Abstract

In this work, a mild and sustainable catalytic aerobic epoxidation of alkenes catalyzed by cobalt porphyrin was performed in the presence of sunflower seeds oil. Under ambient conditions, the conversion rate of trans-stilbene reached 99%, and selectivity toward epoxide formation was 88%. The kinetic studies showed that the aerobic epoxidation followed the Michaelis–Menten kinetics. Mass spectroscopy and in situ electron spin resonance indicated that linoleic acid was converted to fatty aldehydes via hydroperoxide intermediates. A plausible mechanism of epoxidation of alkenes was accordingly proposed.

1. Introduction

The selective epoxidation of alkenes to epoxides has recently attracted great interest in both academic and industrial fields due to the broad applications of epoxides in organic synthesis.1−3 Various oxidants, such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2),4tert-butyl hydroperoxide,5 oxone,6 iodosobenzene,7 and peracids,8 have been employed as oxidants. Compared to these oxidants, molecular oxygen (O2) is more attractive species due to its low cost and environmental friendless. However, it is spin-forbidden between the triplet oxygen molecule and the singlet organic molecule, which suppresses the occurrence of direct epoxidation.9

Fortunately, biocatalytic oxyfunctionalizations often help in activating O2.10,11 These processes utilize co-substrates like glucose, H2, or ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) to in situ generate H2O2. This route is most convenient to sustain H2O2 at optimal levels. Some successful biomimetic studies have been attempted to activate O2 through in situ transformation to hydroperoxides in the presence of specific co-substrates, such as cumene and ethylbenzene.12−15 However, current methods still require improvements in terms of high temperature, high pressure, and additional free-radical initiators. Aldehydes have successfully been used for epoxidation of alkenes through intermediates active oxygen species (peroxyacid or acylperoxy radical) under mild conditions (Mukaiyama mechanism).16−18 However, the rapid exothermic reactions and high cost dramatically limited their further industrial applications.19

Plant oils consisting of mainly unsaturated fatty acids (UFAs) are low cost and abundant renewable biomass sources.20 Recently, the transformation of UFAs to diverse valuable organic acids through selective oxidative cleavage of C–C bond has attracted increasing attention.21 Linoleic acid is a major UFA constituent of most plant oils and tall oil (a by-product of pulping industry).22 Linoleic acid readily undergoes auto-oxidation under mild conditions because of its highly active bisallylic C–H bonds.23 For instance, Hauer and co-workers24,25 reported multiple enzyme-catalyzed conversions of linoleic acid through linoleic acid hydroperoxide (LAOOH) intermediate transformation into an aldehyde like 9-oxononanoic acid. The latter could further be converted into azelaic acid, a precursor in the synthesis of advanced Nylon-6,9.26

Considering in situ generation of aldehydes from linoleic acid, the catalytic epoxidation of alkenes could probably be achieved using sunflower seeds oil due to the presence of a high linoleic acid content (70 wt %). With this idea in mind, the epoxidation of alkenes catalyzed by cobalt meso-tetraphenylporphyrin (CoPor) in the presence of linoleic acid was tested here under ambient conditions. To the best of our knowledge, aerobic epoxidation of alkenes with linoleic acid as a co-substrate has so far not been reported. The aim of this investigation was to develop a green and sustainable catalytic epoxidation process. It was found that the conversion rate of trans-stilbene could reach 99%, and selectivity toward epoxide formation was 88% under ambient conditions. To gain a better understanding, the role of linoleic acid and the catalytic mechanism were explored by means of mass spectroscopy (MS) and in situ electron spin resonance (ESR).

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials and Methods

Unless stated otherwise, all chemical reagents were acquired from commercial sources and used without further purification. CoPor, FePor, and MnPor (Por: meso-tetraphenylporphyrins) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Edible sunflower seeds oil was obtained from Kerry Oils and Grains Company. 9-Oxononanoic acid was purchased from Bide Pharmatech Ltd.

The reactants and products were quantified by a GC2010 gas chromatograph (Shimadzu) equipped with a flame ionization detector and capillary column (Rtx-5, 30 m × 0.32 mm × 0.25 μm) and biphenyl-based internal standard method. The gas chromatograph mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analyses were performed on a GCMS-2010 plus gas chromatograph mass spectrometer (Shimadzu) equipped with a capillary column (Rtx-5, 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) in electron impact mode. The ESR spectra were recorded on a JEOL JES-FA2000 ESR spectrometer equipped with a Wilmad WG-810-A quartz flat cell. The mass spectra were collected on a ThermoFisher TSQ Quantum Ultra electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) and tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS-MS) with negative mode. ESI-MS-MS spectra of molecular ions were obtained using collision-induced dissociation between 15 and 35 V. The electrospray conditions were set to a nitrogen sheath gas of 45 arb, a spray voltage of 3.0 kV, a capillary temperature of 300 °C, and a vaporizer temperature of 200 °C. The photocatalytic synthesis of LAOOH was performed on a PCX50B Discover multichannel photochemical reaction system (Beijing Perfect light) equipped with white LED lamps (400–800 nm, 90 mW/cm2).

