Abstract

Background

Early and accurate diagnosis and treatment of schizophrenia may have long‐term advantages for the patient; the longer psychosis goes untreated the more severe the repercussions for relapse and recovery. If the correct diagnosis is not schizophrenia, but another psychotic disorder with some symptoms similar to schizophrenia, appropriate treatment might be delayed, with possible severe repercussions for the person involved and their family. There is widespread uncertainty about the diagnostic accuracy of First Rank Symptoms (FRS); we examined whether they are a useful diagnostic tool to differentiate schizophrenia from other psychotic disorders.

Objectives

To determine the diagnostic accuracy of one or multiple FRS for diagnosing schizophrenia, verified by clinical history and examination by a qualified professional (e.g. psychiatrists, nurses, social workers), with or without the use of operational criteria and checklists, in people thought to have non‐organic psychotic symptoms.

Search methods

We conducted searches in MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycInfo using OvidSP in April, June, July 2011 and December 2012. We also searched MEDION in December 2013.

Selection criteria

We selected studies that consecutively enrolled or randomly selected adults and adolescents with symptoms of psychosis, and assessed the diagnostic accuracy of FRS for schizophrenia compared to history and clinical examination performed by a qualified professional, which may or may not involve the use of symptom checklists or based on operational criteria such as ICD and DSM.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened all references for inclusion. Risk of bias in included studies were assessed using the QUADAS‐2 instrument. We recorded the number of true positives (TP), true negatives (TN), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN) for constructing a 2 x 2 table for each study or derived 2 x 2 data from reported summary statistics such as sensitivity, specificity, and/or likelihood ratios.

Main results

We included 21 studies with a total of 6253 participants (5515 were included in the analysis). Studies were conducted from 1974 to 2011, with 80% of the studies conducted in the 1970's, 1980's or 1990's. Most studies did not report study methods sufficiently and many had high applicability concerns. In 20 studies, FRS differentiated schizophrenia from all other diagnoses with a sensitivity of 57% (50.4% to 63.3%), and a specificity of 81.4% (74% to 87.1%) In seven studies, FRS differentiated schizophrenia from non‐psychotic mental health disorders with a sensitivity of 61.8% (51.7% to 71%) and a specificity of 94.1% (88% to 97.2%). In sixteen studies, FRS differentiated schizophrenia from other types of psychosis with a sensitivity of 58% (50.3% to 65.3%) and a specificity of 74.7% (65.2% to 82.3%).

Authors' conclusions

The synthesis of old studies of limited quality in this review indicates that FRS correctly identifies people with schizophrenia 75% to 95% of the time. The use of FRS to diagnose schizophrenia in triage will incorrectly diagnose around five to 19 people in every 100 who have FRS as having schizophrenia and specialists will not agree with this diagnosis. These people will still merit specialist assessment and help due to the severity of disturbance in their behaviour and mental state. Again, with a sensitivity of FRS of 60%, reliance on FRS to diagnose schizophrenia in triage will not correctly diagnose around 40% of people that specialists will consider to have schizophrenia. Some of these people may experience a delay in getting appropriate treatment. Others, whom specialists will consider to have schizophrenia, could be prematurely discharged from care, if triage relies on the presence of FRS to diagnose schizophrenia. Empathetic, considerate use of FRS as a diagnostic aid ‐ with known limitations ‐ should avoid a good proportion of these errors.

We hope that newer tests ‐ to be included in future Cochrane reviews ‐ will show better results. However, symptoms of first rank can still be helpful where newer tests are not available ‐ a situation which applies to the initial screening of most people with suspected schizophrenia. FRS remain a simple, quick and useful clinical indicator for an illness of enormous clinical variability.

Plain language summary

First rank symptoms for schizophrenia

It is important for patients with psychosis to be correctly diagnosed as soon as possible. The earlier schizophrenia is diagnosed the better the treatment outcome. However, other diseases sometimes have similar psychotic symptoms as schizophrenia, for example bipolar disorder. This review looks at how accurate First Rank Symptoms (FRS) are at diagnosing schizophrenia. FRS are symptoms that people with psychosis may experience, for example hallucinations, hearing voices and thinking that other people can hear their thoughts. We found 21 studies, with 6253 participants, that looked at how good FRS are at diagnosing schizophrenia when compared to a diagnosis made by a psychiatrist. These studies showed that for people who actually have schizophrenia, FRS would only correctly diagnose just over half of them as schizophrenic. For people who do not have schizophrenia, almost 20% would be incorrectly diagnosed with schizophrenia. Therefore, if a person is experiencing a FRS, schizophrenia is a possible diagnosis, but there is also a chance that it is another mental health disorder. We do not recommend that FRS alone can be used to diagnose schizophrenia. However, FRS could be useful to triage patients who need to be assessed by a psychiatrist.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings'. 'Summary of findings table.

| What is the diagnostic accuracy of first rank symptoms for schizophrenia? | |||||

| Patients/population | People with psychotic symptoms and admissions to psychiatric ward | ||||

| Prior testing | Most studies did not only include patients with first episode psychosis, so it is likely that patients had experienced prior testing | ||||

| Settings | Mostly inpatient setting | ||||

| Index test | Presence of at least one FRS or number of FRSs was not reported | ||||

| Importance | FRS could be used to screen out the seriously mentally ill for further consideration by more specialised services | ||||

| Reference standard | There is no gold standard for diagnosing schizophrenia. Reference standard used: history and clinical examination collected by a qualified professional, which may or may not involve the use of operational criteria or checklists of symptoms | ||||

| Studies | Prospective and retrospective studies including people with psychosis or admissions to psychiatric ward were used (n = 21) | ||||

| Test / subgroup | Summary accuracy % (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Prevalence median (range) | Implications | Quality and comments |

| Diagnosis of schizophrenia from all other diagnoses | Sensitivity 57.0 (50.4, 63.3) Specificity 81.4 (74.0, 87.1) | 5079 (20) | 48% (15% to 84%) | With a prevalence of 48%, 48 out of every 100 patients will have schizophrenia. Of these, 21 will be missed by FRS (43% of 48). Of the 52 patients without schizophrenia, 10 may be incorrectly diagnosed with schizophrenia. | Important issues regarding patient selection, use of index test and reference standard were not clearly reported, leading to uncertainty in the results. Most studies were conducted in a research setting, rather than a clinical setting. |

| Diagnosis of schizophrenia from other types of psychosis | Sensitivity 58.0 (50.3, 65.3) Specificity 74.7 (85.2, 82.3) | 4070 (16) | 57% (24% to 84%) | With a prevalence of 57%, 57 out of every 100 patients will have schizophrenia. Of these, 24 will be missed by FRS (42% of 57). Of the 43 patients without schizophrenia, 13 may be incorrectly diagnosed with schizophrenia. | Important issues regarding patient selection, use of index test and reference standard were not clearly reported, leading to uncertainty in the results. Most studies were conducted in a research setting, rather than a clinical setting. |

| Diagnosis of schizophrenia from non‐psychotic disorders | Sensitivity 61.8 (51.7, 71.0) Specificity 94.1 (88.0, 97.2) | 1652 (7) | 55% (19% to 89%) | With a prevalence of 55%, 55 out of every 100 patients will have schizophrenia. Of these, 21 will be missed by FRS (38% of 55). Of the 45 patients without schizophrenia, 3 may be incorrectly diagnosed with schizophrenia. | Important issues regarding patient selection, use of index test and reference standard were not clearly reported, leading to uncertainty in the results. Most studies were conducted in a research setting, rather than a clinical setting. |

| CAUTION: The results on this table should not be interpreted in isolation from the results of the individual included studies contributing to each summary test accuracy measure. These are reported in the main body of the text of the review. | |||||

FRS: first rank symptoms

Background

Target condition being diagnosed

Schizophrenia is a psychotic disorder that can occur as a single episode of illness, although the majority of sufferers have remissions and relapses, and for many sufferers the condition becomes chronic and disabling (Bustillo 2001). The most effective method of treatment is antipsychotic medication. These medications produce various side effects (Kane 2001) so low doses, used in as timely a fashion as possible, are indicated. There is some evidence to suggest that early intervention for people with schizophrenia can be beneficial, helping avoid or postpone damaging relapses and the need for prolonged use of medications (Marshall 2011). Early and accurate diagnostic techniques would have particular utility (Marshall 2011).

Index test(s)

The index test being evaluated in this review are Schneider’s First Rank Symptoms (FRS), which include: auditory hallucinations; thought withdrawal, insertion and interruption; thought broadcasting; somatic hallucinations; delusional perception; feelings or actions as made or influenced by external agents (Schneider 1959, Table 2). These are the so‐called positive symptoms, i.e. they are symptoms not usually experienced by people without schizophrenia, and are usually given priority among other positive symptoms. Negative symptoms are deficits of emotional responses or other thought processes. These positive symptoms of first rank are currently incorporated into the major operationalised diagnostic systems of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases‐10 (ICD‐10) (Table 3) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder‐III‐IV (DSM‐III‐IV) (Table 4). These systems, however, go beyond the relatively simple list produced by Schneider.

