Abstract

An increasing number of critically ill patients are immunocompromised. Acute hypoxemic respiratory failure (ARF), chiefly due to pulmonary infection, is the leading reason for ICU admission. Identifying the cause of ARF increases the chances of survival, but may be extremely challenging, as the underlying disease, treatments, and infection combine to create complex clinical pictures. In addition, there may be more than one infectious agent, and the pulmonary manifestations may be related to both infectious and non-infectious insults. Clinically or microbiologically documented bacterial pneumonia accounts for one-third of cases of ARF in immunocompromised patients. Early antibiotic therapy is recommended but decreases the chances of identifying the causative organism(s) to about 50%. Viruses are the second most common cause of severe respiratory infections. Positive tests for a virus in respiratory samples do not necessarily indicate a role for the virus in the current acute illness. Invasive fungal infections (Aspergillus, Mucorales, and Pneumocystis jirovecii) account for about 15% of severe respiratory infections, whereas parasites rarely cause severe acute infections in immunocompromised patients. This review focuses on the diagnosis of severe respiratory infections in immunocompromised patients. Special attention is given to newly validated diagnostic tests designed to be used on non-invasive samples or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and capable of increasing the likelihood of an early etiological diagnosis.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00134-019-05906-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Pneumocystis pneumonia, Influenza, Aspergillosis, Mucormycosis, Toxoplasmosis, Cytomegalovirus

Take-home message

| Appropriate diagnosis of respiratory infections is crucial to improve survival of critically ill immunocompromised with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. Diagnostic strategy relies on a series of clinical and radiographic elements available at the bedside on the use of non-invasive sampling, thanks to innovative tests, and sometimes on bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage. |

Introduction

The proportion of critically ill patients with deficient immune systems has risen in recent years to about a third of all ICU admissions. Immunocompromised patients include patients receiving long-term (> 3 months) or high-dose (> 0.5 mg/kg/day) steroids or other immunosuppressant drugs, solid-organ transplant recipients, patients with solid tumor requiring chemotherapy in the last 5 years or with hematological malignancy whatever the time since diagnosis and received treatments, and patients with primary immune deficiency. Patients with AIDS are discussed in another manuscript from this issue. Factors contributing to this trend include the increased aggressiveness and duration of cancer treatments [1], greater use of organ and hematopoietic cell transplantation, and introduction for the treatment of autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases of steroid-sparing agents that induce specific immune defects. Thus, a large number of patients are now expected to live for many years with immune deficiencies that put them at risk for severe infections.

Severe respiratory infection is the leading reason for intensive care unit (ICU) admission in immunocompromised patients, who are at risk for hypoxemic acute respiratory failure (ARF) and sepsis [2]. Life-supporting interventions must be implemented at the same time as extensive investigations are conducted to identify the cause of the pulmonary involvement [2]. Failure to identify the etiology of ARF is associated with a higher risk of dying [3]. Moreover, identifying a pathogen is crucial for antimicrobial stewardship in immunocompromised patients. However, the etiological diagnosis can be extremely challenging, as the effects of the infection combine with those of the underlying disease and treatments to create extraordinarily complex clinical pictures. In addition, some patients have more than one concurrent infection, and others have non-infectious causes of ARF that mimic infection. Furthermore, fiberoptic bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage (FOB/BAL) are commonly used for diagnosis, but may cause further respiratory deterioration in patients with hypoxemia [4]. The development of non-invasive diagnostic tests with high sensitivity and specificity (e.g., on blood, plasma, sputum, urine, or nasal swabs) has obviated the need for FOB/BAL in some patients [5, 6]. The utility of these non-invasive tests is being evaluated, and will hopefully provide clinicians with additional tools in the diagnosis of these complex patients.

In this review, we summarize contemporary literature and clinical practice guidelines regarding diagnostic testing for severe respiratory infections in immunocompromised critically ill patients. Additionally, we briefly discuss ongoing research, treatments, and outcomes.

Literature search strategy

We searched PubMed and the Cochrane database for relevant articles published between 1998 and 2019 using “humans” and “English language” as filters. The main search terms were “respiratory infection” OR “pneumonia” OR “opportunistic infection” OR “bacterial infection” OR “fungal infection” OR “viral infection” OR “parasitic infection”. The additional search terms were “immunocompromised” OR “cancer” OR “transplants” OR “steroids” OR “immunosuppressive drugs” to identify publications about the epidemiology, outcomes, and diagnosis of acute respiratory failure; and “ICU” OR “intensive care” OR “critical care” OR “critical illness” to retrieve publications about the ICU management of immunocompromised patients with ARF. Additional articles were identified by Internet searches using the same terms.

General considerations

ARF in an immunocompromised patient may be due to infection by more than one viral, bacterial, fungal, or parasitic agent [7]. In addition, non-infectious factors may contribute to cause ARF and should be sought routinely. These factors, which are not discussed in this review, include radiation, drug-related pulmonary toxicity, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, pulmonary edema, and lung lesions due to the underlying disease (e.g., leukemic infiltrates, engraftment syndrome, GVHD, lymphangitic carcinomatosis, and pulmonary vasculitis).

Existing guidelines for managing lung disease in critically ill immunocompromised patients emphasize the importance of obtaining valid diagnostic samples [8]. However, antimicrobial therapy is often started immediately, before samples are collected. As a result, causative pathogens are identified in only about half the patients with bacterial pneumonia. A detailed analysis of the clinical, laboratory, and imaging-study findings can provide valuable diagnostic orientation in these cases. Nevertheless, the frequency of bacterial pneumonia is probably underestimated as many cases are atypical and, therefore, escape recognition. On the other hand, non-infectious pulmonary abnormalities may be mistakenly diagnosed as clinically documented infections.

