Abstract

Transparent single crystals of two new iodates K3Sc(IO3)6 and KSc(IO3)3Cl have been synthesized hydrothermally. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction was used to determine their crystal structures. Both compounds crystallize in non-centrosymmetric space groups. The compound K3Sc(IO3)6 crystallizes in the orthorhombic space group Fdd2. The crystal structure is made up of [ScO6] octahedra, [IO3] trigonal pyramids, and [KO8] distorted cubes. The compound KSc(IO3)3Cl crystallizes in the trigonal space group R3. The building blocks are [ScO6] octahedra, [KO12] polyhedra, and [IO3] trigonal pyramids. The Cl– ions act as counter ions and reside in tunnels in the crystal structure. The second harmonic generation (SHG) measurements at room temperature, using 1064 nm radiation, on polycrystalline samples show that the SHG intensities of K3Sc(IO3)6 and KSc(IO3)3Cl are around 2.8 and 2.5 times that of KH2PO4 (KDP), respectively. In addition, K3Sc(IO3)6 and KSc(IO3)3Cl are phase-matchable at the fundamental wavelength of 1064 nm. The large anharmonicity in the optical response of both compounds is further supported by an anomalous temperature dependence of optical phonon frequencies as well as their enlarged intensities in Raman scattering. The latter corresponds to a very large electronic polarizability.

Introduction

New strategies for designing non-centrosymmetric (NCS) materials are attracting interest because of their potential technological applications. Some properties of NCS materials, for example, ferroelectricity, piezoelectricity, and optical activity like second-harmonic generation (SHG), are often linked to the manufacturing of data storage devices, sensors, and laser devices.1−3

A synthetic strategy that has proven successful to increase the probability to form NCS compounds is to include acentric building units in the crystal structure.4−6 Lone electron pair cations of p-elements such as I5+, Te4+, or Se4+ comprise an active electron pair that occupies space and has a volume that can be compared with the volume of an O2– anion. Those cations tend to adopt asymmetric one-sided coordination geometries such as trigonal pyramidal or see-saw coordination. The heaviest cations of this kind are Bi3+ and Pb2+, and because of their stronger attracting nucleus, they are equipped with a less stereochemically active lone pair occupying a relatively small volume. These ions often have a high coordination number, and they may form asymmetric building units such as distorted cubes.7

There are several optically active compounds reported that comprise p-element lone-pair cations. One such compound is BiSeO3F, which involves the two lone pair cations Bi3+ and Se4+ and in addition a halide ion as well.8 There are also NCS iodates reported in the literature that belong to the L–I5+–O system, with L = Bi3+, and show optical activity, e.g. BiO(IO3)9 and Bi2(IO4)(IO3)3.10 Additionally, the system A–L–I5+–O also exists with relevant reported compounds belonging to A2BiI5O15, where A = K+ or Rb+ and L = Bi3+.11

Another family of iodates is A–M–I–O that combines I5+ with highly coordinated A ions, Na+, K+, Rb+, or Cs+, with a transition metal that does not give colored compounds, for example, Zn2+, Mn2+, or Mo6+. Examples of reported NCS compounds belonging to this system are K2Mn(IO3)4(H2O)2 and K2Zn(IO3)4(H2O)2.12

In this study, the K+–Sc3+–I5+–O and K+–Sc3+–I5+–Cl systems are explored, and two new NCS compounds are reported, K3Sc(IO3)6 and KSc(IO3)3Cl. Both are SHG active with intensities that are approximately 2.8 and 2.5 times that of KDP for K3Sc(IO3)6 and KSc(IO3)3Cl, respectively.

Results and Discussion

Crystal Structure of K3Sc(IO3)6

The new iodate K3Sc(IO3)6 crystallizes in the orthorhombic NCS space group Fdd2 with unit cell parameters a = 39.507(3) Å, b = 8.2507(6) Å, and c = 11.3283(7) Å. Crystal structure refinement data are summarized in Table 1. There is one crystallographically independent Sc3+, two K+, three I5+, and nine O2– ions in the crystal structure. The oxidation states of the cations are confirmed by bond valence sum (BVS) calculations using the theoretical bond distance values from Brown and Altermatt.19 There are three building units in the crystal structure, [KO8] distorted cubes, [ScO6] octahedra, and [IO3] trigonal pyramids. An overview of the structure is shown in Figure 1a.

