Abstract

Objective:

Past studies indicate that >90% of breast cancer survivors taking adjuvant endocrine therapy (AET) experience menopausal symptoms including sexual problems (e.g., vaginal dryness, dyspareunia); however research examining the impact of these problems on quality-of-life is limited. This cross-sectional study examined: 1) the impact of sexual problems and self-efficacy for coping with sexual problems (sexual self-efficacy) on quality-of-life (i.e., psychosocial quality-of-life and sexual satisfaction); and 2) partner status as a moderator of these relationships.

Methods:

Postmenopausal breast cancer survivors taking AET completed measures of sexual problems [Menopause-Specific Quality-of-Life (MENQOL)-sexual subscale], sexual self-efficacy, psychosocial quality-of-life (MENQOL-psychosocial subscale), and sexual satisfaction (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General item).

Results:

Bivariate analyses showed that women reporting greater sexual problems and lower sexual self-efficacy had poorer quality-of-life and less sexual satisfaction (ps<0.05). Partner status moderated the relationship between sexual problems and psychosocial quality-of-life (p=0.02); at high levels of sexual problems, unpartnered women experienced poorer psychosocial quality-of-life than partnered women. Partner status also moderated the relationship between self-efficacy and psychosocial quality-of-life (p=0.01). Self-efficacy was unrelated to psychosocial quality-of-life for partnered women; for unpartnered women, low self-efficacy was associated with poorer quality-of-life. Partner status did not moderate the relationships between sexual problems or self-efficacy with sexual satisfaction.

Conclusions:

Greater sexual problems and lower sexual self-efficacy were associated with poorer psychosocial quality-of-life and sexual satisfaction among postmenopausal breast cancer survivors taking AET. Interventions to address sexual problems and sexual self-efficacy, particularly among unpartnered women, may be beneficial for improving the wellbeing of postmenopausal breast cancer survivors on AET.

Keywords: Breast Cancer Survivors, Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy, Sexual Problems, Self-Efficacy, Quality-of-life, Postmenopausal

Introduction

Breast cancer is the leading cancer diagnosis in women, with 266,120 new cases estimated in 2018.1 More than 70% of these cases occur in women over age 50.2 Adjuvant endocrine therapy (AET; i.e., tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors) is recommended for postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive (HR+) tumors for as long as 10 years following treatment completion to lower estrogen levels and/or block the effects of estrogen on breast cancer cells.3–5 The use of AET among postmenopausal women with HR+ tumors has consistently been associated with clinical benefits, including decreased risk of breast cancer recurrence, contralateral breast cancer, and disease-specific mortality.4, 5 Despite these benefits, rates of adherence to AET are low and decrease over time.6 Systematic reviews have found rates of nonadherence to range from 20% to 59%.7, 8 When compared to breast cancer survivors with high treatment adherence (>80% of expected doses), those with poor adherence have been found to have significantly shorter relapse-free and total survival times as well as increased medical costs and loss of quality-adjusted life years.9–12

Nonadherence and early discontinuation of AET may be due, in part, to women’s experiences of treatment-related side effects.13–17 Breast cancer survivors receiving AET report a variety of side effects, including pain (e.g., arthralgias, myalgias, headaches), vasomotor symptoms (e.g., hotflashes), fatigue, and sleep problems that interfere with daily functioning.13, 18–22 One important, though understudied, side effect of AET is sexual problems. A recent study suggests as many as 93% of breast cancer survivors on AET experience sexual side effects.23 Common sexual side effects include vaginal dryness, dyspareunia (i.e., difficult or painful sexual intercourse), and low sexual desire,23–25 and these side effects often remain stable over time.26–28 Among postmenopausal women in particular, AET can exacerbate menopausal symptoms—including sexual side effects.22 While sexual problems may diminish with the discontinuation of AET,29 national guidelines recommend patients receive 5–10 years of therapy.30 Thus, sexual side effects may be a significant and persistent problem for many patients.

Sexual problems have been associated with poor quality-of-life for women in both the general population31 and across illness populations,32, 33 including breast cancer survivors.18, 34, 35 While research suggests that psychological (e.g., depressive symptoms)34 and social (e.g., relationship distress)46, 36 quality-of-life domains may be impacted by sexual problems, few studies have specifically looked at the relationship between sexual problems and quality-of-life for postmenopausal women receiving AET.37 A recent study of close to 700 postmenopausal breast cancer survivors receiving AET found greater symptom burden, including sexual problems (e.g., decreased libido), to be associated with poorer quality-of-life.38 Sexual problems have also been associated with significant distress for women taking AET.23, 39 After sampling close to 300 breast cancer survivors within the first two years of receiving a prescription for AET, Schover and colleagues found that, among women reporting sexual problems, close to 75% endorsed significant emotional distress related to their sexual problems.23 Additional work is necessary to better understand the impact that AET-related sexual problems may have on quality-of-life for breast cancer survivors. The present study aims to address this gap.

Self-efficacy is an important construct encompassing an individual’s perceived ability to engage in behaviors necessary to produce a specific effect.40, 41 Among breast cancer survivors, self-efficacy for managing specific domains (e.g., physical symptoms, emotional symptoms) has been associated with better quality-of-life.42, 43 However, self-efficacy for managing one domain may not translate to self-efficacy for managing another domain. The impact of self-efficacy for managing sexual problems (sexual self-efficacy) on quality-of-life for breast cancer survivors is currently unknown and may be important for understanding women’s psychosocial and sexual quality-of-life. Women with higher sexual self-efficacy have greater confidence in their ability to cope with AET-related sexual problems, which may reduce the impact of sexual problems on quality-of-life. Self-efficacy is modifiable with intervention;40, 41 thus, improving our understanding of the relationship between sexual self-efficacy and quality-of-life may assist with creating targeted interventions to enable women to better manage sexual problems and maintain higher quality-of-life.

