Abstract

Introduction

This systematic literature review provides evidence concerning the association of school race/ethnic composition on mental health outcomes among adolescents (ages 11–17 years). A range of mental health outcomes were assessed (e.g., internalizing behaviors, psychotic symptoms) in order to broadly capture the relationship between school context on mental health and psychological wellbeing.

Methods

A search across six databases from 1990–2018 resulted in 13 articles from three countries (United States, United Kingdom, and the Netherlands) that met inclusion criteria following a two-step review of titles/abstracts and full-text.

Results

The existing research on school race/ethnic composition and mental health point to two distinct measures of school composition: density—the proportion of one race/ethnic group enrolled in a school, and diversity—an index capturing the range and size of all race/ethnic groups enrolled in a school. Overall, higher same race/ethnic peer density was associated with better mental health for all adolescents. In contrast, there was no overall strong evidence of mental health advantage in schools with increased diversity.

Conclusions

Theoretical and methodological considerations for future research towards strengthening causal inference, and implications for policies and practices concerning the mental health of adolescent-aged students are discussed.

Keywords: diversity, ethnic density, mental health, school context, school enrollment, school race/ethnic composition

INTRODUCTION

Although public school enrollment in the United States (U.S.) has become more racially and ethnically diverse, school integration has not kept pace with demographic change, widening school segregation nationwide (Camera, 2016; Nowicki, 2016; Orfield & Chungmei, 2007). Non-Hispanic white students remain the most segregated group as racial/ethnic minority students are funneled into highly segregated schools that are simultaneously challenged by economic deprivation and social disadvantage (Orfield, Frankenberg, Ee, & Kuscera, 2014; Orfield & Chungmei, 2007). While past research examining school racial/ethnic composition has focused on academic outcomes, there is growing attention on its impact on adolescent mental health. The primary goal of this study was to systematically examine the existing body of evidence in the U.S. and Europe on how school context as related to school racial/ethnic composition is associated with mental health outcomes, broadly, among adolescents.

Adolescence is a developmental period in which many different mental health problems emerge, including common mental disorders like depression and anxiety and more serious conditions like psychotic symptoms. For common disorders, racial/ethnic minority compared to non-Hispanic white adolescents consistently report poorer mental health outcomes in U.S. national studies (Alegria, Vallas, & Pumariega, 2010; Kann, 2014; Merikangas et al., 2010), as well as increased risk of chronicity and severity of disorder. A systematic review examining U.S. community and school samples found robust evidence of higher depression and anxiety among racial/ethnic minority adolescents compared to their non-Hispanic white peers (Anderson & Mayes, 2010). Moreover, racial/ethnic disparities in mental health may be larger than reported due to omission of physical somatization in screening (Lopez & Guarnaccia, 2000; Vega & Rumbaut, 1991) and systematic exclusion of immigrant, non-English speaking, and undocumented adolescent populations (Zambrana & Logie, 2000). This knowledge-base establishing racial/ethnic disparities in mental health burden among adolescents in the U.S. warrants research that furthers our understanding about the reasons behind these differences.

The school context may introduce unique experiences and challenges important to the mental health of diverse adolescents (Dunn, Milliren, Evans, Subramanian, & Richmond, 2015). In particular, school race/ethnic composition may be associated with racial/ethnic variation in mental health because these demographics shape the school context and environment including what resources are available in the school that can protect against or influence mental health outcomes for certain students. For example, having sufficient same-race/ethnicity peers may prevent feeling like an outsider and minimize the frequency of experiencing racism. Likewise, the benefits or risks of school race/ethnic composition associated with mental health may function differently for adolescents of different racial/ethnic backgrounds.

The extant empirical research on school race/ethnic composition and mental health has traditionally operationalized school composition in two distinct ways: diversity versus density. Diversity captures the full race/ethnic composition of a school by including the range and size of all race/ethnic groups enrolled in the school in its calculation (Juvonen, Nishina, & Graham, 2006). Higher scores on these diversity indices represent greater school race/ethnic diversity. Alternatively, race/ethnic density measures the proportion of a specific racial/ethnic group or category within a school such as the socio-political dominant or non-dominant group (e.g., non-Hispanic white students, racial/ethnic minority student enrollment), or the proportion of same-race/ethnicity peers enrolled in school (Walsemann, Bell, & Maitra, 2011).

The use of these measures in mental health research, however, point to different theoretical underpinnings on how the school context influences mental health outcomes for adolescents. As such, the use of diversity versus density measures to understand the impact of school composition on adolescent mental health lead to different educational policy implications regarding strategies for school enrollment and curriculum. Diversity frameworks suggest that having diverse school contexts increases the chances of making cross-ethnic friendships, balances power dynamics within schools across ethnic groups, and allows more chances of social adaptation for adolescents of diverse backgrounds (Graham, 2018). These benefits, in turn, are believed to lead to better mental health outcomes among students in schools with greater race/ethnic diversity in student enrollment.

In contrast, a majority/minority framework that uses a density measure of a socio-political dominant group as the referent involves power differentials within schools such as experienced racism, presence of social support, and development of strong ethnic identities (Becares, 2014; Shaw et al., 2012). The ethnic density hypothesis posits that racial/ethnic minority groups have better health in local contexts with greater density of minority populations because of greater social support from same race/ethnic group homophily and lower likelihood of experiencing discrimination (Becares, Nazroo, & Stafford, 2009; Bosqui, Hoy, & Shannon, 2014; Veling et al., 2008). Likewise, mental health outcomes are also hypothesized to worsen for racial/ethnic majority groups when density of racial/ethnic minority groups increase within these contexts. A similar framework can be applied to schools.

It is unclear if studies using these different measures of school race/ethnic composition result in similar findings/patterns and whether the association between school composition and mental health are similar for all race/ethnic groups. If using distinct measures of school racial/ethnic composition result in divergent findings of its impact on adolescent mental health, then each measure would have different implications for education policies. For instance, research on school race/ethnic diversity may lead to policies that increase the representation of ethnic minority groups in predominately non-Hispanic white schools, while research on school race/ethnic density may promote the inclusion of ethnic studies programming in schools.

Purpose of Current Review

School districts greatly consider policies that impact race/ethnic enrollment. Promoting racial/ethnic diversity within schools and decreasing segregation across schools are strategies towards promoting school integration and providing opportunities for cultural and ethnic exchange, thereby improving academic and economic trajectories for all students. However, a critical systematic review on how school race/ethnic composition may impact adolescent mental health has not been conducted and important questions loom: Is school race/ethnic composition associated with student mental health? What relationships emerge when diversity versus density measures of school race/ethnic composition are used to examine adolescent mental health? Is the association of school race/ethnic composition on mental health equal or different across racial/ethnic groups? Conducting a systematic literature review on the role of school race/ethnic composition on mental health can summarize the current evidence base of its general relationship, if similar patterns emerge across measures of diversity and density, and if any associations vary by student race/ethnicity. As the resulting studies in the current review come from U.S. and European contexts, the focus of the review is on U.S. and European countries as they represent high-income countries with large migrant and diverse populations. A systematic review that contributes to answering such questions will be useful to policy-makers in the U.S. and European contexts focused on school enrollment, education, and mental health of adolescents.