1. Schneider First Rank Symptoms.

| First rank symptom | Definition | Example |

| Auditory hallucinations | Auditory perceptions with no cause. These auditory hallucinations have to be of particular types: |

|

| hearing thoughts spoken aloud | "I hear my thoughts outside my head." | |

| hearing voices referring to himself/herself made in the third person | "The first voice says 'He used that fork in an odd way' and then the second replies 'Yes, he did'". | |

| auditory hallucinations in the form of a commentary | "They say 'He is sitting down now talking to the psychiatrist'". | |

| Thought withdrawal, insertion and interruption | A person's thoughts are under control of an outside agency and can be removed, inserted (and felt to be alien to him/her) or interrupted by others. | "My thoughts are fine except when Michael Jackson stops them." |

| Thought broadcasting | As the person is thinking everyone is thinking in unison with him/her. | "My thoughts filter out of my head and everyone can pick them up if they walk past." |

| Somatic hallucinations | A hallucination involving the perception of a physical experience with the body | "I feel them crawling over me." |

| Delusional perception | A true perception, to which a person attributes a false meaning. | A perfectly normal event such as the traffic lights turning red may be interpreted by the patient as meaning that Martians are about to land. |

| Feelings or actions experienced as made or influenced by external agents | Where there is certainty that an action of the person or a feeling is caused not by themselves but by some others or other force. | "The CIA controlled my arm." |

2. ICD‐10 criteria for schizophrenia.

| Although no strictly pathognomonic symptoms can be identified, for practical purposes it is useful to divide symptoms into groups that have special importance for the diagnosis and often occur together, such as: |

| a) thought echo, thought insertion or withdrawal, and thought broadcasting; |

| b) delusions of control, influence, or passivity, clearly referred to body or limb movements or specific thoughts, actions, or sensations; delusional perception; |

| c) hallucinatory voices giving a running commentary on the patient's behaviour, or discussing the patient among themselves, or other types of hallucinatory voices coming from some part of the body; |

| d) persistent delusions of other kinds that are culturally inappropriate and completely impossible, such as religious or political identity, or superhuman powers and abilities (e.g. being able to control the weather, or being in communication with aliens from another world); |

| e) persistent hallucinations in any modality, when accompanied either by fleeting or half‐formed delusions without clear affective content, or by persistent over‐valued ideas, or when occurring every day for weeks or months on end; |

| f) breaks or interpolations in the train of thought, resulting in incoherence or irrelevant speech, or neologisms; |

| g) catatonic behaviour, such as excitement, posturing, or waxy flexibility, negativism, mutism, and stupor; |

| h) "negative" symptoms such as marked apathy, paucity of speech, and blunting or incongruity of emotional responses, usually resulting in social withdrawal and lowering of social performance; it must be clear that these are not due to depression or to neuroleptic medication; |

| i) a significant and consistent change in the overall quality of some aspects of personal behaviour, manifest as loss of interest, aimlessness, idleness, a self‐absorbed attitude, and social withdrawal. |

| The normal requirement for a diagnosis of schizophrenia is that a minimum of one very clear symptom (and usually two or more if less clear‐cut) belonging to any one of the groups listed as (a) to (d) above, or symptoms from at least two of the groups referred to as (e) to (h), should have been clearly present for most of the time during a period of 1 month or more. Conditions meeting such symptomatic requirements but of duration less than 1 month (whether treated or not) should be diagnosed in the first instance as acute schizophrenia‐like psychotic disorder and are classified as schizophrenia if the symptoms persist for longer periods. |

ICD: International Statistical Classification of Diseases

3. DSM‐IV criteria for schizophrenia.

| A* |

Characteristic symptoms: Two or more of the following, each present for a significant portion of time during a one‐month period:

|

| B | Social/occupational dysfunction: Since the onset of the disturbance, one or more major areas of functioning, such as work, interpersonal relations, or self‐care, are markedly below the level previously achieved. |

| C | Duration: Continuous signs of the disturbance persist for at least six months. This six‐month period must include at least one month of symptoms (or less if successfully treated) that meet Criterion A. |

| D | Exclusion of schizoaffective disorder and mood disorder with psychotic features. |

| E | Substance/general medical condition exclusion: the disturbance is not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g. a drug of abuse, a medication) or a general medical condition. |

| F | Relationship to a pervasive developmental disorder: If there is a history of autistic disorder or another pervasive development disorder, the diagnosis of schizophrenia is made only if prominent delusions or hallucinations are also present for at least a month (or less if successfully treated). |

| * Only one Criterion A symptom is required if delusions are bizarre or hallucinations consist of a voice keeping up a running commentary on the person's behaviour or thoughts, or two or more voices conversing with each other. | |

DSM: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder

The presence of even one of these first rank symptoms is said to be strongly suggestive of schizophrenia (Schneider 1959) and it is postulated that this may be symptomatically sufficient for a diagnosis of schizophrenia. As such, these signs or symptoms are often not difficult to illicit by healthcare professionals with some minimal training. They are low technology and, potentially, high utility. If of diagnostic value, they could be employed world‐wide.

We examined whether the presence of any one FRS or multiple FRSs, are a useful diagnostic tool to differentiate schizophrenia from other psychotic disorders. FRS, however, have been described in subsequent studies in people with other psychiatric diagnoses such as mood disorders with psychotic symptoms, thus raising doubts about their specificity for schizophrenia (Koehler 1978; Koehler 1979).

Clinical pathway

For someone with psychotic symptoms, if it is the first time they have experienced delusions or hallucinations, they would be considered to have 'first episode psychosis'. People typically present to primary care or emergency services from where they are referred to specialists ‐ Early Intervention Teams in the UK and similar secondary care services elsewhere. A specific diagnosis of 'schizophrenia' is made only after several months of longitudinal observation using widely accepted nosological criteria (ICD or DSM). Once someone has received such a diagnosis this has major treatment, psychological and social implications. People may be treated with antipsychotic medications, which carry risk of serious adverse effects, may be treated for long periods, and a person's life course may alter. A diagnosis of schizophrenia is thought to be useful ‐ swiftly communicating much information about the person's condition ‐ but it carries with it a stigma. Accurate diagnosis is important.

The onset of schizophrenia is usually in adolescence or early adulthood and around seven people out of 1000 will be affected during their lifetime (McGrath 2008); the lifetime prevalence of the illness is around 0.5% to 1%. Confirmation of diagnosis is largely determined by symptom stability (of psychosis and of FRS) and, at least in a majority of cases, a deteriorating course (i.e. not reaching pre‐morbid levels of functioning). Five subtypes of schizophrenia have been described: paranoid, disorganised, catatonic, undifferentiated and residual type but none are clearly discrete nor allow confident prediction of the long‐term course of the disease. However, insidious slow onset of illness lasting for several months is associated with a poor prognosis when compared with acute onset linked to stress and lasting only a few weeks (Lawrie 2004). Within five years of the initial episode the clinical pathway tends to be clear. Around 20% of those with clear symptoms of schizophrenia at initial diagnosis recover and do not have relapses. Another 20% have a chronic and unremitting course. The remainder have a relapsing illness the pattern of which tends to be set within the first five years of illness, with reasonable recovery in between. Approximately five per cent of patients will end their own lives ‐ often early in the illness (Hor 2010).

Prior test(s)

It is unlikely that an individual would have had any other test before being examined using FRS.

Role of index test(s)

Schneider's efforts helped make diagnoses more operational, although use of the checklist was never free of criticism because of concerns regarding false positive diagnoses (Koehler 1978) and, therefore, potentially damaging miss‐labelling (Koehler 1979). Although the ICD and DSM operational criteria have superseded Schneider's list in many areas, the simple Schneider checklist needs more careful consideration of patient history to apply, and it is therefore of value. Furthermore, the Schneiderian list still forms a core of psychopathological training worldwide. This is particularly true in regions where health care workers are not highly trained and where access to specialists is limited. In these situations, FRS can certainly be used to triage the seriously mentally ill for further consideration by more specialised services.

Alternative test(s)

Alternative tests for schizophrenia include operational criteria: the International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD‐9 or ICD‐10) (Table 3); Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM‐III or DSM‐IV) (Table 4); Feighner (Feighner 1972); Research Diagnostic Criteria (Spitzer 1978); Carpenter criteria (Carpenter 1973); New Haven (Astrachan 1974); Taylor Abrams (Taylor 1978); Bleulerian (Bleuler 1950) and/or ego function (Bellak 1973).

Largely, these operational criteria have superseded Schneider's list and confirm diagnosis of schizophrenia by determining symptom stability (of psychosis and of FRS) and (at least in a majority) a deteriorating course (not reaching pre‐morbid levels of functioning). These operational criteria that incorporate FRS whilst confirming longitudinally are also likely to be the current reference standard. The new DSM‐5, however, is moving away from special treatment of Schneiderian first rank symptoms (Tandon 2013) to very diagnostic stipulations, "raising the symptom threshold" and necessitating considerably more skill to elicit than the relatively simple FRS.

Rationale

Early and accurate diagnosis and treatment of schizophrenia may have long‐term advantages for the patient (De Haan 2003); there is also evidence that the longer psychosis goes unnoticed and untreated the more severe the repercussions for relapse and recovery (Bottlender 2003). If schizophrenia is not really the diagnosis, embarking on a schizophrenia treatment path could be very deleterious, due to the stigma associated with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and having intrusive treatment with considerable physical, social and psychological adverse effects. Furthermore, if the correct diagnosis is another psychotic disorder with some symptoms similar to schizophrenia ‐ the most likely being bipolar disorder – treatment tailored to schizophrenia may cause symptoms to be ignored and appropriate treatment delayed, with possible severe repercussions for the person involved and their family.