Research has found partnered breast cancer survivors to have better quality-of-life than unpartnered survivors,44 and support from one’s partner may facilitate adjustment to cancer-related sexual problems.45 While research suggests that unpartnered breast cancer survivors are interested in initiating new intimate relationships,46 the presence of sexual problems may result in the avoidance of sexual relationships.47 This is problematic as initiating a new relationship may result in improved quality-of-life. Qualitative research has found dating and starting new intimate relationships to help unpartnered breast cancer survivors restore their sense of self and improve their self-esteem following diagnosis and treatment.48 Taken together, this work suggests unpartnered postmenopausal breast cancer patients may be particularly vulnerable to poor quality-of-life, especially if they experience sexual problems and low self-efficacy for coping with sexual problems. However, at present, the impact of partner status on the relationships between sexual problems or sexual self-efficacy and quality-of-life is unknown.

The present cross-sectional study examined the relationships between sexual problems, sexual self-efficacy, and quality-of-life (i.e., psychosocial quality-of-life and sexual satisfaction) among postmenopausal breast cancer survivors taking AET. Next, we examined partner status as a potential moderator of these relationships. Based on a review of the literature suggesting that partnered women may experience better psychosocial quality-of-life,44, 45 it was hypothesized that being partnered would buffer the impact of sexual problems and sexual self-efficacy on psychosocial quality-of-life and sexual satisfaction.

Methods

Participants

Women were recruited from a comprehensive cancer center located at a major academic medical center in North Carolina. Eligible participants were postmenopausal women diagnosed with stage I to IIIA HR+ breast cancer who had completed local definitive treatment (i.e., surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation) and were currently taking AET. The study was approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board.

One hundred forty-three women were approached; 87% (N=125) agreed to participate and provided informed consent. Of these, 13 were excluded from analyses; one participant had not yet completed surgical treatment, and the remaining 12 did not complete a sufficient number of study measures after consent to conduct analyses. There were no significant differences on demographic or medical variables between women included or excluded in the study (ps≥0.18) with the exception of treatment course; women excluded were more likely to have undergone a mastectomy (75% vs. 45% p=0.05) and less likely to have undergone chemotherapy (17% vs. 53%, p=0.02).42, 49

The sexual satisfaction item was added midway through data collection. Thus, this question was only asked to 79 of the 112 participants. Women asked this item were more likely to be younger, partnered, White, have received chemotherapy, and have less severe medical comorbidities than women who were not asked this item (ps≤0.05).

Procedures

Letters were mailed to prospective participants introducing the study and provided a phone number to obtain further information about the study or opt out of participation. Women who did not decline further contact were approached by a research assistant in clinic on the day of their next scheduled appointment. After completing informed consent, women completed a set of self-report questionnaires. Information pertaining to women’s treatment course and medical comorbidities was abstracted from their medical records. Women received $10 for their participation.

Measures

Demographic and Medical Information.

Women self-reported their age, race, and education. Information about women’s breast cancer treatments (i.e., surgery, radiation, chemotherapy) and records of current and past endocrine therapies were obtained from the medical record. Comorbidities were obtained from medical chart review and evaluated using the Adult Comorbidity Evaluation Scale (ACE-27).50 The ACE-27 grades specific conditions into levels of mild (grade 1), moderate (grade 2), or severe (grade 3), and total comorbidity scores are given based on the highest ranked ailment. An overall score of severe is assigned in the event two or more conditions in different organ systems (e.g., respiratory system) are rated as moderate or at least one condition is rated as severe.

Partner Status.

Women were asked to indicate whether or not they lived with an intimate partner. Women living with an intimate partner were classified as being “partnered.” Women who did not live with an intimate partner were classified as being “unpartnered.”

Sexual Problems.

The sexual subscale of the Menopause-Specific Quality-of-life Questionnaire (MENQOL)51, 52 assessed the impact of participants’ sexual problems (i.e., low sexual desire, vaginal dryness, avoiding intimacy) in the past month. Participants first rated each symptom as being present or absent; items were scored as “2” if the symptom was present and “1” if the symptom was absent. If a symptom was present, participants were then asked how bothered they were by that symptom from 0 “not bothered at all” to 6 “extremely bothered.” The presence and bother scores were then summed, with total scores ranging from 1 “symptom not present” to 8 “extremely bothered” for each symptom. The scores for the three items were then averaged. The MENQOL-sexual has been used previously with breast cancer survivors and has been shown to be reliable and valid.52 Cronbach’s alpha for the present study was 0.83.

Self-Efficacy for Managing Sexual Problems.

A single item assessed women’s sexual self-efficacy. Specifically, women rated their confidence in their ability to cope with sexual problems (e.g., loss of interest, vaginal dryness) on a 10-point scale from 10 “not confident” to 100 “very confident.” This item was worded similarly to items on a standard self-efficacy scale.53

Psychosocial Quality-of-life.

The psychosocial subscale of the MENQOL51 assessed participants’ psychosocial quality-of-life in the past month. The subscale is comprised of seven items that ask participants about mood (e.g., feeling depressed, down or blue), psychological functioning (e.g., poor memory), and relationships with others (e.g., dissatisfaction with my personal life). The method of scoring the presence and bother of the seven items, as well as the overall composite score, was the same as the sexual subscale of the MENQOL. Alpha for the present study is 0.91.

Sexual Satisfaction.

One item from the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy- General (FACT-G)54 assessed women’s satisfaction with their sex lives. Women were asked to rate how satisfied they were with their sex lives, regardless of their current level of sexual activity, from 0 “not at all” to 4 “very much.” This item has been used previously as an assessment of breast cancer survivors’ sexual satisfaction.55

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated. Bivariate analyses examined the relationships between study variables and demographic and disease characteristics. Correlational analyses examined the relationships between study variables. Multiple linear regressions examined sexual problems and sexual self-efficacy as predictors of psychosocial quality-of-life and sexual satisfaction and partner status as a moderator of these relationships. Sociodemographic and medical variables significantly associated with psychosocial quality-of-life and sexual satisfaction were included as covariates. Regression models included: 1) demographic and medical control variables, 2) sexual problems or sexual self-efficacy, 3) partner status, and 4) predictor x moderator interaction term. Variables were mean centered. Simple slopes analyses were conducted to facilitate interpretation of significant interactions.56

Results

Sample Description

Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. Women (N=112) were 63.66 (SD=8.91) on average; the majority were White (81.3%) and cohabiting with an intimate partner (68.8%). Of those cohabiting with an intimate partner, 96.1% were married to their partner. Women were highly educated, with more than half having at least a college degree. Two-thirds were diagnosed with stage II or III breast cancer, and the majority of women received chemotherapy (52.7%) and/or radiation (75%). More than 80% of women were taking an aromatase inhibitor (82.1%), and the remaining women were taking tamoxifen (17.9%). The average time on a woman’s current endocrine therapy regimen was 25.47 months (SD=22.00).