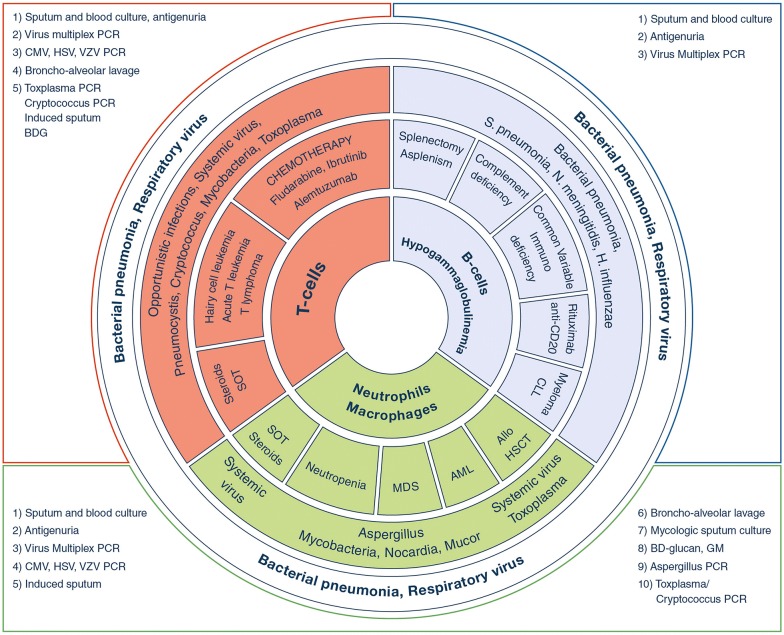

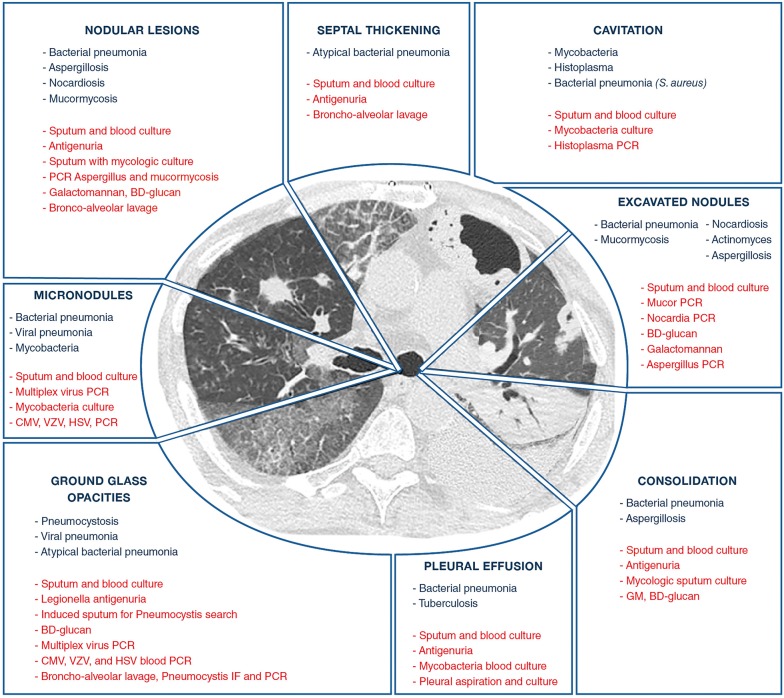

The basic rules shown in Table 1 provide helpful guidance for determining the cause of pulmonary infiltrates and selecting the appropriate diagnostic strategy. In immunocompromised patients with ARF, the first step in the etiological evaluation is a clinical assessment. We advocate the use of the mnemonic DIRECT (Table 2) based on days since respiratory symptom onset, type of immunodeficiency (Fig. 1), radiographic pattern, experience of the assessing clinician, clinical findings, and high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) findings (Fig. 2) [2, 9, 10]. Most of these variables are easily evaluated at the bedside, and their analysis usually restricts the number of possible etiologies to two or three. Additional invasive and non-invasive investigations should be obtained as needed [5]. The diagnostic strategy should be tailored to the pretest probability of the disease being sought, which governs the diagnostic yield. Importantly, the indications of FOB/BAL are changing to avoid exposing patients to potential adverse events (Table 1). When FOB/BAL is considered as mandatory, it should be performed under optimal monitoring and high-flow oxygen therapy should be used to correct hypoxemia [11]. The risk for intubation should be assessed carefully as it is associated with higher mortality. The introduction of non-invasive tests, notably those based on next-generation sequencing (NGS), transcriptomics, and proteomics, may reduce the need for FOB/BAL [12–16]. Updated research is needed, however, to determine their exact diagnostic yield in critically ill immunocompromised patients with hypoxemic ARF. Diagnostic performance of BAL should be reported in specific case vignettes (ARF with bilateral ground-glass opacities in an organ transplant recipient as opposed to ill-defined alveolar consolidation in neutropenic patients with febrile ARF), or in specific ARF etiologies (bacterial infections as opposed to invasive fungal infections), or when patients are suspected to have ARF from either an infectious or a non-infectious origin (i.e., drug-related pulmonary toxicity, pulmonary infiltration from the underlying disease, etc.).

Table 1.

General considerations for the diagnosis of hypoxemic acute respiratory failure (ARF) in immunocompromised patients

| 1. | Diagnostic tests should be selected based on a clinical assessment of the most likely cause(s) of ARF. This assessment relies on the clinical and radiological presentation and on the nature of the underlying condition |

| 2. | A clinical suspicion for a given diagnosis must be confirmed by the most appropriate diagnostic strategy. A differential diagnosis should always be considered and assessed as appropriate |

| 3. | All immunocompromised patients with suspected respiratory infection should undergo a minimal diagnostic workup that must include a chest X ray, standard blood tests (blood cell counts, electrolytes, renal function test, liver enzymes, LDH level, and hemostasis parameters), blood cultures, sputum examination for bacteria, echocardiography, urine bacterial antigens, and viral PCRs on nasal swabs or nasopharyngeal aspirates |

| 4. | When diagnostic yields are similar non-invasive diagnostic tests should be preferred over fiberoptic bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (FOB/BAL) |

| 5. | A positive test is not necessarily diagnostic (false-positives, colonization) |

| 6. | A negative test is sometimes diagnostic |

| 7. | When the initial evaluation suggests that a disease is unlikely, a test with a high negative predictive value should be preferred |

| 8. | When the initial evaluation suggests that a disease is likely, a test with high sensitivity should be preferred |

| 9. | When selecting the diagnostic strategy, the risk/benefit ratio must be assessed. FOB/BAL should be reserved for situations in which this approach has a high diagnostic yield (organ transplantation, associated HIV infection, systemic inflammatory joint disease, high probability of Pneumocystis pneumonia, diffuse ground-glass opacities) and discouraged in other situation (patients with malignancies, neutropenia, alveolar consolidations, or bronchial/bronchiolar disease) |

| 10. | Patients with respiratory distress and/or severe hypoxemia are at risk for respiratory deterioration following FOB/BAL. Non-invasive tests should be preferred. If FOB/BAL is indicated by the bedside physicians, high-flow nasal oxygen should be considered. Whether patients should be intubated for the procedure questions about the risk/ratio benefit and remains unsure for the authors |

Table 2.

The DIRECT approach to acute respiratory failure in immunocompromised patients

| D. Delay: time since respiratory symptoms onset, since antibiotic prophylaxis or treatment, since transplantation, since the diagnosis of malignancy or inflammatory disease |

| I. Immune deficiency: nature of immune defects and ongoing antibiotic prophylaxis will help avoid missing opportunistic infections |

| R. Radiographic appearance: A chest radiograph will not only report the extent and the patterns of pulmonary infiltrates (consolidation, air bronchogram, nodules, interstitial pattern), but also presence and importance of pleural effusion, mediastinal mass, cardiomegaly, pericarditis, etc |

| E. Experience: the clinical experience of the ICU team and specialists consultants with this type of patients (treatment-related toxicity, viral reactivation, atypical form of diseases, cardiac involvement, etc.) |

| C. Clinical picture: the presence of shock is likely to be associated with bacterial infection, but may be seen in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, toxoplasmosis, adenoviral infections, or HHV6 reactivations. Similarly, absence of fever or presence of tumoral syndrome (liver, spleen, and lymph nodes) will be considered as a possible orientation |

| CT scan provides a better description of the radiographic patterns and guides the diagnostic strategy towards non-invasive or invasive diagnostic tests |

Fig. 1.

Pulmonary infections according to immunosuppression. AML acute myeloid leukemia, CMV cytomegalovirus, GM galactomannan, HSCT hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation, HSV herpes simplex virus, MDS myelodysplastic syndrome, PCR polymerase in chain reaction, SOT solid organ transplantation, VZV Varicella–Zoster virus

Fig. 2.

Etiologies of pulmonary infections according to CT-scan patterns. CMV cytomegalovirus, GM galactomannan, HSV herpes simplex virus, MDS myelodysplastic syndrome, IF immunofluorescence, PCR polymerase in chain reaction, VZV Varicella–Zoster virus

Bacterial pneumonia

Bacterial pneumonia accounts for about 30% of ICU admissions in cancer patients [7]. Depending on the type of immunosuppression, the incidence rate varies from 5% after chemotherapy for lung cancer to 30% after remission–induction chemotherapy for acute leukemia [17, 18]. The incidence rate is 30% after lung transplantation, 10% after heart or liver transplantation, and 5% after renal transplantation [19, 20]. Splenectomy also increases the relative risk for developing pneumonia, more particularly for encapsulated bacteria. Pneumococcal, Meningococcal, and Haemophilus influenzae vaccinations are indicated for patients after splenectomy.

All types of immunosuppression are risk factors for classic bacterial pneumonia, and 1 out of 5 patients hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is immunocompromised [21]. Long-term steroid therapy (> 10 mg/day of prednisone-equivalent for ≥ 3 months) is the main cause of immunosuppression. Neutropenia is also associated with a higher risk of bacterial pneumonia, notably when profound and prolonged (neutrophils < 100/µL for > 7 days). About 10% of critically ill cancer patients with severe pneumonia have neutropenia [22]. Lymphopenia is also associated with an increased risk of pneumonia [23]. Humoral immunosuppression and hypogammaglobulinemia are risk factors for bacterial pneumonia, especially with Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae [24]. In addition to immunosuppression, patients may have other factors associated with both bacterial pneumonia and Pseudomonas pneumonia, such as structural lung disease [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or bronchiectasis], diabetes mellitus, smoking, and alcohol abuse [21].

Specific risk factors have been reported for pneumonia due to Nocardia, Neisseria, Rhodococcus, and Q fever (Coxiella burnetii). Nocardiosis is associated with hematological and solid malignancies, high-dose steroid therapy, and TNFα antagonist therapy [25]. Risk factors for N. meningitidis infection are nasopharyngeal carriage and complement deficiencies [26]. Rhodococcus pneumonia has been reported in recipients of hematopoietic stem cells or solid organs [27]. Legionella has been described in cancer patients, as well as those taking systemic corticosteroids or biologic therapies [28, 29].

Bacterial pneumonia should be considered in patients presenting with nonspecific symptoms (e.g., cough, dyspnea, fever, sputum production, and pleuritic chest pain) and pulmonary infiltrates. However, the symptoms are often blunted in patients with immune deficiencies [30]. Bacterial pneumonia may be complicated by septic shock and/or acute respiratory distress syndrome. Chest radiographs and HRCT findings are not specific and include lobar consolidation, alveolar or interstitial infiltrates, cavitation, and/or pleural effusion [31]. Extra-pulmonary manifestations suggest infection with Legionella or Nocardia. Nocardia can disseminate to the bloodstream, skin, bones, joints, retina, heart, and/or central nervous system.