Table 1. Crystal Data and Refinement Parameters for K3Sc(IO3)6 and KSc(IO3)3Cl.

| empirical formula | K3Sc(IO3)6 | KSc(IO3)3Cl |

| formula weight | 1211.66 | 644(1) |

| temperature (K) | 294(2) | 294(2) |

| wavelength (Å) | 0.71073 | 0.71073 |

| crystal system | orthorhombic | trigonal |

| space group | Fdd2 | R3 |

| a (Å) | 39.507(3) | 8.087(1) |

| b (Å) | 8.251(1) | 8.087(1) |

| c (Å) | 11.328(1) | 27.577(1) |

| volume (Å3) | 3692.5(4) | 1562.11(13) |

| Z | 8 | 6 |

| density calc. (g cm–3) | 4.359 | 4.109 |

| F(000) | 4320.0 | 1728 |

| crystal color | colorless | colorless |

| crystal habit | plate | orthorhombic |

| crystal size | 0.05 × 0.05 × 0.01 | 0.1 × 0.08 × 0.05 |

| θ range for data collection (deg) | 3.098–26.361 | 2.216–46.484 |

| index ranges | –49 ≤ h ≤ 47 | –16 ≤ h ≤ 16 |

| –7 ≤ k ≤ 10 | –16 ≤ k ≤ 16 | |

| –14 ≤ l ≤ 14 | –54 ≤ l ≤ 44 | |

| reflections collected | 6040 | 20,073 |

| independent reflections | 1378 [R(int) = 0.039] | 4576 [R(int) = 0.0316] |

| Flack parameter | 0.11(4) | 0.47(3) |

| data/restraints/parameters | 1703/1/83 | 5220/1/91 |

| refinement method | full-matrix least squares refinement on F2 | full-matrix least squares refinement on F2 |

| goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.133 | 1.105 |

| final R indices | R1 = 0.0401 | R1 = 0.0223 |

| [I > 2σ(I)]α | wR2 = 0.0562 | wR2 = 0.0443 |

| R indices all data | R1 = 0.0625 | R1 = 0.0300 |

| wR2 = 0.0603 | wR2 = 0.046 |

Figure 1.

(a) Overview of the K3Sc(IO3)6 unit cell along [010]. I atoms: yellow and O atoms: red. (b) [K3O18]∞ zig-zag trimers along [100]. (c) Alternating [IO3] and [I2O5] groups due to splitting of I2 and I3.

According to Brown’s operational definition of bond lengths, a ligand should contribute with at least 4% to the valence of the central cation in order to be considered to belong to the primary coordination sphere; this definition sets the maximum distance for the K–O bonds to be 3.32 Å.20 There are eight K–O distances that fulfill this condition, and they are in the range 2.644(13)–3.168(15) Å. The distorted cubes [K1O8] and [K2O8] are connected to each other via edge-sharing to form [K3O18] trimers along [100]; see Figure 1b.

All the three crystallographically independent iodine atoms have a trigonal pyramidal [IO3] coordination. The one-sided coordination is due to the presence of the stereochemically active lone-pair on I5+. The I–O bond distances are in the range 1.748(10)–2.100(17) Å that is close to the I–O bond distance range, 1.77(3)–1.95(3) Å, reported for I2O5.21 The [I1O3] trigonal pyramids are isolated from each other, and are connected to one [ScO6] octahedron via corner-sharing and to two [K1O8] distorted cubes via corner- and edge-sharing, respectively. The [I2O3] and [I3O3] trigonal pyramids alternate and almost form [I2O6]∞ chains along [010]. However, the O7 and O8 atoms compete for both I2 and I3, resulting in that they split into two positions, each with 0.5 probability. In practice, this means that there are no chains, but rather have alternating [I2O5] groups and [IO3] groups (see Figure 1c).

