Abstract

Introduction:

The causal direction of the relationship between sleep disturbance and drug cravings is unknown. Based on resource depletion literature, we hypothesized that sleep difficulties lead to cravings. We tested whether sleep quality predicts craving at the within- or between-person level, with perceived willpower as a multilevel mediator.

Methods:

We used ecological momentary assessments (EMA) to compare two models of temporal precedence. Participants in addiction treatment (N = 122) were sent four surveys each day for three weeks. Participants rated previous night’s sleep quality and level of cravings and willpower.

Results:

The between- (β = −.18, SE = .06) and within-person (β = −.02, SE = .02) effects of maximum daily craving on sleep quality were significant, as were the between- (β = −.33, SE = .08) and within-person (β = −.08; SE=.03) effects of daily sleep quality on maximum daily cravings. In the mediation analysis of the indirect effect of sleep quality on cravings via willpower, both the indirect effect for the between-person pathway (β = −.27, SE = .07) and the indirect within-person pathway (β = −.01, SE = .01) were significant.

Conclusions:

EMA methodology allowed for disentanglement of the temporal relationship between sleep and cravings. We found support for the resource depletion hypothesis, operationalized by linking sleep quality to cravings via willpower. However, the magnitude of the association between sleep quality and cravings was stronger at the between-person level, suggesting a potentially cumulative effect of poor sleep on cravings. These results suggest that clinicians should ask patients about chronic sleep problems, as these may pose a risk for relapse.

Keywords: Addiction, Sleep, Craving, Willpower, Ecological Momentary Assessment, Resource depletion

Studying antecedents to relapse episodes is important, as this knowledge may inform possible interventions. Drug or alcohol craving, or experiencing an urge to use, is one risk factor for relapse: Evidence supports a strong link between cravings and subsequent use of illegal and/or illicit substances (Serre, Fatseas, Swendsen, & Auriacombe, 2015). However, there is a great deal of within- and between- person variation with respect to the probability of relapse following craving (Serre et al., 2015). Identifying contextual factors that predict cravings and relapse would be beneficial. So far, the field has focused on both internal (i.e., affect, Serre et al., 2015) and external (i.e., time of day, Ramirez & Miranda, 2014; day of week, Lane, Carpenter, Sher, & Trull, 2016; and location, Lane et al., 2016) contextual predictors of craving, but more can be done to bolster the literature on this topic.

Sleep is an under-explored correlate of drug or alcohol cravings with promising intervention potential. There is a known association between sleep problems and cravings (Lydon-Staley et al., 2017), but the causal direction is unknown: people struggling with cravings may have difficulty sleeping, or people who have difficulty sleeping may have more subsequent cravings. There is some evidence that nicotine cravings can negatively impact sleep: Riemerth, Kunze, and Groman (2009) found evidence that approximately 20 percent of patients taking part in a smoking cessation program awoke in the night and had to smoke a cigarette before returning to sleep. Riemerth and colleagues deemed this symptom “nocturnal sleep-disturbing nicotine craving” (Riemerth et al., 2009; Rieder, Junze, Groman, Kiefer, & Schoberberger, 2001), and this construct may theoretically be present for other substances of addiction as well.

However, another theory suggests that the causal pathway leads from sleeping difficulties to cravings because sleep deficits are linked with resource depletion, which may in turn give rise to more cravings. The theory of resource depletion posits that self-regulation draws upon limited cognitive resources; prolonged effortful regulation depletes the cognitive resources, leading to “self-regulatory failures” (Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Muraven, & Tice, 1998). We hypothesized that sleep disturbance can influence one’s self-regulatory capacity, thereby lowering the threshold for resource depletion. Sleep disruption has been linked with alcohol consumption (Christiansen, Cole, & Field, 2012), binge eating (Trace et al., 2012), and self-harm (Wong, Brower, & Zucker, 2011). Furthermore, sleep disruption has been linked to resource depletion more directly: Barber, Munz, Bagsby, and Powell (2010) found that consistent sleep practices, not just a sufficient amount of sleep, decreased psychological strain (their measure of resource depletion). However, it is important to highlight that there is also evidence that sleep disruption is not directly linked to resource depletion (Vohs, Glass, Maddox, & Markman, 2011). Further research investigating the relationship between sleep and resource depletion is warranted.

Thus, we hypothesized that sleep may play an important role in predicting drug cravings and use, with decreased self-reported willpower to resist temptations as a potential mediator of this relationship, our operationalization of reduced self-regulatory capacity. Importantly, no studies have provided direct empirical evidence to support the hypothesized causal pathway linking sleep with cravings or relapse; this is a major gap in the literature.