Streptococcus pneumoniae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Haemophilus spp. are the most frequently identified causative pathogens [21]. Pseudomonas spp., enteric Gram-negative bacilli, Stenotrophomonas spp., and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus should be considered [32]. Multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens are significantly more common in immunocompromised patients; in one study, they were responsible for 72% of ventilator-associated lower respiratory tract infections [33]. Data are scarce on Mycoplasma, Legionella, and Chlamydia species in this population.

Routine non-invasive tests for bacterial pneumonia include sputum sampling, blood cultures, and urine antigen detection. The sputum Gram stain is rarely informative, and the yield of sputum bacterial cultures is low, although it improves with optimal sampling and absence of prior antibiotic therapy. Endotracheal aspirates are more likely to recover the causative organism than expectorated sputum, and organisms recovered immediately after intubation is unlikely to reflect mere colonization; in patients with malignancies and ARF, a randomized-controlled trial reported that a strategy with non-invasive testing only (including sputum sampling) was not inferior to FOB/BAL [5]. In patients admitted for CAP, urine antigen detection was 61% sensitive and 39% specific for S. pneumoniae, and corresponding values for L. pneumophila were 63% and 35% [34]. Blood cultures also have low yields of 5–14% in patients admitted for CAP [5, 35], although higher yields have been reported when the pulmonary involvement was severe. Bacterial identification by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on respiratory samples has been reported to provide up to 81% sensitivity and may be superior over standard culturing in patients with CAP, especially those previously given antibiotics [36]. The diagnostic yield of pleural fluid cultures is about 35%, but can reach 60% when blood culture bottles are used [37].

The diagnosis of nocardiosis requires specific culture media and PCR. N. meningitidis infection is diagnosed based on blood and cerebrospinal fluid culture. Rhodococcus grows readily on ordinary media. Serological testing is the cornerstone of the diagnosis of Q fever.

Real-time PCR (RT-PCR) produces quantitative information that can help to distinguish between colonization and infection [38]. PCR can be used to detect resistance genes, thereby guiding the initial antibiotic treatment. New tools such as NGS are being developed to identify bacteria, fungi, and viruses in respiratory samples and may improve the diagnosis of concomitant infections [39]. Real-time metagenomics also holds promise for rapidly identifying the pathogens that cause bacterial pneumonia [40].

Initial empiric treatment of pneumonia should follow clinical practice guidelines and local resistance patterns. Severe pneumonia in immunocompromised patients is still often fatal; in a study of cancer patients—75% of whom had septic shock—the hospital mortality rate was 64.9% [22].

Mycobacterial pneumonia

The risk of active tuberculosis is increased in patients with immune impairments such as HIV, diabetes, cancer, or solid-organ transplantation (SOT), and those receiving systemic steroids or TNFα antagonist therapy [41].

The symptoms of mycobacterial infections are more insidious compared to those of CAP, and include persistent cough, lymphadenopathy, fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Immunocompromised patients may have only one or a few mild symptoms, such as persistent fever [42], even though dissemination of the organism outside the lungs is common [43]. HRCT findings include miliary nodules, cavitation, centrilobular tree-in-bud nodules, consolidation, mediastinal lymphadenopathy, and pleural effusion [44]. Cavitation and centrilobular tree-in-bud nodules are often located in the upper lobes.

The diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis is based on the demonstration of acid-fast bacilli on three induced sputum samples (smears and cultures) or a single FOB specimen. Culture requires Lowenstein–Jensen medium, and PCR testing should be done on the first sample [41]. False-negatives cultures are common. PCR testing on sputa has been reported to be 89% sensitive and 99% specific overall, with corresponding values of 67% and 99% in patients with negative sputum smear findings [41]. PCR may have a lower yield in HIV-negative than in HIV-positive immunocompromised patients. Adenosine deaminase and IFN-γ are markers for tuberculosis that can be measured in pleural fluid [41]. The interferon-γ release assay (IGRA) and tuberculin skin test (TST) serve to detect latent tuberculosis [41]. A combination of tuberculosis drugs must be given. There is some suggestion that steroid therapy might decrease mortality in critically ill patients with tuberculosis and ARF, although further data are needed [45]. Mortality rates in patients with tuberculosis and ARF have ranged from 50 to 70% [46].

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) species are mycobacteria other than M. tuberculosis and M. leprae. NTM are generally free-living organisms that are ubiquitous in the environment. To date, 200 NTM species have been identified. Human disease due to NTM is classified into four clinical syndromes: chronic pulmonary disease, lymphadenitis, cutaneous disease, and disseminated disease [47]. Risk factors for disseminated disease are similar to those for tuberculosis and include HIV infection, steroids, TNFα antagonists, diabetes, cancer, and SOT. Patients present with a cough, fatigue, malaise, weakness, dyspnea, chest discomfort, and, occasionally, hemoptysis. The extra-pulmonary manifestations seen in disseminated disease consist of arthritis, tenosynovitis, skin lesions, and gastrointestinal manifestations [48]. Fever and weight loss are less common than in patients with tuberculosis. Because NTMs exist in the environment, their presence in nonsterile respiratory specimens does not necessarily indicate a role in causing lung disease [47]. The American Thoracic Society (ATS)/Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) diagnostic criteria for NTM lung disease are as follows: pulmonary symptoms; compatible radiographic findings; and two positive sputum cultures or one positive BAL sample or other evidence of NTM such as a positive lung-biopsy culture with compatible histological features [47]. In disseminated disease, blood culture on special media should be performed. Mycobacterial cultures must be kept for at least 6 weeks. Bone marrow or fluid or tissue samples from suspected sites of involvement should be sent for culture and histological examination with special stains. The treatment relies on a combination of antibiotics. The treatment duration depends on the type of NTM and the manifestations [47].

Viral pneumonia

Common community-acquired respiratory viruses (CARVs) can cause severe and potentially fatal ARF in immunocompromised patients (Table 3). CARVs include influenza virus, parainfluenza virus (PIV), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), rhinovirus/enterovirus, and human metapneumovirus (hMPV).

Table 3.

Community-acquired respiratory virus (CARV)

| Type | Family | Genus | Virus |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA viruses | Orthomyxoviridae | Influenza A | All Influenza A subtypes |

| Influenza B | Influenza B | ||

| Paramyxoviridae | Rubulavirus |

Human parainfluenza virus type 2 (PIV-2) Human parainfluenza virus type 4a (PIV-4a) Human parainfluenza virus type 4b (PIV-4b) |

|

| Respirovirus |

Human parainfluenza virus type 1 (PIV-1) Human parainfluenza virus type 3 (PIV-3) |

||

| Pneumoviridae | Metapneumovirus | Human metapneumovirus (hMPV) | |

| Orthopneumovirus |

Human orthopneumovirus/Respiratory syncytial virus A (RSV-A) Human orthopneumovirus/Respiratory syncytial virus B (RSV-B) |

||

| Coronaviridae | Betacoronavirus |

Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (MERS-CoV) Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (SARS-CoV) Human coronavirus NL63 Human coronavirus 229E Human coronavirus HKU1 Human coronavirus OC43 |

|

| Picornaviridae | Enterovirus |

Enterovirus A-L Rhinovirus A, B, C |

#Nomenclature according to the 2018 International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses statement

Influenza is caused by influenza A and B viruses and characterized by annual seasonal epidemics and sporadic pandemic outbreaks. The WHO has estimated that annual influenza outbreaks affect 48.8 million people, of whom 22.7 million see a healthcare provider and nearly a million are admitted to hospital [49]. Among critically ill patients with influenza, 12.5% are immunocompromised, and their mortality is 2.5 times as high as in non-immunocompromised patients [50].

Among patients admitted for influenza, 10% are immunocompromised [51]. RSV infections are typically seasonal and pose similar serious risks to immunocompromised patients as does the influenza virus. RSV infection has been found in up to 12% of patients undergoing HCT, of whom one-third progressed to lower respiratory tract infection, which was fatal in about 30% of cases [52]. PIV causes respiratory diseases similar to those seen with RSV. RSV and PIV were found in 11% and 2.5% of nasopharyngeal swabs from critically ill hematology patients, respectively [53]. In a prospective study of HSCT recipients, PIV-3 accounted for 71% of viral respiratory infections [54]. The virus is often acquired in the community and brought into the transplant ward by staff, where it may mimic other opportunistic infections, thereby raising diagnostic challenges [55]. The hMPV is closely related to RSV and often causes severe infections requiring mechanical ventilation in patients who are elderly and/or have comorbidities [56]. Rhinoviruses/enteroviruses are Picornaviridae that circulate throughout the year and are increasingly recognized as a cause of lower respiratory tract infection in immunocompromised patients [53]. In critically ill hematology patients, rhinoviruses/enteroviruses were the most prevalent viruses detected at ICU admission (56%) [53].