The goal for the current systematic literature review is to report on the current evidence to date concerning the association of school race/ethnic composition on adolescent mental health as one contributing factor of variation in mental health outcomes across race/ethnicity. We include a broad range of mental health outcomes recognizing that this area of research is growing and highly interdisciplinary spanning developmental psychology, education research, psychiatric epidemiology, and medical sociology. This review will provide important information on the overall association between school context and adolescent mental health and whether these patterns are consistent across students of different racial/ethnic backgrounds.

The resulting evidence base from this review should be evaluated within the context of school race/ethnic composition being one potentially important factor among other key contributing factors to adolescent mental health such as school and household socioeconomic status, school academic performance, and neighborhood effects. While these other key factors play a role in shaping the school context and adolescent mental health, the purpose of this systematic review was primarily to understand the total effect (overall impact) of school race/ethnic composition; in other words, does an association exist? In our summary of the findings, we briefly mention if these other key factors (e.g., school and household socioeconomic status) were included as covariates in each study. In the end, the review points to knowledge gaps, provides direction for future research, and discusses implications of the extant research on informing policies and practices focused on adolescent mental health and school enrollment.

METHODS

We examine published research from January 1, 1990 to December 1, 2018 that evaluates the effect of school race/ethnic composition on a range of mental health outcomes. A list of search keywords associated with school race/ethnic composition and the mental health outcomes of interest (see Appendix) was compiled to search five databases: PubMed, PsychINFO, Medline, SCOPUS, and ERIC (Table 1). The articles were selected for inclusion if they met the following criteria: (1) peer-reviewed published article; (2) published in English; (3) included middle- or high-school student samples (adolescents ages 11–17); (4) measured school race/ethnic composition (diversity index or ethnic density); and (5) had mental health outcomes, including mental disorders, internalizing or externalizing symptoms, measures of psychological well-being, and psychotic symptoms, as a primary or secondary outcome. As research in this area is limited, interdisciplinary, and still growing, our inclusion criteria for mental health was broad and covered a spectrum of conditions relating to general mental health and psychological well-being of students. Exclusion criteria included non-peer reviewed articles, abstracts, and non-English language studies. Excluded study samples were those among adults (18 years or older) or children (elementary school-aged or younger) as our research question focused on the developmental period of adolescence. Institutionalized adolescent populations (e.g. chronically ill, juvenile populations) were also excluded, as these populations were thought to not have traditional or sufficient time in a school setting in which school race/ethnic composition would have been meaningful.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| INCLUSION CRITERIA | |

| Publication dates | January 1, 1990 – December 1, 2018 |

| Language | English only |

| Publication status | Published, in-press, and online only peer-reviewed articles; book chapters; dissertations |

| Population | Study samples with adolescent-aged students (ages 11–17; middle- and high-school populations) must be included |

| Intervention/Exposure | A school-level measure of race/ethnic composition (e.g., density, diversity; same race/ethnicity peers; non-Hispanic white enrollment) |

| Comparison | Given the exposure requirement, the study should compare effects across school race/ethnic composition and not merely present a case study |

| Outcomes | Must include a mental health or behavioral outcome including psychological well-being or presence of mental disorder (e.g., depression) |

| Setting | Sample is not required to be school-based though likely given the exposure requirement |

| Study designs | Observational and experimental designs, quantitative and qualitative analyses |

| EXCLUSION CRITERIA | |

| Publication dates | Publications outside of date range January 1, 1990 – December 1, 2018 |

| Language | Non-English language |

| Publication status | Abstracts, conference presentations, non-peer-review, unpublished articles, commentaries |

| Population | Study samples without adolescent-aged students (ages 11–17) or with only children under 11 years old (elementary, pre-school, infants, toddlers, etc.), adults 18 years or older, or populations in college |

| Intervention/Exposure | Neighborhood-level measures of race/ethnic density or diversity |

| Comparison | Not applicable |

| Outcomes | Substance use disorders |

| Setting | Institutionalized populations (e.g. chronically ill or incarcerated youth) |

| Study designs | Anything other than included study design criteria |

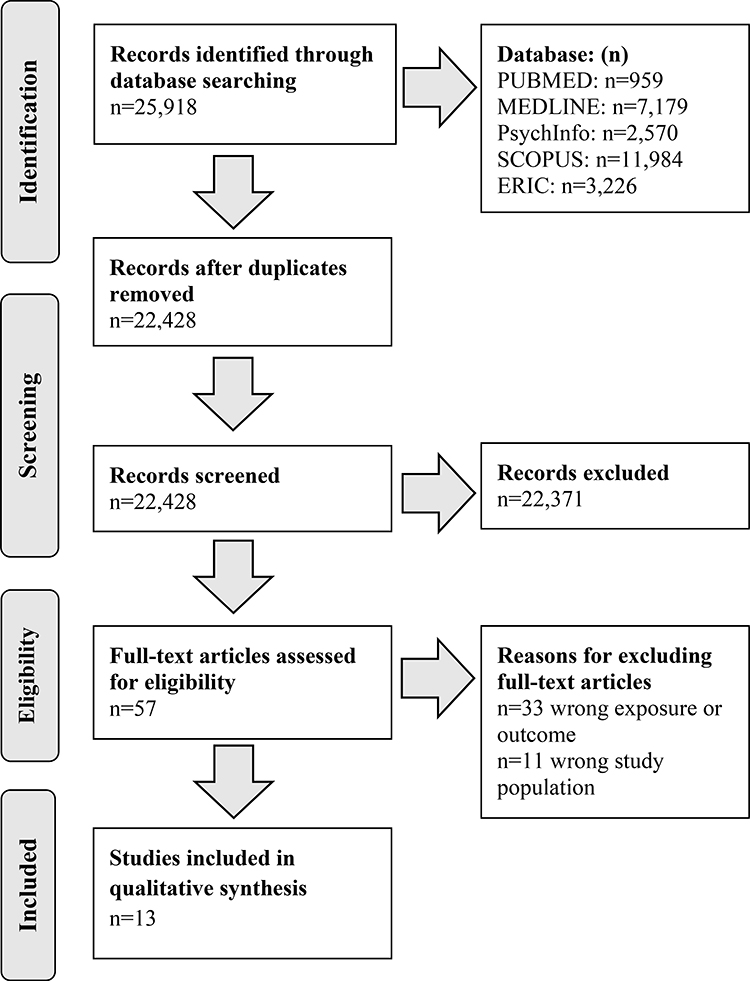

After removing duplicate articles (n=3,490), the database search yielded 22,428 unique articles (Figure 1). Each co-author screened all articles for inclusion in the final review in a two step review process of first titles and abstracts followed by a full-text scan. In step one, both reviewers screened article titles and abstracts for inclusion for full-text review, resulting in 57 articles. Full-text articles of each of the 57 articles passing title/abstract screening were added to an online database accessible to both reviewers. Discrepancies in inclusion selection during the full-text review were discussed until an agreement between the reviewers was met. Articles were excluded due to having the wrong exposure and/or outcome of interest (n=33) or the study population was outside the scope for this review (n=11). Thirteen articles met final inclusion criteria and their data were extracted to report study design, methods, findings and conclusions according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009). The paper is organized by how the exposure of school race/ethnic composition was measured, first describing studies that assessed school race/ethnic density and then those that assessed diversity. If the study stratified by sex, results are presented separately; otherwise, they are not discussed.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of database search.