The present study

Without the ability to randomly assign sleep quality, we must rely on temporal precedence to infer causation (Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002). To obtain robust measures of temporality, we used ecological momentary assessment (EMA) methodology. EMA is a method for collecting data in real-time and in variety of ecologically-valid conditions or states throughout a day (Stone & Shiffman, 1994). EMA allows researchers to inquire about a specific symptom or construct in the moment, rather than retrospectively, which is beneficial when studying topics like mood or drug cravings (Shiffman, 2009). For instance, previous studies have shown that participants tend to overestimate the degree to which they experience positive emotions and underestimate the degree to which they experience negative emotions in retrospective surveys compared to their responses on momentary surveys (Ebner-Priemer & Trull, 2009). Because it provides intensive repeated measures, EMA provides the opportunity to parse cross-sectional between-person processes from longitudinal within-person processes (Curran & Bauer, 2011). This is essential to our ability to establish directionality in the association between sleep quality and cravings.

In the only existing EMA study of sleep quality and drug cravings, Lydon-Staley and colleagues (2017) sampled 68 patients in residential treatment for nonmedical use of prescription drugs. They found that sleep quality was related to next-day cravings for prescription drugs, with lower positive affect (but not higher negative affect) partially mediating this effect. While this study provides important evidence about the mechanism of the association between sleep quality and cravings, the authors did not take full advantage of the method’s ability to provide strong support for the hypothesized causal direction because the study did not consider nightly sleep quality as an outcome of daily cravings. We seek to extend this body of work by testing the temporal relationship between craving and sleep problems. We will then test the hypothesis that lower willpower mediates the relationship between sleep problems and subsequent cravings, consistent with the resource-depletion hypothesis.

Methods

Participants

We recruited 128 participants from inpatient and outpatient addiction recovery programs in the Triangle area of North Carolina (including Wake, Durham, Orange, and Chatham counties). We recruited participants via their clinics and through direct mailings to those whose UNC healthcare records indicated that they might be eligible to participate in the study. Participants were screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria by phone before enrollment in the study. To satisfy enrollment criteria, participants must have been at least 18 years of age, be actively receiving treatment for a substance use disorder, have been abstinent from the substance for which they were receiving treatment for less than 12 months, not have been pregnant, and must have had regular access to a private mobile phone. Additionally, we excluded 6 participants from the present analyses for not completing any of the daily EMA surveys.

Of the 122 participants included in the analyses, 61.40% described themselves as White and 35.09% described themselves as Black. 4.24% described themselves as Hispanic. Participants had an average age of 41.70 years (SD = 11.00; range 22–68), and were 74.79% female. There were more females in our sample because one of the clinics from which we recruited was a women-only clinic. In terms of highest level of education, 15.52% of the sample never completed high school, 26.72% had completed high school, 37.07% had completed some college, and 20.69% had an Associate’s degree or higher.

The majority of participants (55.74%, n = 68) were poly-drug users. The substance(s) that participants were treated for at the time of the study are as follows (note that these categories are not mutually exclusive): alcohol (52.46%, n = 64), cocaine (41.80%, n = 51), heroin (30.33%, n = 37), prescription opiates (28.69%, n = 35), methamphetamine (7.38%, n = 9), cannabis (22.95%, n = 28), and “other,” including benzodiazepines and dextromethorphan (1.64%, n = 2).

We recruited participants who had used substances within the past 12 months, but who were actively enrolled in a recovery program because we were interested in studying the process of recovery at an early stage. Forty-five participants (36.89%) were enrolled in inpatient programs at the time of recruitment and 77 (63.11%) were enrolled in outpatient programs. Fifty-three (43.44%) participants received some sort of medication management related to substance use recovery. We retained participants who changed or left treatment programs during the course of the study.

Procedure

After consent procedures, participants were instructed to fill out our baseline survey, and trained research assistants then explained the EMA protocol in person. For each week-long measurement burst (most often beginning the day after completing the baseline survey, but sometimes delaying further based on participants’ schedule/ preference), participants received four brief surveys each day for seven days. These surveys were delivered via text message (12.30%, n = 15) or automated phone calls (87.70%, n = 107), depending on the participants’ preference. Participants had one hour to respond to the automated phone calls and were not called back if they missed a daily survey, but the automated system would leave a voicemail. We instructed participants who received the text message prompts to skip a missed prompt if they had already received the next survey. Each of the three measurement bursts were spaced at least six weeks apart (spaced further if the study team had difficulty getting in touch with a participant or if they requested to start the next measurement burst at a later date (mean # weeks spaced = 6.69, SD = 3.00). Participants were compensated at the end of each measurement burst in accordance with their level of adherence to the surveys. On average, participants completed 19.59 (SD = 7.42) surveys during burst 1, 20.43 (SD = 6.80) during burst 2, and 21.68 (SD = 6.47) during burst 3. Of the original 122 participants included in the analyses, 97 completed the second burst and 77 completed the third burst.

