Abstract

One of the more challenging aspects of ECG interpretation is measurement and interpretation of the QT interval. This interval represents the time taken for the ventricles to completely repolarise after activation. Abnormal prolongation of the QT interval can lead to torsades de pointes, a form of potentially life-threatening polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT). Detection of a prolonged QT interval is essential as this can be a reversible problem, particularly in the context of the use of a variety of commonly prescribed medications in the hospital setting. Automated ECG printouts cannot be relied upon to diagnose QT interval prolongation; thus, the onus is on the clinician to identify it. This is a difficult task, as the normal QT interval is typically measured relative to the heart rate. Therefore, the QT interval often requires “correction” for the current heart rate, in order to correctly stratify the risk of torsades de pointes. A wealth of correctional formulae have been derived, but none has proven superior. We present an approach to the ECG in this context, and a step-by-step guide to manually measuring and correcting the QT interval, and an approach to management in common hospital-based clinical scenarios.

KEY WORDS: torsades de pointes, QT interval, electrocardiogram, antipsychotics, antiarrhythmics

INTRODUCTION

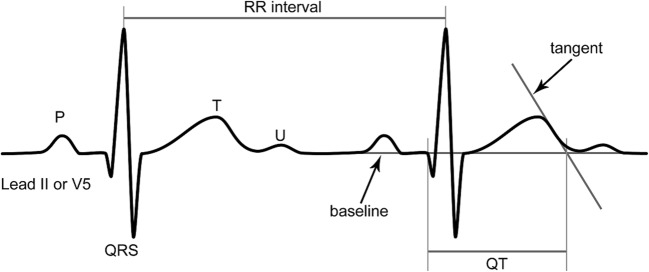

The QT interval represents the duration of time taken from the onset of ventricular depolarisation to the end of ventricular repolarisation as seen on the electrocardiogram (ECG, see Fig. 1). This translates to the very beginning of the QRS complex, to the end of the T wave. Prolongation of the QT interval is associated with torsades de pointes (TDP), a form of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia which, in certain cases, can lead to fatal ventricular fibrillation. Prolongation of the QT interval has also been associated with an increased risk of atrial fibrillation.1

Figure 1.

The tangent technique for determining the end of the QT interval. Adapted from Postema et al.10

Additionally, the normal limit for the QT interval varies with heart rate. During tachycardia, the QT interval decreases, and in bradycardia, it lengthens. Thus, there is a requirement to “correct” the QT interval, particularly in hospital settings where the resting heart rates of patients may not be normal. The corrected QT interval is known as QTc, and it is prolongation of the QTc, rather than the QT, that determines the risk of TDP.

The QTc is prolonged in patients with congenital long QT syndrome (CLQTS). CLQTS includes sixteen identified genetic abnormalities that give rise to abnormal myocardial repolarisation. The management of CLQTS includes avoidance of classic arrhythmia triggers, particularly swimming or water sports. Beta blocker therapy is the mainstay of treatment, and the use of implantable cardioverter/defibrillators is necessary in selected patients assessed to be at high risk of TDP.2

Long QT syndrome may also be acquired in the setting of cardiomyopathy, myocardial ischaemia, severe intracranial injury, electrolyte abnormalities and several medications including, but not limited to, various antimicrobials, antipsychotics, antidepressants, antiarrhythmics and antiemetics (Table 1). Thus, risk stratification of patients with a prolonged QTc is a common challenge in hospital practice.

Table 1.

Commonly Used Medications and Their Risk of Torsades de pointes (TDP)

| Medication class | Known risk of TDP | Conditional risk | Possible risk | QT neutral |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antiarrhythmics |

Sotalol Disopyramide Flecainide Procainamide |

Amiodarone* Propafenone |

- | Mexiletine |

| Antipsychotics |

Haloperidol Iloperidone Ziprasidone Quetiapine |

Olanzapine |

Risperidone Aripiprazole |

Lurasidone |

| Antidepressants |

Escitalopram Citalopram Tricyclic antidepressants |

- | Venlafaxine | Sertraline |

| Antibiotics |

Azithromycin Ciprofloxacin Levofloxacin Moxifloxacin Clarithromycin Erythromycin Roxithromycin Pentamidine |

