Abstract

Background

Chlorpromazine is an aliphatic phenothiazine, which is one of the widely‐used typical antipsychotic drugs. Chlorpromazine is reliable for its efficacy and one of the most tested first generation antipsychotic drugs. It has been used as a ‘gold standard’ to compare the efficacy of older and newer antipsychotic drugs. Expensive new generation drugs are heavily marketed worldwide as a better treatment for schizophrenia, but this may not be the case and an unnecessary drain on very limited resources.

Objectives

To compare the effects of chlorpromazine with atypical or second generation antipsychotic drugs, for the treatment of people with schizophrenia.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Trials Register up to 23 September 2013.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared chlorpromazine with any other atypical antipsychotic drugs for treating people with schizophrenia. Adults (as defined in each trial) diagnosed with schizophrenia, including schizophreniform, schizoaffective and delusional disorders were included in this review.

Data collection and analysis

At least two review authors independently screened the articles identified in the literature search against the inclusion criteria and extracted data from included trials. For homogeneous dichotomous data, we calculated the risk ratio (RR) and the 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For continuous data, we determined the mean difference (MD) values and 95% CIs. We assessed the risk of bias in included studies and rated the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach.

Main results

This review includes 71 studies comparing chlorpromazine to olanzapine, risperidone or quetiapine. None of the included trials reported any data on economic costs.

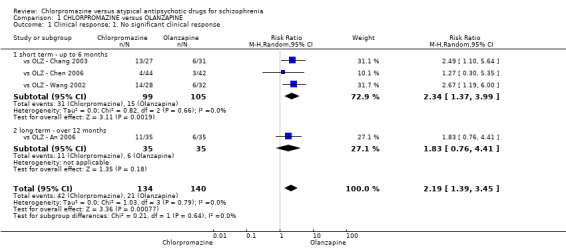

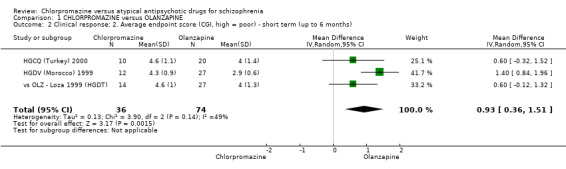

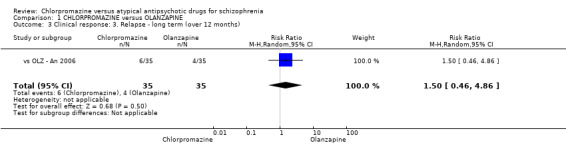

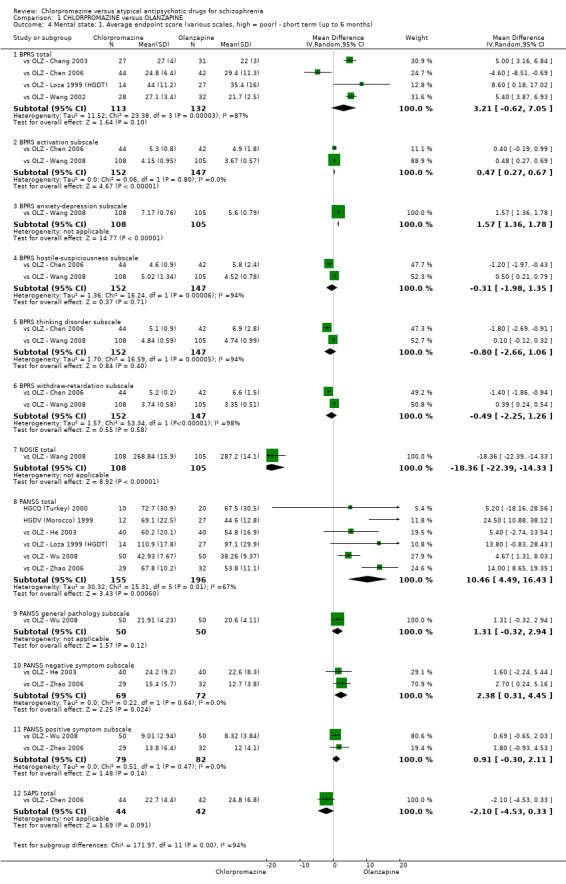

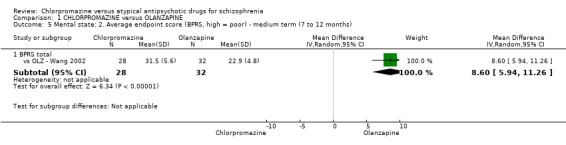

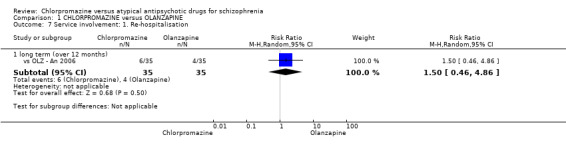

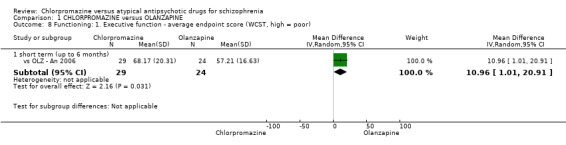

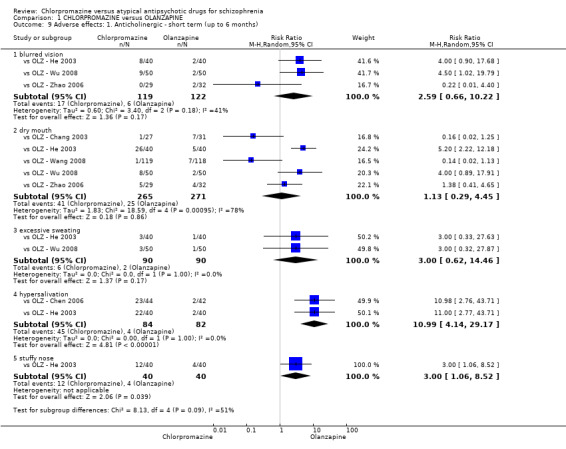

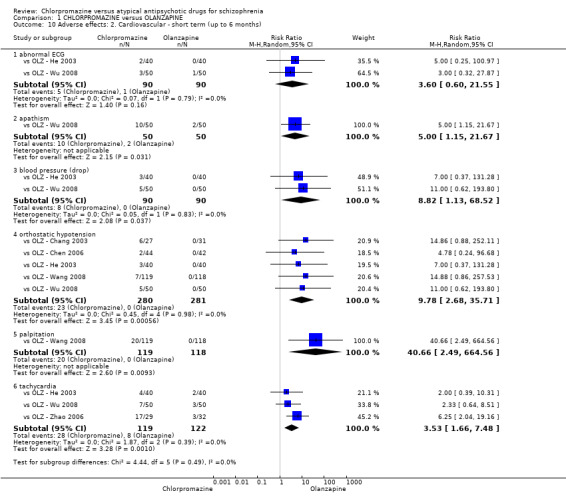

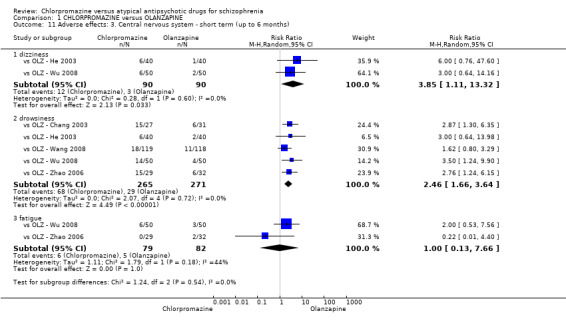

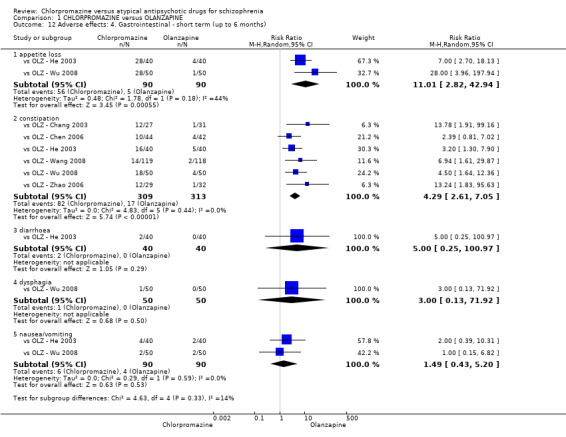

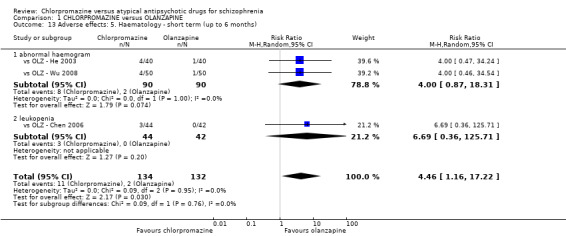

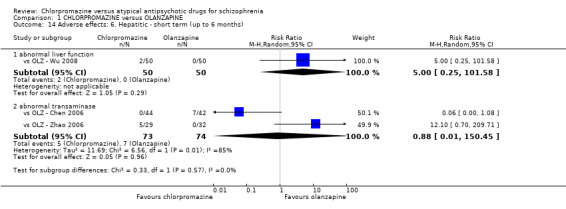

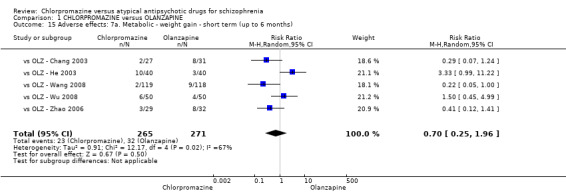

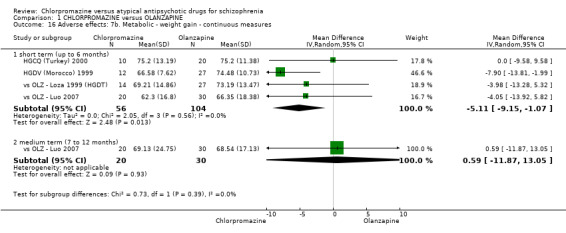

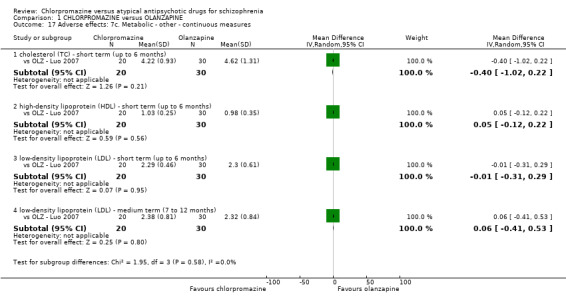

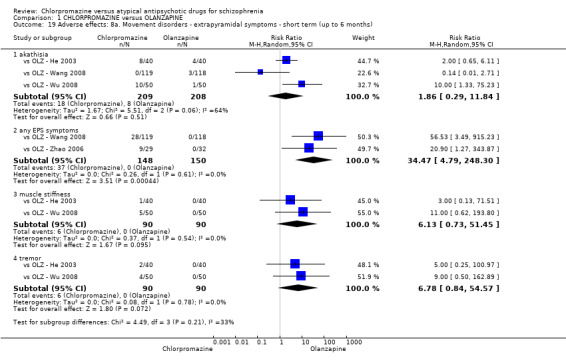

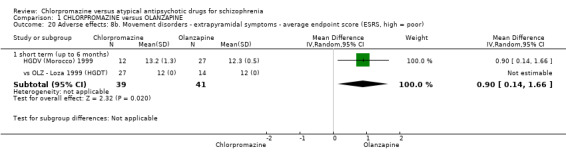

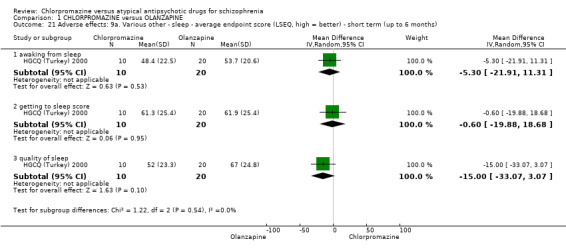

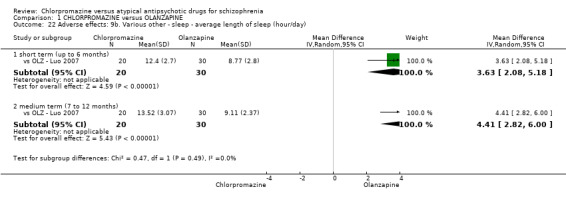

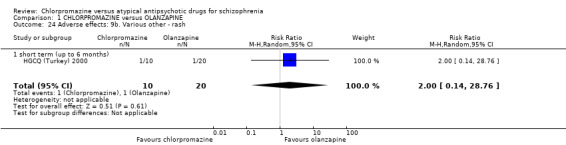

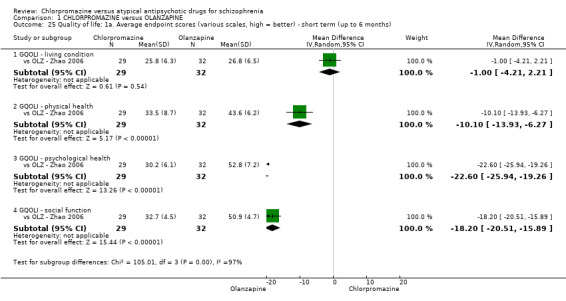

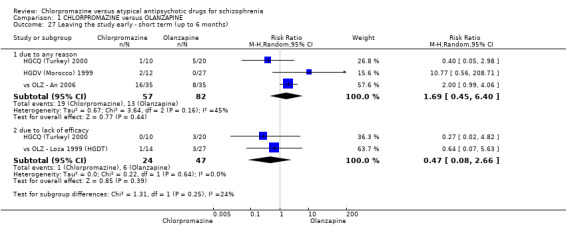

1. Chlorpromazine versus olanzapine

In the short term, there appeared to be a significantly greater clinical response (as defined in each study) in people receiving olanzapine (3 RCTs, N = 204; RR 2.34, 95% CI 1.37 to 3.99, low quality evidence). There was no difference between drugs for relapse (1 RCT, N = 70; RR 1.5, 95% CI 0.46 to 4.86, very low quality evidence), nor in average endpoint score using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) for mental state (4 RCTs, N = 245; MD 3.21, 95% CI −0.62 to 7.05,very low quality evidence). There were significantly more extrapyramidal symptoms experienced amongst people receiving chlorpromazine (2 RCTs, N = 298; RR 34.47, 95% CI 4.79 to 248.30,very low quality evidence). Quality of life ratings using the general quality of life interview (GQOLI) ‐ physical health subscale were more favourable with people receiving olanzapine (1 RCT, N = 61; MD −10.10, 95% CI −13.93 to −6.27, very low quality evidence). There was no difference between groups for people leaving the studies early (3 RCTs, N = 139; RR 1.69, 95% CI 0.45 to 6.40, very low quality evidence).

