Abstract

This study characterizes hepatitis C virus (HCV) testing and the HCV care cascade among 13- to 21-year-olds accessing US federally qualified health centers.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) incidence is increasing in the United States,1 with most new transmissions occurring among people younger than 30 years who inject drugs.2 Fifteen- to 24-year-olds represent an increasing proportion of reported chronic HCV infections, rising from 3.8% in 2009 to 9.1% in 2013-2016.1 Although HCV testing and linkage to care are crucial steps toward eliminating HCV, to our knowledge no studies have specifically examined HCV testing practices among youths. Current guidance recommends HCV testing for children or adults with HCV risk,3 including anyone who has injected drugs, the most frequently identified risk factor.1,2 We sought to characterize HCV testing and the HCV care cascade among 13- to 21-year-olds accessing US federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), an important health care source for underserved communities.4

Methods

This study included individuals aged 13 to 21 years at study end who had 1 or more visits to an OCHIN (previously the Oregon Community Health Information Network)–affiliated FQHC from January 2012 to September 2017. OCHIN comprises a 57-FQHC (19 states) network sharing a common electronic health record. We excluded individuals with HCV diagnosed by an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) or International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code before observed HCV testing.

We obtained characteristics, including demographics, substance use documentation by ICD-9/10 code or from the electronic health record social history section (Table), medication lists, and completed laboratory results. Documented opioid, amphetamine, or cocaine use, shown to have 80% sensitivity and 81% specificity for reported injection drug use,5 were considered a proxy for HCV risk. We characterized the HCV care cascade for all included individuals: HCV antibody testing completed (anti-HCV tested), anti-HCV positive, HCV RNA testing completed, HCV RNA detected, HCV genotype completed, and HCV treatment initiated (by medication order). The Boston Medical Center institutional review board approved this study with a waiver of informed consent given the use of deidentified, pooled data.

Table. Demographic Characteristics and Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Antibody Testing Among Youths Seen at a Participating US Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC), January 2012 to September 2017a.

| Characteristic | Total No. | HCV Antibody, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Testedb | Positivec | ||

| All | 269 124 | 6812 (2.5) | 122 (1.8) |

| Age at study end, y | |||

| 13-15 | 78 427 | 509 (0.6) | 6 (1.2) |

| 16-18 | 92 353 | 2085 (2.3) | 22 (1.1) |

| 19-21 | 98 344 | 4218 (4.3) | 94 (2.2) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 121 926 | 3175 (2.6) | 50 (1.6) |

| Female | 147 198 | 3637 (2.5) | 72 (2.0) |

| Race/ethnicityd | |||

| Non-Hispanic | |||

| White | 101 014 | 2293 (2.3) | 57 (2.5) |

| Black | 47 476 | 1743 (3.7) | 19 (1.1) |

| Hispanic | 90 203 | 2077 (2.3) | 28 (1.4) |

| Other | 30 431 | 699 (2.3) | 18 (2.6) |

| Identified substance usee | |||

| Alcohol | 1591 (0.6) | 172 (10.8) | 4 (2.3) |

| Amphetamine | 1738 (0.6) | 580 (33.4) | 34 (5.9) |

| Cannabis | 20 058 (7.5) | 1758 (8.8) | 36 (2.0) |

| Cocaine | 883 (0.3) | 330 (37.4) | 11 (3.3) |

| Opioids | 875 (0.3) | 311 (35.5) | 33 (10.6) |

| Any potentially injectable substancef | 2573 (1.0) | 761 (29.6) | 54 (7.1) |

FQHCs were located in Alaska, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Texas, Utah, Wisconsin, and Washington.

Row percentages of youths with a listed characteristic who were tested for HCV.

Conditional row percentages of HCV antibody–positive youths with a listed characteristic among those tested for HCV.

Abstracted from the electronic medical record and classified by the investigators into the listed categories to describe the diversity of the sample for consideration of generalizability of the results.

Identified substance use is not mutually exclusive.

Identified use of any of the following substances that could be injected: opioids, amphetamine, or cocaine.

