Abstract

Microwave–ultrasound-assisted facile synthesis of a dumbbell- and flower-shaped potato starch phosphate (PSP) polymer, hereafter PSP, was carried out by cross-linking the hydroxyl groups of native potato starch (NPS) using phosphoryl chloride as a cross-linking agent. Structural and morphological analysis manifested the successful formation of the dumbbell- and flower-shaped PSP biosorbent with enhanced specific surface area and thermal stability. Viscoelastic behavior of NPS and PSP suggested increased rigidity in PSP, which helped the material to store more deformation energy in an elastic manner. The synthesized PSP biosorbent material was successfully tested for efficient and quick uptake of Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) ions from aqueous medium under competitive and noncompetitive batch conditions with qm values of 130.54, 106.25, 91.84, and 51.38 mg g–1, respectively. The adsorption selectivity was in consonance with Pearson’s hard and soft acids and bases (HSAB) theory in addition to their order of hydrated radius. Adsorption of Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) followed a second-order kinetics and the adsorption data fitted well with the Langmuir isotherm model. Quantum computations using density functional theory (DFT) further supported the experimental adsorption selectivity, Zn(II) > Pb(II) > Cd(II) > Hg(II), in terms of metal–oxygen binding energy measurements. What was more intriguing about PSP was its reusability over multiple adsorption cycles by treating the metal(II)-complexed PSP with 0.1 M HCl without any appreciable loss of its adsorption capacity.

1. Introduction

We will begin with a quote of W.H. Auden, a British poet who once said “Thousands have lived without love, not one without water” speaking the ultimate importance of water. Our water bodies are under tremendous pollution stress through anthropogenic agents and unregulated human interference. Currently, large quantities of water containing heavy metals are being discharged into water streams as a result of various industrial, agricultural, and human activities. Arsenic, cadmium, lead, copper, mercury, nickel, chromium, zinc, etc. are some of the heavy metals most commonly found in wastewater. Unlike organic contaminants, heavy metals persist in aquatic systems due to their higher solubility and nonbiodegradable nature.1,2 Consumption of heavy-metal-contaminated water is jeopardizing our state of well-being and kills more people than a war or any other form of brutality. Still, we are not hopeless against the ever-increasing threats to clean water.

A number of physicochemical treatment methods have been used for heavy metal removal, such as chemical precipitation,3 ultrafiltration,4 ion exchange,5−7 and adsorption.8−10 Among the various technologies developed over the years for safe disposal of heavy metals, adsorption holds great promise and represents an alternative treatment method due to its simplicity, high adsorption capacity and selectivity, low cost, and minimal sludge generation.11−14 Materials with a layered-type structure, such as layered metal sulfides (LMS),15 metal(IV) phosphates,16 and layered double hydroxides (LDHs),17,18 offer a unique strategy for the effective capture of heavy metal ions. LDHs are a class of two-dimensional layered materials containing an exchangeable and charge-neutralizing interlayer anion.19 For decades, composites of LDHs are known, which offer superior advantages such as thermal stability and high adsorption capacity for the decontamination of heavy metals. Dinari et al. reported a number of LDH-based composite adsorbent materials for the quick removal of Cd(II) ions.17,18 In spite of the abundant uses of commercially available adsorbents, such as porous silica,20 activated carbon,21 layered zirconium phosphate,16 etc., their application is somewhat restricted, mainly due to their low selectivity and high cost. The biosorption method has received much attention toward removal of heavy metals and is presently serving as an alternative treatment technology, mainly due to its low cost, metal selectivity, sustainability, nontoxicity, and high adsorption efficiency.22,23 For this purpose, a number of biosorbents have been tested and approved for the removal of toxic metals from contaminated water, and among them, starch, alginate, and chitosan display outstanding adsorption performance.24−27 Demey et al. recently reported a number of research works on biosorption and are actively engaged in the removal of heavy metals from aqueous systems.28−31 For example, in their recently reported research work, alginate- and chitosan-based biosorbents were shown to exhibit superior sorption capacity for Pb(II), Ni(II), and Hg(II) ions.28,29 The same research group in 2019 reported sorption of terbium (a rare earth ion) in addition to Pb(II) ions by a low-cost torrefied poplar-biomass-based sorbent and the sorption results demonstrated better adsorption capacity.30

Starch is the most abundant polysaccharide in nature with a number of hydroxyl groups at its surface. Starch has excellent properties, such as biodegradability, biocompatibility, and nontoxicity; therefore, it finds use in drug delivery, tissue engineering, adsorption, and others.32 Despite these applications, use of native starch is somewhat restricted because of its low adsorption performance and its tendency to retrograde.33 To overcome these challenges, native starch is modified by numerous chemical strategies, such as cross-linking, grafting, oxidation, esterification, and etherification. Chemical modification introduces new functionalities in starch, such as carbonyl, acetyl, hydroxypropyl, and phosphate.32,33 Among these chemical modifications, cross-linking serves as an efficient and most common strategy. Among diverse cross-linking agents, such as sodium tripolyphosphate (STPP), sodium trimetaphosphate (STMP), epichlorohydrin (EPI), a mixture of adipic and acetic anhydrides, a mixture of succinic anhydride and vinyl acetate, and phosphorus oxychloride (POCl3), cross-linking with POCl3 involves esterification of surface hydroxyls resulting in anionic starch phosphate esters.26,34−36 POCl3 is an efficient and fast-acting cross-linking agent, which gives rise to starch phosphate at high pH values of ca. 10–11.32,33 Starch phosphate esters possess high viscosity and good adhesive properties with enhanced metal-binding affinity over diverse pH regimes. Cross-linking of native starch to improve the performance involves homogeneous mixing of starch with cross-linking agents to permeate the internal structure of starch. However, this homogeneous mixing of starch with chemical reagents is difficult; therefore, more highly efficient methods, such as ultrasound and microwave technology, have recently shown great potential.37 Microwaves are a type of electromagnetic wave with great potential to heat only reactants, thus improving the contact between native starch and the reagent.

Therefore, this study mainly focuses on the adsorption of Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) ions onto PSP. The effect of parameters, such as contact time, solution pH, adsorbent dose, and temperature, was studied to estimate various thermodynamic and kinetic parameters. The metal ion selectivity and sorption mechanism were also ascertained using experimental and DFT studies.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization

The dumbbell- and flower-shaped PSP was synthesized by cross-linking NPS by phosphoryl chloride under alkaline conditions with microwave and ultrasonic irradiation, as shown in Scheme 1. Under alkaline conditions, POCl3 undergoes hydrolysis to phosphoric acid, which then reacts with starch molecules to develop a phosphate ester. Achmatowicz et al. have investigated the hydrolytic conversion of POCl3 to H3PO4.38 Indeed, following the fast initial chloride substitution in POCl3 (K1 = 66 s–1), the remaining two P–Cl bonds are rendered somewhat kinetically less reactive (K2 = 3 × 10–3 s–1) and thermodynamically less stable leading to the accumulation of phosphorodichloridic acid (POH·Cl2). However, the undesired accumulation of POH·Cl2 can be minimized either by increasing the water concentration or by an increase in pH. The increase in pH shows a more pronounced effect; therefore, we have selected pH = 11 for the successful cross-linking of NPS granules.

Scheme 1. Schematic Representation of Chemical Modification/Phosphodiester Bond Formation in NPS by Its cross-linking Reaction with Fast-Acting POCl3 under Ultrasonic and Microwave Irradiation at Alkaline pH.

The cross-linking of starch to form starch phosphate involves reactions between C2 and C2/C3, between C6 and C6, or between C6 and C2/C3 of the sugar ring.37 These interaction possibilities along with the structure of starch are shown in Figure 1. We have shown cross-linking exclusively between C6 and C6 of sugar chains because the C6 position seems to be sterically less crowded and electronically rich enough to facilitate nucleophilic substitution around the phosphorus center of the cross-linking agent.39

Figure 1.

Structure of starch representing various possibilities of phosphodiester cross-linking along with possible interaction sites.

In view of the above facts and hydrolysis pattern of phosphoryl chloride, we propose two mechanistic possibilities for the formation of the phosphodiester linkage between two 6CH2OH groups of starch chains: (a) initially, two consecutive nucleophilic substitution reactions occur by 6CH2OH at the phosphorus center of phosphorodichloridic acid, as shown in Figure S1b. After the reaction has occurred, phosphorodichloridic acid starts to hydrolyze to H3PO4 under alkaline pH. The same two-stage substitution reaction occurs at the electrophilic phosphorus center of H3PO4, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Illustration of phosphodiester bond formation by two consecutive nucleophilic addition–elimination-type reactions between orthophosphoric acid and electronically rich 6CH2OH groups of native potato starch.

