Key Points

Question

What is the association of initial certification by the American Board of Surgery and examination performance with future risk of severe disciplinary actions against medical licenses?

Findings

In this study of 44 290 surgeons, board certification and examination performance were associated with lower rates of severe disciplinary actions against medical licenses.

Meaning

This study provides evidence that supports board certification as a marker of surgeon quality and professionalism.

Abstract

Importance

Board certification is used as a marker of surgeon quality and professionalism. Although some research has linked certification in surgery to outcomes, more research is needed.

Objective

To measure associations between surgeons obtaining American Board of Surgery (ABS) certification and examination performance with receiving future severe disciplinary actions against their medical licenses.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective analysis of severe license action rates for surgeons who attempted ABS certification based on certification status and examination performance. Surgeons who attempted to become certified were classified as certified or failing to obtain certification. Additionally, groups were further categorized based on whether the surgeon had to repeat examinations and whether they ultimately passed. The study included surgeons who initially attempted certification between 1976 and 2017 (n = 44 290). Severe license actions from 1976 to 2018 were obtained from the Federation of State Medical Boards, and certification data were obtained from the ABS database. Data were analyzed between 1978 and 2008.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Severe license action rates were analyzed across certified surgeons and those failing to obtain certification, as well as across examination performance groups.

Results

The final dataset included 36 197 men (81.7%) and 8093 women (18.3%). The incidence of severe license actions was significantly greater for surgeons who attempted and failed to obtain certification (incidence rate per 1000 person-years = 2.49; 95% CI, 2.13-2.85) than surgeons who were certified (incidence rate per 1000 person years = 0.77; 95% CI, 0.71-0.83). Adjusting for sex and international medical graduate status, the risk of receiving a severe license action across time was also significantly greater for surgeons who failed to obtain certification. Surgeons who progressed further in the certification examination sequence and had fewer repeated examinations had a lower incidence and less risk over time of receiving severe license actions.

Conclusions and Relevance

Obtaining board certification was associated with a lower rate of receiving severe license actions from a state medical board. Passing examinations in the certification examination process on the first attempt was also associated with lower severe license action rates. This study provides supporting evidence that board certification is 1 marker of surgeon quality and professionalism.

This study evaluates the association between surgeons obtaining American Board of Surgery certification and examination performance with receiving future severe disciplinary actions against their medical licenses.

Introduction

Board certification by the American Board of Surgery (ABS) is a voluntary process that is intended to be a marker of a surgeon’s commitment to professionalism, lifelong learning, and quality patient care.1 Certificates in surgery are awarded by the ABS based on meeting educational prerequisites and passing both a written qualifying examination (QE) and oral certifying examination (CE). Board certification has been associated with positive physician and patient outcomes in other medical specialties.2,3 Additionally, ABS certification has been associated with reduced patient mortality and morbidity following segmental colon resection.4,5

To further demonstrate the value of ABS certification, additional research is needed investigating the association between general surgery certification and surgeon outcomes. Research has specifically examined the association between board certification and disciplinary actions taken against state medical licenses. Although physicians can be disciplined for a variety of reasons, many severe disciplinary actions by state medical boards (ie, those resulting in a loss of a medical license by revocation, suspension, denial, or surrender) are the result of physician quality issues or unprofessional conduct.6,7 Therefore, disciplinary actions may be considered, in part, an indicator of a surgeon’s practice quality and/or commitment to professionalism. Previous studies have established a strong association between obtaining or maintaining board certification with a lower likelihood of disciplinary actions in multiple medical specialties.6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 Higher performance on the US Medical Licensing Examination Step 2 Clinical Knowledge examination has also been found to relate to a lower likelihood of later disciplinary actions.14 Although maintaining continuous certification and recertification examination performance in surgery have both been associated with a decreased risk of discipline by state medical boards,7,10 to our knowledge, no previous study has examined the association between initial surgery certification and later disciplinary actions. Thus, this study examines the association between ABS initial certification and severe disciplinary actions taken by state medical boards against surgeon licenses (referred to as severe license actions hereafter) to provide additional evidence of board certification as a marker of surgeon quality and professionalism.