There is widespread uncertainty about the diagnostic specificity and sensitivity of the ubiquitous FRS; therefore, we determined to examine whether they are a useful diagnostic tool to help triage which patients need to be assessed by a qualified professional. This would be particularly relevant in settings where healthcare workers are not highly trained and where access to specialists is limited.

This review is part of a series of Cochrane reviews using the same methodology to assess the diagnostic accuracy of tests for schizophrenia, such as the Operational Criteria Checklist for Psychotic Illness and Affective Illness (OPCRIT+) (Bergman 2014) and the brain imaging analysis technique voxel‐based morphometry (Palaniyappan 2014).

Objectives

To determine the diagnostic accuracy of one or multiple FRS for diagnosing schizophrenia, verified by clinical history and examination by a qualified professional (e.g. psychiatrists, nurses, social workers), with or without the use of operational criteria and checklists, in people thought to have non‐organic psychotic symptoms.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included both retrospective and prospective studies, which consecutively or randomly selected participants. We excluded case‐control studies that used healthy controls.

Studies were included that evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of First Rank Symptoms (one or multiple) for diagnosis of schizophrenia compared with a reference standard, irrespective of publication status and language.

Participants

We included adolescents and adults presenting with psychotic symptoms, which included symptoms such as, hallucinations, delusions, disordered thinking and speech, grossly disorganised or catatonic behaviour, or negative symptoms (i.e. affective flattening, alogia, or volition). We did not exclude on the grounds of co‐morbidities. In addition, if a study reported all admissions to a psychiatric ward instead of only people admitted with psychosis, the study, including those participants with non‐psychotic symptoms, was not excluded. We did exclude if participants had organic source of psychosis, such as that triggered by an existent physical disease or alcohol and drug abuse.

Particular attention was paid to history, current clinical state (acute, post‐acute or quiescent), stage of illness (prodromal, early, established, late), or if there were predominant clinical issues (negative or positive symptoms). In addition, setting and referral status of people in the study was noted. We recognise that people in psychiatric hospital have already experienced a considerable degree of prior testing compared with those in community settings. Also, for similar reasons, people referred to a specialist centre treating only those with schizophrenia may well be different to those in general care.

Index tests

Schneider First Rank Symptoms (Table 2). The presence of any one of these symptoms, or multiple symptoms, would be indicative of a diagnosis of schizophrenia. We consider this an acceptable variation in threshold as Kurt Schneider proposed that presence of any one of these symptoms was diagnostic of schizophrenia as long as the person was free of other organic causes such as substance misuse, epilepsy or tumours (Schneider 1959). The different value of one symptom over another is not the focus of this review.

Target conditions

All types of schizophrenia disorder regardless of descriptive subcategory (e.g. paranoid, disorganised, catatonic, undifferentiated and residual). Studies that reported results combined for diagnoses related to schizophrenia (e.g. schizoaffective and schizophreniform disorder) in which data could not be separated were included and we investigated potential heterogeneity.

Reference standards

The reference standard is history and clinical examination collected by a qualified professional (e.g., psychiatrists, nurses, social workers), which may or may not involve the use of operational criteria or checklists of symptoms such as:

International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD‐9 or ICD‐10) (Table 3);

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM‐III or DSM‐IV) (Table 4);

Feighner (Feighner 1972);

Research Diagnostic Criteria (Spitzer 1978);

Carpenter criteria (Carpenter 1973);

New Haven (Astrachan 1974);

Taylor Abrams (Taylor 1978);

Bleulerian (Bleuler 1950) and/or ego function (Bellak 1973).

The more modern of these criteria involve some degree of follow‐up.

Ideally, in order to avoid incorporation bias the reference standard and the diagnostic test under consideration should be entirely independent of one another (Worster 2008). We were not be able to avoid incorporation bias with this review, as in most cases the reference standard incorporated FRS and hence the diagnostic accuracy may potentially be overestimated (Worster 2008). Also, in many cases using FRS also included taking a history and clinical examination, again contaminating the uniqueness of either approach. Differences between FRS and the reference standard lies in utilisation of:

a longitudinal frame work in addition to the cross sectional assessment of specific symptoms of psychosis such as FRS (reflecting limbic system abnormalities); and

less specific symptoms of psychosis such as the consequences of having acute psychotic symptoms and the deleterious effects of psychosis.

Heterogeneity due to whether FRSs or any operational criteria were used as part of the reference standard was investigated.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We conducted searches in MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycInfo using OvidSP (see Table 5 for full details of the peer‐reviewed search strategies) in April, June, July 2011 and December 2012. We also searched MEDION in December 2013. At the time of writing the protocol for this review there was no verified method of developing search strategies for DTA reviews. We decided to carry out our searches in phases while developing the search strategies with guidance from the Cochrane DTA Group. As there was a time lag between the phases and we did not want to miss any potentially relevant references, we did not apply any time limitation for the later phases. For the later phases of each database search, de‐duplication was carried out against the previous search phases before screening commenced.

4. Search strategies.

| Database | Phase and date | Search strategy |

| MEDLINE (OvidSP) | Phase I Date: 13‐04‐11 |

1 first‐rank.mp. 2 first rank.mp. 3 first?rank.mp. 4 FRS$.mp. 5 Schneiderian.mp 6 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 (2137) |

| Phase II Date: 01‐06‐11 |

1 exp "International Classification of Diseases"/ (3305) 2 exp "Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders"/ (9349) 3 "Research Diagnostic Criteria".mp. (1325) 4 Feighner.mp. (147) 5 ICD.mp. (13774) 6 DSM.mp. (29660) 7 RDC.mp. (1143) 8 schneider.mp. (1529) 9 bleuler.mp. (215) 10 kraepelin.mp. (495) 11 "international pilot study of schizophrenia".mp. (47) 12 IPSS.mp. (1436) 13 "new haven schizophrenia index".mp. (13) 14 NHSI.mp. (14) 15 "present state examination".mp. (412) 16 PSE.mp. (1394) 17 "operational criteria".mp. (431) 18 (operation$ adj3 criteri$).mp. [mp=protocol supplementary concept, rare disease supplementary concept, title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word, unique identifier] (1077) 19 "Sensitivity and Specificity"/ (233760) 20 Diagnosis/ (15703) 21 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 (303793) 22 exp Schizophrenia/ (74720) 23 schizophren$.mp. (93319) 24 22 or 23 (93528) 25 21 and 24 (7401) 26 (animals not (humans and animals)).sh. (3503422) 27 25 not 26 (7398) |

|

| Phase III Date: 17‐07‐11 |

1 *schizophrenia/di [Diagnosis] (16918) | |

| EMBASE (OvidSP) | Phase I Date: 13‐04‐11 |

1 first‐rank.mp. 2 first rank.mp. 3 first?rank.mp. 4 FRS$.mp. 5 Schneiderian.mp 6 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 (456) |

| Phase II Date: 01‐06‐11 |

1 exp "International Classification of Diseases"/ (5070) 2 exp "Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders"/ (17196) 3 "Research Diagnostic Criteria".mp. (1436) 4 Feighner.mp. (161) 5 ICD.mp. (20919) 6 DSM.mp. (38725) 7 RDC.mp. (1310) 8 schneider.mp. (2302) 9 bleuler.mp. (293) 10 kraepelin.mp. (661) 11 "international pilot study of schizophrenia".mp. (40) 12 IPSS.mp. (2881) 13 "new haven schizophrenia index".mp. (12) 14 NHSI.mp. (22) 15 "present state examination".mp. (447) 16 PSE.mp. (1625) 17 "operational criteria".mp. (557) 18 (operation$ adj3 criteri$).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword] (1358) 19 "Sensitivity and Specificity"/ (139513) 20 Diagnosis/ (544275) 21 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 (755543) 22 exp Schizophrenia/ (110049) 23 schizophren$.mp. (120515) 24 22 or 23 (121863) 25 21 and 24 (12378) 26 Human/ (12332237) 27 nonhuman/ (3642333) 28 26 and 27 (656673) 29 27 not 28 (2985660) 30 25 not 29 (12368) |

|

| Phase III Date: 17‐07‐11 |

1 *schizophrenia/di [Diagnosis] (12453) | |

| PsycINFO (OvidSP) | Phase I Date: 13‐04‐11 |

1 first‐rank.mp. 2 first rank.mp. 3 first?rank.mp. 4 FRS$.mp. 5 Schneiderian.mp 6 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 (588) |

| Phase II Date: 01‐06‐11 |

1 exp "International Classification of Diseases"/ (747) 2 "Research Diagnostic Criteria".mp. (1393) 3 Feighner.mp. (169) 4 ICD.mp. (4427) 5 DSM.mp. (42426) 6 RDC.mp. (392) 7 schneider.mp. (1283) 8 bleuler.mp. (464) 9 kraepelin.mp. (736) 10 "international pilot study of schizophrenia".mp. (68) 11 IPSS.mp. (53) 12 "new haven schizophrenia index".mp. (20) 13 NHSI.mp. (7) 14 "present state examination".mp. (811) 15 PSE.mp. (440) 16 "operational criteria".mp. (462) 17 (operation$ adj3 criteri$).mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures] (810) 18 Diagnosis/ (25820) 19 "Research Diagnostic Criteria".mp. (1393) 20 exp "Diagnostic and Statistical Manual"/ (4184) 21 exp Research Diagnostic Criteria/ (122) 22 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 (72691) 23 exp SCHIZOPHRENIA/ (62498) 24 schizophren$.mp. (88734) 25 23 or 24 (88734) 26 22 and 25 (10364) 27 limit 26 to human (10180) |

|

| MEDION | Date: 24‐02‐11 02‐12‐13 |

(schizophrenia or schizophrenic or schizophreniform in title or abstract) or (psychosis or psychoses or psychotic in title or abstract) (11) |

All databases searched from inception.