2.2. Synthesis of Linoleic Acid Hydroperoxides (LAOOH)

LAOOH was synthesized according to the literature with slight modifications.27 Briefly, linoleic acid (10 g, 35.7 mmol), 1 mL of methylene blue solution (100 mM in methanol), and chloroform (30 mL) were added to a 60 mL transparent glass bottle. The mixture was bubbled with O2 for 30 min then sealed to prevent oxygen from escaping. The mixture was then stirred at room temperature for 12 h under irradiation using a white LED lamp. After completion of the reaction, LAOOH was purified by silica gel column chromatography following the procedure reported by Kuhn et al.28 Next, the solvents were removed under reduced pressure to yield LAOOH (24% yield). Afterward, LAOOH was again dissolved in acetonitrile (10 mL) and stored at −20 °C. The structure of LAOOH was confirmed by ESI-MS. As shown in Figure S1, m/z = 311.14 was assigned to [M – H]− in LAOOH, and m/z = 293.32 was attributed to the [M – H2O – H]− ion in the dehydrated product, consistent with previous reports.27,29

2.3. General Procedures of Alkenes Aerobic Epoxidation

For aerobic epoxidation, a mixture containing the alkene (0.5 mmol), metalloporphyrin catalyst (0.8 mol %), co-substrate (2.5 mmol), acetonitrile (5 mL), and biphenyl (0.5 mmol) as an internal standard and a magnetic stirrer were first added to a 10 mL stainless steel autoclave reactor subjected to 0.5 MPa O2 or a 20 mL two-necked flask with a reflux condenser under 10 mL/min O2 bubbling. The mixture was then stirred at 80 °C for 12 h. After completion of the reaction, the oxidation products of alkenes were analyzed by GC. The organic acid products issued from linoleic acid oxidative cleavage were also determined by GC-MS analyses of the esterifiable reaction mixture. Briefly, the sample (0.5 mL) containing heptadecanoic acid (20 mM) as an internal standard, methanol (2 mL) containing butylated hydroxytoluene (0.05 M) as an antioxidant, and concentrated H2SO4 (0.2 mL) were all added to a pressure bottle (25 mL). The mixture was next degassed by three freeze–pump–thaw cycles then filled with N2. The obtained mixture was further stirred at 65 °C for 0.5 h. After methyl esterification, H2O (5 mL) and n-hexane (5 mL) were added to the mixture, and the supernate was employed in GC-MS analyses.

2.4. In Situ ESR Measurements

ESR spectra were recorded on a Wilmad WG-810-A quartz flat cell in an O2- or N2-substrated acetonitrile solutions of linoleic acid (0.5 M) and CoPor (0.8 mM) using 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO; 100 mM) as a trapping agent. The ESR analyses were performed at the microwave frequency of 9.21 GHz and 80 °C.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Catalytic Aerobic Epoxidation of trans-Stilbene

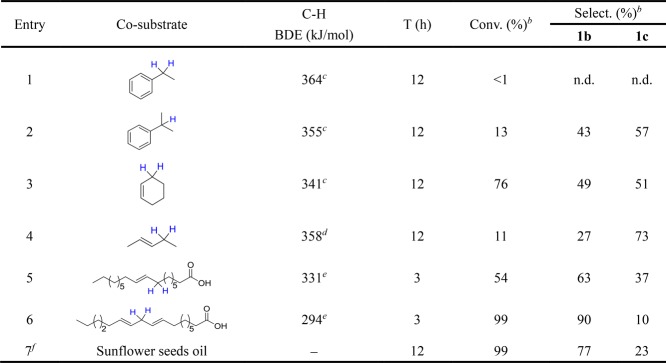

To determine the catalytic activities of various co-substrates, the epoxidation of trans-stilbene (model substrate, 1a) was first performed under O2 (0.5 MPa) and CoPor catalyst. The main oxidation products were determined as trans-stilbene epoxide (1b) and benzaldehyde (1c). By comparison, the epoxidation did not proceed in the presence of ethylbenzene (Table 1, entry 1), which could be attributed to the high secondary C–H bond dissociation enthalpy (BDE) of ethylbenzene leading to hard activation at a low temperature.30 For cumene, the conversion rate and selectivity toward epoxide formation were estimated to be 13 and 43%, respectively (Table 1, entry 2). This may be ascribed to the low C–H (tertiary carbon–hydrogen) BDE (355 kJ/mol) of cumene when compared to that of ethylbenzene (364 kJ/mol).

Table 1. Aerobic Epoxidation of trans-Stilbene Catalyzed by CoPor Using Different Co-Substratesa.

The catalytic activities of allylic compounds were subsequently explored. Using cyclohexene as the co-substrate, the conversion rate was calculated as 76%, and selectivity toward epoxide formation was 49% (Table 1, entry 3). The allylic position of cyclohexene is considered as the most active site, where cyclohexenyl hydroperoxide is generated and readily decomposed into allylic products (alcohol and ketone) (Figure S2).34 Here, straight-chain allylic compounds, including 2-pentene, oleic acid, and linoleic acid, were employed as co-substrates. In the presence of 2-pentene, the conversion rate was estimated to 11%, and selectivity toward epoxide formation was 27% (Table 1, entry 4). These values enhanced by using long straight-chain oleic acid instead of 2-pentene after 3 h reaction time (Table 1, entry 5), which might be linked to rationalized C–H BDEs of 2-pentene (358 kJ/mol) and oleic acid (331 kJ/mol).

As expected, the conversion rate of bisallylic linoleic acid after 3 h reaction time reached 99%, and selectivity toward epoxide formation was 90% (Table 1, entry 6). These values were much larger than those of oleic acid under the same reaction conditions. This could be due to bisallylic C–H BDE (294 kJ/mol) in linoleic acid, which was much lower than allylic C–H BDE (331 kJ/mol) in oleic acid. In addition, because linoleic acid widely existed in plant oils, linoleic acid was replaced by edible sunflower seeds oil to achieve 99% conversion and 77% selectivity (Table 1, entry 7). Based on the above results, a low C–H BDE of the co-substrate would benefit the epoxidation of trans-stilbene, and different epoxidation rates using various co-substrates were confirmed by kinetic studies (Figure S3).

3.2. Optimized Conditions and Substrate Scope

After affirming linoleic acid as the optimal co-substrate, epoxidation of trans-stilbene was performed at atmospheric pressure by bubbling O2 at 10 mL/min. The conversion rate and selectivity toward formation of epoxide were estimated to be 99 and 88% (Table 2, entry 1), respectively. Meanwhile, the reaction mixture was treated with methyl esterification and then analyzed by GC-MS to determine distribution of oxidative cleavage products issued from linoleic acid. Figure S4 reveals the main organic acid as n-hexanoic acid (6% yield) and azelaic acid (11% yield) with some fatty aldehydes (n-hexanal and 9-oxononanoic acid). Though these organic acid product yields seemed average due to the great difficulty in oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids cleavage by O2,21 the coupling of alkene epoxidation and linoleic acid transformation was still significant.

