire care process | 103 (25) |

| Recognizing and optimizing physical comfort | 89 (21) |

| Dealing with religious and existential questions | 84 (20) |

| Supporting loved ones after bereavement | 75 (18) |

| Feeling more comfortable interacting with loved ones | 41 (10) |

| Feeling more comfortable when caring for persons with dementia | 36 (9)a |

| Providing daily care/assisting self‐care (ADL and IADL) | 29 (7)b |

| Needs in end‐of‐life communication | |

| Dealing with disagreement between loved ones about end‐of‐life care | 240 (58) |

| Involving people with dementia in end‐of‐life decision making | 171 (41)b |

| Guiding people with dementia and their loved ones to document end‐of‐life wishes | 165 (40) |

| Having a conversation about the end of life | 136 (33) |

| Involving loved ones in end‐of‐life decision making | 130 (31) |

| Being able to retrieve documented end‐of‐life wishes | 118 (28) |

| Deciding on the right time to initiate end‐of‐life communication | 116 (28) |

| Feeling comfortable talking about the end of life with people with dementia and their loved ones | 101 (24) |

Needs for Support in Palliative Caregiving and End‐of‐Life Communication

The highest‐ranking needs for support in caregiving were recognizing and dealing with challenging behaviors (41%), pain (38%), and emotions (34%); providing guidance in the dying phase (34%); and communicating with persons with severe dementia (33%). The highest‐ranking needs for support in end‐of‐life communication were dealing with family disagreement (58%) and involving persons with dementia in end‐of‐life decision making (41%). There were significant differences between settings in support needs in “communicating with persons with severe dementia,” which was endorsed by 42% of the home care respondents and 23% of nursing home respondents (chi‐square = 15.95, p < .001). Needs in “feeling comfortable when caring for persons with dementia” was endorsed by 13% of the home care respondents and 3% of nursing home respondents (chi‐square = 13.78, p < .001). Nursing staff with different educational levels differed in support needs in “providing daily care/assisting self‐care (ADL and IADL),” which was endorsed by 2% of the registered nurses, 9% of the certified nurse assistants, and 21% of the uncertified nurse assistants (chi‐square = 17.43, p < .001). Moreover, “involving persons with dementia in end‐of‐life decision making” was endorsed by 48% of the registered nurses, 40% of the certified nurse assistants, and 15% of the uncertified nurse assistants (chi‐square = 13.30, p = .001).

Preferred Forms of Support

Nursing staff chiefly preferred support in the form of peer‐to‐peer learning (51%, Table 3). Also frequently endorsed were joint case discussions (48%) and classical education (45%). The fourth‐ranking form involved organizational support (43%). Frequencies were mostly similar across settings and educational levels (Table S3). Jointly discussing cases differed between registered nurses (54%), certified nurse assistants (49%), and uncertified nurse assistants (13%, chi‐square = 17.62, p < .001).

Table 3.

Frequencies of Reported Forms of Support in Descending Order (N = 366a)

| Preferred forms of support | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Exchanging experiences with colleagues (peer‐to‐peer learning) | 185 (51) |

| Jointly discussing cases | 176 (48)b |

| Classical education (e.g., clinical lessons) | 164 (45) |

| General organizational support (e.g., sufficient time, resources, staffing) | 158 (43) |

| A palliative care expert or team to ask for advise | 131 (36) |

| E‐learning | 112 (30) |

| Coaching/supervision on the work floor (coaching on the job) | 106 (29) |

| Electronic client or patient files with access by all involved caregivers | 71 (19) |

| Care processes depicted in care paths (e.g., care path dying phase) | 63 (17) |

| A guide to or overview of available care providers | 63 (17)c |

| Digital communication medium with access by all involved caregivers | 54 (15) |

| Digital support on the work floor (e.g., measuring instruments, checklists) | 46 (13) |

| Collaboration agreements within own organization | 46 (13) |

| Emotional support from direct colleagues | 43 (12) |

| More opportune moments to consult a palliative care expert or team | 41 (11) |

| Collaboration agreements with professionals outside own organization | 35 (10)b |

| Mobile apps | 35 (10) |

| Digital informative movies, animations, or podcasts | 34 (9) |

| Training by means of actors or puppets | 30 (8) |

| Emotional support from the organization (e.g., trustees) | 25 (7) |

| Serious gaming (games with an educative goal) | 16 (4) |

| (Being referred to) professional emotional support | 7 (2) |

The preferred forms of support section was at the end of the questionnaire. The smaller sample size is due to respondents that prematurely withdrew from completing the questionnaire, after finishing at least the caregiving and end‐of‐life communication items.

