Abstract

Background: Albumin 25% has been studied and has demonstrated benefit in a limited number of patient populations. The use of albumin 25% is associated with higher costs compared with crystalloid therapy. The aim of this study was to describe the prescribing practices of albumin 25% at a tertiary-care medical center and identify opportunities for restriction criteria related to its use to help generate cost savings. Methods: This evaluation was a retrospective, noninterventional, descriptive study of albumin 25% use between June 2015 and February 2016. Inclusion criteria consisted of patients ≥18 years old and who received at least one dose of albumin 25% while admitted to a Cleveland Clinic main campus intensive care unit (ICU). Inclusion was restricted to 150 randomly selected patients. Results: A total of 539 albumin 25% orders were placed for the 150 included patients. The cardiovascular ICU more frequently prescribed albumin 25% compared with the medical, surgical, neurosciences, and coronary ICUs (51% vs 23% vs 11% vs 9% vs 6%, respectively). Although the cardiovascular surgery ICU most frequently prescribed albumin 25% compared with other ICUs, the medical ICU prescribed a larger total quantity of albumin 25% compared with the cardiovascular, surgical, neurosciences, and coronary ICUs (8705 g vs 7275 g vs 3205 g vs 2162 g vs 625 g, respectively). The majority of patients (61%) did not have an indication listed for albumin 25% use and only 9% of patients were prescribed for indications supported by primary literature. Of the patients prescribed albumin for other indications not supported by primary literature (30%), the most common reasons for albumin 25% were hypotension, acute kidney injury, and volume resuscitation. The median cost per patient of albumin 25% was $417 with a total cost of $122 164 for the cohort. Only 19% of the total cost aligned with dosing regimens evaluated in primary literature. Conclusion: Prescribing patterns of albumin 25% at a tertiary academic medical center do not align with indications supported by primary literature. These findings identified a major opportunity for prescriber education and implementation of restriction criteria to target cost savings.

Keywords: albumin, critical care, cost avoidance, formulary restrictions, prescribing patterns

Background

Albumin is a colloid fluid frequently prescribed in the intensive care unit (ICU) for a variety of indications, primarily volume expansion and fluid resuscitation. Albumin, compared with crystalloid therapy, has not demonstrated a benefit in regard to hospital length of stay, duration of mechanical ventilation, or mortality when used for volume resuscitation or albumin supplementation.1-3 The Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines provide a weak recommendation, due to low-quality evidence, for albumin therapy for initial resuscitation and subsequent intravascular volume repletion in patients with sepsis or septic shock after they have received large quantities of crystalloid therapy, suggesting that albumin 5% would be preferred in this setting.4 Albumin is available in many concentrations and the more concentrated 25% has been studied for a few specific indications in which it may provide benefit compared with 5% albumin. The indications include vasospasm post-subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), large-volume paracentesis, hepatorenal syndrome (HRS), spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), and intradialytic hypotension.5 The American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) supports the use of albumin for the purpose of volume expansion during vasospasm post-SAH to prevent delayed cerebral ischemia.6 In the setting of end-stage liver disease, the use of albumin for large-volume paracentesis, HRS, and SBP is recommended by the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) to improve intravascular volume and renal impairment and reduce mortality.7 By increasing intravascular volume without administrating a large fluid volume, albumin 25% has been effective in correcting intradialytic hypotension, a common complication of dialysis.8

In an era when health care costs are under scrutiny, the appropriate use of albumin must be evaluated. The substantial increase in expense coupled with few indications demonstrating superior outcomes with albumin warrant the identification of opportunities to use crystalloids as an alternative. Given the concern for increased costs associated with albumin 25% use and limited indications which support its use in critically ill patients, we sought to evaluate the prescribing practices of albumin 25% at a large academic tertiary-care center and evaluate opportunities for cost avoidance.