The [ScO6] octahedra connect to a [IO3] trigonal pyramid at each corner (two of each of I1, I2, and I3) and two [K2O8] distorted cubes via edge-sharing. The Sc–O bond distances are in the range 2.035(7)–2.137(14) Å, and are close to the Sc–O bond distance range 2.08–2.16 Å, as reported for Sc2O3.22

A family of polar compounds is reported in the literature, A2Pt(IO3)6 (A = H3O, Na, K, Rb, and Cs). The iodine atoms form [IO3] trigonal pyramids with I–O bonds from 1.782(9) to 1.905(10) Å. In this group of compounds, there are highly coordinated A ions, where, for example, Na is nine coordinated with Na–O distances in the range 2.570(11)–2.997(19) Å. Finally, the platinum atoms form regular isolated [PtO6] octahedra with Pt–O bond distances between 1.994(8) and 1.998(6) Å.23 This family has similar building groups, with bond length values comparable to K3Sc(IO3)6 iodate. An isostructural compound KH(IO3)2 is previously described that crystallizes in the same space group Fdd2 having similar unit cell parameters.24

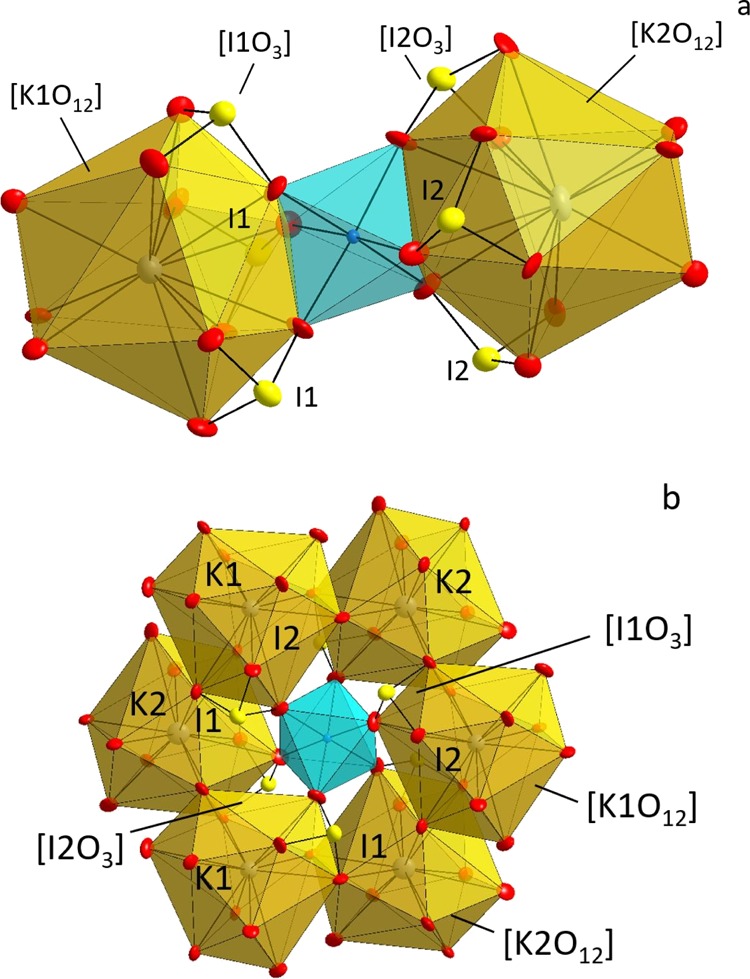

Crystal Structure of KSc(IO3)3Cl

The new compound KSc(IO3)3Cl crystallizes in the trigonal space group R3 with unit cell parameters a = 8.0875(3) Å and c = 27.5774(12) Å. The crystal structure was solved from single-crystal X-ray data, and the refinement data are presented in Table 1. There are two crystallographically independent atoms of the ingoing cations K+, I5+, and Sc3+, respectively, and six independent O2– and two Cl– anions. The oxidation state of the ions was confirmed by BVS calculations.19

