Abstract

Background Colorectal cancer is the most commonly occurring cancer in Germany, and the second and third most commonly diagnosed cancer in women and men, respectively. In this context, evidence-based guidelines positively impact the quality of treatment processes for cancer patients. However, evidence of their impact on real-world patient care remains unclear. To ensure the success of clinical guidelines, a fast and clear provision of knowledge at the point of care is essential.

Objectives The objectives of this study are to model machine-readable clinical algorithms for colon carcinoma and rectal carcinoma annotated by Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) based on clinical guidelines and the development of an open-source workflow system for mapping clinical algorithms with patient-specific information to identify patient's position on the treatment algorithm for guideline-based therapy recommendations.

Methods This study qualitatively assesses the therapy decision of clinical algorithms as part of a clinical pathway. The solution uses rule-based clinical algorithms, which were developed based on the corresponding guidelines. These algorithms are executed on a newly developed open-source workflow system and are visualized at the point of care. The aim of this approach is to create clinical algorithms based on an established business process standard, the Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN), which is annotated by UMLS terminologies. The gold standard for the validation process was set by manual extraction of clinical datasets from 86 rectal cancer patients and 89 colon cancer patients.

Results Using this approach, the algorithm achieved a precision value of 87.64% for colon cancer and 84.70% for rectal cancer with recall values of 87.64 and 83.72%, respectively.

Conclusion The results indicate that the automatic positioning of a patient on the decision pathway is possible with tumor stages that have a less complex clinical algorithm with fewer decision points reaching a higher accuracy than complex stages.

Keywords: clinical decision support system, decision support algorithm, clinical practice guidelines, colorectal cancer, oncology

Background and Significance

Colorectal cancer is one of the most common cancers in Western countries. 1 2 In addition to lifestyle and eating habits, genetic predisposition contributes to disease development. The prognosis of colorectal cancer—in terms of recurrence-free survival, overall survival, and quality of life—is affected by the following three groups of factors: tumor-specific, therapy-associated, and patient-dependent factors. 3 4 Guidelines summarize the clinical experience and scientific evidence, weigh conflicting points of view against one another, and define the current recommended diagnostic and therapeutic procedures for a specific disease. Guidelines also define standards of care in medical practice to facilitate effective and appropriate health care. 5 Evidence-based guidelines have been proven to positively impact the quality of health care treatment processes. 6 Nevertheless, their impact on patient care remains limited. 7 Guidelines are published in guideline databases or journals that are freely accessible to medical societies. However, therapeutic adherence to these guidelines limits their impact on routine patient care in real-world settings. 8 The relevance of a clinical guideline demands a fast and clear provision of knowledge at the point of care for all treating physicians. 7 9 10 There are different levels of integration for the extent to which guidelines can be linked with an electronic health record (EHR). 11 These levels can be measured by the extent to which a guideline is interlinked with patient-related processes. 12 Another possibility for dissemination is the transfer of the guideline recommendations into a surgical treatment standard. Clinical decision pathways and algorithms translate the abstract guideline recommendations into concrete clinical operation procedures. 13 Hence, knowledge extracted from patient data are consistently presented at the human-machine interface. Based on a patient's EHR, appropriate sections of a formalized guideline can be assigned and displayed using common terminology. The next suitable treatment recommendation can be provided based on the patient's current status on the clinical path. To assign the correct patient position on the clinical decision path, evidence-based knowledge from the guidelines must be linked to patient-related data, and visualized at the point of care. The goal is the automatic recommendation of a guideline-based therapy through properly positioning patients on the clinical path. Based on this background, we used a generic approach, not limited to any disease, to establish an automatic clinical decision support system for patients with colorectal cancer based on their EHR.

Related Research

Several studies have already been performed to support decision-making in oncological cancer diseases with the aim of optimizing treatment quality and providing therapy recommendations. Different approaches pursue the idea of monitoring a patient on a clinical pathway and determining the patient's individual position within a pathway to provide knowledge at the point of care and to provide clinical guidelines as real-time decisions. 11 14 To improve the management of chronic conditions, Lasorsa et al have addressed specific psychological aspects to provide patients with a comprehensive and personalized solution. 15 The study examined 22 patients with chronic diseases with the primary aim of providing a preliminary understanding of their needs in a real context. The study has demonstrated that tailor-made solutions, which are personalized to the needs of the individual, are necessary.

In the area of colorectal carcinoma, different approaches to decision support have been implemented. Militello et al have evaluated a modular decision-support application for colorectal cancer screening with the goal of evaluating, through a decision-centered design framework, the ability of the screening and surveillance application to support primary-care clinicians in tracking and managing colorectal cancer testing. 16 The results have indicated that the screening and surveillance application promises to close decision support gaps in current EHRs. Suner et al have developed a web-based decision support tool for rectal cancer treatment, which uses an analytic hierarchy process and a decision tree. 17 The methodology has been applied to 388 patients and is expected to provide potential users with decision support in rectal cancer treatment processes and facilitate them in making projections about treatment options. There is no comparable work in the field of colorectal cancer that uses Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN) with Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) annotation as the modeling language for German-language treatment pathways and algorithms (based on German guidelines).

