Abstract

Protected areas (PAs) are a foundational and essential strategy for reducing biodiversity loss. However, many PAs around the world exist on paper only; thus, while logging and habitat conversion may be banned in these areas, illegal activities often continue to cause alarming habitat destruction. In such cases, the presence of armed conflict may ultimately prevent incursions to a greater extent than the absence of conflict. Although there are several reports of habitat destruction following cessation of conflict, there has never been a systematic and quantitative “before-and-after-conflict” analysis of a large sample of PAs and surrounding areas. Here we report the results of such a study in Colombia, using an open-access global forest change dataset. By analysing 39 PAs over three years before and after Colombia’s peace agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), we found a dramatic and highly significant increase in the deforestation rate for the majority of these areas and their buffer zones. We discuss the reasons behind such findings from the Colombian case, and debate some general conservation lessons applicable to other countries undergoing post-conflict transitions.

Subject terms: Conservation biology, Forestry

Introduction

The growing warfare ecology literature reports both negative and positive effects of conflict for biodiversity and the natural environment1–3. This also applies to deforestation, which can be either increased or decreased depending on the specific complex socio-ecological dynamics linked to the conflict itself3–5. Increased deforestation during conflict is reported for several regions of the world6, including Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Liberia7 or Myanmar and Cambodia8. In some cases, conflict reduces the institutional capacity to enforce laws and effectively manage the use or protection of natural resources, e.g. as reported for Kenya9, DRC10, Nepal11, and Colombia5. In other cases, the displacement of people escaping or forced to leave conflict areas, the basic mechanism for the ‘refuge effect’12, can prove beneficial for habitat and biodiversity protection, e.g. by limiting the pressure of resource extraction13–15. The demilitarized Zone between North and South Korea is a good example of such a refuge16. Conflict can largely disrupt economic activities1, such as timber logging in Nicaragua17, or farming, as in Sierra Leone18. In the Chechen wars and in the nearby Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, agricultural land was abandoned in warzones, along with reported low re-cultivation rates after the cessation of the conflict19,20. In other cases post-conflict development results in higher threats to forested ecosystems than conflict itself, such as in Rwanda and Liberia, where it led to increased land grabbing and logging21,22. In Peru, five years after armed conflict with the Shining Path ended, average forest loss increased by 58% due to government agriculture incentives and private investments23. Therefore, the end of a conflict is a particularly important moment for conservation24.

Narcotics can also be key factors linked to deforestation dynamics, especially in Central and South America25–27. Deforestation hotspots and protected areas often overlap with regions of drug production and trafficking28. For example, McSweeney et al.29 discussed how in Central America, a drug trafficking corridor, forests are often cleared to open roads and airstrips for drug transportation, to facilitate cultivation -often in conservation and indigenous areas through land grabbing and falsifying land titles-, and to expand other narco-capitalized businesses. Studies have found that illicit crops is a direct driver of deforestation30–32, and that policies of forced eradication can result in exacerbating the phenomenon33,34. In this sense, the conservation and proper governance of territories affected by narcotics cultivation is strongly linked to the efficiency of drug policies, which intensely focus on the supply-side reduction29,35. In addition, poverty and the lack of economic options in rural and remote areas with weak governability is also a key factor indirectly driving deforestation through illicit crops cultivation and land grabbing linked to agricultural activities34,36. Communities living in regions structurally characterized by lack of infrastructural development and established stable markets, often rely on forest clearing to claim land for subsistence agriculture or more profitable illicit activities. In Colombia, for example, rural settlers and small farmers, were found to be selling deforested land, in some cases opportunistically, in others under duress, to larger, well-organized agricultural producers, who in turn expect the government to adopt land tenure policies favorable to their interests37.

Indeed, several overlapping and interacting drivers have shaped the history of the transformation of the Colombian natural environment. Since the XVIII century about a third of the country’s forest cover shifted to multiple productive land-uses, mostly by the introduction of the cattle culture and expansion of grazing lands, urbanization and colonization of the lowlands38. In recent years forest loss has been driven by multiple shifting interacting forces, influenced by intraregional variations39. Major drivers of deforestation are the expansion of the agricultural frontier40 and the transformation of forest into pastures for cattle ranching41. Other local causes of deforestation include the creation of roads39,42 and human settlements41,43. In the last decades, illicit activities have been also part of the driving forces behind deforestation, mainly through their relation with illegal crops44, mining45 and logging46. In some regions, the limited access to certain areas because of the presence of different armed groups, resulted in the creation of a strong barrier that caused biodiversity protection47. In particular, protected areas have been major actors affected by deforestation nationally. Some of these PAs occur in areas of armed conflict and areas of intense illegal activities37. They have been found to successfully reduce deforestation44, however, as it occurs in other tropical regions, protected areas are disproportionately located in areas of low vulnerability48, i.e. away from roads, in soils unsuitable for agriculture, etc.

Overall, the literature on protected areas shows diverse effects on protection of forests and nature, varying largely from one geographical region to another49. Some evidence reports global ineffectiveness of PAs in preserving natural habitat within their boundaries, and identified widespread inadequate resourcing, in staff and budgets50,51. Other studies demonstrate that globally, PAs reduce the conversion of natural land cover when compared to non-protected areas52, and generally contribute to the conservation of local biodiversity53. In the case of Colombia, some literature showed that PAs and indigenous reserves can reduce deforestation, although the magnitude of this effect varies substantially depending on other governance covariates54,55.

