Abstract

An aging population, decreased activity levels and increased combat injuries, have led to an increase in critical sized bone defects. As more defects are treated using allografts, which is the current standard of care, the deficiencies of allografts are becoming more evident. Allografts lack the angiogenic potential to induce sufficient vasculogenesis to counteract the hypoxic environment associated with critical sized bone defects. In this study, aptamer-functionalized fibrin hydrogels (AFH), engineered to release vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), were evaluated for their material properties, growth factor release kinetics, and angiogenic and osteogenic potential in vivo. Aptamer functionalization to native fibrin did not result in significant changes in biocompatibility or hydrogel gelation. However, aptamer functionalization of fibrin did improve the release kinetics of VEGF from AFH and, when compared to FH, reduced the diffusivity and extended the release of VEGF several days longer. VEGF released from AFH, in vivo, increased vascularization to a greater degree, relative to VEGF released from FH, in a murine critical-sized cranial defect. Defects treated with AFH loaded with VEGF, relative to nonhydrogel loaded controls, showed a nominal increase in osteogenesis. Together, these data suggest that AFH more efficiently incorporates and retains VEGF in vitro and in vivo, which then enhances angiogenesis and osteogenesis to a greater extent in vivo than FH.

Keywords: bone regeneration, drug delivery, growth factor, biomaterial, regenerative medicine

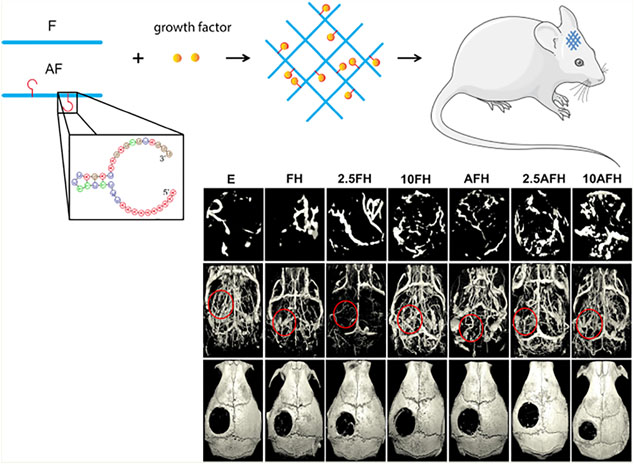

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

Critical sized bone defects, defects that do not heal completely without intervention, continue to be an issue in clinical settings. Biomaterials used to treat critical sized bone defects do exceptionally well at inducing angiogenesis or osteogenesis, but rarely both, and fail roughly 13% of the time.1 Many materials used impair self-healing, which is problematic when determining effective treatments for critical sized bone defects.2 With the number of critical sized bone defects rising due to the increased prevalence of diseases such as osteoporosis, resulting in more severely comminuted fractures, and high-energy injuries such as those commonly seen in the armed forces it is important to provide viable solutions to meet this growing need.2–7 The development of new scaffolds, grafts, and other biomaterials has led to alternate forms of treatment for critical sized bone defects and bone nonunion.2,8–10 However, bone allografts continue to be the most widely used graft material to heal critical sized defects.

While allografts are often used to treat critical sized defects in both load bearing and nonload bearing situations, they present several problems. For instance, allografts often do not resolve the hypoxic environment typically associated with large bone defects, because they fail to vascularize fully. Additionally, infection and rejection, often caused by the innate immune response to leftover cellular debris in the grafts themselves, prevent complete bone union and ossification.11,12 If complete bone union is not achieved, then the patient risks a host of complications ranging from defect site pain to local or possible systemic infection.13 The use of biomaterials in tandem with allografts allows for an improved angiogenic and osteogenic response, providing a greater healing response than allografts alone.3,14 Current biomaterials are adequate at restoring both structure and function in smaller bone defects but often lack the angiogenic potential needed to sufficiently vascularize critical sized bone defects.15 Thus, the hypoxic environment commonly associated with these defects is not resolved, preventing complete healing.2,11,16 Hydrogels, a promising group of biomaterials that mimic the extracellular matrix and are conducive to both angiogenesis and osteogenesis, are being explored as a potential solution to this problem.17 Hydrogels are flexible and multifaceted, allowing them to be tailored to improve various properties. Unfortunately, because hydrogels lack the mechanical stability needed for load-bearing defects, hydrogels are instead utilized in conjunction with a mechanically competent scaffold in load bearing situations or as a filler for nonload bearing situations.18 With that stated, there are various types of hydrogels, with one of the most commonly used hydrogels being native fibrin hydrogel (FH).

Native FHs are commonly used because of their simplicity and conduciveness to cell growth. Compared to other hydrogels, FHs are highly dynamic and biocompatible, making them advantageous for numerous healing applications.19–21 In clinical application, FH forms a three-dimensional polymerized network anchored by fibroblasts, eventually becoming stiff enough to regulate wound hemostasis.19 FH has also been shown to moderately induce osteogenesis but does not enhance angiogenesis effectively, a necessity for critically sized defect repair.22 Attempts at loading FH with growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which induces endothelial cell mitogenesis and tubule formation, have had moderate success at resolving this problem. Unfortunately, FH, like other hydrogels, poorly incorporates or retains growth factors. Instead, FH exhibits a “burst release” kinetic with the majority of the growth factor being released over an initial 48 hour period.23 To solve this, we have developed a novel nucleotide aptamer-functionalized fibrin hydrogel (AFH) with improved retention and release kinetics, compared to nonaptamer-functionalized FH.

Aptamers, typically comprised of a highly specific sequence of oligonucleotides or peptides, bind to their target molecules with extremely high affinities.17,22 The engineered aptamer conjugated to fibrinogen, and with the addition of thrombin, forms AFH with an enhanced affinity for a specific growth factor.20 AFH exhibits similar structural qualities to native FH but also offers tailorable release kinetics.22 Past studies have shown that AFH loaded with VEGF can be used to enhance vascularization in skin defects, but minimal research has been done to evaluate AFH in bone regeneration and healing.20,24,25 This gap in knowledge has led us to examine how AFH loaded with VEGF affects angiogenesis and osteogenesis in a critical sized cranial bone defect.