RESULTS

We identified thirteen studies using longitudinal and cross-sectional designs published between 2002 and 2018 for inclusion (Table 2). While the majority included high-school adolescent samples (n=8), two studies sampled middle- and high-school students, and three studies included middle-school adolescents only. Five studies examined the effects of race/ethnic density in the U.S. with three using nationally representative school-based data—National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health; Crosnoe, 2009; Walsemann et al., 2011) and Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (Coutinho, Oswald, & Forness, 2002), and two using convenience samples among adolescent girls of African descent (Seaton & Carter, 2018) and Asian-American adolescents (Atkin, 2018). Three studies examined density effects using European data sources (Astell-Burt, Maynard, Lenguerrand, & Harding, 2012; Eilbracht, Stevens, Wigman, van Dorsselaer, & Vollebergh, 2015; Gieling, 2010). Finally, five studies evaluated diversity effects using convenience U.S.-based samples (Fisher, Reynolds, Hsu, Barnes, & Tyler, 2014; Graham, Bellmore, Nishina, & Juvonen, 2009; Juvonen, Kogachi, & Graham, 2018; Juvonen et al., 2006; Seaton & Yip, 2009). In summarizing each study’s results by race/ethnicity, we adhere to the labels used in each publication. In our discussion, we use the following labels: non-Hispanic white, Hispanic/Latino, non-Hispanic black, Asian American, Native American, and other race/ethnic group. As 10 of the 13 included studies used U.S.-based samples, these labels are consistent with the race/ethnic categories used in the U.S. Census. Nevertheless, terms like “Non-Hispanic white” can be considered similar to those used in European samples such as “Western/Caucasian” as these groups represent the sociohistorical dominant group in the local context.

Table 2.

Summary of peer-reviewed published articles included in the systematic review

| Study Author(s) and Year | Design, Data Source, Year, Sample Size, and Country | Characteristics of Adolescent Sample | Measurement of School Race/Ethnic Composition | Measurement of Mental Health Outcome | Study Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Astell-Burt et al., 2012 | Longitudinal DASHa 2003–2006 N=6,645 United Kingdom |

Ages 11–16 years from 51 schools in London; compared Indian, Pakistani & Bangladeshi, Black Caribbean, Nigerian & Ghanaian, and other African groups to White | Percent of same-ethnic group peers at school (density) and Herfindahl index (diversity) | Psychological well-being; Goodman’s Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire | Same-ethnic group density had positive effect on psychological well-being among other African students only. No diversity effects on psychological well-being were found. A significant effect of racism on psychological well-being for all groups was found. |

| Atkin et al., 2018 | Cross-sectional original data 2009–2010 N=367 United States |

High school students from two schools in a westcoast city; examined Asian-American students only | Percent of Asian student enrollment at school (density) | Psychological distress (depression, anxiety, stress); Depression Anxiety Stress scale | Internalization of the model minority myth occurred more often in predominantly non-Asian schools. The negative impact of internalizing the minority myth on psychological distress occurred in Asian-majority schools only. |

| Coutinho et al., 2002 | Cross-sectional DOEc 1994–1995 M=4,151 school districts N= 24+ million United States |

Students in secondary (and elementary) schools from one third of school districts across 50 states and District of Columbia; compared Black, Hispanic, American Indian, and Asian/Pacific Islander male and female groups, and White males, to White females | Percent of non-White enrollment at school (density) | Proportion of students identified in the emotional disturbances (ED) disability category in district data | Increasing school non-White enrollment was associated with higher ED among American Indian male and female students; however, significantly lower ED was found for Black males and lower ED trend for Black females and Hispanic males. |

| Crosnoe, 2009 | Longitudinal Add Healthd 1995–2002 M=47 schools N=1,119 United States |

Low-income public high school students; compared African American and Latino to White students | Percent of racial/ethnic minority student enrollment at school (density) | Three psychosocial indicators of negative self-image, perceived isolation, and depression; CES-D | High-SES schools with increasing ethnic minority enrollment saw decreases in negative self-image. Higher SES schools with decreasing ethnic minority enrollment saw higher psychosocial disadvantage. |

| Eilbracht et al., 2014 | Cross-sectional HBSCe 2005 M=21 schools N=4,375 Netherlands |

High school students from a random sample of 137 schools; compared Moroccan, Turkish, Surinamese, Antillean, and other non-Western groups to Dutch white | Percent of ethnic minority status students in class (density) | Mild psychotic experiences (e.g., paranoia, delusion, hallucination); Community Assessment of Psychotic Experiences | Increasing classroom ethnic density of non-Western students was associated with more paranoia symptoms among Dutch majority students. No ethnic density effect in other mild psychotic experiences were found. |

| Fisher et al., 2014 | Longitudinal original data 2005–2014 M=233 schools N=4,766 United States |

High school students in a large Midwestern county with a mix of urban, suburban, and rural areas; compared multiracial to African American and Caucasian groups | Simpson’s index (diversity) | Anxiety and depression; Modified 10-item state-trait anxiety and CES-D | Increasing school diversity associated with increasing mental health issues among Caucasian students only. No diversity effect in multiracial and African-American students were found. |

| Gieling et al., 2010 | Cross-sectional HBSCe 2001–2002 N=5,730 Netherlands |

High school students from a random sample of 137 schools; compared Moroccan, Turkish, Surinamese, Antillean, and other non-Western groups to Dutch white | Percent of ethnic minority status students in class (density) | Internalizing and externalizing problems; 101-item Youth Self-Report | Protective effect of classroom ethnic density of minority students on externalizing but not internalizing symptoms among ethnic minority students, with no effects for Dutch majority students. |

| Graham et al., 2009 | Longitudinal original data 2000–2003 N=2,003 United States |

Sixth-graders from 99 classrooms across 11 middle schools in Los Angeles; compared Latino (primarily Mexican origin) and African American subsample | Percent of same-ethnic group peers in class (density) and Simpson’s index (diversity) | Psychological maladjustment (latent construct using depressive symptoms and self-worth); CDI and HSPC | Self-blame mediates peer victimization effects on psychological maladjustment for the most populous group in low and high diversity classrooms, but not for the least populous groups in low diversity settings. |

| Juvonen et al., 2006 | Longitudinal original data 2000–2003 N=2,003 United States |