All searches were undertaken, added to a common database and duplicates deleted.

We did not apply any restrictions based on language or type of document in the search. We used the 'multiple fields' search command for the OvidSP interface (.mp.) to search both text and database subject heading fields. To capture variations in suffix endings, the truncation operator ‘$’ was used.

The Cochrane Register of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies was not searched as the content had been covered by the other databases searched in this review, and because this resource was out of date at the time of the searches.

Searching other resources

Additional references were identified by manually searching references of included studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Review authors independently screened all titles and abstracts for eligibility. As there were 35,410 references to screen from the search, the screening was done by a team of review authors, see Contributions of authors and Acknowledgements for details. We retrieved full papers of potentially relevant studies, as well as review articles, if relevant, for manual reference search. NM and KSW independently reviewed full papers for eligibility according to the inclusion criteria detailed above. Abstracts, in the absence of a full publication, were included if sufficient data were provided for analysis. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion between NM and KSW and all decisions documented. If a consensus could not be reached, CEA or CD made the final decision regarding these studies.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction forms were developed using a web‐based software and piloted on a small selection of studies. NM and KSW, again working independently, completed data extraction forms for all included studies. Agreements and disagreements were recorded and resolved by discussion between NM and KSW. If a consensus could not be reached, CEA made the final decision regarding these studies.

We extracted the information on study characteristics listed in Table 6.

5. Study characteristics.

| Study Details | First author, year, publication status, country, aim of study |

| Patient characteristics and setting | Number of participants included in study and number in analysis Description of participants in the study (age, gender, ethnicity, comorbid disorders, duration of symptoms, and concurrent medications used) Predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria Study aim Previous treatment for schizophrenia Clinical setting Country |

| Index test | Description of FRS used Professionals performing test Resolution of discrepancies How FRS used in study |

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Reference standard Target condition(s) Professionals performing test Resolution of discrepancies |

| Flow and timing | Study process Follow‐up |

FRS: first rank symptoms

We recorded the number of true positive (TP), true negative (TN), false positive (FP), false negative (FN) to construct a 2 x 2 table for each study for differentiating schizophrenia from other diagnoses, from other psychotic diagnoses and from non‐psychotic diagnoses. If such data were not available, we attempted to derive them from summary statistics such as sensitivity, specificity, and/or likelihood ratios if reported. We treated data as dichotomous. Where data were available for one and/or multiple FRS, or at several time points, we recorded these.

Assessment of methodological quality

We used QUADAS‐2 (Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies), an updated version of the original QUADAS tool for the assessment of quality in systematic reviews of diagnostic accuracy studies (Whiting 2011). The QUADAS‐2 tool is made up of four domains: patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow and timing. We tailored the tool to our review, which was used to judge the risk of bias and applicability of included studies. Included studies were assessed by NM and KSW, working independently using a form that we piloted on a small selection of studies. The inter‐rater agreement was then measured and the form adapted (see Appendix 1). It was then applied to the other included studies. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus with CEA and CD.

The results of the quality assessment were used to describe the internal validity and external validity (applicability)of the included studies. The results were also used to make recommendations for the design of future studies. We are aware that quality rating is important but also that it is problematic to pre‐define cut‐off points beyond which inclusion of data would be contraindicated. We, therefore, did not use QUADAS‐2 other than to help the qualitative commentary.

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

Estimates of sensitivity and specificity from each study were plotted in receiver operating characteristic (ROC) space and forest plots for visual assessment of variation in test accuracy were constructed. Meta‐analyses were performed using the SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) program MetaDAS to fit the bivariate model, which was developed by Takwoingi (Takwoingi 2010) adapting program codes by Macaskill (Macaskill 2004). The program incorporates the precision by which sensitivity and specificity have been measured in each study (Reitsma 2005) and fits the model based on the generalised linear mixed model approach proposed by Chu and Cole (Chu 2006), allowing the automated fitting of bivariate and HSROC models. The bivariate model was used based on that all the included studies had a common test threshold.

Summary estimates were obtained for sensitivity and specificity of differential diagnosis of schizophrenia using FRS and diagnosis by a psychiatrist. Where the bivariate model failed to converge in SAS, we refitted the model using xtmelogit in Stata 12 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). Parameter estimates were entered into RevMan for generation of SROC plots. Additional plots were constructed using Stata 12.

Investigations of heterogeneity

Covariates and their subgroups were added into the bivariate model to investigate sources of heterogeneity by using the MetaDAS program. Assessment of the effect of covariate subgroups on sensitivity and/or specificity by comparing models with and without the covariate were performed using likelihood ratio tests to evaluate the statistical significance of differences in model fit.

We investigated the following possible sources of heterogeneity.

Whether operational criteria were used as part of the reference standard (abbreviated to ‘Criteria’)

Whether FRS were used as part of the reference standard (abbreviated to ‘FRS/RS’)

All psychotic and non‐psychotic admissions to a psychiatric ward or only people with psychoses (abbreviated to ‘Diagnosis’)

Whether the definition of schizophrenia in the study included schizoaffective and/or schizophreniform (abbreviated to ‘Psychosis’)

Test positivity threshold, i.e. number of FRS needed for a diagnosis of schizophrenia (abbreviated to ‘Number’)

Results were divided into the following diagnostic test types.

Schizophrenia from all other psychotic and non‐psychotic diagnoses

Schizophrenia from other types of psychosis

Schizophrenia from non‐psychotic disorders

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses had been planned to investigate the impact of blinding when conducting the tests, but due to the limited number of studies that reported whether the testers were blinded, this was not possible and so could not be performed.

Assessment of reporting bias

It has previously been described that standard funnel plots and tests for publication bias are likely to be misleading for meta‐analysis of test accuracy studies (Deeks 2005), therefore no assessment of publication bias was carried out.

Results

Results of the search

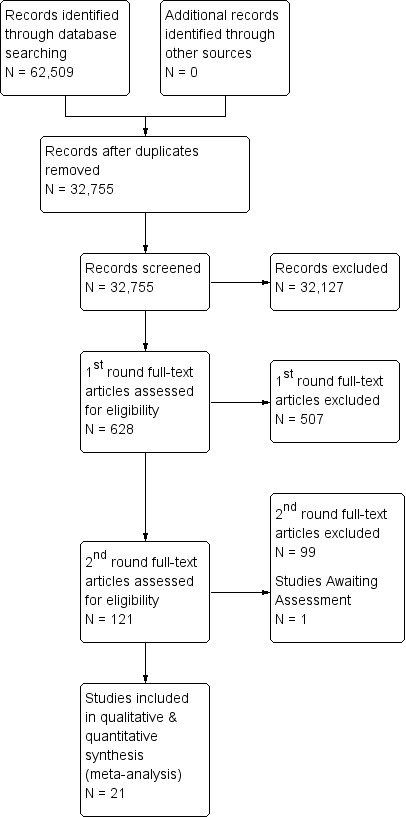

We screened 32,755 potentially relevant references for inclusion. We excluded 32,127 references through title and abstract screening. An initial first round full text assessment of the remaining 628 references resulted in 507 references being excluded mainly because they were not diagnostic studies or FRSs were not being assessed. Following a second round of full text screening, a further 99 references were excluded (see Characteristics of excluded studies for details of reasons for exclusion). We included 21 studies (25 references; 4 were companion papers), and an additional study in German is awaiting assessment. See Figure 1 for an overview of the selection process.

1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Included studies

1. Study Design

Seventeen studies were prospective and three studies were retrospective (Daradkeh 1995; Stephens 1980; Stephens 1982); Brockington 1978 included both a prospective sample and a retrospective sample of participants. Twelve studies consecutively enrolled participants, three randomly selected participants (Chandrasena 1987; Raguram 1985; Wu 1990); Stephens 1980 randomly selected participants from a previous study; Daradkeh 1995 also selected participants from a previous study, but did not report whether this was random;and four studies did not report how participants were enrolled (Brockington 1978; Rosen 2011; Salleh 1992; Tanenberg‐Karant 1995).

All included studies diagnosed participants with psychosis using an accepted reference standard, assessed the FRS of participants, and provided data that we could use to construct 2 x 2 tables. However, only five studies (Daradkeh 1995; Ihara 2009; Peralta 1999; Ramperti 2010l Salleh 1992) were specifically designed as diagnostic test accuracy studies. Seven studies aimed to investigate the utility of FRSs to diagnose participants, and eight measured the prevalence of FRSs in people diagnosed with schizophrenia. A single study (Preiser 1979) tested FRSs for assessing the prognosis of participants.

2. Setting

Sixteen studies were undertaken in inpatient settings, two in both inpatient and outpatient departments (Ihara 2009; Ramperti 2010), one in an outpatient setting (Raguram 1985); two studies did not report on setting (Daradkeh 1995; Rosen 2011).