Mefloquine Norfloxacin |

Metronidazole Piperacillin/ tazobactam |

Aminoglycosides Beta lactams Daptomycin Trimethoprim Fosfomycin Glycopeptides Lincosamides Linezolid Nitrofurantoin Rifamycins Tetracyclines |

| Antifungals |

Fluconazole Pentamidine |

Itraconazole Ketoconazole Posaconazole Voriconazole |

Amphotericin B |

Echinocandins (anidulafungin, caspofungin, micafungin) Flucytosine Pentamidine |

| Antiemetics |

Domperidone Ondansetron Prochlorperazine |

Metoclopromide |

Cyclizine Promethazine Hyoscine hydrobromide Levomepromazine Aprepitant |

|

| Antihistamines |

Loratadine Dimenhydrinate |

Hydroxyzine | Diphenhydramine |

Brompheniramine Cyclizine Cyproheptadine Dexchlorpheniramine Diphenhydramine Doxylamine Pheniramine Promethazine |

The evaluation of the QT interval requires:

Selection of the appropriate ECG lead

Accurate manual measurement of the QT interval

Correction for the heart rate by application of an established formula OR comparison to a nomogram

Evaluation of the QT interval is contentious due to the following factors:

ECG machine measurements of the QT interval are often inaccurate

Variable descriptions exist on the technique of measurement of the QT interval

The lack of a universally accepted formula for correction

This article will address the above and provide a guide for general physicians, junior doctors and other medical practitioners for QT interval measurement, interpretation and management of prolongation.

NORMAL AND ABNORMAL VALUES

In the absence of a broad QRS complex, which may be seen in bundle branch blocks and paced rhythms, the 99th percentile of the QTc is 470 milliseconds (ms) for men and 480 ms for women.3 It is generally accepted that a QTc above 500 ms is a risk factor for TDP.

INACCURACIES OF QT MEASUREMENT

The majority of ECG machines provide an automated calculation of several ECG parameters including the raw and corrected QT interval. Large studies have shown the sensitivity of automated ECG algorithms to be below 50% for detecting prolonged QT intervals.4, 5 Studies comparing manual with computerised calculation have returned findings favouring manual assessment by trained observers;6 however, in a large study of 902 physicians, less than 50% of cardiologists and less than 40% of other physicians were able to correctly identify a prolonged QT interval.7 Thus, it is imperative that clinicians are able to measure the QT interval correctly, given the inaccuracies of automated measurement.

MANUAL MEASUREMENT OF QTC

Text Box 1. The three steps required to correctly measure the QTc

|

1. Select the appropriate ECG lead (usually II or V5) 2. Manually measure the QT interval (the duration from the start of the QRS complex to the end of the T wave) 3. Apply a correctional formula or use the QT nomogram to adjust for the current heart rate |

Selection of the Appropriate Lead

The QT interval will vary depending on which ECG lead is examined. This difference, termed QT dispersion, can range up to 60 ms in some individuals.8 It has been recommended that gold-standard QT calculations be based upon the average of all 12 leads; however, this is not a practical solution. Lead II has been conventionally used alone for QTc calculations.8 If the T wave is too flat to measure in lead II, then lead V5 is often used. The American Heart Association recommends using the lead with the most clearly defined T wave.9 Regardless of which lead is selected, this must be kept constant when reviewing serial ECGs of the patient.

Measurement of the QT interval

The QT interval should be measured from the start of the QRS complex to the end of the T wave. If no ruler is available, a simple method is by counting squares. Each small square on a standard ECG corresponds to 40 ms, and thus by using half squares, the precision of this method can be as close as 20 ms.

The determination of the end of the T wave is difficult, as the T wave may often flatten towards its end. For this reason, several authors have supported the use of a “tangent technique” (see Fig. 1), where the steepest part of the T wave curve intersects the baseline.10

