Abstract

U.S.-born citizens are victims of human trafficking typically exploited through sex trafficking. At least some of them interact with healthcare providers during their trafficking experience; yet a majority goes unidentified. Although protocols and training guides exist, healthcare providers often do not have the necessary skills to identify and assist victims of sex trafficking. Understanding where victims seek care and barriers for disclosure are critical components for intervention. Thus, this study interviewed survivors of sex trafficking to ascertain: a) healthcare settings visited during trafficking, b) reasons for seeking care, and c) barriers to disclosing victimization. An exploratory concurrent mixed-methods approach was utilized. Data were collected between 2016–2017 in San Diego, CA and Philadelphia, PA (N = 21). Key findings: 1) Among healthcare settings, emergency departments (76.2%) and community clinics (71.4%) were the most frequently visited; 2) medical care was sought mainly for treatment of STIs (81%); and 3) main barriers inhibiting disclosure of victimization included feeling ashamed (84%) and a lack of inquiry into the trafficking status from healthcare providers (76.9%). Healthcare settings provide an opportunity to identify victims of sex trafficking, but interventions that are trauma-informed and victim-centered are essential. These may include training providers, ensuring privacy, and a compassionate-care approach.

Keywords: Human trafficking, sex trafficking, medical needs, healthcare settings, disclosure of victimization, mixed methods, United States

Intro/Background

Human Trafficking (HT) or Trafficking in Persons is a global and local criminal activity that tricks, oppresses, forces, deprives, abuses, and controls its victims in inhumane, torturous, and detrimental ways (U.S. Department of Justice, 2017; U.S. Department of State, 2017). In a global context, HT’s manifestations include: commercial sexual exploitation, forced labor, debt bondage, unlawful recruitment of child soldiers, and organ removal without consent (International Labor Organization, 2014; U.S. Department of Justice, 2017; U.S. Department of State, 2017). Unfortunately, HT is also found within the geographical boundaries of the United States of America (U.S.) (International Labor Organization, 2012; U.S. Department of Justice, 2017). In the context of the U.S., HT crimes are most likely to be identified under: a) sex trafficking or commercial sexual exploitation and 2) labor trafficking (Greenbaum, 2016; Polaris Project, 2017; U.S. Department of Justice, 2017). HT is not limited by age, gender, sexual orientation, nationality, socioeconomic status, or geographic location (Polaris Project, 2018; U.S. Department of State, 2017; Bean, 2013. Most likely, victims of HT are often in our midst, yet they go unseen and unidentified continuing to be inhumanly abused.

Defining Human Trafficking

At the turn of the 21st century, the U.S. created a law defining HT for the first time within the context of post-modern society. The Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 (TVPA, 2000), enacted on October 28, 2000, defined HT in the context of the U.S. as “any act that includes coercion,1 commercial sex, debt bondage, and involuntary servitude” (22 USC § 7102). It also defined sex trafficking as “any act through the means of harboring, transporting, providing, obtaining, patronizing, or soliciting of a person for the purpose of exploitation through commercial sex acts.” Child Sex Trafficking or Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking as well as sex and labor trafficking are defined as “severe forms of trafficking in persons” (22 USC § 7102).

Domestic minor sex trafficking includes any sex act induced by force, fraud, or coercion or in which the person forced to perform such acts is younger than 18 years of age (The Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2014; 22 USC § 7102).2 TVPA has been amended and reauthorized several times since its enactment. Previous reauthorizations in 2013 and 2015 were key in making the TVPA a federal law. The 2013 reauthorization “strengthened the ability to prosecute traffickers, added provisions to protect unaccompanied youth, and continued the independent child advocacy program[s] for child trafficking victims and other vulnerable unaccompanied alien children” (California Department of Social Services, 2013). This addition to the law is crucial because HT victims are often criminalized instead of being protected. In 2015, the amendments to the TVPA through the Justice for Victims of Trafficking Act (JVTA, 2015) strengthened this legislation and provided a more victim-centered approach to services on their behalf. The JVTA’s updates created a survivor-led U.S. Advisory Council on Human Trafficking, redirected financial penalties against traffickers into funds aimed at the implementation of medical and social services needed for victims, as well as for trainings of front-line responders in the healthcare and law enforcement communities. It also modified two previously enacted laws – Runaway and Homeless Youth Act (RHYA) and the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA). Within the RHYA, the changes amended the channeling of services for homeless youth who fall into severe forms of trafficking. Within CAPTA, amended changes relative to child pornography and human trafficking were incorporated as part of the description of child abuse (18 USC §3014).

Although these amendments are crucial for potentially providing a paradigm shift as well as the reallocation and redirecting of funds, there is still a great challenge overall in the application of these laws across states and nationally. For example, California and Pennsylvania have recently enacted laws that define HT at the state level to better serve victims as well as to prosecute traffickers, including harsher criminal sentencing (California Department of Social Services, 2013; Leach, 2014). These new laws seek to promote the creation of victim-centered systems and approaches to care and to deliver services for both U,S.-citizens and foreign-born individuals. Yet, complexities in the implementation of the law continue to suppress the opportunity to recognize victims of HT at many levels. A lack of awareness, training, absence of identification protocols and institutionalized plans persist to trump the recognition of victims of HT among law enforcement agents, social service agencies, and healthcare providers. HT victims who are 18 years of age and older tend to be especially affected. More important, at a systems level, these victims continue to be criminalized nationwide.

Risk Factors and Consequences of Sex Trafficking in the U.S

In the U.S., the most at-risk individuals for sex trafficking victimization are characterized by the following descriptors: 1) Female; 2) Between the ages of 12 and 14; 3) Experiencing abuse (e.g., physical, emotional, sexual, drug addiction); 4) Runaway or homeless; 5) Attaining low educational achievement; 6) Participant in the foster care system; 7) Part of the juvenile corrections system; and 8) Member of a non-conformant gender group – LGTBQ (Harpster, 2014; Hossain, 2010; Moore & McOwen, 2013; Rosenblatt, 2014; U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2012; Fong & Cardoso, 2010).

Although the estimates of homeless youth vary, a study conducted in 1999 showed that close to 1.7 million youth had a runaway episode (Hammer, Finkelhor, & Sedlak, 2002). Of the total runaway youth, 71% were at danger of encountering sexual or physical abuse as well as engaging in substance dependency or were located where criminal activity was occurring. Most recently, the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (2017) estimated that one in seven unaccompanied homeless youth – typically also described as runaway or throwaway youth – is likely to be a victim of human trafficking. This amounts to an estimated incidence rate between 200,000–214,000 DMST cases per year (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2009). Between 1998 and 2017, 27 million cases of suspected child sexual exploitation were reported through the CyberTipline of the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (2018).

Efforts to estimate the prevalence of HT adult and child victims of HT in the U.S. have failed. To date, there are no estimates that specify the number of U.S.-born victims including children and adults trapped in either sex or labor trafficking within the nation (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2009). If the most vulnerable subgroups in society are not being identified, assessed, and referred to the most appropriate follow-up services, we are not doing an effective job at intervening, let alone preventing this social peril of HT in the U.S.