Colombia endured five decades of armed conflict with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) until a peace agreement was signed in 201656. Colombia’s circumstances – containing a large network of conservation areas and having experienced a lengthy armed conflict ending in peace – provided suitable conditions for testing the hypothesis that conflict can substitute for enforcement in protected areas (PAs) in terms of forest cover, such that peace prompts an immediate increase in illegal deforestation57. Our analyses below focused on deforestation in and around 39 continental PAs in Colombia, representing either terrestrial National Natural Parks (NNPs) or National Natural Reserves (NNRs). We used the high-resolution Global Forest Change dataset58 to estimate the extent of deforestation over three years before the peace agreement (2013, 2014, and 2015) and three years after conflict (2016, 2017 and 2018). The analysis considers both the administrative limits of PAs and a 10-km buffer zone around them. These zones are critical because they limit the pressure for habitat conversion within parks and mitigate the well-known effects of ecological isolation59,60. The PAs analyzed in this study as such have strict legal protection, equivalent to IUCN categories I to IV. The territory included in these typologies of protected areas has not been, at the time of its initial establishment, substantially altered by human exploitation or occupation, and represents ecosystems, geomorphological landscapes and cultural manifestations of outstanding ecological, scientific, and anthropological value.

Results

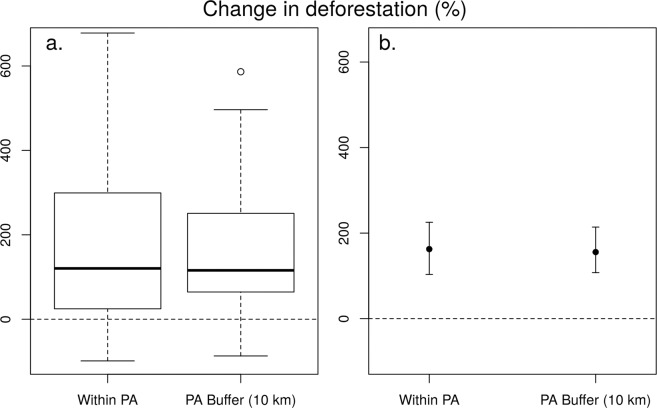

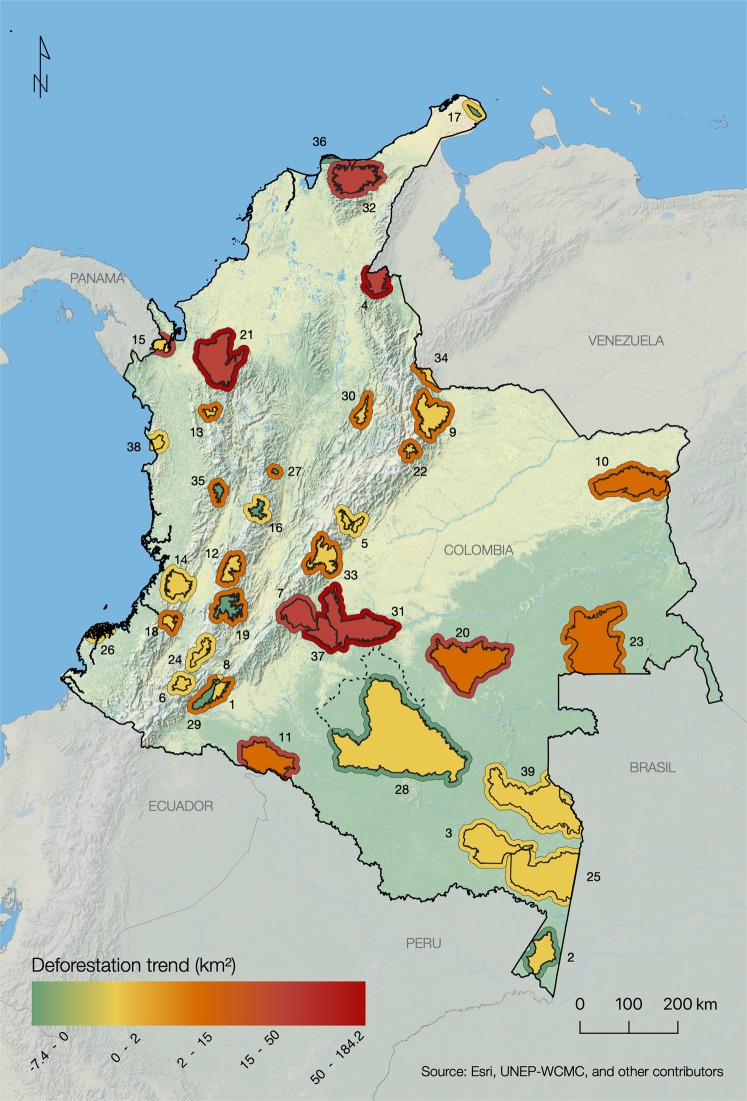

The results are striking (Table 1; Fig. 1). Overall, in the Colombian NNPs and NNRs, 31 of the 39 PAs (79%) experienced increased deforestation in the post-conflict years (Fig. 2). This translated into a dramatic and highly significant 177% increase in the deforestation rate between the two 3-year periods (Wilcoxon V = 44, p = 1.81e-06), resulting in 330 km2 of additional loss of protected forest. In the biogeographical Amazon, of which FARC controlled vast areas, several parks suffered notably severe upswings in deforestation following the peace agreement; a prime example is the case of Serranía de la Macarena NNP (Table 1). A similar pattern was observed in the parks’ buffer areas, showing an overall post-conflict increase of +158% in forest conversion (+686 km2; Wilcoxon V = 37, p = 4.34e-07). These territories are generally represented by remote rural landscapes, where land grabbing and illicit cropping often drive land cover change39. Such a massive increase in natural habitat loss, often of primary forests, has potentially profound effects on biodiversity61,62. Additionally, at a regional level, natural habitat conversion in and around parks rapidly accelerates disruption of large ecological corridors, which act as important connectivity bridges between the biogeographical Amazon and the Andes28.

