A cluster of patients of novel coronavirus pneumonia (NCP) have been identified in Wuhan in December 2019 and soon this virus spread at a tremendous rate which swept through the whole China and more than 93 countries and regions around the world [1, 2]. This emerging, rapidly evolving situation has threatened the health of all mankind and WHO has raised COVID-19 risk to “very high” at global level.

Up to now, 80,859 cases were confirmed, among which 10–15% patients were critically ill and 3100 (3.83%) died in China. The large number of transmission population between Jiangsu and Hubei provinces led to the infinite burden in controlling the COVID-19 epidemic in Jiangsu Province [3, 4]. By 24:00 on March 7, a total of 631 confirmed cases of NCP were reported with a portion of critically ill patients whose ages ranged from 9 months to 96 years old. A total of 610 cases have been discharged from hospital, and the cure rate of confirmed cases in our province has reached 96.67%, which is far exceeding that of national data [5–8]. Since the outcome of NCP patients in Jiangsu was much better than that in Hubei where the mortality of NCP patients was nearly 4.34%, we retrospectively summarized our therapeutic process and figured out that critical care-dominated treatment patterns might be the core in reducing mortality.

Early recognition of high-risk and critically ill patients

Since the severity of disease is closely related to the prognosis, the basic and essential strategies to improve outcomes that we should adhere to remain the early detection of high-risk and critically ill patients [9, 10]. During the clinical work in Jiangsu Province, critical care was shifted forward and early screening was measured. All NCP patients were screened twice every day and respiratory rate (RR), heart rate (HR), SpO2 (room air) were monitored regularly. Once SpO2 < 93%, RR > 30/min, HR > 120/min or any signs of organ failure were observed, patients would be transferred to intensive care unit (ICU) and ICU physicians and nurses would take over their treatment.

From our data of more than 600 NCP patients in Jiangsu Province, age, lymphocyte count, oxygen supplementation and aggressive pulmonary radiographic infiltrations are independent risk factors for NCP progressing to a critical condition. We established an early warning system combining these four factors to identify high-risk patients and then kept them under continuous close monitoring. The sensitivity of this warning system was 0.955 (95% CI [0.772–0.999]), the specificity was 0.899 (95% CI [0.863–0.928]) and the area under ROC curve was 0.962 (data unpublished). Our retrospective analysis of cases in Jiangsu Province proved a good consistency between early screening of SpO2, RR, HR and early warning model. Therefore, a flowchart integrating early warning model and early screening procedure is recommended for high-risk patients recognition and all patients’ screening to make it possible for early intervention (Fig. 1).

Early intervention guided by intensivists

Fig. 1.

Early warning system and screening procedures for NCP patients

Since there have been no effective antiviral treatments for COVID-19 [7, 8], the vital way to reduce mortality is early and strong intervention to prevent the progression of disease. During the treatment of Jiangsu NCP patients, three points which showed valid evidence in reversing the disease and preventing tracheal intubation rate were summarized.

(1) For patients with ARDS or pulmonary extensive effusion in CT scan, high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy (HFNC) or non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIV) was used to maintain positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) to prevent alveolar collapse even if some of these patients did not have refractory hypoxemia. (2) Restrictive fluid resuscitation under the premise of adequate tissue perfusion is performed to relieve pulmonary edema. (3) Although previous study proved prone position’s benefit in moderate-to-severe ARDS patients with invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) [11], we attempted awake prone position in NCP patients which showed significant effects in improving oxygenation and pulmonary heterogeneity (Fig. 2). With all these measurements, although the rate of critically ill patients in Jiangsu had reached 10%, the IMV rate of Jiangsu was kept under 1%, which was significantly lower than our previous survey about ARDS patients [12].

Clinical experts-guided hierarchical management strategy

Fig. 2.