Abuse and Potential Health Outcomes of Sex Trafficking

In spite of the existence of public policy since the turn of the 21st century to combat this hideous crime, thousands of vulnerable U.S.-born youth, women, and men find themselves trapped under the HT traffickers’ trickeries, violence and abuses. The range of abuses includes: beatings, burns, tattooing (commonly known as branding), rape, threats, humiliation and forced misuse of drugs with the end goal of control and manipulation (Harpster, 2014; Hodge, 2008; International Labor Organization, 2014; Kotrla, 2010; McClain & Garrity, 2011; Polaris Project, 2018; U.S. Department of Justice, 2017; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2016). Even though the estimates of HT prevalence and incidence of HT in the U.S. are yet to be completely reliable, evidence and impact of the health outcomes of victims of HT due to their abuse is well established. There is enough research-based knowledge to comprehend the detrimental health outcomes of HT victims’ physical, mental, social, and spiritual3 aspects of their lives, even after they have left their abusive situations (Baldwin, Eisenman, Sayles, Ryan, & Chuang, 2011; Baldwin, Fehrenbacher, & Eisenman, 2015; Greenbaum, 2014; Greenbaum & Crawford-Jakubiak, 2015; Lederer & Wetzel, 2014; Oram, Stöckl, Busza, Howard, & Zimmerman, 2012; Polaris Project, 2018; Raymond & Hughes, 2001; U.S. Department of State, 2017). The consequences of HT victimization extend beyond what can be easily comprehended. Most at-risk victims already are affected by their childhood experiences including abandonment, poverty, and physical and sexual abuse, among others, when entering into their victimization. Their prior and present victimization amounts to a wide range of consequences that, at times, will extend throughout their lifetime (CDC-Division of Violence Prevention, 2014; Greenbaum, 2014, 2016; Reid & Piquero, 2014; Shandro et al., 2016). Researchers have conducted inventories and subsequently compiled lists of different type of abuse experienced by HT victims and the potential health outcomes. The abusive experiences and their potential health outcomes include: a) Psychological/mental abuse – anxiety, depression, suicide, self-harm, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; b) Injuries from physical assault/ abuse – chronic pain and fatigue, poor nutrition, disability, chronic and acute injuries; c) Sexual assault/sex abuse – sexual transmitted infections (STIs), urinary tract infections, changes in menstrual cycle, acute or chronic pain during sex, vaginal injuries, unwanted pregnancies, cervical dysplasia/ cancer; and d) Substance use/misuse – substance addiction and dependence, drug or alcohol overdose, complications from alcohol or drug use. Consequently, victims of HT at times receive medical care and this interaction with the medical care system provides an important opportunity to identify and assist them (Beck et al., 2015; Greenbaum, 2014, 2016; Lederer & Wetzel, 2014; Muftic & Finn, 2013; Shandro et al., 2016)

U.S. Vs. Foreign-Born Victims of Human Trafficking

Given the hidden nature of HT, statistical data on prevalence and incidence of HT range widely depending on the source, there is an estimated 21–35.8 million women, men and children who are victims of HT globally (International Labor Organization, 2014; U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2009; Walk Free Foundation, 2015). The U.S. government’s annual estimates range between 14,500–17,500 relative to foreign-born trafficked persons brought into the U.S. (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2009). These foreign-born victims are commonly found employed as nannies, housekeepers or working at restaurants, factories, farms, beauty salons, hotels, massage parlors, and elderly care facilities (Bales, 2008; Moore & McOwen, 2013; U.S. Department of State, 2010 & 2017). Although foreign-born HT victims enter into the U.S. in the thousands, these numbers are only a small proportion in comparison to the U.S.-born youth, women, and men who become sex trafficked by U.S.-suspects (Estes & Weiner, 2001; U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2009). Given the hidden and clandestine nature of this crime, the numbers are most likely underestimated.

It is commonly assumed that sex trafficking victims within the U.S. are foreign-born; nonetheless, confirmed cases between January 2008-June 2010 through the Human Trafficking Reporting System (HTRS) demonstrate the opposite (U.S. Depart of Justice, 2011). Out of the identified incidents of HT cited in this report (n = 388), fourth-fifths were U.S.-born (83%) and the majority of cases – 8 out of 10 – were sex trafficking. The HTRS works with state and local agents to compile national data. Therefore, these are confirmed identified cases by trained government officials and law enforcement agents. Additionally, the HTRS is the only governmental reporting system in the U.S. that collects, analyzes and identifies HT cases and victims with the intent to bring justice and restitution. Still, the reporting across states is not uniform and it could be argued that U.S.-born victims could be more easily identified than foreign-born. Therefore, continuous efforts to create a reliable and uniform reporting of identified victims of human trafficking within the U. S. continues to be greatly needed.

The Intersection of Human Trafficking with the Healthcare Setting

Scant available literature points out that victims of HT – U.S. and foreign-born – do seek medical care at some point during their victimization period. The Family Violence Prevention (2005) study suggests that at least 28% of foreign-born victims in the U.S. sought medical care during their victimization period. Moreover, Chisolm-Straker et al. (2016) found 62.8% of their study participants (N = 49) who were U.S.-born victims of HT were able to see a doctor during their trauma versus 72.7% (N = 64) of foreign-born. Nonetheless, due to the secret nature of this illegal crime, lack of awareness, training, established identification protocols, and a clear plan of intervention, most victims go regrettably unidentified and unrecognized in the healthcare settings (Baldwin et al., 2011; Chisolm-Straker & Richardson, 2007; Chisolm-Straker, Richardson, & Cossio, 2012; Greenbaum, 2016; Ravi, Pfeiffer, Rosner, & Shea, 2017; Sabella, 2011; U.S. Department of State, 2017). Some studies have also begun to dismantle the most frequented healthcare settings and type of providers who generally encounter victims of sex and labor trafficking. These include: a) Emergency Departments (ED), b) Primary care physicians, c) Dentists, d) Obstetrician-Gynecologist (OB/GYN), and e) Women’s reproductive healthcare clinics such as Planned Parenthood clinics (Baldwin et al., 2011; Chisolm-Straker et al., 2016; Family Violence Prevention Fund, 2005; Ravi et al., 2017).

Furthermore, victims of HT who visit a healthcare setting to attend to their medical needs and emergencies, possess barriers or victim factors when interacting with healthcare professionals and staff members (Recknor, Gemeinhardt, & Selwyn, 2018). Researchers have discovered specific issues that have kept victims – especially labor trafficking foreign-born victims – from disclosing their victimization status with their healthcare provider(s). These victim factors include: 1) Limited ability to speak English 2) Fear of traffickers’ retaliation; 3) Shame; and 4) Distrust. Other barriers are outside the control of HT victims; yet, they play an important role in keeping victim/patients from disclosing their status. Traffickers’ control of the visit, including filling out paperwork and forms prior to the visit, and a lack of privacy during the visit have been specifically noted (Baldwin et al., 2011; Family Violence Prevention Fund, 2005; Lederer & Wetzel, 2014; Shandro et al., 2016; Zimmerman, 2003).

Limited research has been conducted about the experiences of U.S.-born sex trafficking victims in healthcare settings during their period of victimization. When language and legal status are not barriers, what prevents U.S.-born victims of sex trafficking from disclosing and trusting their healthcare providers when interacting with them at some point during their victimization? How is the experience of U.S.-born sex trafficking victims different from that of foreign-born victims in the healthcare setting? These and other research questions require greater inquiry in order to obtain a greater understanding of the plight of both foreign-born and U.S.-born HT victims in the healthcare setting and their experiences when interacting with healthcare providers.

Hence, this study aims to deepen the understanding about U.S.-born sex trafficking survivors and their junction with the healthcare setting during their victimization period. We examine the medical needs that bring victims to healthcare facilities and the barriers that hinder or actions that enhance disclosure of their victimization to their providers. If interventions are supported by the experiences of U.S.-born survivors of sex trafficking, a more comprehensive and patient-centered approach to care could be reached when sex trafficking victims visit and interact with healthcare professionals. Thus, including the voices of survivors in the creation and improvement of identification protocols and daily practices in the healthcare setting is essential. Without the understanding of the interactions of U.S.-born sex trafficking survivors in the healthcare settings, the existing protocols to identify, assess and intervene in the lives of HT victims are incomplete.