We implanted VEGF-loaded AFHs in an established murine cranial defect model.26 We hypothesize that VEGF-loaded AFHs with improved VEGF release kinetics increase, compared to VEGF-loaded FHs, angiogenesis and osteogenesis.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

All chemicals used for aptamer functionalization and hydrogel synthesis were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Fibrinogen and thrombin were purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA). VEGF and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits for VEGF were purchased from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ). VEGF-binding aptamer and complementary sequence of VEGF-binding aptamer (Table 1) were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). Nylon sutures were purchased from Ethilon (Johnson & Johnson Medical N.V., Belgium). Radiopaque MICROFIL solution was purchased from Flow-Tech Inc. (Microfil, Flow-Tech Inc., Carver, MA). Decalcification solution was purchased from Statlabs (StatLab, McKinney, TX). Eppendorf tubes used for scanning purposes were purchased through Thermo-Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA).

Table 1.

DNA Sequence of VEGF Aptamer

| DNA name | sequence (5´→3´) |

|---|---|

| aptamer | /ThiolMC6-D/AAAAA AAAAA CCCGT CTTCC AGACA AGAGT GCAGG G |

| complementary sequence of aptamer | CCCTG CACTC TTGTC TGGAA GACGG G |

Hydrogel Preparations and Synthesis.

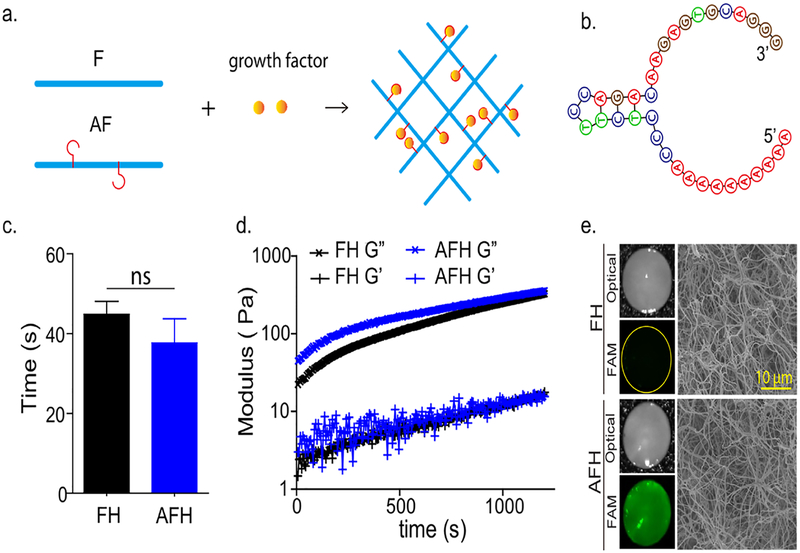

Aptamer-conjugated fibrinogen was synthesized using methods previously reported (Figure 2a).20 Briefly, 50 mg of native fibrinogen was reacted with acrylic acid N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) in NaHCO3 (0.1 M) solution for 4 hours. Unreacted NHS and byproducts were removed by washing with a 100 kDa centrifugal filter. Thiol-modified anti-VEGF aptamers were reduced in 50 mM tris(2-carboxy ethyl) phosphine hydrochloride at room temperature. The reduced aptamers were purified, and 30 nmol of aptamer reacted with 50 mg of acrylate-modified fibrinogen in Tris-HCl buffer. Then the fibrinogen conjugated with the anti-VEGF aptamer was purified with a 100 kDa centrifugal filter and stored at −20 °C for future use.

Figure 2.

Evaluation of aptamer-functionalized fibrin hydrogel properties in comparison to native fibrin hydrogels. (a) Schematic illustration of functionalization synthesis, native fibrinogen (F); aptamer-functionalized fibrinogen (AF). (b) Secondary structure of the VEGF-binding aptamer. (c) Gelation time of FH and AFH, n ≥ 3, ns = not significant. (d) Dynamic modulus. G′ loss modulus; G″, storage modulus. (e) Representative images of hydrogels. Left: Optical images of bulk hydrogels (top) and images of hydrogels stained with SYBR Safe (bottom). Right: scanning electron microscopy images.

Fibrinogen and aptamer-conjugated fibrinogen were mixed to form a pregel solution (20 mg/mL total fibrin). Thrombin and CaCl2 were then mixed to form the second pregel solution (2 U/mL of thrombin and 10 mM CaCl2). The two pregel solutions were then mixed and allowed to mature at 37 °C for 1 hour. To make VEGF-loaded hydrogels, VEGF was first added to either the fibrin solution or the aptamer-functionalized fibrin solution that was then used for hydrogel preparation. Native (no aptamer) fibrin hydrogel, with or without VEGF, was used as a control. For all of the following experiments, the molar ratio of the aptamer to VEGF in the aptamer-functionalized hydrogel was kept at 20:1.

Hydrogel Evaluation.

Gelation Time.

Twenty-five μL of aptamer-conjugated fibrinogen (4 mg/mL) was mixed with 25 μL of fibrinogen (16 mg/mL) and transferred to a BMD-QuickCoag 1004 coagulometer (BioMedica, Nova Scotia, Canada). Twenty-five μL of CaCl2 (20 mM) was mixed with 25 μL of thrombin (4 U/mL). The mixtures were allowed to equilibrate to 37 °C. Then 50 μL of the CaCl2 and thrombin solution was added to the coagulator to initiate the gelation process and the gelation process initiated on the coagulometer. Once the movement of the magnetic bar in the coagulator is stopped, gelation time was recorded. All gelation was measured at 37 °C.