Measures

Because participant burden is a concern for EMA studies, one-item assessments were used for all measures that were obtained through EMA.

Sleep quality.

Participants were asked to describe their sleep quality (regarding the previous night’s sleep) on the first of each daily survey. Response options ranged from 0 (Terrible) to 4 (Great). We used a single-item sleep quality measure to reduce participant burden: such measures have demonstrated favorable psychometric properties (Lydon-Staley et al., 2017; Cappelleri et al., 2009).

Momentary cravings for drugs.

Participants were asked to respond to their level of craving at the moment on each of the four daily surveys. Response choices ranged from 0 (Not at all) to 4 ([Drugs or alcohol is/are] all I can think about). Several other EMA studies have used a single-item measure to assess cravings in addicted populations (Freedman, Lester, McNamara, Milby, & Schumacher, 2006; Hopper et al., 2006; Shiffman et al., 2002). We calculated the maximum reported craving level for each day, since cravings have been shown to fluctuate within days (Chandra, Scharf, & Shiffman, 2011) and to decline over time in general (Lydon-Staley et al., 2017; Galloway et al. 2010). We were concerned that there would be reduced variation in cravings across bursts, and we hypothesized that peak craving experiences would be more predictive than average craving levels.

Momentary willpower.

We used a single-item measure that was developed by Hoyle & Davisson (in press) for capturing momentary inhibitory self-control in EMA studies. Participants were asked to indicate how much willpower they felt they had to resist temptations in the moment they were taking each of the daily surveys. Responses ranged from 0 (No willpower) to 4 (Willpower at its peak). We created day-level averages of these responses.

Covariates.

Because sleep and craving patterns may differ on weekends versus weekdays, we included an effects-coded, binary ‘weekend’ indicator. To control for mean changes in cravings, willpower, and sleep which may occur across measurement bursts, we included nominal indicators of burst that were effects coded with burst 1 as the base group. Burst was coded nominally because descriptive analyses suggested that burst was non-linearly associated with self-reported willpower. Finally, we controlled for the potentially confounding effects of gender (effects coded with male as the base group), age (mean centered), and the primary substance(s) for which participants are receiving treatment. Primary substance was indexed using effects-coded indicators for alcohol, opiates, and cocaine, with the polysubstance group as the base group. Alcohol was indicated as a primary substance only for participants who were not receiving treatment for illicit substances. Participants who reported use of alcohol or marijuana in addition to either cocaine or opiates (but not both) were not included in the polysubstance group.

Data Analysis

To facilitate analyses of between- and within-person effects, we computed person-mean sleep quality and person-mean cravings to measure between-person variation (these variables are represented as and in Equations 1 and 2), and we subtracted these person-means from the daily measures to create orthogonal, person-mean-centered sleep quality and cravings that measured within-person variation (represented as and ; Curran & Bauer, 2011). Multilevel models were used to assess simultaneously the between-person association between sleep quality and cravings (β6 in both equations), as well as the prospective, within-person effects of sleep quality on subsequent cravings, and vice versa (in both equations). All predictors were standardized before analysis for interpretation of effect sizes. Standardization permits us to interpret effect sizes without changing the nature or the pattern of significance of the estimated effects. Each model controlled for age, gender, measurement burst, weekend versus weekday, primary substance, and lagged sleep quality (Equation 1) or craving (Equation 2). These lagged variables were missing for the first day of each measurement burst. We estimated a random intercept (u0i in both equations) to allow for between-person variation in average sleep quality and cravings, and random effects of sleep quality and cravings (u1i and u2i in both equations) to allow for between-person variation in these effects. Random effects were permitted to covary freely.

For each outcome (daily sleep quality and maximum daily cravings), we estimated a series of three models. First, we estimated a baseline model that included covariates only (gender, age, primary substance, burst, weekend, and the lagged outcome). Next, we included main effects of the within-person and between person predictors. Finally, we tested an exploratory moderation model that included interactions between burst and primary substance, burst and within-person sleep or maximum craving, and an interaction between the between-person and within-person sleep or craving predictors. The full moderation models are shown in Equations 1 (for sleep quality) and 2 (for maximum cravings). The covariate-only and main effects models are nested within the full model.