Method

This study was a retrospective, noninterventional, descriptive study of albumin 25% use between June 1, 2015, and February 28, 2016, conducted at the Cleveland Clinic main campus, a 1400 bed, tertiary-care, nonprofit, academic medical center. The study was approved by the Cleveland Clinic institutional review board prior to data collection. An electronic medical record (EMR) was utilized for data collection and abstraction. The ICUs evaluated for albumin 25% utilization were the medical ICU (MICU), neurosciences ICU (NICU), surgical ICU (SICU), coronary ICU (CCU), and cardiovascular surgery ICU (CVICU). Patients were included in the study if they were ≥18 years old and received at least one dose of albumin 25% while admitted to an included Cleveland Clinic ICU. Exclusion criteria included patients without administration of albumin 25% documented in the EMR and patients not admitted to the ICU at the time of albumin administration. A total of 150 patients were randomly selected to be evaluated, with a proportional sample of patients from each ICU to be evaluated based on overall albumin 25% usage during the allotted time frame. A random sample generator was used to identify the 150 charts to be evaluated. We chose to evaluate 150 charts for feasibility and felt this sample would allow us to accurately describe our prescribing practices.

Baseline demographics including race, gender, age, weight, albumin level, comorbidities, ICU location, and medication, fluid, and blood product administration surrounding albumin administration were collected to describe the patient population. To describe albumin-prescribing practices, the dose, frequency, total number of doses prescribed, and indication for use were collected. Pharmacist documentation during order verification and progress notes entered by the prescribers were used to identify the indication for albumin therapy.

The primary objective of the study was to describe the prescribing patterns and indications for use of albumin 25% within the ICUs at the Cleveland Clinic. The secondary objectives were to compare the documented indications and dosing regimens for albumin 25% with indications and dosing regimens supported by primary literature or treatment guidelines and evaluate the cost associated with albumin 25% use. For this analysis, the following indications and dosing regimens were considered as supported by primary literature: HRS 1 g/kg on day 1 (≤100 g) followed by 20 to 40 g daily for ≤14 days; SBP 1.5 g/kg on day 1 followed by 1 g/kg on day 3; 8 to 10 g/L removed during large-volume paracentesis (≥5 L removed) once; intradialytic hypotension 25 g once with dialysis; and vasospasm post-SAH 1.25 g/kg daily for 7 days. During the time of our study period, our institution did not have an albumin 25% prescribing guideline, and albumin 25% prescribing was only restricted in the SICU, where prescribing was restricted to staff, mid-level practitioners, and fellows only. We applied cost data to our findings using the 2018 average wholesale price.9 Descriptive statistics were used as appropriate.

Results

A total of 2066 patients were identified during our study period, with the following ICU distribution: MICU (n = 292, 14.1%), SICU (n = 157, 7.7%), NICU (n = 72, 3.5%), CCU (n = 36, 1.7%), and CVICU (n = 1509, 73.0%). Of these patients, 150 patients were randomly selected to evaluate a proportion of patients from each ICU. Baseline characteristics are described in Table 1. The median (interquartile range [IQR]) ICU length of stay was 10 (4-27) days and the median (IQR) hospital length of stay was 23 (12-41) days. The majority of patients were mechanically ventilated (n = 120, 80%) and hospital mortality was 17% (n = 26).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics.

| Variable | Subjects (n = 150) |

|---|---|

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 130 (87) |

| Black | 12 (8) |

| Asian | 3 (2) |

| Multiracial | 1 (0.5) |

| American Indian | 1 (0.5) |

| Unknown | 3 (2) |

| Gender, male, n (%) | 82 (55) |

| Age,a year | 64 (53-73) |

| Weight,a kg | 86 (74-103) |

| Albumin,a g/dL | 2.6 (2.25-3.05) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 47 (31) |

| Acute kidney injury | 59 (39) |

| Congestive heart failure | 56 (37) |

| End-stage liver disease | 34 (23) |

| Sepsis | 17 (11) |

| ICU location, n (%) | |

| Neurosciences ICU | 13 (9) |

| Medical ICU | 34 (23) |

| Surgical ICU | 17 (11) |

| Coronary ICU | 9 (6) |

| Cardiovascular surgery ICU | 77 (51) |

| Medications/fluids/blood products administered within 2 hours of albumin 25% administration | |

| Medications | |

| Loop diuretics | 36 (24) |

| Vasopressors | 109 (73) |

| Other fluids | 74 (49) |

| 0.9% or 0.45% sodium chloride | 54 (36) |

| Dextrose 5% or 10% water | 8 (5) |

| Lactated Ringer’s | 16 (11) |

| Sodium bicarbonate | 1 (0.5) |

| Blood products | |

| Packed red blood cells | 39 (26) |

| Platelets | 10 (7) |

| Fresh frozen plasma | 24 (16) |

Note. ICU = intensive care unit.