Table 1.

Deforestation statistics for 39 protected areas (PAs) of Colombia (National Natural Park -NNP- or National Natural Reserve -NNR-) using Hansen et al. (2013) Global Forest Change dataset, ver. 1.6.

| Name | Typology | ID | Inside the PA | Buffer of the PA (10 km) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deforestation Before (km2) | Deforestation After (km2) | Deforestation Change (km2) | Percentage Change | Deforestation Before (km2) | Deforestation After (km2) | Deforestation Change (km2) | Percentage Change | |||

| (t0) | (t1) | (t1 − t0) | (t1 − t0)/t0*100 | (t0) | (t1) | (t1 − t0) | (t1 − t0)/t0 * 100 | |||

| Alto Fragua Indiwasi | NNP | 1 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 51.1% | 8.0 | 13.5 | 5.5 | 68.7% |

| Amacayacu | NNP | 2 | 0.8 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 117.9% | 4.5 | 4.2 | −0.3 | −7.0% |

| Cahuinari | NNP | 3 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 254.6% | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 73.0% |

| Catatumbo Bari | NNP | 4 | 11.6 | 55.9 | 44.3 | 382.9% | 42.4 | 131.7 | 89.3 | 210.6% |

| Chingaza | NNP | 5 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 678.0% | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 115.8% |

| Complejo Volcanico Doña J. Cascabel | NNP | 6 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 209.4% | 1.7 | 3.4 | 1.7 | 95.9% |

| Cordillera de los Picachos | NNP | 7 | 10.6 | 33.0 | 22.3 | 210.1% | 9.4 | 55.8 | 46.4 | 496.4% |

| Cueva de los Guacharos | NNP | 8 | <0.01 | 0 | <0.01 | <0.01% | 0.6 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 266.5% |

| El Cocuy | NNP | 9 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 545.8% | 1.6 | 6.6 | 5.1 | 323.9% |

| El Tuparro | NNP | 10 | 0.6 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 345.0% | 5.1 | 9.8 | 4.7 | 91.5% |

| La Paya | NNP | 11 | 23.6 | 34.5 | 10.9 | 46.2% | 72.2 | 121.0 | 48.8 | 67.7% |

| Las Hermosas | NNP | 12 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 117.2% | 2.1 | 6.7 | 4.7 | 227.2% |

| Las Orquideas | NNP | 13 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 451.9% | 1.9 | 8.8 | 7.0 | 375.8% |

| Los Farallones de Cali | NNP | 14 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 170.6% | 3.3 | 5.1 | 1.8 | 52.5% |

| Los Katios | NNP | 15 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 257.5% | 8.1 | 38.5 | 30.4 | 374.2% |

| Los Nevados | NNP | 16 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −46.6% | 3.8 | 4.8 | 1.0 | 27.2% |

| Macuira | NNP | 17 | 0.14 | 0.03 | −0.11 | −79.3% | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01% |

| Munchique | NNP | 18 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 90.1% | 9.6 | 23.9 | 14.2 | 147.6% |

| Nevado del Huila | NNP | 19 | 0.3 | 0.2 | −0.1 | −19.1% | 6.1 | 16.6 | 10.5 | 172.4% |

| Nukak | NNR | 20 | 9.3 | 19.2 | 9.9 | 105.8% | 9.3 | 42.0 | 32.7 | 352.9% |

| Paramillo | NNP | 21 | 19.5 | 48.0 | 28.5 | 146.4% | 26.0 | 78.5 | 52.6 | 202.5% |

| Pisba | NNP | 22 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 459.4% | 0.4 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 586.3% |

| Puinawai | NNR | 23 | 6.2 | 11.8 | 5.6 | 89.5% | 5.2 | 7.5 | 2.2 | 42.8% |

| Purace | NNP | 24 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 170.8% | 0.5 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 145.3% |

| Rio Pure | NNP | 25 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 307.1% | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 100.3% |

| Sanquianga | NNP | 26 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 25.7% | 3.8 | 4.6 | 0.8 | 21.3% |

| Selva de Florencia | NNP | 27 | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.01 | −17.7% | 2.6 | 9.8 | 7.2 | 279.0% |

| Serrania de Chiribiquete | NNP | 28 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 0.2 | 5.1% | 2.4 | 1.2 | −1.2 | −48.1% |

| Serrania de los Churumbelos | NNP | 29 | 0.4 | 0.4 | −0.1 | −16.0% | 12.2 | 22.2 | 10.0 | 81.9% |

| Serrania de los Yariguies | NNP | 30 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 191.0% | 2.8 | 15.9 | 13.1 | 468.6% |

| Sierra de la Macarena | NNP | 31 | 41.4 | 91.2 | 49.8 | 120.4% | 103.7 | 287.9 | 184.2 | 177.7% |

| Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta | NNP | 32 | 7.4 | 30.0 | 22.6 | 304.7% | 28.1 | 51.7 | 23.5 | 83.7% |

| Sumapaz | NNP | 33 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 68.3% | 1.3 | 3.8 | 2.5 | 198.5% |

| Tama | NNP | 34 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 293.8% | 3.5 | 7.4 | 3.9 | 108.8% |

| Tatama | NNP | 35 | 0.11 | 0.09 | −0.02 | −15.8% | 3.4 | 13.3 | 9.9 | 287.8% |

| Tayrona | NNP | 36 | 1.49 | 0.02 | −1.47 | −98.7% | 8.5 | 1.1 | −7.4 | −87.0% |

| Tinigua | NNP | 37 | 37.5 | 159.5 | 122.0 | 325.7% | 30.7 | 103.0 | 72.3 | 235.1% |

| Utria | NNP | 38 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 341.0% | 1.0 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 61.3% |

| Yaigoje Apaporis | NNP | 39 | 6.7 | 8.2 | 1.6 | 23.6% | 6.8 | 8.8 | 2.0 | 29.8% |

| Total (39) PAs | 186.8 | 516.9 | 330.2 | +176.8% | 434.2 | 1120.2 | 686.0 | +158.0% | ||

