Abstract

This multicentre pilot study investigated the role of peroperative carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)‐specific fluorescence imaging during cytoreductive surgery–hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy surgery in peritoneal metastasized colorectal cancer. A correct change in peritoneal carcinomatosis index (PCI) owing to fluorescence imaging was seen in four of the 14 included patients. The use of SGM‐101 in patients with peritoneally metastasized colorectal carcinoma is feasible, and allows intraoperative detection of tumour deposits and alteration of the PCI.

![]()

Augmented reality guidance

Introduction

The peritoneal cavity is the second most common location for the development of isolated metastases of colorectal origin1, 2. Peritoneal metastatic disease was once considered an end‐stage disease with a poor median survival of several months after palliative treatment3, 4, 5. However, survival rates have improved since the introduction of cytoreductive surgery (CRS) with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC). Numerous studies have identified the peritoneal carcinomatosis index (PCI), a measure of the extent of peritoneal disease, and completeness of CRS as important prognostic factors for oncological outcome6, 7, 8, 9, 10. However, identification of peritoneal lesions, especially in diffuse miliary disease, and discriminating between benign fibrosis (common after surgery and neoadjuvant therapy) and malignant lesions can be challenging. Therefore, a reliable method for identifying (small) peritoneal tumour deposits could be of great importance to achieving complete CRS.

Near‐infrared (NIR) fluorescence imaging techniques using tumour‐targeting tracers may aid in this respect. In recent years, fluorescence‐guided surgery has gained interest, and has been able to provide surgeons with real‐time feedback and visualization of malignant tissues11, 12, 13, 14. SGM‐101, a carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)‐specific tumour‐targeted fluorescent agent, can be used for fluorescence imaging to identify malignant tissue of colorectal origin. The fact that CEA is overexpressed in more than 90 per cent of all colorectal cancer cells, with limited expression in benign tissue, makes it an ideal target for fluorescence imaging of colorectal neoplastic lesions15, 16, 17. The aims of this study were to evaluate the effectiveness of fluorescence imaging with SGM‐101 for the detection of peritoneal metastases of colorectal origin and the potential influence on intraoperative decision‐making. The main objective was to distinguish whether the PCI, and thus the completeness of cytoreduction, can be changed with SGM‐101 and fluorescence imaging.

Methods

An exploratory, multicentre pilot study was performed in patients with peritoneal metastatic colorectal cancer. Patients were scheduled for CRS‐HIPEC, and SGM‐101 was administered intravenously 4–6 days before surgery. During surgery, a clinical PCI was determined using standard tactile and visual feedback. Subsequently, a fluorescence‐based peritoneal carcinomatosis index (fPCI) was determined using the Quest Spectrum® fluorescence camera system (Quest Medical Imaging, Middenmeer, the Netherlands), an imaging system dedicated to fluorescence imaging in the 700‐nm NIR spectrum. Both clinically suspected malignant and fluorescent lesions were resected and assessed by the pathologist. Changes in the PCI and surgical plan, and the concordance between clinical detection and fluorescence imaging were correlated with the histopathological analysis. Details of the methods can be found in Appendix S1 (supporting information).

Results

Between January 2017 and January 2019, 14 patients diagnosed with peritoneal metastases of colorectal origin were included in this study. The clinical characteristics and PCI outcomes are summarized in Tables S1 and S2 respectively (supporting information). Of the 14 patients, six were diagnosed with a locally advanced or recurrent rectal tumour with peritoneal metastases, and received neoadjuvant treatment consisting of either induction chemotherapy followed by chemoradiotherapy (CRT) or CRT alone. Nine patients presented with synchronous and five with metachronous peritoneal metastases. SGM‐101 was well tolerated in all patients; no allergic or anaphylactic reactions were reported during or after SGM‐101 administration. CRS‐HIPEC was executed successfully in 12 of the 14 patients. Only an exploratory laparotomy was performed in two patients, as the disease was too extensive and unresectable. However, for clinical purposes, clinical and fluorescence‐based PCI inspections were performed, and biopsies were taken that were also investigated for fluorescence signal.