Risk factors for viral pneumonia overlap those for bacterial pneumonia, and co-infection is common in patients with severe pneumonia [53]. Steroid therapy, hematological malignancies, lymphopenia, older age, and HCT are strongly associated with viral infections [21]. There is a seasonal distribution with peaks in the winter and spring [53]. The symptoms and imaging-study findings are not specific for viral infections, and overlap occurs with the changes seen in bacterial infections, although a diffuse airspace pattern is more common in bacterial pneumonia [57]. The main findings are the tree-in-bud and ground-glass patterns [58]. The diagnosis relies on identification of the virus in various samples. CARVs can be identified by cultures, serology, or rapid diagnostic tests based on enzyme immunoassay (EIA), immunofluorescence, or PCR. Molecular amplification techniques have largely superseded cell cultures as the primary means of detecting and identifying viruses in clinical samples. PCR is now the reference standard diagnostic test [59]. The IDSA recommends that all immunocompromised patients presenting with acute onset of respiratory symptoms be tested for influenza. PCR-based diagnostic panels can detect multiple respiratory viruses simultaneously within 2–3 h [60]. These new sensitive methods increase the ability to identify a broader range of viruses, such as rhinovirus, whose clinical significance should be carefully assessed. Uncertainty still surrounds the type of sample most appropriate for detecting each type of virus (nasal/throat swab, BAL, mini-BAL, cytopathology, or even lung biopsy when performed) [61]. An important consideration when choosing the sampling technique is the clinical condition of the patient. In patients receiving mechanical ventilation, endotracheal aspirates or BAL fluid should be collected, even when influenza tests on upper respiratory tract specimens are negative [59]. In a study of pulmonology ward patients that used BAL as the reference standard, nasopharyngeal PCR testing had positive and negative predictive values of 88% and 89%, respectively [62]. When a virus is identified in the respiratory tract, differentiating colonization from infection may be challenging [53]. However, presence of the influenza virus usually indicates infection. In RSV infection, blood testing may be helpful, as RSV-RNA was detected in plasma samples of one-third of HSCT patients with pulmonary RSV infection and was associated with a poor outcome [48].

Both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend oseltamivir as the first-line agent for influenza. Systemic steroids should not be used unless strongly indicated for another condition [63]. In patients with severe illness, prolonged treatment may be in order, although the optimal duration is uncertain. Testing for antiviral resistance at this stage should be considered, as immunocompromised patients are at higher risk of developing resistance and prolonged viral shedding [64]. RSV treatment with intravenous immunoglobulins and ribavirin has been suggested, but there is no published evidence that this treatment can benefit to the patient [65]. In recent epidemiologic studies, the prevalence of CARV in critically ill hematological patients was similar to that in the general population with CAP; however, the presence of CARV doubled the mortality rate [53]. Allogeneic HSCT recipients are at particularly high risk of death from CARV infection [54]. Among immunocompromised patients with the most severe forms of influenza, one-third requires ICU admission and mechanical ventilation and one-fifth have a fatal outcome [66].

In immunocompromised patients, the viruses most commonly responsible for systemic viral infections are DNA viruses. The herpes viruses responsible for pneumonia include herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2 (HSV-1, HSV-2), varicella–zoster virus (VZV), and cytomegalovirus (CMV). Herpes viruses are known to establish lifelong infections and can often reactivate during episodes of immunosuppression [67]. Adenoviridae include human adenoviruses (HAdV) A to G, each of which produces a different clinical pattern. In immunocompromised patients, HAdV can cause life-threatening multiorgan damage [68]. Risk factors change over time with the changes in immunosuppression [69]. Viral infections are most common in patients with T-cell deficiencies and are of particular concern in those taking high-dose steroids (≥ 20 mg/day for ≥ 4 weeks) or having received T-cell-depleted allogeneic HSCT or treatment with alemtuzumab or fludarabine [70]. Viral infections may be community-acquired or opportunistic, arise due to reactivation of latent infection, come from a transplant donor, or come from the transplant recipient (e.g., CMV reactivation when a seronegative patient receives a solid transplant from a seropositive donor or when a seropositive recipient receives an HSCT from a seronegative donor) [71]. Endogenous reactivation appears to be the predominant cause of viral disease in severely immunocompromised patients.

In patients with immunosuppression, the presentation of systemic viral infections varies widely depending on the causative organism and degree of immunosuppression (Table 4). When the lungs are involved, the respiratory symptoms are nonspecific (tachypnea and/or dyspnea, hypoxia). The lung infiltrates typically appear as a crazy-paving pattern, ground-glass opacities, micro-nodules, and/or consolidations. A definite diagnosis of CMV pneumonia requires clinical symptoms of pneumonia and identification of CMV in lung tissue by virus isolation, rapid culture, histopathology, immunohistochemistry, or DNA hybridization techniques [72]. Probable CMV pneumonia is defined as clinical symptoms and/or signs of pneumonia combined with CMV detection by viral isolation, rapid BAL fluid culture, or CMV DNA quantitation in BAL fluid. No reliable cut-off for the CMV DNA load has been established, however. Furthermore, CMV shedding may occur in the lower respiratory tract, and the CMV DNA load may, therefore, be low in patients with asymptomatic infection [72]. On the other hand, a negative CMV DNA test in BAL fluid has nearly 100% negative predictive value and, therefore, excludes CMV pneumonia, assuming satisfactory sampling. VZV pneumonia is usually readily diagnosed based on the typical skin rash, although it may fail to develop in patients with severe immunosuppression [73]. Replicating VZV is almost always found in BAL fluid [73].

Table 4.

Systemic viruses responsible for pneumonia in immunocompromised patients

| Virus type | Source | Extra-respiratory manifestations | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSV (HSV-1, HSV-2) |

Donor transmission to transplant recipient Reactivation in T-cell defects |

Skin and genital eruption Encephalitis, esophagitis, Keratitis |

PCR (blood, BAL, tissue) Tissue culture Serology Histopathology |

| VZV |

Donor transmission to transplant recipient Reactivation in T-cell defects |

Varicella, herpes zoster Encephalitis, cerebellitis, hepatitis, myelitis Herpes zoster ophthalmicus |

PCR Direct fluorescent antibody testing Viral culture Histopathology |

| CMV |

Donor transmission to transplant recipient Reactivation in T-cell defects |

Esophagitis, gastritis, colitis Retinitis, encephalitis, myelitis, polyradiculopathy Neutropenia |

PCR (blood, BAL) Histopathology Serology |

| Adenovirus | Reactivation |

Hemorrhagic cystitis, nephritis Colitis, hepatitis, encephalitis |

Viral culture (nasal, blood, urine, CSF, tissues) EIA, Immunofluorescence, PCR, serology Histopathology |

HSV herpes simplex virus, VZV varicella–zoster virus, CMV cytomegalovirus, PCR polymerase chain reaction, BAL bronchoalveolar lavage, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, EIA enzyme immunoassay

HSV pneumonia is more challenging to diagnose, as reactivation in blood, saliva, or the throat is frequent in critically ill patients [74]. Thus, HSV detection in the lower airways may merely indicate airway contamination without parenchymal involvement. The diagnosis rests on HSV detection in BAL fluid and on the demonstration of specific nuclear inclusions in BAL cells [74]. Macroscopic bronchial lesions may be seen during fiberoptic bronchoscopy, albeit only rarely [74].

Further research is needed to improve the early detection of systemic viral infections at the subclinical phase. The ways in which immune deficiencies affect host defenses against viral infections need clarification. In the field of treatment, the optimal indications and duration of antiviral prophylaxis should be better defined, and the potential influence of new immunotherapeutic and molecular-targeted approaches on the emergence of systemic viral infections should be assessed [8]. The use of quantitative real-time PCR on biopsies and BAL fluid is the focus of active research that may allow the differentiation of CMV pneumonia and colonization [75]. Antiviral drugs and immunomodulation are the main treatment tools.