Sixth-graders from 99 classrooms across 11 middle schools in Los Angeles; compared Latino (primarily Mexican origin), African American, Asian, White, and multiethnic groups | Simpson’s index (diversity) | Loneliness and self=worth; Asher and Wheeler’s Loneliness and HSPC | Higher classroom diversity was associated with lower loneliness and higher self-worth. Higher school diversity was associated with lower loneliness. |

| Juvonen et al., 2018 | Longitudinal original data 2009–2012 N=4,302 United States |

Sixth-graders from 26 schools in middle socioeconomic status and working-class communities in Los Angeles; compared Latino, African American, Asian, and White students | Simpson’s index (diversity) | Loneliness; Asher and Wheeler’s Loneliness scale | Increased school diversity was associated with less loneliness for all students. |

| Seaton et al., 2009 | Cross-sectional original data Not reported N=252 United States |

High school students across 51 public schools in a large northeastern city; examined African American students only | Simpson’s index (diversity) | Depression, self-esteem, and satisfaction with life; CES-D, Rosenberg Self-Esteem, and Satisfaction with Life scales | Increased diversity was associated with more perceived individual and cultural racism. In high diversity schools, collective/institutional discrimination was associated with lower self-esteem. In low diverse schools, collective/institutional discrimination was associated with lower life satisfaction. |

| Seaton et al., 2018 | Cross-sectional original data Not reported N=217 United States |

High school students from a southeastern city; examined students of African descent only | Percent of African American student enrollment at school (density) | Depression; CES-D | Adolescent girls with late pubertal timing and strong Black identities saw greater depressive symptoms in non-majority Black schools only and not in majority-Black schools, suggesting psychological effects of pubertal timing are dependent on school race/ethnic composition. |

| Walsemann et al., 2011(Walsemann et al., 2011) | Longitudinal Add Healthd 1994 M=132 schools N=18,419 United States |

Nationally representative sample of adolescents in grades 7–12; compared Black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian and other race/ethnicity groups to White students | Percent of White student enrollment at school (density) | Depression and somatic symptoms; CES-D and 12-item Physical Symptom scale | Increasing White student enrollment was associated with increased depressive and somatic symptoms among Black students only. This association attenuated after controlling for perceived discrimination and school attachment. |

Abbreviations:

DASH “Determinants of Adolescent Social Well-being and Health study”

ECLS-K “Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten Cohort”

DOE “Department of Education”

Add Health “National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health”

HBSC “Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study”

CES-D “Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale”

CDI “Children’s Depression Inventory”

HSPC “Harter’ Self-Perception Profile for Children”

Overall, the existing body of evidence suggests that school race/ethnic composition is associated with adolescent mental health. However, the specific effects of school race/ethnic composition differ depending on whether a measure of density and/or diversity was utilized, and also how density and diversity was measured. Lastly, the relationship between race/ethnic composition and mental health varied across individual student race/ethnicity indicating that school contexts have differential associations with student mental health according to the student’s race/ethnic background.

Studies Examining School Race/Ethnic Density

Studies assessing school race/ethnic density and mental health operationalize the exposure in different ways. We summarize the results of these studies according to their measurement: proportion of (1) non-Hispanic white enrollment, (2) race/ethnic minority enrollment—the most common approach, and (3) same race/ethnicity peers.

Non-Hispanic White Density

Walsemann et al. (2011) used Add Health data to evaluate how density, assessed as proportion of non-Hispanic white enrollment, was associated with depression and somatic symptoms measured using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale and a physical symptom scale. After controlling for student, family, and school characteristics, including school socioeconomic status, non-Hispanic black compared to white youth had significantly higher depressive and somatic symptoms with increasing non-Hispanic white density (Walsemann et al., 2011). This pattern among non-Hispanic black students attenuated after controlling for perceived discrimination and school attachment, suggesting school climate fully explained the negative effect of non-Hispanic white density on mental health among non-Hispanic black students. Non-Hispanic white density was not associated with mental health among other race/ethnic groups net of controls.

Race/Ethnic Minority Density

Coutinho and colleagues (2002) examined cross-sectional data from the 1994–1995 National Center for Educational Statistics Common Core of Data and the Office for Civil Rights, which sampled one-third of school districts nationwide. The study examined the association between proportion of nonwhite enrollment with the identification of serious emotional disturbances (ED) in students in the disability category in district data, holding all other predictors at their median value including school and household socioeconomic status. Overall, nonwhite student enrollment was negatively correlated with ED. For Black boys, and to a lesser extent Black girls and Hispanic boys, ED identification significantly declined with increasing density of nonwhite students. However, ED identification dramatically increased with increasing nonwhite density for all American Indian students. These results suggest that schools with larger racial/ethnic minority enrollment protects against identification of ED for Black and Hispanic boys, but these protections do not extend to American Indian students. Though cross-sectional, the researchers suggest that these patterns likely stem from biases in school practices, particularly in schools with high socioeconomic status and non-Hispanic white enrollment.

Using Add Health data, Crosnoe (2009) examined low-income high-school students (e.g. family income <185% of the poverty line for household size) and the interaction between school socioeconomic status (SES) (high-, middle-, and low-SES) and individual race/ethnicity on three psychosocial constructs using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale and a measures of psychosocial indicators: negative self-image, perceived isolation, and depression. Race/ethnic density, treated as a covariate, was measured as race/ethnic minority enrollment. The analyses employed propensity scores to account for selection processes into schools using gender, immigration factors, school-related academic, cognitive, and social factors, past mental health issues, and family/household factors including socioeconomic status and closeness. Overall, increasing race/ethnic minority density was protective against negative self-image though unrelated to perceived isolation or depression, net of controls. African American low-income youth, and to a lesser extent Latino youth, saw greater psychosocial disadvantage in higher-SES schools with low minority enrollment, suggesting that low-income white students were the only group to demonstrate a mental health benefit in higher-SES school contexts.

Lastly, two studies using the Dutch Health Behavior in School-Aged Children survey assessed ethnic density effects on mild psychotic experiences and internalizing and externalizing symptoms, respectively, and after controlling for individual socioeconomic status (Eilbracht et al., 2015; Gieling, 2010). Ethnic density was measured as the classroom proportion of ethnic minority students (non-Western racial-ethnic groups; Dutch white majority students—referent category). Non-Western minority status was determined by whether the youth or their parent was born in a non-Western foreign country. Eilbracht et al. (2014) examined five measures of mild psychotic experiences using the Community Assessment of Psychotic Experiences scale (e.g. hallucinations, delusions, paranoia). The authors found that Dutch majority students had significantly higher paranoia symptoms as density of non-Western students increased, net of age, gender, education level, and household socioeconomic status. Though non-significant, ethnic minority students had lower symptoms.