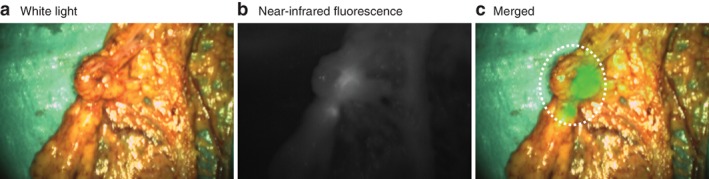

Median clinical PCI was 7 (2–39) and median fPCI was 6.5 (2–39). The PCI changed owing to fluorescence imaging in seven patients. In six of these patients, the fPCI was higher than the clinical PCI, which was accurate in four patients, as confirmed by histopathological analysis. One patient had a PCI increase from 10 to 11 owing to a fluorescent lesion on the mesentery of the proximal ileum, which was not considered malignant on traditional inspection or palpation. The second patient had multiple additional lesions in the omentum that were not identified by standard visual techniques, but only by fluorescence imaging, increasing the PCI from 4 to 6 (Fig. 1 ). In the third and fourth patients, fluorescent positive lesions on the left upper peritoneum and peritoneum of the bladder increased the PCI from 9 to 10 and from 2 to 4 respectively. Both lesions were visible, but not considered malignant on initial inspection and palpation. In two patients, the PCI change due to fluorescence imaging was incorrect. A false‐positive lesion on the liver capsule, detected by fluorescence imaging, led to an incorrect PCI increase from 4 to 5 and unnecessary resection of a superficial lesion on the liver capsule. The other patient, who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy according to the CAIRO‐6 trial protocol, had a complete response. Six lesions were resected, which were all clinically suspect for malignancy; five of these lesions were fluorescent. Histopathological analysis confirmed that all lesions were benign, containing collagen‐rich connective tissue, hypervascularization and an inflammatory reaction. One patient had a decrease in PCI owing to fluorescence imaging. This patient had a PCI of 5 and a fPCI of 4; however, after histopathological analysis the PCI was 3. Fluorescence imaging correctly identified two lesions (mesentery of the upper and lower ileum) as benign, but a false‐positive lesion in the omentum eventually led to an incorrect fPCI. Both lesions on the mesentery of the ileum were still resected as they were clinically suspicious; bowel resection was not included.

Figure 1.

Ex vivo fluorescence imaging of a lesion in the omentum Ex vivo a white light, b near‐infrared (NIR) fluorescence and c merged white light and NIR fluorescence images of a lesion in the omentum detected in vivo, which was not suspicious clinically, resulting in a change in peritoneal carcinomatosis index from 4 to 6. Histopathological examination confirmed that this lesion was malignant.

A total of 103 lesions were excised from the 14 patients. Histopathology revealed that 66 of these lesions were malignant and 37 were benign. Of the 103 lesions, 79 were identified with fluorescence. Sixty‐five of the 66 malignant lesions were fluorescent (true positive), resulting in a sensitivity of 98.5 per cent. No fluorescence was observed in 23 of the 37 benign lesions (true negative), resulting in a specificity of 62.2 per cent. This led to an accuracy of fluorescence imaging of 85.4 per cent. Nevertheless, 14 lesions showed a false‐positive signal and one lesion was false negative, resulting in a positive predictive value of 82.3 per cent and a negative predictive value of 95.8 per cent (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Performance of fluorescence imaging for detection of lesions

| Malignant | Benign | Total | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Accuracy (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence positive | 65 (TP) | 14 (FP) | 79 | |||||

| Fluorescence negative | 1 (FN) | 23 (TN) | 24 | |||||

| Total | 66 | 37 | 103 | 98.5 (65 of 66) | 62.2 (23 of 37) | 82.3 (65 of 79) | 95.8 (23 of 24) | 85.4 (88 of 103) |

TP, true positive; FP, false positive; FN, false negative; TN, true negative; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value.

