Abstract

Glycyrrhizic acid (GL) is a major active compound of licorice. The specific monoclonal antibody (MAb) (designated as 8F8A8H42H7) against GL was produced with the immunogen GL–BSA conjugate. The dissociation constant (K d) value of the MAb was approximately 9.96×10−10 M. The cross reactivity of the MAb with glycyrrhetic acid was approximately 2.6%. The conventional indirect competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (icELISA) and simplified icELISA adapted with a modified procedure were established using the MAb. The IC50 value and the detect range by the conventional icELISA were 1.1 ng mL−1 and 0.2–5.1 ng mL−1, respectively. The IC50 value and the detect range by the simplified icELISA were 5.3 ng mL−1 and 1.2–23.8 ng mL−1, respectively. The two icELISA formats were used to analyze GL contents in the roots of wild licorice and different parts of cultivated licorice (Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch). The results obtained with the two icELISAs agreed well with those of the HPLC analysis. The correlation coefficient was more than 0.98 between HPLC and the two icELISAs. The two icELISAs were shown to be appropriate, simple, and effective for the quality control of raw licorice root materials.

Keywords: Glycyrrhizic acid, Monoclonal antibody, ELISA, Licorice

Introduction

Licorice root has been a herbal medicine in China for over a thousand years. It is commonly used in Chinese herbal medicines (CHMs) and Chinese proprietary medicines (CPMs). Glycyrrhizic acid (GL) (Fig. 1a) is a major active compound and a quality control marker of licorice root. It has anti-viral [1, 2], anti-inflammatory [3], anti-carcinogenesis [4, 5], anti-hepatitis [6–8], anti-thrombotic [9], and immunomodulatory [10] activities. Its antiviral activity against severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-associated coronavirus has recently been demonstrated in vitro [11, 12]. GL is also used as food additive and masking agent in pharmaceutical products because of its sweet taste (170 times sweeter than sucrose) [13].

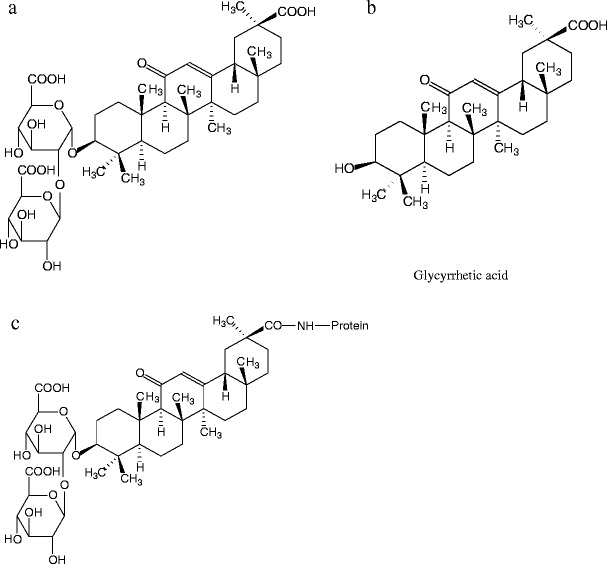

Fig. 1.

Structures of glycyrrhizic acid (a), glycyrrhetinic acid (b), and the hypothetical glycyrrhizic acid–BSA conjugate (c)

The content of GL in the licorice roots varies considerably with strains, cultivars, growing regions, climatic conditions, and harvest age. The quality of the raw herbs used in the CPMs affects the final therapeutic outcomes and consumer safety. An effective method is needed to screen large numbers of licorice root samples for the quality control. Existing methods for the determination of GL include high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [14, 15], liquid chromatography–ion trap mass spectrometry (LC-ITMS) [16], capillary electrophoresis [17], near-infrared spectroscopy [18], immunosensor [19], immunoassay [13, 20–22], and micellar electrokinetic chromatography [23]. Compared to conventional instrumental methods, immunoassay is a rapid and sensitive method which needs small quantities of test materials and simple pretreatments. There are reports of ELISAs based on monoclonal antibody (MAb) against GL [13, 24]. The MAb was obtained from GL–BSA synthesized by the NaIO4 method. The ELISA reported by Mizutani et al. [13] had a detect range of 20–200 ng mL−1. Here, we report a new ultra-sensitive and specific immunoassay by using a new GL MAb. A conventional indirect competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (icELISA) and a simplified icELISA were developed for the determination of GL in different licorice samples.