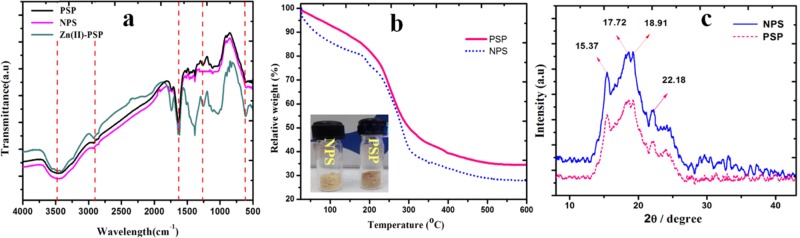

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopic analysis is carried out for native starch, and cross-linked starch before and after adsorption of Zn(II) ions to prove the chemical structure and to confirm metal chelation. Figure 3a presents the FTIR spectra of NPS, PSP, and Zn(II)-complexed PSP. All of these materials exhibited a similar pattern with additional bands arising from cross-linking and zinc metal complexation. The IR bands recorded at 3476, 2922, and 1631 cm–1 were assigned to stretching of the O–H group, stretching of the CH2 group, and O–H–O bending mode, respectively. These three bands represent the characteristic bands of starch. In general, vibration bands arising due to the presence of P=O and C–O–P bonds appear at 1300–1150 cm–1 and 1050–970 cm–1, respectively.40 Consequently, in PSP and Zn(II)-complexed PSP, we have recorded these two bands at 1266 and 1037 cm–1. In the case of Zn(II)-complexed PSP, we recorded a weak band at 608 cm–1, which mainly arises due to the presence of Zn–O bonds. Similar results were obtained from DFT studies, as shown in Figure S2. Therefore, we conclude that IR studies provide some outlook about the incorporation of the phosphodiester linkage and complexation of Zn(II) ions with PSP. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) is used to investigate the thermal stability and decomposition pattern of NPS and PSP up to a temperature of 600 °C under an air atmosphere. The results of TGA are shown in Figure 3b. TGA curves of NPS and PSP generally display a well-defined two-step weight loss pattern. The first weight loss could be assigned to the loss of adsorbed water molecules, which continued up to 180 and 215 °C for native starch and cross-linked starch, respectively. The maximum thermal degradation temperature (Tmax) for native starch and PSP is 305 and 327 °C, respectively. In both NPS and PSP, weight loss continued up to 520 °C and could be assigned to the dehydration reaction between the hydroxyl groups present in starch and cross-linked starch. As is evident from Figure 3b, the second weight loss in native starch started at 180 °C, whereas the initial weight loss temperature for PSP is 215 °C. Moreover, the remaining weight of PSP is 34.38 wt % at 600 °C, which is higher than that of NPS (28.74). Therefore, TGA results indicated better thermal stability of cross-linked starch, which could mainly be attributed to stronger structures in the case of PSP.

Figure 3.

(a) FTIR spectra presenting the principal functional groups in NPS, PSP, and Zn-complexed PSP, (b) thermogravimetric analysis of NPS and PSP, indicating early decomposition of NPS than PSP, (c) X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis of NPS and PSP, indicative of A-type starch.

The X-ray diffraction patterns of NPS and PSP powder samples are presented in Figure 3c, and the results indicate the presence of characteristic diffraction peaks for both the samples recorded at 2θ values of 15.37 and 22.18° along with a weak doublet at 17.72 and 18.91°.41 As inferred from Figure 3c, there is no significant change in the diffractograms of the two samples; however, the results suggest only a decrease in peak intensity after cross-linking the potato starch. Briefly from XRD spectra, starches can be classified as A, B, and C types.42 A-type starch has strong diffraction peaks at about 15 and 23° and an unresolved doublet at around 17 and 18°. B-type starch gives characteristic peak at 5.6° and a strong diffraction peak at 17.7° along with a few less intense peaks at 15, 20, 22, and 24°. C-type starch is a mixture of both A- and B-type polymorphs. Based on the above classification, Figure 3c demonstrates A-type crystal patterns for NPS as well as PSP. Similar results have been reported by Bahrami et al.41 and Lopez-Rubio et al.43

To investigate the morphology of the synthesized samples, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of NPS, PSP, and Zn(II)-complexed PSP were recorded, as shown in Figure 4. The surface of native starch in Figure 4A was found to be nearly globular in shape with a smooth surface and well-defined edges. However, SEM images of the cross-linked starch polymer display dumbbell- and flower-shaped morphologies, with the loss of their original smoothness and structural integrity, as depicted in Figure 4B–E. Some of the dumbbell-like particles agglomerate via further cross-linking and/or intermolecular hydrogen bonding to develop into a flower-shaped morphology, as depicted in Figure 4C. Upon a careful inspection of SEM micrographs of PSP, one can see the presence of cavities or pores in the material. Such visible pore characteristics of PSP may result from alkaline action on starch granules, as has been reported earlier. After a careful investigation of the surface morphology of zinc-complexed PSP over a selected area, the SEM micrographs depict a change in the morphology, indicating more surface roughness due to adsorption of zinc ions (Figure 4F,G). We have also carried out energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) mapping of a Zn-ion-complexed PSP sample, and the results (shown in Figure 4H–K) indicate uniform distribution of Zn ions over the surface of PSP. Furthermore, from the EDX spectrum (Figure 5L) of Zn-complexed PSP, it could be inferred that the material is composed of only C, O, P, and Zn ions.

Figure 4.

SEM micrographs of NPS (A), PSP with rough, dumbbell- and flower-shaped morphology (B, C), PSP showing the presence of pores and cavities on the surface (D, E), and magnified SEM micrograph over a selected area, showing the adsorption of zinc ions (F,G). EDX mapping of Zn-complexed PSP (H–K) and EDX spectrum of Zn-complexed PSP, signifying a high percentage of adsorbed zinc ions (L).

Figure 5.

Plots depicting flow and viscoelastic characteristics of NPS and PSP gels. (a) Viscosity as a function of shear rate, (b) shear stress as a function of shear rate, and (c) storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) as a function of angular frequency. (d) Picture describing lower swelling of PSP in comparison to NPS.

2.2. Viscoelastic properties

Starch is a granular material and swells in an aqueous system in which a gelatinization granule acts as a microgel. During the process of gelatinization, a part of starch goes into the solution.44 Cross-linking serves to suppress the dissolution/disintegration of starch, thereby enhancing the granular nature of the gelatinized starch suspension. Because of this, the rigidity modulus of the PSP gel increases upon cross-linking and, at the same time, the swelling capacity of the polymer decreases.45 It is well established that at a higher starch concentration the swelling will be lower, the suspension viscosity will be higher, and the overall process will be governed by particle rigidity.46,47 Reduced swelling and higher viscosity in the case of PSP are indicative of the fact that POCl3-treated granules have a more rigid external surface with hard crusts formed on the outer surface of the granules.48 The same can also be inferred from the SEM images (Figure 4). It has been well established that in the case of POCl3-treated starch, the decrease in swelling with increased POCl3 concentration is larger in comparison to sodium trimetaphosphate (STMP)- and epichlorohydrin (EPI)-treated starch.36 In general, hard spheres generate higher viscosities because upon applying shear, the granules exude less water and, hence, more will be the resistance to flow.49 Similar results are obtained in the case of PSP. The results of steady shear viscosity and shear stress as a function of shear rate for NPS and PSP are shown in Figure 5a,b. It is evident that at a lower shear rate, the solution shows non-Newtonian behavior, where the viscosity depends strongly on the shear rate, thereby suggesting the presence of agglomerates for both NPS and PSP gels. Additionally, in the case of PSP, zero shear viscosity is higher in comparison to NPS, which also suggests the cross-linking of PSP. Also for PSP, the non-Newtonian behavior is zero for higher shear rates as well.

Oscillatory shear measurements were performed for the study of viscoelastic behavior along with microstructural analysis of the NPS and PSP dispersions at room temperature. Typical results of storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) as a function of angular frequency (ω) can be seen in Figure 5c. The storage modulus is an indication of a hydrogel’s ability to store deformation energy in an elastic manner. This is directly related to the extent of cross-linking. The higher the degree of cross-linking, the lower will be the swelling and, consequently, the higher will be the storage modulus. The binding state of a microstructure is indicative of intermolecular or intraparticle forces within the bulk material. To break the microstructure, one needs to apply a force greater than the force holding the particles within the polymer matrix. When the applied force is smaller than the intraparticle forces, G′ > G″, the material has some capacity to store the deformation energy in an elastic manner. Conversely, when the applied force is higher than the intraparticle forces (G′ < G″), the microstructure collapses; therefore, the mechanical energy supplied to the material disappears and the material attains a characteristic flow. Our results of oscillatory measurements clearly reveal that in the case of PSP as well as in NPS, G′ > G″ at all frequencies from 0 to 100 rad/s, which is indicative of the fact that both the materials possess elastic behavior. Moreover, in the case of PSP, the storage modulus is higher as compared to native NPS over the entire frequency domain, which is again indicative of higher rigidity and lower swelling for PSP. Figure 5d also describes lower swelling in the case of PSP in comparison to NPS. From the rheological measurements, we may conclude that upon successful cross-linking the swelling power decreases and the overall rigidity increases, which helps the material to store more deformation energy in an elastic manner by introducing phosphodiester cross-links between various starch chains.