Dynamic Modulus.

Twenty-five μL of aptamer-conjugated fibrinogen (4 mg/mL) was mixed with 25 μL of fibrinogen (16 mg/mL). The two parts were mixed and transferred to a Discovery HR3 rheometer (New Castle, DE). A strain sweep was performed at a frequency of 10 rad/s from 0.1% to 15% to determine the linear viscoelastic region. The dynamic modulus was determined using an oscillatory strain sweep at a strain of 1% and a frequency of 1 Hz.

Bulk Hydrogel Imaging.

Hydrogels were stained with complementary sequences (4 μM) of the VEGF-binding aptamers at room temperature. Then the hydrogels were washed with PBS and stained with SYBR Safe. After washing with PBS 3 times, the hydrogels were imaged with a Maestro Imaging System (Woburn, MA).

Scanning Electron Microscopy.

Hydrogels were fixed with a 4% paraformaldehyde solution, washed with ddH2O 3 times, frozen at −80 °C, and then lyophilized. The lyophilized materials were sputter-coated with iridium and imaged with a scanning electron microscope (Zeiss Sigma, US). For all images, a 5 kV acceleration voltage was used, and all images were taken at a working distance of 5.5 mm and a 2000 magnification.

VEGF Release Profile.

AFH loaded with 2 μM aptamer and 100 nM VEGF and native nonaptamer-functionalized FH loaded with 100 nM VEGF with diameters of 8 mm and thicknesses of 1 mm were incubated in 1 mL of release media (0.1% bovine serum albumin supplemented DPBS). The release media was collected at predetermined time points and replenished with a new release media. The collected release media was stored at −20 °C. To quantify the amount of VEGF in collected release media, ELISA was performed according to the manufacture’s protocol. The effective diffusivity of VEGF from FH and AFH was calculated using eq 127

| (1) |

where Mt is the amount of released VEGF at time t, Mo is the total amount of VEGF, Mt/Mo is the fractional release, D is the effective diffusivity, l is the thickness of the hydrogel, and n is the diffusional exponent (n = 0.5).

In vivo Evaluation.

All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines and requirements. Skeletally mature, 16-week-old male C57/B6J mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were housed in a light and temperature-controlled environment with free access to food and water. There were 7 experimental groups (Table 2). VEGF concentrations of 2.5 μg/mL and 10 μg/mL were chosen to be similar to previous literature where 2 μg/mL was used in a skin defect model with similar aptamer-functionalized hydrogels, and 10 μg/mL was used in a femoral fracture model.20,25

Table 2.

Hydrogel Treatment Groups

| experimental group | hydrogel type | VEGF concn. |

|---|---|---|

| non-hydrogel loaded control (E) | none | none |

| fibrin hydrogel (FH) | fibrin | none |

| fibrin hydrogel w/2.5 μg/mL VEGF (2.5FH) | fibrin | 2.5 μg/mL |

| fibrin hydrogel w/10 μg/mL VEGF (10FH) | fibrin | 10 μg/mL |

| aptamer-functionalized fibrin hydrogel (AFH) | aptamer-functionalized fibrin | none |

| aptamer-functionalized fibrin hydrogel w/2.5 μg/mLVEGF (2.5AFH) | aptamer-functionalized fibrin | 2.5 μg/mL |

| aptamer-functionalized fibrin hydrogel w/10 μg/mL VEGF (10AFH) | aptamer-functionalized fibrin | 10 μg/mL |

Critical Sized Cranial Defect Model.

The cranial defect was created as previously reported.28 Mice were anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane, followed with a toe pinch to confirm the depth of the anesthesia. Mice then received 0.6 mg/kg of buprenorphine to relieve pain intra- and postoperatively. An incision that extends over the majority of the dorsal skull was created, and the skin was retracted to expose the parietal bone. Using a 4 mm external diameter trephine drill bit, a critically sized defect (Figure 1) was made in the parietal bone, using caution not to extend the defect into the underlying dura mater. Thirteen μL of sterile hydrogel from each group listed in Table 2 was then injected into the defect site. An uninjected control group without hydrogel served as the negative control with 6 mice per group per time point. The hydrogel was then allowed to cure for 3 minutes before the defect site was closed using a horizontal mattress suture technique.

Figure 1.

Representative images of the critical sized bone defect. (a) A superior view of the 4 mm defect created in the left parietal bone of 16-week-old male mice at 7 days postdefect introduction with no intervention performed, (b) 14 days postdefect introduction with no intervention performed, and (c) 21 days postdefect introduction with no intervention performed. The images show little to no healing, affirming that a critical sized bone defect that will not heal without external intervention was created.

Vascular Perfusion.

After defect creation and treatment, animals were sacrificed at 7, 14, and 21 days. To assess angiogenesis, mice were perfused with a radio-opaque silicone-based contrast agent, MICROFIL, to visualize the vasculature as previously reported.28 Mice were first anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane, followed with a toe pinch to confirm the depth of the anesthesia. A catheter was placed into the apex of the left ventricle. Using a peristaltic pump (Cole Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL), 7 mL-heparinized PBS (50 U/mL) was perfused through the mouse’s vasculature at 0.7 mL/min. Complete perfusion of the vasculature was assessed by hepatic filling and by the perfused solution leaving the right atrium of the heart. Following heparin perfusion, the animal’s vessels were perfused with 7 mL of 10% neutral buffered formalin to maintain vessel structure and integrity at 0.7 mL/min. Three mL of prepared MICROFIL solution (53% MICROFIL, 42% diluent, 5% curing agent) was then perfused through the upper vasculature of the animal at 0.3 mL/min. The MICROFIL was then allowed to polymerize for 90 minutes at room temperature and then overnight at 4 °C to ensure complete polymerization. After polymerization, the head was dissected from the body and placed into 10% neutral buffered formalin until microCT analysis.

MicroCT Analysis.