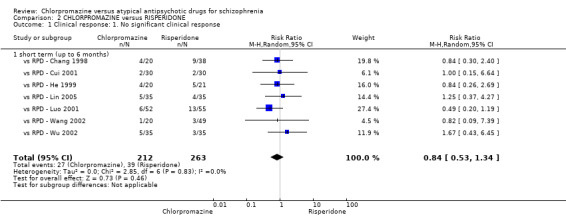

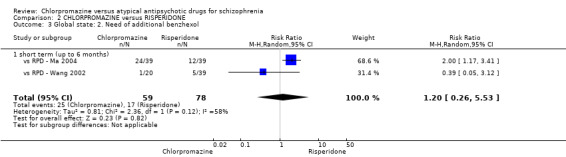

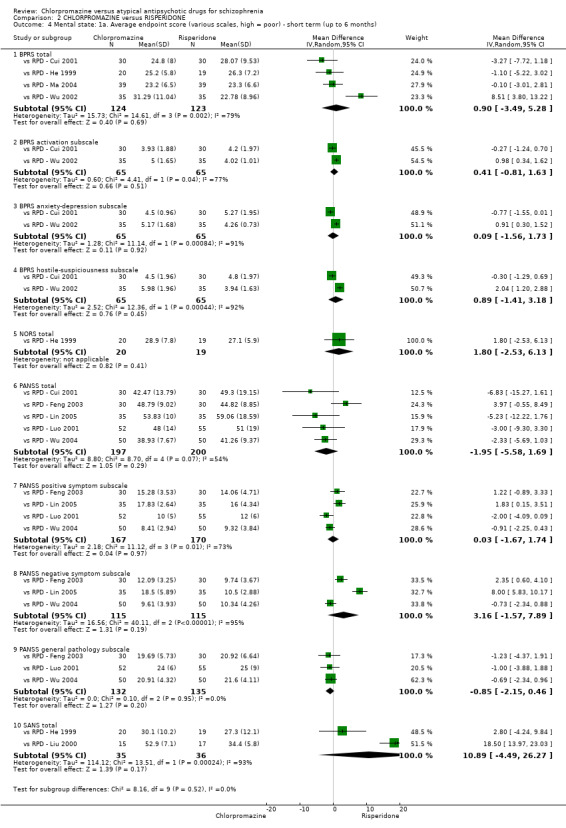

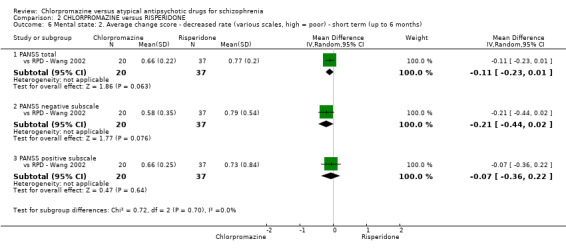

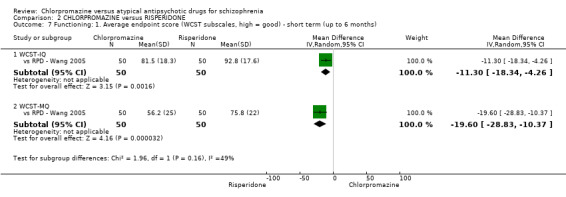

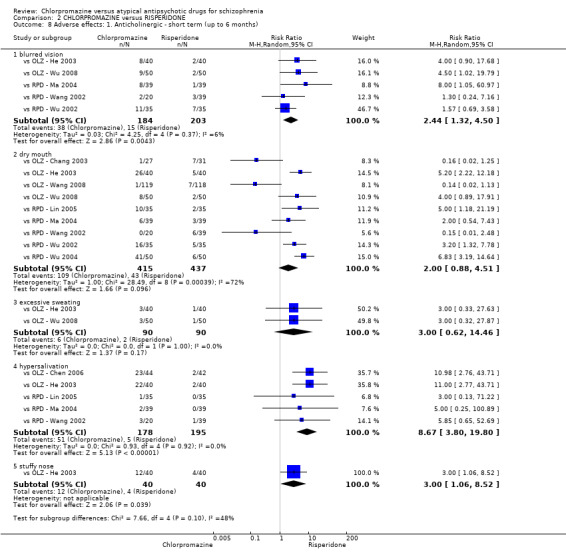

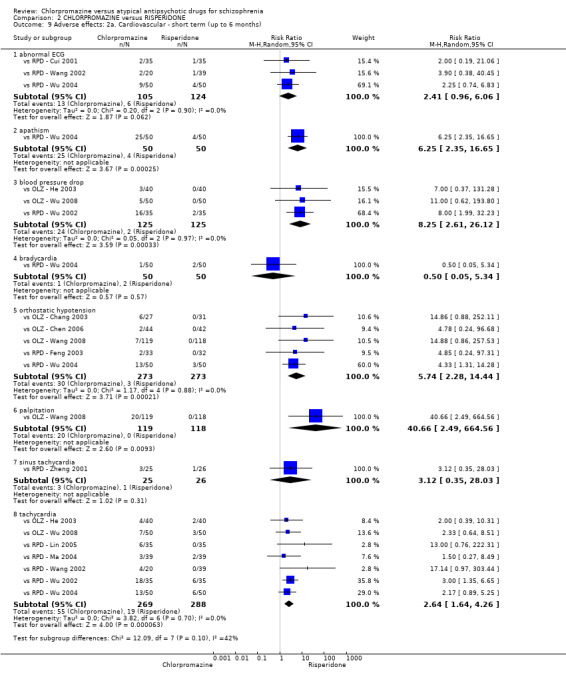

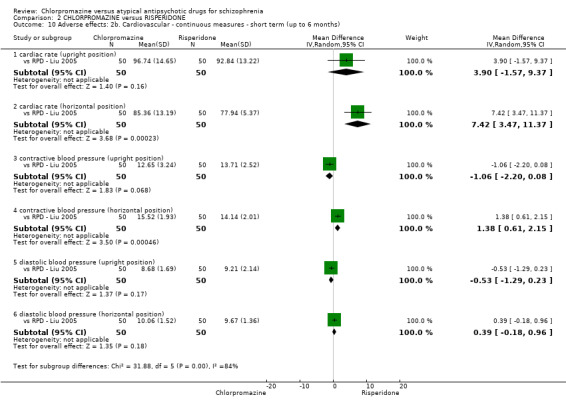

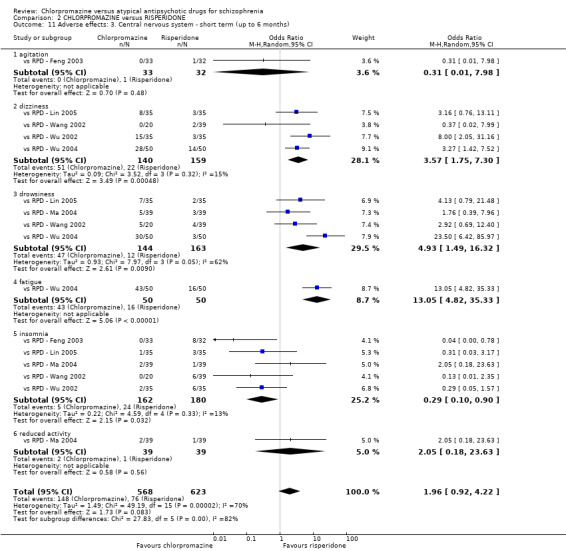

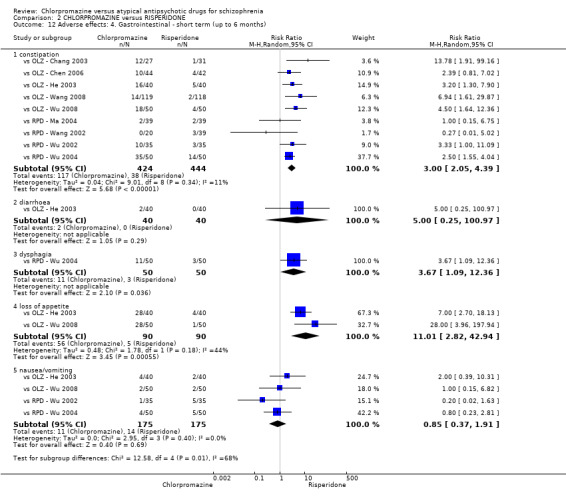

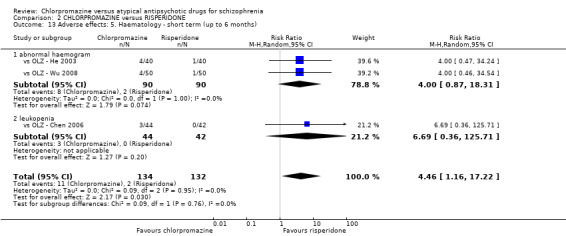

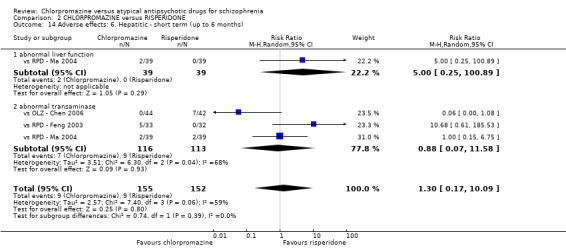

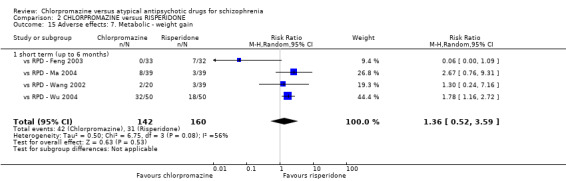

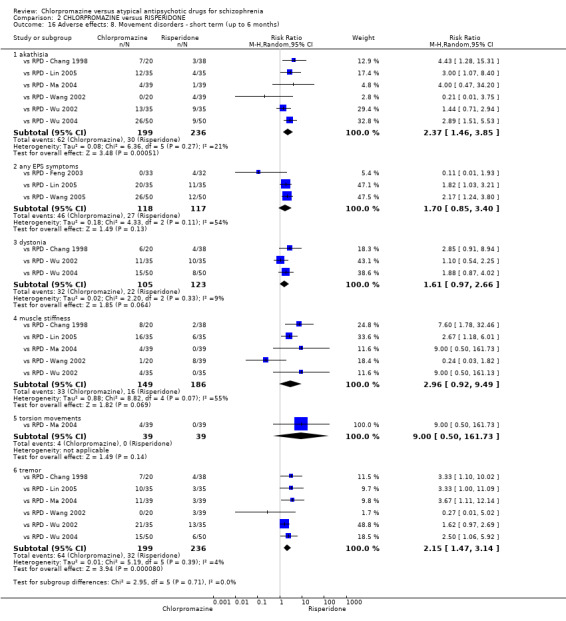

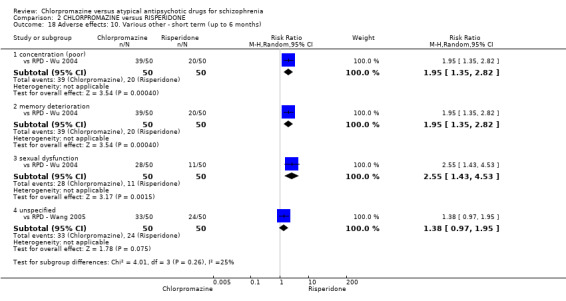

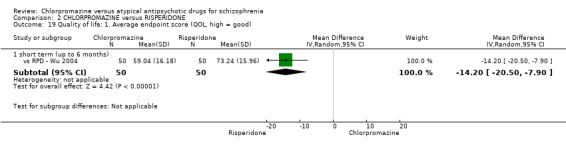

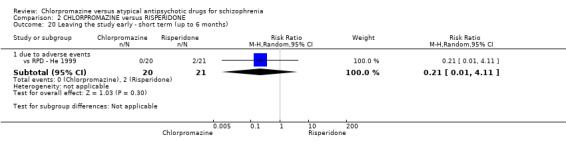

2. Chlorpromazine versus risperidone

In the short term, there appeared to be no difference in clinical response (as defined in each study) between chlorpromazine or risperidone (7 RCTs, N = 475; RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.34, low quality of evidence), nor in average endpoint score using the BPRS for mental state 4 RCTs, N = 247; MD 0.90, 95% CI −3.49 to 5.28, very low quality evidence), or any observed extrapyramidal adverse effects (3 RCTs, N = 235; RR 1.7, 95% CI 0.85 to 3.40,very low quality evidence). Quality of life ratings using the QOL scale were significantly more favourable with people receiving risperidone (1 RCT, N = 100; MD −14.2, 95% CI −20.50 to −7.90, very low quality evidence). There was no difference between groups for people leaving the studies early (one RCT, N = 41; RR 0.21, 95% CI 0.01 to 4.11, very low quality evidence).