2.3. Batch Adsorption Studies

Batch adsorption studies were carried out to validate the adsorption performance and selectivity of the PSP biosorbent material for the selective removal of zinc ions. It is very much desirable to carry out surface area and pore size distribution (dV/dW) analysis for any adsorbent material. We, therefore, carried out surface area analysis and pore size distribution (dV/dW) (Figure S3) before optimizing and calculating various batch experimental parameters for the adsorption of heavy metals on PSP. The specific surface area calculated for NPS and PSP was found to be 4.7 and 14.5 m2g–1, respectively. These results clearly indicate that upon cross-linking there is a nearly 3-fold increase in specific surface area in the case of PSP. This increase in specific surface area arises mainly due to the presence of pores and cavities, as a consequence of alkali treatment under microwave irradiation and subsequent cross-linking.50 In addition to the relatively higher specific surface area, PSP also contains large macropores (pore size >50 nm) to allow the metal cations to get adsorbed and diffuse effectively into the pores of PSP. This study suggests that PSP can act as a suitable candidate for adsorption processes similar to other starch-based adsorbent materials.

2.3.1. Effect of Adsorbent Dose and Initial pH Value

Adsorbent dose influences the adsorption capacity and, in general, an increased adsorbent dose increases the adsorption capacity due to the presence of more adsorption sites. Figure S4 displays the relationship between adsorption capacity and PSP dose, and from Figure S4, we have selected 25 mg as an optimum dose for our batch adsorption studies. In addition to adsorbent dose, pH of the solution has a profound effect on the removal of metal cations as it affects the speciation of metal ions in the solution and the chemical state of binding sites on the adsorbent, which eventually affects their affinity for target metal ions. The effects of solution pH on the adsorption capacity of PSP were investigated at pH values from 2 to 9 using a Britton–Robinson universal buffer system, and the results are presented in Figure 6a.The results clearly revealed that the interaction of the PSP biosorbent with Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) ions was strongly pH-dependent. Higher pH values were not tested for metal ion uptake to avoid the formation of metal hydroxides. At low solution pH, protonation of hydroxyl and phosphate groups occurred, making the surface of PSP positively charged, as inferred from the ζ-potential values shown in Figure 6b. Consequently, a lower adsorption capacity was observed at a lower pH due to electrostatic repulsion between PSP and target metal ions along with a competition between H+ ions and target metal ions toward PSP. To arrive at the charge state of the PSP biosorbent as a function of pH, the point of zero charge (pHzpc) was used. Above pHzpc, the surface of the adsorbent is negatively charged and favors adsorption of metal cations. In this study, pHzpc obtained for PSP is 4.2 and the maximum adsorption capacity was established at pH 7.0. Avoiding hydroxide precipitation, we selected pH 6.5 as an optimum batch condition for the adsorption process.

Figure 6.

(a) Effect of pH on the adsorption capacity of Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) ions by the PSP biosorbent, indicating a pH of 6.5 as an optimum pH for batch experiments. (b) Plot depicting the ζ-potential as a function of pH for NPS and PSP, confirming a more negative surface in PSP for efficient metal uptake. Batch conditions: contact time: 3 h; temperature: 298 K; initial metal concentration: 100 mg/L; adsorbent dose: 25 mg; solution volume: 40 mL.

2.3.2. Effect of Initial Metal Concentration and the Langmuir Isotherm

In Figure S5, we present the effect of initial metal concentration on the adsorption capacity of Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) by the PSP biosorbent. It is evident that with an increase in metal ion concentration the adsorption capacity initially increases rapidly and then remains almost constant till a metal ion concentration of 100 mg/L. Therefore, we selected 100 mg/L as the optimum metal concentration for carrying out the isotherm and all other batch experimental studies at 298 K. An adsorption isotherm expresses the relationship between the adsorption capacity (qe, mg/g) and equilibrium concentration of an adsorbate (Ce, mg/L). A typical adsorption isotherm for Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) adsorption onto the PSP biosorbent is shown in Figure 7a. The results clearly indicate that the adsorption capacity increases with metal ion concentration up to the point of saturation adsorption. The enhanced adsorption capacity at a high initial metal concentration can be related to two main factors, namely, a high probability of collisions between the metal ion and PSP, and a high diffusion rate of the metal ion into the PSP biosorbent. As a result, the driving force will be increased and the mass transfer resistance will be reduced.51 The higher amount of metal ions adsorbed at the low initial concentration was due to the larger ratio of active sites to total metal ions, and therefore, all metal ions could bind to the active sites of PSP. The actives sites were progressively occupied by the metal ions and led to no great difference in the adsorption rate at a higher metal ion concentration. Adsorption of Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) was dominated by the Langmuir isotherm model; therefore, we analyzed the experimental data using this model. In this model, metal ions were assumed to undergo a monolayer-type coverage on the PSP surface. This model assumes that once an adsorption site is occupied, no further adsorption can occur at the same site. The Langmuir model is expressed as follows

| 1 |

where Ce (mg/L) is the equilibrium concentration; qe (mg/g) is the equilibrium adsorption capacity; qm (mg/g) is the theoretical maximum sorption capacity; and KL (L/mg) is the Langmuir adsorption constant. The values of qm and KL were obtained from the slope and intercept of the linear plots of Ce/qe vs Ce, as shown in Figure 7b, and the calculated parameters are presented in Table 1. The theoretical maximum sorption capacity (qmax) of PSP for Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) at an initial concentration of 100 mg/L is 130.54, 106.25, 91.84, and 51.38 mg/g, respectively. The high correlation coefficients (R2 > 0.99) indicate a good fit with the Langmuir isotherms, suggesting a monolayer adsorption of these metal ions on PSP. Furthermore, the values of KL are in between 0.026 and 0.096, which implies that the adsorption of metal ions onto PSP is favorable. By comparing the qmax values of Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) ions with other adsorbents (Table 2), the results showed that PSP present a reasonably better adsorption capacity.

Figure 7.

(a) Effect of metal ion concentration on the equilibrium adsorption capacity of Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) on PSP. (b) Langmuir adsorption isotherm model for adsorption of Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) on PSP. Batch conditions: contact time: 3 h; temperature: 298 K; pH: 6.5; adsorbent dose: 25 mg; solution volume: 40 mL.

Table 1. Parameters of the Langmuir Model for the Adsorption of Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) on PSPa.

| metal ion | qmax | KL | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zn(II) | 130.54 | 0.096 | 0.998 |

| Pb(II) | 106.25 | 0.048 | 0.995 |

| Cd(II) | 91.84 | 0.034 | 0.993 |

| Hg(II) | 51.38 | 0.026 | 0.991 |

Batch conditions: contact time: 3 h; temperature: 298 K; pH: 6.5; adsorbent dose: 25 mg; solution volume: 40 mL.

Table 2. Comparison of the Maximum Adsorption Capacity of Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) on Various Adsorbents.

| adsorbent | metal ions | qmax (mmol/g) | refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| soy protein | Zn(II) | 3.90 | (9) |

| Cd(II) | 1.07 | ||

| Pb(II) | 1.13 | ||

| carboxyl-modified lignocelluloses – jute fiber | Pb(II) | 0.76 | (52) |

| Cd(II) | 0.79 | ||

| chitosan polyitaconic acid | Cd(II) | 3.60 | (53) |

| Pb(II) | 1.61 | ||

| porous starch-functionalized carbon disulfide | Pb(II) | 0.52 | (54) |

| calcium alginate | Pb(II) | 0.80 | (55) |

| Cd(II) | 0.02 | ||

| Klebsiellasp. 3S1 | Zn(II) | 0.74 | (56) |

| durian peel | Zn(II) | 0.56 | (57) |

| rapeseed waste | Zn(II) | 0.21 | (58) |

| succinylated starch | Zn(II) | 0.20 | (59) |

| Cd(II) | 0.11 | ||

| dibenzo-18-crown-grafted corn starch | Zn(II) | 5.77 | (60) |

| Cd(II) | 3.27 | ||

| amino-functionalized magnetic graphene | Pb(II) | 0.13 | (61) |

| chitosan-coated diatomaceous earth | Zn(II) | 1.95 | (62) |

| cross-linked starch phosphate carbamate cross-linked starch phosphate | Pb(II) | 2.01 | (63) |

| Zn(II) | 2.00 | (64) | |

| ammonium thioglycolate functionalized egg shell membrane | Hg(II) | 0.69 | (65) |

| silica-gel-supported sulfur-capped PAMAM dendrimers | Hg(II) | 1.89 | (66) |

| layered double hydroxide intercalated with the MoS42– ion | Hg(II) | 2.49 | (15) |

| Pb(II) | 1.40 | ||

| thiol-functionalized mesoporous silica-coated magnetite nanoparticles | Hg(II) | 0.05 | (67) |

| magnetite@carbon/dithizone nanocomposite | Hg(II) | 0.14 | (68) |

| chitosan–iron(III) biocomposite beads | Hg(II) | 1.8 | (29) |

| Pb(II) | 0.56 | ||

| potato starch phosphate (PSP) | Zn(II) | 2.00 | this study |

| Pb(II) | 0.51 | this study | |

| Cd(II) | 0.81 | this study | |

| Hg(II) | 0.26 | this study | |

| native starcha | Zn(II) | 0.68 | |

| Pb(II) | 0.13 | ||

| Cd(II) | 0.17 | ||

| Hg(II) | 0.07 |

Batch experiments were carried out under similar conditions for the purpose of comparison.