Significant differences between educational levels. Details are shown in Table S3.

Significant differences between educational levels and settings. Details are shown in Table S3.

Open‐Ended Questions

Additional issues that were raised beyond the survey items included wishes for specific knowledge and skills in palliative dementia care (e.g., caring for specific groups, such as people with aphasia or with another ethnical background, applying complementary therapies), general awareness about palliative care, family involvement and support, and dealing with ethical matters. If respondents had more time to do their work, the main priority would be to devote more personal attention by making a connection, being present and “in the moment,” investing in a close care relationship, and learning about the individual person (Table 4). Moreover, extra time would be invested in supporting families, safeguarding quality of care, deepening one’s knowledge, and exchanging and reflecting on experiences with colleagues.

Table 4.

Descriptions and Frequencies of Main Categories in Answers to the Open‐Ended Question: “If you had more time to do your work, what would you use it for?” (n = 238)

| Main categories | Description (subcategories) | Example citation | Frequencya |

|---|---|---|---|

| Devoting personal attention | Investing in person‐centered care, nearness, familiarity, meaningful activities, connecting to the people cared for and sensory stimulation; complying with individual wishes | “Attention, listening, warm care for the resident” | 198 |

| Supporting families | Having conversations; providing information and explanations; providing emotional support (also during the dying process) | “Attention for loved ones who are present during the dying process” | 68 |

| Safeguarding quality of care | Creating a calm atmosphere and taking one’s time to provide good care; having care matters in order; being well‐prepared | “Updating care files/work plans to maintain/improve quality of care” | 49 |

| Deepening one’s knowledge | Getting (self)educated; obtaining information; deepening one’s understanding of cases | “Staying up‐to‐date with literature, newsletters” | 16 |

| Exchanging and reflecting on experiences with colleagues | Discussing cases; learning from or acting as a supervisor for colleagues; communicating and collaborating with colleagues within and outside one’s own discipline. | “Discussing clients or general cases with colleagues” | 15 |

(Fragments within) single answers could contribute to establishing multiple categories.

Discussion

This study explored and compared the needs of nursing staff with different educational backgrounds and from different settings and highlighted that dealing with challenging behaviors and managing pain were the most frequently reported needs in palliative caregiving for persons with dementia. Dealing with family disagreement in end‐of‐life decision making was the most frequently reported need in end‐of‐life communication. Nursing staff preferred opportunities for peer‐to‐peer learning and “real life” exchange with colleagues. Nursing staff with different educational levels and working in home care or in the nursing home reported mostly the same needs.

The findings suggest that increasing feelings of competence among nursing staff may require interventions that focus on dealing with challenging behaviors and pain in particular. Difficulties in dealing with behaviors likely relate to difficulties in communication, and both require familiarity with the individual (Bolt, van der Steen, Schols, Zwakhalen, Pieters, & Meijers, 2019). Certain behaviors may be due to underlying pain (Malara et al., 2016; Pieper et al., 2013), and communication difficulties leave staff unsure about interpreting individual care needs (Midtbust, Alnes, Gjengedal, & Lykkeslet, 2018a; Monroe, Parish, & Mion, 2015). The finding that nursing staff want to devote personal attention and make a connection with the individual further supports previous statements about the importance of a person‐centered approach in dementia care (Kitwood & Bredin, 1992) and in palliative care for persons with dementia (Bolt, van der Steen, Schols, Zwakhalen, Pieters, & Meijers, 2019; van der Steen et al., 2014). However, as in this study, nursing staff previously expressed concerns on how to achieve this with increasing work demands, scarce resources, and a lack of time (Midtbust, Alnes, Gjengedal, & Lykkeslet, 2018b; Smythe et al., 2017). Initiatives aimed at increasing competence and person‐centered palliative care may require reconsideration of the organizational culture of long‐term care and awareness about palliative care for persons with dementia to be successful (Kaplan et al., 2010; Midtbust et al., 2018b; Sommerbakk, Haugen, Tjora, Kaasa, & Hjermstad, 2016).