An overview of the crystal structure is shown in Figure 2a. The structure consists of two types of [KO12] distorted polyhedra, [IO3] trigonal pyramids, and [ScO6] octahedra, respectively. The [KO12] and [ScO6] building blocks form a framework with tunnels along both [100] and [110], where the Cl– ions reside as counter ions. The Cl1 atom is surrounded by six iodine atoms, three I1 at a distance ranging from 3.297(2) to 3.298(2) Å, and three I2 atoms with distances that average at 3.182(3) Å. The Cl2 atom is also surrounded by three I1 and three I2 with distances that average at 3.224(2) atoms and 3.265(2) Å, respectively. Those long distances to the closest cations make both the Cl– anions under-bonded with calculated BVS values of 0.57 and 0.58 for Cl1 and Cl2, respectively; see Figure 2b. The long distances make it likely possible to replace Cl– with e.g. Br– or I– in the crystal structure.

Figure 2.

(a) Overview of KSc(IO3)3Cl with tunnels along [100] where the Cl atoms reside. (b) Cl1 and Cl2 in the channels of KSc(IO3)3Cl with surrounding I1 and I2 atoms.

The I5+ ions adopt one-sided coordination to form [IO3] trigonal pyramids that do not polymerize. The I–O bond lengths are in the range 1.730(6)–1.848(6) Å that is in agreement with the values of I2O5, 1.77(3)–1.95(3) Å.21 The K–O bond distances are in the range 2.888(7)–3.315(7) Å in the [KO12] distorted polyhedra. The longest K–O bond length is on the wedge of the aforementioned acceptable upper limit of 3.32 Å.27 The Sc–O distances are in the range 2.054(6)–2.088(7) Å, and they are in agreement with the Sc–O bond distance range 2.08–2.16 Å reported for Sc2O3.22 There are two crystallographically unique Sc atoms in the structure, Sc1 and Sc2. The [Sc1O6] octahedron connects to one [K1O12] and one [K2O12] polyhedron via edge-sharing as well as to three [I1O3] and three [I2O3] trigonal pyramids via corner-sharing, see Figure 3a. The [Sc2O6] octahedra link with three [K1O12] and three [K2O12] polyhedra. The latter form a ring around [Sc2O6] of edge-sharing alternating polyhedra. In addition, three [I1O3] and three [I2O3] trigonal pyramids connect to [Sc2O6] via corner-sharing; see Figure 3b.

Figure 3.

Two different Sc atoms in KSc(IO3)3Cl: (a) Sc1 and (b) Sc2.

Several iodates that also contain chlorine are reported previously. In Pb3[IO3]2Cl4, the I5+ ions form [IO3] groups with I–O bond distances in the range 1.808–1.812 Å. The Pb atoms are six- and eight-coordinated, forming [PbO4Cl2] and [PbO4Cl4] groups, respectively, with a Pb–Cl bond range of 2.868(2)–3.042(2) Å and a Pb–O bond distance range of 2.506(7)–2.762(7) Å.26 K2Bi(IO3)4Cl contains [IO3] and [KO7Cl2] groups with an I–O bond distance from 1.780(5) to 1.865(5) Å and a K–O bond distance range 2.705(6)–3.339(5) Å. The I–Cl distances are between 3.088 and 3.219 Å.27 Another example of iodate chloride is Cd(IO3)Cl, which is a chain compound where the Cl atoms bond to Cd to form [CdO4Cl2] octahedra with a Cd–Cl bond distance of 2.566(2) Å and Cd–O bond distances that are in the range of 2.308(3)–2.314(2) Å. The iodine atoms form trigonal pyramids that connect to the chains with I–O bond lengths of 1.813(2)–1.833(3) Å.28 The distance values in the aforementioned examples are close to the corresponding ones in KSc(IO3)3Cl.

SHG Properties of K3Sc(IO3)6 and KSc(IO3)3Cl

SHG intensity versus particle size revealed that K3Sc(IO3)6 and KSc(IO3)3Cl have SHG intensities that are approximately 2.8 and 2.5 times that of KDP, respectively, see Figure 4. The SHG intensities of both samples are comparable to similar materials.11,12 The measurements also indicate that both K3Sc(IO3)6 and KSc(IO3)3Cl are phase-matchable, and falls in the class A category of SHG materials.29,30

Figure 4.