CORRECTION OF THE QT INTERVAL

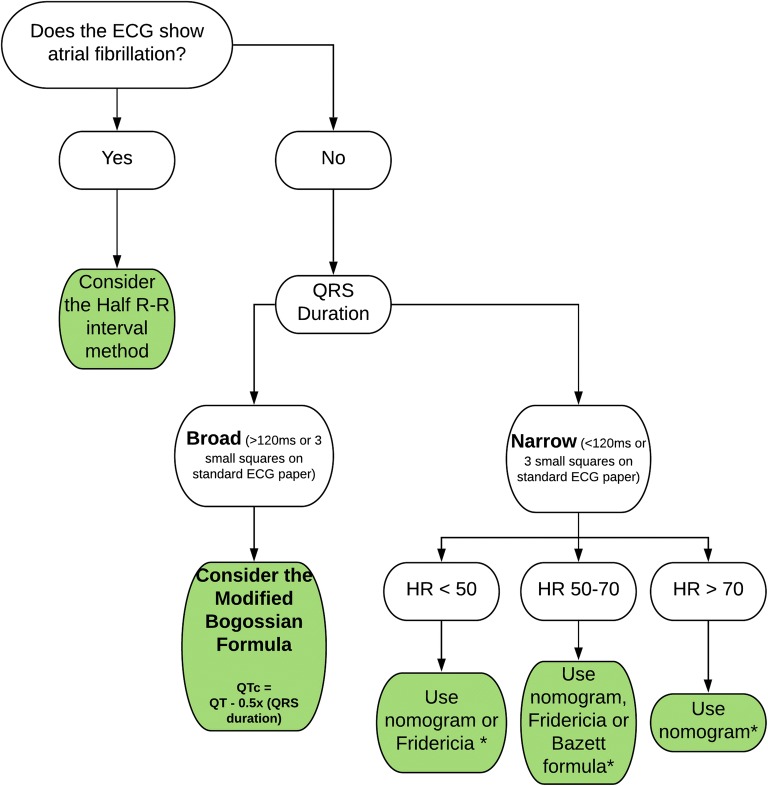

While several correctional formulae exist, none has proven superiority. Figure 2 illustrates options for which formula to use.

Figure 2.

Flowchart for an approach to correcting QT interval. The asterisk indicates Framingham and Hodges formulae can be used in any of these situations, but are complex equations and have been omitted from this flowchart for simplicity. HR, heart rate in beats per minute.

The most widely used formula for calculating the QTc is the Bazett formula, given by where RR denotes the length of time between the QRS complexes (the RR interval). It is commonly abbreviated to QTcB. Despite being criticised for inaccuracy at heart rates outside the normal range,11, 12 this classical formula remains in use due to the lack of a universally accepted alternative. It is often reported on automated printouts from ECG machines.

There are several alternatives to the Bazett formula, but none of these has proven to be superior. They are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Methods for Correction of the QT Interval

| Formula | Equation | Strengths | Limitations | When to use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bazett |

• Simplest formula • Widely accepted and used |

• Tendency to over-diagnose long QT as it overcorrects at high heart rates and undercorrects at low heart rates | • Best used when HR is between 50 and 70 bpm55 | |

| Fridericia | • More accurate than Bazett formula at abnormal heart rates | • Tendency to overcorrect at high heart rates (i.e. over-diagnosis of long QT) | • Useful in bradycardic patients (HR < 50 bpm) | |

| Framingham | QTc = QT + 0.154 (1 − RR) | • Less affected by abnormal heart rate | • Complex formula | • In any patient, especially if heart rate is < 50 bpm or > 70 bpm |

| Hodges | • Least affected by abnormal heart rate56 | • Complex formula | • In any patient, especially if heart rate is < 50 bpm or > 70 bpm | |

| Nomogram | Not applicable (see Fig. 3) | • Designed for use with abnormal heart rates |

• Needs to be physically or digitally available at point of care • Difficult to apply to serial testing |

• Patients with abnormal heart rates • Well described in toxicology and overdose |

| The “Half R-R” method | If QT is less than half the RR interval, it is normal | • No calculation required |

• Non-quantitative • If the QT is greater than half the RR interval, it may still be normal • Cannot be used at HR < 60 bpm |

• Useful as a “screening” test, especially in AF but not as a true diagnostic test. |

RR, the R-R interval, measured in seconds; HR, heart rate; AF, atrial fibrillation

The Nomogram

A nomogram (Fig. 3) has been developed where the heart rate and the uncorrected QT can be plotted. A point plotted above a pre-defined line is associated with a higher risk of TDP. The nomogram, if available, is the simplest method of QT interval interpretation, as there is no need to apply any formulae. The nomogram has been compared with the Bazett formula and has been shown to have equivalent sensitivity and specificity in a systematic review of 129 cases of TDP13, and was less likely to generate false positive results in two retrospective studies.14, 15 The nomogram is not referenced in major guidelines, however, perhaps owing to a lack of prospective predictive studies.

Figure 3.

The QT nomogram. Adapted from Chan et al.15

Prolonged (broad) QRS complex

In the setting of a broad QRS complex, such as in a bundle branch block or a paced rhythm, the QT interval is likely to be prolonged. The simplest and most convenient formula in this case is the Bogossian formula:

Atrial Fibrillation

There remains no consensus strategy on the measurement of the QT interval in atrial fibrillation. This difficulty is due to the constant flux in heart rate. A technique of averaging the QT for five consecutive beats in the ECG has been proposed, although this would be time-consuming for the clinician.16 A “half R-R interval” method is sometimes used where it is stated that if the QT (uncorrected) is less than half of the R-R interval, then the QTc will not be prolonged. This rule has been shown to have 100% sensitivity when the heart rate is 60 beats per minute or above, but it is poorly specific.11 Therefore, if the QT is longer than half the R-R interval, further examination is necessary, as the QTc may still be normal. Thus, it may be appropriate to initially screen the QT interval for five beats with the half R-R rule, due to its ease of use and high sensitivity. If the QT exceeds half the R-R interval, we would recommend using a correctional formula that is less dependent on heart rate (e.g. Hodges or Framingham formulae).