2.3.3. Effect of Contact Time and Adsorption Kinetics

To investigate the sorption mechanism and potential rate controlling steps, such as mass transport and chemical reaction process, kinetic models have been used to validate the experimental data. These kinetic models include the Lagergren pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order models.69 Our system fits well in the Lagergren pseudo-second-order kinetic model, indicating that the overall rate of adsorption of metal cations onto the PSP biosorbent is dominated by a chemisorption process. The pseudo-second-order kinetic rate equation is described as follows

| 2 |

where qe (mg/g) is the equilibrium adsorption capacity; qt (mg/g) is the adsorption capacity at time t; K2 is the rate constant for the pseudo-second-order kinetic model. The kinetic plots are shown in Figure 8a,b. In Figure 8a, contact time is shown to influence the adsorption of metal cations, and the results clearly illustrate that the adsorption is initially quite fast and reaches an equilibrium within 90 min during which most of the Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) ions are removed. This is attributed to the combined effect of strong chemical affinity between PSP and Zn(II)/Pb(II) and comparatively smaller hydrated radius of Cd(II) ions, which eventually results in fast diffusion of these ions into the matrix of PSP.70 As is evident from Table 3, the pseudo-second-order rate constant (K2) for adsorption of Pb(II) ions was found to be higher (8.4 × 10–3) than that of Zn(II) ions (7.2 × 10–3). This could be explained by considering the relatively smaller hydrated radius of Pb(II) ions as given in Table 3. This smaller hydrated radius facilitates its fast diffusion into the PSP matrix. However, PSP exhibits higher adsorption capacity for a Zn(II) ion in spite of its higher hydrated radius (4.30 Å) and the results could be attributed to entropy reasons as well in terms of the HSAB principle.71 Since Zn(II) ions are extensively hydrated, more structure breaking will result, releasing more hydrated water upon zinc ion complexation to the PSP matrix. This phenomenon is expected to increase the overall entropy and, therefore, the overall thermodynamic feasibility of adsorption. Comparing qe with qe,exp for Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) ions, the qe values obtained by the pseudo-second-order equation are 112.86, 91.74, 77.27, and 48.56 mg/g, respectively, and the values are close to the values obtained by the experiment. In addition to this, the values of R2 for Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) ions shown in Table 3 clearly indicate the best fit of data with the pseudo-second-order model.

Figure 8.

(a) Effect of contact time on the adsorption behavior of Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) on PSP. (b) Plot describing the pseudo-second-order kinetic model for the adsorption of Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) on PSP. Batch conditions: initial metal concentration: 100 mg/L; temperature: 298 K; pH: 6.5; adsorbent dose: 25 mg; solution volume: 40 mL.

Table 3. Parameters of the Pseudo-Second-Order Model for the Adsorption of Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) on PSPa.

| metal ion | ionic radius (Å) | hydrated radius (Å) | qe (cal) (mmol/g) | K2 (g/mg min) | qe (exp) (mmol/g) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn(II) | 0.74 | 4.30 | 1.73 | 7.2 × 10–3 | 1.71 | 0.997 |

| Pb(II) | 1.19 | 4.01 | 0.44 | 8.4 × 10–3 | 0.43 | 0.993 |

| Cd(II) | 0.95 | 4.26 | 0.69 | 6.9 × 10–3 | 0.66 | 0.990 |

| Hg(II) | 1.02 | 4.22 | 0.24 | 7.3 × 10–3 | 0.22 | 0.984 |

Batch conditions: initial metal concentration: 100 mg/L; temperature: 298 K; pH: 6.5; adsorbent dose: 25 mg; solution volume: 40 mL.

2.3.4. Thermodynamic Studies

The overall feasibility of an adsorption process can be evaluated in terms of entropy and free energy change of the adsorption process. We carried out the adsorption of Zn(II), Pb(II), and Cd(II) ions on PSP at different temperatures (293–313 K) to evaluate various thermodynamic parameters (ΔH0, ΔS0, and ΔG0) of the adsorption process. The results of qe as a function of T are shown in Figure 9a, and the results indicate that with an increase in temperature the adsorption capacity also increases, which is indicative of the endergonicity of the overall process. The thermodynamic parameters can be calculated using the following equations

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

where T (K) is the temperature of the solution, R is the gas constant (8.314 JK–1mol–1), and K0 is the equilibrium constant. Linear fitting of ln K0 vs 1/T for the adsorption of Zn(II), Pb(II), and Cd(II) ions on PSP is shown in Figure 9b.The values of ΔH0/R and ΔS0/R were obtained from the slope and intercept of the ln K0 vs 1/T plot, respectively, and the results are shown in Table 4. The positive value of ΔH0 confirmed the endothermic nature of the overall adsorption process and the negative value of ΔG0 indicated that the adsorption process is spontaneously driven.

Figure 9.

(a) Effect of temperature on the adsorption of Zn(II), Pb(II), and Cd(II) ions on the prepared PSP biosorbent. (b) Linear fitting of ln K0 vs 1/T for adsorption of Zn(II), Pb(II), and Cd(II) ions for evaluating ΔH0, ΔS0, and ΔG0 for the adsorption process. Batch conditions: initial metal concentration: 100 mg/L; pH: 6.5; contact time: 90 min; adsorbent dose: 25 mg; solution volume: 40 mL.

Table 4. Thermodynamic Parameters for Adsorption of Zn(II), Pb(II), and Cd(II) Ions on the Prepared PSP Biosorbenta.

| metal ion | T (K) | ΔG0 (kJ/mol) | ΔS0 (kJ(K–1/mol) | ΔH0 (J/mol) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn(II) | 293 | –3.770 | 27.75 | 108.83 | 0.988 |

| 298 | –4.353 | ||||

| 303 | –4.798 | ||||

| 308 | –5.315 | ||||

| 313 | –6.014 | ||||

| Pb(II) | 293 | –1.398 | 19.06 | 70.01 | 0.986 |

| 298 | –1.803 | ||||

| 303 | –2.202 | ||||

| 308 | –2.520 | ||||

| 313 | –2.784 | ||||

| Cd(II) | 293 | –0.842 | 15.29 | 55.24 | 0.981 |

| 298 | –1.198 | ||||

| 303 | –1.489 | ||||

| 308 | –1.679 | ||||

| 313 | –1.979 |

Batch conditions: initial metal concentration: 100 mg/L; pH: 6.5; contact time: 90 min; adsorbent dose: 25 mg; solution volume: 40 mL.