Identification Protocols for Human Trafficking Victims in the Healthcare Setting

While some national and local efforts have led to the development of several screening protocols to identify victims in different types of settings, healthcare included, there is still a significant gap in the level of knowledge, skills, and efficacy among healthcare providers (Greenbaum, 2014; Greenbaum & Crawford-Jakubiak, 2015; Ravi et al., 2017; Recknor et al., 2018; Stoklosa, Dawson, Williamns-Oni, & Rothman, 2017; Tracy & Macias-Konstantopoulos, 2017; Vera Institute of Justice, 2014). Recently, a literature review documented the need to establish sound national protocols that are practice-based and trauma-centered. Out of a total of 5,686 hospitals in the U.S., adoption of screening and identification protocols is unknown (Stoklosa et al., 2017). This particular review analyzed a total of 30 protocols used or being developed in U.S.-based hospitals currently. The same study found that a majority of the analyzed protocols (N = 30) pointed to abuse-history indicators, victims’ communication patterns, and signs of dependency on someone else. However, important elements for screening and the identification of HT victims were missing in most of those reviewed. For example, few protocols provided guidance on how to screen an accompanying person of the potential HT victim, and many other studies only focused on certain types of hospitals, or certain types of victims of HT. Stoklosa et al. (2017) concluded there is no one nationally standardized applied protocol that can be utilized and evaluated. Therefore, some of the researchers’ suggestions of an ideal protocol included the following: 1) Evidence and practice-based components; 2) Utilization of a definition of HT based on federal and state laws; 3) Trauma-informed approach to screening and practice; 4) Provision of local resources to victims; and 5) Establishment of an organizational nucleus to identify potential HT victims, among others. Although these are noteworthy recommendations for establishment of a nationally adopted protocol, there is much work to be done to secure the implementation of a national standard for screening and identification of HT victims within healthcare settings. More sex trafficking victims could be aided at their junction with the healthcare setting by increasing awareness of the issue, training health care professionals, adopting effective screening protocols and practices, creating state mandates for training, and linking healthcare providers with social service networks and trained law enforcement agents. Yet, as previously mentioned, if the voices of sex trafficking survivors are missing from the processes that channel establishing protocols and daily practices among healthcare providers, these approaches to aid and assist victims of HT are incomplete.

Purposes and Importance of Study

Insight from survivors of sex trafficking is essential to increase the knowledge and self-efficacy of healthcare providers in identifying potential HT victims in their settings. Consequently, to add to the limited body of research in this area, this study with victims of sex trafficking was designed to empirically delineate: a) where participants sought medical care during their sex trafficking victimization, b) the main reasons for seeking medical care, and c) the barriers that kept them from disclosing their victimization status to the healthcare providers during their medical visit. Comprehending the experiences of survivors of sex trafficking in the U.S. can contribute significantly to enhancing health professionals’ and health care systems’ capacity to reduce human trafficking by identifying key areas of intervention within their daily practice and facilitating detection of victims and their subsequent referral to suitable services.

Methods

Methodology and Framework

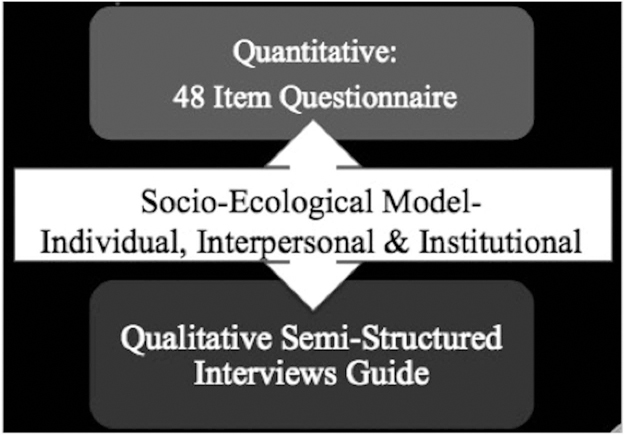

This exploratory study used a concurrent mixed-methods research approach with a triangulation design model (Creswell, Fetters, & Ivankova, 2004). This research methodology utilizes and triangulates both quantitative data (e.g., frequencies and percentages) to describe broader patterns found within a study sample and qualitative data (i.e. narrative accounts) to provide contextualized details as reported by individual participants. Both types of data – qualitative and quantitative – were collected simultaneously (Creswell et al., 2004). The mixed-methods design also permitted the emergence of different dimensions of analysis stemming from the research questions being pursued. Additionally, research design, data collection and analysis was based on the Socio Ecological Model (SEM), which permits the analysis of a complex issue, such as HT (Glanz, Rimer, & Viswanath, 2008). This model is based on different levels of analysis from the intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, community and policy levels. The study utilized the first three levels of this model – individual, interpersonal, and institutional. These three levels were reflected in the instruments utilized to collect data (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Ecological Model components – individual, interpersonal & institutional.

Sampling and Recruitment

This research was based on a convenience sample of study participants meeting the following eligibility criteria (Palinkas et al., 2015): a) Self-identified as Survivor of Sex Trafficking (SST)4 in the geographic boundaries of the U.S.; b) Utilized traditional or non-traditional healthcare services within the U.S. at least once during their victimization period (Chisolm-Straker et al., 2016), preferably within the six years prior to interview (any time after January 1, 2010); c) Were at least 18 years of age; d) Identified as female; e) Were able to read, write, and speak proficiently in English5; and f) Resided in San Diego, CA, Philadelphia, PA, or any of their surrounding metropolitan areas and regions.

The study utilized a geographically diverse recruitment strategy to maximize sample variation. San Diego, CA is a border city and considered a high-risk area for sex trafficking. According to the San Diego County District Attorney (2016), San Diego is the 13th place identified in the U.S. for sex trafficking of minors. Compared to other states in the U.S., California ranks as one of the top four highest in terms of human trafficking cases reported to the National Human Trafficking Hotline. Philadelphia, PA is a transit state with easy interstate highways to Northeast and Mid-Atlantic regions of the U.S. that facilitate human trafficking activity.

Given the hidden nature of study participants, recruitment was accomplished through local organizations led by HT survivors. These organizations included: Project Dawn’s Court, The Valley Against Sex Trafficking (VAST), The Institute to Address the Commercial Sexual Exploitation at Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law, and the Women Organized Against Rape (WOAR), located in Philadelphia and its vicinities; and Freedom From Exploitation, GenerateHope, Hidden Treasures Foundation, Soroptimist International of Vista and North County Inland, Survivors For Solutions, in or around San Diego. These organizations supported the study by reaching out to their network of survivors and other partnering organizations, and informing them of the study and the opportunity to participate. Potential participants subsequently contacted the researcher to initiate a screening process. Relying on survivor-led organizations ensured that those reached included only survivors who were eligible and psychologically ready to share their stories. During the screening process (telephone, email, or face to face), the researcher determined whether a potential participant met the eligibility criteria. An appointment was made with eligible individuals to meet at a location that was convenient to prospective participants. If meeting in person was not possible, researchers followed up to schedule a phone interview. As a result, 24 individuals were screened, 21 met the eligibility criteria.

Protection of Study Participants

All participants received an informed consent form explaining the study’s purpose. Participants were also able to consent verbally in order to increase confidentiality of their identity. If study participants volunteered, they were able to choose not to answer any questions they felt uncomfortable answering. They were also able to stop their participation in the interview at any time if they, or the researcher, felt it necessary. These measures were deemed important to minimize the risk of re-traumatization through their participation in the study.

To protect the identity, privacy, and confidentiality of participants throughout the study, no names or identifying information was collected during the screening or interview process. Pseudonyms were used to protect the identities of participants. Each participant chose her own pseudonym. Each participant’s interview was assigned a unique identifier for analysis purposes that consisted of composite numeric and alphabetic identifiers during data gathering and data entry, e.g., A1, A2, and so on, therefore, there was no identification traceable to the study’s participants. Confidentiality was kept throughout the data collection, data cleaning, analysis, and reporting phases of the study. In addition, a research proposal was submitted and approved by Drexel University’s Institutional Review Board.

Instruments and Measures

The methods utilized in this study were both a questionnaire and semi-structured interviews. The questionnaire contained 48-items and its administration was followed by a qualitative interview. The items used in the quantitative instrument were guided and developed based on the research conducted by Greenbaum (2014, 2016)), Chisolm-Straker et al. (2016) and Stanford Patient Education Research Center (n.d.). The questionnaire sougth to depict: 1) demographic profiles of the study’s participants; 2) type of healthcare setting(s) visited during their victimization period; 3) specific health conditions and/or illnesses that led them to visit a healthcare setting; 4) self-rated health status; and 5) ability to interact with a healthcare provider and barriers for victimization disclosure with said provider. Interviews were conducted face-to-face or over the phone. The administration of the questionnaire and qualitative interview lasted up to 60 minutes in this study.