| (1) |

| (2) |

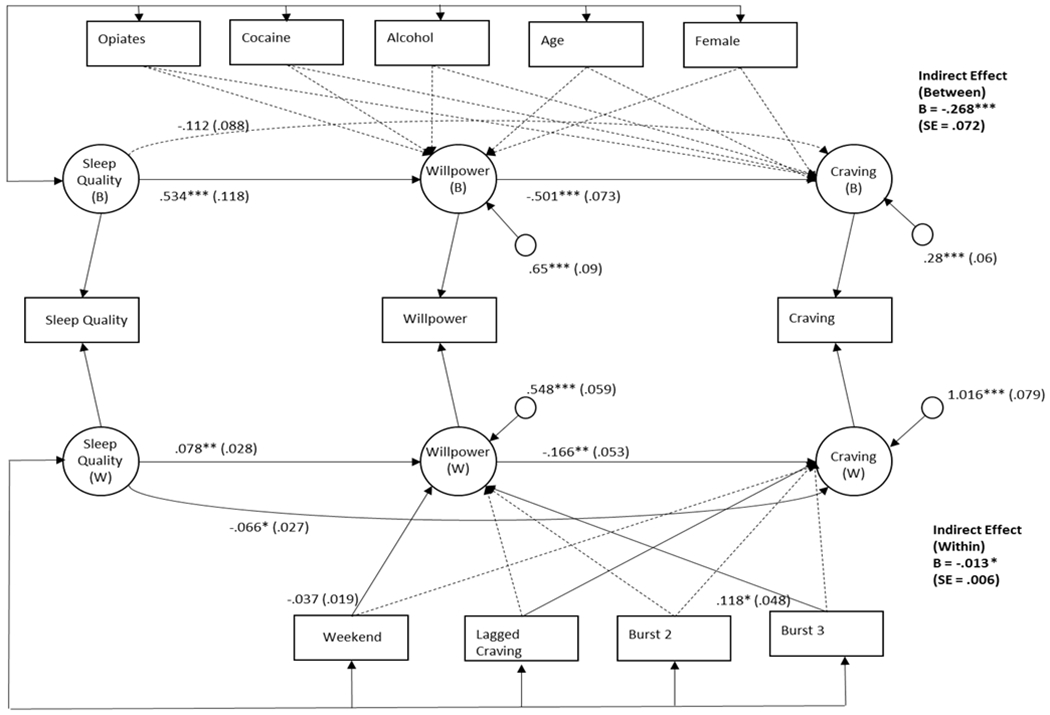

Next, we used a 1-1-1 multilevel mediation model from Preacher, Zyphur, & Zhang’s (2010) SEM framework to investigate whether self-reported willpower mediates the relationship between sleep quality and cravings at either the within-person or between-person level. See Figure 1 for a depiction of this model.

Figure 1.

Path diagram of the multilevel mediation model assessing within (W; bottom) - and between (B; top) - person mediational pathways from sleep quality to cravings via willpower. Measured variables are represented with rectangles and latent (i.e., random) variables are represented with circles. Parameter estimates are listed with standard errors in parentheses. Nonsignificant paths are dotted and significant paths are solid. Estimates are not reported for nonsignificant covariate effects. * p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001

Results

Descriptive Statistics

See Table 1 for descriptive statistics for craving and sleep variables included in this analysis.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| Overall | Burst 1 (N= 122) | Burst 2 (N= 97) | Burst 3 (N= 77) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M (SD) | Range | M (SD) | Range | M (SD) | Range | M (SD) | Range |

| Cravings | ||||||||

| Aggregatea | .59 (.91) | 0-4 | .65 (.93) | 0-4 | .57 (.92) | 0-4 | .53 (.88) | 0-4 |

| Person Mean | .65 (.82) | 0-4 | .65 (.82) | 0-4 | 65 (.82) | 0-4 | .65 (.82) | 0-4 |

| Person Mean-Centereda | 0 (.57) | −2.14-2.82 | .05 (.59) | −1.90-2.82 | −.01 (.54) | −2.08-2.58 | −.06 (.88) | 0-4 |

| Sleep Quality | ||||||||

| Aggregate | 2.11 (1.05) | 0-4 | 2.09 (1.06) | 0-4 | 2.11 (1.05) | 0-4 | 2.13 (1.08) | 0-4 |

| Person Mean | 2.08 (.63) | .61-3.42 | 2.08 (.63) | .61-3.42 | 2.08 (.63) | .61-3.42 | 2.08 (.63) | .61-3.42 |

| Person Mean-Centered | 0 (.87) | −2.82-2.50 | .01 (.90) | −2.82-2.50 | .01 (.85) | −2.57-2.35 | −.04 (.86) | −2.82-2.50 |

| Willpower | ||||||||

| Aggregateb | 2.62 (1.05) | 0-4 | 2.54 (.99) | 0-4 | 2.59 (1.11) | 0-4 | 2.77 (1.06) | 0-4 |

| Person Mean | 2.58 (.91) | 0-4 | 2.58 (.91) | 0-4 | 2.58 (.91) | 0-4 | 2.58 (.91) | 0-4 |

| Person Mean-Centeredb | 0 (.63) | −3.38-3.23 | −.06 (.64) | −2.90-3.23 | −.01 (.64) | −3.35-2.23 | .11 (.59) | −2.33-2.10 |

Note. Person mean is constant across bursts.