Results

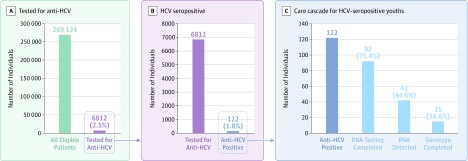

Among 269 124 youths who met inclusion criteria (54.7% female; 62.5% nonwhite; 0.3% with diagnosed opioid use), 6812 (2.5%) were anti-HCV tested; of these, 122 (1.8% of those tested) were anti-HCV positive (Table). Mean age at first anti-HCV test was 18.5 (SD, 2.2) years and at first positive anti-HCV test result was 19.1 (SD, 2.2) years. Among 2573 individuals (1.0%) with documented opioid, amphetamine, or cocaine use, 761 (29.6%) were anti-HCV tested, of whom 54 (7.1% of those tested) were anti-HCV positive (Table). Ninety-two individuals (75.4% of those anti-HCV positive) had HCV RNA testing; of those, 41 (44.6%) had detectable RNA, indicating current infection, and 15 (36.6% of those with detectable RNA) completed genotype testing (Figure). Only 1 individual had documented initiation of HCV treatment.

Figure. Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Care Cascade Among 13- to 21-Year-Olds Seen at a Participating US Federally Qualified Health Center, January 2012 to September 2017.

Outcomes along the HCV care cascade: HCV antibody testing completed (anti-HCV tested), HCV seropositive (anti-HCV positive), HCV RNA testing completed, HCV RNA detected, and HCV genotype completed. One patient with HCV treatment initiated not shown (the first direct acting antiviral therapy was not approved for 12- to 17-year-olds until April 2017). Percentages in panel C are conditional.

Discussion

In this large sample of 13- to 21-year-olds accessing a network of FQHCs, 30% with identified opioid, amphetamine, or cocaine use were tested for HCV, and only 1 had documented HCV treatment. Since not all individuals with opioid, amphetamine, or cocaine use inject drugs, ICD-9/10 codes used as a proxy for HCV infection risk might overestimate the population at risk due to injection use.5 Given underdiagnosis of substance use, however, it is likely that fewer individuals with any injectable substance use were HCV tested than the observed 30% with documented use.

In fact, most youths tested lacked documented injectable substance use or another known testing indication. Although clinicians may have HCV tested diagnostically or for other uncaptured risk, testing may also signal undocumented injection use or inappropriate testing. Improved substance use screening and documentation are critical for successful guideline-concordant HCV testing.

Other study limitations include the use of pooled data from FQHCs in 19 states, which may limit generalizability and precluded analysis by US geographical region. Also, youths accessing FQHCs may be HCV tested or treated elsewhere, but this unlikely fully mitigates the low observed screening and treatment rates.

Early identification of HCV is critical to cure current infections, prevent transmission and morbidity from disease progression, and eliminate HCV, particularly with effective treatments now approved in 12- to 17-year-olds.6 Low HCV testing and treatment rates in youths with documented opioid, amphetamine, or cocaine use in this study suggest that program design and policy improvements are needed.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Surveillance for viral hepatitis—United States, 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2016surveillance/commentary.htm. Published April 17, 2018. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- 2.Zibbell JE, Iqbal K, Patel RC, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Increases in hepatitis C virus infection related to injection drug use among persons aged ≤30 years—Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia, 2006-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(17):453-458. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945-1965. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61(RR-4):1-32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xue Y, Greener E, Kannan V, Smith JA, Brewer C, Spetz J. Federally qualified health centers reduce the primary care provider gap in health professional shortage counties. Nurs Outlook. 2018;66(3):263-272. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2018.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janjua NZ, Islam N, Kuo M, et al. ; BC Hepatitis Testers Cohort Team . Identifying injection drug use and estimating population size of people who inject drugs using healthcare administrative datasets. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;55:31-39. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Indolfi G, Easterbrook P, Dusheiko G, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection in children and adolescents. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4(6):477-487. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30046-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]