Materials and methods

Reagents and apparatus

Glycyrrhizic acid (99% purity) and glycyrrhetic acid (99% purity) were purchased from Tauto Biotech Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Cell culture media (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, DMEM) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were obtained from Gibco BRL (PaisLey, Scotland). Reagents purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA) were cell freezing medium—DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide) (serum-free), hypoxanthine, aminopterin, and thymidine (HAT), hypoxanthine and thymidine (HT) medium supplements, L-glutamine, penicillin, streptomycin, goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (GAM–HRP), complete and incomplete Freund’s adjuvant, N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC), bovine serum albumin (BSA), ovalbumin (OVA), and o-phenylenediamine (OPD). Poly(ethene glycol) (PEG)-2000 was purchased from Fluka (Buchs, Switzerland). Methanol and acetic acid of chromatography gradient grade were purchased from Fisher Scientific (New Jersey, USA). All other chemicals used were of analytical grade.

Cell culture plates and 96-well polystyrene microtiter plates were purchased form Costar (Corning, NY, USA). An automated plate washer (Wellwash 4 MK2), a microplate reader (Multiskan MK3), and direct heat CO2 incubator were purchased from Thermo (Vantaa, Finland). Syringe filters (25 mm, 0.2 μm, and 0.45 μm pore size, Acrodisc) and filter unit (Acrocap) were purchased from Pall (Ann Arbor, USA). An electric heating constant-temperature incubator was purchased from Tianjin Zhonghuan Experiment Electric Stove Co. Ltd. (Tianjin, China).

Buffers and solutions

The following solutions were used: (i) coating buffer (0.05 M carbonate buffer, pH 9.6); (ii) phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (0.1 M phosphate buffer containing 0.9% NaCl, pH 7.5); (iii) PBS with 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20 (PBST); (iv) PBST containing 0.5% (w/v) gelatin (PBSTG); (v) citrate-phosphate buffer (0.01 M citric acid and 0.03 M Na2HPO4, pH 5.5); (vi) substrate solution (4 μL of 30% H2O2 added to 10 mL citrate-phosphate buffer containing 2 mg mL−1 OPD); and (vii) a stop solution (2 M H2SO4).

Preparation of immunogen and coating antigen

GL–BSA and GL–OVA conjugates were prepared via the active ester method as an immunogen and coating antigen, respectively. DCC (150 mg) was added to a stirring mixture of GL (80 mg) and NHS (40 mg) in 3 mL DMF (N,N-dimethylformamide). The mixture was stirred for 4 h at 4 °C and centrifuged. The supernatant was added dropwise to protein solution (150 mg BSA or OVA in 12 mL carbonate buffer, 50 mM, pH 9.6), and the solution was stirred overnight at 4 °C. The reaction mixture was dialyzed against five changes of PBS for 5 days and stored lyophilized at −20 °C. The hapten density in the GL–BSA was determined by UV spectroscopy. The hapten to BSA molar ratio was 5:1.