We hypothesized that surgeons who achieved certification would be less likely to receive severe license actions than surgeons who attempted but failed to achieve certification. Moreover, severe license action rates were expected to be lower for surgeons who progressed further in the certification process, with the highest severe license action rates for surgeons who never passed the QE and the lowest for surgeons who passed both the QE and CE on their first attempt.

Methods

Surgeon Sample

Certification and demographic data were collected from the ABS database for all surgeons initially attempting the surgery QE from 1976 to 2017. The QE is a multiple-choice examination designed to assess surgical knowledge. Passing the QE allows a surgeon to attempt the CE, an oral examination designed to assess a surgeon’s clinical skills in evaluating and managing common surgical issues.

The ABS surgeon records were joined with disciplinary data obtained from the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) for actions taken by state medical boards from 1976 to 2018. Years of exposure were calculated by subtracting the year of the surgeon’s initial QE attempt from the year of the surgeon’s first severe license action or subtracted from 2018 for surgeons who never received a severe license action. Thus, every surgeon included in the study had at least 1 year of exposure for the potential of receiving a severe license action (ie, no surgeons who first attempted the QE in 2018 or later were included). Surgeon records were removed from the sample if the ABS record could not be joined to FSMB records. Surgeon candidates consented to their ABS data being used for research purposes as part of the examination registration process, and disciplinary action information is publicly available through state medical boards. All individual data were kept in strict confidentiality and deidentified for analysis. This research was determined to be exempt from review by the Pearl institutional review board as secondary research.

Outcome Measures

The data provided by the FSMB included the actions taken, the category of those actions, and information about the reason for the disciplinary action. Following previous research, a board action was coded as a severe license action if it resulted in the license being revoked, suspended, denied, or surrendered.6 Severe license actions were the only outcome measure used in this study, while less severe disciplinary actions (eg, administrative, continuing medical education requirements, conditions, fines, probations, and reprimands) were excluded from the data. Reasons leading to the severe license actions were further classified into the following groups based on previously established classifications: criminal activity, failure to supervise, fraud, impairment, inappropriate prescribing, license or board violations, other inappropriate activity, quality issues, records violation, substance use, unprofessional conduct, and unknown.7,9,10

Primary Analysis

Severe license action incidence rates were compared between surgeons who obtained certification and those who failed to obtain certification after at least 1 QE attempt. To evaluate the association of the various examination steps leading to certification and severe license actions, these 2 groups of surgeons were categorized further into 6 subgroups based on their pass/fail status on the QE and CE, as well as whether they repeated the QE and/or CE, as follows based on previous research9:

Passed the QE and CE on the first attempt

Passed the QE and CE, and repeated the CE only

Passed the QE and CE, and repeated the QE only

Passed the QE and CE, and repeated both examinations

Passed the QE only

Attempted the QE, but never passed

Groups 1-4 obtained certification, whereas groups 5 and 6 did not. Additionally, individuals in group 5 may or may not have attempted the CE. χ2 Analyses were used to compare the certification and examination performance groups on the proportion of women vs men and international medical graduate (IMG, or those completing medical school internationally) vs US and Canadian medical graduate surgeons, respectively. Severe license action incidence rates were calculated using 1000 person-years at risk to control for exposure. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to compare the certification and examination performance groups while accounting for exposure, as well as controlling for sex and whether the surgeon was an IMG. Only the first severe license action received by a surgeon was considered for these analyses. We used R statistical software, version 3.5.3, including the survival (version 2.43.3) and survminer (version 0.4.3) packages (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). All significance tests were set to a 2-sided α level of .05.