MicroCT was used to examine both calcified and decalcified samples. Samples were first dried and then placed into 50 mL Eppendorf tubes. Specimens were then fixed to specimen holders in a Skyscan 1172 (Bruker, Billerica, MA). Scanning was performed at 57 kV and 87 mA. The rotational step size and zoom were set to 0.2 degrees and 17.98 μm voxels, respectively. The scan resolution was set to medium, creating a 1024 × 1024 pixel image matrix.

Images were reconstructed using a modified Feldkamp algorithm via N-Recon Software (Kontich, Belgium). Images were processed to remove noise and produce accurate structure before reconstruction. Beam hardening reduction was performed at 20%, and ring artifact reduction and postalignment were performed at various steps based on the quality of each image. The histogram setting was held at a uniform range of 0 to 0.032168.

After reconstruction, DataViewer (Kontich, Belgium) was used to select a volume of interest (VOI) that completely encompassed the defect based on visualization of the defect and normalization to the curvature of the skull. The cranial VOI was then analyzed using CTAn (Bruker, Billerica, MA). A binary representation of the bone was then created with a minimum threshold value of 110. Bone volume to total volume (BV/TV) was measured in three-dimensional space to normalize for variations in bone thickness.

After initial analysis using microCT to identify calcified bone healing, skulls were placed in a decalcification solution for 72 hours with gentle agitation. After decalcification, the samples were rinsed thoroughly and placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin until analysis. Decalcified skull samples underwent similar microCT scanning and reconstruction. After reconstruction, samples were evaluated to determine if the MICROFIL perfusion was successful. Complete perfusion of the carotid arteries on both sides of the skull was considered successful. If the carotid arteries were not perfused, the sample was excluded from analysis; 3 mice were excluded for this reason. A binary representation of the VOI was then created with a minimum threshold value of 125 and a maximum value of 210. Percent vascularization, which is a measure of vessel volume divided by total defect volume, vessel separation, which is a measure of the average distance between a vessel and its nearest neighboring vessel, and vessel density, which is a measure of the number of vessels per micron, were then quantified in a three-dimensional space.

Statistical Methods.

Analysis between treatment groups was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s posthoc analysis with SigmaPlot statistical analysis software version 14 (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). All hydrogel property analysis is shown as mean ± SD, while in vivo studies are shown as mean ± SEM. Correlation coefficients between data were determined using a Spearman nonparametric correlation test (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

Aptamer Functionalization Prolongs Release of VEGF without Affecting Native Fibrin Hydrogel Material Properties.

This study used anti-VEGF DNA, an aptamer with a 37-nucleotide sequence (Figure 2b). Due to the small size of the aptamer, the conjugation of this aptamer to fibrinogen did not significantly affect the gelation time of the hydrogel, which is around 40 seconds (Figure 2c). The rheological evaluation showed that native FH and AFH exhibited similar mechanical properties as indicated by loss and storage moduli (Figure 2d). To confirm aptamer functionalization in the AFH, we stained the native FH and AFH with the complementary sequence followed with SYBR Safe. AFH showed strong green fluorescence, whereas native FH did not (Figure 2e). To further demonstrate that aptamer functionalization did not affect the final hydrogel structure, we imaged the lyophilized hydrogels using scanning electron microscopy. Similar interconnected nanofibrillar networks were observed in both FH and AFH (Figure 2e), suggesting that the aptamer did not affect the structure of the final hydrogel.

We next examined short-term VEGF release kinetics from FH and AFH and quantified the effective diffusivity (Figure 3a–c). Aptamer functionalization significantly decreased the effective diffusivity of VEGF from 0.49 ± 0.04 μm2/s to 0.14 ± 0.04 μm2/s (Figure 3b). It is important to note that this calculation may significantly underestimate the aptamer-mediated decrease of diffusivity because the VEGF molecules that are initially released might not be bound to the aptamers during AFH synthesis. Thus, we further examined the long-term release of VEGF from AFH (Figure 3c). At day 1, FH released approximately 68 ± 3% of the total VEGF, whereas AFH released 47 ± 4%. After 4 days, VEGF concentration was undetectable in the FH group, suggesting that all VEGF molecules were released within the first 72–96 h. In contrast, we observed sustained VEGF release from AFH hydrogels over the next 10 days. Taken together, these data demonstrate that the aptamer functionalization prolonged the release of VEGF from the AFH.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of aptamer-functionalized fibrin hydrogel (AFH) and native fibrin hydrogel (FH) VEGF release kinetics. (a) Fractional VEGF release within the first 4 hours. Mt is the VEGF release at time t; Mo is the initially loaded VEGF. Mt/Mo is the fractional release at time t. (b) Effective diffusivity calculated from a (c) daily release of VEGF. n ≥ 3, *** p < 0.05.

Aptamer Functionalization with High Doses of VEGF Improves Angiogenesis Following Cranial Defect.