Table 1.

Sociodemographics/Medical Characteristics (N=112)

| % (N) | Mean (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 63.66 (8.91) | 45 to 84 | |

| Race | 81.3% (91) | ||

| % White | |||

| Ethnicity | |||

| % Hispanic | 3.6% (4) | ||

| % Cohabiting with romantic partner | 68.8% (77) | ||

| Educational Attainment | |||

| < High School Degree | 5.4% (6) | ||

| High School Degree | 17.0% (19) | ||

| Some College | 19.6% (22) | ||

| College Degree | 28.6% (32) | ||

| Some graduate training/Graduate Degree | 27.7% (31) | ||

| Stage | |||

| I | 38.4% (43) | ||

| II | 50.0% (56) | ||

| III | 11.6% (13) | ||

| Type of Endocrine Therapy | |||

| Tamoxifen | 17.9% (20) | ||

| Aromatase Inhibitor | 82.1% (92) | ||

| Months on current endocrine therapy regimen | 25.47 (22.00) | ||

| Months on any endocrine therapy | 37.20 (29.47) | 0 to 97.81 | |

| Receipt of Chemotherapy | 52.7% (59) | 1.15 to 130.30 | |

| Taxane-based chemotherapy | 39.3% (44) | ||

| Receipt of Radiation | 75.0% (84) | ||

| Comorbidity Score | |||

| None | 35.7% (40) | ||

| Mild | 43.8% (49) | ||

| Moderate | 14.3% (16) | ||

| Severe | 6.3% (7) | ||

| Satisfaction with Sex Lifea | 1.99 (1.46) | 0 to 4 | |

| Number of Sexual Problems | 1.62 (1.18) | 0 to 3 | |

| Decreased Sexual Desire (% yes) | 57.1% (64) | ||

| Vaginal Dryness (% yes) | 56.3% (63) | ||

| Avoiding Intimacy (% yes) | 40.2% (45) | ||

| Sexual Problems | 3.41 (2.13) | 1 to 8 | |

| Self-efficacy for managing Sexual Problems | 66.76 (29.66) | 10 to 100 | |

| Psychosocial Quality-of-lifeb | 2.77 (1.55) | 1 to 7.14 |

Item added midway through data collection; thus, the total sample size possible for this variable was n=79

Note- Higher scores indicate poorer psychosocial quality-of-life.

Women reported low levels of satisfaction with their sex lives (M=1.99, SD=1.46; possible range: 0–4); close to 40% of those responding to this question reported that they were not at all or only a little bit satisfied while only approximately one-fifth were very satisfied with their sex lives. Close to 70% of women experienced at least one sexual problem, with more than half reporting decreased sexual desire and/or vaginal dryness and more than 40% reporting avoiding intimacy. The mean score on the MENQOL sexual subscale was 3.41 (SD=2.13) indicating that the majority of women experienced sexual bother. Women reported being only somewhat confident in their ability to manage sexual problems (M=66.76, SD=29.66).

Bivariate Analyses

Bivariate analyses examined the relationships between participant sociodemographic and disease characteristics and study variables. When compared to younger women and those receiving chemotherapy, older women (r=0.28, p=0.01) and those who did not receive chemotherapy [F(1, 77)=4.00, p=0.049)] reported greater satisfaction with their sex lives. Among those receiving chemotherapy, women receiving a taxane-based treatment versus other chemotherapy regimen reported significantly lower sexual satisfaction [F(1, 54)=8.56, p=0.005)]. Women living with an intimate partner reported more sexual problems [F(1, 104)=8.69, p=0.004)], and women taking an aromatase inhibitor versus tamoxifen reported significantly lower sexual self-efficacy [F(1, 100)=4.06, p=0.047)]. Finally, women reporting more severe comorbidities had poorer psychosocial quality-of-life (r=0.22, p=0.02). Length of time taking endocrine therapy, time on current endocrine therapy regimen, stage at diagnosis, receipt of radiation therapy, ethnicity, and education were not significantly associated with any of the variables of interest (ps>0.05).

Correlational Analyses

Reports of more sexual problems were associated with lower sexual self-efficacy (r=−0.44, p<0.01), poorer psychosocial quality-of-life (r=0.35, p<0.01), and lower sexual satisfaction ratings (r=−0.55, p<0.01). Greater sexual self-efficacy was associated with greater sexual satisfaction (r=0.35, p<0.01) and better psychosocial quality-of-life (r=−0.42, p<0.01). Lower sexual satisfaction ratings were associated with poorer psychosocial quality-of-life (r=−0.28, p=0.01).