Gieling et al. (2010) assessed the effect of ethnic density on internalizing (e.g. withdrawn, depressive-anxious symptoms) and externalizing (e.g. delinquent, aggressive behaviors) problems measured using the 101-item Youth Self-Report scale. The authors found lower externalizing problems among non-Western minority students with increasing density of non-Western students after adjusting for student (e.g., gender), family (e.g., socioeconomic status), and school factors (e.g., class size). About equal levels of externalizing problems were observed among all students when about two-thirds of the class identified as ethnic minority and only one-third as Dutch majority students. Density of non-Western students was not associated with internalizing problems regardless of student ethnic background. Collectively, this set of studies support the ethnic density hypothesis, which implies better mental health outcomes for racial/ethnic minority groups in contexts with higher representation of these groups.

Same Race/Ethnic Peer Density

Astell-Burt et al. (2012) assessed the association between school race/ethnic density, measured as the proportion of same race/ethnic peers in school, and psychological well-being from the Goodman’s 25-item Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire among a cohort of adolescents from London. After controlling for experienced racism and proportion of students eligible for free meals (a proxy for school-socioeconomic status), same-group density had a protective effect on psychological well-being for students identifying as Other African, but no effects were found for students of any other ethnic group (e.g., Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Black Caribbean, Nigerian, and Ghanaian).

Studies Examining School Race/Ethnic Diversity

Four studies operationalized school race/ethnic composition as a measure of diversity. Three U.S. studies utilized the Simpson’s diversity index, which assesses the probability that two randomly selected students are from different racial/ethnic groups. First, Fisher and colleagues (2014) combine national education archival data from 2005 to 2014 to examine diversity effects on depression and anxiety (aggregated as a latent variable of mental health issues from the 10-item state-trait anxiety and Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scales) among high-schoolers from a large Midwestern county. The index was measured using the percentage of Caucasian, African-American, and multiracial student enrollment. Higher scores indicated higher school diversity (e.g., no majority group), and lower scores indicated less diversity (i.e., predominant representation by one group). The authors found that high diversity was associated with significantly higher mental health risk among Caucasian students; in contrast, high diversity was protective of poor mental health among multiracial students though not statistically significant. Second, Juvonen et al. (2006) examined classroom and school diversity on loneliness and self-worth using the 10-item Children’s Depression Inventory and 6-item Harter’ Self-Perception Profile for Children scale, respectively, among a longitudinal sixth-grade sample from 2003 in Los Angeles. Higher classroom and school diversity were associated with lower loneliness and higher self-worth controlling for gender and student race/ethnicity. These findings were replicated in a larger cohort of middle-school students in 2006: self-reported loneliness decreased as school diversity increased (Juvonen et al., 2018). Analyses in the 2006 cohort found no moderating effects of ethnicity suggesting that diversity effects were the same across all race/ethnic groups in the cohort. Lastly, Astell-Burt and colleagues (2012) also assessed diversity effects in their London-based sample using the Herfindahl index, the sum of squared proportions of each race/ethnic group enrollment, on psychological well-being using Goodman’s 25-item Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Like their density results, diversity was not associated with psychological well-being, net of controls.

Indirect Assessments of School Race/Ethnic Composition

Four studies evaluated potential mediators of school race/ethnic composition on mental health. Seaton et al. (2009) used a convenience sample of African-American high-school students in a northeastern city to test the association between diversity, measured using the Simpson diversity index (e.g., the probability that two randomly selected students are from different racial/ethnic groups), and depression, self-esteem, and satisfaction with life, controlling for age, gender, and household socioeconomic status. Depression, self-esteem, and satisfaction with life were measured using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression, the Rosenberg Self-Esteem, and the Satisfaction with Life scales, respectively. Three measures of experienced racism (alphas = 0.83–0.87) were examined from the Index of Race-Related Stress scale: 1) individual racism (i.e. dominant group members engage in behaviors that feel denigrating to minority group members); 2) cultural racism (i.e. dominant group cultural history and practices are considered superior); and 3) collective/institutional racism (i.e. dominant group members’ negative attitudes are embedded in social institutions). Increasing school diversity was associated with higher perceptions of cultural racism and marginally so with individual racism; school diversity was not associated with institutional racism (Seaton & Yip, 2009). Collective/institutional racism was negatively associated with self-esteem, but not depressive symptoms, among those in high-diverse schools and less so in low-diverse schools. Additionally, high collective/institutional racism was associated with lower life satisfaction for students in low-diverse schools only. These findings allude to biases in school practices towards African-American students, which negatively affect their mental health; however, the authors note that these small and undetected effects were perhaps due to convenience sampling.

A second study by Seaton et al. (2018) examined if psychological effects (measured using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression) of pubertal timing depend on school race/ethnic composition, as well as Black identity, among a sample of high-school girls of African descent. Adolescent girls with late pubertal timing and strong Black identities saw greater depressive symptoms only in non-majority Black schools after controlling for parent education and marital status among other factors. This finding suggests that psychological effects of pubertal timing are dependent on varying school race/ethnic contexts for Black girls.

Another study tested the ethnic density hypothesis uniquely among Asian American high-school students (Atkin, 2018) assessing if school race/ethnic composition moderates the relationship between a student’s internalization of the model minority stereotype, the belief that Asian Americans have higher achievement and better upward mobility, and psychological distress, measured using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale. The study found that overall the internalization of the model minority stereotype was more often supported among Asian American students in predominantly non-Asian schools compared to majority-Asian schools net of household socioeconomic status. Moreover, this internalization of the model minority stereotype (upward mobility component only) was associated with increased depression and anxiety among students in majority-Asian schools. Overall, the study found the opposite of the ethnic density hypothesis in their Asian American sample: the internalization of the model minority stereotype was associated with higher psychological distress as density of Asian peers increased in the school context.

Finally, Graham et al. (2009) assessed the role of self-blame in mediating the relationship between self-reported peer victimization and psychological maladjustment using the Children’s Depression Inventory and self-worth dimension from Harter’ Self-Perception Profile for Children, and whether these pathways were moderated by classroom ethnic diversity: students of the more prevalent group in low-diverse classrooms, students of the less prevalent group in low-diverse classrooms, and high-diverse classrooms. The study found that peer victimization significantly increased psychological maladjustment through self-blame, and this pathway varied by school diversity. This pathway held true for students in high-diverse classrooms and those belonging to the most ethnically populous group, but not for ethnically isolated students in low-diverse classrooms.

DISCUSSION

The current systematic literature review describes observational studies (i.e., cross-sectional or cohort studies) that examined school race/ethnic composition, measured as diversity or density, on mental health. Thirteen studies published over twenty-five years met inclusion criteria, an indication that more research is needed, particularly as schools are becoming more diverse yet segregated over time. The evidence thus far supports the protective association of having higher same-race/ethnic group density for all students, with the exception of one study (Atkin, 2018). In contrast, there was no overall strong evidence of mental health advantage in schools with greater diversity. From the four studies examining the direct association of diversity, two studies found diversity to be protective of loneliness and self-worth (Juvonen et al., 2018; Juvonen et al., 2006) while one study found no association with mental health (Astell-Burt et al., 2012) and one study found a negative mental health effect among non-Hispanic white students only (Fisher et al., 2014). Furthermore, diversity was associated with greater chances of experiencing racism with implications particularly for students identifying as belonging to a racial/ethnic minority group (Seaton & Yip, 2009).