Studies were conducted in the USA (six studies), UK (three studies), India (two studies), Spain (two studies), Australia, China, Ireland, Kenya, United Arab Emirates, and Malaysia. Carpenter 1974 was an international study including multiple sites (China (Taiwan), Colombia, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, India, Nigeria, USSR, UK, USA), and Chandrasena 1987 was a triple site study (Sri Lanka, UK, and Canada).

Studies were conducted from 1974 to 2011. Only four studies were conducted after 2000 (Gonzalez‐Pinto 2004; Ihara 2009; Ramperti 2010; Rosen 2011). Three studies were conducted in the 1970's (Brockington 1978; Carpenter 1974; Preiser 1979), eight in the 1980's (Chandrasena 1987; Chopra 1987; Ndetei 1983; Radhakrishnan 1983; Raguram 1985; Stephens 1980; Stephens 1982; Tandon 1987) and six in the 1990's (Daradkeh 1995; O'Grady 1990; Peralta 1999; Salleh 1992; Tanenberg‐Karant 1995; Wu 1990).

3. Participants

The included studies had a total of 6253 participants, although only 5515 were included in the analysis. Thirteen studies included only participants with psychosis. Seven studies included all admissions to psychiatric wards with psychotic and non‐psychotic symptoms (Ndetei 1983; O'Grady 1990; Preiser 1979; Radhakrishnan 1983; Stephens 1982; Tandon 1987; Wu 1990).

Six studies included people with first episode psychosis or first admissions to hospital (Gonzalez‐Pinto 2004;, Ihara 2009; Ndetei 1983; Ramperti 2010; Salleh 1992; Tanenberg‐Karant 1995); the duration of psychotic symptoms was not reported in the other 15 studies.

In 17 studies participants’ ages ranged from 16 to 89 years; four studies did not report on age. Thirteen studies included both males and females; this was not reported in the remaining studies. Most studies did not report details about participants’ ethnicity.

4. Index test

At least one FRS was needed to diagnose schizophrenia in 12 studies, and nine studies did not report the number of FRS needed for a diagnosis. For these studies we assumed the same threshold, at least one FRS.

Many studies did not specifically use FRSs to make a diagnosis of schizophrenia, but measured the prevalence of FRSs. For these studies, we assumed that the number of FRSs reported in the study was the number of FRSs needed to diagnose schizophrenia, e.g. if the prevalence was reported as number of people experiencing at least one FRS, we included this as at least one FRS to diagnose schizophrenia.

5. Reference standard

Four studies assessed patients' medical records to make a diagnosis (Brockington 1978; Ihara 2009; Stephens 1980; Stephens 1982), seven studies used both medical records and clinical interview, and nine studies used only clinical interview. Operational criteria were part of the reference standard in all studies apart from Brockington 1978 (See Characteristics of included studies for details). The reference standard included FRSs in 13 studies, and it was unclear in the remaining studies.

6. Target condition

Nine studies specified that their target condition was schizophrenia alone and did not include other schizophrenic‐like illnesses. Three studies also included schizoaffective and/or schizophreniform disorders in their definition of schizophrenia (Carpenter 1974; Ramperti 2010; Tanenberg‐Karant 1995). The remaining nine studies did not specify whether schizophrenia also included other types of schizophrenia‐like conditions.

Excluded studies

We excluded 99 reports, the majority for more than one reason: 50 studies were excluded because of insufficient data to construct 2 x 2 tables; 41 studies included only participants diagnosed with schizophrenia; 35 studies included participants who did not present with psychotic symptoms; 30 studies did not use the reference standard to separate those with schizophrenia from those without; 22 studies did not have FRS routinely performed on patients. See Characteristics of excluded studies for further details.

Awaiting assessment studies

Friedrich 1980 is in German and currently awaiting translation; see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Ongoing studies

We found no ongoing studies.

Methodological quality of included studies

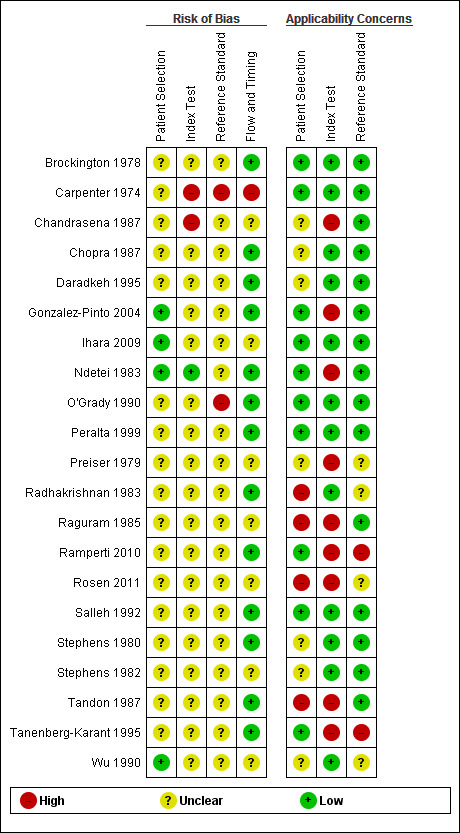

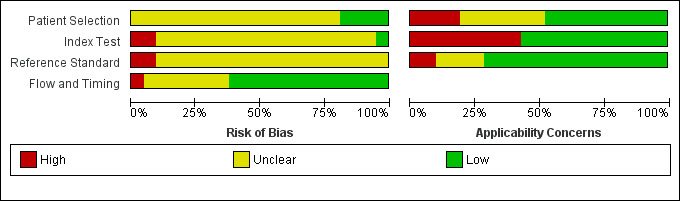

See also risk of bias and applicability concerns in Characteristics of included studies, Figure 2, and Figure 3for an overview of the assessment of risk of bias and applicability concerns for each of the 21 studies included in the review.

2.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns summary: review authors' judgements about each domain for each included study

3.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns graph: review authors' judgements about each domain presented as percentages across included studies

1. Patient Selection

Twelve studies (57%) used a consecutive or random sample of patients; one study (Daradkeh 1995) selected participants from a previous study and in the remainder the method of selection of participants was unclear. Twelve studies (57%) did not use a case‐control design and nine studies (43%) either used a case‐control design or it was unclear whether this was the design. Eight studies (38%) avoided inappropriate exclusions and it was unclear how exclusions were managed in the remaining studies. As a result, 17 studies (81%) were considered as having an unclear risk of bias and four were low risk. In terms of applicability, we judged 10 included studies (48%) to be of low concern, four (19%) to be of high concern and the remaining to be of unclear applicability concerns.

2. Index test

Only seven studies (33%) reported that the index test results were interpreted without knowledge of the result of the reference standard, in one study (Carpenter 1974) the results were interpreted with knowledge of the reference standard, and in the remainder it was unclear. The number of FRSs required for a diagnosis of schizophrenia was only reported in seven studies (33%). As a result 17 studies (81%) were considered to be at unclear risk of bias, two (10%) to be high risk and only one low risk of bias. In terms of applicability, nine (43%) were judged as high concern because the aim of the studies was not to test FRSs specifically as a means of diagnosing schizophrenia, but to measure prevalence or to assess the prognosis of patients.

3. Reference standard

In 12 studies (57%), the reference standard was described and would correctly classify schizophrenia; nine studies (43%) did not clearly report what methods were used as the reference standard. Only three studies (14%) reported that the reference standard was interpreted without knowledge of the index test result, in four studies (19%) the person using the reference standard was unblinded to the results of the index test, and it was unclear in the remaining studies. As a result, all studies were rated as unclear or high risk of bias. In terms of applicability, six studies (29%) were considered as unclear or high concern as the target condition of schizophrenia as defined by the reference standard included schizophrenia‐like illnesses.

4. Flow and timing

We considered 13 studies (62%) to be of low concern for risk of bias since in most of these studies all participants received the same reference standard and the same index test, they accounted for all of their participants in the analysis, although 11 studies (52%) did not clearly report the interval between the reference standard and index test. One study was considered as high risk, as they did not apply the reference standard and index test to all participants and not all participants were included in the analysis. Seven studies (33%) had an unclear risk of bias on this domain due to insufficient reporting.

Findings

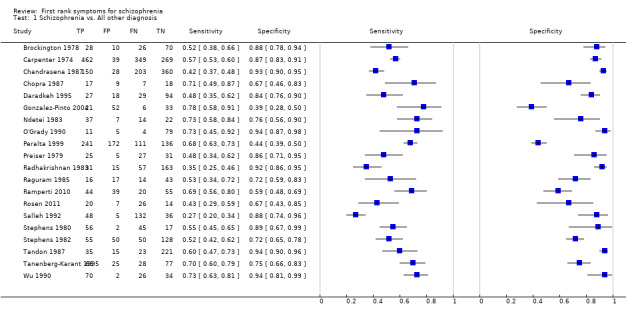

1. FRS to differentiate schizophrenia from all other psychotic and non‐psychotic diagnoses

Twenty studies (5079 participants) were included in the meta‐analysis. The median sample size was 146 (range 51 to 1119). Study sensitivities ranged from 27% to 78% and specificities from 39% to 94%. The summary sensitivity and specificity (95% CI) were 57.0% (50.4% to 63.3%) and 81.4% (74.0% to 87.1%) respectively (Data table 1; Figure 4).