Burst 3 mean is significantly lower than Burst 1 mean

Burst 3 mean is significantly higher than mean for Bursts 1 and 2

Maximum Daily Cravings as a Predictor of Subsequent Sleep Quality

Our first model (Table 2) examined the predictive effects of previous day’s person-mean-centered cravings on daily sleep quality and the person-mean effect of average sleep quality on daily sleep quality. There were no within-person effects of cravings on subsequent sleep quality (β = −.015, SE = .022); however, the between-person effect of craving on sleep quality was significant (β = −.176, SE = .057), indicating that people who tended to experience higher amounts of cravings tended to experience worse sleep quality. Whereas the sample-size adjusted BIC suggested that the addition of cravings to the model resulted in improved fit, fit deteriorated between the main effects model and the full moderation model. Only one interaction term was statistically significant: individuals receiving treatment for alcohol only exhibit less of a negative within-person effect of cravings on sleep quality. When we probed the effect of lagged cravings on sleep quality for individuals receiving treatment for alcohol and for individuals not receiving treatment for alcohol, we found nonsignificant effects trending in the opposite direction (β = .103, SE = .083 for individuals receiving treatment for alcohol; β = −.104, SE = .106 for individuals receiving treatment for other substances).

Table 2.

Results from mixed models predicting daily sleep quality from maximum cravings

| Covariates only | Main effects model | Full moderation model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est | SE | Est | SE | Est | SE | |

| Fixed Effects | ||||||

| Intercept | 1.528*** | .135 | 1.766*** | .151 | 1.864*** | .196 |

| Female | −.117* | .058 | −.112* | .056 | −.116* | .059 |

| Age | .001 | .005 | .001 | .005 | .002 | .005 |

| Weekend | .068** | .025 | .070** | .025 | .065** | .025 |

| Alcohol | .176 | .152 | .133 | .144 | −.180 | .215 |

| Opiates | .324* | .137 | .293* | .127 | .235 | .204 |

| Cocaine | .334* | .141 | .251 | .133 | .186 | .206 |

| Burst2 | .004 | .033 | .008 | .034 | .008 | .034 |

| Burst3 | −.015 | .039 | −.013 | .040 | −.013 | .040 |

| Lagged sleep quality | .196*** | .034 | .187*** | .035 | .187*** | .035 |

| Person mean craving | −.176** | .057 | −.256* | .119 | ||

| Person mean craving * Alcohol | .025 | .077 | ||||

| Person mean craving * Opiates | −.079 | .076 | ||||

| Person mean craving * Cocaine | .054 | .078 | ||||

| Person mean centered lagged craving | −.015 | .022 | −.021 | .090 | ||

| Person mean craving * Person mean centered lagged craving | .004 | .038 | ||||

| Burst2 * Person mean centered lagged craving | −.011 | .036 | ||||

| Burst3 * Person mean centered lagged craving | −.016 | .039 | ||||

| Alcohol * Person mean centered lagged craving | .293* | .145 | ||||

| Opiates * Person mean centered lagged craving | .048 | .150 | ||||

| Cocaine * Person mean centered lagged craving | .022 | .194 | ||||

| Model Fit | ||||||

| n-Adjusted BIC | 4100.968 | 4089.839 | 4118.195 | |||

Note. Not shown: we estimated an unstructured random effects matrix with random variance for the intercept, the effect of lagged sleep, and the effect of lagged, person-mean centered cravings. Female is effects coded with male as the base group; weekend is effects coded with weekday as the base group; age is mean centered; primary substances are dummy coded with “polysubstance/other” as the reference group; burst is effects coded with burst1 as the base group; all other variables are standardized. Est = point estimate; SE = standard error

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Sleep Quality as a Predictor of Next Day’s Cravings

Our second model (Table 3) examined the between-person effect of person-mean sleep quality on average cravings and the within-person, predictive effects of person-mean-centered sleep quality on subsequent cravings. Again, the between-person effect was significant (β = −.329, SE = .078), indicating that people who tended to have better sleep quality tended to experience lower average craving ratings. The within-person effect of sleep quality on cravings was also significant, as hypothesized (β = −.083, SE = .028). This indicates that on days when people report worse sleep quality, they tend to experience a higher maximum craving level. The sample-size adjusted BIC indicated that the main effect model was an improvement over the covariates-only model, but the fit of the full moderation model was worse than the main effects only model. None of the exploratory interactions terms were significant.