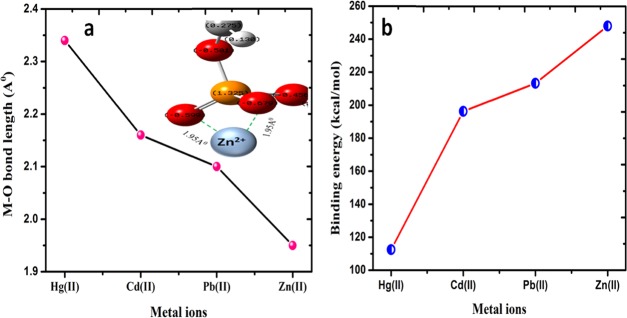

2.4. Density Functional Theory Analysis

To validate the experimental selectivity and to further investigate the chemical interactions between Zn(II), Cd(II), Pb(II), and Hg(II) ions and the PSP biosorbent, DFT calculations were carried out using the Gaussian 03 program.72 To mimic the chemical selectivity, we take a piece of cross-linked starch as our model for computational details. Abundant hydroxyl groups are available for metal ion binding, which includes surface hydroxyls, glycosidic hydroxyls, and phosphate hydroxyls. On the basis of a Mulliken charge analysis (Figure S6), the phosphate oxygen atoms are shown to carry more negative partial charges than either terminal oxygen or glycosidic oxygen, and hence, the phosphate oxygen is expected to be a more favorable site for the adsorption of metal cations. Based on these results, the optimized geometries of the cluster models PSP–M2+ are shown in Figure 10, wherein the cation, M2+ (M = Zn, Pb, Cd, and Hg), is bonded to phosphate oxygen atoms in an optimized structure. The values of binding energy (Ebd) are calculated as Ebd and are shown in Figure 11a. A positive Ebd value indicates that the adsorption is favorable and the interaction is stable.73 The calculated values of binding energy for Zn(II), Cd(II), Pb(II), and Hg(II) are 298.10, 219.35, 206.26, and 112.46 kcal/mol, respectively. Therefore, DFT calculations also verify that PSP shows the strongest adsorption selectivity toward Zn(II) among all tested heavy metal ions. These results are also within the paradigm of Pearson’s HSAB principle, wherein borderline cations Zn(II) and Pb(II) are expected to interact more strongly with the hard anion (O–) and, consequently, soft cations (Cd(II) and Hg(II)) interact the least.69 In general, the interaction between metal cations and the oxygen atom of PSP becomes stronger as the average M(II)–O bond distance decreases. To arrive at such a conclusion, single point energy (SPE) scans were carried out for all four metal cations, and the plots are shown in Figure S7 and the corresponding M(II)–O bond distances are plotted in Figure 11b, with the inset in Figure 11b pictorially describing Zn(II) ion binding. SPE scan results clearly indicate that the metal–oxygen distance increases in the order Zn < Pb < Cd < Hg; therefore, Zn(II) ions interact the most at a relatively short bond distance of 1.952 Å, while Hg(II) ions interact the least at 2.35 Å. Such measurements also suggest more strong and covalent interactions between Zn(II) ions and the PSP biosorbent.

Figure 10.

Optimized geometries of the cluster model PSP–M2+ showing phosphate oxygen as a preferable site for metal ions: (a) PSP-Zn(II), (b) PSP-Pb(II), (c) PSP-Cd(II), and (d) PSP-Hg(II). Red = oxygen; gray = carbon; orange = phosphorus; white = hydrogen; purple = Zn; black = lead; yellow = cadmium; gray = mercury.

Figure 11.

(a) Metal–oxygen bond length for PSP–metal complexes for Zn(II), Cd(II), Pb(II), and Hg(II) ions in an optimized geometry with the inset showing the interaction of Zn(II) ions. (b) Binding energy for Zn(II), Cd(II), Pb(II), and Hg(II) ions.

2.5. Selectivity of Adsorbent

In real water samples, heavy metal ions coexist in wastewater, especially Zn, Pb, and Cd ions. Therefore, it is interesting and also necessary to test the selective adsorption performance of PSP. For the competitive adsorption of Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) ions, 25 mg of PSP was added to 40 ml of solution containing 100 mg/L of each ion. For the purpose of comparison, a control experiment was carried out under the same batch conditions. The results are shown in Figure 12 and indicate excellent adsorption selectivity toward Zn ions. The same selectivity was observed from the DFT results, and the results are once again within the paradigm of the HSAB principle. We observe a slight decrease in adsorption capacity of Zn ions due to a competition between coexisting ions and Zn(II) ions for adsorption sites on PSP. This study suggests that Zn ions can be quantitatively separated from some binary (Zn(II)–Pb(II), Zn(II)–Cd(II) and Zn(II)–Hg(II)) and ternary mixtures (Zn(II)–Pb(II)–Hg(II) and Zn(II)–Cd(II)–Hg(II)) using a column loaded with PSP.

Figure 12.

Effect of coexisting ions on the equilibrium adsorption capacity under competitive batch conditions, indicating highly selective adsorption for Zn(II) ions. Batch conditions: initial metal concentration: 100 mg/L; pH: 6.5; contact time: 90 min; adsorbent dose: 25 mg; solution volume: 40 mL.

2.6. Mechanism of Metal Ion Uptake

The heavy metal ions are known to bind starch and cross-linked starch in three ways: (a) zinc starch inclusion complex,74 (b) ion exchange, and (c) adsorption. The zinc starch inclusion complex is a well-known and thoroughly investigated area, in which Zn(II) ions interact with two 6-CH2OH groups from one starch chain. This possibility of Zn(II) complexation can be ruled out as the 6-CH2OH groups are not free and they are busy in phosphodiester bond formation. Therefore, the uptake of metal ions on PSP could be explained in terms of ion exchange and adsorption processes. Although ion exchange and adsorption share some similar characteristics, ion exchange is a bulk phenomenon involving the entire volume of the adsorbent, while adsorption is typically a surface phenomenon. At low pH ≤ 4.0, the dominant mode of metal ion binding is exchange with H+ ions of PSP, especially at the phosphate center, as inferred from Mulliken charge analysis. At higher pH > 5.0, the surface of PSP attains enough negative charge, as can be easily seen from ζ-potential measurements. Due to the negatively charged surface of PSP, cationic target metal ions get attracted and finally get adsorbed on the surface of PSP. We summarize that the uptake of metal ions occurs either by ion exchange or adsorption or by both, depending on the charged state of the adsorbent, as shown schematically in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2. Schematic Representation of Two Modes of Metal Ion Uptake: Adsorption and Ion Exchange by PSP at Different pH Values.

2.7. Reusability of Adsorbent

Practically, an ideal adsorbent should not only possess good adsorption capacity, but also show excellent regeneration ability without any appreciable loss in adsorption capacity over multiple cycles. For the purpose of regenerating the PSP biosorbent, metal-complexed PSP was placed in 0.1 M HCl solution under continuous ultrasonication for desorption/cation exchange. The suspension was kept undisturbed for 3 h to ensure complete exchange/desorption of heavy metal cations. The partially settled suspension was centrifuged and washed with deionized (DI) water to remove excess acid, followed by drying at 40 °C. Now the regenerated PSP biosorbent is ready for reuse. As inferred from Figure 13, PSP revealed excellent regeneration/reusability over five adsorption cycles with a slight decrease (7.07%) in the adsorption capacity for Zn(II) ions. This slight decrease may be due to the loss of a few binding sites on the surface of the PSP biosorbent. Therefore, the good adsorption capacity and excellent reusable tendency of PSP categorize it as an ideal material for heavy metal decontamination.

Figure 13.

Adsorption of Zn(II), Cd(II), Pb(II), and Hg(II) on PSP over five consecutive adsorption cycles, revealing its excellent regeneration/reusability. Batch conditions: initial metal concentration: 100 mg/L; pH: 6.5; contact time: 90 min; adsorbent dose: 25 mg; solution volume: 40 mL.

3. Conclusions

A bio-based potato starch phosphate polymer adsorbent has been successfully prepared by a cross-linking reaction between phosphoryl chloride and hydroxyl groups of native potato starch. Under microwave and ultrasonic irradiation, the biosorbent develops into a dumbbell- and flower-shaped morphology. Cross-linking decreases the swelling tendency of starch and therefore increases the resistance to retrograde. PSP adsorbs Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) ions from aqueous medium with a maximum monolayer adsorption capacity of 130.54, 106.25, 91.84, and 51.38 mg/g, respectively. EDX elemental mapping studies of Zn-complexed PSP demonstrate uniform distribution of Zn ions over the surface of the PSP material. The experimental data fitted well with the Langmuir model. The adsorption process is quite fast, which could reach adsorption equilibrium within 90 min, and follows the pseudo-second-order kinetic model. The thermodynamic studies demonstrated that adsorption processes were endothermic and spontaneous. Adsorption performance of PSP showed good pH dependency, and the overall adsorption selectivity was further supported by DFT studies in terms of (a) interaction energies between PSP and Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) ions; (b) Mulliken charge analysis; and (c) M(II)–O bond length measurements. Moreover, the PSP biosorbent showed excellent reusability without any appreciable loss in adsorption performance over five adsorption cycles.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

Potato starch was supplied by HPLC, Mumbai, India (CAS NO: 9005-25-8) with an amylose content of 20%. Phosphoryl chloride (POCl3), AR grade, was purchased from Merck, Germany. All other chemicals used were purchased from Fischer scientific, U.K., and were used as purchased.

4.2. Preparation of PSP-Based Biosorbent

PSP was prepared by the method adopted by Zheng et al. with slight modifications.75 In a typical procedure, 10 g of NPS granules were ultrasonically dispersed in 30 mL of DI water containing 20% Na2SO4 to obtain a uniform dispersion. The pH of the suspension was adjusted to 11.0 with dilute NaOH solution. The dispersion was then subjected to microwave irradiation at 80 °C by placing the dispersion in a Monowave 100 (Anton Parr, operating at 500 W power) with constant stirring at 600 rpm for 30 min to accelerate the structural damage with an aim to increase the porosity of starch granules to allow more POCl3 to permeate the internal structure of starch. After microwave irradiation, 0.1% POCl3 (based on the dry weight of starch) was added to the starch dispersion under ultrasonication operating at 250 W power. Ultrasonication was continued for another 30 min to ensure complete cross-linking at 40 °C. The product was removed and the pH was then adjusted to pH 5.5 with dil. HCl. The product was then filtered and washed repeatedly with DI and then dried at 40 °C. The dried PSP was then sieved to obtain an average mesh size of 200 μm.