1. Test.

Schizophrenia vs. All other diagnosis.

4.

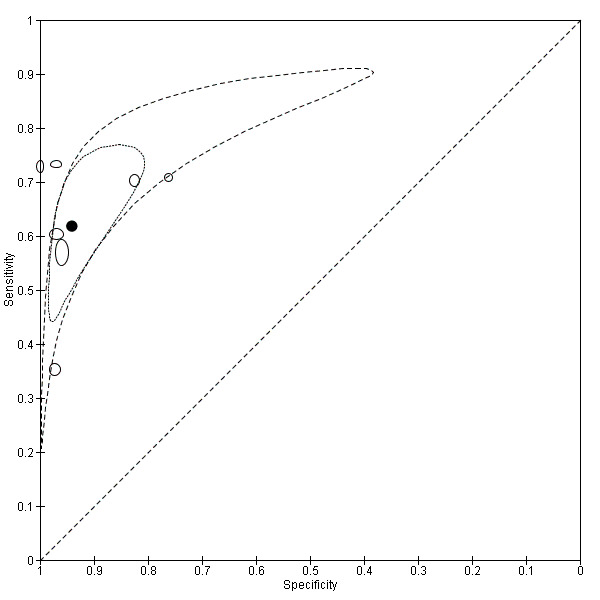

Summary ROC Plot of 1. FRS to differentiate schizophrenia from all other psychotic and non‐psychotic diagnoses

2. FRS to differentiate schizophrenia from other types of psychosis

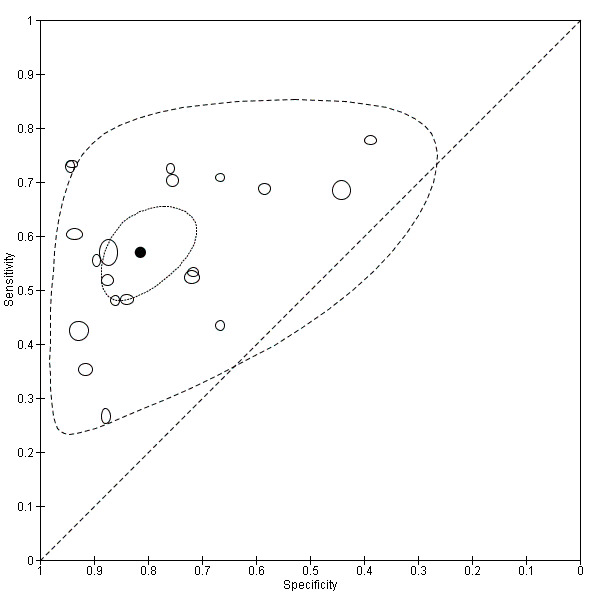

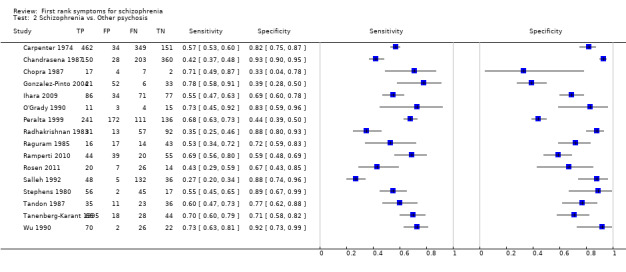

The meta‐analysis included 16 studies (4070 participants). The median sample size was 138 (range 30 to 996). Study sensitivities ranged from 27% to 78% and specificities from 33% to 93%. The summary sensitivity and specificity (95% CI) were 58.0% (50.3% to 65.3%) and 74.7% (65.2% to 82.3%) respectively (Data table 2; Figure 5).

2. Test.

Schizophrenia vs. Other psychosis.

5.

Summary ROC Plot of 2. FRS to differentiate schizophrenia from other types of psychosis

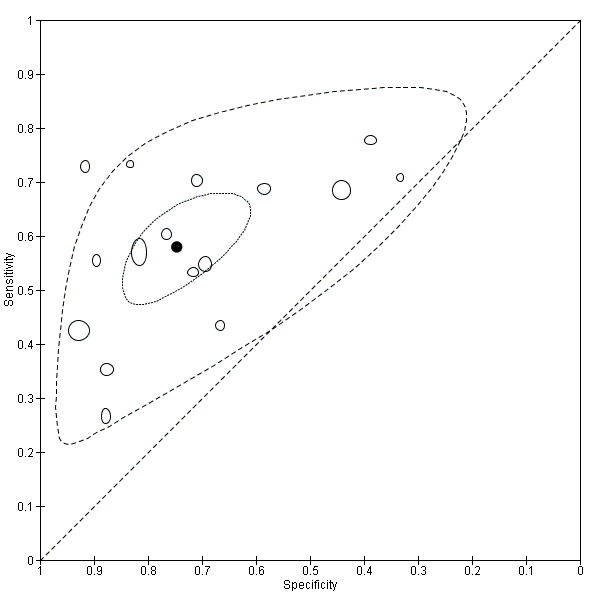

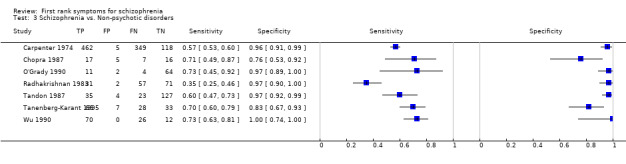

3. FRS to differentiate schizophrenia from non‐psychotic disorders

The meta‐analysis consisted of seven studies (1652 participants). The median sample size was 134 (range 45 to 934). Study sensitivities ranged from 35% to 73% and specificities ranges from 76% to 100%. The summary sensitivity and specificity (95% CI) were 61.8% (51.7% to 71.0%) and 94.1% (88.0% to 97.2%) respectively (Data table 3; Figure 6).

3. Test.

Schizophrenia vs. Non‐psychotic disorders.

6.

Summary ROC Plot of 3. FRS to differentiate schizophrenia from non‐psychotic disorders

Investigation of heterogeneity

We formally investigated the effect of the following covariates on sensitivity and specificity: operational criteria used as part of the reference standard; FRS used as part of the reference standard; all admissions to a psychiatric ward or with specific psychoses; if definition included schizoaffective and/or schizophreniform; and number of FRS needed for a diagnosis. Each covariate comprised of several subgroups, where adequate data allowed, these subgroups were investigated as sources of heterogeneity.

1. FRS to differentiate schizophrenia from all other psychotic and non‐psychotic diagnoses

The investigation of heterogeneity results for FRS to differentiate schizophrenia from all other psychotic and non‐psychotic diagnoses can be found in Table 7.

6. Investigations into heterogeneity between subgroups of tests using first rank symptoms to diagnose schizophrenia versus all other diagnoses.

| Schizophrenia versus all other diagnoses | Number of studies | Number of patients |

Summary of sensitivity % (95% CI) |

Summary of specificity % (95% CI) |

Likelihood Ratio Test1 (P‐value) |

|

| Operational criteria used as part of reference standard | DSM‐III | 4 | 1190 | 64.8 (54.3, 74.0) | 64.2 (52.8, 74.2) | 0.002 |

| ICD‐9 | 5 | 2515 | 42.0 (33.5, 51.0) | 89.8 (84.9, 93.2) | ||

| First rank symptoms used as part of reference standard | Unclear | 6 | 1629 | 60.9 (49.3, 71.4) | 85.3 (71.9, 93.0) | 0.3 |

| Yes | 13 | 3316 | 55.3 (47.2, 63.2) | 79.2 (69.2, 86.5) | ||

| All admissions to a psychiatric ward or with specific psychoses | All hospitalised | 8 | 1293 | 59.7 (49.2, 69.4) | 86.7 (77.3, 92.6) | 0.1 |

| Psychosis only | 12 | 3786 | 55.6 (47.3, 63.5) | 77.2 (66.9, 85.0) | ||

| If definition included schizoaffective and/or schizophreniform | Not reported | 9 | 1855 | 45.8 (38.4, 53.3) | 85.1 (75.1, 91.5) | 0.03 |

| Schizophrenic only | 7 | 1619 | 63.2 (54.4, 71.2) | 76.0 (60.6, 86.6) | ||

| Number of first rank symptoms needed for a diagnosis of schizophrenia | At least one | 10 | 3143 | 58.6 (49.5, 67.1) | 76.6 (65.0, 85.3) | 0.5 |

| Not reported | 9 | 1195 | 57.1 (47.1, 66.6) | 84.4 (74.2, 91.0) | ||

1Likelihood ratio test for model with and without covariate DSM: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder ICD: International Statistical Classification of Diseases

1.1 Covariate: “whether operational criteria were used as part of the reference standard” (Criteria)

This covariate contained 10 subgroups (Bleurian/ego (n = 1), Feighner's (n = 1), RDC (n = 3), DSM‐II (n = 1), DSM‐III (n = 4), DSM‐IV (n = 2), ICD (n = 5), 1984 Mt Huangshan (n = 1), New Haven (n = 1) and Not reported (n = 1)), however only two subgroups: ICD criteria (ICD‐8 n = 1, ICD‐9 n = 3 and ICD‐10 n = 1) and DSM‐III criteria (n = 4) had enough data to enable statistical analyses. There was a statistically significant difference (P = 0.002) in sensitivity and specificity for FRS to detect schizophrenia when studies used DSM‐III or ICD as reference standard. FRS to detect schizophrenia showed higher sensitivity but lower specificity when DSM‐III criteria were used as reference standard compared to when ICD criteria were used as reference standard. The summary sensitivity of FRS to detect schizophrenia was 64.8% (54.3% to 74.0%) with DSM‐III as reference standard and 42.0% (33.5% to 51.0%) with ICD as reference standard. The summary specificity of FRS to detect schizophrenia with DSM‐III as reference standard was 64.2% (52.8% to 74.2%) and with ICD as reference standard was 89.8% (84.9% to 93.2%).