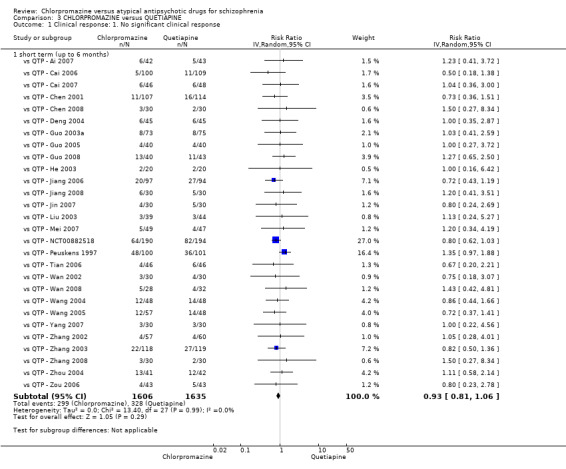

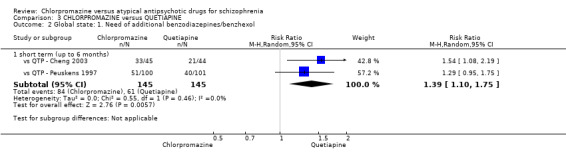

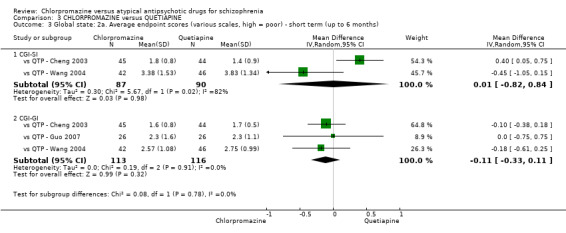

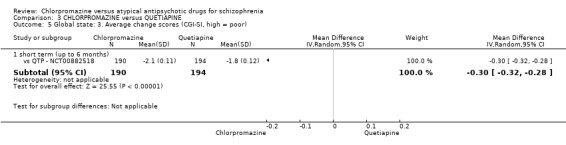

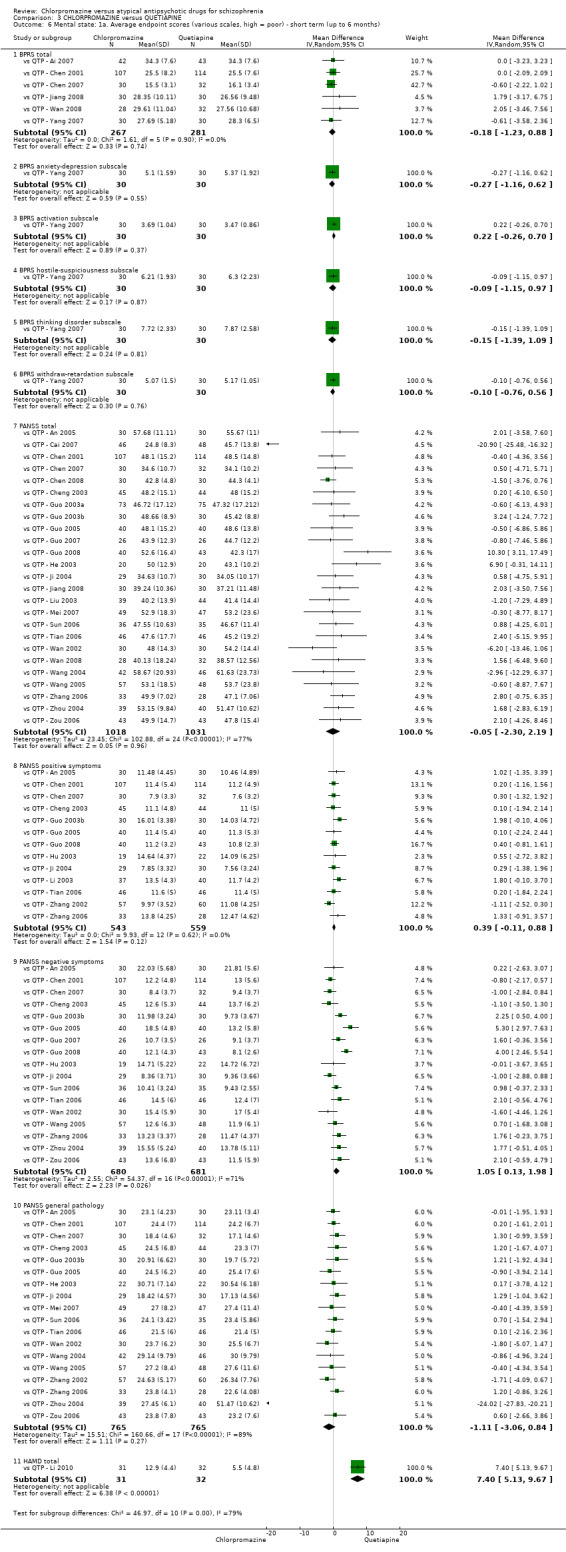

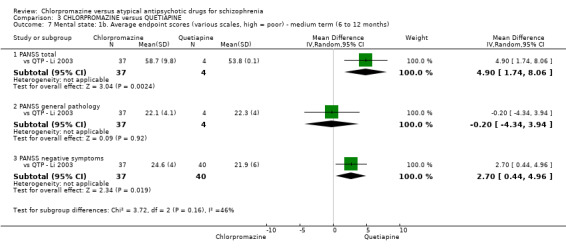

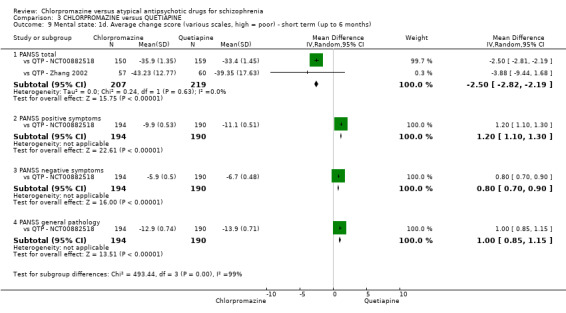

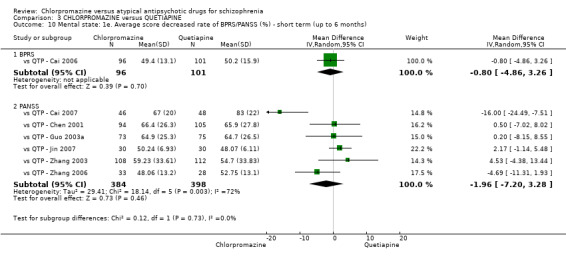

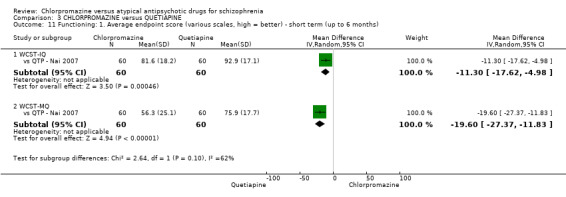

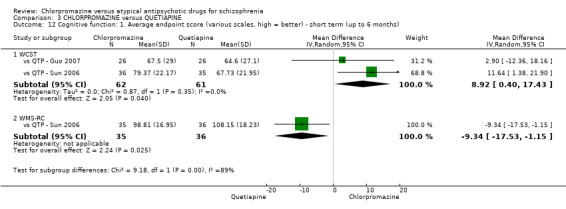

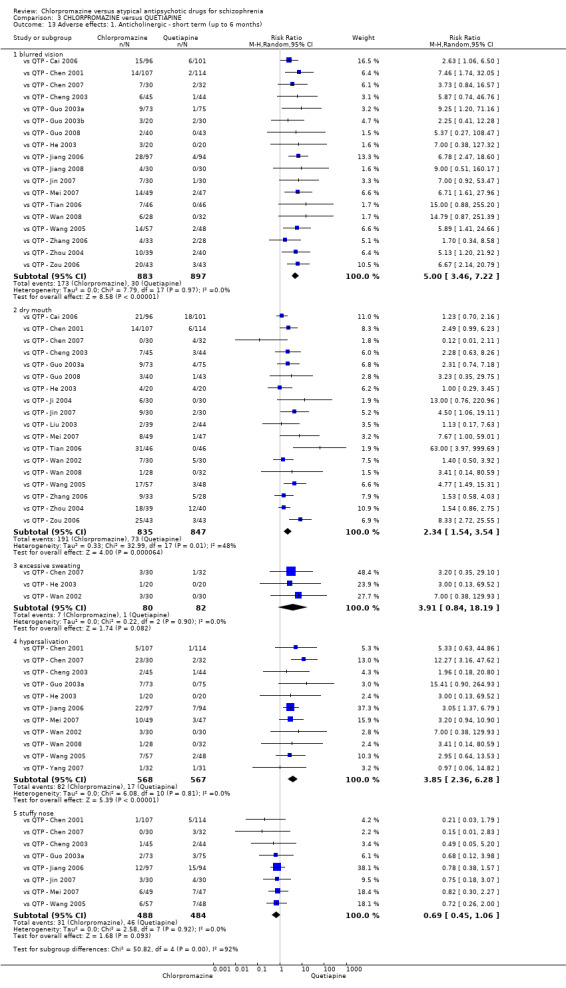

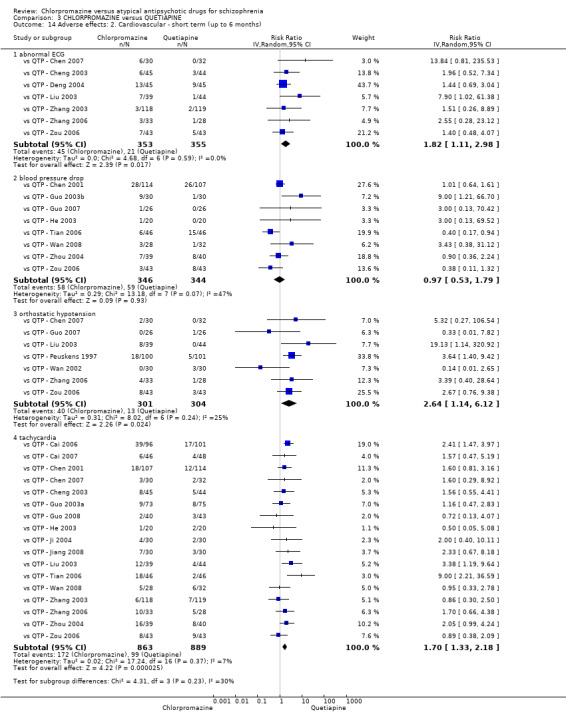

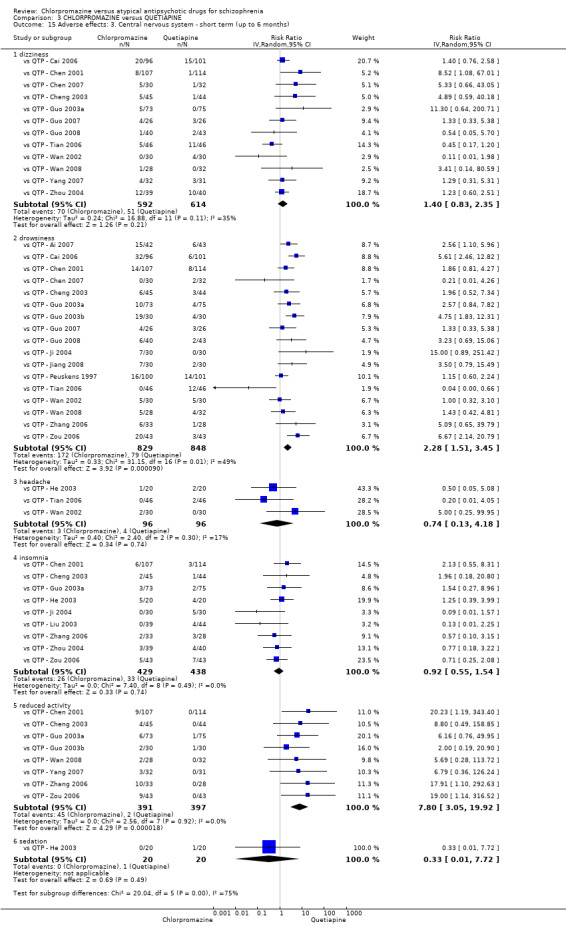

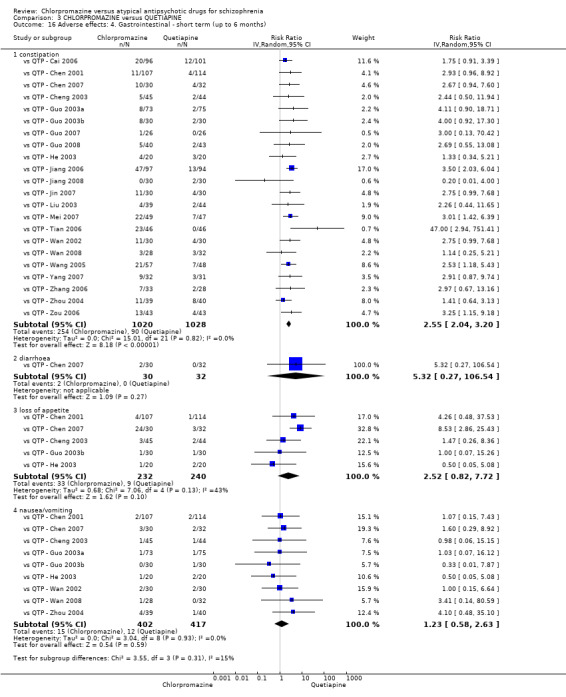

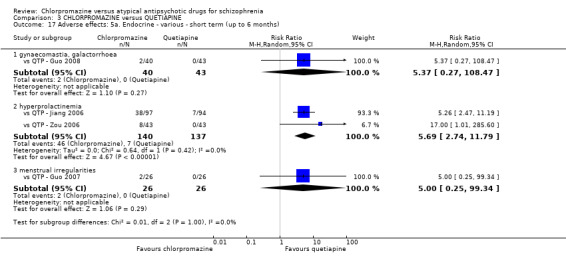

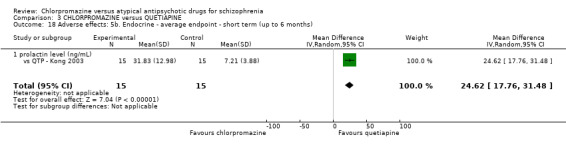

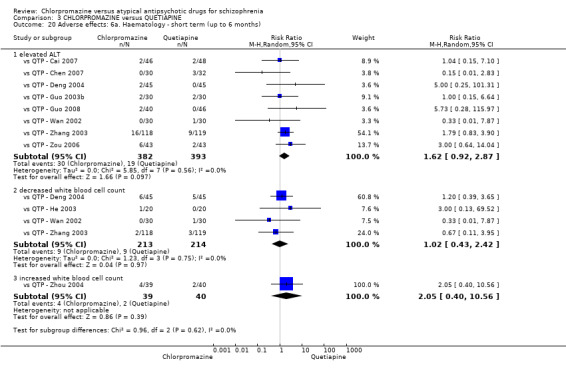

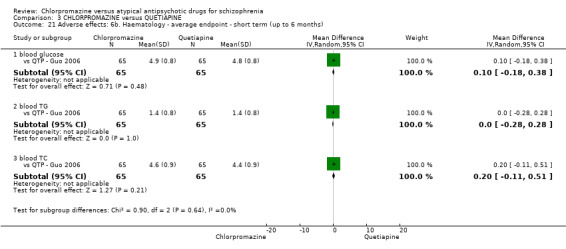

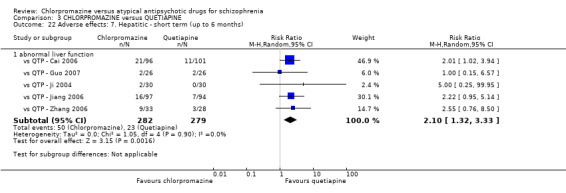

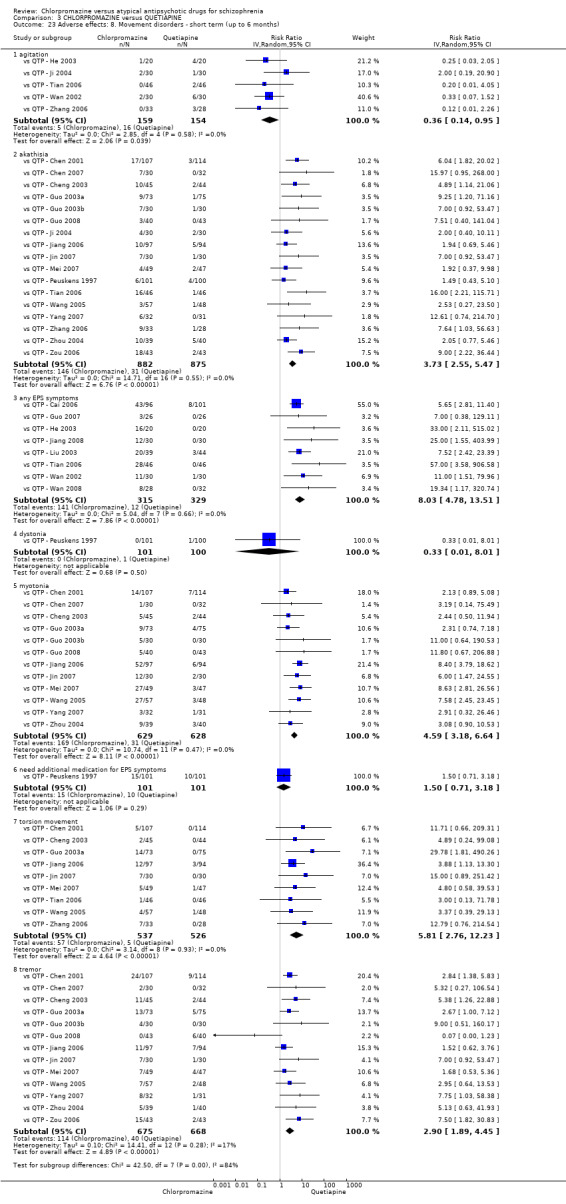

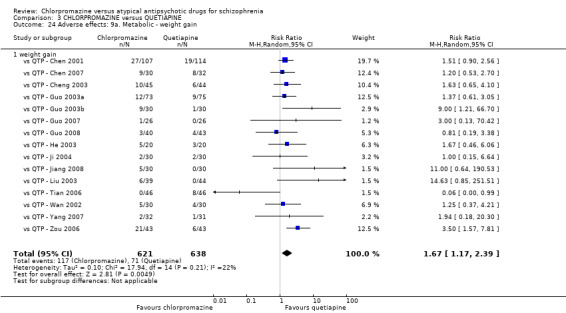

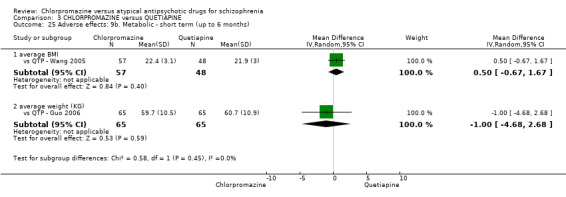

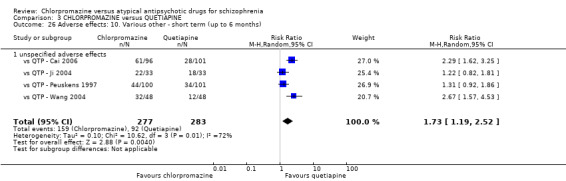

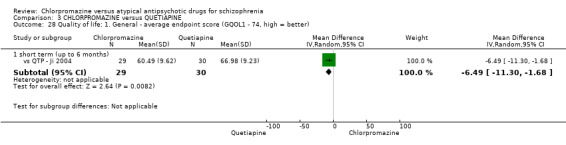

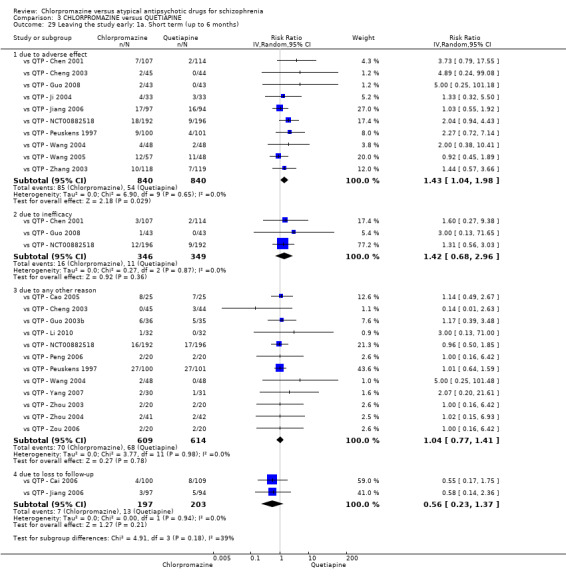

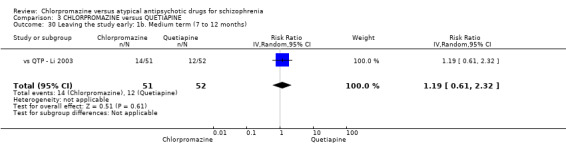

3. Chlorpromazine versus quetiapine

In the short term, there appeared to be no difference in clinical response (as defined in each study) between chlorpromazine or quetiapine (28 RCTs, N = 3241; RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.06, moderate quality evidence) nor in average endpoint score using the BPRS for mental state (6 RCTs, N = 548; MD −0.18, 95% CI −1.23 to 0.88, very low quality evidence). Quality of life ratings using the GQOL1‐74 scale were significantly more favourable with people receiving quetiapine (1 RCT, N = 59; MD −6.49, 95% CI −11.30 to −1.68, very low quality evidence). Significantly more people receiving chlorpromazine experienced extrapyramidal adverse effects (8 RCTs, N = 644; RR 8.03, 95% CI 4.78 to 13.51, low quality of evidence). There was no difference between groups for people leaving the studies early in the short term (12 RCTs, N = 1223; RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.41,moderate quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

Most included trials included inpatients from hospitals in China. Therefore the results of this Cochrane review are more applicable to the Chinese population. Mostincluded trials were short term studies, therefore we cannot comment on the medium and long term use of chlorpromazine compared to atypical antipsychotics. Low qualityy evidence suggests chlorpromazine causes more extrapyramidal adverse effects. However, all studiesused varying dose ranges, and higher doses would be expected to be associated with more adverse events.

Plain language summary

Chlorpromazine compared with newer atypical antipsychotics

People with schizophrenia often hear voices or see things (hallucinations) and have strange beliefs (delusions). The main treatment for people with these symptoms of schizophrenia is antipsychotic drugs. Chlorpromazine was one of the first drugs discovered to be effective for treating people with schizophrenia. It remains one of the most commonly used and inexpensive treatments. However, being an older drug (typical or first generation) it also has serious side effects, including blurred vision, a dry mouth, tremors or uncontrollable shaking, depression, muscle stiffness and restlessness.

In this Cochrane review we examined the effects of chlorpromazine for treating people with schizophrenia compared with newer antipsychotic drugs.

We searched the literature for randomised controlled trials up to 23 September 2013, and included 71 trials. The included studies compared chlorpromazine with three newer antipsychotics: risperidone, quetiapine or olanzapine. Most included trials were short term studies and undertaken in China. Based on low quality evidence, we found that chlorpromazine is not much different to risperidone or quetiapine but is associated with more side effects. More favourable results were found for olanzapine with those receiving olanzapine experiencing fewer side effects and greater improvements in global state and quality of life than those receiving chlorpromazine, but again this is based on low quality evidence. Larger, longer, better conducted and reported trials should focus on important outcomes such as quality of life, levels of satisfaction with treatment or care, relapse, costs and hospital discharge or admission. Also, more international studies are needed. Outpatient treatment was under‐represented in the included studies, and future research should also include work with this group of people.

Due to the limitations of evidence in this Cochrane review, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions. Chlorpormazine is available widely, is comparable with the newer antipsychotics and is relatively cheap so despite its propensity to cause side effects, is likely to remain one of the benchmark antipsychotics.