Discussion

SGM‐101 had a high negative predictive value of 95.8 per cent and an accuracy of 85.4 per cent, which is in accordance with previous and concurrent studies with SGM‐101, emphasizing that this technique is consistently reliable13. The selection of patients with peritoneal metastases of colorectal origin who might benefit from CRS‐HIPEC is a major challenge. Several studies7, 8, 18, 19 have demonstrated that the extent of peritoneal disease, best measured with the PCI, is one of the most important prognostic factors for increased local and distant recurrence rates and diminished survival. Completeness of cytoreductive surgery is another important prognostic factor for improved oncological outcomes9, 10, 20. In a retrospective analysis of 523 patients, Elias and colleagues6 showed that, besides lymph node status, surgical experience and adjuvant chemotherapy, PCI and the completion of cytoreduction were independent prognostic factors for disease‐free survival. With this in mind, it is apparent that adequate detection of peritoneal deposits is key to determining whether CRS‐HIPEC is feasible and improves the completeness of cytoreduction. Even though a change in PCI might not fully reflect the benefit of tumour deposit detection with fluorescence imaging, because the additional information about, for example, an extra lesion, might not alter the PCI, it is still beneficial for a more complete cytoreduction. The fact that this technique was able to detect additional lesions that were not considered to be malignant based on standard visual and tactile feedback is of great importance. The PCI increased accurately based on fluorescence imaging in almost one‐third of the patients, which led to resection of lesions that would otherwise have been left behind. These results demonstrate the potential benefit of CEA‐specific fluorescence imaging, as the detection of additional lesions with the help of this technique might result in more complete cytoreduction and subsequently improved oncological outcomes.

Collaborators

M. Kusters, L. S. F. Boogerd (Amsterdam University Medical Centers, location VUmc, Amsterdam); D. P. Schaap, E. L. K. Voogt, G. A. P. Nieuwenhuijzen, H. J. T. Rutten, I. H. J. T. de Hingh, J. W. A. Burger, S. W. Nienhuijs (Catharina Hospital, Eindhoven); K. S. de Valk, R. P. J. Meijer, J. Burggraaf (Center for Human Drug Research, Leiden); A. R. M. Brandt‐Kerkhof, C. Verhoef, E. V. E. Madsen, J. P. van Kooten (Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam); B. Framery, M. Gutowski, A. Pèlegrin, F. Cailler (SurgiMab, Montpellier); I. van Lijnschoten (PAMM Laboratory for Pathology and Medical Microbiology, Eindhoven); A. L. Vahrmeijer, C. E. S. Hoogstins, L. S. F. Boogerd, K. S. de Valk, M. M. Deken, R. P. J. Meijer (Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden).

Supporting information

Appendix S1: Supporting information

Acknowledgements

D.P.S. and K.S.d.V. contributed equally to this article. The Centre for Human Drug Research (Leiden, Netherlands; a not‐for‐profit foundation) and the Leiden University Medical Centre (Leiden, Netherlands) received the study drug and equipment for the execution of this study from SurgiMab (Montpellier, France). This trial was registered in http://clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02973672).

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

M. Kusters, Email: m.kusters@amsterdamumc.nl.

on behalf of the SGM‐101 study group:

M. Kusters, L. S. F. Boogerd, D. P. Schaap, E. L. K. Voogt, G. A. P. Nieuwenhuijzen, H. J. T. Rutten, I. H. J. T. de Hingh, J.W. A. Burger, S.W. Nienhuijs, K. S. de Valk, R. P. J. Meijer, J. Burggraaf, A. R. M. Brandt‐Kerkhof, C. Verhoef, E. V. E. Madsen, J. P. van Kooten, B. Framery, M. Gutowski, A. PM‐hlegrin, F. Cailler, I. van Lijnschoten, A. L. Vahrmeijer, C. E. S. Hoogstins, L. S. F. Boogerd, K. S. de Valk, M. M. Deken, and R. P. J. Meijer