Table 3.

Results from mixed models predicting daily maximum cravings from sleep quality

| Covariates only | Main effects model | Full moderation model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est | SE | Est | SE | Est | SE | |

| Fixed Effects | ||||||

| Intercept | .775*** | .127 | 1.397*** | .206 | 1.455*** | .334 |

| Female | .004 | .064 | −.041 | .060 | −.034 | .062 |

| Age | −.003 | .005 | −.002 | .005 | −.002 | .005 |

| Weekend | −.027 | .026 | −.025 | .026 | −.025 | .026 |

| Alcohol | −.096 | .168 | −.036 | .165 | −.722 | .509 |

| Opiates | −.118 | .151 | .023 | .143 | .095 | .552 |

| Cocaine | −.258 | .142 | −.106 | .135 | .049 | .434 |

| Burst2 | .048 | .040 | .034 | .040 | .037 | .041 |

| Burst3 | −.080* | .037 | −.078* | .040 | −.084* | .040 |

| Lagged cravings | .289*** | .049 | .286*** | .052 | .275*** | .053 |

| Person mean sleep quality | −.329*** | .078 | −.360* | .154 | ||

| Person mean sleep quality * Alcohol | .346 | .259 | ||||

| Person mean sleep quality * Opiates | −.029 | .237 | ||||

| Person mean sleep quality * Cocaine | −.058 | .189 | ||||

| Person mean centered sleep quality | −.083** | .028 | −.104 | .106 | ||

| Person mean sleep quality * Person mean centered sleep quality | −.016 | .048 | ||||

| Burst2 * Person mean centered sleep quality | −.013 | .049 | ||||

| Burst3 * Person mean centered sleep quality | −.016 | .051 | ||||

| Alcohol * Person mean centered sleep quality | .102 | .078 | ||||

| Opiates * Person mean centered sleep quality | .033 | .081 | ||||

| Cocaine*Person mean centered sleep quality | .092 | .079 | ||||

| Model Fit | ||||||

| n-Adjusted BIC | 4927.425 | 4599.095 | 4631.385 | |||

Note. Not shown: we estimated an unstructured random effects matrix with random variance for the intercept, the effect of lagged cravings, and the effect of person-mean centered sleep quality. Female is effects coded with male as the base group; weekend is effects coded with weekday as the base group; age is mean centered; primary substances are dummy coded with “polysubstance/other” as the reference group; burst is effects coded with burst1 as the base group; all other variables are standardized. Est = point estimate; SE = standard error

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Associations between Sleep Quality, Willpower, and Cravings

Results from the mediational model that was used to test our hypothesis that sleep quality affects cravings via willpower are shown in Figure 1. The indirect effect for the between-person mediational pathway is small-to-moderate (β = −.268, SE = .072). This indicates that people who tend to have worse sleep quality also tend to have lower willpower, and people who tend to have lower willpower tend to have more cravings. When willpower is included as a mediator, the direct effect of sleep quality on cravings is no longer significant at the between-person level.

The indirect within-person mediational pathway was statistically significant, but with a very small effect size (β = −.013, SE = .006). This means that on days when people have higher-than-average sleep quality, they tend to report higher-than-average willpower, and on days when they report higher-than-average willpower, they also tend to report lower-than-average levels of cravings. The direct effect of within-person sleep quality on subsequent maximum cravings was still significant after accounting for willpower, indicating other intervening variables may account for the observed negative within-person association between sleep quality and cravings. Of note, when we used mean level cravings for all analyses, we did not obtain a significant direct effect of person-mean-centered sleep quality on cravings (β = −.02, SE = .02), but did find a significant, but small, indirect effect (β = −.01, SE = .00). All other obtained results were similar when we used mean versus maximum level of cravings.

Discussion

The use of EMA methodology enabled us to disentangle between- and within-person variance in the association between sleep quality and cravings, and to quantify the bidirectional effects of sleep on cravings and vice versa. We found support for the resource depletion hypothesis, which was operationalized using a multilevel mediation model linking sleep quality to cravings via willpower; however, the association between sleep quality and cravings was much more robust at the between-person level.