Objectives

This approach is modeled as rule-based BPMN treatment paths, which are created based on clinical guidelines and executed on a newly developed open-source workflow software system 18 to map medical knowledge with patient-specific data. This results in the following two primary challenges for the derivation of personalized guideline-based treatment proposals: (1) guidelines exist in a heterogeneous, nonformalized, and nonmachine-readable form of representation; and (2) there is no link between generic guideline knowledge and patient-specific information from information systems based on common terminology. The main goals of this approach are the modeling of machine-readable clinical algorithms for colon carcinoma and rectal carcinoma annotated by UMLS based on clinical guidelines and the development of an open-source workflow system for mapping the clinical algorithms with the patient-specific information to identify and visualize the position of the individual patient on the treatment algorithm for guideline-based therapy recommendations.

The aim of this approach is to create clinical paths or clinical algorithms based on an established business process standard, BPMN, which can be annotated by UMLS concepts. This approach is tested on colon and rectal cancer and could become a generic approach for all oncological diseases. The annotation of clinical algorithms and patient-specific data using a uniform terminology allows the establishment of a link between generic knowledge and patient-specific information. This enables the workflow system to run the algorithm individually for each patient and to identify and visualize the patient's position on the path. Since the BPMN standard does not offer UMLS support, this standard is extended by using UMLS concepts so that the workflow system can interpret these.

Methods

Study Setting

This study was conducted at the West German Cancer Center, University Hospital in Essen, Germany, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Essen. The analyzed cohort included 175 colorectal cancer patients. Table 1 displays each evaluated patient's dataset according to the German colorectal cancer guidelines based on the TNM (primary tumor, lymph node status, metastases) criteria. 19 The classification of the Union internationale contre le cancer (UICC) summarizes these criteria in stages ( Table 2 and Table 3 ). The algorithm reaches the decisions based on the TNM classification and assigns them to the UICC stages. In gastrointestinal tumors, T describes the depth of tumor infiltration into the bowel wall, N reflects the number of locoregional lymph nodes involved, and M describes the presence or absence of distant metastasis.

Table 1. Evaluation dataset.

| Tumor stages | IV | III | II | I | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colon cancer (1,003 clinical notes) | 58 | 17 | 11 | 0 | 86 |

| Rectal cancer (1,127 clinical notes) | 65 | 8 | 12 | 4 | 89 |

| Total (2,130 clinical notes) | 123 | 25 | 23 | 4 | 175 |

Table 2. UICC stages of rectal cancer.

| UICC stage | Primary tumor | Lymph node status | Metastases |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

| I | T1, T2 | N0 | M0 |

| IIA | T3 | N0 | M0 |

| T3a | N1 | M0 | |

| T3b | N2 | M0 | |

| T3c | N3 | M0 | |

| T3d | N4 | M0 | |

| IIB | T4 | N0 | M0 |

| IIIA | T1–2 | N1 | M0 |

| IIIB | T3–4 | N1 | M0 |

| IIIC | any T | N2 | M0 |

| IV | any T | any N | M1 |

Abbreviation: UICC, union internationale contre le cancer.

Table 3. UICC stages of colon cancer.

| UICC stage | Primary tumor | Lymph node status | Metastases |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

| I | T1, T2 | N0 | M0 |

| IIA | T3 | N0 | M0 |

| IIB | T4a | N0 | M0 |

| IIC | T4b | N0 | M0 |

| IIIA | T1–2 | N1 | M0 |

| T1 | N2a | M0 | |

| IIIB | T3–4 | N1 | M0 |

| T2–3 | N2a | M0 | |

| T1–2 | N2b | M0 | |

| IIIC | T4a | N2a | M0 |

| T3–T4a | N2b | M0 | |

| T4b | N1–2 | M0 | |

| IV | any T | any N | M1 |

Abbreviation: UICC, union internationale contre le cancer.

A total of 2,130 German clinical notes, including 698 medical reports, 680 radiology reports, 380 tumor board protocols, 94 microbiology reports, 260 pathology reports, and 18 virology reports were evaluated by a physician and a medical computer scientist. For the validation of the algorithm, a retrospective manual analysis of 175 colorectal cancer patients was performed. The sample was chosen to define the actual distribution of tumor stages and was selected by International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) codes from the EHR. No other restrictions were imposed, and the sample was random.

Standards

The UMLS, introduced by the U.S. National Library of Medicine, is a project that aims to harmonize the terminology of biomedical resources, such as online databases and medical dictionaries. 20 The harmonization is done by correlating the concepts and relations of various existing databases by creating ontologies. The UMLS Concept Unique Identifier (CUI) is used for a metathesaurus concept in which strings with the same meaning are linked.