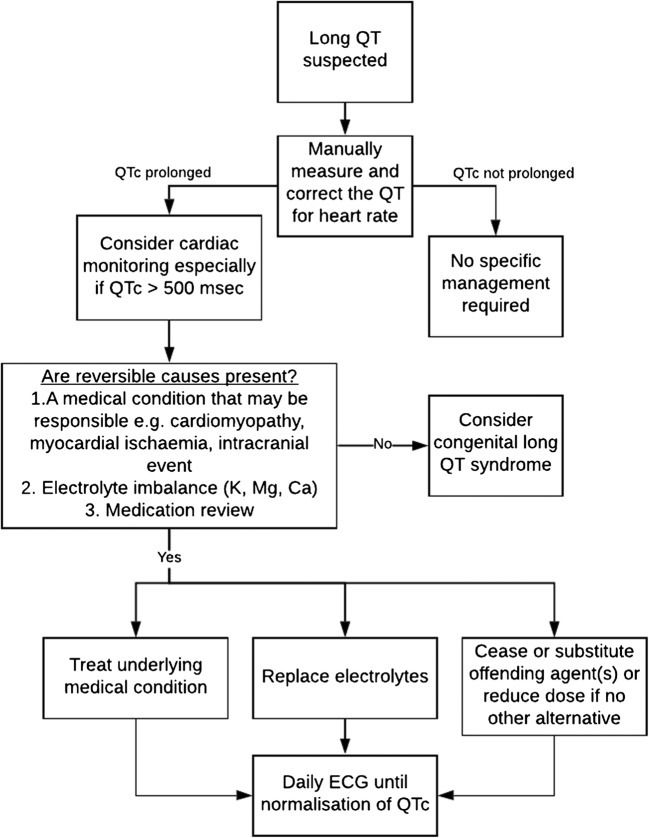

MANAGEMENT OF A PROLONGED QTC

Once a prolonged QTc (> 500 ms) has been identified, the management of the patient will include the following:

Consideration of the underlying cause—which may include congenital long QT syndrome, cardiomyopathy or severe intracranial disease.

Identification of any medications that may have contributed, and cessation, substitution or dose reduction where appropriate (see the “Medication Management Scenarios” section).

Checking electrolyte levels, with replacement where required. Depletion of potassium, magnesium and calcium may cause or exacerbate the QTc prolongation.

Inpatient telemetry where possible, and daily ECGs until the QTc has normalised. Care must be taken to use the same lead and correctional formula for serial ECGs.

This approach is summarised in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Flowchart for investigation and management of a prolonged QTc.

MEDICATION MANAGEMENT SCENARIOS

A table of common drugs that prolong the QT interval is presented in Table 1. This list is not exhaustive, as there are over 250 medications that have demonstrated the potential to lengthen the QT. Conditional risk implies that TDP has been reported to occur only in the presence of another factor or drug that prolongs the QTc. Possible risk means that QTc prolongation has been demonstrated, but an association with TDP has not been proven. Of note, any patient diagnosed with congenital long QT syndrome should never be prescribed any of the agents that increase risk.

Antibiotics

The two main classes of antibiotics that prolong the QTc are macrolides and quinolones. These agents typically offer broad-spectrum coverage of atypical and resistant infections. If a prolonged QTc has developed, then the agent should be substituted, as dose reduction may not provide effective antimicrobial activity. Selection of an alternative agent should be guided by appropriate culture and sensitivity testing where possible, as well as local guidelines and expertise.

Of the macrolides, azithromycin,17, 18 clarithromycin,19, 20 erythromycin21, 22 and roxithromycin23 have all been shown to prolong the QT interval. Doxycycline, a tetracycline antibiotic, should be considered to replace azithromycin or roxithromycin for treatment of atypical pneumonia. If used for treatment of Helicobacter pylori, alternative salvage therapy options are available which include metronidazole or rifabutin rather than clarithromycin.24 The treatment of mycobacterial infections is complex, and an alternative regimen should be discussed with an appropriate specialist.