4.3. Phosphorus Analysis

The phosphorus content in PSP was analyzed spectrometrically according to the Polish and Norm procedure.76 Briefly, PSP was mineralized in conc. HNO3 and H2SO4. Then aqueous ammonium molybdate solution was added leading to the formation of phosphomolybdate containing Mo(VII) ions. The complex obtained was then reduced to a blue-colored solution containing Mo(V) ions with ascorbic acid. The blue-colored solution was analyzed for the content of phosphorus by measuring the absorbance at 823 nm. The phosphorus content was found from the calibration curve. The results were further confirmed by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (PerkinElmer optima 5300 DV). For PSP, we obtained a percent phosphorus content of 3.16, which was much higher than that reported earlier by Heo et al.77 This higher phosphorus content may be attributed to the presence of more phosphodiester cross-links, which arise mainly due to the collaborative effect of microwave and ultrasonic treatments.

4.4. Characterization of PSP

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of the sample were recorded over a range of 400–4000 cm–1 using a PerkinElmer Spectrum-100 FTIR. Thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) was carried out using a simultaneous thermal analyzer (STA, LINSEIS, USA 6807/8835/16) with a heating rate of 15 °C min–1 under an air atmosphere. The morphology was observed using a scanning electron microscope (Hitachi, S3000H, Japan). To corroborate the presence of Zn(II) ions over the surface of PSP, energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) and elemental mapping studies were carried out using a Zeiss Ultraplus-4095 instrument. ζ-Potentials of NPS and PSP were determined over a varied pH range (2–9) using a zetasizer nano ZS (Malvern Instruments Ltd., U.K.). Briefly, samples were ultrasonically dispersed in ultrapure water and analyzed at 25 °C. N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms were measured with a Micromeritics ASAP 2020 H surface area analyzer at 77 K. The specific surface areas of NPS and PSP were measured by the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method. Before the test, the powder samples were degassed at 300 °C under vacuum for 3 h. For a better understanding of pore size distribution in the potato starch phosphate adsorbent material, Barret–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) analysis was carried out using a Micromeritics ASAP 2020 H. The crystalline structure of the prepared samples was characterized using a X-ray diffractometer (Ultima-IV, Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) using Cu Kα radiation. The samples were scanned in the 2θ range of 5–45° with a scan rate of 5 min–1.

4.5. Rheological Characterization of NPS and PSP Gels

The rheological tests for NPS and PSP gels were carried out with an Anton Paar rheometer (MCR102 at 25 ± 0.01°) with a cone and plate system (50 mm diameter and 1.006° cone angle).

4.6. Adsorption Experiments

Adsorption studies were carried out by a usual batch method. Briefly, 25 mg of PSP was taken in a 100 mL flask to which 40 mL of different metal ion solutions were added. After continuous shaking for 3 h at 120 rpm, the suspension was centrifuged and filtered. The supernatant was analyzed for equilibrium adsorption concentration of Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) by atomic absorption spectroscopy (AA-6800 Shimadzu, Japan). The pH of the solution was adjusted to 2 to 9 using universal buffer. The amount of Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) adsorbed on PSP, i.e., qe (mg g–1) was calculated using the equation

| 6 |

where Co and Ce are the initial and equilibrium concentrations of metal ions (mg L–1), V is the volume of the solution (L), and M is the weight of the adsorbent (g).

4.7. Computational Details

Theoretical calculations were performed on a model material PSP using density functional theory (DFT) as incorporated in the Gaussian 03 set of codes. Geometry optimizations were carried out with Becke’s three-parameter hybrid model using the Lee–Yang–Parr correlation functional (B3LYP) and LanL2DZ basis set.78,79

Acknowledgments

We thank M.A. Khuroo, Head, Department of Chemistry, University of Kashmir, for providing all necessary facilities to carry out this work. L.A.M (File No. 09/251(0068)2015/EMR-1) would like to thank the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) for financial assistance in the form of a Senior Research Fellowship (SRF). We thank Zahid Ahmad Bhat, IISER, Pune, for EDX and elemental mapping studies.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.9b03607.