1.2 Covariate: “whether FRS were used as part of the reference standard” (FRS/RS)

This covariate contained three subgroups (Yes, Unclear and Not reported) but only two of which, ‘yes’ (n = 13) and ‘unclear’ (n = 6) contained enough data to investigate heterogeneity. No statistical significance between these subgroups was detected (P = 0.3), indicating they are unlikely as a source of heterogeneity.

1.3 Covariate: “all psychotic and non‐psychotic admissions to a psychiatric ward or only people with psychoses” (Diagnosis)

This covariate contained two subgroups: ‘psychosis only’ (n = 12) and ‘all hospitalised’ (n = 8), both of which contained enough data to allow heterogeneity analysis. No statistical significance was found between these subgroups (P = 0.1), indicating these are unlikely as a source of heterogeneity.

1.4 Covariate: “whether the definition included schizoaffective and/or schizophreniform” (Psychosis)

This covariate contained four subgroups (Only schizophrenia, Schizophrenia plus others, Unclear and Not reported), but only two contained enough data to investigate heterogeneity: ‘not reported’ (n = 9) and ‘Schizophrenia only’ (n = 7). A statistically significant difference (P = 0.03) was found in sensitivity and specificity for FRS to detect schizophrenia when only schizophrenia was included in the definition for the diagnosis compared to when it was unclear what definition for the diagnosis was used. Findings indicated that when only schizophrenia was included in the diagnosis definition, sensitivity of FRS to diagnose schizophrenia increases but specificity decreases in comparison with tests where the definition used was not reported. The summary sensitivity was 45.8% (38.4% to 53.3%) for not reported definitions and 63.2% (54.4% to 71.2%) for the definition of schizophrenia only. The summary specificity was 85.1% (75.1% to 91.5%) for not reported definitions and 76.0% (60.6% to 86.6%) for a definition of schizophrenia only.

1.5 Covariate: “number of FRS needed for a diagnosis of Schizophrenia” (Number)

This covariate contained two subgroups: ‘at least 1’ (n = 8) and ‘not reported’ (n = 7). No statistical significance was found between these subgroups (P = 0.5), indicating these are unlikely as a source of heterogeneity.

2. FRS to differentiate schizophrenia from other types of psychosis

The investigation of heterogeneity results for FRS to differentiate schizophrenia from all other psychotic and non‐psychotic diagnoses can be found in Table 8.

7. Investigations of heterogeneity between subgroups of tests using first rank symptoms to diagnose schizophrenia versus other psychoses.

| Schizophrenia versus other psychoses | Number of studies | Number of patients | Summary sensitivity % (95% CI) |

Summary specificity % (95% CI) |

Likelihood Ratio Test[1] (P value) | |

| First rank symptoms used as part of reference standard: | Yes | 4 | 1326 | 60.9 (46.5, 736.) | 82.3 (65.0, 92.1) | 0.1 |

| Unclear | 12 | 2744 | 56.8 (48.1, 65.0) | 72.0 (60.6, 81.1) | ||

| All admissions to a psychiatric ward or with specific psychoses: | All hospitalised | 5 | 481 | 62.1 (47.8, 74.5) | 79.3 (62.0, 90.0) | 0.3 |

| Psychosis only | 11 | 3589 | 56.7 (47.7, 65.2) | 73.2 (61.1, 82.1) | ||

| If definition included schizoaffective and/or schizophreniform: | Not reported | 5 | 1312 | 39.6 (32.1, 47.6) | 85.3 (73.5, 92.4) | 0.004 |

| Schizophrenic only | 7 | 1328 | 63.3 (56.3, 69.9) | 63.6 (48.1, 76.7) | ||

| Number of first rank symptoms needed for a diagnosis of schizophrenia: | At least one | 8 | 2608 | 58.7 (48.0, 68.6) | 69.3 (56.9, 79.5) | 0.5 |

| Not reported | 7 | 721 | 59.8 (47.8, 70.8) | 76.6 (63.0, 86.3) | ||

1Likelihood ratio test for model with and without covariate

2.1 Covariate: “whether operational criteria were used as part of the reference standard” (Criteria)

This covariate contained seven subgroups (DSM‐II (n = 1), DSM‐III (n = 3), DSM‐IV (n = 3), Feighner's (n = 1), ICD (n = 5), RDC (n = 3) and 1984 Mt Huangshan (n = 1)). As only one subgroup had enough data points for analysis (ICD), no statistical testing for heterogeneity could be performed.

2.2 Covariate: “whether FRS were used as part of the reference standard” (FRS/RS)

This covariate contained two subgroups: ‘yes’ (n = 4) and ‘unclear’ (n = 12). No statistical significance was found between the subgroups (P = 0.1), indicating they unlikely as a source of heterogeneity.

2.3 Covariate: “all admissions to a psychiatric ward or people with specific psychosis” (Diagnosis)

This covariate contained two subgroups: ‘psychosis only’ (n = 11) and ‘all hospitalised’ (n = 5). No statistical significance was found between the subgroups (P = 0.3), indicating these subgroups are unlikely as a source of heterogeneity.

2.4 Covariate: “whether the definition included schizoaffective and/or schizophreniform” (Psychosis)

This covariate contained two subgroups: ‘not reported’ (n = 5) and ‘schizophrenic only’ (n = 7). There was a statistically significant difference (P = 0.004) in sensitivity and specificity for FRS to detect schizophrenia when only schizophrenia was included in the definition for the diagnosis compared to when it was unclear what definition for the diagnosis was used. Findings indicated that when only schizophrenia was included in the diagnosis definition, sensitivity of FRS to diagnose schizophrenia increases but specificity decreases in comparison with tests where the definition used was not reported. The summary sensitivity was 39.6% (32.1% to 47.6%) for not reported definitions and 63.3% (56.3% to 69.9%) for schizophrenia only as definition. The summary specificity was 85.3% (73.5% to 92.4%) for not reported definitions and 63.6% (48.1% to 76.7%) for schizophrenia only as definition.

2.5 Covariate: “number of FRS needed for a diagnosis of Schizophrenia” (Number)

This covariate had two subgroups: ‘at least one’ (n = 8) and ‘not reported’ (n = 7). No statistical significance was found between the subgroups (P = 0.5), indicating these are unlikely as a source of heterogeneity.

3. FRS to differentiate schizophrenia from non‐psychotic disorders

We planned to investigate sources of heterogeneity but due to the limited number of studies available for each covariate and their respective subgroups, but this was not possible.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This systematic review included a total of 21 studies evaluating the efficacy of FRS in diagnosing schizophrenia: 13 studies in people only with psychotic symptoms and eight studies in people with both psychotic and non‐psychotic symptoms who were admitted to a psychiatric ward. Only five studies were specifically designed as diagnostic test accuracy studies and the majority were based in a research rather than a clinical setting. The studies had a total of 6253 participants and 5515 were included in the analysis. Six studies included people with first episode psychosis or first admissions to hospital, although none reported the duration of symptoms. For the index test, just over half the studies diagnosed schizophrenia by the presence of at least one FRS, and the rest did not report the number of FRS needed for a diagnosis. The reference standard varied between studies and included clinical interview, medical records and operational criteria in various combinations. In nine studies, the target condition was schizophrenia alone, whereas three studies also included other schizophrenic‐like illnesses, and the remainder did not report this.

The quality assessments of the studies were mostly an unclear risk of bias regarding patient selection, use of index test and reference standard as important issues such as how patients were selected and the blinding of those conducting the tests were not reported. The reporting of the flow and timing of the studies was better and subsequently 62% were rated as a low risk of bias.

A summary of the results is given in Table 9, and details of the investigations of heterogeneity can be found in Table 7 and Table 8. Table 1 gives information on the quantity, quality and applicability of evidence as well as the accuracy of index test.

8. Summary sensitivity and specificity of first rank symptoms for diagnosis of schizophrenia.

| Test Comparison | Number of studies | Number of patients |

Summary sensitivity % (95% CI) |

Summary specificity % (95% CI) |

| Schizophrenia versus all other diagnoses | 20 | 5079 | 57.0 (50.4, 63.3) | 81.4 (74.0, 87.1) |

| Schizophrenia versus other types of psychosis | 16 | 4070 | 58.0 (50.3, 65.3) | 74.7 (85.2, 82.3) |

| Schizophrenia versus non‐psychotic disorders | 7 | 1652 | 61.8 (51.7, 71.0) | 94.1 (88.0, 97.2) |

1. FRS to differentiate schizophrenia from all other psychotic and non‐psychotic diagnoses

Twenty‐one studies reported results for diagnosing schizophrenia from all other diagnoses. The summary sensitivity was 57%, meaning that for every 100 people with schizophrenia the test will correctly identify 57 cases as positive for schizophrenia, therefore almost half of cases would be incorrectly diagnosed as not having schizophrenia. The summary specificity was better, at 81.4%, meaning that of 100 people without schizophrenia 81 would be found negative, but 19 would incorrectly receive a positive diagnosis for schizophrenia.