Table 2. Optimized Conditions and Substrate Scopea.

Reaction conditions: substrate (0.5 mmol), catalyst (0.8 mol %), biphenyl (0.5 mmol) as an internal standard, acetonitrile (5 mL), O2 (10 mL/min), and 12 h.

Determined by GC and selectivity to corresponding epoxide.

0.02 mol % CoPor.

Subsequently, the blank experiments revealed that epoxidation of trans-stilbene did not proceed in the absence of linoleic acid (Table 2, entry 2), and 22% conversion rate with 46% selectivity toward epoxide formation was achieved in the absence of CoPor (Table 2, entry 3). These values were much less than those obtained in the presence of CoPor and linoleic acid (Table 2, entry 1). The effects of reaction factors, such as the catalyst, amount of linoleic acid, and reaction temperature, on epoxidation of trans-stilbene were also investigated. Compared to FePor and MnPor, CoPor was found the most effective catalyst for aerobic epoxidation (Table 2, entries 1, 4, and 5). A low catalyst concentration was also found effective (95%), but poor selectivity toward epoxide formation was noticed (35%) (Table 2, entry 6). The decrease in linoleic acid concentration to 1.0 mmol resulted in 93% conversion rate and moderate selectivity (66%) (Table 2, entry 7). On the other hand, decrease in reaction temperature showed no significant effect on conversion but could reduce selectivity of epoxide (Table 2, entry 8).

Encouraged by the excellent catalytic performances of the synergistic catalytic system (CoPor/linoleic acid) in epoxidation of trans-stilbene, the application scopes of this system were explored. Aromatic trans-β-methyl styrene showed a conversion rate of 99% and selectivity of 81% to corresponding epoxide (Table 2, entry 9). Both alicyclic alkenes like cyclooctene and norbornene were also catalytically epoxidized with superior conversion rates and excellent selectivities toward corresponding epoxides (Table 2, entries 10 and 11). Furthermore, acceptable conversion rate and good selectivity of corresponding epoxide were obtained over a terminal alkene (1-decene) due to difficult epoxidation (Table 2, entry 12). For comparison, the aerobic epoxidations of the above substrates catalyzed by CoPor in the absence of linoleic acid were also investigated, and the data are gathered in Table S1. No epoxide was obtained, indicating that allylic positions in these substrates were not active sites for epoxidation reactions.

3.3. Biomimetic Kinetic Studies

To gain better insights into the distribution of reactants and products as a function of reaction time, the kinetic profiles in one-pot epoxidation of trans-stilbene catalyzed by CoPor/linoleic acid were investigated. As shown in Figure 1, the content of trans-stilbene (1a) quickly decreased and almost vanished after 12 h. Meanwhile, it was interesting to note that the content of trans-stilbene epoxide (1b) rapidly increased within the first 6 h and then reached a plateau. Meanwhile, the content of benzaldehyde (1c) comparatively increased within 4 h and then remained stable as time further rose. The response of catalytic activity was also evaluated by calculating the apparent activation energy (Ea) (Figure S5), and the value of Ea was estimated to be 51 kJ/mol.

Figure 1.

Kinetic profiles of trans-stilbene (1a) consumption, trans-stilbene epoxide (1b), and benzaldehyde (1c) formation by CoPor/linoleic acid. Reaction conditions: trans-stilbene (0.5 mmol), linoleic acid (2.5 mmol), CoPor (0.8 mol %), biphenyl (0.5 mmol) as an internal standard, acetonitrile (5 mL), 80 °C, and O2 (10 mL/min).

The steady-state kinetic model of the catalytic system was subsequently evaluated by the Lineweaver–Burk plot. The reaction rate (v) was determined through decreasing concentration of trans-stilbene ([S]) (Figure S6). As shown in Figure 2, a good linear relationship (R2 = 0.992) was obtained for 1/v versus 1/[S], suggesting that the catalytic system followed an enzyme-like kinetics.

Figure 2.

Steady-state kinetics of one-pot epoxidation of trans-stilbene catalyzed by CoPor/linoleic acid using the Lineweaver–Burk plot.

The corresponding maximum rate (vmax) and Michaelis constant (Km) values were calculated by means of the Michaelis–Menten equation:35

where v and [S] represent the initial velocity and initial concentration of trans-stilbene, respectively. According to enzyme kinetics, Km stands for the substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half of vmax. This represents the affinity of the enzyme to substrate molecules, where a low Km value signifies high affinity of the enzyme.

vmax and Km were estimated to be 4.6 mM min–1 and 1.0 M, respectively. Subsequently, the catalytic constant (Kcat) was calculated to be 0.38 s–1 using the equation Kcat = vmax/E0, where E0 is the initial concentration of CoPor. Compared to reported values of Km (∼300 μM), vmax (∼100 μM s–1), and Kcat (∼300 s–1) of cytochrome P450,36 the Km and vmax values obtained in this study looked much higher, while Kcat was much lower. This would be induced by the moderate catalytic activity of CoPor when compared to that of cytochrome P450.

On the other hand, vmax and Kcat values in this study were close to values (Vmax = 4.7 mM min–1 and Kcat = 0.39 s–1) reported in our one-pot aerobic oxidation of diphenylmethane catalyzed by MnPor/cumene,37 while the Km value in this study was significantly different from the reported Km (0.56 M). The latter was ascribed to differences in metal centers (Mn and Co) of porphyrin and substrates (diphenylmethane and trans-stilbene). In brief, the reaction of one-pot epoxidation of trans-stilbene over CoPor/linoleic acid followed an enzyme-like kinetics, and the Km value depended on both the catalyst and substrate.