The quinolones demonstrated to prolong the QTc include ciprofloxacin,25 levofloxacin,26 moxifloxacin27 and ofloxacin.28 Norfloxacin has only been attributed to a possible risk.29 Quinolones primarily target gram-negative bacilli including Pseudomonas aeruginosa; however, gentamicin and piperacillin-tazobactam have a well-established role in treatment of this, and other gram-negative infections, and hence may be reasonable alternatives.24

Antifungal Agents

QT prolongation with antifungal agents presents a difficult clinical scenario. All azoles may increase the risk of QT prolongation.30 Safer agents include echinocandins (e.g. anidulafungin, caspofungin, micafungin) for severe fungal infections, with flucytosine and amphotericin B as alternatives,24 although resistance patterns of the culprit organism are often variable and these may not be appropriate.

Antiemetics

Nausea is a common symptom in hospitalised patients. Multiple antiemetic medications have been associated with TDP including domperidone,31, 32 ondansetron,31 and prochlorperazine.33 Metoclopramide is considered to be of conditional risk.29 QT-neutral alternatives can be prescribed, depending on the context and aetiology of the symptoms. These include cyclizine, promethazine, hyoscine bromide, levomepromazine and aprepitant.

Antihistamines

Two antihistamines, aztemizole and terfenadine, have been removed from the US market due to concerns regarding TDP.29, 34 Currently used drugs that may prolong the QTc include dimenhydrinate 35 and hydroxydine.36 Loratadine has been reported as having a safe profile in this regard.37 Other safe alternatives for consideration include brompheniramine, cyclizine, cyproheptadine, dexchlorpheniramine, doxylamine and promethazine.

Opioid Dependence

Methadone, particularly in high doses, has been associated with QT prolongation.38 In patients who have been stabilised on methadone to treat opioid dependence, substitution to an alternative agent can be challenging. Dose reduction should be the initial consideration, if possible. Buprenorphine is considered a safer option;38 however, if transition between the two agents is considered appropriate, it should be supervised by a chronic pain specialist.

Antidepressants

Different classes of antidepressants vary in their propensity to cause QTc prolongation.39 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are typically the first-line treatment for depression and these are generally considered safe, with the notable exceptions of citalopram and escitalopram, which have been recorded to prolong the QTc in therapeutic doses.40–42 Tricyclic antidepressants were typically linked to significant QT prolongation,39 though recently this association has been questioned.40

Serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) have variable impacts on QTc with prolongation caused by venlafaxine—most significantly in overdose.39–41 The safest antidepressant for cardiac adverse drug effects including QT prolongation is mirtazapine.43

Antipsychotics

There are known patterns of the propensity for psychotropic drugs to cause QT prolongation,40 with the FDA issuing various black box warnings for antipsychotic and antidepressant agents over the past decade.44 QT prolongation appears to be generally dose-dependent and correlates with increased risk of cardiac events45 at a hazard rate of around 1.66 when the QTc is over 500 ms.40 It is known that the risk of QT prolongation increases when combinations of antipsychotics are used, and consultation with a psychiatrist is recommended whenever QT prolongation is confirmed.

Typical antipsychotics carry an increased risk of QTc prolongation compared with atypical antipsychotic medications.40 Haloperidol is used worldwide for behavioural disturbance46 and has ongoing concern around its risk of QTc prolongation and risk of cardiac death.40 A hypothesis exists that haloperidol has a higher propensity for QTc prolongation when delivered intravenously.40 The data for droperidol is conflicting and no consensus has been reached.

Atypical antipsychotic medications can also prolong the QTc interval to a variable extent.40 A recent meta-analysis found that iloperidone and ziprasidone were most likely to prolong the QTc.47 Quetiapine has been shown to have a variable effect on QTc and has been linked with sudden cardiac death.40

Aripiprazole is recommended as having a lower risk of QTc prolongation while lurasidone, a newer atypical antipsychotic, has shown the lowest risk.40, 48