Participants were read a list of traditional and non-traditional healthcare settings used in previous studies (Baldwin et al., 2011; Chisolm-Straker et al., 2016). Participants could select all visited during their victimization, including: a) Emergency Department, b) Urgent Clinic, c) Dentist, d) Women’s Clinic, e) Mental Health and many more. Healthcare settings were not mutually exclusive. This same type of selection was applied also for the medical conditions for which they sought medical care while being trafficked (Greenbaum, 2014, 2016). Through this descriptive analysis, findings regarding medical reasons were divided into three subcategories: 1) physical injuries.; 2) women’s reproductive health conditions; and 3) mental health conditions.

To measure the overall satisfaction and trust in healthcare providers and services received, two Likert-scales were used. The first Likert-scale sought to gauge overall trust, where “1” meant that study participants did not trust the HCP, and “10” meant they trusted the HCP completely. For the second Likert-scale, participants again rated their overall satisfaction with their healthcare provider by using “1” as signifying “not satisfied at all,” and “10” meaning being completely satisfied. An internal reliability test (i.e. Cronbach’s alpha) was calculated to determine the correlation between these two items as a scale to measure trust and satisfaction among participants. Participants were also asked if they were able to share their victimization status with their healthcare provider and, when unable, what were their perceived barriers for non-disclosure.

The guide for the semi-structured qualitative interview covered similar categories as those included in the quantitative questionnaire, and was developed based on a previous study that focused on the experiences of labor and sex trafficking survivors in Los Angeles, California (Baldwin et al., 2011). The qualitative interview consisted of open-ended questions addressing three broad constructs: 1) reasons for seeking a visit with a healthcare provider reasons that led them to the healthcare setting; 2) perceptions regarding healthcare providers’ competency on quality of care and ability to build trust with the patient; and 3) barriers to victimization status disclosure.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were estimated using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23 (IBM Corporation, 2018) for 1) participants’ socio-demographic characteristics; 2) healthcare settings utilized during victimization; 3) reasons for visiting healthcare settings; 4) perceived trust and overall satisfaction with healthcare providers and their service; 5) disclosure of victimization status during their healthcare visit; 6) perceived barriers for not disclosing victimization; and 7) years of victimization (from less than 1 year to 10 or more years).

Digitally recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim, and Word software files were uploaded into a data management software – NVivo Mac version 11.4.0 (QSR International, Doncaster, Victoria, Australia). Qualitative data was analyzed based on a mixed deductive-inductive thematic approach, which included a two-step process.

The first step was achieved through initial coding by searching for key categories that included: a) type of healthcare setting; b) reasons for accessing medical care; and c) dynamics of interactions with healthcare providers that either encouraged or hindered trafficking victimization disclosure and trust of healthcare providers. The second step was based on refining and expanding upon what was learned through the first-step, including multi-layered complexities derived from the noted categories. Through the second-step process, sub-categories were identified. The analysis was complete when we reached thematic saturation.

Findings

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes social and demographic characteristics of the sample. Although U.S. citizenship was not inclusion criteria, all participants (N = 21) were born in the United States (U.S.). The mean age for the sample was 29.4 years (SD = 8.3); 50% of the sample was older than 27 years of age. In terms of race and ethnic heritage, 47.6% considered themselves White, almost one-quarter self-identified as Black (23.8%), and the remainder self-identified as Biracial and Latina (14.3% each). Two-thirds of the participants (66.7%) reported being single, almost one-quarter were divorced or separated (23.8%), and 9.5% married or living with an unmarried partner. Less than one-half of the participants were currently employed (42.9%). A majority (71.5%) reported having attained a high school diploma or some post-baccalaureate degree. The mean number of reported years of victimization was 4.9 ranging between 1–17. Only two participants reported less than one year of victimization. The mean number of years since participants had exited their victimization was 3.04 and ranged between 1 to 10.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics, duration of victimization and post-victimization (N = 21).

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean (SD) | 29.4 (8.4) |

| Median | 27 |

| Race, ethnicity & geographic location | |

| White | 10 (47.6) |

| Black | 5 (23.8) |

| Biracial | 3 (14.3) |

| Latina | 3 (14.3) |

| Latina, Hispanic or Spanish origin (any race) | 7 (33.3) |

| San Diego, CA | 17 (80.9) |

| Philadelphia, PA | 4 (19.1) |

| Current marital & employment status | |

| Single (never married) | 14 (66.7) |

| Divorced or separated | 5 (23.8) |

| Married or living with unmarried partner | 2 (9.5) |

| Current employment status | |

| Full-or part-time employment | 9 (42.9) |

| Level of education | |

| Associate degree or higher | 3 (14.3) |

| Some college (no degree) | 6 (28.6) |

| High school graduate | 6 (28.6) |

| Less than high school | 6 (28.6) |

| Years of victimization | |

| Mean (SD) | 4.9 (4) |

| Median | 4 |

| Range | 1,18 |

| Years since exited victimization | |

| Mean (SD) | 3.05 (2.55) |

| Median | 2 |

| Range | 1,10 |

Type of Healthcare Settings Accessed during Trafficking

Quantitative Findings

The majority of participants accessed two types of traditional healthcare settings – Emergency Departments (EDs) (76.2%), and community clinics (71.4%) – while being trafficked. Among those who used community clinics, all but one visited a Planned Parenthood clinic. Other healthcare settings accessed by participants included urgent care community clinics (28.6%), mental health clinics or hospitals (23.8%), abortion clinics (19%), private medical practices for general care (14.3%), dental offices (9.5%), OB/GYN clinics (4.8%), and marijuana dispensaries (4.8%) (See Table 2).

Table 2.

Healthcare settings visited during victimization period (N = 21).

| Healthcare settings | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Emergency departments | 16 (76.2) |

| Community clinics | 15 (71.4) |

| Urgent care community clinics | 6 (28.6) |

| Mental health clinic or hospital | 5 (23.8) |

| Clandestine clinic/location | 5 (23.8) |

| Abortion clinics | 4 (19) |

| Private Office for General Care | 3 (14.3) |

| Dental offices | 2 (9.5) |

| Ob/gyn/pregnancy clinics | 1 (4.8) |

| Marijuana dispensary | 1 (4.8) |

Qualitative Findings

Consistent with questionnaire data, most study participants recounted frequenting general hospitals’ EDs and community clinics during their victimization period. Participants also described Planned Parenthood clinics as the most familiar and helpful setting when seeking healthcare during their victimization period. Planned Parenthood free-of-charge services were the main motivator for frequent visits. Beverly, a 24-year-old Black woman who survived eight years of sex trafficking, shared the following:

I visited Planned Parenthood very often. …I went there simply because being in the lifestyle [prostitution] for a long time, I was without certain things. And Planned Parenthood offers their own like private insurance to where you can get services free of cost even if you do not have insurance. So, that really helped me….

Interviews also revealed participants visited non-traditional settings. A few of the respondents were taken to a clandestine location, including the trafficker’s home. There, care was provided by a medical doctor, or someone pretending to be one, at times, the captor himself, or a healer – Voodoo type. Nontraditional settings also included privately owned pharmacies. Owners of these settings allowed the traffickers to bring the victims to be routinely checked or treated for specific medical needs in the back of the pharmacy. Leaf, a 40-year-old Latina, who survived 18 years of victimization under the control of different traffickers shared:

He [trafficker] had a friend, a person with a pharmacy, that would give us our Depo shots [Depo-Provera birth control] in a needle. And he would give them to us in our butts.

Medical Reasons for Seeking Medical Attention

Quantitative Findings

The most common reasons for medical visits included sexual/reproductive health concerns, physical injuries, mental health/substance abuse emergencies, and chronic health conditions (See Table 3). The majority of participants (81%) reported having sought care to address their reproductive/sexual health needs. More than half (61.9%) sought medical care for sexually transmitted infections (STI), including regular check-ups to ensure they were free of infections. A sizable fraction (38.1%) visited healthcare facilities for birth control purposes. Pelvic pain as a reason for medical visits was reported by one-third (33.3%). About a quarter of participants (23.8%) sought care for pregnancy-related conditions, and 19% visited healthcare providers for abortions. Additionally, one participant sought care to treat a urinary-tract infection (UTI), and another received treatment for a sustained injury from having a foreign object inserted into her vagina.

Table 3.