The plain language summary has been written by a consumer. Ben Gray: Senior Peer Researcher, McPin Foundation. http://mcpin.org/.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. CHLORPROMAZINE versus OLANZAPINE for schizophrenia.

| Chlorpromazine versus olanzapine for schizophrenia | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with schizophrenia Settings: inpatient and outpatient Intervention: chlorpromazine Comparison: olanzapine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Olanzapine | Chlorpromazine | |||||

| No significant clinical response: short term (up to 6 months) Follow‐up: 6 to 12 weeks | Low1 | RR 2.34 (1.37 to 3.99) | 204 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | ‐ | |

| 700 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (959 to 1000) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 190 per 1000 | 445 per 1000 (260 to 758) | |||||

| Relapse: long term (over 12 months) Follow‐up: mean 2 years | Study population | RR 1.5 (0.46 to 4.86) | 70 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4 | ‐ | |

| 114 per 1000 | 171 per 1000 (53 to 555) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 114 per 1000 | 171 per 1000 (52 to 554) | |||||

| Mental state: short term (up to 6 months) BRPS average endpoint score (high = poor) Follow‐up: 6 to 12 weeks | The mean mental state: short term (up to 6 months) in the intervention groups was 3.21 higher (0.62 lower to 7.05 higher) | 245 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,5,6,7 | ‐ | ||

| Adverse effects: any observed extrapyramidal symptoms ‐ short term (up to 6 months) Follow‐up: mean 8 weeks | Low | RR 34.47 (4.79 to 248.3) | 298 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,8 | ‐ | |

| 10 per 1000 | 345 per 1000 (48 to 1000) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 100 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (479 to 1000) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 250 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (1000 to 1000) | |||||

| Quality of life: short term (up to 6 months) GQOLI‐physical health subscale score (high = good) Follow‐up: mean 8 weeks | The mean quality of life: short term (up to 6 months) in the intervention groups was 10.10 lower (13.93 to 6.27 lower) | 61 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,7,9,10 | ‐ | ||

| Leaving the study early due to any reason: short term (up to 6 months) Follow‐up: mean 6 weeks | Study population11 | RR 1.69 (0.45 to 6.4) | 139 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,12,13 | ‐ | |

| 159 per 1000 | 268 per 1000 (71 to 1000) | |||||

| Moderate11 | ||||||

| 229 per 1000 | 387 per 1000 (103 to 1000) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Control risk: the control risks are representative of the control group risks of the study population. 2Risk of bias: rated serious ‐ most included studies had unclear risk of bias in terms of allocation and blinding, hence selection and detection bias are likely to be present. Two studies also had high risk of reporting bias. 3Publication bias: strongly suspected ‐ we identified only small trial(s) from China for this outcome. Publication bias is highly suspected. 4Imprecision: serious ‐ only one small trial with unclear risk of selection and detection bias contributed data to this outcome. The result was imprecise with few event and a wide CI. 5Inconsistency: serious ‐ unexplained heterogeneity present, suggesting different magnitude of effect. 6Indirectness: serious ‐ binary outcome assessing mental state is unavailable. We, therefore, employed BPRS score as an alternative indicator. 7Imprecision: serious ‐ a relatively wide CI around the point of estimate of effect. Sample size is smaller than the optimal information size. 8Imprecision: serious ‐ although significant difference was observed between groups, the CI was wide (95% CI 4.97 to 248.3). 9Indirectness: serious ‐ binary outcome for quality of life is unavailable. We, thus, used outcome from QOL‐ physical health subscale as an alternative indicator. 10Imprecision: serious ‐ although significant difference was observed between group, the total sample size is smaller than the optimal information size. 11Control risk: the control risks in the study population are very close to the moderate risk observed here. Thus we adopted it to represent the control risk. 12Risk of bias: serious ‐ most included studies that contributed data to this outcome had high risk of bias with the selection, detection and reporting of the result. 13Imprecision: serious ‐ estimate of effect was not significant and the total sample size is smaller than the desired optimal information size.