Average sleep quality strongly predicted a person’s tendency to experience cravings in our sample, and the mediational model suggested that willpower may explain this association. Since the between person effect was significant (i.e. since the people in our sample who had worse average, overall ratings of sleep quality tended to report lower willpower and higher cravings), poor sleep quality’s effect on resource depletion may be cumulative such that one night of worse-than-average sleep may have a small effect on willpower, but many nights of poor sleep may have dramatic effects. Dinges and colleagues (1997) found that participants’ alertness and reaction time was impaired in an escalating fashion after seven consecutive nights of limited sleep (where participants received approximately 5 hours of sleep each night), and Barber et al. (2010) found that consistent sleep patterns decreased psychological strain (their measure of resource depletion). Perhaps a similar mechanism occurred in our sample.

Our finding of null or small within-person effects of sleep quality on cravings and large between-person effects are at odds with Lydon-Staley et al.’s (2017) finding that day-level sleep quality reduced next-day cravings, but that person-level sleep quality was unrelated to cravings. There were at least two differences between our studies. First, the samples were different. Whereas Lydon-Staley and colleagues sampled 68 inpatients at the very early stages of their recovery (substance detoxification occurred 10–14 days prior to the start of their study), the 122 participants in the current study were more progressed in their recovery and many were receiving outpatient care. Furthermore, the participants in the prior study were all receiving treatment for abuse of prescription drugs; participants in the current study were receiving treatment for a range of substances. The third difference is that we used a more conservative test of the associations between craving and sleep quality by controlling for the lagged dependent variable in all models.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study used a broad, subjective measure of sleep quality, and no other sleep parameters (sleep duration, wake time, sleep time, etc.) were assessed during this study. Future studies could implement a more detailed measure of sleep disturbance, such as the Leeds Sleep Evaluation Questionnaire, which examines getting to sleep, staying asleep, quality of sleep, and behavior after wakening (Parrott & Hindmatch, 1978). Perhaps there are certain aspects of sleep quality that are more directly related to resource depletion and should be studied further. Ambulatory accelerometry may also offer a more objective measure of sleep quality that could help supplement or validate self-report measures (Wrzus et al., 2012). Similarly, in the interest of brevity for our EMA surveys, we relied on single-item self-reported measures of cravings and willpower. Use of single-item measures reduces reliability, and results in downwardly biased parameter estimates by extension.

Because they were assessed concurrently, we were not able to assess temporality of the ‘b’ path of the within-person mediation model, which linked person-mean-centered willpower with person-mean-centered cravings. Similarly, we cannot draw strong causal conclusions about the between-person associations that we observed. Nevertheless, the most theoretically plausible direction of effects is the one consistent with the resource depletion hypothesis (i.e., that sleep quality predicts worse subsequent cravings), and our results do support this theory. Indeed, in our sample, willpower mediated the association between sleep quality and cravings, and since we tested both temporal directions and controlled for lagged outcome, we can make a reasonable inference about the direction of the relationship between sleep quality and cravings.

There is evidence that some published experimental paradigms testing resource depletion (also called “ego depletion”) have failed to replicate across studies, and there have been inconsistencies in observed effect sizes across studies with similar protocols (Hagger et al., 2016). Given these recent developments in the depletion literature, replication studies would be beneficial.

This study was motivated with the goal of identifying individual and situational predictors of relapse. Cravings were used as a proxy for relapse risk. Particularly in light of our finding that cumulative sleep quality is predictive of average cravings, future studies should investigate sleep quality as a predictor of actual drug or alcohol use amongst individuals in recovery, above and beyond self-reported cravings.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that cumulative sleep dysfunction is strongly related to persistent craving experiences. These findings suggest that individuals in addiction recovery who are experiencing consistently poor sleep quality may have a heightened risk for relapse. Clinicians should assess patient sleep quality, and sleep solutions should be offered to individuals experiencing consistently poor sleep quality.

