The term “ace in the hole” originates from the game of poker, where a card dealt face down and kept hidden is called a “hole” card. The most propitious card in the hole is the ace. A 1951 movie by the same name featured Kirk Douglas, who played a cynical, disgraced reporter delaying a rescue to cash in on the notoriety of having exclusive reporting rights to the rescue attempt. But since the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) can be inhibited, any disgrace is long gone. Instead, the angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) could be arguably a biological “ace in the hole.” ACE2 is an exopeptidase that catalyzes the conversion of angiotensin (Ang) I to the nonapeptide Ang 1–9 or the conversion of Ang II to Ang 1–7 [1, 2]. ACE2 has direct effects on cardiac function and is expressed predominantly in vascular endothelial cells of the heart and the kidneys. In addition, ACE2 is the receptor for the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) virus. Such diverse activities raise the thought that perhaps ACE2 has a different origin or diverse functions, not restricted to the renin-angiotensin system. In addition, ACE2 is structurally a chimeric protein that has emerged from the duplication of two genes. The enzyme has homology with ACE at the carboxypeptidase domain and homology with collectrin in the transmembrane C-terminal domain. Collectrin is associated with multiple apical transporters and defines a novel group of renal amino acid transporters. Collectrin appears to be a key regulator of renal amino acid uptake [3].

We provided evidence of ancestral functions of the renin-angiotensin system’s emergence of both ACE and ACE2 earlier [4]. We found orthologs of both proteins in the tunicate sea squirt, Ciona intestinalis, and in a primitive chordate, amphioxus Branchiostoma floridae (500 Ma ago). These two model organisms lack most of the molecular and physiological components of the renin-angiotensin system, including angiotensinogen. ACE and ACE2 were also absent in the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster. However, the arthropod has homologous sequences sharing possible ancestry that belong to different enzyme families, namely, the angiotensin-converting enzyme-related gene (ANCE) and angiotensin-converting-related (ACER) proteins. Both of these enzymes are active endopeptidases during fly development but seem to lack a clear function in adulthood. As a matter of fact, an ancient precursor (ACN 1) resides in the Precambrian (750 Ma ago) round worm, Caenorhabditis elegans [4].

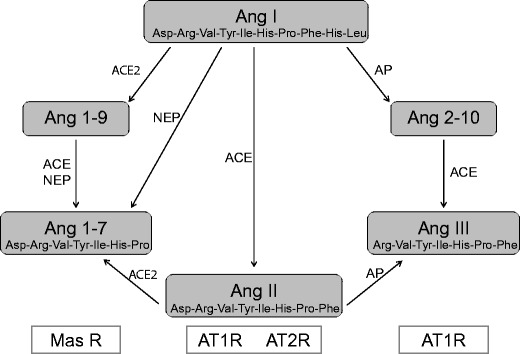

We can now concern ourselves with what ACE2 might be doing today (Fig. 1). The ACE2 crystal structure suggests that the differences in substrate specificity, compared to ACE, are a result of binding pocket differences in ACE2. Various enzymes can generate Ang 1–7, such as prolyl-endopeptidase, thimet oligopeptidase, and neprilysin. However, ACE2 appears to be the main enzyme that catalyzes this reaction in vitro and in vivo. The ACE2 product, Ang 1–7, is said to interact with the G protein-coupled receptor Mas to mediate vasoprotective effects, at least under today’s environmental conditions. ACE2 also signals via the C-terminal amino acids of the peptides apelin 13 and apelin 36. Apelins are novel peptides that act through the Ang-like 1 (APJ) receptor, sharing similarities with the Ang II type 1 (AT1) receptor pathway [5]. Aside from this new member, another upstart has appeared on the scene: Alamandine is a vasoactive peptide with similar protective actions as Ang 1–7 that acts through the Mas receptor and which may represent another important counter-regulatory mechanism within the renin-angiotensin system [6]. ACE2 can evidently foster the generation of alamandine through the cleavage of Ang A. Jankowski et al. recently identified the octapeptide Ang A, which is highly similar to Ang II, only differing at the N-terminal end [7]. Ang A has the same affinity for the AT1 and AT2 receptor as Ang II. The ACE2 gene resides on the X chromosome in rodents and man. ACE2 has been deleted in mice (ACE2 y/− mice). Crackower et al. studied ACE2 y/− mice and showed that ACE2 is an essential regulator of cardiac function. The ACE2 y/− mice exhibited severe cardiac dilatation [8]. Gurley et al. generated the same ACE2 y/− mice and observed no cardiac abnormalities [9].