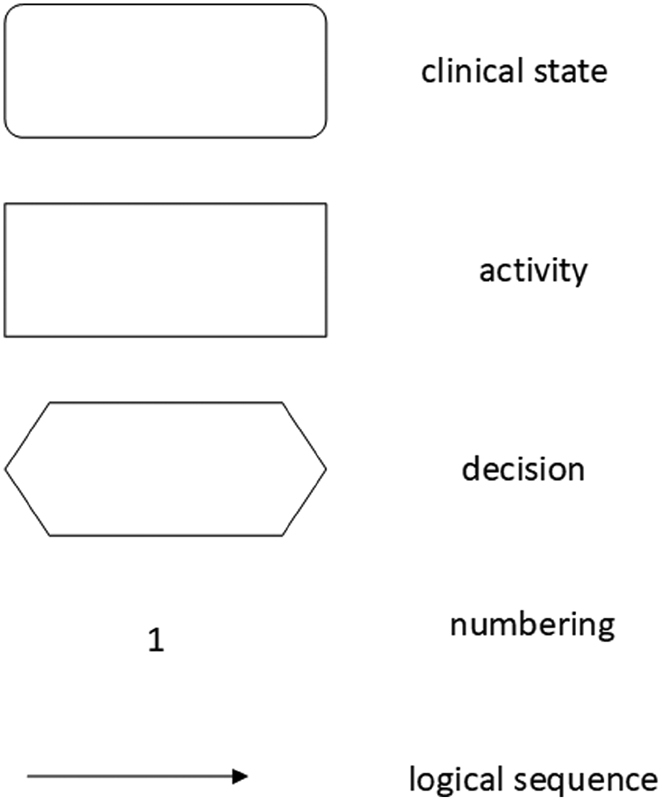

The visualization of the clinical algorithm is based on the BPMN, which is a graphical specification language in computer science and process management. 21 The BPMN was developed by the object management group, which provides a uniform graphical notation for the specification of business processes. In the literature, there are several approaches that use the BPMN from the medical area. Most studies use the BPMN to model clinical pathways, Scheuerlein et al, Andrzejewski et al, and Beck et al, have agreed that the BPMN is easy to use and quickly understood by all involved. 22 23 24 There is also work describing the experience of the collaborative modeling of clinical pathways by physicians with computer scientists. They report that BPMN training is relatively quick and intuitive 22 and that health professionals' deeper understanding of clinical processes facilitates changes and updates of the model. 25 In addition to the easy to understand process modeling and graphical representation, the elements that can be used in the BPMN are similar to those of the standard elements of the clinical algorithm specified in the guidelines ( Fig. 1 ), thus simplifying the transition from an algorithm to the BPMN. 26

Fig. 1.

Standard elements of the clinical algorithm according to the Medical Center for Quality in Medicine, Germany.

Study Design

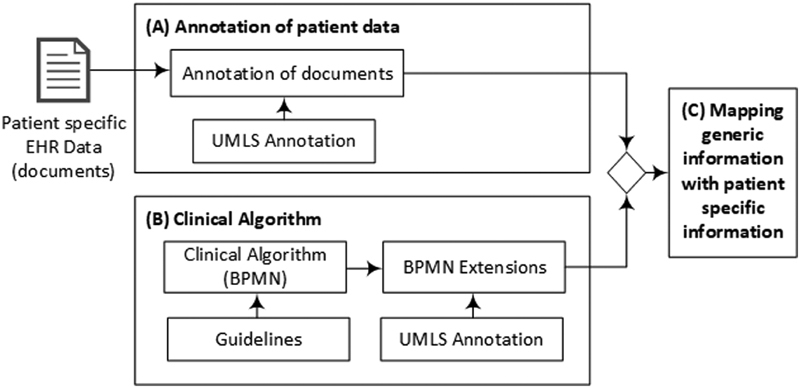

Fig. 2 illustrates the study design of the personalized guideline-based clinical decision support system which is divided into three processing steps. Based on the guidelines, (1) the first step is to model the clinical algorithms for the clinical pictures of colon carcinoma and rectal carcinoma and annotate them with UMLS concepts; (2) the patient-specific data from the EHRs are annotated using UMLS concepts, which are based on the gold standard; (3) in the third and last step, the clinical algorithm can be run by using the common terminology, and thus the position on this path can be determined individually for each patient. In the evaluation, the gold standard (the manually determined guideline-based treatment recommendations of the physicians) is compared with the determined treatment recommendations of the workflow system. An open-source workflow system was developed for the processing and visualization of the processes, as well as the simple graphical representation, of the position of an individual patient within the algorithm.

Fig. 2.

Study design: ( A ) patient data from the EHRs are manually annotated using UMLS concepts. ( B ) Based on the guidelines, a clinical algorithm is modeled with the BPMN and annotated with the same UMLS concepts as the patient data. ( C ) By using the same terminology, the patient data and the algorithm can be mapped to determine the patient's position in the algorithm. BPMN, business process model and notation; EHR, electronic health record; UMLS, unified medical language system.