Invasive fungal infections

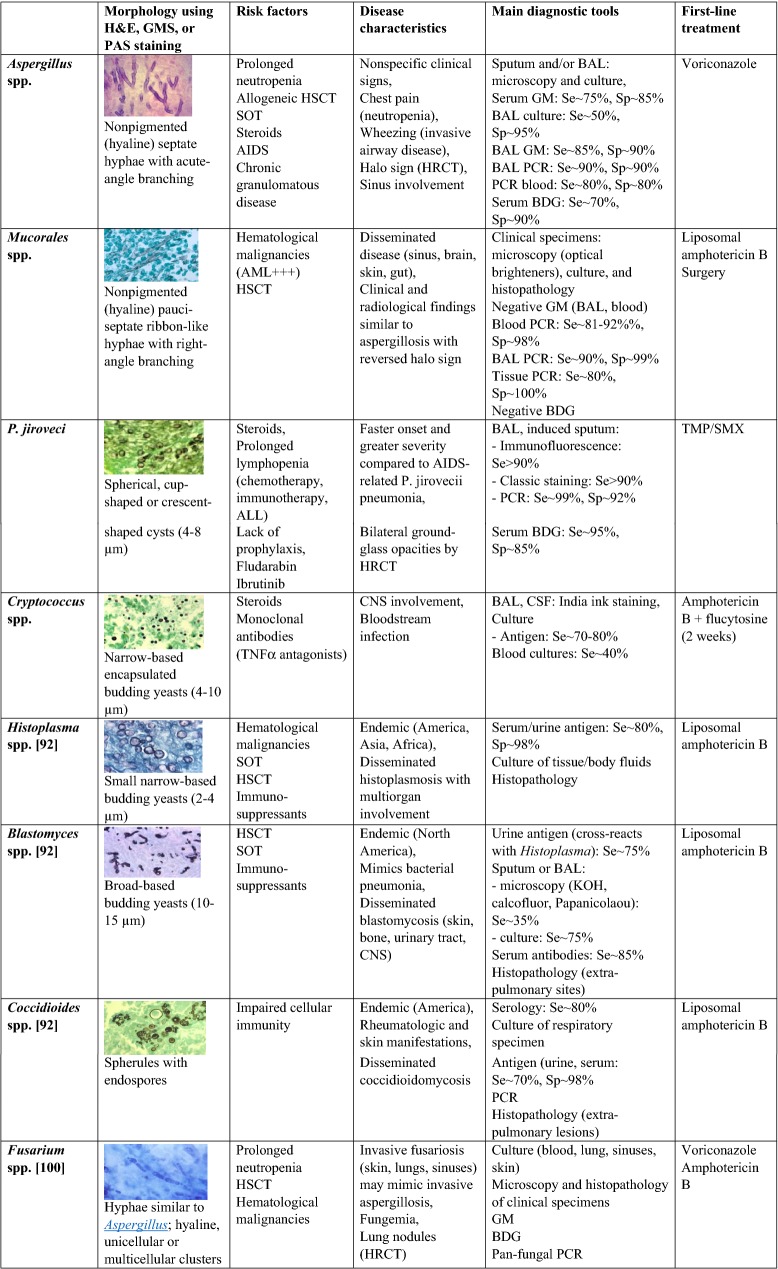

The three most important causes of fungal pulmonary infection are Pneumocystis jirovecii, Aspergillus spp., and Cryptococcus spp [76]. Pneumocystis jirovecii is an airborne pathogen transmitted from asymptomatic carriers to immunocompromised hosts [77]. The main risk factors are treatments that impair T-cell immunity, including steroids; acute lymphocytic leukemia; HSCT and SOT; and a number of primary immunodeficiencies [78]. Aspergillus spp. are molds that cause infection in the lungs and sinuses. The risk factors consist chiefly of severe and prolonged neutropenia, acute myeloid leukemia, HSCT, high-dose steroid therapy, and drugs or conditions that chronically impair the T-cell responses. Invasive aspergillosis (IA) is most common in patients exposed to heavy fungal loads, for instance on construction sites [79]. The cumulative incidence of IA 12 months after SOT was 0.7% in one study and was highest in lung transplant recipients [80]. In HSCT recipients, the incidence at 12 months was 1.6% [81]. Cryptococcus spp. are yeasts that can affect the lungs and central nervous system in patients with impaired T cell-mediated responses. C. neoformans and C. gattii account for most cases of cryptococcosis. Reactivation of dormant organisms is probably the main mechanism of lung involvement. Risk factors for pulmonary cryptococcosis include malignancies, HSCT, SOT, cirrhosis, chronic kidney disease, chronic lung disease, diabetes, and treatment with steroids or TNFα antagonists [82]. In SOT recipients, cryptococcosis accounted for about 8% of invasive fungal infections, with an overall incidence of 0.2–5% [83]. Mucorales causes aggressive invasive infections in patients with hematological malignancies and in HSCT recipients. Fusarium mostly affects patients with hematological malignancies and HSCT recipients and involves the lungs and sinuses. Other pulmonary fungal infections are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Invasive fungal infections: clinical characteristics and diagnostic tools.

Source of images: Public Health Images Library, CDC (https://phil.cdc.gov)

H&E hematoxylin and eosin, GMS Grocott methenamine silver, PAS periodic acid Schiff, HSCT hematopoietic stem-cell transplant, SOT solid-organ transplant, AIDS acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, HRCT high-resolution computed tomography of the chest, BAL bronchoalveolar lavage, GM galactomannan, BDG beta-d glucan, Se sensitivity, Sp specificity, PCR polymerase chain reaction, AML acute myeloid leukemia, ALL acute lymphoblastic leukemia, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, TMP/SMX trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, TNF tumor necrosis factor, CNS central nervous system, CSF cerebrospinal fluid

Patients with pulmonary fungal infections present with nonspecific symptoms such as a fever, cough, dyspnea, pleuritic pain, and/or hemoptysis. Extra-pulmonary symptoms may help to suspect invasive fungal disease. In IA, HRCT shows macronodules with a halo sign, pleural-based wedge-shaped consolidations, or masses. Mucormycosis and IA share clinical and radiological findings, but mucormycosis should be suspected in the presence of sinus involvement, prior voriconazole therapy, or a reversed halo sign on HRCT. In P. jirovecii pneumonia, HRCT shows bilateral ground-glass opacities predominating at the apices and sparing the periphery. The most common findings in pulmonary cryptococcosis are solitary or sparse, well-defined, non-calcified nodules that are often pleural-based [84].

Invasive fungal infections (IFI) are classified as proven (signs of infection and fungus identified by histopathology, cytopathology, or culture), probable (based on host factors, clinical criteria, microscopy, culture, galactomannan antigen [GM], or possible (based on host factors and clinical criteria) [88]. The diagnosis of P. jirovecii pneumonia (PJP) relies on identification of the pathogen by immunofluorescence and quantitative PCR (on BAL fluid ideally and induced sputum otherwise); serum BDG testing can be helpful for difficult cases where there is a discrepancy between the clinical picture and PCR findings, or to make the difference between colonization and infection when PCR findings are in the gray zone [85]. In a study of HIV-negative immunocompromised patients, quantitative PCR on BAL fluid was 87% sensitive and 92% specific and helped to differentiate infection and colonization [86]. According to a meta-analysis, the serum BDG assay is 95% sensitive and 86% specific [87]. In IA (Figure S1), BAL microscopy and culture show branching septate hyphae. Aspergillus spp. grows in 2–5 days, but the culture yield is low. When IA is suspected in patients at high risk due to a hematological malignancy, HSCT, or SOT, serum Aspergillus PCR and GM testing are recommended (Fig. 1). PCR and GM testing may perform better on BAL fluid than on serum, although FOB/BAL should be done only if indicated by a careful risk/benefit assessment [88]. Serum BDG testing is recommended in high-risk patients, but is not specific for IA. A 2015 systematic review found that sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing IA were 81.6% and 91.6% for serum GM and 76.9% and 89.4% for serum BDG, compared to 77–88% sensitivity and 75–95% specificity for PCR [89]. Mucormycosis is diagnosed by sample microscopy, culture, and/or histopathology. Immunohistochemistry is 100% sensitive and 100% specific [90]. Mucorales fungi contain neither BDG nor GM, and negative results from these tests in a patient whose HRCT findings are consistent with IFI, therefore, suggest mucormycosis [91]. However, concomitant Aspergillus infection is possible. The diagnosis of Cryptococcus pneumonia, whether isolated or with central nervous system involvement, relies on visualization of the pathogen by microscopy or on culturing of cerebrospinal fluid, blood, and/or sputum, in which Cryptococcus grows within 2–3 days. The cryptococcal antigen assay is less sensitive in HIV-negative than in HIV-positive patients: values of 56–83% have been reported in HIV-negative immunocompromised patients with Cryptococcus pneumonia [82, 92].

PJP is treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole [85]. The addition of steroid therapy in severe forms is currently not recommended in HIV-negative patients, but is being assessed in a randomized-controlled trial (NCT02944045). IA is treated with voriconazole [93]. The first-line treatment for mucormycosis is liposomal amphotericin B, although isavuconazole constitutes a valid alternative [94]. Severe cryptococcus pneumonia requires amphotericin B and flucytosine followed by fluconazole [95]. Fusarium infections are managed with voriconazole or amphotericin B [96].

New diagnostic methods are being developed to allow earlier diagnosis with greater sensitivity in patients with fungal infections. Assays for Mucorales-specific antigen or T cells and Mucorales PCR have shown good sensitivity and specificity with earlier positivity compared to cultures [97]. In patients with IFIs, mass spectrometry to detect panfungal serum disaccharide was 51% and 64% sensitive for diagnosing invasive candidiasis and IA, respectively, with higher specificities of 87% and 95%, respectively; for mucormycosis, the test made a similar contribution to the diagnosis as did quantitative PCR [98].