Multiple Regression Analyses

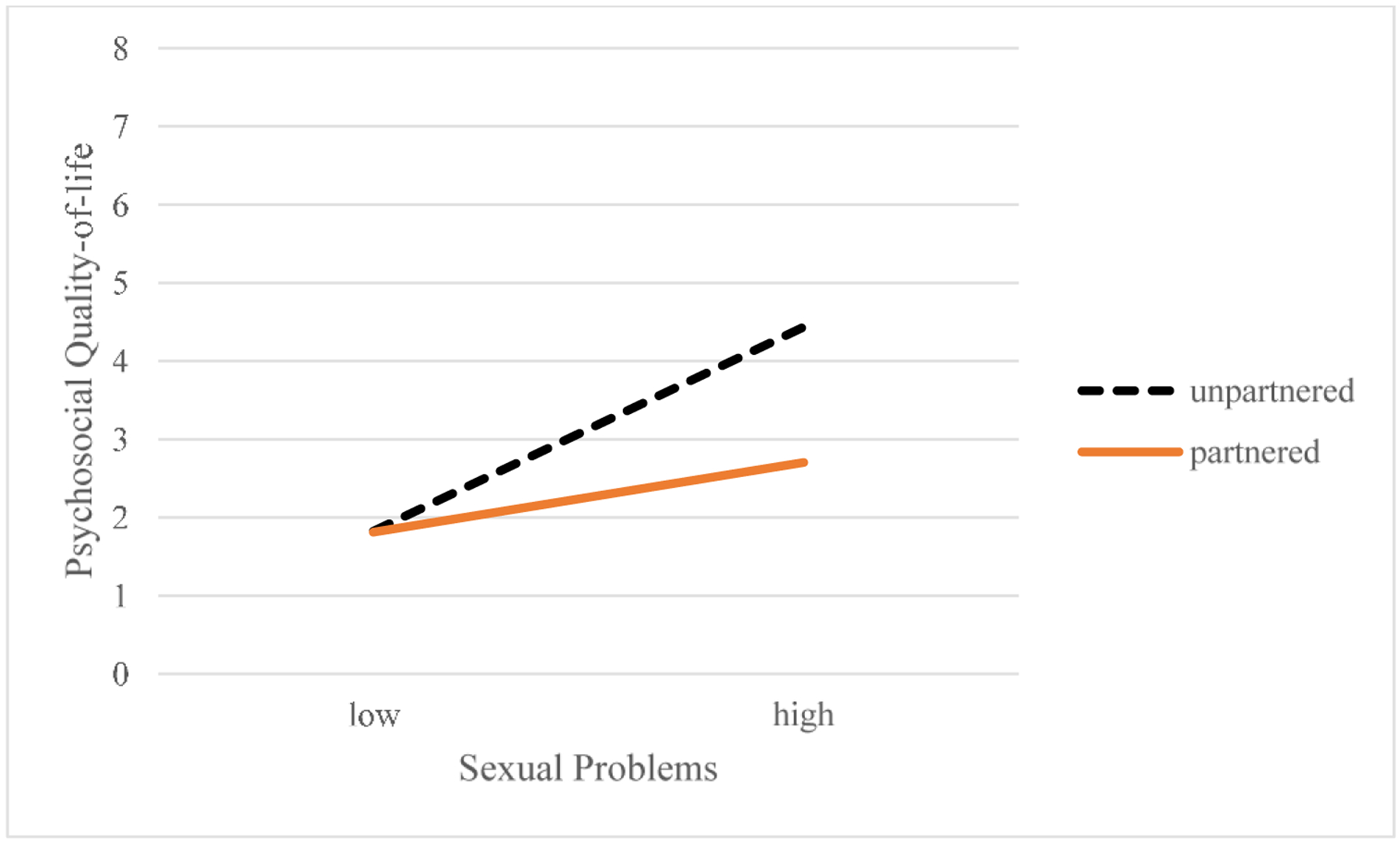

Variables significantly associated with outcome variables in bivariate analyses were included as covariates in the respective regression analyses. Table 2 presents the multiple linear regression results; unstandardized regression coefficients and standard errors are presented. The model examining the relationship between sexual problems and psychosocial quality-of-life accounted for significant variance in psychosocial quality-of-life [total R2=0.247, F(4, 100)=8.21, p<.001]. The interaction between sexual problems and partner status was significant (B=−0.40, SE=0.17, t= −2.39, p=0.02). This suggests that the relationship between sexual problems and psychosocial quality-of-life differed by partner status. Figure 1 displays the relationship between sexual problems and psychosocial quality-of-life by partner status. Examination of simple slopes analyses found the slopes to be significant for both partnered (B=0.21, SE=0.08, t=2.70, p=0.04) and unpartnered women (B=0.61, SE=0.15, t=4.04, p=0.01). Results suggest a significant positive relationship between sexual problems and psychosocial quality-of-life for both partnered and unpartnered women such that women with fewer sexual problems had better psychosocial quality-of-life; however, at high levels of sexual problems, unpartnered women experienced poorer psychosocial quality-of-life when compared to partnered women. Age was examined as a potential covariate in these models and did not significantly impact results.

Table 2.

Multiple Regression Analyses.

| B | Standard Error | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial Quality-of-life (total R2=0.247)a | ||||