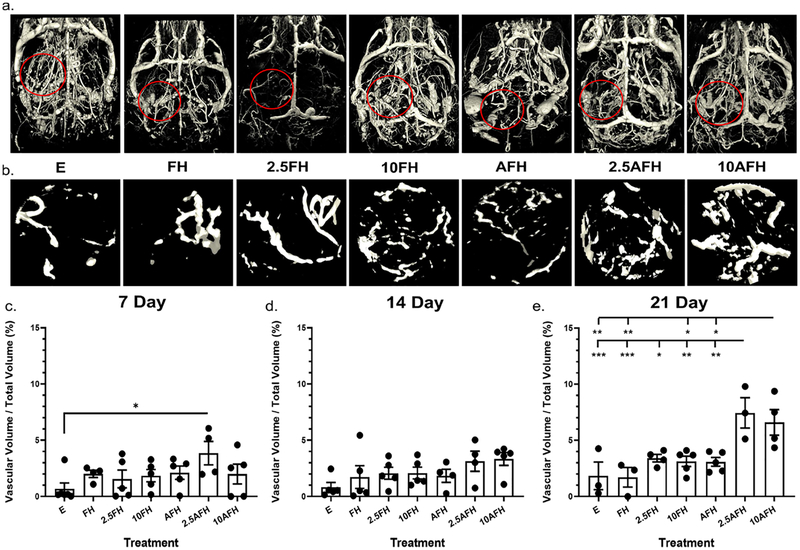

Vascular fraction was quantified as a percentage of total defect volume (Figure 4). Groups, 2.5AFH and 10AFH, showed a significant increase in overall vascularization. At 7 days, the 2.5AFH group had a significant 1.5-fold increase in percent vascularization over the nonhydrogel loaded control (Figure 4c) but did not have a significant increase compared to any other treatment group. At 21 days, 2.5AFH had a significant 2-fold increase compared to all other treatment groups, excluding the 10AFH group (Figure 4e). At this same time point, the 10AFH group showed a significant 2-fold increase compared to all treatment groups evaluated besides the 2.5FH and 2.5AFH groups (Figure 4e). Visual inspection confirmed successful perfusion with MICROFIL for all cranial vasculature based on successful perfusion of the carotid arteries, as well as successful perfusion of the defect site (Figure 4a). Examination of the de novo vascularization within the defect, outlined in red in Figure 4a, with the surrounding vasculature removed, provides a more clear visualization of the variations in angiogenesis caused by each intervention. Removal of the surrounding vasculature reveals the increase in vascular formation in the 2.5AFH and 10AFH groups compared to all other treatment groups (Figure 4b), reaffirming the quantitative measures made previously.

Figure 4.

Total vascularization within the defect volume as a result of hydrogel treatment. (a) A representative image of the total skull vascularization for each intervention 21 days postdefect introduction. (b) Enhanced view of the vascularization within the defect region outlined in red in part a for each intervention 21 days postdefect introduction. MicroCT analysis of the percent vascularization (vascular volume/total defect volume) of the defect at (c) 7 days postdefect introduction for all intervention types, (d) 14 days postdefect introduction for all intervention types, and (e) 21 days postdefect introduction for all intervention types. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.005, *** p < 0.001, n ≥ 3.

Vessel density (vessels/micron) was significantly increased in the 2.5AFH group compared to the E treatment group after 7 days. We also observed an increase in both the 2.5AFH and 10AFH groups over time, reaching statistical significance at day 21 (see Supporting Information Figure S1). 2.5AFH and 10AFH groups showed a 68% and 257%, respectively, increase in vessel density from 7 to 21 days. From day 7 to day 21, an approximately 1-fold increase in vessel density was observed in the E treatment group, while a 20% decrease in density was observed in the FH group. At day 21, both the 2.5AFH and 10AFH groups displayed a 2-fold increase in vessel density relative to both the E and FH groups (see Supporting Information Figure 1c). The treatment groups receiving FH with VEGF at either concentration did not display a significant increase in the number of blood vessels formed compared to any other group evaluated. From day 7 to 21, we observed a 97% and 63% increase in vessel density in the 2.5FH and 10FH groups, respectively. AFH alone only showed a 66% increase in vessel density from day 7 to day 21.

We observed a significant decrease in vessel separation between the 2.5AFH and E treatment groups 7 days postoperatively, with a 2.5-fold reduction in the distance between vessels. An approximately 66% significant decrease in vessel separation was observed, in both the 2.5AFH and the 10AFH groups, compared to the nonhydrogel loaded control, 21 days posthydrogel introduction (see Supporting Information Figure 1f). The average distance between vessels 21 days postoperatively was 217 and 193 μm in the 2.5AFH and 10AFH groups, respectively. The nonhydrogel loaded control defect had an average distance of 645 μm between vessels 21 days after hydrogel introduction, while the FH, 2.5FH, and 10FH with groups had an average distance of 577, 319, and 358 μm between vessels, respectively. The AFH group had an average separation of 350 μm between vessels 21 days after hydrogel introduction, which was not significantly different than the 517 μm separation observed with FH. At no other time point was the separation between the vessels significant for any treatment group (see Supporting Information Figure 1d,e).

Aptamer Functionalization with High Doses of VEGF Improves Osteogenesis Following Cranial Defect.

The nonhydrogel loaded control group showed minimal de novo bone formation in the defect site by day 21 (Figure 5). Seven days posthydrogel introduction, no treatment group, AFH or FH with or without VEGF, was significantly different from the nonhydrogel loaded control defect or any of the other treatments evaluated (Figure 5a). However, at 14 days, the 10AFH group showed significantly greater BV/TV than all other treatment groups, except AFH (Figure 5b). At 21 days postoperatively, BV/TV increased 3.8-fold (from 0.75% to 2.92%) in the 10AFH treatment group compared to the nonhydrogel loaded control group (Figure 5c). Qualitative visualization of bone formation and healing confirms the quantitative analysis, showing a significant decrease in defect size in the 10AFH group 14 days after hydrogel introduction compared to all treatment groups besides AFH. Additionally, there was a slight decrease in defect size in the 10AFH group compared to the FH treatment groups 21 days postoperatively and a significant decrease in defect size compared to E (Figure 5d).

Figure 5.

Analysis of bone healing in critical sized cranial defect. (a) MicroCT analysis of the percent bone volume (bone volume/total defect volume, BV/TV) at 7 days postdefect introduction for all intervention types, (b) 14 days postdefect introduction for all intervention types, and (c) 21 days postdefect introduction for all intervention types. (d) Representative images of each experimental group 21 days postdefect introduction. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.005, n ≥ 3.