References

- 1. van Gestel YR, de Hingh IH, van Herk‐Sukel MP, van Erning FN, Beerepoot LV, Wijsman JH et al Patterns of metachronous metastases after curative treatment of colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol 2014; 38: 448–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hugen N, van de Velde CJH, de Wilt JHW, Nagtegaal ID. Metastatic pattern in colorectal cancer is strongly influenced by histological subtype. Ann Oncol 2014; 25: 651–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lemmens VE, Klaver YL, Verwaal VJ, Rutten HJ, Coebergh JWW, de Hingh IH. Predictors and survival of synchronous peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin: a population‐based study. Int J Cancer 2011; 128: 2717–2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Razenberg LG, Lemmens VE, Verwaal VJ, Punt CJ, Tanis PJ, Creemers GJ et al Challenging the dogma of colorectal peritoneal metastases as an untreatable condition: results of a population‐based study. Eur J Cancer 2016; 65: 113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Quere P, Facy O, Manfredi S, Jooste V, Faivre J, Lepage C et al Epidemiology, management, and survival of peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer: a population‐based study. Dis Colon Rectum 2015; 58: 743–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Elias D, Gilly F, Boutitie F, Quenet F, Bereder JM, Mansvelt B et al Peritoneal colorectal carcinomatosis treated with surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy: retrospective analysis of 523 patients from a multicentric French study. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Simkens GA, van Oudheusden TR, Nieboer D, Steyerberg EW, Rutten HJ, Luyer MD et al Development of a prognostic nomogram for patients with peritoneally metastasized colorectal cancer treated with cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC. Ann Surg Oncol 2016; 23: 4214–4221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Glehen O, Kwiatkowski F, Sugarbaker PH, Elias D, Levine EA, De Simone M et al Cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the management of peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer: a multi‐institutional study. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 3284–3292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Verwaal VJ, van Tinteren H, van Ruth S, Zoetmulder FAN. Predicting the survival of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin treated by aggressive cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Br J Surg 2004; 91: 739–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Esquivel J, Piso P, Verwaal V, Bachleitner‐Hofmann T, Glehen O, González‐Moreno S et al American Society of Peritoneal Surface Malignancies opinion statement on defining expectations from cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in patients with colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol 2014; 110: 777–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hoogstins CES, Boogerd LSF, Sibinga Mulder BG, Mieog JSD, Swijnenburg RJ, van de Velde CJH et al Image‐guided surgery in patients with pancreatic cancer: first results of a clinical trial using SGM‐101, a novel carcinoembryonic antigen‐targeting, near‐infrared fluorescent agent. Ann Surg Oncol 2018; 25: 3350–3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harlaar NJ, Koller M, de Jongh SJ, van Leeuwen BL, Hemmer PH, Kruijff S et al Molecular fluorescence‐guided surgery of peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin: a single‐centre feasibility study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016; 1: 283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boogerd LSF, Hoogstins CES, Schaap DP, Kusters M, Handgraaf HJM, van der Valk MJM et al Safety and effectiveness of SGM‐101, a fluorescent antibody targeting carcinoembryonic antigen, for intraoperative detection of colorectal cancer: a dose‐escalation pilot study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 3: 181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tipirneni KE, Warram JM, Moore LS, Prince AC, de Boer E, Jani AH et al Oncologic procedures amenable to fluorescence‐guided surgery. Ann Surg 2017; 266: 36–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tiernan JP, Perry SL, Verghese ET, West NP, Yeluri S, Jayne DG et al Carcinoembryonic antigen is the preferred biomarker for in vivo colorectal cancer targeting. Br J Cancer 2013; 108: 662–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hammarström S. The carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) family: structures, suggested functions and expression in normal and malignant tissues. Semin Cancer Biol 1999; 9: 67–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boonstra MC, de Geus SW, Prevoo HA, Hawinkels LJ, van de Velde CJ, Kuppen PJ et al Selecting targets for tumor imaging: an overview of cancer‐associated membrane proteins. Biomark Cancer 2016; 8: 119–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jacquet P, Sugarbaker PH. Clinical research methodologies in diagnosis and staging of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis In Peritoneal Carcinomatosis: Principles of Management, Sugarbaker PH (ed.). Boston: Springer, 1996: 359–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. da Silva RG, Sugarbaker PH. Analysis of prognostic factors in seventy patients having a complete cytoreduction plus perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer. J Am Coll Surg 2006; 203: 878–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shen P, Hawksworth J, Lovato J, Loggie BW, Geisinger KR, Fleming RA et al Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy with mitomycin C for peritoneal carcinomatosis from nonappendiceal colorectal carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2004; 11: 178–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1: Supporting information