3.4. Mechanisms Consideration

A series of control experiments were conducted to distinguish the active sites of linoleic acid and active intermediates of the catalytic system. The epoxidation did not proceed in the presence of stearic acid (Table 3, entry 1). Using linoleic acid methyl ester instead of stearic acid, the conversion rate of trans-stilbene and selectivity toward epoxide formation were determined as 99 and 89%, respectively (Table 3, entry 2). These values were comparable to those obtained with linoleic acid (Table 2, entry 1), suggesting that allylic C–H bonds were the active sites of linoleic acid. Note that the initial active site is located on the bisallylic position of linoleic acid due to its lowest BDE, where the C–H bond may initially break.

Table 3. Control Experiments of trans-Stilbene Epoxidationa.

Reaction conditions: trans-stilbene (0.5 mmol), co-substrate (2.5 mmol), CoPor (0.8 mol %), 80 °C, biphenyl (0.5 mmol) as an internal standard, acetonitrile (5 mL), O2 (10 mL/min), and 12 h. n.d.: not determined.

Determined by GC.

N2 atmosphere without CoPor.

N2 atmosphere with CoPor.

In the absence of CoPor.

The active intermediates involved in the catalytic system were then studied. No product was obtained in the presence of benzaldehyde (Table 3, entry 3), indicating that benzaldehyde generated from oxidation of trans-stilbene did not participate in the conversion of trans-stilbene. In situ formed hydroperoxides are generally considered as oxidants in one-pot aerobic oxidation of organic compounds.15,38 Therefore, epoxidation of trans-stilbene was implemented under a N2 atmosphere using synthetic LAOOH as an oxidant. With or without CoPor, the epoxidation did not proceed (Table 3, entries 4 and 5), suggesting that LAOOH could not be an epoxidizing agent. Some fatty aldehydes like n-hexanal, 2-heptenal and trans,trans-2,4-decadien-1-al were generated in the absence or presence of CoPor (Figure S7). These results indicated that intermediate LAOOH species were thermodynamically unstable and readily decompose into fatty aldehydes. This could explain the inactivity of LAOOH in epoxidation of trans-stilbene under a N2 atmosphere.

Accordingly, in situ formed fatty aldehydes from LAOOH decomposition could likely be the active species for epoxidation. As depicted in Figure S4, n-hexanal and 9-oxononanoic acid were the main fatty aldehydes issued during epoxidation of trans-stilbene catalyzed by CoPor/linoleic acid. Hence, n-hexanal and 9-oxononanoic acid were added to the reaction as co-substrates. In the presence of linoleic acid and CoPor, the conversion rate reached 99%, and selectivity toward epoxide formation was no less than 94%, which were comparative with the results in the absence of CoPor (Table 3, entry 6 vs 8 and entry 7 vs 9). This clearly demonstrated that the in situ generated fatty aldehydes as active species could drive the epoxidation of trans-stilbene under high temperatures even if there is no catalyst. Therefore, catalyst CoPor is mainly responsible for the transformation of linoleic acid into fatty aldehydes.

To gain a better understanding of how fatty aldehydes were generated, the specific structure of in situ formed LAOOH from oxidation of linoleic acid was further analyzed. Due to instability and complexity of LAOOH, conventional analytical tools like GC-MS and ultraviolet absorption are very difficult to use for comprehensive analyses. Soft ionization techniques, such as electrospray ionization, were recently employed for lipid oxidation products analysis due to their relevant sensitivities and specificities.39,40 Therefore, the reaction mixture of linoleic acid oxidation was measured by both ESI-MS and ESI-MS-MS to verify the specific structures of LAOOH species.

In the absence of CoPor (Figure 3A), the MS spectra showed the presence of reactant linoleic acid (m/z = 279) and the formation of LAOOH (m/z = 311), with an elevated relative abundance of LAOOH. Except LAOOH, the ion with m/z = 295 was assigned to hydroxy derivatives of linoleic acid (LAOH),41 while that with m/z = 293 could be associated with the dehydrated ion from LAOOH or derivatives of linoleic acids, such as epoxy and ketone.42,43 In the presence of CoPor, the MS spectra displayed an evident decrease in relative abundance of LAOOH (m/z = 311) and an increase in relative abundance of LAOH (m/z = 295) (Figure 3B). These results suggested the probable decomposition of LAOOH into LAOH in the presence of CoPor.

Figure 3.

ESI-MS spectra (negative mode) of the reaction mixture of linoleic acid oxidation in the (A) absence or (B) presence of CoPor. Reaction conditions: linoleic acid (2.5 mmol), CoPor (0.004 mmol), 80 °C, acetonitrile (5 mL), O2 (10 mL/min), and 12 h.

The ESI-MS-MS spectra of LAOOH (m/z = 311) were then performed to unambiguously distinguish the isomers of LAOOH. Without CoPor (Figure 4A), the ESI-MS-MS spectra of the ion with m/z = 311 revealed ion fragments with m/z = 185 and 195, related to C9-linoleic acid hydroperoxide (9-LAOOH) and C13-linoleic acid hydroperoxide (13-LAOOH),44−46 respectively. Other ion fragments were also obtained at m/z 171, 183, 197, 211, and 223, derived from cleavage of C9–C10, C10–C11, C11–C12, C12–C13, and C13–C14 bonds, respectively. These ion fragments indicated the presence of 9-, 10-, 11-, 12-, and 13-LAOOH,46 respectively. Due to a high relative abundance of 9-LAOOH (m/z = 171) and13-LAOOH (m/z = 223), thus 9-LAOOH and 13-LAOOH were the predominant LAOOH species in the absence of CoPor.

Figure 4.

ESI-MS-MS spectra (negative mode) of ion with m/z 311 observed in ESI-MS spectra of reaction mixtures of linoleic acid oxidation in the (A) absence or (B) presence of CoPor.