Illustration of phosphodiester bond formation by two consecutive nucleophilic substitution reactions between phosphorodichloridic acid and electronically rich 6CH2OH groups of NPS (Figure S1); FTIR spectra of PSP and Zn-complexed PSP obtained from DFT studies, showing close agreement with experimental data (Figure S2); surface area analysis (BET) with the inset showing pore dimensions (BJH) by N2 adsorption–desorption at 77 K for NPS and PSP (Figure S3); effect of adsorbent dose on the adsorption capacity of Zn(II) ions on PSP (Figure S4); effect of metal ion concentration on the equilibrium adsorption capacity of Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) on PSP (Figure S5); Mulliken charge analysis of PSP, wherein phosphate oxygen atoms are shown to carry more negative partial charges than either terminal oxygen or glycosidic oxygen, and hence, the phosphate oxygen is expected to be a more favorable site for the adsorption of metal cations (Figure S6); single point energy (SPE) scans for the interaction between Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II) ions and PSP, suggesting relatively more strong and covalent interactions of Zn(II) ions (Figure S7) (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Aragay G.; Pons J.; Merkoçi A. Recent Trends in Macro-, Micro-, and Nanomaterial-Based Tools and Strategies for Heavy-Metal Detection. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 3433–3458. 10.1021/cr100383r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Chan A.; Salsali H.; McBean E. Heavy Metal Removal (Copper and Zinc) in Secondary Effluent from Wastewater Treatment Plants by Microalgae. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 130–137. 10.1021/sc400289z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Malik L. A.; Bashir A.; Qureashi A.; Pandith A. H. Dectection and Removal of Heavy Metal Ions: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2019, 17, 1495–1521. 10.1007/s10311-019-00891-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shim H. Y.; Lee K. S.; Lee D. S.; Jeon D. S.; Park M. S.; Shin J. S.; Lee Y. K.; Goo J. W.; Kim S. B.; Chung D. Y. Application of Electrocoagulation and Electrolysis on the Precipitation of Heavy Metals and Particulate Solids in Waste water from the Soil Washing. J. Agric. Chem. Environ. 2014, 3, 130–138. 10.4236/jacen.2014.34015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jawor A.; Hoek E. M. V. Removing cadmium ions from water via nanoparticle-enhanced ultrafiltration. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 2570–2576. 10.1021/es902310e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir A.; Ahad S.; Pandith A. H. Soft Template Assisted Synthesis of Zirconium Resorcinol Phosphate Nanocomposite Material for the Uptake of Heavy-Metal Ions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2016, 55, 4820–4829. 10.1021/acs.iecr.6b00208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahad S.; Bashir A.; Manzoor T.; Pandith A. H. Exploring the ion exchange and separation capabilities of thermally stable acrylamide zirconium(IV) sulphosalicylate (AaZrSs) composite material. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 35914–35927. 10.1039/C6RA03077G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He W.; Ai K.; Ren X.; Wang S.; Lu L. Inorganic layered ion-exchangers for decontamination of toxic metal ions in aquatic systems. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 19593–19606. 10.1039/C7TA05076C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadnezhad G.; Abad S.; Soltani R.; Dinari M. Study on thermal, mechanical and adsorption properties of amine functionalized MCM-41/PMMA and MCM-41/PS nanocomposites prepared by ultrasonic irradiation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017, 39, 765–773. 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D.; Li Z.; Li W.; Zhong Z.; Xu J.; Ren J.; Ma Z. Adsorption Behavior of Heavy Metal Ions from Aqueous Solution by Soy Protein Hollow Microspheres. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 11036–11044. 10.1021/ie401092f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malik L. A.; Bashir A.; Manzoor T.; Pandith A. H. Microwave assisted synthesis of glutathione coated hallow zinc oxide for the removal of heavy metal ions from aqueous system. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 15976–15985. 10.1039/C9RA00243J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Soltani R.; Dinari M.; Mohammadnezhad G. Ultrasonic-assisted synthesis of novel nanocomposite of poly(vinyl alcohol) and amino-modified MCM-41: A green adsorbent for Cd(II) removal. Ultrasonics - Sonochemistry 2018, 40, 533–542. 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Mohammadnezhad G.; Soltani R.; Abad S.; Dinari M. A novel porous nanocomposite of aminated silica MCM-41 and nylon-6: Isotherm, kinetic, and thermodynamic studies on adsorption of Cu(II) and Cd(II). J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134, 45383. 10.1002/app.45383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Afshari M.; Dinari M. Synthesis of new imine-linked covalent organic framework as high efficient absorbent and monitoring the removal of direct fast scarlet 4BS textile dye based on mobile phone colorimetric platform. J. Hazard. Mater 2019, 121514 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Dinari M.; Hatami M. Novel N-riched crystalline covalent organic framework as a highly porous adsorbent for effective cadmium removal. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 102907 10.1016/j.jece.2019.102907. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Mohammadnezhad G.; Dinari M.; Soltani R. Preparation of modified boehmite/PMMA nanocomposites by in situ polymerization and assessment of their capability for Cu2+ ions removal. New J. Chem. 2016, 40, 3612–3621. 10.1039/C5NJ03109E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Dinari M.; Mohammadnezhad G.; Soltani R. Fabrication of poly(methyl methacrylate) /silica KIT-6 nanocomposites via in situ polymerization approach and their application for removal of Cu2+ from aqueous solution. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 11419–11429. 10.1039/C5RA23500F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dinari M.; Malekia M. H.; Bagheri R. Synthesis and characterization of new nitrogen- and oxygen-rich cyclohexanone–formaldehyde resin for fast Cd(II) adsorption in aqueous solution. Polym. Int. 2019, 68, 1636–1644. 10.1002/pi.5870. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L.; Wang Q.; Islam S. M.; Liu Y.; Ma S.; Kanatzidis M. G. Highly Selective and Efficient Removal of Heavy Metals by Layered Double Hydroxide Intercalated with the MoS42– Ion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 2858–2866. 10.1021/jacs.6b00110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varshney K. G.; Pandith A. H.; Gupta U. Synthesis and characterization of zirconium alumino phosphate: A new cation exchanger. Langmuir 1998, 14, 7353–7358. 10.1021/la970464j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dinari M.; Haghighi A.; Asadi P. Facile synthesis of Zn Al-EDTA layered double hydroxide/poly(vinyl alcohol) nanocomposite as an efficient adsorbent of Cd(II) ions from the aqueous solution. Appl. Clay Sci. 2019, 170, 21–28. 10.1016/j.clay.2019.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmanian O.; Dinarib M.; Abdolmaleki M. K. Carbon quantum dots/layered double hydroxide hybrid for fast and efficient decontamination of Cd(II): The adsorption kinetics and isotherms. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 428, 272–279. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.09.152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zargoosh K.; Kondori S.; Dinari M.; Mallakpour S. Synthesis of Layered Double Hydroxides Containing a Biodegradable Amino Acid Derivative and Their Application for Effective Removal of Cyanide from Industrial Wastes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2015, 54, 1093–1102. 10.1021/ie504064k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Ahad S.; Islam N.; Bashir A.; Rehman S.; Pandith A. H. Adsorption studies of Malachite green on 5-sulphosalicylic acid doped tetraethoxysilane (SATEOS) composite material. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 92788–92798. 10.1039/C5RA17838J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Rehman S.; Islam N.; Ahad S.; Fatima S. Z.; Pandith A. H. Preparation and characterization of 5-sulphosalicylic acid doped tetraethoxysilane composite ion-exchange material by sol–gel method. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 260, 313–322. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar A.; Hogland W.; Marques M.; Sillanpaa M. An overview of the modification methods of activated carbon for its water treatment applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 219, 499–511. 10.1016/j.cej.2012.12.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F.; Lu X.; Li X. Selective removals of heavy metals (Pb2+, Cu2+, and Cd2+) from wastewater by gelation with alginate for effective metal recovery. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 308, 75–83. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir A.; Ahad S.; Malik L. A.; Manzoor T.; Bhat M. A.; Dar G. N.; Pandith A. H. Removal of heavy metal ions from aqueous system by ion-exchange and biosorption methods. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2019, 17, 729–754. 10.1007/s10311-018-00828-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kou T.; Gao Q. New insight in crosslinking degree determination for cross linked starch. Carbohydr. Res. 2018, 458–459, 13–18. 10.1016/j.carres.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nska E. B.; Dyrek K.; Wenda E. Z.; Szczygie J.; Kruczała K. Effect of Starch Phosphorylation on Interaction With Chromium Ions in Aqueous Solutions. Starch 2019, 1800306 10.1002/star.201800306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat M. A.; Chisti H.; Shah S. A. Removal of Heavy Metal Ions from Water by Cross Linked Potato Starch Phosphate Polymer. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 1741–1747. 10.1080/01496395.2014.978469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q. J.; Zheng X. M.; Zhou L. L.; Zhang Y. F. Adsorption of Cu(II) and Methylene Blue by Succinylated Starch Nanocrystals. Starch - Stärke 2019, 71, 1800266 10.1002/star.201800266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Attar K.; Demey H.; Bouazza D.; Sastre A. M. Sorption and Desorption Studies of Pb(II) and Ni(II) from Aqueous Solutions by a New Composite Based on Alginate and Magadiite Materials. Polymers 2019, 11, 340. 10.3390/polym11020340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapo B.; Demey H.; Zapata J.; Romero C.; Sastre A. M. Sorption of Hg(II) and Pb(II) Ions on Chitosan-Iron(III) from Aqueous Solutions: Single and Binary Systems. Polymers 2018, 10, 367. 10.3390/polym10040367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demey H.; Melkior T.; Chatroux A.; Attar K.; Thiery S.; Miller H.; Grateau M.; Sastre A. M.; Marchand M. Evaluation of torrefied poplar-biomass as a low-cost sorbent for lead and terbium removal from aqueous solutions and energy co-generation. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 361, 839–852. 10.1016/j.cej.2018.12.148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demey H.; Barron-Zambrano J.; Mhadhbi T.; Miloudi H.; Yang Z.; Ruiz M.; Sastre A. M. Boron Removal from Aqueous Solutions by Using a Novel Alginate-Based Sorbent: Comparison with Al2O3 Particles. Polymers 2019, 11, 1509. 10.3390/polym11091509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haq F.; H Yu.; Wang L.; Teng L.; Haroon M.; Khan R. U.; Mehmood S.; Amin B. U.; Ullah R. S.; Khan A.; Nazi A. Advances in chemical modifications of starches and their applications. Carbohydr. Res. 2019, 476, 12–35. 10.1016/j.carres.2019.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haroon M.; Wang L.; Yu H.; Abbasi N. M.; Abdin Z.; Saleem M.; Khan R.; Summeullah R.; Chen Q.; Wu J. Chemical modification of starch and its application as an adsorbent material. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 78264–78285. 10.1039/C6RA16795K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur L.; Singh J.; Singh N. Effect of cross-linking on some properties of potato (Solanum tuberosumL.) starches. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 2006, 86, 1945–1954. 10.1002/jsfa.2568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneya T.; Ishibashi K.; Hironaka K.; Yamamoto K. Influence of cross-linked potato starch treated with POCl3 on DSC, rheological properties and granule size. Carbohydr. Polym. 2003, 53, 447–457. 10.1016/S0144-8617(03)00143-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch J. B.; Kokini J. L. Understanding the Mechanism of Cross-Linking Agents (POCl3, STMP, and EPI) Through Swelling Behavior and Pasting Properties of Cross-Linked Waxy Maize Starches. Cereal Chem. 2002, 79, 102–107. 10.1094/CCHEM.2002.79.1.102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J.; He R. M.; Gao F. Y.; Kou Z. L.; Lan L. H.; Lan P.; Liao A. P. High-Efficient Preparation of Cross-linked Cassava Starch by Microwave Ultrasound-Assisted and Its Physicochemical Properties. Starch - Stärke 2019, 71, 1800273 10.1002/star.201800273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Achmatowicz M. M.; Thiel O. R.; Colyer J. T.; Hu J.; Elipe M. V. S.; Tomaskevitch J.; Tedrow J. S.; Larsen R. D. Hydrolysis of phosphoryl chloride (POCl3): characterization, in situ detection, and safe quenching of energetic metastable intermediate. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2010, 14, 1490–1500. 10.1021/op1001484. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z.; Cheng W.; Chen H.; Fu X.; Faxing X.; Luo F.; Nie L. Preparation and Properties of Enzyme-Modified Cassava Starch–Zinc Complexes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 4631–4638. 10.1021/jf4016015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Wang Z. W. Optimization of reaction conditions for resistant canna edulis ker starch phosphorylation and its structural characterization. Ind. Crops Prod. 2009, 30, 105–113. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2009.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bahrami M.; Amiri M. J.; Bagheri F. Optimization of the lead removal from aqueous solution using two starch based adsorbents: Design of experiments using response surface methodology (RSM). J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 102793 10.1016/j.jece.2018.11.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh V.; Urs R. G.; Somashekarappa H.; Ali S. Z.; Someshekar R. X-ray analysis of different starch granules. Bull. Mater. Sci. 1995, 18, 549–555. 10.1007/BF02744840. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Rubio A.; Flanagan B. M.; Gilbert E. P.; Gidley M. J. A novel approach for calculating starch crystallinity and its correlation with double helix content: a combined XRD and NMR study. Biopolymers 2008, 89, 761–768. 10.1002/bip.21005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tako M.; Hizukuri S. Gelatinization mechanism of potato starch. Carbohydr. Polym. 2002, 48, 397–401. 10.1016/S0144-8617(01)00287-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gałkowska D.; Juszczak L. Effects of amino acids on gelatinization, pasting and rheological properties of modified potato starches. Food Hydrocolloids 2019, 92, 143–154. 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.01.063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steeneken P. A. M. Rheological property of aqueous suspensions of swollen starch granules. Carbohydr. Polym. 1989, 11, 23–42. 10.1016/0144-8617(89)90041-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu F.; Bertoft E.; Li G. Morphological, Thermal, and Rheological Properties of Starches from Maize Mutants Deficient in Starch Synthase III. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 6539–6545. 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b01265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber K. C.; BeMiller J. N. Location of sites of reaction within starch granules. Cereal Chem. 2001, 78, 173–180. 10.1094/CCHEM.2001.78.2.173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willett J. L. Packing characteristics of starch granules. Cereal Chem. 2001, 78, 64–68. 10.1094/CCHEM.2001.78.1.64. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thys R. C. S.; Westfahl H.; Noreña C. P. Z.; Marczak L. D. F.; Silveira N. P.; Cardoso M. B. Effect of alkaline treatment on the ultrastructure of starch granules. Biomacromolecules. 2008, 9, 1894–1901. 10.1021/bm800143w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogbodu R. O.; Omorogie M. O.; Unuabonah E. I.; Babalola J. O. Biosorption of Heavy Metals from Aqueous Solutions by Parkia biglobosa Biomass: Equilibrium, Kinetics, and Thermodynamic Studies. Environ. Prog. Sustainable Energy 2015, 34, 1694–1704. 10.1002/ep.12175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du Z.; Zheng T.; Wang P.; Hao L.; Wang Y. Fast microwave-assisted preparation of a low-cost and recyclable carboxyl modified lignocellulose-biomass jute fiber for enhanced heavy metal removal from water. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 201, 41–49. 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyzas G. Z.; Siafaka P. I.; Lambropoulou D. A.; Lazaridis N. K.; Bikiaris D. N. Poly(itaconic acid)-Grafted Chitosan Adsorbents with Different Cross-Linking for Pb(II) and Cd(II) Uptake. Langmuir 2014, 30, 120–131. 10.1021/la402778x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X.; Liu X.; Anderson D. P.; Chang P. R. Modification of porous starch for the adsorption of heavy metal ions from aqueous solution. Food Chem. 2015, 181, 133–139. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.02.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed C.; Mahabir S.; Mohammed K.; John N.; Lee K. Y.; Ward K. Calcium alginate thin films derived from Sargassum natans for the selective adsorption of Cd2+, Cu2+ and Pb2+ ions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 1417–1425. 10.1021/acs.iecr.8b03691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz A. J.; Espínola F.; Ruiz E. Removal of heavy metals by Klebsiellas sp.3S1 Kinetics, equilibrium and interaction mechanisms of Zn(II) biosorption. J Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2018, 93, 1370–1380. 10.1002/jctb.5503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ngabura M.; Hussain S. A.; Ghani W. A. W.; Jami M. S.; Tan W. P. Utilization of renewable durian peels for biosorption of zinc from Wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 2528–2539. 10.1016/j.jece.2018.03.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paduraru C.; Tofan L.; Teodosiu C.; Bunia I.; Tudorachi N.; Toma O. Biosorption of zinc(II) on rapeseed waste: Equilibrium studies and thermogravimetric Investigations. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2015, 94, 18–28. 10.1016/j.psep.2014.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Awokoya K. N.; Moronkola B. A. Preparation and characterization of succinylated starch as adsorbent for the removal of Pb(II) ions from aqueous media. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2012, 1, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim B. M.; Fakhre N. A. dification of starch for adsorption of heavy metals from synthetic wastewater. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 123, 70–80. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X.; Du B.; Wei Q.; Yang J.; Hu L.; Yan L.; Xu W. Synthesis of amino functionalized magnetic graphenes composite material and its application to remove Cr(VI), Pb(II), Hg(II), Cd(II) and Ni(II) from contaminated water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 278, 211–220. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.05.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salih S. S.; Ghosh T. K. Adsorption of Zn(II) ions by chitosancoated diatomaceous earth. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 106, 602–610. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L.; Zhang S. H.; Ju B. Z.; Yang J. Z.; Quan X. Removal of Pb(II) from aqueous solution by cross-linked starch phosphate carbamate. J. Polym. Res. 2006, 13, 213–217. 10.1007/s10965-005-9028-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L.; Sun C. M.; Li G. Y.; Liu C. P.; Ji C. N. Thermodynamics and kinetics of Zn(II) adsorption on crosslinked starch phosphates. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 161, 510–515. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.; Wei M.; Huang Y. Biosorption of Multifold Toxic Heavy Metal Ions from Aqueous Water onto Food Residue Eggshell Membrane Functionalized with Ammonium Thioglycolate. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 4988–4996. 10.1021/jf4003939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu Y.; Yang J.; Qu R.; Gao Y.; Du N.; Chen H.; Sun C.; Wang W. Synthesis of Silica-Gel-Supported Sulfur-Capped PAMAM Dendrimers for Efficient Hg(II) Adsorption: Experimental and DFT Study. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2016, 55, 3679–3688. 10.1021/acs.iecr.6b00172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hakami O.; Zhang Y.; Banks C. J. Thiol-functionalised mesoporous silica-coated magnetite nanoparticles for high efficiency removal and recovery of Hg from water. Water Res. 2012, 46, 3913–3922. 10.1016/j.watres.2012.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdolmohammad-Zadeh H.; Mohammad-Rezaei R.; Salimi A. Preconcentration of mercury(II) using a magnetite@carbon/dithizone nanocomposite, and its quantification by anodic stripping voltammetry. Microchim. Acta 2019, 10.1007/s00604-019-3937-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Wang S.; Liu Y.; Jiang L.; Song B.; Li M.; Zeng G.; Tan X.; Cai X.; Ding Y. Adsorption of Cu(II), Pb(II), and Cd(II) Ions from Acidic Aqueous Solutions by Diethylenetriaminepentaacetic Acid-Modified Magnetic Graphene Oxide. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2017, 62, 407–416. 10.1021/acs.jced.6b00746. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Persson I. Hydrated metal ions in aqueous solution: How regular are their structure. Pure Appl. Chem. 2010, 82, 1901–1917. 10.1351/PAC-CON-09-10-22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Sahoo J. K.; Yella A.; Schladt T. D.; Pfeiffer S.; Kolb U.; Tremel W.; et al. From Single Molecules to Nanoscopically Structured Materials: Self-Assembly of Metal Chalcogenide/Metal Oxide Nanostructures Based on the Degree of Pearson Hardnes. Chem. Mater. 2011, 23, 3534–3539. 10.1021/cm201178n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Lo-Pachin R. M.; Gavin T.; De-Caprio A.; Barber D. S. Application of the Hard and Soft, Acids and Bases (HSAB) Theory to Toxicant–Target Interactions. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2012, 25, 239–251. 10.1021/tx2003257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarei S.; Niad M.; Raanaei H. The removal of mercury ion pollution by using Fe3O4-nanocellulose: Synthesis, characterizations and DFT studies. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 344, 258–273. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.; Xu W. H.; Yang R.; Zhou T.; Hou D.; Zheng X.; Liu J. H.; Huang X. J. Electrochemical and Density Functional Theory Investigation on High Selectivity and Sensitivity of Exfoliated Nano-Zirconium Phosphate toward Lead(II). J. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 3984–3990. 10.1021/ac3037014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z.; et al. Synthesis and characterization of amylose–zinc inclusion complexes. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 137, 314–320. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.10.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G. H.; Han H. L.; Bhatty R. S. Functional properties of cross-linked and hydroxypropylated waxy hull-less barley starches. Cereal Chem. 1999, 76, 182–188. 10.1094/CCHEM.1999.76.2.182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polish Norm PN-EN ISO ‘Starches and derived products. Determination of total phosphorus content—spectrophotometric method’ 3946, 2000.

- Heo H.; Lee Y. K.; Chang Y. H. Chang Rheological, pasting, and structural properties of potato starch by cross-linking. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, 1–13. 10.1080/10942912.2017.1368549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. 10.1063/1.464913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.; Yang W.; Parr G. R. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.