Production and characteristics of MAb against GL

Five Balb/c female mice (6–7 weeks old) were injected subcutaneously with 0.1 mg GL–BSA conjugate dissolved in 0.1 mL PBS mixed with 0.1 mL Freund’s complete adjuvant. Two subsequent injections were carried out at 1-week intervals using Freund’s incomplete adjuvant. One week after the third injections, mice were eye-bled and sera were tested for anti-GL antibody titer and for GL recognition properties in icELISA. Three days after the last injection in adjuvant, mouse with the highest titer and best specificity was boosted intraperitoneally with 0.1 mg GL–BSA conjugate in 0.1 mL PBS and was used for the fusion. The spleen cells collected from the mouse were fused with the SP2/0 (obtained from China Institute of Veterinary Drug Control, Beijing, China) cell line using PEG-2000 at a ratio of 10:1 of spleen to myeloma cells. The plates were incubated at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator (5% CO2 in air). Selective growth of the hybrid cells in the DMEM supplemented with HAT. Seven days after fusion, the supernatant was tested by icELISA. Positive hybridomas were cloned by limiting dilution and clones were further selected by icELISA.

The clone, designated as 8F8A8H42H7, having a high antibody titer and good sensitivity in the culture supernatant was expanded in mice for production of MAb in ascites. The antibody was purified by ammonium sulfate precipitation followed by affinity chromatography on a HiTrap Protein G HP affinity column (HiTrap, Amersham, USA). The immunoglobulin isotype was determined with a mouse antibody isotyping kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). The assay cross-reactivity with glycyrrhetic acid (Fig. 1b) and the affinity of MAb 8F8A8H42H7 to GL were determined with the conventional icELISA.

Establishment of conventional icELISA

In all the procedures, microtiter plates were washed on an automated plate washer with 250 μL PBS or PBST per well for four times. A microtiter plate was first coated with 200 μL hapten–OVA in coating buffer per well for 3 h at 37 °C. After four washes with PBS, each well was blocked with 200 μL 3% non-fat dry milk in PBS for 30 min at 37 °C. After the plate was washed with PBST, 100 μL aliquots of various concentrations of the standard in PBSTG were pipetted into each well followed by addition of 100 μL sera, supernatant, or purified MAb solution diluted in PBSTG. The plate was then incubated for 0.5 h at 37 °C. The unbound antibody was removed by washing the plates four times with PBST, and then 200 μL goat anti-mouse IgG–peroxidase conjugate in PBSTG was added to each well followed by incubation at 37°C for 0.5 h. After the plate was washed with PBST again, 200 μL substrate solution per well was added. The reaction was stopped by adding 100 μL 2 M H2SO4 per well. Absorbance was read at 492 nm in the microplate reader.

Establishment of simplified icELISA

The washing step and the buffers used in the simplified icELISA were the same as that of the conventional icELISA. Briefly, a microtiter plate was first coated with 200 μL hapten–OVA per well for 3 h at 37 °C. Each well was blocked with 200 μL 3% non-fat dry milk in PBS for 0.5 h at 37 °C. After the plate had been washed with PBST, 20 μL of the standard in PBSTG was pipetted into each well followed by the addition of 90 μL goat anti-mouse IgG–peroxidase conjugate and 90 μL purified MAb solution in PBSTG. The plate was then incubated for 0.5 h at 37 °C. The substrate solution was added at 200 μL per well followed by the addition of 100 μL 2 M H2SO4 to stop the reaction. Absorbance was read at 492 nm on the microplate reader.

Preparation and extraction of samples

The root samples of Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch were collected to a maximum depth of 91 cm. The above-ground caudex and leaflets of the cultivated licorice were collected. All samples were air-dried before being finely powdered.

The samples were extracted by the method of Shan et al. [22]. The sample of root, caudex, and leaflets materials (10 mg) was extracted with 1 mL methanol under sonication for five times and centrifuged at 7,000 g for 2 min. The supernatant was collected and transferred into a 50 mL volumetric flask. The distilled water was added up to a total of 50 mL to provide the real sample stock solution. The solution was divided into two equal aliquots. One aliquot was detected in the conventional and simplified icELISA after dilution with distilled water. The dilution ratio was 5,000 and 500 for the conventional icELISA and simplified icELISA, respectively. The other aliquot was lyophilized. The resultant residue was dissolved in 0.5 mL of a mixture of methanol/30% acetic acid/water (73:5:22, v/v/v), i.e., the mobile phase, and filtered with a Millipore membrane. The filtered solution was used for analysis by HPLC.