Note: t0 = sum of deforestation extent for 2013–2015 (before peace agreement); t1 = sum of deforestation extent for 2016–2018 (after peace agreement). PAs names within the Colombian Amazon biogeographical region are in italics.

Figure 1.

(a) Box-and-whisker plot of change in deforestation (%) before and after the peace agreement, for protected areas and corresponding buffer zones (10 km); n = 39. The box indicates the lower and upper quartile of data distribution; bold horizontal lines represent the median. The ‘cat’s whiskers’ (vertical dashed line) indicates the highest and lowest values of the distribution, excluding outliers (circles). (b) Confidence intervals (95%), based on ranks (straight vertical lines). Black circles represent the pseudomedian values from the Wilcoxon test.

Figure 2.

Change in deforestation extent (km2) before and after the peace agreement with FARC (2013–2015 vs. 2016–2018) in continental Colombian National Natural Parks and National Natural Reserves and buffer areas (10 km). Dotted line: 2018 enlargement of Serranía de Chiribiquete NNP (not used in calculations). Numbers correspond to protected area IDs, detailed in Table 1. Figure created using ArcGIS software by Esri, used herein under license.

Discussion

Deforestation inside Colombian PAs and in the surrounding buffer areas has accelerated with the onset of peace. Indeed, a narrative has developed about how biodiversity is threatened when peace arrives in areas previously “protected” by conflict57. That narrative, however, misses the point. Although conflict obstructs land development and prevents illegal usage, it cannot guarantee security for biodiversity; it ultimately is dysfunctional and emblematic of more systemic and deep-rooted problems.

Several historic deforestation factors provoked this outcome, but the exit of a powerful actor that controlled a large part of the country exacerbates them. The national government’s systematic weakness in historically managing PAs and their surrounding regions owes to multiple complex and interacting causes. Crucial among these are: the country’s lack of financial, technical, and operational strength towards establishing a historical registry of illegal land occupation; its low capacity of recovering illegally grabbed land, legally and physically; and its administrative centralization that strips autonomy of regional institutions. For instance, the national government failed to ensure a functional institutional presence in several PAs. Neither the country’s law enforcement institutions (National Prosecutorial Office, police, and army) nor the Land Restitution Unit, a special administrative unit responsible for the restitution of forced dispossessed land and displaced people (Law 1448/2011), have been effective. Law enforcement agencies failed to execute the actions granted in the Colombian constitution to public conservation areas. These factors contributed to allow large-scale landowners and other illegal actors to grab land in and around PAs at low risk and establish extensive livestock systems63 (Fig. 3). Cattle ranching is an inexpensive method of securing possession of land by providing proof that the land is in use, which allows criminals to perform land speculation for major profits. Outside PAs, there is urgent need to define a specific policy on land property formalization for parks’ buffer areas.

Figure 3.

Land grabbing in southern Serranía de la Macarena NNP. Large forest patches are converted into pasture to establish livestock and claim land possession (Credits: Fundación para la Conservación y el Desarrollo Sostenible, 2017).