Dealing with disagreement between family members in decision making about care and treatment was a prominent issue for nursing staff from both settings. Nursing staff may encounter families that are unwilling to comply with advance directives or decisions that are not in the person’s best interest as perceived by staff (Hill, Savundranayagam, Zecevic, & Kloseck, 2018). A comparison of six European countries demonstrated that achieving full consensus (as perceived by nurses) about end‐of‐life care and treatments of nursing home residents among all involved in care agreements ranged from 60% in Finland to 86% in England, with the Netherlands rating in between with 78% (ten Koppel et al., 2018). Conflict between family members or between staff and family may result from poor communication or families’ lack of understanding or disagreement about appropriate care and treatment, and forms a barrier to effective palliative care for persons with dementia (Erel et al., 2017; Lopez, 2007). Current findings also highlight a particular need for competencies in dealing with family conflicts in end‐of‐life decision making emotionally. This underexposed topic is an important direction for future research and for the development of interventions.

Overall, home care staff felt less competent than nursing home staff in providing palliative care for persons with dementia. Moreover, home care staff less frequently indicated that they had had additional training in dementia care, and they reported more support needs in communicating with and feeling comfortable in caring for persons with (severe) dementia. These findings are important, and they point out that more training on dementia and end‐of‐life care is needed, in particular for home care staff (D'Astous et al., 2019). The population cared for at home might differ from the nursing home population, possibly requiring different levels of competence from nursing staff. Nonetheless, Hasson and Arnetz (2008) found that in Sweden both settings involve similar care tasks and that staff from both settings have similar development needs. Correspondingly, the current findings point to similar needs across the settings, which may have important implications for the development of interventions that target both settings.

Self‐perceived competence did not differ between the different educational levels. Similarly, a previous study found that educational level did not predict self‐perceived competence among home care staff (Grönroos, & Perälä, 2008). Self‐assessment of competence is valued in nursing (Fereday & Muir‐Cochrane, 2006), Nonetheless, the concept of competence is ill defined, and it has been argued that nurses cannot judge what they ought to know and what they do and do not know (Cowan, Norman, & Coopamah, 2005). Higher‐educated nursing staff are generally more trained in self‐reflection and might be more conscious of their own competence and incompetence, which may explain the findings.

In both settings, the rapid digitalization of health care challenges nursing staff’s technological skills and induces changes in care practice (Konttila et al., 2019). Considering forms of support, instead of endorsing the use of apps or other technological aides, nursing staff emphasize the need for having “real” conversations and exchanging knowledge and experiences with colleagues. This is an important finding considering the contemporary digital era. There is sufficient literature highlighting the value of peer learning among undergraduate nurses, suggesting it contributes to critical thinking, facilitates a safe learning environment, and raises feelings of being emotionally supported (Irvine, Williams, & McKenna, 2018; Nelwati, Abdullah, & Chan, 2018). Less is known about formal and informal peer‐to‐peer learning among employed nursing staff. Particularly when caring for people with complex care needs, sharing experiences and reflecting with peers might be essential for emotional and informational support and to overcome challenges in caregiving. Future research may explore the shaping of efficient peer learning among nursing staff within an increasingly technology‐driven work environment.

Limitations

This study is limited by its nonrandom sampling technique, which was administered to comply with the General Data Protection Regulation (Official Journal of the European Union, 2018). Self‐selection bias might have occurred (e.g., a special interest in palliative care or dementia), diminishing generalizability of the findings to the entire population of interest (Etikan, Musa, & Alkassim, 2016). Nonetheless, a partial‐response analysis suggests that partial responders (who may share characteristics with nonresponders) were similar, although more experienced and certified or registered staff were more likely to respond fully. The representation of certified nurse assistants is consistent with the general staffing levels in Dutch long‐term care (Arbeid in Zorg en Welzijn [AZW], 2016; Backhaus et al., 2017). The mean age and proportion of females in the sample are comparable to national statistics (AZW, 2016). This study does not provide information on the reliability of the questionnaire. The goal of the current study was to rank nursing staff’s needs by counting item frequencies, rather than measuring a single construct for individual needs. Different forms of reliability (i.e., internal consistency, inter‐rater, test‐retest) were considered unsuitable, and parallel form reliability data were not obtained in this study as no equivalent instrument existed.