Polycrystalline SHG results of K3Sc(IO3)6 and KSc(IO3)3Cl in comparison to KDP.

Optical Spectroscopy of K3Sc(IO3)6 and KSc(IO3)3Cl

Raman scattering in the temperature range 4–300 K was carried out to study if there were signs of phase transitions.

The symmetry analysis of K3Sc(IO3)6 with Fdd2 (43) leads to 44 A1 + 44 A2 + 46 B1 + 46 B2 modes with a total sum of 180 modes that could be observable in Raman scattering or IR spectroscopy. To these modes also, the I02A and I02B iodine split positions contribute with reduced intensity due to their partial occupation. The experimental Raman spectra show approximately 50 modes in the frequency range 35–860 cm–1. The difference between the expected and observed modes can be explained by a smaller intensity or near degeneracy of some modes.

The experimental spectrum of modes can be divided into three frequency ranges with the typical frequency ranges 35–190 and 205–420 cm–1, and the high frequency range 700–860 cm–1; see Figure 5; the latter range is attributed to IO3 modes.

Figure 5.

Raman scattering spectra of K3Sc(IO3)6 at four different temperatures. The insets show the frequency, linewidth, and intensity of selected phonons at 47, 260, 720, and 860 cm–1, respectively.

The modes at 740 cm–1 and 780 cm–1 have extremely high scattering intensity. With 200 and 90 ct/s peak intensities, they are, respectively, factors 20 and 9 more intense than the optical phonon of Si under similar experimental conditions. Both modes show a softening of the peak frequency with decreasing temperatures, different from the anharmonicity of a normal optical phonon; see the inset of Figure 5.

The symmetry analysis of KSc(IO3)3Cl with R3 (146) leads to 30A + 30 1E + 30 2E modes. This corresponds to a sum of 90 optically active modes. In the Raman spectra, approximately 23 modes are observed in the frequency range 0–950 cm–1, see Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Raman scattering spectra of KSc(IO3)3Cl at four temperatures. The insets show the frequency, linewidth, and intensity of selected phonons at 40, 418, 790, and 780 cm–1, respectively.

The spectrum of KSc(IO3)3Cl can also be divided into three frequency ranges. However, because of the smaller number of modes, it is easier to analyze. There exists an equidistant ladder-like spectrum of modes at 30–160 cm–1 that resembles rotational excitations of molecules. Furthermore, there exist modes with different frequency separations in an intermediate frequency range 190–420 cm–1 and in a high frequency range 730–920 cm–1.

In the latter range, the mode at 790 cm–1 has the highest scattering intensity. With 140 ct/s peak intensity, it is a factor 14 more intense than the optical phonon of Si.

This mode also shows an anomalous softening with decreasing temperatures, while most of the phonons harden with decreasing temperatures, see insets of Figure 6. Nevertheless, further phonons with anomalous frequency evolution exist at 36 and 420 cm–1.

As mentioned above, the phonon spectra of K3Sc(IO3)6 and KSc(IO3)3Cl show rather distinct groups of modes with different intensities and frequency separations. This grouping is rationalized within the composition and functional groups of K3Sc(IO3)6 and KSc(IO3)3Cl. Regarding their frequency, K and Sc displacements contribute mainly to lower frequencies. The iodate group mainly contributes to high-frequency local vibrations. For the latter, stretching vibrations in the frequency range of 750–800 cm–1 have indeed been reported in the literature. However, bending modes are also expected in the range 300–450 cm–1.31,32 The rather different effect of temperature on the modes is due to the different mechanisms of anharmonicity that collective phonon vibrations and local modes are experiencing. A collective optical vibration can decay into pairs of acoustic modes based on the anharmonicity of the lattice potential. Such a decay process is strongly reduced for a local mode enhancing their thermal occupation. Therefore, the electronic polarizability is enhanced leading to a large scattering intensity in Raman scattering experiments. The observed scattering intensity with a ratio of 1.4 for the largest intensity modes compares well with the ratio of SHG enhancements of K3Sc(IO3)6 compared to KSc(IO3)3Cl.