Summary of findings 2. CHLORPROMAZINE versus RISPERIDONE for schizophrenia.

| Chlorpromazine versus risperidone for schizophrenia | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with schizophrenia Settings: inpatient and outpatient Intervention: chlorpromazine Comparison: risperidone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Risperidone | Chlorpromazine | |||||

| No significant clinical response ‐ short term (up to 6 months) Follow‐up: median 8 to 12 weeks | Low1 | RR 0.84 (0.53 to 1.34) | 475 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | ‐ | |

| 60 per 1000 | 50 per 1000 (32 to 80) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 114 per 1000 | 96 per 1000 (60 to 153) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 240 per 1000 | 202 per 1000 (127 to 322) | |||||

| Mental state: short term (up to 6 months) BPRS endpoint scale score (high = poor) Follow‐up: 6 to 12 weeks | The mean mental state: short term (up to 6 months) in the intervention groups was 0.9 higher (3.49 lower to 5.28 higher) | 247 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,4,5,6,7 | ‐ | ||

| Adverse effects: any observed extrapyramidal symptoms ‐ short term (up to 6 months) Follow‐up: 8 to 12 weeks | Low1 | RR 1.7 (0.85 to 3.4) | 235 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,6,7 | ‐ | |

| 130 per 1000 | 221 per 1000 (111 to 442) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 240 per 1000 | 408 per 1000 (204 to 816) | |||||

| Quality of life: short term (up to 6 months) QOL endpoint scale score (high = good) Follow‐up: mean 12 weeks | The mean quality of life: short term (up to 6 months) in the intervention groups was 14.2 lower (20.5 to 7.9 lower) | 100 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low7,8,9,10 | ‐ | ||

| Leaving the study early due to adverse effects ‐ short term (up to 6 months) Follow‐up: mean 8 weeks | Study population | RR 0.21 (0.01 to 4.11) | 41 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low7,10 | ‐ | |

| 95 per 1000 | 20 per 1000 (1 to 391) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 95 per 1000 | 20 per 1000 (1 to 390) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Control risk: the control risks are representative of those observed in the study population. 2Risk of bias: serious ‐ most of the included studies had unclear risk of bias in terms of allocation and blinding, hence selection and detection bias are likely to be present. Some of the studies also had high risk of reporting bias. 3Publication bias: strongly suspected ‐ only Chinese studies with relatively small sample size were identified. Publication bias is highly likely. 4Inconsistency: serious ‐ unexplained heterogeneity present, suggesting different magnitude of effect. 5Indirectness: serious ‐ binary outcome assessing mental state is unavailable. We, therefore, employed BPRS score as an alternative indicator. 6Imprecision: serious ‐ although the CI around the estimate of effect relatively tight, the result was not significant and sample size was smaller than the optimal information size. 7Publication bias: strongly suspected ‐ only one study with unclear risk of selection and detection bias available for this outcome. 8Indirectness: serious ‐ binary outcome for quality of life was not available. Therefore, we adopted QOL score as an indicator. 9Imprecision: serious ‐ estimate of effect was significant with tight CI, but the study sample size is smaller than the optimal information size. 10Imprecision: serious ‐ estimate of effect was not significant and with relatively wide CI. Sample size was smaller than the optimal information size.

Summary of findings 3. CHLORPROMAZINE versus QUETIAPINE for schizophrenia.

| Chlorpromazine versus quetiapine for schizophrenia | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with schizophrenia Settings: inpatient and outpatient Intervention: chlorpromazine Comparison: quetiapine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Quetiapine | Chlorpromazine | |||||

| No significant clinical response: short term (up to 6 months) Follow‐up: 4 to 16 weeks | Low1 | RR 0.93 (0.81 to 1.06) | 3241 (28 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | ‐ | |

| 70 per 1000 | 65 per 1000 (57 to 74) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 128 per 1000 | 119 per 1000 (104 to 136) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 360 per 1000 | 335 per 1000 (292 to 382) | |||||

| Mental state: short term (up to 6 months) BPRS endpoint scale score (high = poor) Follow‐up: 6 to 12 weeks | The mean mental state: short term (up to 6 months) in the intervention groups was 0.18 lower (1.23 lower to 0.88 higher) | 548 (6 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4,5 | ‐ | ||

| Quality of life: short term (up to 6 months) GQOL1‐74 endpoint scale score (high = good) Follow‐up: mean 12 weeks | The mean quality of life: short term (up to 6 months) in the intervention groups was 6.49 lower (11.3 to 1.68 lower) | 59 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low6,7,8,9 | ‐ | ||

| Adverse effects: any observed extrapyramidal symptoms ‐ short term (up to 6 months) Follow‐up: 6 to 8 weeks | Study population | RR 8.03 (4.78 to 13.51) | 644 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,5 | ‐ | |

| 36 per 1000 | 293 per 1000 (174 to 493) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 80 per 1000 | 642 per 1000 (382 to 1000) | |||||

| Leaving the study early due to any reason short term (up to 6 months) Follow‐up: 6 to 16 weeks | Moderate1 | RR 1.04 (0.77 to 1.41) | 1223 (12 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | ‐ | |

| 93 per 1000 | 97 per 1000 (72 to 131) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 280 per 1000 | 291 per 1000 (216 to 395) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Control risk: are representative of those observed in the study population. 2Risk of bias: serious ‐ most of the included studies had unclear risk of bias in terms of allocation and blinding, hence selection and detection bias are likely to be present. Some of the studies also had high risk of reporting bias. 3Indirectness: serious ‐ binary outcome on mental state is not available. Thus we employed BPRS rating as an indicator. 4Imprecision: serious ‐ although the estimate of effect was not significant, the CI was relatively tight around the point of estimate. The sample size is also relatively large and exceed the calculated optimal information size. 5Publication bias: strongly suspected ‐ only Chinese trials with small sample size were identified for this outcome. 6Risk of bias: serious ‐ the only study contributed data to this outcome had unclear risk of selection and detection bias. It also had attrition data that we excluded from the final analysis. 7Indirectness: serious ‐ there was no binary measurement available on quality of life. Therefore, we used GQOLI‐74 as an alternative indicator. 8Imprecision: serious ‐ sample size was smaller than the optimal information size. 9Publication bias: strongly suspected ‐ we only identified a Chinese trial with a small sample size with positive findings for this outcome.

Background

Description of the condition

Schizophrenia is a severe form of mental health disorder. It has a high lifetime prevalence rate, affecting (4 per 1000 people (Saha 2005), but low incident rate because of the chronic nature of the illness. The median incident rate of schizophrenia is 15.2 per 100,000 people (McGrath 2008).

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) classifies the illness into categories F20 to F29 as ‘schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorder’ (ICD‐10 1992), particularly ‘schizophrenia’ in F20. The ICD‐10 states that "schizophrenic disorders are characterized in general by fundamental and characteristic distortions of thinking and perception, and affects that are inappropriate or blunted". The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association has also used the term ‘schizophrenia’ (DSM‐IV‐TR 2000).

The prognosis of schizophrenia is quite variable, and in the past psychiatrists were not very optimistic about its treatment (Kraeplin 1919). However, recent studies show that the outcome of schizophrenia treatment is better than previously thought. The use of phenothiazines may have contributed to this as well as other factors, such as improving community services (Bland 1978).

Description of the intervention

Psychiatrists have prescribed typical antipsychotic drugs since the 1950s, when the first antipsychotic medication, chlorpromazine, was synthesized. Chlorpromazine was first used as an antihistaminic agent to treat allergies. Later, surgeons used it as a pre‐surgical medication to sedate people before surgical procedures (Laborit 1951). In 1952, Paul Charpentier, from Laboratories Rhône‐Poulenc in France, and Delay and Deniker's team described the antipsychotic properties of chlorpromazine (Delay 1952). Chlorpromazine is considered a pivotal discovery in the field of psychosis treatment, with other antipsychotics often measured in 'chlorpromazine equivalents' (Turner 2007; Yorston 2000).

There are now many antipsychotic drugs available. They are broadly divided into two groups: ‘typical antipsychotic drugs’ and ‘atypical antipsychotic drugs’. Typical antipsychotic drugs are also known as ‘first generation’, ‘conventional’ or ‘classical’ antipsychotic drugs, e.g. chlorpromazine and haloperidol. Atypical antipsychotic drugs are also known as ‘second generation’ or ‘newer antipsychotic drugs’, e.g. clozapine, risperidone, quetiapine and olanzapine. Typical antipsychotic drugs have a good reputation regarding their efficacy in treating the 'positive' symptoms of schizophrenia (e.g. delusions and hallucinations) (Mathews 2007). They are also well known for their adverse effects, such as movement disorders (extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) or extrapyramidal side effects (EPSE)), sedation, metabolic syndromes and sometimes potentially fatal conditions, such as neuroleptic malignant syndrome (Arana 2000). The second generation antipsychotic drugs arrived on the market, claiming notable differences. They had a reputed low side‐effect profile and, according to pharmaceutical companies, higher efficacy (Janssen 1988). However, research funded independently of pharmaceutical companies has suggested that there may be little difference between the older and newer drugs (Adams 2014). This has subsequently fuelled debate as to whether new atypical antipsychotics are more effective than older established first‐generation antipsychotics, and whether questioning the efficacy of the two classifications of drugs creates an improper generalisation of antipsychotics that do not form a homogenous class (Leucht 2009). Against this backdrop, chlorpromazine remains a benchmark drug in the treatment of schizophrenia. Although imperfect, it is relatively inexpensive and remains one of the most common drugs used for treating people with schizophrenia worldwide (Adams 2005).

How the intervention might work

Chlorpromazine is an aliphatic phenothiazine, which is one of the widely‐used typical antipsychotic drugs. Chlorpromazine is reliable for its efficacy and one of the most tested first generation antipsychotic drugs. It has been used as a ‘gold standard’ to compare the efficacy of older and newer antipsychotic drugs. It blocks alpha 1, 5HT2A, D2 and D1 receptors in the brain, and thus it works as an antipsychotic. It also has effect on muscarinic, serotonin and H1 receptors. By blocking D2 receptor it can also cause extrapyramidal side effects. Other adverse effects include dry mouth, blurred vision, restlessness, sedation, neuroleptic malignant syndrome (DSM‐IV 1994) etc. On the other hand, atypical antipsychotic drugs by definition may cause decreased or no extrapyramidal side effects (Kinon 1996). Different atypical antipsychotic drugs act in different ways; for example, clozapine blocks D2 and 5HT2 receptors (Meltzer 1989). Both clozapine and quetiapine blocks more 5HT2 receptors than D2 receptors. olanzapine blocks 5HT2A, 5HT6, D1, D2, D3 and muscarinic receptors (Zhang 1999).

Why it is important to do this review

This is one of a family of related Cochrane reviews on this important compound (Table 4).

1. Related Cochrane Reviews.

| Comparison | Reference |

| Chlorpromazine versus placebo | Adams 2014 |

| Chlorpromazine versus haloperidol | Leucht 2008 |

| Chlorpromazine doses | Liu 2009 |

| Chlorpromazine cessation | Almerie 2007 |

| Chlorpromazine for acute aggression | Ahmed 2010 |

Chlorpromazine is one of two oral antipsychotic drugs on the World Health Organization's Essential Drug list (WHO 2011). It is globally accessible and has been known for its effectiveness in schizophrenia treatment since the 1950s (Adams 2014), and it is also the most commonly used and inexpensive treatment for schizophrenia (Odejide 1982). Expensive new generation drugs are heavily marketed worldwide as a better treatment for schizophrenia. However, this may not be the case and may be an unnecessary drain on very limited resources (Adams 2006). Also, comparisons with new generation drugs, which are coming off‐patent and are therefore more accessible, are important to assist informed and independent choice of treatment for people with schizophrenia.

Objectives

To compare the effects of chlorpromazine with atypical or second generation antipsychotic drugs, for treatment of people with schizophrenia (seeDifferences between protocol and review).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs). If a trial was described as double‐blind but implied randomisation, we included such trials in a sensitivity analysis (see Sensitivity analysis). If their inclusion did not result in a substantive difference, we kept these trials in the analyses. If their inclusion resulted in statistically significant differences, we did not add the data from these lower quality studies to the results of the better trials, but presented such data within a subcategory. We excluded quasi‐RCTs (e.g. allocating by alternate days of the week). Where people were given additional treatments within the chlorpromazine and atypical antipsychotic groups, we only included data if the adjunct treatment was evenly distributed between groups and only the chlorpromazine and atypical antipsychotic groups were randomised.

Types of participants

Adults (as defined in each trial) diagnosed with schizophrenia, including schizophreniform, schizoaffective and delusional disorders (any means of diagnosis, including operational criteria (DSM‐IV 1994; ICD‐10 1992) or clinical opinion).

We are interested in making sure that information is as relevant to the current care of people with schizophrenia as possible so if the information was reported we clearly highlighted in the Characteristics of included studies and Description of studies, the current clinical state (acute, early post ‐ acute, partial remission, remission) as well as the stage (prodromal, first episode, early illness, persistent) and as to whether the studies primarily focused on people with particular problems (for example, negative symptoms, treatment‐resistant illnesses).