HPLC analysis [25]

The HPLC apparatus consisted of a Waters (Milford, MA, USA) 600E multisolvent delivery system and a Waters 2487 dual λ absorbance detector. All modules and data collection were controlled by Waters Millennium32 software. The analytical column was a Zorbax (Agilent Technologies, Massy, France) SB-C18 (150×4.6 mm i.d.; 5 μm). The mobile phase was filtered through Millipore nylon filters and degassed by sonication (SB5200, Branson, Shanghai, China) prior to use. Separations were carried out at ambient temperature with a flow rate of 1 mL min−1 and a 20 μL injection loop. Quantitative analyses were carried out at a wavelength of 254 nm.

Results

Characteristics of monoclonal antibody

The titer (the serum dilution that gave an absorbance of 1.0 in the noncompetitive assay conditions) of the ascites was 2–4×104. The dissociation constant (K d) of the MAb (designated as 8F8A8H42H7) was determined with the method of Bertrand et al. [26]. The K d value was 9.96×10−10 M. The MAb is a IgG1 isotype that has λ light chains.

Optimization of conventional icELISA and simplified icELISA

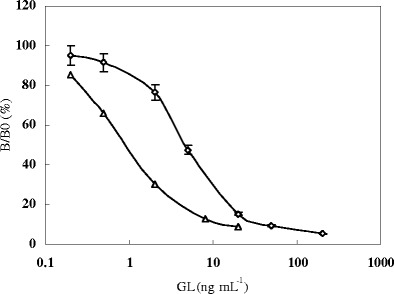

Two icELISA formats were optimized. The coating antigen (0.5 mg mL−1), purified MAb (2.0 mg mL−1), and anti-mouse IgG–peroxidase conjugate (1 mg mL−1) were at a dilution ratio of 1:2,000, 1:4,000, and 1:1,000 and 1:1,000, 1:1,000, and 1:250 for the conventional icELISA and the simplified icELISA, respectively. The inhibit curves of the conventional icELISA and simplified icELISA (Fig. 2) were established. The IC50 values were 1.1 ng mL−1 and 5.3 ng mL−1, and the detection ranges were 0.2–5.1 ng mL−1 and 1.2–23.8 ng mL−1 for the conventional icELISA and simplified icELISA, respectively. MAb 8F8A8H42H7 in the conventional icELISA format had a low cross reactivity (2.6%) with glycyrrhetic acid.

Fig. 2.

Inhibit curve of glycyrrhizic acid with the conventional icELISA (△) and the simplified icELISA (◊). B 0 and B are OD in the absence and presence of glycyrrhizic acid, respectively

Analysis of GL in licorice samples with the two icELISAs and HPLC

Ten licorice samples were analyzed with the conventional icELISA, simplified icELISA, and HPLC (Table 1). The results obtained from icELISAs agreed well with those obtained from the HPLC analysis. The correlation coefficients were 0.9844 (y = 0.9612x + 0.1498) between HPLC and the conventional icELISA and 0.9983 (y = 1.0368x−0.0918) between HPLC and the simplified icELISA. There was no significant difference among the results obtained from the three methods for each sample.

Table 1.

Analysis on content of glycyrrhetinic acid (%) in wild and cultivated licorice and different parts in cultivar with icELISA and HPLC (the same letter indicates no difference at p = 0.05)

| Samplesa | Conventional icELISAb | Simplified icELISAb | HPLCb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild strain | 3.784 ± 0.302 a | 3.761 ± 1.143 a | 3.647 ± 0.066 a |

| Five-year-old cultivar | 3.035 ± 0.146 a | 2.936 ± 0.151 a | 2.979 ± 0.027 a |

| Four-year-old cultivar | 2.546 ± 0.236 a | 2.551 ± 0.235 a | 2.587 ± 0.016 a |

| Three-year-old cultivar | 1.761 ± 0.213 a | 1.771 ± 0.211 a | 1.798 ± 0.030 a |