Although survival has improved over time, IA remains an often fatal complication after HSCT. In a retrospective study of patients with hematological malignancies who developed ARF due to IA, 1-year mortality was 72% [99]. Mortality in transplant recipients was 49.4%, with a higher rate after HSCT (57.5%) than after SOT (34.4%) [100]. PJP is more often fatal in HIV-negative than in HIV-positive patients, and in HIV-negative patients, mortality varies widely, from 18% to 50%, depending on the underlying disease [101]. Finally, mortality rates of up to 66% have been reported in patients with pulmonary mucormycosis [102].

Parasitic infections

Many parasites cause respiratory infections in immunocompromised patients (Table 6) [103]. The two most common, Toxoplasma gondii and Strongyloides stercoralis, are associated with considerable mortality if left untreated.

Table 6.

Main parasites responsible for pneumonia [107]

| Disease | Parasite | Transmission | Endemic areas | Pulmonary manifestations | Extra-pulmonary manifestations | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Löffler syndrome |

- Ascaris: A. lumbricoides, A. suum - Hookworms: Ancylostoma duodenale, Necator americanus |

- Ascaris: oro-fecal or uncooked pig or chicken meat - Hookworms: skin contact with infected soil |

- Ascaris: worldwide - Hookworms: Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, Latin America, Caribbean |

- Cough - Burning substernal discomfort - Dyspnea - Wheezing - Blood-tinged sputum containing eosinophil-derived Charcot-Leyden crystals |

- Blood eosinophilia - Fever |

- Detection of Ascaris or hookworm larvae in respiratory secretions |

| Pulmonary amebiasis | Entamoeba histolytica | Oro-fecal | Worldwide |

- Hemoptysis - Expectoration of anchovy sauce-like pus - Respiratory distress |

- Gastrointestinal symptoms - Liver abscess - Brain abscess |

- Microscopy of sputum or pleural fluid - PCR - Serology - Antigen detection |

| Pulmonary leishmaniasis | Leishmania donovani and Leishmania infantum | Sandflies |

- L. donovani: South Asia, East Africa - L. infantum: Mediterranean basin, western Asia, South America |

- Pleural effusion - Mediastinal lymphadenopathy - Pneumonitis |

- Fever - Splenomegaly - Jaundice - Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis |

- Bone marrow aspiration - Microscopy - Culture - PCR - Serology |

| Pulmonary larva migrans |

Toxocara canis Toxocara cati |

- Dogs (Toxocara canis) - Cats (Toxocara cati) |

- Worldwide | - Asthma |

- Hepato-splenomegaly - Lymph node enlargement - Eye pain, strabismus - Abdominal pain - Neurological manifestations |

- IgE antibody detection - Antigen detection |

| Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia | Lymphatic filariasis: Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, Brugia timori | - Mosquitoes | - Tropical countries |

- Paroxysmal and nocturnal cough - Asthma-like attacks |

- Eosinophilia - Weight loss - Lymphadenopathy - Hepatomegaly, and/or splenomegaly |

- Serology - Antigen detection |

| Pulmonary paragonimiasis | - Paragonimus sp | - Eating raw crayfish or crabs |

- Far East - West Africa - America |

- Cough - Rusty brown or blood-stained sputum - Chest pain - Pleural effusion - Pneumonitis |

- Fever |

- Sputum microscopy - Stool sample examination - Serology |

| Pulmonary schistosomiasis | - Shistosoma sp | - Swimming in infected water | - Sub-Saharan Africa | - Dry cough |

- Myalgia, arthralgia - Diarrhea - Headache - Eosinophilia |

- Stool sample examination - Serology - Antigen detection in stool, blood, or urine |

| Pulmonary trichinellosis | - Trichinella spiralis | - Eating undercooked meat | - Worldwide | - Dry cough |

- Abdominal pain - Diarrhea - Muscle pain and weakness - Myocarditis - Eosinophilia |

- Serology - Muscle biopsy |

| Pulmonary babesiosis | - Babesia divergens and Babesia microti | - Tick bite |

- United States - Asia - Sporadic cases in Europe |

- Interstitial pneumonia |

- Fever - Headache - Drenching sweats |

- Blood smear examination - Serology - PCR |

Factors that promote T. gondii reactivation include impaired T-cell immunity, HIV infection, hematological malignancies, HSCT, and SOT [104]. After allogeneic HSCT, 16% of patients had a positive routine blood PCR, and 6% had invasive disease [105]. The risk is highest in seropositive allogeneic HSCT recipients who receive a seronegative graft [106]. The sparse data available for SOT recipients suggest lower rates. The risk of a seronegative recipient acquiring T. gondii from a seropositive donor depends on the organ type, being highest after heart transplantation [106]. Data on patients with solid tumors are scarce, but toxoplasmosis has only rarely been reported in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy [107].

In immunocompromised patients, fever may be the presenting symptom of toxoplasmosis, which may progress to multiple organ failure. The symptoms of disseminated toxoplasmosis are nonspecific; the lungs and central nervous system are often involved, and hepatitis, myocarditis, and chorioretinitis may develop [108]. Other features include lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, rhabdomyolysis, and lactate dehydrogenase elevation [104]. In the rare cases with isolated pulmonary involvement, the presentation may mimic interstitial pneumonia, PJP, or CMV pneumonia. CT may show lobar consolidations, ground-glass opacities, and thickening of the interlobular septa [108]. Serological testing is unreliable in immunocompromised patients, but may be useful in previously seronegative patients. The diagnosis rests on PCR on blood and BAL fluid samples and on microscopic examination of stained BAL fluid smears [109]. In a study of transplant recipients, blood PCR was 90% sensitive [106]. The treatment consists of at least 6 weeks of pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and leucovorin induction, followed by reduced-dose maintenance therapy [109]. The prognosis of disseminated toxoplasmosis involving the lungs is grim, with a 78% mortality rate in ICU patients [104, 106].

Streptococcus stercoralis is a nematode that infects humans through skin contact with larvae containing soil. The prevalence varies across geographic areas, with Africa, South America, and Asia being regions of high endemicity. About 30–100 million people may be infected worldwide [110]. In industrialized countries, strongyloidiasis is seen in immigrants, tourists, and military personnel returning from endemic areas [111]. In a US cohort of kidney transplant candidates, 9.9% were seropositive for S. stercoralis [112]. Risk factors include walking barefoot, engaging in work that involves skin contact with soil, and poor sanitary conditions [111].

Streptococcus stercoralis hyperinfection syndrome (SSIS) occurs when chronically infected patients become immunosuppressed (notably those receiving steroids), or if immunosuppressed patients develop acute strongyloidiasis. This results in uncontrolled over-proliferation of larvae with dissemination to end-organs, including the lungs, liver, and brain [113]. HTLV-1 infection is also a major risk factor for SSIS [114]. Patients present with nonspecific respiratory symptoms such as a cough, fever, hemoptysis, asthma, and ARF. The gastrointestinal symptoms include ileus and hemorrhage. Chest imaging may reveal nodular, reticular, or alveolar opacities, which may reflect a combination of edema, hemorrhage, and pneumonitis. Gram-negative sepsis is a common complication of SSIS, as larval invasion of the gut wall promotes bacterial translocation [115]. During SSIS, filariform larvae may be found in bodily fluids such as sputum, BAL, and pleural, and/or peritoneal fluid. Blood eosinophilia is present in most immunocompetent patients, but may be absent in immunocompromised patients [113], in whom serological testing is also unreliable. Given the nonspecific presentation of SSIS, the differential diagnosis is broad and includes all causes of pulmonary hemorrhage, ARF, and sepsis.

Ivermectin is the first-line treatment. The treatment is continued until 2 weeks after the last positive stool sample, to cover a complete autoinfection cycle. SSIS is always fatal if left untreated and has a reported 60% mortality rate in ICU patients [115].