Clinical Algorithm

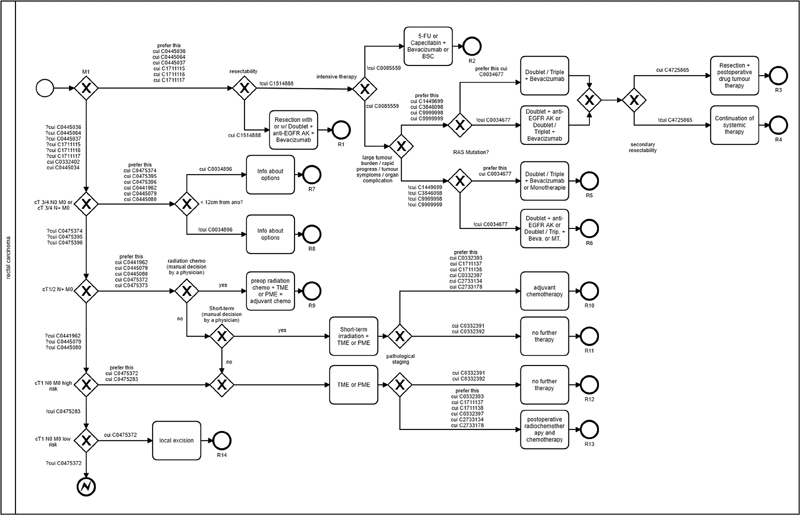

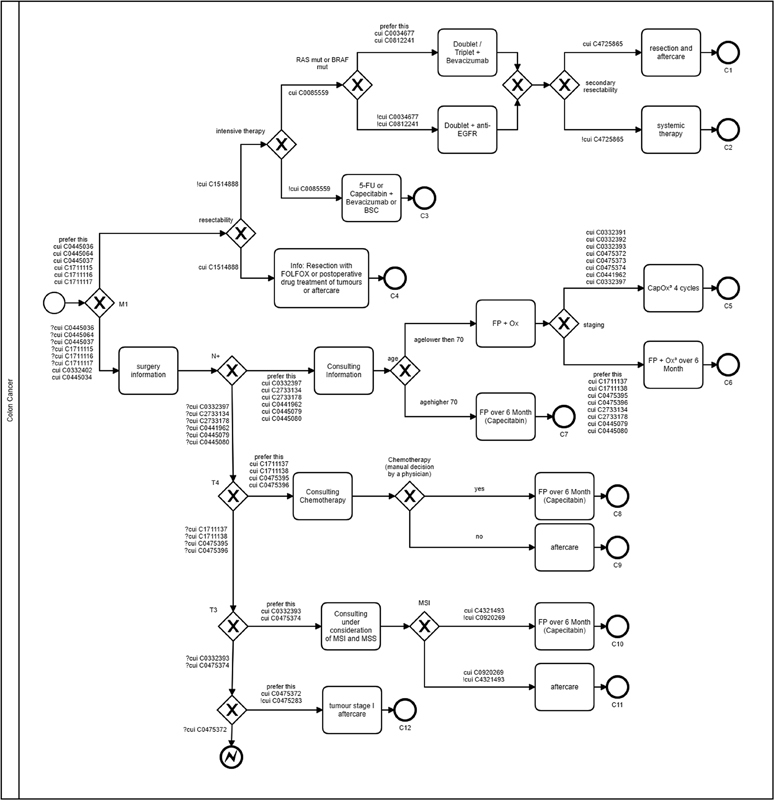

Guidelines and clinical algorithms are instruments for quality assurance and process optimization in the medical domain. 19 These guidelines describe a standardized procedure for the prevention, diagnosis, therapy, and aftercare of a specific disease at different levels of action. The transfer of evidence-based knowledge to a structured treatment process is not trivial due to the different informational content and semantic constructs. In contrast to clinical texts, no universal gold standard for the guidelines or clinical pathways exists, as the derived pathway can vary widely depending on the interpretation of the guideline content. Through this approach, two BPMN-based algorithms were developed, which represent the guideline-based therapy decision ( Figs. 3 and 4 ). To determine the patient's position on the path, the clinical algorithms were annotated by the same UMLS CUIs as the patient-specific information. Since the BPMN does not support UMLS-annotated pathways, the notation must be extended by various elements 27 ; Table 4 lists the extensions that were implemented. The decisions in the clinical path can be extended by using the UMLS concepts. A distinction was made as to whether a concept was identified with the respective patient (CUI), whether it was identified and denied (!CUI), whether the concept was not identified (?CUI), or whether both decision paths were correct and should be preferred (prefer_this). In particular, tumor stages can change during the diagnostic course, for example, through a pathological examination. In such a case, it must be defined in the BPMN path that the path with the higher stage is preferred. To visualize the content from the guidelines, the hint extension can be used to display text from the guidelines.

Fig. 3.

BPMN-based algorithm: rectal cancer. BPMN, business process model and notation.

Fig. 4.

BPMN-based algorithm: colon cancer. BPMN, business process model and notation.

Table 4. UMLS extensions in BPMN.

| Extension | Description |

|---|---|

| CUI | Concept identified |

| !CUI | Concept identified and negated |

| ?CUI | Concept not identified |

| prefer_this | Prefers this path if the CUIs are identified in both decision paths |

| Hint | Information on the level of recommendation |

Abbreviations: BPMN, business process model and notation; EHR, electronic health record; UMLS, unified medical language system.