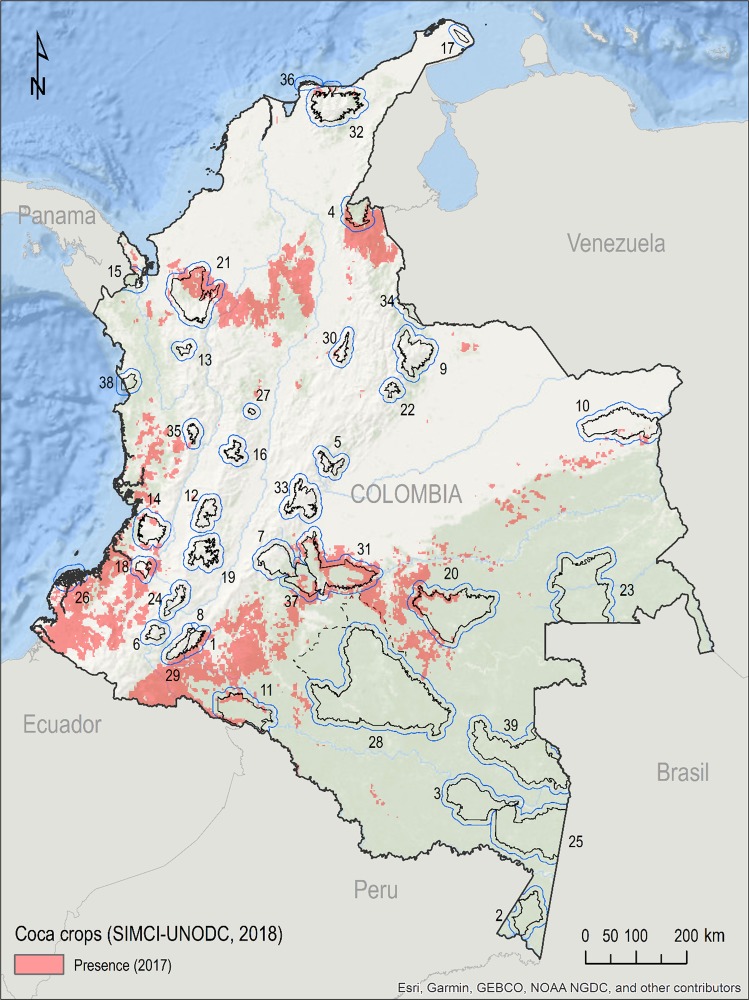

The growing international demand of coca also acts as a key indirect driver of tropical deforestation44. Land area devoted to coca crops increased 4% from 2016 to 2017 within the Colombian system of protected areas, reaching 83 km2 of extension; however, there has been a relative reduction for certain PAs where authorities enlisted local communities to voluntarily substitute illicit crops with legitimate ones44. Fifteen of the analyzed PAs are affected by coca crops; two-thirds are concentrated in the NNPs Serranía de la Macarena (28.3 km2), Paramillo, and the NNR Nukak64 (Fig. 4). Each component of a national park’s local context, including the presence of guerrillas, paramilitary groups, and criminal bands, influences the potential for expansion of illicit crops. Furthermore, governmental limitation of the use of crop control strategies, such as fumigation, factors into the potential incentivization of illicit cropping inside the system of Colombian PAs.

Figure 4.

Presence of coca crops in Colombia in 2017 (source: SIMCI-UNODC, 2018). Protected area boundaries in black, buffer areas (10 km) in blue. Dotted line: 2018 enlargement of Serranía de Chiribiquete NNP (not used in calculations). Numbers correspond to protected area IDs, detailed in Table 1. Figure created using ArcGIS software by Esri, used herein under license.

Historically guerrilla groups, especially FARC, were important actors in both starting and controlling deforestation inside the system of national protected areas. From one side the guerrilla defined the areas for colonization, assigned lands among its social basis, promoted the construction of linear infrastructures and urbanizations (e.g. schools, hospitals), and greatly influenced local productive systems such as livestock and illegal cropping65. Currently, armed groups, especially FARC dissidents, are consolidating within new territories (e.g., in Tinigua NNP), by assigning land to farmers within and close to protected areas and promoting livestock and coca crops as an economic engine of the colonization process. These groups are re-activating old tracks used during the past conflict and opening new ones, to create a political-military transportation network. This territorial-control strategy allows consolidating a social basis for these armed groups, economic inputs for rearmament, and a population exploiting this ‘territorial security’, which also represents a source of recruitment for the guerrillas37. A new long-term cycle of violence is potentially incubating in these regions. At the same time, competing paramilitary groups operate with analogous behavior, establishing in areas where African oil palms (Elaeis guineensis) and cattle ranching are dominating, such as the low watershed of Ariari river and the towns of Puerto Lleras and San José del Guaviare (Meta department).

The current Colombian legislation regarding land planning is stratified in time and in assigning tasks and responsibilities to different institutions, while at the same time presenting often degrees of contradictions toward its objectives and plans. Especially because of its ‘strategic adaptation’ to the conflict, the Colombian government system historically presents low levels of law enforcement in rural areas66. This adaptation focused on social consensus towards territorial management, but under the tutelage of the armed actors of the region that were, and in many cases still are, the real owners of the decisional power within determined regions. Consequently, the system of protected areas of Colombia needs a radical transformation and development, to acquire effective enforcement of existing laws against the illegal use of natural resources and for the recovery of grabbed land. Additionally, in the current postconflict scenario, especially the ‘Victims and Lands Restitution Law’ that states that those who have been dispossessed of their lands or forced to abandon them because of the conflict have the right to their restitution, could generate a new flux of people in areas surrounding the protected areas. On the other hand, this can represent a precious opportunity for an exercise of land formalization, which would re-establish the role of the government over the illegal actors that are grabbing public land. Moreover, local population in Colombia has in general a low level of participation to decision making with regard to the use of natural resources -in the areas where it is allowed-, due to the country’s low development of participative policies and a weak capacity of financial investment and economic incentives in marginal areas.

While the specifics of Colombia may be unique, there are some general lessons that could apply to post-conflict regions characterized by poor governance. In Colombia and elsewhere following a peace settlement, it is essential that governments make a coordinated effort among all involved agencies to establish an effective physical and legal presence within and around conservation areas. Ecological restoration plans, necessary actions for degraded parks, should not just pursue strictly ecological objectives, but they should represent a clear return of the State’s institutions in the protected territories. Between PAs and unprotected land it is of primary importance to reestablish the regional ecological connectivity, at the basis of the processes that regulate at large scale the maintenance and formation of biodiversity, and that would allow Colombia to meet international commitments targets, among others, the objectives of Aichi Target 1167. Outside protected areas, the establishment of differential property tax regimes would reward with incentives sustainable forest use, and conversely disincentive the widely diffused unproductive cattle ranching. Degraded and low productivity areas should be at the focus of a new policy of productive restoration68.

The government’s presence cannot focus solely on the protection of biodiversity; it must also consider the broader social and economic needs of the local communities around PAs. Economic development is a pivotal way not only to prevent the expansion of illegal activities, but also to reduce deforestation. Government incentives that support sustainable use of forests are therefore imperative45. Furthermore, when security conditions permit, ecotourism presents an opportunity for local economic development within buffer zones or in PAs where legislation would allow it. Initial data already shows that in post-conflict Colombia, the number of tourists has been increasing, as well as the number of people visiting national parks69. This demonstrates a promising result of peace.