Collectively, these studies demonstrate that the school context matters to mental health, despite vast methodological differences in study designs, populations, and measures of school race/ethnic composition and mental health. The differences in methodologies across studies in this area of research strengthens the generalizability of our conclusions as the emerging patterns from these studies are robust to different disciplinary approaches and settings. Furthermore, the studies based in the U.S. (n=10) used large nationally representative and convenience samples of urban, suburban, and rural populations, likely making these findings generalizable to student populations across the U.S.; generalizability is limited for populations in Europe as studies occurred only once in the United Kingdom and twice in the Netherlands. To our knowledge, no other review has recognized this consistency in findings and generalizability across studies in the U.S., thereby contributing to the current knowledge base.

Potential Underlying Mechanisms

The reviewed studies revealed several potential mechanisms that could help explain the association between school race/ethnic composition and mental health. Mechanistic variables included experienced racism, self-esteem, social isolation, peer victimization, school attachment, and parental involvement. Three studies identified that school-based racism was more prevalent in diverse schools and generally lower in schools with higher same-group race/ethnic density. Racism towards racial/ethnic minority students may occur more frequently in diverse schools and/or schools with greater non-Hispanic white enrollment because negative or forced interactions between groups are more likely to occur. Consistent with literature demonstrating the deleterious effect of racism on health, school-based racism increased mental health risk (Astell-Burt et al., 2012; Seaton & Yip, 2009; Walsemann et al., 2011), and school attachment was shown to mediate density effects on mental health (Walsemann et al., 2011). These patterns help explain how segregated schools with high same-group density may promote school connectedness by adopting a strong school identity with the broader community, thereby reducing social isolation and racism, which in turn are protective of mental health.

Nevertheless, diverse school contexts may be beneficial to decreasing loneliness and increasing self-worth (Juvonen et al., 2018; Juvonen et al., 2006), and also reducing peer victimization (Graham et al., 2009). Diverse schools can be advantageous to mental health as they may promote equity and cultural awareness and celebrate cultural diversity through school programming (Graham, 2011; Juvonen et al., 2006), increasing opportunities for students to socially fit-in regardless of background (Graham, 2011; Juvonen et al., 2006; Wright, Giammarino, & Psrad, 1986). School programming and a school culture that embraces diversity, in turn, may balance power dynamics and facilitate the development of strong racial/ethnic identities that are protective against feelings of vulnerability and isolation (Berkel et al., 2010; Hughes, Witherspoon, Rivas-Drake, & West-Bey, 2009; Neblett, 2012; Stock et al., 2013). To test these hypothesized mechanisms with respect to the impact of racism on mental health across varying school contexts in terms of race/ethnic composition, future research should examine school and peer connectedness, availability of ethnic and cultural programming and studies, and general school climate, as these factors were not assessed comprehensively in the included studies.

Remaining Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps that remain following review of the current literature serve as a compelling call for further research that can inform school-based policy decisions. School-SES is strongly linked to race/ethnic composition in the U.S. given schools with predominantly race/ethnic minority enrollment face social and economic deprivation, including lower social capital and per pupil expenditure (Orfield & Chungmei, 2007). As a critical characteristic of a student’s school experience, only one study examined school-socioeconomic status (SES) and race/ethnic composition jointly (Crosnoe, 2009) while other studies controlled for school-SES as a covariate. While school-SES is one potential confounder that was to some extent adjusted for in some of the studies, potential remains for residual and/or unseen confounding. Therefore, school-SES and its cumulative impact with school race/ethnic composition on mental health needs further and consistent examination, and longitudinally, to improve causal inference.

A second area for future investigation is examining if divergent patterns in density and/or diversity emerge across race/ethnic groups. Only two of the included studies examined school race/ethnic composition using both measures of race/ethnic density and diversity in the same dataset (Astell-Burt et al., 2012; Graham et al., 2009); one of these studies examined if these patterns varied by self-reported race/ethnicity (Astell-Burt et al., 2012). As density and/or diversity may not benefit all students equally, assessing both density and diversity and their interactions with student race/ethnicity could help elucidate if divergent patterns emerge. Where relationships vary across race/ethnicity, within race/ethnic group analysis may help explain those patterns. The importance of this work about generally furthering our understanding of how and when race/ethnic density and diversity can have positive versus adverse effects on health has been recognized in new research (Williams et al., 2019).

Generalizability of the review findings could be expanded to include less-represented groups, such as gender and sexual minority students, and race/ethnic groups such as Native American and Asian American groups as well as the growing mixed-race and multi-ethnic student population, which were rarely assessed or collapsed into an “other race/ethnic group” category. Gaps also remain for within-group comparisons of these poorly studied populations, which could help further explain how race/ethnic composition influences mental health for specific underserved racial/ethnic groups. For instance, one study conducted within group analyses by language factors (Coutinho et al., 2002), and three studies analyzed within one ethnic group including non-Hispanic black (Seaton & Carter, 2018; Seaton & Yip, 2009) and Asian American (Atkin, 2018) adolescents.

Finally, other important mediating and modifiable factors to consider in future research are availability of ethnic studies programming, race/ethnic composition of teachers/staff, anti-bullying policies, and presence of school police within schools (Astell-Burt et al., 2012; Resnick et al., 1997; Seaton & Yip, 2009; Walsemann et al., 2011). No study assessed modifiable school factors of the availability of ethnic studies programs or general receptiveness of the school to programs that promote tolerance and inclusion. Likewise, the race/ethnic composition of teachers/staff was mostly excluded in the included studies. Such factors may buffer student race/ethnic composition effects on mental health by minimizing school-based racism and promoting inclusion and tolerance. Presence of, and interaction with, school police was never assessed.

Methodological Considerations for Future Research

Necessary methodological considerations can inform and increase the capacity of rigorous research in this area with the goal of providing data-driven policy recommendations. Longitudinal study designs would allow for the assessment of how changes in school race/ethnic composition throughout childhood and adolescence may impact mental health across the life course, and how these effects vary by student racial/ethnic background. Examining long-term effects can also add to our understanding about preparedness later in life, such as whether students in more ethnically homogenous schools encounter later problems adjusting to life in an ethnically diverse society. Further, adopting observational longitudinal, cohort studies while simultaneously assessing school race/ethnic composition and individual and school socioeconomic status would greatly improve causal inference. Research examining long-term race/ethnic composition effects could utilize a diversity index and a majority/minority framework with a density measure, as well as examine within race/ethnic group variation to identify patterns both across and within race/ethnic groups.