Conclusions

Nursing staff with varying educational levels and working in the nursing home or home setting reported similar support needs in providing palliative care for persons with dementia. Dealing with challenging behaviors, pain, and family conflict were the most pressing support needs for proper caregiving. Nursing staff expressed a desire to connect with persons with dementia when imagining they would be given more time for caregiving. Organizational support and awareness is needed to enable nursing staff to devote personal attention and to establish meaningful care relationships. Nursing staff preferred and emphasized the need for peer‐to‐peer learning and exchanging knowledge and experiences with colleagues. Professionalizing palliative care for persons with dementia in both settings requires consideration of explicit needs and preferences for support. To increase the competence of nursing staff in providing palliative care for persons with dementia, interventions with a similar focus may address the needs of a heterogeneous group of nurses and nurse assistants, working in the home or nursing home setting.

Supporting information

Table S1. Questionnaire.

Table S2. Frequencies of Reported Needs in Descending Order (Total) and Specified per Educational Level and Setting.

Table S3. Frequencies of Preferred Forms of Support in Descending Order (Total) and Specified per Educational Level and Setting.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the linking pins from The Living Lab in Ageing & Long‐Term Care Zuid Limburg (AWO‐ZL), the University Network for the Care sector Zuid‐Holland (UNC‐ZH), the Scientific Center for Care and Welfare (Tranzo), Avoord, and nursing staff from the care organizations Envida, Vivantes, and Zuyderland Zorgcentra for recruiting participants for this study. We thank the Dutch Nurses' Association (V&VN), the National Survey of Care Indicators (LPZ), and Alzheimer Nederland for the national dissemination of the survey. We would like to thank Irma Mujezinovic and Joanna Houtermans for their efforts in translating the questionnaire.

Funding for this study was obtained from ZonMw, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (Palliantie; grant number 844001405).

Clinical Resources.

Alzheimer’s Association. Professionals. https://www.alz.org/professionals

European Association for Palliative Care. Palliative care for older people: Better practices. https://www.eapcnet.eu/eapc-groups/archives/task-forces-archives/older-people-better-practices

Marie Curie. Palliative care knowledge zone. https://www.mariecurie.org.uk/professionals/palliative-care-knowledge-zone

Continuing Education Journal of Nursing Scholarship is pleased to offer readers the opportunity to earn credit for its continuing education articles. Learn more here: https://www.sigmamarketplace.org/journaleducation

References

- Abdi, H. (2010). Holm’s sequential Bonferroni procedure. Encyclopedia of Research Design, 1(8), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Albers, G. , Francke, A. L. , de Veer, A. J. , Bilsen, J. , & Onwuteaka‐Philipsen, B. D. (2014). Attitudes of nursing staff towards involvement in medical end‐of‐life decisions: A national survey study. Patient Education and Counseling, 94(1), 4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbeid in Zorg en Welzign . (2016). Arbeid in Zorg en Welzijn 2016 Eindrapport. Retrieved from https://www.azwinfo.nl/handlers/ballroom.ashx?function=download%26xml:id=244 [Google Scholar]