Antiarrhythmic Agents

Amiodarone, flecainide and sotalol can all cause TDP.49 These drugs are three of the most commonly used rhythm control agents in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Less commonly used antiarrhythmics such as disopyramide and procainamide can also have this effect. Amiodarone is generally used as a “last-line” for either rhythm or rate control for supraventricular arrhythmias and as secondary prevention of ventricular tachycardia. Although it is well established that QT prolongation can occur with amiodarone, the overall risk of TDP is less than 1% and when it does occur, it is typically in association with other risk factors for TDP.50 Mexiletine, an infrequently used antiarrhythmic agent, has been shown to shorten the QTc when prolonged.51 Due to the complexity and risk of using these agents, cardiology consultation is recommended whenever QTc prolongation occurs in the setting of an antiarrhythmic medication. An overview of commonly used medications for rate and rhythm control in atrial fibrillation is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Rate and Rhythm Control Agents Used in Atrial Fibrillation

| Medication | Mechanism of action | Risk of QT prolongation* | Contraindications† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rhythm control | |||

| Flecainide | Sodium channel blockade | Known | Structural heart disease, ischaemic heart disease |

| Disopyramide | Sodium channel blockade | Known | Narrow-angle glaucoma, decompensated heart failure |

| Propafenone | Sodium channel blockade | Conditional | Heart failure, ischaemic heart disease asthma, severe COPD, |

| Sotalol | Beta adrenoreceptor and potassium channel blockade | Known | Asthma, renal impairment (creatinine clearance < 40 mL/min), decompensated heart failure |

| Amiodarone | Primarily potassium channel blockade, but also has sodium and calcium channel blocking properties | Conditional | Iodine hypersensitivity. Must be used cautiously in the context of pulmonary, thyroid or hepatic disease due to risk of toxicity to these organs. |

| Rate control | |||

| Atenolol, metoprolol | Beta adrenoreceptor blockade | Not associated | Asthma, hypotension |

| Verapamil, diltiazem | Calcium channel blockade | Not associated | Heart failure, hypotension |

| Digoxin | Inhibition of the sodium/potassium/ATPase pump | Not associated | Hypokalaemia, must be used cautiously in renal impairment due to risk of toxicity |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ATP, adenosine triphosphate

*Severe bradycardia can be caused by any of these agents, and QT prolongation can occur in this context

†All agents listed are contraindicated in the presence of sinus node dysfunction or severe conduction disease, e.g. second- or third-degree AV block, or bifascicular and trifascicular block

Antineoplastic Agents

Certain antineoplastic agents are known to cause QTc prolongation. Arsenic trioxide, used to treat acute promyelocytic leukaemia, has been associated with QTc prolongation in approximately 20% of patients, although the overall risk of TDP remains low.52 Tyrosine kinase inhibitors are used to treat a variety of malignancies, and several have been linked with QTc prolongation and TDP. The drugs with reports of QTc prolongation include nilotinib, sunitinib, vemurafenib and vandetanib. It should be noted that a large number of tyrosine kinase inhibitors do not prolong the QTc.52 It is recommended that advice from an oncologist is sought if it is suspected that a chemotherapeutic agent has caused QTc prolongation, as substitution of treatment is a complex decision.

Anaesthetic Agents

Inhaled anaesthetic agents such as isoflurane, sevoflurane and desflurane have been associated with QTc prolongation.53 These short-acting agents should be used cautiously in patients with pre-existing QTc prolongation at baseline, with cardiac monitoring suggested. Evidence suggests propofol has minimal effect on the QTc.54