Conclusions

Two new NCS iodate compounds are synthesized hydrothermally, K3Sc(IO3)6 and KSc(IO3)3Cl. The crystal structures are determined from single-crystal X-ray diffraction data. The compound K3Sc(IO3)6 iodate crystallizes in the orthorhombic space group Fdd2 with unit cell parameters a = 39.507(3) Å, b = 8.2507(6) Å, and c = 11.3283(7) Å, and the compound KSc(IO3)3Cl crystallizes in the trigonal space group R3 with unit cell parameters a = 8.0875(3) Å and c = 27.5774(12) Å. SHG measurements at 1064 nm indicate that both K3Sc(IO3)6 and KSc(IO3)3Cl are attractive candidates for nonlinear optical applications. The related large SHG intensities that are around 2.8 and 2.5, respectively, compared to that of KH2PO4 (KDP), are attributable to a very large electronic polarizability that also shows up in the enhanced Raman scattering intensity of stretching modes of the iodate groups.

Experimental Section

Transparent single crystals of plate-like K3Sc(IO3)6 and block-like KSc(IO3)3Cl were synthesized via hydrothermal synthesis. The compound K3Sc(IO3)6 was prepared from the starting materials KIO3 (Alfa Aesar, 98%), I2O5 (Sigma, 98%), and Sc2O3 (Koch-Light Laboratories, 99%) mixed in a molar ratio of 3:1.5:0.5. KSc(IO3)3Cl was prepared from KIO3 (Alfa Aesar, 98%), I2O5 (Sigma, 98%), and ScCl3 (Strem. Chemicals, 99%) mixed in a molar ratio of 1:1:1. The starting materials were each mixed with 3 ml of deionized water in a 23 ml Teflon-lined autoclave. The reaction conditions were 230 °C, a temperature plateau of 72 h, and a cooling rate of ca 21 °C/h for both compounds. The product was purified by rinsing in hot water to dissolve the unreacted starting materials. The compounds were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, HITACHI-TM3000), and their composition was analyzed by energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). Structural characterization was done by single-crystal X-ray diffraction data obtained from a Bruker D8 Venture diffractometer with Mo Kα radiation; λ = 0.710730 Å. Data integration was done with software SAINT13 and the absorption correction with software SADABS14 provided by the manufacturer. The structures were solved by dual space methods using software SHELXT-2014/715 and refined by the full matrix on F2 using the program SHELXL-2014/7.16 All atomic positions were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters for both compounds. Structural drawings were made with software DIAMOND.17 Powder X-ray diffraction was employed for the confirmation of the sample purity using a PANalytical X’Pert PRO diffractometer and comparing the experimental patterns with the relevant theoretical patterns. Data collection was done in a scanning mode between 5° and 60° and with a θ-step of 0.013.

Raman scattering experiments have been performed using a microspectrometer (Dilor LabRAM), using 532 nm-laser radiation of 32.7 μW, and a microscope optics with 50×. The spectra were recorded without a polarization analyzer, as the shape of the single crystals leads to an internal light polarization scrambling in the transparent sample. The temperature dependence has been recorded using a microcryostat in the range 4–300 K. The phonon intensity has been compared with scattering on the 520 cm–1 phonon of silicon under similar experimental conditions. Such an intensity is proportional to the electronic polarizability at the energy of incident laser radiation with respect to the investigated phonon displacement.

For second-harmonic generation (SHG) measurements, K3Sc(IO3)6 and KSc(IO3)3Cl polycrystals were ground and sieved into distinct particle size ranges (<20, 20–45, 45–63, 63–75, 75–90, and 90–125 μm). Relevant comparisons with known SHG materials were made by grinding and sieving crystalline KDP into the same particle size range. A 1064-nm pulsed Nd:YAG laser (Quantel Laser, Ultra 50) generated the fundamental light, and the SHG intensity was recorded at room temperature on an oscilloscope (Tektronix, TDS3032) regarding different particle size ranges. No index matching fluid was used in any of the experiments. Please refer to Ok et al. for a detailed description.18

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out with support from the Swedish Research Council (VR) grant 2014-3931, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft DFG LE967/16-1, DFG-RTG 1952/1, the NTHSchool for Contacts in Nanosystems and Quanomet. P.S.H. and W.Z. thank the Welch Foundation (Grant E-1457) for support.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.9b04288.