Medical reasons for visiting healthcare settings (N = 21).

| Medical reason | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Reproductive/sexual health concerns | 17 (81.0) |

| Sexually transmitted infections | 13 (61.9) |

| Birth control | 8 (38.1) |

| Pelvic pain | 7 (33.3) |

| Pregnancy (tests or visits) | 5 (23.8) |

| Abortion | 4 (19.0) |

| Other | 2 (9.5) |

| Physical injuries | 12 (57.1) |

| Intentional injuries (punched, stabbed, kicked burned) | 11 (52.4) |

| Sexual assault injuries (rape, John’s aggression) | 6 (28.6) |

| Fractures (broken arm or jaw) | 4 (19.0) |

| Dental injuries (broken teeth) | 3 (14.3) |

| Accidental injuries | 1 (4.8) |

| Mental health/substance abuse | 10 (47.6) |

| Depression | 8 (38.1) |

| Anxiety/panic attacks | 6 (28.6) |

| Feeling suicidal | 4 (19.0) |

| Substance abuse | 2 (9.5) |

| Manic episode | 1 (4.8) |

| Chronic health conditions | 6 (28.6) |

| Chronic pain (back pain, all over pain) | 6 (28.6) |

| Gastrointestinal problems (stomach pain, diarrhea) | 1 (4.8) |

More than one-half of the participants (57.1%) visited a medical care setting due to physical injuries, including intentional injuries (being punched, stabbed, kicked, or burned) (52.4%), injuries due to sexual assault (28.6%), battery-related fractures (19.0%), and dental injuries (14.3%). An accidental injury as a reason for medical visit was reported by only one participant.

Visiting healthcare providers for mental health conditions was reported by 47.6% of participants. More than one-third sought care for their depression (38.1%), and 28.6% were treated for anxiety at some point during their victimization period. Other reasons for visiting mental health facilities included suicidal ideation (19%), drug or alcohol abuse emergency (9.5%), and a manic episode (4.8%). Additionally, less than one-third (28.6%) visited healthcare providers because of chronic health conditions, including chronic pain (28.6%) and gastrointestinal conditions (4.8%)

Qualitative Findings

Physical Injuries.

Physical injuries typically caused by traffickers included: intentional violence, rape, or exposing women to risky situations that jeopardized their safety. Redd, a 27-year-old, biracial, part-time college student, who survived six years of victimization under her traffickers, was pushed down the stairs and suffered several facial fractures. She commented:

I went to [name of hospital #1] first ‘cause, mmm, I’ve gotten beat up [by trafficker]. My jaw and eye were hurting really bad. … I was spitting blood and I thought I was dying or something. …I couldn’t open my eye so I was ‘Something is wrong’. So I went to [name of hospital #2], and they were like, ‘Oh my god, we don’t know how you’re still walking!”… My jaw was shattered, … I had a fracture on one side and I had three fractures on the eye socket.

Ann, a 38-year-old White participant who survived three years being victimized by her trafficker, commented on circumstances surrounding her visit to an emergency department [ED]:

We [Ann and trafficker] were at the East Street trolley, the trolley stop right over there. We got into a fight. I don’t even remember what it was about… he wanted me to get in the car. I was pretty much done with him. I was like, ‘No, I’m done.’. He hauled back and punched me in my jaw, right here [pointing at her jaw]. I heard it snap. Then, the cop came up, and he [the trafficker] went running. Then, I got on the trolley. I went down to 8th Street, and I used the pay phone to call one of my friends to take me to the hospital.

Valery, a 28-year-old, White, college-student who survived 10 years being victimized by her trafficker, shared about the reasons and location where she tended to her needs:

It was many situations where I went to the hospital…There were times where they [sex buyers] would get me to like… They’d like to kidnap you or rape you and not give you the money.

Adilyn, a 21-year-old White woman who survived five years of victimization under different sex traffickers, reflected on an intentional injury from being hit by her trafficker’s car. Adilyn narrated:

Well, I went to St. Mary’s [ED] because I needed to go in mmm because he [the trafficker] had hit me with his car. I was having, like, I wasn’t able to eat because I had been hit in the stomach. And, mmm, it hurt to eat so I wasn’t eating. And, first of all, he didn’t feed me at all anyways, hardly ever, I should say. So they took me in, and I was, like, I was going in and out of being conscious. So, they brought me in, and they gave me an IV.

Leaf, spoke about her risky and dangerous situation that led to her injury that continues to mark her current health status and medical conditions. Leaf shared:

And the person I got into the car with was a date [sex buyer], and we were supposed to be going to the hotel. But, he kept making different turns, and he was making me very nervous. So, at one point, he sped up, and I had to make a choice. And, the choice that I made was to jump out of the car. When I jumped out of the car, I injured my leg. My whole leg was scrapped very badly and I fractured my leg and my elbow also. Mmm, I went with my trafficker to the emergency room.

Hillary, a 27-year-old Latina who survived eight years of victimization, experienced battery from her sex buyers. On one occasion, her trafficker stopped the physical and sexual abuse perpetrated by her client and another individual that was not supposed to be part of the exchange. She explained her experience as follows:

You know Johndo [sex buyer], ended up being abusive. My trafficker barged into the room and stopped him because that wasn’t part of the deal. You usually discuss it beforehand, but that was unexpected. …There was another guy that was in the room, and I didn’t know that there were two people in the room. …And they tried to do both at the same time. But, they got abusive before my trafficker ran in and took me away… They were big. …I was being dragged. I was being thrown around like I was nothing!

Other times, study participants visited a hospital’s ED due to their neglected medical needs, which eventually became medical emergencies. Some participants emphasized the fact that if it were not a medical emergency that kept them from working, they would typically not tend to their medical needs given that their priority was to make money for the trafficker. Felicia, a 32-year-old survivor of three years of victimization, commented:

I did go to the Emergency Room because I got bit by a spider, but that had gone on for weeks, upon weeks, upon weeks to the point I was super sick from it. And then, I finally got to go. Like, I had to work! Do you know what I mean? That was his [trafficker’s] priority! It’s making the money the priority, all the hours and everything.

Reproductive/Sexual Health Needs.

Participants commented on reproductive and sexual health concerns addressed in healthcare settings. Those concerns included staying free of STIs, having access to birth control and abortions, as well as reproductive or sexual health emergencies. Beverly commented about her sexual and reproductive health visits at Planned Parenthood:

Oh, I’ve gone for routine check-ups. Like every 4–5 months, I would go to do STI and STD screening. They were always pretty expedient about the process, and I would go for pregnancy tests. And, I always went for my Depo-Provera shot.

Ann also commented on the reasons why she frequented her local Planned Parenthood clinic. She stated:

Got birth control. So, I wouldn’t get pregnant. I had my abortions when..They changed my birth control because one wasn’t working because of my blood or whatever. So, I couldn’t take the pill. I had to take a different kind of pill. Then, I got the shot. So, the stuff that they said would be done, was done. They made sure that they kept checking me for STDs. I didn’t end up pregnant again.

At times, study participants accessed a local health clinic to have a brief check-up to ensure they were STI-free or when they were experiencing symptoms of potential infections. Hillary stated:

No, it was just a local little clinic. You walk into the [clinic] if you wanted to get STI, pregnancy test or UTIs, like basic, little things. You know basic little ones.

Participants also shared circumstances surrounding urgent visits related to sexual or reproductive health concerns. Wisdom, a 25-year-old biracial single-mother, who survived four years of abuse under her traffickers, shared her reason for getting an abortion at a Planned Parenthood facility:

I was dealing with a lot with the situation I was in…my living situation, and not having anyone. And then, I felt like if I kept the baby, I would be keeping the person [trafficker]…and that I didn’t want to do I guess…because it was not a good situation. …just had to go and get that abortion to… get freed.

Amy narrated her experience related to another reproductive health emergency:

I was with a trafficker. I had told him that I had started my period. He made a suggestion of putting a sponge instead a tampon inside of my vagina. This way, it would stop the bleeding, and I can still see Johns [sex buyers]. After telling him ‘no’ and refusing by telling him that it wouldn’t come out and it would get stuck. … He ended up forcing me to put the sponge in. He put it in himself. I had it in for probably two days. It started to smell because I couldn’t get it out. So, I told him, ‘It is not coming out. It is starting to smell. Now, what do we do?’ He tried to do it himself.… he laid me on the bathroom floor and tried to get it out himself. He wasn’t able to. At that time, … he took me to the medical office. He gave me my ID and my insurance card. That was all I had on me.