| Constant | 3.129 | 0.345 | 9.063 | <0.001 |

| ACE-27 Score | 0.354 | 0.157 | 2.260 | 0.026 |

| Sexual Problems | 0.612 | 0.153 | 4.009 | <0.001 |

| Partner Status | −0.871 | 0.332 | −2.624 | 0.010 |

| Sexual Problems X Partner Status | −0.403 | 0.169 | −2.385 | 0.019 |

| Psychosocial Quality-of-life (total R2=0.247)a | ||||

| Constant | 2.631 | 0.333 | 7.910 | <0.001 |

| ACE-27 Score | 0.263 | 0.166 | 1.580 | 0.117 |

| Self-Efficacy | −0.038 | 0.008 | −4.636 | <0.001 |

| Partner Status | −0.205 | 0.320 | −0.640 | 0.524 |

| Self-Efficacy X Partner Status | 0.027 | 0.010 | 2.768 | 0.007 |

| Satisfaction with Sex Life (total R2=0.383)b | ||||

| Constant | −0.530 | 1.242 | −0.427 | 0.672 |

| Age | 0.036 | 0.018 | 1.974 | 0.052 |

| Receipt of Chemotherapy | −0.261 | 0.305 | −0.855 | 0.395 |

| Sexual Problems | −0.611 | 0.217 | −2.813 | 0.006 |

| Partner Status | 0.681 | 0.385 | 1.767 | 0.082 |

| Sexual Problems X Partner Status | 0.248 | 0.229 | 1.081 | 0.283 |

| Satisfaction with Sex Life (total R2=0.197)b | ||||

| Constant | 0.377 | 1.475 | 0.256 | 0.799 |

| Age | 0.030 | 0.021 | 1.387 | 0.170 |

| Receipt of Chemotherapy | −0.489 | 0.347 | −1.411 | 0.163 |

| Self-Efficacy | 0.024 | 0.011 | 2.122 | 0.037 |

| Partner Status | 0.144 | 0.416 | 0.345 | 0.731 |

| Self-Efficacy X Partner Status | −0.011 | 0.013 | −0.876 | 0.384 |

Notes- ACE-27: Adult Comorbidity Evaluation; For all models, beta estimates correspond to the number of units the predicted value of the dependent variable changes when the independent variable changes by 1 unit. For example, women rated their self-efficacy on a 10-point scale ranging from 10 to 100. For the model with psychosocial quality of life as an outcome, for every 10 point change in self-efficacy, you get a 3.8 point change in the outcome variable. For the model with sexual satisfaction as an outcome, for every 10 point change in self-efficacy, you get a 2.4 point change in the outcome variable.”

Higher scores indicate poorer psychosocial quality-of-life

The Satisfaction with Sex Life item was added midway through data collection; thus, the total sample size possible for this variable was n=79

Figure 1.

Plot of sexual problems X partner status interaction term shows that the relationship between sexual problems and psychosocial quality-of-life differs by partner status. Note- Higher scores indicate poorer psychosocial quality-of-life.

The model examining the relationship between sexual self-efficacy and psychosocial quality-of-life accounted for significant variance in psychosocial quality-of-life [total R2=0.247, F(4, 93)=7.63, p<.001]. The interaction term between self-efficacy and partner status was significant (B=0.03, SE=0.01, t= 2.77, p=0.01). Figure 2 displays the relationship between sexual self-efficacy and psychosocial quality-of-life by partner status. Examination of simple slopes analyses found the slope of the relationship between sexual self-efficacy and psychosocial quality-of-life to be significant for unpartnered women (B=−0.04, SE=0.01, t=−4.91, p=0.003); the slope did not significantly differ from zero for the partnered participants (B=−0.01, SE=0.02, t=0.65, p=0.54). This suggests that self-efficacy for managing sexual problems is unrelated to psychosocial quality-of-life for partnered women, while for unpartnered women, low self-efficacy is associated with poorer psychosocial quality-of-life.

Figure 2.

Plot of self-efficacy for managing sexual problems X partner status interaction term shows that the relationship between self-efficacy and psychosocial quality-of-life differs by partner status. Note- Higher scores indicate poorer psychosocial quality-of-life.

The model examining the relationship between sexual problems and sexual satisfaction accounted for significant variance in sexual satisfaction [total R2=0.383, F(5, 69)=8.58, p<.001]. The interaction between sexual problems and partner status was not significant (B=0.25, SE=0.23, t= 1.08, p=0.28). There was a significant main effect for sexual problems such that, after controlling for covariates and partner status, women reporting more sexual problems experienced less satisfaction with their sex lives (B=−0.61, SE=0.22, t= −2.81 p=0.01). Similarly, the model examining the relationship between sexual self-efficacy and sexual satisfaction accounted for significant variance in sexual satisfaction [total R2=0.197, F(5, 71)=3.49, p<.001]. The interaction between sexual self-efficacy and partner status was not significant (B=−0.01, SE=0.01, t= −0.88, p=0.38). There was a significant main effect for self-efficacy such that, after controlling for covariates and partner status, women reporting greater sexual self-efficacy experienced greater satisfaction with their sex lives (B=0.02, SE=0.01, t= 2.12, p=0.04).

Discussion

The present study examined the relationships between sexual problems and self-efficacy for managing sexual problems and quality-of-life for postmenopausal breast cancer survivors receiving AET. Our findings suggest that sexual problems and low sexual self-efficacy are associated with poorer quality-of-life—specifically, psychosocial quality-of-life and sexual satisfaction—for this important and growing group of breast cancer survivors. Additionally, we examined partner status as a potential moderator. Unpartnered women with low levels of self-efficacy and more sexual problems experienced poorer psychosocial quality-of-life when compared to partnered women. Our findings suggest that being unpartnered may exacerbate the impact of sexual problems and poor sexual self-efficacy on psychosocial quality-of-life for postmenopausal breast cancer survivors receiving AET.

Given the high prevalence of sexual problems among postmenopausal women receiving AET and the long treatment course (5–10 years), it is important to understand factors that may impact women’s quality-of-life and identify points for intervention. The results of the present study suggest that sexual problems and sexual self-efficacy may be important intervention targets. However, to the best of our knowledge interventions developed to address the specific sexual health needs of postmenopausal women receiving AET have yet to be developed. Sex therapy incorporates strategies (e.g., sensate focus, cognitive-behavioral techniques) to directly target sexual problems.57 While few randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have evaluated sex therapy as a treatment for sexual problems for breast cancer survivors, those that have included sex therapy—as opposed to other types of interventions to address sexual problems (e.g., psychoeducation about the effect of cancer treatments on sexual health, exercise interventions)—have been found to be efficacious and result in significant improvement in women’s sexual symptoms.58–62 The present study suggests that postmenopausal women receiving AET are appropriate candidates for sex therapy interventions to target their AET-specific sexual health concerns.

In the present study, survivors’ sexual self-efficacy was found to be low; this is consistent with prior research suggesting that breast cancer survivors have significant unmet sexual health needs.63 To our knowledge, RCTs of sex therapy interventions for breast cancer survivors have failed to examine the effect of the intervention on breast cancer patients’ sexual self-efficacy. It is possible that instruction in sex therapy techniques may improve women’s sexual self-efficacy and, in turn, improve their quality-of-life. Our work and the work of others has found self-efficacy for coping with specific domains (e.g., stress, symptoms) to be positively associated with quality-of-life among cancer survivors.42, 43 There are several techniques that have been used to improve self-efficacy including providing feedback on skill use, discussing barriers and roadblocks, and modeling of problem solving, communication, and coping skills; the results of the present study suggest that novel sex therapy interventions developed for breast cancer survivors on AET may benefit from the inclusion of these techniques.