Tables of atomic coordinates, bond lengths, and BVS calculations. Further details on crystal structural investigations can be obtained from the joint CCDC/FIZ Karlsruhe deposition service, deposit numbers CSD 1959925 and CSD 1959926 for KSc(IO3)3Cl and K3Sc(IO3)6, respectively (PDF)

Author Present Address

∥ Physics Faculty, Lomonosov Moscow State University, 119991 Moscow, Russia.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Aoki T.; Hiranaga Y.; Cho Y. High-density ferroelectric recording using a hard disk drive-type data storage system. J. Appl. Phys. 2016, 119, 184101. 10.1063/1.4948940. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moubarak P. M.; Ben-Tzvi P.; Zaghloul M. E. A Self-Calibrating Mathematical Model for the Direct Piezoelectric Effect of a New MEMS Tilt Sensor. IEEE Sens. J. 2012, 12, 1033–1042. 10.1109/jsen.2011.2173188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jafarzadeh P.; Menezes L. T.; Cui M.; Assoud A.; Zhang W.; Halasyamani P. S.; Kleinke H. BaCuSiTe3: A Noncentrosymmetric Semiconductor with CuTe4 Tetrahedra and Ethane-like Si2Te6 Units. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 11656–11663. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b01608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykora R. E.; Ok K. M.; Halasyamani P. S.; Albrecht-Schmitt T. E. Structural Modulation of Molybdenyl Iodate Architectures by Alkali Metal Cations in AMoO3(IO3) (A = K, Rb, Cs): A Facile Route to New Polar Materials with Large SHG Responses. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 1951–1957. 10.1021/ja012190z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykora R. E.; Ok K. M.; Halasyamani P. S.; Wells D. M.; Albrecht-Schmitt T. E. New One-Dimensional Vanadyl Iodates: Hydrothermal Preparation, Structures, and NLO Properties of A[VO2(IO3)2] (A= K, Rb) and A[(VO)2(IO3)3O2] (A = NH4, Rb, Cs). Chem. Mater. 2002, 14, 2741–2749. 10.1021/cm020021n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Zhang D.; Liu L.; Zhang W.; Zhang J.; Cong Y.; Li X.; Halasyamani P. S. Cs2CdV2O6Cl2 and Cs3CdV4O12Br: two new non-centrosymmetric oxyhalides containing d0 and d10 cations and exhibiting second harmonic generation activity. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 10642–10651. 10.1039/c9dt02099c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitoudi Vagourdi E.; Müllner S.; Lemmens P.; Kremer R. K.; Johnsson M. Synthesis and Characterization of the Aurivillius Phase CoBi2O2F4. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 9115–9121. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b01118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang M.-L.; Hu C.-L.; Kong F.; Mao J.-G. BiFSeO3: An Excellent SHG Material Designed by Aliovalent Substitution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 9433–9436. 10.1021/jacs.6b06680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen S. D.; Yeon J.; Kim S.-H.; Halasyamani P. S. BiO(IO3): A New Polar Iodate that Exhibits an Aurivillius-Type (Bi2O2)2+ Layer and a Large SHG Response. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 12422–12425. 10.1021/ja205456b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z.; Yue Y.; Yao J.; Lin Z.; He R.; Hu Z. Bi2(IO4)(IO3)3: A New Potential Infrared Nonlinear Optical Material Containing [IO4]3– Anion. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 12818–12822. 10.1021/ic201991m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.; Meng X.; Gong P.; Yang L.; Lin Z.; Chen X.; Qin J. A2BiI5O15 (A = K+ or Rb+): two new promising nonlinear optical materials containing [I3O9]3 bridging anionic groups. J. Mater. Chem. C 2014, 2, 4057–4062. 10.1039/c4tc00264d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li P.-X.; Hu C.-L.; Xu X.; Wang R.-Y.; Sun C.-F.; Mao J.-G. Explorations of New Second-Order Nonlinear Optical Materials in the KI-MII -IV-O Systems. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 4599–4605. 10.1021/ic100234e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown I. D.; Altermatt D. Bond-Valence Parameters Obtained from a Systematic Analysis of the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Sci. 1985, 41, 244–247. 