Median (interquartile range).

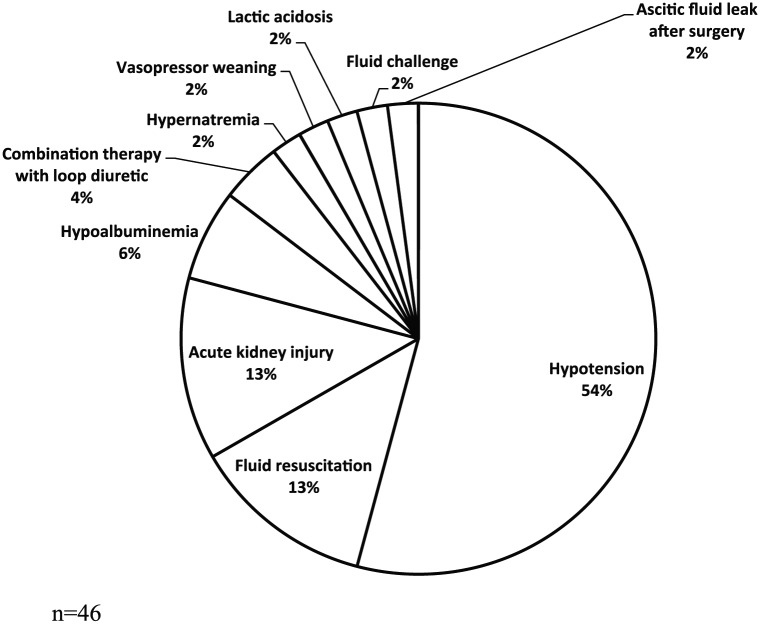

The documented indications for albumin 25% use and quantity received are listed in Table 2. The CVICU more commonly prescribed albumin 25% compared with other ICUs, but the MICU prescribed the greatest quantity in grams per patient compared with other ICUs. The majority of patients (61%) did not have a documented indication associated with albumin 25% use. Only 9% of patients were prescribed albumin 25% for indications supported by primary literature. The indications documented for albumin 25% use which were outside of those indications supported by primary literature are shown in Figure 1. The most common “other” indication for albumin therapy was hypotension (n = 25, 54%) followed by acute kidney injury (AKI) (n = 6, 13%) and fluid resuscitation (n = 6, 13%). Albumin 25% was primarily prescribed by staff physicians (n = 62, 41%), followed by fellows (n = 36, 24%), mid-levels (n = 31, 21%) and residents (n = 21, 14%).

Table 2.

Albumin Prescribing Information.

| ICU | Indication, n (%) |

Total administered, g | Dose per patient,a g | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRS | SBP | ID hypotension | LVP | Other | Unknown | Total | |||

| NICU | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 8 (62) | 4 (31) | 13 (9) | 2162 | 75 (37.5-125) |

| MICU | 4 (12) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 3 (9) | 15 (44) | 10 (29) | 34 (23) | 8705 | 187.5 (100-325) |

| SICU | 2 (12) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 9 (53) | 5 (29) | 17 (11) | 3205 | 50 (25-200) |

| CCU | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (56) | 4 (44) | 9 (6) | 625 | 50 (25-87.5) |

| CVICU | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9 (12) | 68 (88) | 77 (51) | 7275 | 50 (25-118.75) |

| Total | 6 (3.5) | 2 (1.5) | 1 (1) | 4 (3) | 46 (30) | 92 (61) | 150 (100) | 21 972 | 75 (37.5-175) |

Note. ICU = intensive care unit; HRS = hepatorenal syndrome; SBP = spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; ID = intradialytic; LVP = large-volume paracentesis; NICU = neurosciences intensive care unit; MICU = medical intensive care unit; SICU = surgical intensive care unit; CCU = coronary intensive care unit; CVICU = cardiovascular surgery intensive care unit.

Median (interquartile range).

Figure 1.