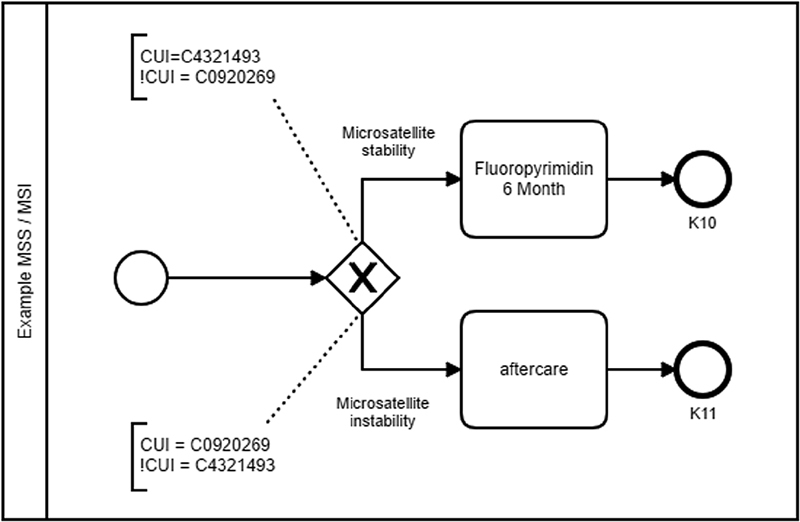

The syntax is described using the example of the decision of the microsatellite status. Fig. 5 illustrates how the decision can be converted into the BPMN using the CUI with the help of the BPMN extensions. As an example, therapy recommendation K10 is chosen if a patient has been identified as having CUI C4321493 (microsatellite stability) or if CUI C0920269 has been negated (no microsatellite instability). Therapy recommendation K11 is selected if CUI C0920269 (microsatellite instability) has been identified in a patient, or if CUI C4321493 has been negated (no microsatellite stability). If both CUIs C4321493 and C0920269 are not identified as negated or jointly negated, no decision can be made by the algorithm.

Fig. 5.

Implementation example MSI/MSS. MSI, microsatellite instability; MSS, microsatellite stability; CUI, concept unique identifier.

Annotation of Patient Data

The gold standard was defined by a clinical oncologist regarding the information needed to derive a guideline-compliant recommendation. Based on the clinical algorithm, the UMLS concepts were extrapolated to determine the position on the path. Accordingly, an annotation dataset ( Appendix A —annotation_dataset.pdf) was developed for a computer scientist and the oncologist to manually annotate the patient data comprising 2,130 clinical notes. To evaluate only the clinical algorithm and not the quality of the available patient data, these data were preprocessed and structured. To use this solution in regular clinical operations, unstructured data would have to be automatically preprocessed, such as by text mining.

Appendix A. Annotation dataset.

| Item | Term | CUI |

|---|---|---|

| T0 | T0 | C0475371 |

| T1 | T1 | C0475372 |

| T2 | T2 | C0475373 |

| T3 | T3 | C0475374 |

| T4a | T4a | C0475395 |

| T4b | T4b | C0475396 |

| pT0 | pT0 | C0332390 |

| pT1 | pT1 | C0332391 |

| pT2 | pT2 | C0332392 |

| pT3 | pT3 | C0332393 |

| pT4a | pT4a | C1711137 |

| pT4b | pT4b | C1711138 |

| N0 | N0 | C0441959 |

| N1 | N1 | C0441962 |

| N2a | N2a | C0445079 |

| N2b | N2b | C0445080 |

| pN0 | pN0 | C0332396 |

| pN1 | pN1 | C0332397 |

| pN2a | pN2a | C2733134 |

| pN2b | pN2b | C2733178 |

| M0 | M0 | C0445034 |

| M1a | M1a | C0445036 |

| M1b | M1b | C0445064 |

| M1c | M1c | C0445037 |

| pM0 | pM0 | C0332402 |

| pM1a | pM1a | C1711115 |

| pM1b | pM1b | C1711116 |

| pM1c | pM1c | C1711117 |

| MSI | Microsatellite instability | C0920269 |

| MSS | Microsatellite stable | C4321493 |

| RAS | retrovirus-associated DNA sequences (RAS) | C0034677 |

| BRAF | BRAF gene | C0812241 |

| RES | Resectable | C1514888 |

| ANO | Rectum (<12 cm from ANO) | C0034896 |

| IT | Intensive care | C0085559 |

| TL | Tumor burden | C1449699 |

| RP | Rapid progress | C9999999 |

| TS | Tumor/symptoms | C3846098 |

| OK | Organ compilation | C9999998 |

| HR | High risk | C0475283 |

| SRES | secondary resectable | C4725865 |

Gold Standard Evaluation

To evaluate the therapy recommendations, the endpoints of the algorithm were numbered consecutively and determined manually by an oncologist for each patient ( Table 5 ). The algorithms resulted in 14 possible therapy decisions for rectal cancer and 12 possible therapy decisions for colon cancer ( Figs. 3 and 4 ). In the analysis of the data for colon cancer, there were four cases in which no final therapy decision could be made based on the available data. In these cases, the final pathological findings on the microsatellite instability (MSI) status were not yet available. In the analyzed patient collective, cases in which the MSI was absent occurred exclusively in patients with colon carcinoma. Therefore, the algorithm had to stop the decision process in these cases. Depending on the MSI status, the result was an endpoint of either C10 (microsatellite stable) or C11 (microsatellite instable). In addition, these endpoints were assigned to different TNM stages.

Table 5. Gold standard evaluation dataset for colon and rectal cancer.

| Rectal cancer endpoint | Tumor stage | No. | Colon cancer endpoint | Tumor stage | No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | IV | 19 | C1 | IV | 2 |

| R2 | IV | 9 | C2 | IV | 26 |

| R3 | IV | 2 | C3 | IV | 10 |

| R4 | IV | 4 | C4 | IV | 27 |

| R5 | IV | 17 | C5 | III | 4 |

| R6 | IV | 7 | C6 | III | 2 |

| R7 | III | 8 | C7 | III | 2 |

| R8 | III | 5 | C8 | II | 1 |

| R9 | III | 0 | C9 | II | 1 |

| R10 | III | 4 | C10 | II | 3 |

| R11 | III | 0 | C11 | II | 3 |

| R12 | II | 5 | C12 | I | 4 |

| R13 | II | 6 | MSI | II | 4 |

| R14 | I | 0 | |||

| Total | 86 | Total | 89 |

Abbreviations: C1–12, endpoint for colon cancer (treatment recommendation); MSI, microsatellite instability decision point; R1–14, endpoint for rectal cancer (treatment recommendation).