Conclusion

As survival of cancer patients improves and breakthrough therapies are being developed, rising numbers of critically ill patients are immunocompromised. Severe bacterial pneumonias, followed by viral, fungal, and more rarely parasitic infections are the leading cause for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. When ICU admission is needed, mortality rates are high. Knowledge of the underlying immune deficiency and thorough clinico-radiological evaluation can guide the diagnostic strategy by targeting the most likely infectious agents and deciding on invasive versus non-invasive approach. Increasingly sophisticated non-invasive diagnostic tools avoid clinical deterioration sometimes encountered with invasive approaches and are now available or under evaluation (e.g., real-time PCR, next-generation sequencing, and transcriptomics), which could allow earlier diagnosis and thus improve survival in immunocompromised patients with severe pulmonary infections.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Funding

None.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

EA has received fees for lectures from Gilead, Pfizer, Baxter, and Alexion. His research group has been supported by Ablynx, Fisher & Payckle, Jazz Pharma, and MSD. IML reports personal fees from MSD and Gilead. PV has received consultation fees from Orion, Pfizer, and Technofage. PS received honoraria from Astellas, Basilea, Fisher & Paykel, Getinge, Gilead, Hill-Rom, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Kite, Merck, Orion, Pfizer Rokitan, and Shire. He also declares research support from Amgen, Astellas, Astro-Pharma, and Baxter. JR served a consultant or in the speakers bureau for Merck, Anchoagen, Pfizer, ROCHE and in the speakers bureau for Pfizer and MSD. JGM has received fees for lectures from Gilead. All other authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azoulay E, Mokart D, Kouatchet A, et al. Acute respiratory failure in immunocompromised adults. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7:173–186. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30345-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Contejean A, Lemiale V, Resche-Rigon M, et al. Increased mortality in hematological malignancy patients with acute respiratory failure from undetermined etiology: a Groupe de Recherche en Réanimation Respiratoire en Onco-Hématologique (Grrr-OH) study. Ann Intensive Care. 2016;6:102. doi: 10.1186/s13613-016-0202-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer PR, Chevret S, Yadav H, et al. Diagnosis and outcome of acute respiratory failure in immunocompromised patients after bronchoscopy. Eur Respir J. 2019 doi: 10.1183/13993003.02442-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azoulay E, Mokart D, Lambert J, et al. Diagnostic strategy for hematology and oncology patients with acute respiratory failure: randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:1038–1046. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0018OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evangelatos N, Satyamoorthy K, Levidou G, et al. Multi-Omics Research Trends in Sepsis: a Bibliometric, Comparative Analysis Between the United States, the European Union 28 Member States, and China. OMICS. 2018;22:190–197. doi: 10.1089/omi.2017.0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azoulay E, Pickkers P, Soares M, et al. Acute hypoxemic respiratory failure in immunocompromised patients: the Efraim multinational prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:1808–1819. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4947-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maschmeyer G, Carratalà J, Buchheidt D, et al. Diagnosis and antimicrobial therapy of lung infiltrates in febrile neutropenic patients (allogeneic SCT excluded): updated guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society of Hematology and Medical Oncology (DGHO) Ann Oncol. 2015;26:21–33. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azoulay E, Schlemmer B. Diagnostic strategy in cancer patients with acute respiratory failure. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:808–822. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0129-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azoulay E, Roux A, Vincent F, et al. A Multivariable prediction model for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in hematology patients with acute respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198:1519–1526. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201712-2452OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lemiale V, Mokart D, Resche-Rigon M, et al. Effect of noninvasive ventilation vs oxygen therapy on mortality among immunocompromised patients with acute respiratory failure: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:1711–1719. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charpentier E, Garnaud C, Wintenberger C, et al. Added value of next-generation sequencing for multilocus sequence typing analysis of a Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia outbreak1. Emerging Infect Dis. 2017;23:1237–1245. doi: 10.3201/eid2308.161295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chibucos MC, Soliman S, Gebremariam T, et al. An integrated genomic and transcriptomic survey of mucormycosis-causing fungi. Nat Commun. 2016;7:1–11. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guiton PS, Sagawa JM, Fritz HM, Boothroyd JC. An in vitro model of intestinal infection reveals a developmentally regulated transcriptome of Toxoplasma sporozoites and a NF-κB-like signature in infected host cells. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0173018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salas A, Pardo-Seco J, Barral-Arca R, et al. Whole exome sequencing identifies new host genomic susceptibility factors in empyema caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children: a pilot study. Genes (Basel) 2018 doi: 10.3390/genes9050240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toma I, Siegel MO, Keiser J, et al. Single-molecule long-read 16S sequencing to characterize the lung microbiome from mechanically ventilated patients with suspected pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:3913–3921. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01678-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee J-O, Kim D-Y, Lim JH, et al. Risk factors for bacterial pneumonia after cytotoxic chemotherapy in advanced lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer. 2008;62:381–384. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia JB, Lei X, Wierda W, et al. Pneumonia during remission induction chemotherapy in patients with acute leukemia. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10:432–440. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201304-097OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aguilar-Guisado M, Givaldá J, Ussetti P, et al. Pneumonia after lung transplantation in the RESITRA Cohort: a multicenter prospective study. Am J Transpl. 2007;7:1989–1996. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang G-C, Wu C-L, Pan S-H, et al. The diagnosis of pneumonia in renal transplant recipients using invasive and noninvasive procedures. Chest. 2004;125:541–547. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.2.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Pasquale MF, Sotgiu G, Gramegna A, et al. Prevalence and etiology of community-acquired Pneumonia in immunocompromised patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:1482–1493. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rabello LSCF, Silva JRL, Azevedo LCP, et al. Clinical outcomes and microbiological characteristics of severe pneumonia in cancer patients: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warny M, Helby J, Nordestgaard BG, et al. Lymphopenia and risk of infection and infection-related death in 98,344 individuals from a prospective Danish population-based study. PLoS Med. 2018;15:e1002685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gathmann B, Mahlaoui N, Ceredih GL, et al. Clinical picture and treatment of 2212 patients with common variable immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.12.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abreu C, Rocha-Pereira N, Sarmento A, Magro F. Nocardia infections among immunomodulated inflammatory bowel disease patients: a review. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:6491–6498. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i21.6491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fijen CA, Kuijper EJ, te Bulte MT, et al. Assessment of complement deficiency in patients with meningococcal disease in The Netherlands. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:98–105. doi: 10.1086/515075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vergidis P, Ariza-Heredia EJ, Nellore A, et al. Rhodococcus infection in solid organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Emerg Infect Dis J CDC. 2017 doi: 10.3201/eid2303.160633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bodro M, Carratalà J, Paterson DL. Legionellosis and biologic therapies. Respir Med. 2014;108:1223–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacobson K, Miceli M, Tarrand J, Kontoyiannis D. Legionella Pneumonia in Cancer Patients. Medicine. 2008;87:152–159. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181779b53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sickles EA, Greene WH, Wiernik PH. Clinical presentation of infection in granulocytopenic patients. Arch Intern Med. 1975;135:715–719. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1975.00330050089015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al (2015) Community-Acquired Pneumonia Requiring Hospitalization among U.S. Adults. In: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.insermbiblio.inist.fr/10.1056/NEJMoa1500245. https://www-nejm-org.proxy.insermbiblio.inist.fr/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1500245?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3Dwww.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Accessed 13 Oct 2019

- 32.Bonatti H, Pruett TL, Brandacher G, et al. Pneumonia in solid organ recipients: spectrum of pathogens in 217 episodes. Transpl Proc. 2009;41:371–374. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moreau A-S, Martin-Loeches I, Povoa P, et al. Impact of immunosuppression on incidence, aetiology and outcome of ventilator-associated lower respiratory tract infections. Eur Respir J. 2018 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01656-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bellew S, Grijalva CG, Williams DJ, et al. Pneumococcal and Legionella urinary antigen tests in community-acquired pneumonia: prospective evaluation of indications for testing. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:2026–2033. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. an official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200:e45–e67. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201908-1581ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johansson N, Kalin M, Tiveljung-Lindell A, et al. Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia: increased microbiological yield with new diagnostic methods. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:202–209. doi: 10.1086/648678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Menzies SM, Rahman NM, Wrightson JM, et al. Blood culture bottle culture of pleural fluid in pleural infection. Thorax. 2011;66:658–662. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.157842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strålin K, Ehn F, Giske CG, et al. The IRIDICA PCR/electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry assay on bronchoalveolar lavage for bacterial etiology in mechanically ventilated patients with suspected pneumonia. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie Y, Du J, Jin W, et al. Next generation sequencing for diagnosis of severe pneumonia: China, 2010–2018. J Infect. 2019;78:158–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2018.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pendleton KM, Erb-Downward JR, Bao Y, et al. Rapid pathogen identification in bacterial pneumonia using real-time metagenomics. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:1610–1612. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201703-0537LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lewinsohn DM, Leonard MK, LoBue PA, et al. Official American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Clinical Practice Guidelines: diagnosis of Tuberculosis in Adults and Children. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:e1–e33. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marques IDB, Azevedo LS, Pierrotti LC, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of tuberculosis in kidney transplant recipients in Brazil: a report of the last decade. Clin Transpl. 2013;27:E169–176. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gras J, De Castro N, Montlahuc C, et al. Clinical characteristics, risk factors, and outcome of tuberculosis in kidney transplant recipients: a multicentric case-control study in a low-endemic area. Transpl Infect Dis. 2018;20:e12943. doi: 10.1111/tid.12943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pereira M, Gazzoni FF, Marchiori E, et al. High-resolution CT findings of pulmonary Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in renal transplant recipients. Br J Radiol. 2016;89:20150686. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20150686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang JY, Han M, Koh Y, et al. Effects of corticosteroids on critically ill pulmonary tuberculosis patients with acute respiratory failure: a propensity analysis of mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:1449–1455. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ryu YJ, Koh W-J, Kang EH, et al. Prognostic factors in pulmonary tuberculosis requiring mechanical ventilation for acute respiratory failure. Respirology. 2007;12:406–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.01007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Longworth SA, Daly JS. Management of infections due to nontuberculous mycobacteria in solid organ transplant recipients—Guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin Transpl. 2019;33:e13588. doi: 10.1111/ctr.13588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Estimated Influenza Illnesses, Medical visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths in the United States—2017–2018 influenza season| CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/2017-2018.htm. Accessed 1 Oct 2019