Documented “other” indications for albumin therapy.

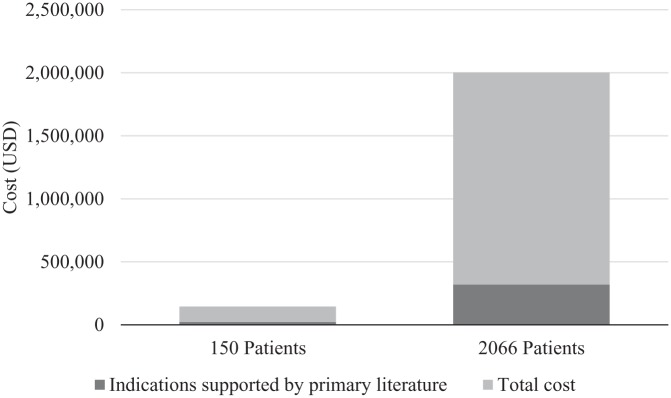

The cost associated with albumin 25% use during our study period is reported in Figure 2. The median (IQR) cost per patient of albumin 25% was $417 (209-973) with a total cost of $122 164 for the total amount of albumin 25% administered to the 150 patients. The total cost of therapy for indications supported by primary literature was $23 283, which is 19% of the total cost spent on albumin 25% during this evaluation. When extrapolating cost to the entire ICU sample of 2066 patients who received albumin 25% during our 9-month study time frame, the total cost was $1 682 612 with $319 696 spent on indications supported by primary literature.

Figure 2.

Cost of therapy.

Discussion

The results of our study demonstrate that at a large, academic medical center, the prescribing practices of albumin 25% in critically ill patients are inconsistent among ICU prescribers. Indications for albumin 25% are not well documented and indications, when documented, are not supported by primary literature. The most common documented indications were hypotension, HRS, AKI, and volume resuscitation. A total of $98 893 was spent on albumin 25% therapy which did not have a documented indication for use or the indication was one in which there is a lack of primary literature supporting the indication. Although this study only evaluated 150 random patients during a 9-month time period, if we extrapolate these data to evaluate an 1-year time period, our institution spends $1 817 222 per year on albumin 25% for indications which are not documented or unsupported by primary literature, highlighting a major opportunity for cost avoidance.

Challenges regarding inappropriate prescribing of albumin are not unique to our institution. An observational study conducted at 15 academic medical centers reviewed 969 cases to describe the prescribing practices of albumin and other nonprotein colloids. In this study, albumin was administered in 83% of the evaluated cases with the majority of cases receiving albumin for shock and cardiac surgery. Investigators deemed 76% of patients inappropriately received colloid therapy based on the current guidelines at the time of the study resulting in $124 939 of inappropriate health care spending.10 A single-center study which evaluated 60 ICU patients who received albumin therapy found that the most common indications for albumin use was volume expansion (65%), intraoperative fluid resuscitation (13%), and increased urine output (10%), all indications not supported by primary literature or the guidelines at the time of the study.11 Finally, a recently published survey of cardiothoracic surgeons, anesthesiologists, and perfusionists found that in the cardiothoracic surgery setting, albumin is most commonly prescribed for volume expansion according to volume status indicators like blood pressure, urine output, cardiac output, and central venous pressure, but significant variability exists among prescribers.12 These studies demonstrate a widespread problem in terms of inappropriate prescribing of albumin therapy and significant variability in prescribing practices.

Our evaluation highlighted many opportunities for improvement regarding albumin 25% prescribing at our institution. Although the MICU prescribed a greater quantity of albumin, they more often prescribed albumin for HRS, SBP, and large-volume paracentesis, which are indications supported by primary literature and require higher weight or volume-dependent doses.7 The CVICU most commonly ordered albumin 25% as single 25 g doses following cardiac surgery, in which although most indications for use were undocumented, they are likely in line with the cardiothoracic surgery practices at other institutions for volume expansion.12 Given that 73% of patients were receiving vasopressors and 49% of patients were receiving crystalloid therapy within 2 hours of albumin administration suggests that many of the undocumented indications for albumin use was likely fluid resuscitation and hypotension. This evaluation helped to identify our varying prescribing practices across our ICUs and allows for better focused efforts for cost-containment including implementation of restriction criteria and provider education.

