Background: Little is known about the effectiveness of personal protective equipment for health care workers who take care of patients infected with the novel coronavirus (SARS–CoV-2) that recently originated in China and has spread globally (1, 2).

Objective: To describe the clinical outcome of health care workers who took care of a patient with severe pneumonia before the diagnosis of COVID-19 was known.

Case Report: The patient was a middle-aged man with diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidemia who was hospitalized in February 2020 for community-acquired pneumonia. He had not traveled recently to China nor had had contact with anyone known to have COVID-19. He required supplemental oxygen on admission; the following day, he developed respiratory distress that required endotracheal intubation by the emergency airway team and mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit (ICU). He was transferred to the ICU for intubation and had a difficult intubation that required use of a video laryngoscope and an airway bougie. He improved clinically after 3 days of mechanical ventilation and was subsequently extubated to noninvasive ventilation.

On the day that the patient was extubated, a nasopharyngeal swab was sent as part of COVID-19 surveillance, and it was positive for SARS–CoV-2 on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay (3). Two other swabs obtained on subsequent days tested positive for SARS–CoV-2.

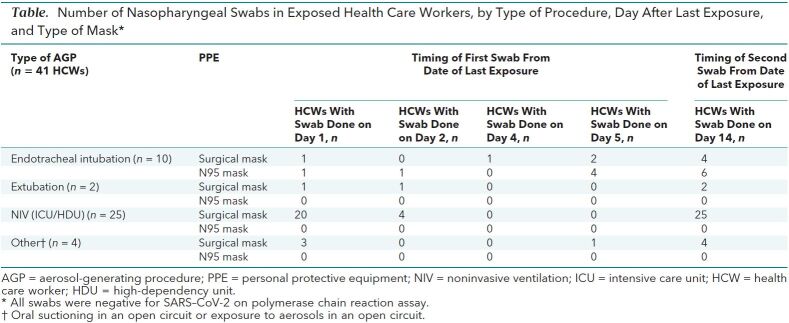

On the basis of contact tracing, 41 health care workers were identified as having exposure to aerosol-generating procedures for at least 10 minutes at a distance of less than 2 meters from the patient. The aerosol-generating procedures included endotracheal intubation, extubation, noninvasive ventilation, and exposure to aerosols in an open circuit (4). All 41 health care workers were placed under home isolation for 2 weeks, with daily monitoring for cough, dyspnea, and myalgia and twice-daily temperature measurements. In addition, they had nasopharyngeal swabs scheduled on the first day of home isolation, which could have been day 1, 2, 4, or 5 after last exposure to patient, and a second swab scheduled on day 14 after their last exposure. The swabs were tested for SARS–CoV-2 by using a PCR assay. None of the exposed health care workers developed symptoms, and all PCR tests were negative (Table).

Table. Number of Nasopharyngeal Swabs in Exposed Health Care Workers, by Type of Procedure, Day After Last Exposure, and Type of Mask*.

Discussion: The primary route for the spread of COVID-19 is thought to be through aerosolized droplets that are expelled during coughing, sneezing, or breathing, but there also are concerns about possible airborne transmission. In the situation we describe, 85% of health care workers were exposed during an aerosol-generating procedure exposed while wearing a surgical mask, and the remainder were wearing N95 masks. That none of the health care workers in this situation acquired infection suggests that surgical masks, hand hygiene, and other standard procedures protected them from being infected. Our observation is consistent with previous studies that have been unable to show that N95 masks were superior to surgical masks for preventing influenza infection in health care workers (5). We emphasize, however, that nearly all experts recommend that health care workers wear an N95 mask or equivalent equipment while performing an aerosol-generating procedure.

We recognize the limitations of this single case report and acknowledge that additional studies are necessary to determine how best to protect health care workers from becoming infected with SARS-CoV while they are providing care for patients with COVID-19.

Biography

Disclosures: Authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest. Forms can be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=L20-0175.

Footnotes

This article was published at Annals.org on 16 March 2020.

References

- 1. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020. [PMID: 32031570] doi:10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001621. Pongpirul WA, Pongpirul K, Ratnarathon AC, et al. Journey of a Thai taxi driver and novel coronavirus [Letter]. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1067-1068. [PMID: 32050060] doi:10.1056/NEJMc2001621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3. Ministry of Health Singapore. Ministerial statement on whole-of-government response to the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-NCOV). 3 February 2020. Accessed at www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/ministerial-statement-on-whole-of-government-response-to-the-2019-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov. ) on 18 February 2020.

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim U.S. guidance for risk assessment and public health management of health care personnel with potential exposure in a health care setting to patients with 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). 22 February 2020. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html. on 22 February 22, 2020.

- 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.11645. Radonovich LJ Jr, Simberkoff MS, Bessesen MT, et al; ResPECT investigators. N95 respirators vs medical masks for preventing influenza among health care personnel: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322:824-833. [PMID: 31479137] doi:10.1001/jama.2019.11645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]