- Backhaus, R. (2017). Thinking beyond numbers: Nursing staff and quality of care in nursing homes (PhD thesis). Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Backhaus, R. , van Rossum, E. , Verbeek, H. , Halfens, R. J. , Tan, F. E. , Capezuti, E. , & Hamers, J. P. (2017). Relationship between the presence of baccalaureate‐educated RNs and quality of care: A cross‐sectional study in Dutch long‐term care facilities. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson, M. (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open, 2, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bolt, S. R. , van der Steen, J. T. , Schols, J. M. G. A. , Zwakhalen, S. M. G. , & Meijers, J. M. M. (2019). What do loved ones value most in end‐of‐life care for people with dementia? A qualitative exploration. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 25(9), 432–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolt, S. R. , van der Steen, J. T. , Schols, J. M. G. A. , Zwakhalen, S. M. G. , Pieters, S. , & Meijers, J. M. M. (2019). Nursing staff needs in providing palliative care for people with dementia at home or in long‐term care facilities: A scoping review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 96, 143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolt, S. R. , Verbeek, L. , Meijers, J. M. M. , & van der Steen, J. T. (2019). Families' experiences with end‐of‐life care in nursing homes and associations with dying peacefully with dementia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 20(2), 268–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan, D. T. , Norman, I. , & Coopamah, V. P. (2005). Competence in nursing practice: A controversial concept—A focused review of literature. Nurse Education Today, 25(5), 355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Astous, V. , Abrams, R. , Vandrevala, T. , Samsi, K. , & Manthorpe, J. (2019). Gaps in understanding the experiences of homecare workers providing care for people with dementia up to the end of life: A systematic review. Dementia, 18(3), article 1471301217699354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erel, M. , Marcus, E.‐L. , & Dekeyser‐Ganz, F. (2017). Barriers to palliative care for advanced dementia: A scoping review. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 6(4), 365–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etikan, I. , Musa, S. A. , & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Fereday, J. , & Muir‐Cochrane, E. (2006). The role of performance feedback in the self‐assessment of competence: A research study with nursing clinicians. Collegian, 13(1), 10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grönroos, E. , & Perälä, M. L. (2008). Self‐reported competence of home nursing staff in Finland. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 64(1), 27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson, H. , & Arnetz, J. E. (2008). Nursing staff competence, work strain, stress and satisfaction in elderly care: A comparison of home‐based care and nursing homes. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17(4), 468–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, S. A. , Smalbrugge, M. , Galindo‐Garre, F. , Hertogh, C. M. P. M. , & van der Steen, J. T. (2015). From admission to death: Prevalence and course of pain, agitation, and shortness of breath, and treatment of these symptoms in nursing home residents with dementia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 16(6), 475–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, E. , Savundranayagam, M. Y. , Zecevic, A. , & Kloseck, M. (2018). Staff perspectives of barriers to access and delivery of palliative care for persons with dementia in long‐term care. American Journal of Alzheimers Disease and Other Dementias, 33(5), 284–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine, S. , Williams, B. , & McKenna, L. (2018). Near‐peer teaching in undergraduate nurse education: An integrative review. Nurse Education Today, 70, 60–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, H. C. , Brady, P. W. , Dritz, M. C. , Hooper, D. K. , Linam, W. M. , Froehle, C. M. , & Margolis, P. (2010). The influence of context on quality improvement success in health care: A systematic review of the literature. Milbank Quarterly, 88(4), 500–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitwood, T. , & Bredin, K. (1992). Towards a theory of dementia care: Personhood and well‐being. Ageing & Society, 12, 269–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konttila, J. , Siira, H. , Kyngas, H. , Lahtinen, M. , Elo, S. , Kaariainen, M. , … Mikkonen, K. (2019). Healthcare professionals' competence in digitalisation: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(5–6), 745–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazenby, M. , Ercolano, E. , Schulman‐Green, D. , & McCorkle, R. (2012). Validity of the end‐of‐life professional caregiver survey to assess for multidisciplinary educational needs. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 15(4), 427–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, R. P. (2007). Suffering and dying nursing home residents: Nurses' perceptions of the role of family members. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing, 9(3), 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Maarse, J. A. M. , & Jeurissen, P. P. (2016). The policy and politics of the 2015 long‐term care reform in the Netherlands. Health Policy, 120(3), 241–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malara, A. , De Biase, G. A. , Bettarini, F. , Ceravolo, F. , Di Cello, S. , Garo, M. , … Rispoli, V. (2016). Pain assessment in elderly with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 50(4), 1217–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midtbust, M. H. , Alnes, R. E. , Gjengedal, E. , & Lykkeslet, E. (2018a). A painful experience of limited understanding: Healthcare professionals' experiences with palliative care of people with severe dementia in Norwegian nursing homes. BMC Palliative Care, 17(1), 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midtbust, M. H. , Alnes, R. E. , Gjengedal, E. , & Lykkeslet, E. (2018b). Perceived barriers and facilitators in providing palliative care for people with severe dementia: The healthcare professionals' experiences. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, S. L. , Teno, J. M. , Kiely, D. K. , Shaffer, M. L. , Jones, R. N. , Prigerson, H. G. , … Hamel, M. B. (2009). The clinical course of advanced dementia. New England Journal of Medicine, 361(16), 1529–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe, T. B. , Parish, A. , & Mion, L. C. (2015). Decision factors nurses use to assess pain in nursing home residents with dementia. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 29(5), 316–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelwati, Abdullah, K. L. , & Chan, C. M. (2018). A systematic review of qualitative studies exploring peer learning experiences of undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Education Today, 71, 185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuffic . (2019). Dutch grading system. Retrieved from https://www.studyinholland.nl/life-in-holland/dutch-grading-system [Google Scholar]