| Two-year-old cultivar | 1.549 ± 0.329 a | 1.561 ± 0.326 a | 1.585 ± 0.019 a |

| One-year-old cultivar | 0.552 ± 0.113 a | 0.546 ± 0.113 a | 0.594 ± 0.081 a |

| Above-ground caudex of five-year-old cultivar | 0.090 ± 0.008 a | 0.093 ± 0.014 a | – |

| Above-ground caudex of one-year-old cultivar | 0.056 ± 0.007 a | 0.059 ± 0.008 a | – |

| Leaflet of five-year-old cultivar | 0.071 ± 0.018 a | 0.074 ± 0.014 a | – |

| Leaflet of one-year-old cultivar | 0.053 ± 0.012 a | 0.051 ± 0.007 a | – |

aAll the samples were Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch

bData are given as the means±standard deviations; mean of six determinations

The GL content in various licorice roots differs considerably and is higher in the roots of wild strains than in cultivated licorice. The GL content in licorice roots generally increases as the growth age prolongs within the five-year life with which our results agree. The above-ground caudex and leaflets contained too low levels of GL to be detectable in HPLC.

Discussion

Glycyrrhizic acid is a marker of quality for Glycyrrhiza materials. Mizutani et al. [13] reported a MAb-based ELISA for the analysis of GL. The immunogen was synthesized by the NaIO4 method. The polysaccharide residue in the glucuronic acid molecules is specifically oxidized at adjacent hydroxyl residues leaving reactive aldehyde groups. Reductive animation proceeds between the aldehyde group(s) and free amino group(s) of the protein. In our study, the MAb was derived with an immunogen (GL–BSA) conjugated by the active ester method. The two new icELISAs are approximately 20- to 100-fold more sensitive than that reported by Mizutani et al. [13]. The results showed that our immunogen evoked a high-quality antibody against GL.

Three of four hybrid clones which secreted anti-GL MAb in the previous report showed more than 18% cross reactivity with glycyrrhetinic acid [22], whereas, MAb 8F8A8H42H7 showed only 2.6% cross reactivity. In general, there is some correlation between the position in the hapten molecule used for the conjugation to carrier protein and the recognition of epitopes on the hapten by the prepared antibodies. The epitopes distant from the site of conjugation tend to be well recognized by antibodies, whereas epitopes neighboring the coupling site tend to be less well recognized [27]. There are three carboxyl groups in the GL molecule. Thus, it is proposed that the carboxyl group in its aglycon, but not the carboxyl groups in the two glucuronic acid molecules, was connected with the free amino group on the carrier protein (Fig. 1c). However, the hypothesis needs further study to be verified.

Conclusions

The two icELISAs can be used to control the quality of raw licorice materials. The results obtained from the two icELISAs were in a good agreement with those from the HPLC analysis. The advantages of the icELISAs over the HPLC method are mainly that they are rapid, sensitive, cost-effective, and allow large sample throughput. However, the simplified icELISA consumes more reagents such as coating antigen and goat anti-mouse IgG–peroxidase than the conventional icELISA.

The GL content varied remarkably in different licorice samples. The different quality of crude licorice roots used in CPMs surely results in inconsistency of the clinical effectiveness. The analysis data indicated wild and 3- to 5-year-old cultivated licorice roots possess higher quality than 1- to 2-year-old cultivated licorice roots. In China, farmers usually harvest 3-year-old licorice roots. Our results suggest that the cultivation system is reasonable.