By adding CoPor (Figure 4B), the ESI-MS-MS spectra of the ion with m/z = 311 exhibited the presence of 9-LAOOH (m/z = 171 and 185). The ions with m/z = 183, 197, and 211 stood for the presence of 10-, 11-, and 12-LAOOH, respectively. Compared to profiles obtained in the absence of CoPor, the peaks of ions with m/z = 195 and 223 vanished from the spectra, indicating the absence of 13-LAOOH. This may be ascribed to the easy decomposition of 13-LAOOH in the presence of CoPor. In the epoxidation of trans-stilbene catalyzed by CoPor/linoleic acid, n-hexanal and 9-oxononanoic acid were the dominant fatty aldehydes (Figure S4), which would derive from the decomposition of 13-LAOOH and 9-LAOOH,25,47,48 respectively. These findings further demonstrated that 9-LAOOH and 13-LAOOH were the dominant LAOOH species in the CoPor/linoleic acid catalytic system.

LAOOH is known as the major initial product of free-radical-initiated peroxidation of linoleic acid.39 Accordingly, in situ ESR experiments by DMPO as a free-radical trapping agent were conducted to gain insights into free-radical mechanisms. No signal was observed in the absence of CoPor (Figure S8), suggesting that CoPor played an important role in the aerobic oxidation of linoleic acid. Upon addition of CoPor, a specific signal (black club suit) appeared and was characterized by hyperfine coupling constants (aN = 13.0 G, aH(β) = 10.5 G, and g = 2.0022) (Figure 5A). This agreed well with the spectrum of computer stimulation (Figure S9) and was assigned to the DMPO spin adduct of the linoleic acid-derived alkylperoxyl radical (LAOO·).49 This suggested that LAOO· was the dominant radical species formed during the initial stage of linoleic acid oxidation.

Figure 5.

ESR spectra of linoleic acid (0.5 M) oxidation in the (A) presence or (B) absence of O2 at DMPO (100 mM), CoPor (0.8 mM), and 80 °C. ESI-MS spectra (positive mode) of TEMPO adducts in the (C) absence or (D) presence of CoPor (0.004 mmol). Reaction conditions: linoleic acid (2.5 mmol), 80 °C, acetonitrile (5 mL), TEMPO (1.0 mmol), O2 (10 mL/min), and 12 h.

LAOO· is known to derive from the initial linoleic acid-derived alkyl radical (LA·), formed by homolytic cleavage of the C–H bond. Therefore, in situ ESR tests were carried out under a N2 atmosphere to obtain LA· radicals. The signal was hardly detected during the first minute, but the signal (⧫) gradually strengthened after 11 min (Figure 5B). The signal (⧫) characterized by hyperfine coupling constant (aN = 16.2 G, aH(β) = 25 G, and g = 2.0012) and in accordance with that of computer simulation (Figure S10) was assigned to the DMPO adduct of carbon-centered LA·.50 The signal (black spade suit) characterized by a hyperfine coupling constant (aN = 15.1 G) was assigned to the DMPO derivative,51 probably attributed to the presence of trace O2.

The ESI-MS analyses of radical trapping with TEMPO were conducted, and the results are gathered in Figure 5. Without CoPor, ions with m/z 436, 452, and 468 were formed and assigned to TEMPO adducts of LA·, linoleic acid-derived alkoxyl radical (LAO·), and LAOO·, respectively (Figure 5C). Among these ions, the LAOO· adduct (m/z = 468) agreed well with ESR spectral data (Figure 5A). This indicated its strong relative abundance and LAOOH as the major intermediate, in accordance with ESI-MS spectra obtained without CoPor (Figure 3A).

In the presence of CoPor, the same ions at m/z = 436, 452, and 468 were also generated, but the relative abundance of LAOO• adduct (m/z = 468) obviously decreased, and that of LAO· adduct (m/z = 452) increased (Figure 5D). Hence, LAOOH would readily be decomposed by CoPor into LAO· through O–O bond homolytic cleavage.52,53 With respect to the strongest relative abundance of LAOH in the presence of CoPor (Figure 3B), LAOOH probably converted into LAOH via LAO· through H-abstraction. In addition, LAO· would likely to be converted into the corresponding fatty aldehyde through homolytic β-scission.54−56

Based on the above discussion, a plausible mechanism of trans-stilbene epoxidation mediated by CoPor/linoleic acid was proposed (Scheme 1). Considering the lowest BDE of the bisallylic C–H bond of linoleic acid, the C–H bond on C11 would first undergo dehydrogenation to provide an alkyl radical (LA·, a), delocalized over five carbons from C-9 to C-13.57 LA· tended to delocalize its unpaired electron over either position C13 or C9, forming 13-LA· or 9-LA·. The subsequent oxygen insertion at corresponding positions resulted in the formation of 13-LAOO· and 9-LAOO· (b) followed by H-abstraction to yield two main hydroperoxides (13-LAOOH and 9-LAOOH, c). Even in the presence of CoPor, both hydroperoxides hardly induced epoxidation of trans-stilbene into epoxide (Table 3, entry 5).

Scheme 1. Plausible Mechanism Involved in One-Pot Epoxidation of trans-Stilbene Catalyzed by CoPor/Linoleic Acid.

a, b, and d were verified by ESR spectra and ESI-MS spectra with TEMPO as the trapping agent. c was verified by ESI-MS and ESI-MS-MS. e and f were verified by GC-MS.