Results

A total of 44 290 surgeons met the inclusion criteria for the study. Of the 45 045 surgeons who attempted their first QE between 1976 and 2017, 755 could not be joined to a record in FSMB’s database (98.3% join rate). These unjoined records were primarily from the noncertified group (n = 725). Surgeons from the unjoined group were more likely to be male (641 of 755 [85%] vs 36 197 of 44 290 [82%]; P = .03), IMGs (426 of 755 [56%] vs 7526 of 44 290 [17%]; P < .001), and more specifically non–US-born IMGs (384 of 755 [51%] vs 6251 of 44 290 [14%]; P < .001) compared with surgeons included in the study. These surgeon records may have gone unjoined for a variety of reasons, including that they may no longer be practicing medicine, no longer practicing in the United States, or deceased. Among the 44 290 joined, a small number of surgeons received a severe license action (847; 1.9%). Reasons for severe license actions were categorized as not provided or unknown (n = 198 [23%]), license/board violations (n = 195 [23%]), quality issues (n = 119 [14%]), criminal activity (n = 66 [8%]), unprofessional conduct (n = 58 [7%]), substance abuse (n = 57 [7%]), and fraud (n = 54 [6%]), with other reasons (n = 100 [12%]) comprising the remaining reasons for severe license actions.

Surgeons who failed to obtain certification had a higher incidence rate of future severe license action (incidence rate per 1000 person-years, 2.49; 95% CI, 2.13-2.85) than surgeons who obtained certification (incidence rate per 1000 person-years, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.71-0.83; Table 1). Surgeons who failed to obtain certification were also more likely to be male (2723 of 3216 [84.7%] vs 33 474 of 41 074 [81.5%]) and IMGs (1101 of 3216 [34.2%] vs 6425 of 41 065 [15.6%]; P < .001). Nine surgeons were missing data for IMG status. Further differences were found by splitting the certification groups by examination performance: surgeons who passed both the QE and CE on the first attempt (group 1) had the lowest incidence of future severe license actions (incidence rate per 1000 person-years, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.57-0.69), and incidence rates incrementally increased by group number, such that surgeons who attempted the QE but never passed (group 6) had the highest incidence (incidence rate per 1000 person-years, 2.73; 95% CI, 2.25-3.21).

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics and Severe License Action Incidence Rates of the Surgeon Certification and Examination Performance Groups (N = 44 290)a.

| Characteristics | No. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obtained Certification (n = 41 009 [92.6])c | Failed to Obtain Certification (n = 3281 [7.4])b | |||||

| Group 1: Passed QE and CE First Attempt (n = 30 518 [68.9]) | Group 2: Repeated CE Only (n = 5596 [12.6]) | Group 3: Repeated QE Only (n = 3291 [7.4]) | Group 4: Repeated QE and CE (n = 1604 [3.6]) | Group 5: Passed QE Only (n = 1529 [3.5]) | Group 6: Never Passed QE (n = 1752 [4.0]) | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 24 818 (81.3) | 4696 (83.9) | 2580 (78.4) | 1345 (83.9) | 1239 (81.0) | 1519 (86.7) |

| Female | 5700 (18.7) | 900 (16.1) | 711 (21.6) | 259 (16.1) | 290 (19.0) | 233 (13.3) |

| Medical school | ||||||

| USMG | 26 364 (86.4) | 4505 (80.5) | 2597 (78.9) | 1128 (70.3) | 1141 (74.6) | 1029 (58.7) |

| IMG | 4154 (13.6) | 1091 (19.5) | 694 (21.1) | 476 (29.7) | 388 (25.4) | 723 (41.3) |

| Person-years at risk | 633 508 | 122 591 | 71 101 | 38 046 | 27 782 | 45 786 |

| Severe license action incidents, No. | 397 | 109 | 99 | 59 | 58 | 125 |

| Examination performance group, incidence per 1000 person-years (95% CI) | 0.63 (0.57-0.69) | 0.89 (0.72-1.06) | 1.39 (1.12-1.67) | 1.55 (1.16-1.95) | 2.09 (1.55-2.62) | 2.73 (2.25-3.21) |

| Certification group, incidence per 1000 person-years (95% CI) | 0.77 (0.71-0.83) | 2.49 (2.13-2.85) | ||||

Abbreviations: CE, certifying examination; QE, qualifying examination.