4. DISCUSSION

The design and use of novel biomaterials for bone healing applications, especially in large bone defects, is of critical importance due to increasing rates of disease, disuse, and injury.10,29 Hydrogels loaded with growth factors have proven to be effective in treating smaller bone defects, but critical sized bone defects have proven challenging to treat, because of the inadequate release kinetics associated with most hydrogels.23,30 To address this problem, we developed a novel AFH loaded with VEGF, and used it to treat a critical sized cranial defect in mice. Our results show that this novel hydrogel increases the sequestration and retention of VEGF compared to FH. More importantly, this improvement in VEGF kinetics in AFH, relative to FH, was able to promote greater vascularization and osteogenesis in a critically sized calvarial defect, suggesting AFH is a promising avenue for clinical wound healing applications.

The results of this study show that we can successfully increase VEGF incorporation and retention by utilizing an anti-VEGF aptamer while maintaining mechanical and structural properties similar to those of native fibrin hydrogel (Figures 2 and 3). AFH maintained a similar elastic and viscous response as well as similar morphological properties to FH.20 The literature has shown that the physical properties of FH facilitate wound healing. FH alone promotes and aids in cell proliferation, differentiation, and migration, all of which are necessary for healing critical sized defects.19,31 The mechanical properties of FH also allow for the proper stability to support angiogenesis; therefore, maintaining similar physical properties to FH with AFH is highly desirable.32 In addition to maintaining similar physical and mechanical properties to FH, AFH improves the fractional release of VEGF over an initial 4-hour period, diminishes diffusivity, and significantly elongates, compared to FH, measurable VEGF release over 14 days. Our results, corroborated by previous studies with AFH, also show a diminished burst release and an elongated release profile through the use of VEGF-specific aptamers.20,24 The improved release kinetics of AFH and diminished diffusivity also suggest that AFH not only maintains VEGF release over a longer period but also improves VEGF localization and bioavailability at the defect site. Previous studies have shown VEGF is not only important in the promotion of vascularization but also critical in the facilitation of bone formation by recruiting mesenchymal stem cells, activating osteoblast differentiation, and promoting mineralization.33–35 Due to the typical release kinetics exhibited by most hydrogels including FH, VEGF is not localized to the defect long enough to facilitate bone healing, which typically begins 2–3 weeks postinjury.36 Although this issue lacks a complete resolution, even with the use of AFH, the extended diffusivity still has significant implications for bone healing. Previous studies have shown that between 7 and 10 days, the presence of VEGF enhances mesenchymal stem cell recruitment and survival, with VEGF playing a synergistic role with bone morphogenic protein 4 (BMP4), resulting in a significant increase in bone formation after 28 days compared to situations where VEGF was not present.37 This suggests that by using AFH, the extended diffusivity and localization of VEGF will enhance bone formation.

The effects of the improved incorporation and release of VEGF observed in vitro were validated in vivo. An overall increase in vascularization was observed 21 days after hydrogel introduction for AFH compared to all FH treatment groups (Figure 4). Groups receiving AFH loaded with VEGF showed significant changes in vessel separation and vessel density compared to nontreated defects (Figure 3). Similar to previous studies, there was an inverse correlation between the observed increase in vessel density and decrease in vessel separation, validating both measurements, with R-values ranging between −0.6901 and −0.9736 (see Supporting Information Table S1).20 Both vessel density and vessel separation are critical for the successful healing of critical sized bone defects because of the hypoxic environment created in most such bone defects.38 Because of the size of critical defects, diffusion is often the rate-limiting factor. Unless the vessels achieve anastomosis, proper intramembranous ossification and bone remodeling, necessary for a successful repair, are highly unlikely.16,39 This is because the hypoxic environment needs to be relieved for mesenchymal stem cells to infiltrate the defect site and begin the intramembranous ossification process.15,40

Our data also suggest the effect AFH with VEGF has on vascularization may be underestimated. Vessel density and vessel separation (see Supporting Information Figure 1) are measures of only mature vessels or vessels that have undergone anastomosis. Overall vascularization accounts for total vessel volume regardless of maturity and interconnection (Figure 4). The observed changes in overall vascularization were of greater significance than the changes we observed in vessel density and number. This increase in overall vascularization suggests that more vessel anastomosis may occur if this study investigated vascularization at longer time points since some vessels may have yet to reach maturity at the time points currently evaluated. Alternatively, we are aware of the limitations of MICROFIL and its limited perfusion in vessels less than 10 μm in diameter.41 However, this limitation would underestimate the effect of AFH with VEGF has on vasculogenesis, as it may not have allowed quantification of all newly formed vessels that are less than 10 μm in diameter. Thus, this would not change the interpretation of our results.

In vivo evaluation shows a moderate increase in bone healing 14 days postoperatively between the 10AFH treatment group compared to the empty and FH treatment groups. An observable difference was only seen between the 10AFH and empty treatment groups 21 days postoperatively (Figure 5); however, there were no differences observed between the treatment groups at 7 days. Although there was a trend at day 7, suggesting the 10FH and 10AFH groups were inducing greater bone formation, the variance between samples as well as limited sample size did not yield significant differences. The lack of greater significance in bone healing, relative to vascularization, may also be due to the time points evaluated in this study. Because this study aimed to evaluate the properties and release kinetics of AFH and how these may affect vascularization, we evaluated earlier time points than those typically used in bone healing studies.42,43 This prevents bone healing from being characterized fully within the scope of this study, as the bone formation process can take up to 3 months, and vascularization occurs rapidly over the first 3 weeks.38,44 Despite this, information gathered 14 and 21 days postoperatively suggests AFH with VEGF has improved bone formation and healing, a trend that would likely continue at later time points.

Although VEGF is known as an important growth factor in angiogenesis and osteogenesis, intramembranous bone healing is highly complex and utilizes numerous growth factors and chemokines. Because of this, codelivery of multiple factors, such as platelet-derived growth factor and bone morphogenic protein-2 (BMP-2), has been studied extensively using other biomaterial systems with varied success.26,45,46 The specificity of the aptamers used in our AFH system would allow for codelivery of multiple growth factors, allowing for improved healing and a more targeted approach to wound healing. Therefore, AFH is of significant interest for future biomedical applications. The high affinity and specificity of aptamers allow for multiple factors to be investigated simultaneously and various steps in the intramembranous healing process to be promoted. Our AFH system would allow for the development of a proactive and targeted approach for critically sized bone defects.