Opportunities for cost reduction while maintaining quality care has become a priority for many health systems. The American Board of Internal Medicine’s Choosing Wisely campaign, in conjunction with the Critical Care Societies Collaborative, published a list of recommendations to avoid unnecessary medical tests, treatments, and procedures, but there is an opportunity to add medications, such as albumin, to this list.13 A single-center study evaluating pharmacy-related ICU costs and opportunities for cost-containment found that albumin remained at the top of the list in terms of ICU drug expenditure over a 10-year period. Intensive care unit drug costs accounted for an average of 31% of total hospital drug costs and albumin on average accounted for 6.5% of the ICU drug costs.14 The authors suggest evaluating indications for high-cost therapies, identify cost-effective alternatives for these therapies, and utilize clinical pharmacists to help provide education regarding section of most cost-effective treatment options. One strategy that may help with cost-containment while ensuring quality care is implementation of fluid stewardship. We should place the same degree of scrutiny on choice of fluid, dose of fluid, and duration of fluid that we do on medication therapies. A more conscious selection of fluid therapy may also result in less overall albumin 25% use.15

Our institution does not currently have restrictions in place for the utilization of albumin 25% with the exception of provider-level restrictions in the SICU, but based on the results of our study, there are many opportunities for albumin stewardship. Although there is limited literature providing guidance for implementation of albumin stewardship strategies, prior studies have demonstrated success with the implementation of stewardship strategies involving internal guidelines for use. A single-center study in Paris found that the introduction of internal guidelines for albumin use led to a 70% reduction in albumin prescribing and a yearly savings of $57 208.16 A 2003 Italian study found similar results in 2 hospitals with an average decreased albumin utilization in one hospital of 8.2% and 75.6% in the second hospital. This decrease resulted in a cost savings of €17 000 for the first hospital and €200 000 for the second hospital.17 A study of SICU patients at a tertiary teaching hospital found that the introduction of albumin restriction criteria resulted in a 54% decrease in albumin use, 56% reduction in cost, and had no negative impact on ICU length of stay or mortality.3 Finally, a recently published study evaluating the impact of restriction criteria for albumin prescribing in a single-center cardiac surgery ICU found that the introduction of restriction criteria reduced utilization of albumin by 64% and resulted in a monthly cost savings of $45 000. In addition to reduced albumin utilization and cost, there was a trend toward decreased mechanical ventilation days and there was no impact on transfusion requirements, length of stay, or mortality suggesting that no harm was caused by introducing albumin utilization restrictions.18 The findings from these studies demonstrate that the introduction of guidelines for appropriate albumin utilization can reduce albumin consumption and associated health care costs, without decreasing the quality of care provided to patients.

The introduction of restriction criteria will take a multidisciplinary approach and the support of ICU leadership to develop an internal guideline for the appropriate utilization of albumin 25% in the ICUs at our institution. This should include appropriate indications for albumin 25% use and recommended dosing regimens for these indications. Following the development of an internal guideline, educational efforts should be made to educate prescribers about these new guidelines. Based on the results of our study, it is unlikely that placing restrictions on the level of ordering provider will impact utilization, as the majority of the albumin orders we evaluated were placed by staff physicians. Therefore, we first sought to achieve more appropriate albumin 25% usage by providing prescriber education regarding the appropriate indications for albumin 25% use. Educational efforts should be ongoing to continuously remind prescribers about the appropriate use of albumin 25%. Technology should also be leveraged to aid in implementing restriction criteria by embedding decision support tools into our computer physician order entry (CPOE) system to help with adherence to these restriction criteria.19,20 If the restriction criteria are embedded within the CPOE system, this can make the tracking of albumin utilization and the reassessment of our interventions easier. Any strategy that is implemented to encourage appropriate use of high-cost medications should be evaluated to ensure the strategy has achieved the desired outcome and continual education should occur to ensure success.