Exacerbated by the failure of government systems and targeted economic incentives, we face deforestation and loss of biodiversity worldwide. In Colombia, the presence of rich natural resources abused for economic growth coupled with the absence of effective governance allowed for significant recklessness. This study demonstrates an important lesson – substantial, additional support for conservation efforts and economic stabilization is imperative as regions transition from conflict to peace. When society emerges from a long period of conflict, and as economic activities resume, an uptick in deforestation is a likely and foreseeable outcome. This consequence can occur post-conflict, as in Colombia and Vietnam70, after the collapse of a government (e.g., the Soviet Union), or after the discovery of abundant resources in a politically weak state (e.g., oil in Nigeria). Nations undergoing such transitions require assistance to quickly re-establish protections for the natural environment. Creative bilateral agreements (e.g., debt-for-nature swaps) are a start, but aid is also needed (e.g., financial grants, technical support, policy expertise) to support governments in repatriating displaced people to their rightful lands and to restore effective rule of law within and outside conservation areas. Forests and natural systems are assets with the potential to deliver resilience and sustainable benefits to society long beyond short-term profits. Their effective conservation requires an integrative, comprehensive understanding of local communities’ needs, sustainable development, and long-term management.

Methods

Deforestation and protected areas data

We selected two time periods for our analysis: 2013–2015 (during conflict) and 2016–2018 (post-conflict). Deforestation data was obtained from the Global Forest Change dataset, which uses Landsat 8 OLI imagery to detect forest extent and change58. The raster data layer used was Year of gross forest cover loss event (lossyear), which provided events of deforestation at a spatial resolution of 30 m × 30 m. All deforestation pixels referring to years not included in the analysis were excluded. Protected areas’ boundaries in geographic information systems (GIS) shapefile format were obtained from the Colombian National Natural Parks institution (http://mapas.parquesnacionales.gov.co/). Only continental forested NNPs and NNRs were selected from the database (n = 39). The 10-km buffer areas around PAs were produced in QGIS71 with ad-hoc routines in Python programming language to avoid buffer overlaps and double counting (Supplementary information, S1). All layers were projected to a common projection system, MAGNA-SIRGAS/Colombia Bogota zone (EPSG: 3116).

Calculation of statistics

We used the reduceRegion function in Google Earth Engine72 to iteratively calculate the loss for each feature’s bounded area by year (Supplementary information, S2). We then calculated percentage change in deforestation areas for each PA as follows (Eq. 1):

| 1 |

We performed the same analysis for the 10-km buffer zones around each PA. Graphical outputs were derived using ArcGIS 10.4.1. Boxplot (Fig. 2) and statistical tests were performed in R language73 using the boxplot and wilcox.test routines, respectively. Table 1 shows detailed statistics of each PA and associated buffer.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was developed at a workshop during the event “Sustainability, conservation and resilience: strategies for the Colombian post-conflict,” held March 14–16, 2018, and organized under the leadership of M. Linares and N. Clerici, Faculty of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, Universidad del Rosario. We acknowledge Dr. Marius Bottin for help with GIS data layer creation and statistics retrieval. We thank Adam Goulston, MS, ELS, from Edanz Group for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Author contributions

N.C. and M.L. conceived the project; N.C., P.K., D.A. designed the study; N.C., P.K., D.A., J.P.R-D., C.H. analyzed the data and results. N.C., P.K., D.A. and R.B. led the writing. N.C., D.A., P.K., R.B., J.P.R-D., G.F-M., J.O., C.P., L.S., C.L., C.G., M.L.,C.H., D.B participated in the discussion and editing of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-61861-y.

References

- 1.Gaynor KM, et al. War and wildlife: linking armed conflict to conservation. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016;14:533–542. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanson T, et al. Warfare in biodiversity hotspots. Conserv. Biol. 2009;23:578–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Machlis GE, Hanson T. Warfare ecology. BioScience. 2008;58:729–736. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ordway EM. Political shifts and changing forests: Effects of armed conflict on forest conservation in Rwanda. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2015;3:448–60. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alvarez M. Forests in the time of violence: conservation implications of the Colombian war. J. Sustain. For. 2003;16:47–68. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reuveny R, Mihalache-O’Keef AS, Li Q. The effect of warfare on the environment. J. Peace Res. 2010;47:749–761. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jarvie, J., Kanaan, R., Malley, M., Roule, T. & Thomson, J. Conflict Timber: Dimensions of the Problem in Asia and Africa, Volume II, Asian Cases. Final report submitted to the United States Agency for International Development. Burlington, VT: ARD. (2003).

- 8.Baker, M. et al. Conflict timber: Dimensions of the problem in Asia and Africa, Volume III, African cases. Final report submitted to the United States Agency for International Development. Burlington, VT: ARD, https://rmportal.net/library/content/conflict/ARD-ConflictTimber-Vol3-Asia-Africa-PNACT464.pdf/view (2003)

- 9.Adano WR, Dietz T, Witsenburg K, Zaal F. Climate change, violent conflict and local institutions in Kenya’s drylands. J. Peace Res. 2012;49:65–80. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beyers RL, et al. Resource wars and conflict ivory: the impact of civil conflict on elephants in the Democratic Republic of Congo – the case of the Okapi Reserve. PLoS ONE. 2001;6:e27129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baral N, Heinen J. The Maoist people’s war and conservation in Nepal. Polit. Life Sci. 2005;24:2–11. doi: 10.2990/1471-5457(2005)24[2:TMPWAC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dudley JP, Ginsberg JR, Plumptre AJ. Effects of war and civil strife on wildlife and wildlife habitats. Conserv. Biol. 2002;16:319–29. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aveling, R., Anthem, H. & Lanjouw, A. A fighting chance: can conservation create a platform for peace within cycles of human conflict? (Eds. Leader-Williams, N., Adams, W. M. & Smith, R. J.), Trade-Offs in Conservation: Deciding What to Save 253–255 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010).