The results of models examining sexual satisfaction suggest that sexual problems and sexual self-efficacy are associated with satisfaction with one’s sex life irrespective of partner status. The small sample size for individuals completing the sexual satisfaction item (n=79) and the fact that women who were not asked this item were less likely to be partnered may have limited our ability to examine the impact of partner status on the relationships between sexual problems or sexual self-efficacy and sexual satisfaction. Future research utilizing a larger sample of postmenopausal breast cancer survivors receiving AET should attempt to better understand the effect of partner status on sexual satisfaction.

This research is timely. In recognition of the impact of cancer and treatments on patients’ sexual health, the American Society of Clinical Oncology convened an expert panel in February 2018 to establish guidelines and recommendations for the assessment and treatment of sexual problems for cancer survivors.64 It was recommended that members of a patient’s healthcare team initiate discussions regarding cancer-related sexual problems and provide appropriate resources or referral information (e.g., to psychosocial and/or sexual health counseling). The results of the present study speak to the need to intervene with unpartnered, postmenopausal breast cancer survivors on AET as well as those reporting more sexual problems and/or low self-efficacy for managing sexual problems. Members of the healthcare team can use this information to inform their discussions and recommendations for interventions or referrals and, ultimately, assist with improving patients’ quality-of-life.

Although a large portion of breast cancer survivors are interested in receiving care for their sexual problems,65 many report unmet sexual health needs.63 Despite the aforementioned guidelines and recommendations, research suggests that conversations with medical providers about patients’ sexual problems are rare.63, 66, 67 The frequency of these discussions may be impacted by patient and provider-level factors such as: 1) a mismatch in patient and provider priorities during medical visits (e.g., providers prioritizing other cancer-related issues over sexual health concerns); 2) patients’ discomfort with bringing up their sexual problems to their providers; 3) providers’ lack of training in sexual health; or 4) providers’ discomfort and lack of confidence with discussing/addressing patients’ sexual health concerns (e.g., uncertainty about who and how to refer patients for sexual counseling).66, 68, 69 Buzaglo and colleagues found that, while 80% of breast cancer survivors reported experiencing at least one sexual problem, only 20% had been asked about sexual problems by a member of their health care team, and only 17% had sought treatment for their sexual problems.63 The lack of communication about and resources available to patients for addressing their sexual problems may impact women’s self-efficacy for coping with these significant treatment-related side effects. Unmet sexual health needs may result in poor quality-of-life for breast cancer survivors.70

Evidence suggests that breast cancer survivors’ relationship status may influence the initiation of sexual health discussions between providers and patients. Despite the fact that sexual problems can affect breast cancer survivors regardless of whether women are in intimate relationships,44 members of a patient’s healthcare team may choose whether or not to initiate conversations about sexual problems based on whether a woman is partnered.71 In some cases, the assumption that sexual side effects are not a concern for unpartnered women may serve as a barrier to discussions about sexual problems and receipt of appropriate interventions.72 Thus, unpartnered women may be at a greater risk for poor self-efficacy for coping with sexual problems. The present study suggests that, when compared to partnered women, unpartnered women with low self-efficacy for managing sexual problems experienced worse psychosocial quality-of-life when compared to partnered women and speaks to the importance of engaging unpartnered women in discussions of sexual health concerns.

This study has several limitations. First, we examined the relationships between sexual problems and sexual self-efficacy and quality-of-life for postmenopausal breast cancer survivors receiving AET. Thus, the results may not generalize to male or other cancer survivors (e.g., ovarian or prostate) receiving endocrine therapy and to pre or perimenopausal women. Second, the sample was primarily White, well-educated and older, which may further limit the generalizability of these results. Third, this study employed a cross-sectional design. Thus, causality cannot be determined. A larger, longitudinal study is necessary to examine the direction of the relationships between study variables.

Fourth, while partner status was assessed, we did not assess the quality of survivors’ partnered relationships. Poor quality relationships have been linked to lower quality-of-life among the general population73 and for breast cancer survivors.74 It is possible that the relationships between study variables may differ for those who are more or less satisfied with their relationships. Finally, a comprehensive assessment of sexual concerns and distress surrounding sexual concerns, like the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI)75 and the Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS-R),76, 77 were not included in the present study. The FSFI produces scores across six sexual functioning domains including desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. The FSDS-R assesses sexually-related personal distress in women. While our results provide preliminary evidence of the relationship between sexual problems and psychosocial quality-of-life and the impact of partner status on this relationship, we cannot be sure that these relationships hold for specific domains of sexual function (e.g., desire, arousal, orgasm, pain) and sexual distress. Future research should utilize a more comprehensive assessment tool.

Conclusion

The present study is one of only a few to examine relationships between sexual problems and self-efficacy for managing sexual problems and quality-of-life domains for postmenopausal breast cancer survivors taking AET. Additionally, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine partner status as a moderator of these relationships. The study findings suggest that unpartnered postmenopausal women with greater sexual problems or lower self-efficacy may be at a greater risk for poor quality-of-life than partnered women. Interventions to improve sexual problems and women’s sexual self-efficacy, particularly among unpartnered, postmenopausal women, may be beneficial for improving the wellbeing of breast cancer survivors on AET.

Funding Source:

K07CA138767

Footnotes

Financial disclosures/conflicts of Interest: None reported.