Fig. 1.

Ang 1–7 (Asp-Arg-Val-Tyr-Ile-His-Pro), which can be formed either by the carboxypeptidase activity of ACE2 on Ang II (Asp-Arg-Val-Tyr-Ile-His-Pro-Phe) or by endopeptidase cleavage of Ang I (Asp-Arg-Val-Tyr-Ile-His-Pro-Phe-His-Leu) by neprilysin (NEP), antagonizes Ang II actions on cardiovascular and renal physiology. The opposing effects of Ang II and Ang 1–7 are carried out primarily via the AT1, AT2, and Mas receptors (MAS R), respectively. Ang III (Arg-Val-Tyr-Ile-His-Pro-Phe) is the principal active peptide in the brain RAS, and its formation is regulated by aminopeptidase (AP)—as largely adapted from [2]

In this issue of J Mol Med, Wang et al. tested the clinical relevance of a partial loss of ACE2 by using female ACE2+/+ (wild type) and female ACE2+/− (heterozygous) mice [10]. Pressure overload in ACE2+/− mice resulted in greater cardiac dilation and worsening systolic and diastolic dysfunction compared to controls. These changes were associated with increased myocardial fibrosis, hypertrophy, and upregulation of deleterious genes. They performed Ang II infusion in this model and found that NADPH oxidase activity and myocardial fibrosis increased, resulting in worsening of Ang II-induced diastolic dysfunction with preserved systolic function. Also, Ang II-mediated cellular effects in cultured adult ACE2+/− cardiomyocytes and cardiofibroblasts were exacerbated. Ang II-mediated pathological signaling worsened in ACE2+/− hearts, as characterized by increase in phosphorylation of ERK1/2, JNK1/2, and STAT-3 pathways. The ACE2+/− mice showed an exacerbated pressor response with increased vascular fibrosis and stiffness. Vascular superoxide and nitrotyrosine levels were increased in ACE2+/− vessels consistent with increased vascular oxidative stress. These changes occurred with increased renal fibrosis and superoxide production. The authors contend that partial heterozygote loss of ACE2 could be sufficient to increase the susceptibility to heart disease related to pressure overload and Ang II infusion.

Oddly, when Gurley et al. infused Ang II into ACE2 y/− mice that had no ACE2, they identified exaggerated accumulation of Ang II in the kidney as expected. However, they found no role for ACE2 in the regulation of cardiac structure or function [9]. Northern blots from Ace2−/y and Ace2+/y mouse kidneys hybridized with a complementary DNA (cDNA) probe for mouse ACE2. However, ACE2 mRNA was not detected in kidney RNA from Ace2−/y mice, convincingly demonstrating that the gene deletion worked completely. Wang et al. argue that their results highlight a critical and dominant role of ACE2 in heart disease by demonstrating that a 50 % loss of ACE2 is sufficient to enhance the susceptibility to heart disease [9]. Nonetheless, Gurley et al. argue the opposite, since they demonstrated that a 100 % loss of ACE2 had hardly any effect [9]. Wang et al. also comment that a relative loss of Ang 1–7 facilitated adverse remodeling in their model [10] but do not show specific measurements of Ang 1–7 in their paper. Gurley et al. also do not quantitate Ang 1–7; however, they did measure Ang II with mass spectrometry [9]. Consistent with loss of ACE2, Ang II was increased in kidneys from ACE2-deficient mice. If Ang 1–7 were all that important, we would expect that Mas gene-deleted mice should show a dramatic cardiac phenotype. Our group showed earlier that Mas −/− mice do indeed have a cardiovascular phenotype, namely, increased blood pressure and endothelial dysfunction; however, a dramatic cardiac phenotype was not among the findings [11].