Our review suggests that each race/ethnic composition measure sheds light on different, yet important, mental health associations of students, as well as potential mechanisms for these associations. The identification of these mechanisms would help facilitate the development of specific interventions that promote a healthy school environment for students of different racial/ethnic backgrounds. The examination of other indices of racial/ethnic composition used to measure neighborhood segregation, including dissimilarity (i.e. proportion of race/ethnic groups needing to move across schools to achieve an even distribution) and isolation (i.e. degree of isolation felt in school due to school race/ethnic composition) may also be informative for understanding mechanisms in future research (Massey & Denton, 1988). Additionally, tapping into specific attributes of varying race/ethnic contexts by adding qualitatively different measures, including the availability of ethnic studies programming in the school and the race/ethnic composition of teachers/staff, may add intervenable dimensions to this area of research.

Most studies used validated measures of mental health although these were measured broadly and differently across the studies. One study used school records of emotional disturbance labeling for measuring the outcome (Coutinho et al., 2002) while all other studies included youth self-reports; no study included clinical or parent reports of youth mental health. Comprehensive measurement may include a combination of reports as discrepancies between reports may elucidate tendencies in identifying mental health problems by teachers and parents versus self-report. As about half of the studies focused on depression (e.g., Crosnoe, 2009), measures of anxiety and hyperactive-attention symptoms can extend results to other symptom-types. Research in this area that distinguishes between symptom type and number of mental health problems would be beneficial. Additionally, assessment of symptoms, disorders, and distress can contrast mental health versus wellness. Finally, the studies did not tap into a subjective assessment about youth’s perception of having a mental health problem. Future research could employ a comprehensive measurement of mental health status with these considerations.

With respect to study design, a challenge to this research includes the inability to conduct randomized controlled experiments of school assignment. School assignment is non-random in nature largely due to families having a choice in school assignment that is shaped by the neighborhoods in which families choose, and can afford, to live. These choices in neighborhoods and schools are also shaped by historical and current discriminatory and economic policies. Opportunities for natural experiments that make use of lotteries in bussing or school choice programs in select states and cities may allow for a naturally occurring random assignment of schools. Using a mixed-methods model of research including both qualitative inquiry that explores a student’s experience of school race/ethnic composition and quantitative data would help validate the finding that racial/ethnic minority students see improved mental health in schools with greater race/ethnic minority enrollment. Knowledge translation experts including communication specialists and use of policy briefs and lay reports should be involved in both study design and interpretation to better enable integration of research into school policy and practice.

Conclusion

The findings from this systematic review provide unique considerations for education policy. Efforts to improve integration (e.g. bussing programs) and redistricting of school districts may introduce challenges for students in terms of their mental health. Programs that bring low-income and race/ethnic minority youth to higher socioeconomic status schools with greater non-Hispanic white enrollment cause a loss of same-race/ethnicity peers that has shown to be protective of mental health. While mental health is one of many important outcomes to consider along with physical health and academic/economic achievements, this review demonstrates that ignoring the association between school context and mental health and psychosocial risks can have negative consequences particularly for racial/ethnic minority students. Policies in education should also consider mental health effects in addition to academic and economic achievement.

Increasing school race/ethnic integration promotes equity and provides an opportunity for cultural and ethnic exchange that better prepares youth for a more diverse and global society. Identifying the specific school race/ethnic composition required for mental health benefit for all students would be useful for developing enrollment strategies that consider mental health and educational outcomes. Aiming to balance resources, provide opportunities across schools towards better integration, and deter unequal treatment of students within schools are important considerations for prevention of mental illness. Efforts to increase race/ethnic diversity must simultaneously evaluate and address individual, cultural, and institutional racism. Strategies to address racism may include ensuring social and academic integration, increasing race/ethnic diversity of teachers and staff, including ethnic studies and programs in pedagogy, and introducing school-wide anti-stigma policies that address a range of mistreatment including racism. As evidenced by recent news reports (Anderson, 2016; Cunningham, 2016; Spencer, 2016), there is an urgent need to increase the evidence base for understanding mechanisms that lead to poor mental health and develop and evaluate school-based mental health interventions. More importantly, there is a need to consider policies that address inequities both across and within schools.

In conclusion, the current systematic literature review raises awareness of how race/ethnic composition is associated with mental health based on the published evidence to date. An understanding of this body of literature should be a core competency for adolescent mental health researchers and should be applied in education policy. This article provides greater depth of discussion of these studies as a collection, such that researchers, mental health providers, school stakeholders, and families and students can begin the process of addressing the mental health crisis in schools and the large inequities across and within schools patterned along racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic divides.

APPENDIX

Table 1.

Database search terms.

| School context | (school OR middle school OR middle-school OR high school OR high-school OR elementary school OR education OR educational setting OR academic OR academic setting OR college OR university OR universities OR class OR classroom OR student) |

| Exposure of interest | (race composition OR racial composition OR racial make-up OR racial make up OR ethnic composition OR ethnic make-up OR ethnic make up OR race/ethnicity composition OR racial/ethnic composition OR races/ethnicities OR diverse OR diversity OR diverse composition OR ethnic density OR ethnic densities) |

| Outcome of interest | MESH (PUBMED), EMTREE (MEDLINE and EMBASE), MAP (PSYCHINFO) terms for mental health outcomes; (Mental Health OR Psychological OR Psychological problem OR psychological disorder OR mental disorder OR mental health OR mental health problem OR Emotion OR mental illness OR internalizing behavior OR internalizing symptom OR externalizing behavior OR externalizing symptom OR problem behavior) OR (ADHD OR attention OR attention deficit disorder OR attention deficit hyperactive disorder OR attention deficit hyperactivity disorder OR attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder OR attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder OR hyperactivity OR impulsivity) OR (Depression OR depressive OR Depressive Disorder OR unipolar depression OR Depressive OR major depressive disorder OR major depression OR depressive symptom OR emotional depression OR emotional) OR (Mood Disorder OR mood OR Bipolar OR Affective Disorder OR Psychotic OR Affective Symptom OR Irritable Mood OR irritability OR mood change OR mood swing OR mood disturbance) OR (Nervousness OR Anxiety OR anxiety disorder OR anxiety state OR anxious state OR anxiety symptom) OR (Agoraphobia OR Panic Disorder OR panic OR Obsessive Compulsive Disorder OR OCD OR conduct OR conduct disorder) OR (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder OR psychological distress OR stress disorder OR post traumatic stress disorder OR PTSD OR hyper-vigilance) |

REFERENCES

- Alegria M, Vallas M, & Pumariega A (2010). Racial and ethnic disparities in pediatric mental health. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am, 19(4), 759–774. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2010.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E, & Mayes L (2010). Race/ethnicity and internalizing disorders in youth: a review. Clin Psychol Rev, 30(3), 338–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M, & Cardoza K (2016). Mental Health in Schools: A Hidden Crisis Affecting Millions of Students. NPR-ED: How Learning Happens. [Google Scholar]