An abstract presenting this work was previously presented. The citation is listed below:

Dorfman, C.S., Arthur, S.S., Kimmick, G., Westbrook, K., Marcom, K., Edmond, S.N., Shelby, R.A. (September 2018). Partner Status Moderates the Relationship between Sexual Problems and Self-efficacy for Managing Sexual Problems and Psychosocial Quality-of-Life for Breast Cancer Survivors taking Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy. Poster presented at the 6th Conference of the Scientific Network on Female Sexual Health and Cancer, Durham, NC.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2018. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2017–2018. In: Society AC, editor. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Breast Cancer. National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc.; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies C, Pan H, Godwin J, et al. Long-term effects of continuing adjuvant tamoxifen to 10 years versus stopping at 5 years after diagnosis of oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: ATLAS, a randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9869):805–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burstein HJ, Temin S, Anderson H, et al. Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy for Women With Hormone Receptor–Positive Breast Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Focused Update. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(21):2255–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ziller V, Kalder M, Albert US, et al. Adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy in postmenopausal women with breast cancer. Annals of Oncology. 2009;20(3):431–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy CC, Bartholomew LK, Carpentier MY, Bluethmann SM, Vernon SW. Adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy among breast cancer survivors in clinical practice: A systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134(2):459–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chlebowski RT, Geller ML. Adherence to Endocrine Therapy for Breast Cancer. Oncology. 2006;71(1–2):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson AM, Dewar J, Fahey T, McCowan C. Association of poor adherence to prescribed tamoxifen with risk of death from breast cancer. Breast Cancer Symposium. 2007;Abstract 130. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barron TI, Cahir C, Sharp L, Bennett K. A nested case-control study of adjuvant hormonal therapy persistence and compliance, and early breast cancer recurrence in women with stage I-III breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(6):1513–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Makubate B, Donnan PT, Dewar JA, Thompson AM, McCowan C. Cohort study of adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy, breast cancer recurrence and mortality. Br J Cancer. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] 2013;108(7):1515–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCowan C, Wang S, Thompson AM, Makubate B, Petrie DJ. The value of high adherence to tamoxifen in women with breast cancer: A community-based cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(5):1172–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aiello Bowles EJ, Boudreau DM, Chubak J, et al. Patient-reported discontinuation of endocrine therapy and related adverse effects among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8(6):e149–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Owusu C, Buist DSM, Field TS, et al. Predictors of tamoxifen discontinuation among older women with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(4):549–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lash TL, Fox MP, Westrup JL, Fink AK, Silliman RA. Adherence to tamoxifen over the five-year course. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2006;99(2):215–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grunfeld EA, Hunter MS, Sikka P, Mittal S. Adherence beliefs among breast cancer patients taking tamoxifen. Patient Education and Counseling. 2005;59(1):97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahn KL, Schneider EC, Malin JL, Adams JL, Epstein AM. Patient centered experiences in breast cancer - Predicting long-term adherence to tamoxifen use. Medical Care. 2007;45(5):431–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cella D, Fallowfield LJ. Recognition and management of treatment-related side effects for breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2008;107(2):167–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fallowfield L, Cella D, Cuzick J, Francis S, Locker G, Howell A. Quality of life of postmenopausal women in the Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination (ATAC) Adjuvant Breast Cancer Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(21):4261–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donnellan PP, Douglas SL, Cameron DA, Leonard RC. Aromatase inhibitors and arthralgia. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(10):2767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crew KD, Greenlee H, Capodice J, et al. Prevalence of joint symptoms in postmenopausal women taking aromatase inhibitors for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(25):3877–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hadji P Menopausal symptoms and adjuvant therapy-associated adverse events. 2008;15(1):73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schover LR, Baum GP, Fuson LA, Brewster A, Melhem-Bertrandt A. Sexual problems during the first 2 years of adjuvant treatment with aromatase inhibitors. J Sex Med. 2014;11(12):3102–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mortimer JE, Boucher L, Baty J, Knapp DL, Ryan E, Rowland JH. Effect of Tamoxifen on Sexual Functioning in Patients With Breast Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1999;17(5):1488-. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gomes de Souza Pegorare AB, da Rosa Silveira K, Simones No AP, Miziara Barbosa SR,. Assessment of Female Sexual Function and Quality of Life Among Breast Cancer Survivors who Underwent Hormone Therapy. Mastology. 2017;27(3):237–44. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frechette D, Paquet L, Verma S, et al. The impact of endocrine therapy on sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women with early stage breast cancer: Encouraging results from a prospective study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;141(1):111–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fallowfield LJ, Kilburn LS, Langridge C, et al. Long-term assessment of quality of life in the Intergroup Exemestane Study: 5 years post-randomisation. Br J Cancer. 2012;106(6):1062–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kyvernitakis I, Ziller V, Hars O, Bauer M, Kalder M, Hadji P. Prevalence of menopausal symptoms and their influence on adherence in women with breast cancer. Climacteric. 2014;17(3):252–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berglund G, Nystedt M, Bolund C, Sjoden PO, Rutquist LE. Effect of endocrine treatment on sexuality in premenopausal breast cancer patients: a prospective randomized study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(11):2788–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burstein HJ, Lacchetti C, Anderson H, et al. Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy for Women With Hormone Receptor–Positive Breast Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update on Ovarian Suppression. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34(14):1689–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nappi PRE, Cucinella L, Martella S, Rossi M, Tiranini L, Martini E. Female sexual dysfunction (FSD): Prevalence and impact on quality of life (QoL). Maturitas. 2016;94:87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amini Lari M, Faramarzi H, Shams M, Marzban M, Joulaei H. Sexual Dysfunction, Depression and Quality of Life in Patients With HIV Infection. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2013;7(1):61–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santos PR, Capote JR Jr., Cavalcanti JU, et al. Quality of life among women with sexual dysfunction undergoing hemodialysis: A cross-sectional observational study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Milbury K, Badr H. Sexual problems, communication patterns, and depressive symptoms in couples coping with metastatic breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22(4):814–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Safarinejad MR, Shafiei N, Safarinejad S. Quality of life and sexual functioning in young women with early-stage breast cancer 1 year after lumpectomy. Psychooncology. 2013;22(6):1242–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Belin TR, Meyerowitz BE, Rowland JH. Predictors of sexual health in women after a breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(8):2371–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coster S, Fallowfield LJ. The impact of endocrine therapy on patients with breast cancer: A review of the literature. The Breast. 