The dramatic difference in phenotypes between the two ACE2-deficient lines described by Crackower et al. [8] and Gurley et al. [9] cannot be easily explained by differences in the gene disruption methodology, as the exon encoding the active site of the enzyme was deleted in both lines. Another common cause of variable phenotypes in transgenic mouse models is a difference in genetic backgrounds. Both lines of ACE2-deficient mice were generated from embryonal stem (ES) cells derived from 129-strain mice and chimeras that were initially backcrossed to C57BL/6. The precise genetic background of the animals reported by Crackower et al. [8] was not specified but is likely to have been a random mix of the two parental lines. Wang et al. do not enlighten us further [10].

A bit disconcerting is that Wang et al. [10] fail to discuss or even to cite the report by Gurley et al. [9]. Chasing down discrepancies, disagreements, and nonreproducible results is never fun and clearly is an endeavor that will accrue no funding. However, these discrepancies are burning questions for explanations and desperately need to be pursued. A group with access to mass spectrometry for Ang products needs to obtain both ACE2 y/− models and should subject these mice to provocative maneuvers as utilized by Wang et al. [10] and Gurley et al. [9]. Breeding studies that bring both models to precisely the same genetic backgrounds should be performed. We readers need answers, not only to elucidate the role of ACE2 but also to study the importance of the Ang II breakdown products that are held to be so important by many investigators. The existence of Ang breakdown products and their meaning, if any, requires no less.

Respectfully,

Friedrich C. Luft

References

- 1.Kuba K, Imai Y, Penninger JM. Multiple functions of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and its relevance in cardiovascular diseases. Circ J. 2013;77:301–8. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-12-1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masuyer G, Schwager SL, Sturrock ED, Isaac RE, Acharya KR. Molecular recognition and regulation of human angiotensin-I converting enzyme (ACE) activity by natural inhibitory peptides. Sci Rep. 2012;2:717. doi: 10.1038/srep00717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Danilczyk U, Sarao R, Remy C, Benabbas C, Stange G, Richter A, Arya S, Pospisillik JA, Singer D, Camargo SM, et al. Essential role for collectrin in renal amino acid transport. Nature. 2006;444:1088–91. doi: 10.1038/nature05475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fournier D, Luft FC, Bader M, Ganten D, Andrade-Navarro MA. Emergence and evolution of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. J Mol Med. 2012;90:495–508. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0894-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandrasekaran B, Dar O, McDonagh T. The role of apelin in cardiovascular function and heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10:725–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Villela DC, Passos-Silva DG, Santos RAS. Alamandine: a new member of the angiotensin family. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2014;23:130–4. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000441052.44406.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jankowski V, Vanholder R, van der Giet M, Tölle M, Karadogan S, Gobom J, Furkert J, Oksche A, Krause E, Tran TN, et al. Mass-spectrometric identification of a novel angiotensin peptide in human plasma. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(2):297–302. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000253889.09765.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crackower MA, Sarao R, Oudit GY, Yagil C, Kozieradzki I, Scanga SE, Oliveira-dos-Santos AJ, da Costa J, Zhang L, Pei Y, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is an essential regulator of heart function. Nature. 2002;417:822–8. doi: 10.1038/nature00786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gurley SB, Allred A, Le TH, Griffiths R, Mao L, Philip N, Haystead TA, Donoghue M, Breitbart RE, Acton SL, et al. Altered blood pressure responses and normal cardiac phenotype in ACE2-null mice. J Clin Investig. 2006;116:2218–25. doi: 10.1172/JCI16980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang W, Patel VB, Parajuli N, Fan D, Basu R, Wang Z, Ramprasath T, Kassiri Z, Penninger JM, Oudit GY. Heterozygote loss of ACE2 is sufficient to increase the susceptibility to heart disease. J Mol Med. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00109-014-1149-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu P, Costa-Goncalves AC, Todiras M, Rabelo LA, Sampaio WO, Moura MM, Santos SS, Luft FC, Bader M, Gross V, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and elevated blood pressure in MAS gene-deleted mice. Hypertension. 2008;51:574–80. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.102764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]