P < .01 for all comparisons based on χ2 analysis.

Only those who attempted the qualifying examination were included in the failed to obtain certification group.

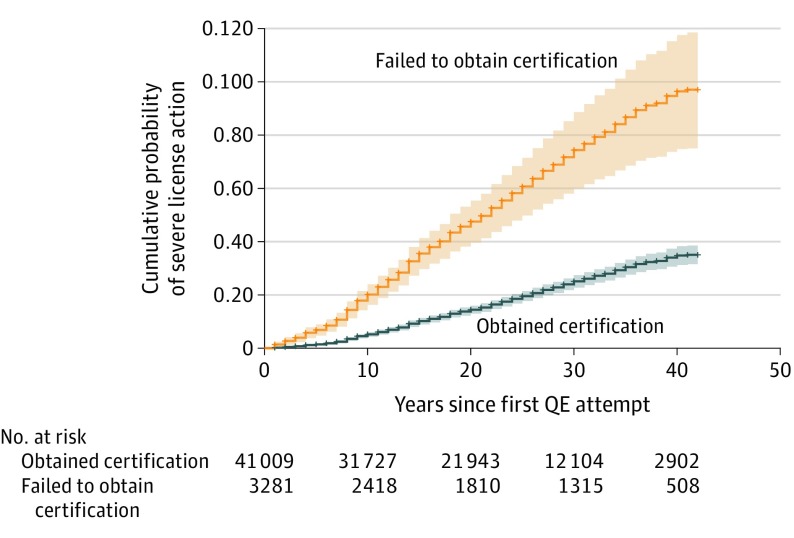

Initial tests of weighted residuals indicated that the association of certification status, examination group, and IMG status with severe license action rates were partially time dependent, violating the proportional hazards assumption of the Cox model.15 Therefore, the interaction between these variables and years of exposure was also included in the model, which resulted in the proportional hazards assumption being met in the revised model.16 After controlling for sex, IMG status, and exposure, surgeons who failed to obtain certification had a higher risk of receiving a severe license action (Table 2). The interaction between certification status and years of exposure indicated the hazard ratio (HR) between certification statuses decreased with increasing years following the first QE attempt (adjusted HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.61-0.96). Hazard ratios at 10 years following surgeons’ first QE attempt were calculated, given surgeons were reassessed every 10 years under the previous ABS maintenance of certification model.10 Thus, assessing severe license action risk within the first 10 years of practice may be most relevant for assessing the validity of the initial certification process, whereas longer lengths of time may be more relevant for validating the maintenance of certification program. Within the first 10 years of their first QE attempt, surgeons who failed to obtain certification had more than 3 times the hazard rate of receiving a severe license action (adjusted HR at 10 years, 3.38; 95% CI, 2.79-4.10) compared with certified surgeons. The adjusted cumulative incidence plot for severe license actions by certification status is displayed in Figure 1. Although the interaction between certification status and time resulted in a smaller HR with increasing years following the first QE attempt (adjusted HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.61-0.96), there were still clear differences between the certification groups at all years of exposure. For example, for the HRs at 40 years following the first QE attempt, surgeons who failed to obtain certification were still significantly more likely to receive a severe license action after controlling for covariates (adjusted HR at 40 years, 2.34; 95% CI, 1.76-3.11). To further evaluate the association between certification status and severe license actions in recent years, we reestimated the Cox model and HRs at 10 years of exposure for only those surgeons first attempting the QE between 1998 and 2008. Narrowing the analysis to this time resulted in a wider confidence interval and a reduced but still significant HR compared with the full data set (adjusted HR at 10 years, 2.37; 95% CI, 1.34-4.20).