- 14.Witmer FDW. Detecting war-induced abandoned agricultural land in northeast Bosnia using multispectral, multitemporal Landsat TM imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2008;29:3805–3831. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hallagan JB. Elephants and war in Zimbabwe. Oryx. 1981;16:161–64. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim KC. Preserving biodiversity in Korea’s demilitarized zone. Science. 1997;278:242–43. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaimowitz D, Fauné A. Contras and comandantes. J. Sustain. For. 2003;16:21–46. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burgess R, Miguel E, Stanton C. War and deforestation in Sierra Leone. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015;10(2015):095014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yin H, et al. Agricultural abandonment and re-cultivation during and after the Chechen Wars in the northern Caucasus. Global Environ. Chang. 2019;55:149–159. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baumann M, Radeloff VC, Avedian V, Kuemmerle T. Land-use change in the Caucasus during and afte the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Reg Environ Change. 2015;15(8):1703–1716. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harding, A. How wars and poverty have saved DR Congo’s forests. BBC, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-16037543 (2011).

- 22.Enaruvbe GO, Keculah KM, Atedhor GO, Osewole AO. Armed conflict and mining induced land-use transition in northern Nimba County, Liberia. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2019;17:e00597. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grima N, Singh SJ. How the end of armed conflicts influence forest cover and subsequently ecosystem services provision? An analysis of four case studies in biodiversity hotspots. Land Use Policy. 2019;81:267–75. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorsevski V, Geores M, Kasischke E. Human dimensions of land use and land cover change related to civil unrest in the Imatong Mountains of South Sudan. Appl. Geogr. 2013;38:64–75. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sesnie SE, Gessler P, Finegan B, Thessler S. Integrating Landsat TM and SRTM-DEM derived variables with decision trees for habitat classification and change detection in complex neotropical environments. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008;112:2145–59. [Google Scholar]

- 26.UNODC- United Nations Office for Drugs and Crime, 2015. World Drug Report 2015. (United Nations publication, Sales No. E.15.XI.6). eISBN: 978-92-1-057300-9

- 27.Armenteras D, Rodriguez N, Retana J. Landscape dynamics in northwestern Amazonia: an assessment of pastures, fire and illicit crops as drivers of tropical deforestation. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clerici N, et al. Peace in Colombia is a critical moment for Neotropical connectivity and conservation: Save the northern Andes-Amazon biodiversity bridge. Conserv. Lett. 2018;12:e12594. [Google Scholar]

- 29.McSweeney K, et al. Drug policy as conservation policy: narco-deforestation. Science. 2014;343:489–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1244082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Negret PJ, et al. Emerging evidence that armed conflict and coca cultivation influence deforestation patterns. Biol. Conserv. 2019;239:108176. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fergusson, L., Romero, D. & Vargas, J. F. The Environmental Impact of Civil Conflict: The Deforestation Effect of Paramilitary Expansion in Colombia. Serie Documentos CEDE No. 2014-36. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2516512 (2014).

- 32.Dourojeanni M. Environmental impact of coca cultivation and cocaine production in the Amazon region of Peru. Bull. Narc. 1992;44(2):37–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salisbury D, Fagan C. Coca and conservation: cultivation, eradication and trafficking in the Amazon borderlands. GeoJournal. 2011;78:41–60. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dávalos LM, Sanchez KM, Armenteras D. Deforestation and coca cultivation rooted in twentieth-century development projects. Bioscience. 2016;66:974–982. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biw118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rincón-Ruiz A, Kallis G. Caught in the middle, Colombia’s war on drugs and its effects on forest and people. Geoforum. 2013;46:60–78. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nkonya, E., Johnson, T., Kwon, H. Y. & Kato E., Economics of Land Degradation in Sub-Saharan Africa in: Economics of Land Degradation and Improvement – A Global Assessment for Sustainable Development (ed. Nkonya, E., Mirzabaev, A. & von Braun, J.) 215–259 (Springer, 2016).

- 37.Murillo Sandoval, P. J., Van Dexter, K., Van Den Hoek, J. & Wrathall, D. The end of gunpoint conservation: Forest disturbance after the Colombian peace agreement. Environ Res Lett. in press, 10.1088/1748-9326/ab6ae3 (2020).