- 50.Garnacho-Montero J, León-Moya C, Gutiérrez-Pizarraya A, et al. Clinical characteristics, evolution, and treatment-related risk factors for mortality among immunosuppressed patients with influenza A (H1N1) virus admitted to the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2018;48:172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Collins JP, Campbell AP, Openo K, et al. Outcomes of immunocompromised adults hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza in the United States, 2011–2015. Clin Infect Dis. 2019 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khanna N, Widmer AF, Decker M, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in patients with hematological diseases: single-center study and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:402–412. doi: 10.1086/525263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Legoff J, Zucman N, Lemiale V, et al. Clinical significance of upper airway virus detection in critically ill hematology patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199:518–528. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201804-0681OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kakiuchi S, Tsuji M, Nishimura H, et al. Human parainfluenza virus Type 3 infections in patients with hematopoietic stem cell transplants: the mode of nosocomial infections and prognosis. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2018;71:109–115. doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2017.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hall CB. Respiratory syncytial virus and parainfluenza virus. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1917–1928. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106213442507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vidaur L, Totorika I, Montes M, et al. Human metapneumovirus as cause of severe community-acquired pneumonia in adults: insights from a ten-year molecular and epidemiological analysis. Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9:86. doi: 10.1186/s13613-019-0559-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miller WT, Mickus TJ, Barbosa E, et al. CT of viral lower respiratory tract infections in adults: comparison among viral organisms and between viral and bacterial infections. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:1088–1095. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.6501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koo HJ, Lim S, Choe J, et al. Radiographic and CT features of viral pneumonia. Radiographics. 2018;38:719–739. doi: 10.1148/rg.2018170048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Uyeki TM, Bernstein HH, Bradley JS, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America: 2018 Update on Diagnosis, Treatment, Chemoprophylaxis, and Institutional Outbreak Management of Seasonal Influenzaa. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:895–902. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Walter JM, Wunderink RG. Testing for respiratory viruses in adults with severe lower respiratory infection. Chest. 2018;154:1213–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tasbakan MS, Gurgun A, Basoglu OK, et al. Comparison of bronchoalveolar lavage and mini-bronchoalveolar lavage in the diagnosis of pneumonia in immunocompromised patients. Respiration. 2011;81:229–235. doi: 10.1159/000323176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lachant DJ, Croft DP, Minton HM, et al. Nasopharyngeal viral PCR in immunosuppressed patients and its association with virus detection in bronchoalveolar lavage by PCR. Respirology. 2017;22:1205–1211. doi: 10.1111/resp.13049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pastores SM, Annane D, Rochwerg B, Corticosteroid Guideline Task Force of SCCM and ESICM, Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Critical Illness-Related Corticosteroid Insufficiency (CIRCI) in Critically Ill Patients (Part II): Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) 2017. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:146–148. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fiore AE, Fry A, Shay D, et al. Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza—recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shah JN, Chemaly RF. Management of RSV infections in adult recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2011;117:2755–2763. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-263400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Taylor G, Abdesselam K, Pelude L, et al. Epidemiological features of influenza in Canadian adult intensive care unit patients. Epidemiol Infect. 2016;144:741–750. doi: 10.1017/S0950268815002113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee HS, Park JY, Shin SH, et al. Herpesviridae viral infections after chemotherapy without antiviral prophylaxis in patients with malignant lymphoma: incidence and risk factors. Am J Clin Oncol. 2012;35:146–150. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318209aa41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hemmersbach-Miller M, Bailey ES, Kappus M, et al. Disseminated adenovirus infection after combined liver-kidney transplantation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:408. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fishman JA. Infection in solid-organ transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2601–2614. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra064928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sandherr M, Hentrich M, von Lilienfeld-Toal M, et al. Antiviral prophylaxis in patients with solid tumours and haematological malignancies–update of the Guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society for Hematology and Medical Oncology (DGHO) Ann Hematol. 2015;94:1441–1450. doi: 10.1007/s00277-015-2447-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Koval CE. Prevention and treatment of cytomegalovirus infections in solid organ transplant recipients. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2018;32:581–597. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ljungman P, Boeckh M, Hirsch HH, et al. Definitions of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in transplant patients for use in clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:87–91. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mirouse A, Vignon P, Piron P, et al. Severe varicella-zoster virus pneumonia: a multicenter cohort study. Crit Care. 2017;21:137. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1731-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Luyt C-E, Combes A, Deback C, et al. Herpes simplex virus lung infection in patients undergoing prolonged mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:935–942. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200609-1322OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lee HY, Rhee CK, Choi JY, et al. Diagnosis of cytomegalovirus pneumonia by quantitative polymerase chain reaction using bronchial washing fluid from patients with hematologic malignancies. Oncotarget. 2017;8:39736–39745. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fishman JA, Rubin RH. Infection in organ-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1741–1751. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806113382407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ponce CA, Gallo M, Bustamante R, Vargas SL. Pneumocystis colonization is highly prevalent in the autopsied lungs of the general population. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:347–353. doi: 10.1086/649868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stern A, Green H, Paul M, et al. Prophylaxis for Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) in non-HIV immunocompromised patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005590.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kanamori H, Rutala WA, Sickbert-Bennett EE, Weber DJ. Review of fungal outbreaks and infection prevention in healthcare settings during construction and renovation. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:433–444. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pappas PG, Alexander BD, Andes DR, et al. Invasive fungal infections among organ transplant recipients: results of the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network (TRANSNET) Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1101–1111. doi: 10.1086/651262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kontoyiannis DP, Marr KA, Park BJ, et al. Prospective surveillance for invasive fungal infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, 2001–2006: overview of the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network (TRANSNET) Database. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1091–1100. doi: 10.1086/651263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pappas PG, Perfect JR, Cloud GA, et al. Cryptococcosis in human immunodeficiency virus-negative patients in the era of effective azole therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:690–699. doi: 10.1086/322597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sun H-Y, Wagener MM, Singh N. Cryptococcosis in solid-organ, hematopoietic stem cell, and tissue transplant recipients: evidence-based evolving trends. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1566–1576. doi: 10.1086/598936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lindell RM, Hartman TE, Nadrous HF, Ryu JH. Pulmonary cryptococcosis: CT findings in immunocompetent patients. Radiology. 2005;236:326–331. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2361040460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Alanio A, Hauser PM, Lagrou K, et al. ECIL guidelines for the diagnosis of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with haematological malignancies and stem cell transplant recipients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:2386–2396. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Azoulay É, Bergeron A, Chevret S, et al. Polymerase chain reaction for diagnosing pneumocystis pneumonia in non-HIV immunocompromised patients with pulmonary infiltrates. Chest. 2009;135:655–661. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Karageorgopoulos DE, Qu J-M, Korbila IP, et al. Accuracy of β-d-glucan for the diagnosis of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:39–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hage CA, Carmona EM, Epelbaum O, et al. Microbiological laboratory testing in the diagnosis of fungal infections in pulmonary and critical care practice. an official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200:535–550. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201906-1185ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.White PL, Wingard JR, Bretagne S, et al. Aspergillus polymerase chain reaction: systematic review of evidence for clinical use in comparison with antigen testing. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:1293–1303. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Choi S, Song JS, Kim JY, et al. Diagnostic performance of immunohistochemistry for the aspergillosis and mucormycosis. Mycoses. 2019 doi: 10.1111/myc.12994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cornely OA, Arikan-Akdagli S, Dannaoui E, et al. ESCMID and ECMM joint clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of mucormycosis 2013. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(Suppl 3):5–26. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Singh N, Alexander BD, Lortholary O, et al. Pulmonary cryptococcosis in solid organ transplant recipients: clinical relevance of serum cryptococcal antigen. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:e12–18. doi: 10.1086/524738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ullmann AJ, Aguado JM, Arikan-Akdagli S, et al. Diagnosis and management of Aspergillus diseases: executive summary of the 2017 ESCMID-ECMM-ERS guideline. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24(Suppl 1):e1–e38. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tissot F, Agrawal S, Pagano L, et al. ECIL-6 guidelines for the treatment of invasive candidiasis, aspergillosis and mucormycosis in leukemia and hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. Haematologica. 2017;102:433–444. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.152900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]