Mental Health/Substance Abuse Visits.

Study participants spoke about their experiences in mental health care settings, and reasons for their visits. Alice, a 25-year-old, single White survivor who to this day suffers anguish due to her trafficking experience, shared about her experiences when she visited a mental health hospital in San Diego, California. She stated:

I remember going to the [name of the ED], and they transferred me to a behavioral health center. I went there because I was stressed. You know…like a lot of fear. And, I was going into a manic episode. So…they [ED] couldn’t really like identify what was going on with me. They didn’t know I had a lot of fears and things. So, they just transferred me to behavioral health [hospital]. That’s where I was able to talk more to a doctor in private and open up about what had happened to me. And, they were able to give me a medication to calm down…

Rose shared about her visit to a psychiatrist,

“… I went to the psychiatrist starting…I don’t know…2010–2011, for major anxiety. And, I told him what I was doing. And, he just prescribed me an anti-psychotic.”

In this case, it is evident that her psychiatrist was unable to provide suitable mental health services given what she had shared during her healthcare visit. Amy also spoke of her needs for medical care attention, and that her parents needed to take her because her trafficker would not. Amy said6:

Besides that, whenever I could go to get mental health, a lot of times it was my parents would come pick me up. They would take me home. I would have to go to their house before I got any kind of mental health, doctor’s appointments and things like that. My trafficker wouldn’t take me.

Rachel spoke about her experience in a drug-rehabilitation center and her previous drug dependency, which led her to her sex-trafficking victimization. She shared:

I had an opioid dependence prior to my being a victim of trafficking. And me being homeless and completely dependent on the opioid led me to being forced by a trafficker to work for him since he supplied the drugs. And that led me, eventually, when I was so disgusted and fed up with everything that was going on, that eventually led me to seek out services to get into a rehab center working on my mental health, and hoping to get my opioid dependence taken care of, and to get away from him at the same time.

Barriers to Accessing Healthcare during Victimization

Quantitative Findings

Participants were also asked to recall barriers faced during their victimization when trying to access needed medical care. These barriers were then sub-divided into General Barriers and Trafficker’s Oppressive Tactics Barriers. Under the General Barriers, almost one-half of the participants stated lacking health insurance (42.9%) was a key barrier to access needed healthcare. Additionally, the following were experienced by a minority of the participants (14.3%): not having access to specific services, lack of knowledge of where to go, and previously having a negative experience with a healthcare provider. Transportation was identified as a barrier by almost one-tenth of the participants (9.5%) (See Table 4). Under Trafficker’s Oppressive Tactics Barriers, the most frequently experienced factor was: being forced to work long hours (76.2%), and “being forced not to seek care” (61.9%). A majority also identified “moving constantly from city to city” (57.1%) as a barrier, which impeded them from seeking medical attention. Fear, the perception of potentially negative consequences derived from opening up about their status, was a significant barrier experienced by almost one-third of participants (28.6%). The least frequently perceived barriers, clustered under the rubric of Trafficker’s Oppressive Tactics Barriers, included: being locked up/not allowed to go outside (9.5%), and having a trafficker who did not believe [victim] was sick (9.5%)

Table 4.

Barriers to accessing medical care during trafficking (N = 21).

| Barriers | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| General | No insurance | 9 (42.9) |

| No access to specific services | 3 (14.3) | |

| Lack of knowledge where to go | 3 (14.3) | |

| Previously had negative experience with providers | 3 (14.3) | |

| Lack of transportation | 2 (9.5) | |

| Trafficker-related | Forced to work long hours | 16 (76.2) |

| Forced not to seek care | 13 (61.9) | |

| Moved constantly from city to city | 12(57.1) | |

| Fear of disclosure | 6 (28.6) | |

| Locked up/Not allowed going outside | 2 (9.5) | |

| Trafficker’s lack of belief she was sick | 1 (4.8) | |

| Fear of abuse | 1 (4.8) | |

Lack of Trust

Quantitative Findings

Two Likert-scales were used to capture the participants’ perception of trust and satisfaction when visiting a healthcare setting during their period of victimization. These items were summed up resulting in a final score ranging between 2–20, with higher scores representing higher levels of satisfaction and trust with an HCP.

The participants exhibited low trust in healthcare providers overall (the mean was 5.3 out of 20, SD = 2.1), and average satisfaction with healthcare services (Mean = 10.95, SD = 4.18).

Overall, only slightly more than one-third of the participants disclosed their victimization status to a healthcare provider (38.1%). Table 5 identifies barriers to victimization disclosure reported by participants. Two main reasons for not disclosing victimization status included “felt too ashamed and embarrassed” (52.4%), and “no one asked me questions about my situation (47.6%). Additionally, one-third were “too afraid about what the trafficker would do to them or family” (33.3%) and almost 1 out of 4 indicated that there was “little privacy in the setting to share information” (23.8.%). One-fifth also indicated that “there was no time, and that that the appointment was too rushed” (19.0%), “did not want to talk about it” (19.0%), and “wanted to talk about it, but trafficker was there at all times” (19.0.%). A minority perceived the following barriers: “wanted to talk about it, but did not trust healthcare provider” (14.3%), and “other reasons” (9.5%), including the fact that the trafficker was waiting outside the healthcare setting, as well as not knowing how the HCP would react to their circumstances.

Table 5.

Perceived barriers to disclosure of victimization status (N = 21).

| Perceived barriers | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Internal | Felt too ashamed and embarrassed | 11 (52.4) |

| Did not want to talk about it | 4 (19.0) | |

| Trafficker-related | Too afraid about what the trafficker would do to me or family | 7 (33.3) |

| Wanted to talk about it, but trafficker was there at all time | 4 (19.0) | |

| Trafficker was outside waiting for me | 1 (4.8) | |

| Provider-related | No one asked me questions about my situation | 10 (47.6) |

| There was little privacy in the setting to share my information | 5 (23.8) | |

| There was no time, the appointment was too rushed | 4 (19.0) | |

| Wanted to talk about it, but did not trust healthcare provider | 3 (14.3) | |

| I didn’t know how the healthcare provider was going to respond | 1 (4.8) | |

Barriers to Disclosure of Trafficking Status

Qualitative Findings

Qualitative findings speak to a diversity of barriers to victimization disclosure, including, a lack of privacy in healthcare settings, lack of competency or professionalism from healthcare providers in recognizing signs of sex trafficking victimization, traffickers’ strategies for control, and fear of law enforcement involvement.

Lack of Privacy.

Some study participants shared that the healthcare setting did not induce a private conversation with providers due to a lack of built-in private consultation rooms. Lack of privacy also took other forms. For some participants, it meant that their confidential patient information was shared, or they heard of some other patients’ information being shared among HCPs in an unprofessional manner. On other occasions, a lack of privacy was related to the traffickers’ strategy for control while overshadowing the victim everywhere she went, including medical visits. When reflecting on the built-in environment, participants noted that a lack of privacy was linked to having only a curtain that divided them from other patients, or the overcrowding in a Planned Parenthood clinic where there were too many patients in one room waiting to have an abortion. Therefore, information was often shared in front of others. Ashley, a 22-year-old White college student who survived almost a year of victimization shared her experiences with ED,

When I was first admitted, they were friendly, but kind of in a rush because there were a lot of people. It was in LA [Los Angeles, CA] and there were lots of people being admitted to the hospital. And, when I got admitted, they kind of just rushed me into a room, and I was sharing one [room] with another girl, but there was only a little curtain separating us.

Wisdom spoke of her experience at a Planned Parenthood clinic, stating:

Well, they [clinic staff] did say it was confidential and stuff like that [but] there was people around. There were patients and stuff..We were all in the same room in the back. And they would grab one and take them into the procedure room, and put them back in the other room. Nothing was confidential.