2002;11(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wagner LI, Zhao F, Goss PE, et al. Patient-reported predictors of early treatment discontinuation: Treatment-related symptoms and health-related quality of life among postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer randomized to anastrozole or exemestane on NCIC Clinical Trials Group (CCTG) MA.27 (E1Z03). Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2018;169(3):537–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frechette D, Paquet L, Verma S, et al. The impact of endocrine therapy on sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women with early stage breast cancer: Encouraging results from a prospective study. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2013;141(1):111–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bandura A Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychology & Health. 1998;13(4):623–49. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bandura A Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist. 1982;37(2):122–47. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shelby RA, Edmond SN, Wren AA, et al. Self-efficacy for coping with symptoms moderates the relationship between physical symptoms and well-being in breast cancer survivors taking adjuvant endocrine therapy. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2014;22(10):2851–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haas BK. Fatigue, Self-efficacy, Physical Activity, and Quality of Life in Women With Breast Cancer. Cancer Nursing. 2011;34(4):322–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raggio GA, Butryn ML, Arigo D, Mikorski R, Palmer SC. Prevalence and correlates of sexual morbidity in long-term breast cancer survivors. Psychol Health. 2014;29(6):632–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kinsinger SW, Laurenceau JP, Carver CS, Antoni MH. Perceived partner support and psychosexual adjustment to breast cancer. Psychol Health. 2011;26(12):1571–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ganz PA, Rowland JH, Desmond K, Meyerowitz BE, Wyatt GE. Life after breast cancer: understanding women’s health-related quality of life and sexual functioning. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(2):501–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gluhoski VL, Siegel K, Gorey E. Unique Stressors Experienced by Unmarried Women with Breast Cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1998;15(3–4):173–83. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kurowecki D, Fergus KD. Wearing my heart on my chest: dating, new relationships, and the reconfiguration of self-esteem after breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2014;23(1):52–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kimmick G, Edmond SN, Bosworth HB, et al. Medication taking behaviors among breast cancer patients on adjuvant endocrine therapy. The Breast. 2015;24(5):630–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Piccirillo JF, Tierney RM, Costas I, Grove L, Spitznagel J, Edward L. Prognostic Importance of Comorbidity in a Hospital-Based Cancer Registry. JAMA. 2004;291(20):2441–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hilditch JR, Lewis J, Peter A, et al. A menopause-specific quality of life questionnaire: development and psychometric properties. Maturitas. 1996;24(3):161–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Radtke JV, Terhorst L, Cohen SM. The Menopause-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire: psychometric evaluation among breast cancer survivors. Menopause. 2011;18(3):289–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lorig K, Chastain RL, Ung E, Shoor S, Holman HR. Development and evaluation of a scale to measure perceived self-efficacy in people with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32(1):37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1993;11(3):570–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burwell SR, Case LD, Kaelin C, Avis NE. Sexual Problems in Younger Women After Breast Cancer Surgery. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(18):2815–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31(4):437–48. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaplan HS. The illustrated manual of sex therapy. 2nd ed. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Taylor S, Harley C, Ziegler L, Brown J, Velikova G. Interventions for sexual problems following treatment for breast cancer: A systematic review. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. [journal article]. 2011;130(3):711–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carroll AJ, Baron SR, Carroll RA. Couple-based treatment for sexual problems following breast cancer: A review and synthesis of the literature. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(8):3651–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seav SM, Dominick SA, Stepanyuk B, et al. Management of sexual dysfunction in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review. Women’s Midlife Health. 2015;1(1):9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Crespi CM, et al. Addressing intimacy and partner communication after breast cancer: A randomized controlled group intervention. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2009;118(1):99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hummel SB, Lankveld JJDMv, Oldenburg HSA, et al. Efficacy of Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Improving Sexual Functioning of Breast Cancer Survivors: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(12):1328–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Buzaglo JS, Miller MF, Andersen BL, Longacre M, Robinson PA. Sexual morbidity and unmet needs among members of a metastatic breast cancer registry. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33(15_suppl):9585. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carter J, Lacchetti C, Andersen BL, et al. Interventions to Address Sexual Problems in People With Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Adaptation of Cancer Care Ontario Guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36(5):492–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hill EK, Sandbo S, Abramsohn E, et al. Assessing gynecologic and breast cancer survivors’ sexual health care needs. Cancer. 2011;117(12):2643–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hordern AJ, Street AF. Communicating about patient sexuality and intimacy after cancer: Mismatched expectations and unmet needs. Med J Aust. 2007;186(5):224–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Flynn KE, Reese JB, Jeffery DD, et al. Patient experiences with communication about sex during and after treatment for cancer. Psychooncology. 2012;21(6):594–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bober SL, Reese JB, Barbera L, et al. How to ask and what to do: A guide for clinical inquiry and intervention regarding female sexual health after cancer. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2016;10(1):44–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bober SL, Recklitis CJ, Campbell EG, et al. Caring for cancer survivors. Cancer. 2009;115(18):4409–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Park B-W, Hwang SY. Unmet Needs and Their Relationship with Quality of Life among Women with Recurrent Breast Cancer. J Breast Cancer. 2012;15(4):454–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dizon DS, Suzin D, McIlvenna S. Sexual health as a survivorship issue for female cancer survivors. Oncologist. 2014;19(2):202–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hordern AJ, Street AF. Let’s talk about sex: risky business for cancer and palliative care clinicians. Contemp Nurse. 2007;27(1):49–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Robles TF, Slatcher RB, Trombello JM, McGinn MM. Marital quality and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2014;140(1):140–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tânia B, Juliana P, Nuno N, V. MM, Emília CM, Mena MP. Marital adjustment in the context of female breast cancer: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology. 2017;26(12):2019–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(2):191–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Derogatis LR, Rosen R, Leiblum S, Burnett A, Heiman J. The Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS): initial validation of a standardized scale for assessment of sexually related personal distress in women. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28(4):317–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Derogatis L, Clayton A, Lewis-D’Agostino D, Wunderlich G, Fu Y. Validation of the female sexual distress scale-revised for assessing distress in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Sex Med. 2008;5(2):357–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]