Inversely, the hydroperoxides were decomposed into fatty aldehydes (n-hexanal (A) and 9-oxononanoic acid (B), e) in the absence of CoPor through thermic decomposition,47 accounting for 22% conversion rate of trans-stilbene in blank of the CoPor experiment (Table 2, entry 3). In the presence of CoPor, the decomposition of hydroperoxides into alkoxyl radicals (13-LAO· and 9-LAO·, d) was facilitated through O–O homolytic cleavage. At the same time, Co(II)Por was converted into the cobalt hydroxide complex (Co(III)Por-OH), which was inactive for the epoxidation of trans-stilbene.58 Co(III)Por-OH further reacted with in situ generated peracid (h), thus achieving regeneration of the catalyst Co(II)Por along with the formation of acylperoxyl radicals (g).58 Then, alkoxyl radicals (d) were converted into A and B through homolytic β-scission. Finally, fatty aldehydes (A and B) could efficiently achieve epoxidation of trans-stilbene through Mukaiyama mechanism in the presence of O2 and a high temperature, as described below (e → j). C–H bonds on acyl groups of fatty aldehydes broke at a high temperature to afford acyl radical (f), which were then inserted by O2 to generate acylperoxyl radicals (g). On the one hand, acylperoxyl radicals (g) could directly epoxidize trans-stilbene to the epoxide along with the formation of carboxyl radicals (i), which could capture an additional hydrogen atom to generate the corresponding acids (n-hexanoic acid (C) and azelaic acid (D), j). On the other hand, acylperoxyl radicals (g) could capture an additional hydrogen atom to generate the peracid (h), which also could directly epoxidize trans-stilbene to the epoxide along with the formation of corresponding acids (n-hexanoic acid (C) and azelaic acid (D), j).

4. Conclusions

An efficient and mild catalytic epoxidation of alkenes catalyzed by cobalt porphyrin in the presence of sunflower seeds oil containing 70 wt % linoleic acid as a co-substrate was successfully performed. Using trans-stilbene as a model substrate, the influences of various reaction parameters, such as the catalyst type, its concentration, and reaction temperature, on both activity and selectivity toward epoxide formation were investigated. Under ambient conditions, the conversion rate of trans-stilbene and selectivity toward epoxide formation were estimated to be 99 and 88%, respectively. A biomimetic kinetic model was established accordingly and revealed that epoxidation of trans-stilbene followed an enzyme-like kinetics. The ESI-MS-MS and in situ ESR studies suggested that linoleic acid was in situ converted to fatty aldehydes via hydroperoxide intermediates. Epoxidation of alkenes was achieved from fatty aldehydes through Mukaiyama mechanism in the presence of dioxygen and CoPor. Overall, the proposed route is green, mild, and sustainable for the development of an alkene epoxidation process.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFA0602900), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 21425627, 21576302, and 21878344), the National Natural Science Foundation of China-SINOPEC Joint Fund (no. U1663220), Guangdong Provincial Key R&D Programme (2019B110206002), and the Local Innovative and Research Teams Project of Guangdong Pearl River Talents Program (2017BT01C102).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.9b03714.