Another issue involving privacy was the lack of professionalism exhibited by the HCP in keeping patients’ information private, or talking about patients in places where staff could be overheard. Hillary commented:

But the one reproductive health clinic in Oregon, I never went back to [the particular clinic] after that. Because when I was being directed to my room, I overheard the assistants or nurses.. I heard them talking about patients that were in the other rooms.… They were calling her names. They were calling her inappropriate names and saying like, ‘You’d think she’d get on birth control with all…with all these positive tests.’ You know or ‘Wrap it up, or put a condom on’ or something like that. And, ‘She gets tested a lot.’ So, it was really annoying, and it upset me.

Sometimes, medical staff made the patient’s private medical history available to other providers without the patient’s knowledge or permission. Amy experienced shock after finding that information about the removal of a foreign object from her vagina–during a medical visit that took place in a different city–was shared with her current psychologist within her healthcare network. Although she understood that this situation occurred within the same healthcare network, she never thought her reproductive healthcare visit’s details could have been shared with her psychologist, who subsequently pointed this out to her to gain more context. Hence, Amy felt she could not trust her HCPs within this healthcare network. Amy commented:

I was seeing…a psychologist.. He had brought up the fact that in their computer system that it had shown that I had a foreign object in my body. This was probably a year, maybe a year and a half, after this had happened. He had brought it up. I was too scared to say anything again. This is the same doctor [psychologist] that my dad sees. Maybe, he would say something to my dad…my biological father. I just wasn’t sure what to say. He didn’t really ask me other questions about the sex trafficking or anything illegal going on. He just wanted to know why I had done it. I told him that I was on my period, but that was it. I felt like I had no privacy. I mean, he is my psychologist, he can look at the notes and everything. I wish more of an OB/GYN doctor maybe would have brought that up. … I was too scared to say anything!

Amy’s interaction with her psychologist also reaffirms that victims of sex trafficking, at times, may have access to mental health providers. This suggests that there is a potential window for being identified and assessed during one’s period of victimization, including accessing much needed services.

Traffickers’ Control Strategies.

Study participants shared strategies their traffickers used to control victims’ intake and treatment to prevent the disclosure of abuse during health care encounters. The trafficker was either physically present during the medical visit to control the information shared, what medications the victim would receive, or they would wait outside the healthcare setting to ensure victims would not escape. Ann, reflected about her trafficker always coming with her to regular STIs or birth control check-ups at the local Planned Parenthood clinic, where he befriended the clinic’s medical staff. He took different victims throughout the year for check-ups. He would lie about his relationship with them, stating that he was their cousin, boyfriend, friend, etc. Ann typified her trafficker’s control strategies in the context of her interview:

I went to Planned Parenthood. I went there a lot for birth control [to the same clinic]. He [trafficker] took all his girls there. They knew him by Benny, but they didn’t know who he was. He just kept saying that they were sisters or friends. He wasn’t like, ‘Oh, this is my girlfriend. This is my girlfriend. This is my girlfriend.’ He would just say, ‘This is my sister. This is my friend. This is my cousin.’ That was how he would be able to get a lot of different people in and not get questioned about it. …Whenever any of us went, he went with us. [Trafficker would refuse to go outside even if asked by healthcare providers] He was like, ‘Naw, I’m good. I want to make sure that you treat her right’ kind of thing. They didn’t make him. They would just say, ‘Are you okay with him being here?’ The answer is always, ‘Yeah.’

When Ashley tended to her medical needs in an ED, her trafficker also was there. She recounted:

They had to take a lot of blood and had to see a radiologist. And so they had to do lot of that. So he [Trafficker] was in, he was kind of in and out … for that hmmm so when the healthcare provider …the doctor was in there, he, my trafficker, was in the same room as me.

Just like in the case of Ann, Jazzy, a 24-year-old biracial – Black Latina who survived six years of her traffickers’ brutality, commented on the lack of privacy she experienced at a Planned Parenthood clinic:

I’m just filling out the paperwork and I’m waiting until I get called. And he’s going to go in with me [trafficker]. And I told him, ‘I don’t think they are going to let you go in there’, you know? And he was like, ‘Well, OK. We are going to figure that out. I’m not going to leave you out of my sight.’ Like, you know, ‘what do they [traffickers] think you are going to do? Go in there with the doctor and never come out?’ you know. And I was really nervous. I was like, ‘Oh wow’… you know what I mean? No type of privacy or anything. He’s on edge all the time, you know?

Even when traffickers were not physically present during the actual medical visit, they waited outside the healthcare facility or in the waiting room. These tactics instilled fear and hindered victims’ likelihood to reach out to HCPs for assistance or disclosure of their victimization status. Adilyn’s case exemplifies this strategy.

Interviewer: Was there anything else that kept you from reaching out at other settings that you visited?

Adilyn: Just the fear of him possibly knowing that I told. Like, that fear is so huge. Specially, when he’s in the same building. …And, he doesn’t even have to be in the same room. … he’s going to find out.

On other occasions, the trafficker sent someone else with the patient/victim. This would often be a person who assisted the trafficker in managing victims as well as ensuring their control – Rule Enforcers, as Adily called them. In Felicia’s case, her trafficker would send another female to ensure the victim did not say anything outside what she was supposed to say, or try to escape. Felicia recollected:

Well, every time I had to go to the doctor for anything, it would be my Wify [the woman who assists trafficker to enforce rules]. She would go with me – one of the other girls, you know? …You don’t know if the girl is going to leave! You don’t know if they are going to say something, and then get help and go. And that’s just to keep the situation under control and the intimidation factor there.

Adilyn’s case was different from the majority of the study participants in that she at one point communicated with her healthcare provider that she needed help. She needed someone to assist her escape the inhumane treatment and abuse of her trafficker(s). She reached out to the ED’s nurse who was attending to her, hoping she would listen to her cry of help. However, due to the trafficker’s strategies to divert her victim’s attempts to reach out, in addition to limited knowledge, training, and identification protocols, the providers missed or ignored Adilyn’s call for help. She shared the following:

I was trying to get the nurse to understand that I needed help, and she just didn’t listen to me. … So, I wrote that I needed help…that I didn’t feel safe. And, she [nurse] thought that I didn’t feel safe because I was suicidal. Because, that’s what my lady [trafficker’s assistant] had told the nurse. She [nurse] wouldn’t listen to me. …I asked for some paper and a pencil. At first, the other…the lady [trafficker’s assistant]…she was like, ‘Don’t give her any. She doesn’t need that right now. What she needs is some sleep.’ And, the other lady [nurse] was like, ‘Well, she’s asking for some. So, we’re going to give her some. She seems to be doing okay right now.’ And, the nurse went and got me a piece of paper and a pencil. And, I wrote that I needed help. And, that’s all I wrote because I thought they’d help me. And, they…they were like, ‘Oh, we’re getting you some help. We’re going to help you, and this lady [trafficker’s assistant] is going to take you back home. And, she’s going to take care of you.’ And, they [healthcare provider] just wouldn’t listen to me. ….Then the doctor came in and asked if everything was okay, and how’s everything going-and stuff like that. Then, I was trying to talk, but the other lady [trafficker’s assistant], she kept on talking. Like, she talked over me. So, I wasn’t able to talk [to the doctor].

In this participant’s case, not only is the lack of knowledge and training necessary to potentially identify a sex trafficking victim self-evident, so too is the lack of privacy, and presence of the trafficker’s assistant always controlling the interaction. Thus, traffickers’ strategies constitute barriers for the patient/victim to receive both care, privacy, and help.

Another strategy of control was instilling fear through physical, mental, or emotional abuse. Threats were a major instrument to minimize the likelihood that victims would reach out for assistance while at healthcare settings. Survivors spoke about the constant threatening behavior of their perpetrators as a means to control victims’ behavior and actions. Threats were also extended to victims’ children or other family members. Valery’s story exemplified her trafficker’s threats:

He’s threatened my family before, my daughter, and me. At one point, I’ve been through so much, I just didn’t care. So, he ended up threatening my family because he started to see that I didn’t care anymore. So, he started threatening my family and my daughter specifically and that changes things. You do exactly what they say for your kids, or at least I do.