CONCLUSION

Measurement of the QT interval is a required skill for hospital doctors, as the triggers for QTc prolongation such as drugs and electrolyte depletion are common in inpatient settings. By using the methods outlined above, clinicians can confidently measure and correct the QT interval and thus estimate the risk of torsades de pointes in patients. Additionally, knowledge of drugs that may be responsible, and safer alternatives, is paramount to appropriately managing this common and often challenging clinical scenario.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zhang N, Gong M, Tse G, et al. Prolonged corrected QT interval in predicting atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2018;41:321–7. doi: 10.1111/pace.13292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah SR, Park K, Alweis R, Long QT. Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature and Current Evidence. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2019;44:92–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2018.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taggart NW, Haglund CM, Tester DJ, Ackerman MJ. Diagnostic miscues in congenital long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2007;115:2613–20. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.661082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garg A, Lehmann MH. Prolonged QT interval diagnosis suppression by a widely used computerized ECG analysis system. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6:76–83. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.112.976803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Talebi S, Azhir A, Zuber S, et al. Underestimated and unreported prolonged QTc by automated ECG analysis in patients on methadone: can we rely on computer reading? Acta Cardiol. 2015;70:211–6. doi: 10.1080/ac.70.2.3073513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isbister GK, Calver L, Van Gorp F, Stokes B, Page CB. Inter-rater reliability of manual QT measurement and prediction of abnormal QT,HR pairs. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2009;47:884–8. doi: 10.3109/15563650903333820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viskin S, Rosovski U, Sands AJ, et al. Inaccurate electrocardiographic interpretation of long QT: the majority of physicians cannot recognize a long QT when they see one. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:569–74. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salvi V, Karnad DR, Kerkar V, et al. Choice of an alternative lead for QT interval measurement in serial ECGs when Lead II is not suitable for analysis. Indian Heart J. 2012;64:535–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2012.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drew BJ, Ackerman MJ, Funk M, et al. Prevention of Torsade de Pointes in Hospital Settings: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology FoundationEndorsed by the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses and the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. Circulation. 2010;121:1047–60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Postema PG, De Jong JS, Van der Bilt IA, Wilde AA. Accurate electrocardiographic assessment of the QT interval: teach the tangent. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1015–8. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berling I, Isbister GK. The Half RR Rule: A Poor Rule of Thumb and Not a Risk Assessment Tool for QT Interval Prolongation. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22:1139–44. doi: 10.1111/acem.12752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sagie A, Larson MG, Goldberg RJ, Bengtson JR, Levy D. An improved method for adjusting the QT interval for heart rate (the Framingham Heart Study) Am J Cardiol. 1992;70:797–801. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)90562-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waring WS, Graham A, Gray J, Wilson AD, Howell C, Bateman DN. Evaluation of a QT nomogram for risk assessment after antidepressant overdose. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70:881–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03728.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Isbister GK, Page CB. Drug induced QT prolongation: the measurement and assessment of the QT interval in clinical practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;76:48–57. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan A, Isbister GK, Kirkpatrick CM, Dufful SB. Drug-induced QT prolongation and torsades de pointes: evaluation of a QT nomogram. Qjm. 2007;100:609–15. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcm072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tooley J, Ouyang D, Hadley D, et al. Comparison of QT Interval Measurement Methods and Correction Formulas in Atrial Fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2019;123:1822–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi Y, Lim HS, Chung D, Choi JG, Yoon D. Risk Evaluation of Azithromycin-Induced QT Prolongation in Real-World Practice. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:1574806. doi: 10.1155/2018/1574806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Z, Prinsen JK, Bersell KR, et al. Azithromycin Causes a Novel Proarrhythmic Syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2017;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Chang NL, Shah P, Bikkina M, Shamoon F. Clarithromycin-Induced Torsades de Pointes. Am J Ther. 2016;23:e955–6. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000000109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vieweg WV, Hancox JC, Hasnain M, Koneru JN, Gysel M, Baranchuk A. Clarithromycin, QTc interval prolongation and torsades de pointes: the need to study case reports. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2013;1:121–38. doi: 10.1177/2049936113497203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fiets RB, Bos JM, Donders A, et al. QTc prolongation during erythromycin used as prokinetic agent in ICU patients. Eur J Hosp Pharm Sci Pract. 2018;25:118–22. doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2016-001077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giudicessi JR, Ackerman MJ, Camilleri M. Cardiovascular safety of prokinetic agents: A focus on drug-induced arrhythmias. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30:e13302. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Justo D, Mardi T, Zeltser D. Roxithromycin-induced torsades de pointes. Eur J Intern Med. 2004;15:326–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.eTG complete (Therapeutic Guidelines). Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd., 2015. at http://online.tg.org.au.ezproxy.library.uq.edu.au/ip/desktop/index.htm.)

- 25.Briasoulis A, Agarwal V, Pierce WJ. QT prolongation and torsade de pointes induced by fluoroquinolones: infrequent side effects from commonly used medications. Cardiology. 2011;120:103–10. doi: 10.1159/000334441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kervezee L, Gotta V, Stevens J, et al. Levofloxacin-Induced QTc Prolongation Depends on the Time of Drug Administration. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2016;5:466–74. doi: 10.1002/psp4.12085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khan F, Ismail M, Khan Q, Ali Z. Moxifloxacin-induced QT interval prolongation and torsades de pointes: a narrative review. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2018;17:1029–39. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2018.1520837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frothingham R. Rates of torsades de pointes associated with ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, levofloxacin, gatifloxacin, and moxifloxacin. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21:1468–72. doi: 10.1592/phco.21.20.1468.34482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.www.Crediblemeds.org, QTdrugs List. 2019. (Accessed June 25 2019,