Table 2. Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Predicting Risk of Receiving a Severe License Action From Certification Status (N = 44 290).

| Variable | Hazard Ratio (95% CI)a | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Certification status | ||

| Obtained certification | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Failed to obtain certification | 3.38 (2.79-4.10) | <.001 |

| Failed to obtain certification × ln(time) | 0.77 (0.61-0.96) | .02 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Female | 0.63 (0.48-0.83) | <.001 |

| IMG status | ||

| USMG | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| IMG | 0.91 (0.74-1.13) | .40 |

| IMG × ln(time) | 1.45 (1.12-1.87) | .005 |

Abbreviations: IMG, international medical graduate; ln(time), natural logarithm of time of exposure, in years; NA, not applicable; USCMG, US and Canadian medical graduate.

Hazard ratios at 10 years of exposure (ie, 10 years after attempting the first qualifying examination) are displayed.

Figure 1. Adjusted Cumulative Incidence Plot of Severe License Action Incidence Over Time by Certification Status.

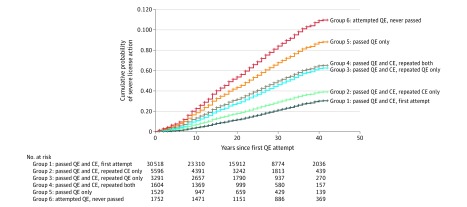

After controlling for sex, IMG status, and exposure, all other examination performance groups (ie, groups 2-6) had a higher risk of receiving a severe license action than surgeons who passed the QE and CE on the first attempt (Table 3), although not all of these groups were significantly different from each other. Interaction effects indicated the differences in risk between groups became slightly smaller with increasing years following the first QE attempt (Table 3). Compared with surgeons who passed both QE and CE on the first attempt, surgeons who repeated the CE only before becoming certified were the next least likely to receive a severe license action within 10 years of their first QE attempt (group 2, adjusted HR at 10 years, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.24-2.00), followed by surgeons who repeated the QE only before becoming certified (group 3, adjusted HR at 10 years, 2.46; 95% CI, 1.91-3.16), surgeons who repeated both the QE and CE (group 4, adjusted HR at 10 years, 2.81; 95% CI, 2.07-3.83), then surgeons who passed the QE only (group 5, adjusted HR at 10 years, 3.88; 95% CI, 2.87-5.24), and finally, surgeons who never passed the QE (group 6, adjusted HR at 10 years, 4.81; 95% CI, 3.76-6.17). The adjusted cumulative incidence plot for receiving a severe license action by the 6 examination performance groups is displayed in Figure 2. When evaluating the HRs at 40 years after the first QE attempt, all HRs comparing groups 3 through 6 with group 1 remained significant, with only surgeons who repeated the CE only (group 2) having a statistically nonsignificant HR (adjusted HR at 40 years, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.72-1.52). Moreover, surgeons who failed to pass the QE (group 6) continued to have the highest HR at 40 years after the first QE attempt compared with surgeons who passed the QE and CE on the first attempt (group 1) (adjusted HR at 40 years, 2.86; 95% CI, 2.01-4.07).

Table 3. Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Predicting Risk of Receiving a Severe License Action From Examination Performance (N = 44 290).

| Variable | Hazard Ratio (95% CI)a | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Certification status | ||

| Group 1: Passed QE and CE, 1st attempt | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Group 2: Passed QE and CE, repeated CE only | 1.57 (1.24-2.00) | <.001 |

| Group 3: Passed QE and CE, repeated QE only | 2.46 (1.91-3.16) | <.001 |

| Group 4: Passed QE and CE, repeated both | 2.81 (2.07-3.83) | <.001 |

| Group 5: Passed QE only | 3.88 (2.87-5.24) | <.001 |

| Group 6: Attempted QE, never passed | 4.81 (3.76-6.17) | <.001 |

| Group 2 × ln(time) | 0.74 (0.55-1.01) | .05 |

| Group 3 × ln(time) | 0.79 (0.58-1.09) | .15 |

| Group 4 × ln(time) | 0.68 (0.46-0.99) | .04 |

| Group 5 × ln(time) | 0.67 (0.47-0.96) | .03 |

| Group 6 × ln(time) | 0.69 (0.51-0.92) | .01 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Female | 0.61 (0.47-0.80) | <.001 |