2. FRS to differentiate schizophrenia from other types of psychosis

Sixteen studies reported results for diagnosing schizophrenia from other types of psychosis. Results were very similar to schizophrenia from all other diagnoses, with the summary sensitivity slightly higher at 58%, meaning that for every 100 people with schizophrenia the test will find only 58 cases as positive for schizophrenia, therefore almost half of cases would be incorrectly diagnosed as not having schizophrenia. The results showed a slightly lower summary specificity of 76.7%, meaning that of 100 people without schizophrenia 77, would be found negative, but 23 would incorrectly receive a positive diagnosis for schizophrenia.

3. FRS to differentiate schizophrenia from non‐psychotic disorders

Seven studies reported results for diagnosing schizophrenia from non‐psychotic disorders. The results were only slightly better for summary sensitivity at 61.8%, meaning that for every 100 people with schizophrenia the test will find only 62 cases as positive for schizophrenia, and the remainder of cases would be incorrectly diagnosed as having a non‐psychotic disorder. The summary specificity was 94.1%, meaning that most people without schizophrenia would receive a negative schizophrenic diagnosis.

4. Investigations of heterogeneity

The investigations of heterogeneity between the subgroups showed no significant difference (P = 0.1) in sensitivity and specificity when admissions to a psychiatric ward was compared to those with specific psychoses, which might be expected, particularly in the studies conducted 20 to 30 years ago, in which most patients who were hospitalised would have psychotic symptoms or some severe mental health symptoms.

A significant difference (P = 0.002) was found when the reference standard including DSM‐III criteria were compared with reference standard including ICD (8, 9 and 10) criteria, with DSM‐III showing higher sensitivity but a lower specificity compared to the ICD criteria. Four out of the five ICD studies used ICD‐8 or ICD‐9, neither of which connect length of time to symptoms, whereas DSM‐III requires symptoms to have been present for at least six months. Furthermore, as only six studies included patients with a first psychotic episode, we cannot exclude the influence on diagnosis of patients having already been diagnosed with a chronic mental illness, and potentially previously received treatment. In addition, it is not possible to interpret the results for first rank symptoms used as part of reference standard and the number of first rank symptoms needed for a diagnosis of schizophrenia, as each subgroup was compared with studies that did not report this.

Strengths and weaknesses of the included studies

There were several limitations in the quality of included studies that may have lead to overestimation of test accuracy. The majority of included studies, although they provided useable data, were not designed to assess the diagnostic test accuracy of FRS. This meant that methodological details were often poorly reported, the enrolment of participants was not clearly stated and participants may have undergone some degree of selection to be included in the studies that does not reflect the range of patients that would present in clinical practice. The methodological quality of the studies was mostly rated as unclear due to these limitations, although the reporting for flow and timing was generally better with around half the studies rated as low risk of bias.

Primarily we were interested in studies that enrolled only participants with psychotic symptoms, although eight out of the 21 included studies enrolled all admissions to the psychiatric ward, meaning that other diagnoses were also present. However, subgroup analyses showed only a small difference in sensitivity and specificity when these studies were removed from the analysis.

There was a lack of consistency across the studies in the reporting of the reference standard and the type of reference standard when this was reported. Some studies reported that the reference standard was "medical records", and we had to presume that this meant a record of a clinical interview, which may have introduced bias.

Just over half the studies did not report the time interval between reference standard and index test. Out of the studies that did report the interval, only one retrospective study had an interval longer than four weeks.

A positive result for schizophrenia on the index test was defined as the presence of at least one FRS in 12 studies (57%). We assumed the same cut‐off for the remaining nine studies that did not report the number of FRSs required for a positive diagnosis of schizophrenia. There was no statistically significant difference between the studies that defined at least one and those that did not make a definition for how many FRS were required for a diagnosis (P = 0.5). Furthermore, eight studies were prevalence studies that reported the proportion of people with at least one FRS. For these studies we used "the proportion of people with at least one FRS" as a proxy for diagnosis of schizophrenia as it was the same cut‐off used in the diagnostic studies.

There were differences in what constituted a diagnosis of schizophrenia across studies, with three studies including schizoaffective and/or schizophreniform disorders and nine studies not reporting what was included.

Strengths and weaknesses of the review

The search strategy that we used was very wide and meant that we had over 35,000 references to screen. On the one hand, this meant that we feel certain that all possible studies were included, but on the other hand, the sheer volume of screening may have meant that some relevant studies may have been erroneously excluded. We have one article in German that is yet to be translated. There was some disagreement in selecting papers, as most of the eventually included studies were not specifically designed as diagnostic test accuracy studies, or included all admissions to the psychiatric ward as opposed to those with psychotic symptoms only, and therefore most of the final decisions to include studies took some discussion between review authors. We also found that the completion of QUADAS‐2 also involved discussion between review authors, mostly because the studies were again not designed as diagnostic test accuracy studies and many of the signalling questions were rated unclear due to lack of reporting of relevant details, which also made it difficult to judge the risk of bias of the QUADAS‐2 domains.

Although there was a large amount of heterogeneity of results across studies with wide ranges of sensitivity and specificity, the decision of pooling the results and obtaining a summary estimate was made to support those, particularly in low‐ and middle‐income countries, that might use FRS to triage patients. We caution, however, that in our investigations of heterogeneity, we identified significant sources of variability in the results, in particular, the variation in the reference standard used for the diagnosis (DSM‐III or ICD‐8, 9, or 10) (P = 0.002) and the variation in the spectrum of diseases evaluated together with schizophrenia (schizophrenia or schizophreniform and/or schizoaffective disorders) (P = 0.004). We also found that estimates of sensitivity were less precise than specificity because the number of those diagnosed positive was less than the number of those diagnosed negative. Further reasons may be the limited study quality and variation in the index test including its conduct and interpretation.

The diagnostic accuracies presented in this review may be overestimated as FRSs were part of the reference standard in at least 13 of the 21 included studies, However, there was no statistically significant difference (P = 0.3) between diagnostic accuracies for studies where FRSs were part of the reference standard and those where this was unclear. As no study specifically stated that FRSs were not part of the reference standard, this judgment is difficult to make.

Previous research

We know of no other reviews evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of FRSs.

Applicability of findings to the review question

Most (80%) of the 21 studies were conducted in the 1970's (three studies), 1980's (eight studies) and 1990's (six studies), and only four studies were conducted after the year 2000. We acknowledge that there could be an impact of time period on estimates of FRS sensitivity and specificity. This could be due to many reasons, including the change of reference standard, study population, and setting (please see Implications for research). However, when we crudely ordered data by time, there is little indication that this explains the heterogeneity (Figure not shown).

Most of the included studies were based in a research setting and most did not report how patients were selected for inclusion. The studies included both first episode psychosis patients and also those that already had a diagnosis. Only six studies (Gonzalez‐Pinto 2004; Ihara 2009; Ndetei 1983; Ramperti 2010; Salleh 1992; Tanenberg‐Karant 1995) exclusively included patients with first episode psychosis or first admissions, the population most likely to present for diagnostic evaluation in practice. These six studies found similar sensitivities and specificities of FRS to diagnose schizophrenia to the other studies that included a broader spectrum of psychoses (see, for instance, Figure 4).

For those studies that did report it, at least one FRS was used to diagnose schizophrenia. Although indicative of a serious mental disorder, it is not likely that in clinical practice the presence of one of these symptoms would be used to give a firm diagnosis of schizophrenia, and further diagnostic methods would be used.

The reference standard is representative of how schizophrenia is diagnosed, with studies using patient history, clinical interview and possibly operational criteria such as the DSM and ICD.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The wide range of sensitivities and specificities makes summary estimates problematic. Routine use of FRS for triaging patients is likely to result in delayed treatment of some people with schizophrenia or unnecessary treatment of some others without the illness. However, clinical reality is such that in much of psychiatry practice in low‐ and middle‐income countries ‐ where 70% of the world's population live ‐ there are typical ratios of one psychiatrist to one million people (McKenzie 2004). In such situations FRS could remain a useful tool ‐ to help triage potential patients who need to be assessed by a qualified professional. The presence of FRS indicates schizophrenia as a possible diagnosis (as reflected in the inclusion of FRS in the DSM and ICD checklists), but does not exclude a possible diagnosis of other psychoses or non‐psychotic mental disorder.

FRS performs better at 'ruling out' rather than 'ruling in' schizophrenia. This review of FRS accuracy provides clinicians with valuable information to quantify the (moderate) performance of FRS for diagnosis of schizophrenia ‐ indicating the level of uncertainty that should be assigned to an FRS‐based provisional diagnosis. In reality, those with a positive diagnosis, including false positive, would undergo further assessment, even if this assessment, in situations of very limited health resources, was the passage of time. FRS, if used to triage, will identify ‐ to use broad figures related to our findings ‐ about five to 19 people per 100 as being 'FRS' schizophrenia and this will not turn out to be the case. However, it would seem that those five to 19 people, although not experiencing schizophrenia, would be quite disturbed in their behaviour and mental state and still merit some degree of specialist assessment and help.