5. CONCLUSION

This study shows the ability to successfully engineer a functionalized anti-VEGF aptamer into native fibrin and then into AFH. These hydrogels showed no significant changes in structural or mechanical properties compared to FH alone, based on the rheological assessment and nanoscale surface (SEM) evaluation. The AFH showed enhanced retention and release profile of VEGF in vitro, extending the release of VEGF for more than a week longer compared to native FH without aptamer functionalization. Engineered AFH loaded with 10 μg/mL of VEGF enhanced bone formation 14 days postintervention compared to the FH treatment groups and empty controls, but this increase was not observed 21 days postintervention compared to the FH treatment groups. Additionally, the novel hydrogels loaded with VEGF at both concentrations showed a greatly increased ability to induce angiogenesis, increasing vessel density, reducing the separation between blood vessels, and greatly increasing overall vascularization compared to the FH and nonhydrogel loaded defects. The study revealed that AFH, relative to nonfunctionalized FH, has a greater release and retention profile of VEGF, improved bone reparative effects, and induced increased vasculogenesis while maintaining similar structural and mechanical properties to nonfunctionalized FH. This evidence suggests that our AFH could have a considerable clinical application for bone regeneration.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported in part by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (AR073364) and by the Virginia Commonwealth University College of Engineering Foundation Research Endowment.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.9b01175.