- 30.Salem M, Reichlin T, Fasel D, Leuppi-Taegtmeyer A. Torsade de pointes and systemic azole antifungal agents: Analysis of global spontaneous safety reports. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2017;2017:11. doi: 10.21542/gcsp.2017.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frommeyer G, Fischer C, Ellermann C, et al. Severe Proarrhythmic Potential of the Antiemetic Agents Ondansetron and Domperidone. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2017;17:451–7. doi: 10.1007/s12012-017-9403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Field J, Wasilewski M, Bhuta R, et al. Effect of Chronic Domperidone Use on QT Interval: A Large Single Center Study. J Clin Gastroenterol 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Wu CS, Tsai YT, Tsai HJ. Antipsychotic drugs and the risk of ventricular arrhythmia and/or sudden cardiac death: a nation-wide case-crossover study. J Am Heart Assoc 2015;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Yap YG, Camm AJ. Potential cardiac toxicity of H1-antihistamines. Clin Allergy Immunol. 2002;17:389–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shah A, Yousuf T, Ziffra J, Zaidi A, Raghuvir R. Diphenhydramine and QT prolongation - A rare cardiac side effect of a drug used in common practice. J Cardiol Cases. 2015;12:126–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jccase.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vigne J, Alexandre J, Fobe F, et al. QT prolongation induced by hydroxyzine: a pharmacovigilance case report. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;71:379–81. doi: 10.1007/s00228-014-1804-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olasińska-Wiśniewska A, Olasiński J, Grajek S. Cardiovascular safety of antihistamines. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31:182–6. doi: 10.5114/pdia.2014.43191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wedam EF, Bigelow GE, Johnson RE, Nuzzo PA, Haigney MC. QT-interval effects of methadone, levomethadyl, and buprenorphine in a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2469–75. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.22.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taylor D PC, Kapur S. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry (12th ed). Hoboken, USA: Wiley; 2015.

- 40.Beach SR, Celano CM, Sugrue AM, et al. QT Prolongation, Torsades de Pointes, and Psychotropic Medications: A 5-Year Update. Psychosomatics. 2018;59:105–22. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malhi GS, Bassett D, Boyce P, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49:1087–206. doi: 10.1177/0004867415617657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ojero-Senard A, Benevent J, Bondon-Guitton E, et al. A comparative study of QT prolongation with serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2017;234:3075–81. doi: 10.1007/s00213-017-4685-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spindelegger CJ, Papageorgiou K, Grohmann R, et al. Cardiovascular adverse reactions during antidepressant treatment: a drug surveillance report of German-speaking countries between 1993 and 2010. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2015;18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Stock EM, Zeber JE, McNeal CJ, Banchs JE, Copeland LA. Psychotropic Pharmacotherapy Associated With QT Prolongation Among Veterans With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Ann Pharmacother. 2018;52:838–48. doi: 10.1177/1060028018769425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sadanaga T, Sadanaga F, Yao H, Fujishima M. Abnormal QT prolongation and psychotropic drug therapy in psychiatric patients: significance of bradycardia-dependent QT prolongation. J Electrocardiol. 2004;37:267–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson MP, Pepper D, Currier GW, Holloman GH, Jr, Feifel D. The psychopharmacology of agitation: consensus statement of the american association for emergency psychiatry project Beta psychopharmacology workgroup. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13:26–34. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;382:951–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Galletly C, Castle D, Dark F, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the management of schizophrenia and related disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50:410–72. doi: 10.1177/0004867416641195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.www.Crediblemeds.org, QTdrugs List,. 2019. (Accessed June 27 2019, at www.Crediblemeds.org,.)

- 50.Hohnloser SH, Klingenheben T, Singh BN. Amiodarone-associated proarrhythmic effects. A review with special reference to torsade de pointes tachycardia. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:529–35. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-7-199410010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li G, Zhang L. The role of mexiletine in the management of long QT syndrome. J Electrocardiol. 2018;51:1061–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2018.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chandrasekhar S, Fradley MG. QT Interval Prolongation Associated With Cytotoxic and Targeted Cancer Therapeutics. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:55. doi: 10.1007/s11864-019-0657-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Etchegoyen CV, Keller GA, Mrad S, Cheng S, Di Girolamo G. Drug-induced QT Interval Prolongation in the Intensive Care Unit. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2017;12:210–22. doi: 10.2174/1574884713666180223123947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Staikou C, Stamelos M, Stavroulakis E. Impact of anaesthetic drugs and adjuvants on ECG markers of torsadogenicity. Br J Anaesth. 2014;112:217–30. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Viitasalo M, Karjalainen J. QT intervals at heart rates from 50 to 120 beats per minute during 24-hour electrocardiographic recordings in 100 healthy men. Effects of atenolol. Circulation. 1992;86:1439–42. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.5.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Luo S, Michler K, Johnston P, Macfarlane PW. A comparison of commonly used QT correction formulae: the effect of heart rate on the QTc of normal ECGs. J Electrocardiol. 2004;37(Suppl):81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2004.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]