Statistical Analysis

For this approach, the treatment recommendations were compared with the gold standard of the respective endpoints and the associated TNM stages. The following values were determined: the precision or positive predictive value ( P ), recall or true positive rate ( R ), and F1 measure ( F1 ), for which recall and precision were equally weighted. The F1 score is the harmonic mean of the precision and recall, where an F1 score reaches its best value at 1 and worst at 0.

A Chi-squared test was applied to evaluate the statistical independence of the differences in the distribution between colon and rectal cancer. The statistical significance was determined to be p < 0.05, and a 95% confidence interval was calculated.

Results

The colorectal cancer cohort dataset included 175 patients. There were 89 colon cancer cases and 86 rectal cancer cases. The dataset contained 2,130 clinical notes. The mean age of the patients in the dataset was 62.9 years, and 45% of the patients were female. Tables 6 and 7 detail the treatment recommendation performance of the clinical algorithm compared with the gold standard. Using this approach for therapy recommendation, the algorithm achieved a precision value of 87.64% for colon cancer and 84.70% for rectal cancer with recall values of 87.64 and 83.72%. For the clinical algorithm of colon carcinoma, a total of 89 patients with confirmed diagnoses were retrospectively analyzed. Table 7 displays the correct (true positive) and incorrect (false positive and false negative) treatment recommendations for the respective TNM stages and treatment decisions of colon cancer (K1–K12 and MSI). The patients with stages I and II were completely and correctly identified (100% recall and 100% precision). Patients with stages III and IV were more weakly identified compared with the other stages in terms of treatment recommendations. This can be attributed to the significantly higher complexity (more decision points) of the stage III and IV algorithms. For the clinical algorithm of rectal cancer, a total of 87 patients with confirmed diagnoses were retrospectively analyzed. Table 6 displays the respective TNM stages and treatment decisions (R1–R14). In contrast to colon carcinoma, the rectal carcinoma algorithm identified the weakest results in cases with stage IV (79% recall) and stage III (73% precision) and the best results for stage II. The incorrectly determined treatment recommendations in stage III are conspicuous. This can be traced back to the path design of rectal carcinoma because, in contrast to colon carcinoma in stages II and III, pathohistological staging is performed, which cannot be clearly assigned without a chronological component, which has not been taken into account in this work.

Table 6. Evaluation of rectal cancer treatment recommendations.

| Endpoints | GS | TP | FP | FN | R | P | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage IV | 58 | 46 | 6 | 12 | 0.79 | 0.88 | 0.84 |

| R1 | 19 | 16 | 2 | 3 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.86 |

| R2 | 9 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 0.78 | 0.88 | 0.82 |

| R3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.67 |

| R4 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 0.86 |

| R5 | 17 | 13 | 1 | 4 | 0.76 | 0.93 | 0.84 |

| R6 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 0.71 | 1.00 | 0.83 |

| Stage III | 17 | 16 | 6 | 1 | 0.94 | 0.73 | 0.82 |

| R7 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 |

| R8 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.71 | 0.83 |

| R9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | – | – |

| R10 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.57 | 0.73 |

| R11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | – | – |

| Stage II | 11 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.87 |

| R12 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.89 |

| R13 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.86 |

| Stage I | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | – | – |

| R14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | – | – |

| Total | 86 | 72 | 14 | 14 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.84 |

Abbreviations: F1, F measure; FN, false negatives; FP, false positives; GS, gold standard; P, precision or positive predictive value; R, recall or true positive rate; TP , true positives.

Table 7. Evaluation of colon cancer treatment recommendations.

| Endpoints | GS | TP | FP | FN | R | P | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage IV | 65 | 55 | 10 | 10 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| C1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| C2 | 26 | 19 | 0 | 7 | 0.73 | 1.00 | 0.84 |

| C3 | 10 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 0.90 | 0.82 | 0.86 |

| C4 | 27 | 26 | 7 | 1 | 0.96 | 0.79 | 0.87 |

| Stage III | 8 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 |

| C5 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 0.86 |

| C6 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| C7 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.80 |

| Stage II | 12 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| C8 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| C9 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| C10 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| C11 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| MSI | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Stage I | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| C12 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Total | 89 | 78 | 11 | 11 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 |

Abbreviations: F1, F measure Equations; FN, false negatives; FP, false positives; GS, gold standard; P, precision or positive predictive value; R, recall or true positive rate; TP, true positives.

The Chi-squared test under the null hypothesis that there is no association between colon and rectal cancer ( p < 0.05) indicates a strong correlation between the results for colon and rectal cancer even though the results differ in certain tumor stadiums. The null hypothesis that there is no association can be rejected, meaning that the results of the two clinical pictures indicate a strong similarity.