Early intervention for patients with critical condition

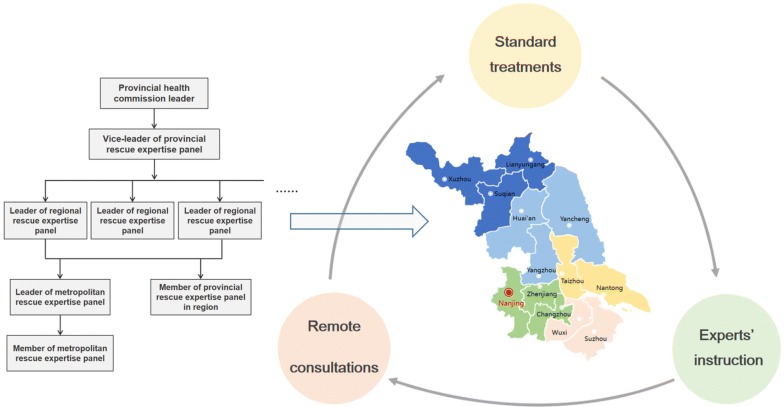

At the outset of epidemic situation, a clinical experts-guided, multidisciplinary, province-wide hierarchical management group was established to provide medical guidance for all NCP patients [13]. The members of this panel are mainly critical care specialists and respiratory specialists from tertiary hospitals. Jiangsu Province is divided into five regions according to geographical position and each leader takes responsibilities for a specific region so that problems can be solved layer-by-layer. This kind of regional responsibility, timely feedback communication management makes it possible for effective medical interventions (Fig. 3).

Rational allocation of materials and human resources

Fig. 3.

Organization chart of hierarchical management strategy

Health authorities attached great importance to epidemic and deployed disease prevention and control measures effectively [14, 15]. All kinds of resources, including frontline medical staff and medical protective materials, were mobilized and deployed uniformly to guarantee patients’ medical care. 234 clinical staff invested in NCP patients’ treatment and care, and 3500 clinical staff were reserved for unexpected needs. Adequate material and human resources are important cornerstones for controlling this epidemic.

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, Jiangsu takes effective measures to curb the spread of the virus and gives normative treatments for infected patients, which shows significant disease control and treatment effects. From our experience, early screening of critically ill patients and critical care-guided early intervention are prominent in reducing NCP patients’ mortality. At this critical moment in the global outbreak of NCP, we hope our valid management and treatment bundles can help us achieve the victory in the battle against COVID-19.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

YY and MH, the corresponding authors, were responsible for the concept, revision and approval of this manuscript. QS participated in the design and drafted the manuscript. HBQ helped to revise the manuscript. All authors contributed to the data analysis and interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported, in part, by the research Grant 2020YFC0843700 from Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China and Treatment procedures and Protocol establishing for critically ill patients (2020YFC0843700).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors have confirmed the manuscript and approved the publication of the manuscript. The corresponding author has completed the “Consent for publication”.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing of interest nor any financial interest in any product mentioned in this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Qin Sun, Email: sunqin1990seu@126.com.

Haibo Qiu, Email: haiboq2000@163.com.

Mao Huang, Email: huangmao6114@126.com.

Yi Yang, Email: yiyiyang2004@163.com.

References

- 1.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlos WG, Dela Cruz CS, Cao B, et al. Novel Wuhan (2019-nCoV) coronavirus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(4):P7–P8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2014P7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu JT, Leung K, Leung GM. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):689–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson R. Pandemic potential of 2019-nCoV. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(3):280. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30068-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang FS, Zhang C. What to do next to control the 2019-nCoV epidemic? Lancet. 2020;395(10222):391–393. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30300-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kock RA, Karesh WB, Veas F, et al. 2019-nCoV in context: lessons learned? Lancet Planet Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30035-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richardson P, Griffin I, Tucker C, et al. Baricitinib as potential treatment for 2019-nCoV acute respiratory disease. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):e30–e31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30304-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russell CD, Millar JE, Baillie JK. Clinical evidence does not support corticosteroid treatment for 2019-nCoV lung injury. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):473–475. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30317-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guérin C, Reignier J, Richard JC, et al. Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(23):2159–2168. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu L, Yang Y, Gao Z, et al. Practice of diagnosis and management of acute respiratory distress syndrome in mainland China: a cross-sectional study. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(9):5394–5404. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.08.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arabi YM, Fowler R, Hayden FG. Critical care management of adults with community-acquired severe respiratory viral infection. Intensive Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05943-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie J, Tong Z, Guan X, et al. Critical care crisis and some recommendations during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Intensive Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05979-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang S, Diao MY, Duan L, et al. The novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) infections in China: prevention, control and challenges. Intensive Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05977-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.