- Official Journal of the European Union . (2018). Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). [Google Scholar]

- Perrar, K. M. , Schmidt, H. , Eisenmann, Y. , Cremer, B. , & Voltz, R. (2015). Needs of people with severe dementia at the end‐of‐life: A systematic review. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 43(2), 397–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieper, M. J. , van Dalen‐Kok, A. H. , Francke, A. L. , van der Steen, J. T. , Scherder, E. J. , Husebo, B. S. , & Achterberg, W. P. (2013). Interventions targeting pain or behaviour in dementia: A systematic review. Ageing Research Reviews, 12(4), 1042–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, A. , Eccleston, C. , Annear, M. , Elliott, K. E. , Andrews, S. , Stirling, C. , … McInerney, F. (2014). Who knows, who cares? Dementia knowledge among nurses, care workers, and family members of people living with dementia. Journal of Palliative Care, 30(3), 158–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saks, K. , Tiit, E. M. , Verbeek, H. , Raamat, K. , Armolik, A. , Leibur, J. , … Soto, M. (2015). Most appropriate placement for people with dementia: Individual experts' vs. expert groups' decisions in eight European countries. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(6), 1363–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smythe, A. , Jenkins, C. , Galant‐Miecznikowska, M. , Bentham, P. , & Oyebode, J. (2017). A qualitative study investigating training requirements of nurses working with people with dementia in nursing homes. Nurse Education Today, 50, 119–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommerbakk, R. , Haugen, D. F. , Tjora, A. , Kaasa, S. , & Hjermstad, M. J. (2016). Barriers to and facilitators for implementing quality improvements in palliative care—Results from a qualitative interview study in Norway. BMC Palliative Care, 15, 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surr, C. A. , Gates, C. , Irving, D. , Oyebode, J. , Smith, S. J. , Parveen, S. , … Dennison, A. (2017). Effective dementia education and training for the health and social care workforce: A systematic review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 87(5), 966–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Koppel, M. , Pasman, H. R. W. , van der Steen, J. T. , van Hout, H. P. J. , Kylänen, M. , Van den Block, L. , … PACE . (2018). 10th World Research Congress of the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC). Palliative Medicine , 32(1, Suppl.), 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toles, M. , Song, M.‐K. , Lin, F.‐C. , & Hanson, L. C. (2018). Perceptions of family decision‐makers of nursing home residents with advanced dementia regarding the quality of communication around end‐of‐life care. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 19(10), 879–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Steen, J. T. , Radbruch, L. , Hertogh, C. M. , de Boer, M. E. , Hughes, J. C. , Larkin, P. , … Volicer, L. (2014). White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: A Delphi study and recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care. Palliative Medicine, 28(3), 197–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek, H. , Zwakhalen, S. M. G. , Schols, J. M. G. A. , & Hamers, J. P. H. (2013). Keys to successfully embedding scientific research in nursing homes: A win‐win perspective. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 14(12), 855–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, E. , George Kernohan, W. , Hasson, F. , Howard, V. , & McLaughlin, D. (2006). The palliative care education needs of nursing home staff. Nurse Education Today, 26(6), 501–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (n.d.). WHO definition of palliative care . Retrieved from http://http:/www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Questionnaire.

Table S2. Frequencies of Reported Needs in Descending Order (Total) and Specified per Educational Level and Setting.

Table S3. Frequencies of Preferred Forms of Support in Descending Order (Total) and Specified per Educational Level and Setting.

Nursing Staff Needs in Providing Palliative Care for Persons With Dementia at Home or in Nursing Homes: A Survey

Nursing Staff Needs in Providing Palliative Care for Persons With Dementia at Home or in Nursing Homes: A Survey