| IMG status | ||

| USMG | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| IMG | 0.82 (0.66-1.01) | .06 |

| IMG × ln(time) | 1.46 (1.13-1.90) | .004 |

Abbreviations: CE, certifying examination; IMG, international medical graduate; ln(time), natural logarithm of time of exposure, in years; QE, qualifying examination; USCMG, US and Canadian medical graduate.

Hazard ratios at 10 years of exposure (ie, 10 years after attempting the first qualifying examination) are displayed.

Figure 2. Adjusted Cumulative Incidence Plot of Severe License Action Incidence Over Time by Examination Performance.

Discussion

This study shows that surgeons who attempted and failed to become certified by the ABS were significantly more likely to receive a severe disciplinary action against their medical license than surgeons who successfully obtained certification. Increased incidence rates of severe license actions were also associated with having to repeat examinations to achieve certification, as well as being unable to pass the QE or the CE. These associations remained significant after controlling for sex, IMG status, and exposure. Interaction effects with time of exposure indicated that these effects were slightly diminished with more years of surgical practice. The effect sizes in this study were relatively large, with noncertified surgeons having more than 3 times the adjusted hazard of receiving a severe license action than certified surgeons 10 years after their first QE attempt.

This study also provides evidence that each component of the ABS certification process has utility. Repeating either the QE or the CE was associated with an increased risk of receiving a severe license action. Moreover, surgeons who passed only the QE were associated with more than 3 times the HR of receiving a severe license action 10 years after their first QE attempt compared with surgeons who passed both the QE and CE on their first attempt. The ABS has a multistep process to achieve certification, and this study demonstrates that there is value in having each of these distinct assessments as components of the certification process.

This study builds on past research linking maintenance of surgery certification with a lower likelihood of receiving disciplinary actions from state medical boards,7,10 as well as linking initial certification in other medical specialties to a reduced likelihood of receiving disciplinary actions.6,8,9,11 As with this previous research,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 this study cannot establish a causal link between certification and reduced rates of severe license actions. Additionally, given that the basis for severe license actions is a mix of quality issues, board violations, criminal activity, and other issues, severe license actions is a limited indicator of surgeon quality. However, the association of ABS certification and examination performance with later severe license actions provides additional evidence that ABS certification is a valid marker of professionalism and quality patient care. Surgeon quality issues composed a sizable portion of basis categories for severe license actions. Other reasons for severe license actions are indicative of a lack of professionalism, such as substance use and violating a state’s medical practice laws by engaging in criminal activity. Although no causal link is established with this study, an association between certification status and receiving a severe license action from a state medical board provides evidence for the utility of the ABS certification process.

Limitations

Some limitations to our study should be noted. First, we only examined surgeons who had at least 1 attempt to pass the QE. Although the most surgeons who complete accredited surgical training attempt the QE, some practicing surgeons may not attempt certification after completing training or may have pursued a training pathway outside of the scope of the ABS. For example, the American Osteopathic Board of Surgery offers a separate pathway to their own certification, and those surgeons were not included in our sample. Previous research has found that osteopathic physicians have higher rates of disciplinary actions,17 but it is unclear whether the magnitude of this effect is similar to that of attempting and failing to obtain ABS certification. Additionally, surgeons who completed their surgical residency internationally were not eligible for ABS certification and thus did not complete the qualifying examination. As noted previously, this study also had a small but disproportionate degree of unjoined data for noncertified surgeons. Certain control variables were not examined in this study, such as subspecialty area or different jurisdictions the surgeon practices in. Finally, surgeons are disciplined by state medical boards for a variety of reasons, many of which are unknown. Previous research has found a large amount of variation in disciplinary action rates across states,18 suggesting that medical board severity could be a confounding factor. Thus, it is unclear whether severe license actions are a result of deficient surgeon quality, lack of professionalism, variation across states, or some other reason.