ESI-MS spectrum of LAOOH, GC analysis for oxidation products of cyclohexene, kinetic studies of epoxidation of trans-stilbene over different co-substrates, GC analysis for oxidative cleavage products from linoleic acid, blank control experiments of alkene epoxidation in the absence of linoleic acid, apparent activation energy of trans-stilbene epoxidation, the reaction rate of trans-stilbene epoxidation, GC analysis for decomposition products of LAOOH, and ESR analysis of linoleic acid oxidation (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Shen Y.; Jiang P.; Wai P. T.; Gu Q.; Zhang W. Recent Progress in Application of Molybdenum-Based Catalysts for Epoxidation of Alkenes. Catalysts 2019, 9, 31–57. 10.3390/catal9010031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W.; Sun Q. Bioinspired Manganese and Iron Complexes for Enantioselective Oxidation Reactions: Ligand Design, Catalytic Activity, and Beyond. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 2370–2381. 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nodzewska A.; Wadolowska A.; Watkinson M. Recent advances in the catalytic oxidation of alkene and alkane substrates using immobilized manganese complexes with nitrogen containing ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 382, 181–216. 10.1016/j.ccr.2018.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q.; Liang X.; Bi R.; Liu Y.; He Y.; Feng J.; Li D. Highly efficient CuCr-MMO catalyst for a base-free styrene epoxidation with H2O2 as the oxidant: synergistic effect between Cu and Cr. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 16402–16411. 10.1039/C9DT02357G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Meng R.; Li J.; Jian P.; Wang L.; Jian R. Achieving high-performance for catalytic epoxidation of styrene with uniform magnetically separable CoFe2O4 nanoparticles. Appl. Catal., B 2019, 254, 214–222. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.04.083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Kruijff G. H. M.; Goschler T.; Derwich L.; Beiser N.; Türk O. M.; Waldvogel S. R. Biobased Epoxy Resin by Electrochemical Modification of Tall Oil Fatty Acids. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 10855–10864. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b01714. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Liu S.; Zhao Z.; Su H.; Hao J.; Wang Y. (Salen)Mn(iii)-catalyzed chemoselective acylazidation of olefins. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 6085–6090. 10.1039/C8SC01882K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H.; Ahn H. M.; Jeong H. Y.; Kim C.; Lee D. Non-Heme Iron Catalysts for Olefin Epoxidation: Conformationally Rigid Aryl-Aryl Junction To Support Amine/Imine Multidentate Ligands. Chem.-Eur. J. 2018, 24, 8632–8638. 10.1002/chem.201800447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piera J.; Bäckvall J.-E. Catalytic oxidation of organic substrates by molecular oxygen and hydrogen peroxide by multistep electron transfer-a biomimetic approach. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 3506–3523. 10.1002/anie.200700604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burek B. O.; Bormann S.; Hollmann F.; Bloh J. Z.; Holtmann D. Hydrogen peroxide driven biocatalysis. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 3232–3249. 10.1039/C9GC00633H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holtmann D.; Hollmann F. The oxygen dilemma: a severe challenge for the application of monooxygenases. ChemBioChem 2016, 17, 1391–1398. 10.1002/cbic.201600176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crites C.-O. L.; Hallet-Tapley G. L.; González-Béjar M.; Netto-Ferreira J. C.; Scaiano J. C. Epoxidation of stilbene using supported gold nanoparticles: cumyl peroxyl radical activation at the gold nanoparticle surface. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 2289–2291. 10.1039/c3cc48626e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotti N.; Ravasio N.; Zaccheria F.; Psaro R.; Evangelisti C. Epoxidation of alkenes through oxygen activation over a bifunctional CuO/Al2O3 catalyst. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 1957–1959. 10.1039/c3cc37843h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M.; Shi S.; Zhao L.; Wang M.; Zhu G.; Gao J.; Xu J. Wettability Control of Co-SiO2@Ti-Si Core-Shell Catalyst to Enhance the Oxidation Activity with the In Situ Generated Hydroperoxide. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 14702–14712. 10.1021/acsami.8b19704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotti N.; Ravasio N.; Psaro R.; Evangelisti C.; Dworakowska S.; Bogdal D.; Zaccheria F. Copper mediated epoxidation of high oleic natural oils with a cumene–O2 system. Catal. Commun. 2015, 64, 80–85. 10.1016/j.catcom.2015.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel B. B.; Alsters P. L.; Feiters M. C.; Nolte R. J. M. Mechanistic studies on the Mukaiyama epoxidation. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 3453–3464. 10.1021/jo030345a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi L.; Wang T.; Wei Y.; Tian H. Mechanism of Propylene Epoxidation via O2 with Co-Oxidation of Aldehydes by Metalloporphyrins. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 2018, 6557–6565. 10.1002/ejoc.201801233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malko D.; Guo Y.; Jones P.; Britovsek G.; Kucernak A. Heterogeneous iron containing carbon catalyst (Fe-N/C) for epoxidation with molecular oxygen. J. Catal. 2019, 370, 357–363. 10.1016/j.jcat.2019.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vanoye L.; Wang J.; Pablos M.; de Bellefon C.; Favre-Réguillon A. Epoxidation using molecular oxygen in flow: facts and questions on the mechanism of the Mukaiyama epoxidation. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 4724–4732. 10.1039/C6CY00309E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon E.-Y.; Seo J.-H.; Kang W.-R.; Kim M.-J.; Lee J.-H.; Oh D.-K.; Park J.-B. Simultaneous enzyme/whole-cell biotransformation of plant oils into C9 carboxylic acids. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 7547–7553. 10.1021/acscatal.6b01884. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M.; Ma J.; Liu H.; Luo N.; Zhao Z.; Wang F. Sustainable productions of organic acids and their derivatives from biomass via selective oxidative cleavage of C–C bond. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 2129–2165. 10.1021/acscatal.7b03790. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Villaverde J. J.; Santos S. A. O.; Haarmann T.; Neto C. P.; Simões M. M. Q.; Domingues M. R. M.; Silvestre A. J. D. Cloned Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipoxygenase as efficient approach for the clean conversion of linoleic acid into valuable hydroperoxides. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 231, 519–525. 10.1016/j.cej.2013.07.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson Z. R.; Siebert M. R. Methyl Linoleate and Methyl Oleate Bond Dissociation Energies: Electronic Structure Fishing for Wise Crack Products. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 1779–1787. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.7b02798. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Otte K. B.; Kittelberger J.; Kirtz M.; Nestl B. M.; Hauer B. Whole-Cell One-pot biosynthesis of azelaic acid. ChemCatChem 2014, 6, 1003–1009. 10.1002/cctc.201300787. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Otte K. B.; Kirtz M.; Nestl B. M.; Hauer B. Synthesis of 9-oxononanoic acid, a precursor for biopolymers. ChemSusChem 2013, 6, 2149–2156. 10.1002/cssc.201300183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.-Y.; Jun M.-W.; Seong Y.-J.; Park H.; Ahn J.; Park Y.-C. Direct Biotransformation of Nonanoic Acid and Its Esters to Azelaic Acid by Whole Cell Biocatalyst of Candida tropicalis. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 17958–17966. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b04723. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B.; Zhang H.; An J.; Zhang Y.; Sun L.; Jin Y.; Shi J.; Li M.; Zhang H.; Zhang Z. Sequential Intercellular Delivery Nanosystem for Enhancing ROS-Induced Antitumor Therapy. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 3505–3518. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b00336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühn H.; Wiesner R.; Lankin V. Z.; Nekrasov A.; Alder L.; Schewe T. Analysis of the stereochemistry of lipoxygenase-derived hydroxypolyenoic fatty acids by means of chiral phase high-pressure liquid chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 1987, 160, 24–34. 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90609-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z.; Song J.; Tian R.; Yang Z.; Yu G.; Lin L.; Zhang G.; Fan W.; Zhang F.; Niu G.; Nie L.; Chen X. Activatable singlet oxygen generation from lipid hydroperoxide nanoparticles for cancer therapy. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 6492–6496. 10.1002/anie.201701181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J.; Peng F.; Yu H.; Wang H.; Zheng W. Aerobic liquid-phase oxidation of ethylbenzene to acetophenone catalyzed by carbon nanotubes. ChemCatChem 2013, 5, 1578–1586. 10.1002/cctc.201200603. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y.; Yu H.; Peng F.; Wang H. Selective allylic oxidation of cyclohexene catalyzed by nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 1617–1625. 10.1021/cs500187q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant J. R.; Mayer J. M. Oxidation of C-H bonds by [(bpy)2(py)RuIVO]2+ occurs by hydrogen atom abstraction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 10351–10361. 10.1021/ja035276w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agapito F.; Nunes P. M.; Costa Cabral B. J.; Borges dos Santos R. M.; Martinho Simões J. A. Energetics of the allyl group. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 8770–8779. 10.1021/jo701397r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.; Chen M.; Zhang B.; Nie R.; Huang A.; Goh T. W.; Volkov A.; Zhang Z.; Ren Q.; Huang W. Allylic oxidation of olefins with a manganese-based metal–organic framework. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 3629–3636. 10.1039/C9GC01337G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan H.; Dai S.; Jin B. Bioelectrochemical Reaction Kinetics, Mechanisms, and Pathways of Chlorophenol Degradation in MFC Using Different Microbial Consortia. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 17263–17272. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b04038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse C. J. C.; Bell S. G.; Wong L.-L. P450BM3 (CYP102A1): connecting the dots. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 1218–1260. 10.1039/C1CS15192D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J.; Luo R.; Zhou X.; Wang F.; Ji H. Metalloporphyrin-mediated aerobic oxidation of hydrocarbons in cumene: Co-substrate specificity and mechanistic consideration. Mol. Catal. 2017, 440, 36–42. 10.1016/j.mcat.2017.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M.; Shi S.; Zhao L.; Wang M.; Zhu G.; Zheng X.; Gao J.; Xu J. Effective utilization of in situ generated hydroperoxide by a Co–SiO2@Ti–Si core–shell catalyst in the oxidation reactions. ACS Catal. 2017, 8, 683–691. 10.1021/acscatal.7b03259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz B.; Stiegler V.; Eisenreich W.; Engel K.-H. Strategies for UHPLC-MS/MS-Based Analysis of Different Classes of Acyl Chain Oxidation Products Resulting from Thermo-Oxidation of Sitostanyl Oleate. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 12072–12083. 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b05197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahern K. W.; Serbulea V.; Wingrove C. L.; Palas Z. T.; Leitinger N.; Harris T. E. Regioisomer-independent quantification of fatty acid oxidation products by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis of sodium adducts. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11197–11209. 10.1038/s41598-019-47693-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto S.; Martinez G. R.; Rettori D.; Augusto O.; Medeiros M. H. G.; Di Mascio P. Linoleic acid hydroperoxide reacts with hypochlorous acid, generating peroxyl radical intermediates and singlet molecular oxygen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103, 293–298. 10.1073/pnas.0508170103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villaverde J. J.; Santos S. A. O.; Simões M. M. Q.; Neto C. P.; Domingues M. R. M.; Silvestre A. J. D. Analysis of linoleic acid hydroperoxides generated by biomimetic and enzymatic systems through an integrated methodology. Ind. Crops Prod. 2011, 34, 1474–1481. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2011.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oliw E. H.; Garscha U.; Nilsson T.; Cristea M. Payne rearrangement during analysis of epoxyalcohols of linoleic and alpha-linolenic acids by normal phase liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Biochem. 2006, 354, 111–126. 10.1016/j.ab.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan D. K.; Murphycor R. C. Analysis of lipid hydroperoxides and long-chain conjugated keto acids by negative ion electrospray mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1995, 6, 1190–1201. 10.1016/1044-0305(95)00505-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour C.; Loonis M. Regio- and stereoselective oxidation of linoleic acid bound to serum albumin: identification by ESI-mass spectrometry and NMR of the oxidation products. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2005, 138, 60–68. 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villaverde J. J.; Santos S. A. O.; Maciel E.; Simões M. M. Q.; Neto C. P.; Domingues M. R. M.; Silvestre A. J. D. Formation of oligomeric alkenylperoxides during the oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids: an electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry study. J. Mass Spectrom. 2012, 47, 163–172. 10.1002/jms.2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza P. T.; Ansolin M.; Batista E. A. C.; Meirelles A. J. A.; Tubino M. Kinetic of the formation of short-chain carboxylic acids during the induced oxidation of different lipid samples using ion chromatography. Fuel 2017, 199, 239–247. 10.1016/j.fuel.2017.02.093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C.; Tallman K. A.; Porter N. A.; Brash A. R. Two distinct pathways of formation of 4-hydroxynonenal - Mechanisms of nonenzymatic transformation of the 9-and 13-hydroperoxides of linoleic acid to 4-hydroxyalkenals. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 20831–20838. 10.1074/jbc.M101821200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conte M.; Chechik V. Spin trapping of radical intermediates in gas phase catalysis: cyclohexane oxidation over metal oxides. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 3991–3993. 10.1039/c0cc00157k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Wang Y.; Cao P.; Liu Y. Combination of gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and electron spin resonance spectroscopy for analysis of oxidative stability in soybean oil during deep-frying process. Food Anal. Methods 2018, 11, 1485–1492. 10.1007/s12161-017-1132-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Basumallick L.; Ji J. A.; Naber N.; Wang Y. J. The fate of free radicals in a cellulose based hydrogel: detection by electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 98, 2464–2471. 10.1002/jps.21632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu I.; Morimoto Y.; Velmurugan G.; Gupta T.; Paria S.; Ohta T.; Sugimoto H.; Ogura T.; Comba P.; Itoh S. Characterization and Reactivity of a Tetrahedral Copper(II) Alkylperoxido Complex. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 11157–11165. 10.1002/chem.201902669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y. J.; Hyun M. Y.; Lee J. H.; Lee H. G.; Kim J. H.; Jang S. P.; Noh J. Y.; Kim Y.; Kim S. J.; Lee S. J.; Kim C. Amide-based nonheme cobalt(III) olefin epoxidation catalyst: partition of multiple active oxidants CoV=O, CoIV=O, and CoIII-OO(O)CR. Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 6094–6101. 10.1002/chem.201103916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegeberg C.; Browne W. R.; McKenzie C. J. Catalytic Alkyl Hydroperoxide and Acyl Hydroperoxide Disproportionation by a Nonheme Iron Complex. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 9980–9991. 10.1021/acscatal.8b02882. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dikalov S. I.; Mason R. P. Spin trapping of polyunsaturated patty acid-derived peroxyl radicals: reassignment to alkoxyl radical adducts. Free Radicals Biol. Med. 2001, 30, 187–197. 10.1016/S0891-5849(00)00456-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J.-L.; Wang Z.; Zhang R.; Wang Y.; Wang J. Visible-Light-Promoted Ring-Opening Alkynylation, Alkenylation, and Allylation of Cyclic Hemiacetals through β-Scission of Alkoxy Radicals. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 8992–8995. 10.1002/chem.201901762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z.; Li Y. What is responsible for the initiating chemistry of iron-mediated lipid peroxidation: an update. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 748–766. 10.1021/cr040077w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesterova O. V.; Kopylovich M. N.; Nesterov D. S. Stereoselective oxidation of alkanes with m-CPBA as an oxidant and cobalt complex with isoindole-based ligands as catalysts. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 93756–93767. 10.1039/C6RA14382B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.