Discussion

This study qualitatively assessed the therapy decision of clinical algorithms as part of a clinical pathway. The results indicate that automatically positioning a patient on the decision path is possible. It can be deduced that nonextensive tumor stages with fewer decision points achieve higher accuracy compared with complex stages. Since the dataset analyzed was provided by a university hospital, most of the cases feature highly complex patients who are frequently treated within clinical trials. Based on this, the failure of the developed algorithms to deliver the correct results can be attributed to various reasons, for example, patients treated within clinical trials often deviate from the guideline-based path due to new treatment methods. In addition, patients sometimes decline different therapies that are recommended by the developed clinical algorithm. Furthermore, some clinical decisions are made by the interpretation of radiological examinations, such as the resectability of metastasis. For this purpose, image data that have not been considered in the context of this work must be analyzed, such as by image mining. The aforementioned misinterpretations by the clinical algorithms cannot be recognized by the approach presented here, since a therapy recommendation can only be issued after the definition of a guideline.

The analysis of the results demonstrates that the current possibilities of path design are not yet sufficient. For cases that initially have a low TNM stage and are reclassified to a higher TNM stage during the diagnostic procedures, an extension of the path design becomes necessary, and a chronological interpretation of the results must be presented during the hospital stay. If pathohistological staging was performed in the later course of treatment, this information had no chronological component. Since this information was available to the algorithm at the beginning of the derivation of the therapy recommendation, the algorithm identified the higher stage because the pathohistological staging had a higher stage than the clinical staging. In some cases, for example, in rectal cancer, a different path was chosen for patients other than the gold standard but with the same therapy recommendation at the end (adjuvant chemotherapy). The incorrectly identified cases in the colon carcinoma algorithm can also be traced back to the missing chronological component of the information. Here, it was decided whether an intensive therapy was possible in the cases that had not been correctly determined, which had changed over the course of the treatment. For cases that initially have a low-TNM stage and are classified into a higher TNM stage during diagnosis or treatment, the algorithms must be extended and a chronological interpretation of the results determined during the hospital stay. Cases in which stage IV was not identified correctly are particularly critical. Since the therapeutic approach and the 5-year survival rate for stage-IV colorectal cancer differ considerably from those in the lower stages, any incorrect therapy recommendation would have significant consequences. In four cases, a stage-III tumor was determined, and in one case, a stage-I tumor was identified, even though these cases were stage IV. If the algorithm detected stage-IV disease, it was correct in all cases, even if the correct therapy decision was not always determined. In addition, complex cases with secondary tumors could not be allocated to guideline-based treatment. Further decisions and a more complex path design are needed to map these cases to achieve better outcomes.

Conclusion

Clinical practice, as well as research and quality assurance, benefits from clear clinical information using common terminology such as UMLS. This common terminology is necessary for the consistent reuse of data and the support of semantic interoperability. To derive treatment recommendations from guidelines based on patient-specific data, knowledge from the guidelines is combined with patient-specific information. A further approach would be to display treatment-relevant information in archetype-based templates in addition to decision support from the guidelines. Using the examples of colon and rectal cancer, we demonstrated that the model developed in this study can structure the given information from a guideline and could easily be included for use as a clinical decision-support tool in treatment pathways. To make the path available at the point of care, it is necessary to link it to the patient data and to integrate it into a hospital information system. 28 29

Clinical Relevance Statement

Evidence-based guidelines can have a positive impact on the quality of medical care, but their influence on patient care in Germany is still very small. With the help of workflow software, the physician could be shown guideline-based treatment recommendations tailored to the patient so that interested physicians do not have to actively search and study the contents of the guidelines. This approach enables a fast, simple, and clear provision of evidence-based knowledge at the point of care.

Multiple Choice Questions

-

What information can be found in clinical guidelines?

Guidance for the economic operation of a hospital.

Patient information for care measures.

The current recommended diagnostic and therapeutic procedures for a specific disease.

International billing types in medicine.

Correct Answer: The correct answer is option c. Clinical guidelines include the current recommended diagnostic and therapeutic procedures for a specific disease.

-

What was the Business Process Model and Notation standard developed for?

Graphical representation for specifying business processes.

Mapping of terminologies in medicine.

As a development environment for medical information systems.

As a communication standard between a laboratory information system and a hospital information system.

Correct Answer: The correct answer is option a. BPMN is a graphical representation for specifying business processes.

Funding Statement

Funding The research reported in this publication was supported by the West German Cancer Center and the Institute of Medical Informatics, Biometry and Epidemiology in Essen, Germany. This study was performed free of charge and for noncommercial purposes. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the University Hospital in Essen, Germany.

Conflict of Interest None declared.

Protection of Human and Animal Subjects

The study was performed in compliance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects and was reviewed by the University Hospital Ethics Committee, Essen Germany.

References

- 1.Robert-Koch-Institut.Gesellschaft der epidemiologischen Krebsregister in Deutschland. Krebs in Deutschland, 8th ed Berlin, Germany: 201236–39. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robert-Koch-Institut. Bericht zum Krebsgeschehen in Deutschland 2016. Available at:https://edoc.rki.de/bitstream/handle/176904/3264/28oaKVmif0wDk.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed February 11, 2020

- 3.Majek O, Gondos A, Jansen L et al. Survival from colorectal cancer in Germany in the early 21st century. Br J Cancer. 2012;106(11):1875–1880. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leitlinie-Detailansicht Kolorektales Karzinom. Available at:http://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/021-007OL.html. Accessed October 2, 2019