Types of interventions

1. Chlorpromazine

Any dose and any route of administration.

2. Any atypical antipsychotic

Atypical antipsychotic drugs including: amisulpride, aripiprazole, asenapine (Smith 2010), clozapine, clothiapine or clotiapine (Toren 1995), iloperidone (Caccia 2010), lurasidone (Risbood 2012), mosapramine (Takahashi 1999), olanzapine, paliperidone, perospirone (Bian 2008), quetiapine, remoxipride (Nadal 2001), risperidone, sertindole (Cincotta 2010), sulpiride (Rzewuska 1988), ziprasidone and zotepine (list non‐exhaustive).

Any dose and any route of administration.

Types of outcome measures

If possible, we divided outcomes into short term (up to six months), medium term (seven to 12 months) and long term (over one year).

Primary outcomes

1. Clinical response

Clinically significant improvement as defined by each included trial.

2. Relapse

As defined by each trial.

Secondary outcomes

1. Death: natural death or suicide

2. Global state

2.1 Any change in global state. 2.2 Deterioration. 2.3 Need for additional antipsychotic drugs. 2.4 Need for additional benzodiazepines. 2.5 Poor compliance.

3. Mental state

3.1 General symptoms

3.1.1 Any change in general symptoms. 3.1.2 Average endpoint general symptom score. 3.1.3 Average change in general symptom score.

3.2 Specific symptoms (positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia, depression and mania/hypomania)

3.2.1 Any change of specific symptoms. 3.2.2 Average endpoint specific symptom score. 3.2.3 Average change specific symptom score.

4. Service involvement

4.1 Duration of hospital stay. 4.2 Re‐hospitalisation. 4.3 Engagement with community services. 4.4 Engagement with inpatient/outpatient services.

5. Functioning

5.1 General functioning

5.1.1 Any change in general functioning. 5.1.2 Average endpoint score in general functioning. 5.1.3 Average change score in general functioning.

5.2 Social functioning

5.1.1 Any change in social functioning. 5.1.2 Average endpoint score in social functioning. 5.1.3 Average change score in social functioning

5.3 Employment status

5.1.1 Any change in employment status. 5.1.2 Average endpoint score in employment functioning. 5.1.3 Average change score in employment functioning.

6. Behaviour

6.1 General behaviour. 6.2 Any improvement in behaviour, as defined in each trial. 6.3 Specific behaviour (e.g. agitation, aggression, violent incidents). 6.4 Average endpoint in behaviour scores. 6.5 Average change in behaviour scores.

7. Adverse effects

7.1 Anticholinergic. 7.2 Cardiovascular. 7.3 Central nervous system. 7.4 Gastrointestinal. 7.5 Endocrine (e.g. amenorrhoea, galactorrhoea, hyperlipidaemia, hyperglycaemia, hyperinsulinemia). 7.6 Haematology (e.g. haemogram, leukopenia, agranulocytosis/neutropenia). 7.7 Hepatitic (e.g. abnormal transaminase, abnormal liver function). 7.8 Metabolic. 7.9 Movement disorders. 7.10 Various other.

8. Satisfaction

8.1 Patient satisfaction. 8.2 Carer satisfaction. 8.3 Professional satisfaction (managers/doctors/nurses).

9. Economic outcomes

9.1 Direct costs, as defined in each study. 9.2 Indirect costs, as defined in each study. 9.3 Cost‐effectiveness, as defined in each study.

10. Quality of life

10.1 Average endpoint score in quality of life. 10.2 Average change score in quality of life. 10.3 Any improvement in quality of life.

11. Leaving the study early

'Summary of findings' tables

We used the GRADE approach to interpret findings (Schünemann 2008) and used GRADE profiler (GRADEPRO) to import data from RevMan 5 (Teview Manager) to create 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables provide outcome ‐ specific information concerning the overall quality of evidence from each included study in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on all outcomes we rated as important to patient care and decision making. We aimed to select the following main outcomes for inclusion in the 'Summary of findings' tables:

Clinical response: clinically significant improvement (as defined by each of the studies) by medium term.

Relapse (as defined by each of the studies) by medium term.

Mental state: average endpoint score (Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)) by medium term.

Adverse effects: extrapyramidal side effects: reported by the number participants by medium term.

Quality of life: improvement as defined by each of the study by medium term.

Participants leaving the study early by medium term.

Economic outcomes: cost effectiveness (as defined in each study) by long term.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

1. Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Trials Register up to 23 September 2013 using the phrase:

[((*chlorpromazine* AND (*amisulprid* or *aripiprazol* or *clozapin* or *olanzapin* or *quetiapin* or *risperidon* or *sertindol* or *ziprasidon* or *zotepin*or *sulpiride* or *remoxipride* or *paliperidone* or *perospirone* or asenapine or clothiapine or clotiapine or iloperidone or lurasidone or mosapramine or ((Atypical or (Second NEXT generation)) and antipsychotic*))) in title, abstract or index terms of REFERENCE or interventions of STUDY)]

The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Trials Register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, handsearches and conference proceedings (see Group Module).

The seatch strategy was changed after protocol publication and we added new search terms to the strategy. The search strategy in protocol step is in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

1. Reference searching

We inspected references of all included trials for further relevant studies published in any language.

2. Personal contact

If necessary we contacted the first author, relevant pharmaceutical companies, and drug approval agencies of trials for additional information.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (BL and SZ) independently inspected citations from the searches and identified relevant abstracts. JX independently re‐inspected a random 20% sample to ensure reliability. Where disputes arose, the full report was acquired for more detailed scrutiny. BL obtained and inspected full reports of the abstracts meeting the review criteria and JX re‐inspected a random 20% of these reports in order to ensure reliable selection. Where it was not possible to resolve disagreement by discussion, we attempted to contact the authors of the study for clarification.

Data extraction and management

1. Extraction

Two review authors (BL and SZ) extracted data from all included trials. To ensure reliability of data extraction, JX independently extracted data from a random sample of these studies, comprising 10% of the total. We discussed and documented any disagreements. Another review author (SS) helped to clarify any remaining issues and we documented these final decisions. If possible, we extracted data presented only in graphs and figures, but only included this data if two review authors independently had the same result. If necessary, we attempted to contact the trial authors through an open‐ended request in order to obtain missing information or for clarification whenever necessary.

2. Management

2.1 Forms

We extracted data onto standard, pre‐designed simple forms.

2.2 Scale‐derived data

We included continuous data from rating scales only if:

The psychometric properties of the measuring instrument had been described in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000); and

The measuring instrument had not been written or modified by one of the trialists for that particular trial.

Ideally, the measuring instrument should either be i. a self‐report or ii. completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist). We realise that this is not often reported clearly. We noted in the 'Description of studies' if this was the case or not.

2.3 Endpoint versus change data

There are advantages to both endpoint and change data. Change data can remove a component of between person variability from the analysis. However, calculation of change requires two assessments (baseline and endpoint), which can be difficult in unstable and difficult to measure conditions, such as schizophrenia. We decided to primarily use endpoint data, and only use change data if the former were unavailable. We combined endpoint and change data in the analysis as we preferred to use MD rather than standardised mean difference (SMD) values throughout (Higgins 2011).

2.4 Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data we applied the following standards to all data before inclusion:

For change data:

We entered change data, as when continuous data are presented on a scale that includes a possibility of negative values (such as change data), it is difficult to tell whether data are skewed or not. We presented and entered change data into statistical analyses.

For endpoint data:

a) When a scale started from the finite number 0, we subtracted the lowest possible value from the mean, and divided this by the SD. If this value was < 1, it strongly suggested a skew, and we excluded the study. If this ratio was higher than 1 but below 2, there was suggestion of skew. We entered the study and tested whether its inclusion or exclusion would change the results substantially. Finally, if the ratio was > 2, we included the study because skew was less likely (Altman 1996; Higgins 2011).

b) If a scale started from a positive value (such as the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), which can have values from 30 to 210) (Kay 1986), we modified the calculation described above to take into account the scale starting point. In such cases skew was present if 2 SD > (S ‐ Smin), where S is the mean score and Smin is the minimum score.

(Please note, irrespective of the above rules, we entered endpoint data from studies of at least 200 participants in the analysis because skewed data pose less of a problem in large studies).

2.5 Common measure

To facilitate comparison between trials, we intended to convert variables that can be reported in different metrics, such as days in hospital (mean days per year, per week or per month) to a common metric (e.g. mean days per month). However, we did not identify such data.

2.6 Conversion of continuous to binary

Where possible, we made efforts to convert outcome measures to dichotomous data. This can be done by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into 'clinically improved' or 'not clinically improved'. It is generally assumed that if there is a 50% reduction in a scale derived score, such as the BPRS (Overall 1962) or the PANSS (Kay 1986), this could be considered a clinically significant response (Leucht 2005a; Leucht 2005b).

2.7 Direction of graphs

Where possible, we entered data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicates a favourable outcome for chlorpromazine. Where keeping to this made it impossible to avoid outcome titles with clumsy double‐negatives (e.g. 'not un‐improved') we reported data where the left of the line indicates an unfavourable outcome. We have noted this in the relevant graphs.

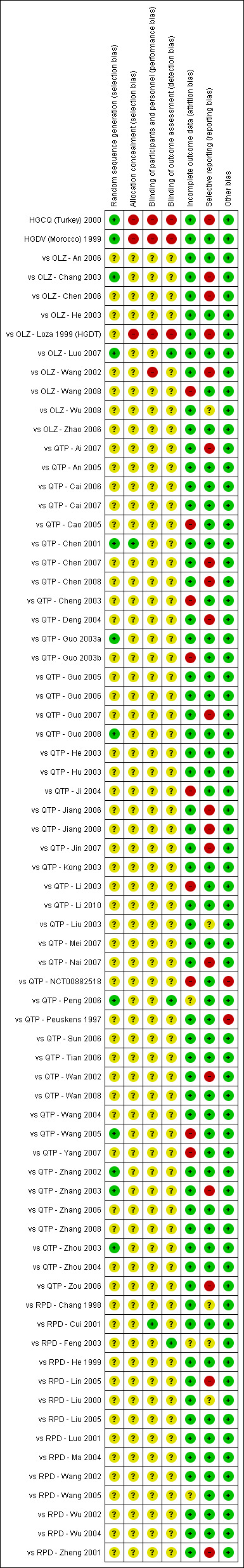

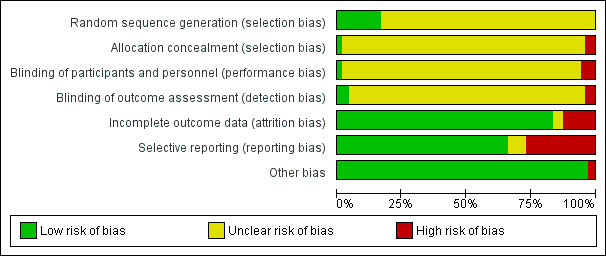

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (BL and SZ) independently assessed the risk of bias of included trials by using criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). This set of criteria is based on evidence of association between overestimate of effect and high risk of bias of the article, such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting.

If the two review authors disagreed, we made the final rating by consensus, with the involvement of another review author from the team. Where inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials were provided, we contacted trial authors for further information. We reported non‐concurrence in quality assessment, but if disputes arose as to which category a trial was to be allocated, again, we resolved this by discussion.

We described the results of the 'Risk of bias' assessments in both the review text and in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Binary data−

For binary outcomes we calculated a standard estimation of the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). It has been shown that RR is more intuitive (Boissel 1999) than odds ratios (ORs) and that ORs tend to be interpreted as RRs by clinicians (Deeks 2000). The number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB)/number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) statistic with its CIs is intuitively attractive to clinicians but is problematic both in its accurate calculation in meta analyses and interpretation (Hutton 2009). For binary data presented in the 'Summary of findings' table(s), where possible, we calculated illustrative comparative risks.

2. Continuous data

For continuous outcomes, we estimated the MD between groups. We preferred not to calculate effect size measures (SMD). However, if scales of considerable similarity were used, we assumed there was a small difference in measurement, calculated effect size and transformed the effect back to the units of one or more of the specific instruments.

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Firstly, study authors often fail to account for intra‐class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992) whereby P values are spuriously low, CIs unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999).

We did not identify any cluster‐randomised studies. However, if we identify such studies in future updates of this Cochrane review where clustering is not accounted for in primary studies, we will present data in a table, with an asterisk (*) to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. In updates of this review we will try to contact first authors of such studies to obtain intra‐class correlation coefficients (ICCs) for their clustered data and to adjust for this by using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999).

Where clustering was incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we presented these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

We received statistical advice that binary data presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the ICC [Design effect = 1 + (m − 1)*ICC] (Donner 2002). If the ICC was not reported, we assumed it was 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

Where cluster studies had been appropriately analysed taking into account ICCs and relevant data documented in the report, synthesis with other studies was possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence on entry to the second phase, the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. For the same reason cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects are very likely in severe mental illness, we planned to only use data from the first phase of cross‐over studies. However, we did not identify any cross‐over trials for inclusion in this review.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involves more than two treatment arms, if relevant, we presented the additional treatment arms in comparisons. If data were binary, we simply added these and combined within the two‐by‐two table. If data were continuous, we had planned to combine data following the formula in Section 7.7.3.8 (Combining groups) of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). Where the additional treatment arms were irrelevant, we did not reproduce these data.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility

At some degree of loss of follow‐up, data must lose credibility (Xia 2009). We chose that, for any particular outcome, should more than 50% of data be unaccounted for, we would not reproduce these data or use them within analyses. If more than 50% of those in one arm of a study were lost but the total loss was less than 50%, we addressed this within the 'Summary of findings' table(s) by downgrading the quality of the evidence. We also downgraded the quality of the evidence within the 'Summary of findings' table(s) where loss was 25% to 50% in total.