Despite this evaluation being a large descriptive analysis, there are many limitations. This was a single-center study only evaluating ICU patients who received albumin 25%; therefore, our results may lack external validity and may not be applicable to noncritically ill patients or other concentrations of albumin. However, our results add to a growing body of literature evaluating inappropriate utilization of high-cost medications.14 Due to the retrospective nature of this study, our data relied solely on accurate documentation within the electronic medication record, especially information regarding the indications for which albumin 25% was prescribed was manually collected. Unfortunately, although an indication for use was not required to be documented when prescribed or verified by pharmacy, the indication was often unknown. This study design may have limited our ability to identify indications that were actually supported by primary literature, but we were not able to ascertain via retrospective review. Finally, based on albumin 25% utilization in the 150 patients we manually evaluated, we extrapolated this utilization to all of the patients during this time period, which may have over or underestimated our actual albumin 25% utilization for the period and the indications for which it was prescribed.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that the indications for albumin 25% use in critically ill patients at a large, academic medical center is often not well documented or, if documented, not prescribed for an indication supported by primary literature. The results highlight an opportunity for provider education, implementation of restriction criteria, and cost avoidance. This evaluation should be re-performed after stewardship efforts have been implemented.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Finfer S, Bellomo R, Boyce N, French J, Myburgh J, Norton R; SAFE Study Investigators. A comparison of albumin and saline for fluid resuscitation in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(22):2247-2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Caironi P, Tognoni G, Masson S, et al. Albumin replacement in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(15):1412-1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Charles A, Purtill M, Dickinson S, et al. Albumin use guidelines and outcome in a surgical intensive care unit. Arch Surg. 2008;143(10):935-939; discussion 939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(3):304-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. American Thoracic Society. Evidence-based colloid use in the critically ill: American Thoracic Society Consensus Statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(11):1247-1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Connolly ES, Jr, Rabinstein AA, Carhuapoma JR, et al. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2012;43(6):1711-1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Runyon BA. Introduction to the revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Practice Guideline management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis 2012. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1651-1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Van der Sande FM, Luik AJ, Kooman JP, Verstappen V, Leunissen KM. Effect of intravenous fluids on blood pressure course during hemodialysis in hypotensive-prone patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11(3):550-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Redbook Online [online database]. Greenwood Village, CO: Truven Health Analytics; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yim JM, Vermeulen LC, Erstad BL, Matuszewski KA, Burnett DA, Vlasses PH. Albumin and nonprotein colloid solution use in US academic health centers. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(22):2450-2455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gales BJ, Erstad BL. Albumin audit results and guidelines for use. J Pharm Technol. 1992;8(3):125-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aronson S, Nisbet P, Bunke M. Fluid resuscitation practices in cardiac surgery patients in the USA: a survey of health care providers. Perioper Med. 2017;6:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Angus DC, Deutschman CS, Hall JB, Wilson KC, Munro CL, Hill NS. Choosing wisely(R) in critical care: maximizing value in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(11):2437-2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Altawalbeh SM, Saul MI, Seybert AL, Thorpe JM, Kane-Gill SL. Intensive care unit drug costs in the context of total hospital drug expenditures with suggestions for targeted cost containment efforts. J Crit Care. 2018;44:77-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Malbrain M, Van Regenmortel N, Saugel B, et al. Principles of fluid management and stewardship in septic shock: it is time to consider the four D’s and the four phases of fluid therapy. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8(1):66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Debrix I, Combeau D, Stephan F, Benomar A, Becker A. Clinical practice guidelines for the use of albumin: results of a drug use evaluation in a Paris hospital. Tenon Hospital Paris. Pharm World Sci. 1999;21(1):11-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Martelli A, Strada P, Cagliani I, Brambilla G. Guidelines for the clinical use of albumin: comparison of use in two Italian hospitals and a third hospital without guidelines. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2003;64(9):676-684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rabin J, Meyenburg T, Lowery AV, Rouse M, Gammie JS, Herr D. Restricted albumin utilization is safe and cost effective in a cardiac surgery intensive care unit. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104(1):42-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Niazkhani Z, Pirnejad H, Berg M, Aarts J. The impact of computerized provider order entry systems on inpatient clinical workflow: a literature review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16(4):539-549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Baysari MT, Lehnbom EC, Li L, Hargreaves A, Day RO, Westbrook JI. The effectiveness of information technology to improve antimicrobial prescribing in hospitals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Med Inform. 2016;92:15-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]