- 5.Haeske-Seeberg H. Stuttgart, Germany: Kohlhammer Verlag; 2008. Handbuch Qualitätsmanagement im Krankenhaus: Strategien, Analysen, Konzepte; p. 248. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grimshaw J M, Thomas R E, MacLennan Get al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies Health Technol Assess 2004806iii–iv., 1–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oberender P O. Stuttgart, Germany: Kohlhammer Verlag; 2005. Clinical Pathways: Facetten eines neuen Versorgungsmodells. Krankenhaus; p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lelgemann M, Ollenschläger G.[Evidence based guidelines and clinical pathways: complementation or contradiction?] (German) Internist (Berl) 20064707690–692., 697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lenz R, Kuhn K. Informatik Verbindet Ulm; 2004. Aspekte einer prozessorientierten Systemarchitektur für Informationssysteme im Gesundheitswesen. P. Dadam und M. Reichert - Informatik 2004; pp. 530–536. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shea S, DuMouchel W, Bahamonde L. A meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled trials to evaluate computer-based clinical reminder systems for preventive care in the ambulatory setting. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1996;3(06):399–409. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1996.97084513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawamoto K, Houlihan C A, Balas E A, Lobach D F.Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success BMJ 2005330(7494):765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steffen H M, Griebenow R, Meuthen I, Schrappe M, Ziegenhagen D J. Schattauer; Stuttgart, Germany: 2008. Internistische Differenzialdiagnostik: Ausgewählte evidenzbasierte Entscheidungsprozesse und diagnostische Pfade; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobs B.Ableitung von klinischen Pfaden aus evidenzbasierten Leitlinien am Beispiel der Behandlung des Mammakarzinoms der FrauDissertation (PhD thesis). Medizinische Fakultät der Universität Duisburg-Essen. Germany;2006

- 14.Bernstein K, Andersen U. Managing care pathways combining SNOMED CT, archetypes and an electronic guideline system. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2008;136:353–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lasorsa I, Antrassi DP, Ajčević M et al. Personalized support for chronic conditions. A novel approach for enhancing self-management and improving lifestyle. Appl Clin Inform. 2016;7(03):633–645. doi: 10.4338/ACI-2016-01-RA-0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Militello L G, Diiulio J B, Borders M R et al. Evaluating a modular decision support application for colorectal cancer screening. Appl Clin Inform. 2017;8(01):162–179. doi: 10.4338/ACI-2016-09-RA-0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suner A, Karakülah G, Dicle O, Sökmen S, Çelikoğlu C C. CorRECTreatment: a web-based decision support tool for rectal cancer treatment that uses the analytic hierarchy process and decision tree. Appl Clin Inform. 2015;6(01):56–74. doi: 10.4338/ACI-2014-10-RA-0087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becker M. Guide2Treat: Software. Available at:https://ieee-dataport.org/documents/guide2treat-software. Accessed February 11, 2019

- 19.Wittekind C, Meyer H J. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co.; 2010. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, Wiley-VCH; pp. 94–100. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McInnes B T, Pedersen T, Carlis J. Using UMLS concept unique identifiers (CUIs) for word sense disambiguation in the biomedical domain. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2007;2007:533–537. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramos-Merino M, Álvarez-Sabucedo L M, Santos-Gago J M, Sanz-Valero J. A BPMN Based Notation for the Representation of Workflows in Hospital Protocols. J Med Syst. 2018;42(10):181. doi: 10.1007/s10916-018-1034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scheuerlein H, Rauchfuss F, Dittmar Y et al. New methods for clinical pathways-Business Process Modeling Notation (BPMN) and Tangible Business Process Modeling (t.BPM) Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2012;397(05):755–761. doi: 10.1007/s00423-012-0914-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrzejewski D, Ledwon P, Beck E. Möglichkeiten und Grenzen der BPMN als Werkzeug zur Modellierung medizinischer Prozesse und evidenzbasierter Behandlungspfade. Senologie Zeitschrift Mammadiagnostik Therap. 2012;9:A5. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beck E, Streit B, Meissner Tet al. Modellierung medizinischer Prozesse mit der Business Process Modeling Notation (BPMN) Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 2011•••71–P515.. Doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1278635 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirchner K, Malessa C, Scheuerlein H, Settmacher U. Experience from collaborative modeling of clinical pathways. Available at:https://www.researchgate.net/publication/306426138. Accessed February 11, 2020

- 26.AWMF. Das Leitlinien-Manual. Zeitschrift für ärztliche Fortbildung und Qualitätssicherung. Unter Mitarbeit von Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) und die Ärztliche Zentralstelle für Qualitätssicherung. Urban&Fischer. Available at:https://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/awmf-regelwerk/awmf-publikationen-zu-leitlinien/leitlinien-manual.html. Accessed February 11, 2020

- 27.Braun R, Schlieter H.Requirements-based development of BPMN extensions: The case of clinical pathways2014 IEEE 1st International Workshop on the Interrelations between Requirements Engineering and Business Process Management (REBPM). IEEE201439–44. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heiden K, Böckmann B. Structured knowledge acquisition for defining guideline-compliant pathways. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013;186:73–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heiden K.Modellbasierte Integration evidenzbasierter Leitlinien in klinische PfadeU. Goltz, M.A. Magnor, J. Appelrath, H, H. Matthies, W.-T. Balke, L.C. Wolf (Hrsg.). Informatik 2012, 42. Jahrestagung der Gesellschaft für Informatik e.V. (GI). 16.-21.09.2012, Braunschweig, Germany;20121864–1870. [Google Scholar]