- Astell-Burt T, Maynard M, Lenguerrand E, & Harding S (2012). Racism, ethnic density and psychological well-being through adolescence: Evidence from the Determinants of Adolescent Social Well-being and Health longitudinal study. Ethnicity & Health, 17(1–2), 71–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkin A, Yoo H, Jager J, & Yeh C (2018). Internalization of the Model Minority Myth, School Racial Composition, and Psychological Distress Among Asian American Adolescents. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 9(2), 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Becares L (2014). Ethnic density effects on psychological distress among Latino ethnic groups: an examination of hypothesized pathways. Health Place, 30, 177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becares L, Nazroo J, & Stafford M (2009). The buffering effects of ethnic density on experienced racism and health. Health and Place, 15(3), 700–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Knight G, Zeiders K, Tein J, Roosa M, Gonzales N, & Saenz D (2010). Discrimination and adjustment for Mexican American adolescents: A prospective examination of the benefits of culturally-related values. J Res Adolesc, 20(4), 893–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00668.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosqui T, Hoy K, & Shannon C (2014). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the ethnic density effect in psychotic disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49(4), 519–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camera L (2016). The New Segregation: school systems are more segregated than ever in this time of racial tension. US News & World Report. [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho M, Oswald D, & Forness S (2002). Gender and Sociodemographic Factors and the Disproportionate Identification of Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students with Emotional Disturbance. Behavioral Disorders, 27(2), 109–125. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R (2009). Low-Income Students and the Socioeconomic Composition of Public High Schools. American Sociological Review, 74(5), 709–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham P (2016). Is School Integration Necessary? US News & World Report. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn E, Milliren C, Evans C, Subramanian S, & Richmond T (2015). Disentangling the relative influence of schools and neighborhoods on adolescents’ risk for depressive symptoms. Am J Public Health, 105(4), 732–740. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilbracht L, Stevens G, Wigman J, van Dorsselaer S, & Vollebergh W (2015). Mild psychotic experiences among ethnic minority and majority adolescents and the role of ethnic density. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 50(7), 1029–1037. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0939-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher S, Reynolds J, Hsu W, Barnes J, & Tyler K (2014). Examining multiracial youth in context: Ethnic identity development and mental health outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(10), 1688–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gieling M, Vollebergh W, & van Dorsselaer S (2010). Ethnic density in school classes and adolescent mental health. Social Psychiatry Epidemiology, 45, 639–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S (2011). School racial/ethnic diversity and disparities in mental health and academic outcomes. Health disparities in youth and families: Research and applications, 57, 73–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S (2018). Race/Ethnicity and Social Adjustment of Adolescents: How (Not if) School Diversity Matters. Educational Psychologist, 53(2), 64–77. [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Bellmore A, Nishina A, & Juvonen J (2009). “It Must Be ‘Me’“: Ethnic Diversity and Attributions for Peer Victimization in Middle School. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(4), 487–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Witherspoon D, Rivas-Drake D, & West-Bey N (2009). Received ethnic-racial socialization messages and youths’ academic and behavioral outcomes: examining the mediating role of ethnic identity and self-esteem. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol, 15(2), 112–124. doi: 10.1037/a0015509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, Kogachi K, & Graham S (2018). When and How Do Students Benefit From Ethnic Diversity in Middle School? Child Development, 89(4), 1268–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, Nishina A, & Graham S (2006). Ethnic diversity and perceptions of safety in urban middle schools. Psychol Sci, 17(5), 393–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01718.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Kinchen S, & Shanklin S, et al. (2014). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance — United States, 2013. MMWR, 63(ss04), 1–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez S, & Guarnaccia P (2000). Cultural psychopathology: Uncovering the social world of mental illness. Annual Review of Psychology, 51, 571–598. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey D, & Denton N (1988). The Dimensions of Residential Segregation. Social Forces, 67(2), 281–315. doi: 10.2307/2579183 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas K, He J, Burstein M, et al. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication--Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 49(10), 980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, & Altman D (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol, 62(10), 1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neblett E, Rivas-Drake D, & Umaña-Taylor A (2012). The promise of racial and ethnic protective factors in promoting ethnic minority youth development. Child Development Perspectives, 6(3), 295–303. [Google Scholar]

- Nowicki J (2016). K-12 Education: Better Use of Information Could Help Agencies Identify Disparities and Address Racial Discrimination. Retrieved from http://www.gao.gov/assets/680/676745.pdf.

- Orfield G, Frankenberg E, Ee J, & Kuscera J (2014). Brown at 60: Great Progress, a Long Retreat and an Uncertain Future. Retrieved from: https://www.civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/brown-at-60-great-progress-a-long-retreat-and-an-uncertain-future/Brown-at-60-051814.pdf

- Orfield G, & Chungmei L (2007). Historic Reversals, Accelerating Resegregation, and the Need for New Integration Strategies. A report of the Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechos Civiles, The Univerity of California, Los Angeles. Retrieved from: https://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/historic-reversals-accelerating-resegregation-and-the-need-for-new-integration-strategies-1 [Google Scholar]

- Resnick M, et al. (1997). Protecting adolescents from harm. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA, 278(10), 823–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton E, & Carter R (2018). Pubertal Timing, Racial Identity, Neighborhood, and School Context Among Black Adolescent Females. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol, 24(1), 40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton E, & Yip T (2009). School and Neighborhood Contexts, Perceptions of Racial Discrimination, and Psychological Well-Being among African American Adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(2), 153–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw R, et al. (2012). Impact of ethnic density on adult mental disorders: narrative review. Br J Psychiatry, 201(1), 11–19. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer K (2016). New York Schools Wonder: How White Is Too White? The New York Times. [Google Scholar]

- Stock M, et al. (2013). Racial identification, racial composition, and substance use vulnerability among African American adolescents and young adults. Health Psychol, 32(3), 237–247. doi: 10.1037/a0030149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega W, & Rumbaut R (1991). Ethnic-Minorities and Mental-Health. Annual Review of Sociology, 17, 351–383. [Google Scholar]

- Veling W, et al. (2008). Ethnic density of neighborhoods and incidence of psychotic disorders among immigrants. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(1), 66–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsemann K, Bell B, & Maitra D (2011). The intersection of school racial composition and student race/ethnicity on adolescent depressive and somatic symptoms. Social Science and Medicine, 72(11), 1873–1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Lawrence JA, & Davis BA (2019). Racism and Health: Evidene and Needed Research. Annual Review of Public Health, 40, 105–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright J, Giammarino M, & Psrad H (1986). Social status in small groups: Individual-group similarity and the social “misfit”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 523–536. [Google Scholar]

- Zambrana R, & Logie L (2000). Latino child health: need for inclusion in the US national discourse. Am J Public Health, 90(12), 1827–1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]