Abstract

Background

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a major infectious disease pandemic that occurred in early 2003, and one of the diagnostic criteria is the presence of chest radiographic findings.

Objective

To describe the radiographic features of SARS in a cluster of affected children.

Materials and methods

The chest radiographs of four related children ranging in age from 18 months to 9 years diagnosed as having SARS were reviewed for the presence of air-space shadowing, air bronchograms, peribronchial thickening, interstitial disease, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, hilar lymphadenopathy and mediastinal widening.

Results

Ill-defined air-space shadowing was the common finding in all the children. The distribution was unifocal or multifocal. No other findings were seen on the radiographs. None of the children developed radiographic findings consistent with acute respiratory distress syndrome. All four children showed significant resolution of the radiographic findings 4–6 days after the initial radiograph.

Conclusions

Early recognition of these features is important in implementing isolation and containment measures to prevent the spread of infection. SARS in children appears to manifest as a milder form of the disease as compared to adults.

Keywords: Thorax, Lung, Infection, Pneumonia, Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Radiography, Child

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a new form of atypical pneumonia, and is an infectious disease which has caused a pandemic with significant public health concerns. Singapore was one of the earliest areas to be affected, with the index case admitted to a local hospital on 1 March 2003 [1]. Since then, there have been more than 7700 cases worldwide and 205 cases in Singapore, both as of 16 May 2003 [2]. One of the factors which contributes to the large number of cases is that the disease is easily transmissible via droplet infection from close contact. This situation is seen in the household setting, where family members are at risk of contracting the disease from an infected person. The number of children infected appears to be relatively small. We report a cluster of four children affected with SARS in this way, with emphasis on the contact history and radiological features.

Case histories

Three female siblings, patients A, B and C, aged 4, 8 and 9 years, respectively, were referred by a family physician to Tan Tock Seng Hospital, the hospital in Singapore designated for the treatment of SARS. They all presented with a 4- to 5-day history of pyrexia of more than 38.5°C, headache and myalgia. None of three children had respiratory symptoms of cough or dyspnoea, and there was no recent travel history. They had been previously well with no significant past medical history.

Clinical examination of the children showed them to be febrile but not toxic. Five other close family members, including their mother and grandfather, were also referred on the same day with a 1-day history of high fever of more that 38.5°C, myalgia and cough. In view of the large number of ill family members with symptoms, there was a high index of suspicion for SARS. As such, the children and other affected family members were admitted for further assessment and investigation. Their 18-month-old cousin, patient D, was admitted 2 days later with a 5-day history of fever and dry cough.

Of note, their grandmother, who was the primary caregiver of all four children, had recently fallen ill, 1 week prior to their admission. She presented initially with severe headache followed by a high fever and cough. She then rapidly deteriorated, collapsed suddenly, and passed away at home within 3 days of falling ill. She had been healthy prior to this episode of illness and had no past medical history of note. The postmortem examination performed did not find a cause for her sudden demise, but no investigations for SARS were done at the time in view of the lack of travel history and the apparent lack of contact history. This was later done and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for coronavirus was positive. The link in the contact history only emerged later, when it was discovered that the grandfather of the children worked in a local wholesale vegetable market where there had been a recent community outbreak of SARS. He subsequently also passed away from a SARS-related cause.

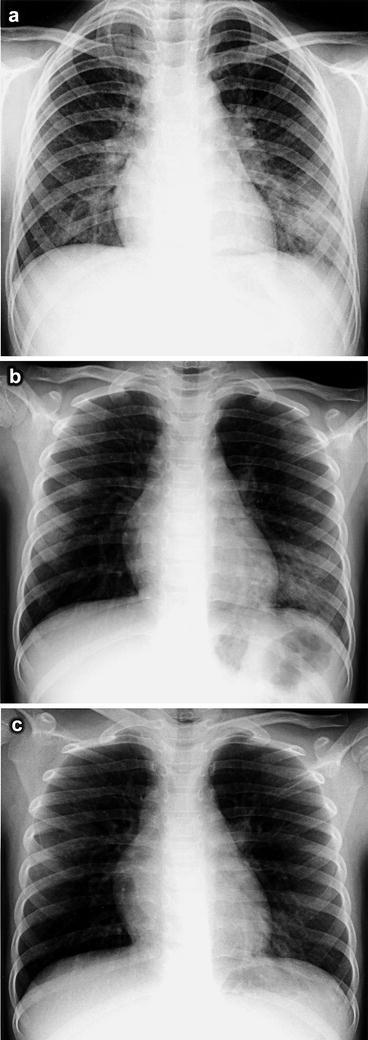

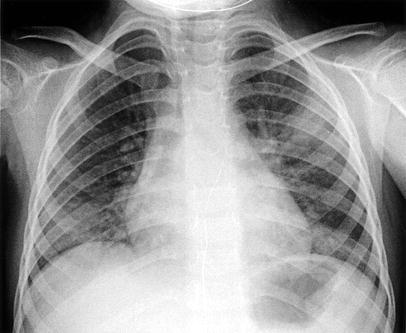

Despite the lack of respiratory symptoms, the initial chest radiographs in all four patients were all abnormal. Each patient showed either one or two areas of air-space shadowing, which were zonal in distribution. The typical appearance and pattern of progression is illustrated with patient B. The radiograph at presentation showed a single rounded area of ill-defined air-space consolidation in the lateral aspect of the left lower zone (Fig. 1a). The size and appearance of the consolidation was essentially unchanged on the second radiograph 2 days later, and partial resolution was seen on the third radiograph taken 4 days after the first (Fig. 1b). The last radiograph on the day of discharge showed almost complete resolution (Fig. 1c). In all four patients, no other areas of consolidation developed apart from that already present in the initial radiograph. No pleural effusions or pneumothoraces were noted throughout the course of the disease. Bilateral involvement was seen in patient A (Fig. 2), and unilateral multifocal consolidation in patient C (Fig. 3). Patient D had a single area of consolidation in the left upper zone (Fig. 4). The distribution of the radiographic abnormalities is detailed in Table 1. All four children showed significant resolution of the radiographic appearances by 4–6 days after the initial radiograph, similar to that demonstrated in patient B.