10.1107/s0108768185002063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown I. D.The chemical bond in Inorganic Chemistry: The Bond Valence Model; Oxford University Press: New York, 2002; Vol. 12, pp 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Selte K.; Kjekshus A.; Hartmann O.; Holme D.; Lamvik A.; Sunde E.; Sørensen N. A. Iodine Oxides Part III. The crystal Structure of I2O5. Acta Chem. Scand. 1970, 24, 1912–1924. 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.24-1912. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geller S.; Romo P.; Remeika J. P. Refinement of the structure of scandium sesquioxide. Z.Krist. 1967, 124, 136. 10.1524/zkri.1967.124.1-2.136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B.-P.; Hu C.-L.; Xu X.; Mao J.-G. New Series of Polar and Nonpolar Platinum Iodates A2Pt(IO3)6 (A =H3O, Na, K, Rb, Cs). Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 2481–2487. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b02859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunze G.; Hamid S. A. The Crystal Structure of a New KH(IO3)2 modification. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Crystallogr. Cryst. Chem. 1977, 33, 2795–2803. 10.1107/s0567740877009492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belokoneva E. L.; Dimitrova V. Synthesis and Crystal Structure of Pb3[IO3]2Cl4, a Representative of a New Iodate–Chloride Class of Compounds. Crystallogr. Rep. 2010, 55, 24–27. 10.1134/s1063774510010062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W.; Pan S.; Dong L.; Yang Z.; Dong X.; Chen Z.; Zhang M.; Zhang F.; Zhang F. Hydrothermal synthesis, growth, and properties of a new chloride iodate. J. Mol. Struct. 2013, 1049, 288–292. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2013.06.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B.-P.; Mao J.-G. Synthesis, crystal structure and optical properties of two new layered cadmium iodates: Cd(IO3)X (X = Cl, OH). J. Solid State Chem. 2014, 219, 185–190. 10.1016/j.jssc.2014.07.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz S. K.; Perry T. T. A Powder Technique for the Evaluation of Nonlinear Optical Materials. J. Appl. Phys. 1968, 39, 3798–3813. 10.1063/1.1656857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; Yu H.; Wu H.; Halasyamani P. S. Phase-Matching in Nonlinear Optical Compounds: A Materials Perspective. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 2655–2668. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b00243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kochuthresia T. C.; Gautier-Luneau I.; Vaidyan V. K.; Bushiri M. J. Raman and FTIr Spectral Investigations of Twinned M(IO3)2 (M = Mn, Ni, Co, and Zn) Crystals. J. Appl. Spectr. 2016, 82, 941–946. 10.1007/s10812-016-0209-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitoudi-Vagourdi E.; Rienmüller J.; Lemmens P.; Gnezdilov V.; Kremer R. K.; Johnsson M. Synthesis and Magnetic Properties of the KCu(IO3)3 compound with [CuO5]∞. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 15168–15174. 10.1021/acsomega.9b02064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APEX3, Version 2016.1-0; Bruker AXS Inc: Madison, WI, 2012.

- Sheldrick G. M.SADABS, Version 2008/1; Bruker AXS Inc, 2008.

- Sheldrick G. M. Crystal structure refinement withSHELXL. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. 10.1107/s2053229614024218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. SHELXT- Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Adv. 2015, 71, 3–8. 10.1107/s2053273314026370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergerhoff G.; Berndt M.; Brandenburg K. Evaluation of Crystallographic Data with the Program DIAMOND. J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. 1996, 101, 221–225. 10.6028/jres.101.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ok K. M.; Chi E. O.; Halasyamani P. S. Bulk characterization methods for non-centrosymmetric materials: second-harmonic generation, piezoelectricity, pyroelectricity, and ferroelectricity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 710–717. 10.1039/b511119f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.