Conclusions

Future studies may expand on this research in a number of ways. We encourage other medical specialties to also investigate the association between board certification and disciplinary actions. Identifying surgeons who never attempted certification may provide further insight into the association between ABS certification and disciplinary actions. Further research is needed to relate board certification to surgeon and patient outcomes. Future work could examine malpractice claims against board-certified and noncertified surgeons. Studies directly relating certification to patient outcomes on common surgical procedures would be similarly useful. More work in this area may provide additional evidence that board certification is a meaningful indicator of professionalism, lifelong learning, and quality patient care, metrics that are particularly important for patients to consider when choosing a surgeon.

References

- 1.American Board of Surgery . About ABS certification. Accessed December 5, 2019. http://www.absurgery.org/default.jsp?publiccertprocess

- 2.Lipner RS, Hess BJ, Phillips RL Jr. Specialty board certification in the United States: issues and evidence. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2013;33(S1)(suppl 1):S20-S35. doi: 10.1002/chp.21203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reid RO, Friedberg MW, Adams JL, McGlynn EA, Mehrotra A. Associations between physician characteristics and quality of care. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(16):1442-1449. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharp LK, Bashook PG, Lipsky MS, Horowitz SD, Miller SH. Specialty board certification and clinical outcomes: the missing link. Acad Med. 2002;77(6):534-542. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200206000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prystowsky JB, Bordage G, Feinglass JM. Patient outcomes for segmental colon resection according to surgeon’s training, certification, and experience. Surgery. 2002;132(4):663-670. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.127550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lipner RS, Young A, Chaudhry HJ, Duhigg LM, Papadakis MA. Specialty certification status, performance ratings, and disciplinary actions in internal medicine residents. Acad Med. 2016;91(3):376-381. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones AT, Kopp JP, Malangoni MA. Recertification exam performance in general surgery is associated with subsequent loss of license actions. Ann Surg. Published online April 23, 2019. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papadakis MA, Arnold GK, Blank LL, Holmboe ES, Lipner RS. Performance during internal medicine residency training and subsequent disciplinary action by state licensing boards. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(11):869-876. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-11-200806030-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou Y, Sun H, Culley DJ, Young A, Harman AE, Warner DO. Effectiveness of written and oral specialty certification examinations to predict actions against the medical licenses of anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2017;126(6):1171-1179. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones AT, Kopp JP, Malangoni MA. Association between maintaining certification in general surgery and loss-of-license actions. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1195-1196. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.9550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peabody MR, Young A, Peterson LE, et al. The relationship between board certification and disciplinary actions against board-eligible family physicians. Acad Med. 2019;94(6):847-852. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDonald FS, Duhigg LM, Arnold GK, Hafer RM, Lipner RS. The American Board of Internal Medicine Maintenance of Certification Examination and state medical board disciplinary actions: a population cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(8):1292-1298. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4376-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou Y, Sun H, Macario A, et al. Association between performance in a maintenance of certification program and disciplinary actions against the medical licenses of anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2018;129(4):812-820. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cuddy MM, Young A, Gelman A, et al. Exploring the relationships between USMLE performance and disciplinary action in practice: a validity study of score inferences from a licensure examination. Acad Med. 2017;92(12):1780-1785. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81(3):515-526. doi: 10.1093/biomet/81.3.515 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marinussen T, Scheike T. Dynamic Regression Models for Survival Data. Springer-Verlag; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cardarelli R, Licciardone JC, Ramirez G. Predicting risk for disciplinary action by a state medical board. Tex Med. 2004;100(1):84-90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris JA, Byhoff E. Variations by state in physician disciplinary actions by US medical licensure boards. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26(3):200-208. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]