2. Binary

In the case where attrition for a binary outcome was between 0% and 50% and where these data were not clearly described, we presented these data on a 'once‐randomised‐always‐analyse' basis (an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis). We assumed all those leaving the study early to have the same rates of negative outcome as those who completed, with the exception of the outcome of death and adverse effects. For these outcomes, we used the rate of those who stayed in the study in that particular arm of the trial for those who did not. We undertook a sensitivity analysis to test how prone the primary outcomes were to change when 'completer' data only were compared to the ITT analysis using the above assumptions.

3. Continuous

3.1 Attrition

In cases where attrition for a continuous outcome was between 0% and 50% and completer‐only data was reported, we reproduced these.

3.2 Standard deviations

If SD values were not reported, we first tried to obtain the missing values from the trial authors. If unavailable, where there were missing measures of variance for continuous data, but an exact standard error (SE) and CIs available for group means, and either 'P' value or 't' value available for differences in mean, we calculated them according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011): when only the standard error (SE) is reported, SDs are calculated by the formula SD = SE * square root (n). Chapters 7.7.3 and 16.1.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a; Higgins 2011b) present detailed formulae for estimating SDs from P values, t or F values, CIs, ranges or other statistics. If these formula did not apply, we calculated the SDs according to a validated imputation method, which is based on the SDs of the other included studies (Furukawa 2006). Although some of these imputation strategies can introduce error, the alternative would be to exclude a given study's outcome and thus to lose information. We did not impute any continuous data in this review.

3.3 Last observation carried forward

We anticipated that in some studies would employ the method of last observation carried forward (LOCF) within the study report. As with all methods of imputation to deal with missing data, LOCF introduces uncertainty about the reliability of the results (Leucht 2007). Therefore, where LOCF data were used in the trial, if less than 50% of the data had been assumed, we reproduced these data and indicated that they were the product of LOCF assumptions.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge clinical heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying people or situations which we had not predicted would arise and discussed these.

2. Methodological heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge methodological heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying methods which we had not predicted would arise, and discussed.

3. Statistical heterogeneity

3.1 Visual inspection

We visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

3.2 Employing the I² statistic

We investigated heterogeneity between studies by considering the I² statistic alongside the Chi² test P value. The I² statistic provides an estimate of the percentage of inconsistency thought to be due to chance (Higgins 2003). The importance of the observed I² statistic value depends on: i. magnitude and direction of effects; and ii. strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P value from the Chi² test, or a CI for I² statistic). We interpreted an I² statistic estimate ≥ around 50% accompanied by a statistically significant Chi² test as evidence of substantial levels of heterogeneity (Section 9.5.2 ‐ Deeks 2011). When we found substantial levels of heterogeneity in the primary outcome, we explored reasons for heterogeneity (Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

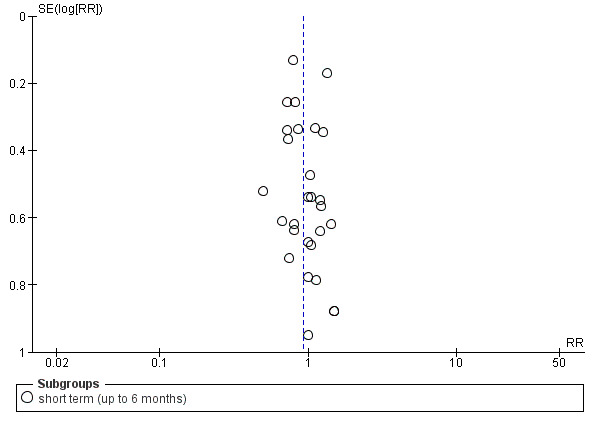

Assessment of reporting biases

1. Protocol versus full study

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results. These are described in Section 10.1 (Sterne 2011). We tried to locate protocols of included RCTs. If the protocol was available, we compared outcomes in the protocol and in the published report. If the protocol was unavailable, we compared outcomes listed in the methods section of the trial report with actually reported results.

2. Funnel plot

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1997). These are again described in Section 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. We did not use funnel plots for outcomes where there were 10 or fewer studies, or where all studies were of similar sizes. In other cases, where funnel plots are possible, we sought statistical advice in their interpretation.

Data synthesis

We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed‐effect or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This often seems to be true to us and the random‐effects model takes into account differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. However, there is a disadvantage to the random‐effects model. It puts added weight onto small studies which often are the most biased ones. Depending on the direction of effect, these studies can either inflate or deflate the effect size. We used the random‐effects model for all analyses.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

1. Subgroup analyses

1.1 Primary outcomes

We did not anticipate any subgroup analyses.

1.2 Clinical state, stage or problem

We proposed to provide an overview of the effects of chlorpromazine versus atypical antipsychotic drugs for people with schizophrenia in general in this Cochrane review. In addition, we tried to report data on subgroups of people in the same clinical state, stage and with similar problems.

2. Investigation of heterogeneity

We reported if inconsistency in trial results was high. First, we investigated whether data had been entered correctly. Second, if data were correct, we visually inspected the graph and successively removed outlying studies to see if homogeneity was restored. For this Cochrane review, we decided that should this occur with data contributing to the summary finding of no more than around 10% of the total weighting, we presented these data. If not, we did not pool these data and discussed any issues. We know of no supporting research for this 10% cut‐off but are investigating use of prediction intervals as an alternative to this unsatisfactory state.

If we observed obvious unanticipated clinical or methodological heterogeneity, we simply stated hypotheses regarding these for future reviews or versions of this Cochrane review. We did not anticipate undertaking analyses relating to these.

Sensitivity analysis

1. Implication of randomisation

We aimed to include trials in a sensitivity analysis if they were described in some way as to imply randomisation. For the primary outcomes, we included these studies. If there was no substantive difference when we added the implied randomised studies to those with better description of randomisation, then we used relevant data from these studies.

2. Assumptions for lost binary data

Where assumptions have to be made regarding people lost to follow‐up (see Dealing with missing data), we compared the findings of the primary outcomes when we used our assumption compared with completer data only. If there was a substantial difference, we reported results and discussed them but continued to employ our assumption.

Where assumptions had to be made regarding missing SDs data (see Dealing with missing data), we compared the findings on primary outcomes when we used our assumption compared with completer data only. We performed a sensitivity analysis testing how prone results were to change when 'completer' data only were compared to the imputed data using the above assumption. If there was a substantial difference, we reported results and discussed them but continued to employ our assumption.

3. Risk of bias

We analysed the effects of excluding trials that we judged to be at 'high' risk of bias across one or more of the domains of randomisation (implied as randomised with no further detail available), allocation concealment, blinding and outcome reporting for the meta‐analysis of the primary outcome. If the exclusion of trials at 'high' risk of bias did not substantially alter the direction of effect or the precision of the effect estimates, then we included data from these trials in the analysis.

4. Imputed values

We had also planned to undertake a sensitivity analysis to assess the effects of including data from trials where we used imputed values for ICC in calculating the design effect in cluster‐RCTs. However, we did not impute any values in this Cochrane review.

5. Fixed‐effect and random‐effects

We synthesised all data using a random‐effects model. However, we also synthesised data for the primary outcome using a fixed‐effect model to evaluate whether this altered the significance of the results.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

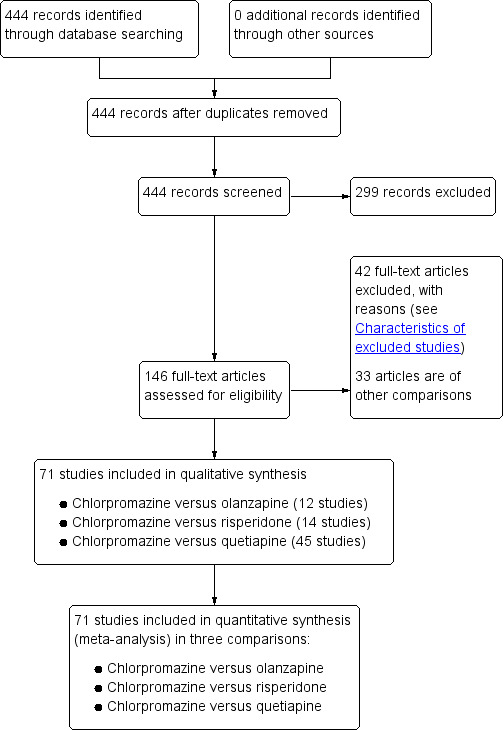

We identified 444 references following our literature search, of which we excluded 298 after screening by title/abstract. For this Cochrane review with the three comparisons of olanzapine, risperidone and quetiapine, we obtained and scrutinised 146 full‐text articles. Of these, 42 articles did not meet the inclusion criteria (see Characteristics of excluded studies) and were excluded. We included 71 trials (Figure 1). In the same literature search, we identified 33 more studies comparing chlorpromazine to atypical antipsychotics, including aripiprazole, clotiapine, clozapine, iloperidone, remoxipride, sulpiride, ziprasidone and zotepine. We will include all of these comparisons in a future update of this Cochrane review.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

1. Chlorpromazine versus olanzapine

For this comparison, we included 12 studies (total N = 919; chlorpromazine N = 432 and olanzapine N = 487).

1. Trial length

Most included studies were eight weeks in duration (vs OLZ ‐ Chang 2003; vs OLZ ‐ Chen 2006; vs OLZ ‐ He 2003; vs OLZ ‐ Luo 2007; vs OLZ ‐ Wang 2002; vs OLZ ‐ Wang 2008; vs OLZ ‐ Zhao 2006), with three studies at six weeks in duration (HGCQ (Turkey) 2000; HGDV (Morocco) 1999; vs OLZ ‐ Loza 1999 (HGDT)). The final two studies were 12 weeks (vs OLZ ‐ Wu 2008) and two years (vs OLZ ‐ An 2006) in duration. Therefore most included studies provided data for our short term outcome, with only one study providing any data for the long term.

2. Design

All included studies were parallel arm RCTs. Four out of the 12 studies provided information as to randomisation methods, which included methods such as computer‐generated randomisation and random number tables (HGCQ (Turkey) 2000; HGDV (Morocco) 1999; vs OLZ ‐ Chang 2003; vs OLZ ‐ Luo 2007).

3. Participants

All included participants had a diagnosis of schizophrenia; diagnostic criteria used included DSM‐IV (HGCQ (Turkey) 2000; HGDV (Morocco) 1999; vs OLZ ‐ Loza 1999 (HGDT)) and CCMD (vs OLZ ‐ An 2006; vs OLZ ‐ Wang 2008; vs OLZ ‐ Wu 2008; vs OLZ ‐ Zhao 2006). Diagnostic criteria were unclear in the remaining studies, with participants described either as having 'schizophrenia' (vs OLZ ‐ Chang 2003; vs OLZ ‐ Chen 2006; vs OLZ ‐ He 2003) or 'first‐episode schizophrenia (vs OLZ ‐ Luo 2007; vs OLZ ‐ Wang 2002).

4. Setting

Nine of the included studies were undertaken in China, and included both inpatient and outpatient settings. Other studies were completed in Turkey (HGCQ (Turkey) 2000), Morocco (HGDV (Morocco) 1999) and Egypt (vs OLZ ‐ Loza 1999 (HGDT)).

5. Study size

Study sizes ranged from 30 (HGCQ (Turkey) 2000) to 100 participants (vs OLZ ‐ Wu 2008); and the mean sample size was 77 participants.

6. Interventions

6.1 Chlorpromazine

Chlorpromazine doses ranged from 25 to 600 mg/day (vs OLZ ‐ Wang 2002) to 200 to 800 mg/day (HGCQ (Turkey) 2000; HGDV (Morocco) 1999; vs OLZ ‐ Chen 2006; vs OLZ ‐ Loza 1999 (HGDT)). Doses tended to be fairy consistent between studies.

6.2 Olanzapine

Olanzapine doses between studies were largely uniform, with a range in 10 of the included studies of 5 mg/day to 20 mg/day, and in vs OLZ ‐ Luo 2007 the range was 5 mg/day to 25 mg/day, with vs OLZ ‐ Wang 2008 using a range of 5 mg/day to 15 mg/day.

7. Outcomes

7.1 General remarks

The included studies for this comparison provided generally well‐reported outcomes, including clinical response, global state outcomes, relapse rates and adverse events. Death was not reported in any of the included studies for any reason.

7.2 Acceptability and efficacy

Each included study provided data regarding mental and global state outcomes (widely accepted rating scales, including the BPRS, PANSS and CGI). However, some of these data were skewed and were presented in an additional table.

7.3 Adverse events

Adverse events, including extrapyramidal averse effects, anticholinergic effect, cardiovascular effects, gastrointestinal effects and 'others' were generally well‐reported in the included studies.

7.4 Outcome scales

7.4.1 Global state

i) Clinical Global Impression (CGI)

This is a rating instrument that enables clinicians to quantify severity of illness and overall clinical improvement during therapy (Guy 1976). A 7‐point scoring system is usually used, with low scores indicating decreased severity or greater recovery, or both.