At times, traffickers would also threaten victims by blackmailing them. Hillary shared about this particular issue:

‘I have pictures of you that I can’, you know, inappropriate [ones], very visual pictures. ‘And, I can always go and hurt you’ you know? This trafficker didn’t know about my family, but one of my…my first trafficker did. And, later down the road, he ended up finding me, and I had to pay a debt.

Lack of Empathy, Judgmental Attitudes and Missing Red Flags.

Patient-provider encounters and interactions are crucial in encouraging victims to share their victimization status. A judgmental attitude or negative encounter with a healthcare provider is likely to impact the possibility that victims will want to disclose their victimization status when they interact with healthcare providers in the future. Additionally, their hope of being assisted by a health professional is likely to diminish. Perceptions suggesting a lack of empathy and genuine care as well as a mechanical approach to caring for the patient often result in victims of sex trafficking lacking trust or developing a hopeless attitude towards members of the medical community, or the belief that they will offer any assistance. Lack of empathy, not genuine care, and a mechanical approach to treating patients leave victims with no desire to return to that particular medical office and provider for their future medical needs. In addition, HT victims cannot really trust service providers when they feel judged, or when they perceive their attitude is negative towards them. Alexandra, a 27-year-old Black woman who survived five years under the oppression of her trafficker(s), spoke about the facial expressions of her HCP, and how she felt judged based on what she shared about her victimization experience. She shared:

…I mean by the face because I go by people’s facial expressions. So I mean, maybe, they [the healthcare providers] were disgusted. That’s how I felt. I mean, I’m not sure how others would feel about that situation. That’s how I felt at the time [during medical encounters].

Although Alexandra’s conversation with the healthcare provider ended on a positive note, this was not the case for other participants. Redd was very disappointed by how a nurse asked her to leave the ED while waiting for a friend to pick her up. She had just escaped with her daughter from her trafficker, and had no money to return to San Diego, CA. The nurse in the early shift had shown more empathy towards her situation, but the second one did not. Redd became disappointed about the nurse’s capacity to be compassionate. Redd recounted:

She [the first nurse] was just so nice [first nurse]! She was saying, ‘Don’t worry, just stay here as long as you want.’ She fed me. She was, ‘Do you need anything, do you need help?’ I was, ‘No’, And the end of her shift, she left. She left at twelve [midnight]. She said, ‘I am leaving, I am gonna tell the other nurse your situation’ right? The other nurse [second nurse] was waking me up at 1 o’clock in the morning; like, ‘If you are not going to be here [checked-in], you need to leave.’ I am like, ‘Yeah, the other nurse told me it was OK. I need a couple of hours of sleep like. I know I’ve been here for four hours. Look, I am gonna leave in the morning.’ She was like, ‘Well, this is not a place for you to sleep.’ She was like, ‘You need to leave!’ She called security. … They were like, ‘We are not a homeless shelter.’ Like being rude as hell! ‘till I was finally like, ‘Shit’ [and I left]. It was 3:00 o’clock in the morning. It was cold as hell. I had no money; no where to go. And, it’s like stuff like that, that makes me be like, ‘they [healthcare providers] have no compassion.’

Stephanie, shared similar experiences. Due to her trafficker’s abuse, she ended up in an ED with stomach pain and broken ribs. She did not have a place to go and did not want to return to her trafficker, but was not allowed to wait in the ED until someone could pick her up. The providers in the ED told a security guard to make her leave. “You can’t sleep here,” a security guard told her.

In the case of Adilyn, she could not trust the providers due to their attitude towards her.

It wasn’t the actual setting. The actual setting was actually very private, and it was nice. It was their attitude and how they treated me. And, I didn’t feel like I could even trust them at all,

she explained. Felicia felt she was treated differently by the providers when she visited an ED or clinics. Felicia recounted,

So I feel like the medical professionals treated us differently because we come in with no insurance, you know what I mean? We are dressed a little risqué or don’t have the best of clothes on. So they just look and treat you differently, a little bit like more of a trashier-type of clientele.

Many other participants felt that the treatment received at the different healthcare facilities was mechanical and monotonous and lacking concern. Beverly stated:

I think if I was to tell them [healthcare providers], it wouldn’t matter. Do you know what I mean? I guess you can say that’s them not being competent, or I just didn’t think they would actually do anything about it. … It was just like, ‘Click, click, click, click. Alright. Alright. B or C.’ You know what I mean? … it was coming to a point like, ‘Okay, how many partners have you been with? Oh, 400 in the past ten months. Okay, how much do you weigh? Okay. Okay, the doctor will be here to see you.’

Fear of Police Involvement.

Sex trafficking survivors not only spoke about their fear about what could happen if they did not follow the rules the trafficker imposed on them, but also their reticence relative to law enforcement involvement of any kind. Hillary was tired of her abusers. Nonetheless, her HCPs were not able to assist her due to their lack of knowledge and the absence of protocols. She shared:

I tried one time saying something [about her HT situation], and they [providers] did not know what to do. They automatically tried to call the police. And, I told them that it was a waste of time…I was like, ‘I want to get out of this life. I don’t want to be on the road with these people.’ But, they [providers] didn’t know what to do. They were kind of like, ‘We don’t have like regulations on how to do this step-by-step.’ And, their first instinct was to call the police, and I was like, ‘That should be your last thing.’ …I was like, ‘That may just get me in more trouble. …The police can make up everything. They can make false documents and go after my family. Or, they can go pick up mutual friends, and just you know get them in jail for something, you know?’…I was like, ‘You know what? Forget it. I didn’t say anything…” And, I walked out.

Hillary’s case exposes the fear of police involvement as well as the providers’ lack of knowledge and training and their inability to assist her.

Like Hillary, other participants would not trust the healthcare providers because of the fear of police involvement, and not really knowing what the provider would do after they shared their situation. Felicia explained:

…I would never share that [her victimization] with the healthcare provider – like anything that I’m going through or trust them ‘cause you don’t know if they are going to turn you into the police. You don’t know if they are going to get you help. You don’t know any of that because you are scared! When you live The Life you are scared that they are going to take you to jail as the victim, you know what I mean? Because it’s against the law to be a prostitute. So you don’t talk about it because you are scared to go to jail yourself.

As this study demonstrates, U.S.-born survivors of sex trafficking while being victimized, visited healthcare settings to attend to medical emergencies. They not only faced environmental barriers within healthcare institutions, such as a lack of privacy in the ED, or a lack of awareness and training from the part of the healthcare providers; they also faced their own barriers – including fear and distrust. Traffickers crafted strategies of control by inflicting pain and fear so victims would not disclose their victimization status and attempt to escape their exploitation. Moreover, a lack of awareness, the absence of identification protocols, privacy, or compassionate care were key barriers in building trust between the patient and her provider(s). Visiting the ED or any other healthcare settings while trafficked results from the trauma and the commercial sexual exploitation experienced by victims. Yet, sex trafficking victims faced diverse barriers that kept them from disclosing their victimization status with providers when visiting medical settings (See Table 6).

Table 6.

Barriers to victimization disclosure.

| Barrier | Exemplary quote |

|---|---|

| Victims: Fears of Abuser’s Threats | ‘I have pictures of you that I can’, you know, inappropriate [ones], very visual pictures. And, I can always go and hurt you’ you know? This trafficker didn’t know about my family, but one of my… my first trafficker did. And, later down the road, he ended up finding me, and I had to pay a debt. |

| Traffickers: Control at healthcare settings | I’m just filling out the paperwork and I’m waiting until I get called. And mmm he’s going to go in with me [trafficker]. And I told him, ‘I don’t think they are going to let you go in there’, you know? And he was like, ‘Well, OK. We are going to figure that out. I’m not going to leave you out of my sight.’ Like, you know, ‘what do they [traffickers] think you are going to do? Go in there with the doctor and never come out?’ you know. And I was really nervous. I was like, ‘Oh wow’… you know what I mean? No type of privacy or anything. He’s on edge all the time, you know? |

| Providers: Lack of privacy | Well, they [clinic staff] did say it was confidential and stuff like that [but] there was people around. There were patients and stuff..We were all in the same room in the back. And they would grab one and take them into the procedure room, and put them back in the other room. Nothing was confidential. |