Acknowledgements:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health through grant funding awarded to Dr. Gottfredson (K01 DA035153). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Barber LK, Munz DC, Bagsby PG, & Powell ED (2010). Sleep consistency and sufficiency: Are both necessary for less psychological strain? Stress and Health, 26, 186–193. doi: 10.1002/smi.1292 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Bratslavsky E, Muraven M & Tice DM (1998). Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(5), 1252–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappelleri JC, Bushmakin AG, McDermott AM, Sadosky AB, Petrie CD, & Martin S (2009). Psychometric properties of a single-item scale to assess sleep quality among individuals with fibromyalgia. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 7(54), doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra S, Scharf D, & Shiffman S (2011). Within-day temporal patterns of smoking, withdrawal symptoms, and craving. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 117, 118–125. doi: doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.12.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen P, Cole JC & Field M (2012). Ego depletion increases ad-lib alcohol consumption: Investigating cognitive mediators and moderators. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 20(2), 118–128. doi: 10.1037/a0026623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, & Bauer DJ (2011). The disaggregation of within-person and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annual review of psychology, 62, 583–619, doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinges DF, Pack F, Williams K, Gillen KA, Powell JW, Ott GE, Aptowicz C, & Pack AI (1997). Cumulative sleepiness, mood disturbance, and psychomotor vigilance performance decrements during a week of sleep restricted to 4-5 hours per night. Sleep, 20(4), 267–27.7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebner-Priemer U, Trull T (2009). Ecological momentary assessment of mood disorders and mood dysregulation. Psychological Assessment, 21(4), 463–475. doi: 10.1037/a0017075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman MJ, Lester KM, McNamara C, Milby JB, & Schumacher JE (2006). Cell phones for ecological momentary assessment with cocaine-addicted homeless patients in treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 30, 105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway GP, Singleton EG, Buscemi R, Baggot MJ, Dickerhoof RM, & Mendelson JE (2010). An examination of drug craving over time in abstinent methamphetamine users. The American Journal on Addictions, 19, 510–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00082.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagger MS, Chatzisarantis NLD, Alberts H, Anggono CO, Batailler C, Birt AR, … Zwienenberg M (2016). A multilab preregistered replication of the ego-depletion effect. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(4), 546–573. doi: 10.1177/1745691616652873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopper JW, Su Z, Looby AR, Ryan ET, Penetar DM, Palmer CM, & Lukas SE (2006). Incidence and patterns of polydrug use and craving for ecstasy in regular ecstasy users: An ecological momentary assessment study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 85, 221–235. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle RH & Davisson EK (in press). Measurement of self-control by self-report: Considerations and recommendations In de Ridder D, Adriaanse M, & Fujita K (Eds.), Handbook of self-control in health and well-being. New York: Routledge [Google Scholar]

- Lane SP, Carpenter RW, Sher KJ, & Trull TJ (2016). Alcohol craving and consumption in borderline personality disorder: When, where, and with whom. Clinical Psychological Science, 4(5), 775–792. doi: 10.1177/2167702615616132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydon-Staley DM, Cleveland HH, Huhn AS, Cleveland MJ, Harris J, Stankoski D, Deneke E, Meyer RE, & Bunce SC (2017). Daily sleep quality affects drug craving, partially through indirect associations with positive affect, in patients in treatment for nonmedical use of prescription drugs. Addictive Behaviors, 65, 275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.08.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott AC & Hindmarch I (1978). Factor analysis of a sleep evaluation questionnaire. Psychological Medicine, 8(2), 325–329. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700014379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Zyphur MJ, & Zhang Z (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15(3), 209–233. doi: 10.1037/a0020141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez J, & Miranda R Jr. (2014). Alcohol craving in adolescents: Bridging the laboratory and natural environment. Psychopharmacology, 231, 1841–1851. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3372-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieder A, Kunze U, Groman E, Kiefer I, & Schoberberger R (2001). Nocturnal sleep-disturbing nicotine craving: A newly described symptom of extreme nicotine dependence. Acta Med Austriaca, 28, 21–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemerth A, Kunze U, & Groman E (2009). Nocturnal sleep-disturbing nicotine craving and accomplishment with a smoking cessation program. Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift, 159, 47–52. doi: 10.1007/s10354-008-0640-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serre F, Fatseas M, Swendsen J, & Auriacombe M (2015). Ecological momentary assessment in the investigation of craving and substance use in daily life: A systematic review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 148, 1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR, Cook TD, & Campbell DT (2002). Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S (2009). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in studies of substance use. Psychological assessment, 21(4), 486–497. doi: 10.1037/a0017074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Gwaltney CJ, Balabanis MH, Liu KS, Paty JA, Kassel JD, Hickcox M, & Gnys M (2002). Immediate antecedents of cigarette smoking: An analysis from ecological momentary assessment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111(4), 531–545. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.111.4.531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, & Shiffman S (1994). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in behavioral medicine. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 16(3), 199–202. [Google Scholar]

- Trace SE, Thornton LM, Runfola CD, Lichtenstein P, Pedersen NL & Bulik CM (2012). Sleep problems are associated with binge eating in women. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 45, 695–703. doi: 10.1002/eat.22003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vohs KD, Glass BD, Maddox WT, & Markman AB (2011). Ego depletion is not just fatigue: evidence from a total sleep deprivation experiment. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2(2), 166–173. doi: 10.1177/1948550610386123 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MM, Brower KJ, & Zucker RA (2011). Sleep problems, suicidal ideation, and self-harm in adolescence. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 45, 505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.psychires.2010.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrzus C, Brandmaier AM, von Oertzen T, Muller V, Wagner GG, & Riediger M (2012). A new approach for assessing sleep duration and postures from ambulatory accelerometry. PLoS One, 7(10), 1–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]