Figure S1, angiogenic evaluation of vessel density and spacing as a result of various hydrogel treatment groups examined; Figure S2, microCT images of both calcified and decalcified VOIs from all treatment groups at 7, 14, and 21 days postoperatively; and Table S1, correlation evaluation of vessel separation and vessel density (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Flierl MA; Smith WR; Mauffrey C; Irgit K; Williams AE; Ross E; Peacher G; Hak DJ; Stahel PF Outcomes and Complication Rates of Different Bone Grafting Modalities in Long Bone Fracture Nonunions: A Retrospective Cohort Study in 182 Patients. J. Orthop. Surg. Res 2013, 8, 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Winkler T; Sass FA; Duda GN; Schmidt-Bleek K A Review of Biomaterials in Bone Defect Healing, Remaining Shortcomings and Future Opportunities for Bone Tissue Engineering: The Unsolved Challenge. Bone Joint Res 2018, 7 (3), 232–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Dimitriou R; Jones E; McGonagle D; Giannoudis PV Bone Regeneration: Current Concepts and Future Directions. BMC Med 2011, 9 (1), 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Townsend CM; Beauchamp RD; Evers BM; Mattox KL Sabiston Textbook of Surgery; Elsevier: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Sterling JA; Guelcher SA Biomaterial Scaffolds for Treating Osteoporotic Bone. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep 2014, 12 (1), 48–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Bisicchia S; Tudisco C Radial Head and Neck Allograft for Comminute Irreparable Fracture-Dislocations of the Elbow. Orthopedics 2016, 39 (6), e1205–e1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Moghaddam A; Ermisch C; Schmidmaier G Non-Union Current Treatment Concept. Shafa Ortho J 2016, 3 (1), e4546. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Amini AR; Laurencin CT; Nukavarapu SP Bone Tissue Engineering: Recent Advances and Challenges. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng 2012, 40 (5), 363–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Bohner M Resorbable Biomaterials as Bone Graft Substitutes. Mater. Today 2010, 13 (1), 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- (10).O’Brien FJ Biomaterials & Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering. Mater. Today 2011, 14 (3), 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Orth M; Shenar AK; Scheuer C; Braun BJ; Herath SC; Holstein JH; Histing T; Yu X; Murphy WL; Pohlemann T; Laschke MW; Menger MD VEGF-loaded Mineral-coated Microparticles Improve Bone Repair and Are Associated with Increased Expression of Epo and RUNX-2 in Murine Non-unions. J. Orthop. Res 2019, 37 (4), 821–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Otterbein LE; Fan Z; Koulmanda M; Thronley T; Strom TB Innate Immunity for Better or Worse Govern the Allograft Response. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant 2015, 20 (1), 8–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lichte P; Pape HC; Pufe T; Kobbe P; Fischer H Scaffolds for Bone Healing: Concepts, Materials and Evidence. Injury 2011, 42 (6), 569–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Oryan A; Alidadi S; Moshiri A; Maffulli N Bone Regenerative Medicine: Classic Options, Novel Strategies, and Future Directions. J. Orthop. Surg. Res 2014, 9 (1), 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).García JR; García AJ Biomaterial-Mediated Strategies Targeting Vascularization for Bone Repair. Drug Delivery Transl. Res 2016, 6 (2), 77–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Hankenson KD; Dishowitz M; Gray C; Schenker M Angiogenesis in Bone Regeneration. Injury 2011, 42 (6), 556–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Chen N; Zhang Z; Soontornworajit B; Zhou J; Wang Y Cell Adhesion on an Artificial Extracellular Matrix Using Aptamer-Functionalized PEG Hydrogels. Biomaterials 2012, 33 (5), 1353–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Maisani M; Pezzoli D; Chassande O; Mantovani D Cellularizing Hydrogel-Based Scaffolds to Repair Bone Tissue: How to Create a Physiologically Relevant Micro-Environment? J. Tissue Eng 2017, 8, 2041731417712073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Janmey PA; Winer JP; Weisel JW Fibrin Gels and Their Clinical and Bioengineering Applications. J. R. Soc., Interface 2009, 6 (30), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Zhao N; Coyne J; Xu M; Zhang X; Suzuki A; Shi P; Lai J; Fong G-H; Xiong N; Wang Y Assembly of Bifunctional Aptamer-Fibrinogen Macromer for VEGF Delivery and Skin Wound Healing. Chem. Mater 2019, 31, 1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Linnes MP; Ratner BD; Giachelli CM A Fibrinogen-Based Precision Microporous Scaffold for Tissue Engineering. Biomaterials 2007, 28 (35), 5298–5306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Li Y; Meng H; Liu Y; Lee BP Fibrin Gel as an Injectable Biodegradable Scaffold and Cell Carrier for Tissue Engineering. Sci. World J 2015, 2015, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Hoare TR; Kohane DS Hydrogels in Drug Delivery: Progress and Challenges. Polymer 2008, 49 (8), 1993–2007. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Battig MR; Huang Y; Chen N; Wang Y Aptamer-Functionalized Superporous Hydrogels for Sequestration and Release of Growth Factors Regulated via Molecular Recognition. Biomaterials 2014, 35 (27), 8040–8048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Street J; Bao M; deGuzman L; Bunting S; Peale FV Jr.; Ferrara N; Steinmetz H; Hoeffel J; Cleland JL; Daugherty A; van Bruggen N; Redmond HP; Carano RA; Filvaroff EH Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Stimulates Bone Repair by Promoting Angiogenesis and Bone Turnover. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2002, 99 (15), 9656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Young S; Patel ZS; Kretlow JD; Murphy MB; Mountziaris PM; Baggett LS; Ueda H; Tabata Y; Jansen JA; Wong M; Mikos AG Dose Effect of Dual Delivery of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 on Bone Regeneration in a Rat Critical-Size Defect Model. Tissue Eng., Part A 2009, 15 (9), 2347–2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Ritger PL; Peppas NA A Simple Equation for Description of Solute Release II. Fickian and Anomalous Release from Swellable Devices. J. Controlled Release 1987, 5 (1), 37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Hyzy SL; Kajan I; Wilson DS; Lawrence KA; Mason D; Williams JK; Olivares-Navarrete R; Cohen DJ; Schwartz Z; Boyan BD Inhibition of Angiogenesis Impairs Bone Healing in an in vivo Murine Rapid Resynostosis Model. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A 2017, 105 (10), 2742–2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Gordeladze JO; Haugen HJ; Lyngstadaas SP; Reseland JE Bone Tissue Engineering: State of the Art, Challenges, and Prospects In Tissue Engineering for Artificial Organs; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2017; pp 525–551, ISBN: 978-3-527-33863-4. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Drury JL; Mooney DJ Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering: Scaffold Design Variables and Applications. Biomaterials 2003, 24(24), 4337–4351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Caliari SR; Burdick JA A Practical Guide to Hydrogels for Cell Culture. Nat. Methods 2016, 13 (5), 405–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Claes L; Eckert-Hübner K; Augat P The Effect of Mechanical Stability on Local Vascularization and Tissue Differentiation in Callus Healing. J. Orthop. Res 2002, 20 (5), 1099–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Maes C; Carmeliet G Vascular and Nonvascular Roles of VEGF in Bone Development. In VEGF in Development; 2013; DOI: 10.1007/978-0-387-78632-2_7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Ogilvie CM; Lu C; Marcucio R; Lee M; Thompson Z; Hu D; Helms JA; Miclau T Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Improves Bone Repair in a Murine Nonunion Model. Iowa Orthop. J 2012, 32, 90–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Hu K; Olsen BR The Roles of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in Bone Repair and Regeneration. Bone 2016, 91, 30–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Klein M; Stieger A; Stenger D; Scheuer C; Holstein JH; Pohlemann T; Menger MD; Histing T Comparison of Healing Process in Open Osteotomy Model and Open Fracture Model: Delayed Healing of Osteotomies after Intramedullary Screw Fixation.J. Orthop. Res 2015, 33 (7), 971–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Peng H; Wright V; Usas A; Gearhart B; Shen H-C; Cummins J; Huard J Synergistic Enhancement of Bone Formation and Healing by Stem Cell-Expressed VEGF and Bone Morphogenetic Protein-4. J. Clin. Invest 2002, 110 (6), 751–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Novosel EC; Kleinhans C; Kluger PJ Vascularization Is the Key Challenge in Tissue Engineering. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev 2011, 63 (4–5), 300–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Tomlinson RE; Silva MJ Skeletal Blood Flow in Bone Repair and Maintenance. Bone Res 2013, 1 (4), 311–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Hu K; Olsen BR The Roles of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in Bone Repair and Regeneration. Bone 2016, 91, 30–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Wang H-K; Wang Y-X; Xue C-B; Li Z-M-Y; Huang J; Zhao Y-H; Yang Y-M; Gu X-S Angiogenesis in Tissue-Engineered Nerves Evaluated Objectively Using MICROFIL Perfusion and Micro-CT Scanning. Neural Regener. Res 2016, 11 (1), 168–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Lim JY; Loiselle AE; Lee JS; Zhang Y; Salvi JD; Donahue HJ Optimizing the Osteogenic Potential of Adult Stem Cells for Skeletal Regeneration. J. Orthop. Res 2011, 29, 1627–1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Lybrand K; Bragdon B; Gerstenfeld L Mouse Models of Bone Healing: Fracture, Marrow Ablation, and Distraction Osteogenesis. Curr. Protoc. Mouse Biol 2015, 5 (1), 35–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Hsiong SX; Mooney DJ Regeneration of Vascularized Bone. Periodontol 2000. 2006, 41 (1), 109–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).De Witte T-M; Fratila-Apachitei LE; Zadpoor AA; Peppas NA Bone Tissue Engineering via Growth Factor Delivery: From Scaffolds to Complex Matrices. Regen. Biomater 2018, 5 (4), 197–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Devescovi V; Leonardi E; Ciapetti G; Cenni E Growth Factors in Bone Repair. Chir. Organi Mov 2008, 92 (3), 161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.