References

- 1.Takei M, Kobayashi M, Li XD, Pollard RB. Pathobiology. 2005;72:117–123. doi: 10.1159/000084114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crance JM, Scaramozzino N, Jouan A, Garin D. Antivir Res. 2003;58:73–79. doi: 10.1016/S0166-3542(02)00185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsui S, Matsumoto H, Sonoda Y, Ando K, Aizu-Yokota E, Sato T, Kasahara T. Int Immunopharmacol. 2004;4:1633–1644. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malagoli M, Castelli M, Baggio A, Cermelli C, Garuti L, Rossi T. Phytother Res. 1998;12:s95–s97. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1573(1998)12:1+<S95::AID-PTR262>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lo HH, Yen YS, Hsieh SE, Chung JG. J Appl Toxicol. 1997;17(6):385–390. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1263(199711/12)17:6<385::AID-JAT455>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujioka T, Kondou T, Fukuhara A, Tounou S, Mine M, Mataki N, Hanada K, Ozaka M, Mitani K, Nakaya T, Iwai T, Miyakawa H. Hepatol Res. 2003;26:10–14. doi: 10.1016/S1386-6346(02)00332-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Rossum TGJ, Vulto AG, De Man RA, Brouwer JT, Schalm SW. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:199–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamamura Y, Kotaki H, Tanaka N, Aikawa T, Sawada Y, Iga T. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1997;18(8):717–725. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-081X(199711)18:8<717::AID-BDD54>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendes-Silva W, Assafim M, Ruta B, Monteiro RQ, Guimaraes JA, Zingali RB. Thromb Res. 2003;112:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raphael TJ, Kuttan G. Phytomedicine. 2003;10(6/7):483–489. doi: 10.1078/094471103322331421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu Z, Ohtaki Y, Kai K, Sasano T, Shimauchi H, Yokochi T, Takada H, Sugawara S, Kumagai K, Endo Y. Int Immnuopharmacol. 2005;5:571–580. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cinatl J, Morgenstern B, Bauer G, Chandra P, Rabenau H, Doerr HW. Lancet. 2003;361:2045–2046. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13615-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mizutani K, Kuramoto T, Tamura Y, Ohtake N, Doi S, Nakaura M, Tanaka O. Biotechnol Biochem. 1994;58(3):554–555. doi: 10.1271/bbb.58.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sabbioni C, Ferranti A, Bugamelli F, Forti GC, Raggi MA. Phytochem Anal. 2006;17:25–31. doi: 10.1002/pca.877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuan X, Koh HL, Chui WK. J Pharmaceut Biomed. 2005;39:697–704. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2005.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jong TT, Lee MR, Chiang YC, Chiang ST. J Pharmaceut Biomed. 2006;40:472–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2005.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabbioni C, Mandrioli R, Ferranti A, Bugamelli F, Saracino MA, Forti GC, Fanali S, Raggi MA. J Chromatogr A. 2005;1081:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Y, Sorensen LK. Fresenius J Anal Chem. 2000;367:491–496. doi: 10.1007/s002160000356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakai T, Shinahara K, Torimaru A, Tanaka H, Shoyama Y, Matsumoto K. Anal Sci. 2004;20:279–283. doi: 10.2116/analsci.20.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Putalun W, Tanaka H, Shoyama Y. Phytochem Anal. 2005;16:370–374. doi: 10.1002/pca.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morinaga O, Fujino A, Tanaka H. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2005;383(4):668–672. doi: 10.1007/s00216-005-0054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shan S, Tanaka H, Shoyama Y. Anal Chem. 2001;73:5784–5790. doi: 10.1021/ac0106997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang P, Li SFY, Lee HK. J Chromatogr A. 1998;811:219–224. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(98)00279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanaka H, Shoyama Y. Biol Pharm Bull. 1998;21(12):1391–1393. doi: 10.1248/bpb.21.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pharmacopoeia Commission of People’s Republic of China . Pharmacopoeia of People’s Republic of China, vol 1. Beijing: Chemical Industry press; 2000. pp. 65–66. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bertrand F, Alain FC, Lisa DO. J Immunol Methods. 1985;77:305–319. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(85)90044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knox JP, Beale MH, Butcher GW, MacMillan J. Planta. 1987;170:86–91. doi: 10.1007/BF00392384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]