Fig. 1a–c.

Chest radiographs of patient B. a At presentation there is a single focus of ill-defined consolidation in the left lower zone. b Four days later there is reduction in size of the left lower zone consolidation. c Seven days after the initial radiograph, at the time of discharge, there is almost complete resolution of the left lower zone consolidation

Fig. 2.

Chest radiograph of patient A at presentation showing bilateral consolidation in the left upper zone and right lower zone

Fig. 3.

Chest radiograph of patient C at presentation showing multifocal involvement in the right middle and lower zones

Fig. 4.

Chest radiograph of patient D at presentation showing a single focus of consolidation in the left upper zone

Table 1.

Pattern of distribution of pulmonary involvement with SARS in our cluster of patients

| Patient | Distribution of radiographic findings in the lungs |

|---|---|

| A | Left upper zone and right lower zone |

| B | Left lower zone only |

| C | Right middle and lower zones |

| D | Left upper zone only |

All four children were initially treated on admission with a combination therapy of ampicillin with a beta-lactamase inhibitor and a macrolide to cover community-acquired pneumonia. Initial and subsequent full blood counts showed leucopenia (range 2.2–3.8×109/l) but no lymphopenia, and mild thrombocytopenia (149–164x109/l). The lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels were also raised (600–929 U/l) in all four children. Blood cultures did not yield any bacterial growth. Nasal aspirates for other respiratory viruses were negative in all.

Oral ribavarin was started for patients A, B and C when they remained febrile and their chest radiographs showed continued progression of pneumonia after 72 h of antibiotic therapy. Their fever finally settled 7 days after admission. Patient D's fever settled 48 h after admission and as her pneumonia did not show any evidence of progression, she was not treated with ribavarin.

Though diagnostic tests have not been validated, the PCR for coronavirus was positive in patients A, C and D but negative in patient B. None of the children required intensive care; they also did not require any form of ventilatory support or supplemental oxygen therapy.

Regarding their outcomes, patients A, B and C were discharged from hospital 8 days after admission and patient D, 6 days after admission. The discharge criteria were based on resolution of fever for more than 72 h, with improvement in chest radiographic findings.

Discussion

The diagnosis of SARS at present is based on case definitions issued by the World Health Organisation (WHO) [3]. The initial case definitions for surveillance of SARS were revised on 1 May 2003 to include classification of probable cases based on positive assays of the SARS coronavirus, which has been identified as the causative organism [4]. However, these PCR tests need to be further validated, as there appears to be poor sensitivity with high false-negative results. Also, when community outbreaks occur, a contact source may not always be found immediately. As such, a high index of suspicion is needed in the assessment and evaluation of SARS patients. Stringent infection control measures have been implemented in Singapore, with isolation procedures, quarantine enforcement and notification of cases being the mainstays of prevention [5].

SARS in children appears to manifest as a milder form of the disease as compared to that in adults. The initial reports from both Canada and Hong Kong did not have any patients below the age of 20 years [6, 7]. A more recent report from Hong Kong of ten patients in the paediatric age group had only five below the age of 12 years [8]. Their preliminary findings showed that younger children develop a milder form of the disease with a less-aggressive clinical course, as compared to teenagers and adults. However, no discernible difference in the pattern of radiographic involvement was noted.

Other common viral organisms causing pneumonia in children include adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus and parainfluenza viruses. In general, the radiographic features do not allow identification of a specific causative virus, and SARS does not appear to be any different. The basic findings of viral pneumonia are wide-ranging, and include interstitial infiltrates to areas of diffuse consolidation which may coalesce over time. Respiratory syncytial virus pneumonia has also been described with peribronchial infiltrates and hyperinflation [9], and adenovirus infection manifesting as patchy or confluent widespread consolidations [10].

In summary, young children appear to show a much milder response to SARS as compared to older children and adults. This is seen in both the clinical and radiographic features, where none of our patients went into respiratory distress requiring mechanical ventilation or intensive care, and the changes on the chest radiographs did not worsen after initial presentation. The difference is interesting, and could possibly be related to a difference in immune response in the different age groups. Further studies with a larger pool of patients are warranted, and this may assist in further identifying the behaviour of the implicated coronavirus.

References

- 1.Kaw Singapore Med J. 2003;44:201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organisation (2003) Cumulative number of reported probable cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). http://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/2003-05-16/en/. Cited 16 May 2003

- 3.World Health Organisation (2003) Case definitions for surveillance of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). http://www.who.int/csr/sars/casedefinition/en/. Cited 15 May 2003

- 4.Peiris Lancet. 2003;361:1319. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2003;78:157. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poutanen N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1995. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsang N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1977. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hon Lancet. 2003;361:1701. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13364-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simpson Pediatr Radiol. 1974;2:155. doi: 10.1007/BF00972727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osborne AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1979;133:397. doi: 10.2214/ajr.133.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]