7.4.2 Mental state

i) Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)

This scale is used to assess the severity of abnormal mental states (Overall 1962). The original scale has 16 items, but a revised 18‐item scale is commonly used. Each item is defined on a seven‐point scale varying from 'not present' to 'extremely severe', scoring from zero to six or one to seven. Scores can range from 0 to 108 or 18 to 126, respectively. High scores indicate more severe symptoms. The BPRS‐positive cluster comprises four items, which are conceptual disorganisation, suspiciousness, hallucinatory behaviour and unusual thought content. The BPRS‐negative cluster comprises only three items, which are emotional withdrawal, motor retardation and blunted affect.

ii) Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA)

HAMA is a rating scale developed to quantify the severity of anxiety symptomatology and consists of 14 items, each defined by a series of symptoms (Maier 1988). Each item is rated on a 5‐point scale, ranging from zero (not present) to four (severe).

iii) Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)

The MADRS is a 10‐ item clinician‐administered diagnostic questionnaire used to measure the severity of depressive episodes (Montgomery 1979). There are 10 items (including apparent sadness, reported sadness, inner tension, reduced sleep, reduced appetite, concentration difficulties, lassitude, inability to feel, pessimistic thoughts and suicidal thoughts), each rated zero (absent) to six (severe). Overall scores range from zero to 60.

iv) Nurses' Observation Scale for Inpatient Evaluation (NOSIE)

This scale assesses the behaviour of patients on an inpatient unit (Honigfeld 1965). The scale has 30 items, each rated from zero (not present) to four (markedly present), and includes such behaviours as 'gets angry or annoyed easily', 'cries' or 'is impatient'.

iv) Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)

The PANSS was originated as a method for evaluating positive, negative and other symptom dimensions in schizophrenia (Kay 1987). The scale has 30 items, and each item can be rated on a 7‐point scoring system varying from one (absent) to seven (extreme). This scale can be divided into three subscales for measuring the severity of general psychopathology, positive symptoms (PANSS‐P) and negative symptoms (PANSS‐N). A low score indicates low levels of symptoms.

v) Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS)

This scale measures the positive symptoms of schizophrenia and is split into four items including hallucinations, delusions, bizarre behaviour and positive formal thought disorder, each rated on a scale of zero (absent) to five (severe) (Andreasen 1984).

7.4.3 Functioning

i) Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST‐IQ/MQ)

The WCST is a neuropsychological test in which participants are expected to organise a set of specifically‐designed cards, without instruction (Monchi 2001). The test is a measure of executive functioning, assessing primarily strategic planning, organized searching, utilizing environmental feedback to shift cognitive sets, directing behavior toward achieving a goal, and modulating impulsive responding.

7.4.4 Adverse events

i) Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (ESRS)

The ESRS is a physical examination with 12 items that include both subjective and objective assessments (Chouinard 1980).

iii) Leeds Sleep Evaluation Questionnaire (LSEQ)

The LSEQ is a 10‐item, self‐rating measurement designed to assess changes in sleep quality over the course of psychopharmacological treatment (Parrott 1980). Four domains are rated, including 'ease of initiating sleep', 'quality of sleep', 'ease of waking' and 'behaviour following wakefulness'.

7.4.5 Quality of life

i) Gothenburg Quality of Life Instrument (GQOLI/ GQOL1 ‐ 74)

This scale assesses overall sleep quality; participants respond on a 7‐point Linkert‐type scale with one (excellent) and seven (very poor) (Sullivan 1993). Participants also rate other aspects of quality of life, including a self‐evaluation of their economic situation, social and friendship situation and home/family situation.

ii) Quality of life scale (QoL)

The QoL scale is a 16‐item instrument that measures six conceptual domains of quality of life: material and physical well‐being, relationships with other people, social, community and civic activities, personal development and fulfilment, recreation and independence (Flanagan 1982). Scores range from 16 to 112, with a higher score indicating a better outcome.

7.5 Missing outcomes

Studies did not provide vast amounts of data, nor even measured in many instances, outcomes including service involvement, functioning, behaviour, satisfaction with treatment, or economic outcomes.

2. Chlorpromazine versus risperidone

For this comparison, we included 14 studies, with a total of 991 participants (chlorpromazine N = 474; risperidone N = 517).

1. Trial length

Duration of included studies ranged from three weeks (vs RPD ‐ Liu 2005) to five months (vs RPD ‐ Chang 1998). The average length of studies was around eight weeks, therefore all included studies provided only short term data.

2. Design

All included studies were parallel‐arm RCTs. No included study adequately described randomisation methods.

3. Participants

All participants were diagnosed with schizophrenia according to Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders (CCMD) criteria (Chen 2002).

4. Setting

All included studies were undertaken in China with inpatient and outpatient settings both represented.

5. Study size

Sample sizes between studies ranged from 32 (vs RPD ‐ Liu 2000) to 107 participants (vs RPD ‐ Luo 2001), with a mean sample size of 70 participants.

6. Interventions

6.1 Chlorpromazine

All studies used different dosage ranges, and included 25 to 450 mg/day (vs RPD ‐ Wang 2005); 100 to 450 mg/day (vs RPD ‐ Lin 2005); 300/400 to 600 mg/day (vs RPD ‐ Wu 2002; vs RPD ‐ Wu 2004); and 100 to 700 mg/day (vs RPD ‐ Luo 2001). Not all studies reported mean doses, with only vs RPD ‐ Cui 2001 and vs RPD ‐ Feng 2003 using a mean dose of 426 mg/day and 355 mg/day respectively.

6.2 Risperidone

Risperidone doses also varied between studies, with the highest range of 1 mg/day to 9 mg/day used in vs RPD ‐ Ma 2004; most included studies used a range of risperidone up to 6 mg/day (vs RPD ‐ Chang 1998; vs RPD ‐ He 1999; vs RPD ‐ Wang 2005; vs RPD ‐ Wu 2002; vs RPD ‐ Wu 2004; vs RPD ‐ Zheng 2001). Again, only two studies described the mean doses used in the studies (vs RPD ‐ Cui 2001; vs RPD ‐ Feng 2003) of 4.19 mg/day and 3.62 mg/day respectively.

7. Outcomes

7.1 General remarks

The included studies for this comparison provided generally well‐reported outcomes, including clinical response, global state outcomes and adverse events. Death was not reported in any of the included studies for any reason.

7.2 Acceptability and efficacy

Data regarding mental and global state outcomes were measured using widely accepted rating scales, including the BPRS, PANSS and CGI. However some of these data were skewed and were presented in an additional table.

7.3 Adverse events

Adverse events, including extrapyramidal averse effects, anticholinergic effect, cardiovascular effects, gastrointestinal effects and 'others' were generally well reported in the included studies.

7.4 Outcome scales presenting useable data

7.4.1 Global state

i) Clinical Global Impression (CGI)

This is a rating instrument that enables clinicians to quantify severity of illness and overall clinical improvement during therapy (Guy 1976). A 7‐point scoring system is usually used with low scores indicating decreased severity or greater recovery, or both.

7.4.2 Mental state

i) Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)

This scale is used to assess the severity of abnormal mental states (Overall 1962). The original scale has 16 items, but a revised 18‐item scale is commonly used. Each item is defined on a 7‐point scale varying from 'not present' to 'extremely severe', scoring from zero to six or one to seven. Scores can range from zero to 108 or 18 to 126, respectively. High scores indicate more severe symptoms. The BPRS‐positive cluster comprises four items, which are conceptual disorganisation, suspiciousness, hallucinatory behaviour and unusual thought content. The BPRS‐negative cluster comprises only three items, which are emotional withdrawal, motor retardation and blunted affect.

ii) Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)

The PANSS was originated as a method for evaluating positive, negative and other symptom dimensions in schizophrenia (Kay 1987). The scale has 30 items, and each item can be rated on a 7‐point scoring system varying from one (absent) to seven (extreme). This scale can be divided into three subscales for measuring the severity of general psychopathology, positive symptoms (PANSS‐P) and negative symptoms (PANSS‐N). A low score indicates low levels of symptoms.

iii) Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS)

The SANS measures the incidence and severity of negative symptoms using a 25‐item scale, using a six‐point scoring system, of zero ( = better) to five ( = worse), where a higher score equals a more severe experience of negative symptoms (Andreasen 1982).

iv) Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS)

This scale measures the positive symptoms of schizophrenia and is split into four items including hallucinations, delusions, bizarre behaviour and positive formal thought disorder, each rated on a scale of zero (absent) to five (severe) (Andreasen 1984).

7.4.3 Functioning

i) Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST‐IQ/MQ)

The WCST is a neuropsychological test in which participants are expected to organise a set of specifically‐designed cards, without instruction (Monchi 2001). The test is a measure of executive functioning, assessing primarily strategic planning, organized searching, utilizing environmental feedback to shift cognitive sets, directing behavior toward achieving a goal, and modulating impulsive responding.

7.4.4 Adverse events

i) Treatment‐Emergent Signs and Symptoms (TESS)

The ICH E3 1995 guideline has stated that 'treatment‐emergent signs and symptoms' (TESS) are to be defined as "events not seen at baseline and events that worsened even if present at baseline". It can be difficult to document this accurately taking into account variables in time, dosage, adverse events and severity. Generally, TESS scores for particular adverse events are categorised as 'mild', 'moderate' or 'severe', with an appropriate action taken (e.g. none, discontinued, dose changed', hospitalisation and additional medication given). It is not often that studies publish continuous data from these measurements, with the more common presentation of dichotomised TESS ratings.

7.4.5 Quality of life

i) Quality of life scale (QoL)

The QoL scale is a 16‐item instrument that measures six conceptual domains of quality of life: material and physical well‐being; relationships with other people; social, community and civic activities; personal development and fulfilment; recreation and independence (Flanagan 1982). Scores range from 16 to 112, with a higher score indicating a better outcome.

7.5 Missing outcomes

Studies did not report any data for relapse rates, service use, behaviour, satisfaction with care or treatment, or economic outcomes.

3. Chlorpromazine versus quetiapine

For this comparison, we included 45 studies with a total of 4388 participants (chlorpromazine N = 2183; quetiapine N = 2205).

1. Trial length

Thirty‐seven of the 45 studies were under eight weeks in length. The shortest study was 42 days in length (vs QTP ‐ Peng 2006). The longest study was six months long (vs QTP ‐ Li 2003) and was the only study to provide data at the medium term. All other outcomes were reported at short term (< six months).

2. Design

All included studies were parallel‐arm RCTs. No included study adequately described randomisation methods.

3. Participants

All participants had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, with diagnosis using the Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders (CCMD) employed in 42 included studies. Two studies used DSM criteria to diagnose schizophrenia (vs QTP ‐ Hu 2003; vs QTP ‐ Peuskens 1997), and one study used a combination of CCMD and ICD‐10 criteria (vs QTP ‐ Zhou 2004).

4. Setting

All included studies were undertaken in China with both inpatient and outpatient settings represented.

5. Study size

Sample sizes between studies ranged from 30 (vs QTP ‐ Kong 2003) to 237 participants (vs QTP ‐ Zhang 2003).

6. Interventions

6.1 Chlorpromazine

The most common dose range between groups was between 300 to 600 mg/day. Only one study stated dosages used were 'less than 1000 mg/day' (vs QTP ‐ Guo 2008), with other maximum doses stated as 750 mg/day (vs QTP ‐ Peuskens 1997).

6.2 Quetiapine

Quetiapine doses were mostly between 300 and 700 mg/day. One study did not state the dosages used in either group (vs QTP ‐ Zhou 2003).

7. Outcomes

7.1 General remarks

The included studies for this comparison generally provided well‐reported outcomes, including clinical response, global state outcomes and adverse events. Death was not reported in any of the included studies for any reason. Most outcomes were reported using measurement scales, although we ensured they had been peer‐reviewed as the lack of dichotomous outcomes makes valuable interpretation of these results difficult.

7.2 Acceptability and efficacy

Data regarding mental and global state outcomes were reported using widely accepted rating scales, including the BPRS, PANSS and CGI. However some of these data were skewed and were presented in an additional table.

7.3 Adverse events

Adverse events, including extrapyramidal averse effects, anticholinergic effect, cardiovascular effects, gastrointestinal effects and 'others' were generally well reported in the included studies.

7.4 Outcome scales

7.4.1 Global state

i) Clinical Global Impression (CGI)

This is a rating instrument that enables clinicians to quantify severity of illness and overall clinical improvement during therapy (Guy 1976). A 7‐point scoring system is usually used with low scores indicating decreased severity or greater recovery, or both.

7.4.2 Mental state

i) Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)

This scale is used to assess the severity of abnormal mental states (Overall 1962). The original scale has 16 items, but a revised 18‐item scale is commonly used. Each item is defined on a 7‐point scale varying from 'not present' to 'extremely severe', scoring from zero to six or one to seven. Scores can range from zero to 108 or 18 to 126, respectively. High scores indicate more severe symptoms. The BPRS‐positive cluster comprises four items, which are conceptual disorganisation, suspiciousness, hallucinatory behaviour and unusual thought content. The BPRS‐negative cluster comprises only three items, which are emotional withdrawal, motor retardation and blunted affect.

ii) Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD)

The HAMD rates severity of depression in adults including items of mood, feelings of guilt, suicide ideation, insomnia, agitation or retardation, anxiety, weight loss and somatic symptoms (Hamilton 1960). There are 20 items rated on a Linket‐type scale, where zero equals an absence of symptoms and a higher score indicates a worse outcome.

iii) Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)

The PANSS was originated as a method for evaluating positive, negative and other symptom dimensions in schizophrenia (Kay 1987). The scale has 30 items, and each item can be rated on a 7‐point scoring system varying from one (absent) to seven (extreme). This scale can be divided into three subscales for measuring the severity of general psychopathology, positive symptoms (PANSS‐P) and negative symptoms (PANSS‐N). A low score indicates low levels of symptoms.

7.4.3 Functioning

i) Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST‐IQ/MQ)

The WCST is a neuropsychological test in which participants are expected to organise a set of specifically‐designed cards, without instruction (Monchi 2001). The test is a measure of executive functioning, assessing primarily strategic planning, organized searching, utilizing environmental feedback to shift cognitive sets, directing behaviour toward achieving a goal and modulating impulsive responding.

ii) Wechsler Memory Scale‐revised (WMS‐RC)

The WMS‐RC is a neuropsychological test that is used to measure a person's memory functions (WMS‐IV 2009). The scale consists of seven subtests: spatial addition, symbol span, design memory, general cognitive screener, logical memory, verbal paired associates and visual reproduction. A high score indicates a better outcome.

7.4.4 Adverse events

i) Treatment‐Emergent Signs and Symptoms (TESS)