- 38.Etter A, Mcalpine C, Possingham H. Historical Patterns and Drivers of Landscape Change in Colombia Since 1500: A Regionalized Spatial Approach. An. Assoc. Amer. Geog. 2008;98:2–23. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Armenteras D, Espelta JM, Rodríguez N, Retana J. Deforestation dynamics and drivers in different forest types in Latin America: Three decades of studies (1980–2010) Global Environ. Chang. 2017;46:139–147. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Etter A, McAlpine C, Wilson K, Phinn S, Possingham H. Regional patterns of agricultural land use and deforestation in Colombia. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 2006;114:369–386. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Armenteras D, Cabrera E, Rodríguez N, Retana J. National and regional determinants of tropical deforestation in Colombia. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2013;13:1181–1193. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dávalos LM, Holmes JS, Rodríguez N, Armenteras D. Demand for beef is unrelated to pasture expansion in northwestern Amazonia. Biol Conserv. 2014;170:64–73. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Armenteras D, Rodríguez N, Retana J, Morales M. Understanding deforestation in montane and lowland forests of the Colombian Andes. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2011;11:693–705. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dávalos LM, et al. Forests and Drugs: Coca-Driven Deforestation in Tropical Biodiversity Hotspots. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45:1219–1227. doi: 10.1021/es102373d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chadid M, Dávalos L, Molina J, Armenteras D. A Bayesian Spatial Model Highlights Distinct Dynamics in Deforestation from Coca and Pastures in an Andean Biodiversity Hotspot. Forests. 2015;6:3828–3846. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Armenteras D, Rudas G, Rodríguez N, Sua S, Romero M. Patterns and causes of deforestation in the Colombian Amazon. Ecol Indic. 2006;6(2):353–368. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dávalos L. The San Lucas mountain range in Colombia: how much conservation is owed to the violence? Biodivers. Conserv. 2001;10:69–78. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Forero-Medina G, Joppa L. Representation of Global and National Conservation Priorities by Colombia’s Protected Area Network. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(10):e13210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Joppa LN, Loarie SR, Pimm SL. On the protection of “protected areas”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:6673–6678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802471105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coad L, et al. Widespread shortfalls in protected area resourcing undermine efforts to conserve biodiversity. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2019;17(5):259–264. [Google Scholar]

- 51.DeFries R, Hansen A, Newton AC, Hansen MC. Increasing Isolation of Protected Areas in Tropical Forests over the past Twenty Years. Ecol. Appl. 2005;15:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Joppa LN, Pfaff A. Reassessing the forest impacts of protection: The challenge of nonrandom location and a corrective method. Ann Ny Acad Sci. 2010;1185:135–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gray CL, et al. Local biodiversity is higher inside than outside terrestrial protected areas worldwide. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12306. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Armenteras D, Rodriguez N, Retana J. Are conservation strategies effective in avoiding the deforestation of the Colombian Guyana Shield? Biol. Conserv. 2009;142:1411–1419. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rodriguez N, Armenteras D, Retana J. Land use and land cover change in the Colombian Andes: dynamics and future scenarios. J. Land Use Sci. 2012;7:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Comisionado para la Paz Acuerdo final para la terminación del conflicto y la construcción de una paz estable y duradera. available at, http://www.altocomisionadoparalapaz.gov.co/procesos-y-conversaciones/acuerdo-general/Paginas/inicio.aspx (2016).

- 57.Reardon S. FARC and the forest: peace is destroying Colombia’s jungle - and opening it to science. Nature. 2018;558:169–170. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-05397-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hansen MC, et al. High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. Science. 2013;342:850–853. doi: 10.1126/science.1244693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Prugh LR, Hodges KE, Sinclair ARE, Brashares JS. Effect of habitat area and isolation on fragmented animal populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:20770–20775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806080105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Laurance WF, et al. Averting biodiversity collapse in tropical forest protected areas. Nature. 2012;489:290–294. doi: 10.1038/nature11318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Giam X. Global biodiversity loss from tropical deforestation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:5775–5777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706264114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Solar RR, et al. How pervasive is biotic homogenization in human‐modified tropical forest landscapes? Ecol. Lett. 2015;18:1108–1118. doi: 10.1111/ele.12494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Walker NF, Patel SA, Kalif KAB. From Amazon pasture to the High Street: deforestation and the Brazilian cattle product supply chain. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2013;6:446–467. [Google Scholar]

- 64.SIMCI-UNODC- Sistema Integrado de Monitoreo de Cultivos Ilícitos (SIMCI)-Oficina de las Naciones Unidas contra la Droga y el Delito (UNODC) Informe de Monitoreo de Territorios Afectados por Cultivos Ilícitos, 2017. Available at, https://www.unodc.org/documents/crop-monitoring/Colombia/Colombia_Monitoreo_territorios_afectados_cultivos_ilicitos_2017_Resumen.pdf (2018).

- 65.Rincón-Ruiz A, Correa HL, León DO, Williams S. 2016. Coca cultivation and crop eradication in Colombia: The challenges of integrating rural reality into effective anti-drug policy. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2016;33:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Berry A. Legal, political and economic aspects of the tragedy in rural Colombia in recent decades: hypothesis for analysis. Estud. Socio-Juríd. 2014;16(1):25–41. [Google Scholar]

- 67.GBO-4, Global Biodiversity Outlook. 2014. Pyeongchang, Korea, https://www.cbd.int/gbo4/.

- 68.Lerner AM, Zuluaga AF, Chará J, Etter A, Searchinger T. Sustainable Cattle Ranching in Practice: Moving from Theory to Planning in Colombia’s Livestock Sector. Environ. Manage. 2017;60:176–184. doi: 10.1007/s00267-017-0902-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ministerio de Comercio, Industria y Turismo de Colombia. Informes de Turismo, http://www.mincit.gov.co/estudios-economicos/estadisticas-e-informes/informes-de-turismo (2018).

- 70.Yen P, Ziegler S, Huettmann F, Onyeahialam AI. Change detection of forest and habitat resources from 1973 to 2001 in Bach Ma National Park, Vietnam, using remote sensing imagery. Int For Rev. 2005;7:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 71.QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. http://qgis.osgeo.org (2019).

- 72.Gorelick N, et al. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017;202:18–27. [Google Scholar]

- 73.R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing, http://www.R-project.org R Foundation for Statistical Computing, (2018).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.